1. Introduction

Oxysterols are oxygenated derivatives of cholesterol with a multitude of biological activities (1, 2). These sterols are detected in the serum at very low concentrations as compared to cholesterol (2). Concerning about cardiovascular diseases (CVD), they have been found enriched in atherosclerotic lesion, and their roles in the etiology of cardiovascular diseases has been studied (2). Furthermore, preclinical and clinical studies suggest that oxysterols are implicated in the pathogenesis of many health conditions, including liver disease (3), neurodegenerative disease (4), eye disorder (5), cancer (6), diabetes (7), and infectious disease (8). They can be produced endogenously by autoxidation and/or enzymatic reactions (1), or provided by food.

Apart from serum lipids levels, alterations in cholesterol metabolism may affect the risk of CVD (9). Cholesterol in diet is absorbed from the intestine through Niemann-pick C1-like 1, an intestinal cholesterol transporter (10), which is blocked by ezetimibe. In clinical settings, cholesterol absorption can be assessed by measuring the serum level of plant sterols such as campesterol (11), which is not synthesized in humans. Besides dietary cholesterol intake, the liver synthesizes cholesterol. Cholesterol synthesis can be assessed by measuring serum levels of lathosterol, a precursor of cholesterol (11).

Previous studies showed that high cholesterol absorbers had higher CVD risk (12, 13). We recently conducted the CuVIC trial (Effect of Cholesterol Absorption Inhibior Usage on Target Vessel Dysfunction After Coronary Stenting), in which ezetimibe in combination with statin ameliorated coronary endothelial dysfunction (CED) associated with reduced oxysterol levels in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) after coronary stenting (14). We demonstrated that: 1) the incidence of coronary endothelial dysfunction associated with not only serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels, but also total oxysterol levels; 2) ezetimibe in combination with statin ameliorated serum levels of campesterol and total oxysterol compared to statin monotherapy. On the other hand, serum levels of several oxysterols, including 24S-hydroxycholesterol and 27-hydroxycholesterol, were reported to positively correlate with markers of cholesterol synthesis, such as serum levels of lathosterol and desmosterol (15). Another study reported that treatment with statin monotherapy reduced serum levels of oxysterols and decreased cholesterol synthesis markers (16). These studies suggested that serum levels of oxysterols could be positively correlated with cholesterol absorption and synthesis markers. However, the comprehensive associations of individual oxysterols with either cholesterol absorption or synthesis, or both, are largely unknown, especially among patients with CAD. Moreover, the clinical factors that may affect the cholesterol metabolism and serum oxysterols remain to be elucidated.

In the present study, a sub-analysis of the CuVIC trial, we employed a covariance structure analysis to explore the associations between clinical factors with cholesterol absorption and synthesis, and their associations with serum oxysterols in the patients with CAD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Design

The present study is a post-hoc analysis of the CuVIC trial (14). The design of the CuVIC main study has been described previously. Briefly, 260 patients with coronary artery disease who underwent coronary stenting at 11 cardiovascular centers were randomly allocated into two arms [statin monotherapy vs. ezetimibe 10 mg/day + statin combination therapy] in the period 2011-2013. In both treatment groups, we set the target LDL-C value at 100 mg/dL or less. Participating physicians were allowed to titrate statin doses to achieve that goal. The primary endpoint of the main study was target vessel dysfunction defined as the composite of target vessel failure during the follow-up period of 6-8 months and CED determined by intracoronary injection of acetylcholine at the follow-up coronary angiography (CAG). Exclusion criteria included: a planned coronary revascularization procedure, participation in another clinical trial interfering with this study, end-stage renal failure and on hemodialysis, liver cirrhosis, severe left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction < 30%), or contraindication for statins or ezetimibe. Among those patients, we enrolled 207 patients for whom serum oxysterols data measured at baseline were available in this sub-study.

