Submitted:

06 June 2023

Posted:

07 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

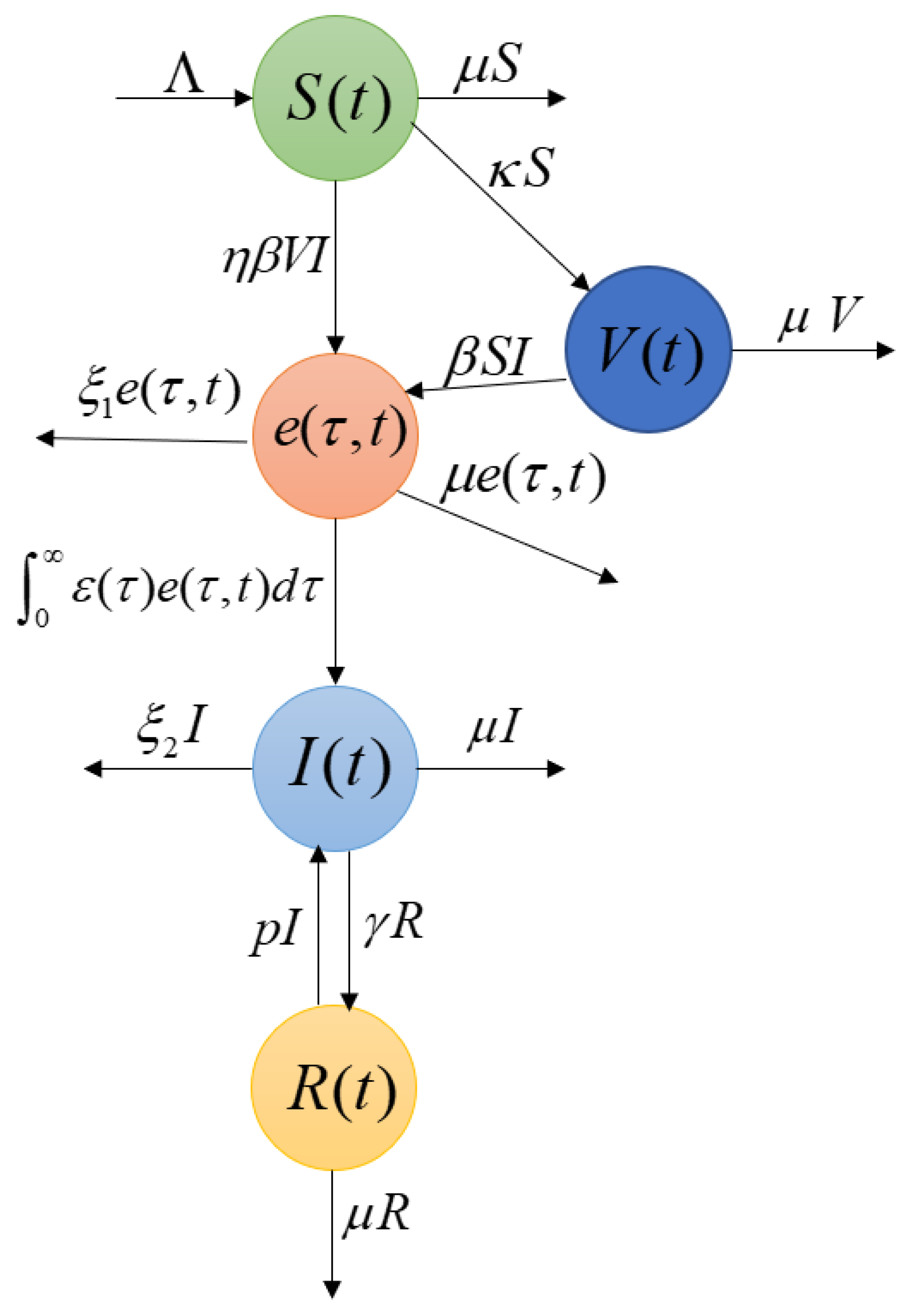

2. Mathematical Model and the Existence of Equilibrium Points

2.1. Mathematical Model

2.2. The Existence of Equilibrium Points

3. Preliminary Results

3.1. The Semi-Flow

3.2. Asymptotic Smoothness

3.3. Uniform Persistence

4. Stability Analysis of the Equilibrium States

4.1. Global Stability of the Disease-free Equilibrium State

4.2. Global Stability of the Endemic Equilibrium State

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kermark, W.O.; Mckendrick, A.G. A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. 1927, 115, 700–721. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Y.; Yang, Y.L.; Zhou, Y.C. Global stability of an epidemic model with latent stage and vaccination. Nonlinear Analysis: Real World Applications. 2011, 12, 2163–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Huang, G.; Takeuchi, Y.; Liu, S. SVEIR epidemiological model with varying infectivity and distributed delays. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering. 2011, 8, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, R.K.; Kumari, S.; Misra, A.K. Modeling the virus dynamics in computer network with SVEIR model and nonlinear incident rate. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Computing. 2017, 54, 485–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Kundu, S.; Tripathi, J.P.; Bugalia, S. Stability and Hopf bifurcation analysis of an SVEIR epidemic model with vaccination and multiple time delays. Chaos, Solitons and Fractals. 2020, 131, 109483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Chavez, C.; Song, B. Dynamical models of tuberculosis and their applications. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering. 2004, 1, 361–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Ruan, S.G.; Zhang, W.N. An age-structured model for the transmission dynamics of hepatitis B. SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics. 2010, 70, 3121–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumel, A.B.; McCluskey, C.C.; Watmough, J. An SVEIR Model for Assessing Potential Impact of an Imperfect Anti-Sars Vaccine. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering. 2006, 3, 485–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumel, A.B.; McCluskey, C.C.; van den Driessche, P. Mathematical study of a staged progression HIV model with imperfect vaccine. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 2016, 68, 2105–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röst, G. SEIR epidemiological model with varying infectivity and infinite delay. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering. 2008, 5, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, J.; Lowrie, D.; Williams, J. An age-structured model for the AIDS epidemic. European Journal of Operational Research. 2000, 124, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magal, P.; McCluskey, C.C.; Webb, G.F. Lyapunov functional and global asymptotic stability for an infection-age model. Applicable Analysis. 2010, 89, 1109–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, H.; Sekine, H. A mathematical model for Chagas disease with infection-age-dependent infectivity. Mathematical Biosciences. 2004, 190, 39–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebenman, B. Niche differences between age classes and intraspecific competition in age-structured populations. Journal of theoretical biology. 