1. Introduction

This state-of-the-art article focuses on screening for the most common asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic vascular disorders in the over 50-60 years old population to prevent dreadful complications using medical, endovascular, or surgical therapy (that is, secondary prevention). Therefore, for each vascular disease described in this article we aim to answer two questions: 1) what and to whom screening for, and 2) how to prevent cardiovascular complications.

2. Relevant sections

2.1. Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

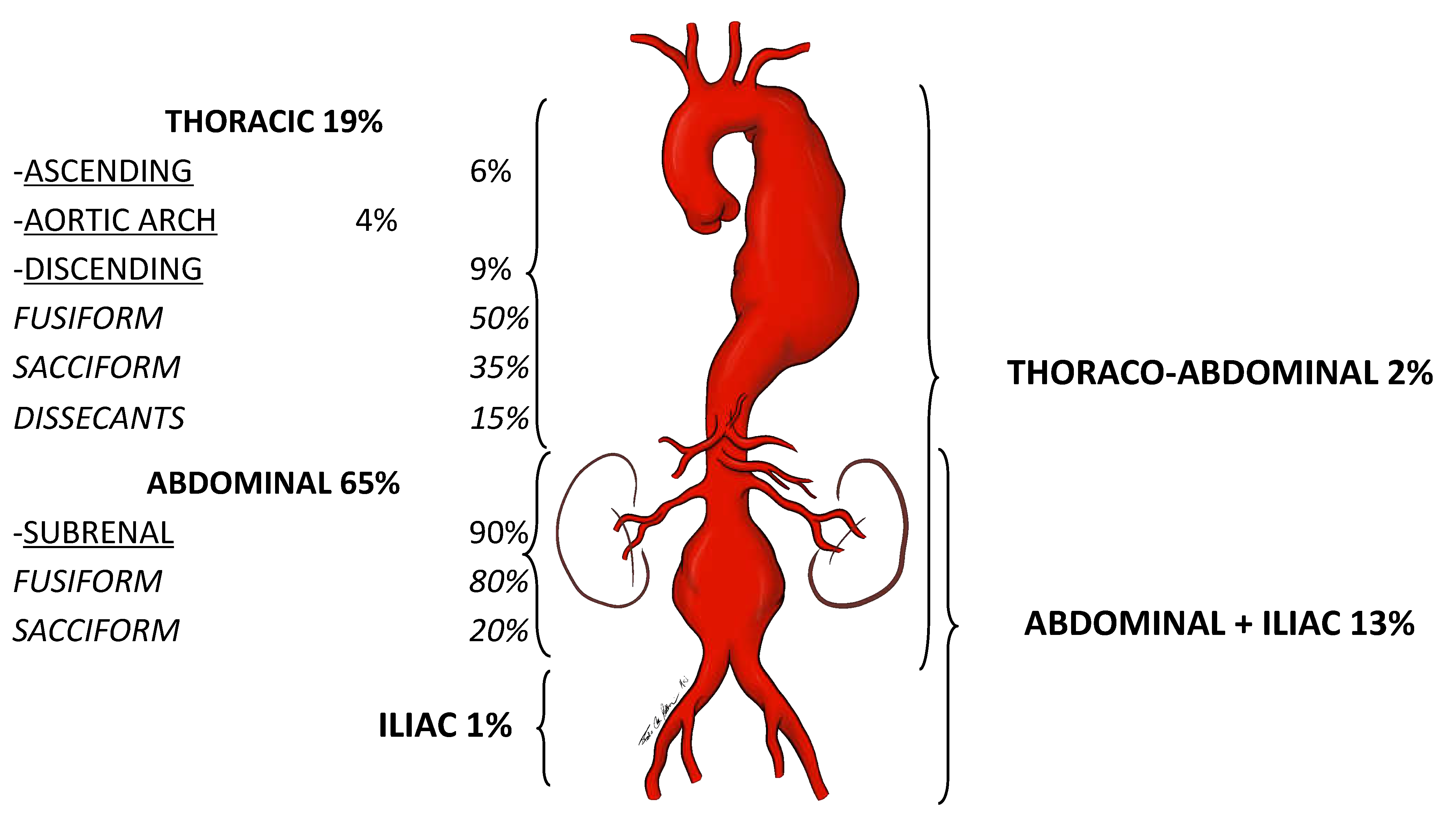

1) An artery is defined as an aneurysm if its maximal transverse diameter exceedsthe average diameter by at least 50%. Around 80% of the aneurysms of the aorta exclusively or in part involve the abdominal portion: compared to thoracic aorta aneurysms, AAAs are easier to diagnose. Almost 90% of AAA are localized below the renal arteries (

Figure 1).

The diameter of the infrarenal aorta in normal adults ranges between 1.41-2.39 cm in men and 1.19-2.16 cm in women: therefore, we should refer to the diameter of the infrarenal aorta immediately above the dilation of the aorta, before eventually declaring that that dilation is effectively an AAA.

AAAs are almost always asymptomatic. Endovascular or open treatment is indicated when the maximal transverse diameter reaches or exceeds 5.5 cm. At this dimension, the annual rupture rate is 5-10% per year, which is higher than the estimated rate of elective operative complications (around 2-5% in dedicated vascular centers). In addition, the rupture rate increases proportionally with the growth of the AAA [

1]. On the other hand, a ruptured AAA (rAAA) rarely gives a warning and primarily affects the male patient, and the overall mortality rate can be up to 81% [

2,

3]. This is why detecting an asymptomatic AAA practically means saving patient's life. Establishing an efficient and cost-effective screening methodology for asymptomatic AAA is paramount since it allows early detection, surveillance, and intervention to prevent rAAA. During a routine physical examination, the abdomen's palpation is a fundamental principle in searching for an abnormal pulsating mass in the mesogastrium (

Figure 2).

Then, the eventual clinical suspect of an AAA needs to be confirmed by a first-level investigation, such as a duplex scan, which has a very high specificity (almost 100%) and sensitivity (95%) to detect an AAA (

Figure 3) [

4].

The etiopathogenesis of AAA is considered multi-factorial, involving inflammation, proteolysis, vascular smooth muscle apoptosis, and the following risk factors: male sex, older age, tobacco use, family history, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and history of other aneurysms [5-8].

A meta-analysis of population-based randomized control trials (RCTs) established that screening of men ≥ 65 yo was associated with both increased rates of AAA detection and elective repair and both lower AAA-related mortality and rAAA incidence up to 15 yrs [

9]. Similar results were shown in a recent scoping review, which also reported the cost-effectiveness of reducing emergency rAAA treatment, but also outlined a few potential harms of older male AAA screening: no AAA mortality or morbidity screening-related benefits, negative impact on men's quality of life, inconsistent application of AAA screening recommendations by primary care practitioners, and tendency to repair AAAs smaller than the recommended threshold [

10,

11].

Since current studies have demonstrated an overall decline in AAA prevalence, there is a need for a customized AAA screening age range for older adult men, who should be evaluated individually by taking risk factors and estimated life expectancy into account [

12-14]. The family history of AAA should be better investigated to address the correct screening. A study from Sweden and Denmark pointed out a 24% incidence in the monozygotic twin of an AAA patient; incidence seemed to increase in the case of women; these AAAs grew up faster and could rupture even if smaller than 5 cm [

15]. Hopefully, the results of an ongoing Swedish study will answer some open questions, such as screening for AAA in older siblings, women included. Regarding these latter, most of the studies on this topic investigated only more senior men, likely because the proportion of women with an intact AAA is low compared to men (1,4-6 ratio). Still, their rate of rupture is higher [

16,

17]. Some Danish colleagues have recently underlined the need for better screening for AAA in women. They noticed poor agreements in duplex scan-based absolute diameters concerning aortic ectasias, small AAAs, and large AAAs in women, indicating that the current absolute cut-points do not reflect female anatomy [

18]. Colleagues from the University of Pittsburg (PA, USA) demonstrated that among 632 patients who had undergone treatment for rAAA in 17 years, residing in the most deprived neighborhoods was associated with a greater probability of presenting rAAA under age 65 and, therefore, may benefit from younger screening age [

19]. A Swiss study showed that among 213 consecutive rAAA emergently operated between 1998 and 2005, all patients had been seen by their general practitioner or a cardiologist within a year before the presentation. Therefore, they may have benefited from AAA screening [

20].

Regarding aortic ectasia (i.e., with an absolute diameter between 2.5 – 2.9 cm), due to cost-containment, Sweden is the only country that recommends follow-up surveillance at five years [

21]. About one-quarter of aortic ectasias can develop into AAA greater than 5.5 cm at ten years and eventually ruptures [

22,

23].

