1. Introduction

Sunlight is electromagnetic radiation, with a full range of wavelengths, from ultraviolet UV radiation (UVA, UVB and UVC in the range of 200 - 400 nm), through visible radiation (in the range of 400 - 800 nm) to infrared IR radiation (IRA, IRB and IRC in the range of 800 – 15.000 nm). Ultraviolet radiation has the most significant effect on the human body of all types of radiations. Seventy percent of UVB radiation that reaches the skin is absorbed by the stratum corneum, 20% goes to the spinosum and basal layer of the epidermis, and only 10% penetrates the papillary layer of the skin dermis [

1]. UVA radiation is partially absorbed by the epidermis, but as much as 20-30% reaches the deep epidermal reticular layer of the dermis [

2]. Unlike UVB radiation, UVA radiation, due to its high penetration properties, reaches deeper parts of the skin and affects dermal compartments. When exposed to UVA radiation at a dose of 25 J/cm², dermal fibroblasts located in the upper layer of the skin die within 48h of exposure through an apoptotic process. In contrast, the structure and organization of the epidermis did not change significantly. Studies confirm that dermal fibroblasts are more sensitive to UVA-induced oxidative stress than keratinocytes [

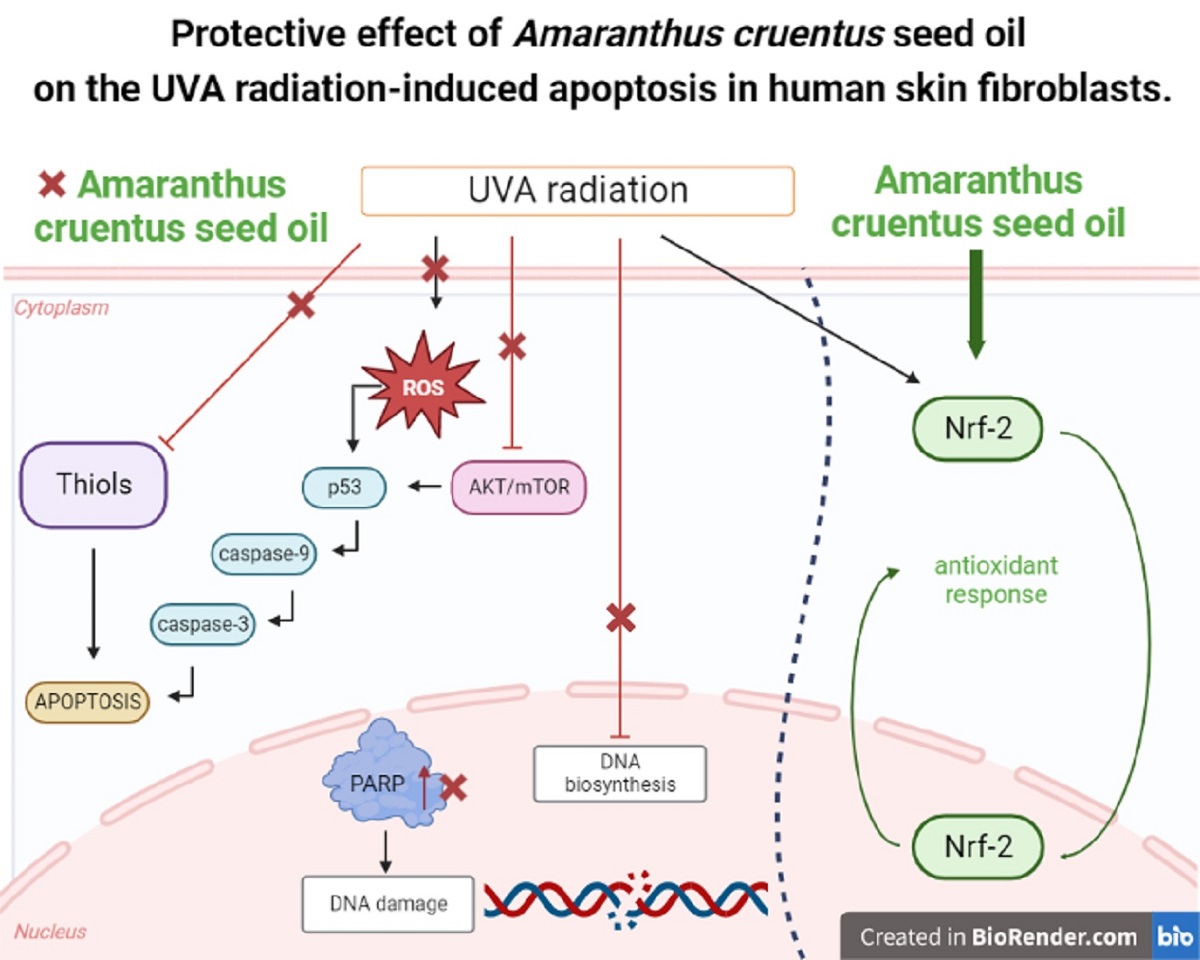

3]. UV radiation generates free radicals that can result in cellular stress, DNA damage which leads to activation of the p53 suppressor protein. Activation of p53 protein in irradiated cells leads to the cell cycle arrest to allow repair of DNA damage. However, when the damage is extensive or repair is impossible, it induces apoptotic cell death via the intrinsic (mitochondrial) caspase-9 – dependent pathway of apoptosis. Activated caspase-9 then cleaves and activates effector caspases, such as caspase-3 and -7, which carry out apoptosis [

4,

5,

6]. UV also negatively affects the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, which is closely related to cell cycle arrest and the process of apoptosis. The AKT/mTOR signaling pathway can antagonize p53 activity in response to UV radiation. Shifting the balance between p53 activation and AKT/mTOR signaling may determine cell death or survival [

5]. Due to permanent exposure to damaging UV radiation, the cells of the different layers of the skin - epidermal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts - produce a number of protection mechanisms. They include high activity of repair and antioxidant enzymes, a large pool of non-enzymatic antioxidants and redox-sensitive transcription factors, including Nrf2, which is responsible for the expression of cytoprotective proteins [

7]. These processes become depleted during prolonged UV exposure, therefore search for effective skin-protective compounds with cytoprotective and antioxidant properties are required. One of potential sources of such a compound are seed oils with free fatty acids, vitamins, sterols, carotenoids and phenols [

4]. Such a good source is seed oil from

Amaranthus cruentus L. Its cytoprotective and antioxidant potential is due to the presence of unsaturated fatty acids, among which linoleic acid, commonly used as an antioxidant, predominates. In addition, it also contains squalene, vitamin E and its derivatives such as γ, δ-tocotrienols, and phytosterols [

8]. However, the effects of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil on UVA-treated cells is unknown. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the protective effect of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil on UVA-stimulated apoptosis in a cellular model of human skin fibroblasts.

2. Results and Discussion

The skin, being the largest organ of the human body, has the most direct contact with external factors, especially sunlight. Prolonged exposure to UV radiation causes photoaging, which is superimposed on aging caused by the passage of time (chronological aging). During skin exposure, UV energy is absorbed by endogenous cellular chromophores, with their excitation, which occurs in the presence of molecular oxygen, producing a number of oxidation products and reactive oxygen species (ROS). This leads to oxidative-reductive stress resulting inhibition of collagen synthesis, damage to DNA, proteins, lipids aberrations in biological membrane structures and regulation of fibroblast function [

9].

