Submitted:

26 May 2023

Posted:

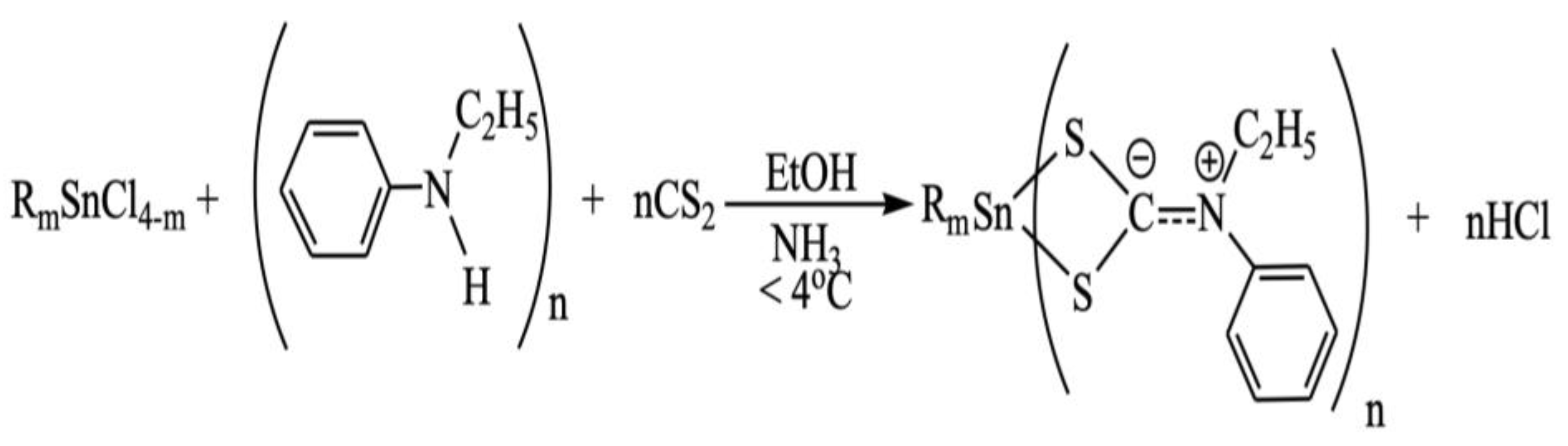

26 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

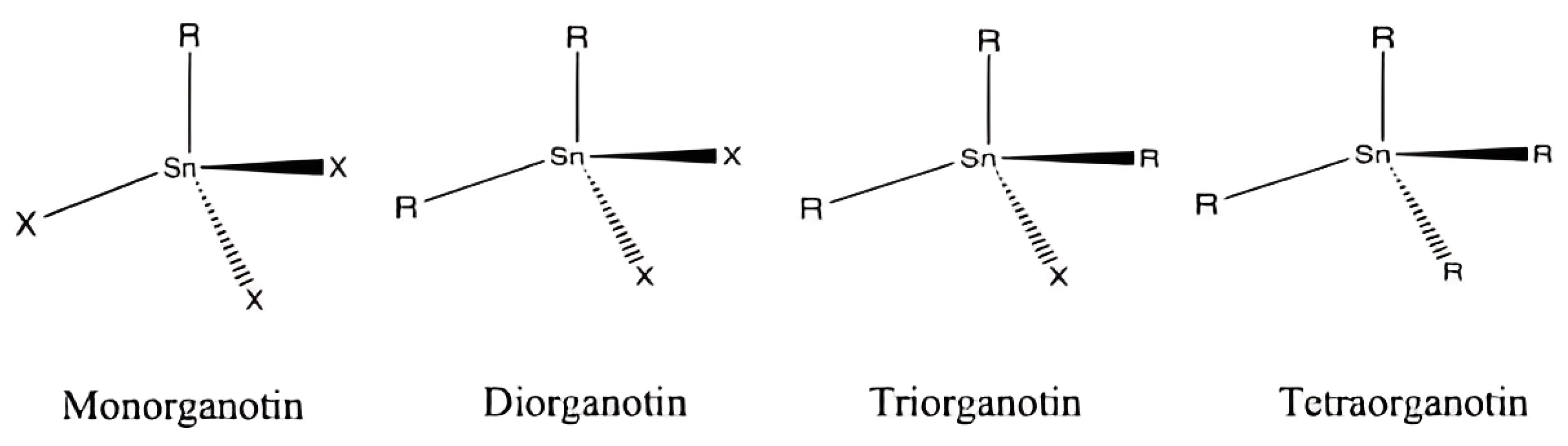

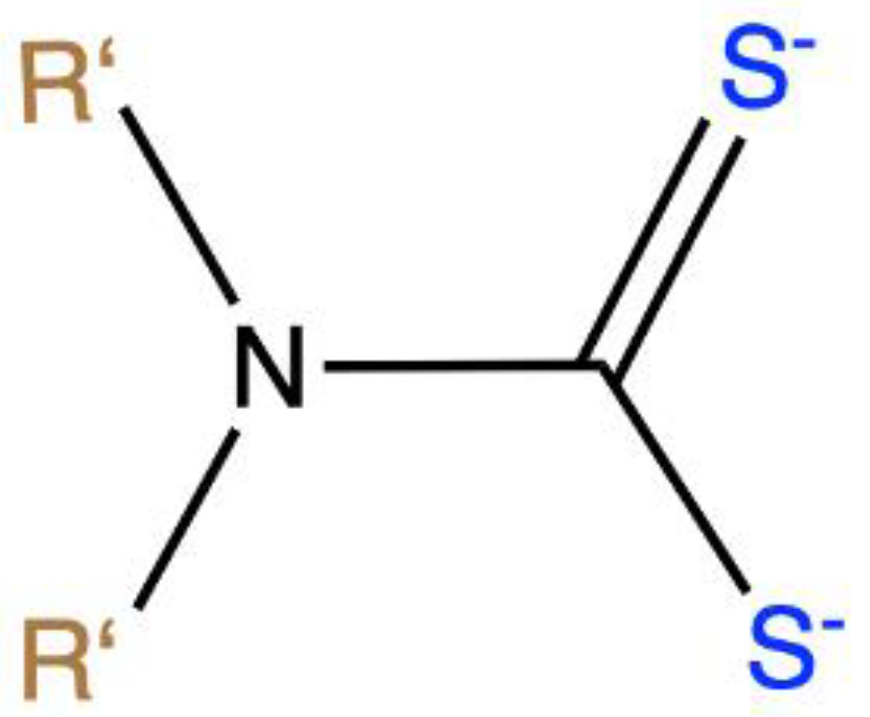

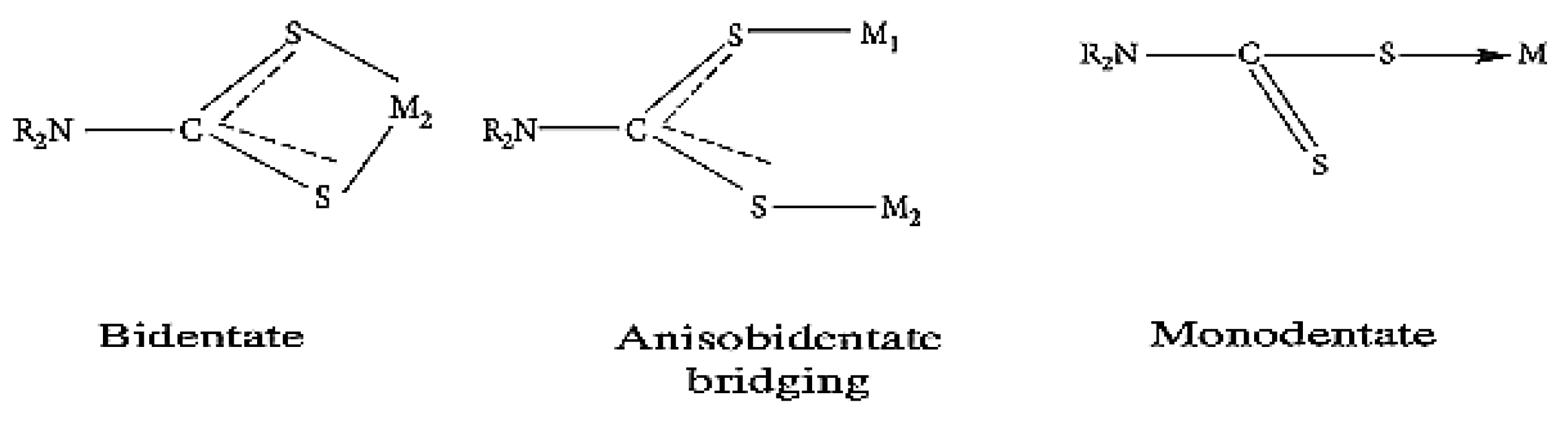

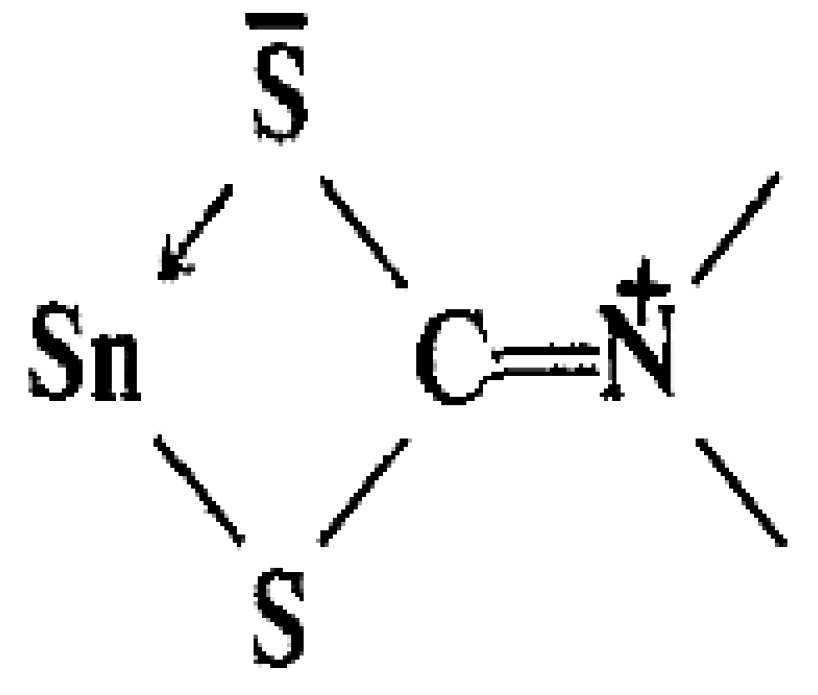

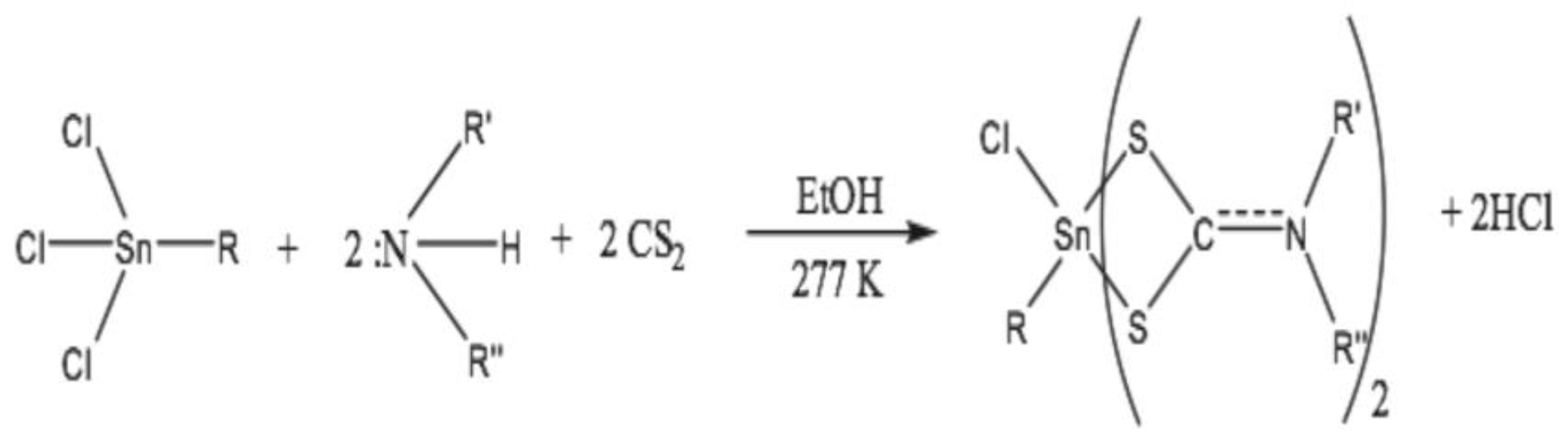

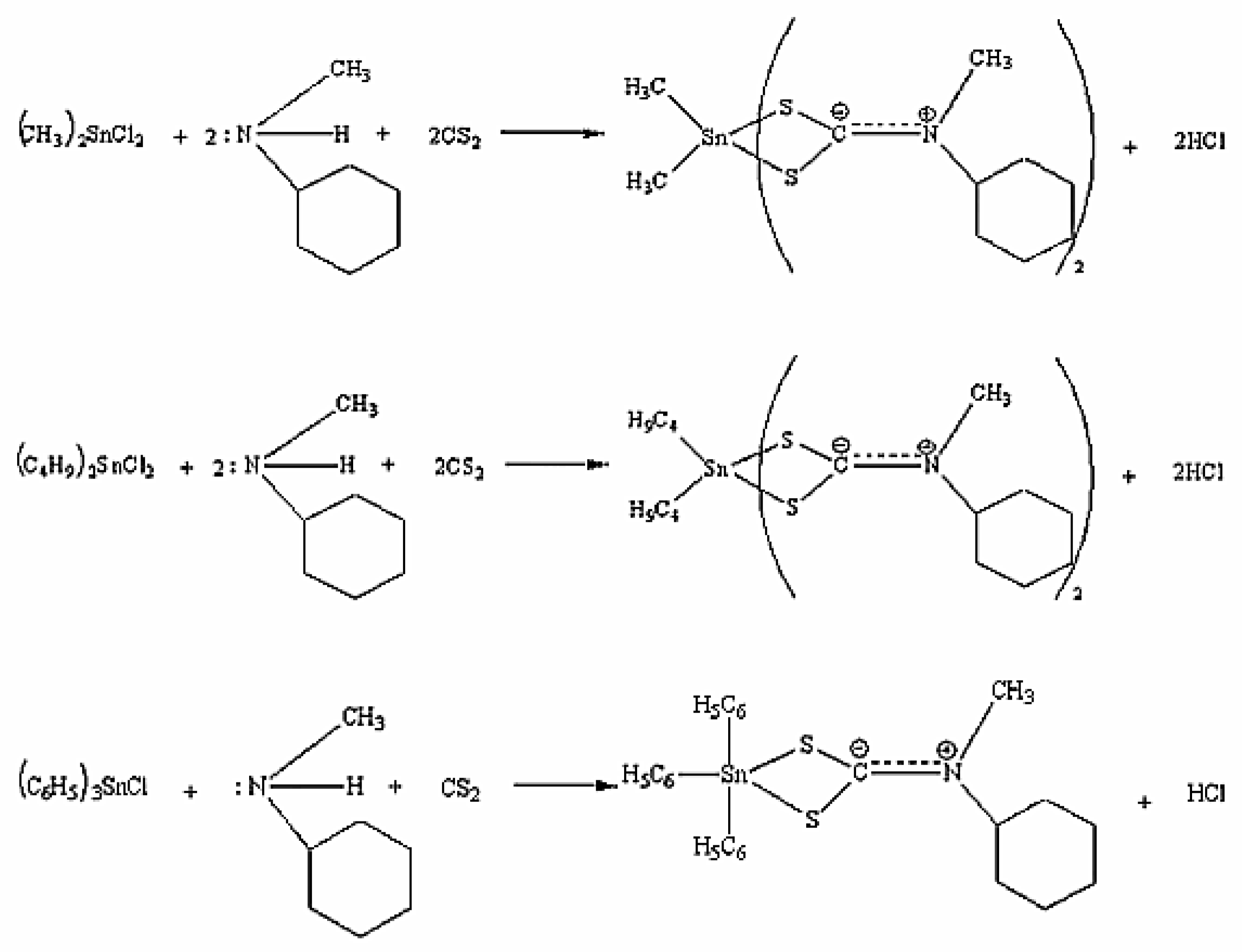

2. Background Chemistry of Organotin(IV) Dithiocarbamate

3. Synthesis of Organotin(IV) Dithiocarbamate

4. Characterization of Organotin(IV) Dithiocarbamate.

4.1. Elemental Analysis of Organotin(IV) Dithiocarbamate (CHNS)

4.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

| Compounds | ν(C---N) | ν(C---S) | ν(Sn-C) | ν(Sn-S) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (CH3)2Sn[S2CN(C7H7)(iC3H7)]2 | 1444 | 997 | - | 377 | [98] |

| (C4H9)2Sn[S2CN(C7H7)(iC3H7)]2 | 1427 | 956 | - | 355 | |

| (CH3)2Sn[S2CN(CH3) (C6H11)]2 | 1475 | 974 | 554 | 357 | [66] |

| (C4H9)2Sn[S2CN(CH3) (C6H11)]2 | 1459 | 975 | 532 | 359 | |

| (C6H5)3 Sn[S2CN(CH3) (C6H11)] | 1478 | 979 | 261 | 349 | |

| (C4H9)2Sn[S2CN(CH3)(C6H11)]2 | 1478 | 979 | - | 375 | [57] |

| (C4H9)2Sn[S2CN(iC3H7)(C6H11)]2 | 1479 | 978 | - | 389 | |

| (C4H9)2Sn[S2CN(C4H9)(C6H5)]2 | 1487.42 | 951.14 | 567.97 | - | [45] |

| (C6H5)2Sn[S2CN(C4H9)(C6H5)]2 | 1457.81 | 996.86 | 258.69 | - | |

| (C6H5)ClSn[S2CN(CH3)(C2H5) ]2 | 1511 | 997,957 | - | 318 | [75] |

