1. Introduction

Vascular tumours of the liver are a significant medical issue, representing an underappreciated chapter of medical and surgical hepatology [

1]. They still pose a diagnostic problem for GPs and are thus often detected far too late, due to their low prevalence rates. There are three (3) main types of vascular lesions, diagnosed in the liver: focal, multifocal and diffuse [

2]. Multifocal hepatic hemangiomas (MHHs) are the most common benign vascular tumours of the liver that are detected in children with concomitant multiple infantile hemangiomas [

3,

4]. Vascular lesions undergo the phase of proliferation and growth, followed by involution, the onset of which appears in the second half of the child’s first year of life, and the medical condition lasts for about 5-7 years [

5,

6]. MHHs are most commonly identified in infants under 6 months of age [

7]. A study by Yi Ji, Siyuan Chen et al. revealed the median age at diagnosis as 2.5 months [

3]. Hepatic hemangioma arises from a vascular malformation but its pathophysiology has not yet been clearly elucidated [

8]. This tumour consists of large vascular beds, demanding a significant increase in blood flow as the lesion grows [

9]. The risk factors are not fully known, either [

3]. However, glycolysis-associated molecules, including GLUT-1, do not seem to be insignificant [

10]. Female infants demonstrate higher incidence rates of the disease, compared to male infants, the ratio being 1.3:1 to 2:1, respectively. No racial predisposition has been found. A familial tendency towards MHH has also been described [

5].

MHHs are usually undetectable at birth [

11]. With the development of high-resolution prenatal ultrasound technology and routine ultrasound follow-up, practised at most teaching and/or tertiary referral hospitals, the detection rate of hepatic hemangiomas in infants has in recent years been demonstrating a clearly growing tendency [

12]. One should, therefore, emphasise the important role of diagnostic imaging in the identification of hepatic hemangiomas at an early stage.

Patients with MHH, not previously diagnosed, are most commonly identified by some enlargement of the abdominal circumference, congestive heart failure (CHF), anaemia, thrombocytopenia, hypothyroidism (due to the expression of iodothyronine deiodinase), jaundice, up to biliary obstruction or liver failure, which often leads to death in children under 3 months of age [

3,

11,

13,

14].

As a consequence of the above-mentioned complications, some patients may develop a life-threatening condition. The heterogeneity of the lesions and the presence of comorbidities make often the management of infantile hepatic hemangiomas a true challenge, also for highly specialised medical professionals [

15].

Referring to older publications, the mortality rate ranged between 30% and 80%, but recently published studies show a significant decrease in the incidence rate of the disease, which now ranges between 11% and 18% for treated and untreated hepatic hemangiomas, respectively [

4,

16]. However, given the still significant mortality rate of this medical condition, it is all the more important to draw attention to the nature of the problem.

2. Case Description

A boy from pregnancy II, delivery I, was born at the 30th week of gestation. The respiratory distress syndrome was identified in history and the neonate was diagnosed and treated at the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Cranial ultrasound scan (CrUSS) revealed status post grade II haemorrhage on the right side. A series of ultrasound examinations, performed at bedside at the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, demonstrated normal images of the abdominal organs (see

Figure 1)—the US examination was performed four times on day 3, 17, 24 and 40 of the baby’s life.

At week 4, clinical deterioration was observed, including an increased frequency of apnoeas, vomiting, gastric retention and elevated inflammatory markers. Klebsiella aerogenes and RSV infections were diagnosed. The baby was then transferred to the Neonatal Pathology Department, where the previous recommendations were carried on. An abdominal ultrasound was performed again, revealing the normoechoic liver, with the midclavicular line of 41 mm.

At 4 months of age, due to increased posseting and distress, the child was referred to the Infant Department, where abdominal ultrasound revealed multiple hypoechoic focal lesions of approximately 13 mm in size. A suspicion was raised of multifocal infantile hemangiomas in the proliferative phase. After a few days, the child was transferred to the Paediatric Gastroenterology and Hepatology Department for verification of the diagnosis. In addition, the child demonstrated multiple hemangiomas on the skin (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figures 2 and 3.

