Submitted:

31 May 2023

Posted:

01 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- RQ1. If an additional unobservable heterogeneity is introduced by the inclusion of covariates, what is the best method to capture the within-cluster heterogeneity in modeling the total losses, comparing several conventional approaches?

- RQ2. If an additional estimation bias results from the use of the incomplete covariates under Missing At Random (MAR), what is the best way to increase the imputation efficiency, comparing several conventional approaches?

- RQ3. If an individual loss is distributed with log-normal densities, what is the best way to approximate the sum of log-normal outcome variables, comparing several conventional approaches?

2. Discussion on Research Questions and Related Work

2.1. Can Dirichlet Process Capture the Heterogeneity and Bias?: RQ1, RQ2

2.2. Can Log Skew-Normal Mixture Approximate the Log-Normal Convolution?: RQ3

2.3. Our Contribution and Paper Outline

3. Model: DP Log Skew-Normal Mixture for

3.1. Background

- : the parameters of the outcome variable defined with cluster j.

- : the parameter of the cluster weights defined with cluster j.

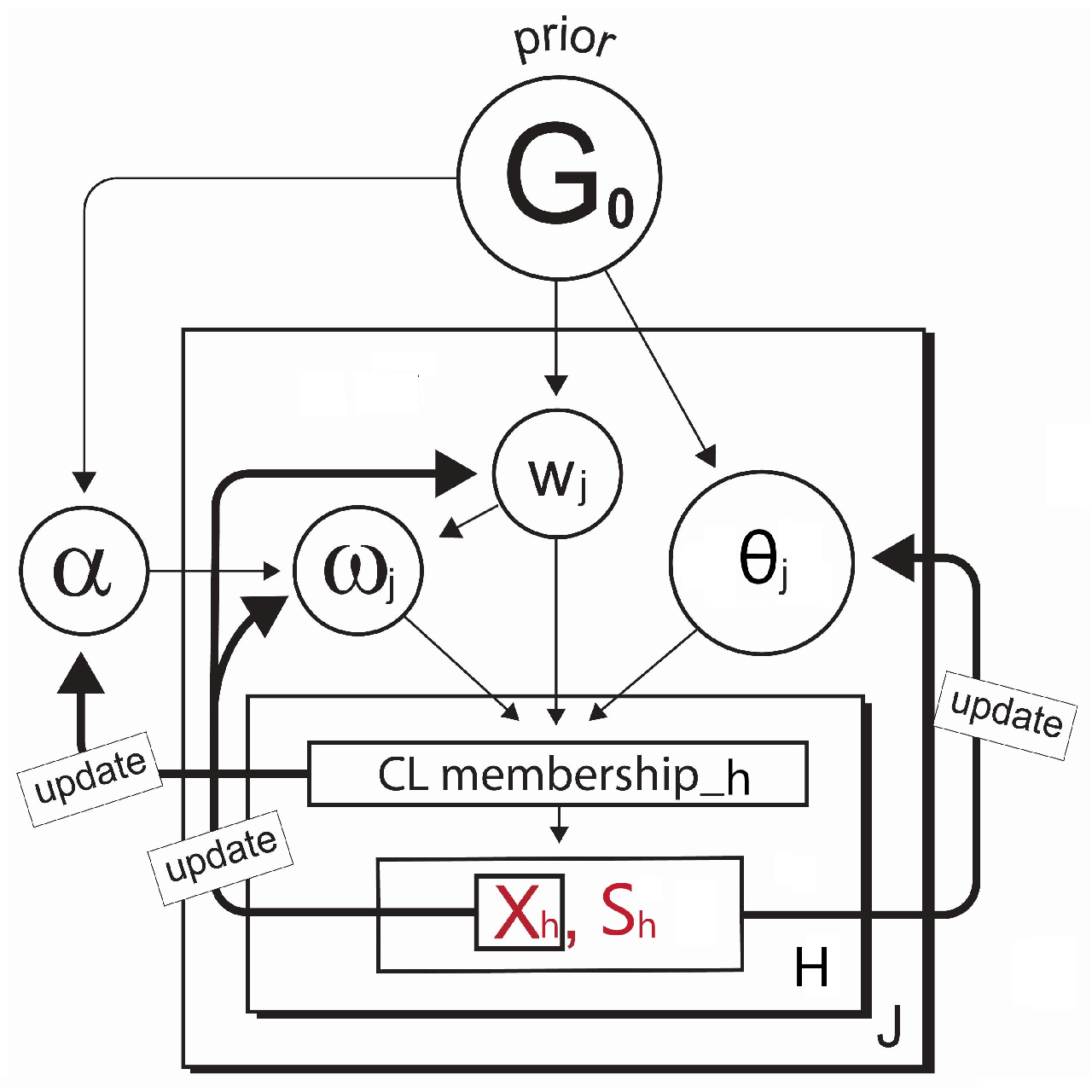

3.2. Model Formulation with Discrete and Continuous Clusters

3.3. Modelling with Complete Case Covariate

- Step.1

-

Initialize the cluster membership and the main parameters:

- (a)

- First the cluster membership is initialized by some clustering methods such as hierarchical clustering or k-means, etc. This step provides an initial clustering of the data ( as well as the initial number of clusters.

- (b)

- Next, after all observations have been assigned to a particular cluster , we can then update the parameters and () for each cluster. This is done using the posterior densities denoted by , and in which () represent all observations in cluster j.