| (CH3)ClSn[S2CN(CH3)(C2H5)] 2 | 1519 | 995, 957 | - | 349 | |

| (C4H9)2Sn[S2CN(C2H5)(C6H5)]2 | 1488.72 | 1003.50 | 554.14 | 385.96 | [54] |

| (C6H5)2Sn[S2CN(C2H5)(C6H5)]2 | 1490.73 | 1000.62 | 256.21 | 390.23 | |

| (C6H5)3Sn[S2CN(C2H5)(C6H5)] | 1478.64 | 996.50 | 261.09 | 384.06 | |

| Bu2Sn[C16H34NCS2]2 | 1464 | 1025,963 | 563 | 412 | [99] |

| Ph3SnS2CNC5H12 | 1497 | 983 | 605, 567 | 445 | |

| C20H26N2S4Sn | 1461 | 1006 | 551 | 450 | [69] |

| C26H38N2S4Sn | 1488 | 1020 | 553 | 447 | |

| C30H30N2S4Sn | 1462 | 1003 | 552 | 444 | |

| (CH3)2Sn(L)2 | 1503 | 981 | 507 | 451 | [44] |

| (C4H9)2Sn(L)2 | 1487 | 1008 | 512 | 440 | |

| (C6H5)2Sn(L)2 | 1478 | 996 | 510 | 443 | |

| (C6H5)2Sn[S2CN(C3H5)2]2 | 1475.54 | 977.91 | 545.85 | 441.70 | [35] |

| (C6H5)3Sn[S2CN(C3H5)2] | 1479.40 | 972.12 | 555.50 | 445.56 |

4.3. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy

- 1H NMR spectroscopy

- 2.

- 13c NMR spectroscopy

- 3.

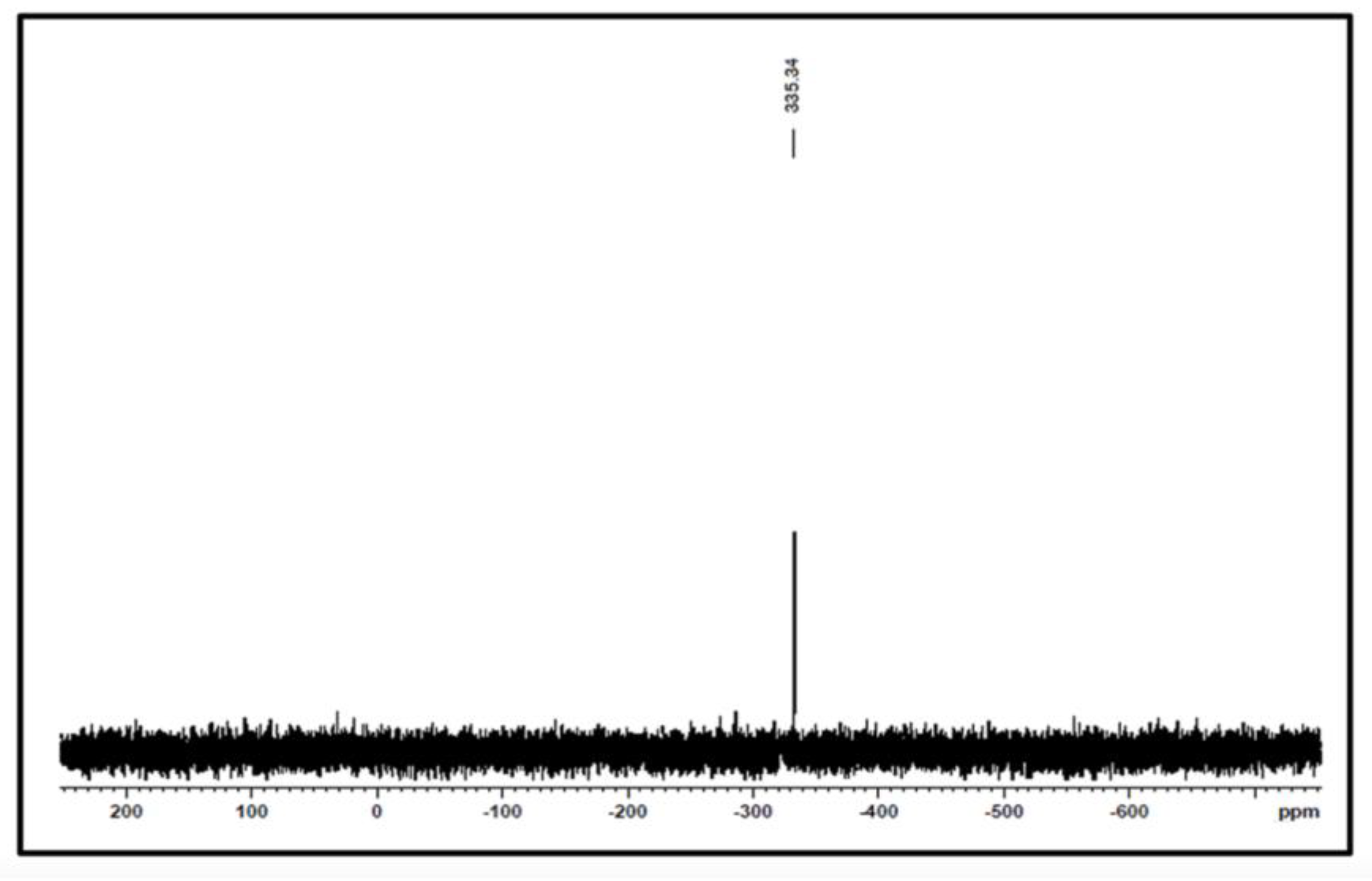

- 119Sn NMR spectroscopy

- Four-coordinate compounds (δ = 200 to -60 ppm): Distorted Tetrahedral structure

- Five-coordinate compounds (δ = -90 to -190 ppm): Distorted Trigonal-bipyramidal structure

- Six-coordinate compounds (δ = -210 to -400 ppm): Distorted Octahedral structure

- Seven-coordinate compounds (δ = -338 to -446 ppm): Distorted Pentagonal bipyramidal structure

