1. Introduction

Many studies have analyzed lead user innovation, yet the intricacies of partnership and outcomes remain largely uncharted. Innovation in recent years has attracted great debates on how, where, when, who, and what has been innovated. As a concept, innovation is the introduction of changes in the formulation of products, services, production processes, markets, resources, materials, and organizational forms [

30,

37]. Innovation interests researchers and practitioners in various disciplines and thus have been defined by scholars from the perspective of different disciplines [

5]. Two groups of scholars, Tidd and Bessant (2013); and Tidd and Hull (2010), define innovation as the process of turning ideas into reality and capturing value from them.

Scholars have categorized innovators into lead and non-lead users [

2,

39]. Lead users are users of a product or service that they develop, that will gain market acceptance and fulfil a future market need in a beneficial way [

10,

39]. Non-lead users, on the other hand, have been identified as innovators who innovate as either part of a team or for the market but do not use the product or service; they innovate [

3]. In the recent past, scholars have investigated the relationships between lead users and non-lead users [

13,

20].

Importance of Partnerships

A lead user innovator may face several risks without a lead user partnership. Some of the most common issues include a limited understanding of other customers’ needs and preferences. This is because, without input from other lead users, an innovator or team may struggle to identify and address its target market’s specific needs and desires. Second, difficulty staying ahead of the competition. This may be attributed to a lack of close relationships with lead users. Therefore, an individual may be less able to identify and capitalize on new opportunities for innovation and growth. Third, there can be costly delays in product development due to limited input and longer problem-resolution lead times. Lastly, a lack of customer loyalty since the value chain lead user partners may not feel engaged, and therefore, customer loyalty is affected [

4,

19,

38].

Innovators face many challenges in the processes they undertake. First, the product or service desirability of innovation’s outcome might cater to the taste of only a few clients. This might affect the diffusion of innovation and make it a very slow process or none at all [

16,

33]. Second, the organisation may experience inertia and be stuck in its way of doing things. This is typically attributed to standard operating procedures (SOPs) that govern all other aspects of the organisation and its relationship with users. Inertia emerges because the organisation cannot develop the resources and capabilities necessary to maintain the innovation process after the first idea phase [

34]. Third, many companies state that lead user innovation can be wasteful due to the time and resources required for testing and developing the collaborative effort [

11,

25]. The costs associated with lead user innovation are perceived to be higher than those of traditional innovation channels [

20,

21,

22]. Fourth, users may approach problems based on their natural orientation and training. The lead users may have inclinations toward exercising their core skills or experience within their own field. This methodology may prolong the problematic situation and hinder the progress of the innovation [

6,

23]. Finally, the regulatory landscape poses various challenges for innovators due to a lack of clarity on the rules of engagement [

1]. When lead users overcome various challenges and enjoy the benefits of innovation, they also achieve various outcomes.,

There is a gap in knowledge on innovation partnerships due to the limited research and understanding of the specific factors that lead to successful partnerships between lead users, teams, and firms to drive innovation. Additionally, there is a lack of consensus on the best practices for creating and managing these partnerships. This knowledge gap can make it difficult for lead users and organizations to form effective partnerships and achieve their desired outcomes.

The study’s objective was to assess the impact that partners of lead users have on lead user innovation outcomes within the financial technology sector. By achieving the objective, the study provides new insight into the relationship between the lead user and the number of partners they need for success.

The remaining sections of this paper describe the extant literature, the methodology, results, a discussion of the results, study limitations, suggestions for future research and a conclusion.

2. Theoretical Perspectives and Empirical Literature

Studies have been inconsistent and contradictory about lead user innovation, its process participants and outcomes in the service industry. Some of the studies in the service industry that have shed light and helped scholars gain a deeply rooted understanding of the phenomenon from the service industry perspective have lacked the quantification of the partners [

14,

35]. There was, therefore, a need to understand and quantify the lead user partnerships and outcomes from a service industry perspective.

Previous scholars looked at how lead users carry out their innovation and the results of the lead user innovation. For example, Brem et al. (2018) examined the processes of lead user innovation, and Herstatt and von Hippel (1992) studied the outcomes of these relationships on individual or team performance. While it has been recognized that users of products and services may sometimes innovate, little is known about what brings about partnerships and user involvement in innovations and their related configurations and outcomes [

2,

17]. Additionally, disagreements exist regarding the relationships between lead user partnerships and the lead users’ innovation outcomes [

3,

28,

35]. Innovation partnerships are seen as key drivers of economic growth and job creation based on the successes obtained [

4,

40]. On the other hand, some scholars view innovation partnerships as bureaucratic, market-driven rather than user-driven, and ad-hoc [

31]. There are scholars who have stated that lead user innovation requires partnership that is based on trust, independence and familiarity, but they did not indicate the number of partners needed for success to be achieved [

7,

32].

