Submitted:

29 May 2023

Posted:

30 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

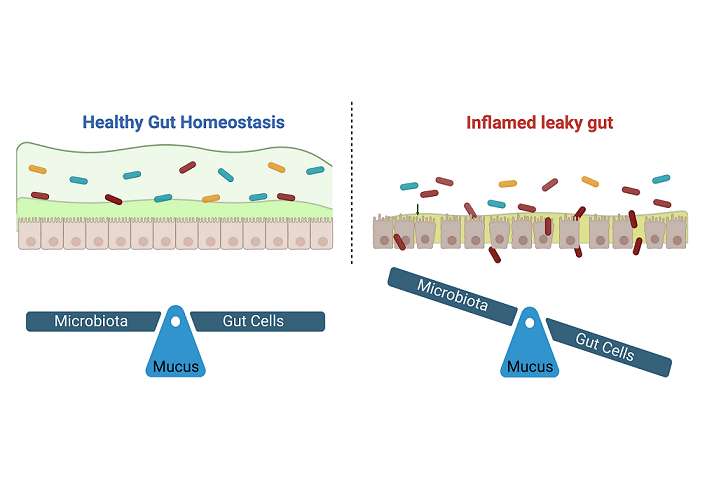

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

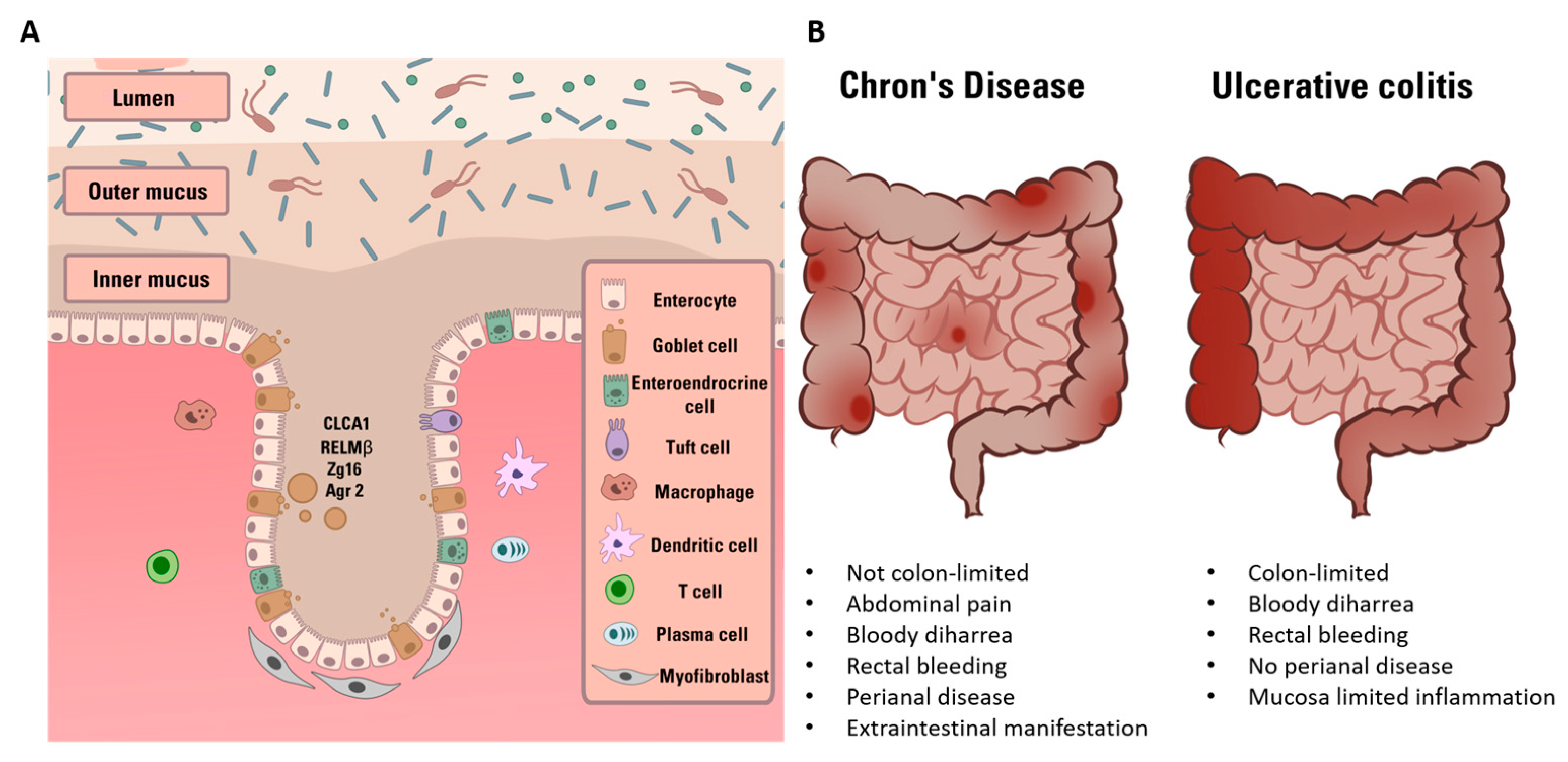

2. General aspect and relevance of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

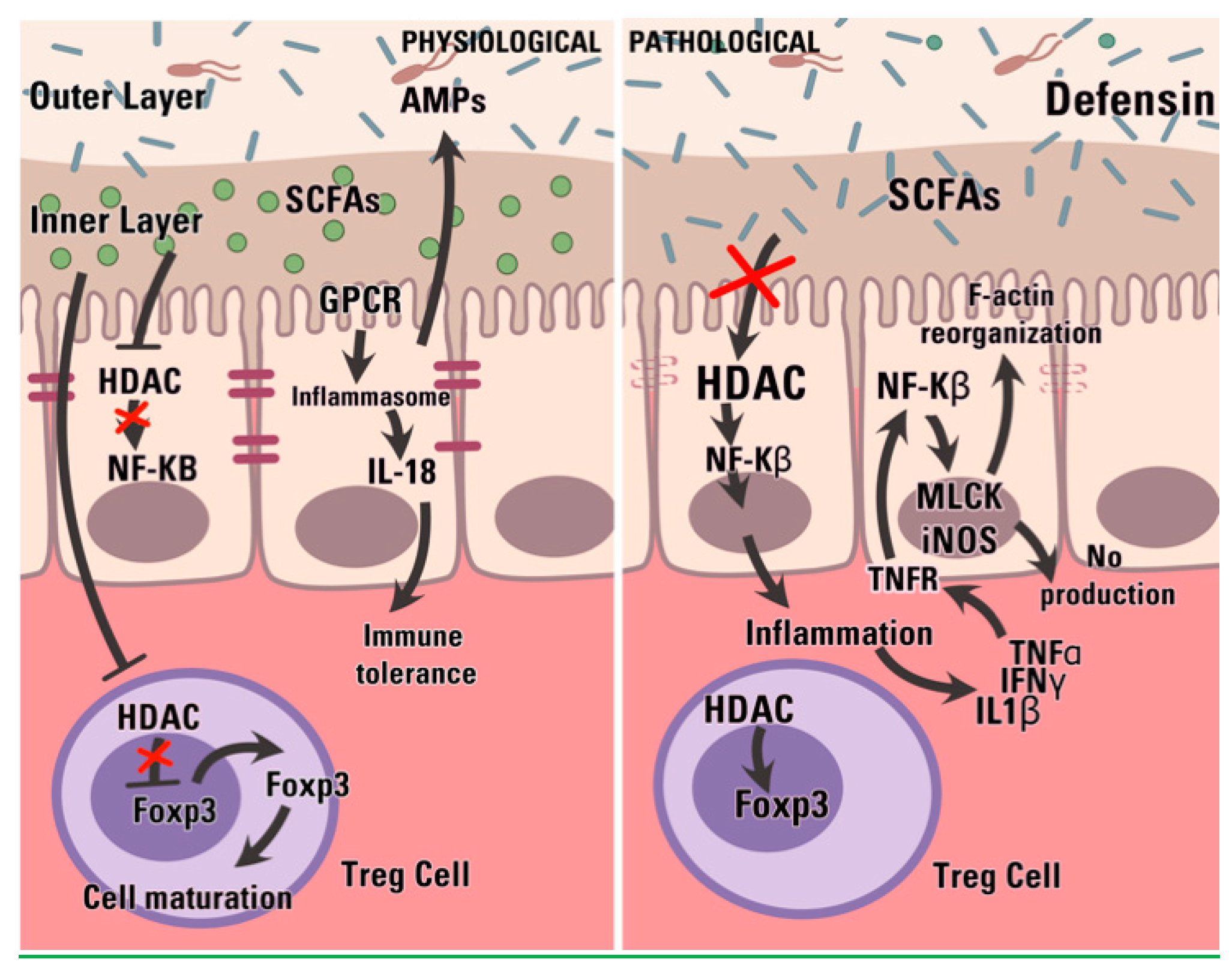

3. Intestinal epithelial cells in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

4. Intestinal microbiota and dysbiosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

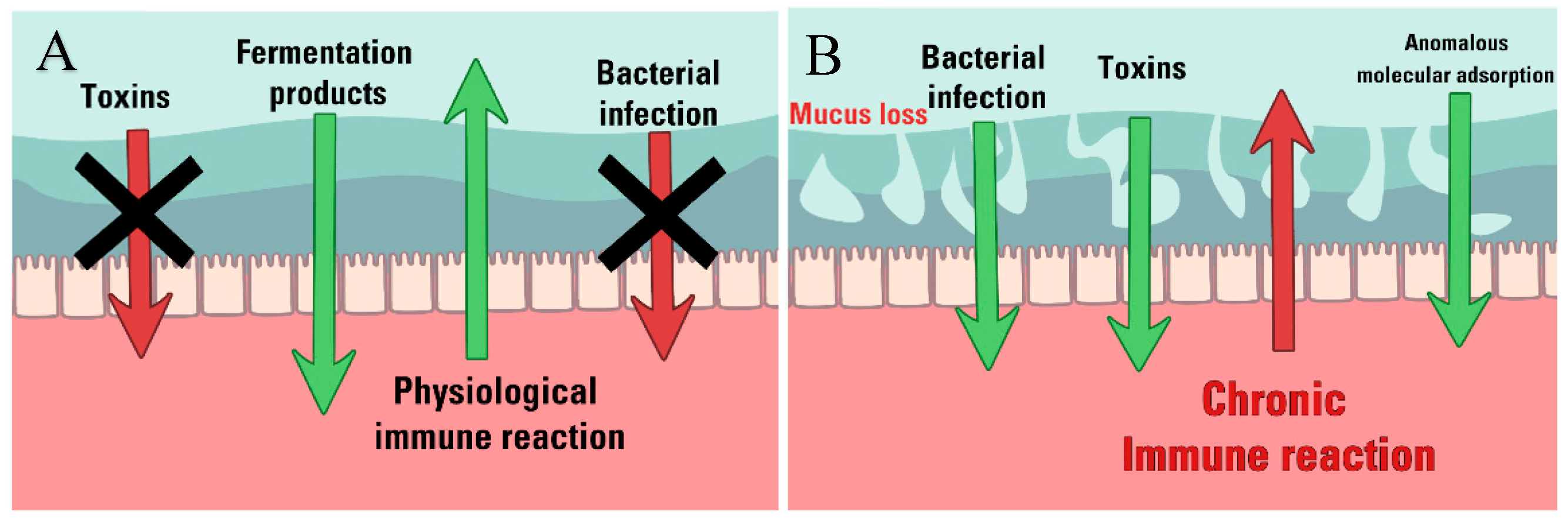

5. Intestinal mucus Barrier in IBD

5.1. Compositional variation

5.2. Structural weakening

6. Barrier integrity and permeability assays

- Active and passive permeability assays: Active permeability assays require the oral administration of sugars or polymers and the measurement of urinary concentrations at different time points from 30 min to 24 hours [146]. The higher is the molecule concentration, the leakier the epithelial barrier. A common method is based on the administration of different molecules (e.g. lactulose, mannitol, PEG (polyethylene glycol) molecules and sucrose among others) and the measurement of their concentration in urine, thus obtaining information about the permeability of the mucosa in different region of the gut, which is in dependence of the size and the nature of the administered substance [146,147,148,149,150]. The use of the radioactive 51Cr-EDTA were not only able to describe an increased permeability in CD patients (20% higher than healthy controls) but also to correlate this permeability variation with a reduction in specific bacteria abundance (i.e. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii) [151]. No consideration was proposed in terms of mucus properties, whose contribution remained clouded under the permeability characterization. The principle of passive permeability assays is similar to the active methods described above. The main difference is the nature of the detected molecules, which are usually products of the individual metabolism (e.g. bacteria-derived molecules, intestinal integrity-related or immunological biomarkers) measured in plasma, serum and biopsies [149]. Among the bacterial-derived molecules, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and butyrate are of primary importance, as they are the major components of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and biomarker of intestinal barrier integrity, respectively [140,152,153,154,155]. Epithelial and immune biomarkers detection in plasma and urine is another effective method to define the intestinal barrier integrity (i.e. citrullin and claudin-3) [53,156,157]. The inflammatory marker mainly investigated in UC and CD is calprotectin, a product of active and infiltrated neutrophils in the intestinal mucosa. High levels of fecal calprotectin (>100 µg/g) were correlated with higher levels of intestinal permeability indicators and give an indirect measure of IBD severity [151]. Similarly to active permeability assay, the passive permeability assays have the possibility to correlate bacterial products to dysbiosis and intestinal barrier impairment, but do not provide information about the relative contribution of mucus within the epithelial barrier. The inclusion of a more detailed characterisation of mucus could provide a deeper understanding of these experimental evidence. For instance, the study of the variation of the mucus network microstructure can elucidate if the diffusion of molecules from lumen to epithelium is facilitate or impaired. Similarly, compositional changes can provide information of the dye/molecules affinity with the mucus matrix.

