Submitted:

28 April 2023

Posted:

29 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Bowel Obstruction

3. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS)

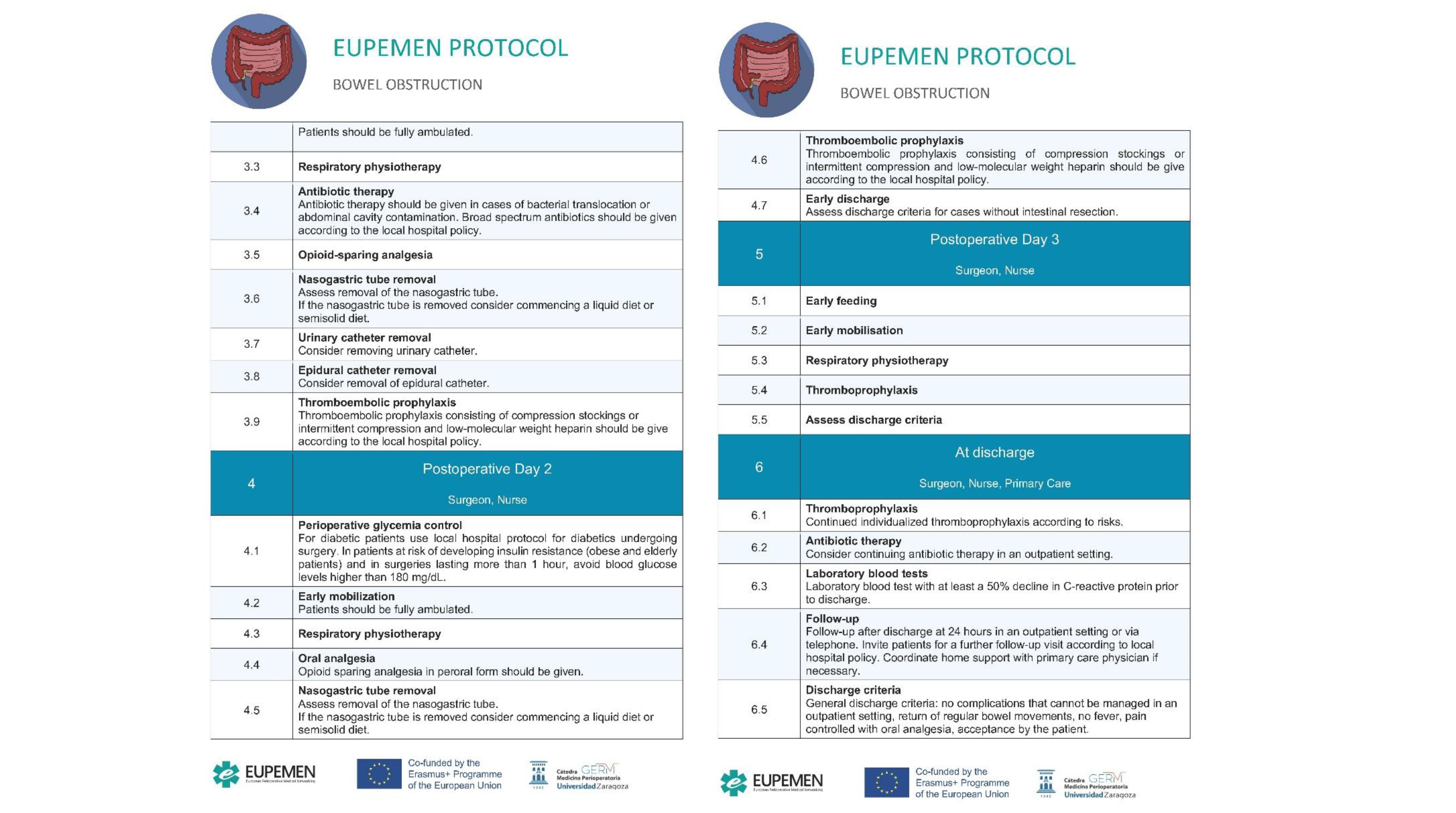

4. The EUPEMEN Bowel Obstruction Protocol (Figure 1)

4.1. Preoperative Phase

4.2. Intraoperative Phase

4.3. Immediate Postoperative Phase

4.4. First Postoperative Day

4.5. Second Postoperative Day

4.6. Third Postoperative Day

4.7. Discharge

5. ERAS in Bowel Obstruction

6. The EUPEMEN project

- Preparation of an educational project (that included a teaching the teachers’ model);

