Submitted:

10 May 2023

Posted:

12 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

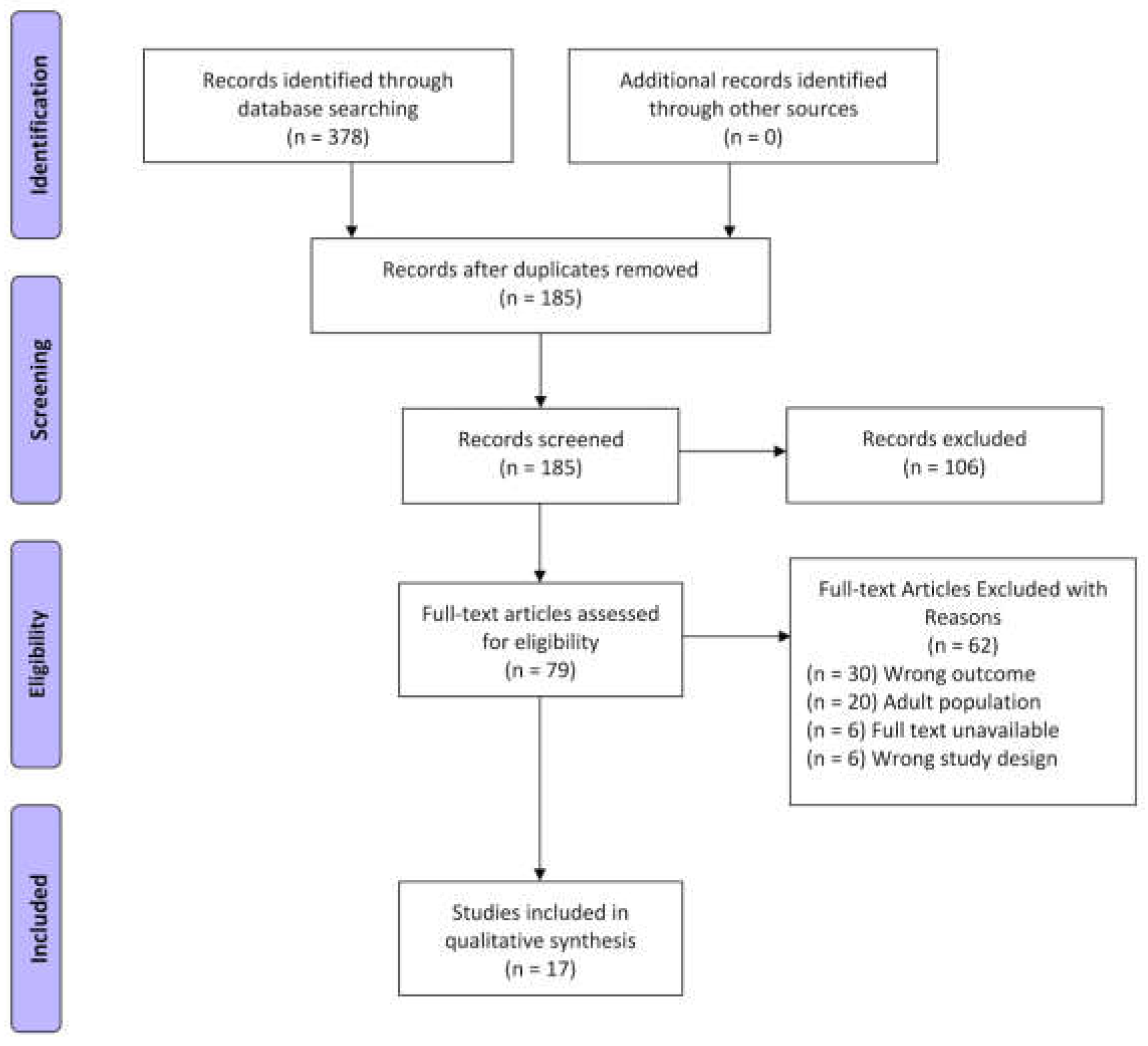

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Operational Definitions

2.2. Article Search Strategy

2.3. Study Inclusion and Exclusion

2.4. Study Selection and Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample

3.2. Study Characteristics

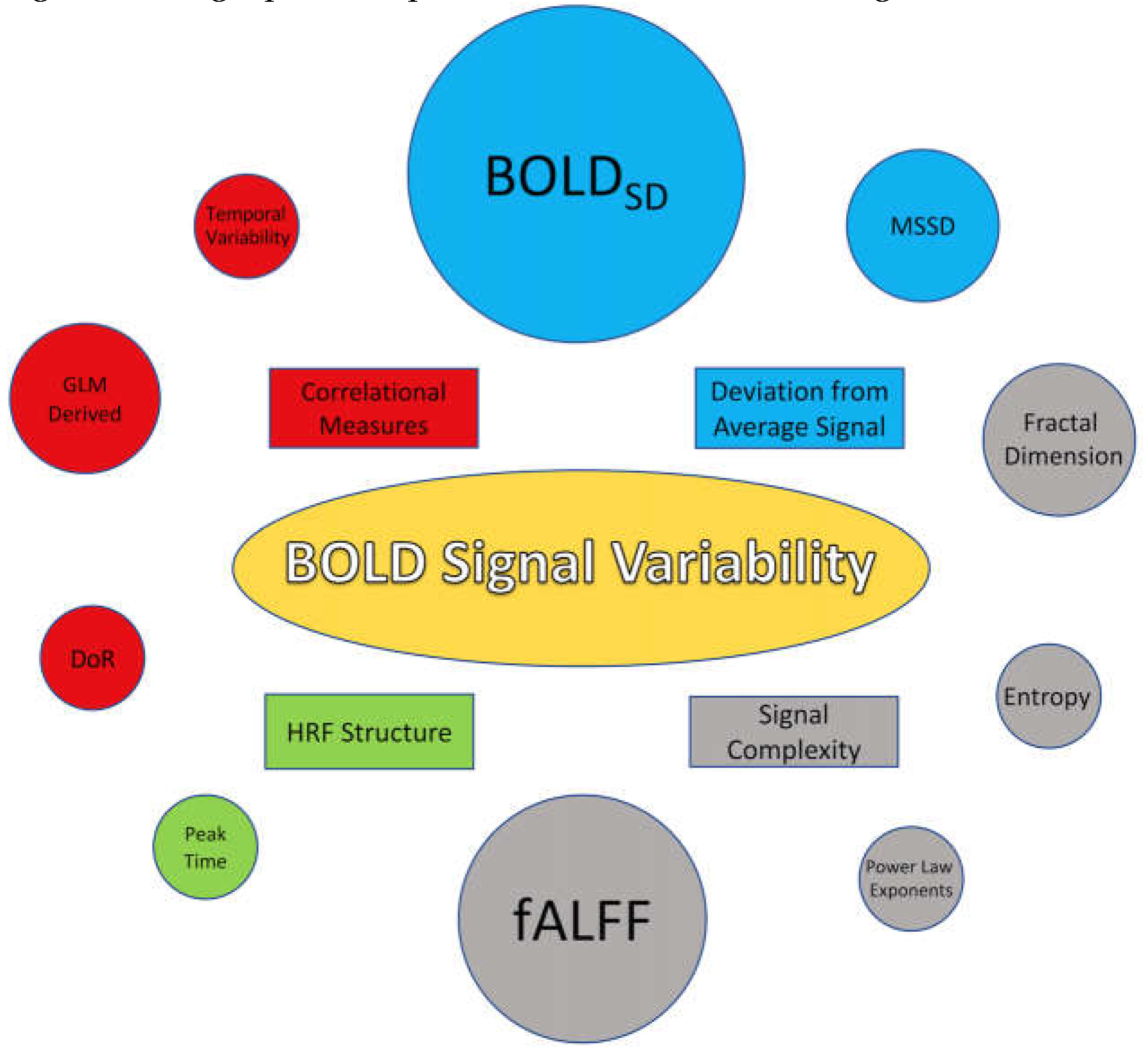

3.3. BOLD SV Metrics (stopped editing here)

3.4. Findings Associated with Deviation from the Average BOLD Signal

