1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), representing the most frequent form of primary liver cancer, is a significant global health concern. HCC is an insidious disease and ranks as one of the leading causes of death in patients diagnosed with various neoplastic conditions worldwide. Notably, specific risk factors such as cirrhosis, chronic viral hepatic infections including hepatitis B and hepatitis C, as well as chronic alcoholism, have been identified as being recurrently associated with this malignancy, increasing susceptibility and potentially affecting the disease course. [

1,

2]

Presently, the choice of treatment for HCC is primarily dictated by the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Staging classification (BCLC), which stratifies the disease into stages 0 (very early) to D (end stage). Specifically for stages 0 (very early) and A (early), potentially curative treatment options include orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT), liver resection (LR), and locoregional destruction therapies such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and microwave ablation (MWA). [

3]

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has emerged as a popular choice among minimally invasive image-guided ablation techniques. Its versatility allows for its administration through percutaneous, laparoscopic, or open surgery routes. RFA's adoption is largely driven by its comparable efficacy to liver resection, with multiple studies illustrating similar results between the two treatment modalities. [

4,

5,

6]

The key factor that determines the success of thermal ablation treatment is ensuring complete coverage of the targeted tumor by the ablation volume, along with an adequate ablation margin. Multiple studies have confirmed that the ablation margin is an independent predictor of ablation site recurrence (ASR). Currently, the recommended minimum ablation margin is 5 mm, although a 10 mm margin is preferred. Currently, the evaluation of the ablation margin is primarily done visually, either by comparing pre- and post-ablation images side by side or using image fusion. The margin is reported in a 2D format at the location where the tumor diameter is largest. However, this evaluation method has certain drawbacks. It is limited to a single 2D image, which can be subjective and prone to variability between different readers, even if they are experienced radiologists.

A promising new approach in evaluating the response to RFA or other thermal ablation techniques might be the volumetric assessment of the necrotic area using semi automatic or automatic software [

7,

8]. Since not only the imaging characteristics are important in assessing the results of the ablation (such as lack of arterial hyperenhancement), the volumetric assessment of the necrotic area might prove to be an important biomarker in the assessment of the local reccurence and longer time frame disease progression.

In the present study we propose a simple, reproductible and accessible method using widely available tools and methods to calculate the postablation necrosis volume and to also show that it might be an important biomarker in the followup of patients after radiofrequency ablation in HCC.

2. Materials and Methods

Our study was a retrospective, descriptive and analytical one conducted between 01.01.2018 - 30.09.2021 in the Radiology and Medical Imaging Department of Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest Romania.

During this time 88 patients known with chronic hepatopathy (cirrhosis, chronic viral hepatic infections and chronic alcoholism) that were diagnosed with LI-RADS 4/5 lesions underwent at least one RFA procedure.

Inclusion criteria:

a. patients diagnosed with a single HCC lesion treated with one RFA (lesions smaller or equal to 3 cm, BCLC 0 or A) during 01.01.2018-30.09.2021;

b. adequate imaging evaluations at pre-RFA (at most 30 days prior), and post-RFA (1,3,6 and 12 months, and more than 12 months).

Exclusion criteria:

a. liver transplant after the procedure;

b. liver resections of the ablated area;

c. other loco-regional treatments pre-/post-RFA procedures;

d. more than 1 RFA procedure;

e. incomplete ablation;

f. no proper follow-up.

Definitions

-incomplete ablation - one month after RFA if the treated lession is LI-RADS viable (nodular, mass-like or thick irregular tissue in/along the treated lession with APHE, “wash-out”, enhancement similar to pretreatment); [

5]

-local tumor progression (LTP) - recurrent tumor that occurs inside or adjacent to the primary tumor volume following a complete ablation (at less than 1 cm from the ablated area), at more than six months after RFA;

-intrahepatic distant recurrence (IDR) rate - new HCC lesion that appears independently and distant to the completely ablated lesion.[

11]

The RF generator used was the AngioDynamics RITA® Model 1500X and US/CT-guided percutaneous puncture was performed with an expandable tine with interstitial saline infusion (RITA StarBurst Talon Semi-Flex -D= 4 cm;L= 25 cm). We used both ultrasound and/or CT guided-RFA in all patients. All the patients were performed with the auto settings of the machine. In larger lesions (2,5-3cm) a second ablation was performed in the same session if the initial result was considered insufficient (probable incomplete ablation- defined by contrast enhanced CT immediately after the ablation)

Three-dimensional volumetry was performed using the volumetry tool of OsiriX MD’s dedicated software. OsiriX

® is an accurate method to measure hepatic volumes and has been used in other studies, and is considered the gold standard when it comes to total liver volumes and future remnant liver volumes for liver resections. [

12]