- Step.2

-

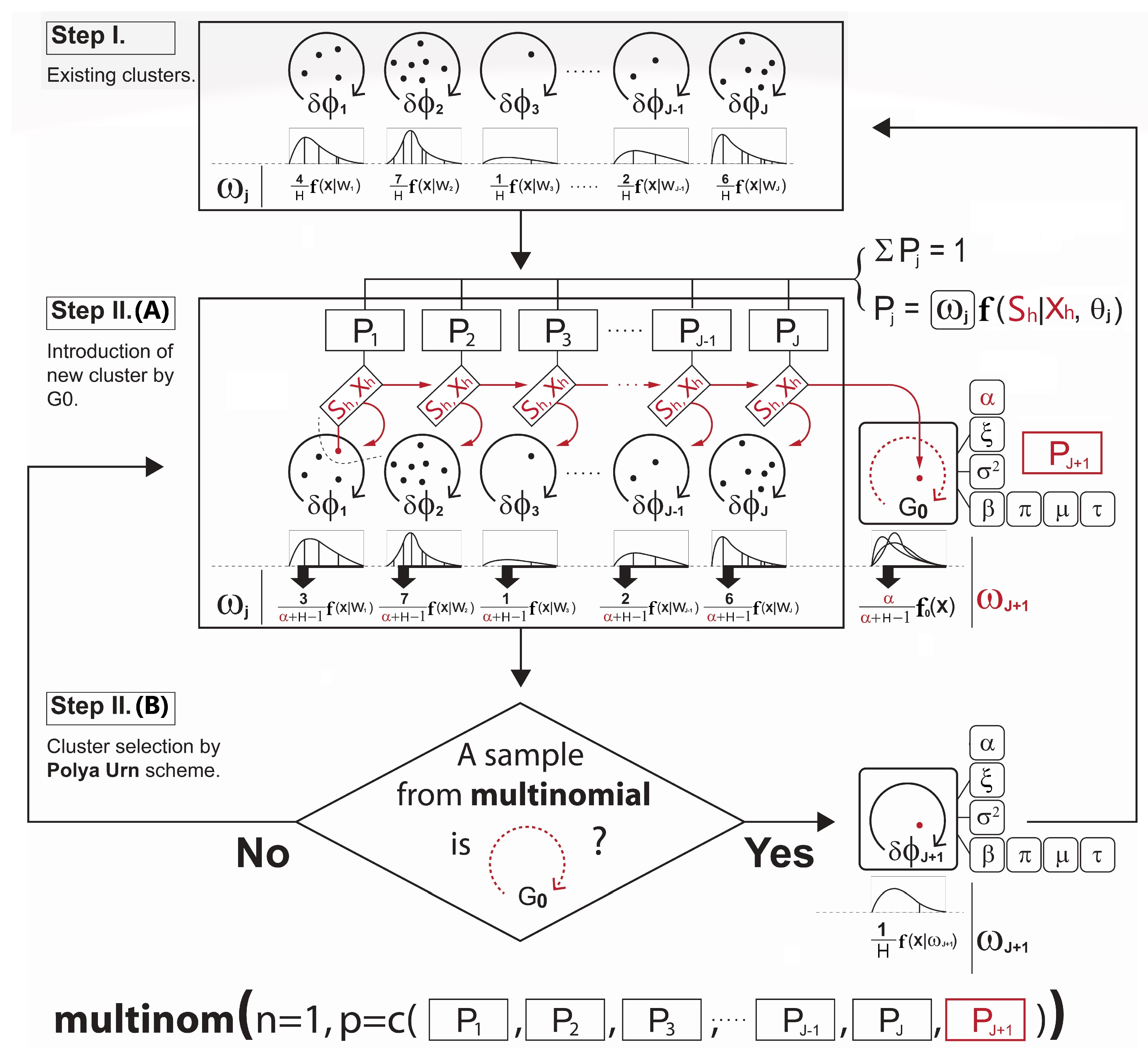

Loop through the Gibbs sampler and new continuous cluster selection:Once the cluster memberships and parameters are initialized, we then loop through the Gibbs sampler many times (e.g. iterations) where the algorithm alternates between updating the cluster membership for each observation and updating the parameters given the cluster partitioning. Each iteration might give a slightly different selection of the new clusters based on the Polya Urn scheme [20], but the log-likelihood calculated at the end of each iteration can help keep track of the convergence of the selections. A detailed description of each iteration is given in Algorithm (A2) in Appendix B. The term on lines 6 and 9 in Algorithm (A2) is the Chinese Restaurant process [19] posterior value given bywhere c is a scaling constant to ensure that the probabilities sum to 1, and is the collection of cluster indices assigned to every observation without the cluster index of the observation h. As shown in Equation (7), the larger results in a higher chance of developing the new continuous cluster and adding to the collection of the existing discrete clusters. The forms of the prior and posterior densities used to simulate the main parameters on lines from 16 to 23 in Algorithm (A2) are presented in Appendix A.

3.4. Modelling with MAR Covariate

- a)

