Submitted:

08 June 2023

Posted:

08 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Developing a robotics platform that will collect visual data automatically.

- Presenting a novel deep learning model for implementing it on the robot onboard computer to detect cracks from the RGB images in real-time.

- Presenting a crack quantification algorithm for finding out crack length, width, and area.

- Finally, presenting a visualization of the crack severity map.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Robotic System for Crack Inspection

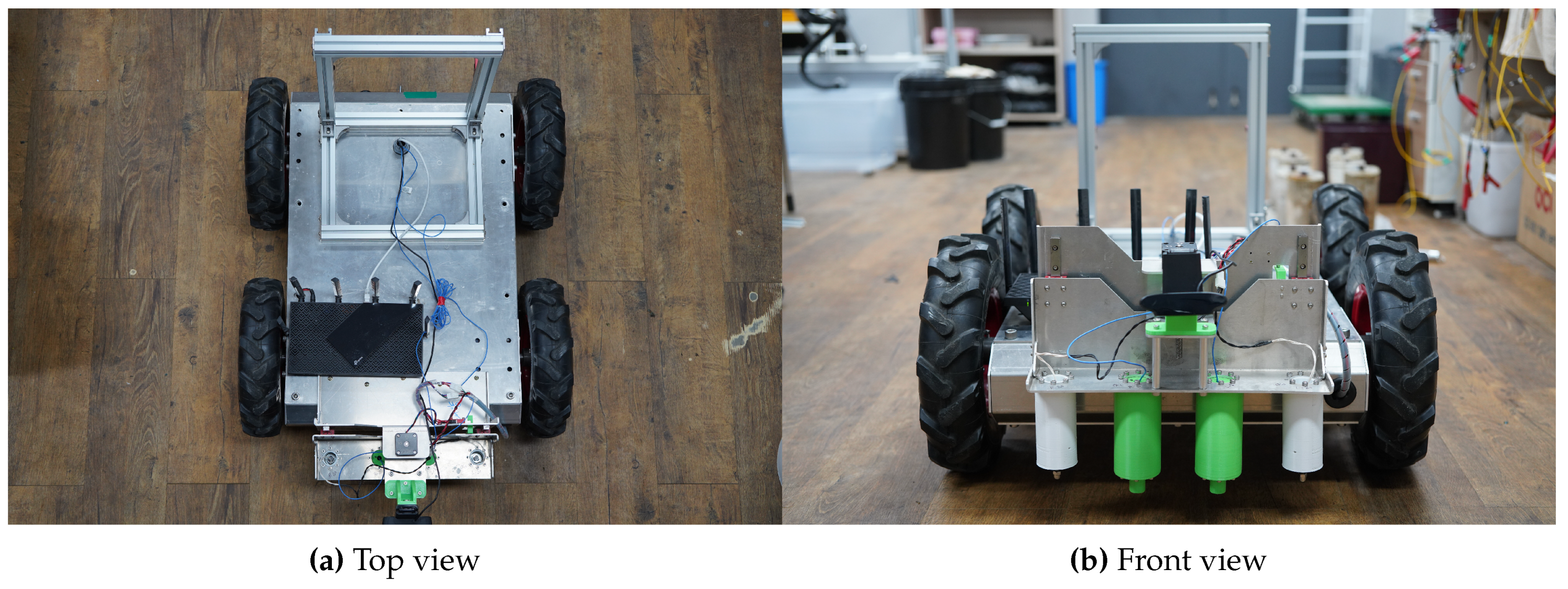

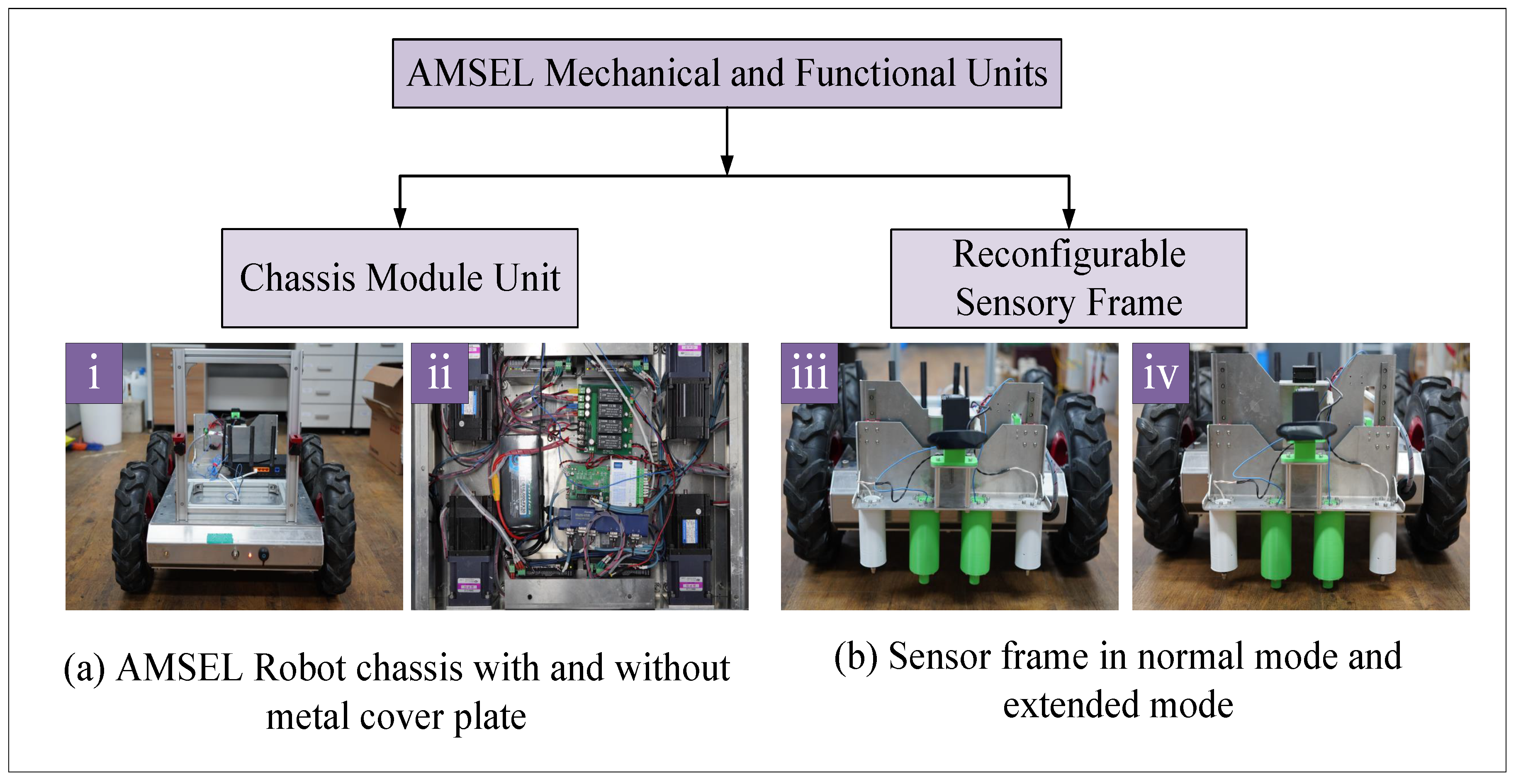

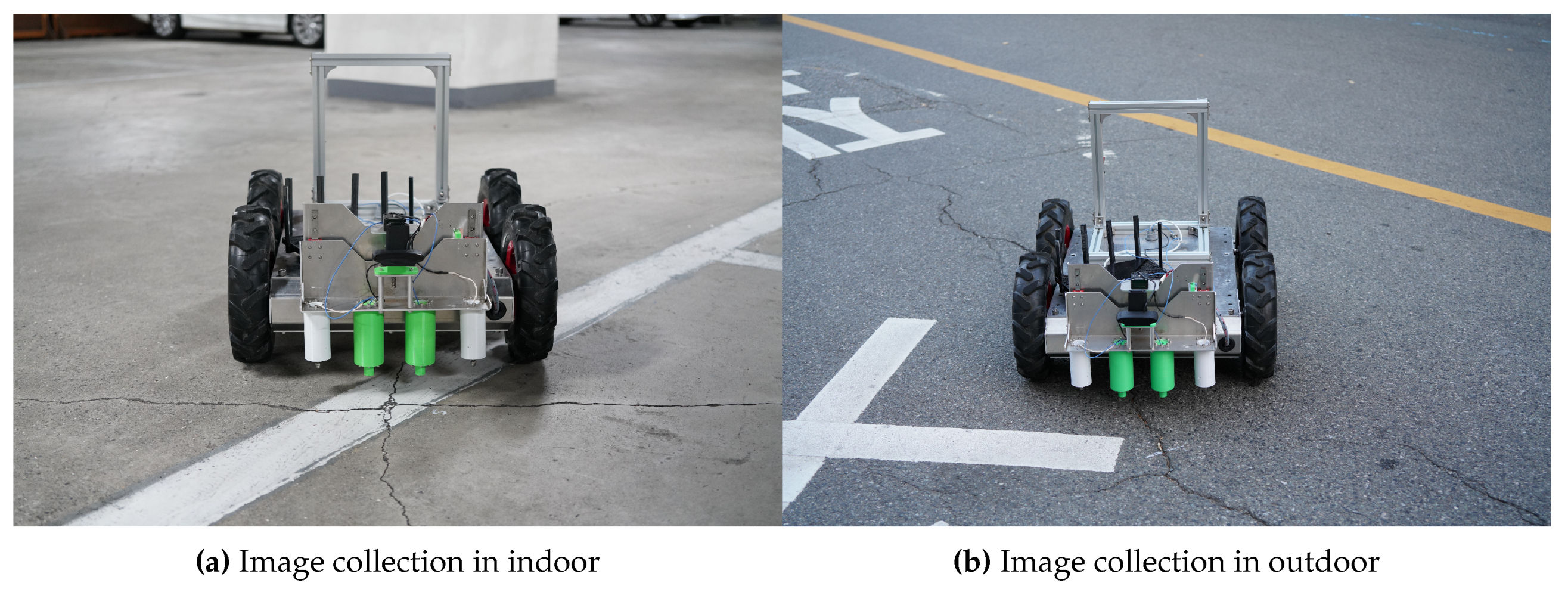

3. Architecture of the AMSEL Robot

3.1. Mechanical Unit

3.1.1. Chassis module

3.1.2. Reconfigurable sensory frame

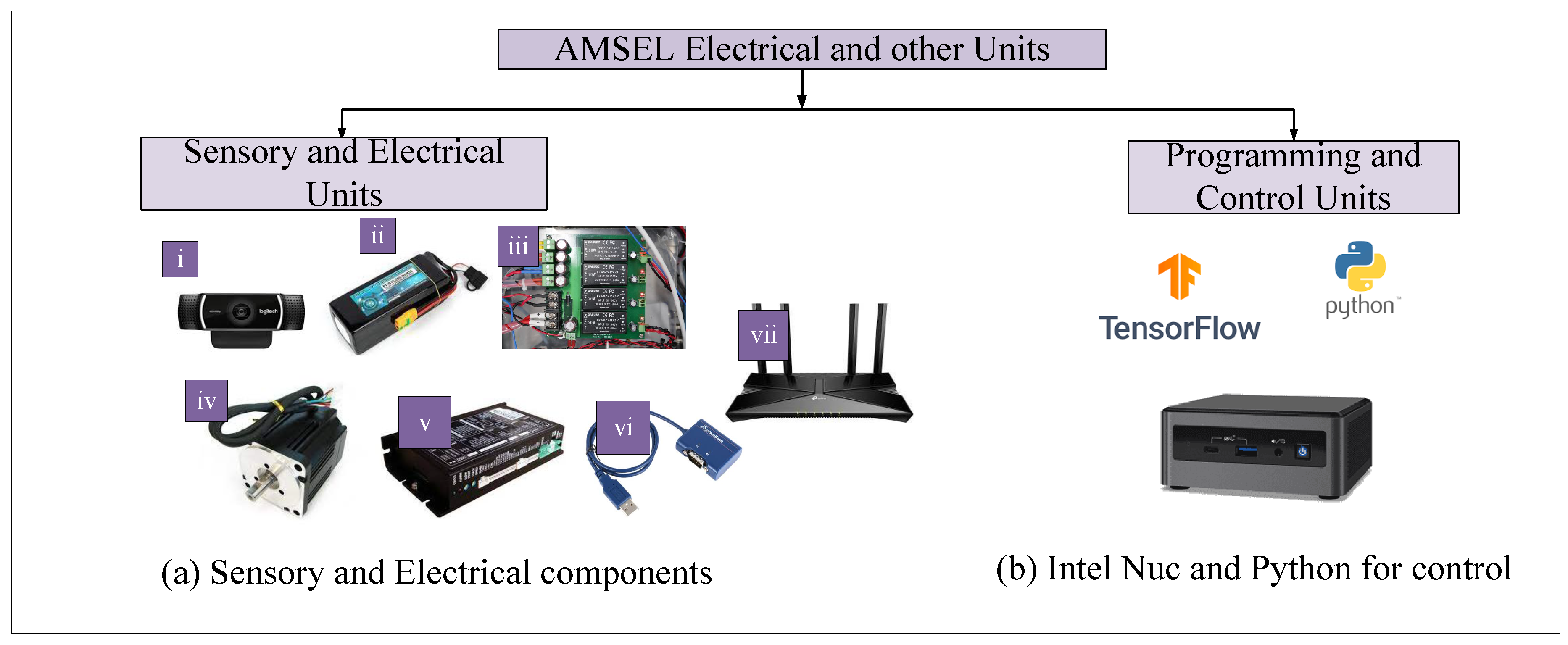

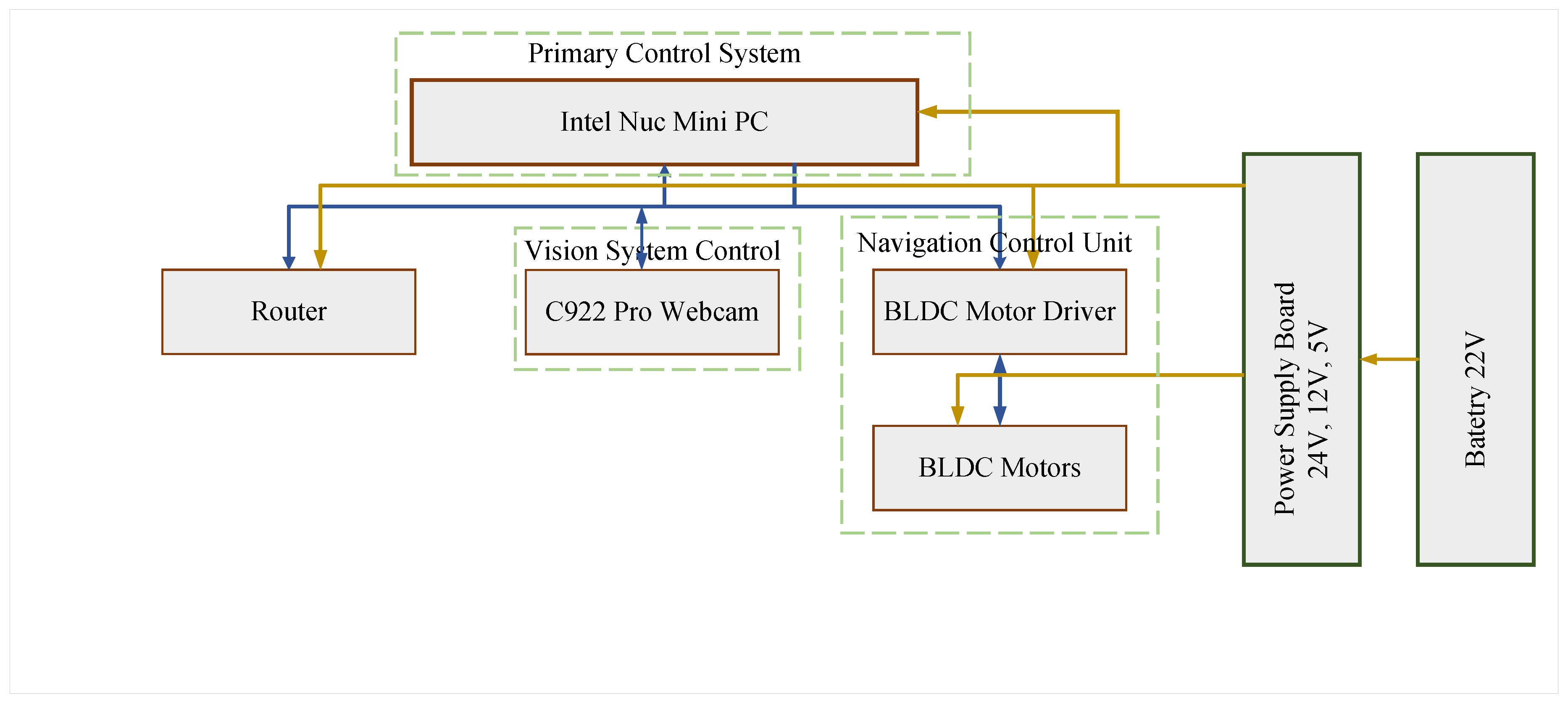

3.2. Electrical & Functional Unit

3.2.1. Electrical Units

- Vision System: A Logitech c922 Pro HD Stream Webcam has been utilized as the vision system of the AMSEL robotic platform (Figure 3a (i)).

- Power source: In the AMSEL robot, a Polytronics Lithium-Polymer (Li-Po) battery has been used as the power source. The model number of the utilized battery is PT-B16-Fx30 (Figure 3a (ii)).

- Power supply board: A custom-designed power supply board has been utilized to split the power from the Li-Po battery among the other electronic devices used in the robotic platform (Figure 3a (iii)).

- DC motors: For navigating the robot, four DC motors have been used in the AMSEL robot (Figure 3a (iv)). The DC motors used in this robot are 200W Brushless DC (BLDC) motors. The model number of these motors is TM90-D0231.

- BLDC motor controller: For driving and controlling the motors in the AMSEL robot four BLDC motor controller have been used (Figure 3a (v)). The model number of the utilized controller is TMC-MD02.

- Serial communication adapter: The AMSEL robotic platform uses multiple serial communication adapters for converting the RS485 communication to USB communication as the system’s main controller uses USB communication protocol (Figure 3a (Vi)).

- Router A Tplink Archer Ax73 outer has been used in the AMSEL robot for communicating with the host pc in the ground station (Figure 3a (vii)).