- Confocal laser endomicroscopy. Confocal laser endomicroscopy allows the acquisition of confocal images during endoscopic procedures [158]. It provides information about the epithelial barrier morphology. This method requires the intravenous administration of a fluorescent dye – such as fluorescein – that could be easily excited by the laser of the endomicroscope. A detector then transforms the emitted light signal into an electrical input for computational recording. This method generates accurate images giving evident information on the barrier morphology and the epithelial crypts architecture [159]. These analyses highlighted frequent morphological features of IBD epithelia, such as intra- and inter-crypt distance increase, irregular crypt organization, micro- and macro-lesions leading to cell and molecule infiltrates increase [149]. Overall, endomicroscopy not only provides critical data for the determination of the barrier impairment but also allows to limit the collection of biopsies to strictly necessary cases. Despite the epithelial barrier is well examined, the mucus barrier contribution is still poorly considered while information about gut dysbiosis is not provided at all.

- Ussing chamber. The Ussing chamber-based method is an invasive assay used to determine intestinal barrier integrity and permeability. It is performed on intestinal tissue biopsies and requires invasive procedures to collect ex vivo specimens. This technique is based on the measurement of a voltage difference (ΔVEP) and a trans-epithelial (o trans-mucosal) electric resistance (TEER o TER, respectively) between the apical and the basolateral side of the barrier. It requires the application of active ion transport through the epithelium and the measurement of the ΔVEP and TER. The ion transport is correlated to the barrier integrity. The weaker the epithelium, the higher will be the transport and the lower the TER [149,160] Like previous well-established clinical assays, the Ussing chamber-based method is a valuable approach to study the intestinal barrier function in IBD, as it was demonstrated for instance that IBD patients showed a decrease of TER near the 39% [161]. However, it cannot provide information about the relative contribution of the elements modulating barrier disruption.

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lerner, P. Jeremias, and T. Matthias, “The world incidence and prevalence of autoimmune diseases is increasing,” International Journal of Celiac Disease, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 151–155, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Sherlock and E. I. Benchimol, “Classification of inflammatory bowel disease in children,” Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Third Edition, pp. 181–191, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. W. Miller, “The increasing prevalence of autoimmunity and autoimmune diseases: an urgent call to action for improved understanding, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention,” Curr Opin Immunol, vol. 80, p. 102266, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Chauhan et al., “WHO task group on environmental health criteria on principles and methods for assessing autoimmunity associated with exposure to chemicals,” Environmental Health Criteria, no. 236, 2006.

