1. Introduction

Changes in lifestyle have been modifying nutritional culture throughout history, transforming our traditional dietary habits since childhood1. Likewise, the state of confinement COVID-19 has implied changes in the life habits and dietary profiles of the population2.

Health is the favorable result of the interaction between various determinants (biological, sociocultural, linked to lifestyle and health care system) according to the Lalonde3 classification, whose harmony allows optimizing quality of life at the individual and collective level.

The term Quality of Life (QOL) arose in the mid-seventies, as a concept that refers to the perception of well-being by the individual, collecting objective and subjective aspects4. Health-related quality of life (QLRH), or perceived health, integrates those aspects of life directly related to physical, mental, emotional, social functioning and the state of well-being. It is used to assess the impact of chronic diseases and the effectiveness of individual medical treatments on health. Therefore, the conceptual model of HRQOL4 is multidimensional and can be considered as one of the determinants of the level of health that adds the value of quantifying the perception (of the subject) of illness and health, as well as its consequences. Achieving a better quality of life in old age depends on aspects related to lifestyles1.

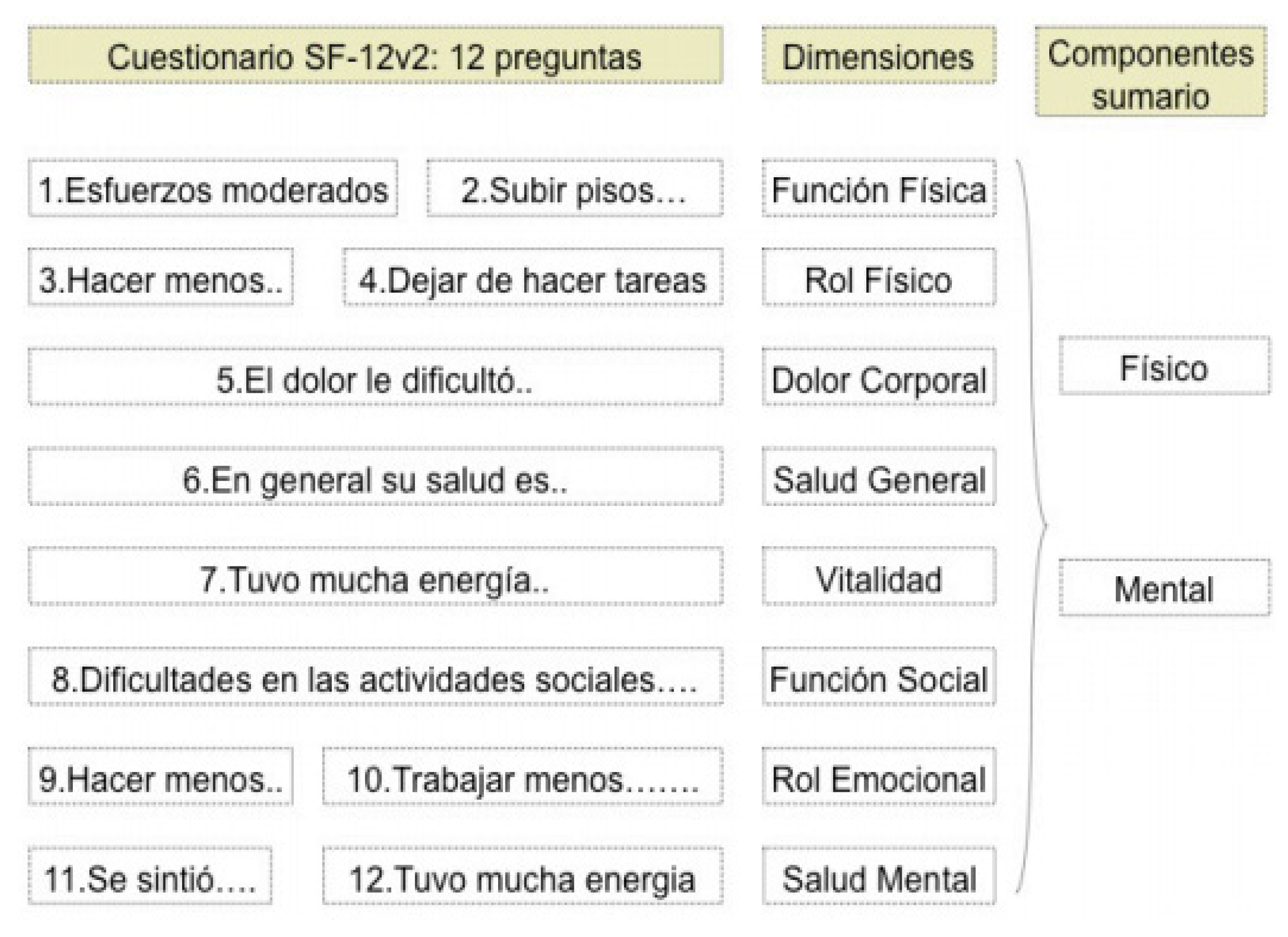

The SF-12v2 is a reduced version of the SF-36 questionnaire, adapted for Spain by Alonso et al (2002)

5, unlike version 1, it is applicable to the general population and to patients with a minimum age of 14 years. This is a self-administered questionnaire, whose completion time is less than 2 minutes, unlike the SF-36 (between 5 and 10 min). It consists of 12 items from the 8 dimensions of the SF-36 that provide a profile of health status: Physical Function (2), Social Function (1), Physical Role (2), Emotional Role (2), Mental Health (2 ), Vitality (1), Body Pain (1) and General Health (1) (

Figure 1)

5.

The Mediterranean diet (DMed) is classically defined as the eating pattern typical of the early sixties in the countries of the Mediterranean area (Greece, southern Italy and Spain)6, characterized by containing a high content of monounsaturated fats and low in fatty acids. fatty.

In Spain, derived from current lifestyles far from a Mediterranean lifestyle, there is a high prevalence of DM2 together with obesity (diabesity)7,8, two of the great epidemics of the 21st century that increase CVD and decrease the (QLRH)9,10. Therefore, it was proposed to assess the effects of MedDM on the quality of life of diabetics.

2. Method

This is a multicenter study in which adult type 2 diabetic patients with poor glycemic control (A1c greater than 7%) from various health centers in Albacete and Cuenca participated during the period between 2018 and 2019. A study is carried out Descriptive observational study to know the usual eating habit and the QLRH. To this end, it is proposed to use it due to its ease of use and after having demonstrated how effective it is to use tools such as the MEDAS-1411 questionnaire to quantify adherence to the MedD and the SF-12v25 to determine the psychological effect that the disease has on their individual and social context.

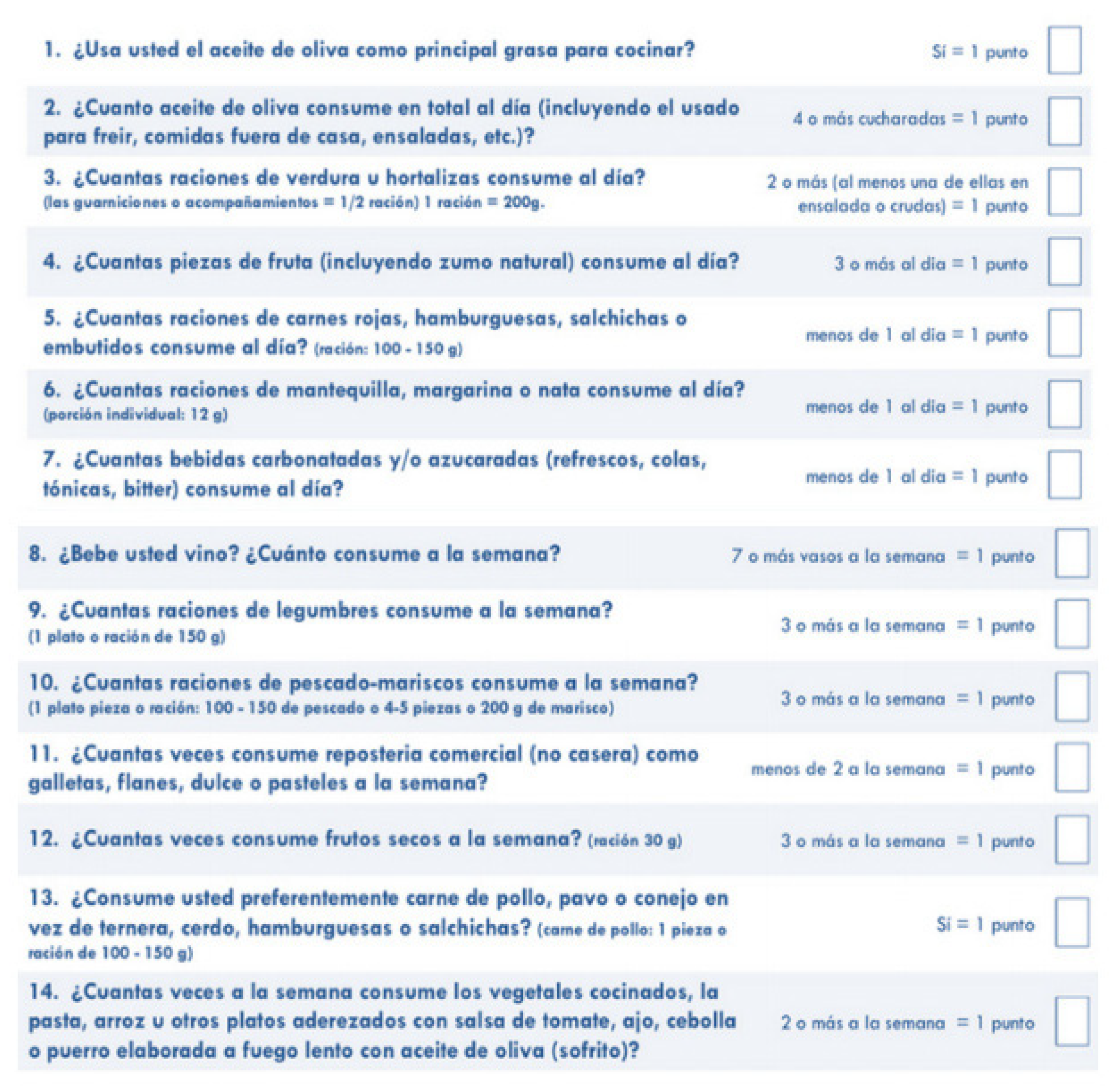

The MEDAS-14

11 questionnaire (

Figure 2), consisting of the assessment of adherence to the MedD based on the 14-point score also validated in the British population. A score greater than or equal to 9 points is a good level of adherence, values less than or equal to 8 are considered poor adherence.

