1. Introduction

The survivors of breast cancer are prone to experience psychological problems, so it is important to consider specific methods to improve their quality of life (QOL). This is due to the fact that many breast cancer patients have high survival rates after treatment and live for a long time as survivors. Psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, and poor body image are found in 20-40% of survivors of breast cancer 1 year after surgery and in 15% 5 years after diagnosis [

1], and QOL is likely to decrease due to increased difficulties in daily life caused by treatment side effects and unemployment [

2]. To maintain and improve QOL, it is important to improve these survivors’ sense of coherence (SOC) [

3]. SOC is the ability to cope with stress and consists of three senses: “comprehensibility,” “manageability,” and “meaningfulness” [

4]. “Comprehensibility” refers to the sense of being able to understand one’s current situation and predict future situations to some extent; “Manageability” is the sense of being able to manage and get by in life; and “meaningfulness” is the sense of coping with stress and finding meaning in daily activities. SOC is a predictor of QOL [

5], and using more coping strategies increases SOC [

6]. It has also been reported that the higher the SOC, the lower the anxiety and depression, and the higher the QOL [

7]. Rohani et al. [

5] stated that in patients with breast cancer, SOC is a main variable in the psychological process during the disease. In this way, even though the associations between QOL, SOC, and anxiety and depression in participants with breast cancer have been clarified in previous studies, specific supportive methods to increase QOL have not been indicated.

When we consider the QOL of our patients, it is necessary to consider their difficulties in daily life and subjective factors [

8]. The World Health Organization (WHO) developed the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) for use as a comprehensive rating scale to assess a person’s limitations of activity and constraints on participation. It also measures difficulties in daily life activities as a disability according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [

8,

9]. Among previous studies using WHODAS 2.0 to assess the QOL of survivors of breast cancer, Lourenço et al. [

10] noted that patients with poor QOL experience many difficulties in daily life. Chachaj et al. [

11] listed upper extremity pain, difficulty arm movement, lymphedema, and prior chemotherapy as factors associated with decreased QOL and an increased WHODAS 2.0 score. The Chinese version [

12] and the German version of WHODAS 2.0 [

13] have been reported to be useful scales for assessing difficulties in the daily life of patients with breast cancer.

As one of the factors of difficulty in daily life, “occupational dysfunction” is defined as a negative experience related to engaging in daily activities and is a major health-related problem that has evolved primarily in the field of preventive occupational therapy [

14]. It includes four domains in which a person feels limited in the activities of living [

14]. These four domains are defined as follows: occupational imbalance, a loss of balance when performing daily activities [

14,

15]; occupational alienation, situations for which an individual’s inner needs related to daily activities are not met [

14,

15]; occupational deprivation, loss of opportunities to perform daily activities that is beyond the individual’s control [

14,

15]; and occupational marginalization, loss of an individual’s opportunities to perform desired daily activities [

14,

15]. Among health care workers, occupational dysfunction is a factor associated with psychological problems related to burnout syndrome, depression, and the response to stress [

16,

17].