2) To prevent rupture, AAAs ≥ 5-5.5 cm undergo evaluation for operative treatment, while AAA < 5-5.5 cm enter a follow-up program. Aneurysm diameter remains a well-established parameter for clinical decision-making.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and active smoking are risk factors associated with AAA development [

24]. AAA annual growth rate is increased in smokers (by 0.35 mm/year), decreased in patients with diabetes (by 0.51 mm/year), and is correlated to the diameter (around 1.3 mm for 3 cm AAA, 3.6 mm for those of 5 cm), and does not significantly differ between the genders. The risk of AAA rupture is increased substantially in women, older patients, in those with lower body mass index (BMI) or higher blood pressure (BP) [

25].

2.2. Extracranial internal carotid stenosis (EICS)

1) Around 85% of strokes are of ischemic origin, and 15-20% of all strokes are due to atherosclerotic obstructive lesions of the EICS [

26]. Therefore, treating EICS due to an atherosclerotic plaque means secondary prevention of cerebral ischemia.

The pathogenetic mechanism is mainly embolic or related to cerebral hypoperfusion in case of severe occlusive disease in both the carotid and vertebral arteries. Atrial fibrillation is another major cause of cerebral embolization, causing more transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) than strokes; these latter are less sudden, disabling, and lethal than strokes of carotid origin [

27].

A meta-analysis of four population-based studies reported a 3.1% prevalence of severe asymptomatic EICS in the general population. Analyzing in detail, EICS prevalence related to age and sex, a large USA and UK population screening of 2.5 million people revealed that the prevalence of EICS is 2% and 2.3% between ages 60-69, 3.6% and 6% for age 70-79, and 5% and 7.5% when >80 years old, for women and men, respectively. The probability of detecting an EICS is three times higher in smokers, more than two times higher if systolic arterial pressure >160 mmHg, and in diabetics, 40% higher for each one mmol/l increase of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, 40% lower for each one mmol/l increase of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, 75% higher for doubling of triglycerides, 20% more elevated for each 5-unit increase of the body mass index >25 kg/m

2 [

28]. A patient older than 65 with two or more risk factors is at high cardiocerebrovascular risk and should be screened with a duplex scan, and patients with coronary artery disease or arterial disease in other districts.

2) What makes the difference in stroke prevention in a patient with EICS is if the patient is asymptomatic or symptomatic for congruous hemispheric or retinal ischemia in the last three months [

29]. It is well established that symptomatic carotid stenosis is best managed with intervention, either by carotid endarterectomy or stenting. In the short term, TIA precedes 15% of ischemic strokes [

30]. Independent risk factors are age greater than 60 years, diabetes mellitus, focal symptoms, and TIAs that last longer than 10 minutes [

31].

On the other hand, the optimal management of asymptomatic carotid stenosis is still controversial. An asymptomatic >50% EICS (North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial -NASCET- criteria) carries a 1% annual risk of stroke. Most of the merits of this low incidence are due to the development of the best medical therapy (BMT, the combination of statins, antiplatelet, and anti-hypertensive drugs). Every 10% decrease in LDL cholesterol reduces the risk of stroke by 15% in patients with EICS [

32]. Low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (81 mg qd) is the most commonly used cardiovascular prophylaxis. Every ten mmHg increase in BP worsens the risk of stroke by 30-45% [

33,

34]. Furthermore, smoking increases the risk of stroke by 1.5% [

35]. Therefore, in the last ten years, BMT has been more and more considered the treatment of choice for many asymptomatic EICS [

36,

37].

The risk of stroke increases according to the degree of EICS: those greater than 80% carry an annual risk of 4.8% [

28].

Duplex scan is a first-level investigation to determine the degree of EICS utilizing peak systolic velocity (

Figure 4).

In complex duplex visualization, as in the presence of a highly calcific carotid plaque causing an ultrasound shadow cone, the exact degree of EICS can be accurately measured by computed tomographic angiography (CTA) or, eventually, by digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Compared to this latter, CTA tends to underestimate the higher and moderate grade EICS [

38]; DSA is the gold standard to determine the extent of EICS, though more invasive. Either the NASCET criteria or European Carotid Surgery Trialists (ECST) criteria are used to calculate EICS (

Figure 5) [

39].

In the NASCET criteria, severe and moderate EICS is defined as 70%–99% and 50%–69% stenosis, respectively. In ECST criteria, severe and mild EICS is defined as 80%–99% and 70%–79% stenosis, respectively [

40]. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) represents a second-level instrumental examination in patients contraindicated to iodine-based contrast. MRA underestimates EICS since it is not as sensitive to calcification. On the other hand, gadolinium contrast-enhanced MRA can overestimate EICS since it is more impacted by artifacts [

41].

Together with the degree of EICS, another essential predictor of cerebral ischemia is identifying a vulnerable plaque. Intraplaque hemorrhage, discontinuous fibrous cap or frankly ulceration, echolucency at duplex scan, mural thrombus, neovascularization and inflammation, lipid-rich necrotic core, and microembolic signals at transcranial doppler can be associated with thromboembolism from the lipid core, and represents an indication to open or endovascular treatment [

42]. These plaque characteristics are found in 43.3% of symptomatic patients with EICS and only in 19.9% of the asymptomatic EICS [

43]. Detection of active inflammation in the lipid core of a carotid plaque is an indicator of unstable plaque and rupture-prone fibrous cap. Clinical observations suggest that the calcification of the lipid core is stable, while the less calcified atheroma is more prone to rupture. Therefore, chronic inflammation in a noncalcified plaque is crucial for atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability and disruption.

Chronic renal insufficiency is another risk factor for stroke in patients with asymptomatic EICS.

2.3. Lower extremity arterial disease (LEAD)

1) LEAD is a progressive atherosclerotic occlusion of the arteries of the lower limbs. If not medically treated, it can evolve into chronic limb-threatening ischemia, characterized by rest pain or tissue loss, which carries a high risk of major adverse limb events (MALE). Furthermore, LEAD is an independent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), that is, acute myocardial infarction and stroke. Its incidence increases significantly with age, showing a 20% prevalence peak in the over-80 population [

44].