Therefore, new knowledge, especially about lead users focusing on the number of partnerships, is necessary to help individuals and organizations remain competitive. The review needs to be done in relation to the existing theories and practices, such as lead user theory and lead user innovation partnership theory.

2.1. Lead User Theory

Lead user theory posits that users can make additional changes to an existing product or service to suit their needs better or develop a new product or service. Franke et al. (2006) and von Hippel (2009) distinguish other users from lead users through two distinct characteristics—the ability of the lead user to be ahead of market trends (trend leadership) and having expectations of benefits from the innovation. Several scholars have discussed the importance of lead users and highlighted the benefits, such as first-mover advantages, timesaving on product development, investment opportunities in new types of products, employment opportunities and generating new ideas for strategy development [

8,

18,

26]. In recent debates, lead user proponents have considered innovators as producers, where the innovation outcome is offered to the public as a commercial product [

43]. There is, therefore, a need to understand how partnerships in the innovation process can be enhanced to allow for greater efficiency and variety of offerings by the innovators to their consumers.

2.2. Lead User Innovation Partnership Theory

One theory that considers lead-user innovation partnerships is the Lead User Innovation Partnership (LUIP) theory which is an extension of the Lead user theory by von Hippel. This theory suggests that partnerships between lead users and firms can lead to the development of new products and services that meet the needs of both groups. According to the LUIP theory, lead users and firms can form partnerships to co-create new products and services that meet the needs of lead users and have commercial potential for the firm [

41].

The theory proposes that lead-user innovation partnerships can be beneficial for both parties as lead users can provide firms with valuable insights into emerging market trends and new product opportunities, while firms can provide lead users with access to resources and capabilities that they need to innovate. The LUIP theory emphasizes the importance of effective communication, trust, and mutual understanding between the lead user and the firm for the success of the partnership [

10,

42].

This theory highlights the importance of lead users as valuable partners for firms in the innovation process, as they can provide valuable knowledge and insights that can help firms create new products and services that meet the market’s needs and generate commercial success [

4]. This paper reflects on the partners’ importance and the number of partners needed for successful innovation outcomes.

2.3. Lead User Partnership

Once the lead users have been identified based on their characteristics, various phases of innovation then take shape. Pyramiding, a term coined by scholars to identify the persons with high levels of a given attribute in a population or sample, can help make the identification since lead users can readily identify leading-edge status counterparts [

42]. Various scholars have classified innovation as a scientific discipline, a process or an outcome [

5,

12]. The literature is replete with research into financial technology innovation. However, there is limited research into understanding how lead user innovation partnership is perceived and narrated in practice.