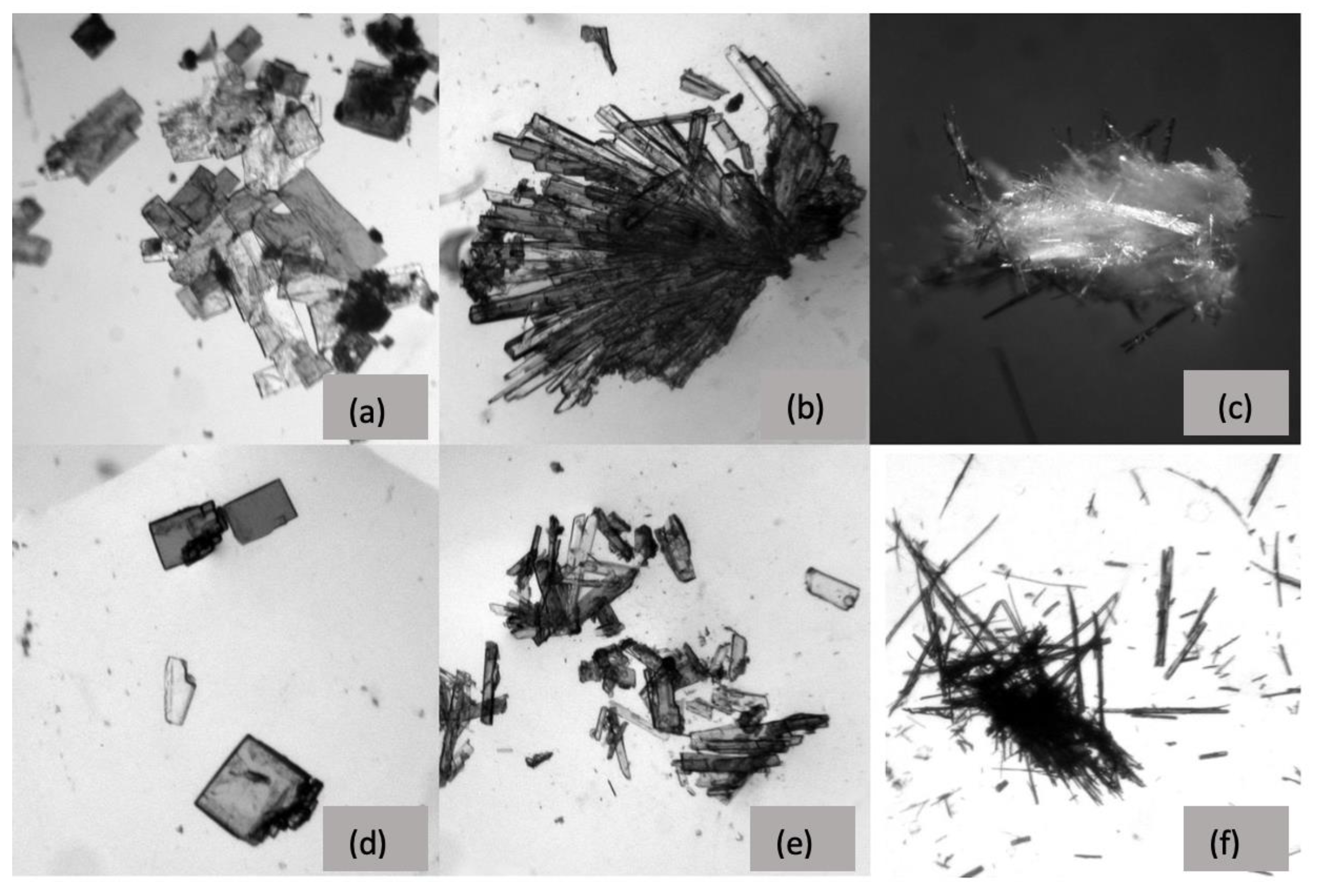

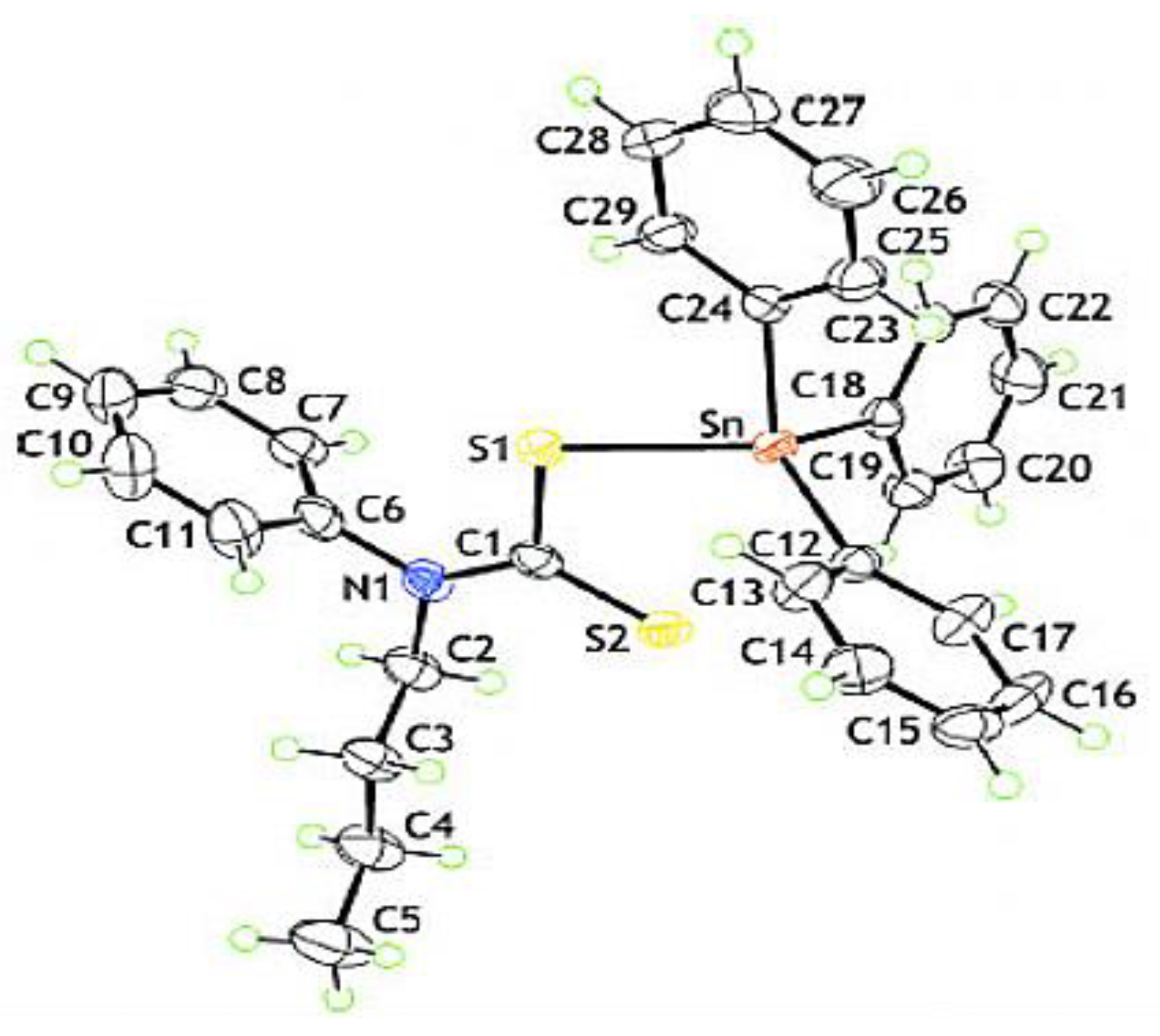

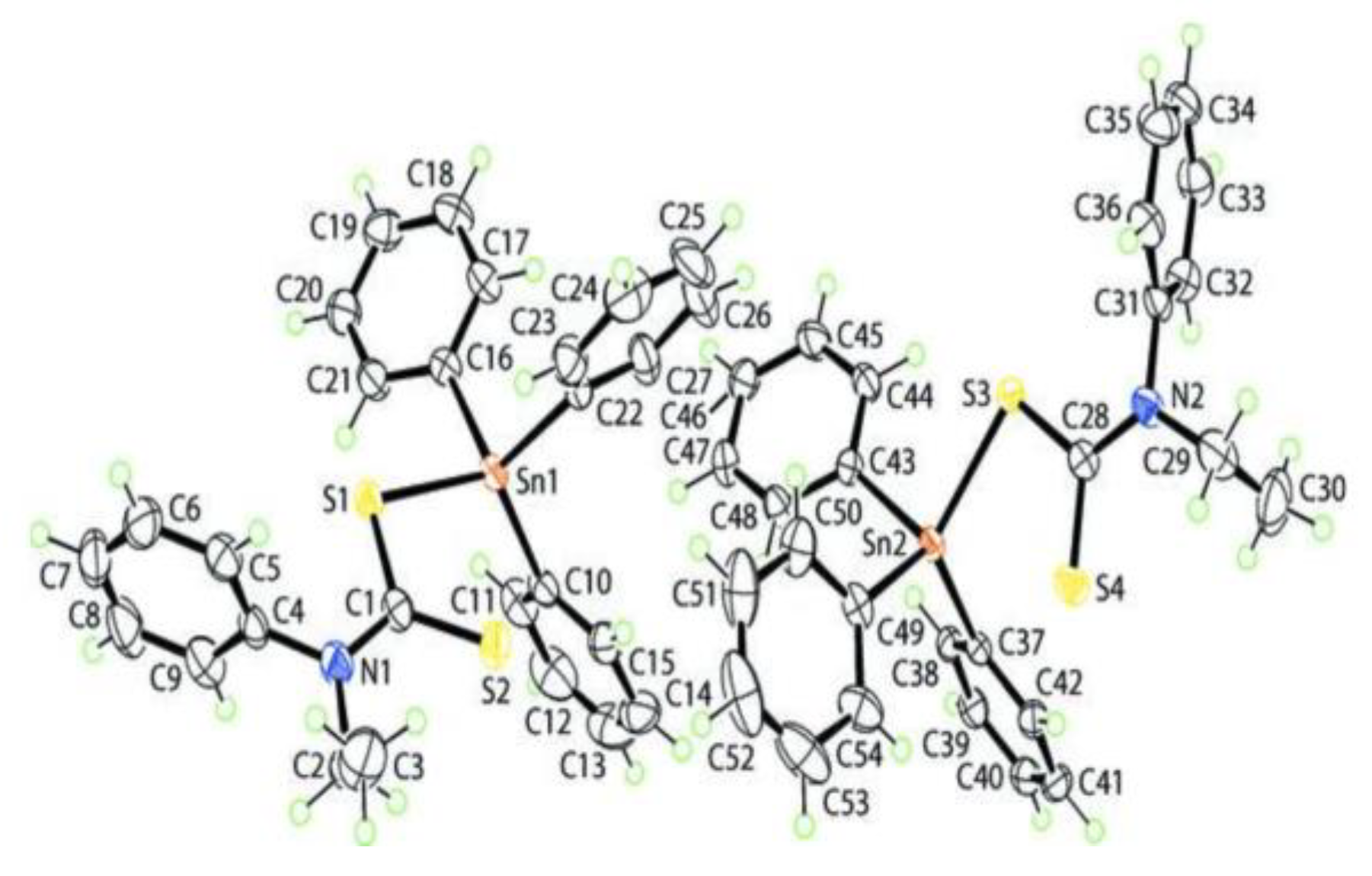

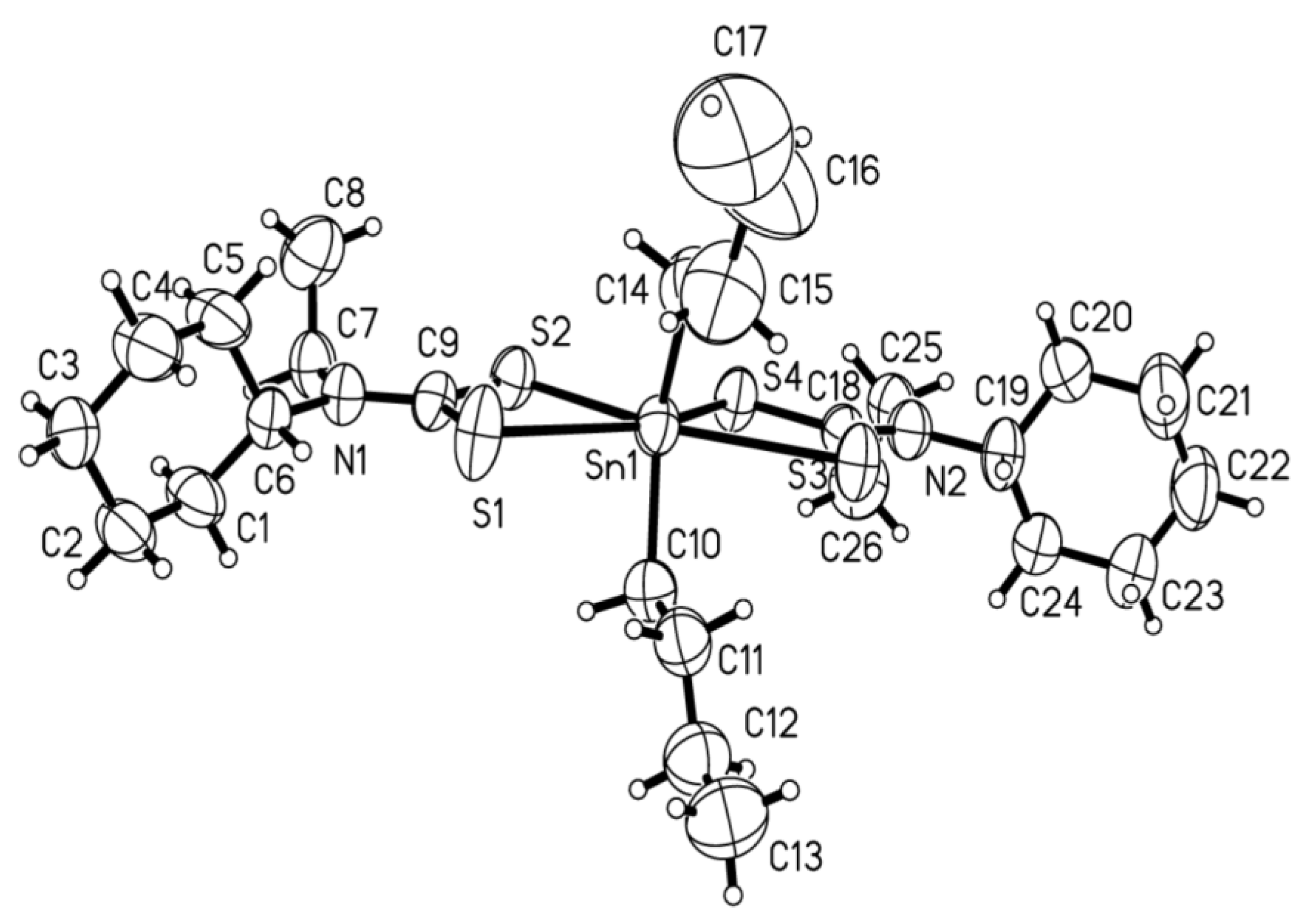

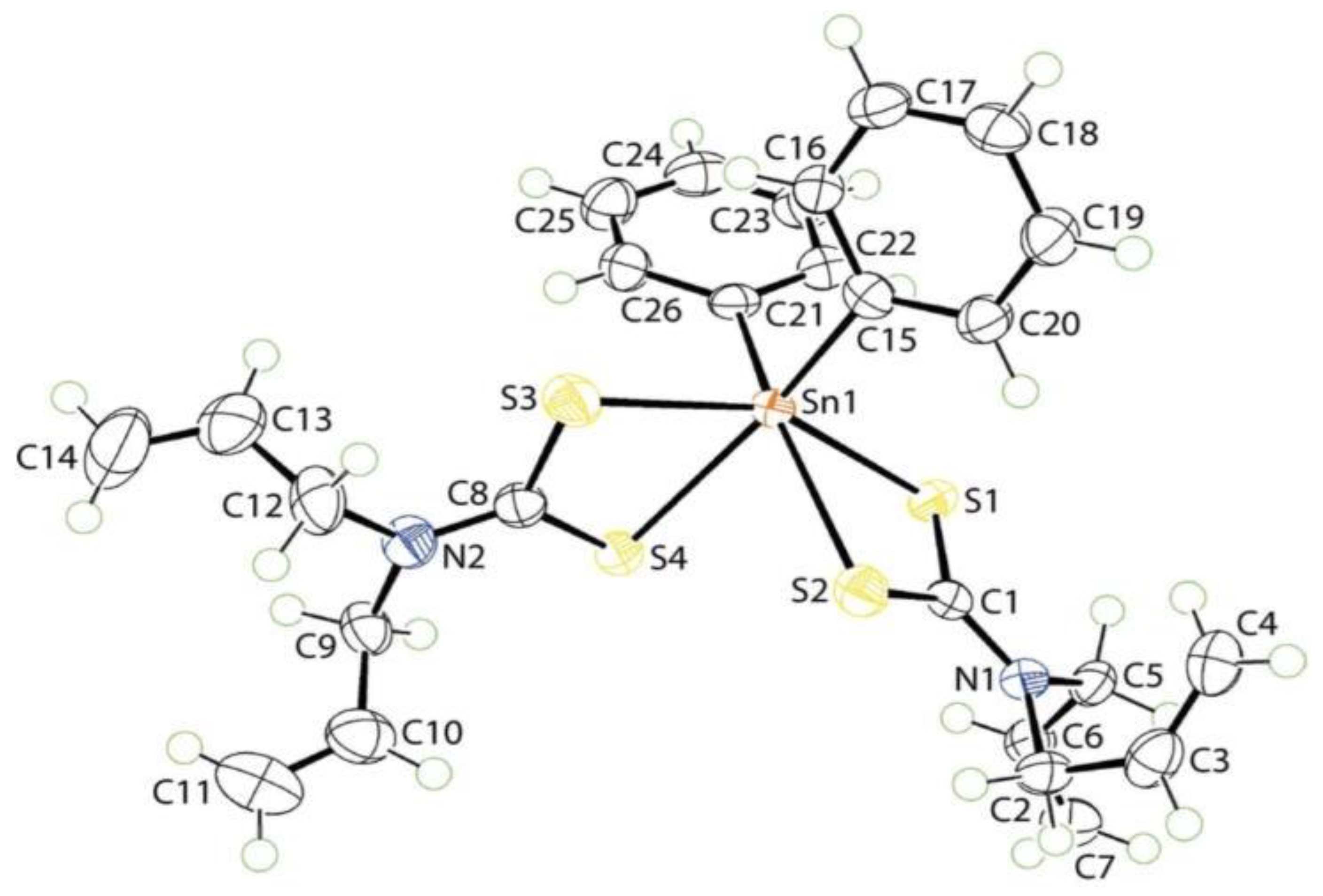

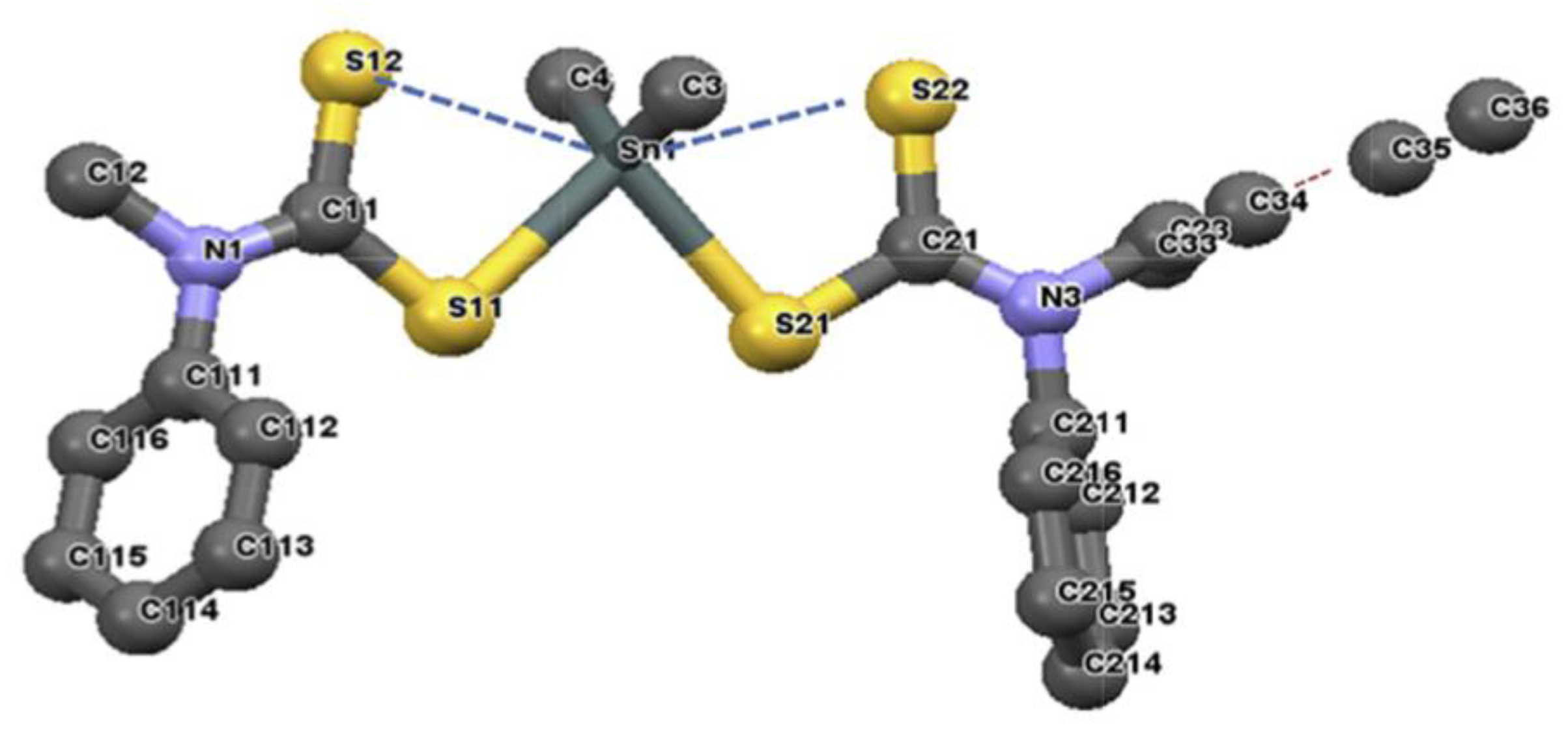

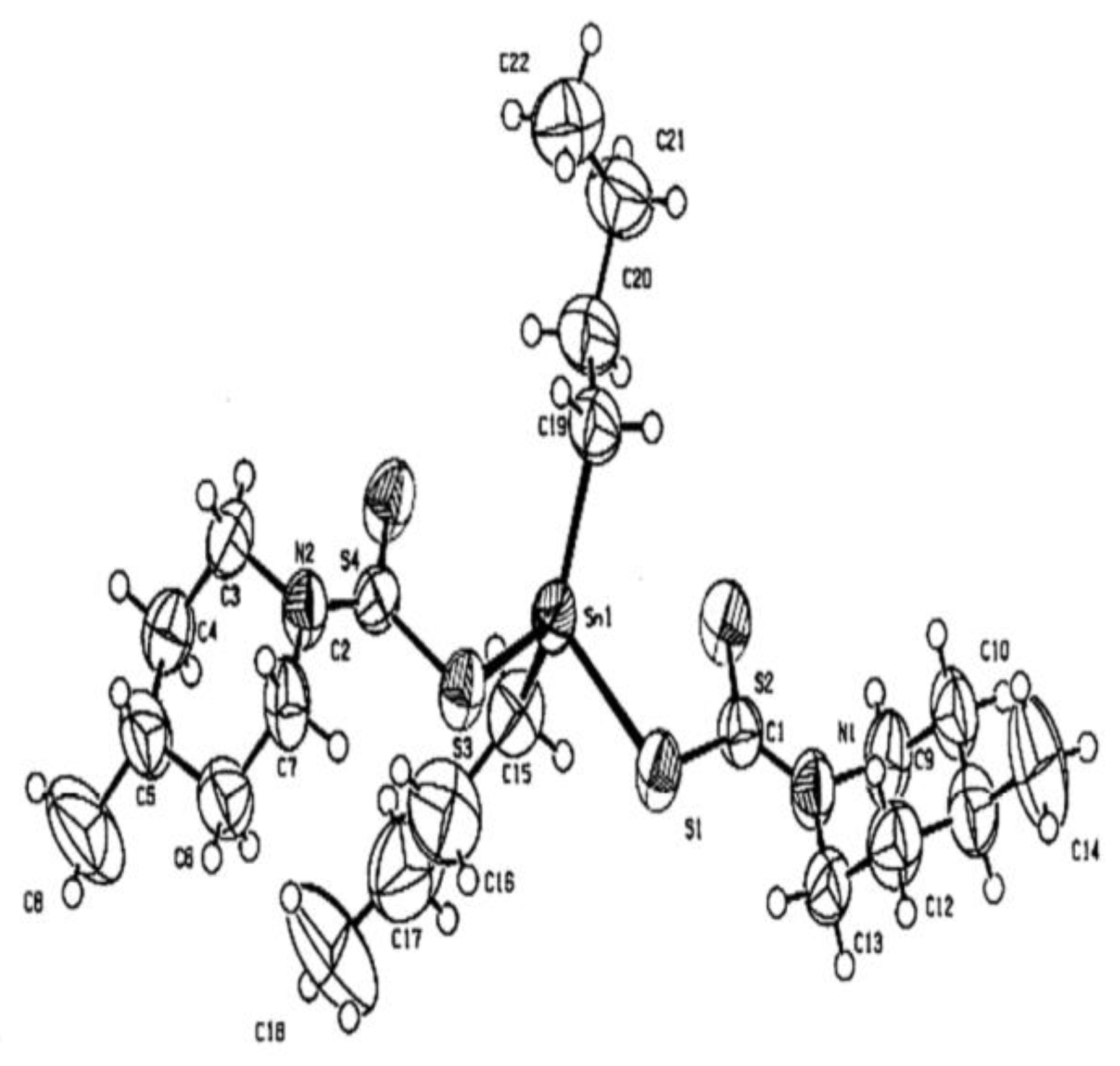

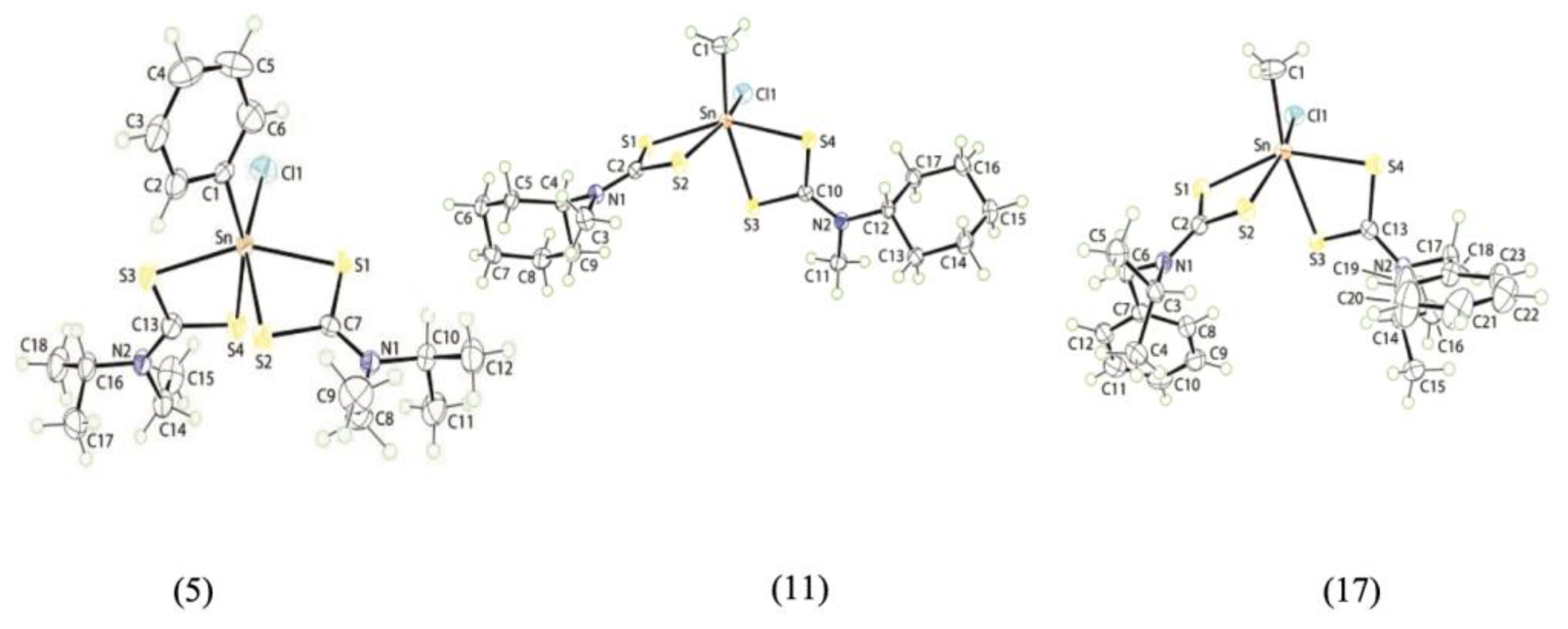

4.4. Recrystallization and Crystallography Study

5. Anticancer Effect Of Organotin(IV) Dithiocarbamate

| Compounds | IC50 values (μM) | Tumor Cell Lines | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dibutyltin(IV) N-butyl-N-phenyldithiocarbamate | 0.8 | Jurkat E6.1 | [45] |

| Diphenyltin(IV) N-butyl-N-phenyldithiocarbamate | 1.3 | ||

| Triphenyltin(IV) N-butyl-N-phenyldithiocarbamate | 0.4 | ||

| Doxorubicin hydrochloride (control) | 0.1 | ||

| Dibutyltin(IV) N-butyl-N-phenyldithiocarbamate | 5.3 | K-562 | |

| Diphenyltin(IV) N-butyl-N-phenyldithiocarbamate | 9.2 | ||

| Triphenyltin(IV) N-butyl-N-phenyldithiocarbamate | 1.9 | ||

| Doxorubicin hydrochloride (control) | 11.0 | ||

| Triphenyltin(IV) benzylisopropyldithiocarbamate | 0.18 | Jurkat E6.1 | [26] |

| Triphenyltin(IV) methylisopropyldithiocarbamate | 0.03 | ||

| Triphenyltin(IV) ethylisopropyldithiocarbamate | 0.42 | ||

| Etoposide (control) | 0.12 | ||

| MeSnClL2 | >4000 | HeLa | [39] |

| BuSnClL2 | 8.12 | ||

| PhSnClL2 | 4.37 | ||

| Me2SnL2 | 12.30 | ||

| Bu2SnL2 | 11.75 | ||

| Ph2SnL2 | 0.01 | ||

| 5-Fluorouracil (control) | 40 | ||

| Dimethyltin(IV)benzyldithiocarbamate | 40 | Hela | [44] |

| Dibutyltin(IV)benzyldithiocarbamate | 0.019 | ||

| Diphenyltin(IV)benzyldithiocarbamate | 330 | ||

| 5-Fluorouracil (control) | 40 | ||

| Dimethyltin(IV)benzyldithiocarbamate | 185 | MCF-7 | |

| Dibutyltin(IV)benzyldithiocarbamate | 57.3 | ||

| Diphenyltin(IV)benzyldithiocarbamate | 20 | ||

| 5-Fluorouracil (control) | 56.2 | ||

| Diphenyltin(IV) diallyldithiocarbamate | 2.36 | HT-29 | [35] |

| Triphenyltin(IV) diallyldithiocarbamate | 0.39 |

| Categories | IC50 value (μg cm-3) |

|---|---|

| Very toxic | 5.0 |

| Moderately toxic | 10.0 |

| Less toxic | 10.0 – 25.0 |

| Non-toxic | .0 |

Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rabiee, N.; Safarkhani, M.; Amini, M.M. Investigating the Structural Chemistry of Organotin(IV) Compounds: Recent Advances. Reviews in Inorganic Chemistry 2019, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; El-Hiti, G.A.; Hadi, A.G.; Ahmed, D.S.; Baashen, M.A.; Hashim, H.; Yousif, E. Photostabilization of Poly(Vinyl Chloride) Films Blended with Organotin Complexes of Mefenamic Acid for Outdoor Applications. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, G.G. Tin, Tin Alloys, and Tin Compounds. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; 2000.