Multiple hemangiomas on the skin.

Figures 2 and 3.

Multiple hemangiomas on the skin.

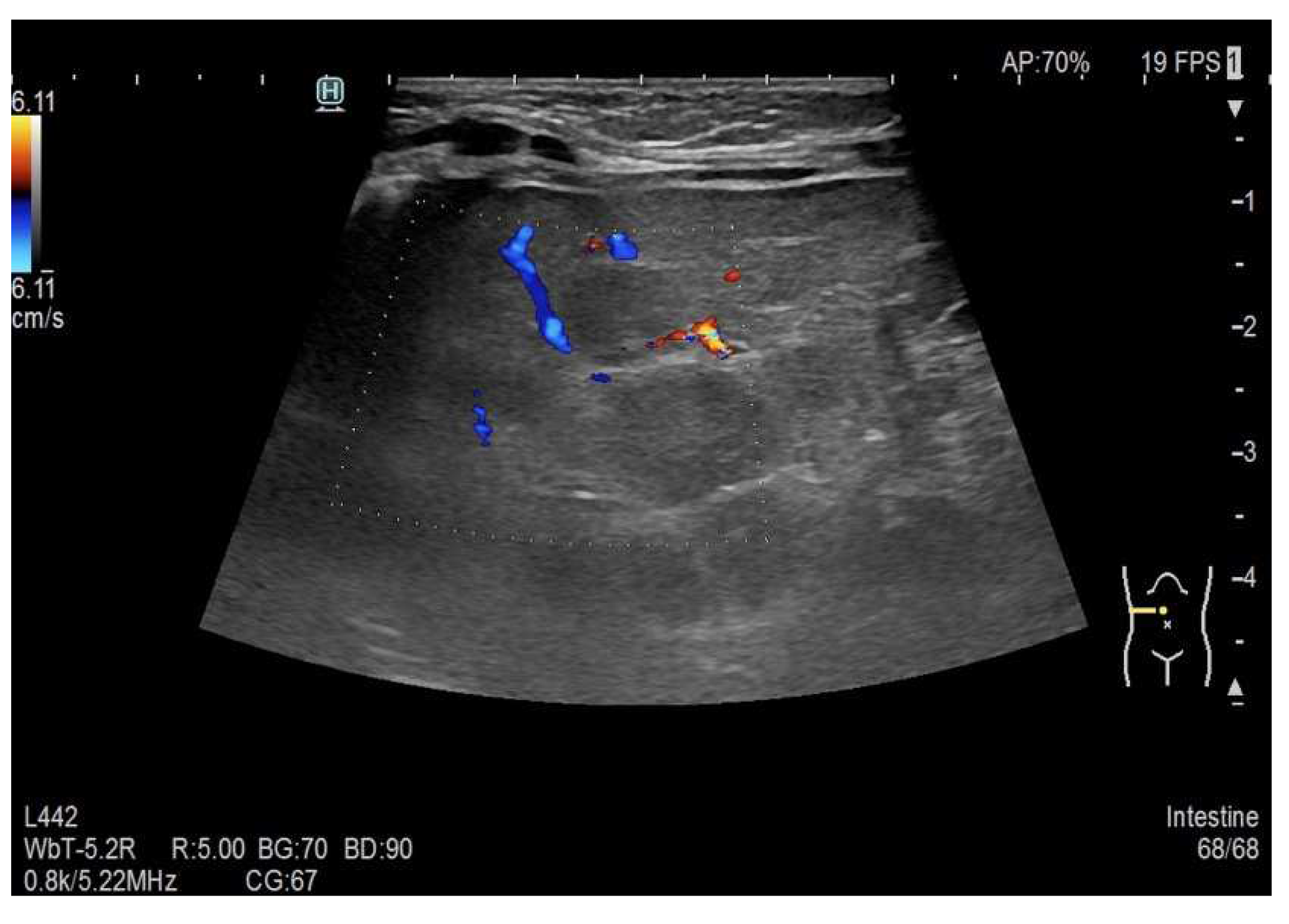

As part of the in-hospital diagnostics, an abdominal ultrasound was performed, confirming the presence of multiple hypoechoic liver lesions of up to approximately 12 mm in size (see