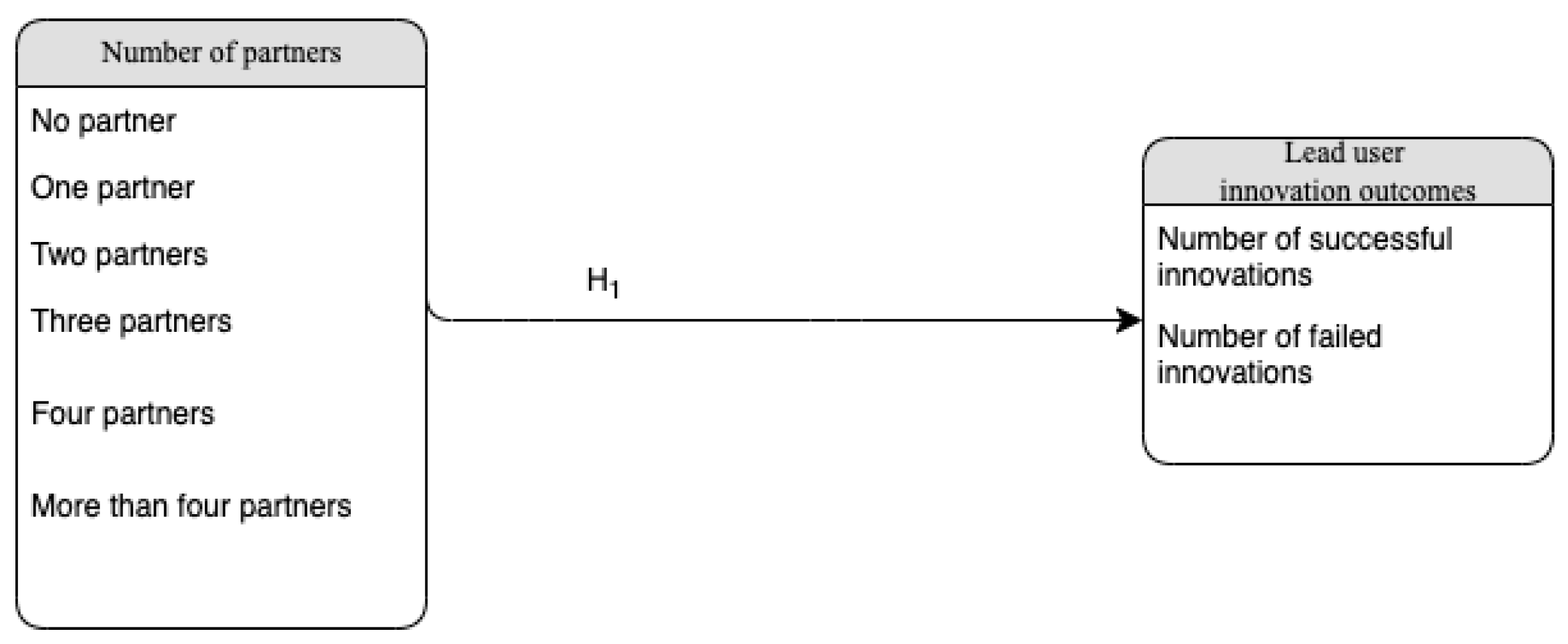

3. Conceptual Framework

Figure 1 below describes the conceptual framework used in the study.

Based on the objective and the literature review, a hypothesis was derived.

H1: The number of Lead user innovation partners have no impact on innovation outcomes in the financial technology sector.

The researcher began by looking at the methodology to test the research hypothesis.

4. Methodology

The purpose of the study was to gain an understanding of the influence of partnerships on innovation outcomes. The previous debates provide the need for this study to focus on the lead user as a unit of analysis and quantitative research. Scholars agree that a quantitative study design generates a reliable assessment in research [

29]. Quantitative research has been used in previous similar studies [

9,

32,

38]. This study used Taro Yamane’s formula to determine the sample size due to the challenge of establishing the actual population of lead users [

44]. The formula, which generated a sample size of 399 respondents, considered the country’s population of 47.3 million. The population offered a large and diverse sample since lead users are a large and diverse group. However, purposive sampling generated 321 lead users. The study examined the relationship between the number of lead user partners and innovation outcomes.

Data Treatment for the Number of Partners and Outcomes

The quantitative data collected were analyzed using SPSS software. For the number of partners, the researcher had six measurements no partners, one partner, two partners, three partners, four partners and more than four partners.

Table 1 depicts the number of partners that lead users engaged during the innovation process.

Table 1 shows that 3.7% of the lead users had no partners, while 96.3% had some form of partnership with one or more other users.

Successful innovations were reclassified from the absolute number of successful innovations per lead user to a clustered format comprising less than three and three or more successful ones. This was necessary to reduce the number of iterations in evaluating the impact of the independent variables on successful innovations.

Table 2 shows the reclassification of the number of successful financial technology innovations developed by the lead users.

Two categories were derived—3 or more successful innovations developed by a lead user; and less than three successful innovations developed. 23.9% of the lead users developed three or more innovations, while 76.1% developed less than three financial technology innovations during the study period.

The data was not reclassified for failed innovations and is shown in

Table 3.

Having all the measurement indicators in place, a correlation analysis using SPSS was conducted for each dependent variable to determine the strength of the correlation and the direction. The analysis helped determine how the independent variables affected each dependent variable. The quantitative data analysis yielded results, as discussed in the next section.

5. Results/Summary of Key Findings

The main objective of this study was to examine the relationship and influence of the number of lead user partners on innovation outcomes. The next section looks at the results obtained from the data analysis.

5.1. Influence of the Number of Partners on the Number of Successful Innovations

A reliability test is included to show the reliability of the data collected.

Based on the number of successful innovations as the dependent variable,

Table 4 shows that “4 partners” and “More than 4 partners” are the significant measurement indicators at 0.01 level of significance.

The B coefficient for the measurement indicator “0 partners” is the only variable with a negative coefficient. All other variables had a positive B coefficient. The negative coefficient implies that there is an inverse relationship between the lead user having no partners and the successful innovation. This means that the likelihood of successful innovation will decrease with no partners and vice versa.

5.2. Influence of Lead User Partners on Failed Innovations

Table 5 shows the results of the influence of the six predictors in the partners model for the number of failed fintech innovations.

Only the variable “4 partners” is significant at 0.05 level of significance. It is curious that having four partners is significant for both successful and failed innovations. The next section discusses the findings.

