Submitted:

16 May 2023

Posted:

17 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Gene expression profiling of holoclones from oral mucosa, limbus and conjunctiva

2.2. PITX2 mRNA is overexpressed in oral mucosa compared to ocular surface tissues

2.3. Analysis of Pitx2 isoforms

2.4. Validation of the results by in situ hybridization (ISH)

2.5. Validation of the results at protein level

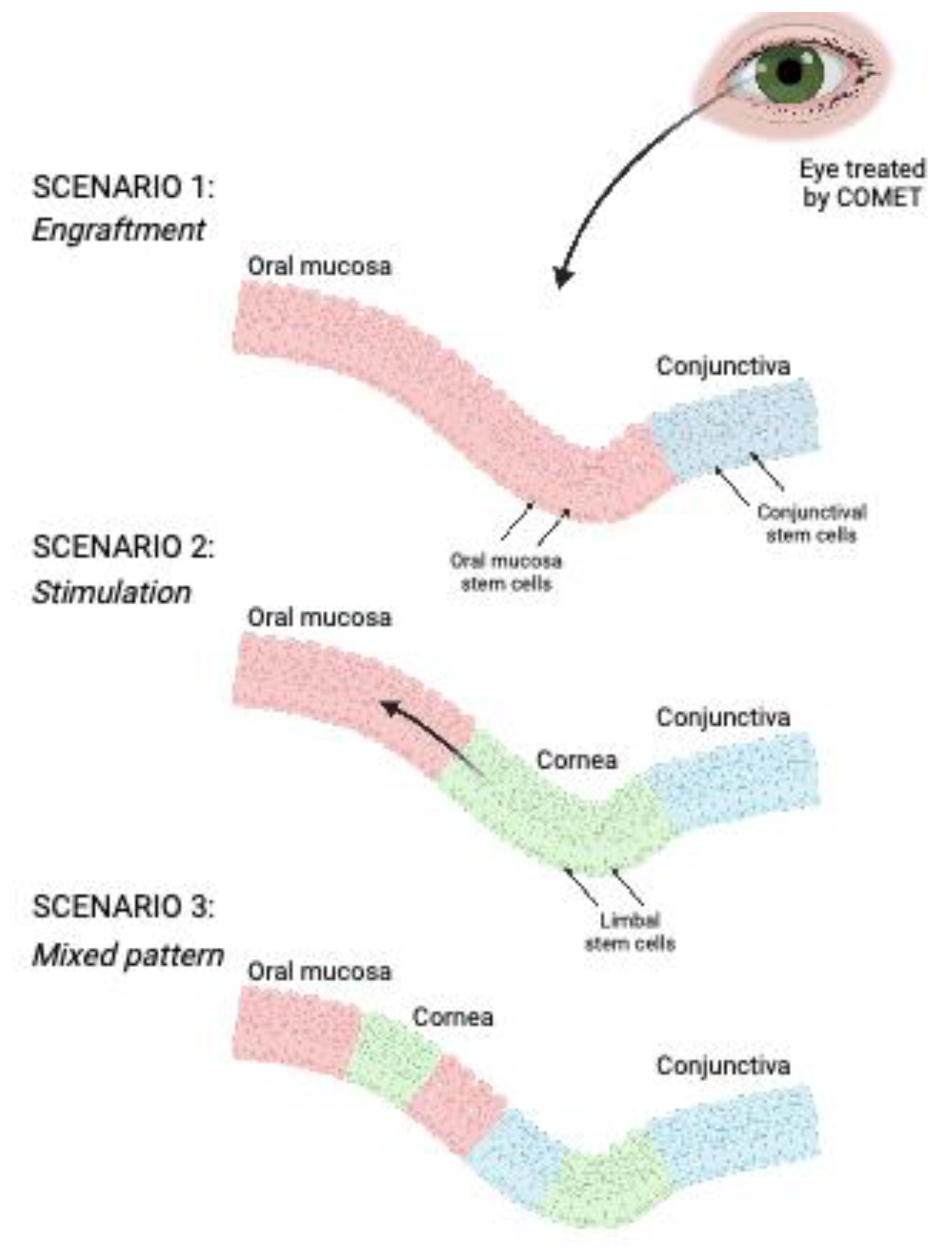

2.6. Phenotypic characterization of the patient after COMET

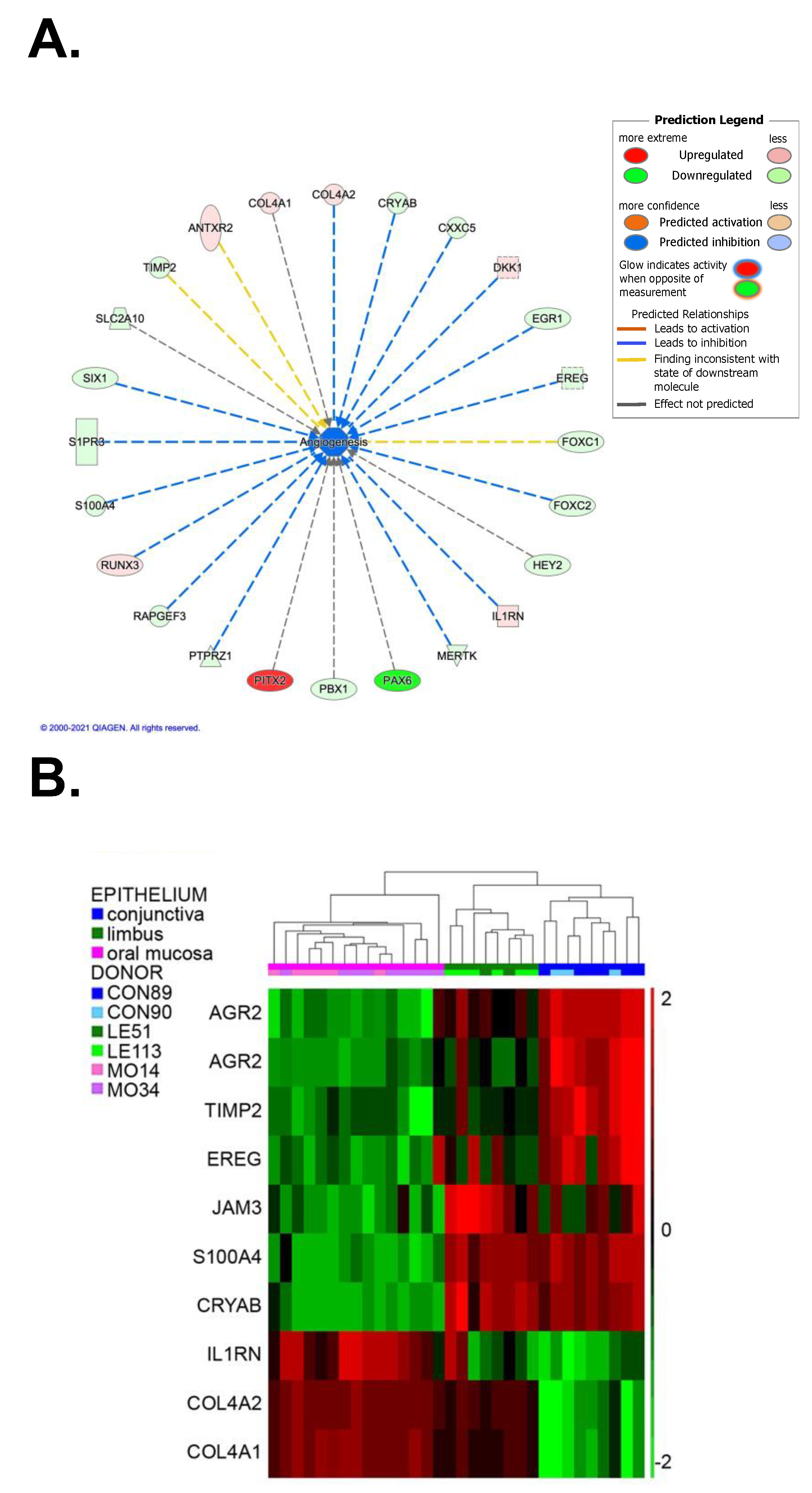

2.7. Angiogenic and antiangiogenic comparison between oral mucosa, limbus and conjunctiva

2.7.1. Proangiogenic factors

2.7.2. Antiangiogenic factors

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

1. Patients and Specimens

2. COMET Transplantation

3. Cell Cultures

4. Clonal Analysis and Colony Forming Efficiency assay

5. Microarray Analyses

6. Real-Time PCR

7. In situ Hybridization (ISH)

8. Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chiavelli C, Attico E, Sceberras V, Fantacci M, Melonari M, Pellegrini G. Stem cells and ocular regeneration. Encyclopedia of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. 2019, 1–3, 169–179. [Google Scholar]