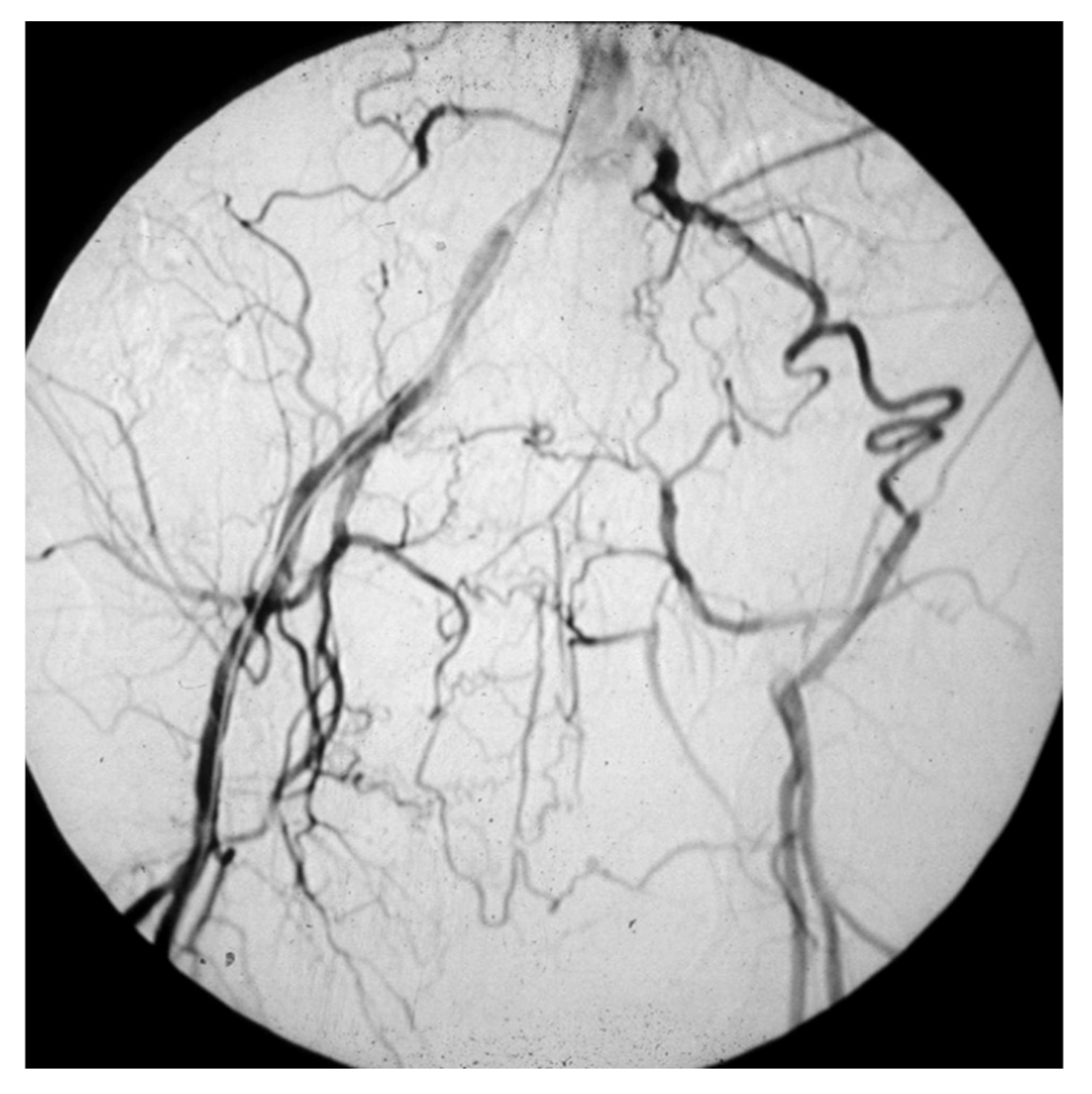

Fortunately, if compared to the vascular diseases dealt with before, LEAD is more symptomatic. However, only one-third of LEAD patients present the typical intermittent claudication (IC), a cramping pain in some muscles of the lower limbs, which arises while walking and recedes with ten minutes of resting. So, the problem stands in two categories of patients:

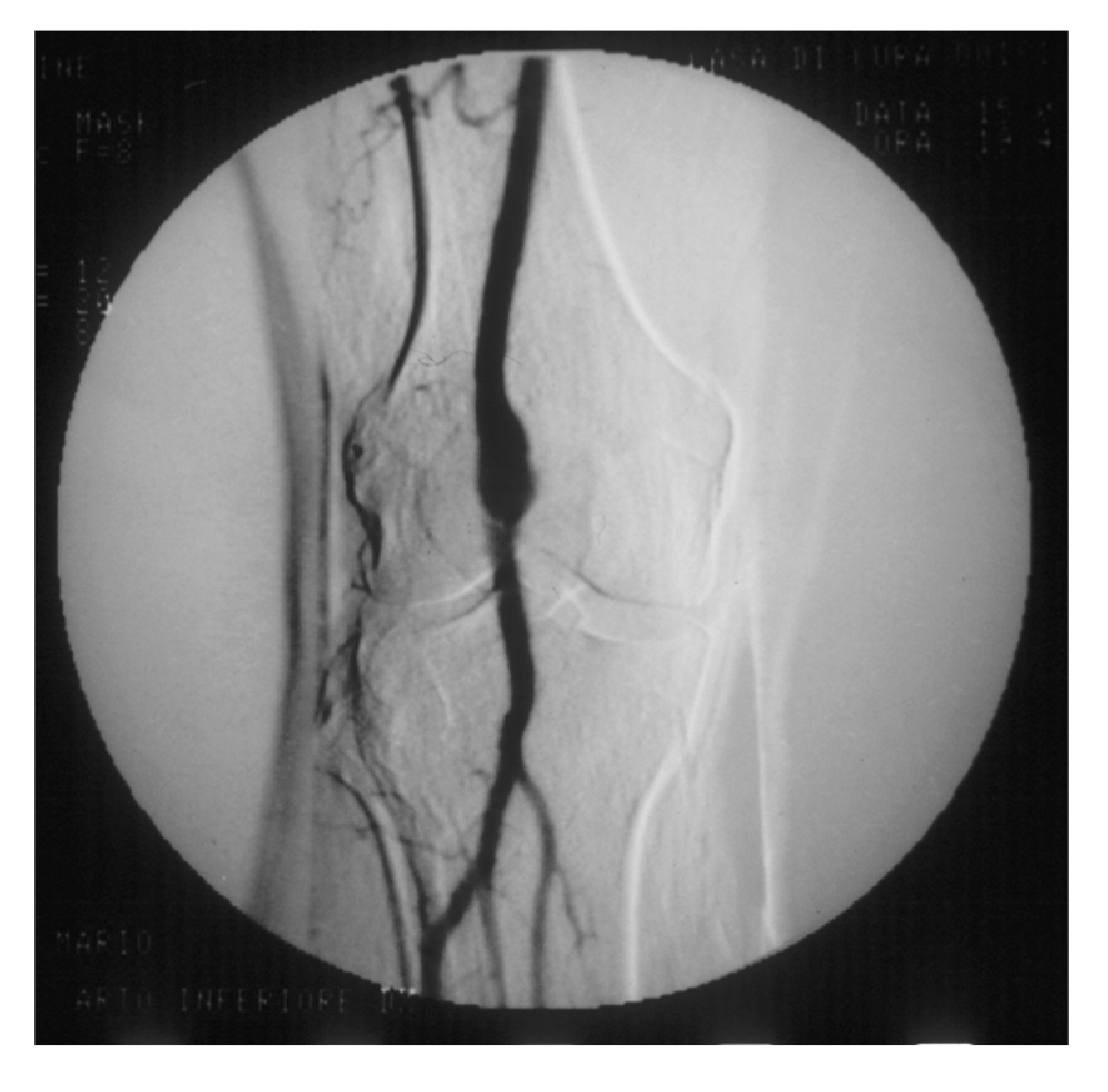

- those who have a masked LEAD, since they do not present IC: reasons range from the development of efficient arterial collateral circulation (

Figure 6) to limited mobility, up to bedridden [

45];

- 30-50% have atypical symptomatology due to the co-existence of other diseases, such as disc herniation, medullary stenosis, vertebral osteoarthritis, and peripheral neuropathy [

46].

These asymptomatic LEAD patients should also be identified to optimize atherosclerotic risk factors control and medical therapy to reduce their silent risk of cardiovascular mortality. LEAD must be suspected in adults with diabetes mellitus, which carries a four-fold risk compared to the general population [

47]; cigarette-smoking, two-fold risk [

48]; high BP, the strongest predictor of LEAD [

49]; hyperlipemia [

50]; familiarity [

51]; and hyperfibrinogenemia [

52]. Furthermore, the prevalence of LEAD is higher in patients with chronic renal function impairment, and increases moving from mild to severe degrees [

53].

