Submitted:

28 April 2023

Posted:

08 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Raw materials and chemicals

2.2. Instrumentation

2.3. Typical procedures

2.3.1. Extraction from ASA from Commercial Aspirin Tablets

2.4. Sequential transesterification and esterification of ASA in MeOH using NbCl5 as mediator.

2.5. Biological activity

2.5.1. Cytotoxicity Test

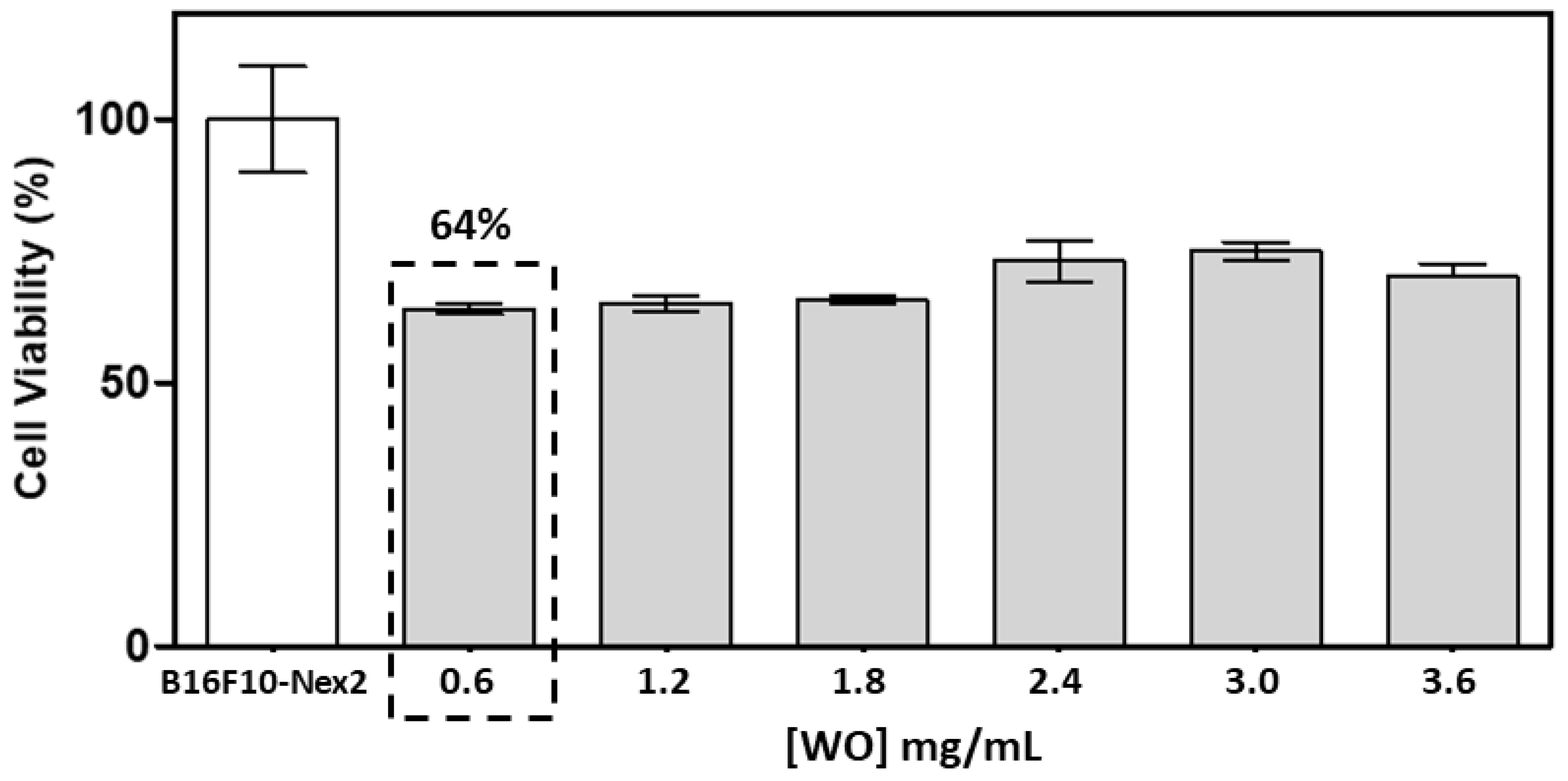

2.5.2. Antitumoral Activity