3.4.1. Standard Deviation of the BOLD Signal (BOLDSD)

3.4.2. Mean Successive Squared Difference (MSSD)

3.5. Findings Associated with Correlational Measures of BOLD SV

3.5.1. Temporal Variability

3.5.2. Multilinear and GLM Derived Variance Measurement

3.5.3. Difference of Residuals

3.6. Findings Associated with Signal Complexity

3.6.1. Entropy/Sample Entropy

3.6.2. Fractal Dimensionality

3.6.3. Power Based Metrics

3.6.4. Fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (fALFF)

3.7. Findings Associated with Characteristics of the Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF)

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.1.1. Metrics

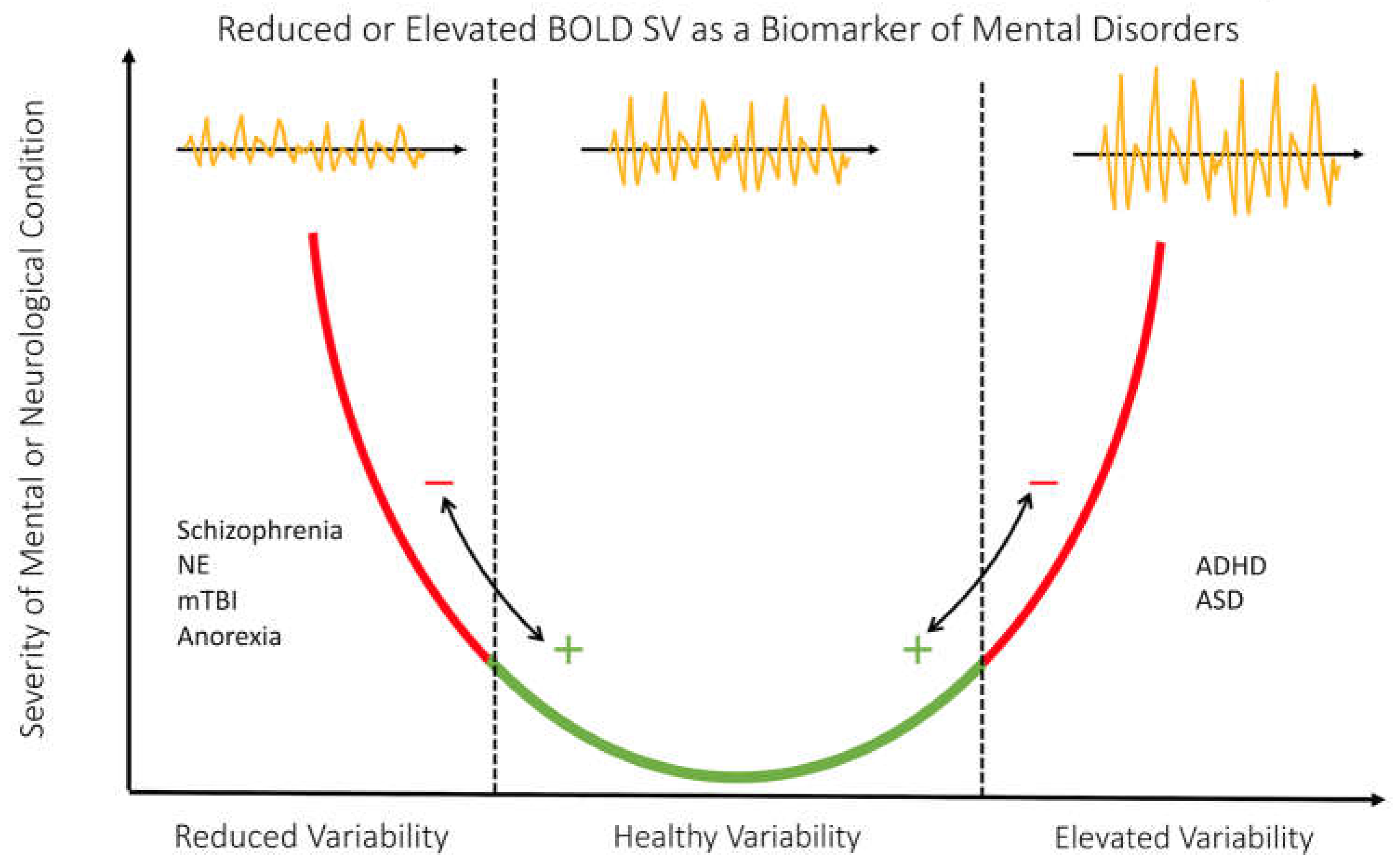

4.1.2. The Inverted U Trend and BOLD SV

4.1.3. BOLD SV Trends in Mental and Neurological Conditions

4.1.3. Recommendations for Clinical Applications:

4.2. Future Directions and Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Protocol Registration

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix Table.2.

