1. Introduction

The high performance electric drive systems are now designed to fulfill the main requirements such as fast transient, high power density, high efficiency, low rotor inertia. On a large scale, the most popular used electric machine is the induction one, but with low efficiency for low power range, which makes it to be inappropriate for this kind of application. A secondary option is represented by the permanent magnet synchronous machine with various benefits as high efficiency and low rotor inertia, but with the main drawback given by the demagnetization phenomenon when operating at high temperatures. At last, the synchronous reluctance machine (SynRM) becomes an attractive solution for a large range of power and speed, being a low-cost machine with eco-friendly environment impact, and multiple benefits, as: compact sizes, low mass and rotor inertia, and the rotor having no electric windings, cage, or permanent magnets. For the modern applications of SynRM drives, advanced control algorithms are used to obtain high performances such as fast transient regime, good tracking results, efficient disturbance rejection [

1,

2].

The main control strategies of SynRM are divided into the following categories: constant

d-axis current control (when the torque is varied by the

q-axis current), current angle control (with the groups: fast torque response, maximum power factor control, maximum torque per ampere control) and active flux control [

4,

5]. These control strategies are usually implemented using the field-oriented control (FOC) concept, which involves a cascade control structure with an outer loop for angular speed control and an inner loop for

d-axis and

q-axis currents control. To control the

d-axis and

q-axis currents independently, decoupling feedforward components are frequently used in both current control loops.

For FOC approach, simple control solutions, such as proportional–integral (PI) controllers are dominant in many applications but having as main drawback the inability to deal with constraints in a nonconservative way. For example, a cascade structure based on FOC that uses the constant

d-axis current strategy whose two loops controllers are PI is given in [

6]. In [

4], the performances obtained with PI controllers are comparatively analyzed for the main control strategies of SynRM implemented in a cascade control structure based on FOC. With a constant

d-axis current reference, in [

7] a FOC strategy with PI controllers having an anti-wind-up mechanism is used to develop a cascade control structure for SynRM.

The current control problem of the SynRM is a quadratically constrained problem and for this reason, a solution was the use of model predictive control (MPC) algorithms that can automatically handle the constraints. However, at the beginning the main problem in using MPC algorithms for SynRM control was the computational complexity. In recent years, with the advances in hardware and solver development, MPC strategy can be successfully implemented in SynRM control systems. For the predictive current control, based on the way in which the switching action of the power inverter is produced, the finite set or continuous set approach is used. Thus, in [

8], a current predictive control algorithm for a finite set of switching actions of the power inverter was introduced based on a one-step-ahead prediction model obtained by the discretization of the continuous time coupled non-linear multivariable

dq current model with the forward Euler method. Using a cost function with soft constraints, the optimal switching vector for the inverter was selected. A similar current predictive control algorithm is presented in [

9], considering a coupled linear multivariable

dq current model by using a constant rotor electrical angular speed. The overcurrent protection is obtained by adding a variable in the cost function that considers the safety current limits. Recently, model-free MPC current controllers have been developed. Thus, this approach is presented in [

10] using a model-free MPC current controller based on a finite-set unconstrained approach. For current prediction, current measurements continually updated stored in a look-up table are employed. A similar approach, where an improved unconstrained model-free MPC current control based on a flux-current map of SynRM for considering the nonlinear magnetic features of SynRM can be found in [

11]. At the same time, in [

12] an unconstrained continuous-set model-free MPC algorithm without using the explicit model of SynRM is introduced.

Starting from the multivariable model of

dq currents and the monovariable one obtained by decoupling, in [

13] MPC current controllers with constraints based on continuous set approach are designed and their performances are compared.

For the outer loop, meant to control the angular speed of SynRM, the PI controller is the most frequently used [

3,

4], [

6,

7]. Due to the difficulty of this controller regarding constraints handling, MPC algorithms are also used for speed control [

14].

Although, the MPC with finite set control is widely used in SynRM control due to certain benefits in SynRM control [

7], the high switching frequency required by this strategy [

15,

16] reduces the performances of the practical applications, becoming an impediment for real-time implementation. At the same time, for MPC with finite set control strategy, the constraints handling is difficult. The overcurrent protection is usually obtained by adding a soft constraint set in the cost function that considers the safety current limits, while the voltage limitations are directly imposed by the searching algorithm which generates a voltage magnitude in the admissible domain.

Regarding the continuous set approach used for field oriented predictive control of SynRM, according to the authors' knowledge, few results have been reported. Thus, in [

18] the design and implementation of a current controller for a SynRM based on the continuous set nonlinear model predictive control is described. For a permanent magnet assisted synchronous reluctance motor (PMA-SynRM), starting from nonlinear dynamical model in [

19], the design of a continuous set MPC based on an augmented linearized model is presented.

