Submitted:

13 May 2023

Posted:

15 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Dataset

2.2. Data processing

2.3. Statistical methods

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive statistics

3.2. Demographics

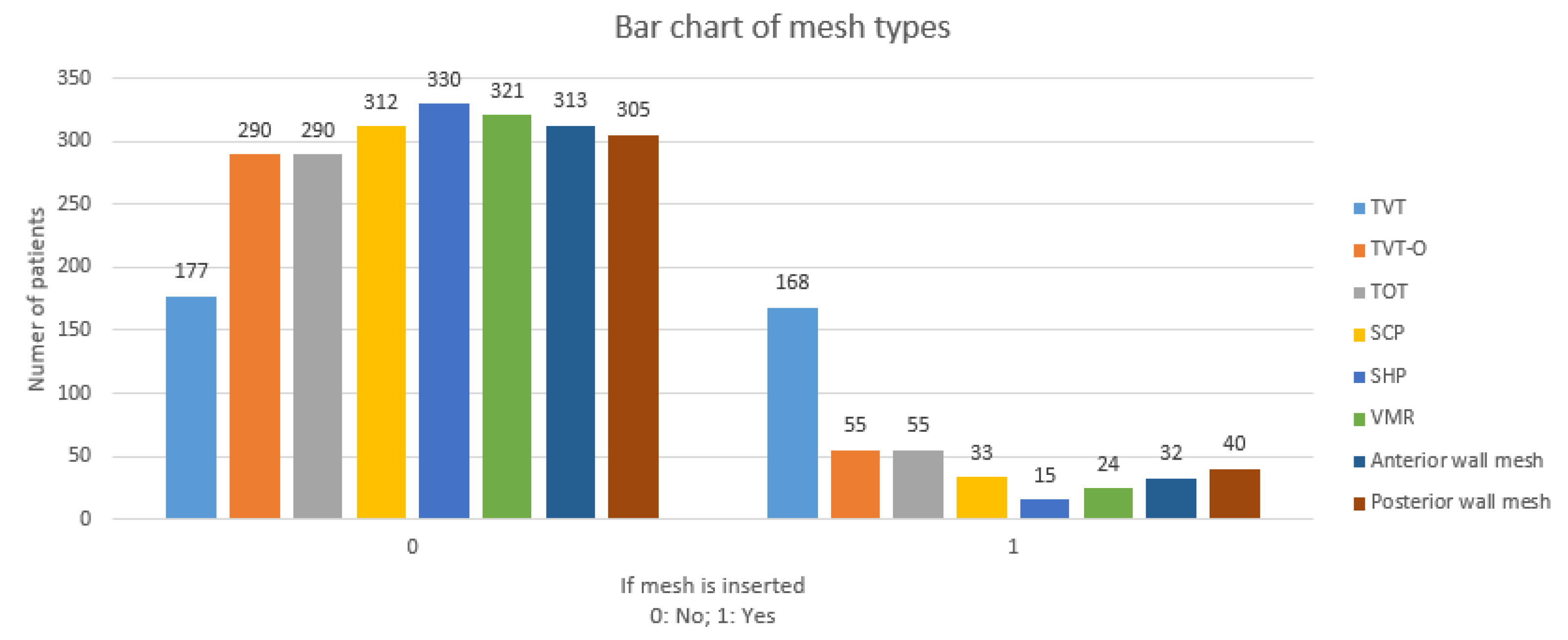

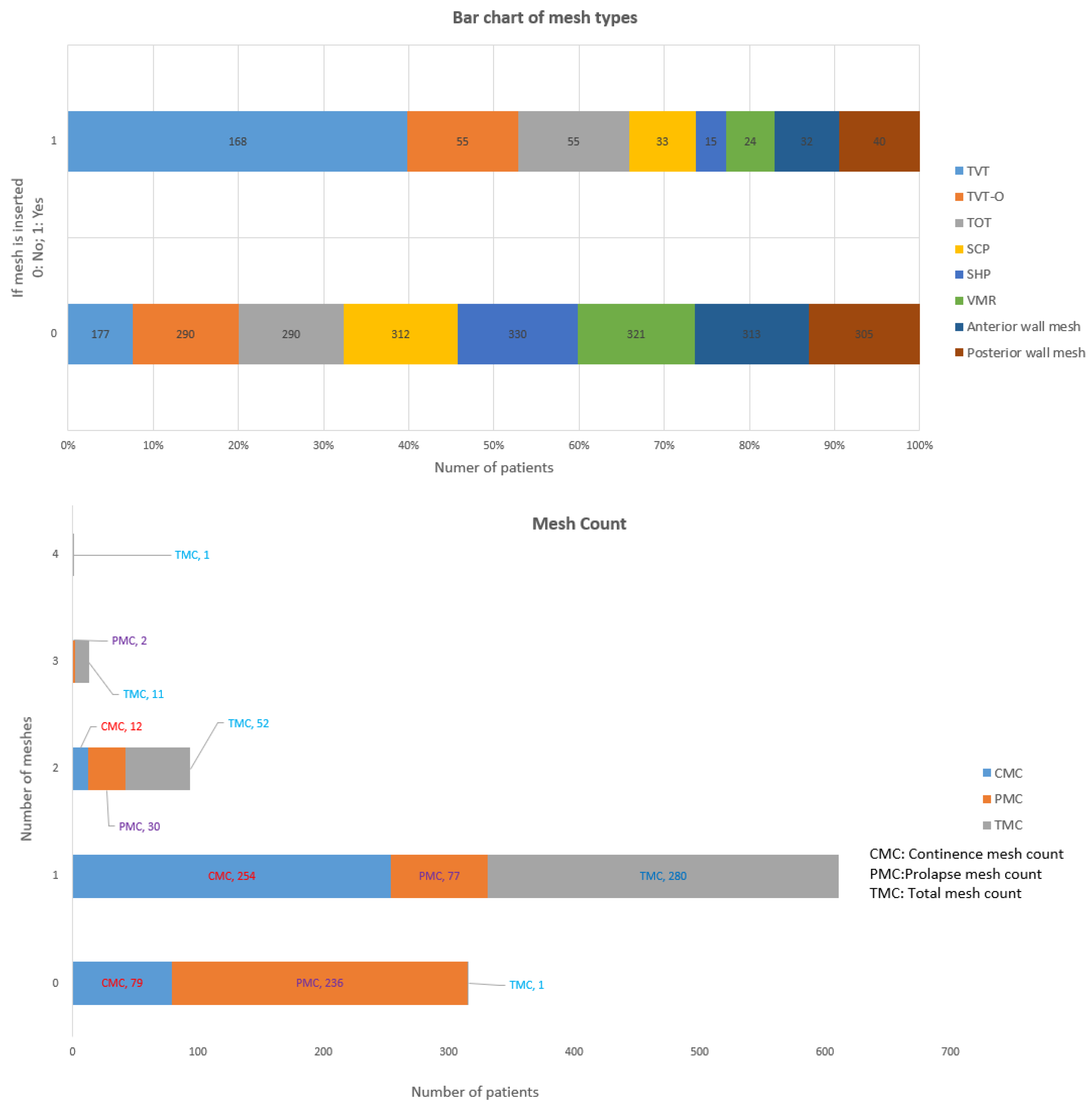

3.3. Mesh Types

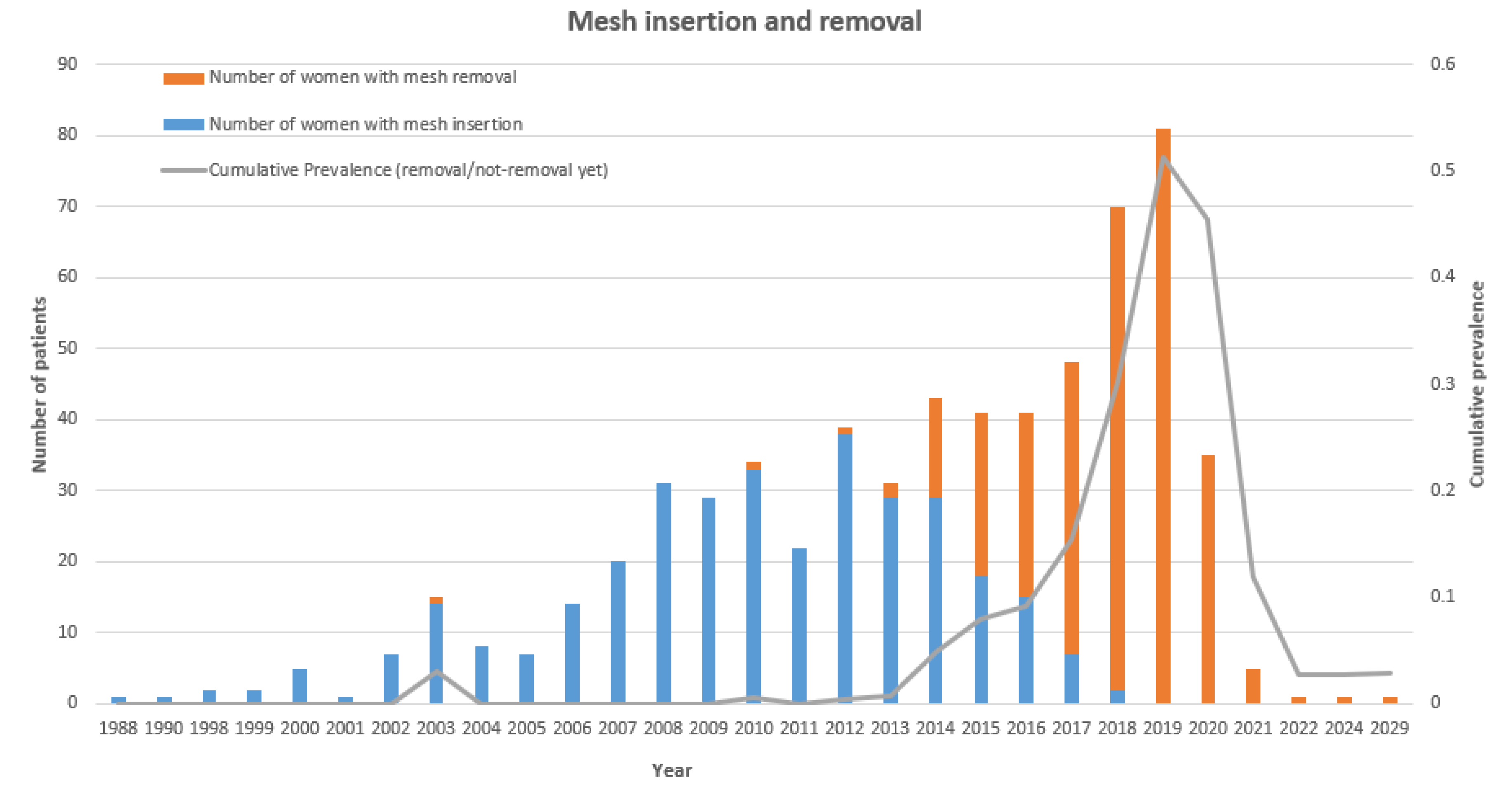

3.4. Prevalence and Incidence

3.5. Data modelling

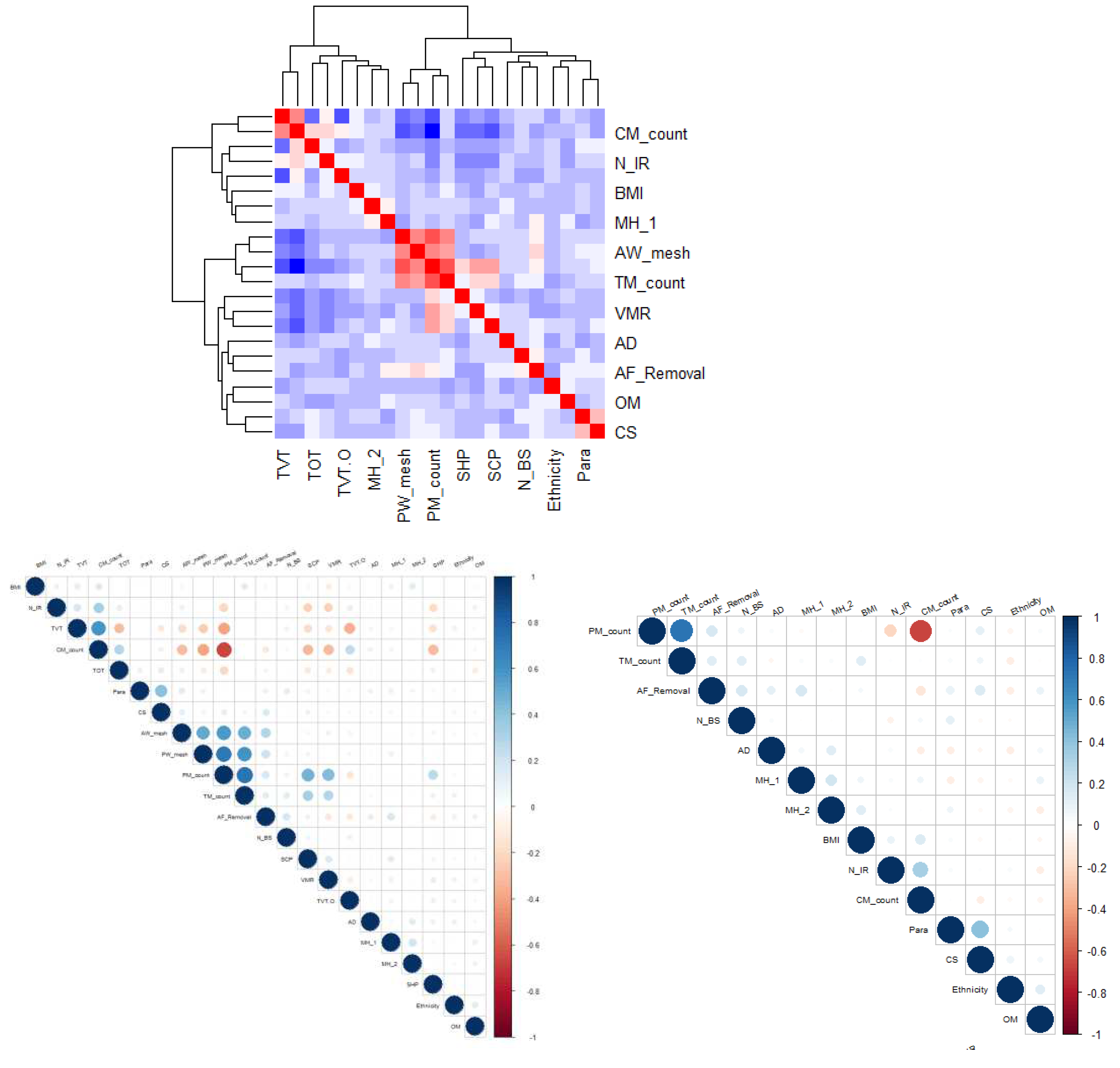

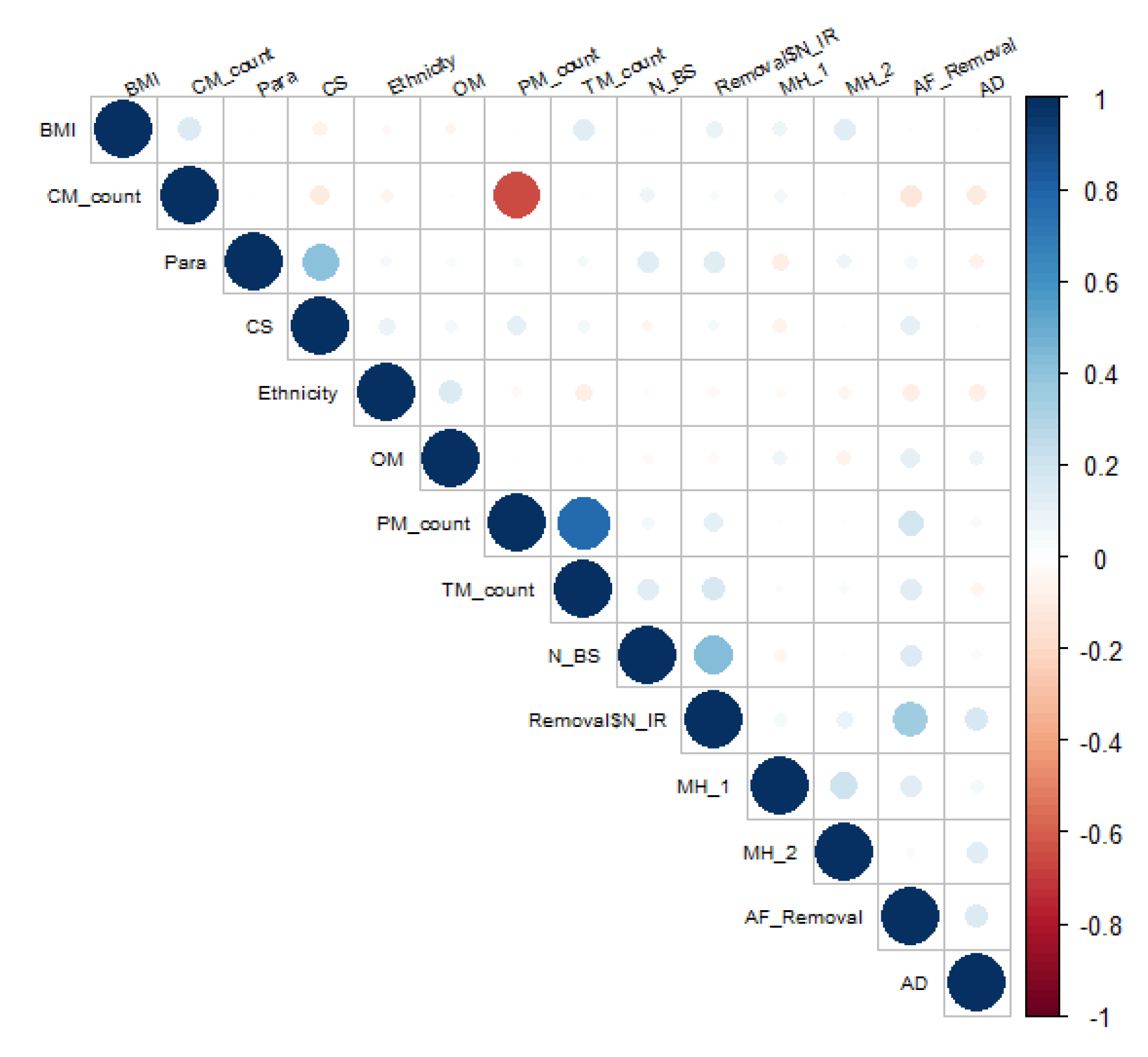

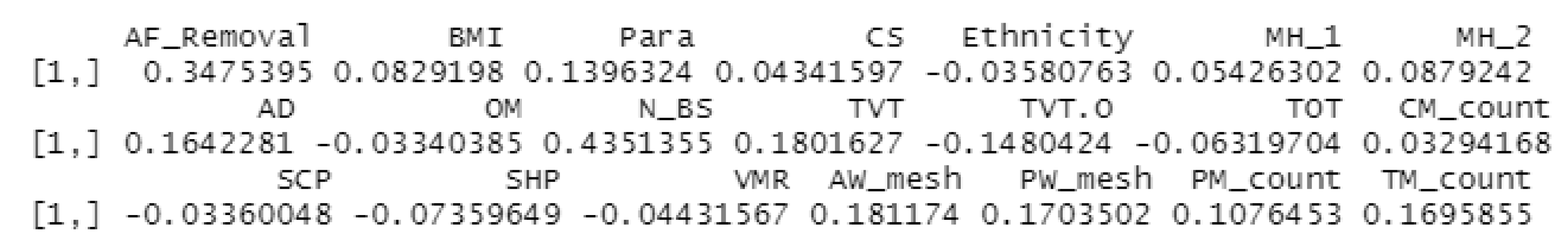

3.5.1. Correlation:

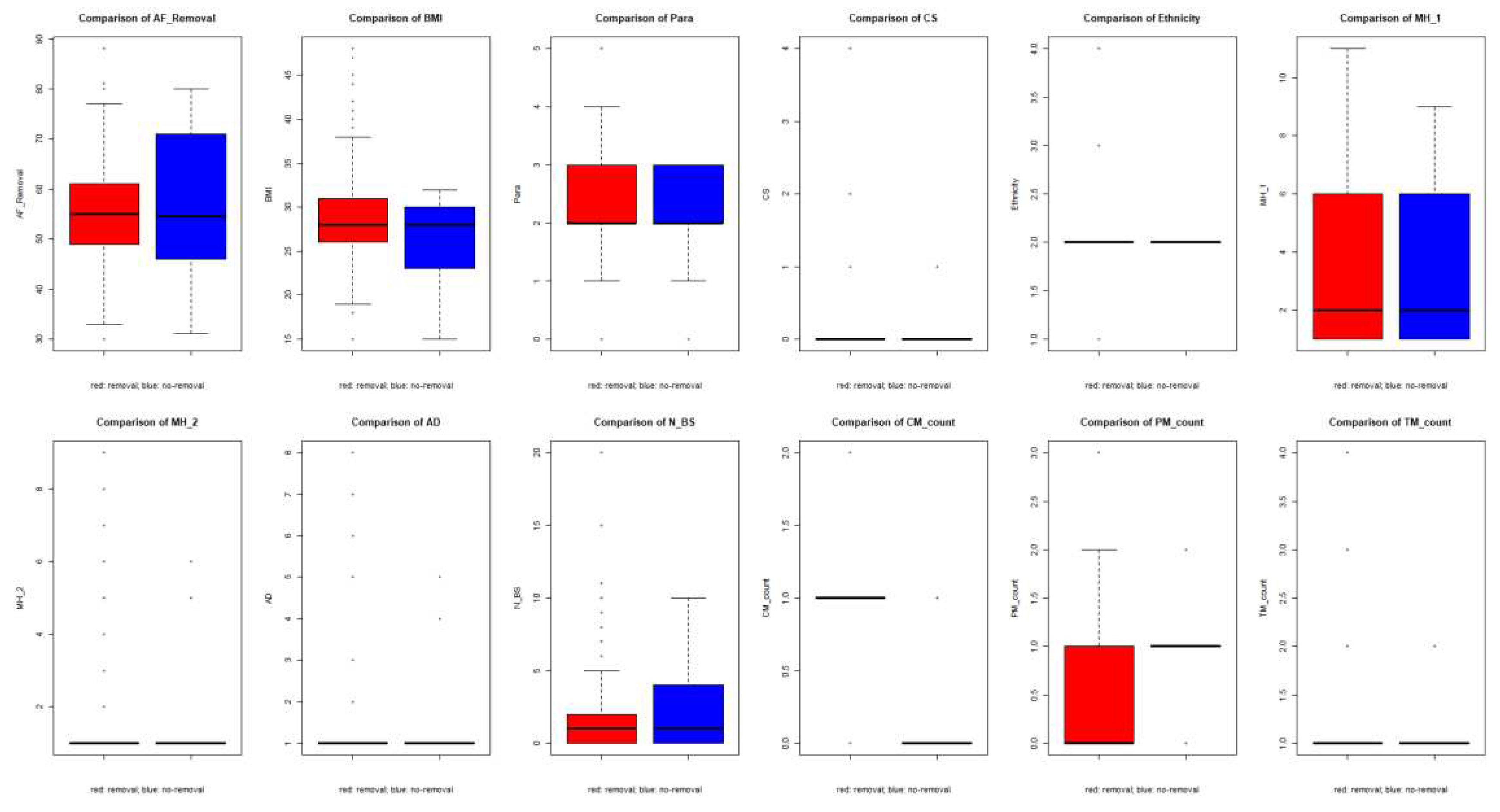

3.5.2. Group comparison

4. DISCUSSION

5. CONCLUSIONS

Author Contributions

Funding

Availability of data and material