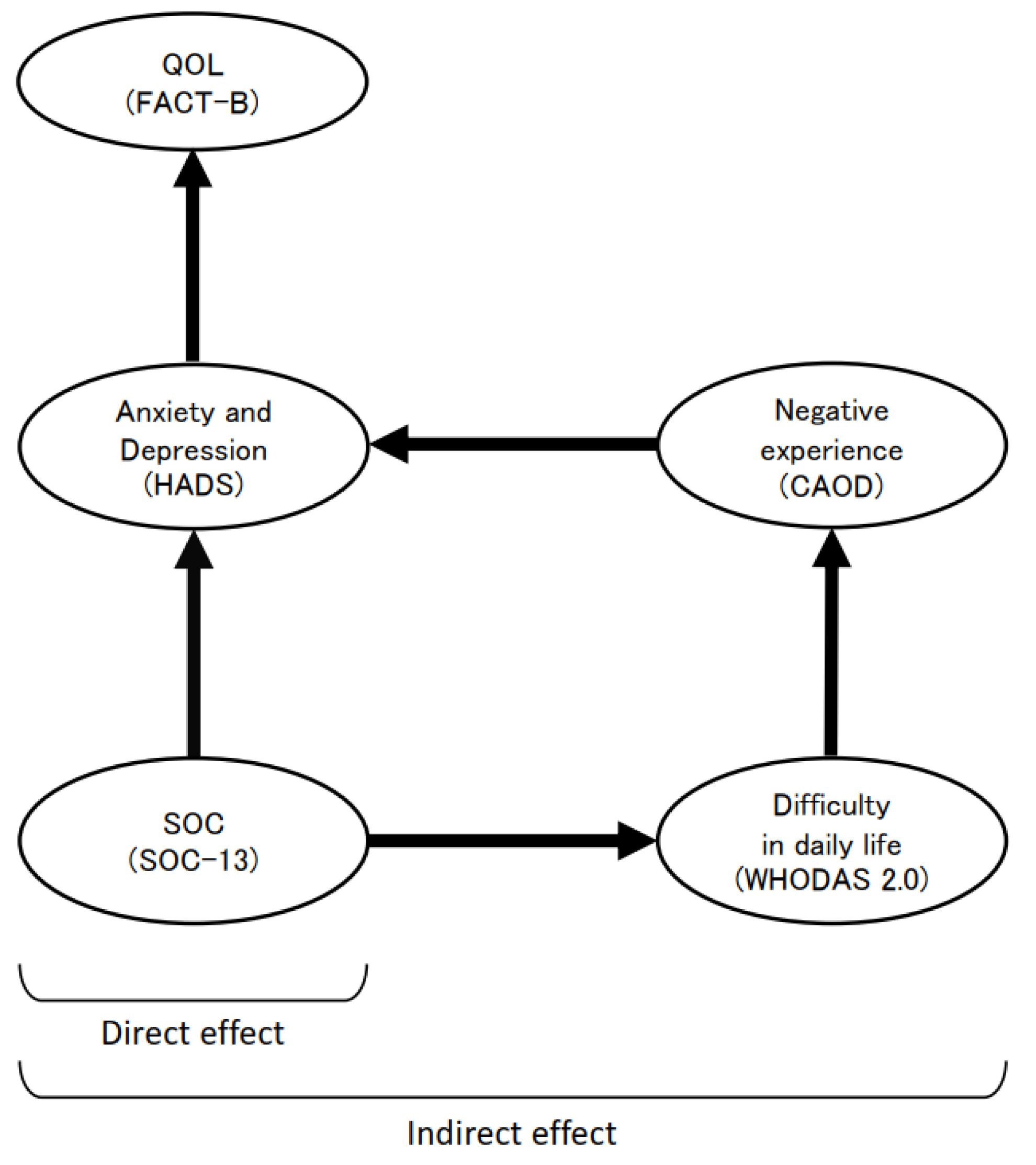

However, the structural relationship between difficulty in daily life and occupational dysfunction (a negative experience) in the QOL of patients and survivors of breast cancer has not been investigated. Therefore, we developed a hypothetical model to construct a structural equation model of QOL based on difficulty in daily life, considering that difficulty in daily life and negative experiences are included as variables in QOL (

Figure 1). The hypothesized model was based on direct associations leading from “SOC” to “anxiety and depression” and from “anxiety and depression” to “QOL,” which have already been shown in previous studies, and the additional structural relationships leading from “SOC” to “anxiety and depression” to “QOL” as mediated by “difficulty in daily life” and “negative experience.” Bayesian structural equation modeling (BSEM) was used to investigate the effectiveness of this model. If validated, this structural model could provide a basis for the development of support strategies to increase a survivor’s QOL by alleviating difficulties in daily life and improving negative experience. Thus, the purpose of this study was to clarify the structural relationship of QOL in survivors of breast cancer, including difficulty in daily life and negative experience as health-related indicators.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants in this multicenter cross-sectional study were survivors of breast cancer who belonged to 7 self-help groups (SHGs) and responded to recruitment requests between June and August 2021. The eligibility criteria were i) at least 2 years after primary breast cancer surgery, ii) 20 years old or older, and iii) individuals who could understand the questionnaires and give their consent to the explanation of this study. Individuals with dementia, neuropsychiatric diseases, and physical disabilities before the first surgery for breast cancer were excluded. SHGs are voluntarily formed small groups aiming at mutual assistance and achievement of specific goals [

18], and breast cancer accounts for 78.7% of the SHGs formed for patients with cancer in Japan [

19]. To analyze whether the statistical power for acceptable goodness-of-fit index (GFI) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.08 [

20], the sample size of the collected data α = 0.05, and the degree of freedom (df) in structural equation modeling (SEM) were sufficient, a post hoc power analysis was performed using the “semPower” package in the statistical software R [

21] to perform a prior power analysis. The sample size satisfying an acceptable RMSEA = 0.08 with α = 0.05 and df = 147 degrees of freedom was 53. We recruited a planned intake of 70 participants to account for participant dropouts.

2.2. Procedure

General information such as sex, age, dominant hand, family structure, employment, and period of participation in SHGs and medical information such as diagnosis, date of surgery, age at the date of surgery, operation type, and stage classification were collected from the participants. The assessment used the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), 13-item version of SOC (SOC-13), WHODAS 2.0, and Classification and Assessment of Occupational Dysfunction (CAOD). Response to the surveys were requested by mail or web forms.

2.3. FACT-B

The FACT-B [

22], a cancer-specific QOL scale, answers questions about one’s condition in the last seven days. FACT-B consists of five domains: Physical Well-Being (PWB), Social/Family Well-Being (SWB), Emotional Well-Being (EWB), Functional Well-Being (FWB), and Breast Cancer Subscale (BCS). Participants were asked to answer 37 questions on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (does not apply at all) to 4 (applies very well). The total score range is 0–148. The total score was calculated using the specified scoring method, with higher total scores indicating higher QOL. We used “Version 4 Japanese version” in this study.

2.4. HADS

The HADS is an anxiety and depression scale [

23] answered considering one’s state in the past week. It consists of 7 items each that assess anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D). Participants were asked to answer 14 questions on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. The total score range is 0–42 points, with 0–7 points being considered “Negative,” 8–10 points being “Possible,” and 11 or more points being “Definite.” The total score was calculated, with higher total scores indicating lower levels of anxiety and depression.

2.5. SOC-13

The 13-item version of the 7-item SOC-13 [

24] was used in this study. The SOC-13 is scored from 1 to 7 points for each item. The range of scores was 13–91, and the general average was 54–58, with higher scores indicating better stress coping skills.

2.6. WHODAS 2.0

The 36-item self-completed version of the WHODAS 2.0 [

8,

9] was used in this study. An individual’s level of functioning across six major life domains is assessed with this version: (i) cognition (understanding and communication); (ii) mobility (ability to move and get around); (iii) self-care (ability to attend to personal hygiene, dressing and eating, and to live alone); (iv) getting along (ability to interact with other people); (v) life activities (ability to carry out responsibilities at home, work, and school); and (vi) participation in society (ability to engage in community, civil, and recreational activities). We asked the participants to answer the 36 questions, six for each domain, based on a 5-point Likert response scale with responses that range from “no problem” to “I can’t do anything at all.” Scores for each domain and the total score were standardized. All scores (total and for each major life domain) range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater health-related difficulties in daily life.

2.7. CAOD

The CAOD is an assessment of occupational dysfunction as a negative experience a person has when unable to perform living activities properly [

14]. The participants were asked to answer 16 questions on a 7-point scale from “1 (disagree)” to “7 (agree)”. The score range was 16–112, with higher total scores indicating more severe negative experiences.