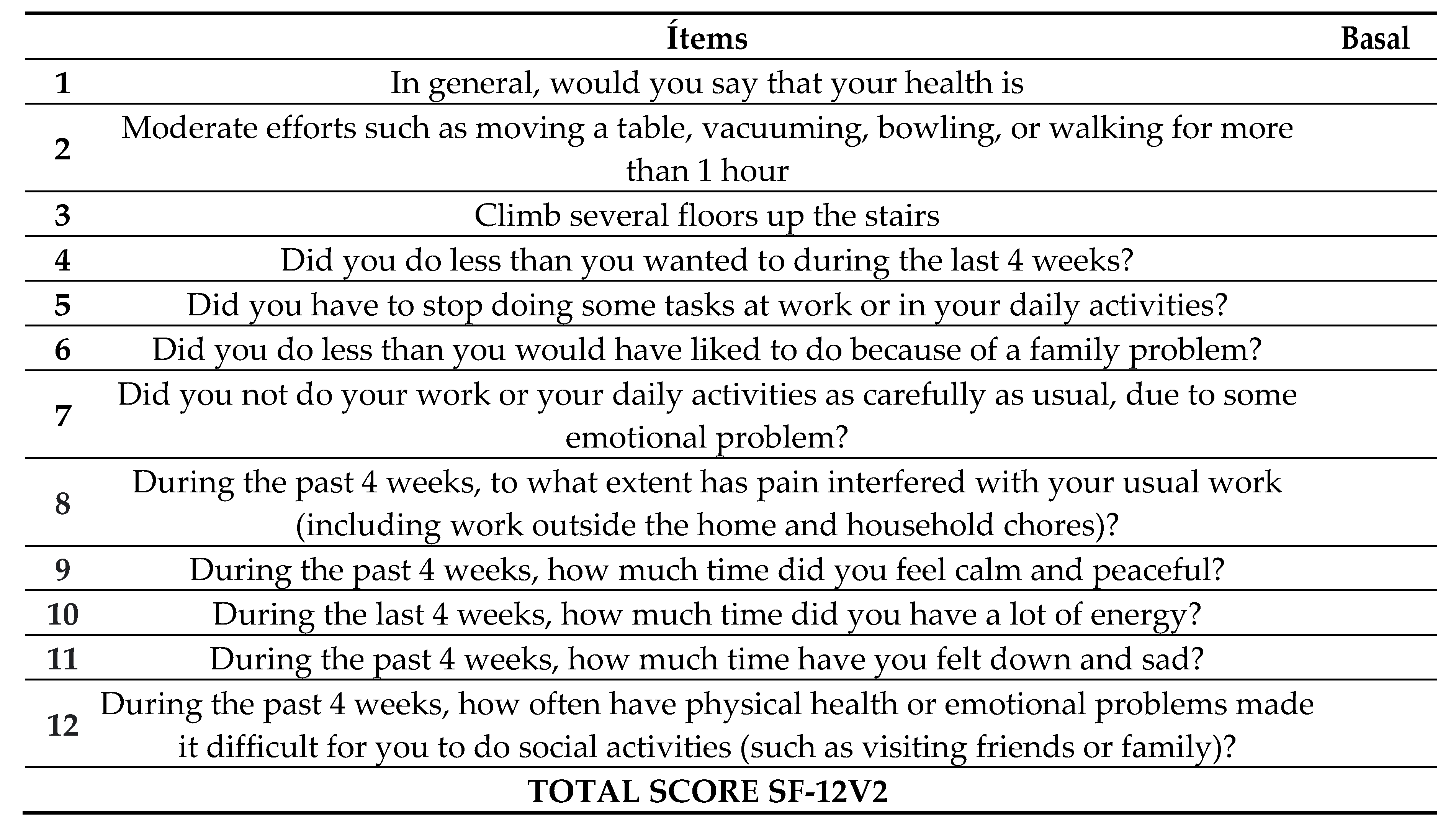

The SF-12v2

5 questionnaire (

Figure 3) is a qualitative variable to assess the initial HRQoL of DM2, using 12 items to provide a profile of the state of general health, well-being, and functional capacity. The version includes two dimensions (physical and mental) through eight health concepts such as general health (personal assessment of health), physical function (extent to which health limits physical activities), physical role (extent to which physical health interferes with work and daily activities), emotional role (extent to which emotional problems interfere with work or other activities), bodily pain (intensity of pain), mental health (general), vitality (feeling of energy and vitality) and social function (degree of physical and emotional health that affect normal social life).

According to the consulted bibliography, if the condition was not met, it is recorded with 0 points. If the condition was met, it is recorded with 1 point; If there are several options, it is recorded with 1,2,3,4 or 5 (from worst to best option) points for the category. However, there is no defined score range to classify HRQoL as good or bad.

2.1. Statistic analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with the statistical package SPSS® (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) in its version 24.0. A descriptive analysis of the variables of interest was carried out, in which their distribution was observed in order to define cut-off points. To measure adherence to MedDM, the MEDAS-14 was assessed, classifying the participants into two categories: high adherence for a score ≥ 9, and low adherence if < 9. The qualitative variables were presented through the frequency distribution of the percentages of each category while in the quantitative variables it was explored whether or not they followed a normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and indicators of central tendency (mean or median) and dispersion (standard deviation or percentiles) were given. The association between these factors was investigated using hypothesis contrast tests, with comparison of proportions when both were qualitative (Chi square, Fisher's exact test); comparisons of means when one of them was quantitative (Student's t test, ANOVA), and if they did not follow a normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskall-Wallis and Friedman in the case of repeated measures. Linear regression tests were performed when the dependent variable was quantitative. In the case of qualitative variables, the relative risk (RR) was calculated for the different proportions and their CIs. The analysis was complemented with graphic representations. The statistical significance level for this study was p ≤ 0.05.

2.2. Ethical aspects

The study was carried out following the recognized Ethics Standards and the Standards of Good Clinical Practice. The data was protected from uses not permitted by persons unrelated to the investigation and confidentiality was respected regarding the Protection of Personal Data and Law 41/2002, of November 14, the basic law regulating patient autonomy and rights. and obligations regarding information and clinical documentation. Therefore, the information generated in this study has been considered strictly confidential, between the participating parties.

3. Results

Throughout the study, 93 adult diabetic patients participated, of which 60% were women with a mean age of 64 +/- 9 years. The BMI at the beginning was 32 kg/m2 (grade I obesity), with a basal glycemia of 158mg/dl and a mean glycosylated hemoglobin of 7.88% (poor glycemic control). That is, the patients presented diabesity with poor metabolic control.

3.1. Assessment of quality of life:

Table 1 shows the results of the 12 items of the SF-12v2 questionnaire on initial HRQoL, compared between women and men:

3.2. Relationship between variables

3.2.1. Adherence to DMED (MEDAS-14):

No significant results are obtained, but it is worth noting:

