Submitted:

18 May 2023

Posted:

19 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A novel synthesis route for transparent coatings preparation based on selection (e.g., different crosslinking agents), curing conditions (e.g., exposure time) with high conversion rates over extended UV-LED exposure time range.

- A selection of fluorinated resins-based transparent coatings deliverables under different curing exposure times.

- Data processing and analysis on the comprehensive database containing viscoelastic and optical properties (i.e., refractive indices, thermo-optical coefficients, and optical losses).

2. Materials and Methods

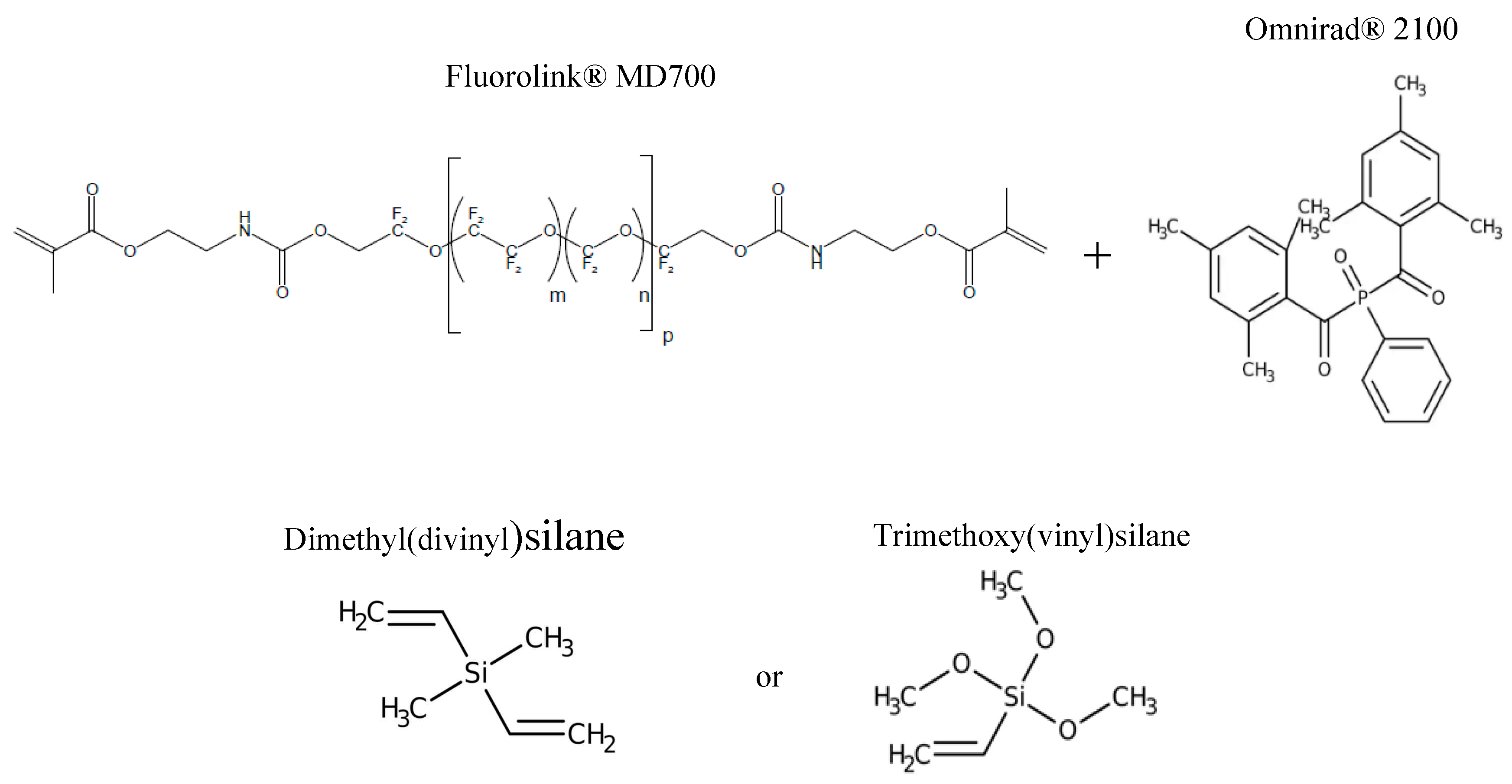

2.1. Materials

2.2. Coating preparation and UV-LED assisted curing process

2.3. Curing behaviour and characterization

2.4. Viscoelastic properties by means of Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

2.5. Optical properties measurements

2.5.1. Refractive index (n)

2.5.2. Thermo-optic coefficients (TOC)

2.5.3. Optical loss

3. Results and Discussions

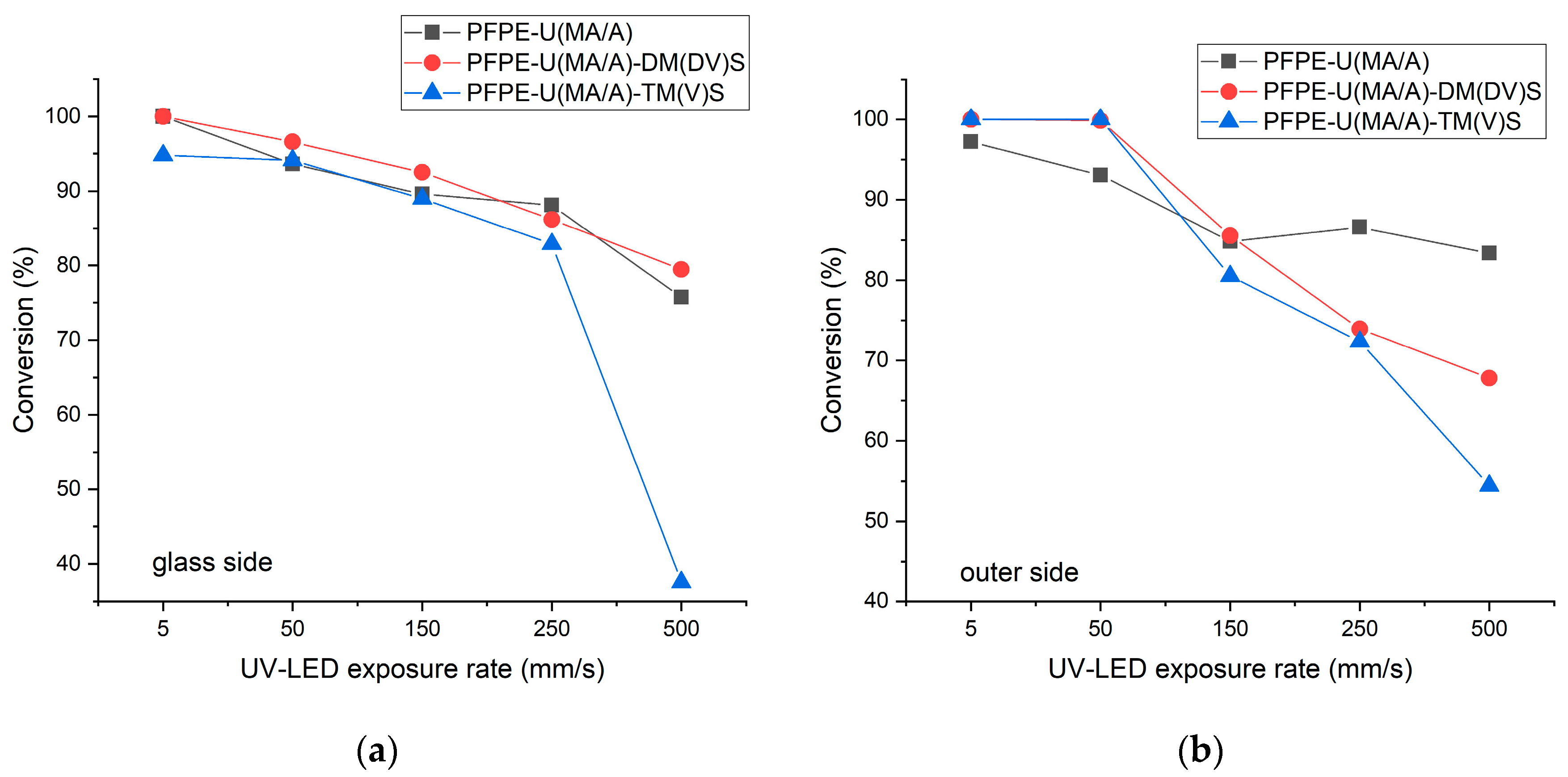

3.1. Structural characterization of UV-LED cured coatings

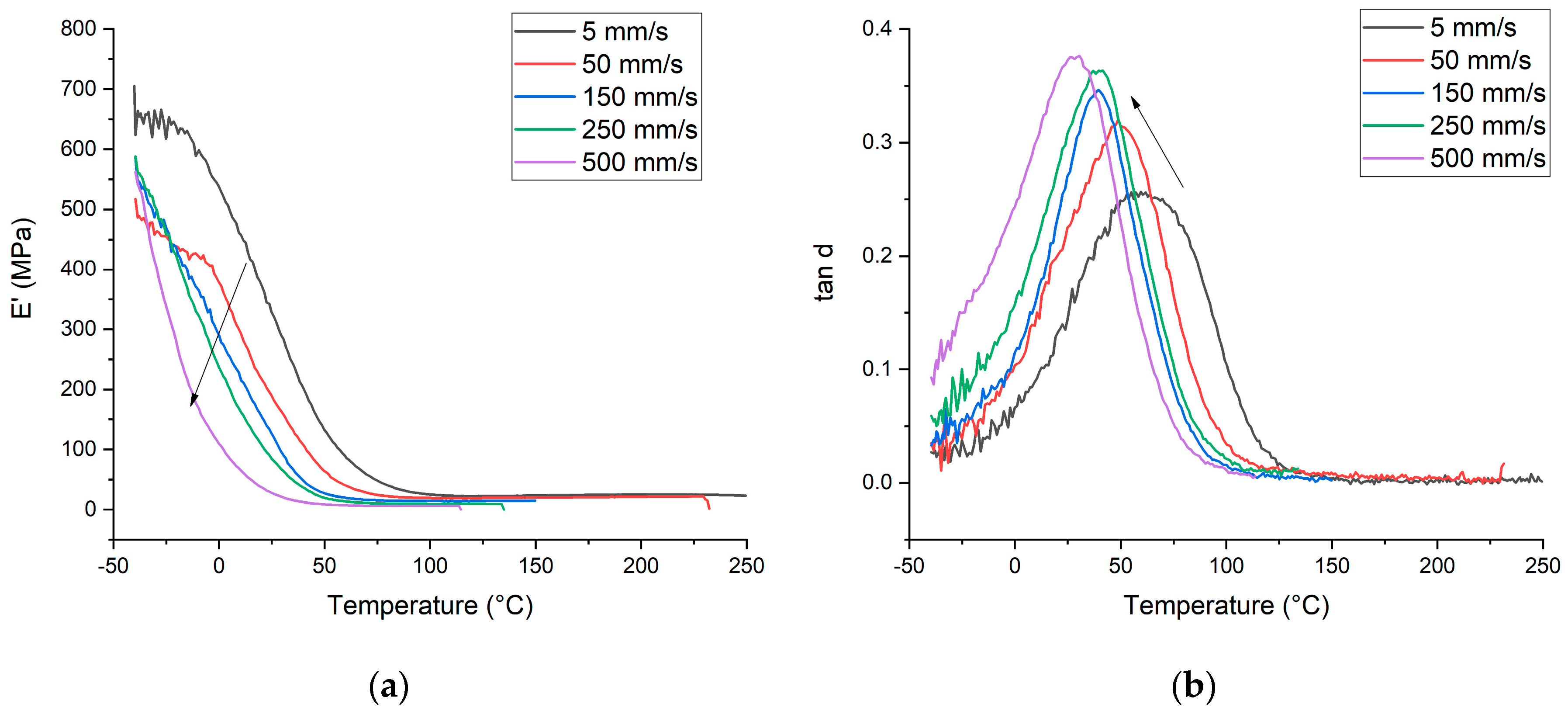

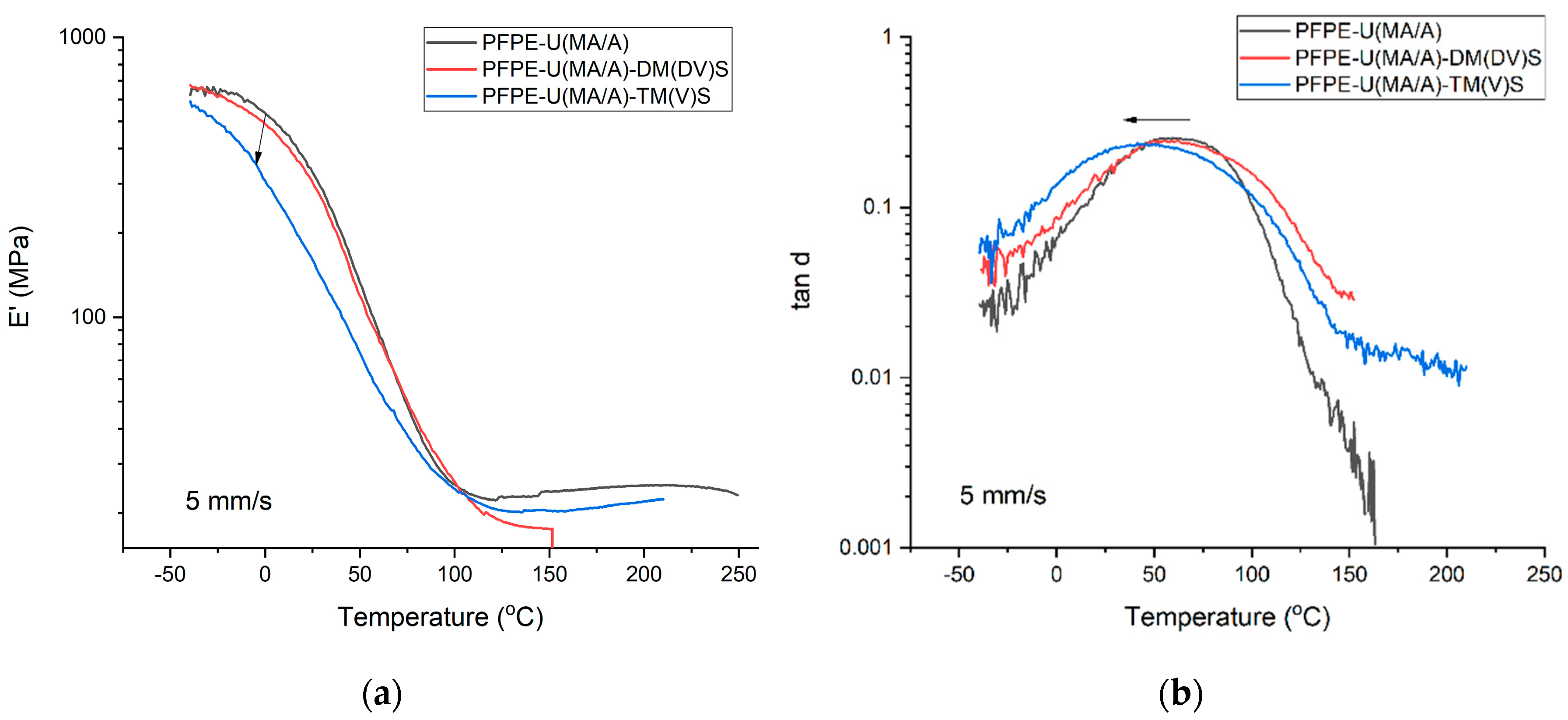

3.2. DMA properties of UV-LED cured coatings