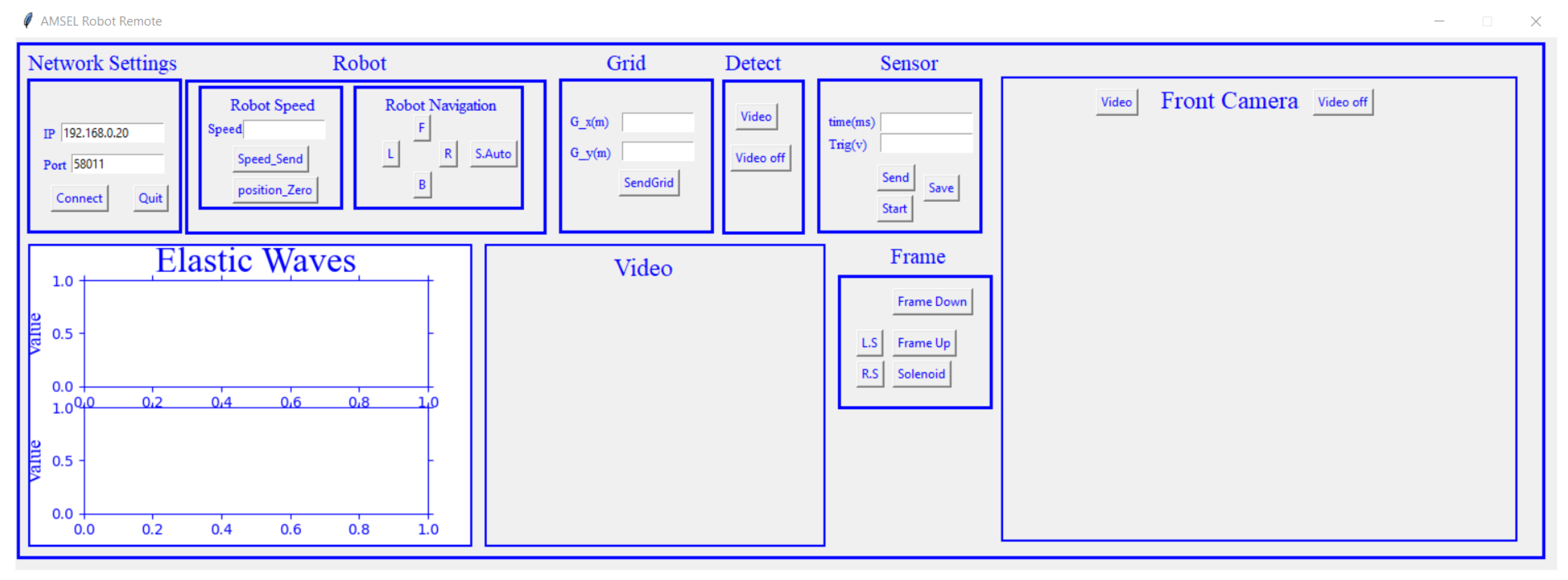

3.2.2. Control Unit

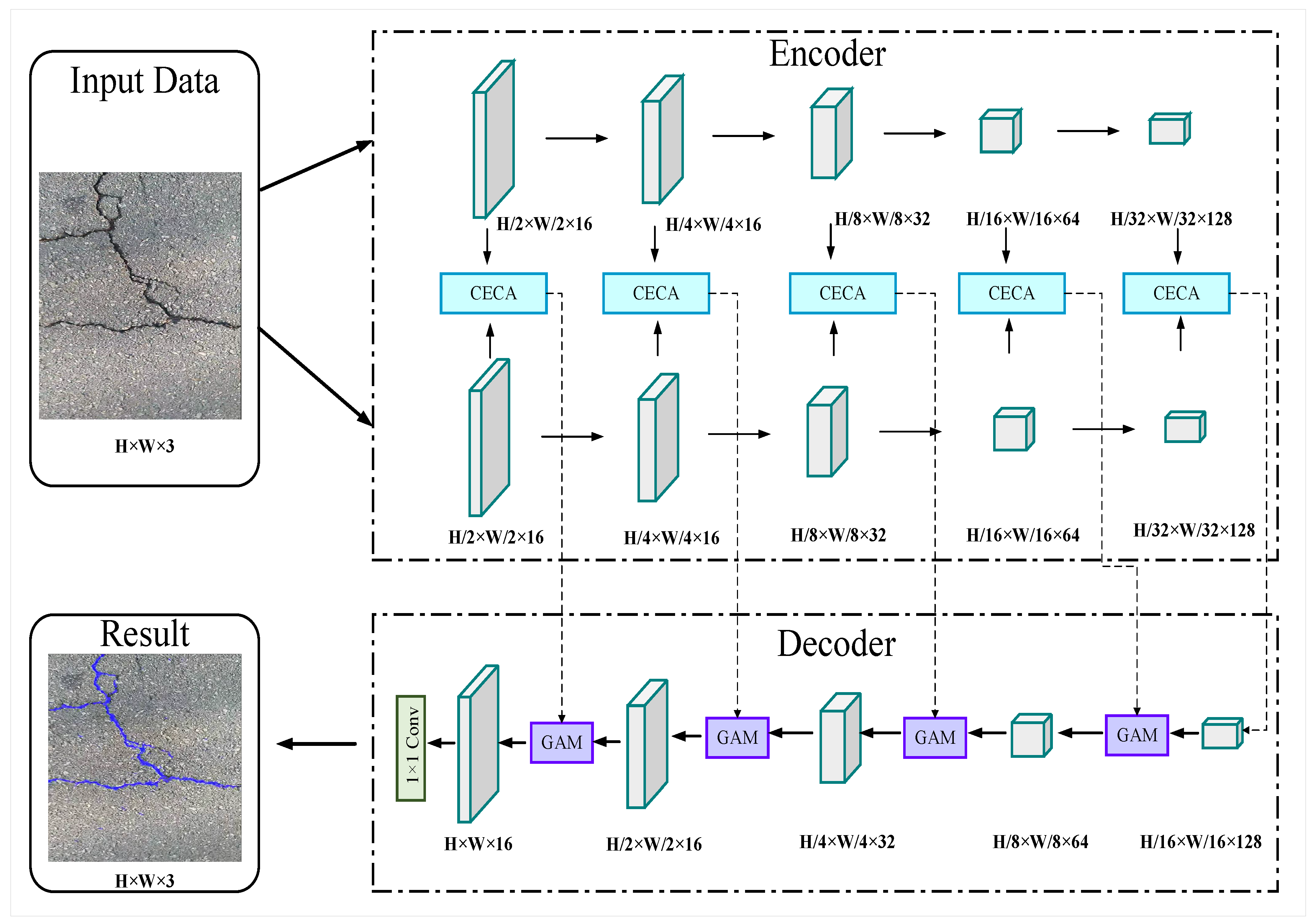

4. Crack Detection and Quantification from Image

4.1. Proposed Architecture for Crack Segmentation

4.1.1. Encoder Module

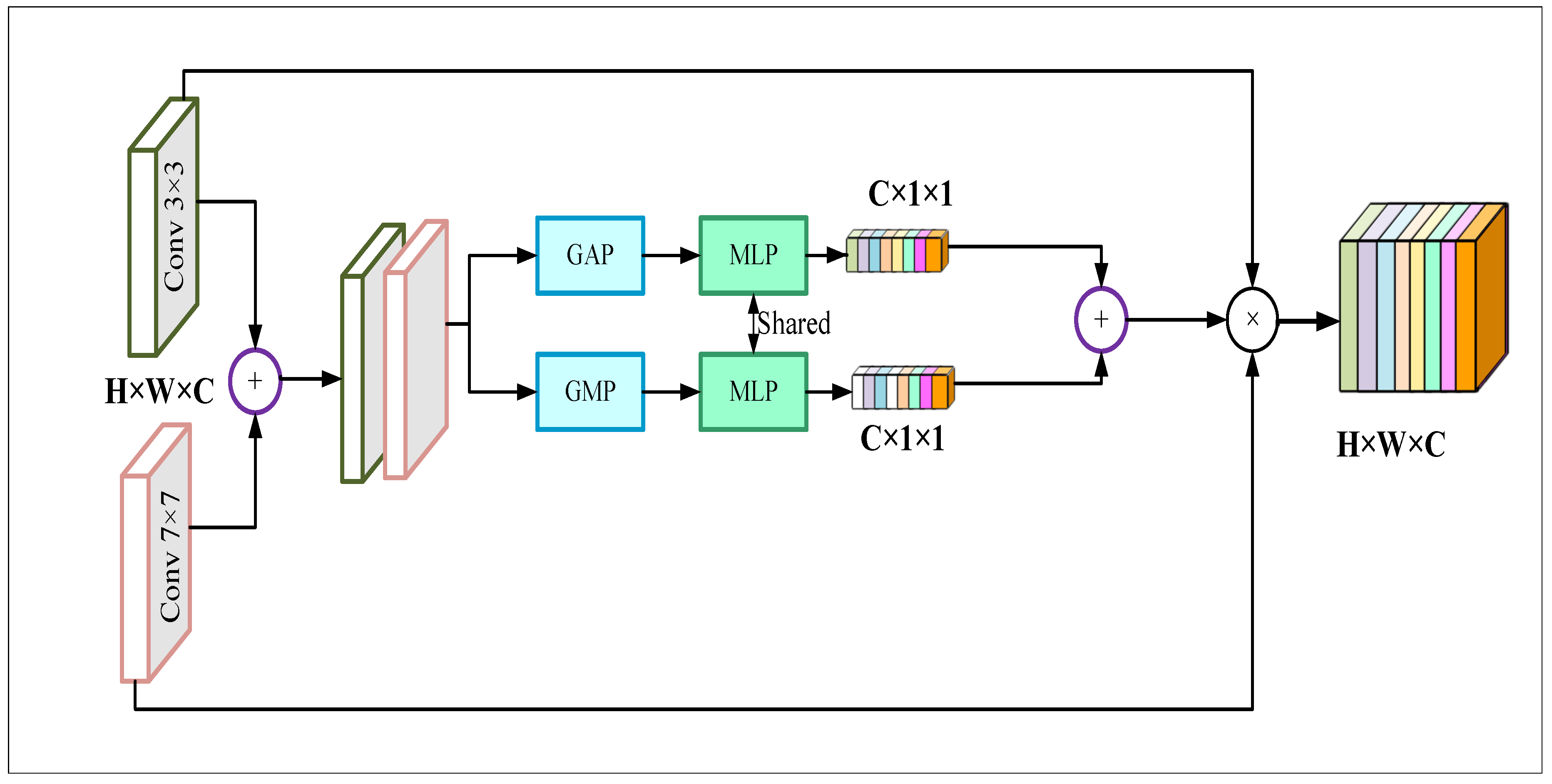

4.1.2. Context Embedded Channel Attention Module

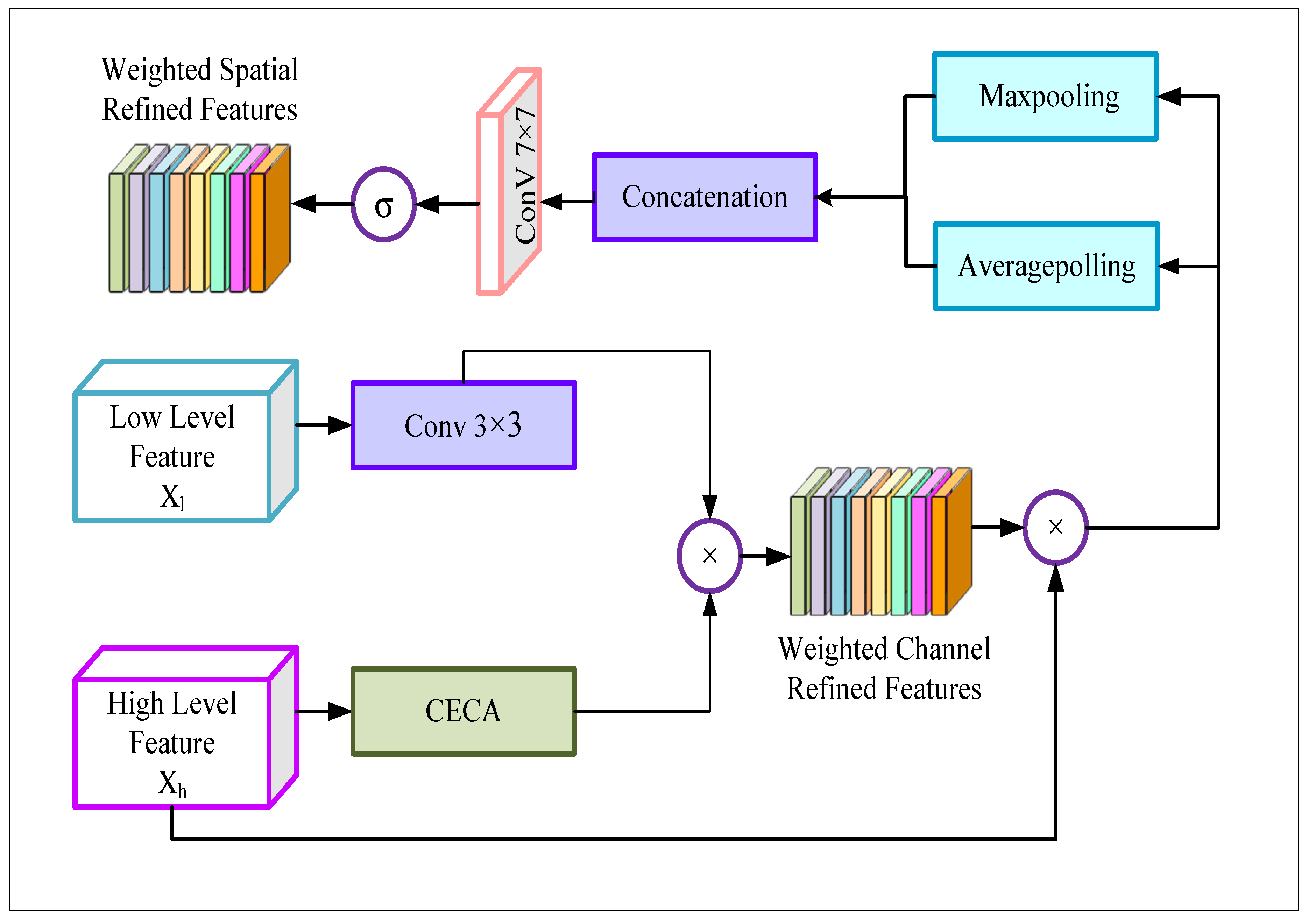

4.1.3. Decoder with Global Attention Module

4.2. Dataset Description & Training of the Model

4.2.1. Dataset

4.2.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Crack Severity Analysis

4.3.1. Counting the Cracks

4.3.2. Extracting Morphological Features

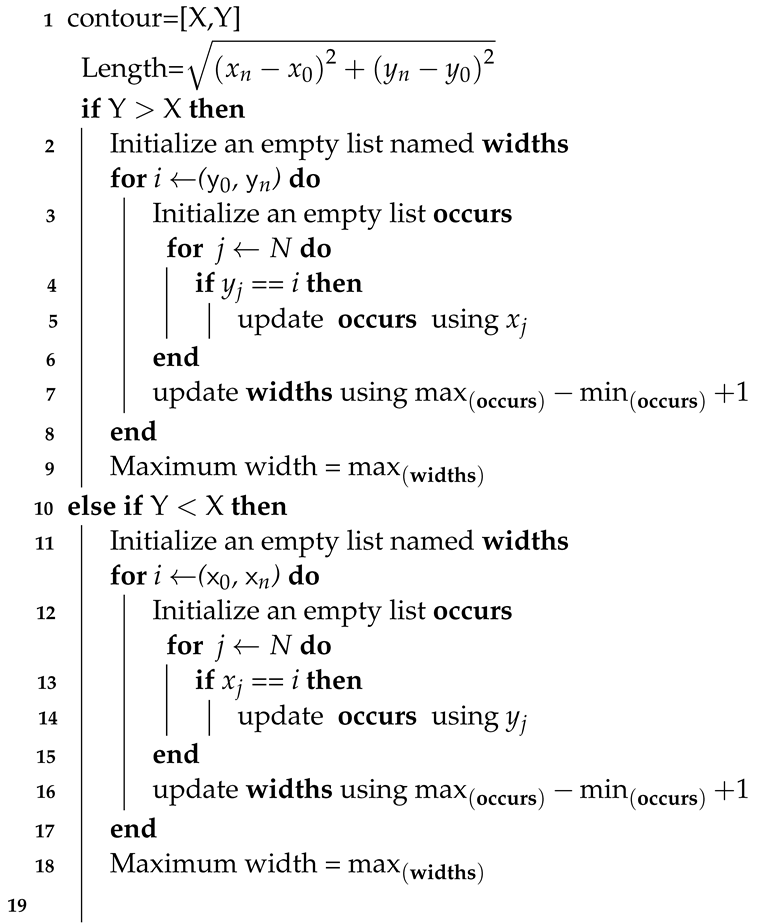

| Algorithm 1: Algorithm for length and width calculation |

|

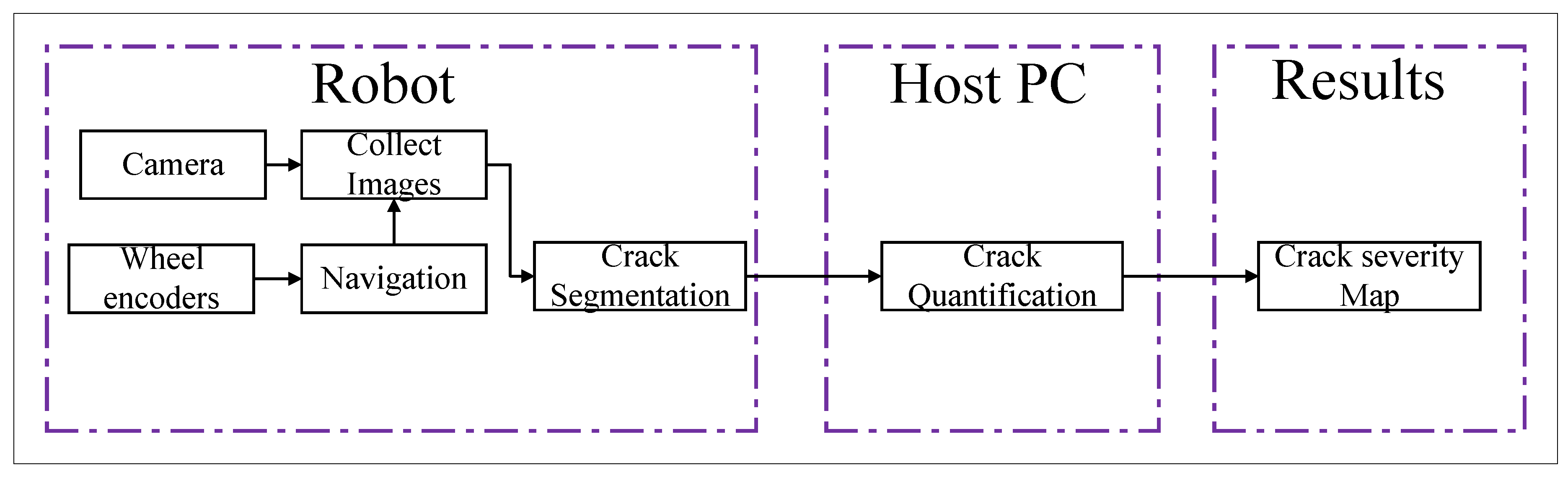

5. AMSEL Robot Working Method

5.1. Manual Navigation and Pavement Inspection

5.2. Automated Navigation and Pavement Inspection

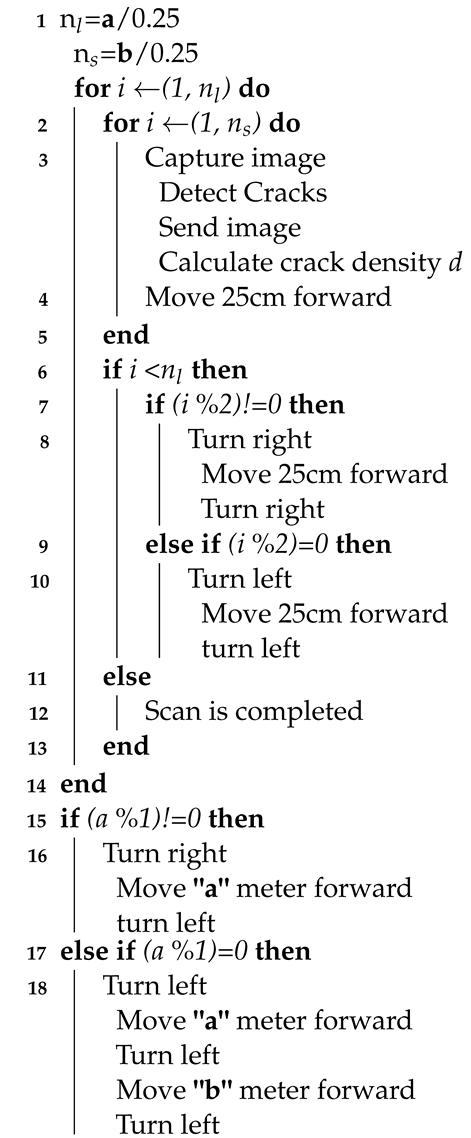

| Algorithm 2: Algorithm for automated navigation and inspection |

|

6. Results & Discussion

6.1. Performance of the Deep Learning Model

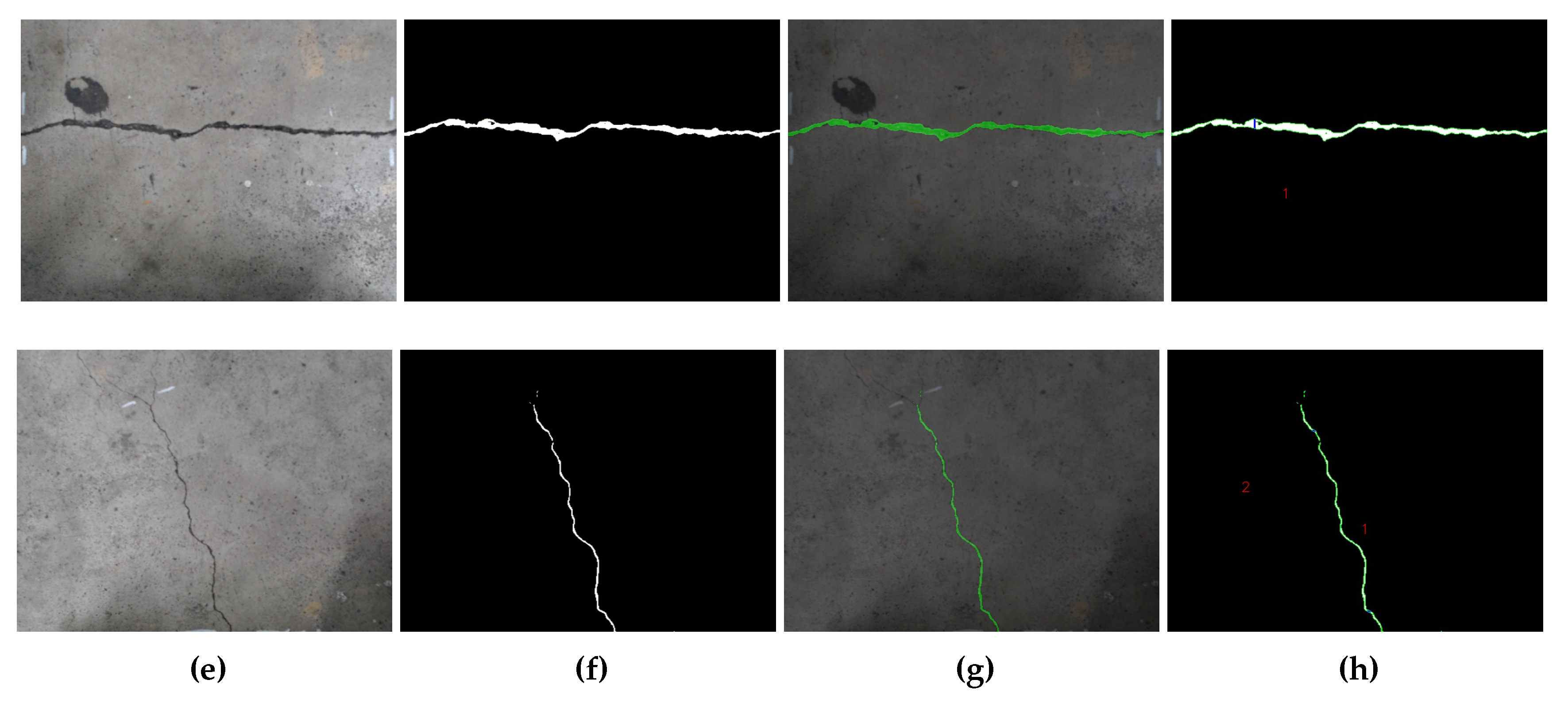

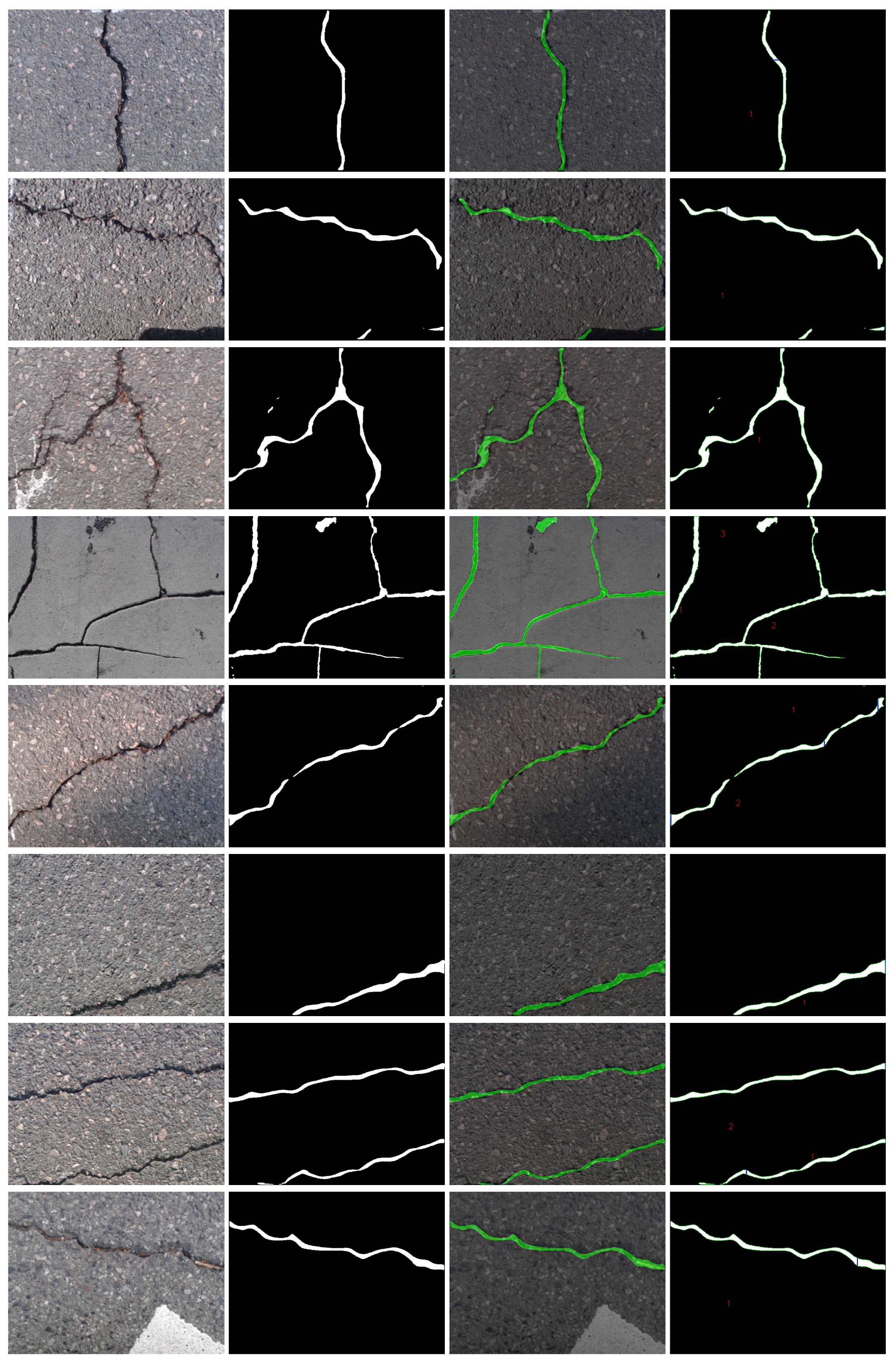

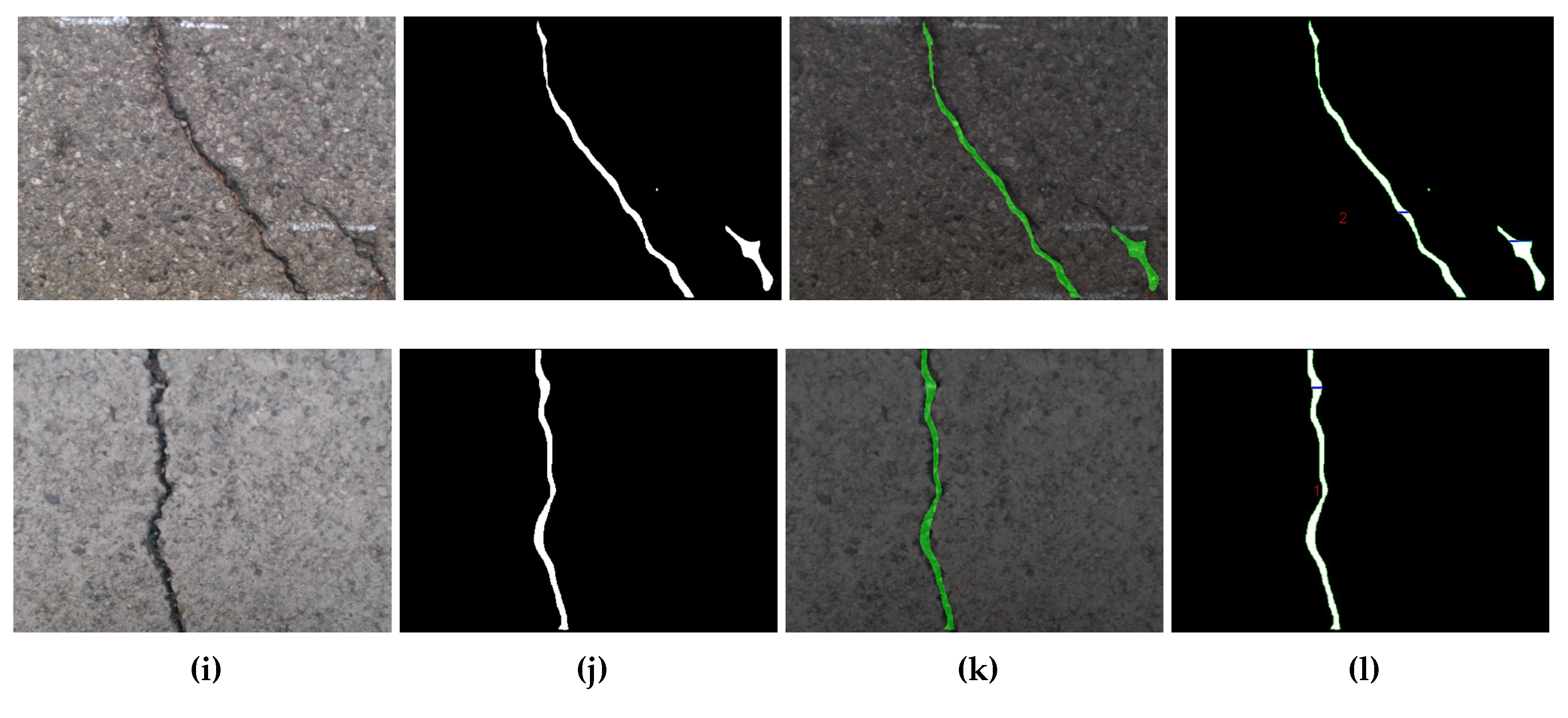

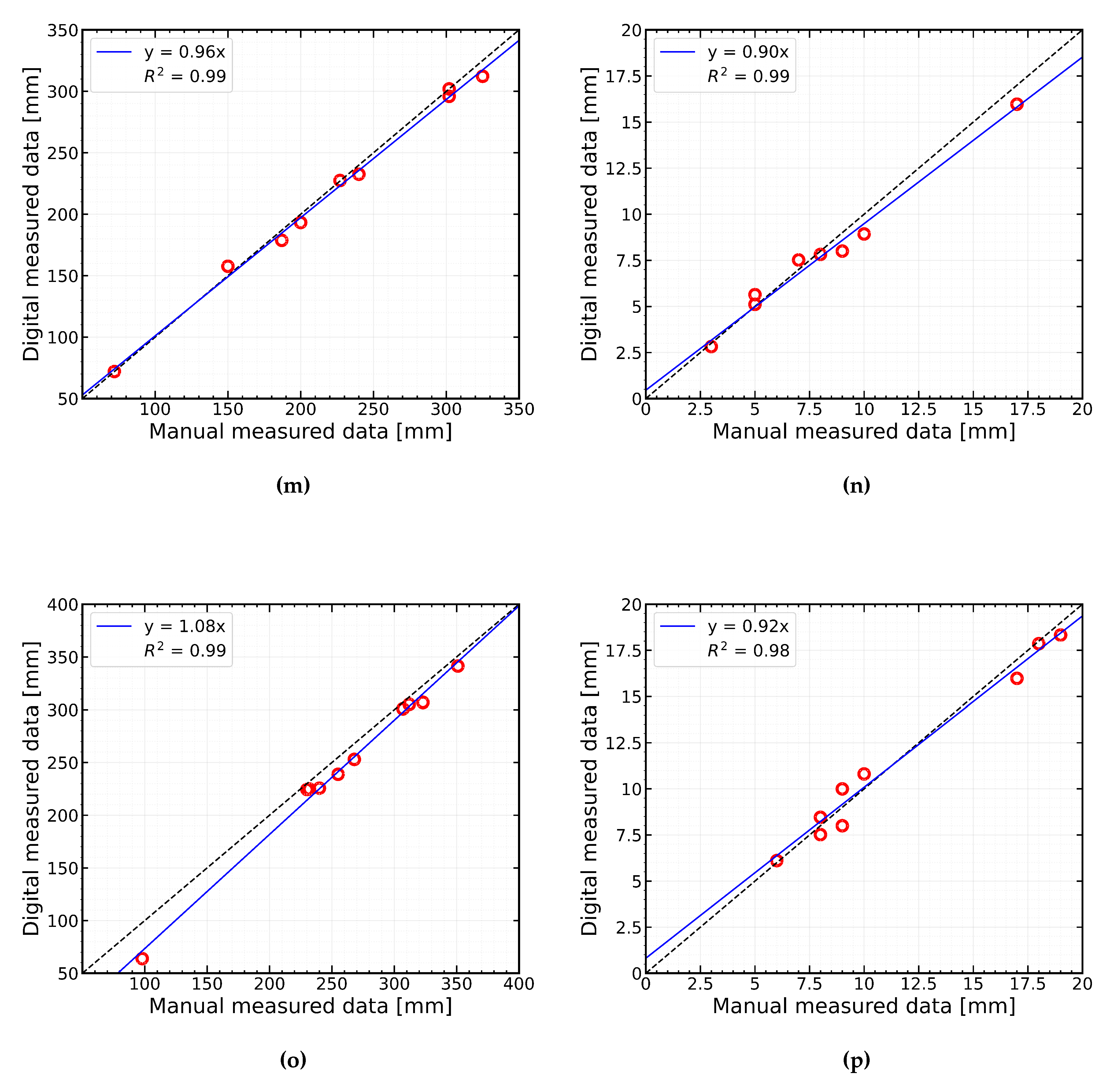

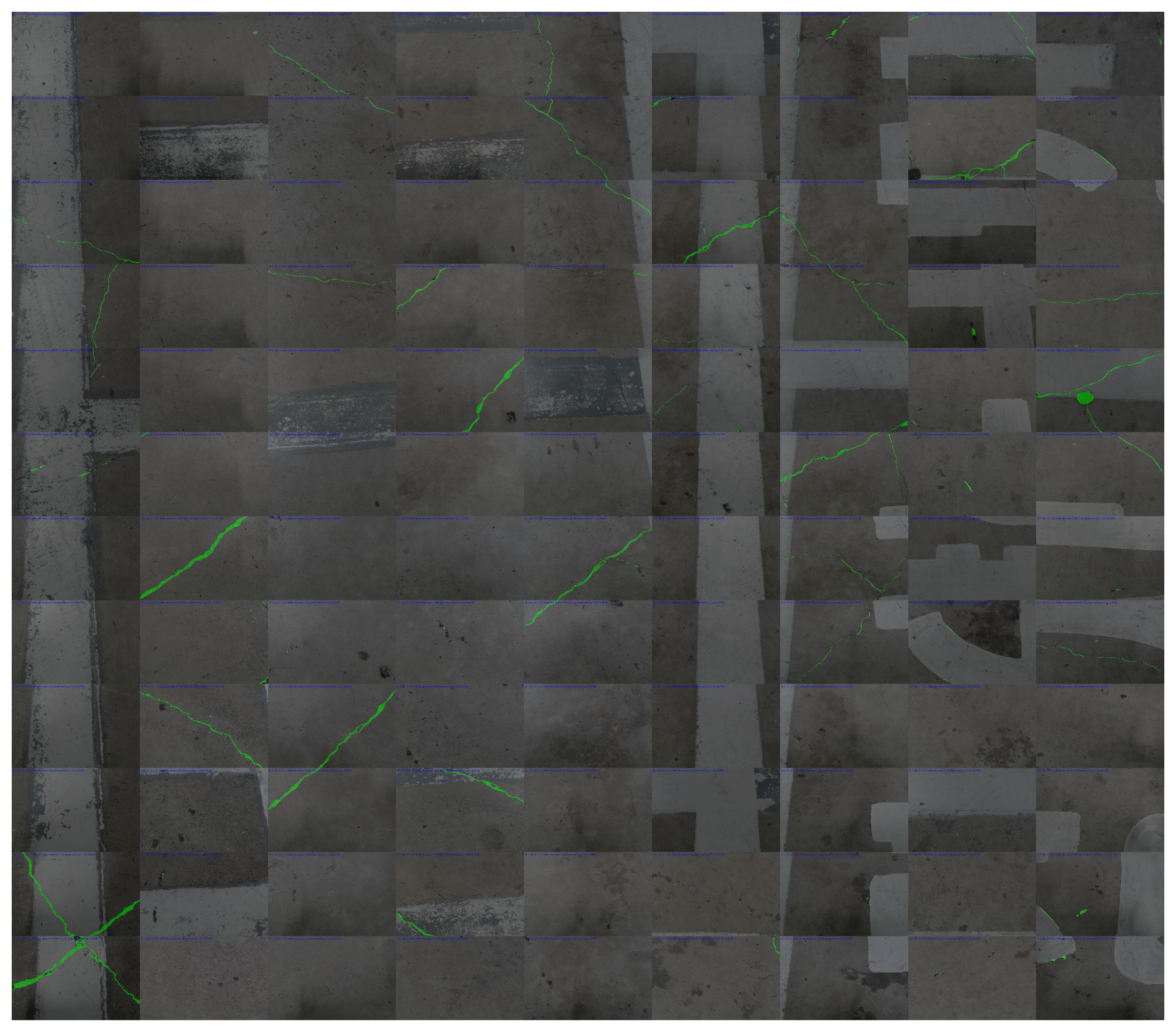

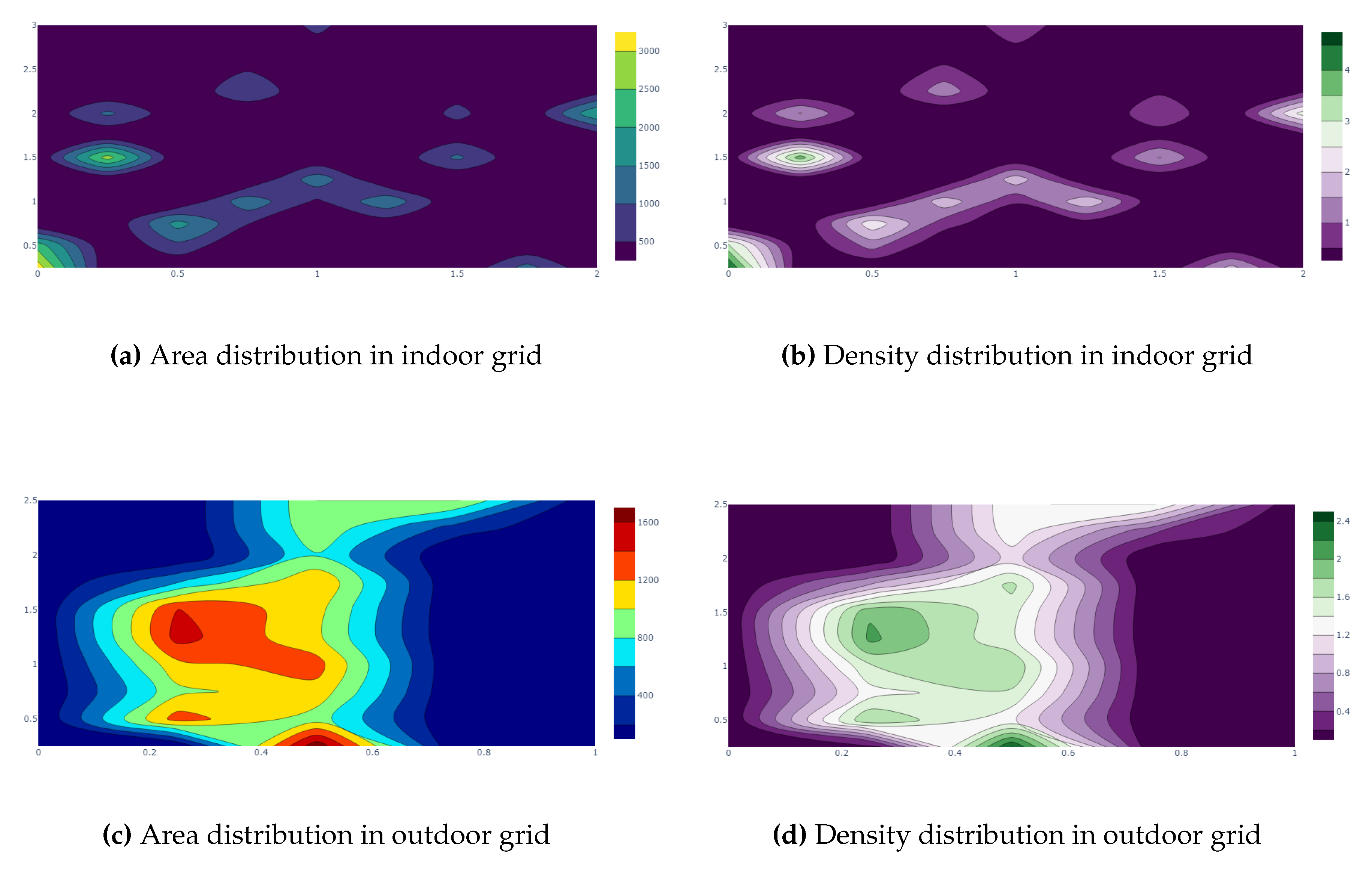

6.2. Pavement Assessment in Manual Mode

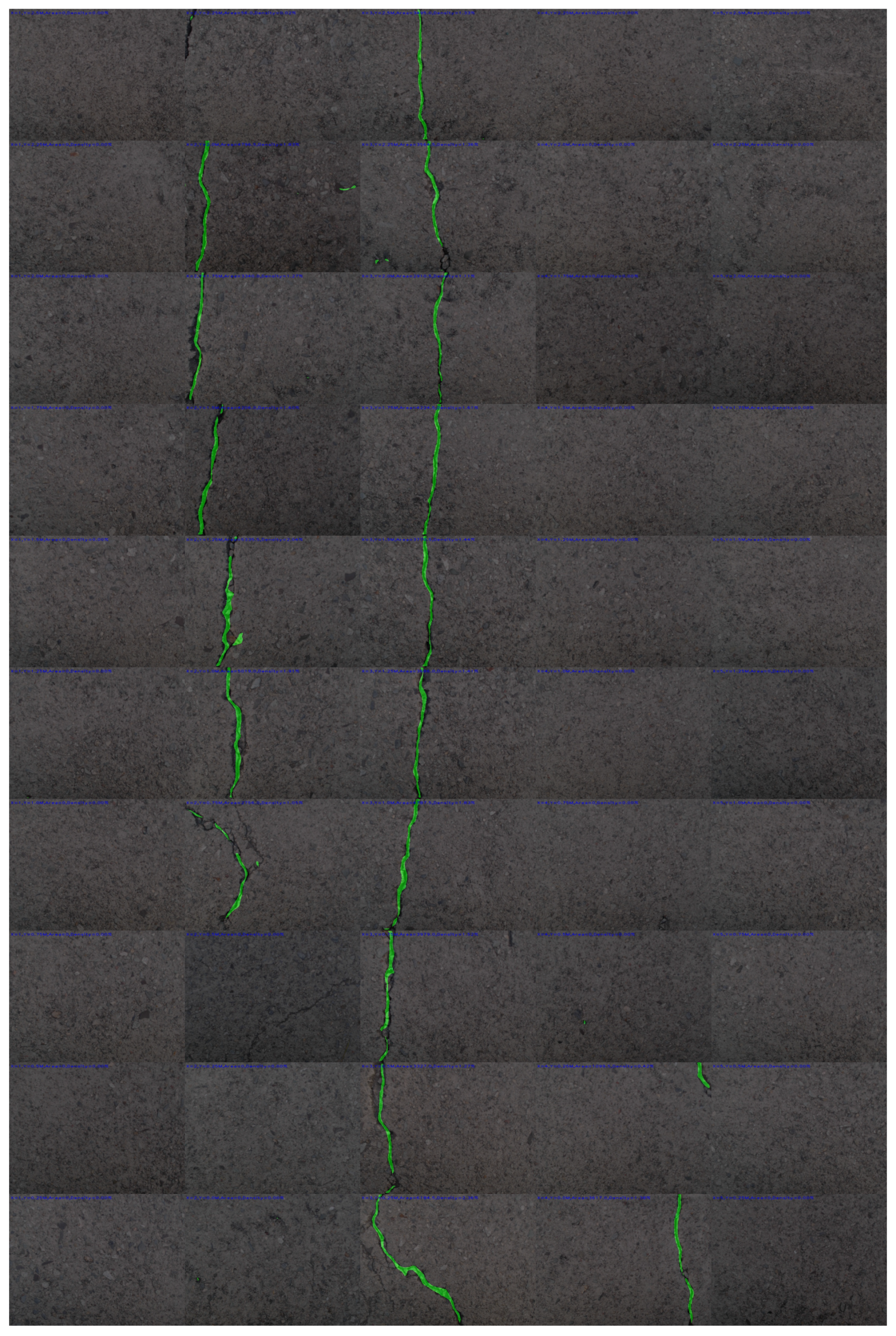

6.3. Pavement Assessment in Automated Mode

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- R. B. Lee, “Development of korean highway capacity manual,” Highway Capacity and Level of Service, pp. 233–238, 2021.

