Submitted:

08 June 2023

Posted:

13 June 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Summary

| Level | Processes relevant to AD pathobiology |

| Molecular | Beta-amyloid is the neurotoxin that causes neurodegeneration in AD. Primary molecular interaction underlying beta-amyloid cytotoxicity is the formation of non-selective giant membrane channels. Amyloid membrane channels are formed by amyloid fragments with a positive charge in membranes carrying negative surface charge. Spontaneous aggregation of beta-amyloid cannot be initiated in the intercellular space because of extremely low concentration, but existing amyloid aggregates grow extracellularly by absorbing soluble beta-amyloid. |

| Organelle | Lysosomes are the primary target in cytotoxic action of beta-amyloid. Intralysosomal digestion of beta-amyloid produces channel-forming amyloid fragments. Lysosomal membrane carries significant negative surface charge required for the formation of membrane amyloid channels. |

| Cellular | Endocytosis of beta-amyloid is the first step required for cytotoxicity. Membrane channels of any size cause lysosomal disfunction, while extremely large channels allow for the leakage of lysosomal proteins to the cytoplasm. Leaked cathepsins induce either necrosis or apoptosis. Lysosomal permeabilization and lysosomal failure is the origin of other cellular hallmarks of AD – mitochondrial insufficiency, increased production of reactive oxygen species, appearance of dysfunctional lysosomes, tau-protein accumulation, intracellular ion disturbances etc. Beta-amyloid, which is stored intralysosomally, is the origin of aggregation seeds. Seeds of aggregated beta-amyloid are exocytosed and then grow extracellularly. Endocytosis of beta-amyloid is required for the appearance of senile plaques. |

| Tissue/Organ | Cellular death explains gross brain pathology in AD (especially in advanced stages of the disease): parenchymal atrophy, low metabolism etc. The common origin of both aggregation and cytotoxicity – cellular uptake of beta-amyloid - explains why the presence of senile plaques is the hallmark of AD. Therefore, the density of amyloid deposits is pathophysiology-relevant but indirect biomarker of AD. |

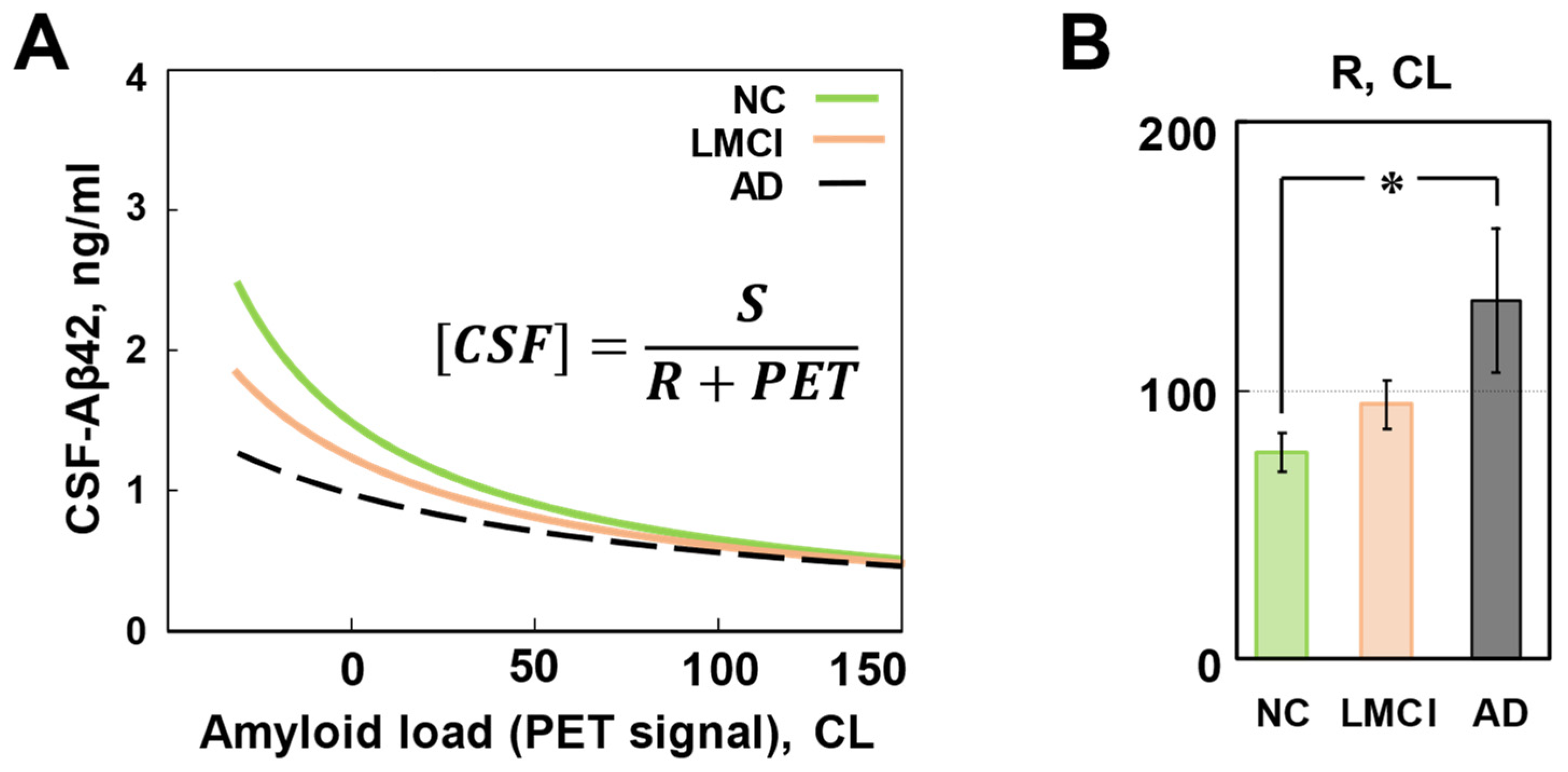

| Organism | Patients with late-onset AD have higher cellular uptake of Aβ42 compared with subjects with normal cognition. As both neurodegeneration and beta-amyloid aggregation are initiated by the same process - cellular amyloid uptake - higher amyloid uptake is the reason for faster neurodegeneration and higher density of amyloid deposits in patients with AD. The concentration of Aβ42 in the CSF is predominantly defined by the aggregation of toxic soluble peptide on existing amyloid deposits, while the density of deposits correlates with neurodegeneration. For that reason, CSF-Aβ42 can serve as a standalone AD biomarker which is similar in value to the density of amyloid deposits. Therefore, CSF-Aβ42 is also pathophysiology-relevant but indirect biomarker of AD. However, in patients with the same density of beta-amyloid deposits, higher cellular uptake rate results in lower CSF-Aβ42. At predefined density of deposits, lower CSF-Aβ42 indicates higher cellular amyloid uptake and faster neurodegeneration. Therefore, CSF-Aβ42 has diagnostic value, which is independent of the diagnostic value of the density of amyloid deposits. It is advantageous to use two major amyloid biomarkers together if possible until direct pathophysiology-relevant biomarkers are developed. |