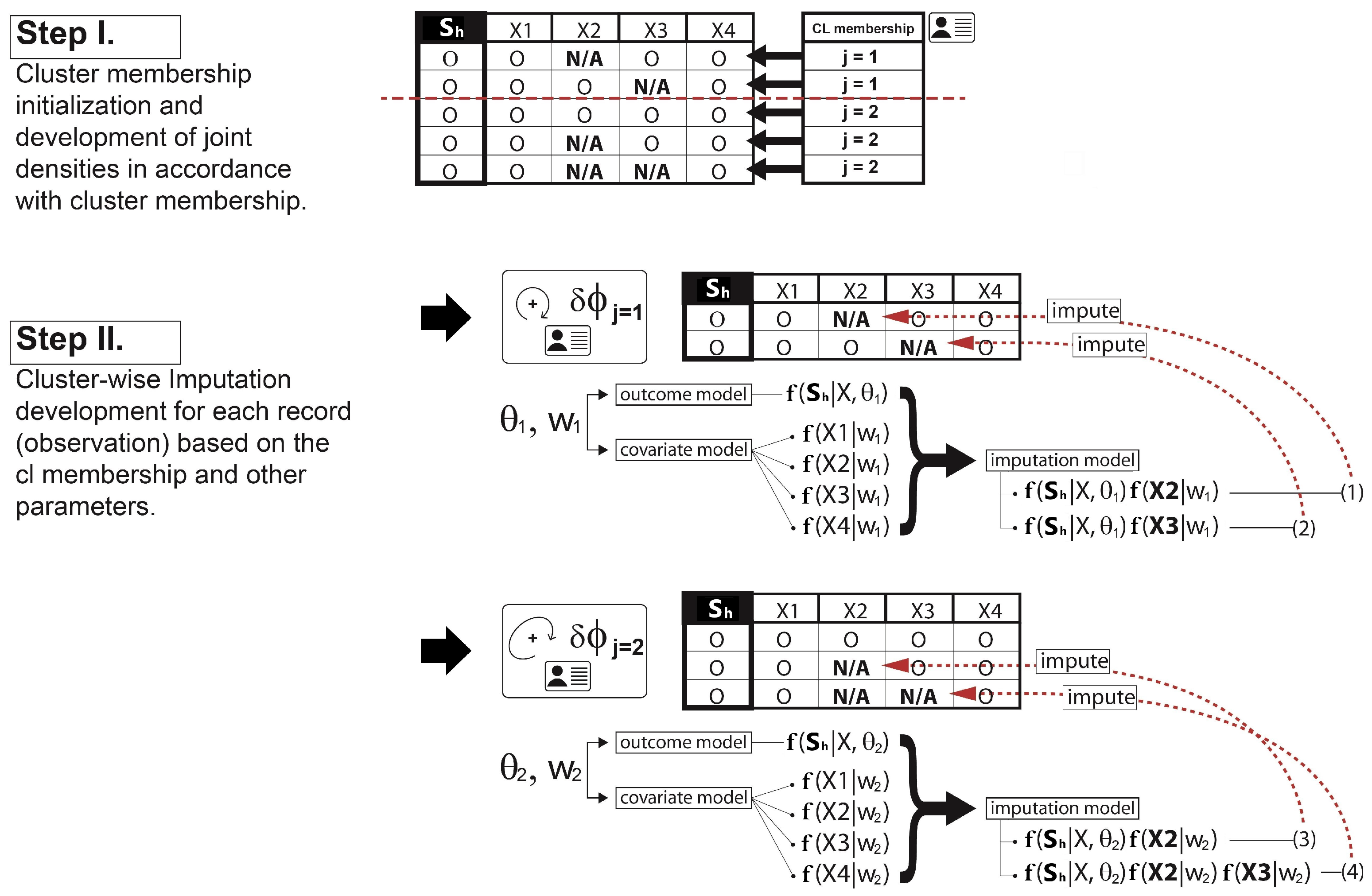

- Imputation: The missing covariate impacts on the parameter - - update. For , only the observations without the missing covariate are used to update. If the cluster does not have any observations with complete data for that covariate, then a draw from the prior distribution would be used to update. For , however, we must first impute values for the missing covariates for all observations within the cluster. Since having already defined a full joint model - - in Section 3.2, we can obtain draws for the MAR covariate from the imputation model such as at each iteration of the Gibbs sampler. The imputation process is briefly illustrated in Figure 3. Once all missing data in all covariates has been imputed, then we can sample from the posterior for and the parameters of each cluster are re-calculated. After this cycle is complete, the imputed data is discarded and the same imputation steps are repeated every iteration.

- b)

-

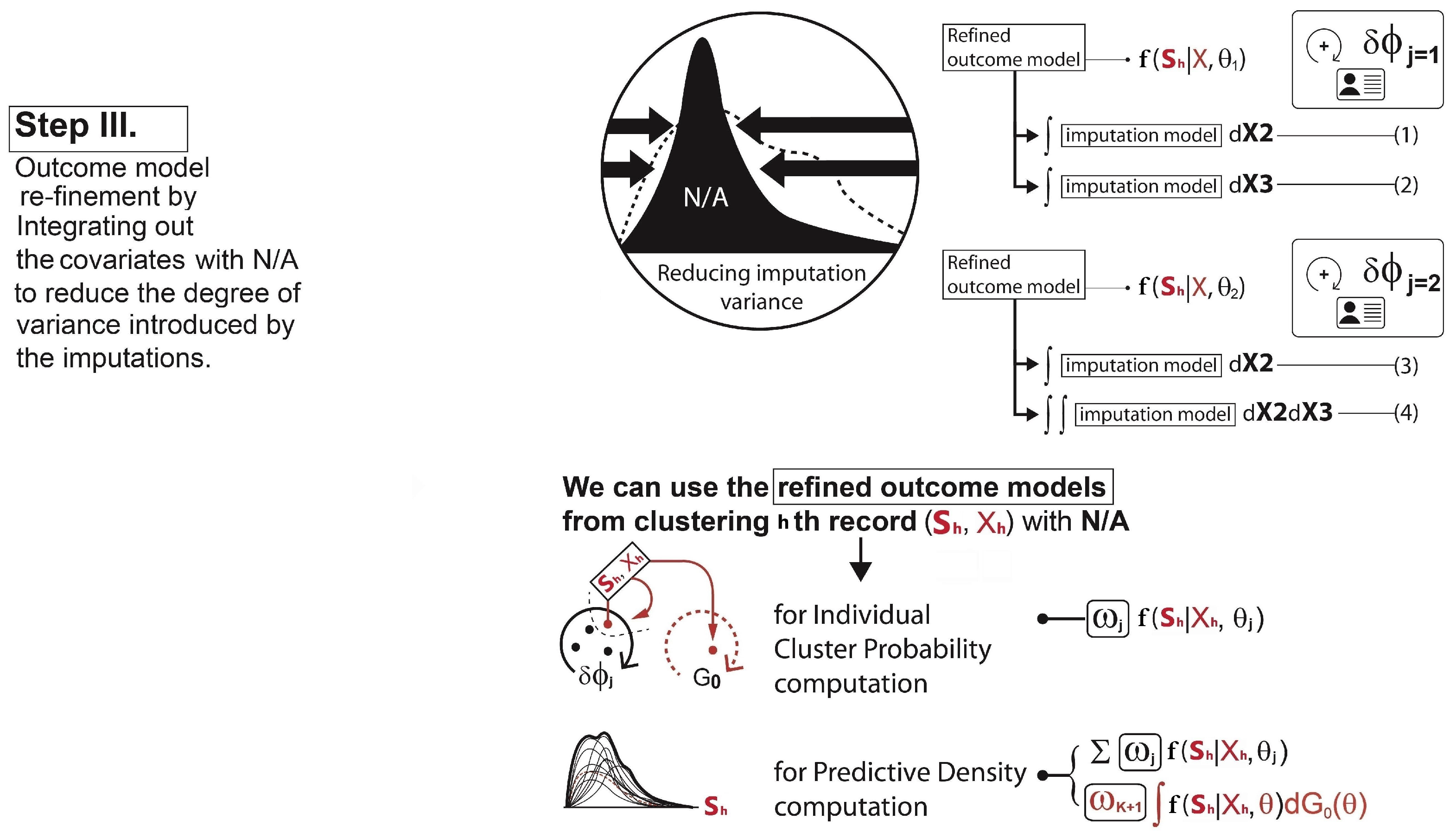

Re-clustering: To determine each cluster probability after the imputations, the algorithm re-defines the two main components for the cluster probability calculation - 1) covariate model, 2) outcome model. For the covariate model , we set this equal to the density functions of only those covariates with complete data for observation h. Assuming that , and the covariate is missing for observation h, then we drop and only use in the covariate model,This is the refined covariate model for the cluster j with the observation h where the data in is not available. For the outcome model , the algorithm simply takes the imputation model for each cluster and integrates them out the covariates with missing data. This reduces the degree of variances introduced by the imputations. In our case, as covariate is missing for observation h, this missing covariate can be removed from the term that is being conditioned on. Therefore, the refined outcome model isA similar process is conducted for each observation with missing data and each combination of missing covariates. Hence, using Equation (8,9), the cluster probabilities and the predictive distribution can be obtained as illustrated in Step III in Figure 4.