- C. Chen, H. Seo, C. H. Jun, and Y. Zhao, “A potential crack region method to detect crack using image processing of multiple thresholding,” Signal, Image and Video Processing, vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 1673–1681, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Akagic, E. Buza, S. Omanovic, and A. Karabegovic, “Pavement crack detection using otsu thresholding for image segmentation,” 2018 41st International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Nigam and S. K. Singh, “Crack detection in a beam using wavelet transform and photographic measurements,” Structures, vol. 25, pp. 436–447, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Zoubir, M. Rguig, M. El Aroussi, A. Chehri, and R. Saadane, “Concrete Bridge Crack Image classification using histograms of oriented gradients, uniform local binary patterns, and kernel principal component analysis,” Electronics, vol. 11, no. 20, p. 3357, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Gehri, J. Mata-Falcón, and W. Kaufmann, “Automated Crack Detection and measurement based on digital image correlation,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 256, p. 119383, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Medina, J. Llamas, J. Gómez-García-Bermejo, E. Zalama, and M. Segarra, “Crack detection in concrete tunnels using a Gabor filter invariant to rotation,” Sensors, vol. 17, no. 7, p. 1670, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H.-N. Nguyen, T.-Y. Kam, and P.-Y. Cheng, “An automatic approach for accurate edge detection of concrete crack utilizing 2D geometric features of crack,” Journal of Signal Processing Systems, vol. 77, no. 3, pp. 221–240, 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. Chun, S. Izumi, and T. Yamane, “Automatic detection method of cracks from concrete surface imagery using two-step light gradient boosting machine,” Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 61–72, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Vedrtnam, S. Kumar, G. Barluenga, and S. Chaturvedi, “Early crack detection using modified Spectral Clustering Method assisted with FE analysis for distress anticipation in cement-based composites,” 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, F. Yang, Y. Daniel Zhang, and Y. J. Zhu, “Road crack detection using deep convolutional neural network,” 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y.