2.8. Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis was applied to each of the five assessment scales to measure their structural validity, and reliability coefficients were analyzed. The GFI was obtained from a model created with the corresponding sub-items influenced by each factor and covariance assumed among all factors. Each scale’s sub-items were considered based on the GFI, adjusted GFI (AGFI), and RMSEA, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated to confirm internal consistency of each scale. A GFI of >0.85 [

25] and AGFI of >0.85 [

25] were considered acceptable, as was an upper limit for RMSEA of <0.08 [

26]. Latent variables considered for addition in the hypothetical model were examined with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. For estimation of covariates in the hypothetical model and clarification of their associations, with the variables having a significant relationship in the correlation as independent variables and the five scales as dependent variables, multiple regression analysis with the stepwise technique was performed. Of the variables with significant correlations, those that were higher than the dependent variable in the association in the hypothetical model were not input as independent variables. The hypothesized model, which included difficulties in daily life and negative experience as the latent variables, were verified on the basis of these results. Despite the need for a required sample size of ≥161 for power = 0.8 and α = 0.05 in SEM [

27], we adopted the BSEM approach, which accommodates smaller sample sizes [

28]. If the causal model was significant, multiplication of the path coefficient from “anxiety and depression” to “QOL” and from “SOC” to “anxiety and depression” was considered a direct effect on QOL, and multiplication of the path coefficient from “SOC” to “difficulty in daily life,” from “difficulty in daily life” to “negative experience,” and from “negative experience” to “anxiety and depression” was considered an indirect effect on QOL. BSEM estimation was conducted using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method. The model’s goodness of fit was assessed by the posterior prediction method and posterior predictive p-value (PPP), with a PPP >0.10 indicating good model fit [

29]. Additionally, path coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) between the model’s latent variables were analyzed. The path coefficient was considered significant if the 95% CIs did not contain zero. The number of sampling times was set at 100,000, and convergence of the algorithm was indicated by a convergence statistic set at <1.002.

A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 27 software (IBM, USA), SPSS Amos ver. 25.0 (IBM, USA), and R (version 4.1.2).

2.9. Ethics Statement

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Kitasato University School of Allied Health Sciences (date: April 26, 2021/Approval No.: 2019-030-200) and each SHG. The purpose and content of the study were explained, and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

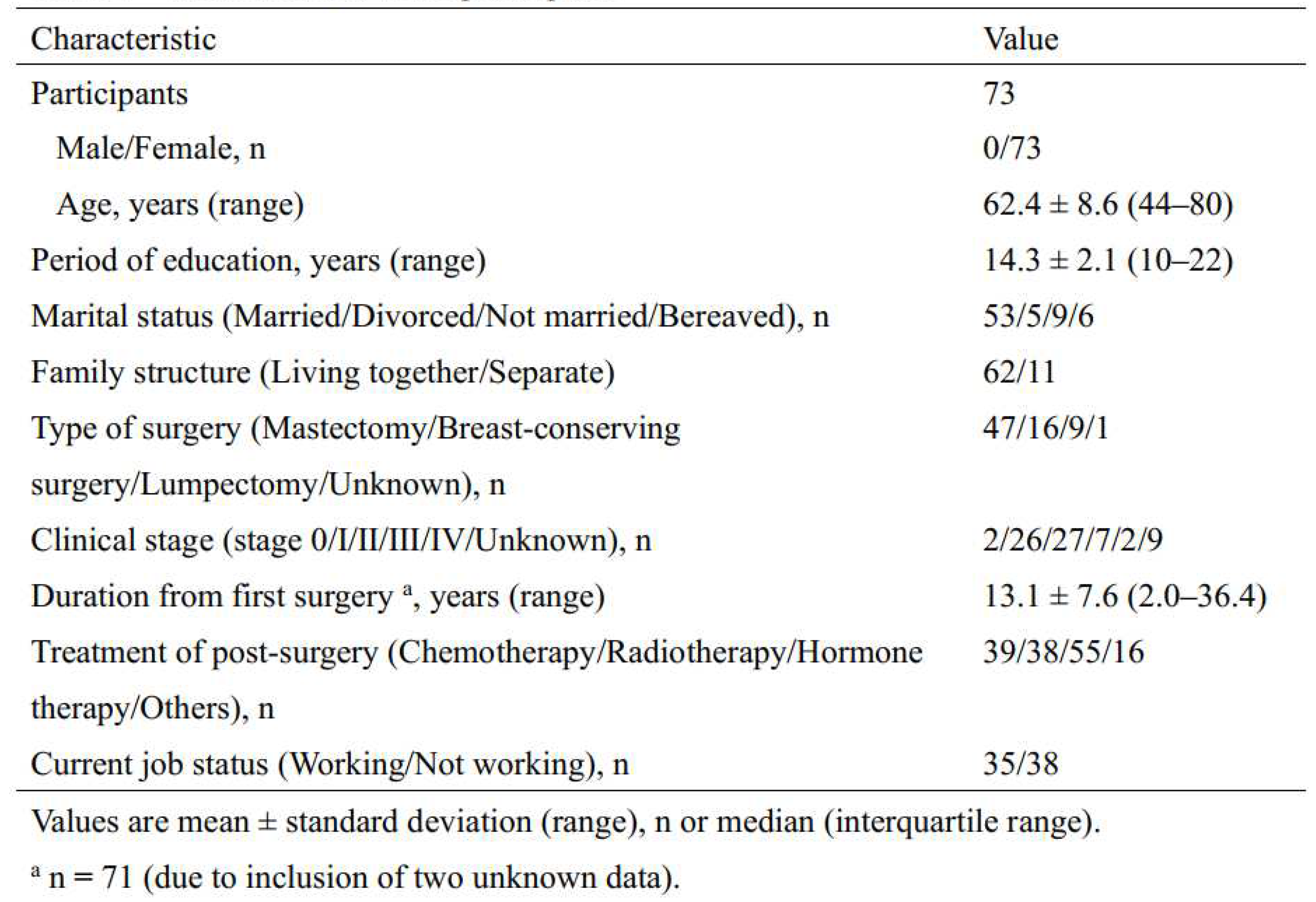

The characteristics of the participants are shown in

Table 1. The participants comprised 73 survivors of breast cancer with an average age of 62.4 ± 8.6 years. It had been 13.1 ± 7.6 years since the first surgery, and about half of the participants were currently employed.