Figure 4). Some of the described lesions showed sparse peripheral vascularisation (see

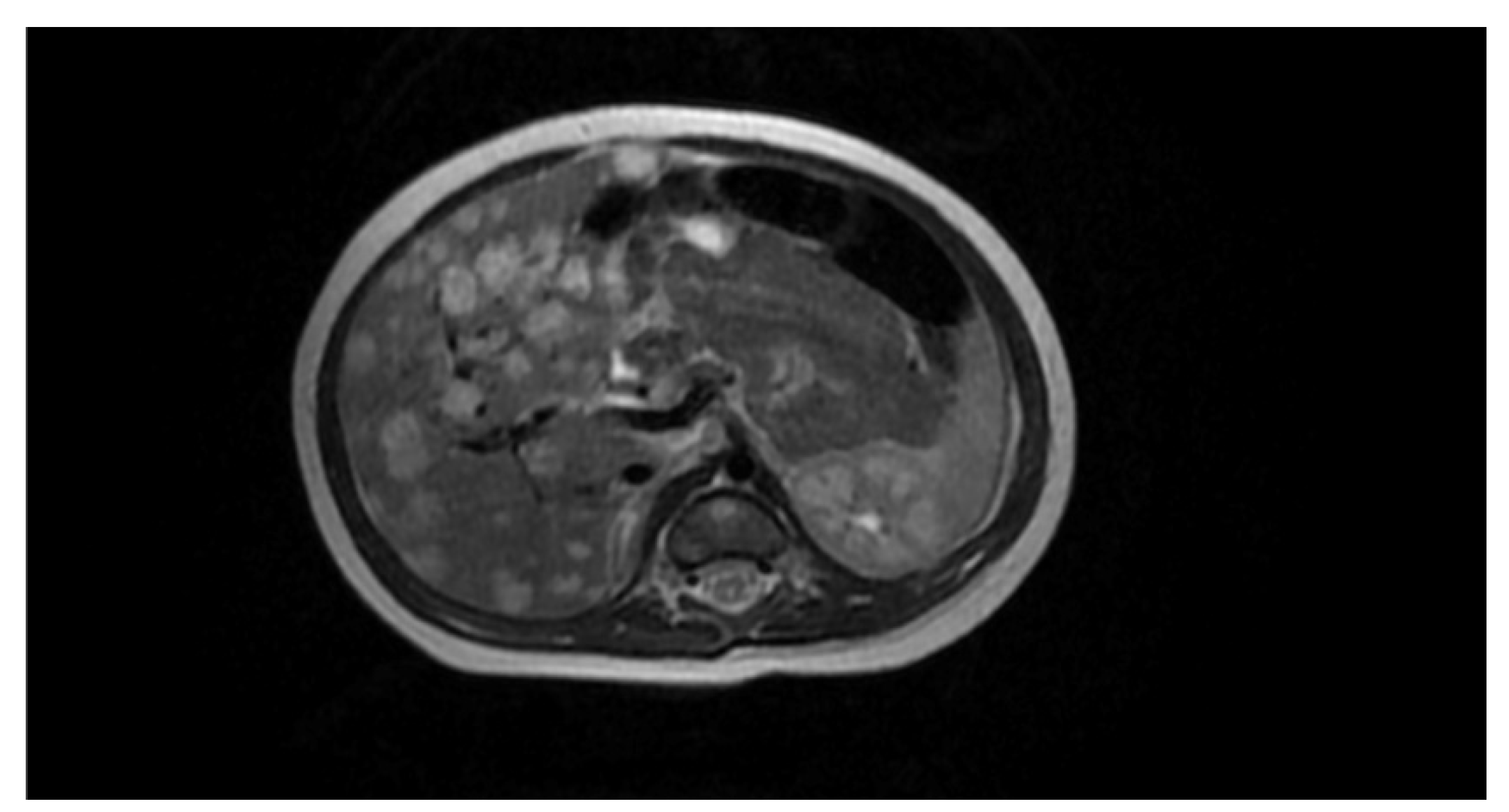

Figure 5). In order to extend the diagnostic picture of the described focal lesions, a dynamic contrast-enhanced abdominal MRI scanning was performed, revealing multiple hyperintense lesions in T2-weighted sequences, scattered throughout the liver (see