-J. Cha, W. Choi, and O. Büyüköztürk, “Deep learning-based crack damage detection using convolutional neural networks,” Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 361–378, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Eisenbach, R. Stricker, D. Seichter, K. Amende, K. Debes, M. Sesselmann, D. Ebersbach, U. Stoeckert, and H.-M. Gross, “How to get pavement distress detection ready for deep learning? A systematic approach,” 2017 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, Z. Han, H. Xu, L. Liu, X. Li, and K. Zhang, “Yolov3-Lite: A lightweight crack detection network for aircraft structure based on depthwise separable convolutions,” Applied Sciences, vol. 9, no. 18, p. 3781, 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Li, S. Zheng, C. Wang, S. Zhao, X. Chai, L. Peng, Q. Tong, and J. Wang, “Crack Detection Method of sleeper based on Cascade Convolutional Neural Network,” Journal of Advanced Transportation, vol. 2022, pp. 1–14, 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Yang, H. Li, Y. Yu, X. Luo, T. Huang, and X. Yang, “Automatic pixel-level crack detection and measurement using fully convolutional network,” Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering, vol. 33, no. 12, pp. 1090–1109, 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Polovnikov, D. Alekseev, I. Vinogradov, and G. V. Lashkia, “DAUNet: Deep Augmented Neural Network for pavement crack segmentation,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 125714–125723, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Yong and N. Wang, “RIIAnet: A real-time segmentation network integrated with multi-type features of different depths for pavement cracks,” Applied Sciences, vol. 12, no. 14, p. 7066, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S.