1987, 124, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.K.; Xiang, H.; Huo, H.F. Analysis of an age-structured tuberculosis model with treatment and relapse. Journal of Mathematical Biology. 2021, 82, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R. Global dynamics of an epidemiological model with age of infection and disease relapse. Journal of Biological Dynamics. 2018, 12, 118–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magal, P.; Zhao, X.Q. Global attractors and steady states for uniformly persistent dynamical systems. SIAM journal on mathematical analysis. 2005, 37, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, C.J.; Plyugin, S.S. Global analysis of age-structured within-host virus model. Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems Series B. 2013, 18, 1999–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenne, C.; Mophou, G.; Dorville, R.; Zongo, P. A model for brucellosis disease incorporating age of infection and waning immunity. Mathematics. 2022, 10, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, J. Global dynamics of an SEIR model with the age of infection and vaccination. Mathematics. 2021, 9, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Hu, L.; Nie, L.F. Dynamics of a hybrid HIV/AIDS model with age-structured, self-protection and media coverage. Mathematics. 2023, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.R.; Zhou, N. Controllability and stabilization of a nonlinear hierarchical age-structured competing system. Electronic Journal of Differential Equations. 2020, 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Liu, X.N. Global stability of an age-structured SVEIR epidemic model with waning immunity, latency and relapse. International Journal of Biomathematics. 2017, 10, 1750038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, H.F.; Yang, P.H.; Xiang, H. Dynamics for an SIRS epidemic model with infection age and relapse on a scale-free network. Journal of the Franklin Institute-Engineering and Applied Mathematics 2019, 356, 7411–7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Zaman, G. Optimal control strategy of SEIR endemic model with continuous age-structure in the exposed and infectious classes. Optimal Control Applications and Methods. 2018, 39, 1716–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, O.; Heesterbeek, J.A.P.; Metz, J.A. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. Journal of mathematical biology. 1990, 28, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.K. Functional Differential Equations. Analytic Theory of Differential Equations: The Proceedings of the Conference at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, from 30 April to 2 May 1970. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1970, 9-22.

- Hale, J.K.; Waltman, P. Persistence in infinite-dimensional systems. SIAM Journal on Mathematical Analysis. 1989, 20, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.A.; Fournier, J.J. Sobolev Space. Academic Press. New York. 2003, pp.38-40.

- McCluskey, C.C. Global stability for an SEI epidemiological model with continuous age-structure in the exposed and infectious classes. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering. 2005, 9, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magal, P. Compact attractors for time-periodic age-structured population models. Electronic Journal of Differential Equations. 2001, 2001, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).