2.5.3. Antibacterial Test

3. Results and Discussion

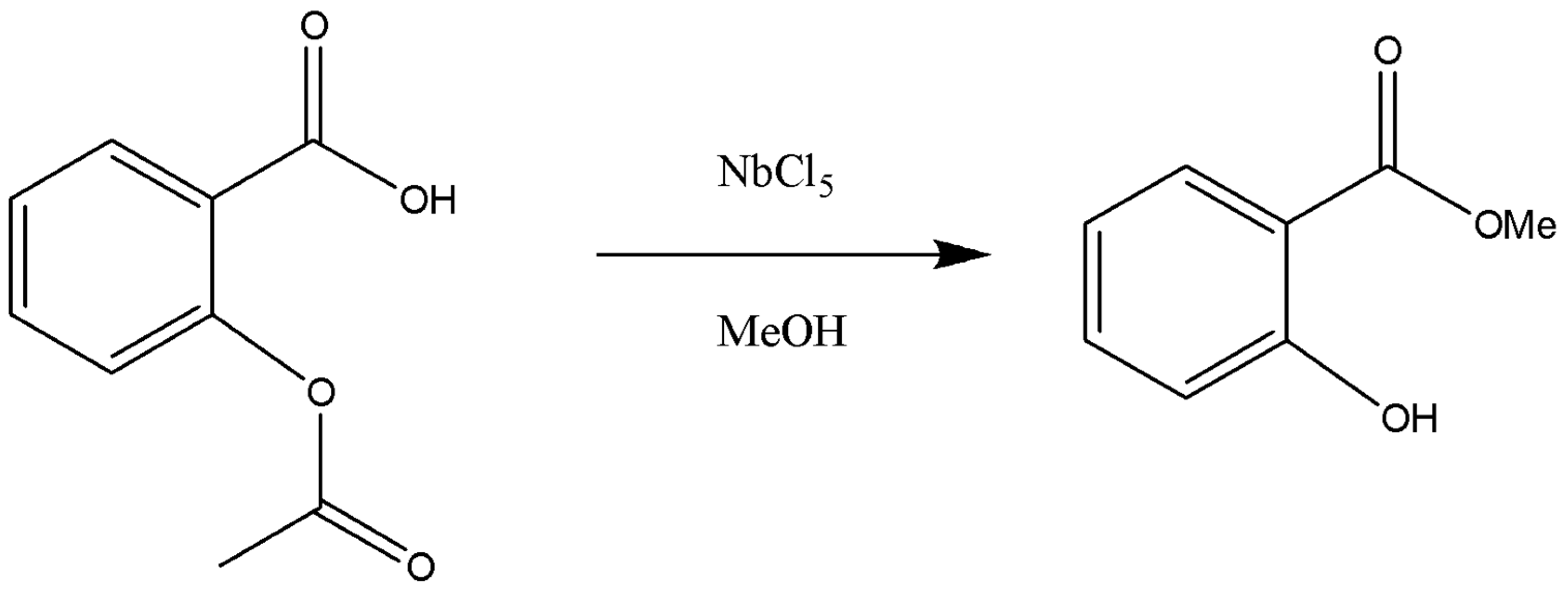

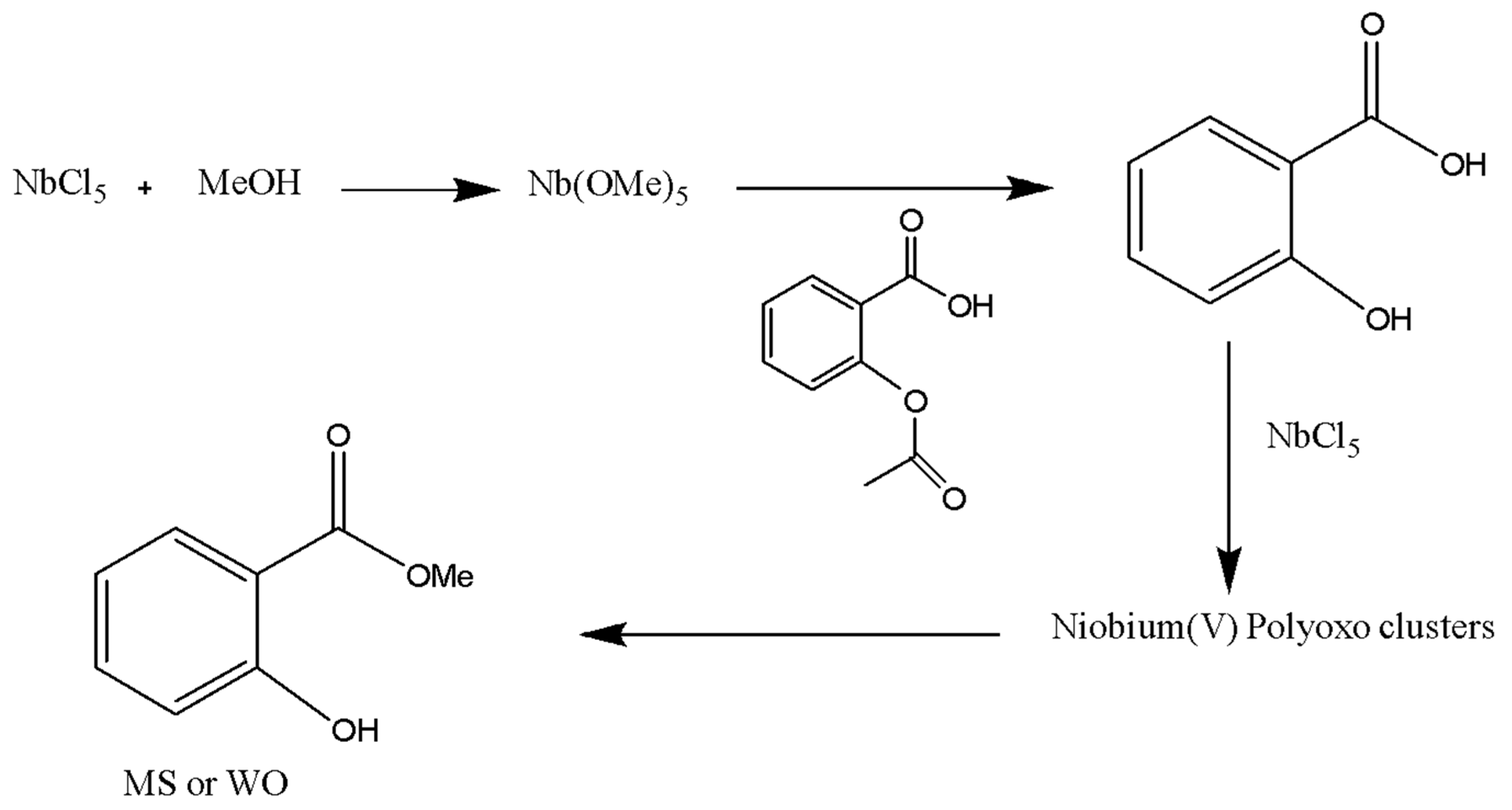

3.1. Synthesis of MS using NbCl5 as stoichiometric reagent.

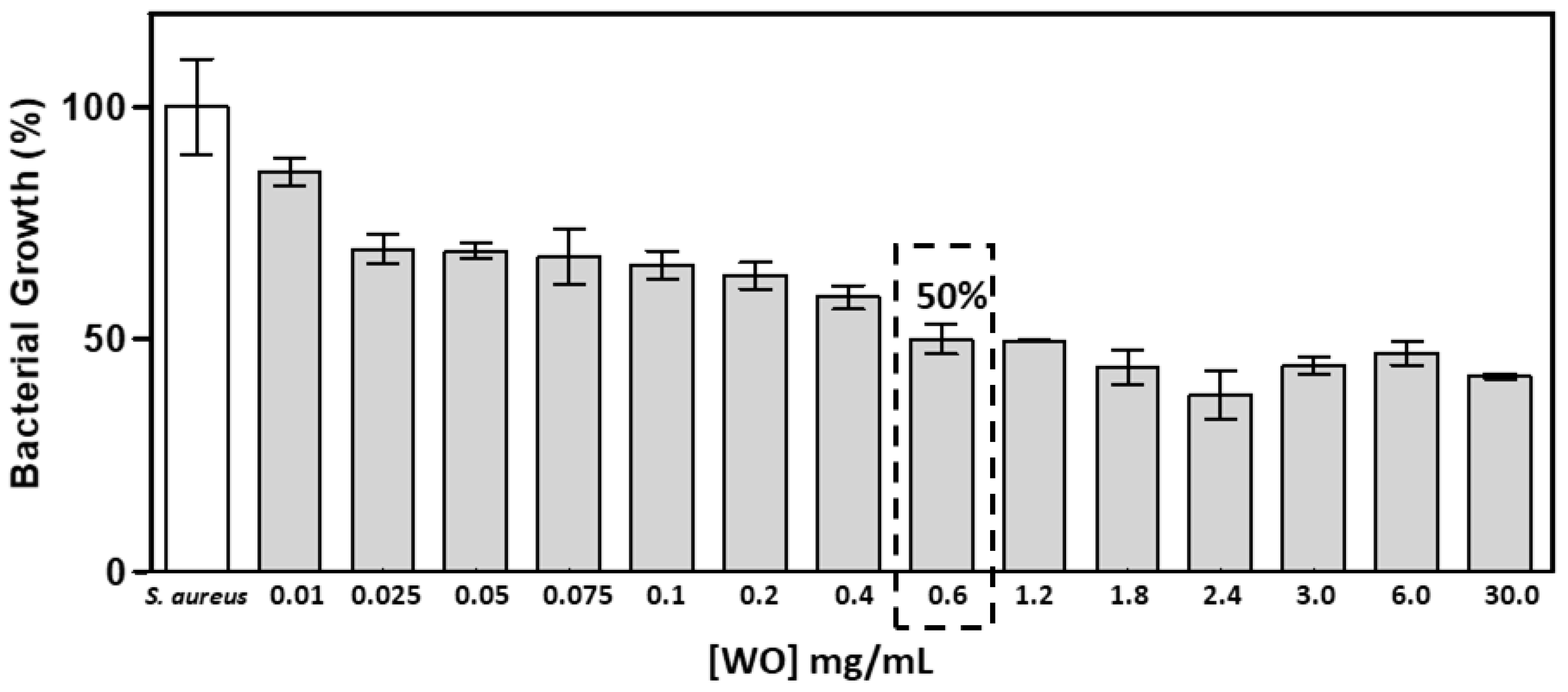

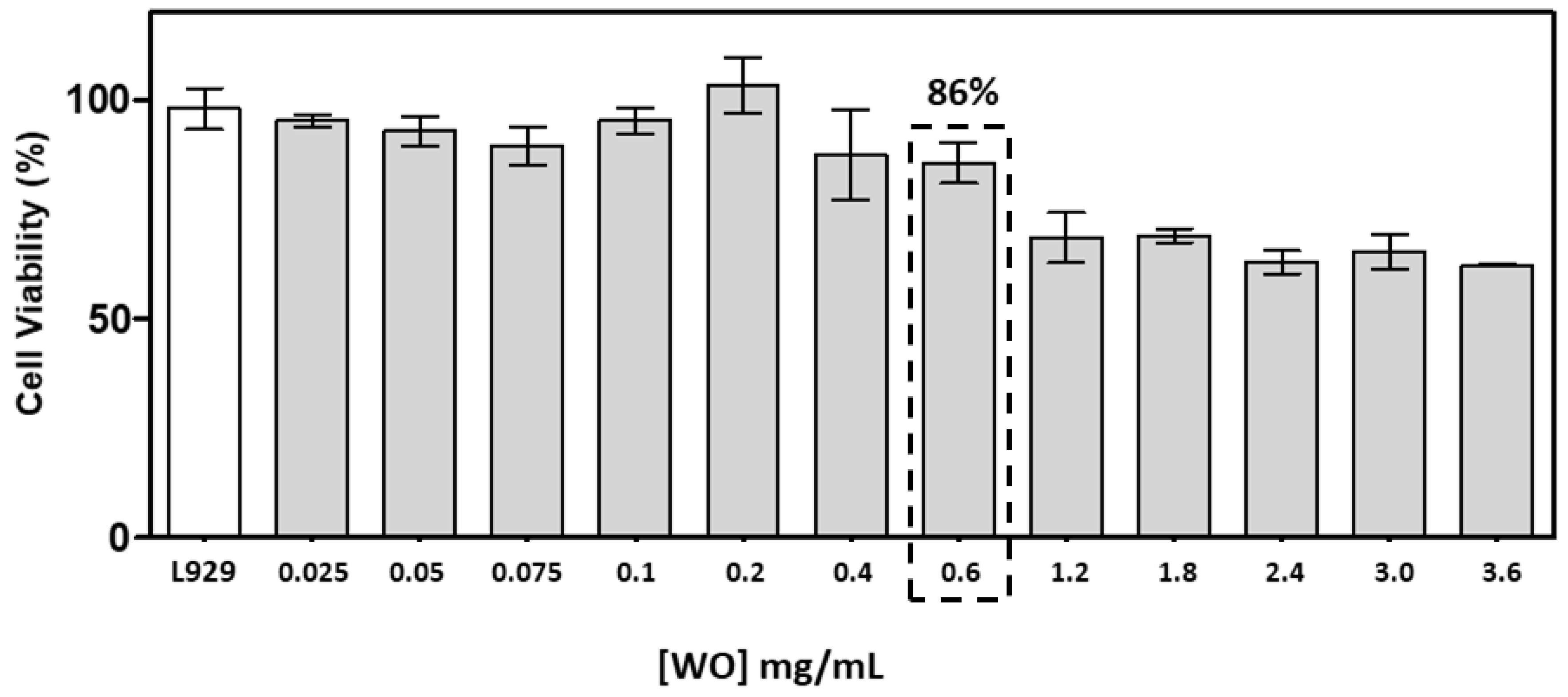

3.2. Study of the biological activity

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- V.E. Tyler, L. Brady, J.E. Robbers. Volatile oils. In: Pharmacognosy. 