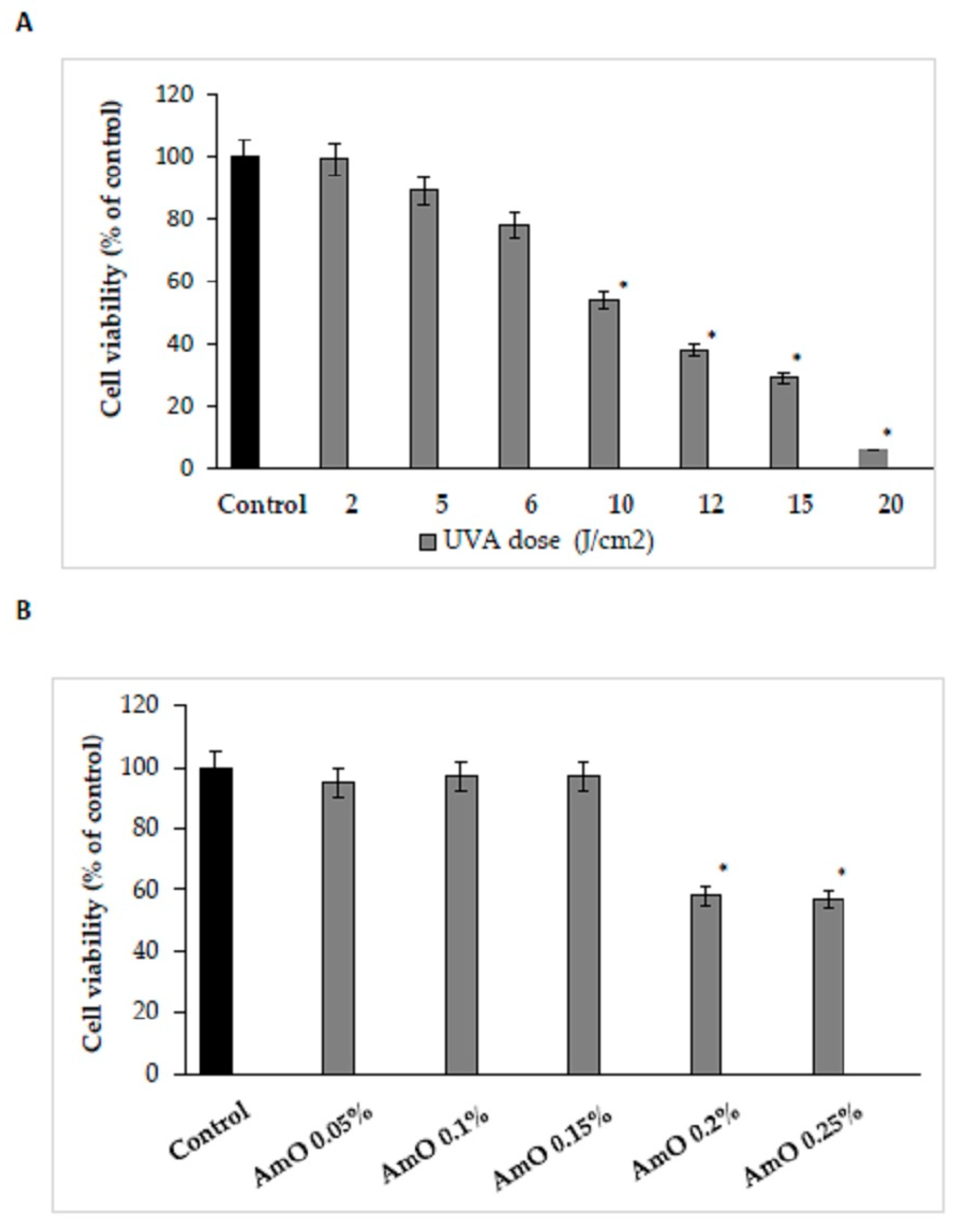

Therefore, the effect of UVA radiation on the above processes was studied in human skin fibroblasts. The cells were exposed to UVA at different doses as shown in

Figure 1A. It was found that fibroblast viability decreased with increasing UVA dose. Doses of 2 J/cm

2 and 5 J/cm

2 did not significantly affect the viability of the cells. Doses of 6 J/cm

2 and 10 J/cm

2 reduced fibroblast viability to about 78% and 54% of control value, respectively. Doses of 12 J/cm

2, 15 J/cm

2 and 20 J/cm

2 reduced fibroblast viability to about 38%, 29%, and 6% of control value respectively. Based on the experiment, a dose of 10 J/cm

2, contributing to about IC50 value of cell viability, was selected for further experiments.

The natural mechanisms that counteract the negative effects of ROS, include up-regulation of lipid synthesis, replenishing epidermal barrier components and regeneration of expended antioxidants. The external factors, including UV radiation deplete the components. For this reason, new substances of natural origin that exhibit such activity are being sought [

7]. Amaranthus cruentus seed oil is characterized by the presence of linoleic acid, oleic acid, squalene and α-β-, γ- and δ-tocopherols. Linoleic acid, commonly used as an antioxidant, dominates. Squalene, present in the oil's composition, is found in the skin in sebum, and is also part of the epidermal barrier and protects the skin from various external factors, including UV radiation [

10,

11]. Due to its chemical composition, Amaranthus cruentus seed oil has cytoprotective and antioxidant potential, and has prospects for use as a substance for skin care against UV radiation [

12]. We found that the effect of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil on cell viability varied depending on the concentration used. The application of low concentrations (0.05%, 0.1% and 0.15%) of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil had no significant effect on the viability of human skin fibroblasts. In contrast, the use of higher concentrations (0.2% and 0.25%) of this oil resulted in a decrease in cell viability to about 58% and 57% of the control value, respectively. The observed decrease in cell viability at high concentrations of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil was attributed to the physical effect of the oil itself on the cells, which led to their exclusion from further experiments (

Figure 1B).