- Implementation in a significant number of European hospitals of the evidence-based protocols in a homogeneous and standardised way;

- Collection of data about hospital stay, morbidity and mortality of European Surgical patients that once analysed through machine learning algorithm, will be of relevant interest to better know the surgical risk of an individual patient, hence to prevent perioperative complications.

-

The preparation of the EUPEMEN Multimodal Rehabilitation manual with the protocols of 6 different modules:

- Bariatric Surgery;

- Oesophageal Surgery;

- Gastric Cancer Surgery;

- Colon Surgery;

- Hepatobiliary Surgery;

- Urgent abdominal surgery, including appendectomy and small bowel obstruction (SBO).

- The development of the EUPEMEN online platform (https://eupemen.eu/): to host the e-learning training course and a collaborative area to improve and to participate in the protocols;

- The training of the trainers to teach the future teachers the different protocol to be able to teach them in the different hospitals;

- The dissemination of the results in 5 Multiplier events, one per partner, to promote the protocols;

- The organization of 4 transnational meetings, one per country;

- The translation into English of the Recovery Intensification for optimal Care in Adult’s surgery - RICA from the Spanish de Recuperación Intensificada en Cirugía del Adulto (RICA).

7. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: A Review. JAMA Surg 2017, 152, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott MJ, Baldini G, Fearon KCH, Feldheiser A, Feldman LS, Gan TJ, Ljungqvist O, Lobo DN, Rockall TA, Schricker T, Carli F. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) for gastrointestinal surgery, part 1: pathophysiological considerations. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2015, 59, 1212–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catena F, De Simone B, Coccolini F, Di Saverio S, Sartelli M, Ansaloni L. Bowel obstruction: a narrative review for all physicians. World J Emerg Surg. 2019, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore RM, Silvers RI, Thakrar KH, Wenzke DR, Mehta UK, Newmark GM, Berlin JW. Bowel Obstruction. Radiol Clin North Am. 2015, 53, 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson WR, Hawkins AT. Large Bowel Obstruction. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2021, 34, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long B, Robertson J, Koyfman A. Emergency Medicine Evaluation and Management of Small Bowel Obstruction: Evidence-Based Recommendations. J Emerg Med 2019, 56, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detz DJ, Podrat JL, Muniz Castro JC, Lee YK, Zheng F, Purnell S, Pei KY. Small bowel obstruction. Curr Probl Surg 2021, 58, 100893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Agostino R, Ali NS, Leshchinskiy S, Cherukuri AR, Tam JK. Small bowel obstruction and the gastrografin challenge. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2018, 43, 2945–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aka AA, Wright JP, DeBeche-Adams T. Small Bowel Obstruction. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2021, 34, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower KL, Lollar DI, Williams SL, Adkins FC, Luyimbazi DT, Bower CE. Small Bowel Obstruction. Surg Clin North Am. 2018, 98, 945–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond M, Lee J, LeBedis CA. Small Bowel Obstruction and Ischemia. Radiol Clin North Am. 2019, 57, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Schwenk W, Demartines N, Roulin D, Francis N, McNaught CE, MacFie J, Liberman AS, Soop M, Hill A, Kennedy RH, Lobo DN, Fearon K, Ljungqvist O; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colonic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Clin Nutr. 2012, 31, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nygren J, Thacker J, Carli F, Fearon KC, Norderval S, Lobo DN, Ljungqvist O, Soop M, Ramirez J; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective rectal/pelvic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Clin Nutr. 2012, 31, 801–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, Nygren J, Demartines N, Francis N, Rockall TA, Young-Fadok TM, Hill AG, Soop M, de Boer HD, Urman RD, Chang GJ, Fichera A, Kessler H, Grass F, Whang EE, Fawcett WJ, Carli F, Lobo DN, Rollins KE, Balfour A, Baldini G, Riedel B, Ljungqvist O. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Elective Colorectal Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society Recommendations: 2018. World J Surg. 2019, 43, 659–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisch SP, Jago CA, Kalogera E, Ganshorn H, Meyer LA, Ramirez PT, Dowdy SC, Nelson G. Outcomes of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) in gynecologic oncology - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2021, 161, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noba L, Rodgers S, Chandler C, Balfour A, Hariharan D, Yip VS. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Reduces Hospital Costs and Improve Clinical Outcomes in Liver Surgery: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020, 24, 918–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee Y, Yu J, Doumouras AG, Li J, Hong D. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) versus standard recovery for elective gastric cancer surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Oncol. 2020, 32, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye Z, Chen J, Shen T, Yang H, Qin J, Zheng F, Rao Y. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) might be a standard care in radical prostatectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2020, 9, 746–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noba L, Rodgers S, Doi L, Chandler C, Hariharan D, Yip V. Costs and clinical benefits of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) in pancreaticoduodenectomy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Grupo de trabajo. Vía Clínica de Recuperación Intensificada en Cirugía Abdominal (RICA). Vía clínica de recupe- ración intensificada en cirugía abdominal (RICA) Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Instituto Aragonés de Ciencias de la Salud. 2014. Available online: http://portal.guiasalud.es/contenidos/iframes/documentos/opbe/2015-07/ViaClinica-RICA.pdf.

