Submitted:

22 May 2023

Posted:

24 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Neuroinflammation and Microglia

2.1. Immunoregulatory and neuro-regulatory substances released from microglia: Cytokines and Chemokines.

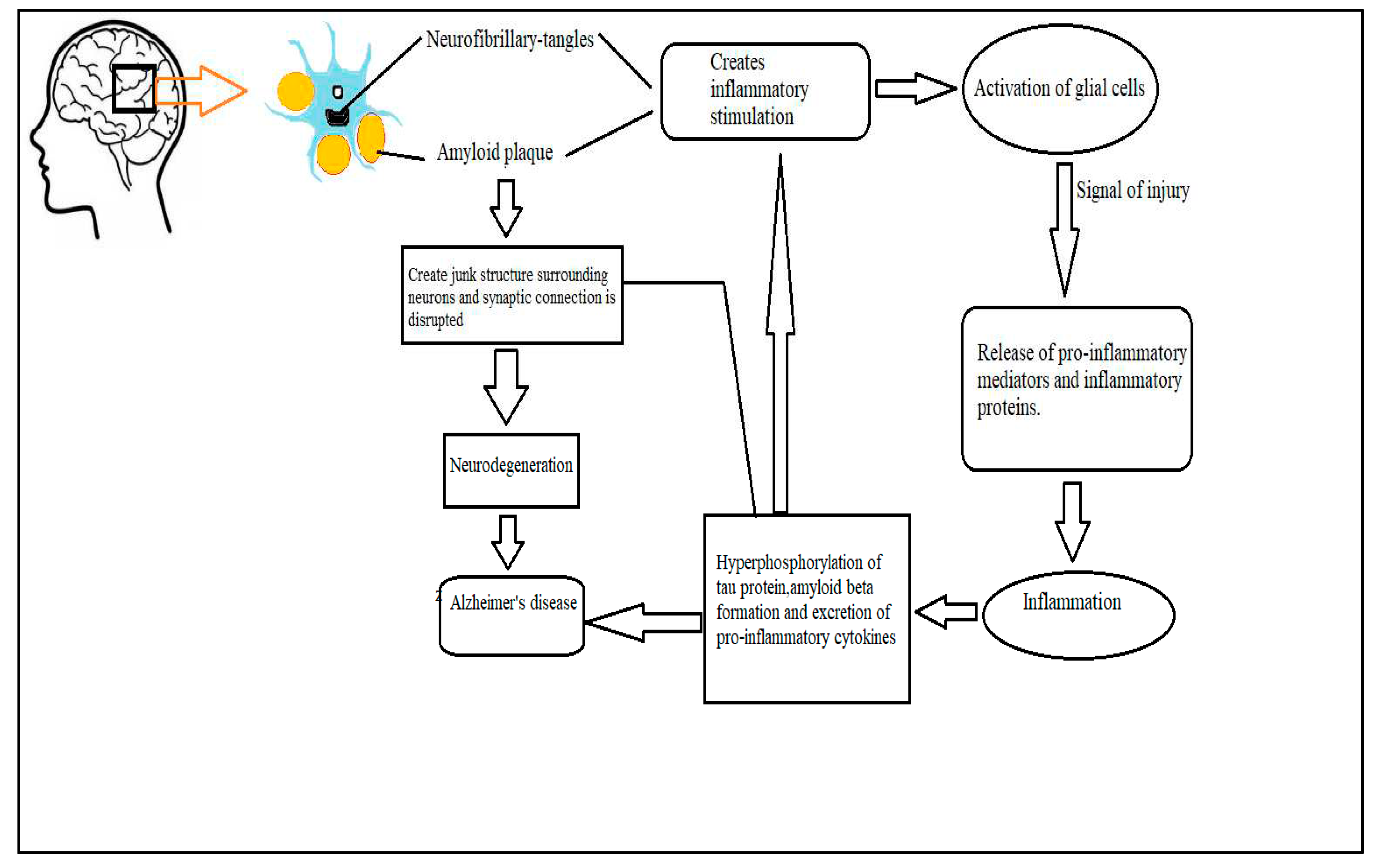

3. Mechanism of microglia induced neuroinflammation triggering the progression of AD.

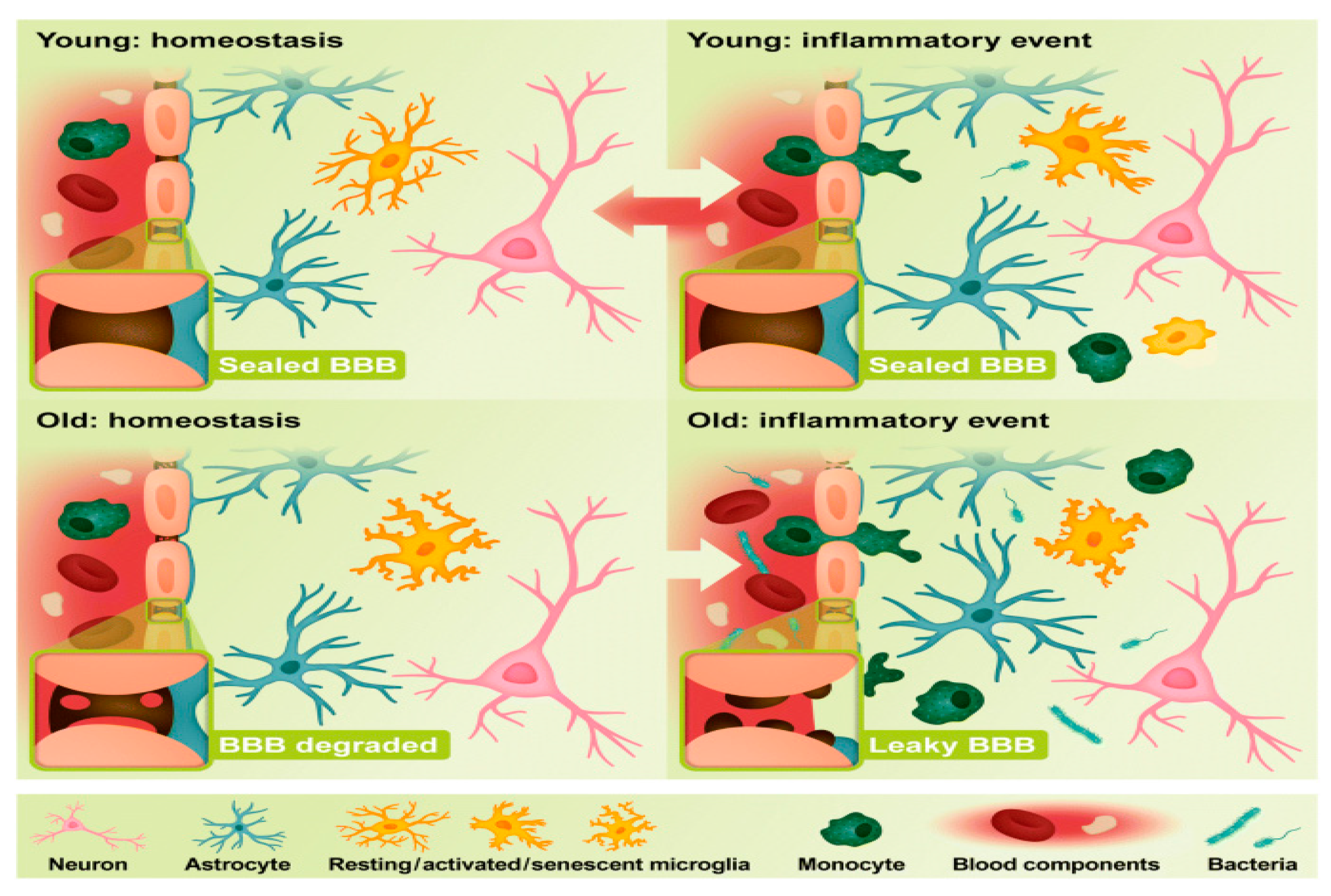

3.1. Age related changes in microglia and AD assimilation

3.2. Relationship between microglial activation, inflammasome and gut microbiomes.

4. Targeting inflammation and modification of microglial activation can be an effective therapeutic target for treating AD

4.1. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of AD

4.2. AD treatment strategy by modification of inflammatory response by microglia

5. Future prospects of neuroinflammation as a potential therapeutic target to treat AD

6. Conclusion and future direction

References

- A MCKENZIE, J. , J SPIELMAN, L., B POINTER, C., R LOWRY, J., BAJWA, E., W LEE, C. & KLEGERIS, A. 2017. Neuroinflammation as a common mechanism associated with the modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Current aging science, 10, 158-176.