References

- Bray, S. Age-associated patterns in gray matter volume, cerebral perfusion and BOLD oscillations in children and adolescents. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 2398–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easson AK, McIntosh AR. BOLD signal variability and complexity in children and adolescents with and without autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2019, 36, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson A, Schel MA, Steinbeis N. Changes in BOLD variability are linked to the development of variable response inhibition. Neuroimage 2021, 228, 117691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts RP, Grady CL, Addis DR. Creative, internally-directed cognition is associated with reduced BOLD variability. NeuroImage. 2020, 219, 116758.. [CrossRef]

- Zöller D, Schaer M, Scariati E, Padula MC, Eliez S, Van De Ville D. Disentangling resting-state BOLD variability and PCC functional connectivity in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Neuroimage. 2017, 149, 85–97.. [CrossRef]

- Malins JG, Pugh KR, Buis B, et al. Individual Differences in Reading Skill Are Related to Trial-by-Trial Neural Activation Variability in the Reading Network. J. Neurosci 2018, 38, 2981–2989. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomi JS, Bolt TS, Ezie CEC, Uddin LQ, Heller AS. Moment-to-Moment BOLD Signal Variability Reflects Regional Changes in Neural Flexibility across the Lifespan. J. Neurosci 2017, 37, 5539–5548. [CrossRef]

- Mulligan RC, Kristjansson SD, Reiersen AM, Parra AS, Anokhin AP. Neural correlates of inhibitory control and functional genetic variation in the dopamine D4 receptor gene. Neuropsychologia 2014, 62, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Cheng W, Liu Z, et al. Neural, electrophysiological and anatomical basis of brain-network variability and its characteristic changes in mental disorders. Brain 2016, 139, 2307–2321. 2321. [CrossRef]

- Zöller D, Padula MC, Sandini C, et al. Psychotic symptoms influence the development of anterior cingulate BOLD variability in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 193, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dona O, Hall GB, Noseworthy MD. Temporal fractal analysis of the rs-BOLD signal identifies brain abnormalities in autism spectrum disorder. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0190081. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs J, Hawco C, Kobayashi E, et al. Variability of the hemodynamic response as a function of age and frequency of epileptic discharge in children with epilepsy. Neuroimage. 2008, 40, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidel M, Geisler D, Borchardt V, et al. Evaluation of spontaneous regional brain activity in weight-recovered anorexia nervosa. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 395. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 14. Anderson JS, Zielinski BA, Nielsen JA, Ferguson MA. Complexity of low-frequency blood oxygen level-dependent fluctuations covaries with local connectivity. Hum. Brain Mapp 2013, 35, 1273–1283. [CrossRef]

- Dona O, Noseworthy MD, DeMatteo C, Connolly JF. Fractal Analysis of Brain Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent (BOLD) Signals from Children with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169647. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang H, Ghaderi A, Long X, Reynolds JE, Lebel C, Protzner AB. The longitudinal relationship between BOLD signal variability changes and white matter maturation during early childhood. NeuroImage 2021, 242, 118448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 17. Zheng X, Sun J, Lv Y, et al. Frequency-specific alterations of the resting-state BOLD signals in nocturnal enuresis: an fMRI Study. Sci. Rep 2021, 11, 12042. [CrossRef]