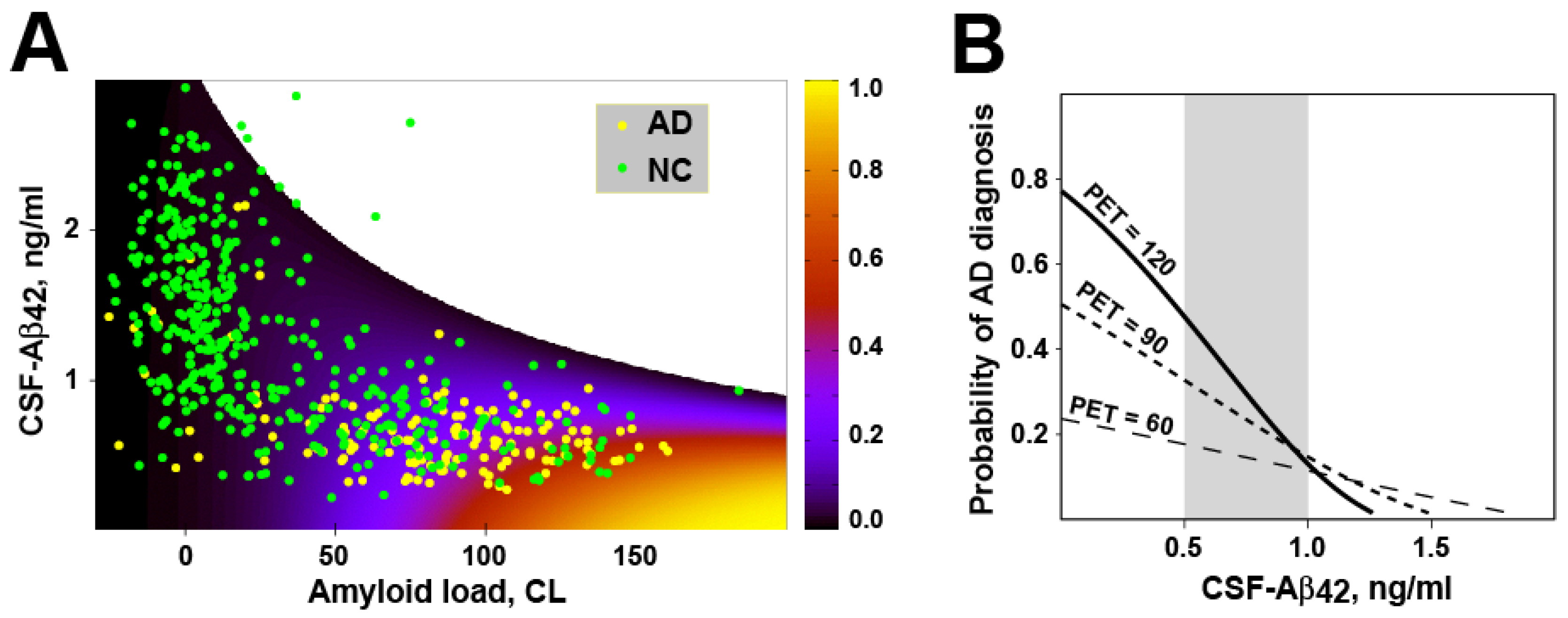

| Population | The probability of AD diagnosis in a particular patient depends on the accumulated neurotoxicity of Aβ42, which in turn depends on the accumulated amount of endocytosed Aβ42. However, the neurotoxicity of endocytosed Aβ42 also depends on the relative toxicity of this peptide. Relative toxicity can be different between patients. The mathematical model which considers all these conditions accurately reproduces clinical data on the distribution of biomarkers and probability of AD in the population. Currently used biomarkers (the density of amyloid deposits and the concentration of Aβ42 in the CSF) are related to AD pathobiology and have good correlation with the disease. However, the ability to diagnose and, more importantly, predict the development of the disease, is limited by their non-direct nature. Methods that allow for the estimation of cellular amyloid uptake (such as the stable isotope labelling kinetics technique, SILK) would be more optimal for developing biomarkers and predictors of AD. Methods to estimate and modulate the relative neurotoxicity of beta-amyloid in patients are also the way to address the unmet need in the treatment of Alzheimer disease. |

- The description of the amyloid degradation toxicity hypothesis

| Molecular level |

| Beta-amyloid is cleaved from a long precursor molecule (amyloid precursor peptide, APP) by proteases called secretases. |

| The predominant form is 40-amino acid-long peptide (Aβ40), however, senile plaques in the brain, which are histological hallmarks of AD, contain mostly 42-amino acid-long Aβ42. Both amyloid forms are produced by consecutive action of beta-secretase and gamma-secretase. |