- c)

4. Bayesian Inference for with MAR Covariate

4.1. Parameter Models and MAR Covariate

4.2. Data Models and MAR Covariate

- a)

-

covariate model for the discrete cluster:Focusing on the scenario that is binary, is Gaussian, and the only covariate with missingness is , we simply drop the covariate to develop the covariate model for the discrete cluster. For instance, when computing the covariate probability term for hth observation in j cluster, the covariate model simply becomes due to the missingness of . As we have that is assumed to be normally distributed as defined in Equation (1), its probability term isinstead of

- b)

-

covariate model for the continuous cluster:If the binary covariate is missing, by the same logic, we drop the covariate for the continuous cluster; however, using Equation (4), the covariate model for the continuous cluster integrates out the relevant parameters simulated from the Dirichlet process prior as follows:instead ofThe derivation of the distributions above is provided in Appendix C.3.

- c)

-

outcome model for the discrete cluster:In developing the outcome model, as with the parameter model case discussed in Section 4.1 and Appendix C.2, it should be ensured that the covariate is complete beforehand. With all missing data in imputed, the outcome model for the discrete cluster is obtained by marginalizing the joint - - out the MAR covariate , which is a log skew-normal mixture as follows:instead of

- d)

-

outcome model for the continuous cluster:Once a missing covariate is fully imputed and the outcome model is marginalized out conditioned to the MAR covariate , the outcome model for the continuous cluster can also be computed by integrating out the relevant parameters, using Equation (4).However, it can be too complicated to compute its form analytically. Instead, we can integrate the joint model out the parameters, using Monte Carlo integration. For example, we can do the following for each .

- (i)

- Sample from the DP prior densities specified previously.

- (ii)

- Plug in these samples into .

- (iii)

- Repeat the above steps many times, recording each output.

- (iv)

- Divide the sum of all output values by the number of Monte Carlo samples, which will be the approximate integral.

4.3. Gibbs Sampler Modification for MAR Covariate

- a)

- b)

- c)

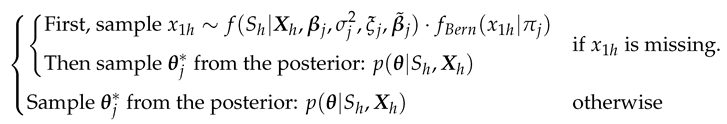

- In line 22, with the presence of missing covariate , the imputation should be made before simulating the parameter as follows,

