1.1. Background of the Study

Pakistan is primarily an agricultural country. However, since 2013, Pakistan has been a net food importer, resulting in an additional burden of US$4.261 billion in the first nine months of fiscal year 2019 (PES 2018-19). Furthermore, agriculture's contribution to GDP has been decreasing over time. In comparison to the output levels of advanced countries throughout the world, Pakistan's average crop yield is extremely low. Agricultural research is required to overcome the sector's backwardness, as it shifts the focus of agricultural research to modern lines for integrated, sustainable, and profitable farming in order to improve productivity, nutrition, the environment, and people's lives. Innovations through research and development are possible only through effective use of knowledge. Knowledge hiding, as a prevalent workplace problem results in significant financial losses for businesses (Zhao et al., 2016). Despite the well-established requirement for knowledge sharing, Connelly et al. (2012) found that knowledge hiding is common in many service firms, preventing knowledge transfer (Connelly et al., 2012). Among other factors, knowledge hiding among research professional may be the reason for poor performance of agricultural research institutes in Pakistan.

Knowledge management in contemporary organizations is a crucial and vital resource for competitive advantage and success (Alnaimi et al., 2022). Although, employees possesses the knowledge (Abubakar et al., 2019a), the capacity to share it is the central concern for contemporary organizations’ knowledge management success. Organizations frequently spend a lot of time and money on learning new knowledge (Zhao et al., 2019) for maintaining their competitive advantage, still the disinclination towards knowledge sharing exists and employees continue to be hesitant for sharing knowledge with coworkers (Pradhan et al., 2019). When critical knowledge or information is kept hidden, it have serious consequences for organizations, ranging from negative consequences for employees (Cerne et al., 2014), project-level concerns to larger organizational inefficiencies (Keil et al. 2014). Babcock (2004) found that knowledge hiding costs Fortune 500 organizations roughly $31.5 billion each year. Furthermore, in 2006, the Globe and Mail surveyed more than 1,700 regular readers; their study showed that roughly 76 percent workers were engaged in knowledge hiding behavior (Farooq and Sultana, 2021). In his study, Peng (2013) discovered that 46% of respondents admitted who engaged at least once, in knowledge hiding behavior. It is therefore critical to discover the factors that cause individuals (particularly research professionals) to hide their knowledge so that firms may design effective tactics to discourage this behavior. Few researches have been performed to ascertain the scope of knowledge hiding because the concept of hiding knowledge is still developing (Connelly et al., 2012; Issac and Baral, 2021).

The word "knowledge hiding" was originally used by Connelly et al. (2012), they thought it was a deliberate attempt by someone to withhold or conceal knowledge that someone else had asked for. This is a three-dimensional phenomenon i-e evasive knowledge hiding, playing dumb and rationalized knowledge hiding approaches. Connelly and Zweig (2015) stated that evasive hiding occurs when workers ‘give wrong information and promise to provide complete information later on’. In playing dumb the workers pretend that he don’t have the required information as requested and rationalized knowledge hiding occurs when workers ‘provide a justification, blame someone else or say that he is not allowed to disclose or transfer such information by superiors. Studies in area of knowledge hiding have begun two decades ago to understand why people hide knowledge (Ghobadi, 2015). If some fear loss of their power (Ulrike et al., 2005), others fear of being evaluated (Bordia et al., 2006). Some others may find knowledge to be complex when shared and others maybe waiting for the right climate in their organization (Connelly et al., 2012). Peng (2013) found that knowledge hiding is because of influence by territoriality concerns. Further Connelly et al., (2012) argues that if an employee distrusts the requestor, or if the question is complicated then the employees engage in knowledge hiding. Furthermore, Knowledge hiding occurs, owing to employees' fear of losing their status, career chances, or even jobs (Jha and Varkkey, 2018). Though, organizations attempt to discover strategies to incentivize persons to share their expertise with their coworkers because it is a deliberate activity (Men et al., 2018), they cannot, however, be pressured against their choice for sharing their knowledge (Kelloway and Barling, 2000); nonetheless, they may (and should) be urged and encouraged to do so. According to Pereira and Mohiya (2021), scholarship in the context of ‘knowledge hiding’ as a concept is in very nascent stage and thus there is a need to explore the concept in varied contexts and in relation with other organizational constructs in order to enhance the theoretical legitimately of the construct. All the identified themes are evolving in terms of its density and lesser in terms of its centrality, and thus we suggest knowledge hiding attracts greater scholarly attention, as an organizational construct.