- D. S. Pisetsky, “Pathogenesis of autoimmune disease,” Nature Reviews Nephrology 2023, pp. 1–16, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Barreiro-de Acosta et al., “Epidemiological, Clinical, Patient-Reported and Economic Burden of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) in Spain: A Systematic Review,” Adv Ther, vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 1975–2014, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Thursby and N. Juge, “Introduction to the human gut microbiota,” Biochemical Journal, vol. 474, no. 11. Portland Press Ltd, pp. 1823–1836, Jun. 01, 2017. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160510.

- R. M. Patel and P. W. Denning, “Therapeutic Use of Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Postbiotics to Prevent Necrotizing Enterocolitis. What is the Current Evidence?,” Clin Perinatol, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 11–25, 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Wong and M. Levy, “New Approaches to Microbiome-Based Therapies,” mSystems, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 1–5, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Sekhon and S. Jairath, “Prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics: an overview,” Journal of pharmaceutical education and research, vol. 1, no. 2, p. 13, 2010.

- S. Ahlawat, P. Kumar, H. Mohan, S. Goyal, and K. K. Sharma, “Inflammatory bowel disease: tri-directional relationship between microbiota, immune system and intestinal epithelium,” https://doi.org/10.1080/1040841X.2021.1876631, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 254–273, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hajj Hussein et al., “Highlights on two decades with microbiota and inflammatory bowel disease from etiology to therapy,” Transpl Immunol, vol. 78, p. 101835, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. E. V. Johansson, H. Sjövall, and G. C. Hansson, “The gastrointestinal mucus system in health and disease,” Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 352–361, 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Sardelli et al., “ Towards bioinspired in vitro models of intestinal mucus ,” RSC Adv, vol. 9, no. 28, pp. 15887–15899, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Lai, Y.-Y. Wang, D. Wirtz, and J. Hanes, “Micro- and macrorheology of mucus,” Adv Drug Deliv Rev, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 86–100, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Boegh, S. G. Baldursdóttir, A. Müllertz, and H. M. Nielsen, “Property profiling of biosimilar mucus in a novel mucus-containing in vitro model for assessment of intestinal drug absorption,” European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, vol. 87, no. 2, pp. 227–235, 2014. [CrossRef]