5. Empirical Study

5.1. Data

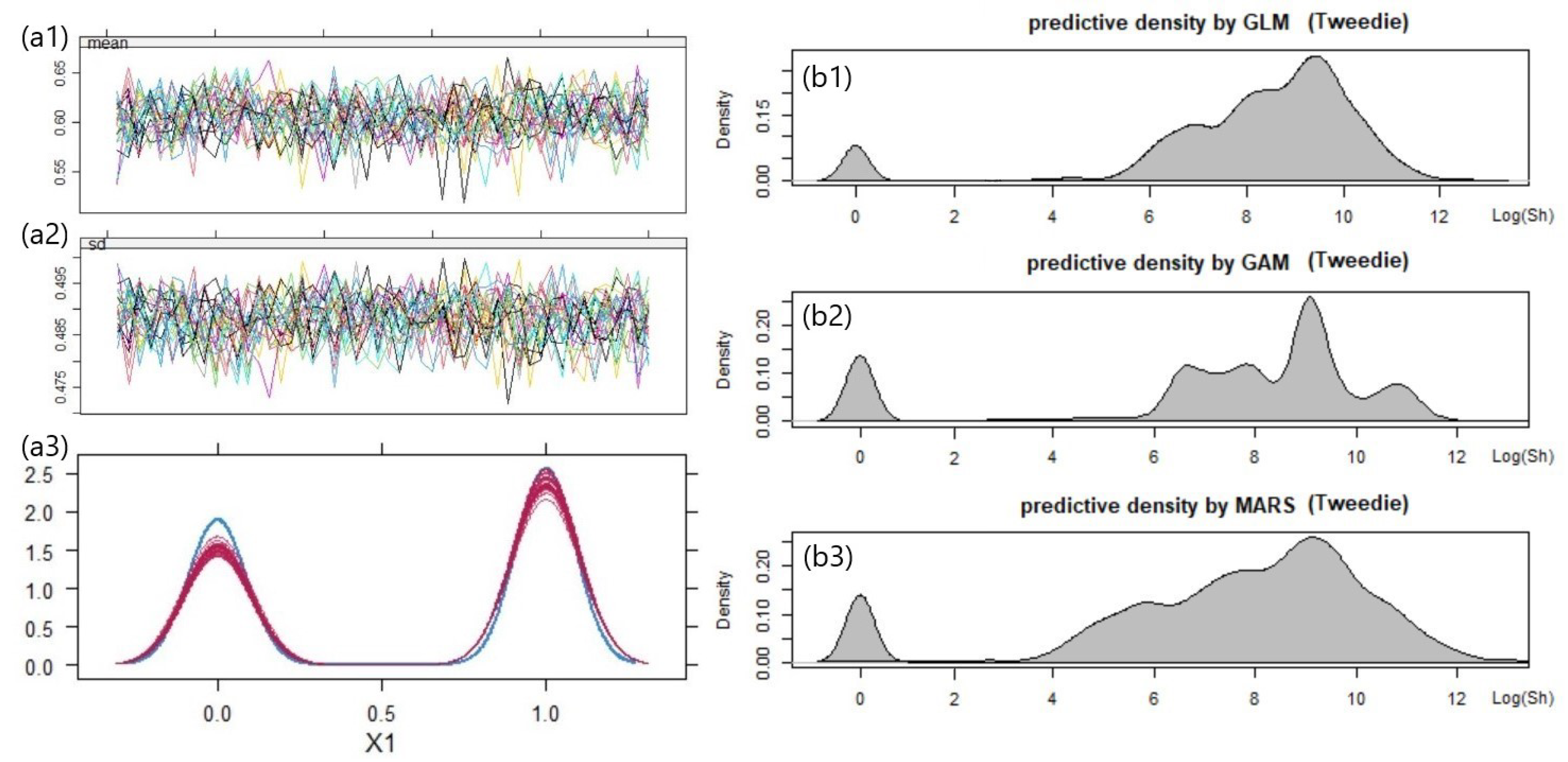

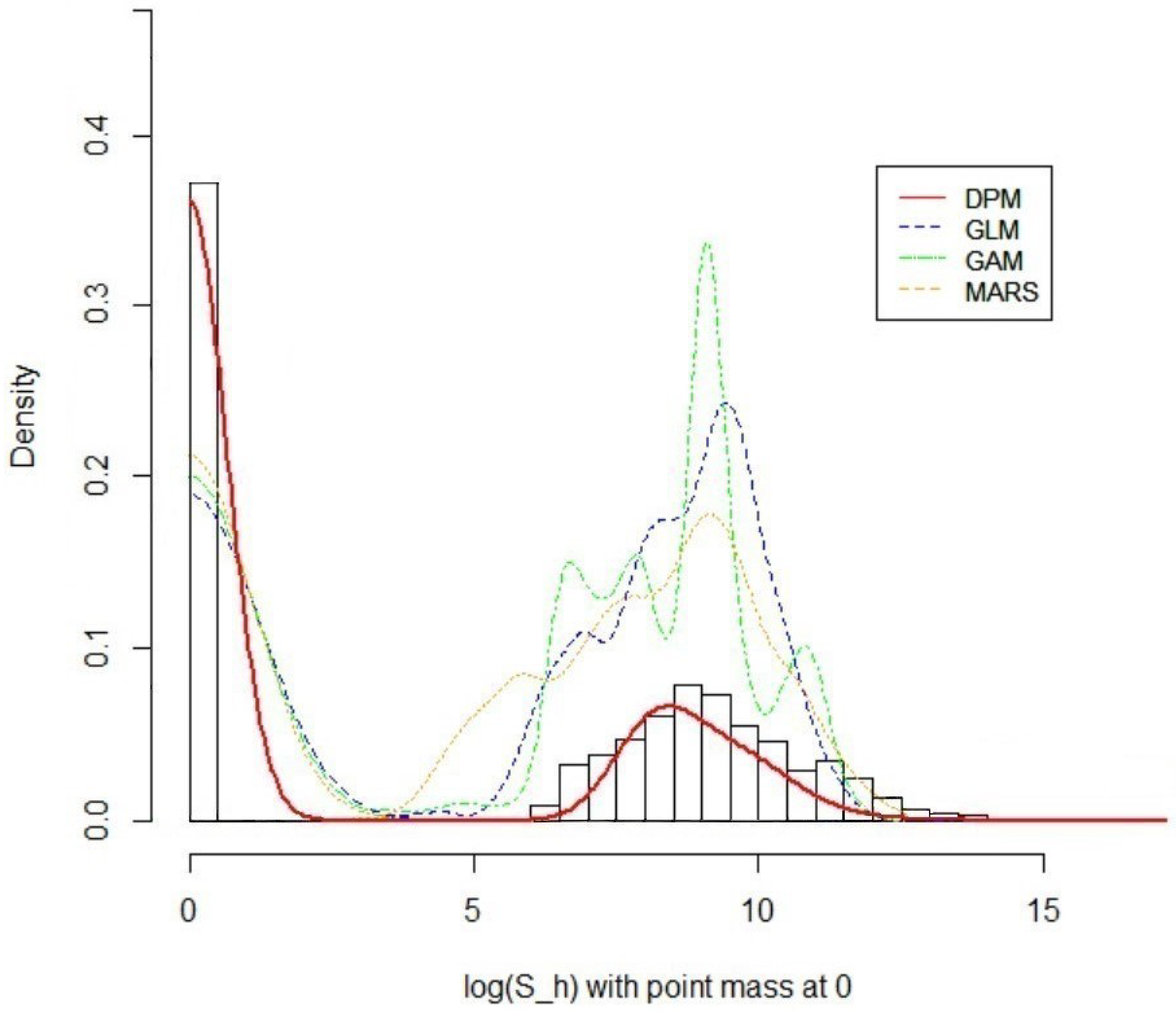

5.2. Three Competitor Models and Evaluation

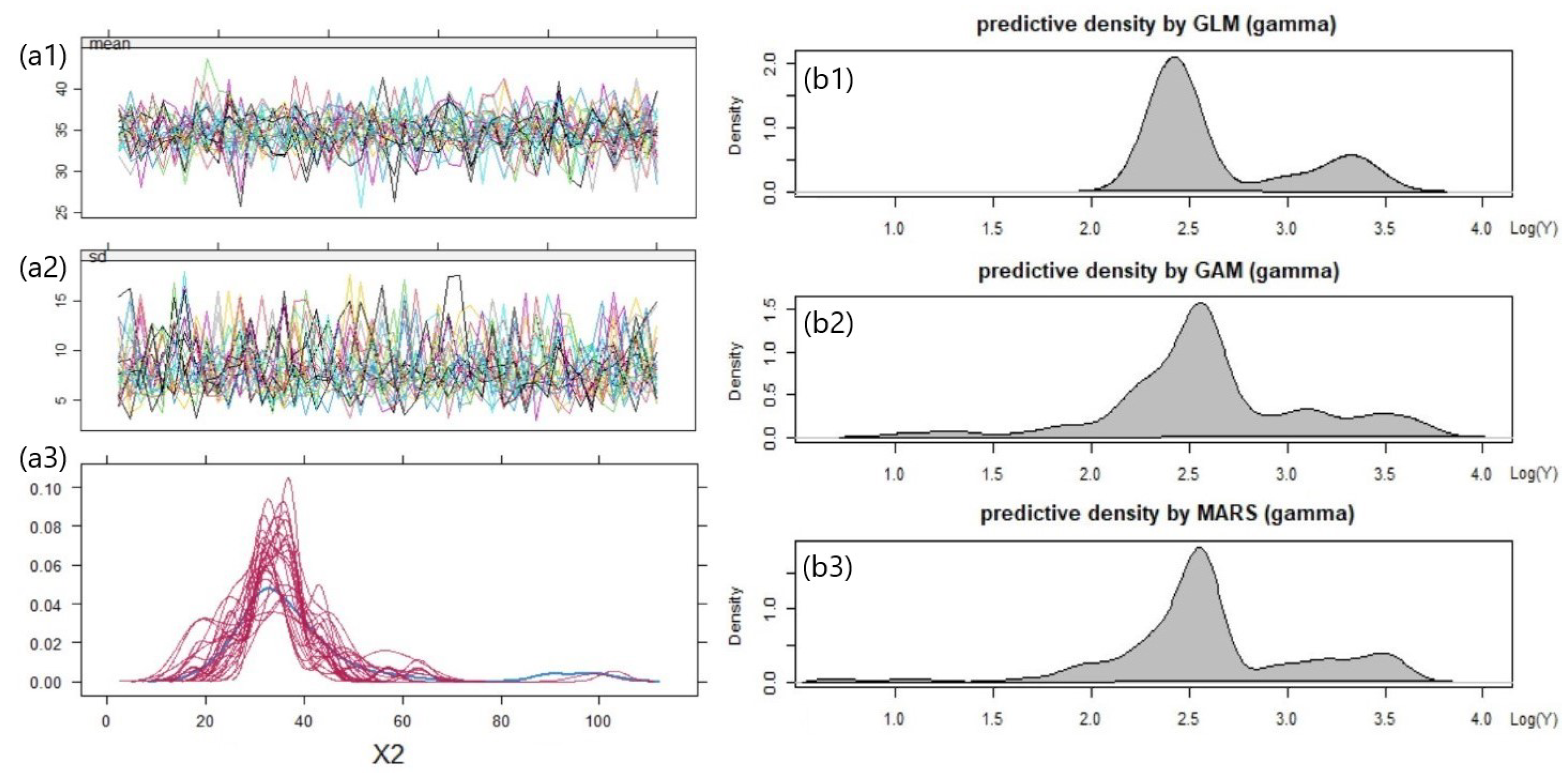

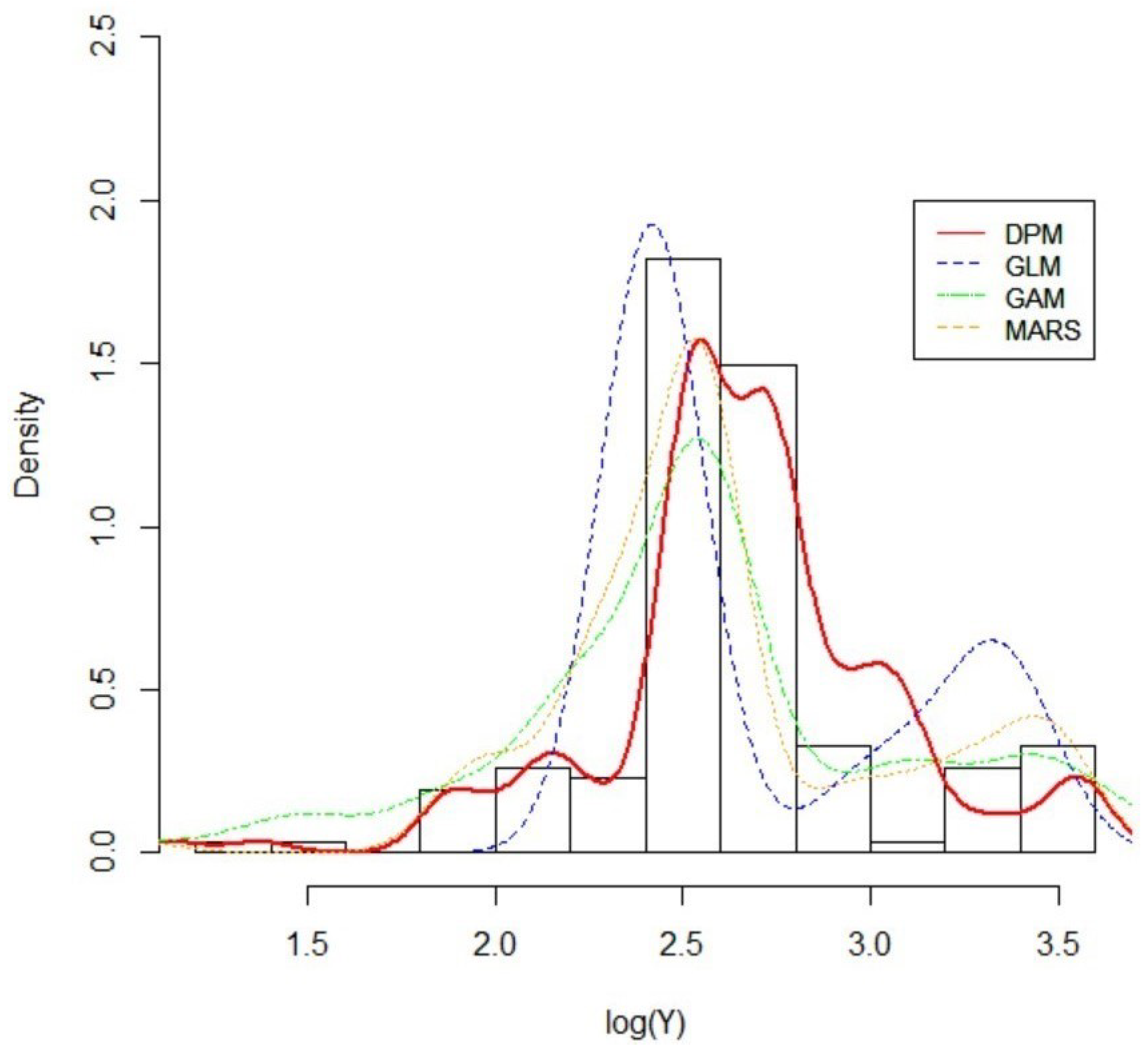

5.3. Result 01. International General Insurance Liability Data

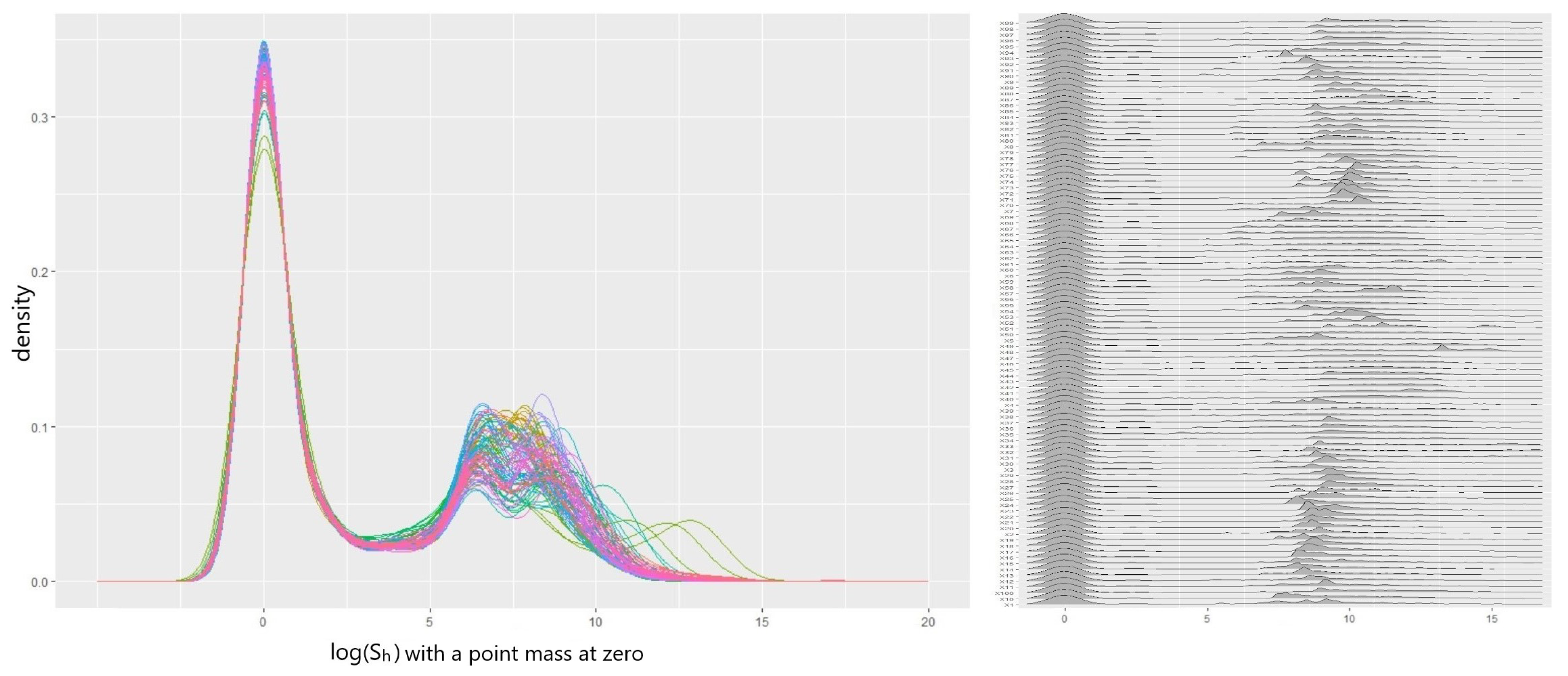

5.4. Result 02. LGPIF Data

6. Discussion

6.1. Research Questions

6.2. Future Work

- (a)

- Dimensionality: First, in our analysis, we only use two covariates (binary and continuous) for simplicity, hence more complex data should be considered. As the number of covariates grows, the likelihood components (covariate models) to describe the covariates grow, which results in the shrinking of the cluster weights. Therefore, using more covariates might enhance the level of sensitivity and accuracy in the creation of cluster memberships. However, it can also introduce more noise or hidden structures that render the resulting predictive distributions unstable. In this sense, further research on the problem of high dimensional covariates in the DPM framework would be worthwhile.

- (b)

- Measurement error: Second, although our focus in this article is MAR covariate, mismeasured covariate is an equally significant challenge that impairs the proper model development in insurance practice. For example, Aggarwal et al. (2016) [28] point out that “model risk" mainly arises due to missingness and measurement error in variables, leading to flawed risk assessments and decision-making. Thus, further investigation is necessary to explore the specialized construction of the DPM Gibbs sampler for mismeasured covariates, aiming to prevent the issue of model risk.

- (c)

- Sum of log skew-normal: Third, as an extension to the approximation of total losses (the sum of individual losses) for a policy, we recommend researching into ways to approximate the sum of total losses across entire policies. In other words, we pose the question of “how to approximate the sum of log skew-normal random variables". From the perspective of an executive or an entrepreneur whose concern is the total cash flow of the firm, nothing might be more important than the accurate estimation of the sum of total losses in order to identify the insolvency risk or to make important business decisions.