- Ramirez, Jose & Ruiz-López, Pedro & Gurumeta, Alfredo & Arroyo-Sebastian, Antonio & Bruna-Esteban, M. & Sanchez, Alberto & Calvo-Vecino, José & García-Erce, José & García-Fernández, Alfredo & Toro, Manuel & Grima, Francisco & Ramírez, Ana & Loinaz, Carmelo & Raldúa, Natividad & Calabuig, Juan & Muñoz, Manuel & Quintas, Carmen & Bretón, Julia & Ojeda Thies, Cristina & Ríos, Jorge. (2021). CLINICAL PATHWAY Recovery Intensification for optimal Care in Adult's surgery.

- Dalton A, Zafirova Z. Preoperative Management of the Geriatric Patient: Frailty and Cognitive Impairment Assessment. Anesthesiol Clin. 2018, 36, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam S, Aalberg J, Soriano RP, Divino CM. New 5-Factor Modified Frailty Index Using American College of Surgeons NSQIP Data. J Am Coll Surg. 2018, 226, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Zou Y, Zhao J, Schneider DB, Yang Y, Ma Y et al. The Impact of Frailty on Outcomes of Elderly Patients After Major Vascular Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018, 56, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellví Valls J, Borrell Brau N, Bernat MJ, Iglesias P, Reig L, Pascual L et al. Colorectal carcinoma in the frail surgical patient. Implementation of a Work Area focused on the Com- plex Surgical Patient improves postoperative outcome. Cir Esp. 2018, 96, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Hao Q, Zhou J, Dong B. The impact of frailty and sarcopenia on postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing gastrectomy surgery: a systematic review and me- ta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 188. [Google Scholar]

- Torossian A, Bräuer A, Höcker J, Bein B, Wulf H, HornEP. Preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Clinical Practice Guideline. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015, 112, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Warttig S, Alderson P, Campbell G,Smith AF. Interventionsfor treating inadvertent postoperative hypothermia. Interventionsfor treating inadvertent postoperative hypothermia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014, CD009892. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper VD, Chard R, Clifford T, Fetzer S, Fossum S, Godden B, et al. ASPAN’s evidence- based clinical practice guideline for the promotion of perioperative normothermia: second edition. J Perianesth Nurs. 2010, 25, 346–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar Z, Hesler BD, Fiffick AN, Mascha EJ, Sessler DI, Kurz A, et al. A randomized trial of prewarming on patient satisfaction and thermal comfort in outpatient surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2016, 33, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protocolo de Trabajo del IQZ 2017. Disponible en (última consulta 01-06-2020): https://infeccionquirurgicazero.es/es/documentos-y-materiales/protocolos-de-trabajo.