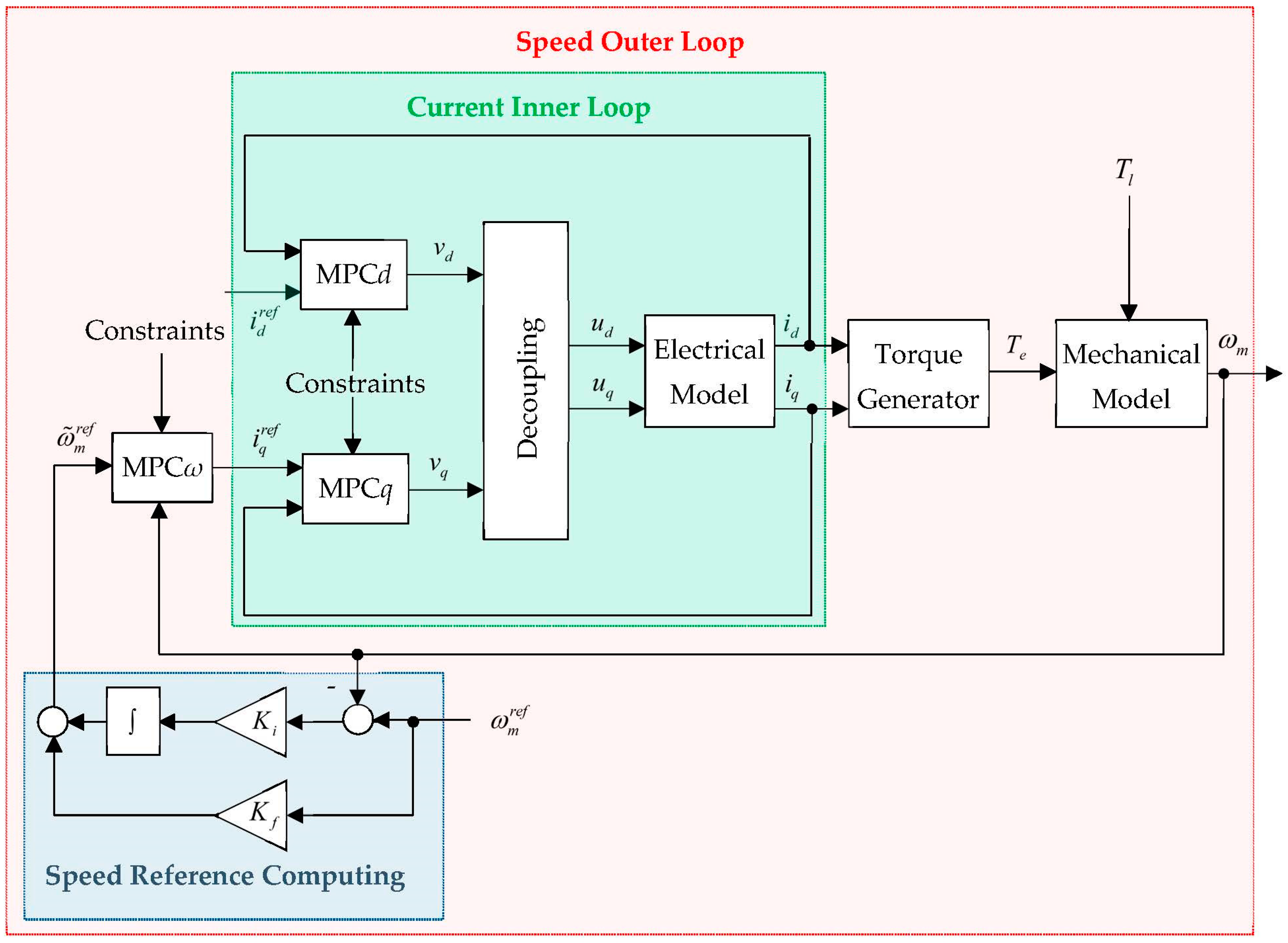

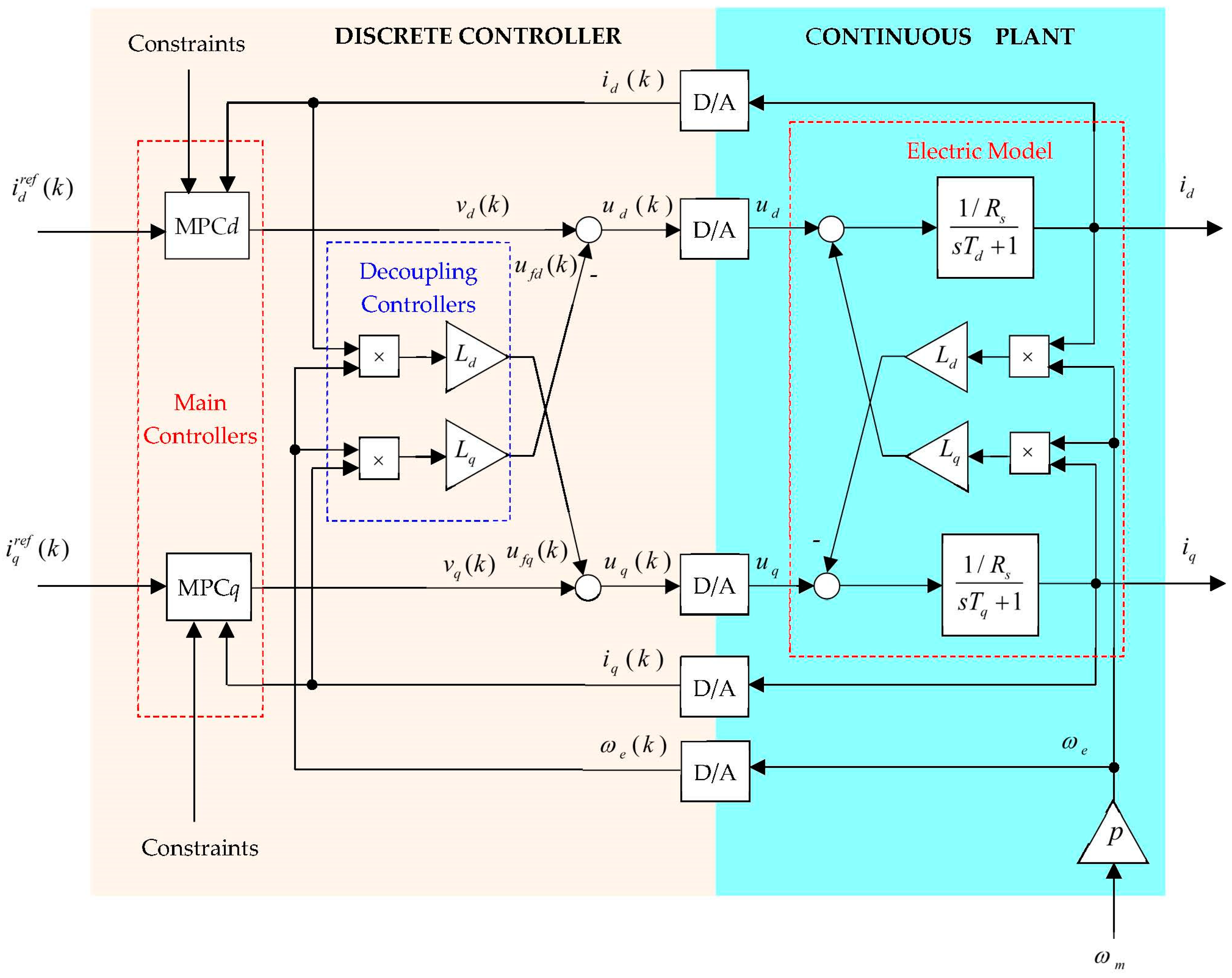

In this paper a cascade predictive control structure based on FOC in dq rotor reference frame for SynRM was proposed. Among the FOC-based SynRM control strategies, the constant d-axis current control was chosen, which provides the direct control of the electromagnetic torque through the q-axis current. Because the model of the two axes currents from the inner loop is a coupled non-linear multivariable one, to non-interaction linear control the two currents, their decoupling was achieved through feedforward components. In this way, the dynamics of the d-axis current, which must be constant, is not influenced by the q-axis current variations. After decoupling, two independent monovariable linear systems resulted for the two currents dynamics that were controlled using MPC algorithms, due to their ability to automatically handle the bounds imposed on the states.