-N. Yu, J.-H. Jang, and C.-S. Han, “Auto inspection system using a mobile robot for detecting concrete cracks in a tunnel,” Automation in Construction, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 255–261, 2007. [CrossRef]

- P. Oyekola, A. Mohamed*, and J. Pumwa, “Robotic model for unmanned crack and corrosion inspection,” International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 862–867, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, D. Song, Y. Liu, and B. Li, “Automatic pavement crack detection by multi-scale image fusion,” IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 2025–2036, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. M. La, T. H. Dinh, N. H. Pham, Q. P. Ha, and A. Q. Pham, “Automated robotic monitoring and inspection of steel structures and Bridges,” Robotica, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 947–967, 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. M. La, N. Gucunski, K. Dana, and S.-H. Kee, “Development of an autonomous bridge deck inspection robotic system,” Journal of Field Robotics, vol. 34, no. 8, pp. 1489–1504, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Kolvenbach, G. Valsecchi, R. Grandia, A. Ruiz, F. Jenelten, and M. Hutter, “Tactile inspection of concrete deterioration in sewers with legged robots,” in Proc. 12th Conf. Field Service Robot., 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. V. K. Le, Z. Chen, and R. Rajkumar, “Multi-sensors in-line inspection robot for pipe flaws detection,” IET Science, Measurement & Technology, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 71–82, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Lei, Y. Ren, N. Wang, L. Huo, and G. Song, “Design of a new low-cost unmanned aerial vehicle and vision-based concrete crack inspection