- König et al., “Human Intestinal Barrier Function in Health and Disease,” Clin Transl Gastroenterol, vol. 7, no. 10, p. e196, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Alatab et al., “The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017,” Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 17–30, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kornbluth and D. B. Sachar, “Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: Practice Parameters Committee,” American Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 99, no. 7, pp. 1371–1385, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Torres, S. Mehandru, J. Colombel, and L. Peyrin-Biroulet, “Crohn’s disease,” The Lancet, vol. 389, no. 10080, pp. 1741–1755, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. Louis, A. Collard, A. F. Oger, E. Degroote, F. Aboul Nasr El Yafi, and J. Belaiche, “Behaviour of Crohn’s disease according to the Vienna classification: Changing pattern over the course of the disease,” Gut, vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 777–782, 2001. [CrossRef]

- H. Wanderås, B. A. Moum, M. L. Høivik, and Ø. Hovde, “Predictive factors for a severe clinical course in ulcerative colitis: Results from population-based studies,” World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther, vol. 7, no. 2, p. 235, 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Abegunde, B. H. Muhammad, O. Bhatti, and T. Ali, “Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases: Evidence based literature review,” World J Gastroenterol, vol. 22, no. 27, pp. 6296–6317, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Mahid, K. S. Minor, R. E. Soto, C. A. Hornung, and S. Galandiuk, “Smoking and inflammatory bowel disease: A meta-analysis,” Mayo Clin Proc, vol. 81, no. 11, pp. 1462–1471, 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. Higuchi, H. Khalili, A. T. Chan, J. M. Richter, A. Bousvaros, and C. S. Fuchs, “A prospective study of cigarette smoking and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease in women,” American Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 107, no. 9, pp. 1399–1406, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Torres, S. Mehandru, J. Colombel, and L. Peyrin-Biroulet, “Crohn’s disease,” The Lancet, vol. 389, no. 10080, pp. 1741–1755, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Le Berre, A. N. Ananthakrishnan, S. Danese, S. Singh, and L. Peyrin-Biroulet, “Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease Have Similar Burden and Goals for Treatment,” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 14–23, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Kennedy, M. Hoper, K. Deodhar, P. J. Erwin, S. J. Kirk, and K. R. Gardiner, “Interleukin 10-deficient colitis: New similarities to human inflammatory bowel disease,” British Journal of Surgery, vol. 87, no. 10, pp. 1346–1351, 2000. [CrossRef]

- S. Bridger, J. C. W. Lee, I. Biarnason, J. E. Lennard Jones, and A. J. Macpherson, “In siblings with similar genetic susceptibility for inflammatory bowel disease, smokers tend to develop Crohn’s disease and non-smokers develop ulcerative colitis,” Gut, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 21–25, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Khor, A. Gardet, and R. J. Xavier, “Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease,” Nature, vol. 474, no. 7351, pp. 307–317, 2011. [CrossRef]

- G. Meng, T. M. Monaghan, N. A. Duggal, P. Tighe, and F. Peerani, “Microbial–Immune Crosstalk in Elderly-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Unchartered Territory,” J Crohns Colitis, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Oriano et al., “The Open Challenge of in vitro Modeling Complex and Multi-Microbial Communities in Three-Dimensional Niches,” Front Bioeng Biotechnol, vol. 8, no. October, pp. 1–17, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Peneda Pacheco, N. Suárez Vargas, S. Visentin, and P. Petrini, “From tissue engineering to engineering tissues: the role and application of in vitro models,” Biomater Sci, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco et al., “Heterogeneity governs 3D-cultures of clinically relevant microbial communities,” Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Sardelli et al., “Bioinspired in vitro intestinal mucus model for 3D-dynamic culture of bacteria,” Biomaterials Advances, vol. 139, p. 213022, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Shroyer and S. A. Kocoshis, “Anatomy and Physiology of the Small and Large Intestines,” in Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, Elsevier Inc., 2011, pp. 324–336. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4377-0774-8.10031-4.

- J. M. Allaire, S. M. Crowley, H. T. Law, S. Y. Chang, H. J. Ko, and B. A. Vallance, “The Intestinal Epithelium: Central Coordinator of Mucosal Immunity,” Trends in Immunology, vol. 39, no. 9. Elsevier Ltd, pp. 677–696, Sep. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.04.002.

- Y. Furusawa et al., “Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells,” Nature, vol. 504, no. 7480, pp. 446–450, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Plitas and A. Y. Rudensky, “Regulatory T cells: Differentiation and function,” Cancer Immunol Res, vol. 4, no. 9, pp. 721–725, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Chávez et al., “Depletion of Butyrate-Producing Clostridia from the Gut Microbiota Drives an Aerobic Luminal Expansion of Salmonella,” Cell Host Microbe, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 443–454, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Rea et al., “Effect of broad- and narrow-spectrum antimicrobials on Clostridium difficile and microbial diversity in a model of the distal colon,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 108, no. SUPPL. 1, pp. 4639–4644, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Kang, “Salsolinol, a catechol neurotoxin, induces oxidative modification of cytochrome c,” BMB Rep, 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Chelakkot, J. Ghim, and S. H. Ryu, “Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications,” Experimental and Molecular Medicine, vol. 50, no. 8. Nature Publishing Group, Aug. 01, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0126-x.

- Zahraoui et al., “A small rab GTPase is distributed in cytoplasmic vesicles in non polarized cells but colocalizes with the tight junction marker ZO-1 in polarized epithelial cells,” Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 124, no. 1–2, pp. 101–115, Jan. 1994. [CrossRef]

- S. Tsukita, K. Oishi, T. Akiyama, Y. Yamanashi, T. Yamamoto, and S. Tsukita, “Specific proto-oncogenic tyrosine kinases of src family are enriched in cell-to-cell adherens junctions where the level of tyrosine phosphorylation is elevated,” Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 113, no. 4, pp. 867–879, May 1991. [CrossRef]

- L. L. Wu et al., “Epithelial inducible nitric oxide synthase causes bacterial translocation by impairment of enterocytic tight junctions via intracellular signals of Rho-associated kinase and protein kinase C zeta,” Crit Care Med, vol. 39, no. 9, pp. 2087–2098, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Zech, I. Pouvreau, A. Cotinet, O. Goureau, B. Le Varlet, and Y. De Kozak, “Effect of cytokines and nitric oxide on tight junctions in cultured rat retinal pigment epithelium,” Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, vol. 39, no. 9, pp. 1600–1608, 1998.

