1. Introduction

Smart Living is an innovative lifestyle that leverages technology to improve quality of life, increase efficiency, and minimize waste. This concept is widely studied by scholars and researchers, who emphasize its various dimensions such as technology, security, health, and education [

1]. The Smart Living lifestyle is predicated on the integration of advanced information and communication technology (ICT), smart sensing technology, ubiquitous computing, big data analytics, and intelligent decision-making to achieve efficient energy consumption, better healthcare, and a general improvement of the services offered to the society towards a high standard of living [

2,

3].

From a more general perspective, Smart Living is closely related to the concept of smart cities, which seeks to enhance citizenship characteristics such as awareness, independence, and participation [

4]. It aims to transform life and work through ICT, promoting sustainable economic growth and high quality of life while preserving natural resources through participatory governance [

5]. Central to this concept is creating benefits for citizens, considering their welfare and participation [

6]. Smart Living technologies empower users to access and analyze information related to their lives, including personal health and living conditions [

3]. As proposed by Giffinger et al. [

4], a smart city framework encompasses six main components: smart economy, smart people, smart governance, smart mobility, smart environment, and Smart Living. The integration of stakeholders such as people, machines, devices, and the environment is crucial for the realization of Smart Living, which includes aspects such as smart lighting, smart water, smart traffic, smart parking, smart buildings, smart industry, location/context-based services, and many others [

7].

Although Smart Living is driven by intelligent networking and immersive information, it is essential to emphasize the quality of living facilitated by smart technology under sustainable conditions rather than solely driven by technological innovation [

8]. As the definitions of Smart Living continue to evolve with advancements in real-time monitoring systems, it is essential to adapt smart designs and accommodate smart devices, intelligent technology, and sensors to foster a more sustainable and efficient lifestyle for individuals and communities [

7,

9]. In such a technological landscape, HAR is an integral component of Smart Living, contributing significantly to relevant applications, including home automation, healthcare, safety, and security. In fact, by accurately identifying and interpreting human actions, Smart Living systems can deliver real-time responses, offering support and assistance tailored to individual needs. Recognizing human actions is paramount for effectively implementing any Smart Living application, making it a critical area of research and development in pursuing enhanced quality of life and more efficient, sustainable living environments. From a strictly technological perspective, Context Awareness, Data Availability, Personalization, and Privacy are vital dimensions interwoven with HAR in Smart Living services and applications. Actually, these dimensions are instrumental in tailoring Smart Living systems to better cater to individual needs and preferences while preserving privacy and ensuring the availability of relevant data.

A cornerstone of effective HAR in Smart Living services and applications is context awareness, which involves the intelligent perception and interpretation of surrounding environments and situations [

10]. By comprehending the context in which human activities occur, Smart Living systems can respond more appropriately and adapt to specific circumstances. Furthermore, adaptation is intrinsically linked to personalization, allowing systems to deliver customized experiences and services that cater to each user’s unique preferences and requirements [

11]. Personalization and context awareness work in tandem to create a seamless, intuitive, and user-centric environment that enhances the overall quality of life [

12].

However, implementing context awareness and personalization necessitates collecting, processing, and storing vast amounts of personal data, raising privacy concerns. As Smart Living services and applications become increasingly intertwined with users’ daily lives, protecting sensitive information and maintaining user trust is paramount [

13]. Thus, balancing harnessing data for personalization and preserving privacy is essential. To achieve this equilibrium, advanced privacy-preserving techniques, such as encryption and anonymization, must ensure that user data remains confidential [

14]. Lastly, data availability plays a crucial role in the effective functioning of HAR in Smart Living services and applications. The accessibility and reliability of data are integral to the performance of these systems, as they rely on the continuous flow of information to make informed decisions and deliver personalized experiences. Ensuring data availability is particularly challenging due to the dynamic nature of Smart Living environments and the necessity to maintain data consistency across various platforms and devices. Developing robust data management strategies and infrastructure is critical to successfully implementing HAR in Smart Living services and applications [

15].

This review concentrates on HAR in Smart Living services and applications by examining the contemporary state-of-the-art through the lens of the dimensions mentioned above: Context Awareness, Data Availability, Personalization, and Privacy. This analysis aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current landscape and identify opportunities for further research and development in HAR for Smart Living services and applications by investigating the existing literature, advancements, and trends. By focusing on these dimensions, this review seeks to elucidate the challenges and potential solutions associated with effectively implementing HAR systems in many Smart Living environments, ultimately fostering enhanced quality of life and more efficient, sustainable living conditions.

In the previous authors’ work [

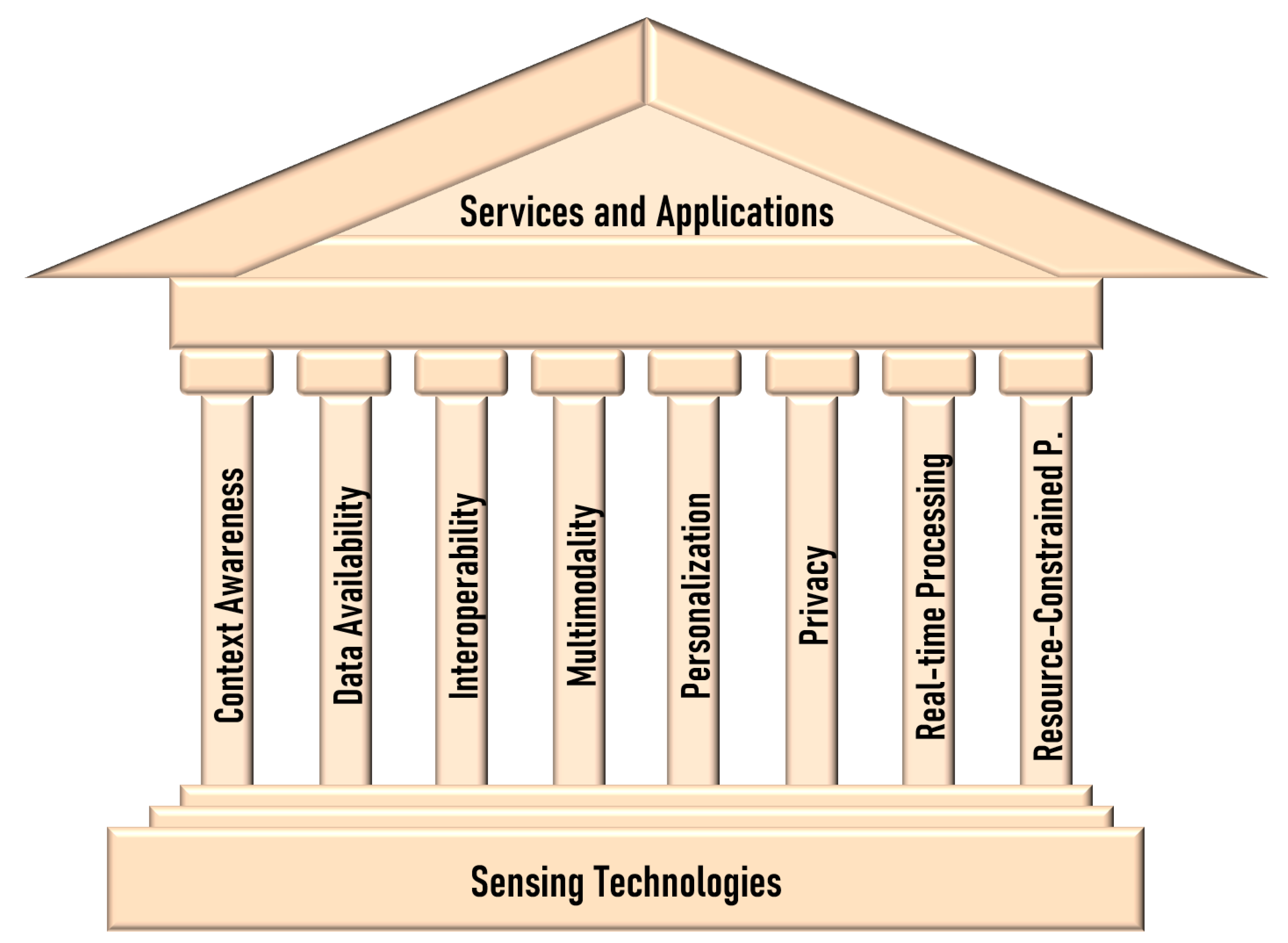

16], the dimensions of Multimodality, Real-time Processing, Interoperability, and Resource-Constrained Processing have been yet analyzed from the perspective of sensing technologies. Composing the dimensions addressed in this review with those previously analyzed outlines what one can define as the temple of Smart Living. Services and applications form the roof, sensor technologies form the floor, and the dimensions mentioned above form the pillars, as depicted in

Figure 1.