8th edition. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, PA 19106 (1981) 103-143.

- D.M. Ribnicky. A. Poulev, I. Raskin. The Determination of Salicylates in Gaultheria procumbens for Use as a Natural Aspirin Alternative, Journal of Nutraceuticals, Functional & Medical Foods, 4(1) (2003) 39-52. [CrossRef]

- W.H. Brown, T. Poon. Introduction to Organic Chemistry, 6th Edition, Wiley, New York (2015) 486.

- K.O. Ganiyat. Toxicity, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of methyl salicylate dominated essential oils of Laportea aestuans (Gaud), Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 9 (2016) S840-S845. [CrossRef]

- T. Greene, S. Rogers, A. Franzen, R. Gentry. A critical review of the literature to conduct a toxicity assessment for oral exposure to methyl salicylate. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 47(2) (2017) 98-120. [CrossRef]

- C. Vlachojannis, S. Chrubasik-Hausmann, E. Hellwig, A. Al-Ahmad. A Preliminary Investigation on the Antimicrobial Activity of Listerine®, Its Components, and of Mixtures Thereof. Phytother Res 29(10) (2015) 1590-1594. [CrossRef]

- T. Kato, H. Iijima, K. Ishihara, T. Kaneko, K. Hirai, Y. Naito, K Okuda. Antibacterial effects of Listerine on oral bacteria. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 31(4) (1990) 301-307.