3.3. Optical properties of UV-LED cured coatings

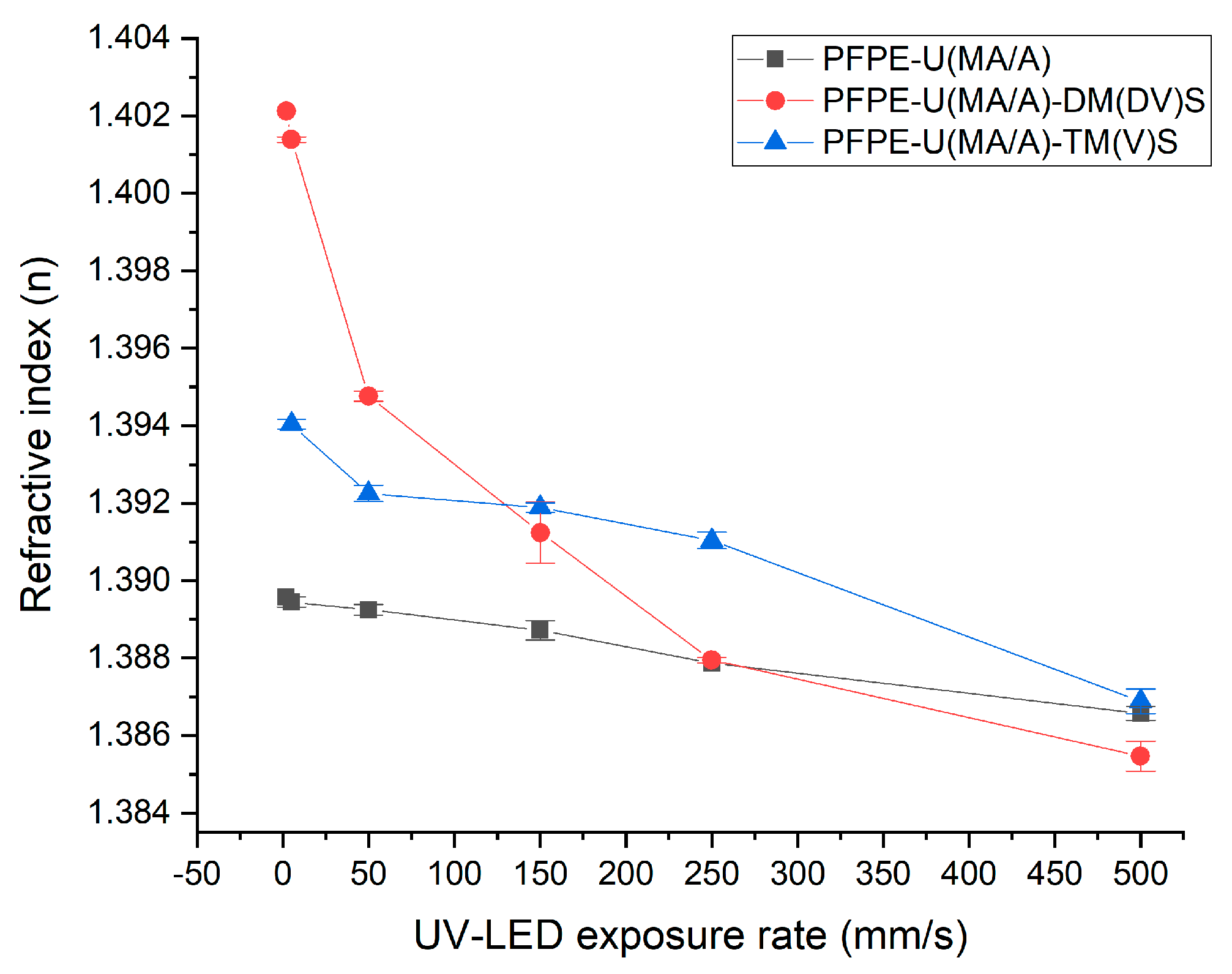

3.3.1. Refractive index (n)

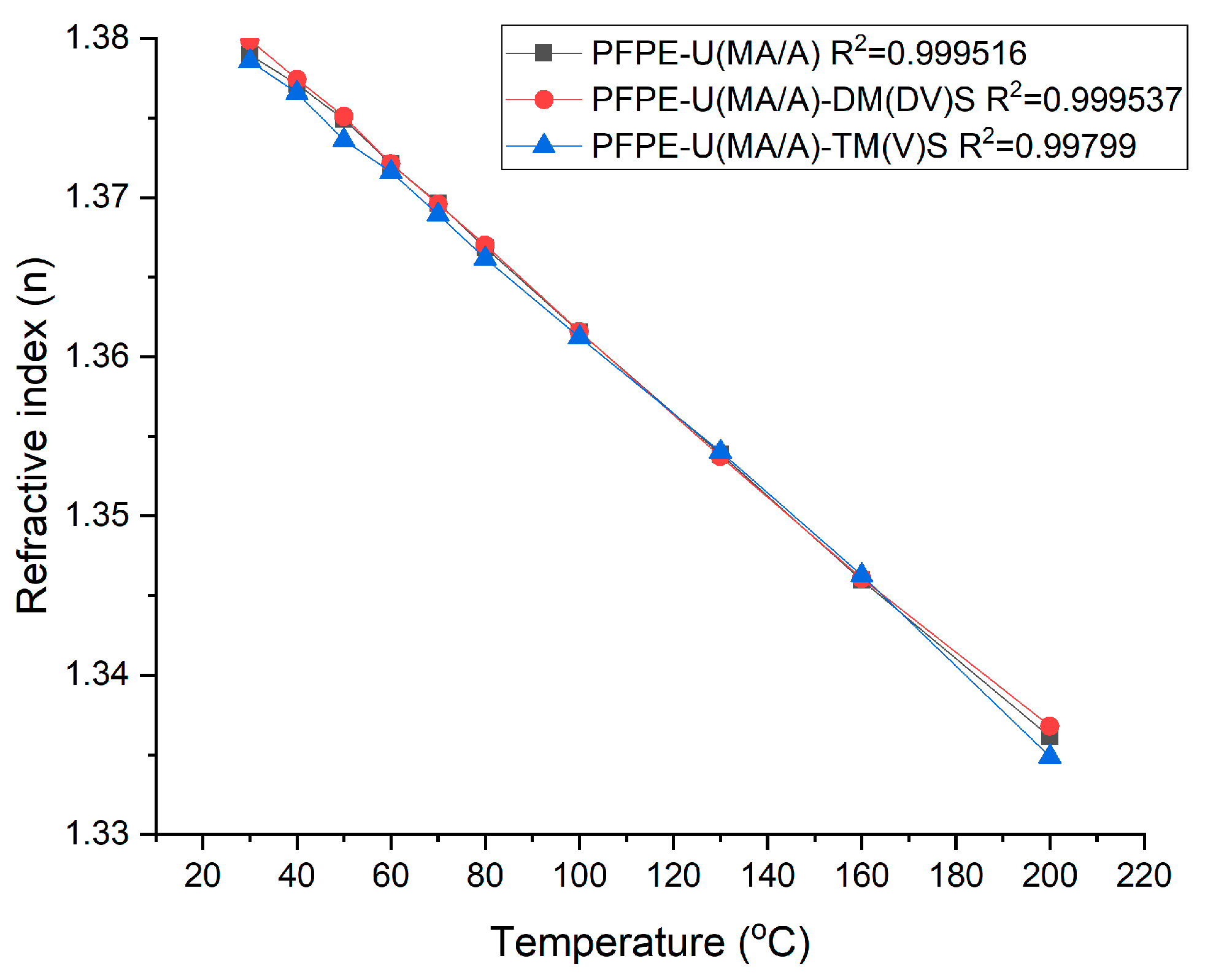

3.3.2. Thermo-optic coefficients (TOC)

3.3.3. Optical loss

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Figoli, A., et al., Innovative hydrophobic coating of perfluoropolyether (PFPE) on commercial hydrophilic membranes for DCMD application. Journal of Membrane Science, 2017. 522: p. 192-201. [CrossRef]

- Baik, J.-H., et al., Nonflammable and thermally stable gel polymer electrolytes based on crosslinked perfluoropolyether (PFPE) network for lithium battery applications. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 2018. 64: p. 453-460. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., et al., Synthesis of fluorinated polyacrylic acrylate oligomer for the UV-curable coatings. Journal of Coatings Technology and Research, 2019. 16(3): p. 681-688. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.-D. and H.-J. Kim, UV-curable low surface energy fluorinated polycarbonate-based polyurethane dispersion. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2011. 362(2): p. 274-284. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., Low-loss polymeric materials for passive waveguide components in fiber optical telecommunication. Asia-Pacific Optical and Wireless Communications Conference and Exhibit. Vol. 4580. 2001: SPIE.

- Jang, J.Y. and J.Y. Do, Synthesis and evaluation of thermoplastic polyurethanes as thermo-optic waveguide materials. Polymer Journal, 2014. 46(6): p. 349-354. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., et al., Thermo-optic coefficients of polymers for optical waveguide applications. Polymer, 2006. 47(14): p. 4893-4896. [CrossRef]

- Jančovičová, V., et al., Influence of UV-curing conditions on polymerization kinetics and gloss of urethane acrylate coatings. Progress in Organic Coatings, 2013. 76(2): p. 432-438. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.H., et al., Preparation and Properties of UV-curable fluorinated polyurethane acrylates containing crosslinkable vinyl methacrylate for antifouling coatings. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2015. 132. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., et al., Preparation and properties of crosslinked network coatings based on perfluoropolyether/poly(dimethyl siloxane)/acrylic polyols for marine fouling–release applications. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2015. 132(17).