- Ke J, Zhang L, Qi R; et al. Altered blood oxygen level-dependent signal variability in chronic post-traumatic stress disorder during symptom provocation. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Zöller D, Padula MC, Sandini C; et al. Psychotic symptoms influence the development of anterior cingulate BOLD variability in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Schizophr. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett DD, Kovacevic N, McIntosh AR, Grady CL. The Importance of Being Variable. J. Neurosci. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett DD, Kovacevic N, McIntosh AR, Grady CL. Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent Signal Variability Is More than Just Noise. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 4914–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spalatro A V., Amianto F, Huang Z; et al. Neuronal variability of Resting State activity in Eating Disorders: Increase and decoupling in Ventral Attention Network and relation with clinical symptoms. Eur. Psychiatry 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomi JS, Schettini E, Voorhies W, Bolt TS, Heller AS, Uddin LQ. Resting-state brain signal variability in prefrontal cortex is associated with ADHD symptom severity in children. Front. Human. Neurosci. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Pur DR, Eagleson RA, de Ribaupierre A, Mella N, de Ribaupierre S. Moderating Effect of Cortical Thickness on BOLD Signal Variability Age-Related Changes. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Nomi JS, Bolt TS, Ezie CEC, Uddin LQ, Heller AS. Moment-to-Moment BOLD Signal Variability Reflects Regional Changes in Neural Flexibility across the Lifespan. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 5539–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson A, Schel MA, Steinbeis N. Changes in BOLD variability are linked to the development of variable response inhibition. Neuroimage 2021, 228, 117691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett DD, Samanez-Larkin GR, MacDonald SWS, Lindenberger U, McIntosh AR, Grady CL. Moment-to-moment brain signal variability: A next frontier in human brain mapping? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Ghaderi A, Long X, Reynolds JEE, Lebel C, Protzner ABB. The longitudinal relationship between BOLD signal variability changes and white matter maturation during early childhood. NeuroImage 2021, 242, 118448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou QH, Zhu CZ, Yang Y; et al. An improved approach to detection of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) for resting-state fMRI: Fractional ALFF. J. Neurosci. Methods 2008, 172, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1998, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easson AK, McIntosh AR. BOLD signal variability and complexity in children and adolescents with and without autism spectrum disorder. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2019, 36, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts RP, Grady CL, Addis DR. Creative, internally-directed cognition is associated with reduced BOLD variability. NeuroImage 2020, 219, 116758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zöller D, Padula MC, Sandini C; et al. Psychotic symptoms influence the development of anterior cingulate BOLD variability in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 193, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zöller D, Schaer M, Scariati E, Padula MC, Eliez S, Van De Ville D. Disentangling resting-state BOLD variability and PCC functional connectivity in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Neuroimage 2017, 149, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel M, Geisler D, Borchardt V; et al. Evaluation of spontaneous regional brain activity in weight-recovered anorexia nervosa. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Ghaderi A, Long X, Reynolds JE, Lebel C, Protzner AB. The longitudinal relationship between BOLD signal variability changes and white matter maturation during early childhood. NeuroImage 2021, 242, 118448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson JS, Zielinski BA, Nielsen JA, Ferguson MA. Complexity of low-frequency blood oxygen level-dependent fluctuations covaries with local connectivity. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2013, 35, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malins JG, Pugh KR, Buis B; et al. Individual Differences in Reading Skill Are Related to Trial-by-Trial Neural Activation Variability in the Reading Network. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 2981–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Cheng W, Liu Z; et al. Neural, electrophysiological and anatomical basis of brain-network variability and its characteristic changes in mental disorders. Brain 2016, 139, 2307–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan RC, Kristjansson SD, Reiersen AM, Parra AS, Anokhin AP. Neural correlates of inhibitory control and functional genetic variation in the dopamine D4 receptor gene. Neuropsychologia 2014, 62, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dona O, Hall GB, Noseworthy MD. Temporal fractal analysis of the rs-BOLD signal identifies brain abnormalities in autism spectrum disorder. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0190081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dona O, Noseworthy MD, DeMatteo C, Connolly JF. Fractal Analysis of Brain Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent (BOLD) Signals from Children with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, S. Age-associated patterns in gray matter volume, cerebral perfusion and BOLD oscillations in children and adolescents. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 2398–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng X, Sun J, Lv Y; et al. Frequency-specific alterations of the resting-state BOLD signals in nocturnal enuresis: An fMRI Study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs J, Hawco C, Kobayashi E; et al. Variability of the hemodynamic response as a function of age and frequency of epileptic discharge in children with epilepsy. Neuroimage. 2008, 40, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman JS, Lake DE, Moorman JR. Sample Entropy. In: Methods in Enzymology. Vol 384. Numerical Computer Methods, Part E. Academic Press. 2004; pp. 172-184. [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra BS, Dutt DN. Computing Fractal Dimension of Signals using Multiresolution Box-counting Method. 2010, 16.

- Garrett DD, Samanez-Larkin GR, MacDonald SWS, Lindenberger U, McIntosh AR, Grady CL. Moment-to-moment brain signal variability: A next frontier in human brain mapping? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi B, Badcock C. Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain. Behav. Brain Sci. 2008, 31, 241–261, discussion 261–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li SC, Lindenberger U, Bäckman L. Dopaminergic modulation of cognition across the life span. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 34, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitart-Masip M, Salami A, Garrett D, Rieckmann A, Lindenberger U, Bäckman L. BOLD Variability is Related to Dopaminergic Neurotransmission and Cognitive Aging. Cereb. Cortex. 2016, 26, 2074–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Developmental Psychopathology. 1st ed. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015. [CrossRef]

- Berry AS, Shah VD, Baker SL; et al. Aging Affects Dopaminergic Neural Mechanisms of Cognitive Flexibility. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 12559–12569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavash M, Lim SJ, Thiel C, Sehm B, Deserno L, Obleser J. Dopaminergic modulation of hemodynamic signal variability and the functional connectome during cognitive performance. NeuroImage 2018, 172, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto Y, Otani S, Grace AA. The Yin and Yang of Dopamine Release. Neuropharmacology 2007, 53, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu W, Ma Z, Ma Y, Dopfel D, Zhang N. Suppressing Anterior Cingulate Cortex Modulates Default Mode Network and Behavior in Awake Rats. Cereb. Cortex 2021, 31, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou L, Pu W, Wang J; et al. Inefficient DMN Suppression in Schizophrenia Patients with Impaired Cognitive Function but not Patients with Preserved Cognitive Function. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadders-Algra, M. Early Diagnostics and Early Intervention in Neurodevelopmental Disorders—Age-Dependent Challenges and Opportunities. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title | Author and Year | Location (Region, Country) | Study Design | Age of Subjects |