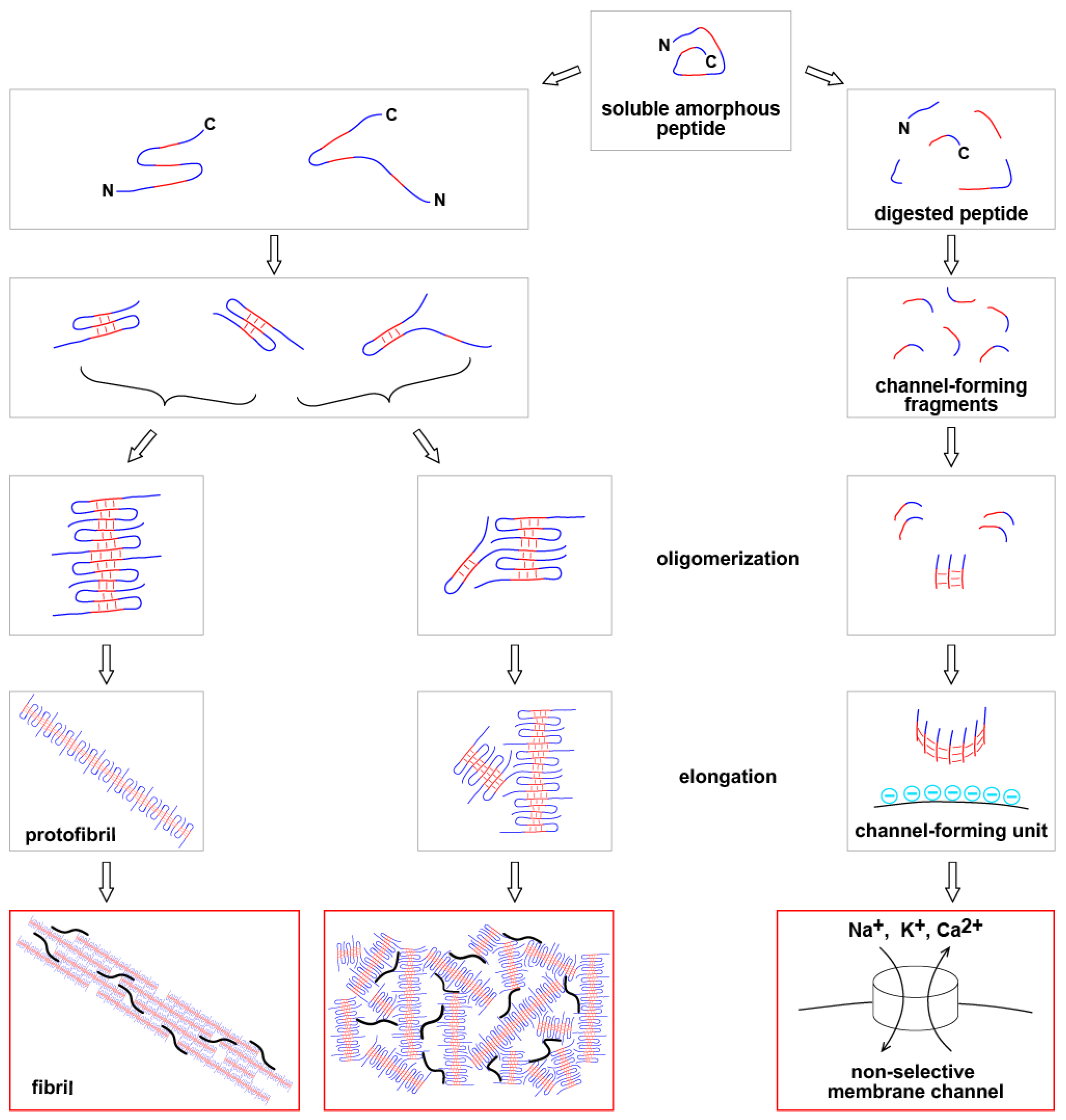

| Immediately after synthesis, beta-amyloid does not have secondary structure and is soluble. |

| With time, the peptide can form pleated beta-sheet (one of two major secondary protein structures) within the molecule. The formation of multimolecular beta-sheets produces beta-amyloid oligomers. |

| Elongation of oligomers and interaction between multiple oligomeric complexes form insoluble aggregates. Senile plaques are amyloid polymers which include other proteins. |

|

| Soluble beta-amyloid is toxic to healthy cells in vitro, while aggregated beta-amyloid is non-toxic. |

| Cytotoxicity is mediated by oligomeric form of beta-amyloid [1]. |

|

| There is no known receptor or ion channel which can be activated by beta-amyloid peptide(s) in a way that such activation would result in cell death. |

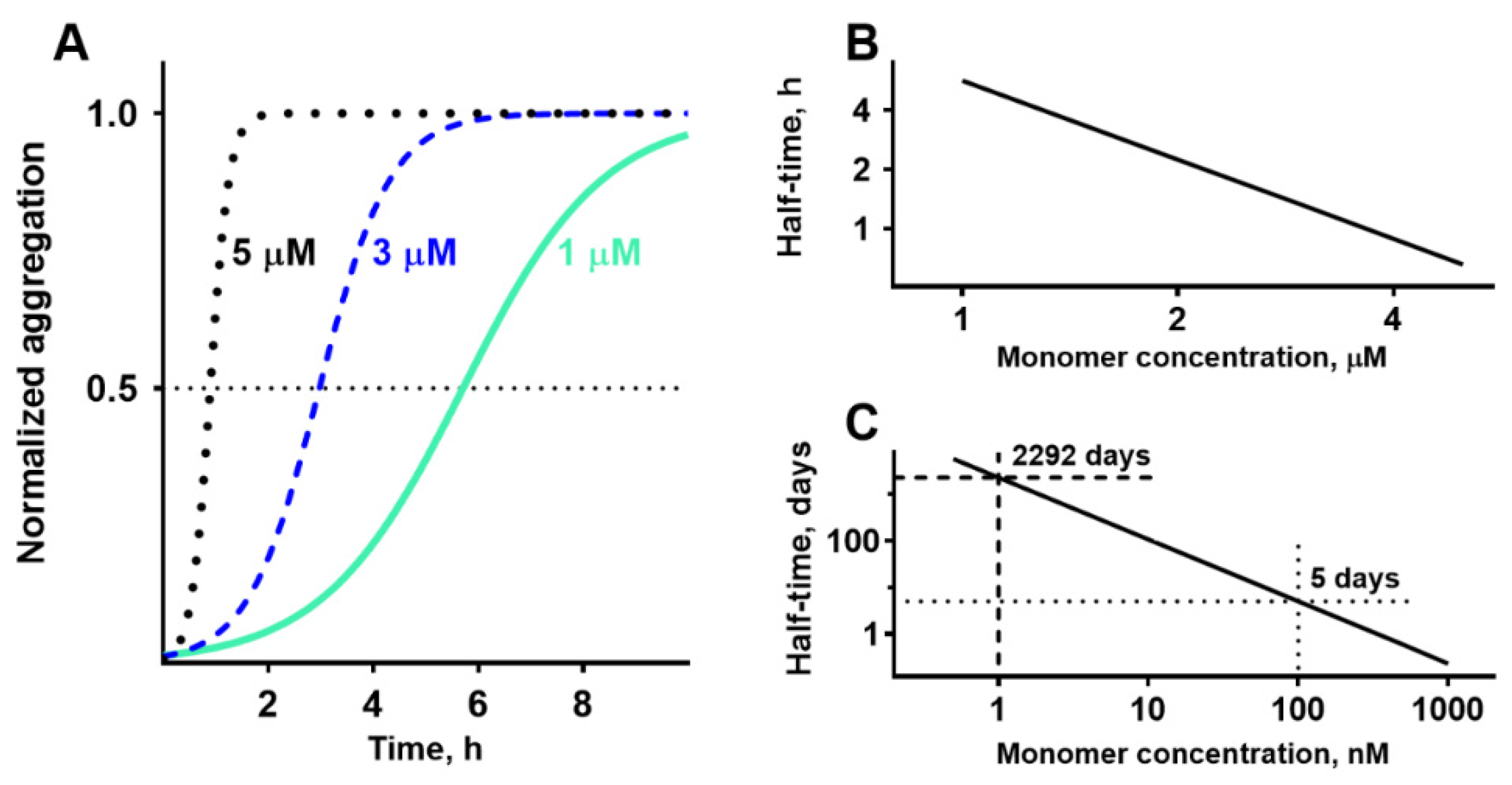

| Absorption of beta-amyloid on lipid membranes can cause membrane damage only in concentrations exceeding 1 µM [2,3], while extracellular concentrations of beta-amyloid are in the nanomolar range. |