2.2. Biomarker Assessment

Blood samples were collected at the baseline of the CuVIC Trial. LDL-C levels were calculated via the Friedewald equation. In addition to routine laboratory tests, including lipid profiling at each participating center, samples were transferred to Medical and Biological Laboratories, Co., LTD., Nagoya, Japan, where they were measured for apolipoprotein A1(Apo A1), apolipoprotein B (Apo B), high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and malondialdehyde modified LDL (MDA-LDL) levels. The non-cholesterol sterols (campesterol, sitosterol, and lathosterol) were measured at SRL, Inc., Tokyo, Japan, using gas chromatography (GC-2010, Shimadzu, Co., Kyoto, Japan). Oxysterols were quantified using gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC/MS QP2010; Shimadzu Co.) equipped with an SPB-1 fused silica capillary column (60 m×0.25 mm, 0.25 μm phase thickness; Supelco Inc., Bellefonte, PA, USA). Participants reported general demographic and health information at the time of enrollment, including sex, age, height, weight, smoking status, history of metabolic syndrome, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and use of common prescription medications such as statins, antihypertensive drugs, drugs to control diabetes, and insulin.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as medians and ranges or interquartile ranges (IQR), and categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Categorical variables were analyzes using a χ2 test, and variables were analyzed using a Student’s t-test or an analysis of covariance. The correlation between two factors was expressed as Spearman’s correlation. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to estimate the association between the serum levels of oxysterols, cholesterol synthesis/absorption and clinical factors. Firstly, we divided subjects into two groups based on the median value of campesterol, and a Student’s t-test was performed. We conducted a similar analysis using lathosterol. The purpose of creating a path diagram was to verify the following two hypotheses: Firstly, various oxysterols are regulated by two latent variables, “cholesterol absorption” and “cholesterol synthesis”. Secondly, these two latent variables are influenced by several clinical factors. We performed covariance structure analysis using the latent variables for oxysterols. To evaluate the method fit, we used the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Statistical analysis was performed using the JMP software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The SEM analyses was performed using a statistical software package IBM SPSS AMOS version 25 (Amos Development Corporation, Meadville, PA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

All subjects underwent successful percutaneous coronary intervention. The clinical and biochemical data suggest that this cohort showed normal body weight and BMI. Median [IQR] concentration of total cholesterol and LDL-C was 162 [139, 196] mg/dL and 92 [73, 118] mg/dL, respectively. Median concentrations of triglyceride and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were within the reference range. Statin was prescribed to 131 patients (62%). Median concentration of campesterol, sitosterol and lathosterol was 3.5 [2.7, 4.7] μg/mL, 1.7 [1.3, 2.5] μg /dL and 1.0 [1, 1.2] μg /dL, respectively. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia was 36%, 71%, 47% and 89%, respectively (

Table 1,

Figure 2).

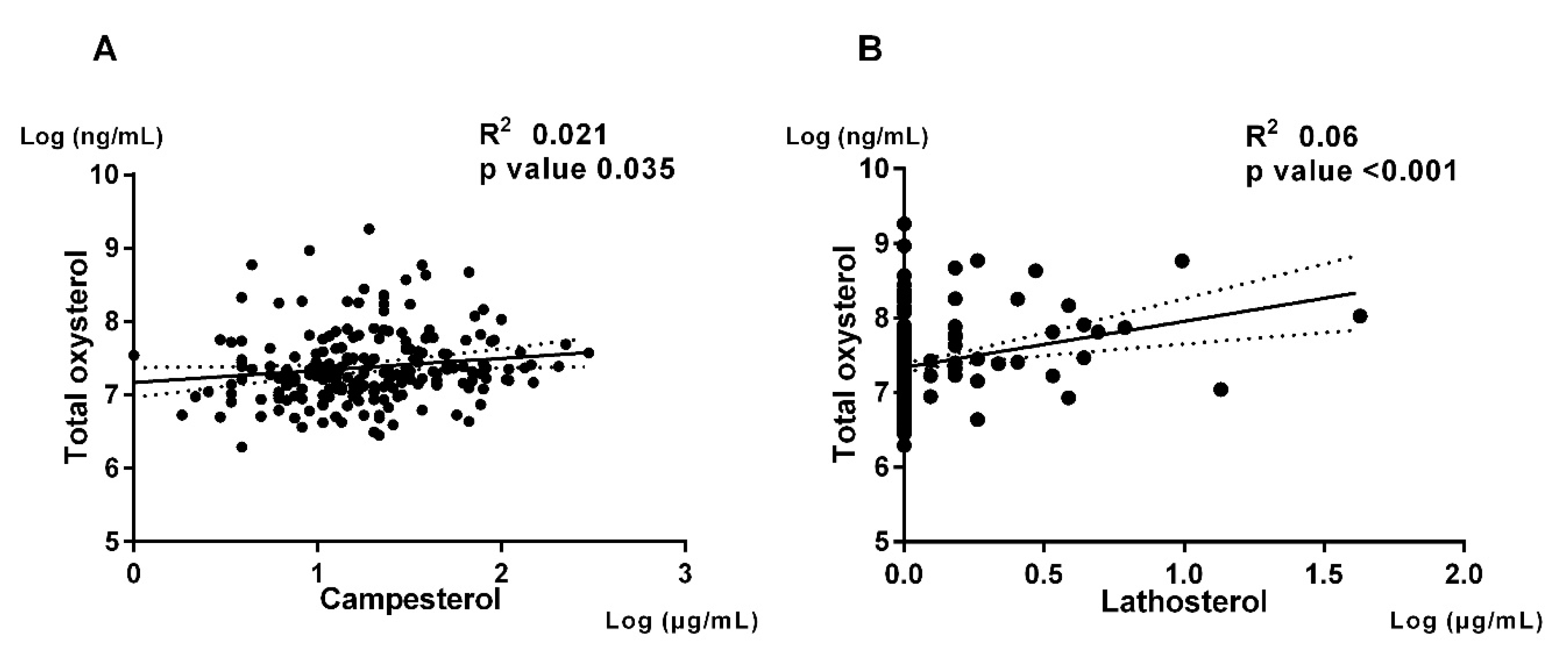

The correlation of total oxysterol level and cholesterol metabolism biomarkers were shown. Panel A (Left) shows regression line of total oxysterol and campesterol. Panel B (Right) shows regression line of total oxysterol and lathosterol.