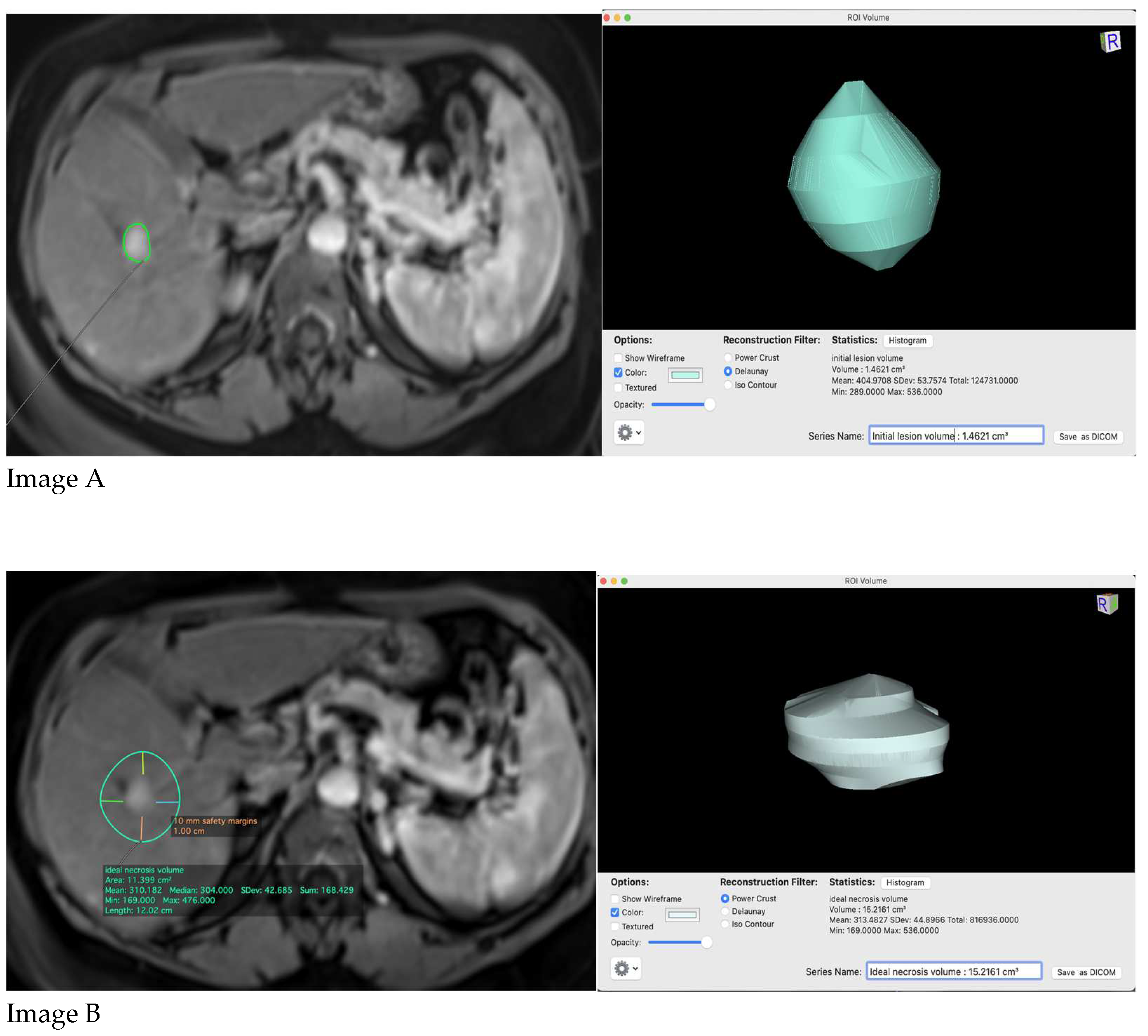

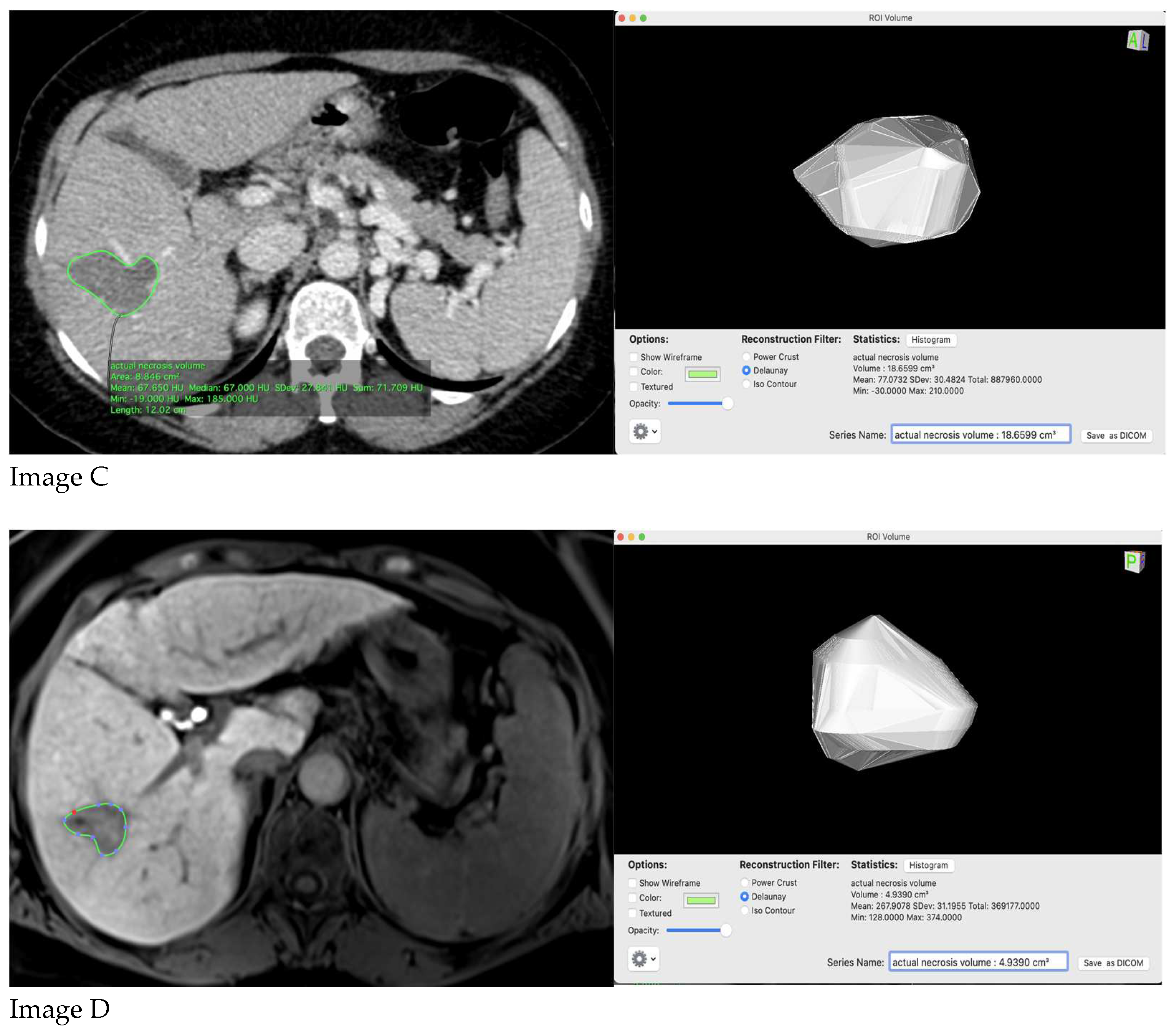

Initial lesion volume, ideal necrosis volume and actual necrosis volume at 1 month and 6 months post-procedure were performed. To obtain the ideal necrosis volume, ideally 1 cm safety margins were used. If the lesion treated was peripheral or in the proximity of a great intrahepatic vessel we used 0,5 cm safety margins.

To calculate the volumes we used: arterial phase on CE-CT/-MRI for the initial lesion volume and the ideal necrosis volume, portal/hepatic phase on CE-CT, and portal /hepato-biliary phase on CE-MRI (depending on the contrast agent used) for actual necrosis volume at 1 month and 6 months post-procedure (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

All the volumes were calculated manually in Osirix and we have defined the initial volume of the lesion by using the polygon tool; the subsequent measures at the other time points (1 month and 6 months) were performed by the same radiologist using the same technique. The ideal ablation area was defined as stated above and a new region of interest was defined in the initial study. The time to perform the computed tomography was also noted during the studies.

The statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc 20.211. Student t-test and ROC curve were used to compare the difference between the two groups, and for estimation of recurrence-free survival curve the Kaplan–Meier method was performed.

3. Results

Eventually 35 patients were eligible to be included in the study. Most of the patients (37) excluded from the study did not meet the proper pre-/post-procedural follow-up criteria (many of them during the 2020-2021 COVID pandemic) for the volumetric assessments to be correctly performed.

Worth mentioning is that out of the patients which were not eligible to be included, 2 had incomplete ablation detected at 1 month post-RFA, 12 patients had at least one TACE procedure prior or in the following months after RFA, and 2 patients benefited from liver transplant in the following 6 months post-RFA (in their case RFA was conducted as a form of bridging therapy).