- Sejpal K, Bakhtiari P, Deng SX. Presentation, Diagnosis and Management of Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2013, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng SX, Borderie V, Chan CC, Dana R, Figueiredo FC, Gomes JAP, et al. Global Consensus on Definition, Classification, Diagnosis, and Staging of Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Cornea. 2019, 38, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamo D, Attico E, Pellegrini G. Education for the translation of Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023, 10, 658. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini G, Ardigò D, Milazzo G, Iotti G, Guatelli P, Pelosi D, et al. Navigating Market Authorization: The Path Holoclar Took to Become the First Stem Cell Product Approved in the European Union. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2018, 7, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attico E, Sceberras V, Pellegrini G. Approaches for Effective Clinical Application of Stem Cell Transplantation. Curr Transplant Rep. 2018, 5, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daya, SM. Conjunctival-limbal autograft. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017, 28, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon KR, Tseng SCG. Limbal Autograft Transplantation for Ocular Surface Disorders. Ophthalmology. 1989, 96, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 9. Pellegrini G, Traverso CE, Franzi AT, Ingirian MZ, Cancedda R, de Luca M. Long-term restoration of damaged corneal surfaces with autologous cultivated corneal epithelium. 1997.

- Sangwan VS, Basu S, MacNeil S, Balasubramanian D. Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET): a novel surgical technique for the treatment of unilateral limbal stem cell deficiency. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2012, 96, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurizi E, Adamo D, Magrelli FM, Galaverni G, Attico E, Merra A, et al. Regenerative Medicine of Epithelia: Lessons From the Past and Future Goals. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Rama P, Matuska S, Paganoni G, Spinelli A, de Luca M, Pellegrini G. Limbal Stem-Cell Therapy and Long-Term Corneal Regeneration. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010, 363, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini G, Rama P, Matuska S, Lambiase A, Bonini S, Pocobelli A, et al. Biological parameters determining the clinical outcome of autologous cultures of limbal stem cells. Regenerative Med. 2013, 8, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura T, Inatomi T, Sotozono C, Amemiya T, Kanamura N, Kinoshita S. Transplantation of cultivated autologous oral mucosal epithelial cells in patients with severe ocular surface disorders. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004, 88, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attico E, Galaverni G, Pellegrini G. Clinical Studies of COMET for Total LSCD: a Review of the Methods and Molecular Markers for Follow-Up Characterizations. Current Ophthalmology Reports 2021 9:1. 2021, 9, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, G. Changing the Cell Source in Cell Therapy. 2004.