The temple of Smart Living represents the culmination of technological advancements, research, and innovation, creating an environment that fosters a higher quality of life, sustainability, and efficiency. At its core, this temple is supported by pillars representing the fundamental dimensions of Smart Living: Context Awareness, Data Availability, Interoperability, Multimodality, Personalization, Privacy, Real-time Processing, and Resource-Constrained Processing. Each pillar contributes to the strength and functionality of the temple, enabling a seamless integration of services, applications, and sensor technologies. This harmonious combination empowers individuals and communities to lead smarter, more connected lives where technology is harnessed to optimize every aspect of daily living.

As we delve into the analysis of the dimensions of Context Awareness, Data Availability, Personalization, and Privacy in the context of HAR for Smart Living services and applications, we will explore how these pillars interact and intertwine, forming the foundation upon which this temple stands. By examining the current state-of-the-art and identifying potential areas for further research and development, we aim to unlock the full potential of HAR systems within the realm of Smart Living. Through this endeavor, we strive to create a future where technology seamlessly integrates with our lives, enhancing our well-being and paving the way for a sustainable and efficient society.

1.1. Background on HAR in general

HAR is an area of research that focuses on identifying and understanding human activities through the analysis of data acquired from various sensors.

It has applications in many fields such as intelligent video surveillance [

17], customer attributes, shopping behavior analysis [

18], healthcare [

19], military [

20], and security [

21]. Despite its potential, HAR remains a challenging task due to cluttered backgrounds, occlusions, viewpoint variations, data noise and artifacts. The recognition of human activities can be approached in two primary ways: using environmental (or ambient) sensors and wearable sensors [

22]. Environmental or ambient sensors are fixed at predetermined points, while wearable sensors are attached to the user. In the case of environmental/ambient sensing, smart homes and camera-based systems are examples of HAR. However, these systems face issues such as privacy, pervasiveness, and complexity [

23,

24].

Deep learning (DL) models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have been shown to yield competitive performance in visual object recognition, human action recognition, natural language processing, audio classification, and other tasks [

25]. CNNs are a type of deep model that learns a hierarchy of features by building high-level features from low-level ones. They have been primarily applied on 2D images, but researchers have started exploring their use for HAR in videos [

26].

HAR systems require two main stages: training and testing (evaluation). The training stage involves collecting time-series data of measured attributes from individuals performing each activity, splitting the time series into time windows, applying feature extraction, and generating an activity recognition model using learning methods. During the testing stage, data is collected during a time window, feature extraction is performed, and the trained learning model is used to generate a predicted activity label. There are several design issues in HAR systems, including the selection of attributes and sensors, obtrusiveness, data collection protocol, recognition performance, energy consumption, processing, and flexibility [

22,

23]. Addressing these issues is crucial for the successful implementation of HAR systems in various real-life applications.

The state-of-the-art HAR systems can be categorized into different groups based on their learning approach, response time, and the nature of the sensors used. Systems can be classified as supervised, semi-supervised, online (often referred also as real-time), offline, and hybrid (combining environmental and wearable sensors). Each of these groups has its own unique challenges and purposes, and they should be evaluated separately.

Hence, HAR is a rapidly evolving field, driven by advancements in DL models, sensor technology, and data processing techniques. The application of CNNs and other DL models to HAR in videos is a promising direction that can potentially improve the performance and capabilities of HAR systems. However, addressing the various design issues and evaluating the performance of HAR systems under realistic conditions remain critical challenges that need to be overcome to fully harness the potential of HAR in various domains.

1.2. Background on HAR in Smart Living Services and Applications

In the context of Smart Living, HAR refers to identifying and analyzing human activities and behaviors using various sensors and computing technologies to provide intelligent, responsive, and personalized services within living environments [

27]. These environments include homes, offices, healthcare facilities, and public spaces. HAR-based applications in Smart Living aim to enhance occupants’ quality of life, safety, and well-being by leveraging technology to automate and adapt to the needs of individuals. The employment of HAR in Smart Living has led to a wide array of practical use cases. In elderly care, for example, HAR systems can be used to monitor daily activities, detect falls, and assess senior citizens’ health status, enabling timely assistance and improving their quality of life [

28]. In smart homes, HAR can facilitate the automation of appliances and lighting based on occupants’ activities and contribute to energy conservation [

29]. In security, HAR can detect and alert occupants of potential intruders or suspicious activities [

30].

Building on the foundations of HAR in Smart Living, several critical dimensions play a significant role in ensuring that these systems are truly effective, adaptable, and user-centric. These dimensions include context awareness, data availability, personalization, and privacy, all of which contribute to the overall functionality and success of the Smart Living experience. Context awareness enables HAR systems to respond intelligently to the varying needs and preferences of occupants in diverse living environments. By incorporating this dimension, Smart Living solutions can better tailor their services, adapting to different situations and ensuring seamless integration into the daily lives of individuals [

31]. On the other hand, personalization empowers users by providing services specifically customized to their needs and preferences, providing a more comfortable, convenient, and intuitive living environment, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for all occupants [

32].

Privacy is a vital aspect of Smart Living, as it helps establish trust and acceptance among users [

33]. Respecting occupants’ privacy by safeguarding their data and ensuring transparency in data collection practices can significantly impact the adoption and success of HAR systems in various living environments. Privacy concerns and ethical considerations are important when implementing HAR systems in Smart Living environments. Ensuring the proper anonymization of data, gaining consent from occupants, and providing transparency in data collection and usage is essential for maintaining trust and user acceptance. Finally, data availability is a crucial dimension that ensures the smooth functioning of HAR systems by providing access to the necessary information for real-time decision-making and analysis [

34]. A robust data infrastructure enables Smart Living solutions to function effectively, adapt to changing circumstances, and deliver a truly intelligent and responsive experience. By incorporating these dimensions into Smart Living solutions, we can create an ecosystem where HAR-based applications work in harmony with the needs and preferences of occupants, ultimately resulting in a more efficient, secure, and personalized living environment.

1.2.1. A Short Note on the Mining of Action

In academic literature, the meaning of the term "action" may vary depending on the context and the authors’ perspective. Some scholars employ the terms "action" and "activity" interchangeably, treating them as synonymous, while others make distinctions between the two.

For a subset of authors, a more structured meaning is assigned to the term "activity" than "action." For instance, they consider the activity of cooking as a complex process consisting of a sequence of more basic actions. Such actions include pouring water into a container, turning on the stove, waiting for the water to boil, and pouring the hot water into a cup. In this view, activities are perceived as interconnected actions contributing to a specific goal.

On the other hand, some authors ascribe even more basic meanings to the term "action." They may classify actions as simple, everyday movements or positions, such as walking, sitting, or lying down. In this perspective, actions are closely related to the concept of static or dynamic postures, representing the various states of an individual’s body during different activities.

In the context of this review paper, the authors have opted to utilize the term "action" with a broader connotation. The chosen definition encompasses a wide spectrum of meanings, ranging from high-level activities, which may be influenced by the context, to more basic static or dynamic postures. This inclusive approach to the term "action" allows for a comprehensive analysis and discussion in the review, incorporating diverse perspectives and interpretations from the academic literature.

This review paper will comprehensively analyze the current state-of-the-art HAR within Smart Living. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: First, we delve into the existing review works in the field, identifying the gaps and motivating the need for this comprehensive study. We then describe the search and inclusion criteria for selecting the relevant literature.

Section 3 presents an overview of the common publicly available datasets used in the studies, followed by a discussion of the widely used performance metrics for evaluating machine learning (ML) algorithms in

Section 4.

Section 5 explores the various dimensions of HAR in Smart Living through the proposed framework. This framework allows us to examine the interplay between different aspects of HAR and Smart Living.

Section 6 presents a critical discussion addressing potential concerns and challenges, offering valuable insights for researchers and practitioners. Finally, we conclude the paper in

Section 7, summarizing our findings and providing some closing considerations for future research and development in HAR in Smart Living services and applications.