Patients include in the study had a median age of 67 years (table 1) and were predominantly male – 62.85% (table 1), most of them having very early HCC lessions, BCLC 0 -57.1 % (table 2) with the most common aetiology of chronic liver disease being hepatitis C viral infection – 42,85% (table 3).

The time necessary for completion of the volume calculation was also recording, showing less than 1 minute for a time point or per study. The evaluation time of the actual necrosis volume in the patients studied was less than 5 minutes, when applying the methodology to all the patients studies.

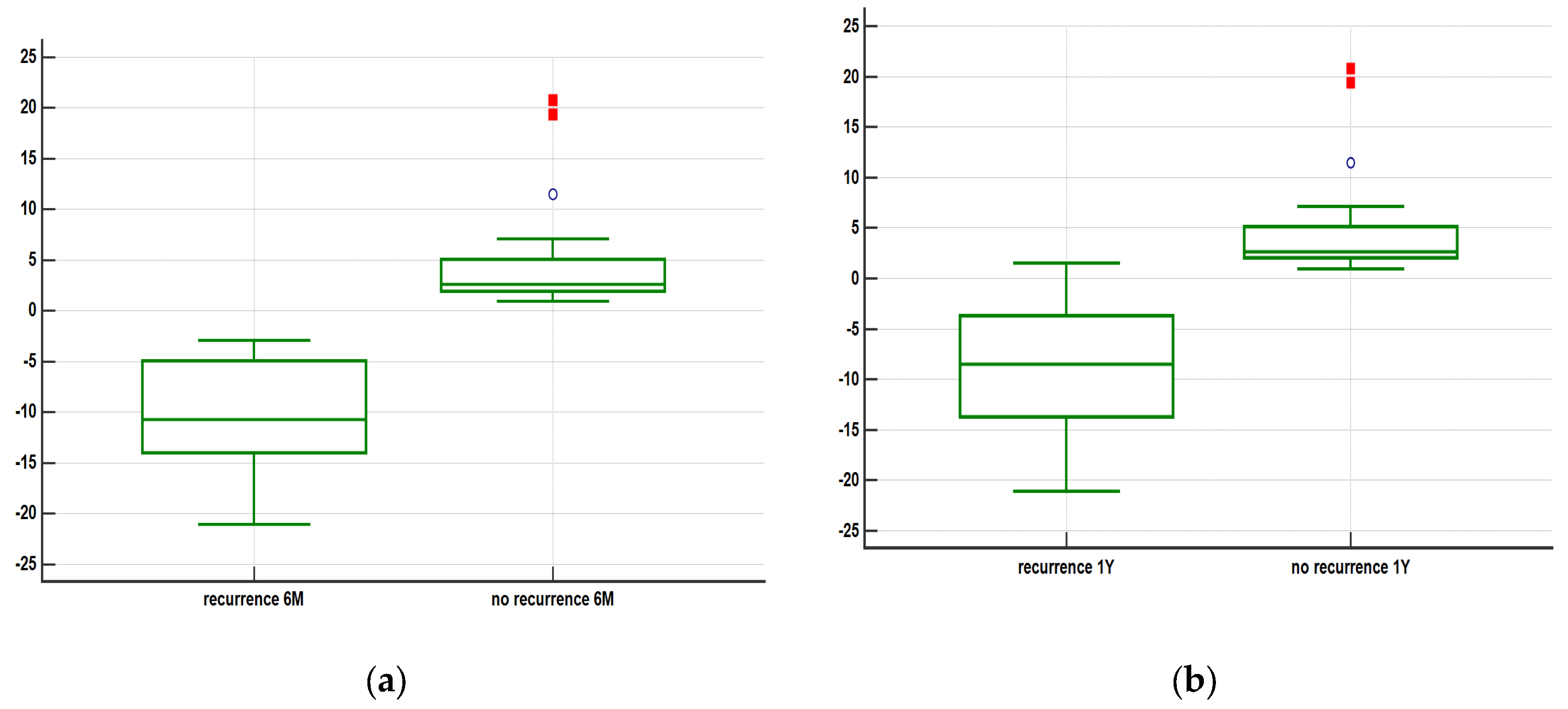

All patients that showed tumor recurrence at 6 months had the actual necrosis volume at 1 month larger than the ideal estimated necrosis volume at 1 month. The overall actual necrosis volume/ideal necrosis volume ratio equals to 1.450 +/- 0.6242 (mean + SD).

7 (20%) patients showed tumor recurrence at 6 months post-RFA, and 1 patient showed tumor recurrence at 9 months post-RFA, respectively 27 (77%) showed no tumor recurrence at 1 year post-RFA.