- Aiello, A.; Farzaneh, F.; Candore, G.; Caruso, C.; Davinelli, S.; Gambino, C.M.; Ligotti, M.E.; Zareian, N.; Accardi, G. Immunosenescence and Its Hallmarks: How to Oppose Aging Strategically? A Review of Potential Options for Therapeutic Intervention. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachiller, S.; Jiménez-Ferrer, I.; Paulus, A.; Yang, Y.; Swanberg, M.; Deierborg, T.; Boza-Serrano, A. Microglia in Neurological Diseases: A Road Map to Brain-Disease Dependent-Inflammatory Response. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klegeris, A.; Bajwa, E. Neuroinflammation as a mechanism linking hypertension with the increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 2342–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinton, R.D.; Yao, J.; Yin, F.; Mack, W.J.; Cadenas, E. Perimenopause as a neurological transition state. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D.R. Role of Microglia in Age-Related Changes to the Nervous System. Sci. World J. 2009, 9, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BURGALETTO, C. , MUNAFÒ, A., DI BENEDETTO, G., DE FRANCISCI, C., CARACI, F., DI MAURO, R., BUCOLO, C., BERNARDINI, R. & CANTARELLA, G. 2020. The immune system on the TRAIL of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 17, 1-11.

- Chen, X.-Q.; Mobley, W.C. Alzheimer Disease Pathogenesis: Insights From Molecular and Cellular Biology Studies of Oligomeric Aβ and Tau Species. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cribbs, D.H.; Berchtold, N.C.; Perreau, V.; Coleman, P.D.; Rogers, J.; Tenner, A.J.; Cotman, C.W. Extensive innate immune gene activation accompanies brain aging, increasing vulnerability to cognitive decline and neurodegeneration: a microarray study. J. Neuroinflamm. 2012, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csölle, C.; Sperlágh, B. Peripheral origin of IL-1β production in the rodent hippocampus under in vivo systemic bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge and its regulation by P2X7 receptors. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010, 219, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C. Microglia and neurodegeneration: The role of systemic inflammation. Glia 2012, 61, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DANEMAN, R. & PRAT, A. 2015. The blood–brain barrier. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 7, a020412.

- DE ZOETE, M. R. , PALM, N. W., ZHU, S. & FLAVELL, R. A. 2014. Inflammasomes. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 6, a016287.

- Dempsey, C.; Rubio-Araiz, A.; Bryson, K.J.; Finucane, O.; Larkin, C.; Mills, E.L.; Robertson, A.A.B.; Cooper, M.A.; O'Neill, L.A.J.; Lynch, M.A. Inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome with MCC950 promotes non-phlogistic clearance of amyloid-β and cognitive function in APP/PS1 mice. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2017, 61, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEZFULIAN, M. 2018. A new Alzheimer's disease cell model using B cells to induce beta amyloid plaque formation and increase TNF alpha expression. International Immunopharmacology, 59, 106-112.

- Di Benedetto, G.; Burgaletto, C.; Carta, A.R.; Saccone, S.; Lempereur, L.; Mulas, G.; Loreto, C.; Bernardini, R.; Cantarella, G. Beneficial effects of curtailing immune susceptibility in an Alzheimer’s disease model. J. Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disabato, D.J.; Quan, N.; Godbout, J.P. Neuroinflammation: the devil is in the details. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139 (Suppl. 2), 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erta, M.; Quintana, A.; Hidalgo, J. Interleukin-6, a Major Cytokine in the Central Nervous System. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 8, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAKHOURY, M. 2018. Microglia and astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease: implications for therapy. Current neuropharmacology, 16, 508-518.