Code availability

Ethics approval

Consent to participate

Consent for publication

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slack, M. and C. Mayne, Scientific Impact Paper No. 19: The Use of Mesh in Gynaecological Surgery, in Scientific Impact Paper. 2010, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

- Sangster, P. and R. Morley, Biomaterials in urinary incontinence and treatment of their complications. Indian J Urol, 2010. 26(2): p. 221-9. [CrossRef]

- Amid, P.K., Classification of biomaterials and their related complications in abdominal wall hernia surgery. Hernia, 1997. 1(1): p. 15 - 21.

- Callesen, T., K. Bech, and H. Kehlet, Prospective study of chronic pain after groin hernia repair. Br J Surg, 1999. 86(12): p. 1528-31.

- Abed, H., et al., Incidence and management of graft erosion, wound granulation, and dyspareunia following vaginal prolapse repair with graft materials: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J, 2011. 22(7): p. 789-98. [CrossRef]

- Blaivas, J.G., et al., Safety considerations for synthetic sling surgery. Nat Rev Urol, 2015. 12(9): p. 481-509. [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.N. and G.H. Badlani, Mesh complications in female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery and their management: A systematic review. Indian J Urol, 2012. 28(2): p. 129-53. [CrossRef]

- Ellington, D.R. and H.E. Richter, Indications, contraindications, and complications of mesh in surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Clin Obstet Gynecol, 2013. 56(2): p. 276-88. [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, E.A. and R.A. Appell, Management of complications arising from transvaginal mesh kit procedures: a tertiary referral center's experience. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct, 2009. 20(1): p. 11-7. [CrossRef]

- Administration, U.S.F.a.D. FDA Safety Communication: UPDATE on Serious Complications Associated with Transvaginal Placement of Surgical Mesh for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Public Health Notification, 2011.

- Diwadkar, G.B., et al., Complication and reoperation rates after apical vaginal prolapse surgical repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol, 2009. 113(2 Pt 1): p. 367-73.

- Feiner, B., J.E. Jelovsek, and C. Maher, Efficacy and safety of transvaginal mesh kits in the treatment of prolapse of the vaginal apex: a systematic review. BJOG, 2009. 116(1): p. 15-24. [CrossRef]

- Heneghan, C.J., et al., Trials of transvaginal mesh devices for pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic database review of the US FDA approval process. BMJ Open, 2017. 7(12): p. e017125. [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, C.A., H. Bruschini, and D.J. Cody, Traditional suburethral sling operations for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2005(3): p. CD001754.