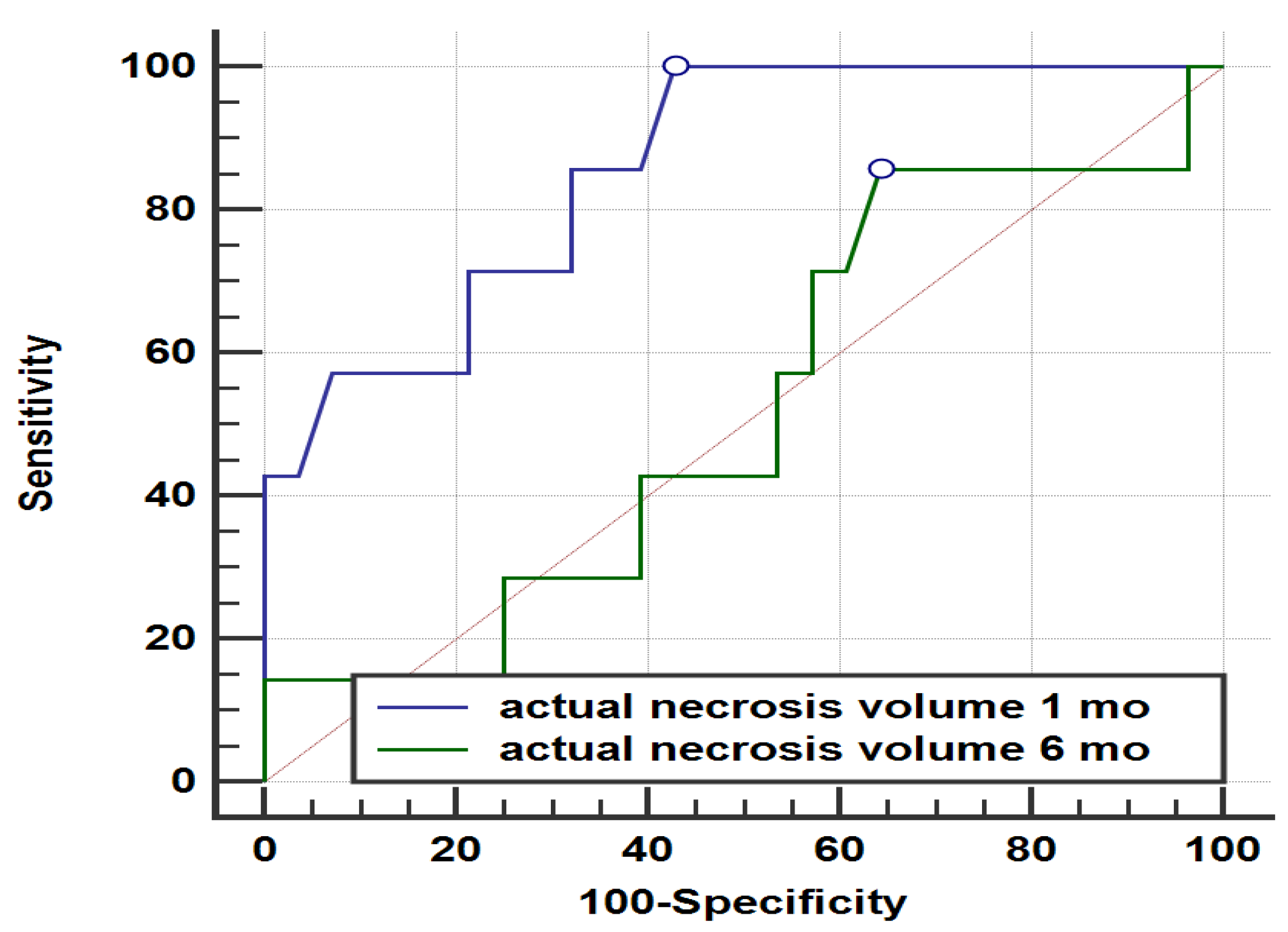

Figure 3.

Comparison of ROC curves for actual necrosis volume 1 month vs actual necrosis volume at 6 months and tumor recurrence at 1 year (p < 0,05).

Figure 3.

Comparison of ROC curves for actual necrosis volume 1 month vs actual necrosis volume at 6 months and tumor recurrence at 1 year (p < 0,05).

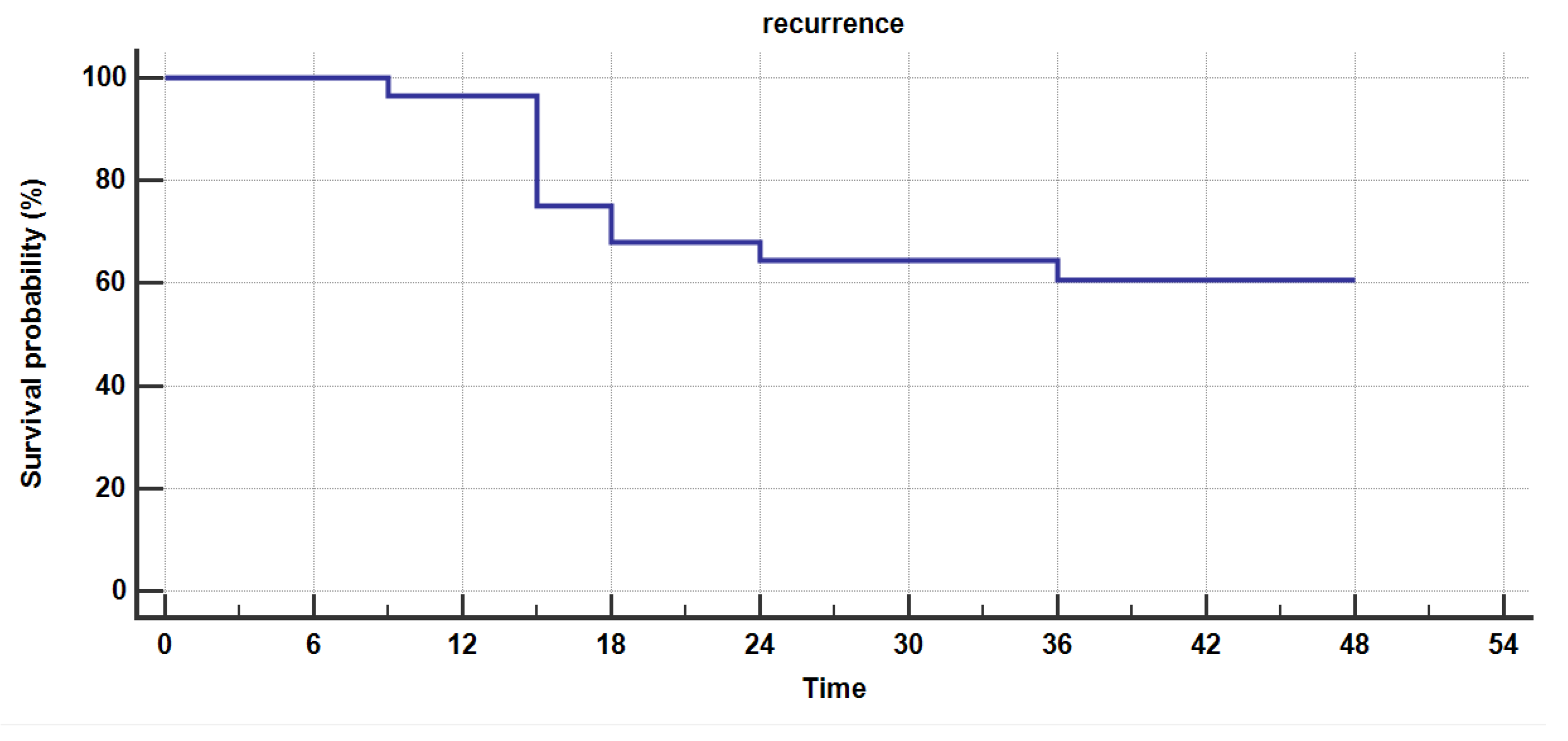

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for estimating recurrence free survival in patients with actual necrosis volume larger than the ideal estimated necrosis volume at 1 month.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for estimating recurrence free survival in patients with actual necrosis volume larger than the ideal estimated necrosis volume at 1 month.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients based on demographics.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients based on demographics.

| Demographics |

Age (y) 1

|

Sex (%) |

| |

67.09 +/- 8.17 |

M- 22 (62.85) |

| |

|

F- 13 (37.15) |

|

1 mean + SD |

|

|

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients based on BCLC.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients based on BCLC.

| |

BCLC 0 |

BCLC A |

LTP

Ideal Vol > Actual Vol |

2 |

5 |

LTP

Ideal Vol < Actual Vol |

7 |

4 |

| Without LTP |

11 |

6 |

| TOTAL |

20 |

15 |

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of patients based on aetiology of chronic liver disease.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of patients based on aetiology of chronic liver disease.

| |

HBV |

HBV/HDV |

HCV |

Toxic |

LTP

Ideal Vol > Actual Vol |

1 |

0 |

4 |

2 |

LTP

Ideal Vol < Actual Vol |

2 |

2 |

5 |

2 |

| Without LTP |

5 |

2 |

6 |

4 |

| TOTAL |

8 |

4 |

15 |

8 |

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of patients based on of calculated volumes.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of patients based on of calculated volumes.

| |

Initial lesion

Vol |

Ideal necrosis

Vol at 1 mo |

Actual necrosis

Vol at 1 mo |

Actual necrosis Vol at 6 mo |

Calculated Volumes 1

(cm 3)

|

4.191 +/- 2.685 |

19.18 +/- 7.952 |

21.04 +/- 9.881 |

7.614 +/- 3.749 |

|

1 mean + SD |

|

|

|

|

Table 5.

