1. Introduction

Sustainability has become a major framework for assessing the impact of present decisions on the consequences for future generations. However, the future is uncertain and it is it a challenge to forecast the forthcoming consequences of present decisions. So sustainability needs to be stated in terms of risks rather than in terms of certitudes [

1]. Moreover, there are evidences that that risk management and sustainability reporting in organizations promotes competitiveness and enhances an enterprise value [

2,

3]. In his much-applauded book “Against the Gods – The Remarkable Story of Risk” Peter L. Bernstein claims that risk management has existed for more than 2000 years as part of decision-making [

4]. However, modern risk management only started after World War II [

5]. The first academic book on risk management was published by Mehr and Hedges as late as 1963 [

6]. Risk management commenced by being a financial instrument to hedge companies against fluctuations related to interest rates, stock market returns, exchange rates, and the prices of raw materials or commodities. Risk management has over the years evolved to be a corporate framework to handle risk and uncertainty. It entered the realm of project management in 1987 when PMI (Project Management Institute) added risk management section to the PMBOK guide. [

7] Georges Dionne states that

“In general, a pure risk is a combination of the probability or frequency of an event and its consequences, which is usually negative.” [

5] This definition of risk is complying with well-known classifications of what is a risk. Oxford English Dictionary defines risk as:

“a chance or possibility of danger, loss, injury or other adverse consequences”. The ISO 31000 standard refers to risk as the

“effect of uncertainty on objectives.” Institute of Risk Management (IRM) forwards this definition:

„Risk is the combination of the probability of an event and its consequence.” HM Treasury in the UK refers to risk as:

„uncertainty of outcome, within a range of exposure, arising from a combination of the impact and the probability of potential events.” Finally, from the Institute of Internal Auditors we have

“risk is measured in terms of consequences and likelihood.”. [

8] Brought together we can assume that a common formulation of risk is:

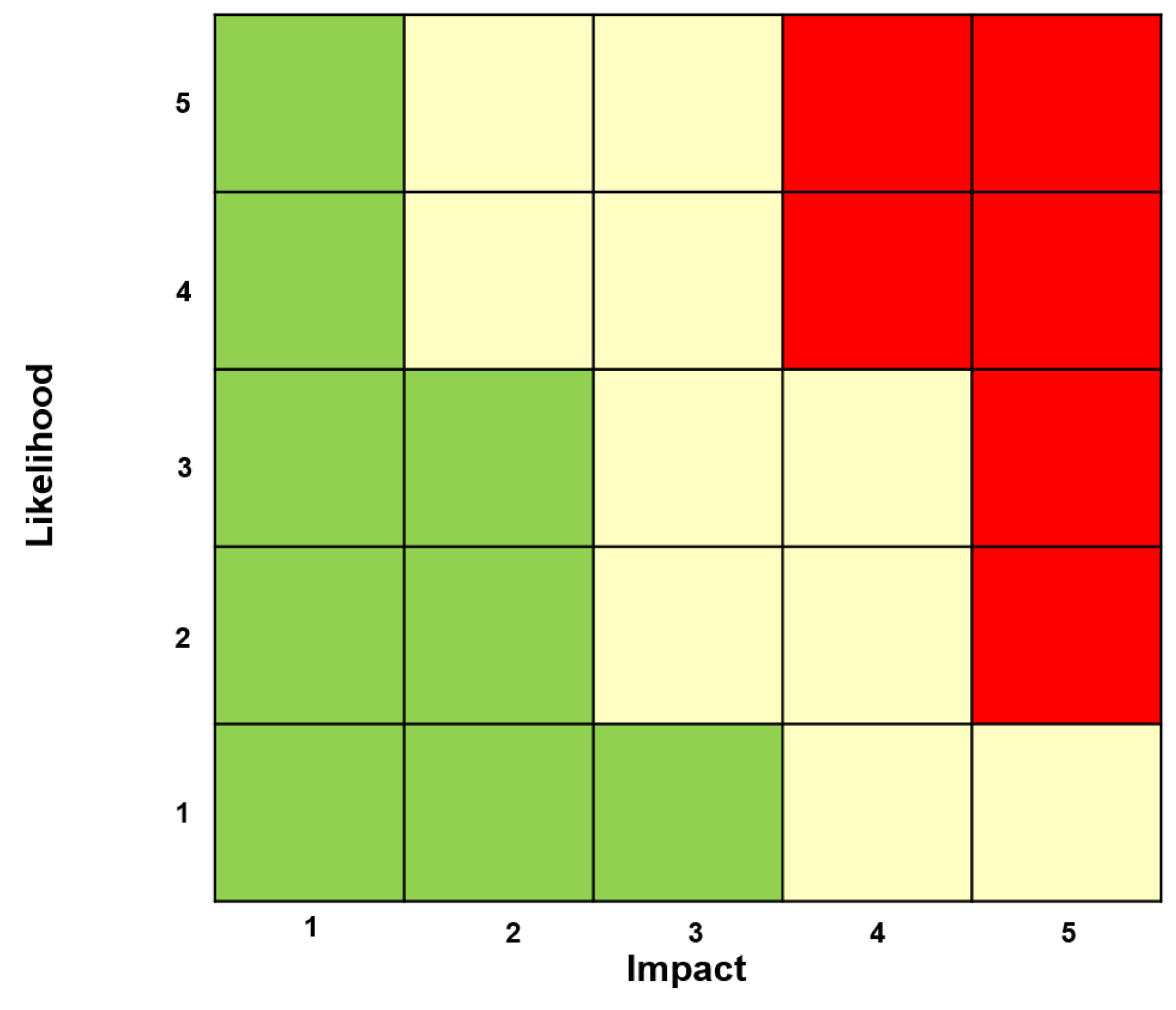

Risk is the combination of the probability of an event and its consequence. Risk = Likelihood of event × Impact of event.