- Ferrari, D.P.; Bortolanza, M.; Del Bel, E.A. Interferon-γ Involvement in the Neuroinflammation Associated with Parkinson’s Disease and L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebich, B.L.; Batista, C.R.A.; Saliba, S.W.; Yousif, N.M.; de Oliveira, A.C.P. Role of Microglia TLRs in Neurodegeneration. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.K.Y.; Hung, K.-W.; Yuen, M.Y.F.; Zhou, X.; Mak, D.S.Y.; Chan, I.C.W.; Cheung, T.H.; Zhang, B.; Fu, W.-Y.; Liew, F.Y.; et al. IL-33 ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology and cognitive decline. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, E2705–E2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Shen, Q.; Xu, P.; Luo, J.J.; Tang, Y. Phagocytosis of Microglia in the Central Nervous System Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2014, 49, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FU, W.-Y. , WANG, X. & IP, N. Y. 2018. Targeting neuroinflammation as a therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease: mechanisms, drug candidates, and new opportunities. ACS chemical neuroscience, 10, 872-879.

- Galatro, T.F.; Holtman, I.R.; Lerario, A.M.; Vainchtein, I.D.; Brouwer, N.; Sola, P.R.; Veras, M.M.; Pereira, T.F.; Leite, R.E.P.; Möller, T.; et al. Transcriptomic analysis of purified human cortical microglia reveals age-associated changes. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameiro, C.M.; Romão, F.; Castelo-Branco, C. Menopause and aging: Changes in the immune system—A review. Maturitas 2010, 67, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginhoux, F.; Lim, S.; Hoeffel, G.; Low, D.; Huber, T. Origin and differentiation of microglia. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2013, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GLEICHMAN, A. J. & CARMICHAEL, S. T. 2020. Glia in neurodegeneration: Drivers of disease or along for the ride? Neurobiology of Disease, 142, 104957.

- Golde, T.E. Harnessing Immunoproteostasis to Treat Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neuron 2019, 101, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouras, G.K.; Olsson, T.T.; Hansson, O. β-amyloid Peptides and Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer's Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabert, K.; Michoel, T.; Karavolos, M.H.; Clohisey, S.; Baillie, J.K.; Stevens, M.P.; Freeman, T.C.; Summers, K.M.; McColl, B.W. Microglial brain region−dependent diversity and selective regional sensitivities to aging. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUILLOT-SESTIER, M.-V. , DOTY, K. R., GATE, D., RODRIGUEZ JR, J., LEUNG, B. P., REZAI-ZADEH, K. & TOWN, T. 2015. Il10 deficiency rebalances innate immunity to mitigate Alzheimer-like pathology. Neuron, 85, 534-548.

- HANSLIK, K. L. & ULLAND, T. K. 2020. The role of microglia and the Nlrp3 inflammasome in Alzheimer's disease. Frontiers in Neurology, 11, 570711.

- Hein, A.M.; O’banion, M.K. Neuroinflammation and Memory: The Role of Prostaglandins. Mol. Neurobiol. 2009, 40, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HENEKA, M. T. , CARSON, M. J., EL KHOURY, J., LANDRETH, G. E., BROSSERON, F., FEINSTEIN, D. L., JACOBS, A. H., WYSS-CORAY, T., VITORICA, J. & RANSOHOFF, R. M. 2015. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. The Lancet Neurology, 14, 388-405.