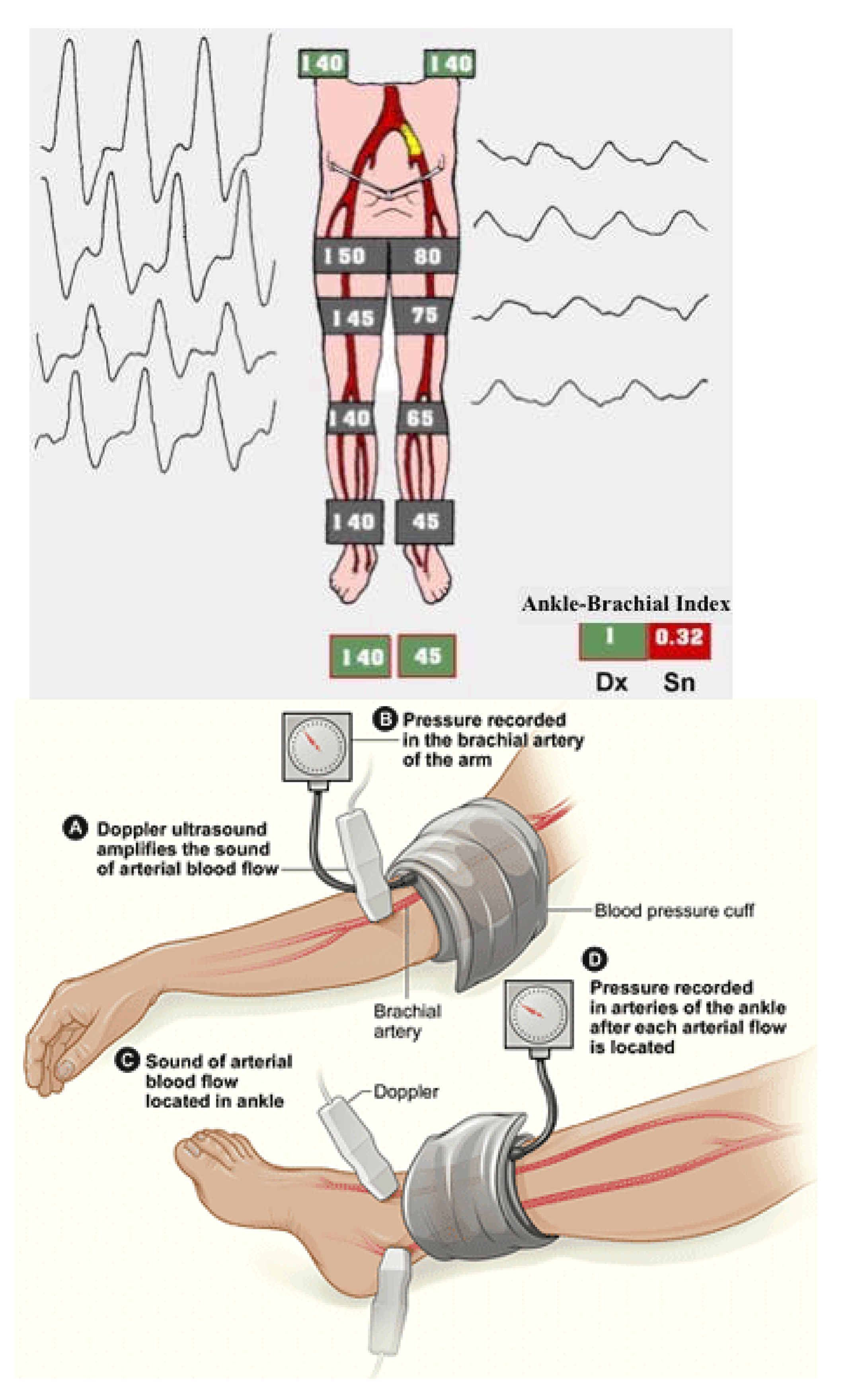

After an exhaustive clinical history and an accurate physical examination, the ankle-brachial index (ABI) is the easiest way to confirm the clinical suspect of LEAD or its screening. It is the ratio between two systolic BP registered utilizing continuous wave Doppler in the supine patient, the one on an artery at the ankle, and the systemic one. A typical value is around 1-1.1, even up to 1.3, and LEAD is diagnosed if ABI is less than 0.9 (

Figure 7).

The reduction in ABI's value is directly proportional to the stage of the atherosclerotic disease, the risk of MACE, MALE, and walking impairment [

46]. ABI can result paradoxically higher than 1.3 in subjects affected by diabetes or uremia due to the stiffness of their tibial arteries. The toe-brachial index (TBI) gives these patients more realistic values. TBI less than 0.7 is diagnostic for LEAD [

54]. Sometimes ABI can be normal, even if the suspicion of LEAD is high. In these cases, a treadmill test can be helpful: if the following ABI shows a 20% reduction compared to the value at rest, LEAD is confirmed [

55].

2) If LEAD is confirmed, prevention of MACE and MALE should be accomplished utilizing a multidisciplinary team based on cardiologists, endocrinologists, nephrologists, vascular medicine physicians, and vascular surgeons. These latter are the only ones who can offer a broad portfolio of therapeutic options in symptomatic LEAD patients, from medical to surgical treatment, from endovascular to open access or hybrid revascularization.

Glycated hemoglobin should be between 6.5% - 7.5% [

56]. Smoking cessation is associated with a significative MACE reduction and improved functional outcomes and MALE in patients with IC. Systemic BP should be stabilized at 130/80 mmHg. The LDL cholesterol level inversely correlates with ABI, and should be kept to less than 55 mg/dl in patients at high cardiovascular risk. Intensive statin therapy, such as atorvastatin 40-80 mg or rosuvastatin 20-40 mg qd, is recommended in these patients to reduce the risk of MACE and MALE and to improve the walking distance in the LEAD patients with IC. Antiplatelet therapy with low-dose (100 mg qd) acetylsalicylic acid, or ideally clopidogrel 75 mg qd, is strongly recommended to reduce the risk of ischemic events [

45,

46,

57].

Vitamin K antagonist (warfarin) can reduce MACE, but the related risk of bleeding is not easy to be managed. Instead, the combined therapy of low-dose (2.5 mg bid) of rivaroxaban (one of the four oral anticoagulants non-vitamin K antagonist) plus acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg qd has shown to reduce the risk of MACE and MALE compared to low-dose aspirin alone in symptomatic LEAD patients [

58,

59].

2.4. Popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA)

1) The diameter of the popliteal artery in normal adults ranges between 0.7-1.1 cm in men and 0.5-0.9 cm in women. Therefore, dilation of the popliteal artery is a PAA when its maximal transverse diameter exceeds the standard diameter of the popliteal artery immediately above the dilation by at least 50%.

PAA incidence in the general population can reach almost 3%, and men represent more than 90%.

Almost 50% of the PAAs are bilateral, and over one-third are associated with AAA [

60,

61]. On the other hand, the incidence of a PAA in patients with an AAA is up to 11% [

62].

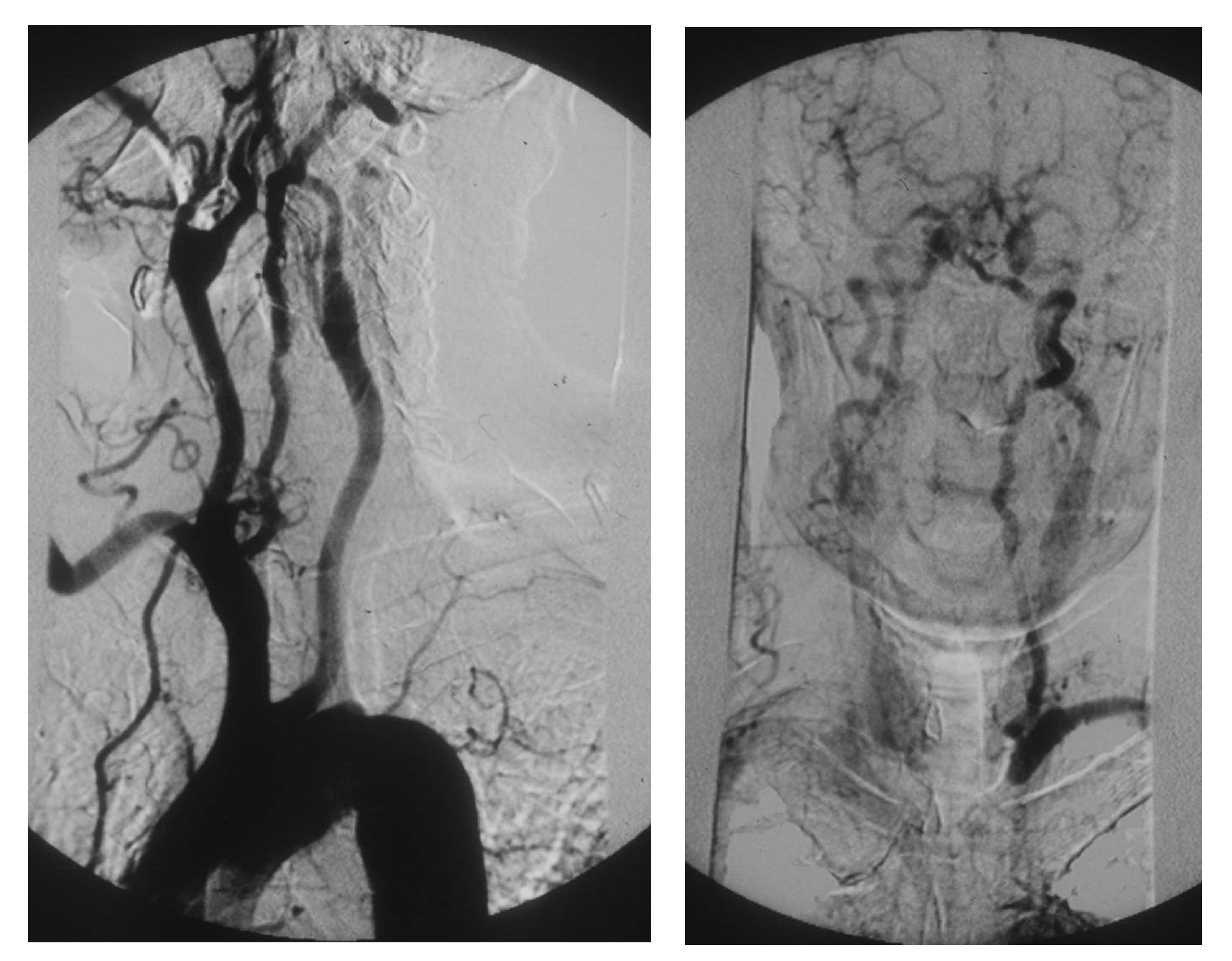

PAAs should be detected, not much for the risk of rupture, which is rare, but for their risk of embolization and thrombosis. The physiologic flexion of the knee can act as a tremendous stress for the parietal thrombus of the PAA, potentially causing paroxysmal, multiple, and insidious episodes of asymptomatic microembolization to the tibial arteries (

Figure 8).

As a consequence, these latter can progressively obstruct, drastically reducing the run-off of the popliteal artery and giving rise to clinical picture ranging from blue toe syndrome, or LEAD with IC up to chronic limb-threatening ischemia. These patients may be clinically indistinguishable from those presenting with LEAD. Therefore a careful examination is required to distinguish chronically symptomatic PAA patients from those with symptoms due to LEAD.