Survival analysis for estimating recurrence free survival in patients with actual necrosis volume larger than the ideal estimated necrosis volume at 1 month.

Table 5.

Survival analysis for estimating recurrence free survival in patients with actual necrosis volume larger than the ideal estimated necrosis volume at 1 month.

| Survival time (mo) |

Survival proportion |

Standard Error |

| 9 |

0.964 |

0.0351 |

| 15 |

0.750 |

0.0818 |

| 18 |

0.679 |

0.0883 |

| 24 |

0.643 |

0.0906 |

| 36 |

0.607 |

0.0923 |

| 48 |

- |

- |

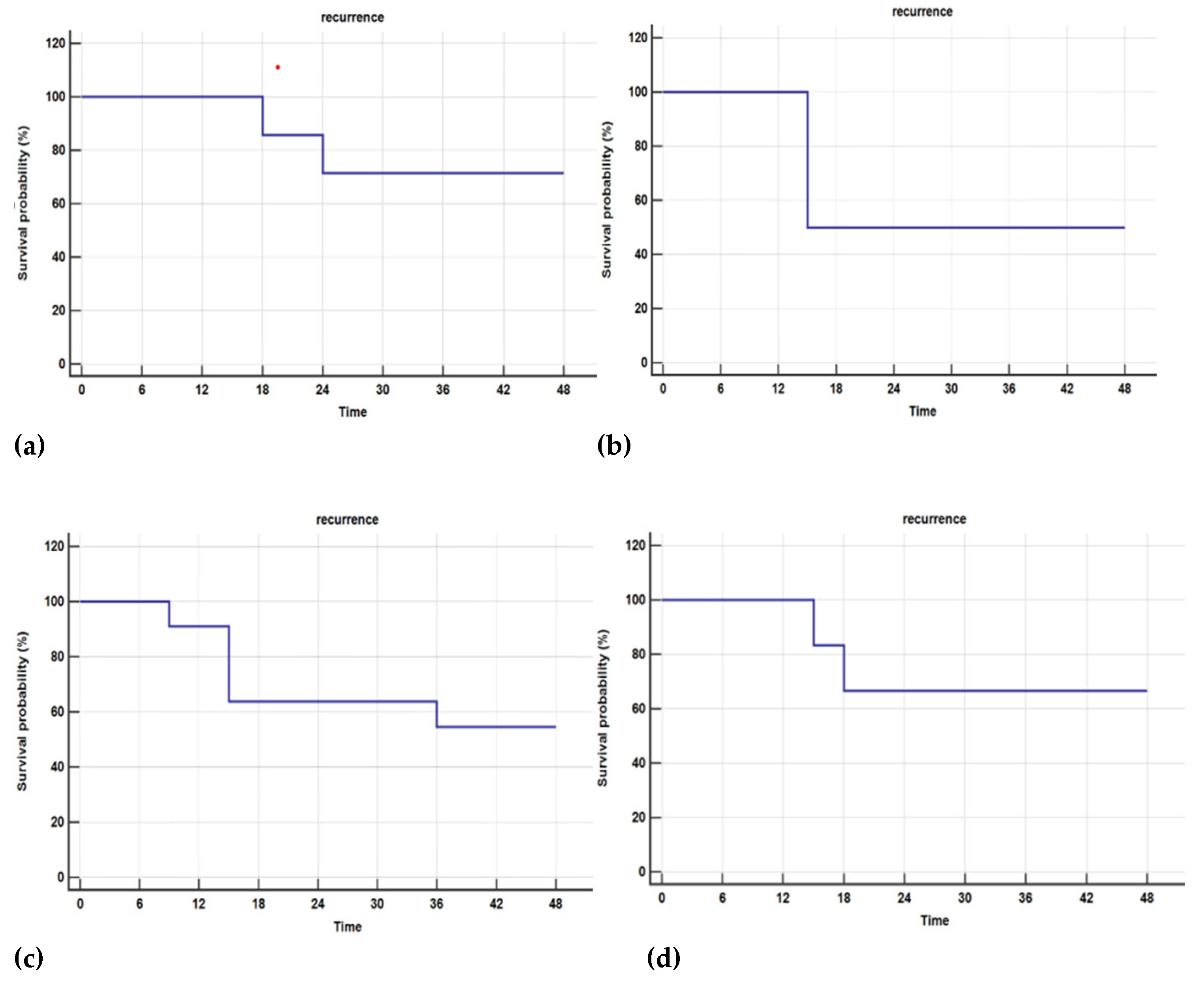

The group of patients with no LTP at 6 months, in which actual necrosis volume at 1 month larger than the ideal estimated volume, had the following aetiologies: 7 patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, 4 with hepatitis B virus - hepatitis delta virus co-infection (HBV-HDV), 11 with hepatitis C infections (HCV) and 6 had toxic-nutritional induced chronic hepatopathy due to chronic alcohol consumption.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for estimating recurrence in patients that showed no early LTP (at 6 months, with actual necrosis volume larger than ideal necrosis volume at 1 month), by aetiology: (a) HBV; (b) HBV/HBD; (c) HCV; (d) Toxic.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for estimating recurrence in patients that showed no early LTP (at 6 months, with actual necrosis volume larger than ideal necrosis volume at 1 month), by aetiology: (a) HBV; (b) HBV/HBD; (c) HCV; (d) Toxic.

Table 6.

Recurrence occurrence in patients, with actual necrosis volume larger than the ideal estimated necrosis volume at 1 month, with LTP at more than 6 months.

Table 6.

Recurrence occurrence in patients, with actual necrosis volume larger than the ideal estimated necrosis volume at 1 month, with LTP at more than 6 months.

| Aetiology |

Recurrence (%) |

No recurrence (%) |

| HBV |

28.57 |

71.43 |

| HBV/HDV |

50 |

50 |

| HCV |

45.45 |

54.55 |

| Toxic |

33.33 |

66.67 |

| Overall |

39.29 |

60.71 |

11 patients (39%) with no early LTP at 6 months (actual necrosis at 1 month larger than ideal necrosis volume) showed recurrence during the 36 months follow-ups, most of them, 5 (45%) had chronic HCV infection.