Studies by Ko et al [

13] provided evidence that

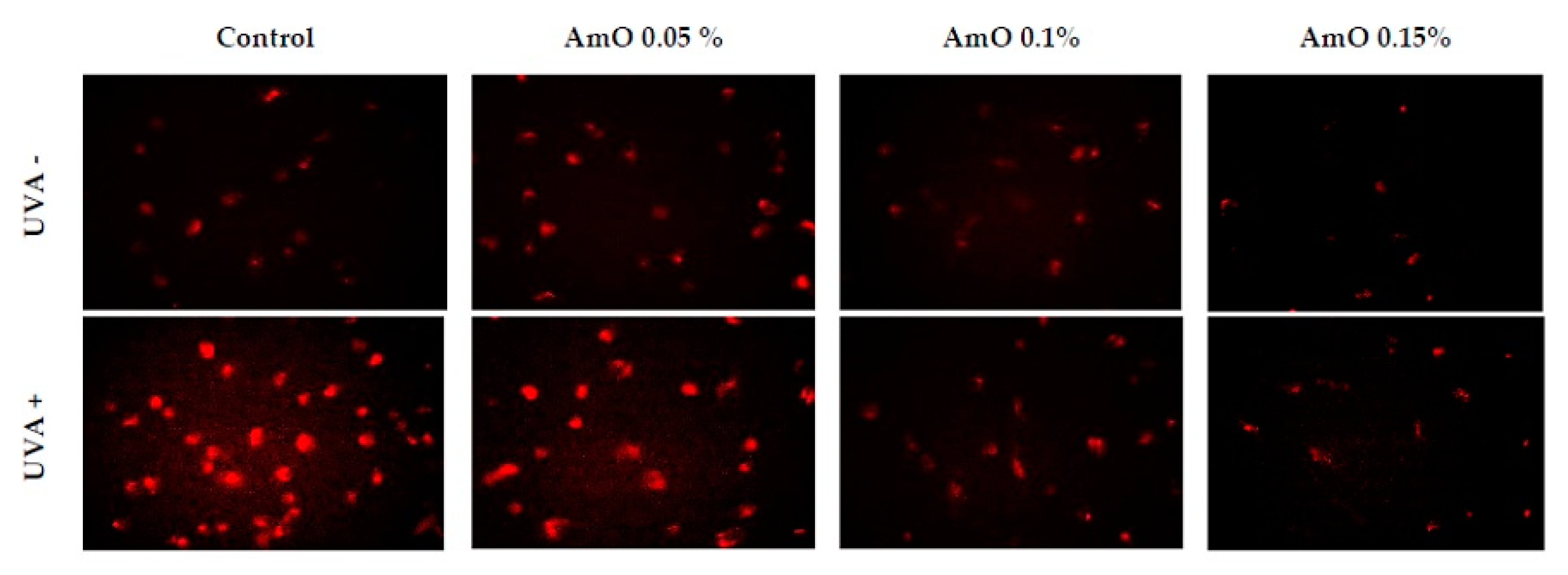

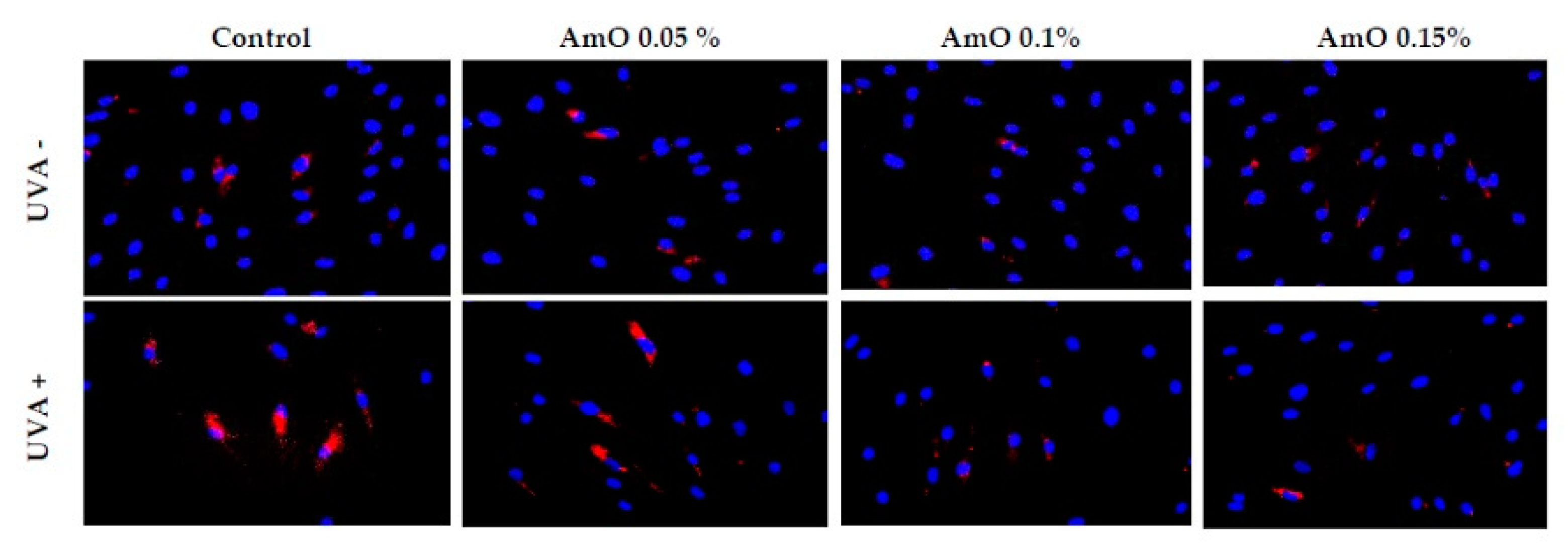

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil exhibited of both antioxidant and pro-oxidant effects in human lung fibroblasts. At low concentrations of the oil, fibroblasts were protected from oxidative stress, while incubation with high concentrations of the oil resulted in increase in intracellular ROS generation and cell damage. Our studies indicate a cytotoxic effect of UVA radiation on human skin fibroblasts and its involvement in the generation of significant amounts of ROS. Considering that ROS are suppressors of basic cellular functions as well as pro-apoptotic factors, we investigated the protective-antioxidant potential of

Amaranthus cruentus seeds at selected concentrations in UVA-treated human skin fibroblast cells. The study indicated that UVA radiation generates significant amounts of ROS in the studied cells. Treatment with 0.05% concentration of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil reduced the formation of ROS, but not as significantly as at concentrations of 0.1% and 0.15% oil (

Figure 2). Reduced ROS level in fibroblast exposed to UVA was also noted in the presence of other oils such as sea buckthorn seed oil. Treatment with sea buckthorn seed oil prevented UVA-induced redox imbalance in fibroblasts. It was found that incubation of fibroblasts with sea buckthorn oil caused a decrease in ROS generation by about 25% [

7,

14].

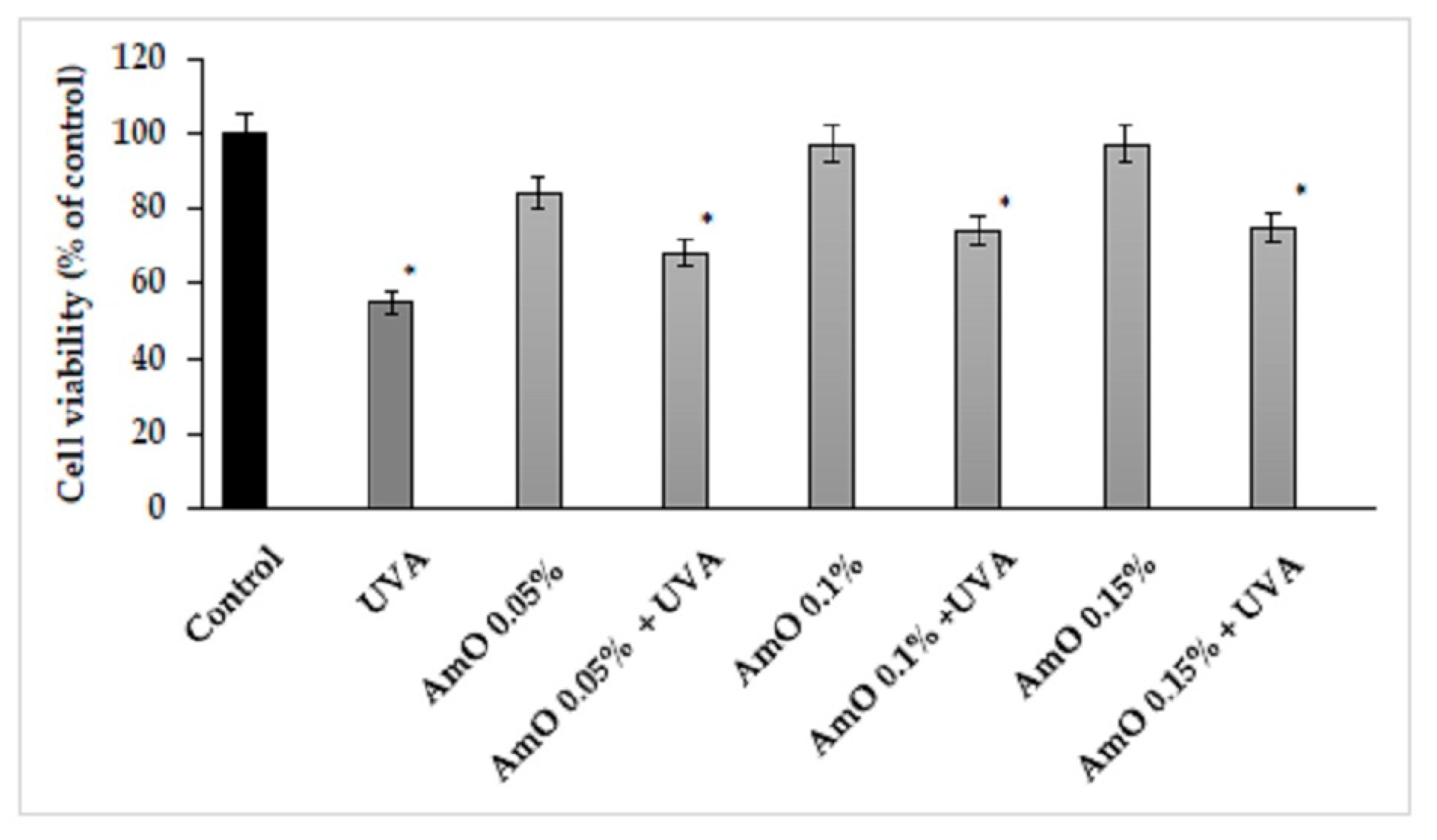

Based on the results obtained in MTT test, we observed that the survival rate of cells treated with UVA at a dose of 10 J/cm

2 was decreased by 45%, and this was a statistically significant difference, compared to the control (p<0.05). Comparing the effect of UVA on cells in the presence of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil at 0.05%, 0.10%, and 0.15% concentrations we observed that the cell survival was 13%, 19%, and 23% higher, respectively, than in the UVA-treated group, and these effects were statistically significant (p<0.05). This data indicates antioxidant effect of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil at selected concentrations in UVA-treated fibroblasts (

Figure 3,

Table 1).