- S.K. Filoche, K. Soma, C.H. Sissons. Antimicrobial effects of essential oils in combination with chlorhexidine digluconate. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 20(4) (2005) 221-225. [CrossRef]

- A. Yamanaka, K. Hirai, T. Kato, Y. Naito, K. Okuda, S. Toda, K. Okuda. Efficacy of Listerine antiseptic against MRSA, Candida albicans and HIV. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 35(1) (1994) 23-26.

- Y. Kasuga, H. Ikenoya, K. Okuda. Bactericidal effects of mouth rinses on oral bacteria. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 38(4) (1997) 297-302.

- E.E. Essien, J.S. Newby, T.M. Walker, W.N. Setzer, O. Ekundayo. Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity of Volatile Constituents from Fresh Fruits of Alchornea cordifolia and Canthium subcordatum. Medicines (Basel), 3 (2016) 1-10. [CrossRef]

- J. Otera, J. Nishikido. Esterification: Methods, Reactions, and Applications. 2009. Print ISBN: 9783527322893. Online ISBN: 9783527627622. Copyright © 2010 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. [CrossRef]

- B. Neises, W. Steglich. Esterification of Carboxylic Acids with Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide 4-Dimethylaminopyridine: Tert-Butyl ethyl fumarate”. Organic Syntheses.; Coll. Vol. 7, 93.

- K. Ishihara, M. Nakayama, S. Ohara, H. Yamamoto. Direct ester condensation from a 1:1 mixture of carboxylic acids and alcohols catalyzed by hafnium (IV) or zirconium (IV) salts, Tetrahedron, 58 (2002) 8179-8188. [CrossRef]

- K. Ishihara, S. Nakagawa, A. Sakakura. Bulky Diaryl Ammonium Arena Sulfonates as Selective Esterification Catalysts, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (4) (2005) 168-4169. [CrossRef]

- K. Komura, A. Ozaki, N. Ieda, Y. Sugi. FeCl3·6H2O as a Versatile Catalyst for the Esterification of Steroid Alcohols with Fatty Acids, Synthesis (2008) 3407-3410. [CrossRef]

- C.-T. Chen, Y.S. Munot. Direct Atom-Efficient Esterification between Carboxylic Acids and Alcohols Catalyzed by Amphoteric, Water-Tolerant TiO(acac)2. J. Org. Chem. 70 (2005) 8625-862. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Chakraborti, B. Singh, S.V. Chankeshwara, A. R. Patel. Protic Acid Immobilized on Solid Support as an Extremely Efficient Recyclable Catalyst System for a Direct and Atom Economical Esterification of Carboxylic Acids with Alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 74 (2009) 5967-5974. [CrossRef]

- A.G.M. Barrett, D.C. Braddock. Scandium (III) or lanthanide (III) triflates as recyclable catalysts for the direct acetylation of alcohols with acetic acid. Chem. Commun. (1997) 351-352. [CrossRef]

- K.V.N. S. Srinivas, I. Mahender, B. Das. Silica Chloride: A Versatile Heterogeneous Catalyst for Esterification and Transesterification. Synthesis (2003) 2479-2482. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen, Y. Wen, Y. Fu, H. Chen, M. Ye, G. Luo. Graphene oxide is an efficient and reusable acid catalyst for the esterification reaction. A wide range of aliphatic and aromatic acids and alcohols were compatible and afforded the corresponding products in good yields. The heterogeneous catalyst can be easily recovered and recycled. Synlett. 28 (2017) 981-985. [CrossRef]

- H. Sharghi, M. Hosseini Sarvari. Al2O3/MeSO3H (AMA) as a new reagent with high selective ability for monoesterification of diols. Tetrahedron. 59 (2003) 3627-3633. [CrossRef]