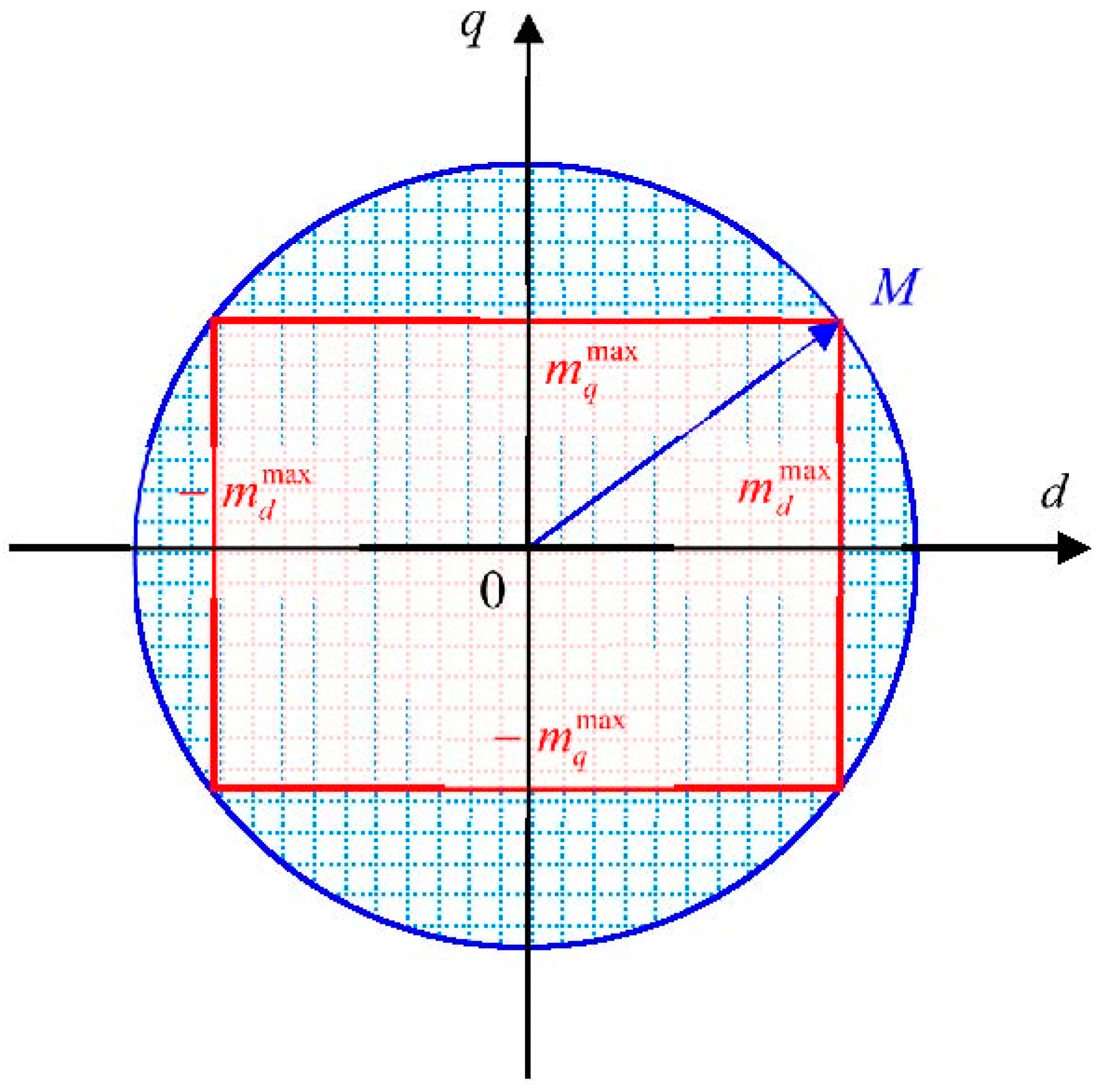

The most important bounds for SynRM are the limits imposed on currents and voltages, which in the dq plane correspond to circular regions. To avoid computational effort, linear limitations were adopted through polygonal approximations, resulting in rectangular regions in the dq plane. For the d-axis current, the upper limit was imposed as its reference, and thus, the parameter of the circular region transformation related to the currents into a rectangular one was defined by the ratio between the d-axis current reference and the maximum stator current. The transformation of the circular region related to the voltages into a rectangular one in the dq plane was carried out by a parameter chosen by the user. To obtain the constraints imposed on the outputs of the MPC current controllers, the voltage limitations in the dq plane were considered, to which the maximum values of the feedforward components were appropriately added. For the outer loop that controls the angular speed with a constrained MPC algorithm, it was considered as plant the q-axis current closed loop dynamics and the linear equation of the torque depending on the q-axis current. To eliminate the steady state speed error due to unmeasured disturbance generated by the load torque and modeling errors, the user speed reference of the MPC speed controller is replaced by adding an integral action and a feedforward component.

The MPC algorithms were designed in such a way to obtain reference tracking by adding an additional state to the plant model to obtain input increment which becomes optimization variable. The cost functions and related constraints used for MPC algorithms design were transformed into a quadratic programming (QP) problem. To avoid the infeasibility of the QP problem, some constraints are treated as soft constraints by using a slack variable. The implementation is done in Matlab-Simulink using the facilities offered by the MPC Designer from Model Predictive Control Toolbox. To evaluate the performance of the proposed cascade predictive control structure based on FOC in the dq rotor reference frame for SynRM, a simulation study using MPC controllers versus PI ones was conducted. PI controllers, often used for the cascade control of SynRM in industrial applications, were designed using the pole-placement method, and to limit some variables imposed by the constraints, saturation type blocks were introduced at the output of the controllers together with the related anti-windup mechanisms. Since the design method introduces a zero in the closed loop system, a zero-cancelation ZC block was used in order not to alter the performances. Finally, through a comparative analysis of the performances obtained with the MPC and ZC-PI controllers respectively, the better performing behavior of the predictive control cascade structure resulted.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section II the dq SynRM model with physical limits together with the cascade predictive control structure in the dq rotor reference frame are presented. Section III is dedicated to the design of the inner and outer loops of the proposed cascade predictive control structure. A comparative analysis of the performances obtained with the MPC and ZC-PI controllers is given in Section IV. The conclusions of the paper are presented in Section V.

4. Illustrative case study

To evaluate the performances of the proposed cascade predictive control structure for SynRM, a simulation study was carried out using a Simulink model of the motor in dq coordinates and predictive controllers from the MPC Simulink Library.

The simulation results were compared with those obtained with a cascade regulation structure with ZC-PI controllers instead of MPC ones, often used in industrial applications. For the design of the PI controllers, the pole placement method was used [

25], considering the

R-L plant transfer function for the current controllers:

and the mechanical plant transfer function for the speed controller, neglecting the inner loop dynamics:

Following the design of the PI controllers, the tuning parameters of the current and speed controllers resulted:

where

is the natural frequency and

is the loop attenuation of the inner/outer loop systems. Furthermore, a zero appears in the closed–loop transfer function which can be canceled by introducing a zero–cancellation block ZC in the feedforward path [

25].

The saturation used for ZC-PI controllers output constraints requires an anti-windup mechanism [

26].

For the simulation study,

Table 1 with the specifications of the SynRM from [

9,

27] was used.

Table 1.

SynRM specifications.

Table 1.

SynRM specifications.

| Symbol |

Description |

Values |

|

PN [W] |

Nominal power |

3000 |

|

UN [V] |

Nominal voltage |

355 |

|

TN [Nm] |

Nominal torque |

19.1 |

|

ψaN [Wb] |

Nominal active flux |

0.69 |

|

IN [A] |

Nominal current |

7.9 |

|

ωmN [rad/sec] |

Nominal speed |

157 |

|

Rs [Ω] |

Rotor resistence |

1.35 |

|

Ld [H] |

Direct axis inductance |

0.186 |

|

Lq [H] |

Quadrature axis inductance |

0.04 |

|

J[kg∙m2] |

Rotor inertia |

0.079 |

| p |

Stator pole pairs |

2 |

|

UDC [V] |

Nominal DC link voltage |

650 |

The sampling period for the controller design was chosen Ts = 50 microseconds according to the requirements of the current loops’ dynamics.