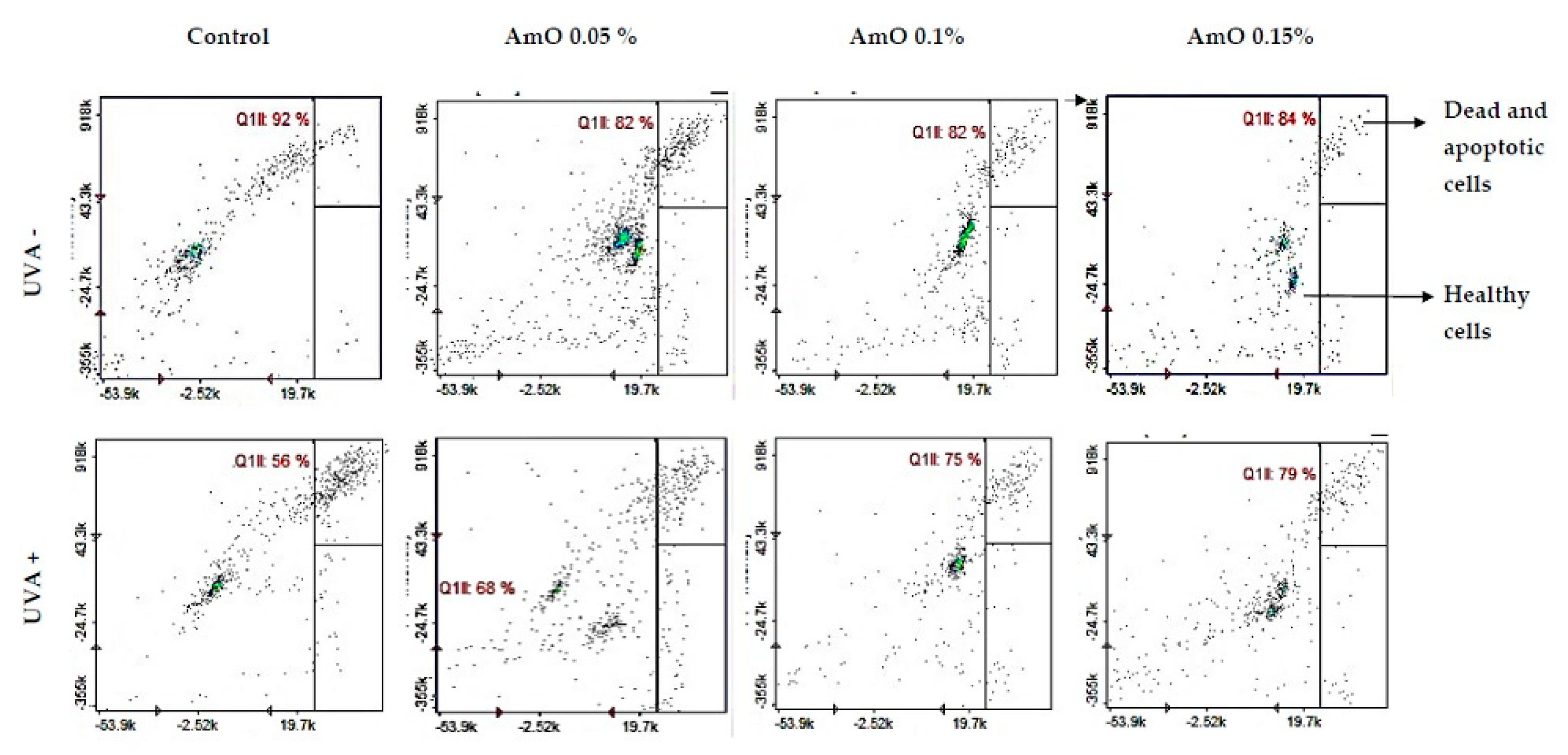

In MTT experiment, we found that UVA irradiation of human skin fibroblasts impairs their survival, while the presence of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil reverses the cytotoxic effect of UVA radiation on this process. However, the mechanism of this effect is unknown. Cytometric assays for apoptosis and cell survival were performed using Nucleo-Counter

® NC-3000

TM imaging cytometer. The survival rate of fibroblast treated with

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil, regardless of the concentration used, remained at 82 - 86%. In cells irradiated with UVA at a dose of 10 J/cm

2, a negative effect of this radiation on fibroblast survival was noted, which was about 56% of control.

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil at concentrations of 0.05%, 0.1% and 0.15% counteracted the toxic effect of UVA on the cells, whose survival rate was reduced, but to a lower level, to about 68%, 75% and 79% of the values obtained in the UVA treated group, respectively (

Figure 4).

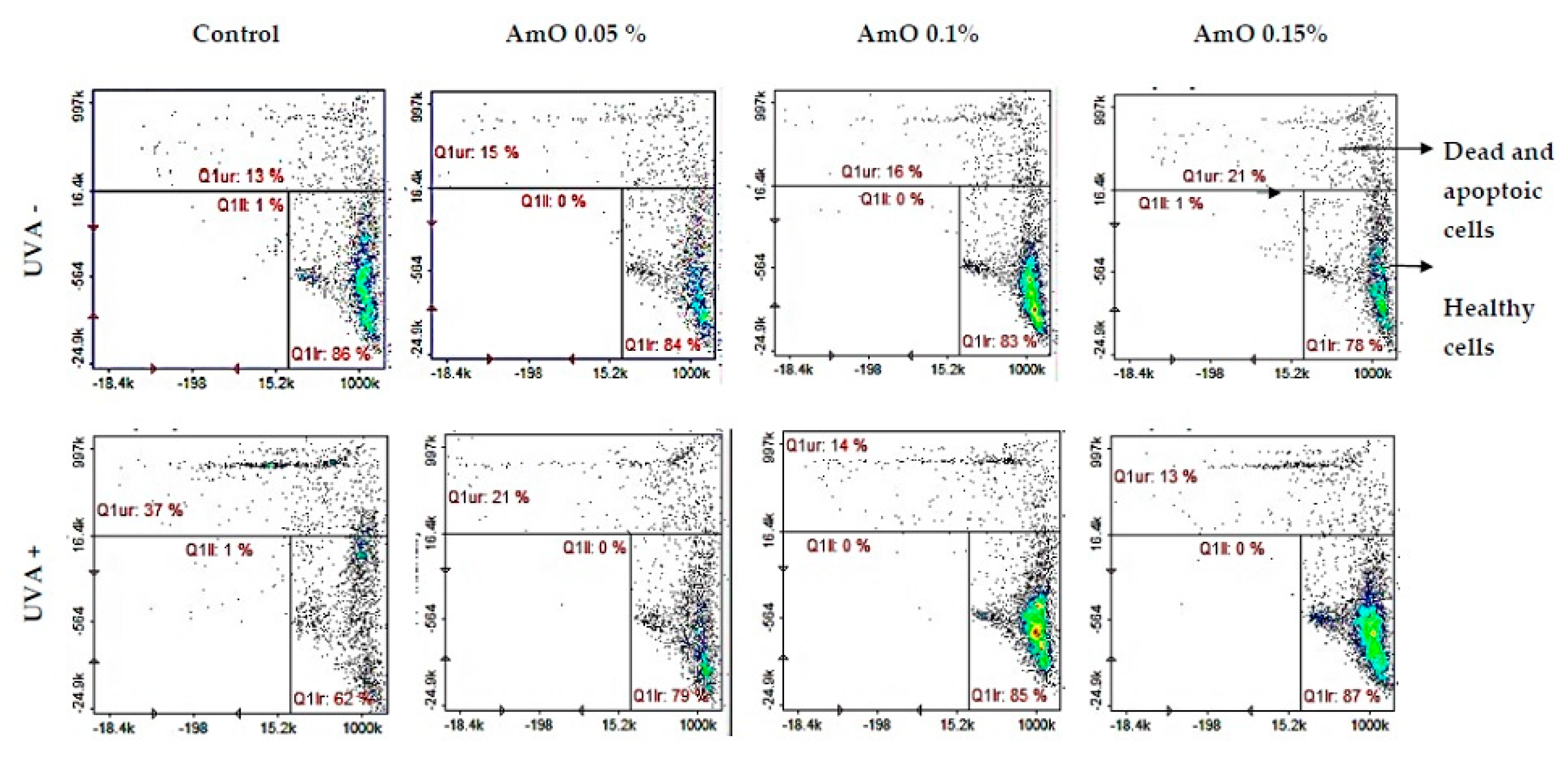

The redox balance is essential for physiological function of the cell. Under physiological conditions, the cytosol has a highly reducing environment due to high level of reduced glutathione and a complex redox enzyme system that maintains glutathione in a reduced state. In most eukaryotic cells, cysteine thiols of proteins are the most sensitive to changes in the cellular redox state, and 98% of thiols remain in a reduced form. Oxidative stress contributes to non-selective and irreversible oxidation of protein thiols, glutathione depletion and cell death. Thus, the content of reduced thiols is indicator of ROS formation and apoptosis [

13]. A study by Emonet et al [

15] indicated that UVA sensitivity of human skin fibroblasts is associated with a decrease in their intracellular glutathione (GSH) level. In our studies we have found that

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil alone caused a slight decrease in the level of reduced thiols, which remained at 78 - 88% of control. In contrast, in the UVA-irradiated cells, a negative effect of this radiation on the level of reduced thiols was noticed, which was about 62% of control. Comparing the effect of UVA on the cells cultured in the presence of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil at concentrations of 0.05%, 0.1% and 0.15%, the level of reduced thiols increased to about 79%, 85% and 87% of control respectively (

Figure 5). This suggests that the tested oil has a protective effect on the UVA-induced disturbances in the oxidation-reduction balance in fibroblast.