PAA can also thrombose entirely due to the affected tibial out-flow, so it manifests itself with acute lower limb ischemia: limb loss can reach 14% in these patients [

60,

63].

Physical examination searching for a pulsating mass in the popliteal lozenge is diagnostic for two-thirds of the PAAs, while a duplex scan has close to 100% diagnostic accuracy. Particular attention for screening must be given to patients with a personal or familial history of PAA (eventually contralateral), AAA, or aneurysms in other districts. Around 40% of PAAs are asymptomatic when detected, but up to 24% will become symptomatic in the next 1-2 years [

64,

65].

2) PAAs less than 2 cm in maximal transverse diameter can grow up to 1.5 mm annually [

60]. As for the other arterial diseases, these patients should cease smoking and control hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, as part of an atherosclerotic factor control strategy.

PAA greater than 2 cm grows up to 3 mm annually and should be fixed in an open or endovascular fashion [

66]. However, two more factors indicate surgical treatment: the presence and amount of the parietal thrombus and the poor distal run-off.

2.5. Renal artery stenosis (RAS)

1) Most RAS are atherosclerotic, much less due to fibromuscular dysplasia or dissection. RAS' prevalence, incidence, and natural history are largely unknown. An autoptic study reported 6% in under-55 years old patients and 40% in over-75 [

67]. At three years, RAS less than 60% showed progression to severe RAS in 40% of cases, and RAS greater than 60% showed progression to occlusion in 7% of patients [

68].

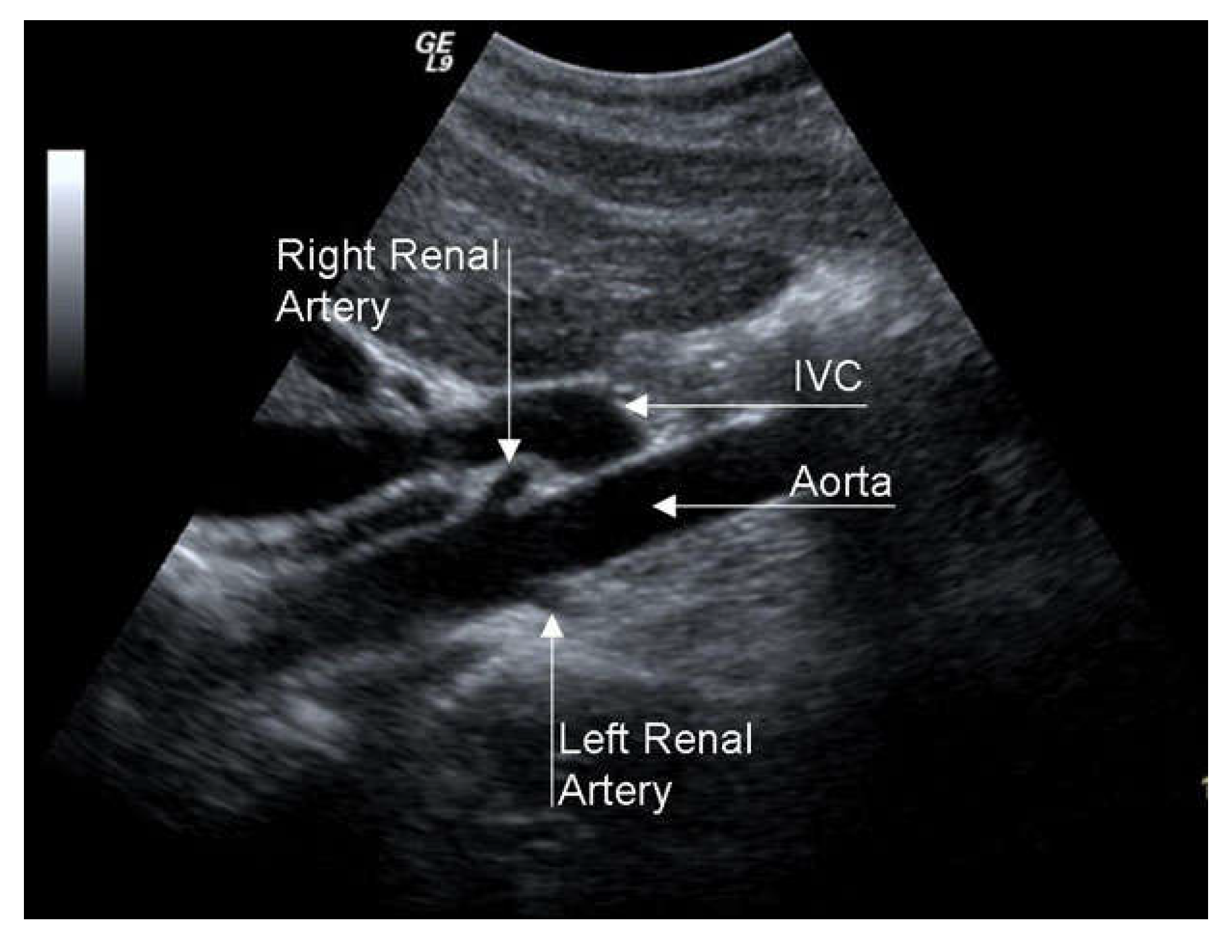

RAS is associated with renovascular hypertension (RVH) and chronic renal insufficiency (CRI), so it configures the clinical picture of renovascular disease (RVD). RAS greater than 50% causes dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone mechanism, which can cause RVH. The differential diagnosis between RVH and essential hypertension is difficult since specific symptoms and signs are lacking. However, RVH should be suspected in some patients since, if not adequately pharmacologically controlled, in the long-term, it brings parenchymal alterations, even in the contralateral kidney, with reduced excretory capacity. The search for RAS passes through a high propensity for clinical suspicion in severely hypertensive patients resistant to medical therapy (RVH is more resistant to pharmacological treatment than essential hypertension) with chronic renal insufficiency, advanced age, coronary artery disease, EICS, or LEAD. A duplex scan is an excellent examination for RAS screening, even if its efficacy is limited in obese patients or with intestinal meteorism (

Figure 9).

2) This complex cascade of events worsens the risk of MACE in patients with RAS. It justifies the indication of renal artery surgical revascularization in highly selected patients with severe ostial RAS, short RAS occlusion, AAA associated with RAS, or aneurysm of the renal artery associated with RAS.

Renal artery stenting seems inferior to a well-conducted BMT [

69]. The latter is aimed at reducing systemic BP, preserving the renal function, and preventing MACE, through substantial modifications of the patient's lifestyle (correct BMI, no smoking, salt and alcohol reduction, regular physical activity) and specific medications (angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics, β-blockers, antiplatelets, statins).

2.6. Prevertebral subclavian artery stenosis (PSAS)

1) A tight atherosclerotic stenosis (or occlusion) at the origin of the subclavian artery before the onset of its first collateral branch -the vertebral artery- can cause a brain stem blood steal during homolateral upper limb efforts, in favor of the latter, through a blood flow inversion in the homolateral vertebral artery itself. This condition is known as subclavian steal syndrome (SSS), which can acutely give rise to dramatic vertebrobasilar symptoms such as vertigo and lipothymia up to syncope (

Figure 10).

The prevalence of left PSAS is around 1.5% in the general population and over 11% in patients with LEAD. In comparison, right PSAS or brachiocephalic artery stenosis is less than one-quarter, and the former involves two-thirds of the time [

70,

71]. Given its peculiar hemodynamic pathophysiology, PSAS and SSS are mainly encountered in vasculopathics who are heavy workers or working with their upper limbs against gravity (ceiling restorers, orchestra directors, etc.).

Diagnosing PSAS is essential to prevent sudden and dangerous loss of consciousness due to SSS. An unknown significative PSAS alters homolateral BP measurement, whose consequences can be dramatic during surgical procedures or in long-term therapy management in hypertensive patients. In a patient with coronary artery bypass graft from the internal mammary artery or with axillo-femoral bypass, an unknown significative homolateral PSAS can also cause ischemic events in the heart of the lower limb, respectively. Furthermore, PSAS is an independent predictor of MACE [

72].

In addition to the clinical history, physical examination is of utmost importance in the search for PSAS since the clinical triad of differential BP of 15 mmHg between the upper limbs, subclavian bruit, and absence/hyposphygmia of the peripheral pulses in the homolateral upper limb is almost pathognomonic [

73]. In particular, a differential BP of 30-20 mmHg between the upper limbs carries a high risk of SSS. Then, the clinical suspicion of PSAS can be confirmed utilizing a duplex scan, which has excellent diagnostic accuracy for the origin of the subclavian artery.