Sex | Sample Size | Case definition |

| Age-Associated Patterns in Gray Matter Volume, Cerebral Perfusion and BOLD Oscillations in Children and Adolescents | Bray et al. 2017 | Calgary, Alberta, Canada | Cross-Sectional | Mean= 13.8, SD = 3.12 Range = 7–18 |

Typically developing females = 34 Typically developing males = 25 |

Typically developing = 59 | All participants healthy (No cases) |

| BOLD SV and complexity in children and adolescents with and without autism spectrum disorder | Easson, et al. 2019 | Toronto Ontario Canada | Cross-Sectional | ASD Group Mean = 13.25, SD = 2.87 ASD Group Range = [9.6 – 17.80] Typically Developing Mean = 13.42 SD = 3.21 Typically Developing Range [8.10 – 17.60] |

ASD Males= 20 Typically Developing Males = 17 |

ASD = 20 Typically Developing = 17 Total Sample Size = 37 |

Autism spectrum disorder was defined by the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) II database (Where cases ascertained from) |

| Changes in BOLD variability are linked to the development of variable response inhibition: BOLD variability and variable response inhibition | Thompson et al. 2020 | London UK | Cross-Sectional | Children Range = [10 – 12] Children Mean = 11.56, SD = 0.83 Adult Range = [18 – 26] Adult Mean = 21.55, SD = 2.31 |

Females = 10 Males = 9 |

Children 10-12 = 19 Adults 18-26 = 26 Total = 45 |

All participants healthy (No cases) |

| Creative internally directed cognition is associated with reduced BOLD variability | Roberts,et al. 2020 | Auckland, New Zealand | Cross-Sectional | Range = [17-25] Mean = 21 years, SD = 4 years |

8 Males and 16 Females | 24 typically developing | All participants healthy (No cases) |

| Disentangling resting-state BOLD variability and PCC functional connectivity in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome | Zöller et al. 2017 | Geneva Switzerland | Case Control | 22q11.2 Gene Age Range = [9.0-24.8] Mean 22q11.2 Gene Age = 16.53 ± 4.25 Control Group Age Range = [9.5 - 24.9] Mean Control Group Age = 16.44 ± 4.20 |

Males = 21 Females = 29 |

Healthy Controls = 50 (22/28) 2q11.2DS = 50 (21/29) Total = 100 |

50 patients with 22q11.2DS, which is a specific type of microdeletion in chromosome 22 |

| Individual Differences in Reading Skill Are Related to Tiral-by-Trial Neural Activation Variability in the Reading Network | Malins et al. 2017 | United States | Cross-Sectional | Discovery Sample Range = [7.8 – 11.3] Discovery Sample Mean = 9.3, SD = 0.6 Confirmation Sample Range = [7.5 – 11.3] Cnfirmation Sample Mean = 9.4, SD = 1.1 |

Sample 1 females: 18 female Sample 1 males: 26 male Sample 2 females: 14 female Sample 2 males: 18 males |

Sample 1 = 44 Sample 2 = 32 Total = 76 |

All participants healthy (No cases) |

| Moment-to-Moment BOLD Signal Variability Reflects Regional Changes in Neural Flexibility across the Lifespan | Nomi et al 2017 | Miami, Florida USA | Cross-Sectional | Slow repetition time Range = [6–85] Slow repetition time Mean = 42.26, SD = 23.60 Fast repetition time Range = [6–85] Fast repetition time Mean = 42.46, SD = 23.30 |

191 participants, 132 Female, 59 male | 191 Particpants | All participants healthy (No cases) |

| Neural correlates of inhibitory control and functional genetic variation in the dopamine D4 receptor gene | Mulligan et al. 2014 | Alberta, Canada | Cross-Sectional | All Participants are 18 | Female population = 33 Male population = 29 |