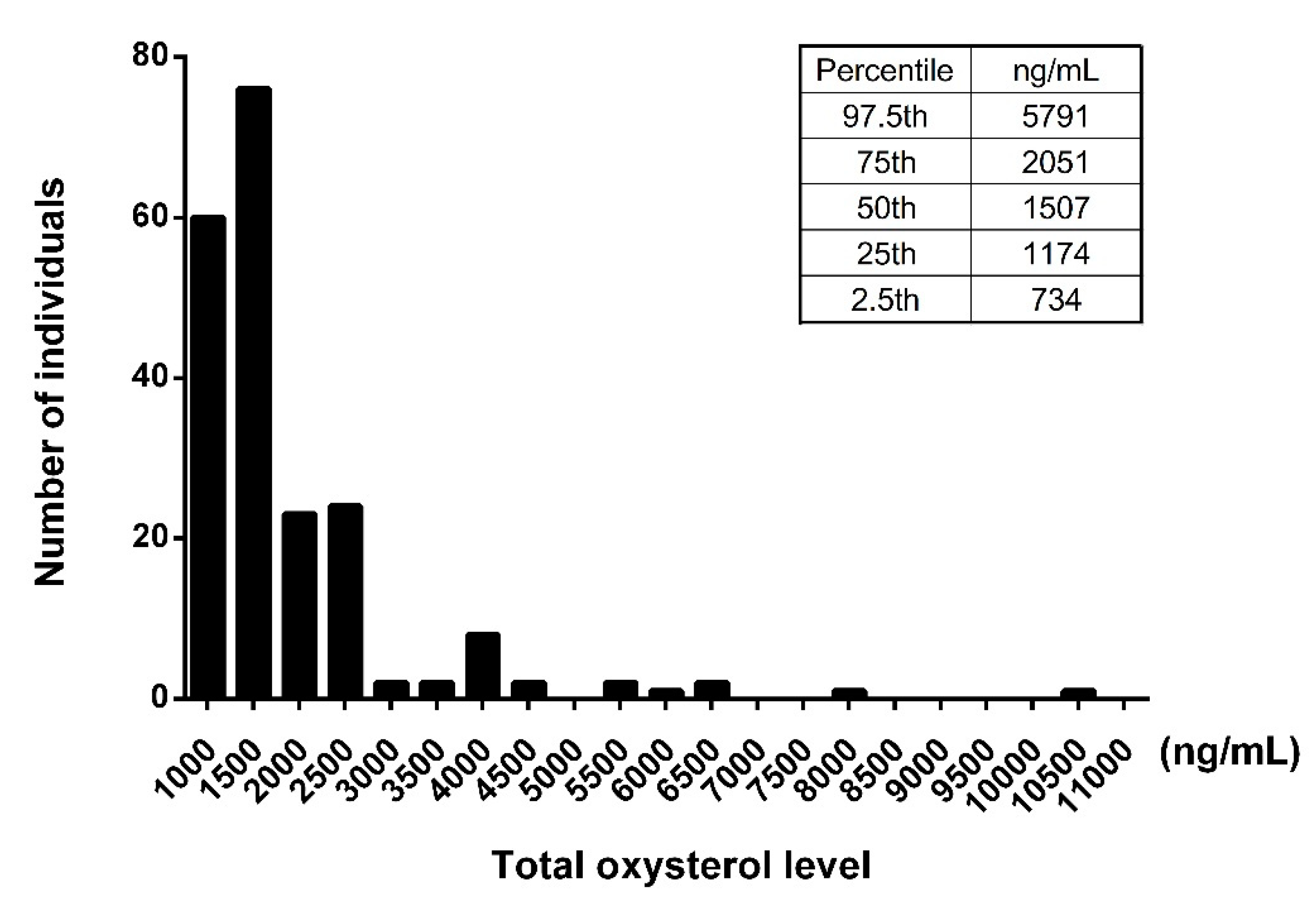

3.2. Analysis of Oxysterols in the Study Population

We examined serum levels of oxysterols in the study population. The value of the serum total oxysterol was 1,507 [1,174-2,036] ng/mL. The 7-ketocholesterol values (323 [215-582] ng/mL) accounted for the majority of dietary oxysterols, which include β-epoxycholesterol (β-EPOXY), cholestan-3β,5α,6β-triol (TRIOL), 7β-hydroxycholesterol and 7-ketocholesterol. The 27-hydroxycholesterol values (401 [323-489] ng/mL) accounted for the majority of intrinsic oxysterols, which include 4β-hydroxycholesterol, 24-hydroxycholesterol, and 27-hydroxycholesterol. The 7α-hydroxycholesterol values (152 [106-267] ng/mL) accounted for the majority of dietary and intrinsic oxysterols, which include 7α-hydroxycholesterol and 25-hydroxycholesterol (

Table 1). The histogram of concentration of total oxysterol showed modestly right skewed distributions (

Figure 1).