method,” Structural Health Monitoring, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 1871–1883, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Pan, X. Zhang, G. Cervone, and L. Yang, “Detection of asphalt pavement potholes and cracks based on the unmanned aerial vehicle multispectral imagery,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, vol. 11, no. 10, pp. 3701–3712, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Montero, E. Menendez, J. G. Victores, and C. Balaguer, “Intelligent robotic system for autonomous crack detection and caracterization in concrete tunnels,” 2017 IEEE International Conference on Autonomous Robot Systems and Competitions (ICARSC), 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Yang, B. Li, W. Li, H. Brand, B. Jiang, and J. Xiao, “Concrete defects inspection and 3D mapping using CityFlyer Quadrotor Robot,” IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 991–1002, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Gui and H. Li, “Automated defect detection and visualization for the robotic airport runway inspection,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 76100–76107, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Ramalingam, A. A. Hayat, M. R. Elara, B. Félix Gómez, L. Yi, T. Pathmakumar, M. M. Rayguru, and S. Subramanian, “Deep learning based pavement inspection using self-reconfigurable robot,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 8, p. 2595, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. He, S. Jiang, J. Zhang, and G. Wu, “Automatic damage detection using anchor-free method and unmanned surface vessel,” Automation in Construction, vol. 133, p. 104017, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Yang, B. Li, J. Feng, G. Yang, Y. Chang, B. Jiang, and J. Xiao, “Automated Wall-climbing robot for Concrete Construction Inspection,” Journal of Field Robotics, 2022. [CrossRef]