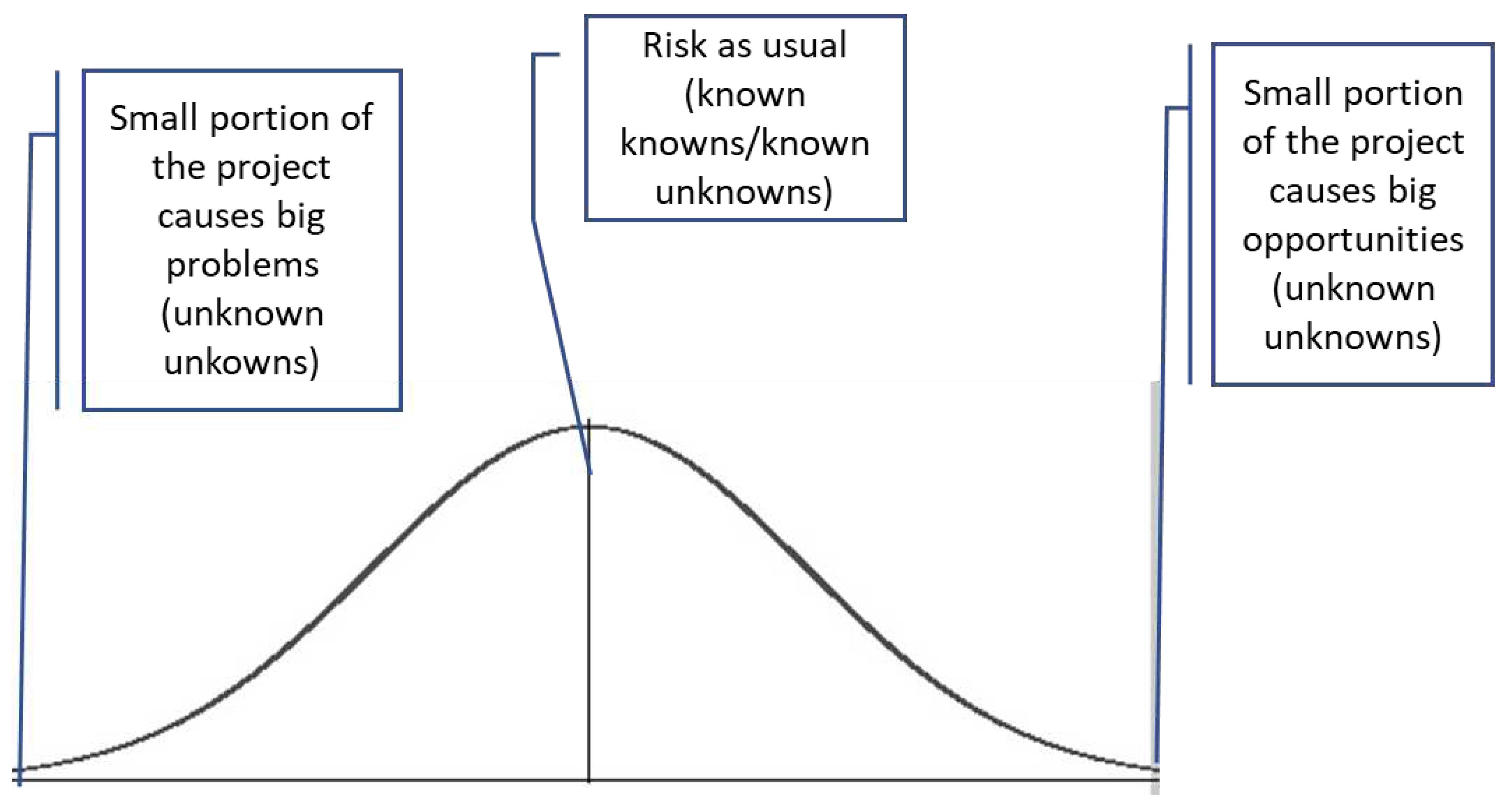

Here we have an issue. If risk is a product of likelihood and impact, e.g. on a scale from 1-5, a risk matrix for some hypothetical project could look like shown in

Figure 1.

The problem here is that a high-impact and low likelihood risk event might be assumed to be of limited significance in the general project risk profile.

Black swans and the Vadlaheidi tunnel project

A paradigm called the black swan risk factor has recently emerged and is currently widely used and the work presented in this paper is inspired by this. The term has become widely recognized because of the book The Black Swan by Nassim Taleb [

10]. The financial crash in 2008 is one of the most recent and well-known black swan events. The effect of the crash was catastrophic and global, and only a few outliers were able to predict it happening. And although somewhat disputed, the COVID-19 pandemic [

11] and the war in Ukraine may be considered black swans. It should be noted that the vocabulary of this type of risk management has been expanded in the last years by using colorful naming from the animal kingdom. Some risk analysts would name COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine as a Grey Rhino and some stock crash as Dragon Kings [

12]. However, in the present work, risk events that are governed by power or Poisson distributions, rather than the normal distribution are called black swans or fat tail events, for the sake of simplifying.

To prepare for the postulation of this paper the authors like to present the Vadlaheidi tunnel project (here after we use the nam Vadlaheidi project for simplicity). This project is a 7.5 km mountain tunnel at the north coast of Iceland connecting the city of Akureyri with Fnjoskadalur. The case presents some interesting shortcomings of the traditional definition of risk.

The initial business model for the project was presented in 2002. It was assumed that the construction and the operation of the tunnel would be a private-public enterprise with high feasibility and limited technical difficulties. Road tolls would recover all investment costs within 20 years plus a macroeconomic gain of 8%. Then came the financial crisis in 2008. Market financing folded as a consequence. The arrangement was modified and the Icelandic government was forced to guarantee a loan to make the construction possible.

When the construction commenced the project soon hit some serious unforeseen problems. In the beginning of 2014, a major hot water leak was detected, due to unexpected geothermal activity in the mountain. As a consequence, drilling was impossible due to heat and steam. To be able to proceed with the project, the contractor had to move the equipment to the other side of the mountain and continue drilling from there.

In April 2015, a major unexpected leak of cold water was discovered at the new drilling site. The water completely floated the tunnel causing serious problems. A famous news clip from this period shows a TV reporter rowing a boat inside the tunnel to investigate and describe the conditions.

The tunnel was scheduled to be ready for traffic in 2016 (the initial plan assumed 2011). However, it was only operative in December 2018. The cost overrun in 2017 was estimated at 44%. However, it should be noted that in the presented cost overrun number, the cost of finance was not included and the real total cost overrun is thus much higher. In July 2019, it was reported that the income from the tolls was 35–40% less than expected. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a major breach in traffic volume in 2020, as the Icelandic tourist industry collapsed and local people were encouraged to limit their mobility as much as possible.

In a nutshell, the drastic events that troubled the Vadlaheidi project are:

An unexpected international financial crisis ruined the initial business model transferring the financial risk to the public.

Unexpected geothermal activity inside the tunnel prevented drilling the tunnel with negative consequences for the schedule and the budget.

An unexpected cold-water leak inside the tunnel delayed significantly excavating the tunnel with negative consequences for the schedule and the budget.