6. Discussions

This study extended and integrated lead user theory and creativity concepts by exploring lead users’ partnership choices and their impact on innovation outcomes.

The number of partners was significant for four or more partners in the case of successful and failed innovations. This finding provides new insight into the relationship between the lead user and the number of partners they need for success. The finding implies that many partners in the innovation process can equally cause success or failure, suggesting that choosing partners rather than the number could be the key to success or failure. This finding supported the notion that we democratize innovation and that firms and individual users can increasingly innovate for themselves [

41].

The theoretical implications are that innovation partnership is influential in both success and failure and should be considered from that point of view in future enhancement of theory. The practical implications are that the lead user must carefully select the number of partners to succeed in the innovation. This is supported by proponents of democratizing innovation [

24,

41]. There is, however, a need to examine the reasons for success or failure based on the types of partners.

In summary, the number of partners enhances the chances of success or failure in lead user innovation. While most literature has focused on the single innovator, this study brings forward the reality that lead users need to work with partners during their innovation. This premise supports the scholars who state that social networks are important for lead user innovation [

15,

27,

32].

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study examined the significance of the number of innovation partners on lead users’ innovation outcomes. It focused on innovation in the context of a developing country’s approach to user participation and hence fulfilled the contextual gap. Based on the results, it can be concluded that the number of partners is important to any innovation. The hypothesis is therefore rejected. The results indicate that innovation partners are significant players based on their influence on the innovation outcome.

7.1. Practical Applications

Lead user partnerships are significant because they allow companies to gain valuable insights and feedback from their most engaged and knowledgeable customers. These users are often early adopters of new products and technologies, and they can provide valuable input on product design, functionality, and marketing strategies. Additionally, lead user partnerships can help companies identify new opportunities for innovation and growth. By working closely with lead users, companies can develop products and services that better meet the needs and desires of their target market, which can help to increase customer satisfaction and loyalty.

The findings contribute to the industry in several ways. First, including the number of partners enhances the identification of success factors for lead users that can be engaged in innovative endeavours at the industry or firm level. Managers should involve more partners in the innovation process to increase the likelihood of successful innovation outcomes. This can prove quite timely for executives who must select a team of innovators for a successful innovation outcome.

Second, partners, being influencers, can be streamlined based on other factors, such as innovation processes or diverse ideas, to save valuable resources for the lead users or the firm. This might bring about a faster innovation roadmap for various fintech innovations.

7.2. Suggestions for Future Research

The study has opened new areas for further research. There is a need to explore the various types of partnerships, for example, long-term versus short-term, major versus minor partners, or partners at different stages of the innovation cycle, to determine which model works best and delivers greater success.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Geoffrey Otieno and Ruth Kiraka; methodology, Geoffrey Otieno and Ruth Kiraka; software, Geoffrey Otieno.; validation, Geoffrey Otieno and Ruth Kiraka; formal analysis, Geoffrey Otieno and Ruth Kiraka; investigation, Geoffrey Otieno; resources, Geoffrey Otieno; data curation, Geoffrey Otieno and Ruth Kiraka; writing—original draft preparation, Geoffrey Otieno and Ruth Kiraka; writing—review and editing, Geoffrey Otieno and Ruth Kiraka; visualization, Geoffrey Otieno and Ruth Kiraka; supervision, Ruth Kiraka.; project administration, Geoffrey Otieno and Ruth Kiraka; funding acquisition, Geoffrey Otieno. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the NATIONAL COMMISSION FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION (License Permit No 287229), and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of STRATHMORE UNIVERSITY (protocol code SU-IERC0868/20 and date of approval – 24TH AUGUST 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available on request due to restrictions. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns and restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Andiva, B. Mobile Financial Services and Regulation in Kenya. In Proceedings of the 1st Annual Competition and Economic Regulation (ACER) Conference, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, 16–21 March 2015; Available online: https://www.competition.org.za/s/Barnabas-Andiva_Mobile-Money-Kenya.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2022).