Figure 6). The identified lesions showed a characteristic post-contrast enhancement in signal intensity (rising from peripheral to central areas), maintaining a high signal also in delayed phases. The DWI (diffusion-weighted imaging) sequence did not show any features of water molecule diffusion restriction. The image described was characteristic of hemangiomas. A final diagnosis of the multifocal hepatic hemangioma (MHH) syndrome was established.

A cardiological consultation was also carried out, which did not identify any worrying cardiovascular symptoms or contraindications to propranolol treatment. The patient was discharged from the Department with recommendations of follow-up at the hospital paediatric surgical outpatient clinic and regular follow-up visits at the district outpatient clinic, as well as of possible periodical gastrological control examinations.

At 5 months of age, the child had a follow-up visit at the hospital surgical outpatient clinic, where propranolol was introduced at a dose of 2 mg 3x/day. Due to the ongoing symptoms of posseting, trimebutine, a syrup with anti-reflux effect, was also included and the milk mixture was recommended to be thickened carob powder. In addition, supplementation with vitamins B, D and iron was ordered. The reflux (posseting) episodes disappeared after the anti-reflux medication. After one week, the propranolol dose was increased to 4 mg 3x/day. After a period of a further 2 weeks, a decision was taken to increase the dose of the drug up to 6 mg 3x/day.

A follow-up cardiological consultation was performed, confirming no contraindications to continue the β-blocker therapy. At 7 months of life, the dose of propranolol was increased to 7.5 mg 3x/day.

An abdominal ultrasound examination, performed during a neonatal and surgical consultation at the 9

th month of life, showed almost complete regression of the hepatic hemangiomas (see

Figure 7). A liver with homogeneous parenchymal echogenicity was observed, with the exception of a circular hypoechoic lesion, located in segment VI, its diameter being 9 mm (see

Figure 8). The liver size in the midclavicular line was 77 mm.

No fresh skin lesions were found and the previously described lesions either faded or completely regressed (see Figure 9 and Figure 10). The boy’s general condition after the applied pharmacotherapy was good. In consideration of the positive effects of the treatment and of literature data, a decision was made to continue the propranolol treatment at a dose of 7.5 mg 3x/day until the child was 12 months old.

Figures 9 and 10.

The previously described lesions either faded or completely regressed.

Figures 9 and 10.

The previously described lesions either faded or completely regressed.

3. Discussion

Infants are usually brought to a doctor within the first few weeks of life when observed skin lesions become proliferative, as in case of the boy described above. The association of IHs with their hepatic counterpart has led to indications that abdominal ultrasonography should be performed in patients with multiple skin lesions [

11]. However, no significant association is found between the number of hepatic hemangiomas and the number of IHs [

3]. The vascular skin lesions in the patient described were quite discrete, which was a great disproportion vs. the massive vascular lesions in the liver. The true incidence of MHH remains undetermined as many small lesions produce no symptoms and are impossible to identify. MHHs are sometimes incidentally detected only during imaging scans for various unrelated pathologies [

5,

17]. It follows then that screening should be a common practice during the first months of life for infants with the above-mentioned skin lesions [

18].

Screening for infantile hepatic hemangiomas (IHH) is recommended in infants under nine months of age with five or more cutaneous hemangiomas [

19].

Ultrasound (USG) should be the imaging examination performed in the first instance in search for vascular anomalies in children. Other examinations which are, however, performed relatively infrequently, are computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [

2].

The treatment of IHH in the past included corticosteroids, interferon α, vincristine and cyclophosphamide [

20]. Currently, the most common treatment regimen is a therapy with prednisone and propranolol, administered orally [

3,

21]. The treatment of hemangiomas with non-selective β-blockers, if no contraindications are identified, should be implemented as soon as the diagnosis is established, regardless of the child’s age [

22]. Some reports indicate that propranolol is more efficient than corticosteroids, achieving faster patient improvement, but these studies are limited by their rather small study groups and the striking lack of randomisation.