- R. Moumne, S. Lavielle, P. Karoyan. Efficient Synthesis of 2-Amino Acid by Homologation of β2-Amino Acids Involving the Reformatsky Reaction and Mannich-Type Imminium Electrophile. J. Org. Chem. 71 (2006) 3332-3334. [CrossRef]

- S.L. Barbosa, G.R. Hurtado, S.I. Klein, V.L. Junior, M.J. Dabdoub, C F. Guimarães. Niobium to alcohol mol ratio control of the concurring esterification and esterification reactions promoted by NbCl5 and Al2O3 catalysts under microwave irradiation. Applied Catalysis A: General 338 (2008) 9-13. [CrossRef]

- S. Gryglewicz. Alkaline-earth metal compounds as alcoholysis catalysts for ester oils synthesis. Applied Catalysis A: General 192 (2000) 23-28. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liu, R. Xin, C. Li, C. Xu, J. Yang. Application of red mud as a basic catalyst for biodiesel production. Journal of Environmental Sciences. 25(4) (2013) 823-829. [CrossRef]

- C. Mazzocchia, G. Modica, A. Kaddouri, R. Nannicini. Fatty acid methyl esters synthesis from triglycerides over heterogeneous catalysts in the presence of microwaves. Comptes Rendus Chimie. 7 (2004) 601-605. [CrossRef]

- S.L. Barbosa, D.L. Nelson, M.S. Freitas, W.T.P. dos Santos, S.I. Klein, G.C. Clososki, F.J. Caires, A.P. Wentz. Tandem Transesterification–Esterification Reactions Using a Hydrophilic Sulfonated Silica Catalyst for the Synthesis of Wintergreen Oil from Acetylsalicylic Acid Promoted by Microwave Irradiation. Molecules 27(15) (2022) 4767. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Hartel, J.M. Hanna Jr. Preparation of Oil of Wintergreen from Commercial Aspirin Tablets A Microscale Experiment Highlighting Acyl Substitutions. Journal of Chemical Education. 86(4) (2009) 475-476. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Pfaller, D.J. Diekema, R.N. Jones, S.A. Messer, R.J. Hollis. J Clin Microbiol. Trends in Antifungal Susceptibility of Candida spp. Isolated from Pediatric and Adult Patients with Bloodstream Infections: SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997 to 2000. 40(3) (2002) 852-856. [CrossRef]

- S.L. Barbosa, C.D. Lima, M.A.R. Almeida, L.S. Mourão, M. Ottone, D.L. Nelson, S.I. Klein, L.D. Zanatta, G.C. Clososki, F.J. Caires, E.J. Nassar, G.R. Hurtado. The preparation of benzyl esters using stoichiometric niobium (V) chloride versus niobium grafted SiO2 catalyst: A comparison study. Heliyon 4 (2018) e00571. [CrossRef]

- C.D. Andriotou, S. Duval, C. Volkringer, X. Trivelli, W.E. Shepard, T. Loiseau. Structural Variety of Niobium(V) Polyoxo Clusters Obtained from the Reaction with Aromatic Monocarboxylic Acids: Isolation of {Nb2O}, {Nb4O4} and {Nb8O12}. Chem. Eur. J. 28 (2022) e202201464 (1 of 18). [CrossRef]

- D.A. Brown, M.G.H. Wallbridge, N.W. Alcock. Preparation of some oxoniobium carboxylates. X-Ray crystal and molecular structure of [{NbCl3(O2CPh)}2O]. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. (1993) 2037-2039. [CrossRef]

- D.A. Brown, M.G.H. Wallbridge, W. S. Li, M. McPartlin, I.J. Scowen. Synthesis of some dinuclear niobium chloro alkoxy carboxylates [Nb2Cl4(OEt)4(O2CR)2], and the X-ray crystal and molecular structure of the compound with RPh. Inorg. Chim. Acta 227 (1994) 99-104. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Narula, B. Singh, P.N. Kapoor, R.N. Kapoor. Cinnamates of niobium(V) and tantalum(V). Transition Met. Chem. 8 (1983) 195-198. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).