2) Once detected, lifestyle measures and medical therapy common to other peripheral artery diseases (PADs) are sufficient to manage asymptomatic PSAS. On the other hand, PSAS symptomatic for SSS or potentially placing at risk a homolateral internal mammary or axillo-femoral bypass graft should be revascularized. In this regard, angioplasty and stenting is the first-line treatment, eventually followed in case of endovascular unsuccess by carotid-subclavian bypass or subclavian transposition on the common carotid artery.

3. Conclusions

In addition to patients affected by coronary artery disease (CAD), the adult population over 50-60 with one or more risk factors for atherosclerosis should be focused on discovering asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic arterial lesions such as AAA, LEAD, EICS, PAA, RAS, and PSAS. Accurate anamnesis and deep physical examination can lead to the clinical suspect, which is confirmed or excluded by duplex scan investigation in most cases. In case even one of those diseases is diagnosed, that patient is to be considered affected by vasculopathy and should be managed by medical, endovascular, or surgical approaches to reduce the risk of MACE and MALE.

4. Future Directions

Since the world population is aging, the medical community is called upon to raise more and more awareness that PADs are increasing. EICS, LEAD, RAS, and PSAS correlate with the risk of MACE, and their detection can bring to the discovery of silent CAD, reducing the risk of MACE itself. Since it is not realistic neither convenient to screen wide populations, accurate clinical history and deep physical examination remain key factors to select those individuals who should undergo first level instrumental investigations to confirm or exclude the clinical suspect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and supervision, E.M., I.E., M.Z., U.M.B., M.F., G.S., A.M.S.; Methodology and validation and investigation and writing—original draft preparation, E.M., I.E.; software and formal analysis and resources and data curation, A.R.M, T.M.; writing—review and editing and visualization, E.M., I.E., M.Z., U.M.B., M.F., G.S., A.R.M., T.M., A.M.S.; project administration, E.M.; funding acquisition, E.M.; A.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Edoardo Guarino, MEng, MSc for the English revision of this manuscript, and Fabio Massimo Calliari, MD, for the realization of Figure 1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chaikof, E.L.; Dalman, R.L.; Eskandari, M.K.; Jackson, B.M.; Lee, W.A.; Mansour, M.A.; Mastracci, T.M.; Mell, M.; Murad, M.H.; Nguyen, L.L.; et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2018, 67, 2–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimerink, J.J.; van der Laan, M.J.; Koelemay, M.J.; Balm, R.; Legemate, D.A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based mortality from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg 2013, 100, 1405–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, Y.; Hooda, K.; Li, S.; Goyal, P.; Gupta, N.; Adeb, M. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: pictorial review of common appearances and complications. Ann Transl Med 2017, 5, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keisler, B.; Carter, C. ; Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Am Fam Physician, 2015, 91, 538–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sakalihasan, N.; Michel, J.B.; Katsargyris, A.; Kuivaniemi, H.; Defraigne, J.O.; Nchimi, A.; Powell, J.T.; Yoshimura, K.; Hultgren, R. Abdominal aortic aneurysms. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2018, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, R.A.; Meecham, L.; Fisher, O.; Loftus, I.M. Ultrasound screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: current practice, challenges and controversies. Br J Radiol 2018, 91, 20170306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carino, D.; Sarac, T.P.; Ziganshin, B.A.; Elefteriades, J.A. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Evolving Controversies and Uncertainties. Int J Angiol, 2018, 27, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanhainen, A.; Verzini, F.; Van Herzeele, I.; Allaire, E.; Bown, M.; Cohnert, T.; Dick, F.; van Herwaarden, J.; Karkos, C.; Koelemay, M.; et al. Corrigendum to 'European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2019 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-iliac Artery Aneurysms' [European Journal of Vascular & Endovascular Surgery 57/1 (2019) 8-93], Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 2020, 59, 494. [CrossRef]

- Guirguis-Blake, J.M.; Beil, T.L.; Senger, C.A.; Coppola, E.L. Primary Care Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA, 2019, 322, 2219–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bains, P.; Oliffe, J.L.; Mackay, M.H.; Kelly, M.T. Screening Older Adult Men for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: A Scoping Review. Am J Mens Health 2021, 15, 15579883211001204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederle, F.A. The Last (Randomized) Word on Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. JAMA Intern Med, 2016, 176, 1767–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Zahl, P.H.; Siersma, V.; Jørgensen, K.J.; Marklund, B.; Brodersen, J. Benefits and harms of screening men for abdominal aortic aneurysm in Sweden: a registry-based cohort study. Lancet, 2018, 391, 2441–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olchanski, N.; Winn, A.; Cohen, J.T.; Neumann, P.J. Abdominal aortic aneurysm screening: how many life years lost from underuse of the medicare screening benefit? J Gen Intern Med, 2014, 29, 1155–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapila, V.; Jetty, P.; Wooster, D.; Vucemilo, V.; Dubois L,; Canadian Society for Vascular Surgery. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms in Canada: 2020 review and position statement of the Canadian Society for Vascular Surgery. Can J Surg, 2021, 64, E461–E466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joergensen, T.M.; Christensen, K.; Lindholt, J.S.; Larsen, L.A.; Green, A.; Houlind, K. Editor's Choice - High Heritability of Liability to Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: A Population Based Twin Study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 2016, 52, 41–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanhainen, A.; Lundkvist, J.; Bergqvist, D.; Björck, M. Cost-effectiveness of screening women for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg, 2006, 43, 908–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hultgren, R.; Fattahi, N.; Nilsson, O.; Svensjö, S.; Roy, J.; Linne, A. Evaluating feasibility of using national registries for identification, invitation, and ultrasound examination of persons with hereditary risk for aneurysm disease-detecting abdominal aortic aneurysms in first degree relatives (adult offspring) to AAA patients (DAAAD). Pilot Feasibility Stud, 2022, 8, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, J.S.S.; Obel, L.M.; Dahl, M.; Høgh, A.L.; Lindholt, J.S. Gender-specific predicted normal aortic size and its consequences of the population-based prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg, 2023, 91, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.R.; Andraska, E.A.; Reitz, K.M.; Habib, S.; Martinez-Meehan, D.; Dai, Y.; Johnson, A.E.; Liang, N.L. Association between neighborhood deprivation and presenting with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm before screening age. J Vasc Surg, 2022, 76, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, H.; Novak, J.; Dick, F.; Widmer, M.K.; Carrel, T.; Schmidli, J.; Meier, B. Prevention of rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Scand J Surg, 2010, 99, 217–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensjö, S.; Björck, M.; Wanhainen, A. Editor's choice: five-year outcomes in men screened for abdominal aortic aneurysm at 65 years of age: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 2014, 47, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, H.A.; Buxton, M.J.; Day, N.E.; Kim, L.G.; Marteau, T.M.; Scott, R.A.; Thompson, S.G.; Walker, N.M.; Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study Group. The Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) into the effect of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening on mortality in men: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2002, 360, 1531–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, J.B.; Stather, P.W.; Biancari, F.; Choke, E.C.; Earnshaw, J.J.; Grant, S.W.; Hafez, H.; Holdsworth, R.; Juvonen, T.; Lindholt, J.; et al. A multicentre observational study of the outcomes of screening detected sub-aneurysmal aortic dilatation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 2013, 45, 128–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, K.C.; Anderson, R.C.; Smothers, H.C.; Sood, K.; Irwin, Z.T.; Wilson, M.D.; Lee, E.S. Risk of developing an abdominal aortic aneurysm after ectatic aorta detection from initial screening. J Vasc Surg, 2020, 71, 1913–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeting, M.J.; Thompson, S.G.; Brown, L.C.; Powell, J.T.; RESCAN collaborators. Meta-analysis of individual patient data to examine factors affecting growth and rupture of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg, 2012, 99, 655–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Bruno, A.; Feasby, T.; Holloway, R.; Benavente, O.; Cohen, S.N.; Cote, R.; Hess, D.; Saver, J.; Spence, J.D.; et al. Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Carotid endarterectomy--an evidence-based review: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 2005, 65, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arboix, A.; Oliveres, M.; Massons, J.; Pujades, R.; Garcia-Eroles, L. Early differentiation of cardioembolic from atherothrombotic cerebral infarction: a multivariate analysis. Eur J Neurol, 1999, 6, 677–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Weerd, M.; Greving, J.P.; Hedblad, B.; Lorenz, M.W.; Mathiesen, E.B.; O'Leary, D.H.; Rosvall, M.; Sitzer, M.; Buskens, E.; Bots, M.L. Prevalence of asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis in the general population: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Stroke, 2010, 41, 1294–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroke Prevention and Educational Awareness Diffusion (SPREAD). Available online: http://www.iso-spread.it/capitoli/LINEE_GUIDA_SPREAD_8a_EDIZIONE.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Wu, C.M.; McLaughlin, K.; Lorenzetti, D.L.; Hill, M.D.; Manns, B.J.; Ghali, W.A. Early risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2007, 2417–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, W.; Wu, C.; Zhao, W.; Sun, H.; Hao, J.; Liang, H.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Jadhav, A.P.; Han, Y.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Recanalization Therapy for Acute Ischemic Stroke With Large Vessel Occlusion: A Systematic Review. Stroke, 2020, 51, 2026–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation, 2002, 106, 3143–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobs, A.S.; Nieto, F.J.; Szklo, M.; Barnes, R.; Sharrett, A.R.; Ko, W.J. Risk factors for popliteal and carotid wall thicknesses in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Epidemiol, 1999, 150, 1055–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, N.L.; Barzilay, J.I.; Shaffer, D.; Savage, P.J.; Heckbert, S.R.; Kuller, L.H.; Kronmal, R.A.; Resnick, H.E.; Psaty, B.M. Fasting and 2-hour postchallenge serum glucose measures and risk of incident cardiovascular events in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med, 2002, 162, 209–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, T.; Miller, T.; Ko, S. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: an update of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med, 2009, 150, 405–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antithrombotic Trialists' (ATT) Collaboration; Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, Buring J, Hennekens C, Kearney P. ; et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet, 2009, 373, 1849–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, A.L. Medical (nonsurgical) intervention alone is now best for prevention of stroke associated with asymptomatic severe carotid stenosis: results of a systematic review and analysis. Stroke, 2009, 40, e573–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvennoinen, H.M.; Ikonen, S.; Soinne, L.; Railo, M.; Valanne, L. CT angiographic analysis of carotid artery stenosis: Comparison of manual assessment, semiautomatic vessel analysis, and digital subtraction angiography. Am J Neuroradiol, 2007, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Bir, S.C.; Kelley, R.E. Carotid atherosclerotic disease: A systematic review of pathogenesis and management. Brain Circ, 2022, 8, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Ng, E.Y.; Lim, S.T. Imaging modalities to diagnose carotid artery stenosis: Progress and prospect. Biomed Eng Online, 2019, 18, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adla, T.; Adlova, R. Multimodality imaging of carotid stenosis. Int J Angiol 2015;24:179-84.