Prior research on knowledge hiding denotes a number of predictors such as interpersonal distrust (Černe et al., 2014), organizational injustice (Abubakar et al., 2019b), and leadership related factors (Khalid et al., 2018; Men et al., 2018; Xia et al., 2019; Anser et al., 2020; Ghani, 2020) to measure knowledge hiding behavior, however, less attention has been paid how to mitigate knowledge hiding behavior. Knowledge hiding is influenced by a wide range of contextual factors, including organizational policies, compensation systems, leadership, structure, and culture, among others, according to Connelly et al. (2012), they further advocated additional research in order to investigate and comprehend causes and effects of "knowledge hiding" behaviors. One significant factor that impacts a person's behavior for knowledge sharing to others at work is the social interactions between coworkers and leadership and how one is treated while working. Oliveira et al. (2021) found after a comprehensive literature analysis on knowledge hiding that organizational values and leadership style most likely impact the adoption of the behaviors, therefore the relationship between these should be investigated. Oh and Wang, (2020) believed that spiritual leadership is a unique and researchable topic and urge further study to increase the breadth and depth of the field's knowledge. Spiritual leadership may impair employees' knowledge-hiding tendencies, which could make for a fascinating research topic for scholars in the future (Anser et al, 2021).

Spiritual leadership, as a form of value-based leadership, has grown in favor recently due to its ability to have a good effect on businesses. Spiritual leaders prioritize encouraging staff to uphold the organization's mission and values by offering assistance, expressing gratitude, and creating a feeling of community (Fry 2003). Research on spiritual leadership is becoming more popular (Dinh et al. 2014). Under spiritual leadership through a transcendent vision coupled with hope and altruistic love, employees are intrinsically motivated to foster positive social emotions such as care and concern for others, compassion, kindness, forgiveness, gratitude, and helping (Fry, 2003; Fry et al., 2005), which are the fundamental building blocks of establishing and maintaining trust-based interpersonal relationships (Bayighomog and Arasl, 2019). Employees that have strong, trust-based connections with one another tend to be less knowledge-hibernating. Additionally, by combining the use of ethical/spiritual ideals with rational criteria in decision-making, spiritual leadership empowers staff to control their behavior and make morally superior decisions (Fry et al., 2005).

Spiritual leadership becomes one of the factors that can influence knowledge hiding behavior; however, it needs other variables such as professional commitment that can be the bridging variable between spiritual leadership and knowledge behavior. Ghani et al. (2020) studied the relationship between professional commitment and knowledge hiding among students and found a negative relationship. In a study, Men et al. (2018) discovered a negative link between knowledge hiding and ethical leadership and further suggested investigating professional commitment as potential antecedent of knowledge hiding behavior. Moreover, Rumangkit, (2020) examined the direct association between spiritual leadership and affective professional commitment with perceived organizational support as a mediator, and discovered a favorable relationship between the two. Furthermore, Connelly et al. (2012) indicated that employees with high levels of professional commitment are less likely to hide knowledge, because they view responding to coworkers’ requests as their professional responsibility. Therefore, even when working in a politically charged workplace, people with a high level of professional dedication are less likely to participate in information hiding practices (Malik et al,. 2019).