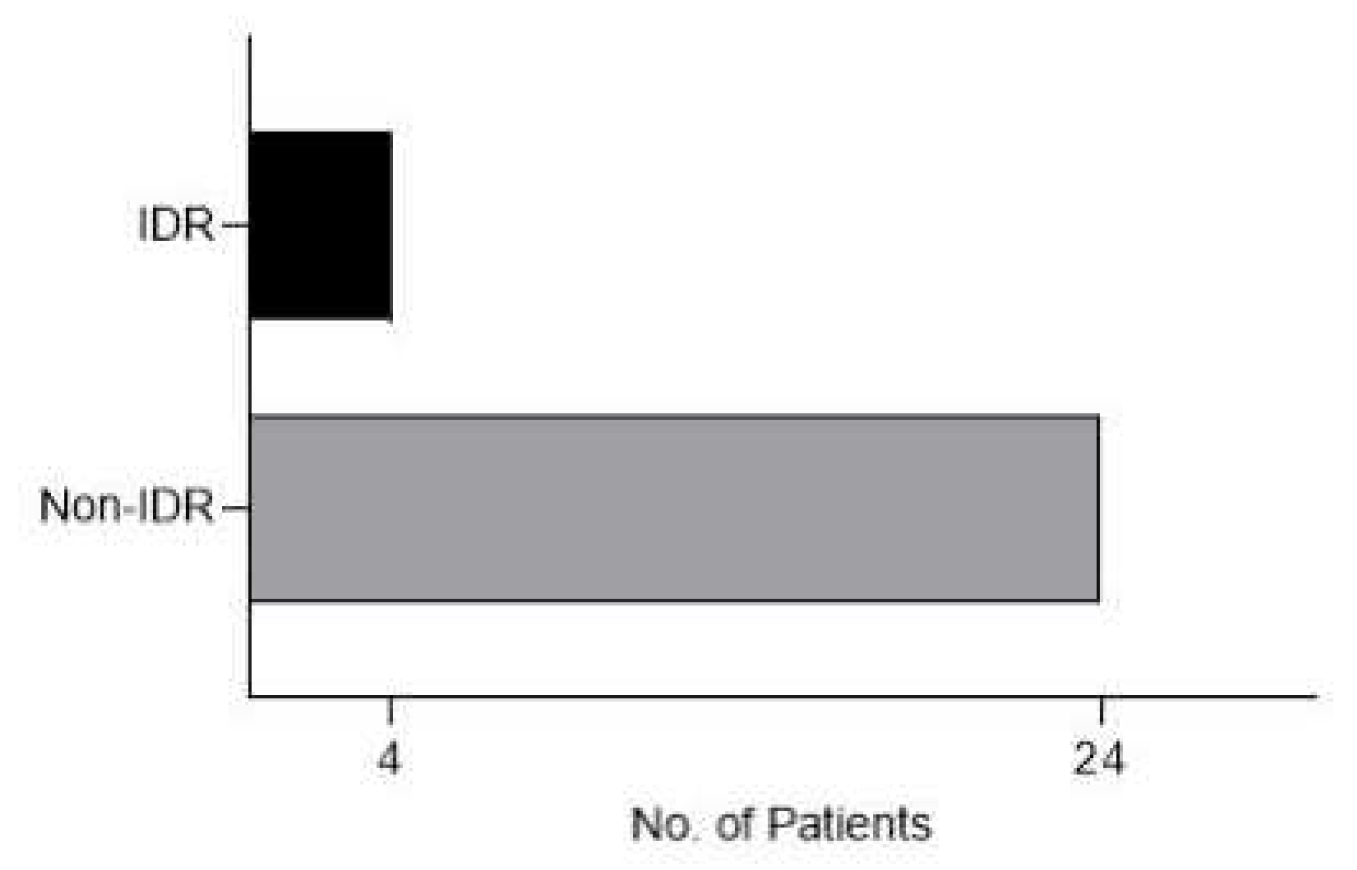

Figure 4.

Graph showing patients with no early LTP with IDR at follow-ups (at (at 6 months, with actual necrosis volume larger than ideal necrosis volume at 1 month).

Figure 4.

Graph showing patients with no early LTP with IDR at follow-ups (at (at 6 months, with actual necrosis volume larger than ideal necrosis volume at 1 month).

4 patients had IDR (14%), 1 was diagnosed at 18 months follow-up and the other 3 were diagnosed at 24 months follow-up. 3 patients had chronic HBV infection and 1 one chronic HCV infection.

4. Discussion

The complete coverage of liver tumors by the ablation volume is the most crucial factor in achieving successful treatment outcomes with thermal ablation (9). However, the terminology, timing, and metrics used to assess the completeness of ablation vary across the existing literature (10). Nevertheless, there is a general consensus regarding the importance of an additional minimal ablation margin that encompasses the targeted tumor. This concept of a minimal treatment margin originates from surgical resection, where the safety margin around the tumor is precisely determined through histopathological examination of the pathological specimen. This enables more detailed analysis of different subgroups based on the margins of resection in relation to tumor recurrence. In contrast, for image-guided thermal ablation procedures, the assessment of treatment completeness primarily relies on visual interpretation of follow-up imaging. Although a correlation between radiological findings and histopathological results in surgically removed livers has been observed following radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma (13), the visual assessment without the availability of histopathology remains subjective and susceptible to interpersonal variations (14).

Actually, the margins of the ablation area have been known to be one of the most important predicting factors in local reccurence after ablation (XVII, XVIII) either in HCC or liver metastases. In a retrospective study, conducted between March 2000 and December 2014, aimed to develop an algorithmic strategy to predict local tumor progression-free survival (LTPFS) following radiofrequency ablation of colorectal liver metastasis (CLM). The main purpose of this algorithm was to assist in selecting patients who would benefit most from RFA for CLM. The authors concluded that radiofrequency ablation provided long-term control of colorectal liver metastases. While the minimal ablative margin of 5 mm or less was the most dominant factor, a multifactorial approach that includes tumor size and subcapsular location better predicted local tumor progression-free survival (15)

The question would be if the visual inspection alone of the images might be enough to determine the postablation result. To answer this question, a study published in 2020 (16) aimed to assess the challenges in evaluating the success of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) treatment for liver tumors immediately after the intervention, relying only on visual inspection, and to analyze whether a radiologist's expertise impacts this assessment. The study utilized peri-interventional CT scans of nine patients who had undergone RFA for hepatocellular carcinomas. These scans were evaluated by 38 interventional oncologists from 14 countries who were tasked with determining whether complete ablation was achieved by visually inspecting the pre- and post-intervention scans. Findings revealed that 44.1% of cases per radiologist were inaccurately judged, with 37% overestimated (overcalls) and 46.3% underestimated (undercalls). Expertise in percutaneous tumor ablation (more than 50 interventions performed) did not significantly influence the results.The study concluded that the conventional side-by-side visual evaluation of treatment success after RFA is challenging even for experienced radiologists. Advanced processing techniques such as rigid/non-rigid image fusion with periablational margin assessment may be required to reduce errors and objectively evaluate the technical success and predictive efficacy of liver RFA treatments.

In our study we used semi-automated computed volumetry, but using artificial intelligence computed volumetry could show better safety margins and that could lead to better prediction of LTP and recurrence free survival.[

7] We think that with the delevopment of automated software, the necrosis volume may be a very important biomarker in the evaluation of the reccurence of HCC after ablation procedures.