- Pontes JPJ, Mendes FF, Vasconcelos MM, Batista NR. [Evaluation and perioperative management of patients with diabetes mellitus. A challenge for the anesthesiologist]. Rev Bras Anestesiol 2018, 68, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Akiboye F, Rayman G. Management of Hyperglycemia and Diabetes in Orthopedic Surgery. Curr Diab Rep 2017, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhatariya K, Levy N, Hall GM. The impact of glycaemic variability on the surgical patient. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2016, 29, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker P, Creasey PE, Dhatariya K, Levy N, Lipp A, Nathanson MH et al. Peri-operative management of the surgical patient with diabetes 2015: Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Anaesthesia 2015, 70, 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegranzi B, Zayed B, Bischoff P, Kubilay NZ, de Jonge S, de Vries F, et al. New WHO re- commendations on intraoperative and postoperative measures for surgical site infection prevention: an evidence-based global perspective. Lancet Infect Dis. diciembre de 2016, 16, e288–303. [Google Scholar]

- Allegranzi B, Bischoff P, de Jonge S, Kubilay NZ, Zayed B, Gomes SM, et al. New WHO re- commendations on preoperative measures for surgical site infection prevention: an evidence-based global perspective. Lancet Infect Dis. diciembre de 2016, 16, e276–e287. [Google Scholar]

- Badia JM, Casey AL, Petrosillo N, Hudson PM, Mitchell SA, Crosby C. Impact of surgical site infection on healthcare costs and patient outcomes: a systematic review in six European countries. J Hosp Infect. mayo de 2017, 96, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proyecto Infección Quirúrgica Zero del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Sociedad Española de Medicina Preventiva, Salud Pública e Higiene. 2016.

- Nelson G, Bakkum-Gamez J, Kalogera E, Glaser G, Altman A, Meyer LA et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in gynecologic/oncology: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations-2019 update. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019, 29, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, Nygen J, Demartines N Francis N, et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Elective Colorectal Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society Recommendations: 2018. World J Surg. 2019, 43, 659–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkietkachorn A, Wongkietkachorn N, Rhunsiri P. Preoperative needs-based education to reduce anxiety, increase satisfaction, and decrease time spent in day surgery: a randomized controlled trial. World J Surg. 2018, 42, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Programa de Cirugía Segura del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servi- cios Sociales e Igualdad. 2016.

- De Jager E, McKenna C, Bartlett L3, Gunnarsson R, Ho YH. postoperative Adverse Events Inconsistently Improved by The World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist: A Systematic Literature Review of 25 Studies. World J Surg. 2016, 40, 1842–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott TEF, Ahmad T, Phull MK, Fowler AJ, Hewson R, Biccard BM, Chew MS, Gillies M, Pearse RM; International Surgical Outcomes Study (ISOS)group. The surgical safety chec- klist and patient outcomes after surgery: prospective observational cohort study, systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2018, 120, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biccard BM, Rodseth R, Cronje L, Agaba P, Chikumba E, Du Toit L, Farina Z, Fischer S, Go- palan PD, Govender K, Kanjee J, Kingwill A, Madzimbamuto F, Mashava D, Mrara B, Mudely M, Ninise E, Swanevelder J, Wabule A.A meta-analysis of the efficacy of preoperative surgical safety checklists to improve perioperative.

- Lam T, Nagappa M, Wong J, Singh M, Wong D, Chung F. Continuous Pulse Oximetry and Capnography Monitoring for Postoperative Respiratory Depression and Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2017, 125, 2019–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, Mendonca C, Bhagrath R, Patel A et al. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth 2015, 115, 827–8481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urits I, Jones MR, Orhurhu V, Sikorsky A, Seifert D, Flores C, et al. A Comprehensive Update of Current Anesthesia Perspectives on Therapeutic Hypothermia. Adv Ther 2019, 36, 2223–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo Vecino JM, Casans Francés R, Ripollés Melchor J, Marín Zaldívar C, Gómez Ríos MA, Pérez Ferrer A, et al. No Intencionada de la SEDAR. Clinical practice guideline. Unintentional perioperative hypothermia. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2018, 65, 564–588. [Google Scholar]