The unexpected global pandemic reduced the tunnel traffic and the revenue stream was severely reduced [

13]

In short, the project was hit by four highly low-probability but high-impact events with serious consequences. It can be argued that the hypothetical risk matrix in

Figure 1 would not capture any of these risk events due to how improbable they are. Some might recall the famous press conference held on February 12

th, 2002 by then the US Secretary of Defence, Donald Rumsfeld. During this conference, Mr. Rumsfeld stated:

But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult one [

14]. This comment was actually forwarded to justify the ill-conceived claims that Iraq had “weapons of mass destruction”. However, these words have become legendary as they exemplify risks that come from scenarios that are so unexpected that they would not be considered.

2. The VUCA world

The unknown-unknowns and black swans in fact embody a situation referred to as the VUCA world. The VUCA world refers to the volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous situation that challenges businesses and societies. We have for instance several dubious political leaders that do not hesitate to break with rules and protocols, shaking the norms of the diplomatic and economic world. Former president Trump is accused of being indifferent - even encouraging - when the United States Capitol was mobbed by his supporters in January 2021 [

15]. Hungary, the country led by Viktor Orbán, has been declared by the EU not being a full democracy [

16]. Boris Johnson was forced to resign in 2022 when proven to tell outright lies repeatedly. [

17] Vladimir Putin wages an ill-conceived war in Ukraine in 2022 with terrible humanitarian consequences and with destabilizing effects on worldwide economic balances in magnitudes not fully known at the time of this writing [

18].

Even in less political contexts, the manageability that was once associated with planning and forecasting and the continuity of established actors can no longer be relied upon. When the giant container ship, Ever Given, blocked passage through the Suez Canal in March 2021 the global supply chain was thrown into chaos [

19]. Much hyped financial ideas like the Bitcoin cryptocurrency have turned out to be highly volatile. From November 2021 to November 2022 Bitcoin lost more than 70% of its value [

20]. And what impact do new and disruptive technologies like automation and quantum computing driven by artificial intelligence have on business and daily lives? Global demographics, migration, trade strategies, disruptive technologies, unconventional politicians, cultural uprisings (e.g. MeToo) and the encounter of climate change [

21]; all of this create an acute challenge for management in foreseeing the future and orchestrating preventive measures in the attempt to gain control.

Bennett and Lemoine call this “the VUCA world” employing an acronym for the volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity that exemplifies the risky world we inhabit. The connection between risk and sustainability are e.g. documented by [

3,

22].

Figure 2.

The unknown unknowns lie in the tails.

Figure 2.

The unknown unknowns lie in the tails.

Another noteworthy paradigm in the context of this study is the term “projectification”. Projectification is a well-known concept to describe the diffusion of projects as a form of organizing in all sectors of the economy [

23]. Schoper et al [

24] concluded that more than one third of an economy in a developed country can be traced to projects and this progression is escalating. Arguably, the management of risk in projects is more current than ever due to the significance of this management form and the uncertainty of the VUCA world.

The authors theory is that the conventional definition of risk as being the likelihood of event multiplied by the impact of the event - can be problematic when assessing project risk in the VUCA world. The reason is on one hand the escalation of unlikely events that cause big problems and on the other hand the limitations of the human mind to assesses probabilities.

2.1. The problem of subjective probability assessment

In project management, likelihood of event (probability) is acquired either by a subjective estimate or it is based on empirical evidences. Firstly, let’s discuss what is called the subjective probability of an event. People make such judgments all the time, not only to estimate risk but to cope with their daily lives. We look out of the window prior to walking the dog or heading for the golf course to estimate if it will rain, we speculate on sport event results, who will win the election and so on. Both these approaches, using subjective estimates or empirical evidences, are valid and current per se. However, they come with shortcomings. Group of experts assessing risk may be prone to cognitive biases often referred to as “planning fallacies”. Planning fallacies are described in the seminal work of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky [

25] and have been proven to affect judgments and decisions. The planning fallacy, see for instance [

26,

27], stems from agents taking an inside view focusing on the constituents of the specific planned action rather than on the outcomes of similar actions already completed. Thus, for example, the estimated costs put forward by cities competing to hold the Olympic Games have consistently been underestimated; yet, every four years these errors are repeated [

28]. Some interesting psychological issues may affect how the estimating and planning plays out. The backbone of the conventional approach in risk assessment is the attempt to predict the likelihood of a risk event to happen. The estimate of subjective probabilities is in particular interesting in context of this paper and the VUCA world. The reason is that subjective probability judgments are based on data of limited validity which are processed through mental heuristic rules. Daniel Kahneman calls these heuristics rules “mental shotguns” to answer complex questions [

29]. The application of these mental rules is often very useful but the drawback is that heuristics can lead to biased probability assessments. In particular, three types of heuristic rules are applied by people to estimate subjective probabilities and they are well worth mentioning in the context of risk identification. These rules are called Representativeness, Availability and Anchoring and adjustment.

2.2. Representativeness heuristic

The representativeness heuristic may work in such a way that when trying to assess how likely a certain event is, we ignore base rate frequencies and sample sizes and opt instead for what we find a fit to our question. A well-known example of this is when a group of people were asked how likely it is that two hospitals, a large one and a small one, report that more than 60% of children born on any given day are boys. Most people estimate that the odds of such a report is even for both hospitals, thus ignoring the sample size (the small hospital has larger variation in gender birth ratios). Another example is when a description of an individual fits a certain occupation, for instance a librarian. If the description fits the stereotypic description of a librarian (shy, withdrawn, helpful, little interest in people, detailed) people assume the person belonging to this rather rare occupation, ignoring the prior probability of the outcome (the number of librarians in US is about 160.000 but the number of lawyers is about 1,3 million (

www.ala.org and

www.clio.com)). This can lead to serious errors as similarities do not necessary represent probabilities of occurrence. People also expect that random sequences are likely to have a certain pattern. When tossing a coin, people consider the sequence H-T-H-T-T-H more likely to happen than H-H-H-T-T-T although statistically, both sequences are evenly likely to happen. This is sometimes referred to as the gambler’s fallacy (luck must be on my side next game as I have been so unlucky until now). People also tend to ignore how outliers work. For instance, that a record sales month will be followed by equally successful month, or even better. In other words, that contemporary changes actually represent future conditions. But outliers usually do not work like that and the most likely outcome for the sales is that the they will regress to the mean (the normal condition). The representativeness heuristic and the cognitive biases incurred can deprive people from assessing correctly the probabilities of a risk event.