In order to improve the clinical condition of the presented patient more rapidly, it was decided to implement propranolol in monotherapy. Some papers recommend propranolol at a dose of 2–3 mg/kg/day, together with corticosteroids at a dose of 1.0–1.5 mg/kg/day, as the first-line therapy. The pharmacotherapy is usually continued for at least 6 months and is often maintained until 12 months of age [

8,

23,

24,

25]. A favourable response from corticosteroid-resistant hemangiomas can be obtained with propranolol in monotherapy [

16].

The use of propranolol in therapy had definitely an impact on reducing the number of operations but it did not completely rule out invasive treatment [

26]. Despite their benign course, some IHHs, especially their multiple and diffuse forms, may require medical and/or surgical intervention. Therefore, a continuous follow-up and observation of the patient are required until the lesions completely resolve [

4,

27]. Consequently, the described boy with the diagnosis of MHH is under a constant care of the surgical outpatient clinic. No aggressive treatment should be implemented in asymptomatic patients, in whom observation appears to be a safer choice. Invasive treatment is usually indicated in symptomatic or progressive multiple hepatic hemangiomas only [

3,

28]. In case of the aforementioned patient, pharmacotherapy achieved the expected results without the need of invasive treatment.

Surgical treatment, understood as embolisation, ligation of the hepatic artery or resection of the liver, is necessary for more aggressive clinical courses of the disease. The size of hepatic hemangiomas is also an important issue, affecting intraoperative blood loss and the timing of the operation itself [

29]. When all of the above-mentioned measures fail, liver transplantation may be considered which, however, may be associated with a high rate of complications, such as bleeding and liver necrosis [

20].

An additional issue is the accompanying cutaneous angiomas, localised in the face, for which intraoperative triamcinolone injections can be used [

30].

4. Conclusions

It appears from the presented case report that imaging scans, such as ultrasound, CT and MRI, play the most important role in the diagnostics and monitoring of MHH. The importance of the physical examination should also be emphasised to detect cutaneous hemangiomas, which usually accompany MHH and should prompt the physician to regularly observe and repeat abdominal ultrasound examinations of the diagnosed and/or treated child. Propranolol is an effective pharmacological option, which should be implemented into treatment as soon as MHHs are diagnosed.

Funding

This research was funded by Medical University of Silesia in Katowice.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lerut J., Iesari S. Vascular tumours of the liver: a particular story. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 3: p. 62. [CrossRef]

- Esposito F., D’Auria D., Ferrara D., et al. Hepatic hemangiomas in childhood: the spectrum of radiologic findings. A pictorial essay. J Ultrasound 2022; 26, pp. 261–276. [CrossRef]

- Ji Y., Chen S., Xiang B., et al. Clinical features and management of multifocal hepatic hemangiomas in children: a retrospective study. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: p. 31744. [CrossRef]

- Gnarra M., Behr G., Kitajewski A., et al. History of the infantile hepatic hemangioma: From imaging to generating a differential diagnosis. World J Clin Pediatr 2016; 5(3): pp. 273-280. [CrossRef]

- Zavras N., Dimopoulou A., Machairas N., et al. Infantile hepatic hemangioma: current state of the art, controversies, and perspectives. Eur J Pediatr 2020; 179: pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Bandera Ana I., Sebaratnam D. F., Wargon O., et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 1: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 85(6): pp. 1379-1392. [CrossRef]

- Maaloul I., Aloulou H., Hentati Y., et al. Infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma successfully treated by low dose of propranolol. Presse Med 2017; 46(4): pp. 454-456. [CrossRef]

- Leon M., Chavez L., Surani S. Hepatic hemangioma: What internists need to know. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(1): pp. 11-20. [CrossRef]

- Speicher M. V., Lim D. M., Field A. G., et al. An Unusual Case of Neonatal High-Output Heart Failure: Infantile Hepatic Hemangioma. J Emerg Med 2021; 60(1): pp. 107-111. [CrossRef]