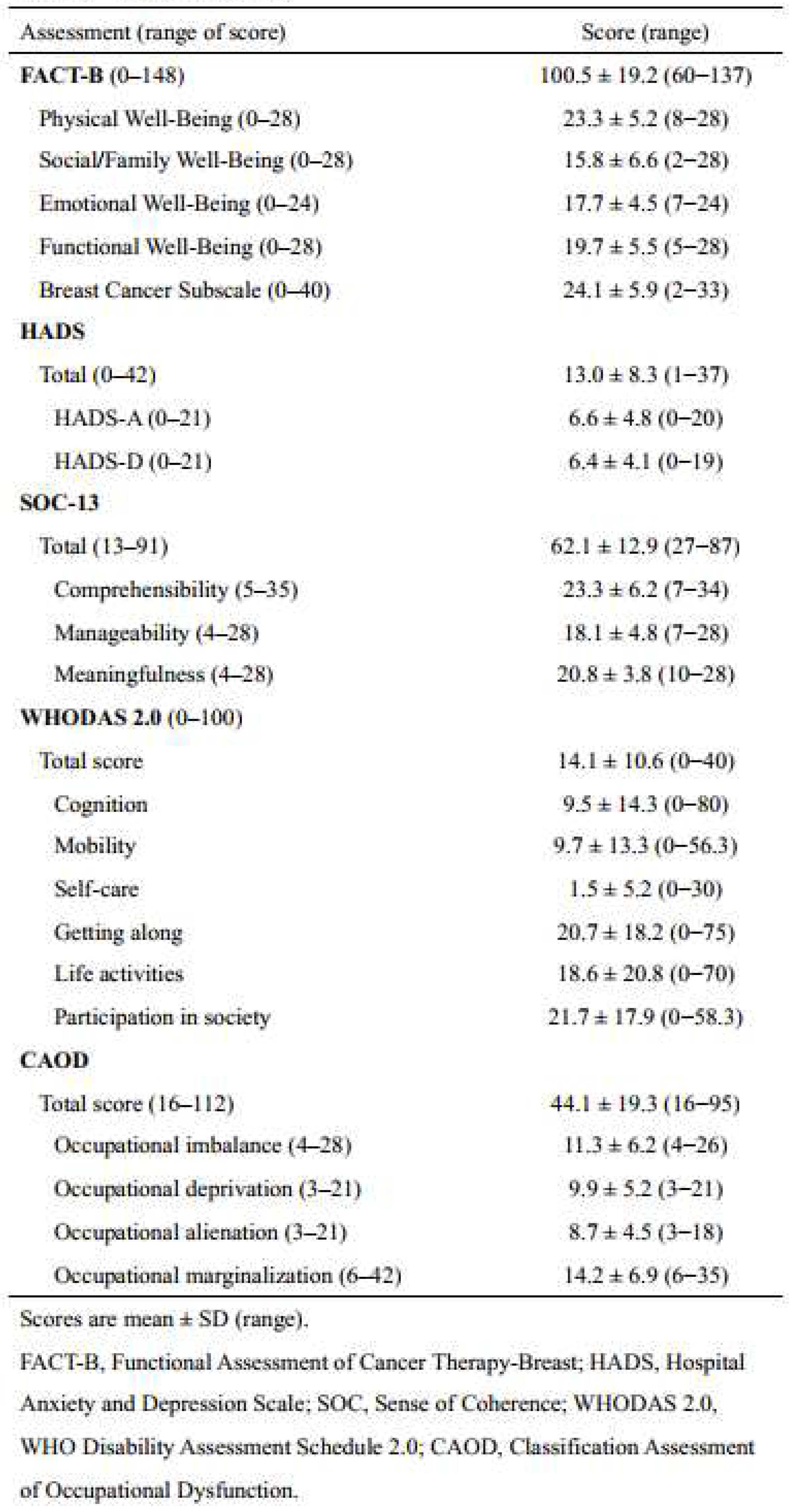

The scores for each assessment scale are shown in

Table 2. The average score of FACT-B was relatively high, but that of Social/Family Well-Being was lower than the other domains. The average score of HADS was higher than the cutoff value of 11, and most of the participants were judged to be sufferers of anxiety and depression. The average score of SOC-13 was higher than the general average of 54–58, indicating that most participants had high stress coping skills. The WHODAS 2.0 scores indicated that the patients experienced difficulties in participation in society, getting along, and life activities. All domains of the CAOD, were lower than the median of the score range.