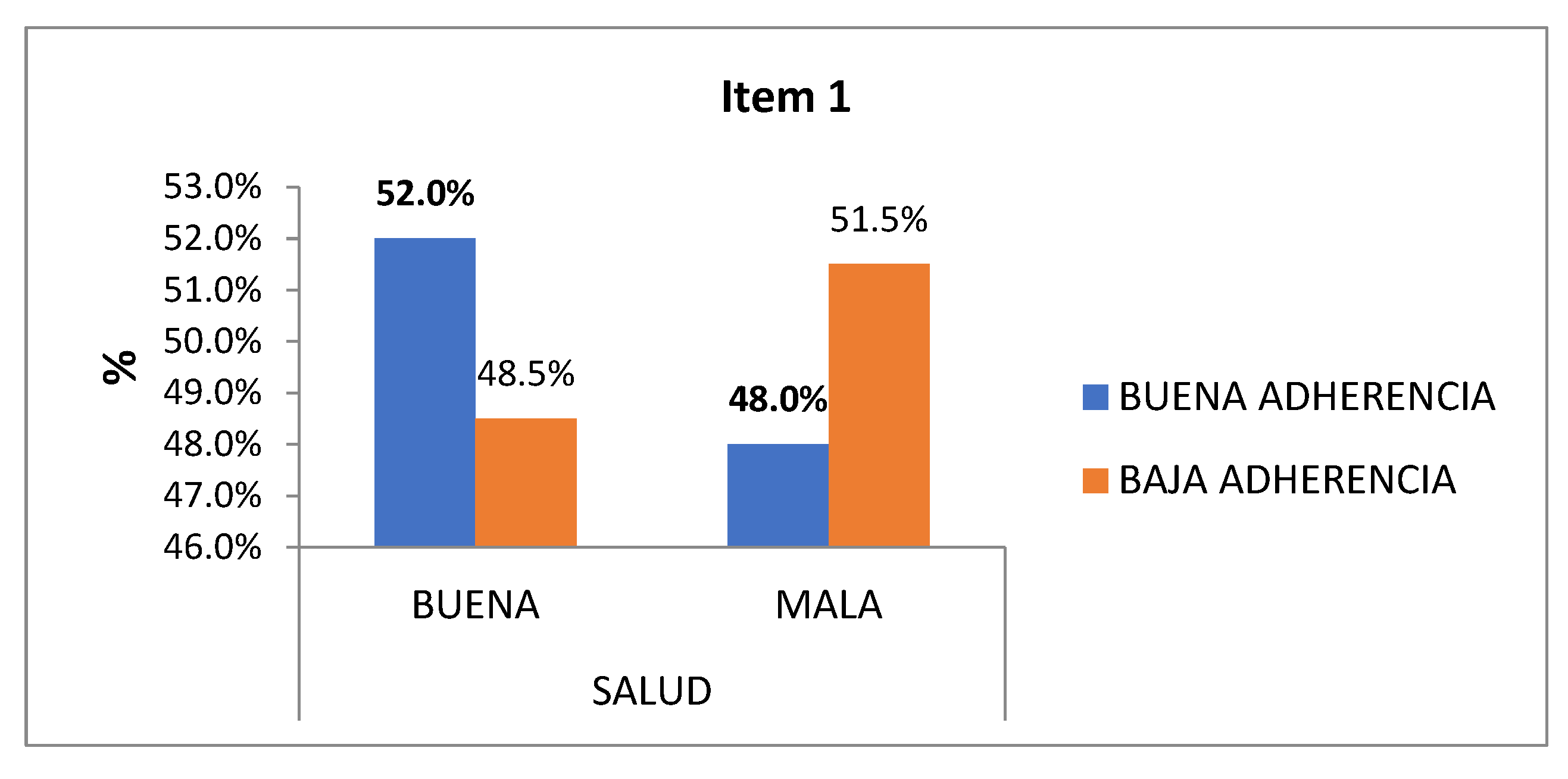

1st General health: After delimiting “good health” and “bad health”, in good adherence the response rates of good conception of their health is 52% compared to 48.5% in low adherence; Likewise, their conception of poor health is higher in low adherence with 51.5% compared to 48% in good adherence (

Figure 4).

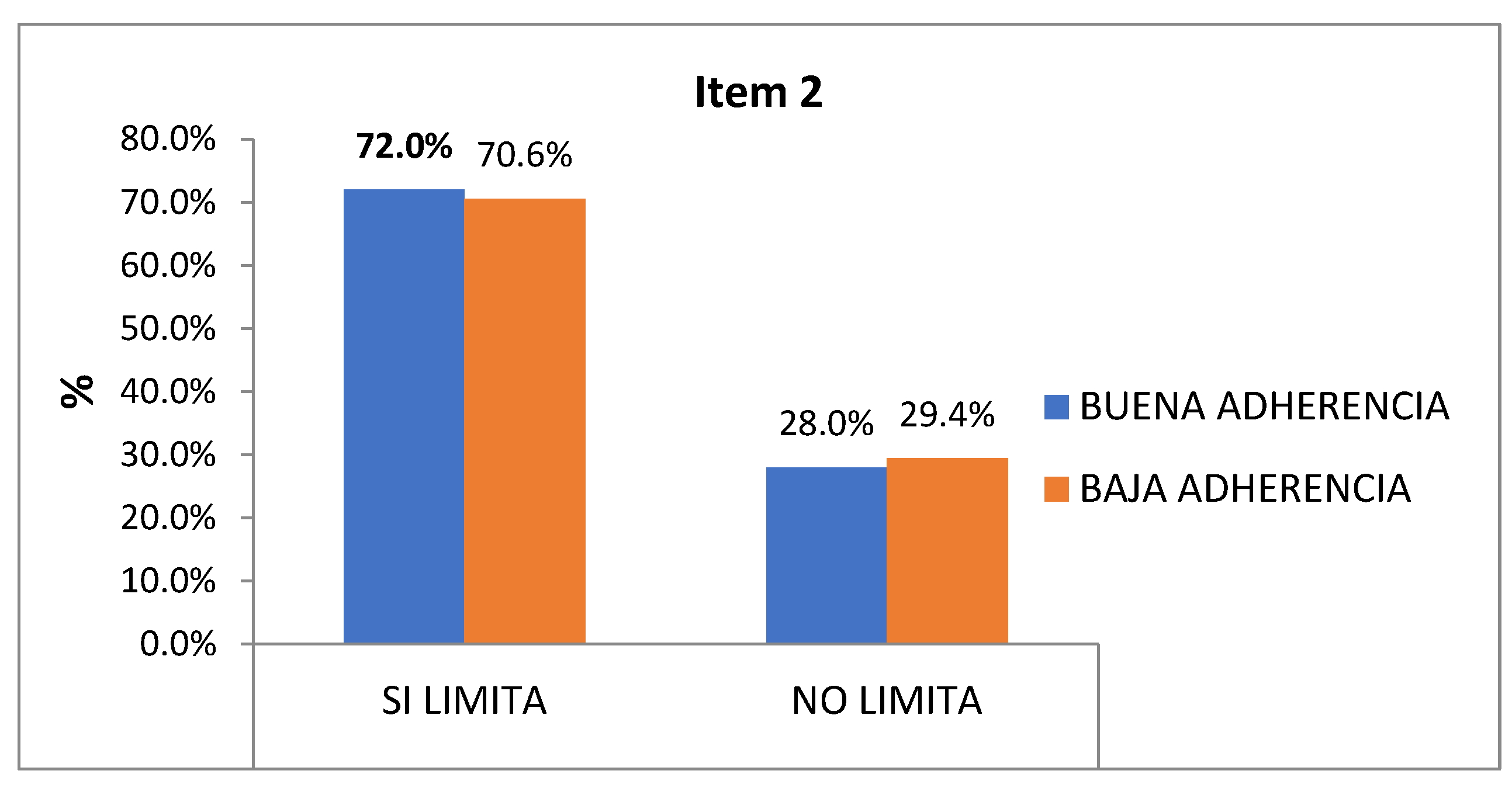

2nd Physical function l: After delimiting "if it limits" and "does not limit", there are similar limitations in both groups both in "if it limits me" (72% vs. 71%), and in "it does not limit me" (28 % vs. 29%) (

Figure 5).

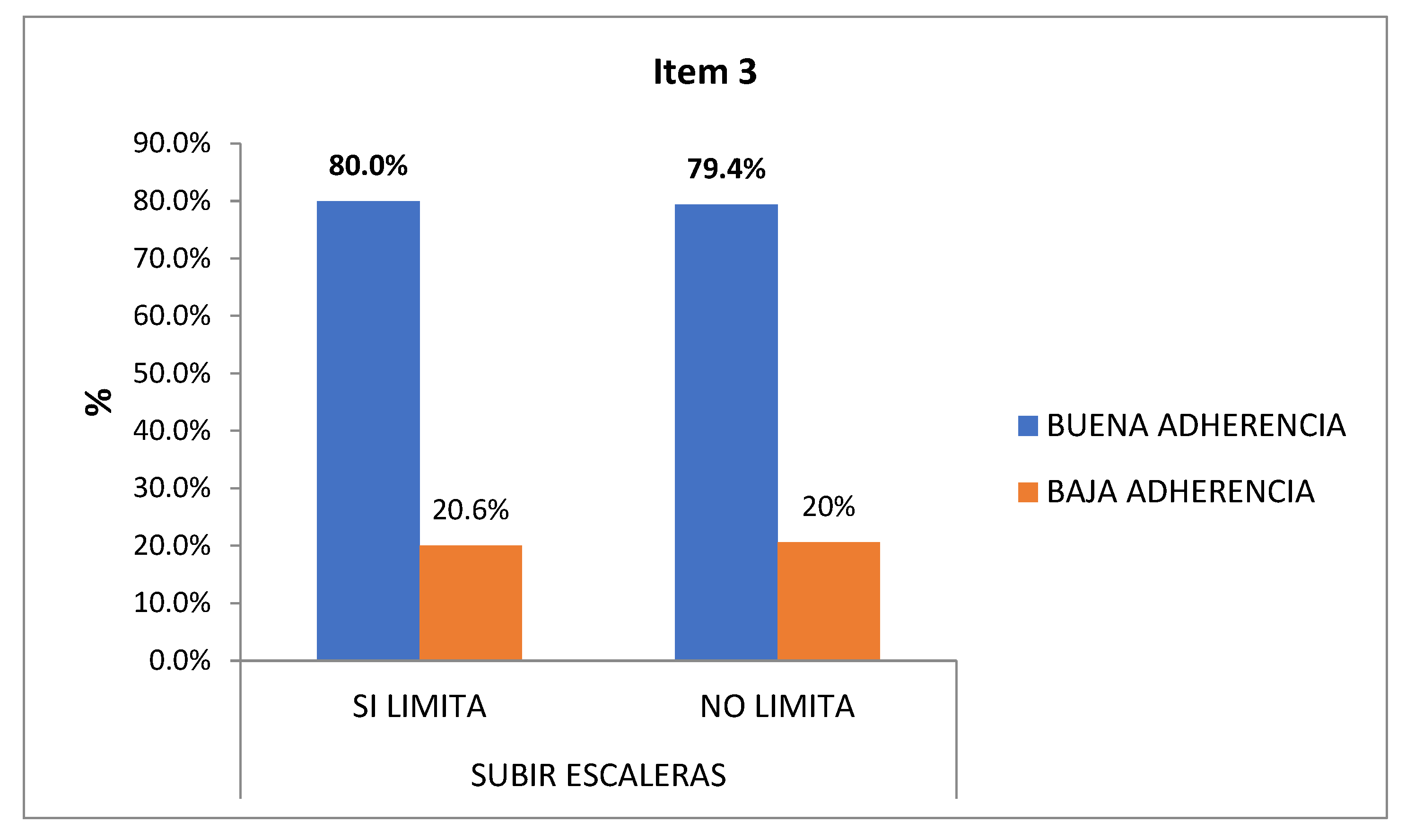

3rd Physical function II: After delimiting "yes it limits" and "does not limit", the 47% with low adherence consider that they are somewhat limited to climb several floors up the stairs, it limits them a lot to the 10% of low adherence compared to the 1% good adherence (

Figure 6).