- Soma T, Hayashi R, Sugiyama H, Tsujikawa M, Kanayama S, Oie Y, et al. Maintenance and Distribution of Epithelial Stem/Progenitor Cells after Corneal Reconstruction Using Oral Mucosal Epithelial Cell Sheets. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e110987. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama H, Yamato M, Nishida K, Okano T. Evidence of the survival of ectopically transplanted oral mucosal epithelial stem cells after repeated wounding of cornea. Mol Ther. 2014, 22, 1544–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Yin M, Zhang LJ. Keratin 6, 16 and 17-Critical Barrier Alarmin Molecules in Skin Wounds and Psoriasis. Cells. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Attico E, Galaverni G, Bianchi E, Losi L, Manfredini R, Lambiase A, et al. SOX2 Is a Univocal Marker for Human Oral Mucosa Epithelium Useful in Post-COMET Patient Characterization. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Kalabusheva EP, Shtompel AS, Rippa AL, Ulianov S V. , Razin S V., Vorotelyak EA. A Kaleidoscope of Keratin Gene Expression and the Mosaic of Its Regulatory Mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, Vol 24, Page 5603. 2023, 24, 5603. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida K, Yamato M, Hayashida Y, Watanabe K, Yamamoto K, Adachi E, et al. Corneal reconstruction with tissue-engineered cell sheets composed of autologous oral mucosal epithelium. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004, 351, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrandon Y, Green H. Three clonal types of keratinocyte with different capacities for multiplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987, 84, 2302–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enzo E, Cattaneo C, Consiglio F, Polito MP, Bondanza S, De Luca M. Clonal analysis of human clonogenic keratinocytes. Methods Cell Biol. 2022, 170, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Vela I, Morrissey • C, Zhang • X, Chen • S, Corey • E, Strutton • G M, et al. PITX2 and non-canonical Wnt pathway interaction in metastatic prostate cancer. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Lovatt M, Yam GHF, Peh GS, Colman A, Dunn NR, Mehta JS. Directed differentiation of periocular mesenchyme from human embryonic stem cells. Differentiation. 2018, 99, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hin-Fai Yam G, Seah X, Zahirah Binte Yusoff NM, Setiawan M, Wahlig S, Myint Htoon H, et al. Characterization of Human Transition Zone Reveals a Putative Progenitor-Enriched Niche of Corneal Endothelium. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Guo H, Zhu Q, Yu X, Merugu SB, Mangukiya HB, Smith N, et al. Tumor-secreted anterior gradient-2 binds to VEGF and FGF2 and enhances their activities by promoting their homodimerization. Oncogene. 2017, 36, 5098–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu Q, Mangukiya HB, Mashausi DS, Guo H, Negi H, Merugu SB, et al. Anterior gradient 2 is induced in cutaneous wound and promotes wound healing through its adhesion domain. FEBS Journal. 2017, 284, 2856–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kase S, He S, Sonoda S, Kitamura M, Spee C, Wawrousek E, et al. αB-crystallin regulation of angiogenesis by modulation of VEGF. Blood. 2010, 115, 3398–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Qi X, Chen Z, Shaw L, Cai J, Smith LH, et al. Targeting the IRE1α/XBP1 and ATF6 arms of the unfolded protein response enhances VEGF blockade to prevent retinal and choroidal neovascularization. American Journal of Pathology. 2013, 182, 1412–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang WW, Yang LQ, Zhao F, Chen CW, Xu LH, Fu J, et al. Epiregulin promotes lung metastasis of salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Theranostics. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Semov A, Moreno MJ, Onichtchenko A, Abulrob A, Ball M, Ekiel I, et al. Metastasis-associated protein S100A4 induces angiogenesis through interaction with annexin II and accelerated plasmin formation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005, 280, 20833–20841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambartsumian N, Rg Klingelhoè Fer J, Grigorian M, Christensen C, Kriajevska M, Tulchinsky E, et al. The metastasis-associated Mts1(S100A4) protein could act as an angiogenic factor. 2001.

- Lamagna C, Hodivala-Dilke KM, Imhof BA, Aurrand-Lions M. Antibody against Junctional Adhesion Molecule-C Inhibits Angiogenesis and Tumor Growth. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 5703–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Yin H, Chen P, Xie L, Wang Y. Inhibitory Effect of Canstatin in Alkali Burn-Induced Corneal Neovascularization. Ophthalmic Res. 2011, 46, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada M, Yamawaki H. A current perspective of canstatin, a fragment of type IV collagen alpha 2 chain. J Pharmacol Sci. 2019, 139, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore JE, Mcmullen TCB, Campbell IL, Rohan R, Kaji Y, Afshari NA, et al. The Inflammatory Milieu Associated with Conjunctivalized Cornea and Its Alteration with IL-1 RA Gene Therapy. 2002.

- Ma X, Li J. Corneal neovascularization suppressed by TIMP2 released from human amniotic membranes. Yan ke xue bao = Eye science / “Yan ke xue bao” bian ji bu. 2005, 21, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas MP, Mysore N. Corneal neovascularization. Exp Eye Res. 2021, 202, 108363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekiyama E, Nakamura T, Cooper LJ, Kawasaki S, Hamuro J, Fullwood NJ, et al. Unique distribution of thrombospondin-1 in human ocular surface epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006, 47, 1352–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari G, Giacomini C, Bignami F, Moi D, Ranghetti A, Doglioni C, et al. Angiopoietin 2 expression in the cornea and its control of corneal neovascularisation. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2016, 100, 1005–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakaria N, van Grasdorff S, Wouters K, Rozema J, Koppen C. Human Tears Reveal Insights into Corneal Neovascularization. PLoS One. 2012, 7, 36451. [Google Scholar]