2. Review of Related Works and Rationale for This Comprehensive Study

Recent progress in DL methods for human activity recognition (HAR) has been surveyed by Sun et al. [

22], focusing on single-modality and multimodality methods. The need for large datasets, effective fusion and co-learning strategies, efficient action analysis, and unsupervised learning techniques has been emphasized. Saleem et al. [

35] present a comprehensive overview of HAR approaches and trends, proposing a HAR taxonomy and discussing benchmark datasets. They also identify open challenges for future research, including high intra-class variations, inter-class similarities, background variations, and multi-view challenges.

Challenges and trends in HAR and posture prediction are discussed by Ma et al. [

36] discuss, highlighting four main challenges: significant intra-class variation and inter-class similarity, complex scenarios, long untrimmed sequences, and long-tailed distributions in data. They review various datasets, methods, and algorithms and discuss recent advancements and future research directions. Arshad et al. [

23] examine the state of HAR literature since 2018, categorizing existing research and identifying areas for future work, including less explored application domains like animal activity recognition.

A comprehensive survey of unimodal HAR methods is provided by Singh et al. [

37], classifying techniques based on ML concepts and discussing differences between ML and DL approaches. Kong and Fu [

38] survey techniques in action recognition and prediction from videos, covering various aspects of existing methods and discussing popular action datasets and future research directions. Gu et al. [

39] present a comprehensive survey on recent advances and challenges in HAR using DL, examining various DL models and sensors for HAR and discussing key challenges.

Optimal ML algorithms, techniques, and devices for specific HAR applications are examined by Kulsoom et al. [

40], providing a comprehensive survey of HAR. They conclude that DL methods have higher performance and accuracy than traditional ML approaches and highlight future directions, limitations, and opportunities in HAR. Gupta et al. [

41] present a comprehensive review of HAR, focusing on acquisition devices, AI, and applications, and propose that the growth in HAR devices is synchronized with the Artificial Intelligence (AI) framework. They also recommend that researchers expand HAR’s scope in diverse domains and improve human health and well-being.

Bian et al. [

42] present an extensive survey on sensing modalities used in HAR tasks, categorizing human activities and sensing techniques and discussing future development trends in HAR-related sensing techniques, such as sensor fusion, smart sensors, and novel sensors. Ige et al. [

43] survey wearable sensor-based HAR systems and unsupervised learning, discussing the adoption of unsupervised learning in wearable sensor-based HAR and highlighting future research directions. Najeh et al. [

44] explore the challenges and potential solutions in real-time HAR using DL and hardware architectures, analyzing various DL architectures and hardware architectures and suggesting new research directions for improving HAR.

After reviewing the literature, it becomes evident that existing survey and review studies can be broadly categorized into two groups: 1) those providing a comprehensive general overview of the field and 2) those focusing on specific aspects such as ML, DL, sensing, and computer vision. However, it is essential to note that, to the authors’ knowledge, there is a lack of research specifically targeting Smart Living while thoroughly evaluating the existing literature on crucial dimensions essential for Smart Living from the perspective of services and applications.

For this review, an extensive literature analysis was conducted by investigating 511 documents found through a focused Scopus search. This search was constructed to include many pertinent papers by incorporating specific keywords related to HAR and Smart Living. The search employed the following structure:

TITLE (action OR activity OR activities) AND TITLE (recognition OR classification OR classifying OR recognize OR classified OR classifier OR detector OR detecting OR discriminating OR discrimination) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ("smart home" OR "smart building" OR "smart environment" OR "smart space" OR "Smart Living" OR "smart city" OR "smart cities" OR "assisted living" OR "ambient intelligence" OR "smart ambient") AND PUBYEAR > 2019.

The query sought articles featuring titles that incorporated terms associated with actions or activities and their identification, categorization, or discovery. Additionally, the exploration was narrowed to articles containing title-abstract keywords connected to a range of Smart Living scenarios, including smart homes, smart buildings, smart environments, smart cities, and ambient intelligence, among other examples. The query also emphasized publications released in 2020 or later, guaranteeing that the analysis considered the latest developments in the domain. The primary factor for choosing a paper for this review was its relevance to one or more of the aforementioned key aspects of Smart Living. This strategy facilitated the assembly of an extensive and pertinent collection of literature, laying the groundwork for a well-informed and perceptive assessment of HAR within the sphere of Smart Living.

The papers obtained from the above query can be further classified based on the specific themes they address. In particular, the following, possibly overlapped, categories emerge:

Context Awareness

Data Availability

Interoperability

Machine and Deep Learning

Multimodality

Personalization

Privacy

Real-time Processing

Resource-Constrained Processing

Sensing technologies

Services and Applications

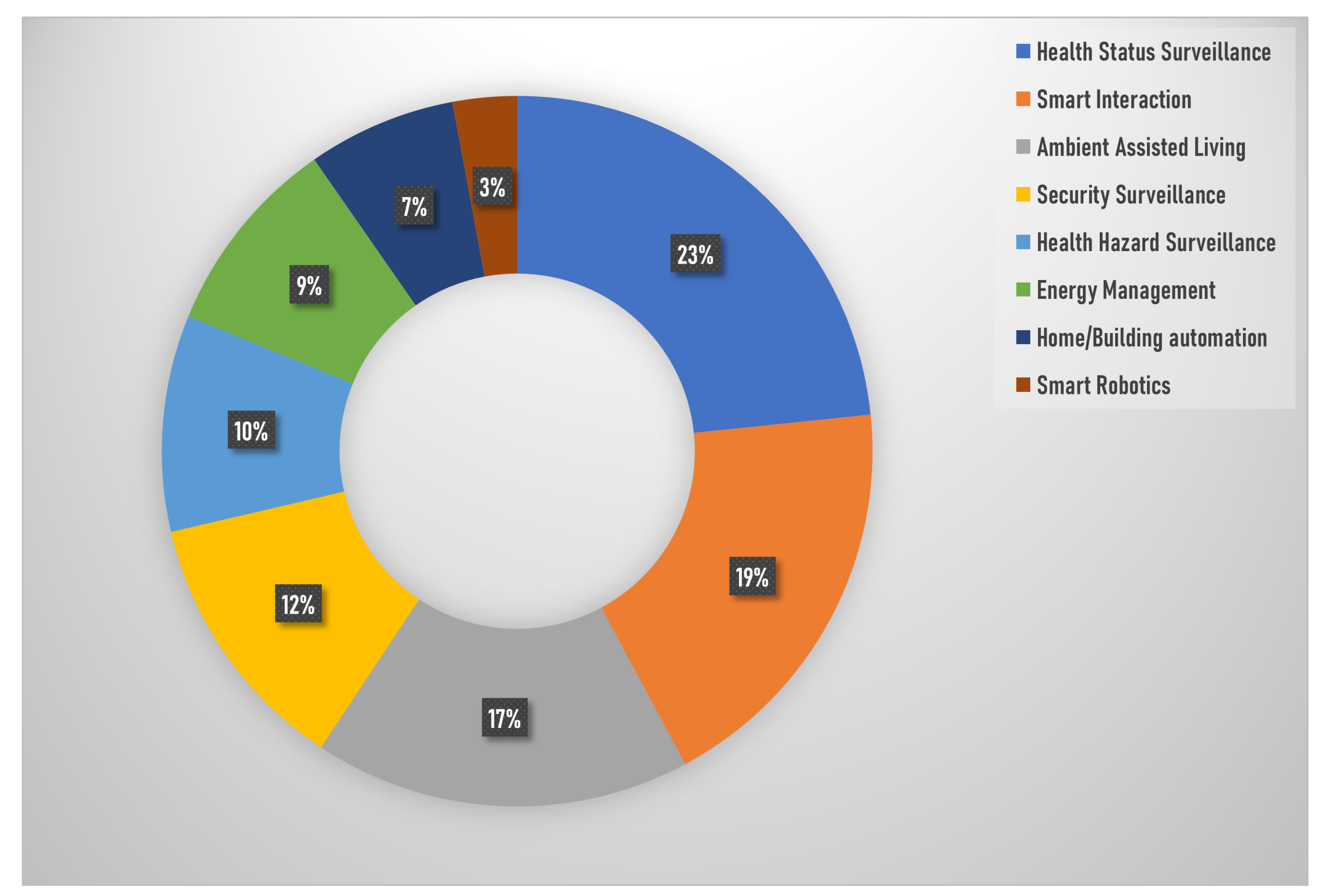

The categories listed above with their respective quantities are represented in

Figure 2. The plot reveals that the most prominent categories are Services and Applications, Machine and Deep Learning, and Sensing Technologies. As said, ML, DL, and sensing have already received extensive coverage in previous review works. Additionally, Interoperability, Multimodality, Real-Time Processing, Resource-Constrained Processing, and Sensing Technologies have been thoroughly analyzed in the previous review study by the authors [

16].