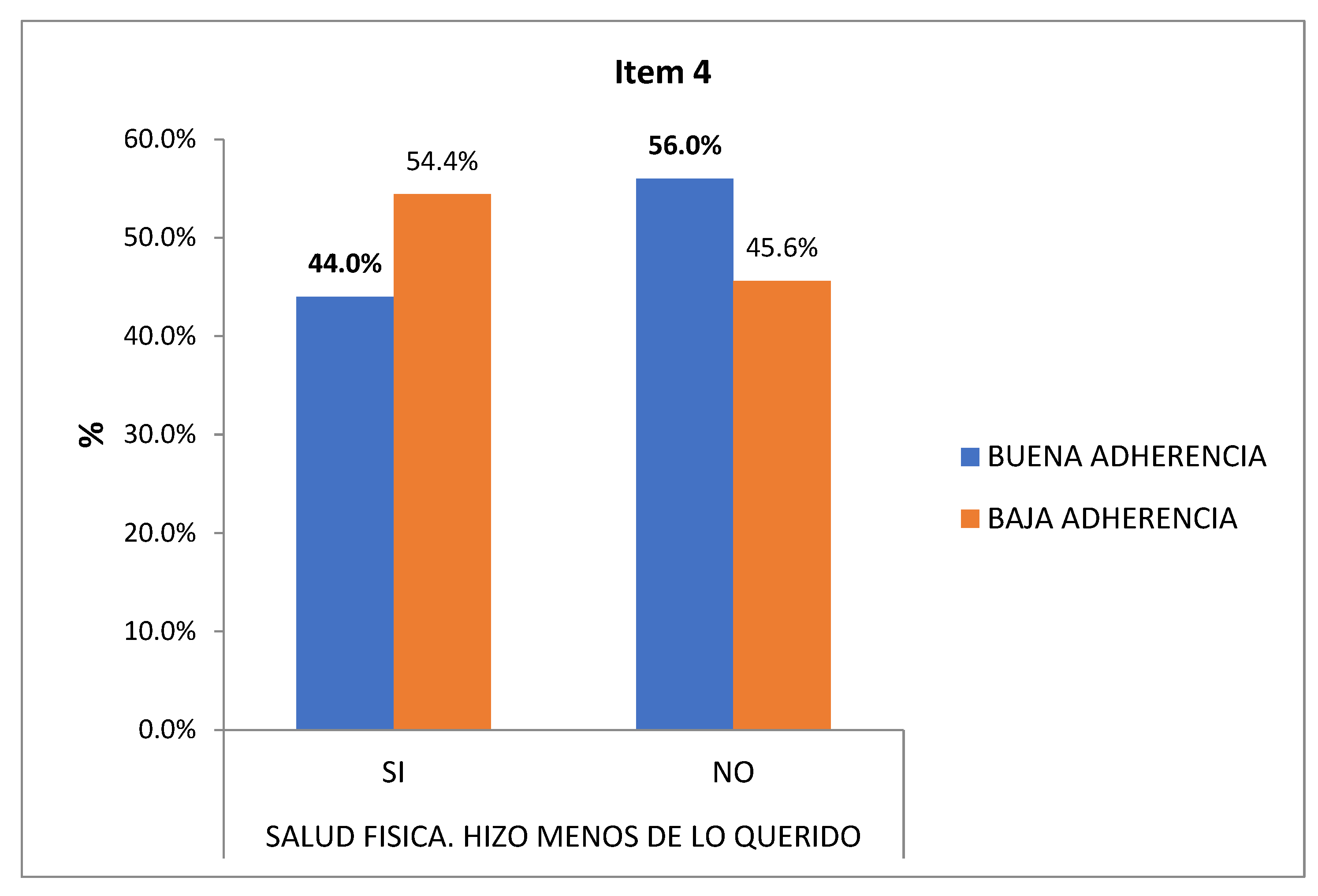

4th Physical Role I: 54.4% of those with low adherence answered affirmatively (they did less than they would have wanted to do) and 56% of those with good adherence answered negatively (they did not do less than they wanted) (

Figure 7).

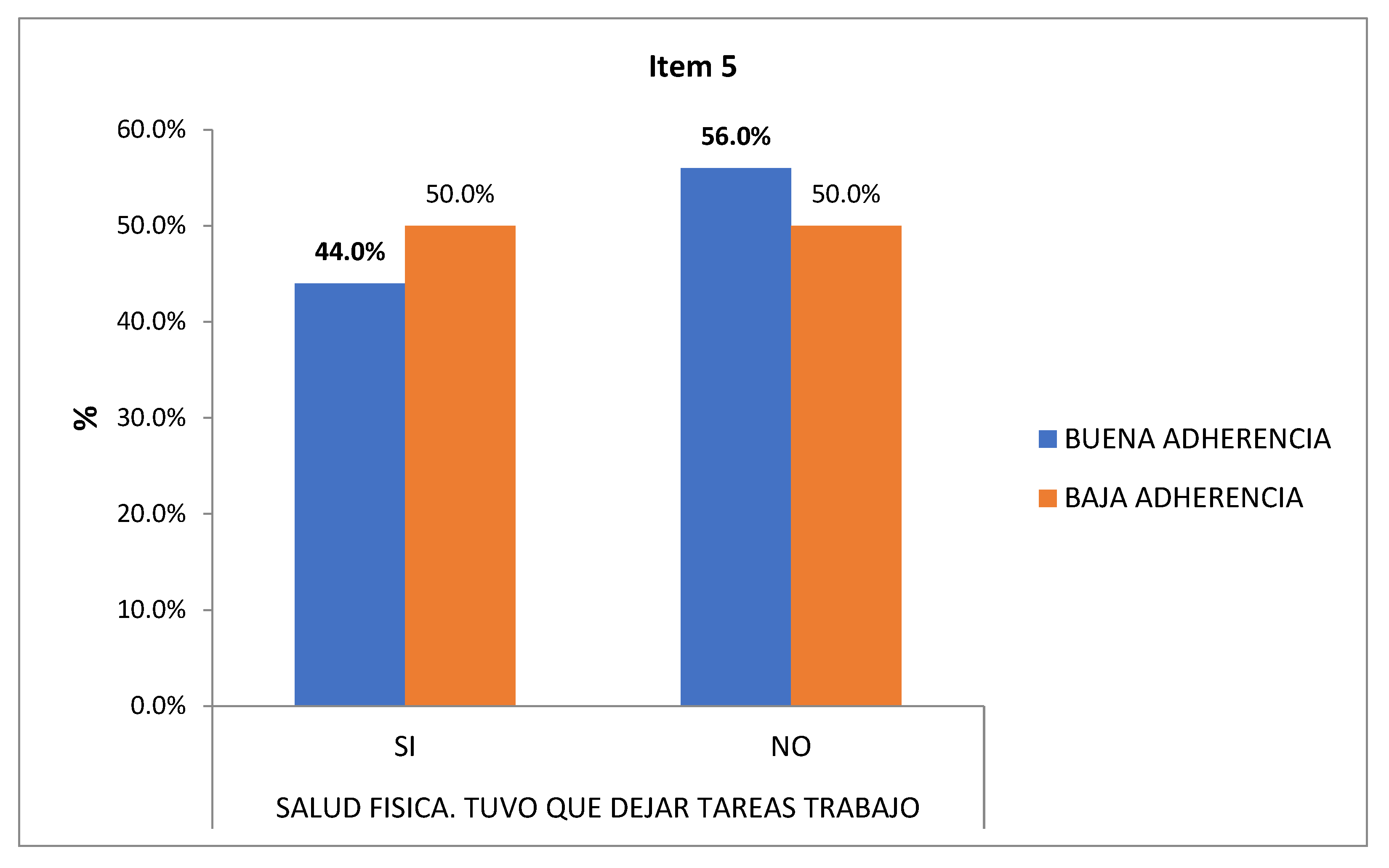

5th Physical role II: 56% of the good adherence did not consider giving up any task at work because of their physique (

Figure 8).