3.2. Relationship between Each Assessment Scale

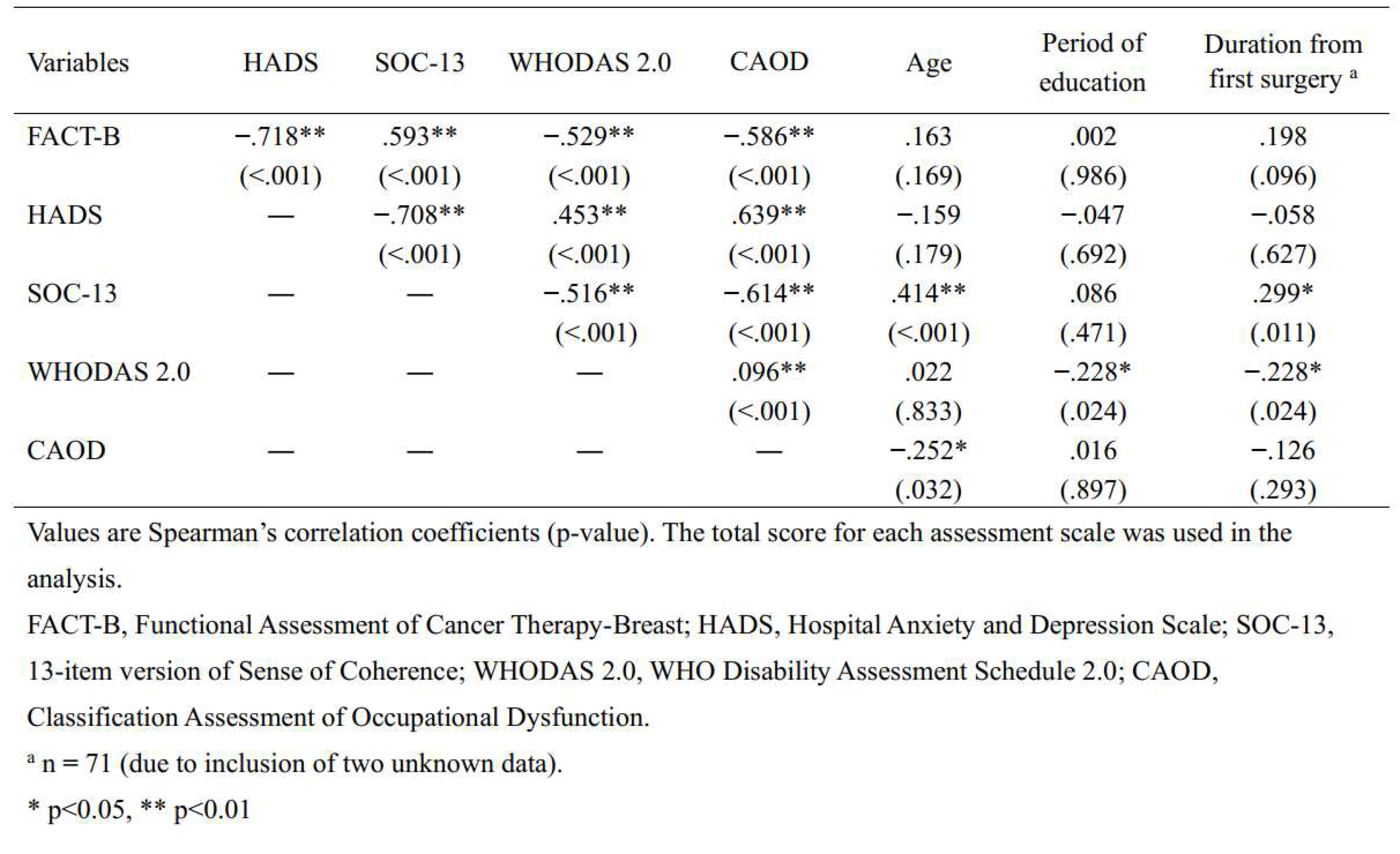

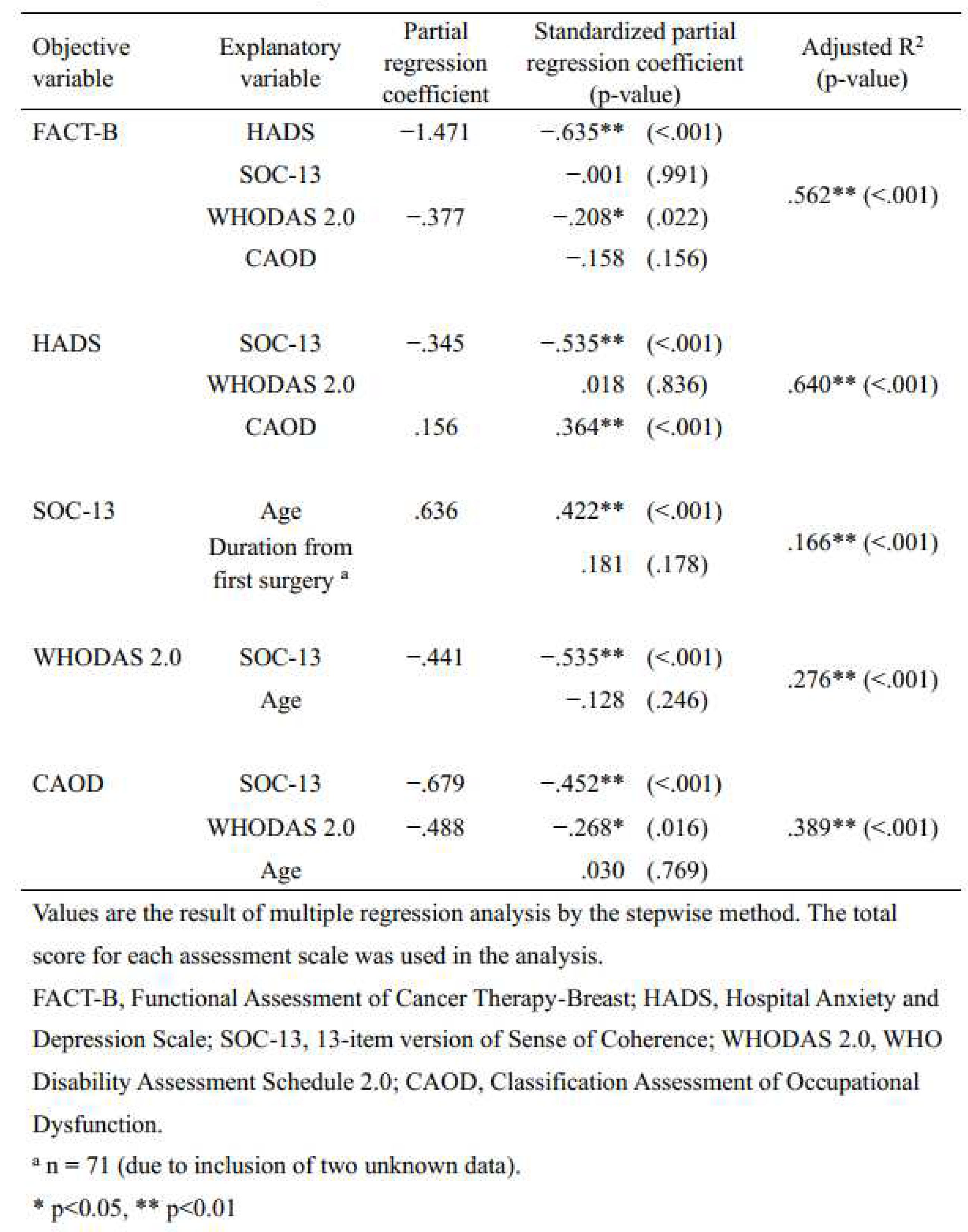

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the sub-items of each assessment scale. The GFI, AGFI, and RMSEA values, which indicate the goodness of fit of the model, were, respectively, 0.980, 0.901, and 0.057 for the FACT-B; 0.896, 0.835, and 0.000 for the HADS; 0.901, 0.847, and 0.000 for the SOC-13; 0.777, 0.702, and 0. 043 for WHODAS 2.0; and 0.875, 0.797, and 0.044 for CAOD, confirming the original factor structure. Cronbach’s alpha for each scale was 0.805 for FACT-B, 0.928 for HADS, 0.864 for SOC-13, 0.902 for WHODAS 2.0, and 0.928 for CAOD. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis, conducted to identify latent variables to consider adding to the hypothetical model, revealed moderately significant correlations between each assessment and significant correlations between age and duration between the first surgery and the assessment (

Table 3). To clarify the associations between each variable, a multiple regression analysis using the stepwise method was conducted with each assessment scale as the dependent variable and the independent variables as those showing significant correlations with each other. The independent variable for FACT-B was the total score of HADS and WHODAS 2.0 (coefficient of determination: R2 = 0.562, p<0.001), that for HADS was the total score of SOC-13 and CAOD (R2 = 0.640, p<0.001), that for SOC-13 was age (R2 = 0.166, p<0.001), that for WHODAS 2.0 was the total SOC-13 (R2 = 0.276, p<0.001), and that for CAOD was the total score of SOC-13 and WHODAS 2.0 (R2 = 0.389, p<0.001) (

Table 4).