| Beta-amyloid peptide(s) can form membrane channels [4,5,6]. |

|

| Some amyloid fragments form membrane channels much more effectively than full-length peptides [6,7,8]. |

| Not all fragments have channel-forming ability [7,8]. |

| Channels are formed in membranes carrying negative surface charge [7,9]. |

| Each channel is formed by multiple molecules of peptide (channels are oligomers) [10]. |

| Amyloid membrane channels are non-selective [4,5]. |

| Channels are giant (with conductance up to several nanosiemens) and have various sizes [4,5,6,11,12]. |

| The largest channels (conductance higher than 1 nS) can pass macromolecules [13]. |

|

| Alzheimer’s disease is developing over multiple years. |

| The conductance of a single channel is sufficient to destroy the barrier function of membrane of an organelle or whole cell [5]. |

|

| Organelle level |

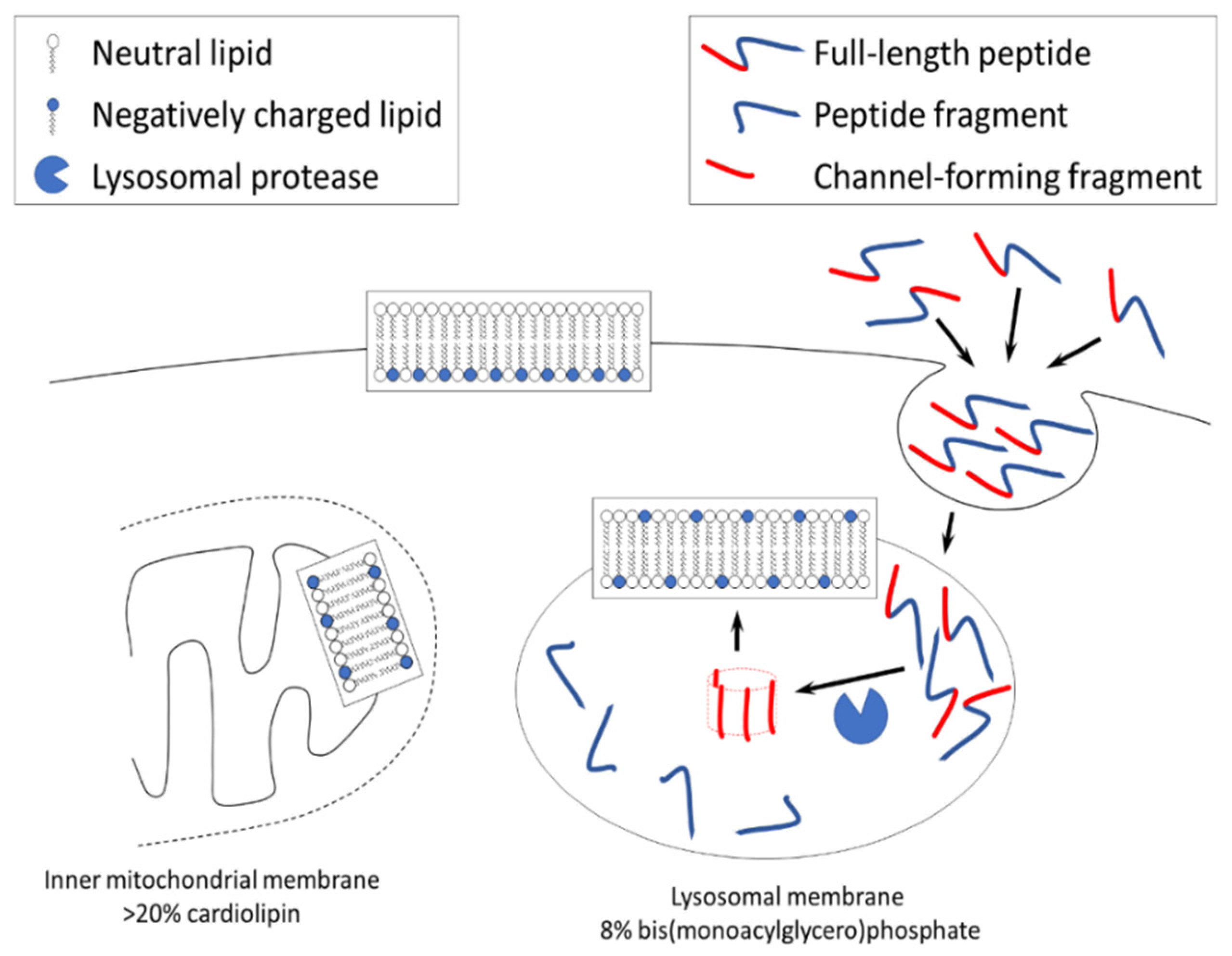

| Outer leaflet of plasma membrane of healthy cells is not negatively charged [14]. |

| There is extremely limited experimental electrophysiological data that supports the formation of giant amyloid channels in plasma membrane of cultured cells in vitro [15]. |

|

| Inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) is negatively charged but known pathways require the involvement of other organelles (such as endosomes) for the delivery of channel-forming beta-amyloid fragments to the IMM [14]. |

|

| Beta-amyloid is endocytosed by cells and is accumulated in lysosomes [16]. |

| The presence of a variety of lysosomal proteases suggests that at least some of them can generate channel-forming fragments [17]. |

| Lysosomal membranes have a strong negative surface charge [14], which is the prerequisite for the formation of membrane amyloid channel [8]. |

|

| Cellular level |

| Cells exposed to the Aβ42 demonstrate synchronous oscillations of concentrations of several intracellular ions (calcium, sodium, potassium, pH), that matches the concept of an opening of a non-selective membrane channel [18]. |