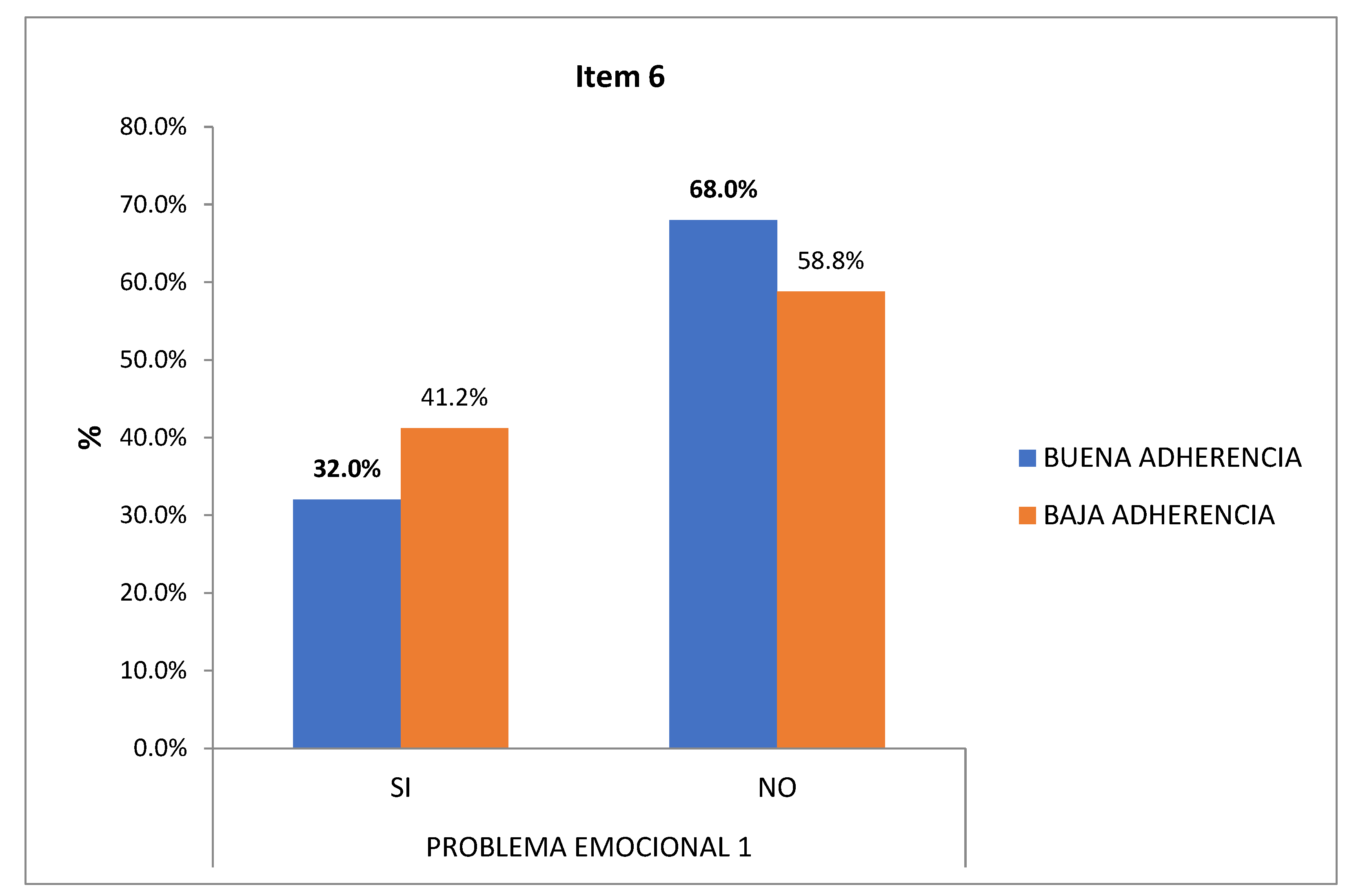

6th Emotional Role I: During the last 4 weeks, 68% with good adherence and 58% with low adherence do not consider having problems at work due to any emotional problem (

Figure 9).

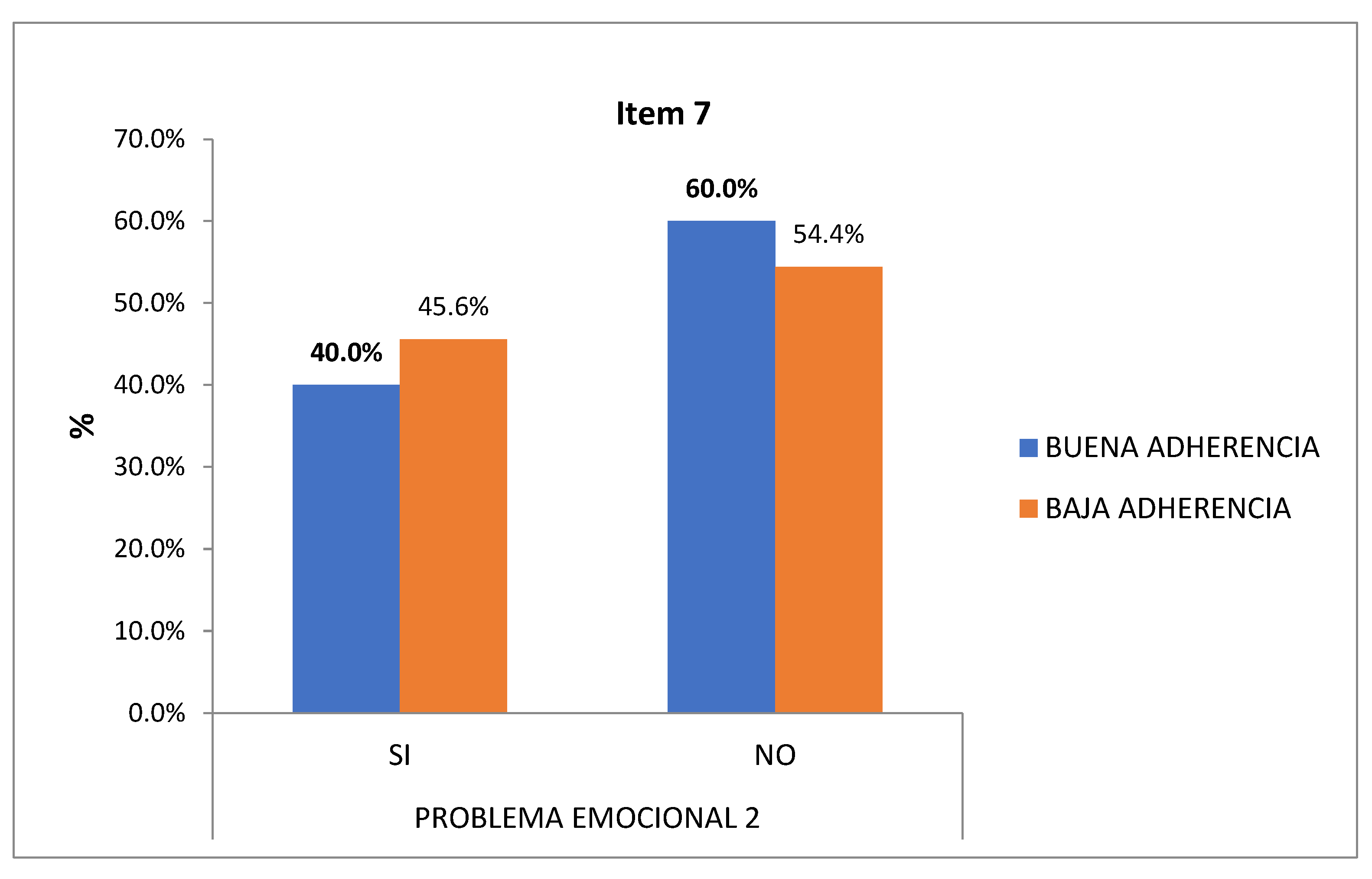

7th Emotional Role II: 60% with good adherence and 55% of those with low adherence did not have to stop doing their daily activities so carefully due to emotional problems (

Figure 10).

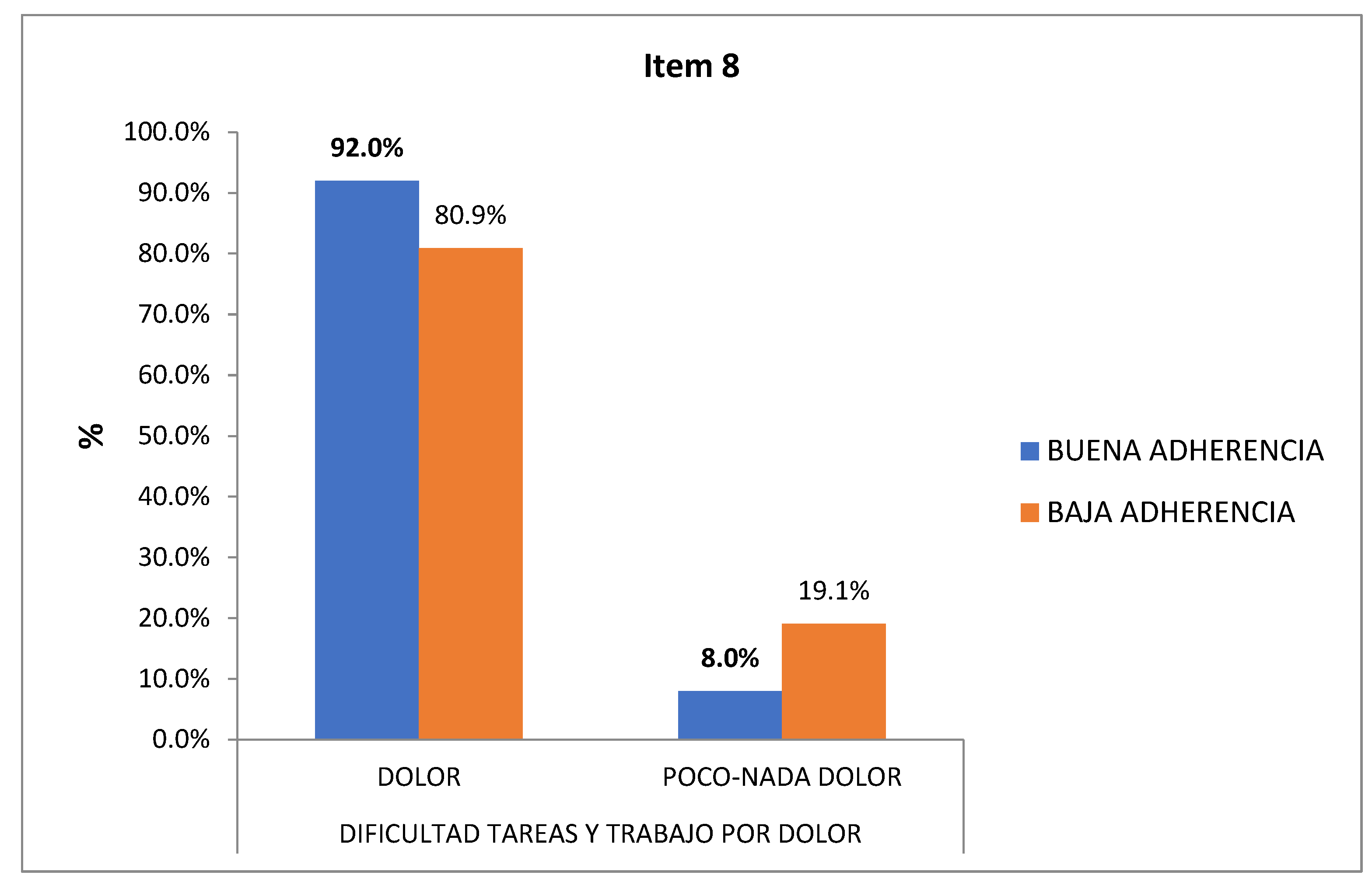

8th Body pain: After delimiting the answers in "pain" and "little/no pain", during the last 4 weeks, both 92% with good adherence and 81% with low adherence considered that they had some degree of pain that made their usual work difficult (

Figure 11).