- , B. Xiong, X. Li, X. Sang, and Q. Kong, “A novel intelligent inspection robot with deep stereo vision for three-dimensional concrete damage detection and quantification,” Structural Health Monitoring, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 788–802, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Yang, L. Zhang, S. Yu, D. Prokhorov, X. Mei, and H. Ling, “Feature pyramid and hierarchical boosting network for pavement crack detection,” IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 1525–1535, 2020. [CrossRef]

| Researchers | Inspected Structure | Robot Platform | Deep Learning | Remarks |

| Yu et al.[19] | Concrete Tunnel | Mobile robot | No | Images were collected by the robotic system. An image processing algorithm was utilized in an external computer for detecting cracks and crack information. |

| Oyekola et al.[20] | Concrete Tank | Mobile robot | No | Images were collected by the robotic system. A threshold-based algorithm was used in another computer for detecting the cracks. No postprocessing techniques were applied for obtaining geometrical information about the cracks. |

| Li et al.[21] | Concrete pavement | Guimi robot co ltd. | No | Detected crack using an unsupervised learning algorithm named MFCD. Detection was not performed in onboard ocmputer |

| La et al.[22] | Steel bridge | Wall climbing robot | No | Images were collected and passed to the ground station in real-time. Cracks were detected using the Hessian-matrix algorithm. Images were stitched and reconstructed to 3d for giving a visual idea. |

| La et al.[23] | Bridge deck | Seekur robot | No | Combined visual sensor and NDE sensors for crack inspection. Presented stitched images after crack detection and delamination map. |

| Hendrik et al.[24] | Concrete sweres | ANYmal (legged robot) | Yes (Machine learning) | Tactile sensory system were used to collect time series signals from the footstep of ANYmal and Support Vector Machine (SVM) were used to classify good, satisfactory, fair, critical, failure types or cracks. |

| Le et al.[25] | Concrete pipe | Mobile robot | Yes (Machine Learning) | Data from the camera and other sensors were fused to classify using SVM for detecting cracks. |

| Lei et al.[26] | Concrete Pavement | UAV | Yes (Machine Learning) | Images were collected by a CCD camera and the cracks were detected in the onboard computer of the UAV by SVM. The crack parameters were also computed. |

| Pan et al.[27] | Asphalt pavement | UAV | Yes (Machine learning) | Colected images using the UAV and the cracks were detected using Random Forest (RF), SVM, Artificial Neural Network (ANN) models. |

| Montero et al.[28] | Concrete Tunnel | Mobile robot | Yes | Collected RGB images using a camera and ultrasound data by an ultrasonic sensor. The data were passed to another computer for processing. A CNN model was used for detecting cracks from the images and a traditional method was used for estimating crack depth from the ultrasonic data. |

| Li et al.[29] | Concrete Bridge | Flying robot | Yes | A deep learning model was developed named Adanet for detecting cracks and 3d metrics were also reconstructed for getting the crack location and severity information. A dataset named Concrete Structure spalling and Cracking (CSSC) was also developed by this system. |

| Gui et al.[30] | Airport pavement | ARIR robot | Yes | Both surface and subsurface data were collected by a camera and GPR interfaced into the robotic system. An intensity-based algorithm and voting-based CNN were applied for processing image and GPR data. A large-scale stitched image was presented to visualize the cracks. |

| Ramalingam et al.[31] | Concrete pavement | Panthera robot | Yes | A SegNet-based model was developed to detect cracks and garbage. The system detects cracks on the onboard computer (Nvidia Jetson nano). A Mobile Mapping System was also utilized to localize the cracks. |

| He et al.[32] | Concrete Bridge | USV | Yes | A USV was applied to detect cracks in the bottom of a concrete bridge. The system detects cracks on the onboard computer (Intel NUC Mini PC) using cenWholeNet from the RGB and Lidar data. The results are then passed to the ground station in real-time. |

| Yang et al.[33] | Concrete wall | Climbing robot | Yes | A network named InspectionNet was used for detecting the cracks from the RGB-D camera on the onboard computer (Intel Nuc Mini PC) of the robotic system. A map-fusion module was also proposed to highlight the cracks. |

| Yuan et al.[34] | Reinforced concrete | Mobile robot | Yes | This robotic system used the stereo camera for collecting pictures and utilized a Mask RCNN model on the onboard computer (Nvidia Jetson nano) to detect cracks. A UI was also developed which controls the robot and receives data using WebSocket protocol. A 3d point cloud was reconstructed from the actual size of the cracks. |

| Parameter | Dimension | Unit |

| AMSEL Height | 21 | cm |

| AMSEL Width | 48.5 | cm |

| AMSEL Length (with sensor frame) | 91 | cm |

| AMSEL Length (without sensor frame) | 74 | cm |

| Sensor frame height | 35.3 | cm |

| Sensor frame length | 17 | cm |

| Sensor frame width | 36 | cm |

| Wheel numbers | 4 | - |

| Wheel radius | 13.25 | cm |

| Continuous driving time | >4 | hrs |

| Power source | Lipo battery | 22V |

| Sensor | RGB camera, vibration sensor | - |

| Accuracy (%) | Dice Coefficient (%) | IoU (%) | Dice Loss(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train set | 96.35 | 97.40 | 97.35 | 0.0180 |

| Test set | 96.29 | 97.33 | 96.90 | 0.0214 |

| Measurements (M) | Severity | Limit |

| Area (mm) | Fair | M<0.4% |

| Poor | 0.4% ≤ M<1 % | |

| Severe | M>1 % |

| Picture | Number of cracks | Manual length | Manual maximum width | No of cracks after prediction | Digital Length | Digital Maximum Width | Area | Density | Severity |

| 1.jpg | 1 | 227mm | 10mm | 1 | 227.45mm | 8.93mm | 1039.75mm2 | 1.44%. | Severe |

| 2.jpg | 2 | 72mm, 187mm | 3mm, 7mm | 2 | 72.04mm, 178.75mm | 2.82mm, 7.52mm | 484.675mm2 | 0.67%. | Poor |

| 3.jpg | 1 | 302mm | 17mm | 1 | 295.91mm | 15.97mm | 2123.575mm2 | 2.94%. | Severe |

| 4.jpg | 1 | 150mm | 5mm | 1 | 157.67mm | 5.11mm | 318.66mm2 | 0.44%. | Poor |

| 5.jpg | Web crack | - | - | Web crack | - | - | 4330.93mm2 | 6%. | Severe |

| 6.jpg | 1 | 240mm | 5mm | 1 | 232.56mm | 5.64mm | 344.98mm2 | 0.47%. | Poor |

| 7.jpg | 1 | 325mm | 8mm | 1 | 312.24mm | 7.82mm | 545.32mm2 | 0.83%. | Poor |

| 8.jpg | Web crack | - | - | Web crack | -mm | - | 599.83mm2 | 0.88%. | Poor |

| 9.jpg | 1 | 302mm | 9mm | 1 | 302mm | 8mm | 1227.775mm2 | 1.70%. | Severe |

| 10.jpg | 1 | 200mm | 3mm | 1 | 192.28mm | 2.82mm | 200.33mm2 | 0.32%. | Fair |

| Picture | Number of cracks | Manual length | Manual maximum width | No of cracks after prediction | Digital Length | Digital Maximum Width | Area | Density | Severity |

| 11.jpg | 1 | 232mm | 8mm | 1 | 224.87mm | 7.52mm | 1144.09mm2 | 1.59%. | Severe |

| 12.jpg | 1 | 307mm | 10mm | 1 | 300.86mm | 10.81mm | 1912.665mm2 | 2.65%. | Severe |

| 13.jpg | Web crack | - | - | Web crack | - | - | 2747.5mm2 | 3.81%. | Severe |

| 14.jpg | Web crack | - | - | Web crack | - | - | 3699.37mm2 | 5.12%. | Severe |

| 15.jpg | 1 | 351mm | 17mm | 1 | 341.33mm | 15.81mm | 1713.26mm2 | 2.37%. | Severe |

| 16.jpg | 1 | 240mm | 9mm | 1 | 225.67mm | 18.33mm | 1712.32mm2 | 2.37%. | Severe |

| 17.jpg | 2 | 312mm, 255mm | 9mm,6mm | 2 | 305.15mm, 238.87mm | 8mm, 6.11mm | 2575.13mm2 | 3.56%. | Severe |

| 18.jpg | 1 | 323mm | 10mm | 1 | 306.92mm | 10.81mm | 1841.572mm2 | 2.55%. | Severe |

| 19.jpg | 2 | 268mm, 98mm | 8mm,18mm | 2 | 253mm, 63.92mm | 8.46mm, 17.86mm | 1487.54mm2 | 2.06%. | Severe |

| 20.jpg | 1 | 230mm | 9mm | 1 | 224.43mm | 10mm | 1179.81mm2 | 1.63%. | Severe |

| Number of cracks | Maximum Area | Minimum Area | Total Area | Total Density |

| 43 | 3841.995mm2, Loc. (x=0m, y=0.25m) | 38.305mm2 ,Loc. (x=2m, y=3m) | 22617.69mm2 | 0.38% |

| Number of cracks | Maximum Area | Minimum Area | Total Area | Total Density |

| 18 | 1741.35mm2, Loc. (x=0.5m, y=0.25m) | 308.2025mm2 ,Loc. (x=0.75m, y=0.5m) | 15231.88mm2 | 0.68% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).