In our research, we have noted that the actual time necessary for the calculation of the necrosis volumes was actually short (less than 5 minutes), so even if dedicated software may yield better results, the additional cost implied by these methods might be higher than using semiautomated computer volumetry. Our methodology may be easily reproduced in non research facilities and might be used on a day to day basis in different centers (from high volume centers of liver surgery and transplantation to primary care centers). Therefore, volumetric assessment of the necrotic area might be a useful and readily available biomarker in the followup of these patients.

Several authors have investigated and shown that different software applications might be beneficial in estimating the effectiveness of the ablation. Sandu et al (7) propose a computational method for assessing the effectiveness of thermal ablation of liver tumors, focusing on the completeness of ablation volume (XVIII). This technique, called Quantitative Ablation Margins (QAM), includes a new algorithm for dealing with tumors beneath the liver capsule (subcapsular tumors). The QAM computational code is shared publicly to promote its standardized usage and definition when assessing the coverage of ablation margins. According to the study, the success of thermal ablation hinges on full tumor coverage by the ablation volume, although there are variations in how completeness is evaluated. In contrast to surgical resection, where the surgical safety margin can be accurately quantified, the completeness of image-guided thermal ablation is mainly determined by visual inspection of follow-up imaging, which can be subjective and vary between observers. However, the current application of this method requires an experienced radiologist and a technically-oriented individual to handle data pre-processing and computations. This may limit its use outside specialized centers or clinical trials. Its widespread clinical use would require integration into software workflows. By using QAM for an accurate and consistent assessment of ablation completeness, the authors propose several benefits, including: distinguishing between incomplete ablation and true ablative scar recurrence (ASR); in-depth analyses of correlation between ablation margins and ASR; and, serving as an objective endpoint to study factors associated with the expansion of ablation volumes.

Xia et al published a comprehensive review of the current state of research on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for the treatment of liver tumors [

17]. The authors conducted a systematic search of the literature and identified 18 studies that met their inclusion criteria. These studies explored the use of AI in various aspects of RFA, including tumor detection, segmentation, and ablation planning. Overall, the authors found that AI has the potential to improve the accuracy and efficiency of RFA for liver tumors. For example, AI algorithms can help to automatically identify and segment liver tumors in medical images, reducing the need for manual input and increasing the speed of the process. AI can also help to predict the efficacy of RFA, which can help clinicians to better plan and optimize treatment. However, the authors note that more research is needed to fully explore the potential benefits of AI in RFA for liver tumors. They call for larger, multicenter studies with standardized protocols to further evaluate the use of AI in this context.

Our study showed that if actual necrosis volume at 1 month is larger than ideal necrosis volume there will be no LTP at 6 months (p<0.05 T-test) and that having a larger 1 month actual necrosis volume is very good predictor for LTP at 12 months post-RFA (p<0.05 T-test).

The overall recurrence-free survival rate was similar to data in other studies, in the first year after RFA it was 77% in the first 12 months, 68% at 18 months, 64% at 24 months and 60,7% at 36 months, with results similar to other studies [

18,

19], including one evaluating volumetric necrosis for predicting LTP and IDR conducted by by Inmutto N, et al. This group of authors conducted a retrospective analysis of 50 patients who underwent RFA for HCC between 2015 and 2019. They measured the ablation volume of RFA and evaluated its relationship with intrahepatic recurrence-free survival (IRFS). They also analyzed other factors that could affect IRFS, such as patient age, tumor size, and presence of cirrhosis. The results showed that a larger ablation volume of RFA was associated with a longer IRFS. Specifically, patients with an ablation volume of 100 cubic millimeters or more had a significantly longer IRFS than those with a smaller ablation volume. The authors suggest that this could be due to the fact that a larger ablation volume may result in a more complete ablation of the tumor, reducing the likelihood of residual tumor cells and subsequent recurrence. The authors also found that tumor size and the presence of cirrhosis were significant predictors of IRFS, with larger tumors and the presence of cirrhosis associated with a shorter IRFS.

Solbiati et al retrospectively evaluated a novel software platform's accuracy in assessing the completeness of percutaneous thermal ablations (20). This assessment involved ninety hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) in 50 patients who had undergone percutaneous ultrasound-guided microwave ablation (MWA). These cases showed apparent technical success at 24-hour post-ablation CT scans and had at least a one-year imaging follow-up. Using the new volumetric registration software, the HCCs were segmented, co-registered, and overlapped on pre-ablation CT volumes (with and without a 5mm safety margin) and corresponding post-ablation necrosis volumes. These results were compared to the visual side-by-side inspection of axial images. The 1-year follow-up CT scans showed no local tumor progression (LTP) in 76.7% (69/90) of cases, while LTP was found in 23.3% (21/90) cases. For HCCs classified as "incomplete tumor treatments" by the software, LTP developed in 76.5% (13/17) of cases. Moreover, all these LTPs occurred exactly where residual non-ablated tumor was identified by the retrospective software analysis. HCCs classified as "complete ablation with <100% 5 mm ablative margins" had LTP in 16.3% (8/49) cases, while none of the HCCs with "complete ablation including 100% 5 mm ablative margins" had LTP.

The differences in LTP between both partially ablated HCCs vs completely ablated HCCs, and ablated HCCs with <100% vs with 100% 5 mm margins were statistically significant. Thus, the study concluded that the novel software platform for volumetric assessment of ablation completeness could increase the detection of incompletely ablated tumors, potentially preventing subsequent recurrences.

Recurrence-free survival could also be influenced by aetiology, independently to the volume of necrosis. This was observed in patients with a larger actual necrosis volume, but with LTP at more than 6 months post-RFA. The most frequent recurrence rate was observed in patients with chronic HCV infection, which could be explained by its increased ability to promote carcinogenesis.[

21]

In our study, due to the small number of IDR cases statistical tests were not significant. Some studies classify this as tumor recurrence after locoregional curative treatment and correlate it with large ablation areas [

18], others have associated it to be more prevalent in patients with chronic HBV infection [

11].

Due to fibrotic changes of the ablated area the actual volume of necrosis decreases in size at each follow-up [

10] and our study showed that actual volume of necrosis at 1 month is a better predictor of recurrence. Some published data seem to propose a different time point to achieve better prediction of reccurence. Li M et al explore the feasibility of using artificial intelligence computed volumetry to predict intrahepatic recurrence (IHR) of hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation. The authors utilized AI segmentation software to measure the ablation zone and surrounding tissue on magnetic resonance imaging scans obtained one day and one month post-RFA. They found that the actual ablation zone volume measured one day after RFA was a better predictor of IHR than the one-month measurement. [

22]

We excluded from our analysis patients that had prior treatment for HCC, such as TACE or surgery, due to the fact that the postprocedural hepatic morphological changes could be difficult to interpret when assessing the correct tumoral volume.