- Chen HCJ, Yeh LK, Tsai YJ, Lai CH, Chen CC, Lai JY, et al. Expression of angiogenesis-related factors in human corneas after cultivated oral mucosal epithelial transplantation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012, 53, 5615–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanayama S, Nishida K, Yamato M, Hayashi R, Sugiyama H, Soma T, et al. Analysis of angiogenesis induced by cultured corneal and oral mucosal epithelial cell sheets in vitro. Exp Eye Res. 2007, 85, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddipati S, Muralidhar R, Sangwan VS, Mariappan I, Vemuganti GK, Balasubramanian D. Oral epithelial cells transplanted on to corneal surface tend to adapt to the ocular phenotype. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014, 62, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim YJ, Lee HJ, Ryu JS, Kim YH, Jeon S, Oh JY, et al. Prospective Clinical Trial of Corneal Reconstruction With Biomaterial-Free Cultured Oral Mucosal Epithelial Cell Sheets. Cornea. 2018, 37, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson TRM, Coster DJ, Williams KA. The long term outcome of limbal allografts: the search for surviving cells. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Williams KA, Brereton HM, Aggarwal R, Sykes PJ, Turner DR, Russ GR, et al. Use of DNA polymorphisms and the polymerase chain reaction to examine the survival of a human limbal stem cell allograft. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995, 120, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjoqvist S, Kasai Y, Shimura D, Ishikawa T, Ali N, Iwata T, et al. Oral keratinocyte-derived exosomes regulate proliferation of fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019, 514, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjöqvist S, Ishikawa T, Shimura D, Kasai Y, Imafuku A, Bou-Ghannam S, et al. Exosomes derived from clinical-grade oral mucosal epithelial cell sheets promote wound healing. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao YT, Xie HT, Liu X, Duan CY, Qu JY, Zhang MC, et al. Subconjunctival Injection of Transdifferentiated Oral Mucosal Epithelial Cells for Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency in Rats. J Histochem Cytochem. 2021, 69, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa L, Carulli S, Cocchiarella F, Quaglino D, Enzo E, Franchini E, et al. Long-term stability and safety of transgenic cultured epidermal stem cells in gene therapy of junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Stem Cell Reports. 2014, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco P, Cao X, Frenette PS, Mao JJ, Robey PG, Simmons PJ, et al. The meaning, the sense and the significance: translating the science of mesenchymal stem cells into medicine. Nature Medicine 2013 19:1. 2013, 19, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca M, Albanese E, Megna M, Cancedda R, Mangiante PE, Cadoni A, et al. Evidence that human oral epithelium reconstituted in vitro and transplanted onto patients with defects in the oral mucosa retains properties of the original donor site. Transplantation. 1990, 50, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inatomi T, Nakamura T, Kojyo M, Koizumi N, Sotozono C, Kinoshita S. Ocular Surface Reconstruction With Combination of Cultivated Autologous Oral Mucosal Epithelial Transplantation and Penetrating Keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Inatomi T, Cooper LJ, Rigby H, Fullwood NJ, Kinoshita S. Phenotypic Investigation of Human Eyes with Transplanted Autologous Cultivated Oral Mucosal Epithelial Sheets for Severe Ocular Surface Diseases. Ophthalmology. 2007, 114, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen HCJ, Chen HL, Lai JY, Chen CC, Tsai YJ, Kuo MT, et al. Persistence of transplanted oral mucosal epithelial cells in human cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009, 50, 4660–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moll R, Divo M, Langbein L. The human keratins: Biology and pathology. Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 2008, 129, 705–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagali N, Wowra B, Fries FN, Latta L, Moslemani K, Utheim TP, et al. Early phenotypic features of aniridia-associated keratopathy and association with PAX6 coding mutations. Ocular Surface. 2020, 18, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latta L, Figueiredo FC, Ashery-Padan R, Collinson JM, Daniels J, Ferrari S, et al. Pathophysiology of aniridia-associated keratopathy: Developmental aspects and unanswered questions. Ocular Surface. 2021, 22, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage PJ, Kuang C, Zacharias AL. The homeodomain transcription factor PITX2 is required for specifying correct cell fates and establishing angiogenic privilege in the developing cornea. Developmental Dynamics. 2014, 243, 1391–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu W, Sun Z, Sweat Y, Sweat M, Venugopalan SR, Eliason S, et al. Pitx2-Sox2-Lef1 interactions specify progenitor oral/dental epithelial cell signaling centers. Development (Cambridge). 2020, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Essner JJ, Branford WW, Zhang J, Yost HJ. Mesendoderm and left-right brain, heart and gut development are differentially regulated by pitx2 isoforms. Development. 2000, 127, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh H, Gage PJ, Drouin J, Camper SA. Pitx2 is required at multiple stages of pituitary organogenesis: pituitary primordium formation and cell specification. Development. 2002, 129, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Selever J, Lu MF, Martin JF. Genetic dissection of Pitx2 in craniofacial development uncovers new functions in branchial arch morphogenesis, late aspects of tooth morphogenesis and cell migration. Development. 2003, 130, 6375–6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofyanti E, Pratamawati T. Prediction of Regulatory Networks of PITX2 Gene Expression in Mandibular Asymmetry Related to Oral Muscle Function. 2018.