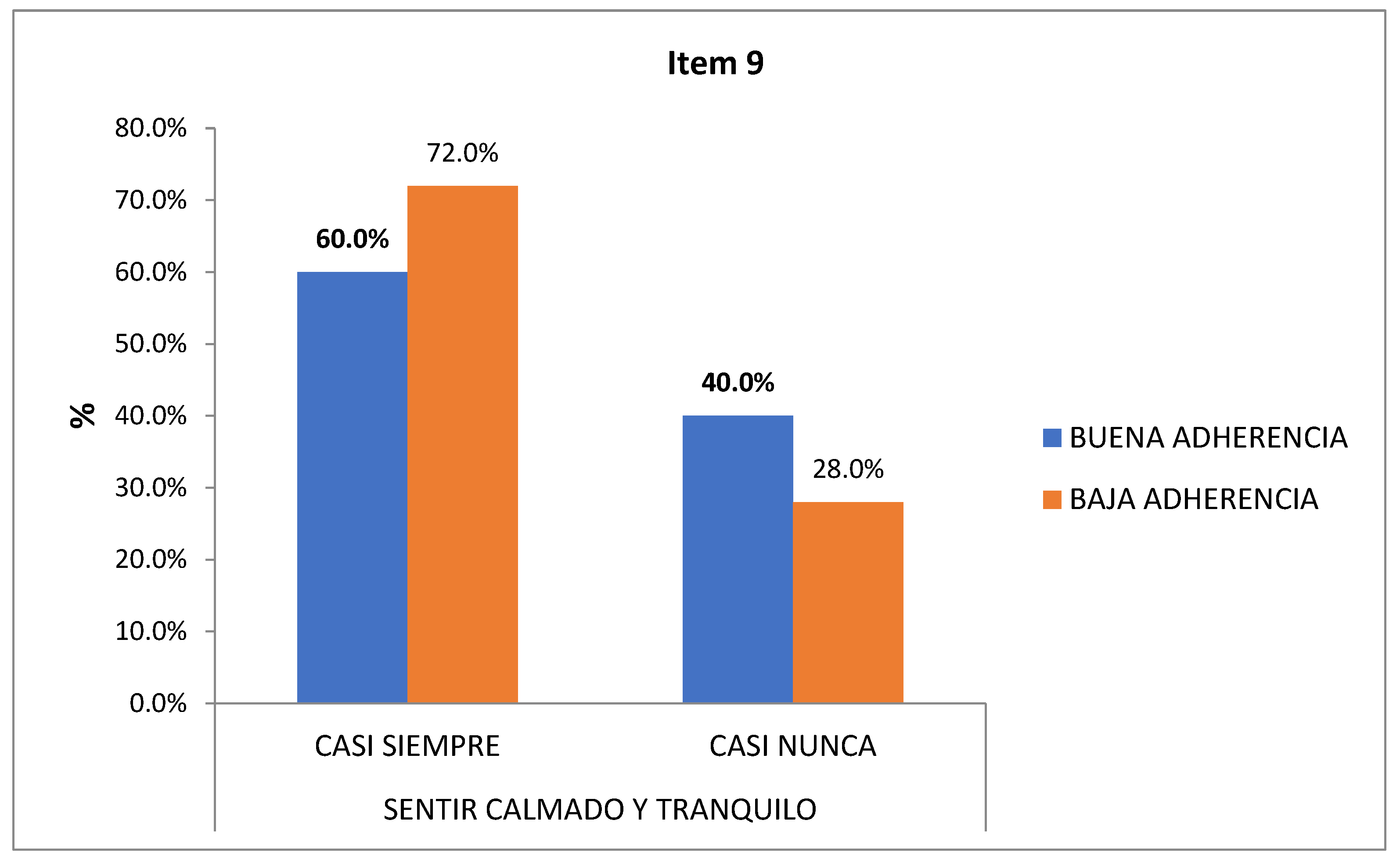

9th Mental health: After narrowing down to “almost always” and “almost never”, 72% with low adherence compared to 60% with good adherence, considered that in the last 4 weeks they almost always felt calm and calm (

Figure 12).

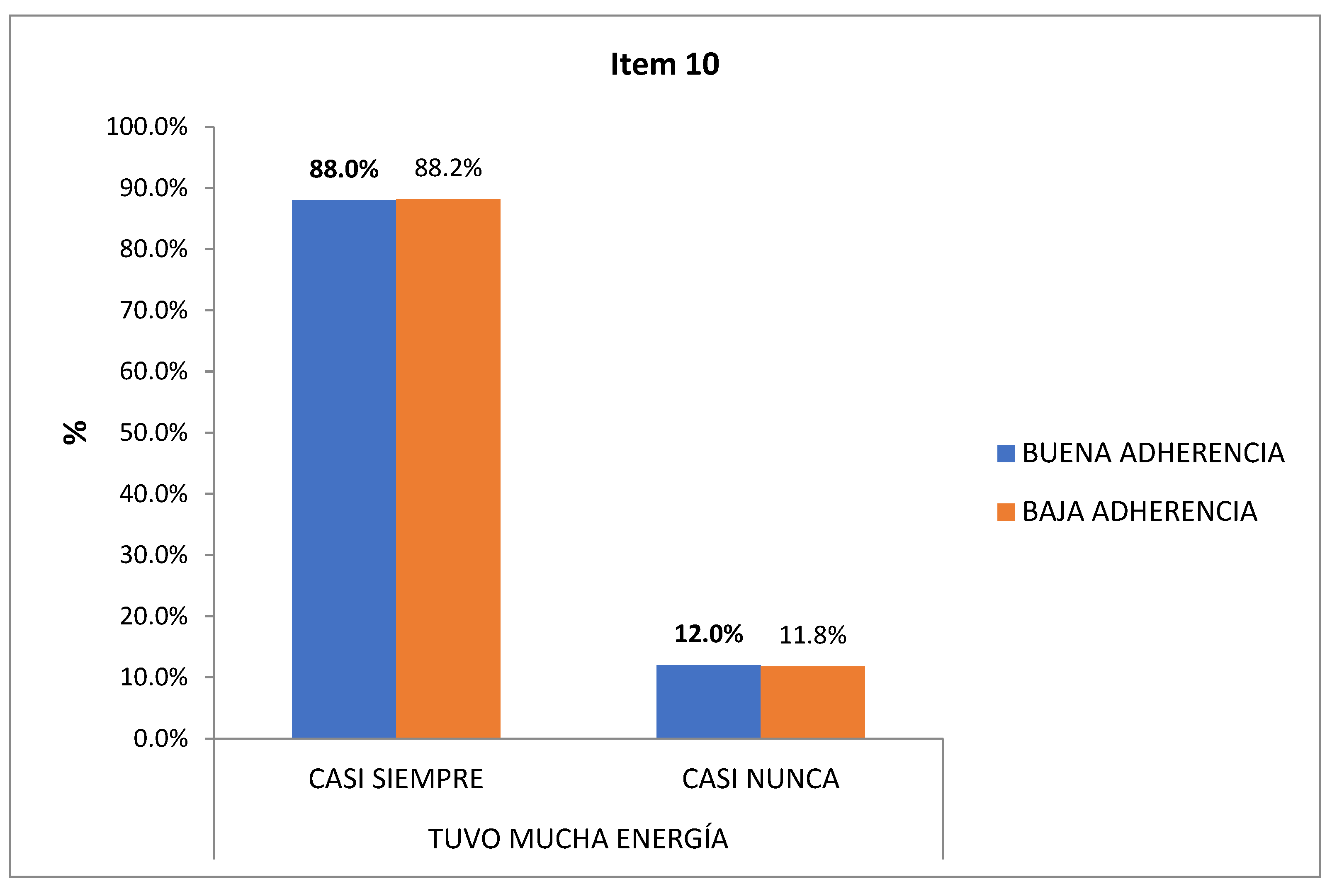

10th Vitality: 88.2% with low adherence compared to 88% with good adherence almost always had a lot of energy (

Figure 13).