2.3. Availability heuristics

Another interesting heuristic leading to flawed probability assessment is he availability heuristics. The availability heuristic mechanism leads people to confuse the probability of an event with how easily it can be brought to mind. This can lead to biased judgment of the probability of occurrence. A risk assessor that hears about a terrorist attack in the news the morning prior to a risk assessment seminar might be affected by the images that occupies his/her mind. However, an event that can be easily imagined is not necessarily an event that is particularly likely to happen. A well-known example of the availability heuristic is the fear of flying. Airplane accidents are very rare but when they happen they are extensively covered in the news. Pictures of people stuck in an air cabin waiting helplessly to meet their destiny are easily brought to mind. The probability of dying in an air crash are extremely low and in fact less than dying in a car crash [

30].

2.4. Anchoring and adjustment heuristic

The last heuristic presented here to portray the challenges of assigning probabilities to risk events is the anchoring and adjustment heuristic. This heuristic is well known from negotiation techniques. A well-known trick when trying to get a low price is to make the first move and name a low number, in the hope that the proposed number will serve as an anchor that will be adjusted in the negotiation process. Anchoring also plays a role when the decision is based on incomplete computations. The human mind is actually not very good at computations. It is not easy to multiply 1x2x3x4x5x6x7x8 without a calculator. Interestingly, unaided multiplication of 8x7x6x5x4x3x2x1 gives a totally different estimate as studies show. The reason is the different arrangement of the numbers. People note the first numbers in the row and attempt to calculate in their minds the product, but wind-up in guessing. As a rule, the row with the descending sequence produces higher estimates than the ascending sequence. In the original experiment the median of the ascending estimates was 512 while the median of the descending was 2.250 (by the way, the correct answer is 40.320). An example of other biases under this category is the typical overestimation of the probability of conjunctive events as people tend to anchor the probability of a single event and make insufficient adjustment consequently. For instance, a system that has seven dependent elements, meaning that they all have to be functional so the system can operate. Each element has p=0,9 to be operational at any given moment. Studies show that many would consider the probability of functional system to be 0,9. The correct probability is only p=0,48 (0,9 in the power of seven).

The text above is based on the inspiring work of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky [

29]. Daniel Kahneman received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences 2002 for his ground-breaking work in applying psychological insights to economic theory, particularly in the areas of judgment and decision-making under uncertainty. So, in spite of the many wonderful attributes of the human mind, estimating probabilities is not one of them.

2.5. Assessing probability with empirical evidences

Empirical evidence also come with some well-known downsides in risk management. It is often assumed that the likelihood of outcomes is normally distributed, pointing the risk focus towards the highest frequency outcomes - the most probable outcomes (the mean). However, as mentioned before, prolific scholars and thinkers accentuate that the most impressive risks are not found in the averages but in the tails of the normal distribution. That is to say, the biggest challenges with the direst consequences are low probability high impact outliers, often called black swans. The term became famous because of the book, The Black Swan, by Nassim Taleb [

10]. World War I, the rise of the Internet and 9/11 have been identified as examples of black swan events. The financial crash in 2008 is one of the most recent and well-known black swan events. The effect of the crash was catastrophic and global, and only a few outliers were able to predict it happening. And although somewhat disputed, the COVID-19 pandemic [

11] and the war in Ukraine may be considered black swans (Financial Times, 2022). It should be noted that the vocabulary of risk management has been augmented the last year by using colorful naming’s from the animal kingdom. For instance some risk analysts would name COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine as a Grey Rhino´s and some stock crash’s as Dragon Kings [

12]. However, in this work risk events that are governed by power or Poisson distributions, rather than the normal distribution, are called black swans or fat tail events for the sake of simplifying.

Taleb argued that because black swan events are impossible to predict due to their rarity, yet they have catastrophic consequences, it is important for people to always assume a black swan event is a possibility, whatever it may be, and to try to plan accordingly [

31]. Moreover, in the VUCA world, the speedy and complex environment we live in, empirical evidence may be difficult to enquire and may even be rapidly redundant. Fresh management concepts like Agile and Beyond Budgeting are specifically designed to overcome the challenges of rigid up-front planning in our turbulent world [

32]. Lastly, finding a suitable reference class can also be a challenge. An example of this is deciding the probability of a programmer getting a job within a certain period. Should the reference class include only unemployed programmers or should it contain other attributes like gender, age, health, address, etc. [

33]?

The authors therefore like to introduce the VUCA concept as an additional platform to assess project risks with an emphasis on isolating low-frequency but high-impact risk events by a stepwise procedure.

3. The VUCA meter development

The authors therefore have worked on the idea to compile a methodology that would enhance the risk assessment doctrine by using the VUCA concept as the platform. Early in the process the methodology was coined as “VUCA meter” [

34,

35]. This study bases its definition of the VUCA components on Bennett and Lemoine, who use VUCA to describe the rapidly changing environment in which modern businesses must navigate. They warn against conflating the distinct terms of the VUCA framework when one is faced with the unpredictability of VUCA situations. Despite the myriad of popular articles, they claim, “

there is a lack of information regarding just what it is that leaders should do in order to confront […] these conditions” [

36]. Properly identifying them, they claim, is crucial to take appropriate action, as they each

“require their own separate and unique responses. […] Failure to use the right label will lead to a misallocation of what could be considerable corporate resources” [

36].