3.3. Association of Oxysterols with Cholesterol Absorption and Synthesis

Previous studies suggested that oxysterols in peripheral blood could be positively correlated with cholesterol absorption and synthesis (12, 13, 14, 15, 16). We then investigated the association between the serum level of total oxysterol and cholesterol metabolism biomarkers. The serum level of total oxysterol was positively associated with the cholesterol metabolism biomarkers such as campesterol (spearman R

2=0.021, p=0.035) and lathosterol (spearman R

2=0.06, p<0.001) (

Figure 2).

3.4. Association of Cholesterol Absorption and Synthesis with Clinical and Biochemical Characteristics

To investigate the oxysterols that correlate with cholesterol absorption and/or synthesis markers, we divided this study population into two subgroups based on the median value of campesterol (3.5 μg/mL) and lathosterol (1.0 μg/mL), respectively. Total cholesterol, HDL-C and LDL-C were significantly higher in the high campesterol group than low campesterol group in lipid profiles. Also, total oxysterol, TRIOL, 4β-hydroxycholesterol, 7α-hydroxycholesterol, 7β-hydroxycholesterol, 7-ketocholesterol and 24-hydroxycholesterol were significantly higher in the high campesterol group than low campesterol group (

Table 2). By contrast, triglyceride and MDA-LDL were significantly higher in the high lathosterol group than low lathosterol group in lipid profiles. Total oxysterol, β-EPOX, 7α-hydroxycholesterol, 7β-hydroxycholesterol, 7-ketocholesterol, 24-hydroxycholesterol, 25- hydroxycholesterol and 27-hydroxycholesterol were significantly higher in the high lathosterol group than low lathosterol group (

Table 3).