7R+ = 23 7R- control = 39 Total = 62 |

(R7+) group (dopamine D4 receptor gene (DRD4) with 7 repeats in the Variable Number of Tandem Repeats section (VNTR) of DRD4) |

| Neural, electrophysiological and anatomical basis of brain-network variability and its characteristic changes in mental disorders | Zhang et al. 2016 | Nanjing, PR, China | Case Control | Total Study Age Range = [8-52] UM Sample Controls = 15.1 +/- 3.7 Autism = 3.6 +/- 2.4 Peking University-PKU Sample Controls = (11.4 +/- 1.9) ADHD = (12.1 +/- 2.0) New York University-NYU Controls = (12.2 +/- 3.1) ADHD = (12.2 +/-13.1) |

Autism UM dataset controls = (48/16) Autism UM dataset Autism = (31/7) ADHD PKU dataset controls = (84/59) ADHD PKU dataset ADHD = (89/10) ADHD NYU dataset controls = (54/54) ADHD NYU dataset ADHD = (106/34) |

Autism MU dataset controls = 64 Autism MU dataset Autism = 38 ADHD PKU dataset controls = 143 ADHD PKU dataset ADHD = 99 ADHD NYU dataset controls = 108 ADHD NYU dataset ADHD = 140 Total = 592 (we only use a subset of 1180 total in this study due to age exclusions) |

Schizophrenia case definition as defined by: [Dataset 1: Taiwan (Guo et al., 2014); Dataset 2: COBRE], Autism case definition as defined by: (Dataset 3: New York University-NYU; and Dataset 4: University of Melbourne-UM, which are from ABIDE Consortium) and ADHD case definition (Dataset 5: Peking University-PKU; and Dataset 6: New York University-NYU, which are part of the 1000 Functional Connectome Project) |

| Psychotic symptoms influence the development of anterior cingulate BOLD variability in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome | Zöller et al. 2017 | Geneva Switzerland | Case-Control | Between 10 and 30 years old | PS+ = 28 (12/16) PS - = 29 (14/15) Healthy controls = 69 (30/39) |

22q11.2 gene = 57 Healthy Controls = 69 Total = 126 |

Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11DS) is a neurodevelopmental disorder associated with a broad phenotype of clinical, cognitive, and psychiatric features. It is a specific type of microdeletion in chromosome 22 |

| Temporal fractal analysis of the rs-BOLD signal identifies brain abnormalities in autism spectrum disorder | Dona et al. 2017 | Austin, Texas, United States | Case-Control | ASD (12.7 ± 2.4 y/o) 55 age-matched (14.1 ± 3.1 y/o) healthy controls |

ASD = 46 male and 9 females, Healthy controls = 38 male and 9 females. |

ASD = 55 Healthy Control = 55 Total = 110 |

ASD and age matched controls. Definition of ASD defined by NITRC database and the ABIDE project |

| Variability of the hemodynamic response as a function of age and frequency of epileptic discharge in children with epilepsy | Jacobs et al. 2007 | Germany and Montreal Canada | Cross-Sectional | Range = [5 months - 18 years] (Mean and SD not calculated) | 12 Female, 25 Male | 37 | Epilepsy, case definition of epilepsy not explicit but EEG-fMRI data were only acquired in children who fulfilled the following criteria: 1) indication for an anatomical scan on the basis of the necessity to investigate a lesion seen on a prior anatomical MRI scan or to diagnose their epilepsy syndrome and exclude pathological changes, and 2) frequent spikes (N 10 in 20 min) recorded on routine EEG outside the scanner, without occurrence in bursts. |

| Evaluation of spontaneous regional brain activity in weight-recovered anorexia nervosa | Seidel et al. 2020 | Germany | Case Control Study | Total Study Range = 15.5–29.7 recAN Mean = 22.06, SD = 3.38 HC Mean = 22.05, SD = 3.34 |

Healthy Control = 65 Female recAN = 65 female |

Healthy Control = 65 recAN = 65 Total = 130 |

Recovered Anerexia Nervosa (Weight Recovered). Defined as recAN subjects had to (1) maintain a body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) > 18.5 (if older than 18 years) or above the 10th age percentile (if younger than 18 years); (2) men- struate; and (3) have not binged, purged, or engaged in restrictive eating patterns during at least 6 months before the study. |

| Complexity of low-frequency blood oxygen level-dependent fluctuations covaries with local connectivity | Anderson et al. 2013 | N/A | Cross-Sectional | Range = [7–30] Mean = 8.3, SD = 5.6 |

Male = 590 Female = 429 |

1019 | Not Specified |

| Fractal Analysis of Brain Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent (BOLD) Signals from Children with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI) | Dona et al. 2017 | N/A | Cross-Sectional | mTBI Subjects = 13.4 ± 2.3 Age-matched Healthy Controls = 13.5 ± 2.34 |