This work aims to explore and analyze the concepts of Context Awareness, Data Availability, Personalization, and Privacy, which have not been given much attention in previous reviews. Moreover, the focus of this work is on services and applications that cover various subjects, as shown in

Figure 3. These subjects are crucial in creating a seamless and intelligent living environment. Here is a brief overview of these aspects:

Health Status Surveillance: Refers to monitoring and assessing an individual’s health-related aspects such as food intake, lifestyle, well-being, physical activity, sleep, and the use of technology like robots or mirrors to support healthcare or anomaly detection.

Smart Interaction: Involves various forms of interactive communication between humans and computers, including hand gestures, natural interaction, brain-computer interfaces, and human-computer interaction.

Ambient Assisted Living (AAL): Encompasses technologies and systems designed to support independent living for older adults or individuals with specific needs, focusing on activities of daily living, active and healthy living, as well as assistive and complex human activities.

Security Surveillance: This relates to using surveillance systems to monitor and detect suspicious or violent activities, ensuring safety and security in various environments.

Health Hazard Surveillance: Involves the monitoring and identifying potential health hazards, such as falls, anomalies, or dangerous situations, particularly in settings like bathrooms.

Energy Management: Refers to strategies and technologies for efficient energy use, including smart meters, energy-saving techniques, power consumption monitoring, and occupancy-based management.

Home/Building Automation: Involves the automation of various tasks and systems within homes or buildings, utilizing ambient intelligence, intelligent appliances, or white goods (such as household appliances).

Smart Robotics: The field of robotics encompasses the development and application of robots in various domains or tasks, enhancing automation and intelligent interaction.

3. Common Publicly Available Datasets

Numerous accessible public datasets are often employed for HAR; however, it is vital to understand that these datasets may not fully address specific requirements for Smart Living services and applications. A key consideration when choosing a dataset for Smart Living services and applications is the kind of human action incorporated within the dataset. The human actions must be pertinent to the Smart Living context and represent individuals’ everyday routines and tasks in their homes, workplaces, or urban settings. This way, it is ensured that the HAR models derived from these datasets cater to the distinct demands of Smart Living solutions.

Another essential factor to consider is the dataset’s subject diversity, including differences in age, gender, and physical capabilities. A broader representation of human activities can be achieved with a diverse group of subjects, which helps create more resilient and versatile HAR models that serve a wider population and can adapt to various individuals and circumstances.

Additional aspects to consider when choosing a dataset for HAR in Smart Living are data quality, the number of sensors utilized, the placement of these sensors, and the duration of recorded activities. These factors can considerably influence the effectiveness and dependability of HAR models, making it crucial to consider them when selecting the most appropriate dataset for a specific application.

In this review, we have meticulously chosen several pertinent datasets extensively used by the research community for HAR studies. These datasets comprise: Opportunity [

45], PAMAP2 [

46], CASAS: Aruba [

47], CASAS: Cairo [

48], CASAS: Kyoto Daily life [

49], CASAS: Kyoto Multiresident [

50], CASAS: Milan [

49], CASAS: Tokyo [

51], CASAS: Tulum [

49], WISDM [

52], ExtraSensory [

53], MHEALTH [

54], UCF101 [

55], HMDB51 [

56], NTU RGB+D [

57], SmartFABER [

58], PAAL ADL Accelerometry [

59], Houses: HA, HB, and HC. [

60], UCI-HAR [

61], Ordonez [

62], Utwente [

63], IITR-IAR [

64].

An overview of the different datasets used by the review works is provided in

Table 1.

4. Performance Metrics

Classification algorithms are evaluated using various metrics. Accuracy (A), Recall (R), Precision (P), F1-score (F1S), macro-F1-score (mF1S), and Specificity (SP) are some commonly used ones. Accuracy (A) is determined by the formula

This metric measures the ratio of correct predictions made by the model to the total number of predictions made. Recall (R), also known as sensitivity or true positive rate, measures the proportion of relevant instances retrieved. It is determined by the formula

Precision (P) represents the proportion of true positives among the predicted positives. It is determined by the formula

The F1-score (F1S) is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing their trade-offs. It is calculated using the formula

The macro-F1-score (mF1S) calculates the average of the F1-scores for each class, treating all classes equally regardless of their size. It is determined using the formula

Lastly, Specificity (SP) is determined by the formula

and measures the proportion of true negatives among the predicted negatives, reflecting the model’s ability to correctly identify negative instances.

Regarding the symbols above, TP, TN, FP, and FN commonly represent different outcomes in a binary classification problem. They are defined as follows:

TP: True Positives - the number of positive cases correctly identified by a classifier.

TN: True Negatives - the number of negative cases correctly identified as negative by a classifier.

FP: False Positives - the number of negative cases incorrectly identified as positive by a classifier.

FN: False Negatives - the number of positive cases incorrectly identified as negative by a classifier.

5. HAR in Smart Living Services and Applications

The analytical framework presented above provides a comprehensive perspective on the various dimensions of HAR in Smart Living. However, it is crucial to analyze each dimension critically to ensure that the development of intelligent living environments addresses potential concerns and challenges. Starting from the corpus of papers obtained with the query indicated above, the most representative papers of the dimensions analyzed, namely Context Awareness, Data Availability, Personalization, and Privacy, have been selected. This selection process ensures that the following state-of-the-art examination is based on highly relevant and significant works in HAR.

To facilitate a systematic and organized presentation, each section in the following schematically reports the selected works for each dimension. Dedicated tables provide concise and structured information about each paper, including the methodology employed, the dataset used, the performances achieved, the sensors adopted, and the most prominent actions considered in each work. These tables not only enhance readability but also serve as a quick reference for understanding the critical aspects of each work.

Moreover, the selected papers also focus on identifying and analyzing the actions most considered in the context of HAR in Smart Living. By prioritizing these actions, researchers can gain insights into the specific human activities that have garnered significant attention in the literature. This approach enables a deeper understanding of the current research landscape and highlights areas that require further investigation and improvement.

By adopting this comprehensive approach, this paper aims to provide a detailed overview of the state of the art in HAR for Smart Living services and applications. Including the most representative papers and providing essential details about each work’s methodology, dataset, performances, sensors, and prioritized actions contribute to a more thorough understanding of the advancements and challenges in this evolving field.

5.1. Context awareness

Context awareness is a key aspect in designing Smart Living environments, where systems recognize, interpret, and respond to various contextual factors, including time, location, user preferences, and activities. By understanding and adapting to users’ contexts, these systems can enhance user experience, promote independence, and facilitate convenience [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70]. Some studies have focused on improving feature extraction and resolving activity confusion by using marker-based Stigmergy, a concept derived from social insects that explains their indirect communication and coordination mechanisms (Xu et al. [

65]). This approach allows for efficient modeling of daily activities without requiring sophisticated domain knowledge and helps protect the privacy of monitored individuals.

Other research has explored context awareness in HAR for multitenant smart home scenarios, developing methodologies that constrain sensor noise during human activities (Li et al. [

66]). By integrating the spatial distance matrix (SDM) with the Contribution Significance Analysis (CSA) method and the broad time-domain CNN algorithm, these approaches ensure accurate and efficient HAR systems. In multi-user spaces, researchers have addressed the challenges of complex sequences of overlapping events by employing transformer-based approaches, such as AR-T (Attention-based Residual Transformer), which extracts long-term event correlations and important events as elements of activity patterns (Kim [

67]). This method has shown improved recognition accuracy in real-world testbeds.

Ehatisham-ul-Haq et al. [

68] propose a two-stage model for activity recognition in-the-wild (ARW) using portable accelerometer sensors. By incorporating the recognition of human contexts, the model provides a fine-grained representation of daily human activities in natural surroundings. Despite its limitations, the proposed method has achieved reasonable accuracy. Buoncompagni et al. [

69] present Arianna+, a framework for designing networks of ontologies that enable smart homes to perform HAR online. This approach focuses on the architectural aspects of accommodating logic-based and data-driven activity models in a context-oriented way, leading to increased intelligibility, reduced computational load, and modularity.