Studies by Bernard et al [

16] indicate that in contrast to UVB, UVA radiation at doses consistent with realistic sun exposure induces oxidative stress in cells. UVA produces singlet oxygen, which depolarizes mitochondrial membranes, and induces oxidative damage to DNA, inducing late apoptosis. In contrast, UVB causes only late apoptosis. Interestingly, exposure to UVA in vivo did not induce apoptosis in epidermal cells. These results were confirmed in reconstructed UVA-treated skin, in which apoptosis was observed in fibroblasts of the dermis, but not in epidermal keratinocytes [

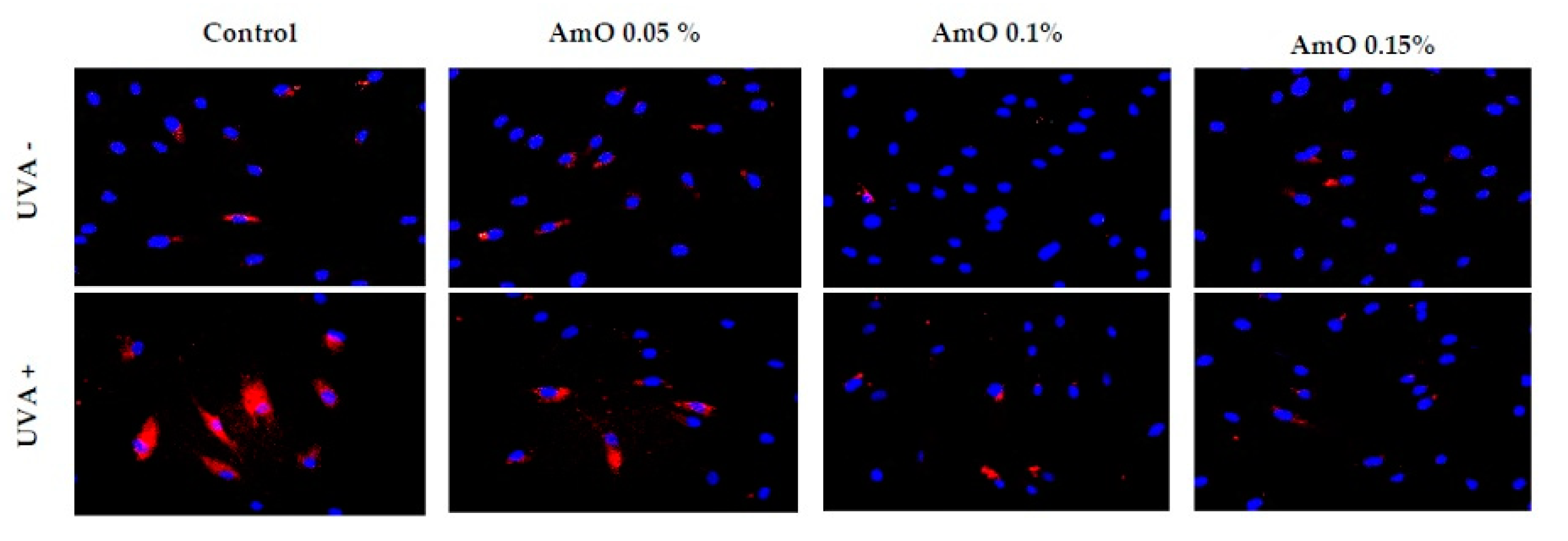

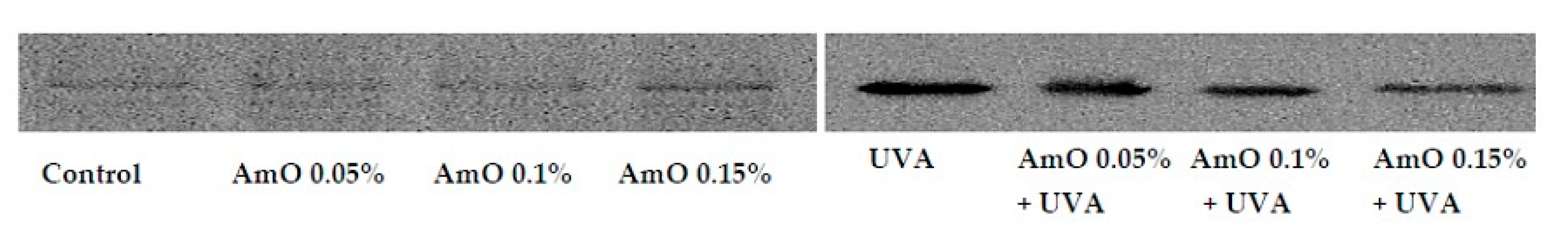

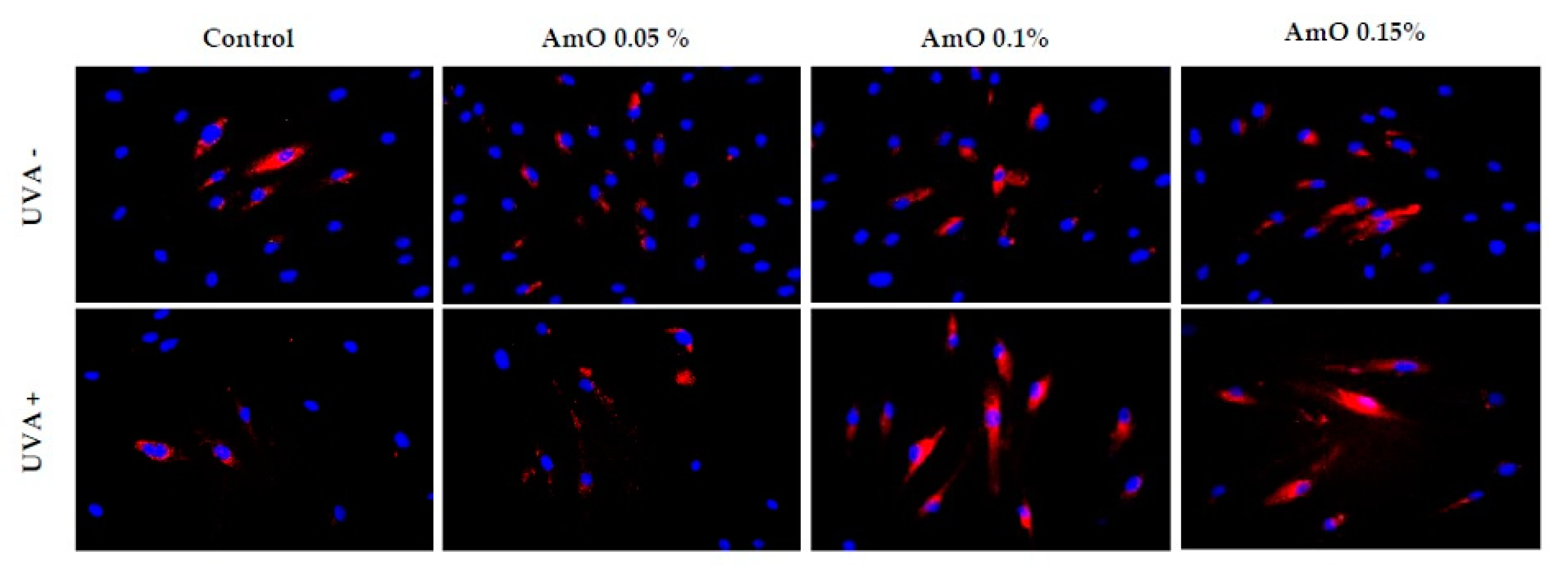

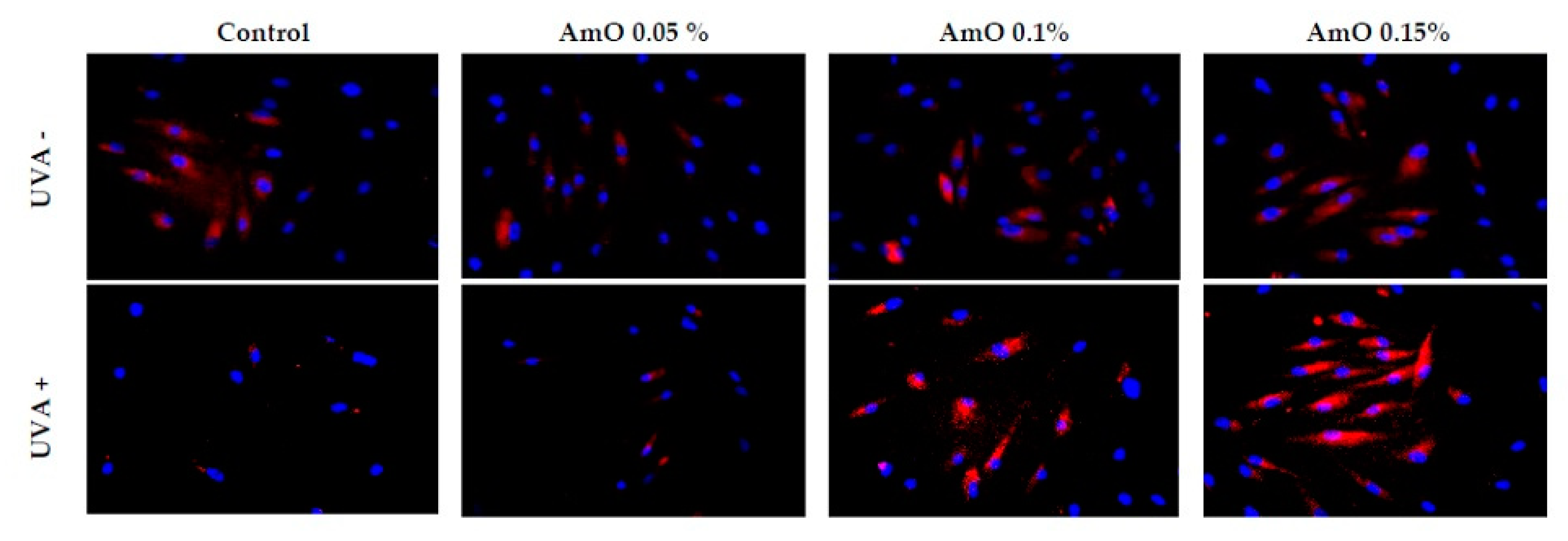

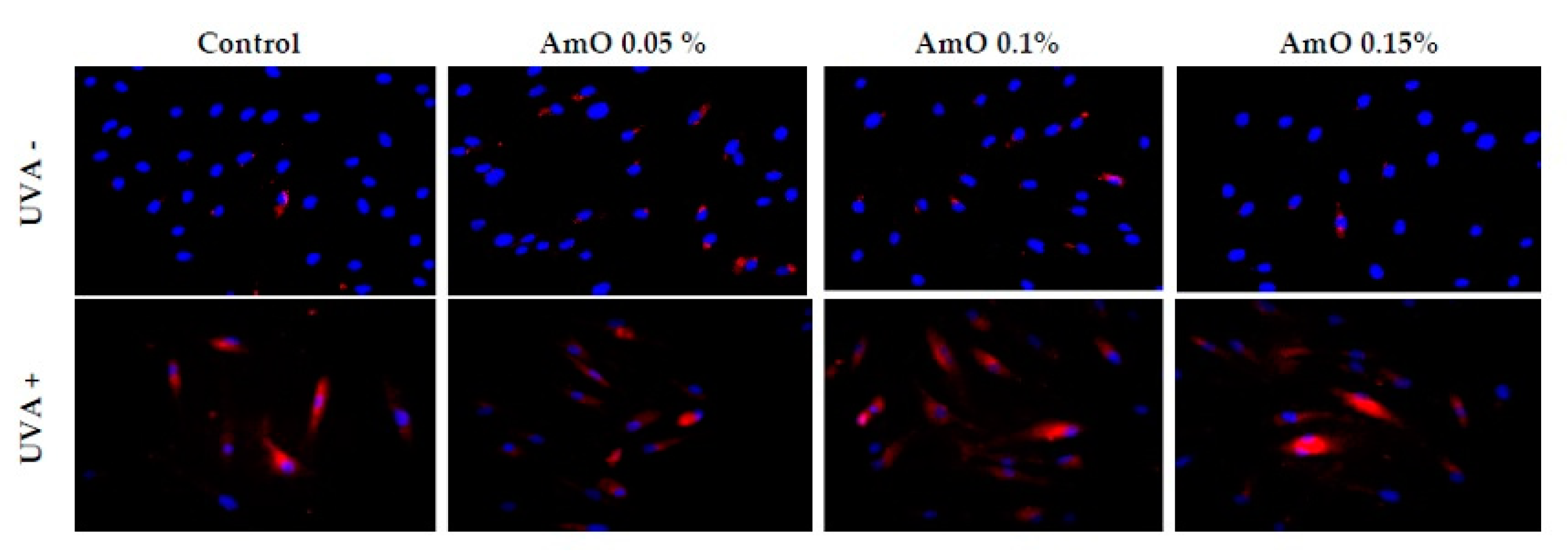

17]. Our study indicated that UVA radiation at a dose of 10 J/cm