- (d)

- Scalability: Lastly, we suggest investigating the scalability of the posterior simulation by our DPM Gibbs sampler. As shown in our empirical study on the PnCdemand dataset, our DPM framework produces reliable estimates with relatively small sample sizes (). This is because our DPM framework actively utilizes significant prior knowledge in posterior inference rather than heavily relying on the actual features of the data. In the result from the LGPIF dataset, our DPM exhibits stable performance at sample size as well. However, a sample size of over 10000 is not explored in this paper. With increasing amounts of data, our DPM framework raises a question of computational efficiency due to the growing demand for computational resources or degradation in performance [29]. This is an important consideration, especially in scenarios where the insurance loss information is expected to grow over time.

7. Variable Definitions

| observation index i in policy h. | |

| policy index h with sample (policy) size H. | |

| cluster index for J clusters. | |

| cluster index for observation h. | |

| number of observations in cluster j. | |

| number of observations in cluster j where observation h removed from. | |

| individual loss i in a policy observation h. | |

| outcome variable which is a in a policy observation h. | |

| outcome variable which is a across entire policies | |

| vector of covariates (including ) for observation h. | |

| vector of covariate (Fire5). | |

| vector of covariate (Ln(coverage)). | |

| individual value of covariate (Fire5). | |

| individual value of covariate (Ln(coverage)). | |

| parameter model (for prior). | |

| parameter model (for posterior). | |

| data model (for continuous cluster). | |