Lastly, Javed et al. [

70] explore context awareness in HAR systems for sustainable smart cities. They propose a framework for HAR using raw readings from a combination of fused smartphone sensors, aiming to capitalize on the pervasive nature of smartphones and their embedded sensors to collect context-aware data. The study reports promising results in recognizing human activities compared to similar studies, achieving an accuracy of 99.43% for activity recognition using Deep Recurrent Neural Network (DRNN).

Moreover, context awareness plays a critical role in the development of intelligent, Smart Living environments, and various research efforts have explored different methodologies and approaches to improve HAR systems by incorporating context-aware information. These advances contribute to the development of sustainable smart cities and healthier societies. The works discussed in this section are summarized in

Table 2.

5.2. Data Availability

Data availability is a major challenge in developing robust HAR systems for Smart Living services and applications. These systems require accurate and diverse data to learn the intricacies of human movements and interactions, yet acquiring sufficient real-world data for training can be time-consuming and expensive. Moreover, publicly available datasets may not adequately represent the diversity of human actions or the specific contexts in which Smart Living services and applications operate. To address these limitations, researchers employ various strategies, such as data augmentation, synthetic data generation, simulation, and transfer learning [

76,

77].

Data augmentation and synthetic data generation techniques help enhance the diversity of training data and mimic real-world situations, enabling models to generalize better and perform well on unseen data.

For instance, Vishwakarma et al. [

76] developed SimHumalator, a simulation tool for generating human micro-Doppler radar data in passive WiFi scenarios. Nan and Florea [

77] employed data augmentation techniques, such as uniform sampling, random movement, and random rotation, to artificially generate new samples for skeleton-based action recognition.

Annotation of collected data is another critical issue, as it is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and often requires domain experts. To mitigate these annotation difficulties, researchers are exploring the use of unsupervised and semi-supervised learning techniques, which take advantage of the vast amounts of unlabeled data to improve the performance of HAR systems without the need for manual annotation [

78,

79]. For example, Riboni et al. [

78] presented an unsupervised technique for activity recognition in smart homes. Their approach utilized HMMs and employed a knowledge-based strategy incorporating semantic correlations between event types and activity classes. The unsupervised method demonstrated a high level of accuracy, comparable to that of the supervised HMM-based technique reported in existing literature. Additionally, Dhekane et al. [

79] proposed a real-time annotation framework for Activity Recognition, leveraging the Change Point Detection (CPD) methodology.

Semantic and ontology-based approaches can significantly address the data availability problem by facilitating the annotation process, supporting data integration from multiple sources, and enabling reasoning and inference [

80]. These approaches can streamline the annotation process by defining a structured and consistent vocabulary for describing human actions, reducing ambiguities and inconsistencies in annotation. Moreover, ontologies can automate certain aspects of the annotation process, reducing the time and effort required by human annotators. By establishing a common semantic framework, researchers can more easily combine and compare datasets, leading to improved performance and generalization in HAR models. Another advantage of semantic and ontology-based approaches is their ability to support reasoning and inference. By capturing relationships and hierarchies between actions, objects, and contexts, these approaches can enable HAR systems to make inferences about unseen or underrepresented actions based on their similarities to known actions [

80]. This can fill gaps in the training data and support the development of more robust models even when faced with limited data.

Leveraging ubiquitous sensing devices, such as smartphones, is another way to address data availability. For example, Liaqat et al. [

81] proposed an ensemble classification algorithm that uses smartphone data to classify different human activities. This approach significantly expands the potential for widespread adoption of HAR systems, ensuring more people, especially older adults, can benefit from ambient assisted living solutions for improved monitoring and support. Moreover, data availability remains a significant challenge in the development of HAR systems for Smart Living services and applications. Researchers are adopting various strategies, including data augmentation, synthetic data generation, simulation, transfer learning, unsupervised and semi-supervised learning, semantic and ontology-based approaches, and the use of ubiquitous sensing devices to overcome this challenge. By enhancing the diversity and quality of training data, these approaches help improve the performance and generalization of HAR models.

The works discussed in this section are summarized in

Table 3.

5.3. Personalization

Personalization is crucial in Smart Living technologies, particularly in the realm of HAR. Recognizing individual uniqueness when performing specific actions can lead to improved recognition accuracy and personalized experiences, overcoming the challenges of a “one-size-fits-all” approach [

83]. Researchers have found that by identifying similarities between a target subject and individuals in a training set, emphasizing data from subjects with similar attributes can enhance the overall performance of HAR models [

84].

CNNs have been successful in HAR due to their ability to extract features and model complex actions. However, generic models often face performance deterioration when applied to new subjects. Studies have proposed personalized HAR models based on CNN and signal decomposition to address this challenge, achieving better accuracy than state-of-the-art CNN approaches with time-domain features [

83]. In healthcare applications, personalization has been explored for classifying normal control individuals and early-stage dementia patients based on Activities of Daily Living (ADLs). Studies have demonstrated that personalized models, considering individual cognitive abilities, exhibit higher accuracy than non-personalized models, underlining the importance of personalization in classifying normal control and early-stage dementia patients [

85].

Several studies have proposed novel approaches for sensor-based HAR that focus on personalization by maintaining the ordering of time steps, crucial for accurate and robust HAR systems. They have introduced network architectures combining dilated causal convolution and multi-head self-attention mechanisms, offering a more personalized and efficient solution for sensor-based HAR systems [

86]. Researchers have also explored personalized approaches for HAR within smart homes by utilizing a multilayer perceptron (MLP) neural network. The proposed method adapts to individual users’ patterns and habits, achieving high recognition accuracy across all activity classes [

87]. Recent work has focused on addressing the challenges associated with recognizing complex human activities using sensor-based HAR.

By exploring hybrid DL models combining convolutional layers with Recurrent Neural Network (RNN)-based models, researchers have demonstrated the potential of these models to contribute significantly to personalization in various applications involving wearable sensor data [

88].

To address the challenge of personalization in sensor-based HAR, particularly in healthcare applications, studies have proposed unsupervised domain adaptation approaches that allow sharing and transferring of activity models between heterogeneous datasets without requiring activity labels for the target dataset. This approach enhances the personalization aspect of activity recognition models, allowing adaptation to new, unlabeled datasets from different individuals or settings [

89].

Furthermore, personalization plays a vital role in enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of HAR models. By considering individual uniqueness and utilizing various techniques such as CNNs, RNN-based models, and unsupervised domain adaptation, researchers have made significant strides in creating more tailored and accurate HAR systems for Smart Living and healthcare applications.

The works discussed in this section are summarized in

Table 4.

5.4. Privacy

Privacy concerns in HAR have been addressed through two primary aspects: sensor choice and data security. Researchers have focused on exploring sensing modalities that do not capture privacy-sensitive information. Device-free sensing approaches have emerged as a viable alternative to intrusive body-worn or ambient-installed devices, with examples such as WiFi and radar-based sensors [

91,

92,

93,

94]. Privacy-preserving techniques have also been developed for traditional audio and video-based methods, using inaudible frequencies or occluding person data [

95,

96,

97]. Studies have demonstrated the importance of contextual information in HAR and its potential for preserving privacy without sacrificing performance [

97].

Researchers have also developed privacy-preserving HAR systems using low-resolution infrared array sensors, showcasing promising recognition accuracy [

98]. Furthermore, inaudible acoustic frequencies have been explored for daily activity recognition, resulting in privacy-preserving accuracies of up to 91.4% [

95]. Data security has been addressed through local training via federated architecture, preventing data from being sent to third parties [

99]. Detection of spoofing attacks in video replay and vulnerability to adversarial attacks in video and radar data have also been investigated [

100,

101].

Diversity-aware activity recognition frameworks based on federated meta-learning architecture have been proposed, which preserve privacy-sensitive information in sensory data and demonstrate competitive performance in multi-individual activity recognition tasks [

99]. Studies have also revealed radar-based CNNs’ vulnerability to adversarial attacks and a connection between adversarial optimization and interpretability [

100]. Lightweight DL-based algorithms capable of running alongside HAR algorithms have been developed to detect and report cases of video replay spoofing [

101].