- M. Graisa, A.; A. Husain, A.; H. Al-Mashhadani, M.; S. Ahmed, D.; Adil, H.; Yousif, E. The Organotin Applications in Biological, Industrial and Agricultural Sectors: A Systematic Review. Jurnal Serambi Engineering 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, J.O.; Onwudiwe, D.C. Organotin(IV) Dithiocarbamate Complexes: Chemistry and Biological Activity. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, G.; Metzler-Nolte, N. The Potential of Organometallic Complexes in Medicinal Chemistry. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2012, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A. INDUSTRIAL APPLICATIONS OF ORGANOTIN COMPOUNDS. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1965, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed Annuar, S.N.; Kamaludin, N.F.; Awang, N.; Chan, K.M. Cellular Basis of Organotin(IV) Derivatives as Anticancer Metallodrugs: A Review. Front Chem 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousif, E. A Review of Organotin Compounds: Chemistry and Applications. Archives of Organic and Inorganic Chemical Sciences 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.; Jumat, H.; Ishak, S.A.; Kamaludin, N.F. Evaluation of the Ex Vivo Antimalarial Activity of Organotin (IV) Ethylphenyldithiocarbamate on Erythrocytes Infected With Plasmodium Berghei Nk 65. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences 2014, 17, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.; Mokhtar, N.; Zin, N.M.; Kamaludin, N.F. Antibacterial Activity of Organotin(IV) Methyl and Ethyl Cylohexyldithiocarbamate Compounds. Available online www.jocpr.com Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research 2015, 7, 379–383. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, F.; Sirajuddin, M.; Ali, S.; Khalid, N.; Tahir, M.N.; Shah, N.A.; Rasheed, Z.; Khan, M.R. Organotin(IV) Derivatives of o-Isobutyl Carbonodithioate: Synthesis, Spectroscopic Characterization, X-Ray Structure, HOMO/LUMO and in Vitro Biological Activities. Polyhedron 2016, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq-ur-Rehman; Ali, S.; Badshah, A.; Mazhar, M.; Song, X.; Eng, G.; Khan, K.M. Synthesis, Spectroscopic Characterization: (IR, Multinuclear NMR, 119mSn Mössbauer and Mass Spectrometry), and Biological Activity (Antibacterial, Antifungal, and Cytotoxicity) of Di- and Triorganotin(IV) Complexes of (E)-3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2-Phenylpropenoic Acid. Synthesis and Reactivity in Inorganic and Metal-Organic Chemistry 2004, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Channar, P.A.; Larik, F.A.; Jabeen, F.; Muqadar, U.; Saeed, S.; Flörke, U.; Ismail, H.; Dilshad, E.; Mirza, B. Design, Synthesis, Molecular Docking Studies of Organotin-Drug Derivatives as Multi-Target Agents against Antibacterial, Antifungal, α-Amylase, α-Glucosidase and Butyrylcholinesterase. Inorganica Chim Acta 2017, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Q. Medicinal Properties of Organotin Compounds and Their