- Tellez Martinez-Fornes, M., et al., A three year follow-up of a prospective open randomized trial to compare tension-free vaginal tape with Burch colposuspension for treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Actas Urol Esp, 2009. 33(10): p. 1088-96.

- Haskell, H., Cumberlege review exposes stubborn and dangerous flaws in healthcare. BMJ, 2020. 370: p. m3099. [CrossRef]

- Gyang, A.N., et al., Managing chronic pelvic pain following reconstructive pelvic surgery with transvaginal mesh. Int Urogynecol J, 2014. 25(3): p. 313-8. [CrossRef]

- Danford, J.M., et al., Postoperative pain outcomes after transvaginal mesh revision. Int Urogynecol J, 2015. 26(1): p. 65-9. [CrossRef]

- Marcus-Braun, N., A. Bourret, and P. von Theobald, Persistent pelvic pain following transvaginal mesh surgery: a cause for mesh removal. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2012. 162(2): p. 224-8. [CrossRef]

- Castellanos ME, et al., Pudendal Neuralgia after Posterior Vaginal Wall Repair with Mesh Kits: An Anatomical Study and Case Series. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, 2012. 19(6): p. S72-S73. [CrossRef]

- Barski, D. and D.Y. Deng, Management of Mesh Complications after SUI and POP Repair: Review and Analysis of the Current Literature. Biomed Res Int, 2015. 2015: p. 831285. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.L., et al., Dyspareunia and chronic pelvic pain after polypropylene mesh augmentation for transvaginal repair of anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct, 2007. 18(6): p. 675-8. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, G.E., et al., Changed women: the long-term impact of vaginal mesh complications. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg, 2014. 20(3): p. 131-6.

- Basu, M. and J.R. Duckett, Barriers to seeking treatment for women with persistent or recurrent symptoms in urogynaecology. BJOG, 2009. 116(5): p. 726-30. [CrossRef]

- Jacquetin, B., [Use of "TVT" in surgery for female urinary incontinence]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris), 2000. 29(3): p. 242-7.

- Nicita, G., A new operation for genitourinary prolapse. J Urol, 1998. 160(3 Pt 1): p. 741-5.

- Powell, J.L. and D.B. Joseph, Abdominal sacral colpopexy for massive genital prolapse. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns, 1998. 5(4): p. 201. [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.M., K. Ogan, and S. Bennett, Antibacterial mesh sling: a prospective outcome analysis. Urology, 2000. 55(4): p. 515-20. [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, P., et al., United States experience with tension-free vaginal tape procedure for urinary stress incontinence: assessment of safety and tolerability. Tech Urol, 2001. 7(4): p. 261-5.

- Kenne, K.A., L. Wendt, and J. Brooks Jackson, Prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in adult women being seen in a primary care setting and associated risk factors. Sci Rep, 2022. 12(1): p. 9878. [CrossRef]

- Kamisan Atan, I., et al., It is the first birth that does the damage: a cross-sectional study 20 years after delivery. Int Urogynecol J, 2018. 29(11): p. 1637-1643. [CrossRef]

- Ferdinande, K., et al., Anorectal symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum: a prospective cohort study. Colorectal Dis, 2018. 20(12): p. 1109-1116. [CrossRef]

- Ng, K., et al., An observational follow-up study on pelvic floor disorders to 3-5 years after delivery. Int Urogynecol J, 2017. 28(9): p. 1393-1399. [CrossRef]

- Liebergall-Wischnitzer, M., et al., Self-reported Prevalence of and Knowledge About Urinary Incontinence Among Community-Dwelling Israeli Women of Child-Bearing Age. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 2015. 42(4): p. 401-6. [CrossRef]

- Burki, T., Cumberlege Review slams health care in England. Lancet, 2020. 396(10245): p. 156. [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, P., et al., Trends in the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in the UK. Heart, 2016. 102(24): p. 1945-1952. [CrossRef]

- Keltie, K., et al., Complications following vaginal mesh procedures for stress urinary incontinence: an 8 year study of 92,246 women. Sci Rep, 2017. 7(1): p. 12015. [CrossRef]

- Kent, S., et al., Common Problems, Common Data Model Solutions: Evidence Generation for Health Technology Assessment. Pharmacoeconomics, 2021. 39(3): p. 275-285. [CrossRef]

- Zilberlicht, A., et al., Counseling for stress urinary incontinence in the era of adverse publicity around mesh usage: Results from a large-sample global survey. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2023. 160(2): p. 579-587. [CrossRef]

- Motamedi, M., S.M. Carter, and C. Degeling, Transvaginal mesh in Australia: An analysis of news media reporting from 1996 to 2021. Health Expect, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hengel, B., B. Welk, and R.J. Baverstock, Medicolegal basics and update on transvaginal mesh in Canada. Can Urol Assoc J, 2017. 11(6Suppl2): p. S108-S111. [CrossRef]

- https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3A%2F%2Fid.who.int%2Ficd%2Fentity%2F69547070.

- https://digital.nhs.uk/news/2018/nhs-digital-publishes-statistics-on-vaginal-mesh-procedures.