Researchers have proposed novel methodologies for explainable sensor-based activity recognition in smart-home environments, transforming sensor data into semantic images while preserving privacy [

102]. Federated learning has also been leveraged to develop personalized HAR frameworks, allowing training data to remain local and protecting users’ privacy [

103]. The studies collectively contribute to addressing privacy concerns and advancing HAR research. In this section, privacy concerns in HAR have been addressed by focusing on sensor choice and data security. Researchers have explored device-free sensing approaches that do not require intrusive sensors and developed privacy-preserving techniques for traditional audio and video-based methods. Contextual information has been shown to play a crucial role in HAR performance and privacy preservation. Data security has been enhanced through federated learning and local training, reducing the need to share data with third parties. Research has also investigated vulnerability to adversarial attacks, spoofing detection, and the connection between adversarial optimization and interpretability. Innovative methodologies have been developed to provide explainable activity recognition while preserving privacy in smart-home environments. Federated learning has been employed to create personalized HAR frameworks that protect users’ privacy. These studies collectively represent the state-of-the-art in addressing privacy concerns in HAR and pave the way for advancements in the field, ensuring that users’ privacy is maintained while delivering reliable recognition performance.

The works discussed in this section are summarized in

Table 5.

6. Smart Living Services and Applications

HAR systems have shown great potential in enhancing Smart Living services and applications, spanning diverse areas such as Assisted Living, Health Status Surveillance, Health Hazard Surveillance, Energy Management, Security Surveillance, and Natural Interaction. These applications aim to improve the lives of seniors, monitor health conditions, optimize energy consumption, and enhance security across various settings by utilizing cutting-edge ML techniques, sensor data, and innovative strategies like radar phase information and WiFi-based recognition [

108,

109].

HAR systems have been particularly effective in Assisted Living applications, improving the quality of life for elderly individuals and those with chronic conditions, while supporting healthcare professionals and caregivers in providing more effective care [

19,

108]. For instance, HAR has been used to monitor the daily routines of older persons and detect deviations in their behavior, as well as to recognize fall activities and notify caregivers or medical professionals during emergencies [

109,

110]. HAR systems can also identify ADLs in smart home environments and provide valuable information about older adults’ health conditions to family members, caretakers, or doctors, helping to adapt care plans as needed [

19].

Health Status Surveillance plays a significant role in Smart Living services and applications, addressing the needs of an aging population and patients with neurodegenerative disorders. ML and signal processing techniques, such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and Random Decision Forest classifiers, can be employed to disaggregate domestic energy supplies and assess ADLs [

111]. Preventive healthcare can also be supported by recognizing dietary intake using DL models like EfficientDet [

112] and monitoring physical activity through smartphone accelerometer sensor data and DL models [

113].

Health Hazard Surveillance is essential for the well-being and safety of elderly populations in Smart Living services and applications. HAR systems can help monitor older adults’ daily activities, identify potential hazards, and alert caregivers or medical professionals in emergencies. This approach allows for timely intervention and can prevent the exacerbation of health conditions or accidents, ensuring a safer environment for seniors [

114,

115].

Energy management in smart homes and buildings can be improved by incorporating HAR into Smart Living services and applications. By understanding and monitoring human behavior, these systems can optimize energy consumption while maintaining comfort for the occupants. HAR can be employed to optimize energy consumption in Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems [

116] and in Building Energy and Comfort Management (BECM) systems by learning users’ habits and preferences and predicting their activities and appliance usage sequences [

117].

Security surveillance can be significantly enhanced by applying HAR in Smart Living environments. Accurate identification and classification of activities based on visual or auditory observations can contribute to a safer, more secure environment in various contexts. This can be achieved through approaches like using a fine-tuned YOLO-v4 model for activity detection combined with a 3D-CNN for classification purposes [

118] and employing SVM algorithms to classify activities based on features extracted from audio samples [

119].

In addition to enhancing security surveillance in various settings, such as video surveillance, healthcare systems, and human-computer interaction, HAR systems can provide accurate activity detection and recognition, offering valuable insights for security personnel in real-world scenarios like university premises or urban environments [

118,

119]. By incorporating radar phase information and WiFi-based approaches, HAR systems can significantly improve natural interaction in Smart Living services and applications, providing low-latency, real-time processing, and touch-free sensing benefits for various applications, including elder care, child safety, and smart home monitoring [

120,

121].

Natural interaction in Smart Living services and applications can be improved by recognizing human actions and gestures in a non-intrusive, privacy-preserving manner. Exploiting radar phase information and WiFi-based approaches in HAR can enhance natural interaction significantly in Smart Living services and applications, providing low-latency, real-time processing, and touch-free sensing benefits. Recent advancements in radar phase information extraction from high-resolution Range Maps (RM) offer a promising alternative to traditional methods, such as micro-Doppler spectrograms, which suffer from time-frequency resolution trade-offs and computational constraints [

120]. The Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) algorithm can capture unique shapes and patterns in the wrapped phase domains, demonstrating high classification accuracy of over 92% in datasets of arm gestures and gross-motor activities. By employing various classification algorithms, such as Nearest Neighbor, linear SVM, and Gaussian SVM, improved performance and robustness in various activity aspects, including the aspect angle and speed of performance, can be achieved [

120].

The ubiquity of WiFi devices in modern buildings provides an opportunity for cost-effective, touch-free activity and gesture recognition systems. Human activities and gestures can be accurately recognized by harnessing the Channel State Information (CSI) value provided by WiFi devices [

121]. Median filtering techniques can be applied to filter out noise from the CSI, and massive features can be extracted to represent the intrinsic characteristics of each gesture and activity. Using data classification algorithms, such as Random Forest Classifier (RFC) and SVM with cross-validation techniques, can achieve high recognition accuracy rates of up to 92% and 91%, respectively [

121].

Overall, the integration of HAR systems into Smart Living services and applications offers a promising avenue for enhancing the lives of seniors, monitoring health conditions, optimizing energy consumption, and bolstering security across various settings. With continued advancements in ML, sensor technology, and innovative recognition strategies, the potential of HAR systems in Smart Living services and applications will undoubtedly continue to grow, paving the way for more sustainable, secure, and supportive living environments.

The works discussed in this section are summarized in

Table 6.

7. Discussion: Open Issues and Future Research Directions

The integration of multiple sensing technologies is a promising research direction for improving HAR systems in Smart Living services and applications. Combining data from various sensor types, such as wearable devices, cameras, and ambient sensors, can yield richer contextual information and lead to more accurate and reliable activity recognition. As each sensor type has its strengths and weaknesses, their integration can compensate for individual limitations and provide a more comprehensive understanding of users’ activities. Future research should explore efficient sensor fusion techniques and investigate how to effectively exploit complementary sensor data for improved activity recognition.

Federated learning presents another avenue for future research in HAR, with potential benefits in both performance improvement and privacy preservation. By enabling data sharing across multiple devices, federated learning allows HAR systems to learn from diverse, real-world data without directly accessing users’ sensitive information. This approach can lead to more robust models that can better generalize to different populations and contexts while respecting users’ privacy. Researchers should focus on optimizing federated learning algorithms, as well as addressing challenges related to communication efficiency, data heterogeneity, and security in distributed learning settings.

Another vital aspect of HAR in Smart Living services and applications is human-centered design. A multidisciplinary approach that involves collaboration between computer scientists, engineers, psychologists, and social scientists is essential for ensuring that HAR systems meet the diverse needs and preferences of end-users. By prioritizing user experience and incorporating insights from various fields, researchers can develop more intuitive, adaptable, and user-friendly HAR systems that seamlessly integrate into people’s everyday lives. Future research should emphasize the importance of human-centered design principles, investigate novel interaction modalities, and explore methods for eliciting user feedback and preferences to inform system development.

The importance of overall system design, particularly emphasizing low-power consumption and lightweight processing, must be considered for Smart Living services and applications. Despite this, many studies still need adequate attention to these crucial aspects. As smart environments frequently face limitations in energy consumption, device size, and battery life, developing energy-efficient and lightweight solutions becomes imperative. Energy-harvesting wearable devices, which can capture and store energy from various sources like solar, thermal, or kinetic energy, can significantly mitigate energy consumption concerns. Employing such energy-harvesting methods makes it possible to extend the battery life of wearable devices or even eliminate the need for batteries, substantially reducing the system’s overall energy consumption. Additionally, low-power ML algorithms for HAR can help minimize energy usage without compromising performance. These algorithms can be designed to run on resource-constrained devices, such as microcontrollers or edge devices, enabling HAR to be processed locally. This reduces the need for transmitting data to the cloud, which can be power-intensive, and results in lower latency and increased privacy. To further enhance the energy efficiency of Smart Living services and applications, it is important to optimize both hardware and software components. This optimization could involve employing energy-efficient processors, memory, and communication modules on the hardware side. On the software side, researchers can focus on developing lightweight algorithms that require minimal computational resources and can adapt dynamically to the available energy budget. Smart Living services and applications can become more viable and sustainable in the long run by prioritizing low-power consumption and lightweight processing in the overall system design.