| The frequency of channel conductance oscillations that are observed electrophysiologically (millisecond range, [4,5]) does not match the time scale of oscillations in intracellular ion concentrations (seconds to minutes, [18,19]). |

| The conductance of amyloid membrane channels is very high. If a channel is formed in the plasma membrane, intracellular and extracellular ion concentrations will equilibrate fast [5]. |

| The cellular ion concentrations return to their baseline after each individual wave induced by exposure to beta-amyloid [18]. |

| The direction of ion disturbances and rapid recovery does not support the concept that channels are formed in the plasma membrane [20]. |

|

| Observed oscillations in intracellular ion concentrations (increases in calcium and potassium and decreases in pH and sodium) match the ion disturbances that could be caused by the permeabilization of lysosomes [20]. |

| The small volume of individual lysosomes allows for quick restoration of normal ion balance in the cell following the damage to a single lysosome, resulting in the observed ion disturbance as a wave. |

| The oscillations are caused by the permeabilization of multiple lysosomes [20]. |

|

| Cells exposed to the Aβ42 demonstrate the leakage of content from multiple lysosomes (but not all), without any indication of plasma membrane damage [21,22]. |

| Cells exposed to the Aβ42 demonstrate the leakage of content from lysosomes before cell death [21]. |

| In cells exposed to the beta-amyloid, lysosomes leak not only small molecules (such as Lucifer Yellow, M.W.444 [21] or ethidium bromide, M.W.394 [15]), but also larger molecules such as cathepsin D and enzymes with M.W. 150 kDa [21]. |

| The electrophysiological data suggests that the largest amyloid channels allow for the passage of macromolecules [12,13]. |

|

|

| Even a single channel is enough to equilibrate ion concentrations inside entire organelle with the cytoplasm. |

| Amyloid membrane channel, regardless of its size, is permeable to protons and can cause lysosomal content to become non-acidic. |

| Neutralization of lysosomal content inactivates acidic proteases, prevents normal digestion of lysosomal cargo, and results in lysosomal failure. |

| Improper cellular recycling due to lysosomal failure prevents the removal of damaged lysosomes. |

|

| The largest amyloid channels (with a conductance of several nS), though rare, are capable of transporting macromolecules that are equal to or larger in size than lysosomal cathepsins [13]. |

| The lysosomal cathepsins released into the cytoplasm can induce either necrosis or activate caspases, leading to apoptosis. In both cases, cell death occurs. |

|

| After the exposure to beta-amyloid, the pathway leading to cell death is a multistep process that includes endocytosis, intralysosomal proteolysis, and the leakage of cathepsins into the cytoplasm. |

| The formation of giant amyloid channel is a rare event. Only a small percentage of amyloid channels can kill the cell. |

| It could require long exposure to beta-amyloid to produce sufficient number of cytotoxic channels in a significant proportion of cells. |

|

| The formation of small channels is a more frequent event, but it does not directly lead to cell death. |

| Cells with lysosomes carrying small amyloid channels survive but would have dysfunctional lysosomes present. |

| After the exposure to beta-amyloid, the cell death is primarily mediated by the formation of extremely large (giant) channels. |

|

| The symptoms of AD depend on the number and functional status of remaining neurons. |

| Neurons which are damaged by the formation of small amyloid channels can recover. |

| The recovery requires the prevention of formation of new channels. |

|

| The progression of AD depends on the rate of neuronal death. |

|

|

| Tissue/Organ level |

| Neurons are responsible for 70–80% of total brain energy consumption [23,24]. |

|

| Lysosomal failure leads to improper recycling of various cell organelles. |

| Mitochondria are the most sensitive to improper recycling due to high rate of metabolic damage. |

| Accumulation of damaged mitochondria results in an increased generation of reactive oxygen species which in turn amplifies the damage to other organelles. |

| Damaged but not recycled organelles occupy intracellular space and prevent normal mitogenesis. |

|

| The aggregation of Aβ42 cannot be spontaneously initiated in the interstitial fluid due to a very low concentration of peptide (around 1 nanoM). |

| Endocytosed Aβ42 is concentrated inside lysosomes up to 100-fold and can be observed intracellularly for more than 48 hours [16]. |

| Estimated intralysosomal Aβ42 concentration and the length of Aβ42 presence inside lysosomes allow for the initiation of amyloid aggregation [25]. |

| Aggregated Aβ42 is resistant to proteolytic digestion and can be sequestered inside cells. |

|

| As an alternative to intracellular sequestration, non-digested Aβ42, including aggregated peptide, is exocytosed. |

| When exposed to Aβ42, cultured cells in vitro promote beta-amyloid aggregation [26,27]. |

|

| Higher intensity of endocytosis results in increased production of aggregation seeds to the interstitial fluid. |