- https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey-survey-of-mental-health-and-wellbeing-england-2014.

| Terminology | Definition used for the statistical analysis | Abbreviation used |

|---|---|---|

| Age at first surgery (removal) | Patient's age at the first mesh removal surgery | AF Removal |

| BMI | Body Mass Index | BMI |

| Para | Number of deliveries (vaginal + caesarean) | Para |

| Caesarean Section | CS | |

| 3/4-degree tear | Obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI) | OASI |

| FD/VO | Forceps Deliver or Ventouse Delivery | FD/VO |

| Ethnicity | 1: Caucasian 2: Asian 3: African | Ethnicity |

| Medical History 1 | A full-scale medical history for potential complications: | MH_1 |

| Medical History 2 | 1fybromialgia 2diabetes 3 Other Endocrine 4 Autoimmune 5 Psychiatric 6 IBS 7 Cardiovascular 8 COPD/Asthma 9 Neuro 10 Disc Prolapse | MH_2 |

| Autoimmune disorder | 1 Spondylitis 2 Rheumatic Arthritis 3 EDS 4 Joint Hypermobility 5 Positive Auto-AB 6 Osteoarthrosis 7 Psoriasis/Psoriasis Arthritis | AD |

| Other medical | Other co-morbidity not defined specifically | OM |

| Year first mesh insertion | Specific year for the first mesh insertion surgery | YFMI |

| N years beginning of symptoms | Number of years for beginning of certain symptoms | N_BS |

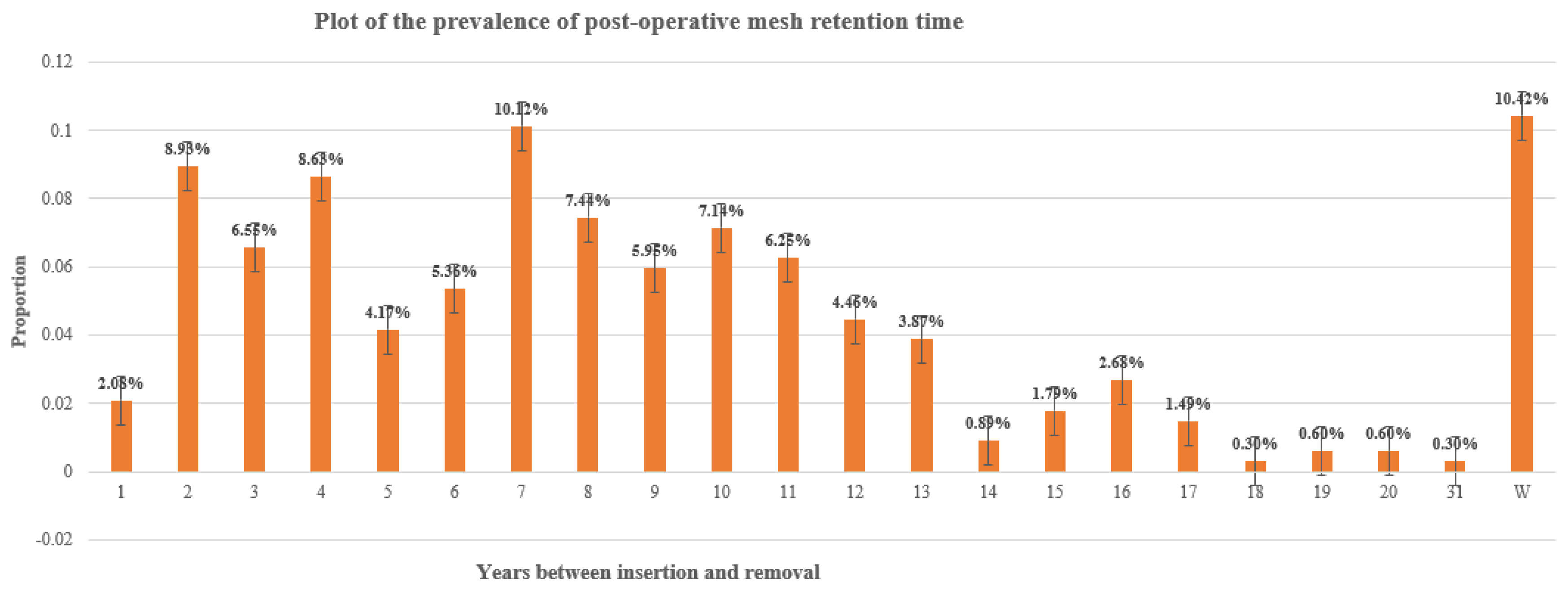

| N years insertion-removal | Time interval between mesh insertion and removal surgery | N_IR |

| TVT | Tension free vaginal tape | TVT |

| TVT-O | Trans-obturator midurethral sling from inside to outside | TVT-O |

| TOT | Transobturator tape | TOT |

| Continence mesh count | Number of continence meshes, sum of TVT, TVT-O and TOT | CM_count |

| SCP | Sacrocolpopexy | SCP |

| SHP | Sacrohysteropexy | SHP |

| VMR | Ventral rectopexy mesh | VMR |

| Anterior wall mesh | Number of mesh put in Anterior wall | AWM |

| Posterior wall mesh | Number of mesh put in Posterior wall | PWM |

| Prolapse mesh count | Number of Prolapse meshes, sum of SCP, SHP, VMR, Anterior and Posterior wall mesh | PM_count |

| Total mesh count | Total number of meshes inserted, sum of Continence meshes and Prolapse meshes | TM_count |

| Age at first surgery (removal) | (0,40] | (40,60] | (60,75] | (75,90] | Blank |