- Heneka, M.T.; Kummer, M.P.; Stutz, A.; Delekate, A.; Schwartz, S.; Vieira-Saecker, A.; Griep, A.; Axt, D.; Remus, A.; Tzeng, T.-C.; et al. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature 2013, 493, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilzendeger, A.M.; Shenoy, V.; Raizada, M.K.; Katovich, M.J. Neuroinflammation in Pulmonary Hypertension: Concept, Facts, and Relevance. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2014, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Beja-Glasser, V.F.; Nfonoyim, B.M.; Frouin, A.; Li, S.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Merry, K.M.; Shi, Q.; Rosenthal, A.; Barres, B.A.; et al. Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science 2016, 352, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lu, D.; Lu, Z.; Cai, W. Update of inflammasome activation in microglia/macrophage in aging and aging-related disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2019, 25, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamada, M.; Irahara, M.; Maegawa, M.; Yasui, T.; Yamano, S.; Yamada, M.; Tezuka, M.; Kasai, Y.; Deguchi, K.; Ohmoto, Y.; et al. B cell subsets in postmenopausal women and the effect of hormone replacement therapy. Maturitas 2001, 37, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettenmann, H.; Hanisch, U.-K.; Noda, M.; Verkhratsky, A. Physiology of Microglia. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 461–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.S.; Patro, N.; Patro, I.K. A Sequential Study of Age-Related Lipofuscin Accumulation in Hippocampus and Striate Cortex of Rats. Ann. Neurosci. 2018, 25, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Barres, B.A. Reactive Astrocytes: Production, Function, and Therapeutic Potential. Immunity 2017, 46, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhout, I.A.; Murray, T.E.; Richards, C.M.; Klegeris, A. Potential neurotoxic activity of diverse molecules released by microglia. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 148, 105117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Peng, G. Neuroinflammation as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Alzheimer’s Disease. Clin. Interv. Aging 2022, ume 17, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lučiūnaitė, A.; McManus, R.M.; Jankunec, M.; Rácz, I.; Dansokho, C.; Dalgėdienė, I.; Schwartz, S.; Brosseron, F.; Heneka, M.T. Soluble Aβ oligomers and protofibrils induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia. J. Neurochem. 2019, 155, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lull, M.E.; Block, M.L. Microglial activation and chronic neurodegeneration. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Choi, B.-R.; Chung, C.; Min, S.S.; Jeon, W.K.; Han, J.-S. Chronic brain inflammation causes a reduction in GluN2A and GluN2B subunits of NMDA receptors and an increase in the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in the hippocampus. Mol. Brain 2014, 7, 33–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Xing, C.; Long, W.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, R.-F. Impact of microbiota on central nervous system and neurological diseases: the gut-brain axis. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manly, J.; Merchant, C.; Jacobs, D.; Small, S.; Bell, K.; Ferin, M.; Mayeux, R. Endogenous estrogen levels and Alzheimer’s disease among postmenopausal women. Neurology 2000, 54, 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MCGEER, P. L. , ROGERS, J. & MCGEER, E. G. 2016. Inflammation, antiinflammatory agents, and Alzheimer’s disease: the last 22 years. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 54, 853-857.

- Mejias, N.H.; Martinez, C.C.; Stephens, M.E.; de Rivero Vaccari, J.P. Contribution of the inflammasome to inflammaging. J. Inflamm. 2018, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel-Álvarez, M.; Santos-Lozano, A.; Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Fiuza-Luces, C.; Pareja-Galeano, H.; Garatachea, N.; Lucia, A. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs as a Treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Treatment Effect. Drugs Aging 2015, 32, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MISHRA, A. & BRINTON, R. D. 2018. Inflammation: bridging age, menopause and APOEε4 genotype to Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 10, 312.

- Montagne, A.; Barnes, S.R.; Sweeney, M.D.; Halliday, M.R.; Sagare, A.P.; Zhao, Z.; Toga, A.W.; Jacobs, R.E.; Liu, C.Y.; Amezcua, L.; et al. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in the Aging Human Hippocampus. Neuron 2015, 85, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosconi, L.; Berti, V.; Guyara-Quinn, C.; McHugh, P.; Petrongolo, G.; Osorio, R.S.; Connaughty, C.; Pupi, A.; Vallabhajosula, S.; Isaacson, R.S.; et al. Perimenopause and emergence of an Alzheimer’s bioenergetic phenotype in brain and periphery. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0185926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MULLER, G. C. , GOTTLIEB, M. G. V., CORREA, B. L., GOMES FILHO, I., MORESCO, R. N. & BAUER, M. E. 2015. The inverted CD4: CD8 ratio is associated with gender-related changes in oxidative stress during aging. Cellular immunology, 296, 149-154.