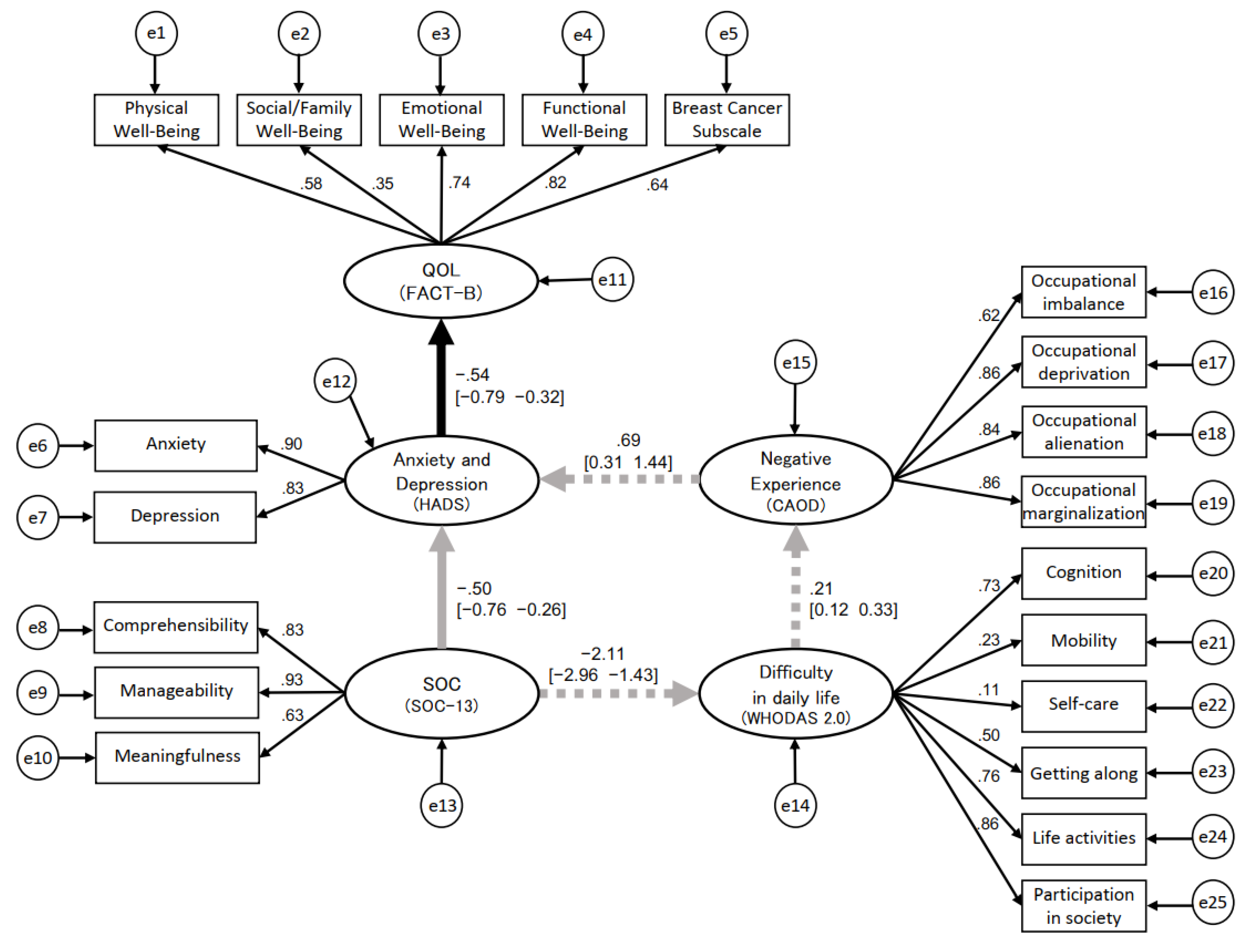

3.3. Structural Relationship of QOL, Anxiety and Depression, SOC, Difficulty in Daily Life, and Negative Experience

The results of the post hoc power analysis in SEM showed that a sample size of n = 73 was associated with a power = 95.4% to reject a wrong model (with df = 147) with an amount of misspecification corresponding to RMSEA = 0.08 based on α = 0.05. From the above results and previous studies, a hypothetical model of causality in QOL was developed (

Figure 1), following which the BSEM was used. The latent variables were “QOL,” “anxiety and depression,” “SOC,” “difficulty in daily life,” and “negative experience,” and the observed variables were the scores on the sub-items of each assessment scale. The convergence statistic of the Bayesian estimation was 1.000–1.002, which was stable. The PPP was 0.20, which was better than 0.10, indicating a satisfactory value. The standardized path coefficients [95% CI] between each latent variable in the BSEM were -0.50 [-0.76, -0.26] from “SOC” to “anxiety and depression” and -0.54 [-0.79, -0.32] from “anxiety and depression” to “QOL” as the direct effects, both significant. The direct effect from “SOC” to “QOL” via “anxiety and depression” was 0.274 (-0.50 × -0.54). The indirect effects from “SOC” to “difficulty in daily life” was -2.11 [-2.96, -1.43], from “difficulty in daily life” to “negative experience” was 0.21 [0.12, 0.33], and from “negative experience” to “anxiety and depression” was 0.69 [0.31, 1.44], all of which were significant. The indirect effect from “SOC” to “QOL” mediated by “difficulties in daily life” and “negative experience” was 0.163 (-2.11 × 0.21 × 0.69 × -0.54) (

Figure 2). Because the results of the multiple regression analysis indicated that age may also be involved in SOC, BSEM was performed with age added as an observed variable for SOC, but the results did not converge.