- C. T. Capaldo et al., “Proinflammatory cytokine-induced tight junction remodeling through dynamic self-assembly of claudins,” Mol Biol Cell, vol. 25, no. 18, pp. 2710–2719, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- W. Fries, C. Muja, C. Crisafulli, S. Cuzzocrea, and E. Mazzon, “Dynamics of enterocyte tight junctions: Effect of experimental colitis and two different anti-TNF strategies,” Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, vol. 294, no. 4, pp. 938–947, 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Reimund et al., “Increased production of tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-6 by morphologically normal intestinal biopsies from patients with Crohn’s disease,” Gut, vol. 39, no. 5, pp. 684–689, 1996. [CrossRef]

- M. Marchiando et al., “Caveolin-1-dependent occludin endocytosis is required for TNF-induced tight junction regulation in vivo,” Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 189, no. 1, pp. 111–126, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Cheng, J. Wang, M. Hao, and H. Che, “Antibiotic-Induced Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Damages the Intestinal Barrier, Increasing Food Allergy in Adult Mice,” Nutrients 2021, Vol. 13, Page 3315, vol. 13, no. 10, p. 3315, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kolios, V. Valatas, and S. G. Ward, “Nitric oxide in inflammatory bowel disease: A universal messenger in an unsolved puzzle,” Immunology, vol. 113, no. 4. Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 427–437, Dec. 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01984.x.

- T. Katsube, H. Tsuji, and M. Onoda, “Nitric oxide attenuates hydrogen peroxide-induced barrier disruption and protein tyrosine phosphorylation in monolayers of intestinal epithelial cell,” Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res, vol. 1773, no. 6, pp. 794–803, Jun. 2007. [CrossRef]

- G. Kolios, N. Rooney, C. T. Murphy, D. A. F. Robertson, and J. Westwick, “Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase activity in human colon epithelial cells: Modulation by T lymphocyte derived cytokines,” Gut, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 56–63, 1998. [CrossRef]

- E. Rinninella et al., “What is the healthy gut microbiota composition? A changing ecosystem across age, environment, diet, and diseases,” Microorganisms, vol. 7, no. 1, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Carroll, Y. H. Chang, J. Park, R. B. Sartor, and Y. Ringel, “Luminal and mucosal-associated intestinal microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome,” Gut Pathog, vol. 2, no. 1, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Pickard, M. Y. Zeng, R. Caruso, and G. Núñez, “Gut Microbiota: Role in Pathogen Colonization, Immune Responses and Inflammatory Disease”. [CrossRef]

- Spencer and M. Bemark, “Human intestinal B cells in inflammatory diseases,” Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2023 20:4, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 254–265, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Dasgupta, D. Erturk-Hasdemir, J. Ochoa-Reparaz, H.-C. Reinecker, and D. L. Kasper, “Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Mediate Anti-inflammatory Responses to a Gut Commensal Molecule via Both Innate and Adaptive Mechanisms,” Cell Host Microbe, vol. 15, pp. 413–423, 2014. [CrossRef]

- H.-Y. Cheng, M.-X. Ning, D.-K. Chen, and W.-T. Ma, “Interactions Between the Gut Microbiota and the Host Innate Immune Response Against Pathogens.,” Front Immunol, vol. 10, p. 607, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Coretti et al., “The Interplay between Defensins and Microbiota in Crohn’s Disease,” Mediators Inflamm, vol. 2017, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Ayabe, D. P. Satchell, C. L. Wilson, W. C. Parks, M. E. Selsted, and A. J. Ouellette, “Secretion of microbicidal α-defensins by intestinal Paneth cells in response to bacteria,” Nat Immunol, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 113–118, Aug. 2000. [CrossRef]

- J. Fernandes, W. Su, S. Rahat-Rozenbloom, T. M. S. Wolever, and E. M. Comelli, “Adiposity, gut microbiota and faecal short chain fatty acids are linked in adult humans,” Nutr Diabetes, vol. 4, no. JUNE, 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Wongsurawat et al., “Microbiome analysis of thai traditional fermented soybeans reveals short-chain fatty acid-associated bacterial taxa,” Scientific Reports 2023 13:1, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–10, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun et al., “Effect of short-chain fatty acids on triacylglycerol accumulation, lipid droplet formation and lipogenic gene expression in goat mammary epithelial cells,” Animal Science Journal, vol. 87, no. 2, pp. 242–249, 2016. [CrossRef]

- W. Ratajczak, A. Rył, A. Mizerski, K. Walczakiewicz, O. Sipak, and M. Laszczyńska, “Immunomodulatory potential of gut microbiome-derived shortchain fatty acids (SCFAs),” Acta Biochimica Polonica, vol. 66, no. 1. Acta Biochimica Polonica, pp. 1–12, Mar. 04, 2019. doi: 10.18388/abp.2018_2648.

- Sardelli et al., “ Towards bioinspired in vitro models of intestinal mucus ,” RSC Adv, vol. 9, no. 28, pp. 15887–15899, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. N. Frank, A. L. St. Amand, R. A. Feldman, E. C. Boedeker, N. Harpaz, and N. R. Pace, “Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 104, no. 34, pp. 13780–13785, Aug. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Gilbert et al., “Microbiome-wide association studies link dynamic microbial consortia to disease,” Nature, vol. 535, no. 7610. Nature Publishing Group, pp. 94–103, Jul. 06, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nature18850.

- F. Fava and S. Danese, “Intestinal microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease: Friend of foe?,” World J Gastroenterol, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 557–566, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Bien, V. Palagani, and P. Bozko, “The intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and Clostridium difficile infection: Is there a relationship with inflammatory bowel disease?,” Therap Adv Gastroenterol, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 53–68, 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Rigottier-Gois, “Dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel diseases: The oxygen hypothesis,” ISME Journal, vol. 7, no. 7, pp. 1256–1261, 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Cook et al., “Analysis of Flagellin-Specific Adaptive Immunity Reveals Links to Dysbiosis in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease,” Cmgh, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 485–506, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. P. Tamboli, “Dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease,” Gut, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 1–4, Jan. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Hajj Hussein et al., “Highlights on two decades with microbiota and inflammatory bowel disease from etiology to therapy,” Transpl Immunol, vol. 78, p. 101835, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhou et al., “Programmable probiotics modulate inflammation and gut microbiota for inflammatory bowel disease treatment after effective oral delivery,” Nature Communications 2022 13:1, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–14, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Porcari et al., “Fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent C. difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” J Autoimmun, p. 103036, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Basso, N. O. Saraiva Câmara, and H. Sales-Campos, “Microbial-based therapies in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease – An overview of human studies,” Front Pharmacol, vol. 9, no. JAN, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kellermayer, “Fecal microbiota transplantation: Great potential with many challenges,” Translational Gastroenterology and Hepatology, vol. 4, no. May. AME Publishing Company, 2019. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2019.05.10.