| data model (for discrete cluster). | |

| logistic sigmoid function - expit(·) - to allow for a positive probability of the zero outcome. | |

| set of parameters - - associated with the for j cluster. | |

| set of parameters - - associated with the for j cluster. | |

| cluster weights (mixing coefficient) for j cluster. | |

| vector of initial regression coefficients and variance-covariance matrix, i.e. obtained from the baseline multivariate Gamma regression of . | |

| regression coefficient vector for a mean outcome estimation. | |

| cluster-wise variation value for the outcome. | |

| skewness parameter for log skew-normal outcome. | |

| vector of initial regression coefficients and variance-covariance matrix obtained from the baseline multivariate logistic regression of . | |

| regression coefficient vector for a logistic function to handle zero outcomes. | |

| proportion parameter for Bernoulli covariate. | |

| location and spread parameter for Gaussian covariate. | |

| precision parameter that controls the variance of the clustering simulation. For instance, a larger allows to select more clusters. | |

| prior joint distribution for all parameters in the DPM - , and . It allows all continuous, integrable distributions to be supported while retaining theoretical properties and computational tractability such as asymptotic consistency, efficient posterior estimation, etc. | |

| hyperparameters for Inverse Gamma density of . | |

| hyperparameters for Beta density of . | |

| hyperparameters for Student’s t density of . | |

| hyperparameters for Gaussian density of . | |

| hyperparameters for Inverse Gamma density of . | |

| hyperparameters for Gamma density of . | |

| random probability value for Gamma mixture density of the posterior on . | |

| mixing coefficient for Gamma mixture density of the posterior on . |

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A Parameter Knowledge

Appendix A.1. Prior Kernel for Distributions of Outcome, Covariates, and Precision