- Newcombe, E.A.; Camats-Perna, J.; Silva, M.L.; Valmas, N.; Huat, T.J.; Medeiros, R. Inflammation: the link between comorbidities, genetics, and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’neil, S.M.; Witcher, K.G.; McKim, D.B.; Godbout, J.P. Forced turnover of aged microglia induces an intermediate phenotype but does not rebalance CNS environmental cues driving priming to immune challenge. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, A.; Kathawala, K.; Li, J.; Chen, C.; Shan, Z.; Cao, X.; Wang, Y.-J.; Garg, S.; Zhou, X.-F. Self-nanomicellizing solid dispersion of edaravone: part II: in vivo assessment of efficacy against behavior deficits and safety in Alzheimer’s disease model. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2018, ume 12, 2111–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRINCE, M. J. , WIMO, A., GUERCHET, M. M., ALI, G. C., WU, Y.-T. & PRINA, M. 2015. World Alzheimer Report 2015-The Global Impact of Dementia: An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends.

- Prinz, M.; Jung, S.; Priller, J. Microglia Biology: One Century of Evolving Concepts. Cell 2019, 179, 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, A.C.; Milton, F.A.; Cvoro, A.; Sieglaff, D.H.; Campos, J.C.; Bernardes, A.; Filgueira, C.S.; Lindemann, J.L.; Deng, T.; Neves, F.A.; et al. Mechanisms of Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor γ Regulation by Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 2015, 13, e004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QIAN, L. , HONG, J.-S. & FLOOD, P. 2006. Role of microglia in inflammation-mediated degeneration of dopaminergic neurons: neuroprotective effect of interleukin 10. Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders. Springer.

- Ramesh, G.; MacLean, A.G.; Philipp, M.T. Cytokines and Chemokines at the Crossroads of Neuroinflammation, Neurodegeneration, and Neuropathic Pain. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 480739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SANCHEZ-MEJIA, R. O. , NEWMAN, J. W., TOH, S., YU, G.-Q., ZHOU, Y., HALABISKY, B., CISSÉ, M., SCEARCE-LEVIE, K., CHENG, I. H. & GAN, L. 2008. Phospholipase A2 reduction ameliorates cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature neuroscience, 11, 1311-1318.

- SCHELTENS, P. , DE STROOPER, B., KIVIPELTO, M., HOLSTEGE, H., CHÉTELAT, G. & TEUNISSEN, C. van der Flier, WM (2021, ). Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet, 397, 1577-1590. 24 April.

- Schetters, S.T.T.; Gomez-Nicola, D.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Van Kooyk, Y. Neuroinflammation: Microglia and T Cells Get Ready to Tango. Front. Immunol. 2018, 8, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHEN, H. , GUAN, Q., ZHANG, X., YUAN, C., TAN, Z., ZHAI, L., HAO, Y., GU, Y. & HAN, C. 2020. New mechanism of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease: the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome mediated by gut microbiota. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 100, 109884.

- Spangenberg, E.E.; Lee, R.J.; Najafi, A.R.; Rice, R.A.; Elmore, M.R.P.; Blurton-Jones, M.; West, B.L.; Green, K.N. Eliminating microglia in Alzheimer’s mice prevents neuronal loss without modulating amyloid-β pathology. Brain 2016, 139, 1265–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takechi, R.; Lam, V.; Brook, E.; Giles, C.; Fimognari, N.; Mooranian, A.; Al-Salami, H.; Coulson, S.H.; Nesbit, M.; Mamo, J.C.L. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction Precedes Cognitive Decline and Neurodegeneration in Diabetic Insulin Resistant Mouse Model: An Implication for Causal Link. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 399–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- THAWKAR, B. S. & KAUR, G. 2019. Inhibitors of NF-κB and P2X7/NLRP3/Caspase 1 pathway in microglia: Novel therapeutic opportunities in neuroinflammation induced early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of neuroimmunology, 326, 62-74.

- Uri-Belapolsky, S.; Shaish, A.; Eliyahu, E.; Grossman, H.; Levi, M.; Chuderland, D.; Ninio-Many, L.; Hasky, N.; Shashar, D.; Almog, T.; et al. Interleukin-1 deficiency prolongs ovarian lifespan in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 12492–12497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VENEGAS, C. , KUMAR, S., FRANKLIN, B. S., DIERKES, T., BRINKSCHULTE, R., TEJERA, D., VIEIRA-SAECKER, A., SCHWARTZ, S., SANTARELLI, F. & KUMMER, M. P. 2017. Microglia-derived ASC specks cross-seed amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature, 552, 355-361.