- X. Guo, X. Liu, and J. Hao, Gut Microbiota in Ulcerative Colitis: Insights on Pathogenesis and Treatment. 2020. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12849.

- Z. Shen et al., “Update on intestinal microbiota in Crohn’s disease 2017: Mechanisms, clinical application, adverse reactions, and outlook.,” J Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 32, no. 11, pp. 1804–1812, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Paramsothy et al., “Faecal microbiota transplantation for inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” J Crohns Colitis, vol. 11, no. 10, pp. 1180–1199, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. P. Vaughn et al., “Increased Intestinal Microbial Diversity Following Fecal Microbiota Transplant for Active Crohn’s Disease,” Inflamm Bowel Dis, vol. 22, no. 9, pp. 2182–2190, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Joossens et al., “Dysbiosis of the faecal microbiota in patients with Crohn’s disease and their unaffected relatives,” Gut, vol. 60, no. 5, pp. 631–637, May 2011. [CrossRef]

- Machiels et al., “A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis.,” Gut, vol. 63, no. 8, pp. 1275–83, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Björkqvist et al., “Alterations in the relative abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii correlate with changes in fecal calprotectin in patients with ileal Crohn’s disease: a longitudinal study,” Scand J Gastroenterol, vol. 54, no. 5, pp. 577–585, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Ricciardi, J. W. Ogilvie, P. L. Roberts, P. W. Marcello, T. W. Concannon, and N. N. Baxter, “Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile Colitis in Hospitalized Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases,” Dis Colon Rectum, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 40–45, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. WEHKAMP and E. F. STANGE, “A New Look at Crohn’s Disease: Breakdown of the Mucosal Antibacterial Defense,” Ann N Y Acad Sci, vol. 1072, no. 1, pp. 321–331, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Shoaei et al., “Clostridium difficile isolated from faecal samples in patients with ulcerative colitis,” BMC Infect Dis, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 361, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Bansil and B. S. Turner, “Mucin structure, aggregation, physiological functions and biomedical applications,” Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci, vol. 11, no. 2–3, pp. 164–170, 2006. [CrossRef]

- E. V Johansson, K. A. Thomsson, and G. C. Hansson, “Proteomic analyses of the two mucus layers of the colon barrier reveal that their main component, the Muc2 mucin, is strongly bound to the fcgbp protein,” J Proteome Res, vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 3549–3557, 2009. [CrossRef]

- K. Godl et al., “The N Terminus of the MUC2 Mucin Forms Trimers That Are Held Together within a Trypsin-resistant Core Fragment,” Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 277, no. 49, pp. 47248–47256, Dec. 2002. [CrossRef]

- C. Butnarasu et al., “Mucosomes: Intrinsically Mucoadhesive Glycosylated Mucin Nanoparticles as Multi-Drug Delivery Platform,” Adv Healthc Mater, vol. 11, no. 15, p. 2200340, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. V Johansson, J. M. H. Larsson, and G. C. Hansson, “The two mucus layers of colon are organized by the MUC2 mucin, whereas the outer layer is a legislator of host-microbial interactions,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 108, no. Supplement_1, pp. 4659–4665, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Pearson, P. I. Chater, and M. D. Wilcox, “The properties of the mucus barrier, a unique gel – how can nanoparticles cross it?,” Ther Deliv, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 229–244, 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. ROBBE, C. CAPON, B. CODDEVILLE, and J.-C. MICHALSKI, “Structural diversity and specific distribution of O-glycans in normal human mucins along the intestinal tract,” Biochemical Journal, vol. 384, no. 2, pp. 307–316, 2004. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Hattrup and S. J. Gendler, “Structure and Function of the Cell Surface (Tethered) Mucins,” Annu Rev Physiol, vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 431–457, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- D. Ambort, M. E. V. Johansson, J. K. Gustafsson, A. Ermund, and G. C. Hansson, “Perspectives on Mucus Properties and Formation--Lessons from the Biochemical World,” Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, vol. 2, no. 11, pp. a014159–a014159, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Leal, H. D. C. Smyth, and D. Ghosh, “Physicochemical properties of mucus and their impact on transmucosal drug delivery,” Int J Pharm, vol. 532, no. 1, pp. 555–572, 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. Dorofeyev, I. V. Vasilenko, O. A. Rassokhina, and R. B. Kondratiuk, “Mucosal barrier in ulcerative colitis and crohn’s disease,” Gastroenterol Res Pract, vol. 2013, no. Cd, 2013. [CrossRef]

- E. V. Johansson et al., “Bacteria penetrate the normally impenetrable inner colon mucus layer in both murine colitis models and patients with ulcerative colitis,” Gut, vol. 63, no. 2, pp. 281–291, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Post et al., “Structural weakening of the colonic mucus barrier is an early event in ulcerative colitis pathogenesis,” pp. 1–10, 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Dorofeyev, I. V. Vasilenko, O. A. Rassokhina, and R. B. Kondratiuk, “Mucosal barrier in ulcerative colitis and crohn’s disease,” Gastroenterol Res Pract, vol. 2013, no. Cd, 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Podolsky and K. J. Isselbacher, “Composition of human colonic mucin. Selective alteration in inflammatory bowel disease,” Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 142–153, 1983. [CrossRef]

- Xia et al., “Cell membrane-anchored MUC4 promotes tumorigenicity in epithelial carcinomas,” Oncotarget, vol. 8, no. 8, pp. 14147–14157, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. I. Nonose, A. I. Paula Pimentel Spadari, D. Gonçalves Priolli III, F. I. Rodrigues Máximo, J. I. Aires Pereira, and C. V Augusto Real Martinez, “Tissue quantification of neutral and acid mucins in the mucosa of the colon with and without fecal stream in rats Quantificação tecidual de mucinas neutras e ácidas na mucosa do cólon com e sem trânsito intestinal em ratos,” Acta Cir Bras, vol. 24, no. 244, pp. 2009–268, 2009.