2 significantly reduced the survival rate and induced apoptosis of fibroblasts. Application of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil at concentrations of 0.1% and 0.15% significantly reduced these processes (

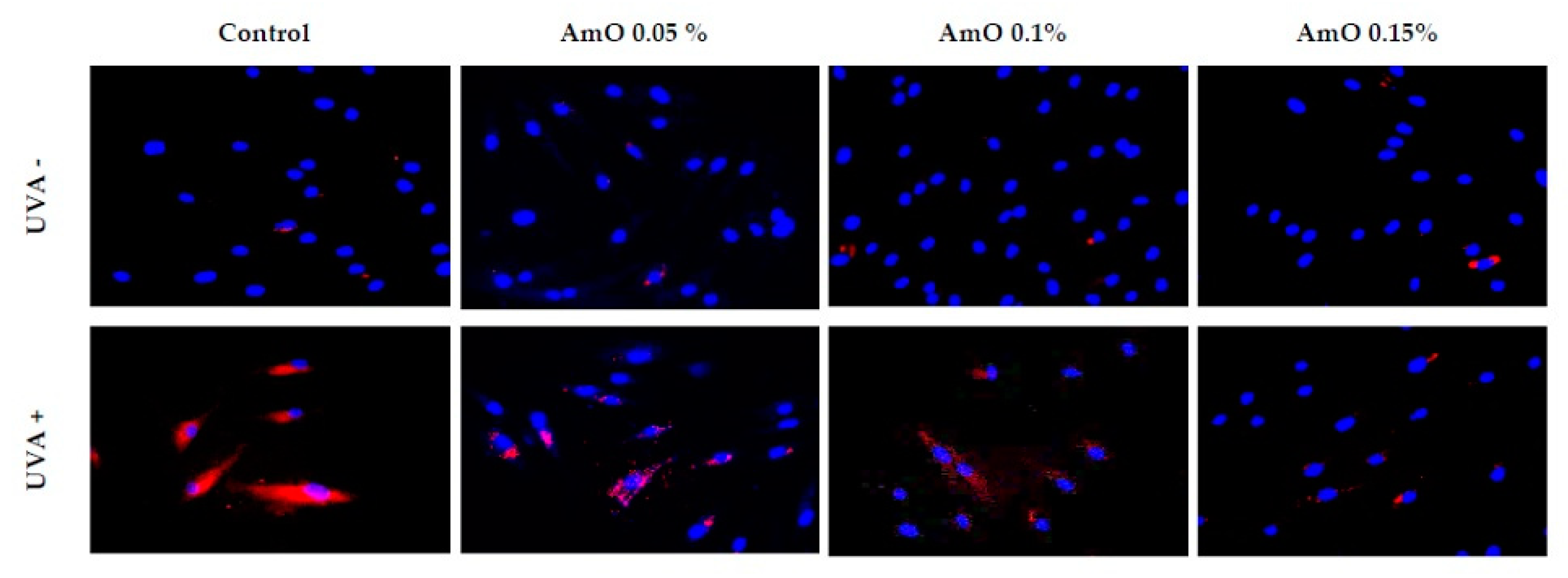

Figure 5). We also demonstrated that the used dose of UVA radiation induced the intracellular apoptosis pathway, that was accompanied by a significant increase in the expression of the apoptosis-inducing factor p53 protein (

Figure 6), as well as caspase-9 (

Figure 7) and caspase-3 (

Figure 8), which play a key role in this process. Treatment of the cells with selected concentrations of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil caused a decrease in the expression of these proteins, which are the markers of apoptosis. It suggests that UVA-dependent activation of apoptosis through the intrinsic pathway is inhibited by

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil in fibroblasts.