- Kolodgie FD, Yahagi K, Mori H, Romero ME, Trout HH Rd, Finn AV, Virmani R. High-risk carotid plaque: lessons learned from histopathology. Semin Vasc Surg, 2017, 30, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamtchum-Tatuene, J.; Noubiap, J.J.; Wilman, A.H.; Saqqur, M.; Shuaib, A.; Jickling, G.C. Prevalence of high-risk plaques and risk of stroke in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis: A meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol, 2020, 77, 1524–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowkes, F.G.; Rudan, D.; Rudan, I.; Aboyans, V.; Denenberg, J.O.; McDermott, M.M.; Norman, P.E.; Sampson, U.K.; Williams, L.J.; Mensah, G.A.; et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet, 2013, 382, 1329–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboyans, V.; Ricco, J.B.; Bartelink, M.E.L.; Björck, M.; Brodmann, M.; Cohnert, T.; Collet, JP.; Czerny, M.; De Carlo, M. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): Document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteriesEndorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO)The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J, 2018, 39, 763–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, U.; Nikol, S.; Belch, J.; Boc, V.; Brodmann, M.; Carpentier, P.H.; Chraim, A.; Canning, C.; Dimakakos, E.; Gottsäter, A. ESVM Guideline on peripheral arterial disease. Vasa 2019, 48, 1–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Peripheral arterial disease in people with diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2003, 26, 3333–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, G.C.; Lee, A.J.; Fowkes, F.G.; Lowe, G.D.; Housley, E. The relationship between cigarette smoking and cardiovascular risk factors in peripheral arterial disease compared with ischaemic heart disease. The Edinburgh Artery Study. Eur Heart J, 1995, 16, 1542–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, D.P.; Banerjee, A.; Fairhead, J.F.; Hands, L.; Silver, L.E.; Rothwell, P.M.; Oxford Vascular Study. Population-Based Study of Incidence, Risk Factors, Outcome, and Prognosis of Ischemic Peripheral Arterial Events: Implications for Prevention. Circulation, 2015, 132, 1805–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsimikas, S.; Karwatowska-Prokopczuk, E.; Gouni-Berthold, I.; Tardif, J.C.; Baum, S.J.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Shapiro, M.D.; Stroes, E.S.; Moriarty, P.M.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) Reduction in Persons with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med, 2020, 382, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassel, C.L.; Loomba, R.; Ix, J.H.; Allison, M.A.; Denenberg, J.O.; Criqui, M.H. Family history of peripheral artery disease is associated with prevalence and severity of peripheral artery disease: the San Diego population study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011, 58, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surma, S.; Banach, M. Fibrinogen and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases-Review of the Literature and Clinical Studies. Int J Mol Sci, 2021, 23, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, R.; Bracale, U.M.; Ielapi, N.; Del Guercio, L.; Di Taranto, M.D.; Sodo, M.; Michael, A.; Faga, T.; Bevacqua, E.; Jiritano, F.; et al. The Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on Peripheral Artery Disease and Peripheral Revascularization. Int J Gen Med, 2021, 14, 3749–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Criqui MH, Matsushita K, Aboyans V, Hess CN, Hicks CW, Kwan TW, McDermott MM, Misra S, Ujueta F; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; et al. Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Contemporary Epidemiology, Management Gaps, and Future Directions: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2021, 144, e171–e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirhamzeh, M.M.; Chant, H.J.; Rees, J.L.; Hands, L.J.; Powell, R.J.; Campbell, W.B. A comparative study of treadmill tests and heel raising exercise for peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 1997, 13, 301–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, W.K.; Erion, K.; Florez, J.C.; Hattersley, A.T.; Hivert, M.F.; Lee, C.G.; McCarthy, M.I.; Nolan, J.J.; Norris, J.M.; Pearson, E.R. Precision Medicine in Diabetes: A Consensus Report From the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care, 2020, 43, 1617–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, K.; Giugliano, R.P.; Blazing, M.A.; Park, J.G.; Tershakovec, A.M.; Sabatine, M.S.; Cannon, C.P.; Braunwald, E. Baseline Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Clinical Outcomes of Combining Ezetimibe With Statin Therapy in IMPROVE-IT. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2021, 78, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, S.S.; Bosch, J.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Connolly, S.J.; Diaz, R.; Widimsky, P.; Aboyans, V.; Alings, M.; Kakkar, AK.; Keltai, K.; et al. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in patients with stable peripheral or carotid artery disease: an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet, 2018, 391, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboyans, V.; Bauersachs, R.; Mazzolai, L.; Brodmann, M.; Palomares, J.F.R.; Debus, S.; Collet, J.P.; Drexel, H.; Espinola-Klein, C.; Lewis, B.S.; et al. Antithrombotic therapies in aortic and peripheral arterial diseases in 2021: a consensus document from the ESC working group on aorta and peripheral vascular diseases, the ESC working group on thrombosis, and the ESC working group on cardiovascular pharmacotherapy. Eur Heart J, 2021, 42, 4013–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, E.; Ippoliti, A.; Ventoruzzo, G.; De Vivo, G.; Ascoli Marchetti A. ; Pistolese G.R. Popliteal artery aneurysms. Factors associated with thromboembolism and graft failure. Int Angiol, 2004, 23, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Farber, A.; Angle, N.; Avgerinos, E.; Dubois, L.; Eslami, M.; Geraghty, P.; Haurani, M.; Jim, J.; Ketteler, E.; Pulli, R.; et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery clinical practice guidelines on popliteal artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 2022, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuveson V, Löfdahl HE, Hultgren R. Patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm have a high prevalence of popliteal artery aneurysms. Vasc Med, 2016, 21, 369–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropman, R.H.; Schrijver, A.M.; Kelder, J.C.; Moll, F.L.; de Vries, J.P. Clinical outcome of acute leg ischaemia due to thrombosed popliteal artery aneurysm: systematic review of 895 cases. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 2010, 39, 452–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilimparis, N.; Dayama, A.; Ricotta JJ 2nd. Open and endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysms: tabular review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg, 2013, 27, 259–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrijenhoek JE, Mackaay AJ, Moll FL. Small popliteal artery aneurysms: important clinical consequences and contralateral survey in daily vascular surgery practice. Ann Vasc Surg, 2013, 27, 454–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magee, R.; Quigley, F.; McCann, M.; Buttner, P.; Golledge, J. Growth and risk factors for expansion of dilated popliteal arteries. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 2010, 39, 606–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, CJ.; White, T.A. Stenosis of renal artery: an unselected necropsy study. Br Med J, 1964, 2, 1415–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zierler, R.E.; Bergelin, R.O.; Davidson, R.C.; Cantwell-Gab, K.; Polissar, N.L.; Strandness D.E., Jr. A prospective study of disease progression in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Am J Hypertens, 1996, 9, 1055–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.J.; Murphy, T.P.; Cutlip, D.E.; Jamerson, K.; Henrich, W.; Reid, D.M.; Cohen, D.J.; Matsumoto, A.H.; Steffes, M.; Jaff, M.R.; et al. Stenting and medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med, 2014, 370, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, J.A.; Carell, E.S.; Guidera, S.A.; Tripp, HF. Angiographic prevalence and clinical predictors of left subclavian stenosis in patients undergoing diagnostic cardiac catheterization. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv, 2001, 54, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przewlocki, T.; Kablak-Ziembicka, A.; Pieniazek, P.; Musialek, P.; Kadzielski, A.; Zalewski, J.; Kozanecki, A.; Tracz, W. Determinants of immediate and long-term results of subclavian and innominate artery angioplasty. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv, 2006, 67, 519–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboyans, V.; Criqui, M.H.; McDermott, M.M.; Allison, M.A.; Denenberg, J.O.; Shadman, R.; Fronek, A. The vital prognosis of subclavian stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2007, 49, 1540–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, L.A.; Vernon, S.M.; Reynolds, B.; Timm, T.C.; Allen, K. Screening for subclavian artery stenosis in patients who are candidates for coronary bypass surgery. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv, 2002, 56, 162–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Localization prevalence of aortic aneurysms,.