Multi-resident HAR represents an important area for further exploration, as most existing studies concentrate on single-occupant scenarios. The ability to accurately detect and analyze the actions of multiple individuals in a shared environment opens up many practical applications, addressing diverse needs across various sectors. In assisted living facilities, for instance, multi-resident HAR can significantly enhance residents’ quality of care and support. By simultaneously monitoring the activities of multiple individuals, caregivers can receive real-time updates on each resident’s well-being, enabling timely interventions if necessary. It is particularly beneficial for detecting falls, wandering, or other behaviors requiring immediate attention, ultimately contributing to a safer and more responsive living environment. Smart homes also stand to benefit greatly from advancements in multi-resident HAR. By recognizing the activities of various family members, smart home systems can make personalized environmental adjustments, such as controlling lighting, temperature, and entertainment settings based on individual preferences and habits. Additionally, multi-resident HAR can bolster security measures by identifying and differentiating between authorized family members and potential intruders. Addressing the challenges associated with multi-resident HAR will likely involve refining existing techniques and developing novel approaches. For example, researchers may need to devise innovative ways to differentiate between the actions of multiple individuals, even when their activities overlap or occur nearby. Furthermore, integrating data from various sensor types, including wearable devices, cameras, and ambient sensors, could enhance the accuracy and reliability of multi-resident HAR systems.

Lastly, it is essential to address ethical considerations and privacy concerns in Smart Living environments that employ HAR systems. While recent advances in privacy-preserving techniques have made some progress, privacy remains a significant concern in HAR. Researchers should continue exploring ways to develop secure and privacy-preserving HAR systems that protect individuals’ data and privacy, such as through differential privacy, homomorphic encryption, or secure multi-party computation. In addition, the vulnerability of HAR models to adversarial attacks and the connection between adversarial optimization and interpretability warrant further investigation. Developing explainable HAR models that provide transparent and interpretable insights into their decision-making processes can help build trust and facilitate user acceptance of these systems in Smart Living services and applications.

8. Conclusion

This comprehensive review has meticulously examined the role of HAR within the realm of Smart Living, delving into its various dimensions and pinpointing both the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead for future research. The proposed framework emphasizes the critical importance of context awareness, data availability, personalization, and privacy, in the context of Smart Living services and applications. Through a critical analysis of these aspects, this review accentuates the necessity to tackle biases and inaccuracies, manage the complexity and privacy concerns, strike a balance between real-time processing and resource efficiency, and prioritize privacy-preserving techniques.

As we look to the future, researchers should concentrate on refining and amalgamating data availability approaches, devising innovative synthetic data generation techniques, optimizing federated learning algorithms, and delving into the individual sensing technologies and systemic aspects of HAR systems. In addition to these technical advancements, addressing the challenges of accuracy, reliability, scalability, and adaptability in Smart Living services and applications is of paramount importance for the development of effective, secure, and ethical HAR solutions. Prioritizing low-power consumption and lightweight processing in system design, researchers can contribute to the creation of more sustainable, accessible, and efficient Smart Living solutions that cater to a wide range of users and environments. This will, in turn, enhance the quality of life for those who reside in Smart Living spaces, promoting a more comfortable, safe, and convenient living experience.

The development of multi-resident HAR represents a crucial area for further exploration, as it has significant practical applications in assisted living facilities and smart homes. The ability to recognize and interpret the activities of multiple individuals simultaneously can contribute to a safer, more responsive, and personalized living environment. For instance, in an assisted living facility, multi-resident HAR systems can monitor the well-being of the elderly and provide timely assistance when required, ensuring their safety and independence. Similarly, in a smart home setting, these systems can facilitate energy conservation, enhance security, and enable seamless interaction between the residents and their environment.

Moreover, addressing the ethical implications of HAR systems is essential, as the widespread adoption of these technologies raises concerns regarding user privacy, data ownership, and potential misuse of sensitive information. Researchers should work towards establishing clear ethical guidelines and developing privacy-preserving techniques that protect user data while still enabling effective HAR solutions. In light of the rapid advancements in AI, ML, and sensor technologies, the potential of HAR systems in Smart Living services and applications is immense. However, realizing this potential requires a multidisciplinary approach, bringing together researchers from various fields such as computer science, engineering, psychology, and social sciences. This collaboration will help bridge the gap between technology and human-centered design, ensuring that HAR systems not only meet technical requirements but also address the diverse needs and preferences of the end-users.

Ultimately, by overcoming the challenges and leveraging the opportunities highlighted in this review, researchers and practitioners can develop innovative, robust, and user-friendly HAR systems that seamlessly integrate into Smart Living spaces, transforming the way we live and interact with our environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D. and G.R.; methodology, G.D.; investigation, G.D. and G.R.; data curation, G.D., G.R. and A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D. and G.R.; writing—review and editing, G.D., G.R., A.C. and A.M.; project administration, A.L.; funding acquisition, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out within the project PON "4FRAILTY" ARS01_00345 funded by the MUR-Italian Ministry for University and Research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable..

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAL |

Ambient Assisted Living |

| ADL |

Activity of Daily Living |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| BiGRU |

Bi-directional Gated Recurrent Unit |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| CPD |

Change Point Detection |

| CSI |

Channel State Information |

| DE |

Differential Evolution |

| DL |

Deep Learning |

| DT |

Decision Tree |

| GRU |

Gated Recurrent Unit |

| HAR |

Human Action Recognition |

| HMM |

Hidden Markov Model |

| IMU |

Inertial Measuring Unit |

| ICT |

Information and Communication Technology |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| KNN |

K-Nearest Neighbors |

| LR |

Logistic Regression |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| LSVM |

Linear Support Vector Machine |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| MLP |

Multilayer perceptron |

| PIR |

Passive Infrared |

| RCN |

Residual Convolutional Network |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| RGB |

Red-Green-Blue |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Network |

| SDE |

Sensor Distance Error |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| TCN |

Temporal Convolutional Network |

| UWB |

Ultra-Wideband |

References

- Shami, M.R.; Rad, V.B.; Moinifar, M. The structural model of indicators for evaluating the quality of urban smart living. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2022, 176, 121427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lam, K.; Zhu, K.; Zheng, C.; Li, X.; Du, Y.; Liu, C.; Pong, P.W. Overview of spintronic sensors with internet of things for smart living. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2019, 55, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasirandi, R.; Lander, A.; Sakinah, H.R.; Insan, I.M. IoT products adoption for smart living in Indonesia: technology challenges and prospects. 2020 8th international conference on information and communication technology (ICoICT). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–6.

- Giffinger, R.; Haindlmaier, G.; Kramar, H. The role of rankings in growing city competition. Urban research & practice 2010, 3, 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Caragliu, A.; Del Bo, C. Smartness and European urban performance: assessing the local impacts of smart urban attributes. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 2012, 25, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dameri, R.P.; Ricciardi, F. Leveraging smart city projects for benefitting citizens: The role of ICTs. Smart City Networks: Through the Internet of Things. 2017, pp. 111–128.

- Khan, M.S.A.; Miah, M.A.R.; Rahman, S.R.; Iqbal, M.M.; Iqbal, A.; Aravind, C.; Huat, C.K. Technical Analysis of Security Management in Terms of Crowd Energy and Smart Living. Journal of Electronic Science and Technology 2018, 16, 367–378. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M.J.N.; Kim, M.J. A critical review of the smart city in relation to citizen adoption towards sustainable smart living. Habitat International 2021, 108, 102312. [Google Scholar]

- Chourabi, H.; Nam, T.; Walker, S.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Mellouli, S.; Nahon, K.; Pardo, T.A.; Scholl, H.J. Understanding smart cities: An integrative framework. 2012 45th Hawaii international conference on system sciences. IEEE, 2012, pp. 2289–2297.