|

| Organism level |

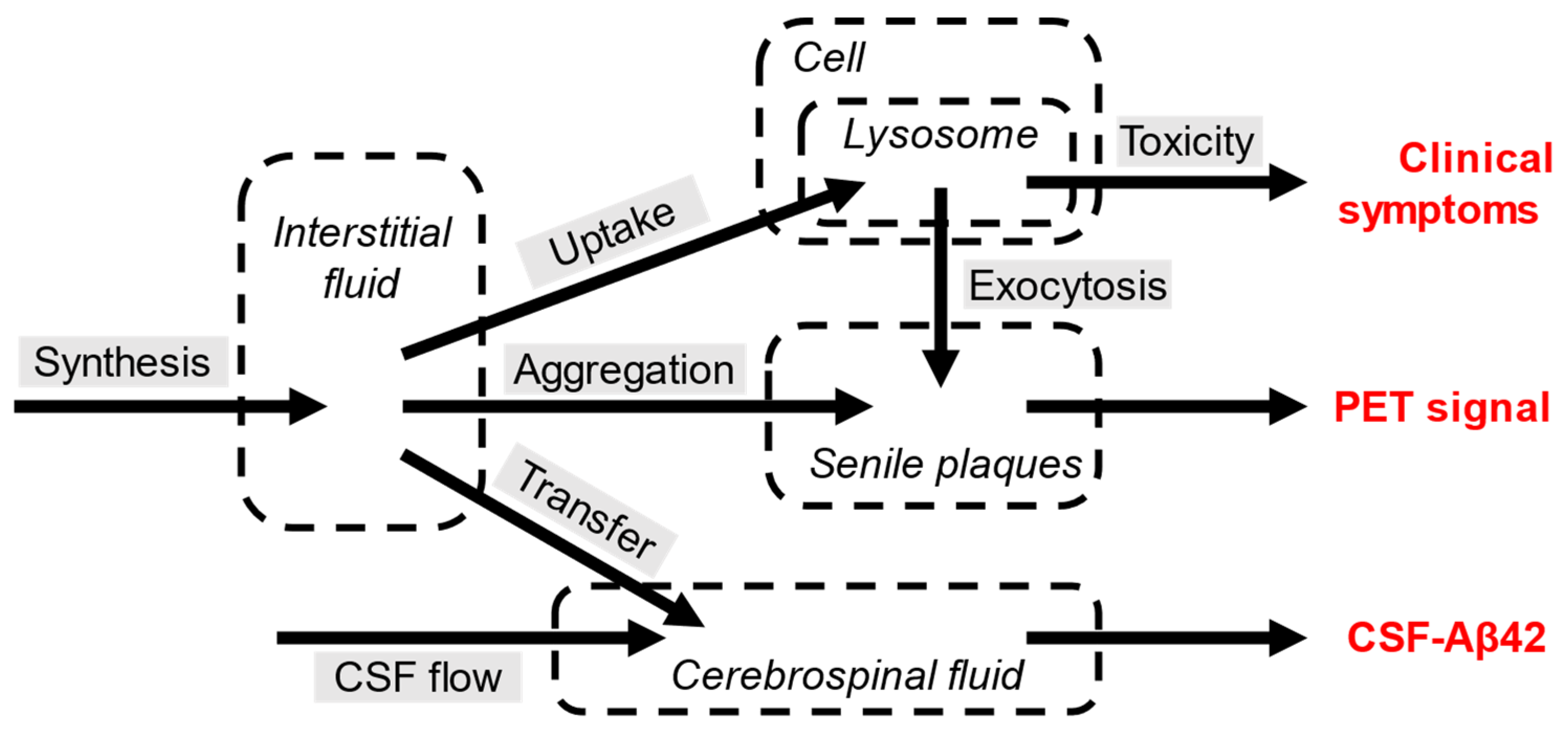

| Both the cytotoxicity and the appearance of senile plaques are the consequence of the same initial process - endocytosis of Aβ42. |

|

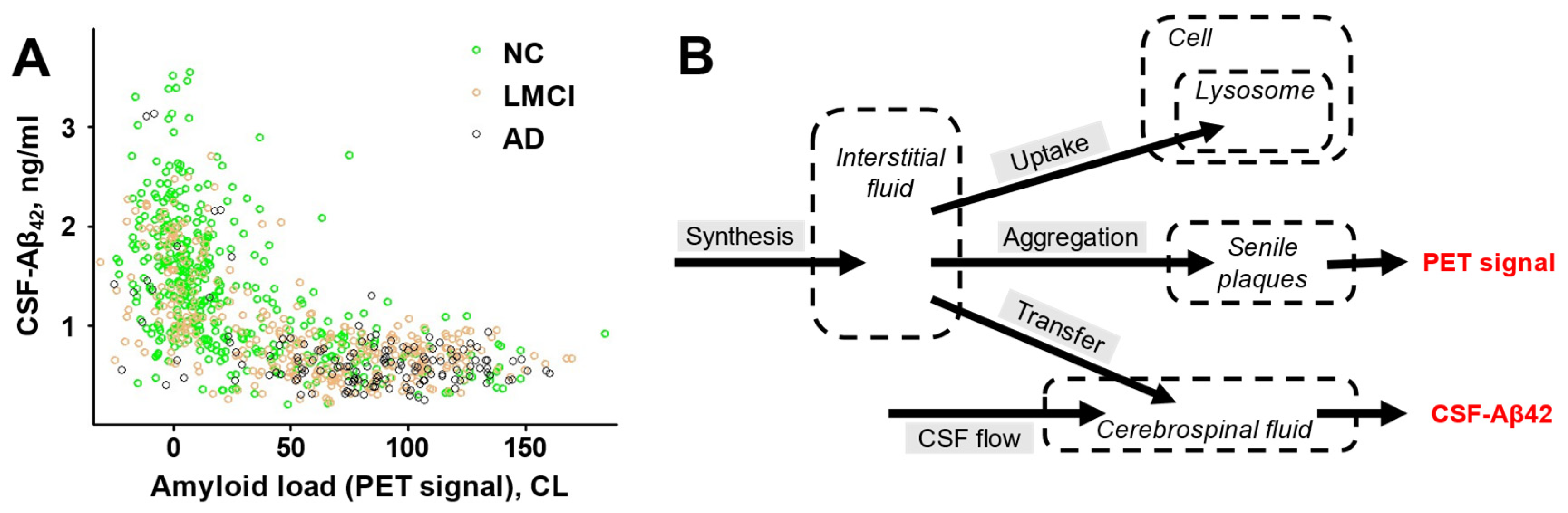

| The density of amyloid deposits can be measured in living subjects by positron emission tomography (PET) using appropriate positron-emitting probes. |

|

| In patients with AD, the concentration of Aβ42 in the CSF is lower compared with the concentration in the subjects with normal cognition. |

| Synthesis of Aβ42 in patients with AD is not different from subjects with normal cognition [28,29]. |

| In patients with AD, CSF flow is either the same or lower than in subjects with normal cognition [30,31]. |

|

| Existing amyloid aggregates serve as aggregation centers for soluble Aβ42. |

| If the density of existing aggregates is high, more freshly synthesized Aβ42 aggregates. |

| If higher ratio of freshly synthesized Aβ42 is aggregating, the concentration of Aβ42 in the interstitial fluid becomes lower, so less Aβ42 is transported to the CSF. |

| Patients with AD have higher density of amyloid deposits. |

|

| The density of amyloid deposits, which is the biomarker of AD, is the major determinant of the level of Aβ42 in the CSF. |

|

|

| According to multivariate correlation analysis, CSF-Aβ42 levels and PET imaging data have independent predictive powers for AD diagnostics, even though these two biomarkers are highly correlated [33]. |

|

| If to compare the concentration of Aβ42 in the CSF of patients with AD and subjects with normal cognition with the same density of amyloid deposits, the Aβ42 concentration in patients with AD is significantly lower [29,34]. |

|

| The rate of removal with the CSF is not higher in patients with AD compared with the subjects with normal cognition, so this additional process occurs inside the brain. |

| The synthesis rate of Aβ42 is not different between patients with AD and subjects with normal cognition [28,29]. |