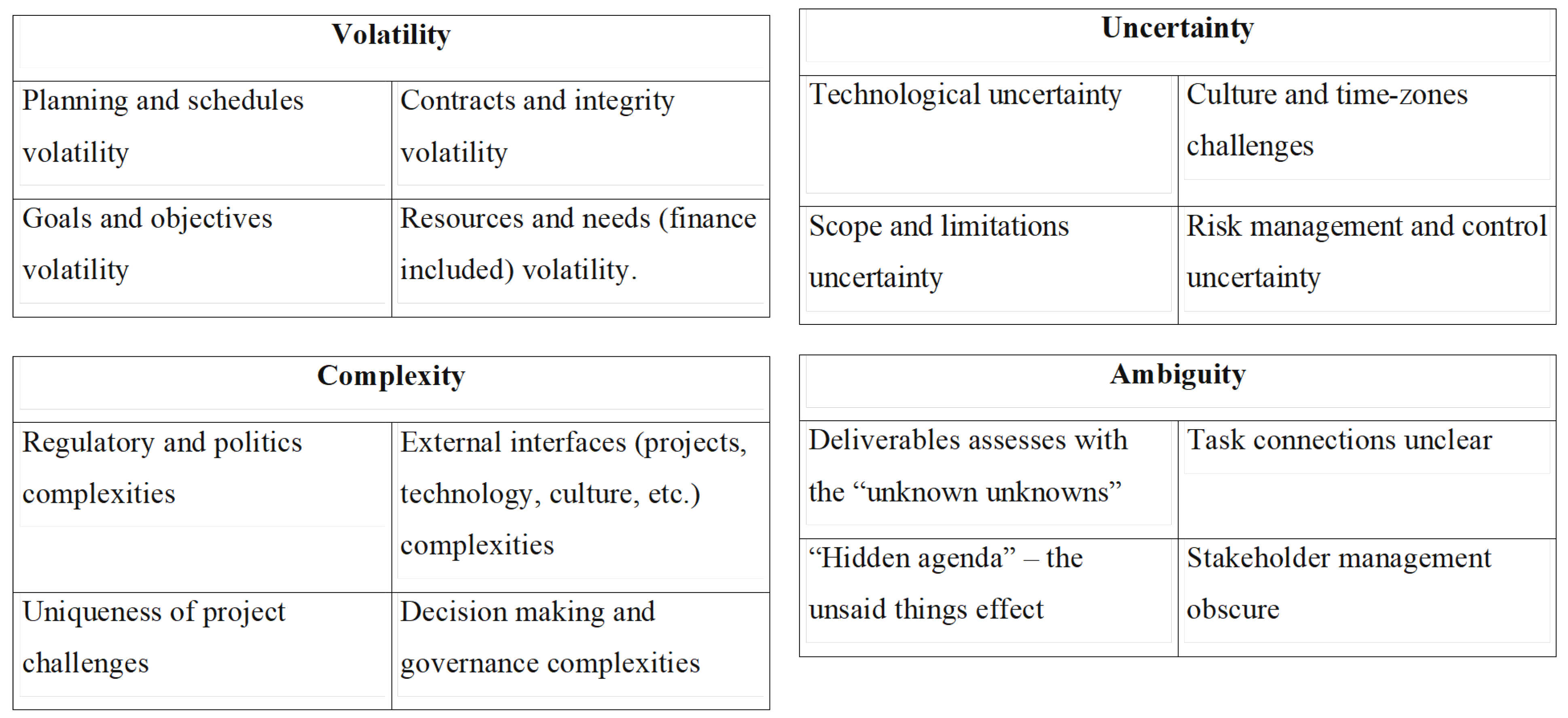

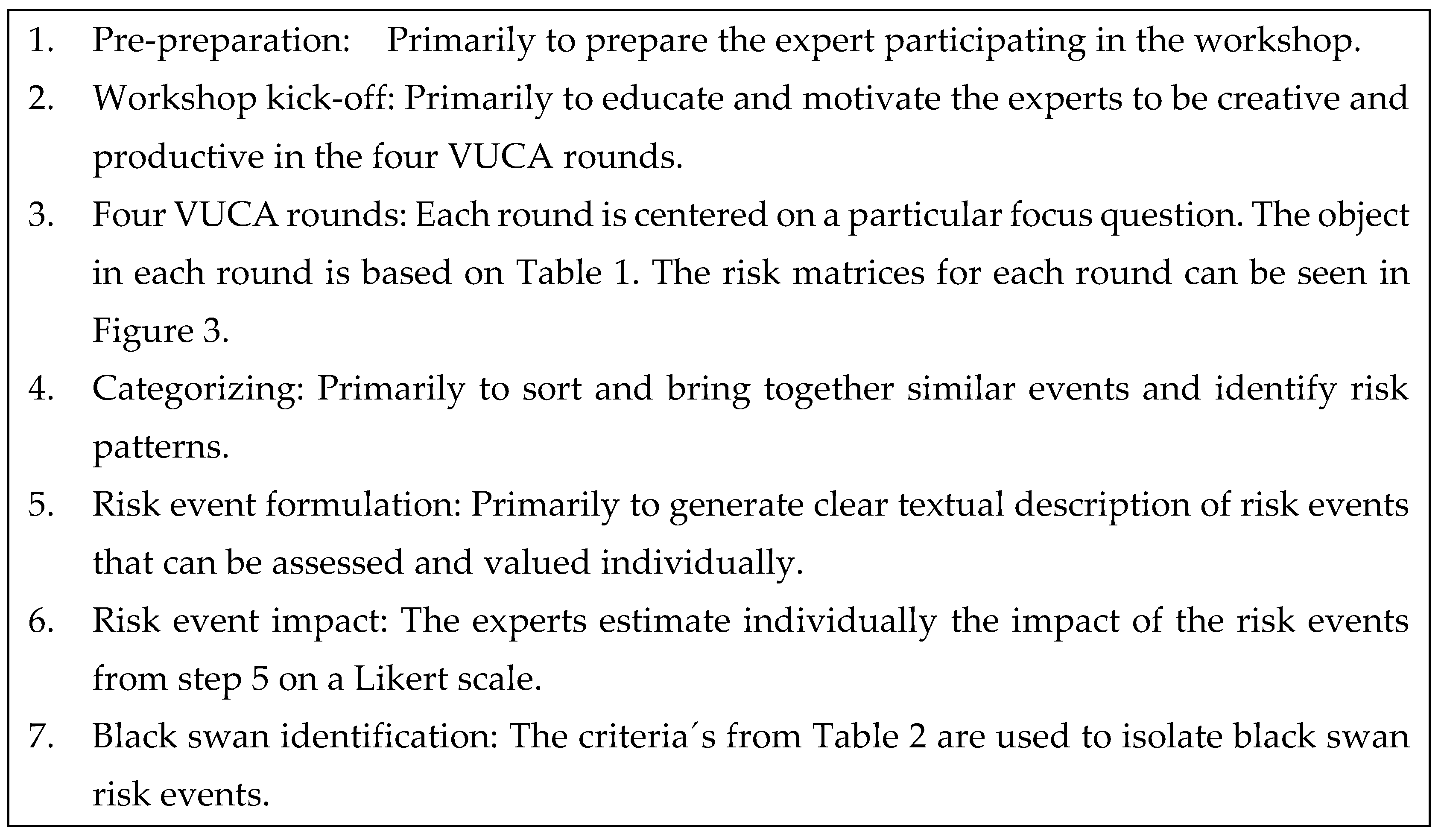

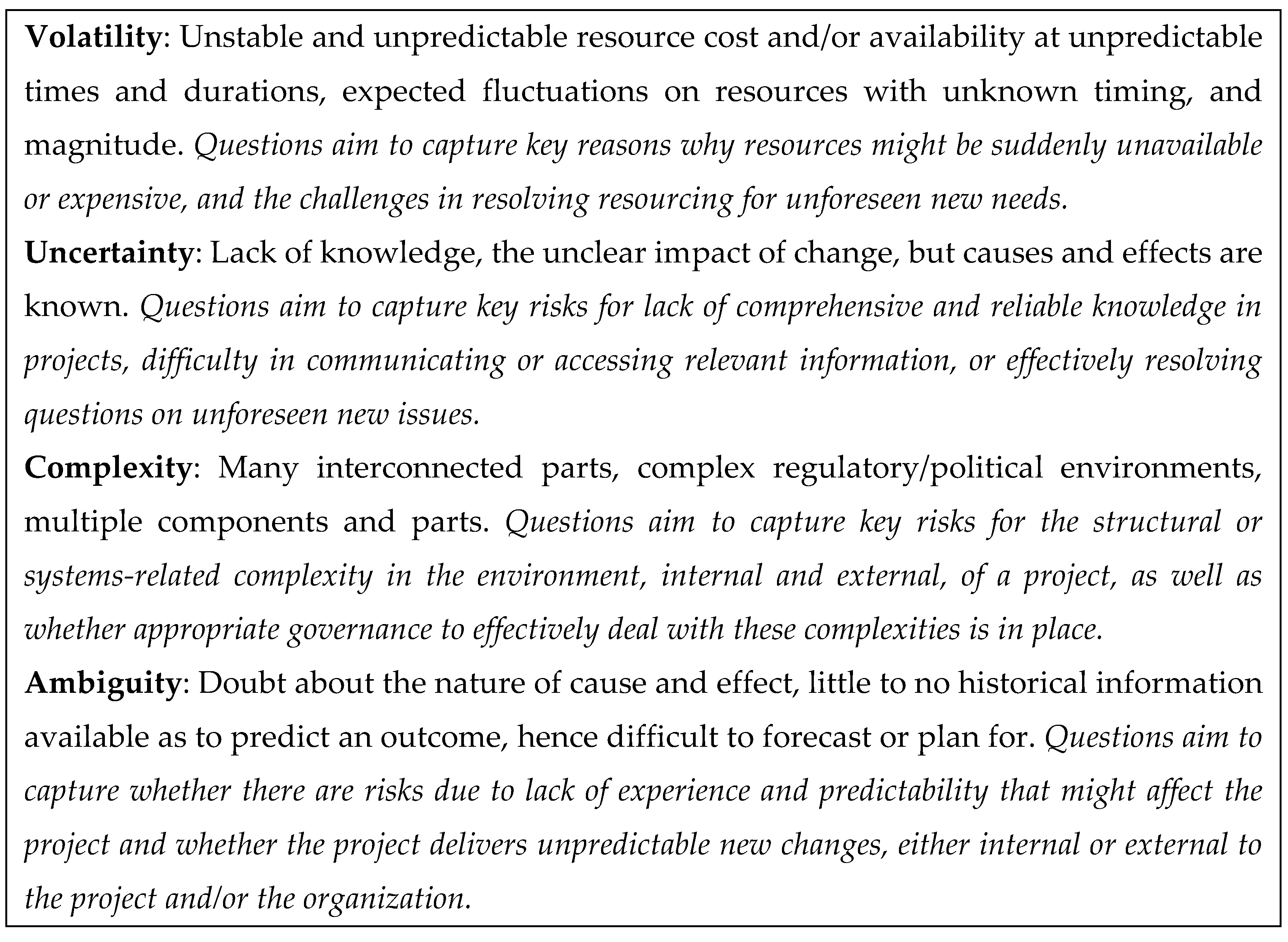

All things considered, Bennett and Lemoine provided the authors with the semantics needed to form a textual assessment approach. Based on this, a definition of each of the VUCA terms is summarized in

Table 1 and the relevant questions in the context of project management formed [