- S. Agawa, T. Muto, and Y. Morioka, “Mucin abnormality of colonic mucosa in ulcerative colitis associated with carcinoma and/or dysplasia,” Dis Colon Rectum, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 387–389, 1988. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Tsai, A. D. Dwarakanath, C. A. Hart, J. D. Milton, and J. M. Rhodes, “Increased faecal mucin sulphatase activity in ulcerative colitis: A potential target for treatment,” Gut, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 570–576, 1995. [CrossRef]

- N. Mian, C. E. Anderson, and P. W. Kent, “Effect of O-sulphate groups in lactose and N-acetylneuraminyl-lactose on their enzymic hydrolysis.,” Biochem J, vol. 181, no. 2, pp. 387–399, 1979. [CrossRef]

- J. M. H. Larsson et al., “Altered O-glycosylation profile of MUC2 mucin occurs in active ulcerative colitis and is associated with increased inflammation,” Inflamm Bowel Dis, vol. 17, no. 11, pp. 2299–2307, 2011. [CrossRef]

- G. Lennon et al., “Correlations between colonic crypt mucin chemotype, inflammatory grade and Desulfovibrio species in ulcerative colitis,” Colorectal Disease, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 161–169, 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Atreya and M. F. Neurath, “IBD pathogenesis in 2014 : Molecular pathways controlling barrier function in IBD,” Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 37–38, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Braun et al., “Alterations of phospholipid concentration and species composition of the intestinal mucus barrier in ulcerative colitis: A clue to pathogenesis,” Inflamm Bowel Dis, vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 1705–1720, 2009. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Greer, A. Morgun, and N. Shulzhenko, “Bridging immunity and lipid metabolism by gut microbiota,” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, vol. 132, no. 2, pp. 253–262, 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Caesar, V. Tremaroli, P. Kovatcheva-Datchary, P. D. Cani, and F. Bäckhed, “Crosstalk between gut microbiota and dietary lipids aggravates WAT inflammation through TLR signaling,” Cell Metab, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 658–668, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Øgaard Mønsted et al., “Reduced phosphatidylcholine level in the intestinal mucus layer of prediabetic NOD mice,” APMIS, vol. 131, no. 6, pp. 237–248, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Lichtenberger, “The Hydrophobic Barrier Properties of Gastrointestinal Mucus,” Annu Rev Physiol, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 565–583, Oct. 1995. [CrossRef]

- R. Ehehalt et al., “Phosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylcholine in intestinal mucus of ulcerative colitis patients. A quantitative approach by nanoElectrospray-tandem mass spectrometry.,” Scand J Gastroenterol, vol. 39, no. 8, pp. 737–42, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Rosenberg and S. Kjelleberg, “Hydrophobic Interactions: Role in Bacterial Adhesion,” pp. 353–393, 1986. [CrossRef]

- Braun et al., “Reduced hydrophobicity of the colonic mucosal surface in ulcerative colitis as a hint at a physicochemical barrier defect,” Int J Colorectal Dis, vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 989–998, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Diab et al., “Lipidomics in Ulcerative Colitis Reveal Alteration in Mucosal Lipid Composition Associated With the Disease State,” Inflamm Bowel Dis, vol. XX, no. Xx, pp. 1–8, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Almer, L. Franzén, G. Olaison, K. Smedh, and M. Ström, “Phospholipase a<inf>2</inf> activity of colonic mucosa in patients with ulcerative colitis,” Digestion, vol. 50, no. 3–4, pp. 135–141, 1991. [CrossRef]

- W. Stremmel, A. H. Robert, E. M. Karner, and A. Braun, “Phosphatidylcholine (Lecithin) and the mucus layer: Evidence of therapeutic efficacy in ulcerative colitis?,” Digestive Diseases, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 490–496, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Braun et al., “Alterations of phospholipid concentration and species composition of the intestinal mucus barrier in ulcerative colitis: A clue to pathogenesis,” Inflamm Bowel Dis, vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 1705–1720, 2009. [CrossRef]

- R. Ehehalt et al., “Phosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylcholine in intestinal mucus of ulcerative colitis patients. A quantitative approach by nanoelectrospray-tandem mass spectrometry,” Scand J Gastroenterol, vol. 39, no. 8, pp. 737–742, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Paone and P. D. Cani, “Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota: the expected slimy partners?,” Gut, vol. 69, no. 12, pp. 2232–2243, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. K. Gustafsson, A. Ermund, M. E. V. Johansson, A. Schutte, G. C. Hansson, and H. Sjovall, “An ex vivo method for studying mucus formation, properties, and thickness in human colonic biopsies and mouse small and large intestinal explants,” AJP: Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, vol. 302, no. 4, pp. G430–G438, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. E. V. Johansson, H. Sjövall, and G. C. Hansson, “The gastrointestinal mucus system in health and disease,” Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 352–361, 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. Pullan et al., “Thickness of adherent mucus gel on colonic mucosa in humans and its relevance to colitis.,” Gut, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 353–359, 1994. [CrossRef]

- Swidsinski et al., “Comparative study of the intestinal mucus barrier in normal and inflamed colon,” Gut, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 343–350, 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. Pullan et al., “Thickness of adherent mucus gel on colonic mucosa in humans and its relevance to colitis.,” Gut, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 353–359, 1994. [CrossRef]

- K. Fyderek et al., “Mucosal bacterial microflora and mucus layer thickness in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease,” World J Gastroenterol, vol. 15, no. 42, pp. 5287–5294, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Strugala, P. W. Dettmar, and J. P. Pearson, “Thickness and continuity of the adherent colonic mucus barrier in active and quiescent ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease,” Int J Clin Pract, vol. 62, no. 5, pp. 762–769, 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. Fyderek et al., “Mucosal bacterial microflora and mucus layer thickness in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease,” World J Gastroenterol, vol. 15, no. 42, pp. 5287–5294, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Strugala, P. W. Dettmar, and J. P. Pearson, “Thickness and continuity of the adherent colonic mucus barrier in active and quiescent ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease,” Int J Clin Pract, vol. 62, no. 5, pp. 762–769, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Swidsinski et al., “Comparative study of the intestinal mucus barrier in normal and inflamed colon,” Gut, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 343–350, 2007. [CrossRef]

- L. Sardelli et al., “ Towards bioinspired in vitro models of intestinal mucus ,” RSC Adv, vol. 9, no. 28, pp. 15887–15899, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Schreiber et al., “iNOS-dependent increase in colonic mucus thickness in DSS-colitic rats.,” PLoS One, vol. 8, no. 8, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. E. V. Johansson et al., “Bacteria penetrate the normally impenetrable inner colon mucus layer in both murine colitis models and patients with ulcerative colitis,” Gut, vol. 63, no. 2, pp. 281–291, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. Pullan et al., “in Humans and Its Relevance To Colitis,” Gut, pp. 353–359, 1994.