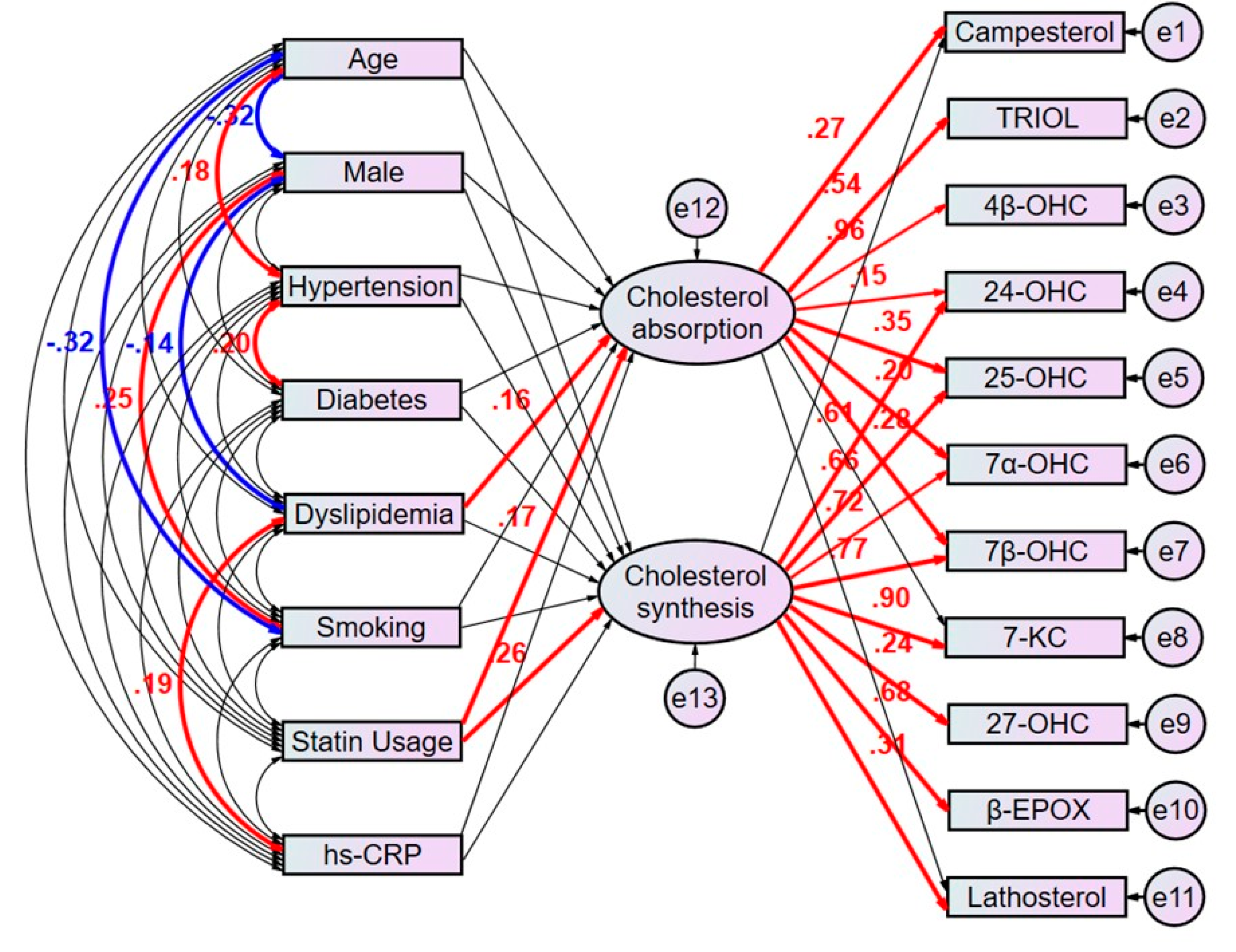

3.5. Path Model Estimated Regression Weights in Oxysterols Revealed Potential Clinical Factors Affecting Cholesterol Metabolism Markers

The multivariate analyses would not be enough to identify clinical factors that predict the patients with high cholesterol absorption or synthesis because the factors confound each other, and it is challenging to make up the characteristics of each clinical factors explicit using the respective equation model. We then employed the proposed path model to compensate the confounding factors (

Figure 3). In brief, the clinical factors potentially confound each other; the association between two factors is linked by the bidirectional arrows. Statistically insignificant paths are drawn as thin arrows. Paths between variables are drawn from independent to dependent variables, with a directional arrow for every regression model, namely from age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, statin usage, and hs-CRP to the latent variable “cholesterol absorption” and to the other latent variable “cholesterol synthesis”. Furthermore, directional arrows were drawn between each latent variable and each oxysterol positively correlated with cholesterol metabolism markers (

Table 2,

Table 3). The proposed path model revealed dyslipidemia (β [standardized regression coefficient]:0.163, p=0.028) and statin usage (β:0.175, p=0.017) showed a positive correlation with the latent variable “cholesterol absorption”, which shows a significant correlation with campesterol (β:0.273, p<0.001). In consistent with the ratio of male to female patients with dyslipidemia in Japan (17), dyslipidemia negatively correlated with male sex (β:-0.14, p=0.041). Also, it positively correlated with high sensitivity CRP (β:0.19, p=0.016).

On the other hand, statin usage (β:0.261, p<0.001) showed a positive correlation with the other latent variable “cholesterol synthesis”, which shows a significant correlation with lathosterol (β:0.312, p<0.001). (

Figure 3, Supplementary Table S1).

This path has a coefficient showing the standardized coefficient of regressing independent variables on the dependent variable of the relevant path.

These variables indicate standardized regression coefficients (direct effect) [bold capitals]. A two-way arrow between two variables indicates a correlation between those two variables. The total variance in a dependent variable for every regression is theorized to be caused by either independent variables of the model or extraneous variables.

3.6. Path Model Revealed the Associations between Individual Oxysterols and Latent Cholesterol Absorption and Synthesis

The proposed path model also revealed the associations between individual oxysterols and latent variables of cholesterol absorption and synthesis. Among the oxysterols, TRIOL (β:0.542, p<0.001) and 4β-hydroxycholesterol (β:0.958, p<0.001) were positively regulated by “cholesterol absorption”. 7-ketocholesterol (β:0.897, p<0.001), 27-hydroxycholesterol (β:0.236, p<0.001) and β-EPOX (β:0.678, p<0.001) were positively regulated by “cholesterol synthesis”. 24-hydroxycholesterol (β:0.153, p=0.019 and β:0.609, p<0.001), 25-hydroxycholesterol (β:0.355, p<0.001 and β:0.665, p<0.001), 7α-hydroxycholesterol (β:0.196, p<0.002 and β:0.72, p<0.001) and 7β-hydroxycholesterol (β:0.277, p<0.001 and β:0.775, p<0.001) were positively regulated by both cholesterol absorption and synthesis. Based on the result of this path analysis, it was noted that oxysterols may be regulated via distinct mechanisms.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the potential clinical factors that may affect cholesterol metabolism, and the association between various oxysterols with cholesterol absorption and/or synthesis in the patients with coronary artery disease. The key findings include:1) serum total oxysterol level showed significant positive correlations with both campesterol and lathosterol, which are markers of cholesterol absorption and synthesis; 2) The proposed path model revealed the latent variable “cholesterol absorption” that was associated with dyslipidemia and statin usage positively regulated campesterol and the latent variable “cholesterol synthesis” that is associated with statin usage positively regulated lathosterol; 3) Among the oxysterols, TRIOL and 4β-hydroxycholesterol were positively regulated by the latent “cholesterol absorption”. 7-ketocholesterol, 27-hydroxycholesterol and β-EPOX were positively regulated by the latent “cholesterol synthesis”. 24-hydroxycholesterol, 25-hydroxycholesterol, 7α-hydroxycholesterol and 7β-hydroxycholesterol were positively regulated by both of these latent variables.