Appendix A.2. Posterior Inference for Outcome, Covariates, and Precision

| Algorithm A1:Posterior inference |

|

Appendix B Baseline Inference Algorithm for DPM

| Algorithm A2:DPM Gibbs Sampling for new cluster development |

|

Appendix C Development of the Distributional Components for DPM

Appendix C.1. Derivation of the Distribution of Precision α

- observation 1 forms a new cluster, probability =

- observation 2 forms a new cluster, probability =

- observation 3 enters into an existing cluster, probability =

- observation 4 enters into an existing cluster, probability =

- observation 5 forms a new cluster, probability =

Appendix C.2. Outcome Data Model of S h Development with MAR Covariate x 1 for the Discrete Clusters

Appendix C.3. Covariate Data Model of x 2 Development with MAR Covariate x 1 for the Continuous Clusters

References

- Hong, L.; Martin, R. Dirichlet process mixture models for insurance loss data. Scandinavian Actuarial Journal 2018, 2018, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhaus, J.M.; McCulloch, C.E. Separating between-and within-cluster covariate effects by using conditional and partitioning methods. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 2006, 68, 859–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaas, R.; Goovaerts, M.; Dhaene, J.; Denuit, M. Modern actuarial risk theory: using R; Vol. 128, Springer Science & Business Media, 2008.

- Beaulieu, N.C.; Xie, Q. In Proceedings of the Minimax approximation to lognormal sum distributions. The 57th IEEE Semiannual Vehicular Technology Conference, 2003. VTC 2003-Spring. IEEE, 2003, Vol. 2, pp. 1061–1065.

- Ungolo, F.; Kleinow, T.; Macdonald, A.S. A hierarchical model for the joint mortality analysis of pension scheme data with missing covariates. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 2020, 91, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Fader, P.S.; Bradlow, E.T.; Kunreuther, H. Modeling the “pseudodeductible” in insurance claims decisions. Management Science 2006, 52, 1258–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. A Novel Accurate Approximation Method of Lognormal Sum Random Variables. PhD thesis, Wright State University, 2008.

- Roy, J.; Lum, K.J.; Zeldow, B.; Dworkin, J.D.; Re III, V.L.; Daniels, M.J. Bayesian nonparametric generative models for causal inference with missing at random covariates. Biometrics 2018, 74, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, Y.; Reiter, J.P. Nonparametric Bayesian multiple imputation for incomplete categorical variables in large-scale assessment surveys. Journal of educational and behavioral statistics 2013, 38, 499–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, E.; Hackmann, D.; Kuznetsov, A. On log-normal convolutions: An analytical–numerical method with applications to economic capital determination. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 2020, 90, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Ding, J. Least squares approximations to lognormal sum distributions. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2007, 56, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.L.J.; Le-Ngoc, T. Log-shifted gamma approximation to lognormal sum distributions. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2007, 56, 2121–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, S. The Dirichlet process, related priors and posterior asymptotics. Bayesian nonparametrics 2010, 28, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, T.S. A Bayesian analysis of some nonparametric problems. The annals of statistics. 1973, pp. 209–230.

- Antoniak, C.E. Mixtures of Dirichlet processes with applications to Bayesian nonparametric problems. The annals of statistics, 1152. [Google Scholar]

- Sethuraman, J. A constructive definition of Dirichlet priors. Statistica sinica.

- Hong, L.; Martin, R. A flexible Bayesian nonparametric model for predicting future insurance claims. North American Actuarial Journal 2017, 21, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebolt, J.; Robert, C.P. Estimation of finite mixture distributions through Bayesian sampling. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1994, 56, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Frazier, P.I. Distance dependent Chinese restaurant processes. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Gershman, S.J.; Blei, D.M. A tutorial on Bayesian nonparametric models. Journal of Mathematical Psychology 2012, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, A.J.; Blake, D.; Dowd, K.; Coughlan, G.D.; Khalaf-Allah, M. Bayesian stochastic mortality modelling for two populations. ASTIN Bulletin: The Journal of the IAA 2011, 41, 29–59. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, M.D.; West, M. Bayesian density estimation and inference using mixtures. Journal of the american statistical association 1995, 90, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.J.; Chung, J.; Frees, E.W. International Property-Liability Insurance Consumption. The Journal of Risk and Insurance 2000, 67, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Z.; Valdez, E.A. Predictive analytics of insurance claims using multivariate decision trees. Dependence Modeling 2018, 6, 377–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, Y.W. Dirichlet Process. 2010.

- Gelman, A.; Hill, J. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models; Cambridge university press, 2007.

- Shah, A.D.; Bartlett, J.W.; Carpenter, J.; Nicholas, O.; Hemingway, H. Comparison of random forest and parametric imputation models for imputing missing data using MICE: a CALIBER study. American journal of epidemiology 2014, 179, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, A.; Beck, M.B.; Cann, M.; Ford, T.; Georgescu, D.; Morjaria, N.; Smith, A.; Taylor, Y.; Tsanakas, A.; Witts, L.; others. Model risk–daring to open up the black box. British Actuarial Journal 2016, 21, 229–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Ji, Y.; Müller, P. Consensus Monte Carlo for random subsets using shared anchors. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 2020, 29, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | AIC | SSPE | SAPE | 10% CTE | 50% CTE | 90% CTE | 95% CTE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ga-GLM | 830.56 | 268.6 | 139.8 | 6.5 | 13.8 | 54.5 | 78.0 |

| Ga-MARS | 830.58 | 267.2 | 138.2 | 6.1 | 13.0 | 57.2 | 71.1 |

| Ga-GAM | 845.94 | 266.7 | 136.1 | 6.2 | 13.3 | 58.1 | 72.2 |

| LogN-DPM | - | 272.0 | 134.7 | 6.4 | 13.8 | 59.3 | 79.3 |

| Model | AIC | SSPE | SAPE | 10% CTE | 50% CTE | 90% CTE | 95% CTE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tweedie-GLM | 26270.3 | 2.04e+14 | 89380707 | 955.9 | 12977.2 | 133374.4 | 340713.1 |

| Tweedie-MARS | 24721.4 | 1.99e+14 | 88594850 | 961.7 | 10391.0 | 129409.2 | 355112.6 |

| Tweedie-GAM | 21948.9 | 1.95e+14 | 88213987 | 989.4 | 13026.2 | 140199.5 | 398263.1 |

| LogSN-DPM | - | 1.98e+14 | 83864890 | 975.3 | 13695.1 | 147486.6 | 425682.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).