34].

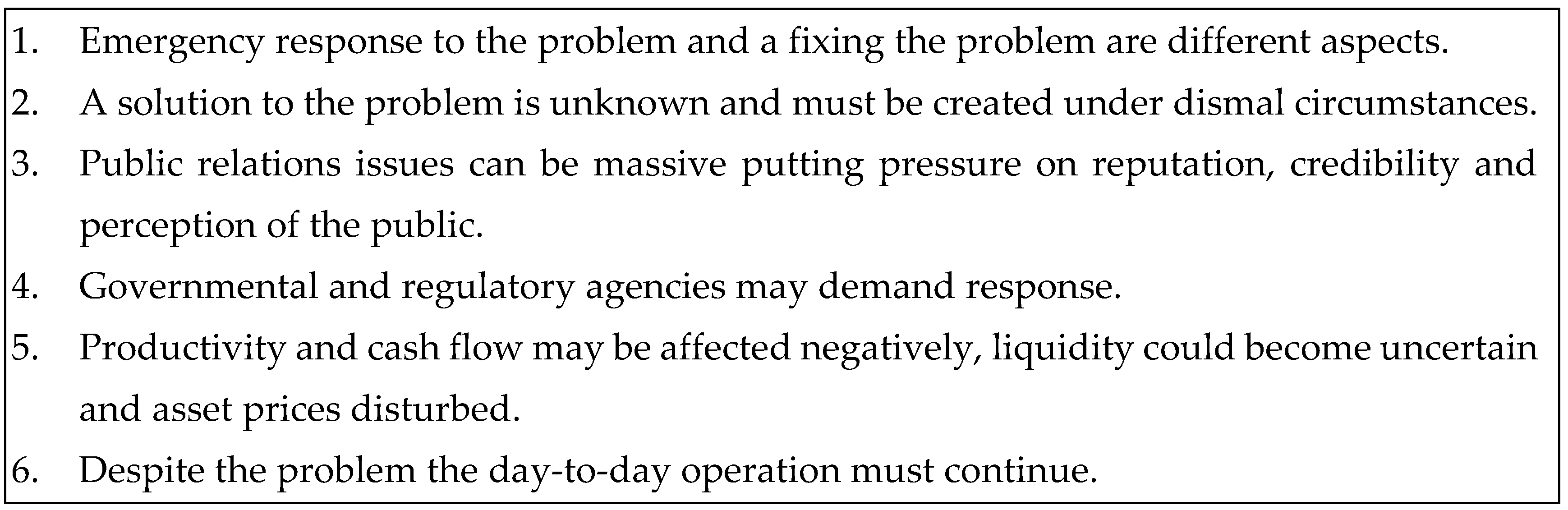

The purpose of the VUCA meter is to detect and expose fat tail risk events referred to as black swans. Nancy Green provided a passable description of the characteristics of a risk event that might surpass the conventional risk assessment procedure based on the work of Nassim Taleb, see

Table 2 [

37].