- Villeda, S.A.; Luo, J.; Mosher, K.I.; Zou, B.; Britschgi, M.; Bieri, G.; Stan, T.M.; Fainberg, N.; Ding, Z.; Eggel, A.; et al. The ageing systemic milieu negatively regulates neurogenesis and cognitive function. Nature 2011, 477, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VON BERNHARDI, R. , EUGENÍN-VON BERNHARDI, L. & EUGENÍN, J. 2015. Microglial cell dysregulation in brain aging and neurodegeneration. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 7, 124.

- WALKER, K. A. , HOOGEVEEN, R. C., FOLSOM, A. R., BALLANTYNE, C. M., KNOPMAN, D. S., WINDHAM, B. G., JACK, C. R. & GOTTESMAN, R. F. 2017. Midlife systemic inflammatory markers are associated with late-life brain volume: the ARIC study. Neurology, 89, 2262-2270.

- Wang, H.-M.; Zhang, T.; Huang, J.-K.; Xiang, J.-Y.; Chen, J.-J.; Fu, J.-L.; Zhao, Y.-W. Edaravone Attenuates the Proinflammatory Response in Amyloid-β-Treated Microglia by Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated IL-1β Secretion. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 1113–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willette, A.A.; Coe, C.L.; Birdsill, A.C.; Bendlin, B.B.; Colman, R.J.; Alexander, A.L.; Allison, D.B.; Weindruch, R.H.; Johnson, S.C. Interleukin-8 and interleukin-10, brain volume and microstructure, and the influence of calorie restriction in old rhesus macaques. AGE 2013, 35, 2215–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; He, D.; Bai, Y. Microglia-Mediated Inflammation and Neurodegenerative Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 53, 6709–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.; Yao, J.; Sancheti, H.; Feng, T.; Melcangi, R.C.; Morgan, T.E.; Finch, C.E.; Pike, C.J.; Mack, W.J.; Cadenas, E.; et al. The perimenopausal aging transition in the female rat brain: decline in bioenergetic systems and synaptic plasticity. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 2282–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Zhao, F.; Chojnacki, J.E.; Fulp, J.; Klein, W.L.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, X. NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitor Ameliorates Amyloid Pathology in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 55, 1977–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youm, Y.-H.; Grant, R.W.; McCabe, L.R.; Albarado, D.C.; Nguyen, K.Y.; Ravussin, A.; Pistell, P.; Newman, S.; Carter, R.; Laque, A.; et al. Canonical Nlrp3 Inflammasome Links Systemic Low-Grade Inflammation to Functional Decline in Aging. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Hu, H.; Zhao, M.; Sun, L. Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Target for Therapeutic Intervention. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Neuro-regulatory factors | Group | Name | Origin | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | Interleukins | IL-6 | IL-6 is produced by activated astrogliosis when neurons are injured. | Interleukins increase neuronal survival but are involved in several brain diseases | (Erta et al., 2012) |

| IL-1β | IL-1β is induced by Bacterial endotoxin | Causes neurotoxicity by producing excess glutamate | (Csölle and Sperlagh, 2010) | ||

| Type-IIInterferon | IFN-γ | IFN-γ is activated by natural killer cell (NK) .T-Cell may also induce IFN-γ. | Activates microglia and causes neuro-toxicity in Parkinson disease. | (Ferrari et al., 2021) | |

| The tumor necrosis factor, adipokine | TNF-α | TNF-α is generated by macrophages during systemic inflammation. | Involves in amyloid plaque production during Alzheimer’s disease. | (Dezfulian, 2018) | |

| Chemokines | Interleukin | IL-8R | Macrophages | Causes neurotoxicity by amyloid-beta formation. | (Willette et al., 2013) |

| Toll like receptor | TLR-4 | Extracellular factors induce Toll-like receptor | Mediates activation of microglial cell. TLR-4 reduces tau hyper-phosphorylation but induce amyloid beta production. | (Fiebich et al., 2018) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).