N/A | mTBI = 15 Healthy Control = 56 Total = 71 |

Case Control |

| The longitudinal relationship between BOLD signal variability changes and white matter maturation during early childhood | Wang et al. 2021 | Canada and Australia | Cross-Sectional | Range = 1.97–8.0 years Mean age at intake = 4.42 ± 1.27 |

Females = 43 Males = 40 |

83 | Cross-Sectional so None |

| Frequency-specific alterations of the resting-state BOLD signals in nocturnal enuresis: an fMRI Study | Zheng et al. 2021 | China | Case Control | Range approx = [7-12] NE Patients 9.27(± 1.760) Control 9.68(± 1.601) |

NE males = 57 NE Females = 14 Control Males = 19 Control Females = 16 |

Children with nocturnal enuresis (NE) = 129 Healthy controls = 37 |

Case Control |

| Metric Type | Authors | Variability Metric | Description | Findings and Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deviation from Average BOLD Signal | (Roberts et al. 2020 Zöller et al. 2017, Zöller et al. 2018, Wang et al. 2021, Anderson et Al. 2013) | BOLDSD | Quantified the deviation of average BOLD signal from the mean signal. | BOLD Signal variability globally increased with age in all metrics (some regions decrease) BOLD variability in dACC did not change over age in PS+ patients and increased in PS−. Variability increased with age in the DMN. Positively correlated with GE in structural networks and negatively correlated with performance in ASD behavioral severity (SRS). Negative associations with indexes of creativity |

| (Nomi et al. 2017a, Seidel et al. 2020 Amanda K. Easson and McIntosha 2019) | MSSD | Calculated by subtracting the amplitude of the signal at time point t from time point t + 1, squaring, and then averaging the resulting values from the entire voxel time course. | ||

| Correlational Measures of BOLD Signal Variance | (Zhang et al. 2016) | Temporal Variance | The BOLD time series were segmented into non-overlapping windows, a whole brain signal measure is obtained using Pearson correlation, and a region’s variability is compared to others. | Lower variability of DMN in schizophrenia, and increased variability in Autism/ADHD. Changes in variability were closely related to symptom scores and in the 10% most variable regions. Variability increases with age in the inhibition network. More variability in the network was associated with less variability in behavioral performance. Low variability in the DMN was correlated with high FC. Lower variability in 7R+ when compared to 7R- when participants successfully inhibited a prepotent motor response. Primarily seen in the prefrontal cortex, occipital lobe, and cerebellum. |

| (Malins et al. 2018, and Mulligan et al. 2014) | GLM Derived Variance | GLM produced trial β series estimates of the signal which was used to estimate a variance. | ||

| (Thompson et al. 2021) | Differences of Residuals | The difference in the variability between the two residual models. | ||

| Signal Complexity | Amanda K. Eassona and McIntosha 2019 | Sample Entropy | SE was used in identifying repetitive patterns in a time series. The degree of regularity of these patterns of activation were also observed, with fewer complex signals are more random. | Positive correlations were identified between entropy, GE and age. Negative correlations with SRS severity scores and FD in social and non-social tasks, ADIR and ADOS. Grey matter rs-BOLD FD in mTBI patients had reduced FD. Power law exponents remained unchanged or decreased with age and are linearly related to ReHo, which covaried across subjects and gray matter regions. Grey matter rs-BOLD FD in mTBI patients had reduced FD. The fALFF increased with age, distinguishing posterior, and anterior regions. Higher fALFF values in recAN patient’s cerebellum and the inferior temporal gyrus compared to controls. The fALFF decreased in the right insula in children with NE. |

| (Dona et al. 2017a and Dona et al. 2017b) | Fractal Dimension | Measure of the structural complexity of a signal derived from hurst exponents and quantified structural complexity across different predefined time windows. | ||

| (Anderson et al. 2013) | Power Law Exponents | Power based index of sinusoidal amplitudes in the BOLD signal. Signal that follows fractal characteristics that were self-similar within and across frequencies over a time series were measured. | ||

| (Seidal et al. 2020, Zheng et al. 2021, Bray 2017) | Fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (fALFF) | The ratio of the low frequency power spectrum, specifically in the range of 0.01–0.08 Hz, to the entire signal frequency range. | ||

| Structure of Hemodynamic Response Function | (Jacobs et al. 2008) | HRF Structure | Using the structure of the HRF, like peak time, amplitude or other signal characteristics not mentioned above. | Could not identify an age specific HRF. Longer peak times of the HRF 0 to 2 yrs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).