- Chen J., Wu D., Dong Z., et al. The expression and role of glycolysis-associated molecules in infantile hemangioma. Life Sci 2020; 259: p. 118215. [CrossRef]

- Rialon K. L., Murillo R., Fevurly R. D., et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients with multifocal and diffuse hepatic hemangiomas. J Pediatr Surg 2015; 50(5): pp. 837-841. [CrossRef]

- Tsai MC., Liu HC., Yeung CY. Efficacy of infantile hepatic hemangioma with propranolol treatment. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98(4): e14078. [CrossRef]

- Telega G. Neonatal Liver Failure. Pediatr Pol 2012; 87(3): pp. 242-245. [CrossRef]

- Kurzeja M., Pawlik K., Sienicka A., et al. Infantile Hemangioma. Dermatol Rev/Przegl Dermatol 2022; 107: pp. 204–216. [CrossRef]

- Gong X., Li Y., Yang K., et al. Infantile hepatic hemangiomas: looking backwards and forwards. Precis Clin Med 2022; 5(1): pbac 006. [CrossRef]

- Cichy B. Propranolol for the treatment of infantile hemangioma and lymphangiomatosis. Pediatr Pol 2011; 86(4): pp. 372-375. [CrossRef]

- Aziz H., Brown Z. J., Baghdadi A., et al. A Comprehensive Review of Hepatic Hemangioma Management. J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 26(9): pp. 1998-2007. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas I., Phung T. L., Adams D. M., et al. Guidance Document for Hepatic Hemangioma (Infantile and Congenital) Evaluation and Monitoring. J Pediatr 2018; 203: pp. 294-300. [CrossRef]

- Ji Y., Chen S., Yang K. et al. Screening for infantile hepatic hemangioma in patients with cutaneous infantile hemangioma: A multicenter prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 84(5): pp. 1378-1384. [CrossRef]

- Varrasso G., Schiavetti A., Lanciotti S., et al. Propranolol as First Line Treatment for Life-threatening Diffuse Infantile Hepatic Hemangioma: a Case Report. Hepatology 2017; 66(1): pp. 283-285. [CrossRef]

- Léauté-Labrèze Ch., Harper J. I, Hoeger P. H., et al. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet 2017; 390(10089): pp. 85-94. [CrossRef]

- Cichy B. Systemic and topical nonselective β-blockers therapy for vascular tumors. Pediatr Pol 2013; 88(1): pp. 75-79. [CrossRef]

- Krowchuk D. P., Frieden I. J., Mancini A. J., et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas. Pediatrics 2019; 143(1): e20183475. [CrossRef]

- Sarıalioğlu F., Yazıcı N., Erbay A. et al. A New Perspective for Infantile Hepatic Hemangioma in the Age of Propranolol: Experience at Baskent University. Exp Clin Transplant 2017; 15(2): pp. 74-78. [CrossRef]

- Cichy B. Propranolol in treatment of hemangiomas—old drug, new implementation and many doubts. Pediatr Pol 2009; 84(6): pp. 583-585.

- Macdonald A., Durkin N., Deganello A., et al. Historical and Contemporary Management of Infantile Hepatic Hemangioma: A 30-year Single-center Experience. Ann Surg 2022; 275(1): pp. 250-255. [CrossRef]

- Ernst L., Grabhorn E. Brinkert F., et al. Infantile Hepatic Hemangioma: Avoiding Unnecessary Invasive Procedures. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2020; 23(1): pp. 72-78. [CrossRef]

- Smithson S. L., Rademaker M., Adams S., et al. Consensus statement for the treatment of infantile haemangiomas with propranolol 2017; 58(2): pp. 155-159. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Wahab M., El Nakeeb A., Ali MA, et al. Surgical Management of Giant Hepatic Hemangioma: Single Center’s Experience with 144 Patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2018; 22(5): pp. 849-858. [CrossRef]

- Yang K., Peng S., Chen L., et al. Efficacy of propranolol treatment in infantile hepatic haemangioma. J Paediatr Child Health 2019; 55(10): pp. 1194-1200. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).