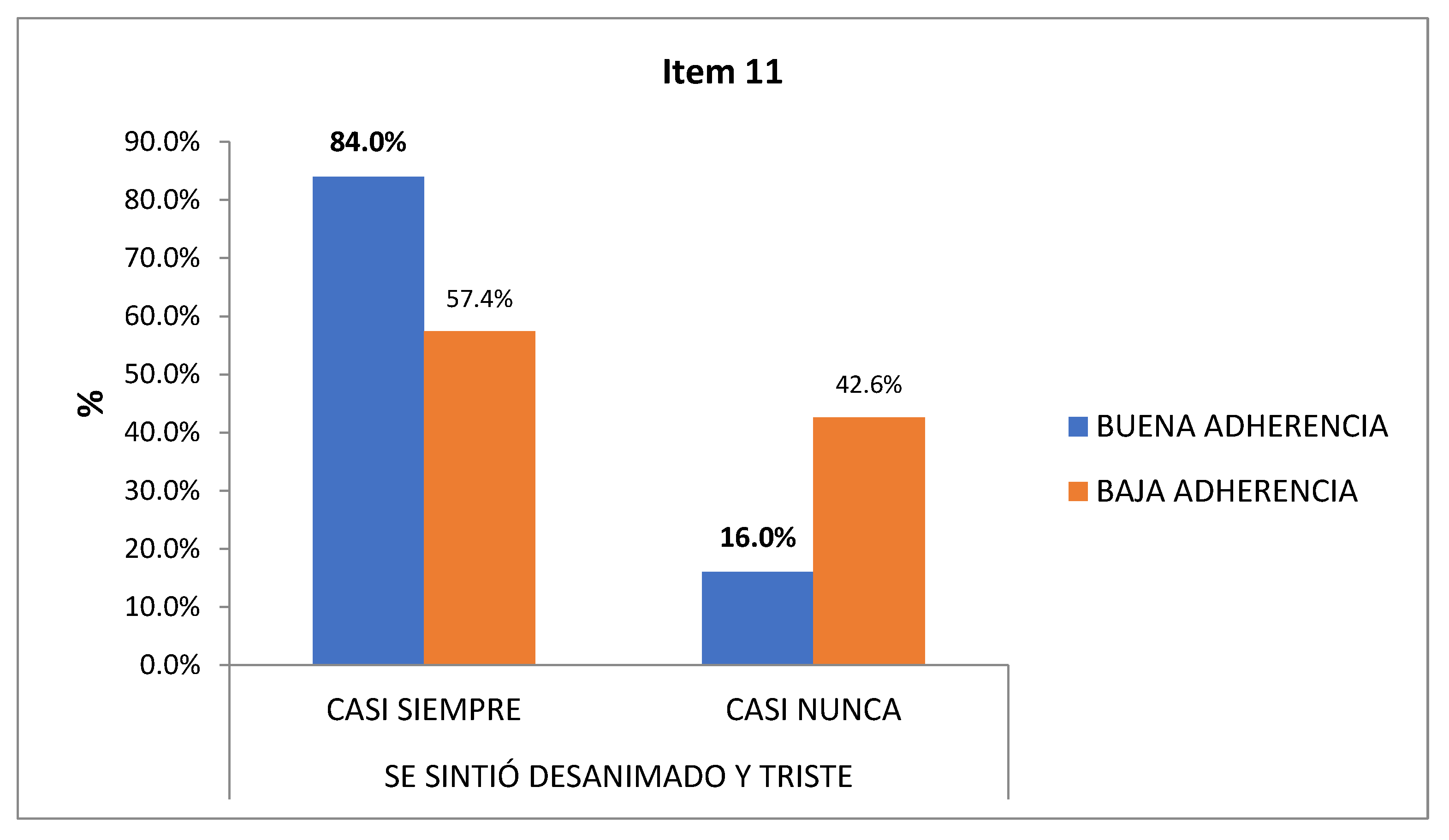

11th Mental Health I: After delimiting “almost always” and “almost never”, 84% of the patients with good adherence compared to 57% of those with low adherence, considered that in the last 4 weeks they felt discouraged and sad almost always (

Figure 14).

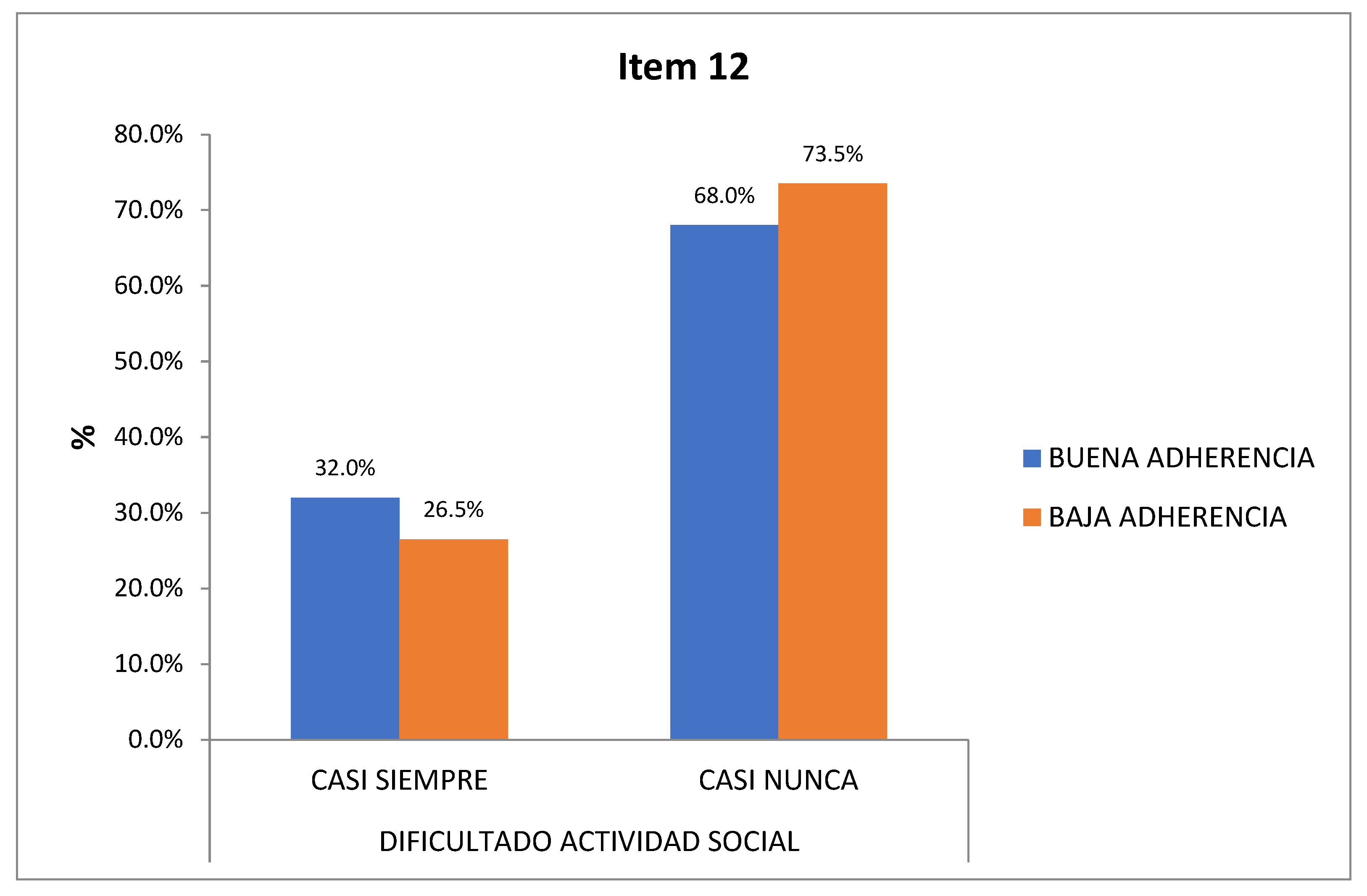

12th Social function: After delimiting “almost always” and “almost never”, in the last 4 weeks, only 26% of those with low adherence and 32% of those with good health had affected their social activity (

Figure 15).

3.2.2. Degrees of obesity:

No significant results are obtained, but it is worth noting:

1st General health: Despite the fact that 42% of the obese consider themselves to be in good health, 40% consider that they are in regular health; as well as 4.5% of overweight patients and 2% of normal weight patients.

2nd Physical function l: Half of the obese (53%) responded to a greater physical limitation than the overweight (5%) and or normal weight 2%.

3rd Physical function II: In the same way, most of the obese (60%) consider that they are somewhat limited to climb several floors.

4th Physical Role I: 52% of the patients, 47% being obese, did less than they would have wanted to do limited by their physical health.

5th Physical Role II: The same percentage (52%, 47% of obese) did not consider having to stop doing any task at work.

6th Emotional Role I: 61% of the total (56% of obese) do not consider having emotional problems to do less than expected.

7th Emotional Role II: 56% of the total (50% of obese) did not have to stop doing tasks at work due to emotional problems.

8th Body pain: 34% of the obese had regular pain that made their usual work difficult. However, the majority of overweight patients (3.2%) considered they had no pain.

9th Mental health: 36% of the obese compared to 2% of overweight considered that they almost always felt calm and calm.

10th Vitality: The 60% of overweight people often had a lot of energy, unlike the 45% of the obese who only sometimes.

11th Mental Health I: 44% of the obese considered that in the last 4 weeks they felt discouraged and sad only sometimes.

12th Social function: 55% of the obese considered that their health had rarely affected their social activity and 15% of the total (14% obese, 1% overweight) never.

4. Discussion

QoL is a subject that is currently gaining much interest in health, especially in chronic pathologies12. There is currently little evidence available about the real impact of DM on HRQoL, since most of the research on HRQoL in DM has been directed more to the study of differences between subgroups according to possible determinants of health13, than to the study of its impact.

The source of information for most of the studies that assess the impact of DM on HRQoL comes from health surveys conducted in the general population14. Despite the fact that there are 22 specific questionnaires to assess HRQoL in DM that report on the patient's perception of how diabetes affects their well-being and health in their physical and mental areas, only the 5 questionnaires in the Spanish version (ADDQoL-19, DAS -3sp, DQOL, DTSQ and MIAT-D) show great variability in measurements, standards and scales, which makes it difficult to compare results13.