- June, Y.-G., et al., Influence of functional group content in hydroxyl-functionalized urethane methacrylate oligomers on the crosslinking features of clearcoats. Journal of Coatings Technology and Research, 2021. 18(1): p. 229-237. [CrossRef]

- Sung, S., et al., Thermally reversible polymer networks for scratch resistance and scratch healing in automotive clear coats. Progress in Organic Coatings, 2019. 127: p. 37-44. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., et al., Polymers for high performance Li-S batteries: Material selection and structure design. Progress in Polymer Science, 2019. 89: p. 19-60. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., et al., Functional polymers for lithium metal batteries. Progress in Polymer Science, 2021. 122: p. 101453. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H., et al., UV-curable low-surface-energy fluorinated poly(urethane-acrylate)s for biomedical applications. European Polymer Journal, 2008. 44(9): p. 2927-2937. [CrossRef]

- Vitale, A., R. Bongiovanni, and B. Ameduri, Fluorinated Oligomers and Polymers in Photopolymerization. Chemical Reviews, 2015. 115(16): p. 8835-8866. [CrossRef]

- Kotz, F., et al., Highly Fluorinated Methacrylates for Optical 3D Printing of Microfluidic Devices. Micromachines, 2018. 9(3): p. 115. [CrossRef]

- McKeen, L.W., 19 - Fluorinated Coatings; Technology, History, and Applications, in Introduction to Fluoropolymers (Second Edition), S. Ebnesajjad, Editor. 2021, William Andrew Publishing: Oxford. p. 339-367.

- Ursino, C., et al., Development of a novel perfluoropolyether (PFPE) hydrophobic/hydrophilic coated membranes for water treatment. Journal of Membrane Science, 2019. 581: p. 58-71. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J., et al., Spectroscopic ellipsometric study datasets of the fluorinated polymers: Bifunctional urethane methacrylate perfluoropolyether (PFPE) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF). Data in Brief, 2021. 39: p. 107461. [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, R., et al., New perfluoropolyether urethane methacrylates as surface modifiers: Effect of molecular weight and end group structure. Reactive and Functional Polymers, 2008. 68(1): p. 189-200. [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, R., et al., Perfluoropolyether polymers by UV curing: design, synthesis and characterization. Polymer International, 2012. 61(1): p. 65-73. [CrossRef]

- Dalle Vacche, S., et al., Glass lap joints with UV-cured adhesives: Use of a perfluoropolyether methacrylic resin in the presence of an acrylic silane coupling agent. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 2019. 92: p. 16-22. [CrossRef]

- Goralczyk, A., et al., On-Chip Chemical Synthesis Using One-Step 3D Printed Polyperfluoropolyether. Chem Ing Tech, 2022. 94(7): p. 975-982. [CrossRef]

- Masson, F., et al., UV-curable formulations for UV-transparent optical fiber coatings: I. Acrylic resins. Progress in Organic Coatings, 2004. 49(1): p. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Gleißner, U., et al., The influence of photo initiators on refractive index and glass transition temperature of optically and rheologically adjusted acrylate based polymers. Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 2016. 27(10): p. 1294-1300. [CrossRef]

- Javadi, A., et al., Cure-on-command technology: A review of the current state of the art. Progress in Organic Coatings, 2016. 100: p. 2-31. [CrossRef]

- Kredel, J., et al., Cross-Linking Strategies for Fluorine-Containing Polymer Coatings for Durable Resistant Water- and Oil-Repellency. Polymers, 2021. 13(5): p. 723. [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, S.K., et al., UV-LED as a New Emerging Tool for Curable Polyurethane Acrylate Hydrophobic Coating. Polymers, 2021. 13(4): p. 487. [CrossRef]

- Dall Agnol, L., et al., UV-curable waterborne polyurethane coatings: A state-of-the-art and recent advances review. Progress in Organic Coatings, 2021. 154: p. 106156. [CrossRef]

- Startek, K., et al., Influence of fluoroalkyl chains on structural, morphological, and optical properties of silica-based coatings on flexible substrate. Optical Materials, 2021. 121: p. 111524. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H., et al., Thermal and optical properties of hyperbranched fluorinated polyimide/mesoporous SiO2 nanocomposites exhibiting high transparency and reduced thermo-optical coefficients. Polymer, 2014. 55(12): p. 2848-2855. [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, M., et al., Experimental measurement of temperature-dependent sellmeier coefficients and thermo-optic coefficients of polymers in terahertz spectral range. Optical Materials, 2019. 91: p. 126-129. [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, C., et al., Chapter 9 - Fluorinated thermosetting resins for photonic applications, in Fascinating Fluoropolymers and Their Applications, B. Ameduri and S. Fomin, Editors. 2020, Elsevier. p. 269-335.