- Li, M.; Wu, Y. Intelligent control system of smart home for context awareness. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks 2022, 18, 15501329221082030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.D.; Shafran, R. Adaptation, personalization and capacity in mental health treatments: a balancing act? Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2023, 36, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ogata, H.; Hou, B.; Uosaki, N.; Yano, Y. Personalization and Context-awareness Supporting Ubiquitous Learning Log System. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Computers in Education (ICCE 2011), Chiang Mai, Thailand. National Electronics and Computer Technology Center, Thailand, 2011.

- Keshavarz, M.; Anwar, M. The automatic detection of sensitive data in smart homes. HCI for Cybersecurity, Privacy and Trust: First International Conference, HCI-CPT 2019, Held as Part of the 21st HCI International Conference, HCII 2019, Orlando, FL, USA, July 26–31, 2019, Proceedings 21. Springer, 2019, pp. 404–416.

- Rafiei, M.; Von Waldthausen, L.; van der Aalst, W.M. Supporting confidentiality in process mining using abstraction and encryption. Data-Driven Process Discovery and Analysis: 8th IFIP WG 2.6 International Symposium, SIMPDA 2018, Seville, Spain, December 13–14, 2018, and 9th International Symposium, SIMPDA 2019, Bled, Slovenia, September 8, 2019, Revised Selected Papers 8. Springer, 2020, pp. 101–123.

- Bianchini, D.; De Antonellis, V.; Melchiori, M.; Bellagente, P.; Rinaldi, S. Data management challenges for smart living. Cloud Infrastructures, Services, and IoT Systems for Smart Cities: Second EAI International Conference, IISSC 2017 and CN4IoT 2017, Brindisi, Italy, April 20–21, 2017, Proceedings 2. Springer, 2018, pp. 131–137.

- Diraco, G.; Rescio, G.; Siciliano, P.; Leone, A. Review on Human Action Recognition in Smart Living: Sensing Technology, Multimodality, Real-Time Processing, Interoperability, and Resource-Constrained Processing. Sensors 2023, 23, 5281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, V.; Katragadda, R.; Ghanekar, S.; Raj, S.; Kollipara, P.; Anitha Rani, I.; Vadivel, A. Smart surveillance and real-time human action recognition using OpenPose. ICDSMLA 2019: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Data Science, Machine Learning and Applications. Springer, 2020, pp. 504–509.

- Sicre, R.; Nicolas, H. Human behaviour analysis and event recognition at a point of sale. 2010 Fourth Pacific-Rim Symposium on Image and Video Technology. IEEE, 2010, pp. 127–132.

- Zin, T.T.; Htet, Y.; Akagi, Y.; Tamura, H.; Kondo, K.; Araki, S.; Chosa, E. Real-time action recognition system for elderly people using stereo depth camera. Sensors 2021, 21, 5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, C.M.; Singh Kushwaha, A.K.; Nigam, S.; Khare, A. Automatic human activity recognition in video using background modeling and spatio-temporal template matching based technique. Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Computing and Artificial Intelligence, 2011, pp. 97–101.

- Vishwakarma, S.; Agrawal, A. A survey on activity recognition and behavior understanding in video surveillance. The Visual Computer 2013, 29, 983–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ke, Q.; Rahmani, H.; Bennamoun, M.; Wang, G.; Liu, J. Human action recognition from various data modalities: A review. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshad, M.H.; Bilal, M.; Gani, A. Human Activity Recognition: Review, Taxonomy and Open Challenges. Sensors 2022, 22, 6463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, G.; Bajwa, U.I.; Raza, R.H. Toward human activity recognition: a survey. Neural Computing and Applications 2023, 35, 4145–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R.; Nishio, M.; Do, R.K.G.; Togashi, K. Convolutional neural networks: an overview and application in radiology. Insights into imaging 2018, 9, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Manzo-Martínez, A.; Gaxiola, F.; Gonzalez-Gurrola, L.; Ramírez-Alonso, G. Analysis of CNN Architectures for Human Action Recognition in Video. Computación y Sistemas 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yovanof, G.S.; Hazapis, G.N. An architectural framework and enabling wireless technologies for digital cities & intelligent urban environments. Wireless personal communications 2009, 49, 445–463. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Chen, H.; Brown, R.A. Hidden Markov model-based fall detection with motion sensor orientation calibration: A case for real-life home monitoring. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics 2017, 22, 1847–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi-Karvigh, S.; Ghahramani, A.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Soibelman, L. Real-time activity recognition for energy efficiency in buildings. Applied energy 2018, 211, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobakht, M.; Sivaraman, V.; Boreli, R. A host-based intrusion detection and mitigation framework for smart home IoT using OpenFlow. 2016 11th International conference on availability, reliability and security (ARES). IEEE, 2016, pp. 147–156.

- Cao, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Jin, Q.; Vasilakos, A.V. GCHAR: An efficient Group-based Context—Aware human activity recognition on smartphone. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 2018, 118, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.; Aryal, A.; Awada, M.; Bergés, M.; Billington, S.L.; Boric-Lubecke, O.; Ghahramani, A.; Heydarian, A.; Jazizadeh, F.; others. Ten questions concerning human-building interaction research for improving the quality of life. Building and Environment 2022, 226, 109681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klossner, S. ; others. AI powered m-health apps empowering smart city citizens to live a healthier life–The role of trust and privacy concerns 2022.

- Gordon, A.; others. Internet of things-based real-time production logistics, big data-driven decision-making processes, and industrial artificial intelligence in sustainable cyber-physical manufacturing systems. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics 2021, 9, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, G.; Bajwa, U.I.; Raza, R.H. Toward human activity recognition: a survey. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, pp. 1–38.

- Ma, N.; Wu, Z.; Cheung, Y.m.; Guo, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, B. A Survey of Human Action Recognition and Posture Prediction. Tsinghua Science and Technology 2022, 27, 973–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K.; Kundu, S.; Adhikary, T.; Sarkar, R.; Bhattacharjee, D. Progress of human action recognition research in the last ten years: a comprehensive survey. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering.

- Kong, Y.; Fu, Y. Human action recognition and prediction: A survey. International Journal of Computer Vision 2022, 130, 1366–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Chung, M.H.; Chignell, M.; Valaee, S.; Zhou, B.; Liu, X. A survey on deep learning for human activity recognition. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulsoom, F.; Narejo, S.; Mehmood, Z.; Chaudhry, H.N.; Butt, A.; Bashir, A.K. A review of machine learning-based human activity recognition for diverse applications. Neural Computing and Applications.

- Gupta, N.; Gupta, S.K.; Pathak, R.K.; Jain, V.; Rashidi, P.; Suri, J.S. Human activity recognition in artificial intelligence framework: A narrative review. Artificial intelligence review 2022, 55, 4755–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, S.; Liu, M.; Zhou, B.; Lukowicz, P. The state-of-the-art sensing techniques in human activity recognition: A survey. Sensors 2022, 22, 4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige, A.O.; Noor, M.H.M. A survey on unsupervised learning for wearable sensor-based activity recognition. Applied Soft Computing. 2022, p. 109363.

- Najeh, H.; Lohr, C.; Leduc, B. Towards supervised real-time human activity recognition on embedded equipment. 2022 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Living Environment (MetroLivEn). IEEE, 2022, pp. 54–59.

- Roggen, D.; Calatroni, A.; Rossi, M.; Holleczek, T.; Förster, K.; Tröster, G.; Lukowicz, P.; Bannach, D.; Pirkl, G.; Ferscha, A. ; others. Collecting complex activity datasets in highly rich networked sensor environments. 2010 Seventh international conference on networked sensing systems (INSS). IEEE, 2010, pp. 233–240.

- Reiss, A.; Stricker, D. Introducing a new benchmarked dataset for activity monitoring. 2012 16th international symposium on wearable computers. IEEE, 2012, pp. 108–109.

- Cook, D.J. Learning setting-generalized activity models for smart spaces. IEEE intelligent systems 2012, 27, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.J.; Crandall, A.S.; Thomas, B.L.; Krishnan, N.C. CASAS: A smart home in a box. Computer 2012, 46, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.J.; Schmitter-Edgecombe, M. Assessing the quality of activities in a smart environment. Methods of information in medicine 2009, 48, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singla, G.; Cook, D.J.; Schmitter-Edgecombe, M. Recognizing independent and joint activities among multiple residents in smart environments. Journal of ambient intelligence and humanized computing 2010, 1, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.J.; Crandall, A.; Singla, G.; Thomas, B. Detection of social interaction in smart spaces. Cybernetics and Systems: An International Journal 2010, 41, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]