With the SynRM parameters from

Table 1, the inner plant model used for MPC current controllers design turns into:

and the outer plant model including inner loops dynamics for MPC speed controller design becomes:

The simulation study is performed in Matlab-Simulink environment, by using the MPC Designer block from Model Predictive Control Toolbox. Since the control strategy based on keeping constant the current on the

d-axis was chosen for the cascade predictive control structure of SynRM, the reference for

id is calculated with

[

27].

The limit values of the constraints were determined based on the method from

Section 2, using the rectangular regions from

Figure 1. The circle radius

M for currents is given by

and for voltages by

. Since for the constant current on the

d-axis, the limitation

is imposed, the value

was adopted. For the voltages

uj constraints,

was assumed, and for

vj voltages, equations (24-25) were used to obtain the imposed limitations.

For the speed reference computing, the following gains values are selected: and .

Thus,

Table 2 summarizes the tuning parameters and constraints for both MPC and PI controllers.

Table 2.

Tuning parameters and constraints for controllers of the two cascade structures.

Table 2.

Tuning parameters and constraints for controllers of the two cascade structures.

| Controller |

Parameter |

Current loops |

Speed loop

(m)

|

| j=d |

j=q |

| MPC |

δj/m |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

| λj/m |

10-5

|

3∙10-5

|

2∙10-5

|

| hpj/m |

40 |

40 |

20 |

| hcj/m |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| uj/mmin/max |

-/+112.58V

|

-/+356.51V |

- /+9.98A |

| vjmin/max |