According to the different studies on DM, the dimensions that are most important are those that have to do with physical and psychosocial function and disease control13-15.

Priority has been given to the use of a generic instrument, such as the SF-12v2, a subjective measure that is easy to apply individually, which has made it possible to obtain not only a physical profile, but also a mental and social one, in relation to HRQoL12.

In this study, we found a non-significant association between good/low adherence to MedD and the dimensions of the SF-V12. Manifesting that patients with poorly controlled DM2 but with good adherence have a higher response rate of good conception of their health (52%), unlike those with low adherence who present a poor conception of health (51.5%). At the same time, most of the patients with low adherence present functional limitation, considering a large part (47%) that they are limited when climbing floors, for which 54% did less than they would have wanted to do but without having emotional problems that prevented them from doing so. limited (45%), considering themselves to have less bodily pain (19%) and more calm and calm (72%) compared to those with good adherence to MedDM (8% and 60%). Regarding the perception of vitality, it was very similar in both groups (88%), but the majority of the group with good adherence (84%) felt discouraged and sad compared to the group with low adherence (58%), without affectation. of the social function, being higher in the latter (74% and 68%). That is, the patients with low adherence to the MedD presented greater affectation in the physical sphere (limitation, bodily pain, vitality) and less in the mental sphere (they consider themselves calm and calm, without feeling discouraged or sad), affected equally to the social function (little limitation).

Few studies have examined the association of a comprehensive dietary pattern such as MedDM with HRQoL. Only one cross-sectional study (n = 8195) carried out in a Spanish population demonstrated that adherence to the MedD was associated with a higher score for self-perception of health (Muñoz et al., 2009)16. In the SUN17 Project, a cohort of university graduates to establish the association between diet and chronic diseases that included 11,015 participants, a significant direct association was reported between greater baseline adherence to MedDM and better dimensions of physical and mental health measured with the SF. -36, after 4 years18; showing the domains of physical role, bodily pain, general health and vitality significantly better with greater adherence to the MedD. On the other hand, Henríquez-Sánchez et al19 observed a positive relationship between adherence to MedDM and four HRQoL physical health categories in younger subjects in their longitudinal evaluation of the SUN cohort, although there were no significant associations in the health dimensions. In addition, Pérez-Tasigchana et al20 found better results in physical categories with the SF-12 questionnaire when high adherence to MedD was reported in the ENRICA21 cohort. In the Moli-sani Project (2010)22, a population-based cohort study in Italy has found that MedDM is associated with better baseline HRQoL. In the PREDIMED-Plus23 study, greater adherence to MedDM was independently associated with significantly better scores in the 8 HRQoL dimensions (SF-36). Adjusted differences of ≥ 3 points were observed between the highest and lowest dietary adherence groups on the MedDM for vitality, emotional role, and mental health, and ≥ 2 points for the other dimensions.

When initially comparing the 12 items of the SF-v212 with the BMI degrees (normal weight, overweight, obesity), no significant results were obtained, but it should be noted that almost half of the obese (42%) consider themselves to be in good health, but however, they had physical limitations to make moderate efforts (53%), doing less than they would have wanted to do, but without emotional problems (56%) that limited them. 34% of the obese had regular pain that made it difficult for them to do their usual work. However, most of the overweight patients (3.2%) appreciated having no pain. Despite considering being almost always calm and only 44% of the obese judging themselves discouraged and sad, with little affectation of their social function; Less than half considered themselves to be vital, unlike those who were overweight, who did consider it mostly.

The results obtained are similar to those found in the systematic review carried out by Kolotkin et al24, where the included articles verified that the HRQoL scores in the field of the physical component were lower when the BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, a relationship that it becomes even more apparent in higher BMI categories. The dimension with the lowest score within the physical component field was also the physical role. Regarding the mental field, there was a worsening of HRQoL in women with higher BMI, specifically in the dimensions of vitality and social function, but this did not occur in men. One reason could be the effect obesity stigma has on women compared to men.

5. Conclusions

People with DM2 and poor metabolic control have a poor perception of health, especially in the physical sphere. Low adherence to the MedD is related to a greater affectation in the physical dimension (“general health”, “physical function”, “physical role” and “body pain”). Despite this, they have presented less affectation in the mental dimension ("emotional role" or "vitality"), without affectation in the "social function". In turn, patients with higher BMI (obesity) have a greater impact on the physical dimension and patients with lower BMI (overweight or normal weight) have better scores on mental dimensions, considering themselves to be better at a mental and physical level.

Due to the fact that the efficacy of a MedDM pattern on HRQoL has been demonstrated, more attention should be devoted to dietary interventions from a multidisciplinary approach from PC, to promote the Mediterranean lifestyle and improve unhealthy eating habits acquired in recent years. And that are having a negative impact not only on our physical and mental health but also on our perception of it.

References

- Navarrete EV, Fernández-Villa T, Gamero A, Nava-González EJ, AlmendraPegueros R, Benítez N, et al. Balance del año 2020 y nuevos propósitos de 2021 para abordar los objetivos propuestos en el Plan Estratégico 2020-2022. Rev Esp Nutr Hum Diet. 2021, 25, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Molina-Montes, E.; Verardo, V.; Artacho, R.; García-Villanova, B.; Guerra-Hernández, E.J.; Ruíz-López, M.D. Changes in Dietary Behaviours during the COVID-19 Outbreak Confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guénette, L.; Breton, M.-C.; Guillaumie, L.; Lauzier, S.; Grégoire, J.-P.; Moisan, J. Psychosocial factors associated with adherence to non-insulin antidiabetes treatments. J. Diabetes its Complicat. 2015, 30, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHOQOL Group. Study protocol for the World Health Organization project to develop a Quality of Life assessment instrument (WHOQOL). Qual Life Res. 1993, 2, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso J, Regidor E, Barrio G, Prieto L, Rodríguez C y de la Fuente L. Valores poblacionales de referencia de la versión española del Cuestionario de Salud SF-36. Med Clin Barc 1998, 111, 410–416. [Google Scholar]

- Valera G, Requejo AM, Ortega R, Zamora S, Salas J, Cabrerizo L, et al. Dieta Mediterránea en el siglo XXI: posibilidades y oportunidades. En: Libro blanco de la alimentación en España. Sociedad Española de Nutrición. Madrid, 2013; 221-229.

- Martínez-González MÁ, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J, Ros E, Covas MI, Fiol M, et al. Cohortprofile: design and methods of the PREDIMED study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 377–385.

- Salas-Salvadó J, Bulló M, Babio N, Martínez-González MA, Ibarrola- Jurado N, Basora J, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the Mediterranean diet: results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes.

- Sofi, F.; Cesari, F.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ 2008, 337, a1344–a1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F.; Macchi, C.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Mediterranean diet and health. BioFactors 2013, 39, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, H.; Fitó, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Ros, E.; Salaverría, I.; Fiol, M.; et al. A Short Screener Is Valid for Assessing Mediterranean Diet Adherence among Older Spanish Men and Women. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, A.M. Impact of Improved Glycemic Control on Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetes. Endocr. Pr. 2004, 10, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakroub, D.; Sakr, F.; Dabbous, M.; Dia, N.; Hammoud, J.; Rida, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Fahs, H.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S.; et al. The Socio-Demographic and Lifestyle Characteristics Associated with Quality of Life Among Diabetic Patients in Lebanon: A Crosssectional Study. Pharm. Pr. (Internet) 2023, 21, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata M, Roset M, Badía X, Antoñanzas F, Ragel J. Impacto de la diabetes mellitus en la calidad de vida de los pacientes tratados en las consultas de atención primaria en España. Aten Primaria 2003, 31, 493–499. [CrossRef]

- Monteagudo Piqueras O, Hernando Arizaleta L, Palomar Rodríguez JA. Population based norms of the Spanish version of the .

- SF-12V2 for Murcia (Spain). Gac Sanit 2011, 25, 50–61.

- León-Muñoz, L.M.; Guallar-Castillón, P.; Graciani, A.; López-García, E.; Mesas, A.E.; Aguilera, M.T.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Pattern Has Declined in Spanish Adults3. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1843–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M.; Martínez-González, M.A.; De Irala-Estevez, J. for the SUN Group (Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra). Gender, age, socio-demographic and lifestyle factors associated with major dietary patterns in the Spanish Project SUN (Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra). Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguí-Gómez M, de la Fuente C, Vázquez Z, de Irala J, Martínez González MA. Cohort profile: the ‘Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra’ (SUN) study. Int J Epidemiol. 2006, 35, 1417–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P.H.; Ruano, C.; DE Irala, J.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Sánchez-Villegas, A. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and quality of life in the SUN Project. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Tasigchana, R.F.; León-Muñoz, L.M.; López-García, E.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Guallar-Castillón, P. Mediterranean Diet and Health-Related Quality of Life in Two Cohorts of Community-Dwelling Older Adults. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0151596–e0151596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guallar-Castillón P, Pérez RF, García EL, León-Muñoz LM, Aguilera MT, Graciani A, et al. Magnitud y manejo del síndrome metabólico en España en 2008-2010: Estudio ENRICA. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2014, 67, 367–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Bonanni, A.; Costanzo, S.; De Lucia, F.; Pounis, G.; Zito, F.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with a better health-related quality of life: a possible role of high dietary antioxidant content. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galilea-Zabalza, I.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Toledo, E.; Ortega-Azorín, C.; Díez-Espino, J.; Vázquez-Ruiz, Z.; Zomeño, M.D.; Vioque, J.; Martínez, J.A.; et al. Mediterranean diet and quality of life: Baseline cross-sectional analysis of the PREDIMED-PLUS trial. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0198974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolotkin L, Anderse JR. A systematic review of reviews: exploring therelationship between obesity, weight loss andhealth-related quality of life. ClinicalObesity 2017, 7, 273–289. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).