- K. Fyderek et al., “Mucosal bacterial microflora and mucus layer thickness in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease,” World J Gastroenterol, vol. 15, no. 42, pp. 5287–5294, 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. Ambort et al., “Calcium and pH-dependent packing and release of the gel-forming MUC2 mucin,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 109, no. 15, pp. 5645–5650, 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. Bischoff et al., “Intestinal permeability - a new target for disease prevention and therapy,” BMC Gastroenterol, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–25, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Michielan and R. D’Incà, “Intestinal Permeability in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pathogenesis, Clinical Evaluation, and Therapy of Leaky Gut,” Mediators Inflamm, vol. 2015, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Rao et al., “Urine sugars for in vivo gut permeability: Validation and comparisons in irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea and controls,” Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, vol. 301, no. 5, p. G919, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Halme, U. Turunen, J. Tuominen, T. Forsström, and U. Turpeinen, “Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation Comparison of iohexol and lactulose-mannitol tests as markers of disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease,” 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Prager et al., “Myosin IXb variants and their pivotal role in maintaining the intestinal barrier: A study in Crohn’s disease,” Scand J Gastroenterol, vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 1191–1200, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Bischoff et al., “Intestinal permeability - a new target for disease prevention and therapy,” BMC Gastroenterol, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–25, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Almer, L. Franzen, G. Olaison, K. Smedh, and M. Strom, “Increased absorption of polyethylene glycol 600 deposited in the colon in active ulcerative colitis,” Gut, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 509–513, 1993. [CrossRef]

- J. Z. H. Von Martels, A. R. Bourgonje, H. J. M. Harmsen, K. N. Faber, and G. Dijkstra, “Assessing intestinal permeability in Crohn’s disease patients using orally administered 52 Cr-EDTA,” PLoS One, vol. 14, no. 2, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. N. S. Gregson, A. Steel, M. Bower, B. G. Gazzard, F. M. Gotch, and M. R. Goodier, “Elevated plasma lipopolysaccharide is not sufficient to drive natural killer cell activation in HIV-1-infected individuals,” AIDS, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 29–34, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. Pasternak et al., “Lipopolysaccharide exposure is linked to activation of the acute phase response and growth failure in pediatric Crohn’s disease and murine colitis,” Inflamm Bowel Dis, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 856–869, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. M. McQuade et al., “Gastrointestinal consequences of lipopolysaccharide-induced lung inflammation,” Inflammation Research, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 57–74, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Ferrer-Picón et al., “Intestinal Inflammation Modulates the Epithelial Response to Butyrate in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease,” Inflamm Bowel Dis, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 43–55, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Thuijls et al., “Urine-based Detection of Intestinal Tight Junction Loss,” J Clin Gastroenterol, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. e14–e19, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- G. Thuijls et al., “Urine-based Detection of Intestinal Tight Junction Loss,” J Clin Gastroenterol, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. e14–e19, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Michielan and R. D’Incà, “Intestinal Permeability in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pathogenesis, Clinical Evaluation, and Therapy of Leaky Gut,” Mediators Inflamm, vol. 2015, 2015. [CrossRef]

- G. D. De Palma and A. Rispo, “Confocal laser endomicroscopy in inflammatory bowel diseases: Dream or reality?,” World Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 19, no. 34. Baishideng Publishing Group Inc, pp. 5593–5597, Sep. 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5593.

- Thomson et al., “The Ussing chamber system for measuring intestinal permeability in health and disease,” BMC Gastroenterol, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 98, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Lautenschläger, C. Schmidt, C. M. Lehr, D. Fischer, and A. Stallmach, “PEG-functionalized microparticles selectively target inflamed mucosa in inflammatory bowel disease,” European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, vol. 85, no. 3 PART A, pp. 578–586, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

| Decrease | Increase | Dysbiosis impact | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chron’s disease | Actinobacteria Bifidobacterium adolescentis Bacteroidetes Bacteroides fragilis Firmicutes Fecalibacterium Praustnizii Eubacterium spp. Lachnospiraceae Clostridium prausnitzii Roseburia spp. Ruminococcus spp. Dialister invisus |

Actinobacteria Bifidobacteriaceae Coriobacteriaceae Firmicutes Ruminococcus gnavus Clostridium difficile Proteobacteria Escherichia coli |

Reduction of defensins production by Paneth cells Lower level of SCFAs Gut inflammation |

[62,69,70,82,85,86,87,88] |

| Ulcerative colitis | Firmicutes Roseburia hominis Fecalibacterium Praustnizii Clostridium Enterococcus Proteobacteria Escherichia coli |

Firmicutes Clostridium difficile |

Reduction of defensins production by Paneth cells Lower level of SCFAs Gut inflammation |

[81,86,89,90] |

.

.| HEALTHY | CD | UC | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

LPC mean value [pmol/100 µg protein] |

4371 ± 487 | 2961 ± 287 | 1738 ± 288 |

|

PC mean value [pmol/100 µg protein] |

2983 ± 321 | 2508 ± 415 | 676 ± 104 |

| % of LPC / protein | 2.22% ± 0.25% | 1.50% ± 0.15% | 0.88% ± 0.15% |

| % of PC / protein | 2.30% ± 0.25% | 1.94% ± 0.32% | 0.52% ± 0.08% |

| LPC/PC | 1.45 ± 0.32 | 1.18 ± 0.31 | 2.57 ± 0.84 |

| Right colon/caecum | Left colon/ Sigmoid | Rectum | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | 107 ± 48 | 134 ± 68 | 155 ± 54 | [141] |

| N/A | 218 ± 81.07 | N/A | [142] | |

| N/A | 450 ± 70 | N/A | [143] | |

| UC | N/A | 83 ± 49.93 | N/A | [142] |

| 90 ± 79 | 43 ± 45 | 60 ± 86 | [141] | |

| CD | 190 ± 83 | 232 ± 40 | 294 ± 45 | [141] |

| N/A | 74 ± 40 | N/A | [142] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).