- Franco, D. , Campione M. The role of Pitx2 during Cardiac Development. TCM. 2003, 13, No 4, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Martin DM, Skidmore JM, Philips ST, Vieira C, Gage PJ, Condie BG, et al. PITX2 is required for normal development of neurons in the mouse subthalamic nucleus and midbrain. Dev Biol. 2004, 267, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen L, Martino V, Dombkowski A, Williams T, West-Mays J, Gage PJ. Ap-2β is a downstream effector of PITX2 required to specify endothelium and establish angiogenic privilege during corneal development. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016, 57, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perveen R, Lloyd IC, Clayton-Smith J, Churchill A, Van Heyningen V, Hanson I, et al. Phenotypic Variability and Asymmetry of Rieger Syndrome Associated with PITX2 Mutations. 2000.

- Zhang JX, Tong ZT, Yang L, Wang F, Chai HP, Zhang F, et al. PITX2: A promising predictive biomarker of patients’ prognosis and chemoradioresistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2013, 132, 2567–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semaan A, Uhl B, Branchi V, Lingohr P, Bootz F, Kristiansen G, et al. Significance of PITX2 Promoter Methylation in Colorectal Carcinoma Prognosis. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2018, 17, e385–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung FKC, Chan DW, Liu VWS, Leung THY, Cheung ANY, Ngan HYS. Increased expression of PITX2 transcription factor contributes to ovarian cancer progression. PLoS One. 2012, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Guigon CJ, Fan J, Cheng SY, Zhu GZ. Pituitary homeobox 2 (PITX2) promotes thyroid carcinogenesis by activation of cyclin D2. Cell Cycle. 2010, 9, 1333–1341.

- Cox CJ, Espinoza HM, McWilliams B, Chappell K, Morton L, Hjalt TA, et al. Differential regulation of gene expression by PITX2 isoforms. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002, 277, 25001–25010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba P, Hjalt TA, Bernard DJ. Novel forms of Paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 2 (PITX2): Generation by alternative translation initiation and mRNA splicing. BMC Mol Biol. 2008, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Sceberras V, Maria Magrelli F, Adamo D, Maurizi E, Attico E, Giuseppe Genna V, et al. The cell as a tool to understand and repair urethra. Scientific Advances in Reconstructive Urology and Tissue Engineering. 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sceberras V, Attico E, Bianchi E, Galaverni G, Melonari M, Corradini F, et al. Preclinical study for treatment of hypospadias by advanced therapy medicinal products. World J Urol. 2020, 38, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krämer A, Green J, Pollard J, Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in ingenuity pathway analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014, 30, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Epithelium | Strain | N. of holoclones |

|---|---|---|

| Conjunctiva | CON-89 | 6 |

| CON-90 | 3 | |

| Limbus | LE-51 | 2 |

| LE-113 | 6 | |

| Oral Mucosa | MO-14 | 6 |

| MO-34 | 9 |

| Target gene | Forward Primer (5’-3’) | Reverse Primer (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|

| PITX2 tot | CAGCCTGAGACTGAAAGCA | GCCCACGACCTTCTAGCAT |

| PITX2A | GCGTGTGTGCAATTAGAGAAAG | CCGAAGCCATTCTTGCATAG |

| PITX2B | GCCGTTGAATGTCTCTTCTC | CCTTTGCCGCTTCTTCTTAG |

| PITX2C | ACTTTCCGTCTCCGGACTTT | CGCGACGCTCTACTAGTC |

| GAPDH | GACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC | TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).