- Madden LK, Hill M, May TL, Human T, Guanci MM, Jacobi J, Moreda MV, et al. The Implementation of Targeted Temperature Management: An Evidence-Based Guideline from the Neurocritical Care Society. Neurocrit Care. 2017, 27, 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaryus R, Miller TE, Gan TJ. Current concepts of fluid management in enhanced recovery pathways. Br J Anaesth 2018, 120, 376–383. [CrossRef]

- Joosten A, Delaporte A, Ickx B, Touihri K, Stany I, Barvais L, et al. Crystalloid versus colloid for intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy using a closed-loop system: A randomized, double-blinded, controlled trial in major abdominal surgery. Anesthesiology 2018, 128, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor PM, Magoon R, Rawal RS, Mehta Y, Taneja S, Ravi R, et al. Goal-directed therapy improves the outcome of high-risk cardiac patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass. Ann Card Anaesth 2017, 20, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchin MR, Ceria CM, Giannone S, Ghisi D, Stagni G, Greggi T, et al. Goal-direted fluid therapy based on stroke volume variation in patients undergoing major spine surgery in the prone position: A cohort study. Spine 2016, 41, E1131–E1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salicath JH, Yeoh ECY, Bennett MH. Epidural analgesia versus patient-controlled intravenous analgesia for pain following intra-abdominal surgery in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, 8, CD010434. [Google Scholar]

- Guay J, Nishimori M, Kopp S. Epidural local anaesthetics versus opioid-based analgesic regimens for postoperative gastrointestinal paralysis, vomiting and pain after abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, 7, CD001893. [Google Scholar]

- Apfel CC, Läärä E, Koivuranta M, Greim CA, Roewer N. A simplified risk scorefor predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology 1999, 91, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apfel CC, Philip BK, Cakmakkaya OS, Shilling A,ShiY-Y, LeslieJB, et al. Whoi s at risk for postdischarge nausea and vomiting after ambulatory surgery? Anesthesiology 2012, 117, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apfel CC, Heidrich FM, Jukar-Rao S, Jalota L, Hornuss C, Whelan RP, et al. Evidence-ba- sed analysis of risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth 2012, 109, 742–753.

- Nelson G, Bakkum-Gamez J, Kalogera E, Glaser G, Altman A, Meyer LA, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in gynecologic/oncology: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations-2019 update. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019, 29, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, Nygren J, Demartines N, Francis N, et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Elective Colorectal Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society Recommendations: 2018. World J Surg. 2019, 43, 659–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denost Q, Rouanet P, Faucheron JL, Panis Y, Meunier B, Cotte E, et al. French Research Group of Rectal Cancer Surgery (GRECCAR). To Drain or Not to Drain Infraperitoneal Anas- tomosis After Rectal Excision for Cancer: The GRECCAR 5 Randomized Trial. Ann Surg. 2017, 265, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael JC, Keller DS, Baldini G, Bordeianou L, Weiss E, Lee L et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Enhanced Recovery After Colon and Rectal Surgery From the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017, 60, 761–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang HY, Zhao CL, Xie J, Ye YW, Sun JF, Ding ZH, et al. To drain or not to drain in colorectal anastomosis: a meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016, 31, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musser JE, Assel M, Guglielmetti GB, Pathak P, Silberstein JL, Sjoberg DD, et al. Impact of routine use of surgical drains on incidence of complications with robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. J Endourol. 2014, 28, 1333–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel DN, Felder SI, Luu M, Daskivich TJ, K NZ, Fleshner P. Early Urinary Catheter Removal Following Pelvic Colorectal Surgery: A Prospective, Randomized, Noninferiority Trial. Dis Colon Rectum 2018, 61, 1180–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami M, Lundberg P, Passot G, Glehen O, Cotte E. Laparoscopic Colonic Resection Without Urinary Drainage: Is It “Feasible”? J Gastrointest Surg 2016, 20, 1388–1392.