-/+237.99V

|

-/+78.75V |

- |

| id/qmin/max |

0/4.75 |

-/+9.98A |

- |

| Vj/mmin |

0A |

0A |

0rad/sec |

| Vj/mmax |

1A |

1A |

1rad/sec |

|

105

|

105

|

105

|

| ZC-PI |

Kpj/m |

4.05 |

1.34 |

0.51 |

| Kij/m |

78.41 |

91.09 |

0.21 |

| vjmin/max |

-/+237.99V |

-/+78.75V |

- |

| ummin/max |

- |

- |

- /+9.98A |

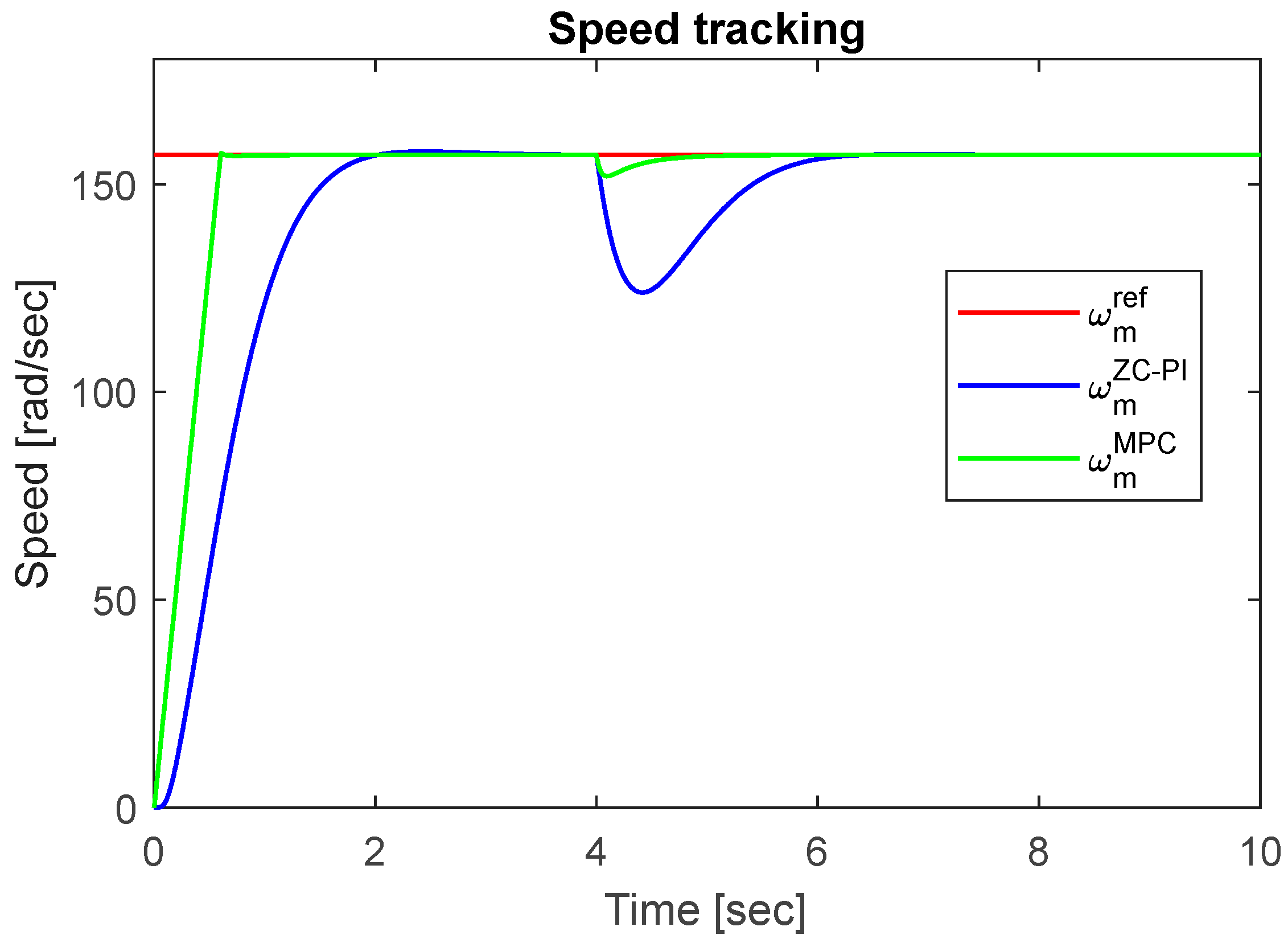

The outer speed loop tracking results for both MPC and ZC-PI controllers of SynRM cascade structure are depicted in

Figure 4. The speed reference is set at a constant value that corresponds to the nominal one

. A no-load start of SynRM is considered, and then, after

4 sec a load torque of value

is applied (

Figure 6), which represents the main disturbance that acts on SynRM. As it can be seen in

Figure 4, for the MPC control is obtained the settling time

, which is much smaller than the settling time

achieved with ZC-PI control. Additionally, ZC-PI speed control response has a very small overshoot, while MPC speed control has no overshoot.

Figure 4.

The speed tracking results.

Figure 4.

The speed tracking results.

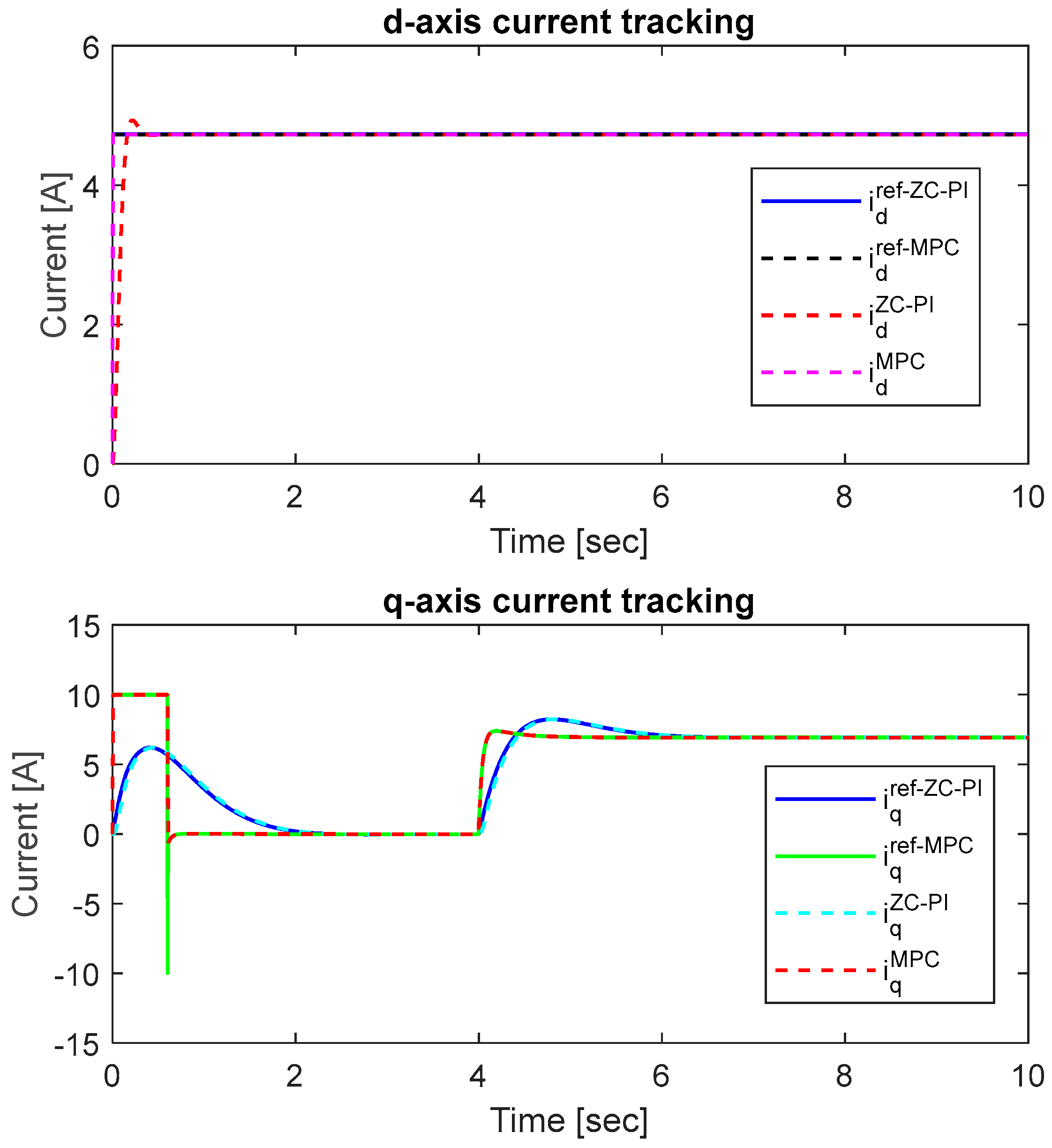

Moreover, when the load torque is applied, the speed variations are much higher with ZC-PI control compared to MPC. It can be mentioned, that on the no-load start conditions of SynRM, the fast outer speed closed loop dynamics with MPCω generates a high value of the controller output, which will be limited by the imposed constraints. The same limitation is also applied as

q-axis current reference. Therefore, the current references and their tracking, which are presented in

Figure 5 have a major influence of SynRM operation.