Limitations Caused by Toxicity. Inorganica Chim Acta 2014, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirajuddin, M.; Ali, S.; McKee, V.; Sohail, M.; Pasha, H. Potentially Bioactive Organotin(IV) Compounds: Synthesis, Characterization, in Vitro Bioactivities and Interaction with SS-DNA. Eur J Med Chem 2014, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A.G.; Jawad, K.; Ahmed, D.S.; Yousif, E. Synthesis and Biological Activities of Organotin (IV) Carboxylates: A Review. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zapata, A.; Eng, G. Organotins and Quantitative-Structure Activity/Property Relationships. J Organomet Chem 2006, 691. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjikakou, S.K.; Abdellah, M.A.; Hadjiliadis, N.; Kubicki, M.; Bakas, T.; Kourkoumelis, N.; Simos, Y. v.; Karkabounas, S.; Barsan, M.M.; Butler, I.S. Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Studies of Organotin(IV) Derivatives with o- or p-Hydroxybenzoic Acids. Bioinorg Chem Appl 2009, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunday, A.O.; Alafara, B.A.; Oladele, O.G. Toxicity and Speciation Analysis of Organotin Compounds. Chemical Speciation and Bioavailability 2012, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kerk, G.J.M.; Luijten, J.G.A. Investigations on Organo-Tin Compounds. IV. The Preparation of a Number of Trialkyl- and Triaryltin Compounds. Journal of Applied Chemistry 1956, 6, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, B.D.; Gioskos, S.; Chandra, S.; Magee, R.J.; Cashion, J.D. Some Triphenyltin(IV) Complexes Containing Potentially Bidentate, Biologically Active Anionic Groups. J Organomet Chem 1992, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellerito, C.; Nagy, L.; Pellerito, L.; Szorcsik, A. Biological Activity Studies on Organotin(IV)N+ Complexes and Parent Compounds. J Organomet Chem 2006, 691. [Google Scholar]

- Mushak, P.; Krigman, M.R.; Mailman, R.B. Comparative Organotin Toxicity in the Developing Rat: Somatic and Morphological Changes and Relationship to Accumulation of Total Tin. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol 1982, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Doctor, S. v.; Fox, D.A. Effects of Organotin Compounds on Maximal Electroshock Seizure (Mes) Responsiveness in Mice. i.Tri(n-Alkyl)Tin Compounds. J Toxicol Environ Health 1982, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.; Yousof, N.S.A.M.; Rajab, N.F.; Kamaludin, N.F. In Vitro Cytotoxic Activity of New Triphenyltin (IV) Alkyl-Isopropyldi-Thiocarbamate Compounds on Human Acute T-Lymphoblastic Cell Line. J Appl Pharm Sci 2015, 5, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, M. Organotin Compounds and Their Therapeutic Potential: A Report from the Organometallic Chemistry Department of the Free University of Brussels. In Proceedings of the Applied Organometallic Chemistry; 2002; Vol. 16.