The actual necrosis volume is also influenced by several factors: lesion position, proximity to great vessels or other critical structures and generator parameters.[

23]

Although MWA is an effective and safe alternative to LR [

24], its superiority to RFA has not yet been proven [

15], perhaps a study comparing necrosis volumetric assessment in both procedures could help decide which one could show lower LTP.Study limitations

Retrospective, monocentric study based on a small group of patients, limited to the evaluation of patients with a single BCLC 0 or A liver lesion treated with radiofrequency ablation and inconsistent imaging follow-up. A prospective trial with longer time interval for follow-up is needed to determine recurrence free-survival and LTP. Also our study included some potential biases introduced by excluding patients with prior HCC treatments that may need some further assessments as regarding the risk of recurrence in previously treated nodules. Further research in this area, including a comparison of necrosis volumetric assessment in RFA and microwave ablation (MWA) procedures, as suggested in the text, could also be valuable. Finally, it would be interesting to explore the potential of artificial intelligence computed volumetry in the evaluation of recurrence of HCC after ablation procedures. Nevertheless, the results are clear and encouraging, justifying additional research within this topic.

5. Conclusions

Volumetric assessment of necrosis is easily attainable, cheap, fast and can help improve prediction of local tumor progression which could lead to earlier diagnosis of LTP, that could lead to better treatment management and, but other factors such as etiology and lesion topography also play an important role in recurrence. Also, with the development of automated software it can become an important biomarker in the prediction of reccurence after ablative procedures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, RD. and IL.; methodology, GI.; software, GI.; validation, RD, MT, MG; formal analysis, GI.; investigation, GI, RD.; resources, MEI.; data curation, MEI.; writing—original draft preparation, GI.; writing—review and editing, GI, RD.; visualization, GI.; supervision, RD, MG, IL.; project administration, RD, IL; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This case series was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fundeni Clinical Institute. Favorable consent was obtained in accordance with the Health Minister Order 1502/2016 with registration number 9832/February 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Availability Statement

not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Llovet, J.M., Kelley, R.K., Villanueva, A. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 7, 6 (2021).

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 69, 182–236 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Reig M Forner, A Rimola J et al. Bclc strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: the 2022 update. Journal of hepatology. 2022:681-693. [CrossRef]

- Vogel A, Martinelli E on behalf of the ESMO Guidelines Committee, Updated treatment recommendations for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) from the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines, March 05, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Crocetti L, de Baere T, Lencioni R. Quality improvement guidelines for radiofrequency ablation of liver tumours. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010 Feb. [CrossRef]

- Chen M Zhang, Y Lau WY. Radiofrequency Ablation for Small Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Dordrecht: Springer; 2016.

- Sandu RM, Paolucci I, Ruiter SJS, Sznitman R, de Jong KP, Freedman J, Weber S, Tinguely P. Volumetric Quantitative Ablation Margins for Assessment of Ablation Completeness in Thermal Ablation of Liver Tumors. Front Oncol. 2021 Mar 10;11:623098. [CrossRef]

- Lachenmayer A, Tinguely P, Maurer MH, Frehner L, Knöpfli M, Peterhans M, et al.. Stereotactic image-guided microwave ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma using a computer-assisted navi-gation system. Liver Int (2019) 39(10):1975–85. [CrossRef]

- Kaye EA, Cornelis FH, Petre EN, Tyagi N, Shady W, Shi W. Volumetric 3D assessment of ablation zones after thermal ablation of colorectal liver metastases to improve prediction of local tumor progression. Eur Radiol (2019) 29(5):2698–705. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed M, Solbiati L, Brace CL, Breen DJ, Callstrom MR, Charboneau JW, et al.. Image-guided Tumor Ablation: Standardization of Terminology and Reporting Criteria—A 10-Year Update. Radiology (2014) 273(1):241–60. [CrossRef]

- Ruo-Fan S, Meng-Su Z, et al Intrahepatic distant recurrence following complete radiofrequency ablation of small hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors and early MRI evaluation, Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International, Volume 14, Issue 6,2015. [CrossRef]

- Toine M. Lodewick, Carsten W.K.P. Arnoldussen, Fast and accurate liver volumetry prior to hepatectomy,HPB,Volume 18, Issue 9,2016,Pages 764-772,ISSN 1365-182X. [CrossRef]

- Bale R, Schullian P, Eberle G, Putzer D, Zoller H, Schneeberger S, et al.. Stereotactic Radiofrequency Ablation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: a Histopathological Study in Explanted Livers. Hepatology (2019). [CrossRef]

- Schaible J, Pregler B, Bäumler W, Einspieler I, Jung MJ, Stroszczynski C, et al.. Safety margin assessment after microwave ablation of liver tumors: inter- and intrareader variability. Radiol Oncol (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lin YM, Paolucci I, O'Connor CS, Anderson BM, Rigaud B, Fellman BM, Jones KA, Brock KK, Odisio BC. Ablative Margins of Colorectal Liver Metastases Using Deformable CT Image Registration and Autosegmentation. Radiology. 2023 Apr;307(2):e221373. [CrossRef]

- Laimer G, Schullian P, Putzer D, Eberle G, Goldberg SN, Bale R. Can accurate evaluation of the treatment success after radiofrequency ablation of liver tumors be achieved by visual inspection alone? Results of a blinded assessment with 38 interventional oncologists. Int J Hyperthermia. 2020 Nov 30;37(1):1362-1367. https://doi.org/10.1080/02656736.2020.1857445. PMID: 33302747. [CrossRef]

- Xia Y, Li C, Zhang P, et al. Artificial intelligence in radiofrequency ablation for liver tumors: a systematic review. Front Oncol 2021;11:665969. [CrossRef]

- Inmutto N, Thaimai S, et al Ablative Volume of Radiofrequency Ablation Related to Intrahepatic Recurrence-Free Survival of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Arab J Intervent Radiol 2022 Apr;5:76–81.

- Grigorie R, Alexandrescu S,, Lupescu I, Boroş M, Grasu M, Dumitru R, Toma M, Croitoru A, Herlea V, Pechianu C, Năstase A, Popescu I. Curative Intent Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma - 844 Cases Treated in a General Surgery and Liver Transplantation Center. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2017 May-Jun;112(3):289-300. [CrossRef]

- Solbiati M, Muglia R, Goldberg N, Tiziana I, Rotilio A, Passera KM, et al.. A novel software platform for volumetric assessment of ablation completeness. Int J Hyperthermia (2019), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Preda C,, Constantinescu I, Gavrila D, Diculescu M, Dumitru R, Recurrence rate of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with treated hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis C virus-associated cirrhosis after mbitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir+dasabuvir+ribavirin therapy. UEG Journal, 7: 699-708, 2019.

- Li M, Li X, Zhou Z, et al. Feasibility of Artificial Intelligence Computed Volumetry for Predicting Intrahepatic Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Radiofrequency Ablation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;53(2):595-605. [CrossRef]

- Bouda, D., Barrau, V., Raynaud, L. et al. Factors Associated with Tumor Progression After Percutaneous Ablation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Comparison Between Monopolar Radiofrequency and Microwaves. Results of a Propensity Score Matching Analysis.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 43, 1608–1618 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Guiu, B. MWA Versus RFA in HCC: Superior? Equivalent? Will We Ever Know?. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 43, 1619–1620 (2020). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).