To maintain the integrity of the skin barrier, cells respond to UV by engaging other mechanisms by which, they can survive under stress conditions. Among them is AKT/mTOR and p53 signaling as a potential regulator of life and death of irradiated cells [

15]. Our study indicated a decrease in the expression of AKT and mTOR proteins under UVA radiation. The expression of p53 protein was significantly increased. Application of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil reversed the negative effects of UVA irradiation on this pathways. It showed the strongest effect at 0.1% and 0.15% (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). The UVA-reduced expression of p-AKT and mTOR proteins was restored, and accompanied by increased cell survival and reduced p53 expression, suggesting pro-survival mechanism of tested oil.

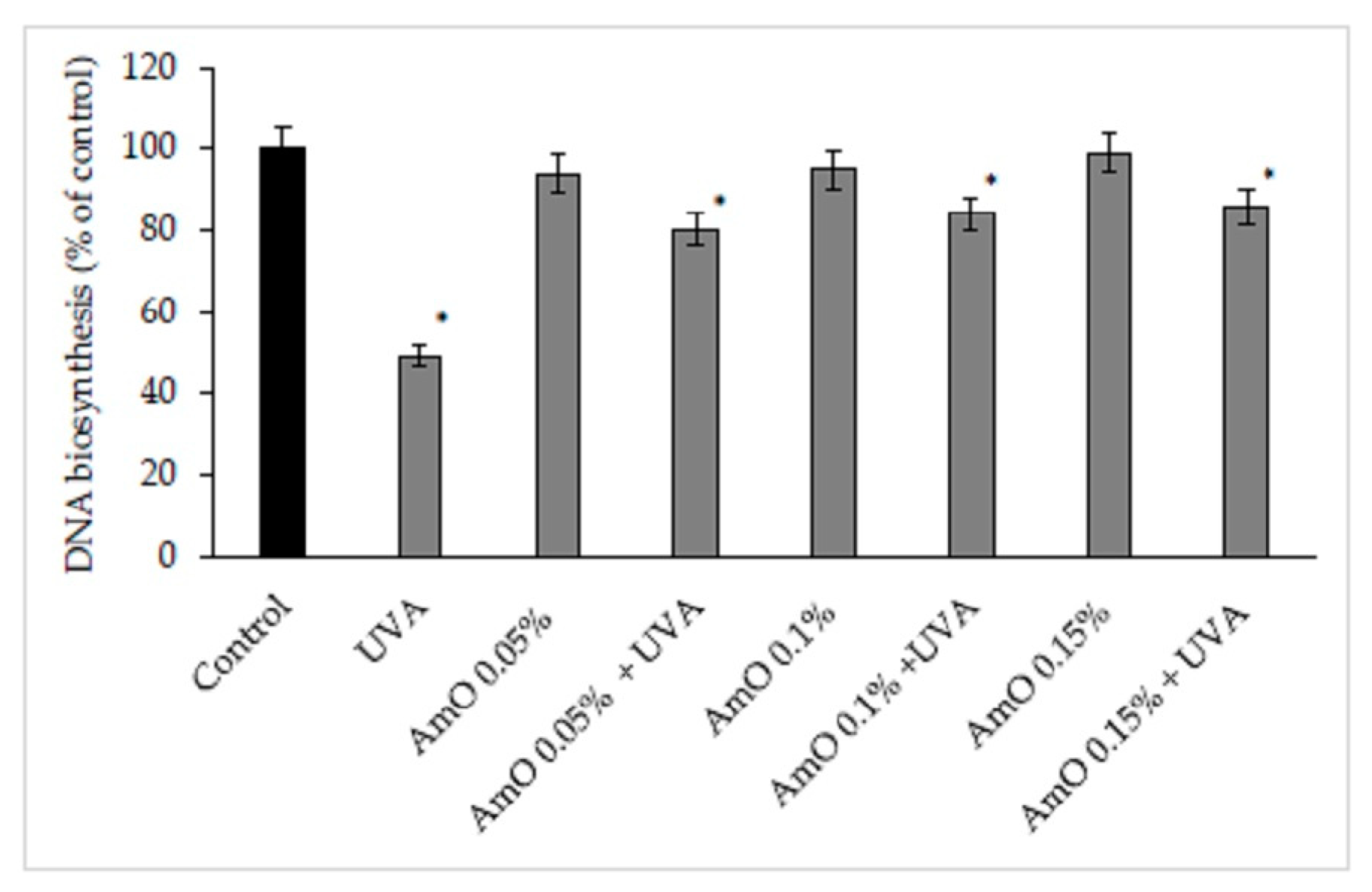

The reactive oxygen species lead to the formation of oxidation-generated DNA damage, such as single-strand breaks. UVA-induced DNA damage also leads to the mutations of proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, such as the previously described p53 [

16].

Amaranthus cruentus seed evokes also protective effect on the process of DNA biosynthesis in UVA-treated fibroblasts. In the UVA-treated cell, DNA biosynthesis decreased by 45%, compared to the control group. In the presence of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil at 0.05%, 0.10%, and 0.15% concentrations, DNA biosynthesis, was increased by 12%, 29%, and 31%, respectively despite the toxic effect of UVA, and this was statistically significant (p<0.05) (

Figure 11,

Table 2). Based on the obtained results, it can be assumed that the application of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil protects cellular DNA from the damaging effects of UVA radiation.

UV-induced DNA strand breaks initiate apoptosis. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) enzymes constitute a large family of 18 proteins. They represent enzymes that are activated immediately after DNA strand breaks, so the activity may be a marker of DNA damage [

16,

18]. We observed that UVA radiation, at the applied dose, increased the expression of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase protein (PARP). The use of 0.05% concentration of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil did not prevent increased PARP expression after UVA irradiation, while the use of this oil at 0.1% and 0.15% concentrations markedly reduced this process (

Figure 12). It shows that PARP proteins are involved in the mechanism of apoptosis occurring as a result of this radiation. Therefore, reduction in PARP protein expression under the influence of the applied concentrations of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil indicates its protective effect against the damaging effects of UVA radiation on DNA.

In this report we provide evidence that UVA-treated fibroblasts impairs DNA biosynthesis and reduces survival through activation of apoptosis, while the addition of

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil shows a protective effect on these processes. The molecular mechanism of this phenomenon is related to the activation of transcription factor Nrf2 [

19]. Translocation of the Nrf2 into the cell nucleus under oxidative stress conditions activates the expression of numerous cytoprotective genes that enhance cell survival. These include detoxification and antioxidant enzymes [

16]. In this study, we found increased expression of Nrf2 and its translocation to the nucleus in UVA-treated human skin fibroblasts, however, treatment with

Amaranthus cruentus seed oil enhanced this expression (

Figure 13). The above data suggest that the studied oil stimulate the antioxidant system in fibroblast and counteract the effects of UVA-induced oxidative stress through activation of the Nrf2-dependent pathways. Similar results were observed for sea buckthorn seed oil. Treatment of UV-irradiated skin cells with this oil promoted the antioxidant activity in the cells through Nrf2 activation [

7].

Figure 1.