|

| High ratio of patients with high density of amyloid aggregates also have advanced neurodegeneration, but some of them have no cognitive deficiencies at all. |

| For each given density of amyloid deposits, there is a maximal concentration of Aβ42 in the CSF that can be observed [29,35]. |

| Subjects with the highest possible concentrations of Aβ42 in the CSF for a given amyloid deposits density have very low probability of AD [34]. |

| Increased aggregation-independent intrabrain removal of Aβ42 results in the decrease of Aβ42 concentration in the CSF [29]. |

|

| Most of intrabrain Aβ42 removal is mediated by proteolytic degradation. |

| Most proteases are located intracellularly. |

| To be degraded by proteases, Aβ42 needs to be internalized by cells. |

| Major way of Aβ42 cellular uptake is endocytosis. |

|

| Endocytosis is the initial step of beta-amyloid neurotoxicity. |

|

| Stable isotope labeling kinetics (SILK) technique enables the investigation of beta-amyloid turnover in the brain of living patients [28,36]. |

| SILK studies showed increased irreversible intrabrain removal of Aβ42 in AD patients which can be observed even in the absence of existing plaques [37]. |

|

| SILK studies also demonstrated that patients with mutation-induced AD are characterized by the presence of “exchange pool” of freshly synthesized Aβ42. In subjects with normal cognition, the size of such pool is not statistically different from zero [37]. |

| Increased endocytosis of Aβ42 is associated with the exocytosis of non-aggregated intralysosomal Aβ42 which is exocytosed along with amyloid aggregation seeds. |

|

| Increased cellular uptake of Aβ42 is one of reasons for the increased production of channel-forming fragments, but there could be other reasons. |

| Increased activity of proteases producing channel-forming fragments and/or decreased activity of proteases degrading fragments would result in higher concentration of toxic fragments. Such disbalance would increase beta-amyloid toxicity without increased uptake. |

| Cellular Aβ42 uptake in patients with early-onset AD is not different from uptake in subjects with normal cognition [29]. The early-onset AD is most likely characterized by higher toxicity of endocytosed Aβ42. |

|

| Population level |

| The probability of the disease in a particular patient increases with increased accumulated cellular uptake of Aβ42. |

|

| Cellular uptake defines the toxic insult made by beta-amyloid, but the level of neuronal death, severity of clinical symptoms, and eventually the diagnosis of AD depends on the individual relative toxicity of endocytosed beta-amyloid. |

| The ability of lysosomal proteases to produce and degrade channel-forming fragments defines relative toxicity of endocytosed amyloid. Also, the ability of cells to resist the consequences of lysosomal permeabilization has individual variability (for example, due to different levels of cytoplasmatic protease inhibitors). |

| There is a wide variability of sensitivity (resistance) to toxic action of beta-amyloid. |

|

| High endocytosis of beta-amyloid leads to increased accumulation of amyloid aggregates (higher amyloid load, higher amyloid PET signal) |

|

| The same process - endocytosis of Aβ42 – initiates both neurotoxicity and amyloid aggregation. |

| Both accumulated cytotoxicity and the density of senile plaques are increasing over time (and, correspondingly, with age). |

| The model, which describes the turnover of Aβ42 as the interaction between synthesis, transfer to the CSF, aggregation on existing plaques, and cellular uptake of the peptide can be expressed as the system of differential equations. |

| In modeling, the probability of AD diagnosis can be approximated as a sigmoid function of accumulated amount of endocytosed beta-amyloid. At low accumulated uptakes, until some threshold is reached, the neurotoxicity can be compensated, so the probability of AD diagnosis is close to zero. At highest accumulated uptakes, neuronal death reaches levels when the probability of AD diagnosis approaches 100% and cannot be increased anymore. |

| Clinical dataset, which contains values of amyloid deposits density and levels of Aβ42 in the CSF in populations of patients with AD and subjects with normal cognition (ADNI database), was used to infer the parameters of the model [38]. |

|

| A goodness-of-fit test confirms that the model reproduces clinical data accurately [38]. |

|

| Amyloid degradation toxicity hypothesis as the integrative theory of Alzheimer’s disease |

| The hypothesis was described at all levels of biological organization – from molecular to population. |

| The hypothesis suggests the etiology and pathophysiology of the disease. |

|

There are two major paradoxes in any amyloid-centric theory of AD:

|

|

| AD is characterized by lysosomal failure, lysosomal permeabilization, activation of apoptosis, accumulation of intracellular amyloid aggregates, mitochondrial disfunction, increased reactive oxygen species production, lower brain metabolism, accumulation of tau protein etc. |

| The general human population is characterized by a particular distribution of amyloid biomarkers. |

|

| The hypothesis explains why currently used amyloid-based biomarkers of AD (brain amyloid load and level of Aβ42 in the CSF) are associated with the pathophysiology of AD. |

| Both amyloid biomarkers provide indirect measures of parameters relevant to the etiology of AD. |

|

| The hypothesis interprets various phenomena associated with AD. |

|

| The hypothesis identifies processes which are relevant to AD pathophysiology and can be quantitatively characterized in a patient. |

| The rate of cellular amyloid uptake is likely to be the most informative parameter. There are tested approaches to measure this rate in clinical practice. |

|

| The hypothesis explains why currently used treatments do not prevent the progression of the disease. |

| The hypothesis explains why dissolving amyloid deposits did not result in a reliable clinical effect. |

| The hypothesis identifies the etiology of AD and involved biochemical and cellular pathways. |

| The etiology and pathways involved in the AD contain druggable targets (for example, proteases can be inhibited). |

|

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

References

- Demuro, A. , et al., Calcium Dysregulation and Membrane Disruption as a Ubiquitous Neurotoxic Mechanism of Soluble Amyloid Oligomers. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2005. 280(17): p. 17294-17300. [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, Y. , et al., Soluble amyloid oligomers increase bilayer conductance by altering dielectric structure. J Gen Physiol, 2006. 128(6): p. 637-47. [CrossRef]

- Valincius, G. , et al., Soluble amyloid beta-oligomers affect dielectric membrane properties by bilayer insertion and domain formation: implications for cell toxicity. Biophys J, 2008. 95(10): p. 4845-61.

- Arispe, N., E. Rojas, and H.B. Pollard, Alzheimer disease amyloid beta protein forms calcium channels in bilayer membranes: blockade by tromethamine and aluminum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1993. 90(2): p. 567-571. [CrossRef]

- Arispe, N., H. B. Pollard, and E. Rojas, Giant multilevel cation channels formed by Alzheimer disease amyloid beta-protein [A beta P-(1-40)] in bilayer membranes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1993. 90(22): p. 10573-10577. [CrossRef]

- Mirzabekov, T. , et al., Channel formation in planar lipid bilayers by a neurotoxic fragment of the beta-amyloid peptide. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 1994. 202(2): p. 1142-1148.