- Nourshargh, N., et al. Simple technique for measuring attenuation of integrated optical waveguides. Electronics Letters, 1985. 21, 818-820. [CrossRef]

- Hill, L.W., Calculation of crosslink density in short chain networks. Progress in Organic Coatings, 1997. 31(3): p. 235-243. [CrossRef]

- Pitois, C., et al., Fluorinated dendritic polymers and dendrimers for waveguide applications. Optical Materials, 2003. 21(1): p. 499-506. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.Y. and E. Kim, Optical loss of photochromic polymer films. Integrated Optoelectronics Devices. Vol. 4991. 2003: SPIE.

- Oh, M.-C., et al., Integrated Photonic Devices Incorporating Low-Loss Fluorinated Polymer Materials. Polymers, 2011. 3(3): p. 975-997. [CrossRef]

| Sample | UV-LED exposure rate | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mm/s | 50 mm/s | 150 mm/s | 250 mm/s | 500 mm/s | |||||||||||||||||||

| Tg (°C) | tanδmax | E’ (MPa) | ν* (mol/m3) | Tg (°C) | tanδmax | E’ (MPa) | ν (mol/m3) | Tg (°C) | tanδmax | E’ (MPa) | ν(mol/m3) | Tg (°C) | tanδmax | E’ (MPa) | ν (mol/m3) | Tg (°C) | tanδmax | E’ (MPa) | ν (mol/m3) | ||||

| PFPE-U(MA/A) | 59.50 | 0.2568 | 328.92 | 2714 | 48.80 | 0.3207 | 190.1 | 2110 | 41.50 | 0.3462 | 126.91 | 1573 | 37.18 | 0.36304 | 85.242 | 1020 | 30.58 | 0.37642 | 28.03 | 691 | |||

| PFPE-U(MA/A)-DM(DV)S | 57.20 | 0.2447 | 327.72 | 2638 | 54.10 | 0.2660 | 204.7 | 1690 | 39.60 | 0.2964 | 82.714 | 1123 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| PFPE-U(MA/A)-TM(V)S | 41.50 | 0.2386 | 170.58 | 2539 | 44.20 | 0.2566 | 122.87 | 1670 | 34.50 | 0.3098 | 63.62 | 919 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Exposure rate (mm/s) | nTE | dn/dT (∙10-4) | β* (K1)(∙10-4) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFPE-U(MA/A) | PFPE-U(MA/A)- DM(DV)S | PFPE-U(MA/A)- TM(V)S | PFPE-U(MA/A) | PFPE-U(MA/A)- DM(DV)S | PFPE-U(MA/A)- TM(V)S | PFPE-U(MA/A) | PFPE-U(MA/A)- DM(DV)S | PFPE-U(MA/A)- TM(V)S | |

| 5 | 1.38945 | 1.40139 | 1.39404 | -2.57 | -2.57 | -2.55 | 5.858 | 5.656 | 5.734 |

| 50 | 1.38925 | 1.39477 | 1.39225 | 5.861 | 5.766 | 5.764 | |||

| 150 | 1.38872 | 1.39124 | 1.39189 | 5.870 | 5.827 | 5.770 | |||

| 200 | 1.38787 | 1.38795 | 1.39104 | 5.885 | 5.884 | 5.785 | |||

| 250 | 1.38657 | 1.38547 | 1.38689 | 5.908 | 5.928 | 5.857 | |||

| Specimen | Optical loss (dB/cm) | |

|---|---|---|

| @633 nm | @1547 nm | |

| PFPE-U(MA/A) | 1.4 | 1.9 |

| PFPE-U(MA/A)-DM(DV)S | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| PFPE-U(MA/A)-TM(V)S | 1.3 | 2.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).