- Antorini, Y.M.; Schultz, M. Brand Revitalization through User-Innovation: The Adult Fan of LEGO Community. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Reputation Brand Identity Competitiveness, BI Norwegian School of Management, Oslo, Norway, 31 May–3 June 2007; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Brem, A.; Bilgram, V.; Gutstein, A. Involving Lead Users in Innovation: A Structured Summary of Research on the Lead User Method. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2018, 15, 1850022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogaard, L. Innovative outcomes in public-private innovation partnerships: A systematic review of empirical evidence and current challenges. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Towards New and Multiple Perspectives on Innovation. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2017, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.a. A new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, E.; Fosselle, S.; Rogge, E.; Home, R. An analytical framework to study multi-actor partnerships engaged in interactive innovation processes in the agriculture, forestry, and rural development sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.S.; Wu, F. Customer involvement in innovation: A review of literature and future research directions. In Review of Marketing Research. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Foege, J.N.; Piening, E.P.; Salge, T.O. Don’t get caught on the wrong foot: A resource-based perspective on imitation threats in innovation partnerships. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 1750023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, N.; von Hippel, E.; Schreier, M. Finding commercially attractive user innovations: A test of lead-user theory. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2006, 23, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. Challenges and Opportunities. In Innovation Strategies in the Food Industry: Tools for Implementation; Academic Press, Elsevier: 2016. [CrossRef]

- Garud, R.; Tuertscher, P.; Van De Ven, A.H. Perspectives on innovation processes. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2013, 7, 775–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürkan, G.Ç. Identification of Lead User Characteristics The Case of Surgeons in Turkey. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 6, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hienerth, C.; Lettl, C. Perspective: Understanding the Nature and Measurement of the Lead User Construct. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2017, 34, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, C.; Kaminski, J.; Piller, F. Accentuating lead user entrepreneur characteristics in crowdfunding campaigns—The role of personal affection and the capitalization of positive events. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2019, 11, e00106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyysalo, S.; Johnson, M.; Juntunen, J.K. The diffusion of consumer innovation in sustainable energy technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, S70–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, L.B.; Molin, M.J. Consumers as co-developers: Learning and innovation outside the firm. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2003, 15, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaulartz, S.; von Hippel, E.A. AI Method for Discovering Need-Solution Pairs. Geoscientist 2018, 28, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koellinger, P. Why are some entrepreneurs more innovative than others? Small Bus. Econ. 2008, 31, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfqvist, L. Product innovation in small companies: Managing resource scarcity through financial bootstrapping. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 1750020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. Mission-oriented innovation policies: Challenges and opportunities. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2018, 27, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendrick, D.G.; Wade, J.B. Frequent incremental change, organizational size, and mortality in high-technology competition. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2009, 19, 613–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlecnik, E. Opportunities for supplier-led systemic innovation in highly energy-efficient housing. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollick, E.; Robb, A. Democratizing Innovation and Capital Access: The Role of Crowdfunding. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G. Images of organization. In Sage Publication, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndemo, B.; Weiss, T. Digital Kenya: An Entreprenurial Revolution in the Making. In Palgrave Macmillian (Issue July). 2017. [CrossRef]

- Oo, P.P.; Allison, T.H.; Sahaym, A.; Juasrikul, S. User entrepreneurs’ multiple identities and crowdfunding performance: Effects through product innovativeness, perceived passion, and need similarity. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 105895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosted, J. User-Driven Innovation: Results and Recommendations. Design 2005, 106, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research methods for business students. Eighth Edition. In Pearson Education, UK, 8th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2019; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. In Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle; Harvard Economic Studies: 1934. [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, J. How contracts and culture mediate joint transactions of innovation partnerships. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2016, 20, 1650005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servajean-Hilst, R.; Donada, C.; ben Mahmoud-Jouini, S. Vertical innovation partnerships and relational performance: The mediating role of trust, interdependence, and familiarity. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 97, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, C.; Ahmed, P.K. From product innovation to solutions innovation: A new paradigm for competitive advantage. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2000, 3, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundbo, J. Blocking mechanisms in user and employee based service innovation. Econ. Et Soc. 2013, 47, 479–506. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, G.M.P. A Welcome Revolution in Innovation. Int. J. Econ. Bus. 2017, 24, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidd, J.; Bessant, J. Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change, 5th Edition—Joe Tidd, John Bessant. In Managing Innovation: Integration Technological, Market and Organizational Change, 5th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vikkelsø, S.; Skaarup, M.S.; Sommerlund, J. Organizational hybridity and mission drift in innovation partnerships. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 25, 1348–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hippel, E. Lead Users: A Source of Novel Product Concepts. Manag. Sci. 1986, 82, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hippel, E. Chapter 1 Introduction.pdf. In Democratizing Innovation; 2015.

- von Hippel, E. Democratizing Innovation: The Evolving Phenomenon of User Innovation. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2009, 1, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hippel, E.; Franke, N.; Prügl, R. Pyramiding: Efficient search for rare subjects. Res. Policy 2009, 38, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hippel, E. Free Innovation. In Free Innovation (Vol. 1, Issue 1). The MIT Press: 2017.

- Yamane, T. Statistics, An Introductory Analysis, 2nd ed.; Harper and Row: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1967; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).