Most of oxysterols values in our study in patients with CAD were found to be higher than the range previously reported for different healthy population (16). Especially the values of 7-ketocholesterol and 27-hydroxycholesterol were more than 2-fold higher compared to those reported previously (range for 7-ketocholesterol 10.7-98.0 ng/mL and 27-hydroxycholesterol 43.6-196.0 ng/mL, respectively). In contrast, 24-hydroxycholesterol and 25-hydroxycholesterol values in this population were within the previously reported range (16). The 7-ketocholesterol is one of the most common dietary oxysterols and abundantly presented in human atherosclerotic lesions (2). We previously demonstrated in animal studies that 7-ketocholesterol possesses proinflammatory properties in vascular cells, such as promoting endothelial cell proliferation and tissue factor expression in smooth muscle cells (18). Furthermore, 7-ketocholesterol induce monocyte/macrophage mediated inflammation in myocardial infarction by inducing endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (19). Umetani et al. found that 27-hydroxycholesterol promoted atherosclerosis via proinflammatory processes mediated by estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), and this oxysterol attenuated estrogen-related atheroprotection (20). 27-hydroxycholesterol, the major oxysterol in serum and atheroma lesions, is generated enzymatically from cholesterol in several tissues, including atheroma lesions in direct relation to serum levels (2). This study included CAD patients who are assumed more prevalent to progressive atherosclerosis. In this respect, a possible mechanism by which advanced level of systemic atherosclerosis might cause the elevation of serum oxysterols level.

Stiles et al. reported that circulating 4β-hydroxycholesterol could be influenced by diet based on an observed positive correlation with serum concentrations of plant sterols (21). Consistently, serum level of total oxysterol was correlated with both of campesterol and lathosterol. We further found that campesterol and lathosterol were correlated with individual levels of different lipids and oxysterols, suggesting potential shared metabolic pathways. In general, circulating oxysterols are positively correlated with serum total cholesterol, triglycerides and LDL- cholesterol, and negatively correlated with HDL-cholesterol (21). Most serum oxysterols are found in the LDL-C and HDL-C fractions (22), suggesting that oxysterols are transported in serum with cholesterols. Common origins may explain numerous positive correlations, such as those between most sterols and cholesterols. These correlations may reflect cotransport in serum lipoprotein particles (22). Additionally, positive correlations can be observed between plant sterols, such as sitosterol and campesterol, which can be attributed to their dietary origin, as well as their absorption and excretion via ABCG5/ABCG8 (23).

We elucidated the associations between clinical factors and cholesterol metabolism, and then those between cholesterol metabolism and various oxysterols using the cutting-edge path model. To the best of our knowledge, there were no reports that evaluated these associations using a covariance structure analysis. In this analysis, statin usage not only positively correlated with “cholesterol absorption”, but also with “cholesterol synthesis”, contrary to some previous reports that demonstrated reductions in circulating oxysterols even with short-term statin treatment (24, 25). The reason for this discrepancy could be that the subjects in this study were hypercholesterolemic patients with elevated cholesterol synthesis, which led to a statin usage. Dyslipidemia, which was positively correlated with cholesterol absorption, was also positively correlated with hs-CRP. Emerging evidence suggests that serum oxysterols may associate with systemic inflammation through interaction with receptors other than the LXRs (26, 27). However, we did not find that the hs-CRP as an inflammatory marker associated with serum oxysterols level in this path model although hs-CRP had a positive correlation with dyslipidemia that was positively correlated with “cholesterol absorption”. This may be due to the fact that most of the study population were taking statins. In addition, there is inconsistency as for the link between diabetes and cholesterol absorption in previous studies (28, 29). Matsumura et al. reported that diabetes associated with lower cholesterol absorption independently (30). However, we did not find a correlation between diabetes and cholesterol absorption or synthesis in this study. This suggested that the subjects receiving antidiabetic drugs may have their circulating glucose levels controlled to targets established for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. The path analysis revealed that oxysterols were differently regulated by “cholesterol absorption” alone, “cholesterol synthesis” alone, or both. Oxysterols can be classified based on its origin. Some of the endogenous oxysterols are produced by organ-specific enzyme (i.e., 24- hydroxycholesterol by brain-specific CYP46A1, and 27-hydroxycholesterol by liver-specific CYP27A1) (16). On the other hand, 7β-hydroxycholesterol, 7-ketocholesterol, and β-EPOX can be formed by non-enzymatic reaction, i.e., auto-oxidation (31). Furthermore, 25-hydroxycholesterol and 7α-hydroxycholesterol can also be formed by autooxidation pathways. In the path analysis of this study, the observed correlations for some oxysterols such as 27-hydroxycholesterol and “cholesterol synthesis” were consistent with known metabolic pathways. On the other hand, 7-ketocholesterol, a dominant non-enzymatically derived oxysterol, showed a significant correlation with “cholesterol synthesis” rather than “cholesterol absorption”. This notion agrees with our animal study showing that high cholesterol diet and infusion of angiotensin II that induces oxidative stress increases serum 7-ketocholesterol, which are inhibited by rosuvastatin or ezetimibe monotherapy(18). The path analysis revealed that oxysterols are intricately regulated in vivo through various biological processes and oxidative stress mechanisms beyond their origins.