- Zhang P, Hu WL, Cheng B, Cheng L, Xiong XK, Zeng YJ. A systematic review and meta- analysis comparing immediate and delayed catheter removal following uncomplicated hysterectomy. Int Urogynecol J 2015, 26, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotagal M, Symons RG, Hirsch IB, Umpierrez GE, Farrokhi ET, Flum DR, SCOAP-Ceertain Collaborative. Perioperative hyperglycemia and risk of adverse events among patients with and without diabetes. Ann Surg 2015, 261, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, Higashiguchi T, Hübner M, Klek S, et al. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin Nutr 2017, 36, 623–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. 15. Diabetes Care in the Hospital: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019, 42 (Suppl 1), S173–S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torossian, A. Thermal management during anaesthesia and thermoregulation standards for the prevention of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2008, 22, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warttig S, Alderson P, Campbell G, Smith AF. Interventions for treating inadvertent postoperative hypothermia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014, CD009892. [Google Scholar]

- Madrid E, Urrútia G, Roqué i Figuls M, Pardo-Hernandez H, Campos JM et al. Active body surface warming systems for preventing complications caused by inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016, 4, CD009016. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell G, Alderson P, Smith AF, Warttig S. Warming of intravenous andirrigationfluids for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, CD009891. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Vecino JM, Casans Francés R, Ripollés Melchor J, Marín Zaldívar C, Gómez Ríos MA, Pérez Ferrer A, et al. Clinical practice guideline. Unintentional perioperative hypothermia. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2018, 65, 564–588. [Google Scholar]

- Felder S, Rasmussen MS, King R, Sklow B, Kwaan M, Madoff R, et al. Prolonged thrombo-prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin for abdominal or pelvic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019, 3, CD004318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas D, Roldán I, Ferrandis R, Marín F, Roldán V, Tello-Montoliu A, et al. Perioperative and Periprocedural Management of Antithrombotic Therapy: Consensus Document of SEC, SEDAR, SEACV, SECTCV, AEC, SECPRE, SEPD, SEGO, SEHH, SETH, SEMERGEN, SEMFYC, SEMG, SEMICYUC, SEMI, SEMES, SEPAR, SENEC, SEO, SEPA, SERVEI, SECOT and AEU. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2018, 71, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, Curley C, Dahl OE, Schulman S, et al: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012, 141 (Suppl. 2), e278S–e325S.