- Hamid, A.; Azmi, M.A.; Rajab, N.F.; Awang, N.; Jufri, N.F. Cytotoxic Effects of Organotin(IV) Dithiocarbamate Compounds with Different Functional Groups on Leukemic Cell Line, K-562. Sains Malays 2020, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Ramirez, A.; Costanzo, M.; Carrasco, Y.P.; Pannell, K.H.; Aguilera, R.J. Cytotoxic Effects of Two Organotin Compounds and Their Mode of Inflicting Cell Death on Four Mammalian Cancer Cells. Cell Biol Toxicol 2011, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.; Kamaludin, N.F.; Hamid, A.; Mokhtar, N.W.N.; Rajab, Z.F. Cytotoxicity of Triphenyltin(IV) Methyl- and Ethylisopropyldithiocarbamate Compounds in Chronic Myelogenus Leukemia Cell Line (K-562). Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences 2012, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, M.; Castilla, J.; Alonso, C.; Pérez, J. Cisplatin Biochemical Mechanism of Action: From Cytotoxicity to Induction of Cell Death Through Interconnections Between Apoptotic and Necrotic Pathways. Curr Med Chem 2012, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanzio, A.; D’Agostino, S.; Busà, R.; Frazzitta, A.; Rubino, S.; Girasolo, M.A.; Sabatino, P.; Tesoriere, L. Cytotoxic Activity of Organotin(IV) Derivatives with Triazolopyrimidine Containing Exocyclic Oxygen Atoms. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szorcsik, A.; Nagy, L.; Gajda-Schrantz, K.; Pellerito, L.; Nagy, E.; Edelmann, F.T. Structural Studies on Organotin(IV) Complexes Formed with Ligands Containing {S,N,O} Donor Atoms. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2002, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraher, C.E.; Roner, M.R. Organotin Polyethers as Biomaterials. Materials 2009, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haezam, F.N.; Awang, N.; Kamaludin, N.F.; Mohamad, R. Synthesis and Cytotoxic Activity of Organotin(IV) Diallyldithiocarbamate Compounds as Anticancer Agent towards Colon Adenocarcinoma Cells (HT-29). Saudi J Biol Sci 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.; Farina, Y.; Mun, L.K.; Rajab, N.F.; Awang, N. Syntheses, Characterization, X-Ray Diffraction Studies and in Vitro Antitumor Activities of Diorganotin(IV) Derivatives of Bis(p-Substituted-N-Methylbenzylaminedithiocarbamates). Polyhedron 2015, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.; Aziz, Z.A.; Kamaludin, N.F.; Chan, K.M. Cytotoxicity and Mode of Cell Death Induced by Triphenyltin (IV) Compounds in Vitro. Online J Biol Sci 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girasolo, M.A.; Tesoriere, L.; Casella, G.; Attanzio, A.; Capobianco, M.L.; Sabatino, P.; Barone, G.; Rubino, S.; Bonsignore, R. A Novel Compound of Triphenyltin(IV) with N-Tert-Butoxycarbonyl-L-Ornithine Causes Cancer Cell Death by Inducing a P53-Dependent Activation of the Mitochondrial Pathway of Apoptosis. Inorganica Chim Acta 2017, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, J.O.; Onwudiwe, D.C. Antimicrobial and Cytotoxicity Studies of Some Organotin(Iv) n-Ethyl-n-Phenyl Dithiocarbamate Complexes. Pol J Environ Stud 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baul, T.S.B. Antimicrobial Activity of Organotin(IV) Compounds: A Review. Appl Organomet Chem 2008, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.; Zakri, N.H.; Zain, N.M. Antimicrobial Activity of Organotin(IV) Alkylisopropildithiocarbamate Compounds. Available online www.jocpr.com Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research 2016, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Kadu, R.; Roy, H.; Singh, V.K. Diphenyltin(IV) Dithiocarbamate Macrocyclic Scaffolds as Potent Apoptosis Inducers for Human Cancer HEP 3B and IMR 32 Cells: Synthesis, Spectral Characterization, Density Functional Theory Study and in Vitro Cytotoxicity. Appl Organomet Chem 2015, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.; Mohktar, S.M.; Zin, N.M.; Kamaludin, N.F. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activities of Organotin (IV) Alkylphenyl Dithiocarbamate Compounds. Asian Journal of Applied Sciences 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, J.O.; Adeyemi, J.O.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Nundkumar, N.; Singh, M. Diorganotin(Iv) Benzyldithiocarbamate Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, and Thermal and Cytotoxicity Study. Open Chem 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaludin, N.F.; Awang, N.; Baba, I.; Hamid, A.; Meng, C.K. Synthesis, Characterization and Crystal Structure of Organotin(IV) N-Butyl-N-Phenyldithiocarbamate Compounds and Their Cytotoxicity in Human Leukemia Cell Lines. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences 2013, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamba, S.M.; Mishra, A.K.; Mamba, B.B.; Njobeh, P.B.; Dutton, M.F.; Fosso-Kankeu, E. Spectral, Thermal and in Vitro Antimicrobial Studies of Cyclohexylamine-N-Dithiocarbamate Transition Metal Complexes. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2010, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, D.C.; Vieira, F.T.; de Lima, G.M.; Porto, A.O.; Cortés, M.E.; Ardisson, J.D.; Albrecht-Schmitt, T.E. Tin(IV) Complexes of Pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate: Synthesis, Characterisation and Antifungal Activity. Eur J Med Chem 2005, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvek, B.; Dvorak, Z. Targeting of Nuclear Factor-κB and Proteasome by Dithiocarbamate Complexes with Metals. Curr Pharm Des 2007, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajiboye, T.O.; Ajiboye, T.T.; Marzouki, R.; Onwudiwe, D.C. The Versatility in the Applications of Dithiocarbamates. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Yousif, E. Chemistry and Applications of Organotin(IV) Complexes: A Review. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci 2016, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, H.; Ali, S.; Shahzadi, S. Antituberculosis Study of Organotin(IV) Complexes: A Review. Cogent Chem 2015, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AYANDA, O.S.; FATOKI, O.S.; ADEKOLA, F.A.; XIMBA, B.J. Fate and Remediation of Organotin Compounds in Seawaters and Soils. Chem Sci Trans 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.; Kamaludin, N.F.; Ghazali, A.R. Cytotoxic Effect of Organotin(IV) Benzylisopropyldithiocarbamate Compounds on Chang Liver Cell and Hepatocarcinoma HepG2 Cell. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences 2011, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaludin, N.F.; Awang, N. Synthesis and Characterisation of Organotin(IV) Nethyl- N-Phenyldithiocarbamate Compounds and the Crystal Structures of Dibutyl- And Triphenyltin(IV) Nethyl- N-Phenyldithiocarbamate. Res J Chem Environ 2014, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Sainorudin, M.H.; Sidek, N.M.; Ismail, N.; Rozaini, M.Z.H.; Harun, N.A.; Tuan Anuar, T.N.S.; Azmi, A.A.A.R.; Yusoff, F. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activity of Organotin(IV) Complexes Featuring Di-2-Ethylhexyldithiocarbamate and N-Methylbutyldithiocarbamate as Ligands. GSTF Journal of Chemical Sciences (JChem) 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kaushik, N.K. Thermal Studies on Some Organotin(IV) Complexes with Piperidine and 2-Aminopyridine Dithiocarbamates. J Therm Anal Calorim 2004, 78, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.; Baba, I. Diorganotin(IV) Alkylcyclohexyldithiocarbamate Compounds: Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activities. Sains Malays 2012, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Fanjul-Bolado, P.; Fogel, R.; Limson, J.; Purcarea, C.; Vasilescu, A. Advances in the Detection of Dithiocarbamate Fungicides: Opportunities for Biosensors. Biosensors (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awang, N.; Baba, I.; Yamin, B.M.; Halim, A.A. Preparation, Characterization and Antimicrobial Assay of 1,10-Phenanthroline and 2,2’-Bipyridyl Adducts of Cadmium(II) N-Sec-Butyl-N- Propyldithiocarbamate: Crystal Structure of Cd[S2CN(i-C4H9)(C3H7)]2(2,2’-Bipyridyl). World Appl Sci J 2011, 12, 1568–1574. [Google Scholar]

- Nabipour, H.; Ghammamy, S.; Ashuri, S.; Aghbolagh, Z.S. Synthesis of a New Dithiocarbamate Compound and Study of Its Biological Properties. Org. Chem. J 2010, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, O.-S.; Sohn, Y.-S. Coordination Chemistry of Organotin(IV) Dithiocarbamate Complexes. Bull Korean Chem Soc 1988, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.Z.; Zhao, P.S.; Zhang, S.S. Crystal Structure and Characterization of Pd(II) Bis(Diisopropyldithiocarbamate) Complex. Chin J Chem 2001, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domazetis, G.; Magee, R.J.; James, B.D. Synthesis and Structure of Some Triphenyltin(IV) Dithiocarbamate Compounds. J Organomet Chem 1977, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odularu, A.T.; Ajibade, P.A. Dithiocarbamates: Challenges, Control, and Approaches to Excellent Yield, Characterization, and Their Biological Applications. Bioinorg Chem Appl 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwudiwe, D.C.; Ajibade, P.A. Synthesis and Characterization of Metal Complexes of N-Alkyl-N-Phenyl Dithiocarbamates. Polyhedron 2010, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.; Baba, I.; Yamin, B.M.; Othman, M.S.; Kamaludin, N.F. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activities of Organotin (IV) Methylcyclohexyldithiocarbamate Compounds. Am J Appl Sci 2011, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.; Geanangle, R.A. The Preparation of Tin(II) Dithiocarbamates from Ammonium Dithiocarbamate Salts. Inorganica Chim Acta 1975, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, J.O.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Ekennia, A.C.; Okafor, S.N.; Hosten, E.C. Organotin(IV)N-Butyl-N-Phenyldithiocarbamate Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, Biological Evaluation and Molecular Docking Studies. J Mol Struct 2019, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, J.O.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Hosten, E.C. Organotin(IV) Complexes Derived from N-Ethyl-N-Phenyldithiocarbamate: Synthesis, Characterization and Thermal Studies. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2018, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, J.O.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Hosten, E.C. Synthesis, Characterization and the Use of Organotin(IV) Dithiocarbamate Complexes as Precursor to Tin Sulfide Nanoparticles by Heat up Approach. J Mol Struct 2019, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adli, H.K.; Sidek, N.M.; Ismail, N.; Khairul, W.M. Several Organotin (IV) Complexes Featuring 1-Methylpiperazinedithiocarbamate and N-Methylcyclohexyldithiocarbamate as Ligands and Their Anti-Microbial Activity Studies. Chiang Mai Journal of Science 2013, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Awang, N.; Baba, I.; Yamin, B.; Othman, M.; Halim, A.; Muda, J.; Aziz, A.; Lumpur, K. ; Malaysia Synthesis, Characterization and Crystal Structure of Triphenyltin(IV) N-Alkyl-N-Cyclohexyldithiocarbamate Compounds. World Appl Sci J 2011, 12, 630–635. [Google Scholar]

- Awang, N.; Kamaludin, N.F.; Baba, I.; Chan, K.M.; Rajaajab, N.F.; Hamid, A. Synthesis, Characterization and Antitumor Activity of New Organotin(IV) Methoxyethyldithiocarbamate Complexes. Oriental Journal of Chemistry 2016, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, R.; Awang, N.; Farahana Kamaludin, N. Synthesis and Characterisation of New Organotin (IV)(2-Methoxyethyl)-Methyldithiocarbamate Complexes. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci 2016, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Muthalib, A.F.A.; Baba, I. New Mono-Organotin (IV) Dithiocarbamate Complexes. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings; 2014; Vol. 1614.