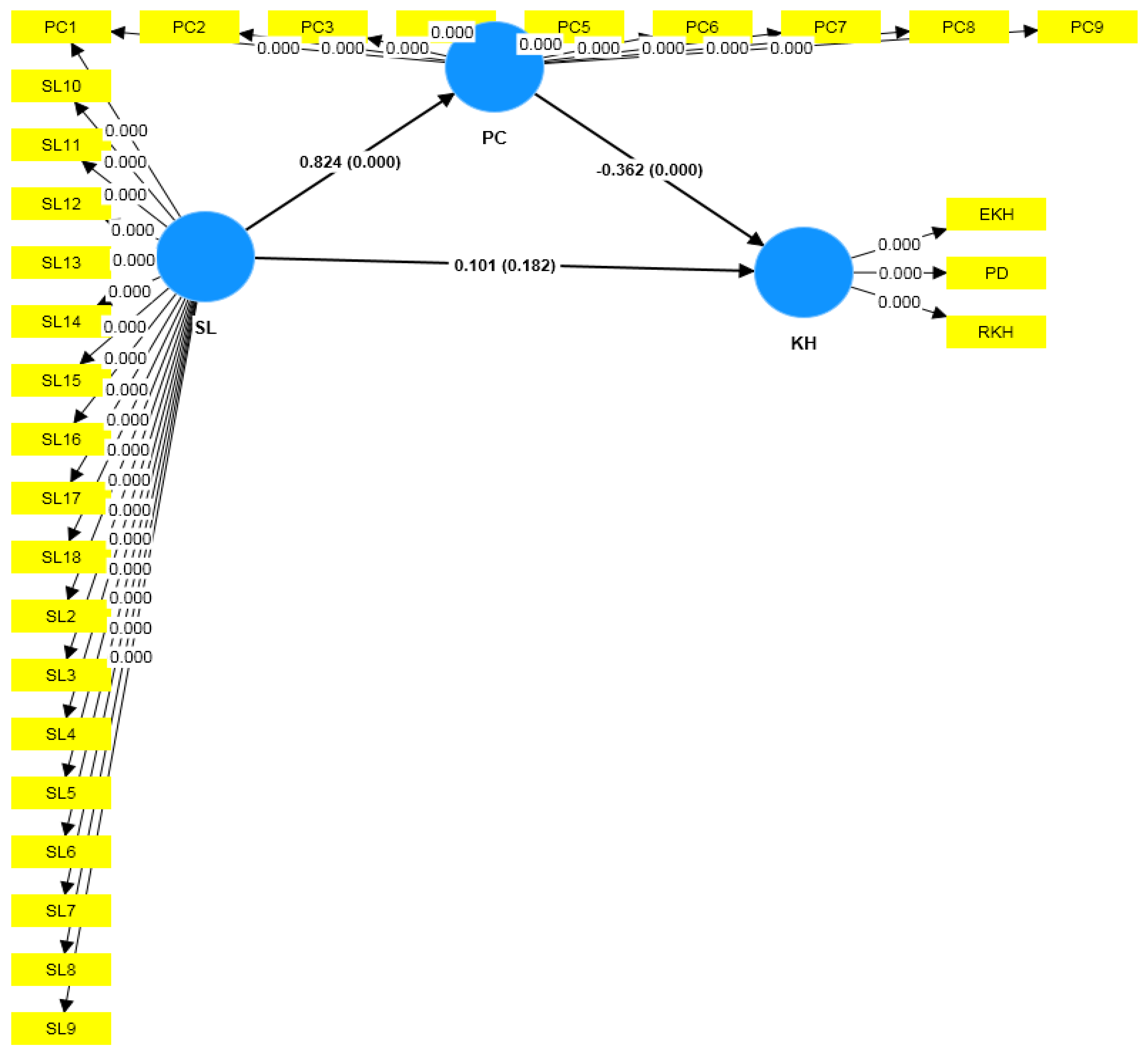

Based on the views and opinions of some of the aforementioned writers, we assume that spiritual leadership has a relationship with knowledge hiding behavior mediated by professional commitment. The purpose of this study is to analyze the relationship between spiritual leadership, professional commitment and its implication to knowledge hiding behavior. Based on previous theoretical and research approaches, this research investigates the relationship between spiritual leadership (as exogenous variable) with professional commitment (as intervening variable) and knowledge hiding behavior (as endogenous variable). This study uses the spiritual leadership theory (SLT) developed by Fry (2003) and social action theory to become the basis for the investigation. Spiritual leadership theory and social action theory which states that when leaders can channel personal values to other individuals as intrinsic motivation, individuals will try to bind themselves to organizations with high involvement and try to have an emotional attachment to the leader and organization (Kanter, 1968). The study also analyzes the effect of spiritual leadership on subordinate’s knowledge hiding behavior using social exchange theory as the theoretical foundation to support our hypothesis. Relationships between individuals depend on positive and useful exchanges and transactions, which is one of the fundamental principles of SET. When an employee realizes and experiences knowledge hiding, he/she is prone to retaliate as stated by norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960) and this induces distrust in coworkers. This in turn leads to ineffective social exchange between them (Blau, 1964).

The study makes significant contributions to the realm of spiritual leadership and knowledge hiding literature. First, it investigates empirically the relationship between knowledge hiding behaviors among employees and spiritual leadership. Second, the study investigates the indirect relationship between knowledge hiding and spiritual leadership and uses professional commitment as potential mediator that may explain this link. This study is unique in that it combines perceptions of professional commitment as a mediator of spiritual leadership and knowledge hiding behavior, two aspects that are rarely investigated together. The study has some important implications for research officers, management, and research assistants of the agriculture research institutes of KPK, Pakistan. It will make clear that the phenomena of knowledge hiding at work is at its height in organizations right now and has caught the attention of researchers from around the world. Decision makers must train and evaluate the leadership and supervisors to adopt the values and practices of value based leaderships to motivate their employees share critical knowledge and benefit their organizations.