It is necessary to aware that the cholesterol metabolism affects the serum oxysterols, some of which are atherogenic. We have previously shown that dietary oxysterols accelerate atherosclerotic plaque destabilization in hypercholesterolemic mice, and this acceleration is ameliorated by ezetimibe monotherapy, which is associated with decreases in serum oxysterol levels (32). These findings support the notion that ezetimibe, a cholesterol absorption inhibitor, may possess beneficial anti-atherogenic effects through lowering oxysterols effectively by the different mechanisms with statins. Addition of ezetimibe to statin monotherapy may be a plausible therapeutic strategy to lower oxysterols that positively regulated by both “cholesterol absorption” and “cholesterol synthesis” in the path model.

There are several limitations in this study. First, this study is a cross-sectional study, and longitudinal studies over a long period of time remain to be performed in the future. Second, the CuVIC population was made of data from the patients with coronary diseases and various comorbidities and medications. Therefore, the population differed from common population. On the other hand, the relatively large sample size was one of the strengths of this study that allowed us the analysis to evaluate the association between oxysterols and clinical factors. Statin medications in the study population may have influenced the results of the path analysis.

In conclusion, this study showed the potential clinical factors that may affect cholesterol metabolism, and the association between various oxysterols with cholesterol absorption and/or synthesis using the samples of the CuVIC study. These results might lead to a precision medicine in which we can apply patients with statin or ezetimibe monotherapy or combination of statin and ezetimibe based on individual oxysterol profiles. Further studies are needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying these associations.

Acknowledgments

Yusuke Akiyama, Shunsuke Katsuki and Tetsuya Matoba had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. We appreciate Maki Kimura and Hiroko Watanabe for their excellent data management.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant number JP21H02916 to TM.

Conflicts of Interest

Tetsuya Matoba reported personal fee from Bayer Yakuhin Ltd. and MSD; and research grant from Amgen and Kowa.

References

- Schroepfer GJ, Jr. Oxysterols: modulators of cholesterol metabolism and other processes. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(1):361-554.

- Brown AJ, Jessup W. Oxysterols and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1999;142(1):1-28.

- Serviddio G, Blonda M, Bellanti F, Villani R, Iuliano L, Vendemiale G. Oxysterols and redox signaling in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radic Res. 2013;47(11):881-93.

- Leoni V, Caccia C. Oxysterols as biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases. Chem Phys Lipids. 2011;164(6):515-24.

- Zhang X, Alhasani RH, Zhou X, Reilly J, Zeng Z, Strang N, et al. Oxysterols and retinal degeneration. Br J Pharmacol. 2021;178(16):3205-19.

- Kloudova A, Guengerich FP, Soucek P. The Role of Oxysterols in Human Cancer. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2017;28(7):485-96.

- Samadi A, Gurlek A, Sendur SN, Karahan S, Akbiyik F, Lay I. Oxysterol species: reliable markers of oxidative stress in diabetes mellitus. J Endocrinol Invest. 2019;42(1):7-17.

- Zang R, Case JB, Yutuc E, Ma X, Shen S, Gomez Castro MF, et al. Cholesterol 25-hydroxylase suppresses SARS-CoV-2 replication by blocking membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(50):32105-13.

- Weingartner O, Lutjohann D, Vanmierlo T, Muller S, Gunther L, Herrmann W, et al. Markers of enhanced cholesterol absorption are a strong predictor for cardiovascular diseases in patients without diabetes mellitus. Chem Phys Lipids. 2011;164(6):451-6.

- Altmann SW, Davis HR, Jr., Zhu LJ, Yao X, Hoos LM, Tetzloff G, et al. Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 protein is critical for intestinal cholesterol absorption. Science. 2004;303(5661):1201-4.

- Miettinen TA, Tilvis RS, Kesäniemi YA. Serum plant sterols and cholesterol precursors reflect cholesterol absorption and synthesis in volunteers of a randomly selected male population. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131(1):20-31.

- Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS, Pitkala KH, Miettinen TA. Cholesterol and glucose metabolism and recurrent cardiovascular events among the elderly: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(4):708-14.