4. Discussion

In addition to the direct association supporting the conventional finding that improvement in SOC, which is the individual’s ability to cope with stress, leads to improvement in QOL mediated by anxiety and depression, an indirect association was indicated showing that a decrease in difficulty in daily life and impaired negative experience leads to improvement in QOL mediated by anxiety and depression for the structural relationship of QOL in survivors of breast cancer. The direct association from “SOC” to “QOL” via “anxiety and depression” supported the findings of previous studies [

5,

6,

7]. The direct effect of this study was 0.274, which was almost comparable to the results of previous studies conducted in other cultures, such as by Zamanian et al. [

30] and Rohani et al. [

31]. According to Antonovsky [

4], SOC fosters the ability of an individual or group to successfully cope with stressors and life crises and to realize the growth potential they harbor. SOC is acquired through positive environments or life experiences until approximately 30 years of age. Subsequent life experiences can change SOC, and SOC can be improved by intervention programs based on SOC theory [

32]. Therefore, for persons with low SOC, this intervention program may increase their SOC, improve their levels of anxiety and depression, and thus improve their QOL. However, the indirect effect was 0.163. Comparing the path coefficients in previous studies using SEM, the path coefficient between WHODAS 2.0 and SOC-13 was -0.178 in the Moen et al. [

33] study of rehabilitation patients and was smaller than the path coefficient between variables in the present study. In a study of healthcare workers by Teraoka and Kyougoku [

17], the path coefficient between CAOD and Depression was 0.745, which was similar to the path coefficient in the present study. The path coefficient of WHODAS 2.0 and CAOD was 0.598 in the Watanabe et al. study [

34] of severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI), whereas that in the present study was smaller. The previous studies have used different participants, and to our knowledge, no previous studies have verified these structural relationships in participants with breast cancer, making the present study the first to do so. Although the indirect effect in this study was smaller than the direct effect, the possibility was indicated that QOL could be improved by providing support using the indirect effect to “anxiety and depression” mediated by “difficulty in daily life” and “negative experience.” The reason for the lack of convergence of the BSEM with the addition of age is thought to be due to the limited age range of the study participants and to the bias of the participants because they were recruited from SHGs. As mentioned previously [

32], although SOC is established by around age 30 and may change thereafter, age bias as a disease characteristic was undeniable.

Establishing psychosocial support strategies in the context of survivorship of breast cancer is important for improving QOL [

35]. As a direct effect, QOL can be enhanced by improving anxiety and depression, which can be done with pharmacotherapy, exercise therapy [

36], and psychotherapy [

37]. The Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) identified self-management as a priority topic for 2014–2018 [

38] and stated that it is important to support people in self-managing the symptoms and effects of cancer. Yamanaka et al. [

39] also reported that cancer patients need to self-manage their symptoms after outpatient treatment when opportunities for direct intervention by health care providers decrease and that this has been shown to improve QOL. However, these are organic aspects based on psychological indices, and various factors are involved. Further, it is difficult to use these coping methods by oneself unless the community and environment for implementing these methods are in place. Therefore, we found it necessary to construct a model that can approach survivors’ daily life and clarify the extent of the effect. Regarding indirect effects, in a report of the BSEM for SPMI, it was clarified that WHODAS 2.0 was involved in the improvement of recovery of patients with SPMI using CAOD as a mediating variable [

34]. This indicates the importance of capturing negative experiences as a meaning of difficulty in daily life rather than only the presence or absence of difficulty in daily life. Thus, CAOD is said to be a subjective factor in difficulty in daily life, and careful assessment of CAOD and intervention for problems in the four domains may improve anxiety and depression and QOL as well. The model in the present study provided valid information because it suggested that the provision of such information and practice by survivors may lead to improved QOL.

The participants in this study were survivors of primary breast cancer surgery for more than 2 years after surgery in the Japanese culture. The majority were survivors who had completed postoperative therapy, but some were still undergoing treatment at the time of the assessments. In addition, participants were included regardless of their experience with cancer recurrence. Therefore, different cultures, treatment statuses, and experiences with cancer recurrence may lead to differences in the results of the assessments. There were selection biases that need to be carefully considered to determine whether the insights gained from this model can be generally applied. Furthermore, Alagizy et al. [

40] reported that postoperative patients with breast cancer who were married had higher moderate or severe anxiety and depression than breast cancer patients who were single, and among patients with breast cancer, those who were unemployed had significantly higher anxiety than those who were employed. Thus, the analysis may need to take into account the different post-treatment periods and environments of the participants. However, to the best of our knowledge, the results of this study represent a new model of care strategy that should help to identify specific strategies to improve QOL in terms of difficulty in daily life. In addition, the relationship between difficulty in daily life and QOL in the immediate postoperative period may show a different degree of efficacy. The results of this study can be useful as basic comparative information because the model was constructed and validated on the basis of standardized rating scales.

5. Conclusions

The present empirical research has shown a structural relationship between QOL mediated by difficulties in daily life and negative experience in survivors of breast cancer. The present model indicates that difficulty in daily life and negative experiences are mediating variables and that support not only directly decreases difficulty in daily life but also addresses the negative experience as a subjective aspect that arises from difficulty in daily life that may improve QOL. These direct and indirect approaches to addressing difficulties in daily life are very significant because they can provide a basis for the development of support strategies to increase QOL. Expected research in the future would be based on a longitudinal study to examine whether difficulty in daily life could affect changes in QOL.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study's conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by A.W., T.K.(Takayuki Kawaguchi), A.N., S.S., N.K., T.M., and T.K. (Takeshi Kobayashi). Analysis was performed by A.W. and T.K. (Takayuki Kawaguchi). The first draft of the manuscript was written by A.W. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Research Grants from Nihon Institute of Medical Science Presidential Research Grants.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the participants and the staff at each SHG in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, Graham J, Richards M, Ramirez A. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005, 330, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeely ML, Campbell KL, Rowe BH, Klassen TP, Mackey JR, Courneya KS. Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2006, 175, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki K, Hayashi N, Hayashi E, Fukawa A. Sense of Coherence in Cancer Patients: a Literature Review. Osaka Medical College Journal of Nursing Research. 2017, 7, 3–13. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. 1987: Jossey-Bass.