- Baba, I.; Raya, I. Kompleks Praseodimium Ditiokarbamat 1,10 Fenantrolin. Sains Malays 2010, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Fadeeva, V.P.; Tikhova, V.D.; Nikulicheva, O.N. Elemental Analysis of Organic Compounds with the Use of Automated CHNS Analyzers. Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2008, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edington, S.C.; Liu, S.; Baiz, C.R. Infrared Spectroscopy Probes Ion Binding Geometries. In Methods in Enzymology; 2021; Vol. 651.

- Kumar, A.; Khandelwal, M.; Gupta, S.K.; Kumar, V.; Rani, R. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy: Data Interpretation and Applications in Structure Elucidation and Analysis of Small Molecules and Nanostructures. In Data Processing Handbook for Complex Biological Data Sources; 2019.

- Sonia, T.A.; Sharma, C.P. Experimental Techniques Involved in the Development of Oral Insulin Carriers. In Oral Delivery of Insulin; 2014.

- Zia-ur-Rehman; Shahzadi, S. ; Ali, S.; Badshah, A.; Jin, G.X. Crystal Structure of 1,1-Dibutyl-1,1-Bis[(4-Methyl-1-Piperidinyl) Dithiocarbamato] Tin(IV). Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society 2006, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, Y.F.; Teoh, S.G.; Tengku-Muhammad, T.S.; Ha, S.T.; Sivasothy, Y. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Organotin (IV) Complexes Derived of 4- (Diethylamino) Benzoic Acid: Cytotoxic Assay on Human Liver Carcinoma Cells (HepG2). Aust J Basic Appl Sci 2010, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chaber, R.; Łach, K.; Szmuc, K.; Michalak, E.; Raciborska, A.; Mazur, D.; Machaczka, M.; Cebulski, J. Application of Infrared Spectroscopy in the Identification of Ewing Sarcoma: A Preliminary Report. Infrared Phys Technol 2017, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, G.; McLeod, A.S.; Gainsforth, Z.; Kelly, P.; Bechtel, H.A.; Keilmann, F.; Westphal, A.; Thiemens, M.; Basov, D.N. Nanoscale Infrared Spectroscopy as a Non-Destructive Probe of Extraterrestrial Samples. Nat Commun 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartina, D.; Wahab, A.W.; Ahmad, A.; Irfandi, R.; Raya, I. In Vitro Antibacterial and Anticancer Activity of Zn(II)Valinedithiocarbamate Complexes. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series; 2019; Vol. 1341.

- Onwudiwe, D.C.; Hrubaru, M.; Ebenso, E.E. Synthesis, Structural and Optical Properties of TOPO and HDA Capped Cadmium Sulphide Nanocrystals, and the Effect of Capping Ligand Concentration. J Nanomater 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.D.; Xue, S.C. Synthesis and Characterization of Organotin Complexes with Dithiocarbamates and Crystal Structures of (4-NCC6H4CH2) 2Sn(S2CNEt2)2 and (2-ClC 6H4CH2)2 Sn(Cl)S 2CNBz2. Appl Organomet Chem 2006, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odola, A.J.; Woods, J.A.O. New Nickel(II) Mixed Ligand Complexes of Dithiocarbamates with Schiff Base. J Chem Pharm Res 2011, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Alverdi, V.; Giovagnini, L.; Marzano, C.; Seraglia, R.; Bettio, F.; Sitran, S.; Graziani, R.; Fregona, D. Characterization Studies and Cytotoxicity Assays of Pt(II) and Pd(II) Dithiocarbamate Complexes by Means of FT-IR, NMR Spectroscopy and Mass Spectrometry. J Inorg Biochem 2004, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, R.; Takabe, A.; Matsuda, H. Facile Synthesis of Antimony Dithiocarbamate Complexes. Polyhedron 1987, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.A.; Glass, W.K.; Burke, M.A. The General Use of i.r. Spectral Criteria in Discussions of the Bonding and Structure of Metal Dithiocarbamates. Spectrochim Acta A 1976, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonati, F.; Ugo, R. Organotin(IV) N,N-Disubstituted Dithiocarbamates. J Organomet Chem 1967, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.; Komura, M.; Kawasaki, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Okawara, R. INFRA-RED AND PMR SPECTRA OF SOME ORGANO-TIN(IV) N,N-DIMETHYLDITHIOCARBAMATES; 1968; Vol. 30.

- Muthalib, A.F.A.; Baba, I.; Farina, Y.; Samsudin, M.W. SYNTHESIS AND CHARACTERIZATION OF DIPHENYLTIN(IV) DITHIOCARBAMATE COMPOUNDS (Sintesis Dan Pencirian Sebatian Difenilstanum(IV) Ditiokarbamat). The Malaysian Journal of Analytical Sciences 2011, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton, F.A.; McCleverty, J.A. Dimethyl- and Diethyldithiocarbamate Complexes of Some Metal Carbonyl Compounds. Inorg Chem 1964, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, J.O.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Singh, M. Synthesis, Characterization, and Cytotoxicity Study of Organotin(IV) Complexes Involving Different Dithiocarbamate Groups. J Mol Struct 2019, 1179, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Nami, S.A.A.; Siddiqi, K.S. Mononuclear Indolyldithiocarbamates of SnCl4 and R2SnCl2: Spectroscopic, Thermal Characterizations and Cytotoxicity Assays in Vitro. J Organomet Chem 2008, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.; Baba, I.; Mohd Yousof, N.S.A.; Kamaludin, N.F. Synthesis and Characterization of Organotin(IV) N-Benzyl-N-Isopropyldithiocarbamate Compounds: Cytotoxic Assay on Human Hepatocarcinoma Cells (HepG2). Am J Appl Sci 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainorudin, M.H.M.H.S.N.M.S.N.I.M.Z.H.R.N.A.H.T.N.S.T.A.A.A.A.R.A. ,Farhanini Y. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activity of Organotin(IV) Complexes Featuring Di-2-Ethylhexyldithiocarbamate and N-Methylbutyldithiocarbamate as Ligands. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, J.O.; Saibu, G.M.; Olasunkanmi, L.O.; Fadaka, A.O.; Meyer, M.; Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Oyedeji, A.O. Synthesis, Computational and Biological Studies of Alkyltin(IV) N-Methyl-N-Hydroxyethyl Dithiocarbamate Complexes. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwudiwe, D.C.; Ajibade, P.A. Synthesis, Characterization and Thermal Studies of Zn(Ii), Cd(II) and Hg(II) Complexes of N-Methyl-N-Phenyldithiocarbamate: The Single Crystal Structure of [(C 6H 5)(CH 3)NCS 2]4Hg 2. Int J Mol Sci 2011, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riveros, P.C.; Perilla, I.C.; Poveda, A.; Keller, H.J.; Pritzkow, H. Tris(Dialkyldithiocarbamato)Diazenido(1-) and Hydrazido(2-) Molybdenum Complexes: Synthesis and Reactivity in Acid Medium. Polyhedron 2000, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul Prakasam, B.; Ramalingam, K.; Bocelli, G.; Cantoni, A. NMR and Fluorescence Spectral Studies on Bisdithiocarbamates of Divalent Zn, Cd and Their Nitrogenous Adducts: Single Crystal X-Ray Structure of (1,10-Phenanthroline)Bis(4-Methylpiperazinecarbodithioato) Zinc(II). Polyhedron 2007, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.D.; Zhai, J.; Sun, Y.Y.; Wang, D.Q. Synthesis, Characterizations and Crystal Structures of New Antimony (III) Complexes with Dithiocarbamate Ligands. Polyhedron 2008, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakasam, B.A.; Ramalingam, K.; Baskaran, R.; Bocelli, G.; Cantoni, A. Synthesis, NMR Spectral and Single Crystal X-Ray Structural Studies on Ni(II) Dithiocarbamates with NiS2PN, NiS2PC, NiS2P2 Chromophores: Crystal Structures of (4-Methylpiperazinecarbodithioato)(Thiocyanato-N) (Triphenylphosphine)Nickel(II) and Bis(Triphenylphosphine) (4-Methylpiperazinecarbodithioato)Nickel(II) Perchlorate Monohydrate. Polyhedron 2007, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibade, P.A.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Moloto, M.J. Synthesis of Hexadecylamine Capped Nanoparticles Using Group 12 Complexes of N-Alkyl-N-Phenyl Dithiocarbamate as Single-Source Precursors. Polyhedron 2011, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.S.; Hussain, M.; Hanif, M.; Ali, S.; Qayyum, M.; Mirza, B. Di- and Triorganotin(IV) Esters of 3,4-Methylenedioxyphenylpropenoic Acid: Synthesis, Spectroscopic Characterization and Biological Screening for Antimicrobial, Cytotoxic and Antitumor Activities. Chem Biol Drug Des 2008, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VAN GAAL, H.L.M.; DIESVELD, J.W.; PIJPERS, F.W.; VAN DER LINDEN, J.G.M. ChemInform Abstract: CARBON-13 NMR SPECTRA OF DITHIOCARBAMATES. CHEMICAL SHIFTS, CARBON-NITROGEN STRETCHING VIBRATION FREQUENCIES AND Π-BONDING IN THE NCS2 FRAGMENT. Chemischer Informationsdienst 1980, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovilj, S.P.; Vučković, G.; Babić, K.; Sabo, T.J.; Macura, S.; Juranić, N. Mixed-Ligand Complexes of Cobalt(III) with Dithiocarbamates and a Cyclic Tetradentate Secondary Amine. J Coord Chem 1997, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macomber, R.S. Proton-Carbon Chemical Shift Correlations. J Chem Educ 1991, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirajuddin, M.; Ali, S.; McKee, V.; Zaib, S.; Iqbal, J. Organotin(Iv) Carboxylate Derivatives as a New Addition to Anticancer and Antileishmanial Agents: Design, Physicochemical Characterization and Interaction with Salmon Sperm DNA. RSC Adv 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otera, J. 119Sn Chemical Shifts in Five- and Six-Coordinate Organotin Chelates. J Organomet Chem 1981, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, O.S.; Hwa Jeong, J.; Soo Sohn, Y. Preparation, Properties and Structures of Estertin(IV) Sulphides. Polyhedron 1989, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Ali, S.; Parvez, M.; Munir, A.; Mazhar, M.; Khan, K.M.; Ali Shah, T. Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Studies of Tri- and Diorganotin(Iv) Complexes with 2′, 4′-Difluoro-4-Hydroxy-[1, 1′]-Biphenyle-3-Carbolic Acid: Crystal Structure of [(CH3)3Sn(C13H7O3F2)]. Heteroatom Chemistry 2002, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghat, T.; Shokohi-Pour, Z. Synthesis and Spectroscopic Studies of New Organotin(IV) Complexes with Tridentate N- and O-Donor Schiff Bases. J Coord Chem 2009, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirajuddin, M.; Ali, S.; Tahir, M.N. Pharmacological Investigation of Mono-, Di- and Tri-Organotin(IV) Derivatives of Carbodithioates: Design, Spectroscopic Characterization, Interaction with SS-DNA and POM Analyses. Inorganica Chim Acta 2016, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi, S.; Ali, S. Iranian Chemical Society Structural Chemistry of Organotin(IV) Complexes. Journal of the 2008, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Tiekink, E.R.T. Structural Chemistry of Organotin Carboxylates: A Review of the Crystallographic Literature. Appl Organomet Chem 1991, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chans, G.M.; Nieto-Camacho, A.; Ramirez-Apan, T.; Hernandez-Ortega, S.; Alvarez-Toledano, C.; Gomez, E. Synthetic, Spectroscopic, Crystallographic, and Biological Studies of Seven-Coordinated Diorganotin(IV) Complexes Derived from Schiff Bases and Pyridinic Carboxylic Acids. Aust J Chem 2016, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, J.R. X-Ray Crystallography of Chemical Compounds. Life Sci 2010, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, M.E.Y.; Burgess, J.P.; George, C.; Bailey, G.S.; Gilliam, A.F.; Seltzman, H.H.; Thomas, B.F. Structure Elucidation of a Novel Ring-Constrained Biaryl Pyrazole CB 1 Cannabinoid Receptor Antagonist. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry 2003, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Ibers, J.A.; Jung, O.S.; Sohn, Y.S. Structure of Di(Tert-Butyl)Bis(N,N-Dimethyldithiocarbamato)Tin(IV). Acta Crystallogr C 1987, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.M.; Ali, S.; Hussain, S.T.; Shahzadi, S. Review: Structural Diversity in Organotin(IV) Dithiocarboxylates and Carboxylates. J Coord Chem 2013, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Farina, Y.; Mun, L.K.; Rajab, N.F.; Awang, N. Syntheses, Spectral Characterization, X-Ray Studies and in Vitro Cytotoxic Activities of Triorganotin(IV) Derivatives of p-Substituted N-Methylbenzylaminedithiocarbamates. J Mol Struct 2014, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, K.; Kutschabsky, L.; Kulpe, S. The Molecular and Crystal Structure of Bis-Dimethyl Pentamethine Cyanine Perchlorate, C9H17N2Cl04. Kristall und Technik 1974, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Martínez, J.P.; Toledo-Martínez, I.; Román-Bravo, P.; García, P.G. y.; Godoy-Alcántar, C.; López-Cardoso, M.; Morales-Rojas, H. Diorganotin(IV) Dithiocarbamate Complexes as Chromogenic Sensors of Anion Binding. Polyhedron 2009, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi, S.; Ali, S.; Fettouhi, M. Synthesis, Spectroscopy, in Vitro Biological Activity and X-Ray Structure of (4-Methylpiperidine-Dithiocarbamato-S,S′)Triphenyltin(IV). J Chem Crystallogr 2008, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Z.U.; Shahzadi, S.; Ali, S.; Jin, G.X. Preparation, Spectroscopy, Antimicrobial Assay, and X-Ray Structure of Dimethyl Bis-(4-Methylpiperidine Dithiocarbamato-S,S′)-Tin(IV). Turk J Chem 2007, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, R.; Trivedi, M.; Chauhan, R.; Prasad, R.; Kociok-Köhn, G.; Kumar, A. Supramolecular Architecture of Organotin(IV) 4-Hydroxypiperidine Dithiocarbamates: Crystallographic, Computational and Hirshfeld Surface Analyses. Inorganica Chim Acta 2016, 450, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondi, A. Van Der Waals Volumes and Radii. Journal of Physical Chemistry 1964, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiekink, E.R.T. Tin Dithiocarbamates: Applications and Structures. Appl Organomet Chem 2008, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, E.J.; Bolitho, E.M.; Bridgewater, H.E.; Carter, O.W.L.; Donnelly, J.M.; Imberti, C.; Lant, E.C.; Lermyte, F.; Needham, R.J.; Palau, M.; et al. Metallodrugs Are Unique: Opportunities and Challenges of Discovery and Development. Chem Sci 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, R.; Moussa, Y.E.; Wheate, N.J. The Side Effects of Platinum-Based Chemotherapy Drugs: A Review for Chemists. Dalton Transactions 2018, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Dasari, S.; Bernard Tchounwou, P. Cisplatin in Cancer Therapy: Molecular Mechanisms of Action. Eur J Pharmacol 2014, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ruiz, S.; Kaluderović, G.N.; Prashar, S.; Hey-Hawkins, E.; Erić, A.; Žižak, Ž.; Juranić, Z.D. Study of the Cytotoxic Activity of Di and Triphenyltin(IV) Carboxylate Complexes. J Inorg Biochem 2008, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N.; Ahmad, M.; Sirajuddin, M.; Ali, Z.; Tumanov, N.; Wouters, J.; Chafik, A.; Solak, K.; Mavi, A.; Muhammad, S.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization, Biological Activity and Molecular Docking Studies of Novel Organotin(IV) Carboxylates. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, B.; Basu Baul, T.S.; Chatterjee, A. P53-Dependent Antiproliferative and Antitumor Effect of Novel Alkyl Series of Diorganotin(IV) Compounds. Invest New Drugs 2009, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.; das Sarma, K.; Antony, A. Differential Effects of Tri-n-Butylstannyl Benzoates on Induction of Apoptosis in K562 and MCF-7 Cells. IUBMB Life 2000, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, O.; Manabe, S.; Iwai, H.; Arakawa, Y. Recent Progress in the Study of Analytical Methods, Toxicity, Metabolism and Health Effects of Organotin Compounds. Japanese Journal of Industrial Health 1982, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, M. Toxicity and the Cardiovascular Activity of Organotin Compounds: A Review. Appl Organomet Chem 2008, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How, F.N.F.; Crouse, K.A.; Tahir, M.I.M.; Tarafder, M.T.H.; Cowley, A.R. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Studies of S-Benzyl-β-N-(Benzoyl) Dithiocarbazate and Its Metal Complexes. Polyhedron 2008, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanski, M.; Jakupec, M.; Keppler, B. Update of the Preclinical Situation of Anticancer Platinum Complexes: Novel Design Strategies and Innovative Analytical Approaches. Curr Med Chem 2005, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, H.; Ali, S.; Shahzadi, S. Anti-Inflammatory and Acute Toxicity Study of Organotin ( IV ) Complexes : A Review.; 2016.