- Katsuki S, Matoba T, Akiyama Y, Yoshida H, Kotani K, Fujii H, et al. Association of Serum Levels of Cholesterol Absorption and Synthesis Markers with the Presence of Cardiovascular Disease: The CACHE Study CVD Analysis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2023.

- Takase S, Matoba T, Nakashiro S, Mukai Y, Inoue S, Oi K, et al. Ezetimibe in Combination With Statins Ameliorates Endothelial Dysfunction in Coronary Arteries After Stenting: The CuVIC Trial (Effect of Cholesterol Absorption Inhibitor Usage on Target Vessel Dysfunction After Coronary Stenting), a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(2):350-8.

- Bjorkhem I, Lovgren-Sandblom A, Leoni V, Meaney S, Brodin L, Salveson L, et al. Oxysterols and Parkinson’s disease: evidence that levels of 24S-hydroxycholesterol in cerebrospinal fluid correlates with the duration of the disease. Neurosci Lett. 2013;555:102-5.

- Mutemberezi V, Guillemot-Legris O, Muccioli GG. Oxysterols: From cholesterol metabolites to key mediators. Prog Lipid Res. 2016;64:152-69.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. National Health and Nutrition Survey.2019.

- Honda K, Matoba T, Antoku Y, Koga JI, Ichi I, Nakano K, et al. Lipid-Lowering Therapy With Ezetimibe Decreases Spontaneous Atherothrombotic Occlusions in a Rabbit Model of Plaque Erosion: A Role of Serum Oxysterols. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38(4):757-71.

- Uchikawa T, Matoba T, Kawahara T, Baba I, Katsuki S, Koga JI, et al. Dietary 7-ketocholesterol exacerbates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice through monocyte/macrophage-mediated inflammation. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):14902.

- Umetani M, Ghosh P, Ishikawa T, Umetani J, Ahmed M, Mineo C, et al. The cholesterol metabolite 27-hydroxycholesterol promotes atherosclerosis via proinflammatory processes mediated by estrogen receptor alpha. Cell Metab. 2014;20(1):172-82.

- Stiles AR, Kozlitina J, Thompson BM, McDonald JG, King KS, Russell DW. Genetic, anatomic, and clinical determinants of human serum sterol and vitamin D levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(38):E4006-14.

- Babiker A, Diczfalusy U. Transport of side-chain oxidized oxysterols in the human circulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1392(2-3):333-9.

- Berge KE, von Bergmann K, Lutjohann D, Guerra R, Grundy SM, Hobbs HH, et al. Heritability of plasma noncholesterol sterols and relationship to DNA sequence polymorphism in ABCG5 and ABCG8. Journal of Lipid Research. 2002;43(3):486-94.

- Locatelli S, Lutjohann D, Schmidt HH, Otto C, Beisiegel U, von Bergmann K. Reduction of plasma 24S-hydroxycholesterol (cerebrosterol) levels using high-dosage simvastatin in patients with hypercholesterolemia: evidence that simvastatin affects cholesterol metabolism in the human brain. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(2):213-6.

- Dias IHK, Milic I, Lip GYH, Devitt A, Polidori MC, Griffiths HR. Simvastatin reduces circulating oxysterol levels in men with hypercholesterolaemia. Redox Biol. 2018;16:139-45.

- Reboldi A, Dang EV, McDonald JG, Liang G, Russell DW, Cyster JG. Inflammation. 25-Hydroxycholesterol suppresses interleukin-1-driven inflammation downstream of type I interferon. Science. 2014;345(6197):679-84.

- Liu C, Yang XV, Wu J, Kuei C, Mani NS, Zhang L, et al. Oxysterols direct B-cell migration through EBI2. Nature. 2011;475(7357):519-23.

- Lally S, Tan CY, Owens D, Tomkin GH. Messenger RNA levels of genes involved in dysregulation of postprandial lipoproteins in type 2 diabetes: the role of Niemann-Pick C1-like 1, ATP-binding cassette, transporters G5 and G8, and of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein. Diabetologia. 2006;49(5):1008-16.

- Simonen PP, Gylling HK, Miettinen TA. Diabetes contributes to cholesterol metabolism regardless of obesity. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(9):1511-5.

- Matsumura T, Ishigaki Y, Nakagami T, Akiyama Y, Ishibashi Y, Ishida T, et al. Relationship between Diabetes Mellitus and Serum Lathosterol and Campesterol Levels: The CACHE Study DM Analysis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2022.

- Iuliano, L. Pathways of cholesterol oxidation via non-enzymatic mechanisms. Chem Phys Lipids. 2011;164(6):457-68.

- Sato K, Nakano K, Katsuki S, Matoba T, Osada K, Sawamura T, et al. Dietary cholesterol oxidation products accelerate plaque destabilization and rupture associated with monocyte infiltration/activation via the MCP-1-CCR2 pathway in mouse brachiocephalic arteries: therapeutic effects of ezetimibe. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2012;19(11):986-98.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).