Figure 1.

Localization prevalence of aortic aneurysms,.

Figure 2.

Abdomen's palpation in the search for an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). An abnormal pulsating mass in the mesogastrium, expanding in all the directions, is strongly suspected to be an AAA.

Figure 2.

Abdomen's palpation in the search for an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). An abnormal pulsating mass in the mesogastrium, expanding in all the directions, is strongly suspected to be an AAA.

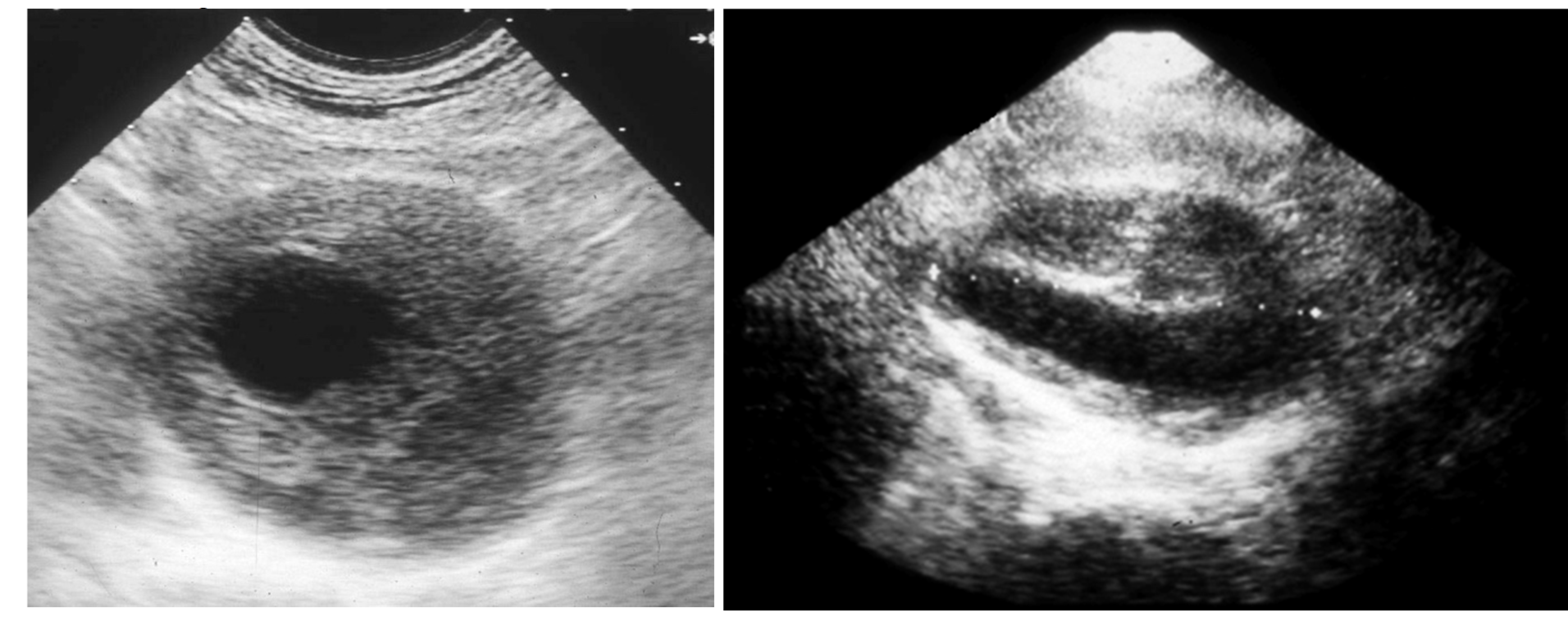

Figure 3.

Duplex scan of the abdominal aorta can easily confirm the clinical suspect of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Short axis (left) and long axis (right) view.

Figure 3.

Duplex scan of the abdominal aorta can easily confirm the clinical suspect of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Short axis (left) and long axis (right) view.

Figure 4.

Duplex scan (long axis view) of the extracranial carotid bifurcation, clearly showing an atherosclerotic plaque causing stenosis of the internal carotid artery.

Figure 4.

Duplex scan (long axis view) of the extracranial carotid bifurcation, clearly showing an atherosclerotic plaque causing stenosis of the internal carotid artery.

Figure 5.

Methods of measurement of severity of internal carotid stenosis (reproduced with permission from Bir S.C; Kelley R.E. Carotid atherosclerotic disease: A systematic review of pathogenesis and management. Brain Circ, 2022, 8, 127-136). NASCET, North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial. ECST, European Carotid Surgery Trial. CCA, common carotid artery. ICA, internal carotid artery. ECA, external carotid artery.

Figure 5.

Methods of measurement of severity of internal carotid stenosis (reproduced with permission from Bir S.C; Kelley R.E. Carotid atherosclerotic disease: A systematic review of pathogenesis and management. Brain Circ, 2022, 8, 127-136). NASCET, North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial. ECST, European Carotid Surgery Trial. CCA, common carotid artery. ICA, internal carotid artery. ECA, external carotid artery.

Figure 6.

Arteriography showing obstruction of the left iliac axis, with an efficient collateral pathway revascularizing the common femoral artery. Depending on his/her age and lifestyle, this patient can eventually be asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic for intermittent claudication. An accurate physical examination (detecting the absence of the left femoral pulse), and the subsequent left ankle-brachial index (founded to be reduced) can easily allow to classify this patient as vasculopathic.

Figure 6.

Arteriography showing obstruction of the left iliac axis, with an efficient collateral pathway revascularizing the common femoral artery. Depending on his/her age and lifestyle, this patient can eventually be asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic for intermittent claudication. An accurate physical examination (detecting the absence of the left femoral pulse), and the subsequent left ankle-brachial index (founded to be reduced) can easily allow to classify this patient as vasculopathic.

Figure 8.

Arteriography showing popliteal artery aneurysm. The physiologic flexion movement of the knee can dislocate part of the mural thrombus, which embolizes and occludes some tibial arteries, giving rise to clinical pictures ranging from an asymptomatic state to intermittent claudication, or chronic limb-threatening ischemia, or acute limb ischemia.

Figure 8.

Arteriography showing popliteal artery aneurysm. The physiologic flexion movement of the knee can dislocate part of the mural thrombus, which embolizes and occludes some tibial arteries, giving rise to clinical pictures ranging from an asymptomatic state to intermittent claudication, or chronic limb-threatening ischemia, or acute limb ischemia.

Figure 9.

Duplex scan of the renal arteries (long axis view). IVC, inferior vena cava.

Figure 9.

Duplex scan of the renal arteries (long axis view). IVC, inferior vena cava.

Figure 10.

Arteriography showing occlusion of the left prevertebral subclavian artery at its orign (on the left): the late angiogram (on the right) demonstrates the blood flow inversion in the left vertebral artery, revascularizing the left subclavian artery after the occlusion, that is subclavian steal syndrome.

Figure 10.

Arteriography showing occlusion of the left prevertebral subclavian artery at its orign (on the left): the late angiogram (on the right) demonstrates the blood flow inversion in the left vertebral artery, revascularizing the left subclavian artery after the occlusion, that is subclavian steal syndrome.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).