- Iqbal, M.; Ali, S.; Haider, A.; Khalid, N. Therapeutic Properties of Organotin Complexes with Reference to Their Structural and Environmental Features. Reviews in Inorganic Chemistry 2017, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Ashfaq, M.; Waseem, A.; Ahmed, M.; Najam, T.; Shaheen, S.; Rivera, G. Synthesis and Biological Activities of Organotin(IV) Complexes as Antitumoral and Antimicrobial Agents. A Review. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adokoh, C.K. Therapeutic Potential of Dithiocarbamate Supported Gold Compounds. RSC Adv 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaruzza, L.; Fregona, D.; Mongiat, M.; Ronconi, L.; Fassina, A.; Colombatti, A.; Aldinucci, D. Antitumor Activity of Gold(III)-Dithiocarbamato Derivatives on Prostate Cancer Cells and Xenografts. Int J Cancer 2011, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaludin, N.F.; Ismail, N.; Awang, N.; Mohamad, R.; Pim, N.U. Cytotoxicity Evaluation and the Mode of Cell Death of K562 Cells Induced by Organotin (IV) (2-Methoxyethyl) Methyldithiocarbamate Compounds. J Appl Pharm Sci 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakšić, Ž. Mechanisms of Organotin-Induced Apoptosis. In Biochemical and Biological Effects of Organotins; 2012.

- Basu, A.; Krishnamurthy, S. Cellular Responses to Cisplatin-Induced DNA Damage. J Nucleic Acids 2010, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, E.N.M.; Latif, M.A.M.; Tahir, M.I.M.; Sakoff, J.A.; Simone, M.I.; Page, A.J.; Veerakumarasivam, A.; Tiekink, E.R.T.; Ravoof, T.B.S.A. O-Vanillin Derived Schiff Bases and Their Organotin(Iv) Compounds: Synthesis, Structural Characterisation, in-Silico Studies and Cytotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjmand, F.; Parveen, S.; Tabassum, S.; Pettinari, C. Organo-Tin Antitumor Compounds: Their Present Status in Drug Development and Future Perspectives. Inorganica Chim Acta 2014, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Yan, H.; Chang, G.; Li, Z.; Niu, M.; Hong, M. Organotin(IV) Complexes Derived from Hydrazone Schiff Base: Synthesis, Crystal Structure, in Vitro Cytotoxicity and DNA/BSA Interactions. Inorganica Chim Acta 2017, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, F.; Sirajuddin, M.; Ali, S.; Zia-ur-Rehman; Dyson, P. J.; Shah, N.A.; Tahir, M.N. Organotin(IV) 4-(Benzo[d][1,3]Dioxol-5-Ylmethyl)Piperazine-1-Carbodithioates: Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activities. J Organomet Chem 2018, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alama, A.; Tasso, B.; Novelli, F.; Sparatore, F. Organometallic Compounds in Oncology: Implications of Novel Organotins as Antitumor Agents. Drug Discov Today 2009, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M. Gold Complexes as Potential Anti-Parasitic Agents. Coord Chem Rev 2009, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Complexes | Yield (%) | Melting point (°C) | Elemental analysis % Found (Calculated) |

References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | N | S | ||||

| Dimethyltin(IV) methylcyclohexyldithiocarbamate |

89 | 147.9- 148.8 | 40.66 (41.14) | 6.46 (6.48) | 5.30 (5.33) | 26.43 (24.38) | [66] |

| Dibutyltin(IV) methylcyclohexyldithiocarbamate | 83 | 122.6- 124.0 | 47.15 (47.29) | 8.08 (7.55) | 4.62 (4.60) | 22.72 (21.02) | |

| Triphenyltin(IV) methylcyclohexyldithiocarbamate | 76 | 136.8- 138.2 | 57.71 (57.99 ) | 4.98 (5.39) | 2.57 (2.60) | 11.26 (11.90) | |

| Diphenyltin(IV) N-butyl-N-phenyldithiocarbamate | 82.1 | 102.1-104.0 | 56.15 (56.59) |

5.89 (5.31) |

3.77 (3.88) |

16.81 (17.77) |

[45] |

| Triphenyltin(IV) N-butyl-N-phenyldithiocarbamate | 34.0 | 101.0 -102.0 | 60.54- (60.64) |

5.08 (5.09) |

2.34 (2.44) |

11.31 (11.17) |

|

| Dibutyltin(IV) N-ethyl-N-phenyldithiocarbamate | 84.5 | 126.9 -128.2 | 50.72 (49.92) |

7.47 (6.12) |

4.22 (4.48) | 20.26 (20.50) |

[54] |

| Di-tert-butyltin(IV) N-ethyl-N-phenyldithiocarbamate | 51.6 | 124.8 -126.5 | 48.19 (49.92) | 7.34 (6.12) | 4.13 (4.48) | 20.10 (20.50) | |

| Diphenyltin(IV) N-ethyl-N-phenyldithiocarbamate | 74.8 | 70.2-72.9 | 54.13 (54.14) | 4.49 (4.54) | 4.27 (4.21) | 18.28 (19.27) | |

| Triphenyltin(IV) N-methylbutyldithiocarbamate | 78 | 88.3- 90.8 |

55.70 (56.27) |

4.91 (5.31) |

2.34 (2.73) | 11.91 (12.52) |

[55] |

| Dibutyltin(IV) methoxyethyldithiocarbamate | 76 | 68-69 | 41.76 (40.77) | 6.07 (7.14) | 4.91 (4.31) | 19.25 (19.75) | [73] |

| Triphenyltin(IV) methoxyethyldithiocarbamate | 89 | 93-94 | 54.38 (53.76) | 4.38 (5.24) | 2.87 (2.51) | 12.13 (11.49) | |

| Dibutyltin(IV) (2-methoxyethyl)methyl dithiocarbamates | 66.31 | 59.7–62.9 | 40.26 (38.50) | 7.33 (6.82) | 4.98 (5.04) | 23.65 (22.84) | [74] |

| Diphenyltin(IV) (2-methoxyethyl)methyl dithiocarbamates | 78 | 109.1–111.1 | 44.70 (43.93) | 5.12 (5.03) | 4.26 (4.67) | 20.24 (21.33) | |

| Tricyclohexyltin(IV) (2-methoxyethyl)methyl dithiocarbamates |

76.39 | 102.7–104.4 | 52.40 (51.89) | 8.05 (8.14) | 2.53 (2.63) | 12.47 (12.05) | |

|

Dimethyltin(IV) N-ethyl-N-phenyl dithiocarbamates |

82 | 167–169 | 43.90 (44.37) |

5.01 (4.84) | 4.99 (5.17) | 23.99 (23.69) | [69] |

|

Dibuthyltin(IV) N-ethyl-N-phenyl dithiocarbamates |

87 | 121–122 | 48.42 (49.92) | 5.81 (6.12) | 5.48 (4.48) | 21.50 (20.50) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).