- Rohani C, Abedi HA, Sundberg K, Langius-Eklöf A. Sense of coherence as a mediator of health-related quality of life dimensions in patients with breast cancer: a longitudinal study with prospective design. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kenne Sarenmalm E, Browall M, Persson LO, Fall-Dickson J, Gaston-Johansson F. Relationship of sense of coherence to stressful events, coping strategies, health status, and quality of life in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2013, 22, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drageset J, Eide GE, Hauge S. Symptoms of depression, sadness and sense of coherence (coping) among cognitively intact older people with cancer living in nursing homes-a mixed-methods study. PeerJ. 2016, 4, e2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Rehm J, Kennedy C, Epping-Jordan J, et al. Developing the World Health Organization disability assessment schedule 2.0. Bull World Health Organ. 2010, 88, 815–823.

- Tazaki M, Yamaguchi T, Yatsunami M, Nakane Y. Measuring functional health among the elderly: development of the Japanese version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II. Int J Rehabil Res. 2014, 37, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço A, Dantas AAG, de Souza JC, Araujo CM, Araujo DN, Lima INDF, et al. Sleep quality is associated with disability and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a cross-sectional pilot study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2021, 30, e13339. [Google Scholar]

- Chachaj A, Małyszczak K, Pyszel K, Lukas J, Tarkowski R, Pudełko M, et al. Physical and psychological impairments of women with upper limb lymphedema following breast cancer treatment. Psychooncology. 2010, 19, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao HP, Liu Y, Li HL, Ma L, Zhang YJ, Wang J. Activity limitation and participation restrictions of breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: psychometric properties and validation of the Chinese version of the WHODAS 2.0. Qual Life Res. 2013, 22, 897–906.

- Pösl M, Cieza A, Stucki G. Psychometric properties of the WHODASII in rehabilitation patients. Qual Life Res. 2007, 16, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teraoka M, Kyougoku M. Development of the Final Version of the Classification and Assessment of Occupational Dysfunction Scale. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0134695. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend E, Wilcock AA. Occupationaljustice and client-centred practice: a dialogue in progress. Can J Occup Ther. 2004, 71, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teraoka M, Kyougoku M. Analysis of structural relationship among the occupational dysfunction on the psychological problem in healthcare workers: a study using structural equation modeling. PeerJ. 2015, 3, e1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teraoka M, Kyougoku M. Causal relationship between occupational dysfunction and depression in healthcare workers: a study using structural equation model. PeerJ PrePrints. 2015, 3, e787v1. [Google Scholar]

- Katz AH, Bender EI. Self-help groups in Western society: History and prospects. J Appl Behav Sci. 1976, 12, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmatsu, S. My Study Note ― Peer Support in Cancer Patients Groups ―. Acta Med Hyogo. 2014, 38, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, Strahan EJ. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol Methods. 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobst LJ, Bader M, Moshagen M. A tutorial on assessing statistical power and determining sample size for structural equation models. A tutorial on assessing statistical power and determining sample size for structural equation models. Psychol Methods. 2021, Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Brady, M. J, Cella DF, Mo F, Bonomi AE, Tulsky DS, Lloyd SR, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997, 15, 974–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togari T, Yamazaki Y, Nakayama K, Yokoyama Y, Yonekura Y, Takeuchi T. Nationally representative score of the Japanese language version of the 13-item 7-point sense of coherence scale. Japanese Journal of Public Health. 2015, 62, 232–237. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. MPR-online. 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg RJ, Lance CE. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organ Res Methods. 2000, 3, 4–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods. 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng L, Yang M, Marcoulides KM. Structural equation modeling with many variables: a systematic review of issues and developments. Front Psychol. 2018, 9, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain MK, Zhang Z. Fit for a Bayesian: an evaluation of PPP and DIC for structural equation modeling. Struct Equ Modeling. 2019, 26, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanian H, Amini-Tehrani M, Jalali Z, Daryaafzoon M, Ramezani F, Malek N, et al. Stigma and quality of life in women with breast cancer: mediation and moderation model of social support, sense of coherence, and coping strategies. Front Psychol. 2022, 18, 657992. [Google Scholar]

- Rohani C, Abedi HA, Omranipour R, Langius-Eklöf A. Health-related quality of life and the predictive role of sense of coherence, spirituality and religious coping in a sample of Iranian women with breast cancer: a prospective study with comparative design. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg KA, Björkman T, Sandman PO, Sandlund M. Influence of a lifestyle intervention among persons with a psychiatric disability: a cluster randomised controlled trail on symptoms, quality of life and sense of coherence. J Clin Nurs. 2010, 19, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moen VP, Eide GE, Drageset J, Gjesdal S. Sense of coherence, disability, and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study of rehabilitation patients in Norway. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019, 100, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe A, Kawaguchi T, Sakimoto M, Oikawa Y, Furuya K, Matsuoka T. Occupational dysfunction as a mediator between recovery process and difficulties in daily life in severe and persistent mental illness: a Bayesian structural equation modeling approach. Occup Ther Int. 2022, 2022, 2661585. [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza MS, O'Mahony J, Karkada SN. Effectiveness and meaningfulness of breast cancer survivorship and peer support for improving the quality of life of immigrant women: a mixed methods systematic review protocol. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2021, 10, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arent SM, Walker AJ, Arent MA. The effects of exercise on anxiety and depression. The effects of exercise on anxiety and depression. Handbook of Sport Psychology. 2020, 872–890. [Google Scholar]

- Zeppegno P, Krengli M, Ferrante D, Bagnati M, Burgio V, Farruggio S, et al. Psychotherapy with music intervention improves anxiety, depression and the redox status in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knobf MT, Cooley ME, Duffy S, Doorenbos A, Eaton L, Given B, et al. The 2014-2018 Oncology Nursing Society Research Agenda. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015, 42, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka M, Suzuki K. Educational Intervention for Promoting Self-management of Patients with Cancer Pain: A Literature Review. Palliative Care Research. 2018, 13, 7–21. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagizy H, Soltan MR, Soliman SS, Nashat N. Anxiety, depression and perceived stress among breast cancer patients: single institute experience. Middle East Current Psychiatry. 2020, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).