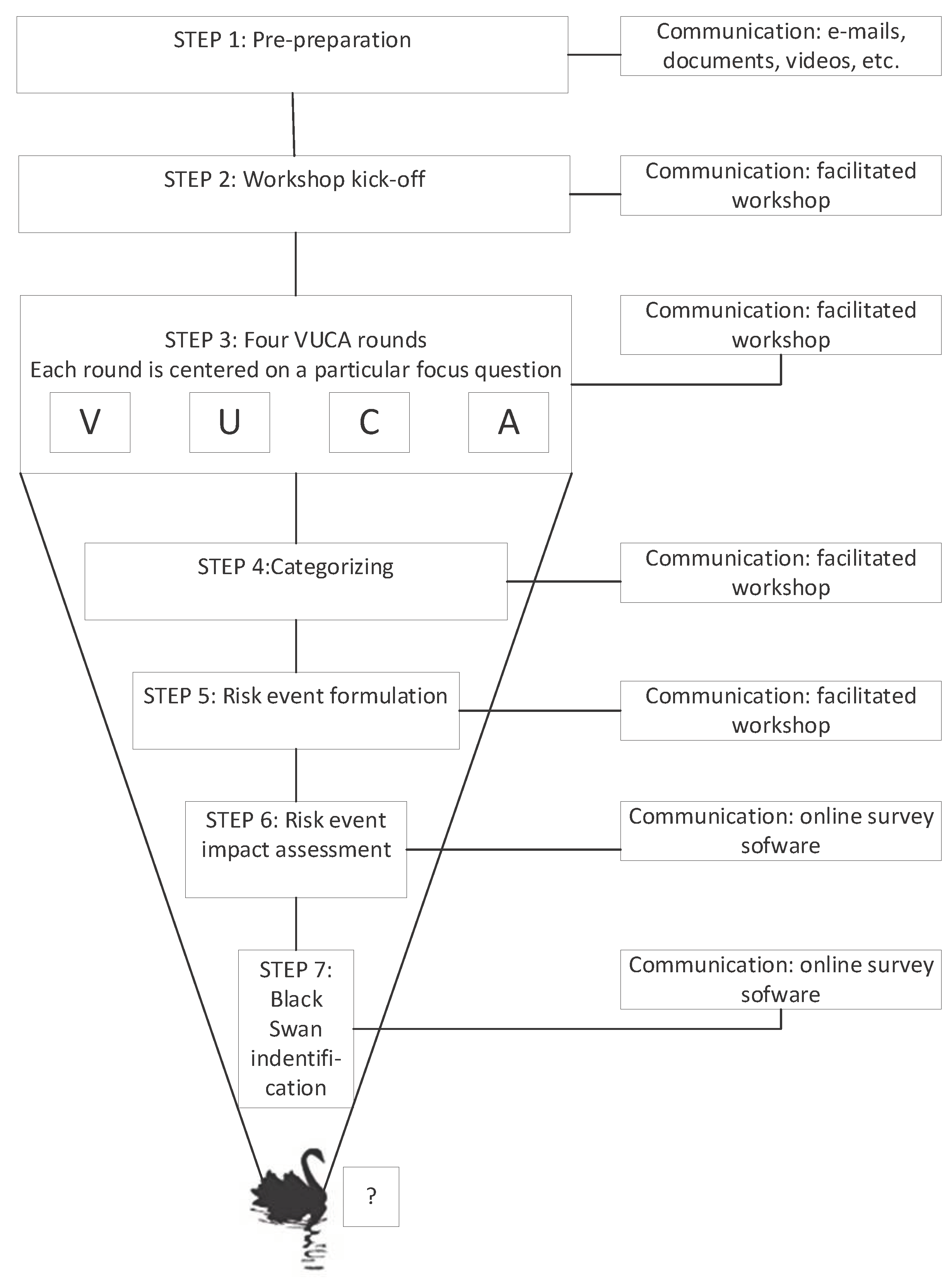

The semantics of the Bennet and Lemoine study on the characteristics of VUCA provided the authors with means to develop the sections of the VUCA risk identification meter. Each section of the meter must be addressed individually since they require a unique response. Based on this, seven sequential steps were identified as shown in

Table 3:

Of particular interest are the four VUCA rounds, see

Figure 3. The VUCA rounds are structured brain storm sessions. The rounds are carefully facilitated to enhance creative thinking.

It is noteworthy that the VUCA procedure assumes that steps 2-5 are physical collective workshops, carefully planned and facilitated. Steps 6 and 7 are on the other hand individual assessments were the experts evaluate the outcomes from the previous steps on pre-designed scales. These steps can be carried out online if applicable.

4. Discussions and conclusion

The connection between risk and sustainability is well known [

1,

2,

3]. The supplement of risk assessment in decision making migh easily lead to more sustainable future. Risk was inserted into the domain of project management as late as 1987 when PMI introduced a risk chapter in its main doctrine, the PMBOK. Since then, risk and uncertainty have gradually been accepted as a major dogma in the discipline of project management. The aspiration to hedge projects against the unexpected by assessing risk is currently on pair with scheduling and budgeting. The significance of risk management is further enveloped by the projectification of the society. Schoper et al. (2018) argues that a third of the economy can be traced to project work. In Germany the share of project work was 29% in 2009 but was projected to be over 41% in 2019. It can be argued that the escalation of projects and project management is a response to the VUCA world. The volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous business environment managers and decision makers must cope with.