Cell viability (A) under different doses of UVA radiation, (B) in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil at concentrations of 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.15%, 0.2%, and 0.25% of human skin fibroblasts. The mean values ± standard error (SEM) from the 3 experiments, performed in triplicates, are presented at * p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Cell viability (A) under different doses of UVA radiation, (B) in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil at concentrations of 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.15%, 0.2%, and 0.25% of human skin fibroblasts. The mean values ± standard error (SEM) from the 3 experiments, performed in triplicates, are presented at * p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence analysis of reactive oxygen species generation in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1% and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Red fluorescence intensity represents amount of generated ROS. The images were obtained at a 20x magnification.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence analysis of reactive oxygen species generation in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1% and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Red fluorescence intensity represents amount of generated ROS. The images were obtained at a 20x magnification.

Figure 3.

Cell viability in fibroblast treated with Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated and UVA-treated (+ UVA) cells. The mean values ± standard error (SEM) from the experiments, performed in triplicates. (*statistically significant difference p < 0.05 compared to control).

Figure 3.

Cell viability in fibroblast treated with Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated and UVA-treated (+ UVA) cells. The mean values ± standard error (SEM) from the experiments, performed in triplicates. (*statistically significant difference p < 0.05 compared to control).

Figure 4.

Cytometric assay of apoptosis in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. The cells were stained with fluorescent dyes using Propidium Iodide and Annexin V.

Figure 4.

Cytometric assay of apoptosis in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. The cells were stained with fluorescent dyes using Propidium Iodide and Annexin V.

Figure 5.

Cytometric assay of reduced thiols level in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. The cells were stained with fluorescent dyes Propidium Iodide and VB-48TM.

Figure 5.

Cytometric assay of reduced thiols level in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. The cells were stained with fluorescent dyes Propidium Iodide and VB-48TM.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence staining of p53 expression in fibroblast in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Blue staining indicates the nuclei, and red staining represents p53 expression. The images were obtained at a 20x magnification.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence staining of p53 expression in fibroblast in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Blue staining indicates the nuclei, and red staining represents p53 expression. The images were obtained at a 20x magnification.

Figure 7.

Immunofluorescence staining of caspase-3 expression in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Blue staining indicates the nuclei, and red staining represents caspase 3 expression. The images were obtained at 20x magnification.

Figure 7.

Immunofluorescence staining of caspase-3 expression in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Blue staining indicates the nuclei, and red staining represents caspase 3 expression. The images were obtained at 20x magnification.

Figure 8.

Western blot for caspase-9 expression in fibroblast in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated and UVA-treated (+ UVA) cells.

Figure 8.

Western blot for caspase-9 expression in fibroblast in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated and UVA-treated (+ UVA) cells.

Figure 9.

Immunofluorescence staining of p-Akt protein expression in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Blue staining indicates the nuclei, and red staining represents p-Akt protein expression.

Figure 9.

Immunofluorescence staining of p-Akt protein expression in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Blue staining indicates the nuclei, and red staining represents p-Akt protein expression.

Figure 10.

Immunofluorescence staining of mTOR protein expression in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Blue staining indicates the nuclei, and red staining represents mTOR protein expression. The images were obtained at 20x magnification.

Figure 10.

Immunofluorescence staining of mTOR protein expression in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Blue staining indicates the nuclei, and red staining represents mTOR protein expression. The images were obtained at 20x magnification.

Figure 11.

DNA biosynthesis in the fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. The mean values ± standard error (SEM) from the experiments, performed in triplicates. (*statistically significant difference p < 0.05 compared to control).

Figure 11.

DNA biosynthesis in the fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. The mean values ± standard error (SEM) from the experiments, performed in triplicates. (*statistically significant difference p < 0.05 compared to control).

Figure 12.

Immunofluorescence staining of PARP protein expression in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Blue staining indicates the nuclei, and red staining represents PARP protein expression. The images were obtained at 20x magnification.

Figure 12.

Immunofluorescence staining of PARP protein expression in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Blue staining indicates the nuclei, and red staining represents PARP protein expression. The images were obtained at 20x magnification.

Figure 13.

Immunofluorescence staining of Nrf2 protein expression in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1% and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Blue staining indicates the nuclei, and red staining represents Nrf2 protein expression. The images were obtained at 20x magnification.

Figure 13.

Immunofluorescence staining of Nrf2 protein expression in fibroblast cells in the presence of Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1% and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated (UVA -) and UVA-treated (UVA +) cells. Blue staining indicates the nuclei, and red staining represents Nrf2 protein expression. The images were obtained at 20x magnification.

Table 1.

The MTT test cell viability in fibroblast treated with Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated and UVA-treated (+ UVA) cells. The mean values, standard deviation (SD), standard error (SEM), and median (Me) from the 3 experiments. *statistically significant differences vs. control group, p < 0.05; **statistically significant differences vs. UVA only treated group.

Table 1.

The MTT test cell viability in fibroblast treated with Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% in non-UVA-treated and UVA-treated (+ UVA) cells. The mean values, standard deviation (SD), standard error (SEM), and median (Me) from the 3 experiments. *statistically significant differences vs. control group, p < 0.05; **statistically significant differences vs. UVA only treated group.

| Non - UVA treaded cells |

|---|

| |

I |

II |

III |

mean value |

% value |

SD |

SEM |

Me |

| Control |

0,794 |

0,789 |

0,74 |

0,774 |

100 |

0,029838 |

0,023 |

0,789 |

| AmO 0,05% |

0,74 |

0,685 |

0,542 |

0,655 |

84,711 |

0,102207 |

0,076 |

0,685 |

| AmO 0,1% |

0,78 |

0,76 |

0,709 |

0,749 |

96,856 |

0,036611 |

0,027 |

0,76 |

| AmO 0,15% |

0,804 |

0,731 |

0,721 |

0,752 |

97,157 |

0,04531 |

0,035 |

0,731 |

|

UVA - treatedcells

|

| UVA (+) |

0,449 |

0,413 |

0,425 |

0,429 |

55,426* |

0,01833 |

0,013 |

0,425 |

| AmO 0,05% |

0,564 |

0,496 |

0,51 |

0,523 |

67,614* |

0,035907 |

0,027 |

0,51 |

| AmO 0,1% |

0,461 |

0,636 |

0,625 |

0,574 |

74,160*/** |

0,098015 |

0,075 |

0,625 |

| AmO 0,15% |

0,51 |

0,672 |

0,554 |

0,578 |

74,763*/** |

0,083769 |

0,062 |

0,554 |

Table 2.

The dpm values - radioactive [methyl-3H]thymidine incorporation into DNA assay results in the presence of 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) in non-UVA-treated and UVA-treated cells. The mean values from the 3 experiments. *statistically significant differences vs. control group, p < 0.05.

Table 2.

The dpm values - radioactive [methyl-3H]thymidine incorporation into DNA assay results in the presence of 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% Amaranthus cruentus seed oil (AmO) in non-UVA-treated and UVA-treated cells. The mean values from the 3 experiments. *statistically significant differences vs. control group, p < 0.05.

| non UVA treaded cells |

|

|

|

| |

I |

II |

III |

I |

II |

III |

I |

II |

III |

mean value |

% value |

| Control |

4411 |

4316 |

4363 |

3991 |

3556 |

3639 |

4039 |

4058 |

4049 |

4046,8 |

100 |

| AmO 0,05% |

3951 |

3740 |

3709 |

3513 |

3556 |

3534 |

3977 |

3895 |

3936 |

3756,7 |

92,85 |

| AmO 0,1% |

3808 |

3564 |

3532 |

3862 |

4265 |

3910 |

3688 |

4064 |

3710 |

3822,5 |

94,47 |

| AmO 0,15% |

4000 |

4278 |

4292 |

3816 |

3622 |

3719 |

3732 |

4142 |

4098 |

3966,5 |

98,03 |

|

UVA treatedcells

|

|

|

|

| UVA (+) |

1937 |

1833 |

1944 |

2616 |

2253 |

2326 |

2371 |

2301 |

2336 |

2213 |

54,69* |

| AmO 0,05% |

2838 |

2828 |

2833 |

2838 |

2826 |

2832 |

2542 |

2525 |

2533 |

2732,7 |

67,54* |

| AmO 0,1% |

3421 |

3501 |

3461 |

3228 |

3214 |

3221 |

3622 |

3425 |

3462 |

3395 |

83,91* |

| AmO 0,15% |

3359 |

3342 |

3350 |

3950 |

4038 |

3994 |

3241 |

3175 |

3208 |

3517,4 |

86,93* |