Figure 5.

The inner current loop tracking results.

Figure 5.

The inner current loop tracking results.

The currents constraints are established according to

Table 2. For

d-axis, the MPC current response

is faster than the corresponding ZC-PI one

. Moreover, compared with ZC-PI current response

, the MPC current response presents no overshoot. On the

q-axis, both current responses,

and

, must track their current references

which are provided by the speed controller. At the start of SynRM drive, the

q-axis MPC current response has a larger value than the ZC-PI one and is limited by the constraints. When the load torque is applied (

Figure 6), the response

is faster than the ZC-PI one

, and both responses present small overshoots.

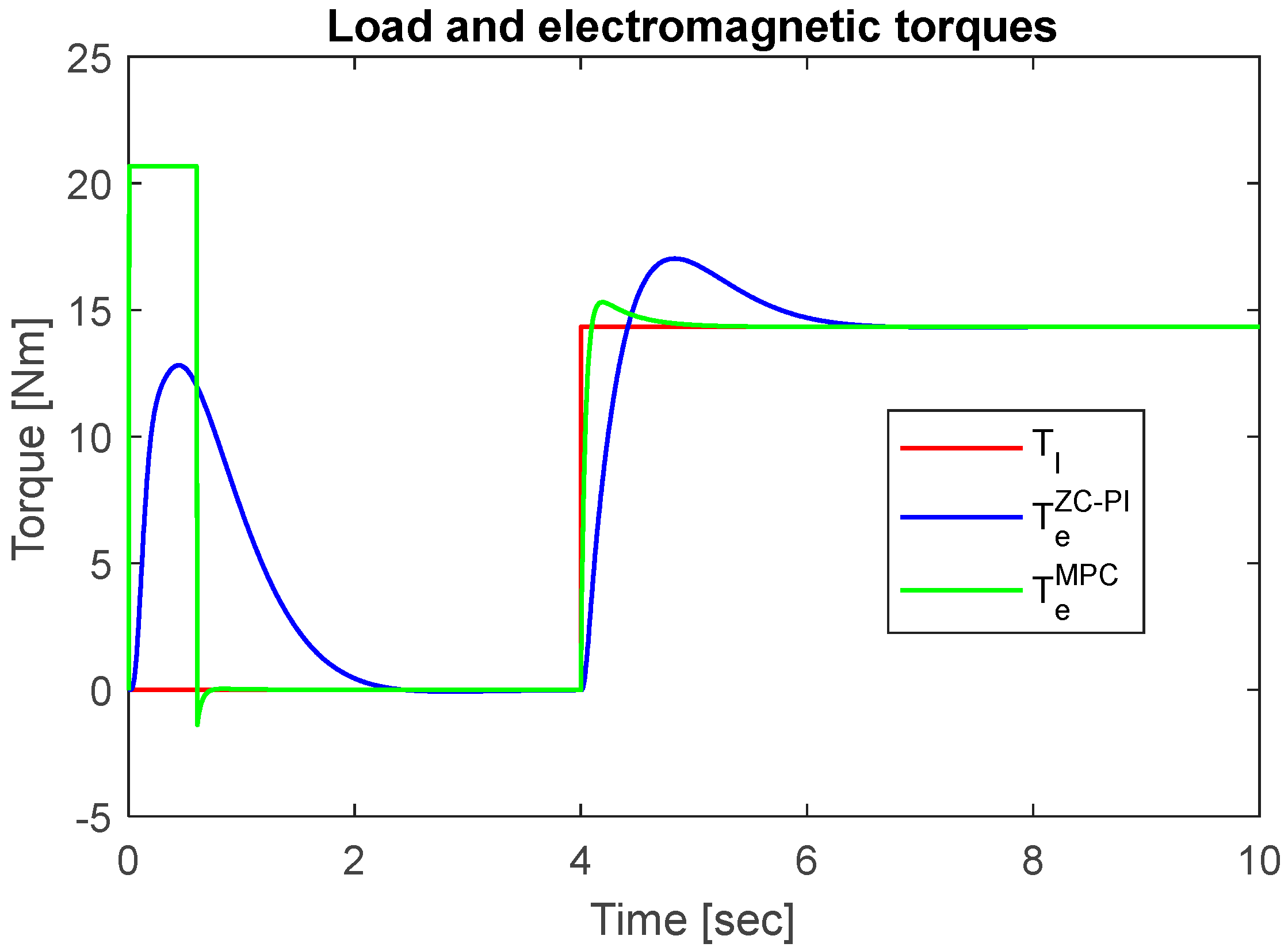

The electromagnetic and load torques are illustrated

Figure 6. As a constant

d-axis current control was chosen, the electromagnetic torque depends linearly on the

q-axis current. Thus, for the no-load start conditions, when

q-axis current of the MPC structure has its maximum value imposed by the constraints, the electromagnetic torque

presents a higher value in comparison with the one obtained by ZC-PI controller

, which will lead to a smaller settling time. When the load torque is applied, a faster response of the electromagnetic torque related to the MPC structure is obtained, with a faster load rejection.