| 25 | 187 | 78 | 14 | 41 | |

| 7.25% | 54.20% | 22.61% | 4.06% | 11.88% | |

| BMI | BMI<30 | BMI<40 | BMI>=40 | Unclear | Blank |

| 189 | 90 | 17 | 4 | 45 | |

| 54.8% | 26.1% | 4.9% | 1.2% | 13.0% | |

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | Asian | African | Unclear | Blank |

| 310 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 14 | |

| 89.9% | 2.6% | 1.2% | 2.3% | 4.1% |

| Para | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | >=4 | Blank |

| 12 | 31 | 142 | 78 | 22 | 60 | |

| 3.5% | 9.0% | 41.2% | 22.6% | 6.4% | 17.4% | |

| CS | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Blank |

| 267 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 56 | |

| 77.4% | 5.2% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 16.2% | |

| N years beginning of symptoms | 0 | [1,5] | [6,10] | [10,15] | >=16 | Blank |

| 121 | 158 | 26 | 3 | 1 | 36 | |

| 35.1% | 45.8% | 7.5% | 0.9% | 0.3% | 10.4% | |

| N Years insertion-removal | W | [1,5] | [6,10] | [10,15] | >=16 | Blank |

| 35 | 102 | 121 | 58 | 20 | 9 | |

| 10.1% | 29.6% | 35.1% | 16.8% | 5.8% | 2.6% |

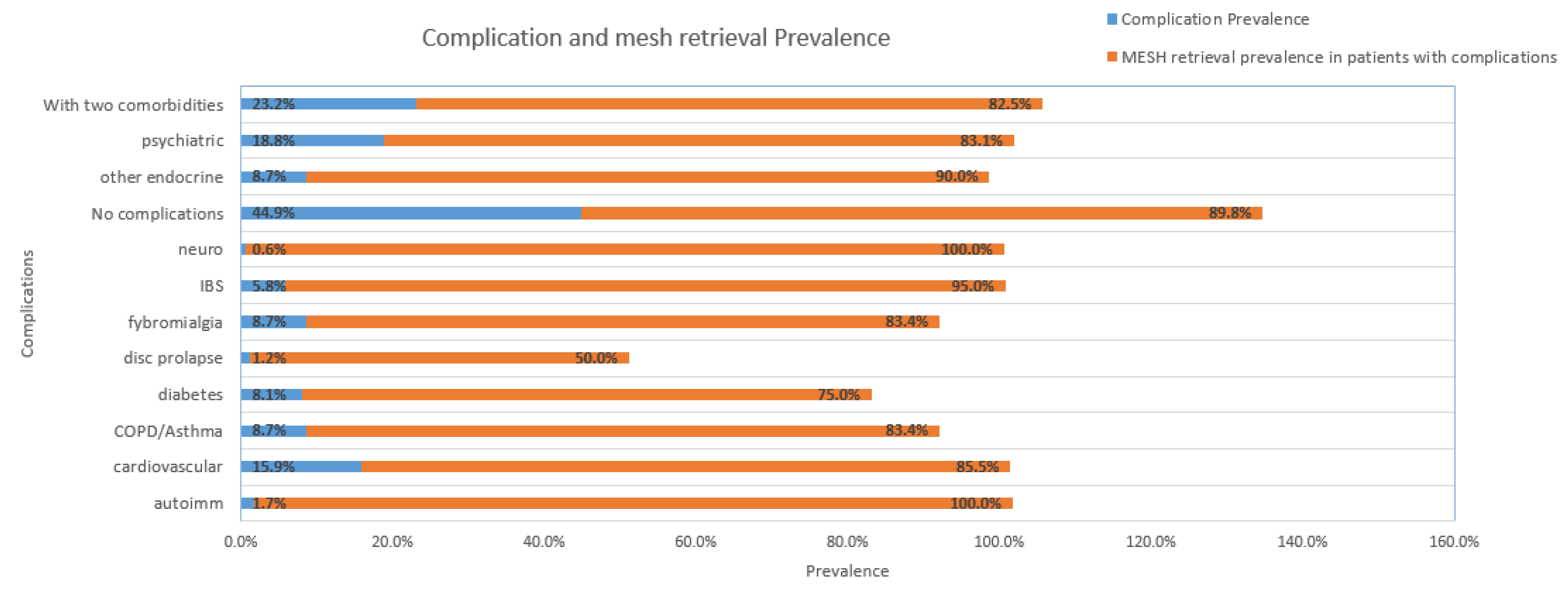

| Complications (C) | History 1 | History 2 | Count | Prevalence (C) | Retrieval prevalence in patients with (C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No complications | 155 | 265 | 420 | 44.93% | 89.8% |

| >2 comorbidities | 80 | 80 | 80 | 23.19% | 82.5% |

| Psychiatric | 43 | 22 | 65 | 18.84% | 83.1% |

| Cardiovascular | 42 | 13 | 55 | 15.94% | 85.5% |

| Fibromyalgia | 30 | 0 | 30 | 8.70% | 83.4% |

| Other endocrine | 20 | 10 | 30 | 8.70% | 90% |

| Diabetes | 19 | 9 | 28 | 8.12% | 75.0% |

| COPD/asthma | 15 | 15 | 30 | 8.70% | 83.4% |

| IBS | 12 | 8 | 20 | 5.80% | 95% |

| Autoimmune | 5 | 1 | 6 | 1.74% | 100% |

| Neurological | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.58% | 100% |

| Disc prolapse | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1.16% | 50% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).