Arguably, the most sensitive step of the risk management procedure is the first step, the assessment of the root causes to later troubles. If a risk analyst fails to identify events that can put the project objectives into jeopardize at the initial stages, the realization of such an event later in the project lifecycle can be difficult and costly to rectify. In this study the authors point out that the basic axioms of risk analysis are the function of probability and impact of a risk event. The authors do not oppose to this approach per se. However, they call attention to interesting psychological theories forwarded initially by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in the seventies, but have now become a mainstream concept to understand for instance cost overruns, late budgets, scope creeps, etc. The Prospect Theory [

25] for instance claims that due to cognitive biases people have difficulties assessing probabilities, chance, likelihood or whatever terms we use to describe a certain frequency of a possible outcome. This is not a statement to undermine the traditional approach. The authors are on the contrary a firm believer on using for instance empirical data, reference class forecasting, simulations, risk models, etc. However, the problem described is this conceptual article can be instrumental in assessing project risk as it is mathematically the most important gradient for quantifying the qualitative assessment. Moreover, the most probable risk events are not equal to severity of the risk event that further underpins the theory that risk analysts should be on the hunt for fat tail events.

The authors theory is that the conventional definition of risk;

can be problematic assessing project risk in the VUCA world. In this work we have presented firstly; why it is problematic and, secondly how the accepted process can be, not be replaced, but augmented by the VUCA meter. The VUCA meter is a normative approach aimed at isolating low frequency but high-impact events that could bring dilemma to the project and the future.

The VUCA meter has hitherto been tested rigorously on nine projects. The prototype was tested on five large technical installations. The first version was used to supplement risk assessment on a large infrastructure project in the planning phase. This was followed by using the VUCA meter to identify risk in three very different projects; one humanitarian program due to the war in Ukraine, one a Waste-to-energy plant and lastly a geo-thermal power plant. All assessments were carried out and facilitated by professional project managers. Furthermore, in two of the assessments the VUCA meter was benchmarked against the conventional risk assessment procedure. An accurate description of the VUCA meter and the application of it awaits another publication. It can though be stated that there are clear evidences that the meter is a valuable new instrument that can be placed with other risk identification means in the project managers toolbox for the sake of sustainable world.

References

- Krysiak, F.C. Risk management as a tool for sustainability. Journal of business ethics 2009, 85, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shad, M.K.; Lai, F.-W.; Fatt, C.L.; Klemeš, J.J.; Bokhari, A. Integrating sustainability reporting into enterprise risk management and its relationship with business performance: A conceptual framework. Journal of Cleaner production 2019, 208, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, G. Integrating sustainability into project risk management. in Global Business Expansion: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global, 2018; pp. 330–352. [Google Scholar]

-

Bernstein, Peter, Against the Gods - The remarkable story of risk; Wiley: New York, 1996.

- Dionne, G. Risk management: History, definition, and critique. Risk management and insurance review 2013, 16, 147–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Mehr, R. I. R. A. Risk management in the business enterprise.. RD Irwin, 1963.

- Stretton, A. A short history of modern project management. PM World Today 2007, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkin, P. Fundamentals of risk management: understanding, evaluating and implementing effective risk management; Kogan Page Publishers, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, E.W.; Gray, C.F. Project management: The managerial process. McGraw-Hill Education 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, N. The Black Swan: Second Edition: The Impact of the Highly Improbable; Random House, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, F.S.; Qadri, H.; Mohammed, S. COVID-19 in the era of artificial intelligence: a black swan event? Journal of Medical Artificial Intelligence 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, N. Doom -The politics of catastrophe. Penguin, 2022.

- “Vadlaheidi - sagan.” https://www.vadlaheidi.is/is/sagan.

- Pozen, D.E. Deep secrecy. Stanford law review 2010, 257–339. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman, E. The th Report. Simon and Schuster, 2022. 6 January.

- Batory, A. More power, less support: The Fidesz government and the coronavirus pandemic in Hungary. Government and Opposition 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, D. Would I lie to you?’: Boris Johnson and Lying in the House of Commons. The Political Quarterly 2022, 93, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welfens, P.J. Beginnings of the Russo-Ukrainian War. in Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: Economic Challenges, Embargo Issues and a New Global Economic Order; Springer, 2023; pp. 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.M.Y.; Wong, E.Y.C. Suez Canal blockage: an analysis of legal impact, risks and liabilities to the global supply chain. MATEC Web of Conferences - EDP Sciences 2021, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfaoui, R.; Gozgor, G.; Goodell, J.W. Impact of Russia-Ukraine war attention on cryptocurrency: Evidence from quantile dependence analysis. Finance Research Letters 2023, 52, 103365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friðgeirsson, Þ.V.; Steindórsdóttir, F.D. A cross-impact analysis of eight economic parameters in Iceland in the context of Arctic climate change. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Silvius, G. Sustainability as a new school of thought in project management. Journal of cleaner production 2017, 166, 1479–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midler, C. Projectification of the firm: The Renault case. SJM 1995, 11, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoper, Y.G.; Wald, A.; Ingason, H.T.; Fridgeirsson, T.V. Projectification in Western economies: A comparative study of Germany, Norway and Iceland. International Journal of Project Management 2018, 361, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovallo, D.; Kahneman, D. Delusions of success. Harvard business review 2003, 81, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buehler, R.; Griffin, D.; Peetz, J. The planning fallacy: Cognitive, motivational, and social origins. In Advances in experimental social psychology. In Advances in experimental social psychology; Academic Press, 2010; Volume 43, pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B.; Stewart, A.; Budzier, A. The Oxford Olympics Study 2016: Cost and cost overrun at the games. arXiv 2016, arXiv:arXiv:1607.04484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. 2011.

- Howard, W.A.; Murphy, S.M.; Clarke, J.C. The nature and treatment of fear of flying: A controlled investigation. Behavior Therapy 1983, 14, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, P.; Taleb, N. Tail risk of contagious diseases. Nature Physics 2020, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, S. Reinventing Management-How Agile an Beyond Budgeting have converged Management. Forbes, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2018/03/27/reinventing-management-how-agile-and-beyond-budgeting-have-converged/?sh=19e6967b4c58. /.

- Goodwin, P.; Wright, G. Decision analysis for management judgment, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fridgeirsson, T.V.; Ingason, H.T.; Jonasson, H.I.; Kristjansdottir, B.H. The VUCAlity of Projects: A New Approach to Assess a Project Risk in a Complex World. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridgeirsson, T.V.; Ingason, H.T.; Björnsdottir, S.H.; Gunnarsdottir, A.Y. Can the ‘VUCA Meter’ Augment the Traditional Project Risk Identification Process? A Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.; Lemoine, G. What a difference a word makes: Understanding threats to performance in a VUCA world. Business Horizons 2014, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, N. Keys to success in managing a black swan event. AON Corporation, 2015, [Online]. Available: http://www.aon.com/attachments/risk-services/Manage_Black_Swan_Even_Whitepaper_31811.pdf. /.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).