Figure 6.

The electromagnetic and load torques.

Figure 6.

The electromagnetic and load torques.

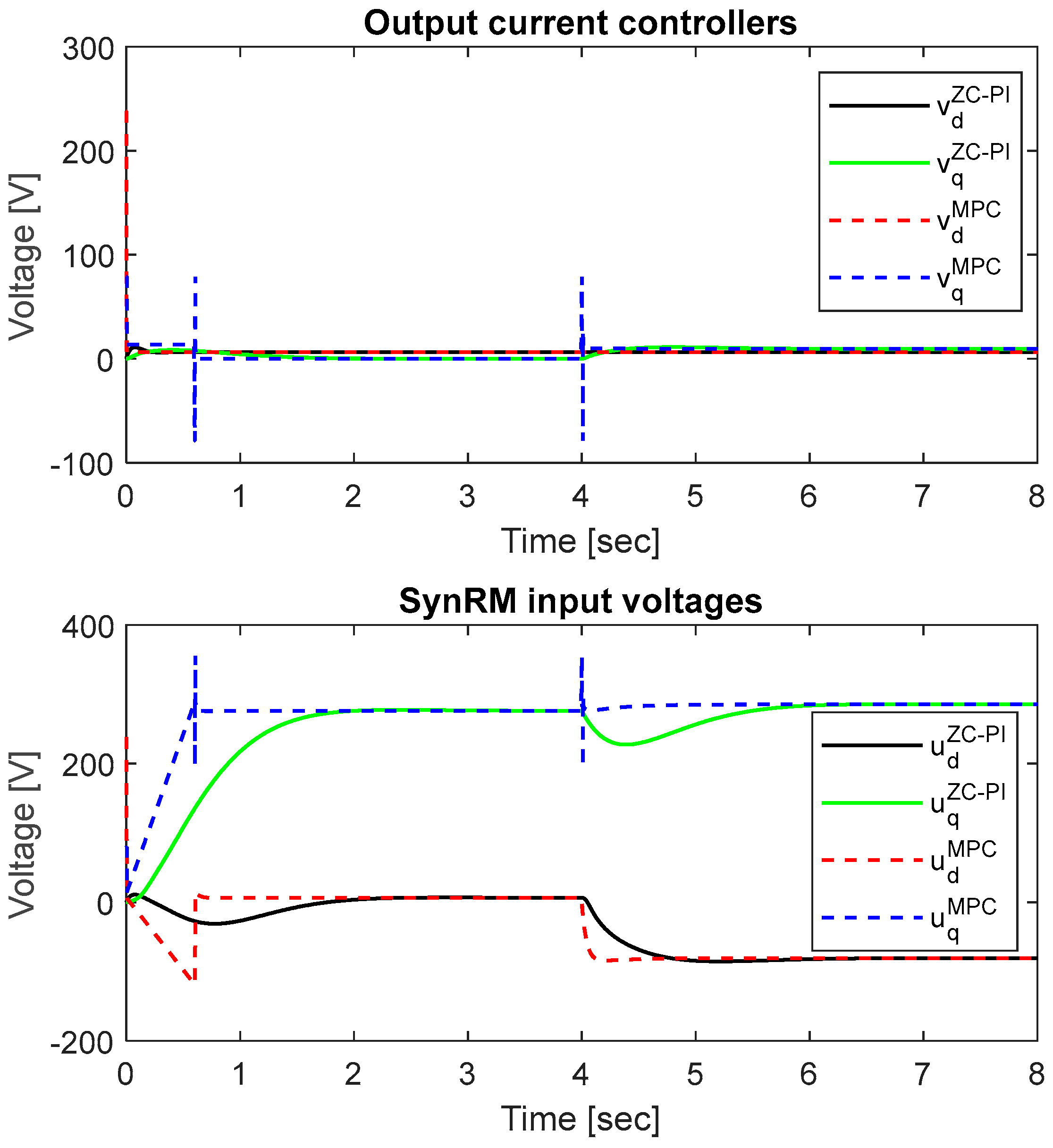

The output current controllers and the input voltages of SynRM

dq model are illustrated in

Figure 7.

The MPC

d/q controller outputs

are limited by the adopted constraints from

Table 2. However, in comparison with the ZC-PI controller outputs

, the MPC controller outputs

present high variation components that are limited by the imposed constraints. Taking into account (23-24), the input voltages of SynRM

dq model

and

depend on the controller outputs

and

, and on current limitations via the feedforward decoupling voltages. Therefore, by current controller outputs constraints, the input voltages of SynRM

dq model are limited.

Figure 7.

The output of the current controllers and the input voltages of SynRM dq model.

Figure 7.

The output of the current controllers and the input voltages of SynRM dq model.

Finally, it can be concluded that the MPC algorithms with related constraints used in the FOC cascade control structure improve the dynamic performances in comparison with the classical PI control.