- Zaretsky, D.V. and M.V. Zaretskaia, Flow cytometry method to quantify the formation of beta-amyloid membrane ion channels. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr, 2020: p. 183506. [CrossRef]

- Zaretsky, D.V. and M. Zaretskaia, Degradation Products of Amyloid Protein: Are They The Culprits? Curr Alzheimer Res, 2020. 17(10): p. 869-880.

- Alarcon, J.M. , et al., Ion channel formation by Alzheimer's disease amyloid beta-peptide (Abeta40) in unilamellar liposomes is determined by anionic phospholipids. Peptides, 2006. 27(1): p. 95-104.

- Durell, S.R. , et al., Theoretical models of the ion channel structure of amyloid beta-protein. Biophys J, 1994. 67(6): p. 2137-45. [CrossRef]

- Arispe, N., H. B. Pollard, and E. Rojas, Zn2+ interaction with Alzheimer amyloid beta protein calcium channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1996. 93(4): p. 1710-1715. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-c.A. and B.L. Kagan, Electrophysiologic properties of channels induced by Abeta25-35 in planar lipid bilayers. Peptides, 2002. 23(7): p. 1215-1228.

- Zaretsky, D.V., M. V. Zaretskaia, and Y.I. Molkov, Membrane channel hypothesis of lysosomal permeabilization by beta-amyloid. Neurosci Lett, 2021: p. 136338. [CrossRef]

- Zaretsky, D.V. and M.V. Zaretskaia, Mini-review: Amyloid degradation toxicity hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett, 2021. 756: p. 135959. [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, F.J. , et al., Synaptotoxicity of Alzheimer Beta Amyloid Can Be Explained by Its Membrane Perforating Property. PLoS ONE, 2010. 5(7): p. e11820. [CrossRef]

- Wesén, E. , et al., Endocytic uptake of monomeric amyloid-β peptides is clathrin- and dynamin-independent and results in selective accumulation of Aβ(1-42) compared to Aβ(1-40). Scientific reports, 2017. 7(1): p. 2021-2021.

- Solé-Domènech, S. , et al., Lysosomal enzyme tripeptidyl peptidase 1 destabilizes fibrillar Aβ by multiple endoproteolytic cleavages within the β-sheet domain. 2018. 115(7): p. 1493-1498. [CrossRef]

- Abramov, A.Y., L. Canevari, and M.R. Duchen, Changes in intracellular calcium and glutathione in astrocytes as the primary mechanism of amyloid neurotoxicity. J Neurosci, 2003. 23(12): p. 5088-95. [CrossRef]

- Abramov, A.Y., L. Canevari, and M.R. Duchen, Calcium signals induced by amyloid β peptide and their consequences in neurons and astrocytes in culture. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research, 2004. 1742(1): p. 81-87. [CrossRef]

- Zaretsky, D.V. and M.V. Zaretskaia, Intracellular ion changes induced by the exposure to beta-amyloid can be explained by the formation of channels in the lysosomal membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res, 2021: p. 119145. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.J. , et al., Loss of endosomal/lysosomal membrane impermeability is an early event in amyloid Abeta1-42 pathogenesis. J Neurosci Res, 1998. 52(6): p. 691-8.

- Ji, Z.S. , et al., Apolipoprotein E4 potentiates amyloid beta peptide-induced lysosomal leakage and apoptosis in neuronal cells. J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(24): p. 21821-8.

- Hyder, F., D. L. Rothman, and M.R. Bennett, Cortical energy demands of signaling and nonsignaling components in brain are conserved across mammalian species and activity levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(9): p. 3549-54. [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.J., R. Jolivet, and D. Attwell, Synaptic energy use and supply. Neuron, 2012. 75(5): p. 762-77. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.I.A. , et al., Proliferation of amyloid-β42 aggregates occurs through a secondary nucleation mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013. 110(24): p. 9758-9763. [CrossRef]

- Jin, S. , et al., Amyloid-β(1-42) Aggregation Initiates Its Cellular Uptake and Cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem, 2016. 291(37): p. 19590-606. [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, R.P. , et al., Mechanism of amyloid plaque formation suggests an intracellular basis of Aβ pathogenicity. 2010. 107(5): p. 1942-1947. [CrossRef]

- Mawuenyega, K.G. , et al., Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Science (New York, N.Y.), 2010. 330(6012): p. 1774-1774.

- Zaretsky, D.V., M. V. Zaretskaia, and Y.I. Molkov, Patients with Alzheimer's disease have an increased removal rate of soluble beta-amyloid-42. PLoS One, 2022. 17(10): p. e0276933. [CrossRef]

- Fishman, R.A. , The cerebrospinal fluid production rate is reduced in dementia of the Alzheimer's type. Neurology, 2002. 58(12): p. 1866; author reply 1866. [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, G.D. , et al., The cerebrospinal fluid production rate is reduced in dementia of the Alzheimer's type. Neurology, 2001. 57(10): p. 1763-6.

- Mattsson, N. , et al., Diagnostic accuracy of CSF Ab42 and florbetapir PET for Alzheimer's disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol, 2014. 1(8): p. 534-43.

- Mattsson, N. , et al., Independent information from cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β and florbetapir imaging in Alzheimer's disease. Brain, 2015. 138(Pt 3): p. 772-83.

- Sturchio, A. , et al., High cerebrospinal amyloid-β 42 is associated with normal cognition in individuals with brain amyloidosis. EClinicalMedicine, 2021: p. 100988. [CrossRef]

- Fagan, A.M. , What does it mean to be ‘amyloid-positive’? Brain, 2015. 138(3): p. 514-516.

- Bateman, R.J. , et al., A gamma-secretase inhibitor decreases amyloid-beta production in the central nervous system. Annals of neurology, 2009. 66(1): p. 48-54.

- Potter, R. , et al., Increased in vivo amyloid-β42 production, exchange, and loss in presenilin mutation carriers. Sci Transl Med, 2013. 5(189): p. 189ra77.

- Molkov, Y.I. , et al., Towards the integrative theory of Alzheimer’s disease: linking molecular mechanisms of neurotoxicity, beta-amyloid biomarkers, and the diagnosis. medRxiv, 2022: p. 2022.12.07.22283236.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).