- Anderson DR, Morgano GP, Bennett C, Dentali F, Francis CW, Garcia DA, et al American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 3898–3944. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshari A, Fenger-Eriksen C, Monreal M, Verhamme P; ESA VTE Guidelines Task Force. European guidelines on perioperative venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: Mechanical prophylaxis. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018, 35, 112–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulier JP, Dillemans B. Anaesthetic Factors Affecting Outcome After Bariatric Surgery, a Retrospective Levelled Regression Analysis. OBES SURG. 2019, 29, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frauenknecht J, Kirkham KR, Jacot-Guillarmod A, Albrecht E. Analgesic impact of intra- operative opioids vs. opioid-free anaesthesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2019, 74, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulier JP,Wouters R,Dillemans B,DeckockMl. ARandomizedControlled,Double-Blind Trial Evaluating the Effect of Opioid-Free Versus Opioid General Anaesthesia on Postoperative Pain and Discomfort Measured by the QoR-40. J Clin Anesth Pain Med. 2018, 2, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mulier JP, Dillemans B. Deep Neuromuscular Blockade versusRemifentanil or Sevoflurane to Augment Measurable Laparoscopic Workspaceduring Bariatric Surgery Analysed bya Rando- misedControlledTrial. Journal of Clinical Anesthesiaand Pain Medicine 2018, 7, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Castelino T, Fiore JF Jr, Niculiseanu P et al The effect of early mobilization protocols on postoperative outcomes following abdominal and thoracic surgery: a systematic review. Surgery. 2016, 159, 991–1003. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida EPM, de Almeida JP, Landoni G, et al. Early mobilization programme improves functional capacity after major abdominal cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial [with consumer summary]. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2017, 119, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller SJ, Anstey M, Blobner M etal. Early, goal-directed mobilization in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2016, 388, 1377–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiore JF Jr, Castelino T, Pecorelli Net al. Ensuring early mobilization within an enhanced recovery program for colorectal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2017, 266, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Elective Colorectal Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS_) Society Recommendations: 2018. World J Surg 2019, 43, 659–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolk S, Linke S, Bogner A. Use of Activity Tracking in Major Visceral Surgery-the Enhanced Perioperative Mobilization Trial: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gastrointest Surg 2019, 23, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsura M, Kuriyama A, Takeshima T, Fukuhara S, Furukawa TA. Preoperative inspiratory muscle training for postoperative pulmonary complications in adults undergoing cardiac and major abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, 5, CD010356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalil-Filho FA, Campos ACL, Tambara EM, Tomé BKA, Treml CJ, Kuretzki CH, et al. Phy- siotherapeutic approaches and the effects on inspiratory muscle force in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the pre-operative preparation for abdominal sur- gical procedures. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2019, 32, e1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall F, Oliveira J, Peleteiro B, Pinho P, Bastos PT. Inspiratory muscle training is effective to reduce postoperative pulmonary complications and length of hospital stay: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2018, 40, 864–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaparthi GK, Augustine AJ, Anand R, Mahale A. Comparison of Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercise, Volume and Flow Incentive Spirometry, on Diaphragm Excursion and Pulmonary Function in Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Minim Invasive Surg 2016, 2016, 1967532. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson E, Farahnak P, Franzén E, Nygren-Bonnier M, Dronkers J, van Meeteren N, et al. Feasibility of preoperative supervised home-based exercise in older adults undergoing colorectal cancer surgery-A randomized controlled design. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0219158. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez V, Beloeil H, Marret E, Fletcher D, Ravaud P, Trinquart L. Non-opioid analgesics in adults after major surgery: systematic review with network meta-analysis of randomized trials. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017, 118, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salicath JH, Yeoh ECY, Bennett MH. Epidural analgesia versus patient-controlled intrave-nous analgesia for pain following intra-abdominal surgery in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018, 8, CD010434. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen H, Wetterslev J, Møiniche S, Dahl JB. Epidural local anaesthetics versus opioid-based analgesic regimens on postoperative gastrointestinal paralysis, PONV and pain after abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000, CD001893.

- McDaid C, Maund E, Rice S, Wright K, Jenkins B, Woolacott N. Paracetamol and selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the reduction of morphine-related side effects after major surgery: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2010,1–153, iii–iv.

- MacFater WS, Rahiri J-L, Lauti M, Su’a B, Hill AG. Intravenous lignocaine in colorectal sur- gery: a systematic review. ANZ J Surg. 2017, 87, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weibel S, Jokinen J, Pace NL, Schnabel A, Hollmann MW, Hahnenkamp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous lidocaine for postoperative analgesia and recovery after surgery: a systematic review with trial sequential analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2016, 116, 770–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weibel S, Jelting Y, Pace NL, Helf A, Eberhart LH, Hahnenkamp K, et al. Continuous intra- venous perioperative lidocaine infusion for postoperative pain and recovery in adults. Co- chrane Database Syst Rev. 2018, 6, CD009642. [Google Scholar]

- Baeriswyl M, Zeiter F, Piubellini D, Kirkham KR, Albrecht E. The analgesic efficacy of trans- verse abdominis plane block versus epidural analgesia: a systematic review with meta- analysis. Medicine. 2018, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Willcutts KF, Chung MC, Erenberg CL, Finn KL, Schirmer BD, Byham-Gray LD. Early oral feeding as compared with traditional timing of oral feeding after upper gastrointestinal surgery. Ann Surg 2016, 264, 54e63. [Google Scholar]

- Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, Higashiguchi T, Hübner M, Klek S, et al. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin Nutr 2017, 36, 623–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma J, Kumar N, Huda F, Payal YS. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol in Emergency Laparotomy: A Randomized Control Study. Surg J (NY) 2021, 7, e92–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shida D, Tagawa K, Inada K, Nasu K, Seyama Y, Maeshiro T, Miyamoto S, Inoue S, Umekita N. Modified enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols for patients with obstructive colorectal cancer. BMC Surg 2017, 17, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Miao X, Tao L, Huang L, Li J, Pan S. Application of Laparoscopy Combined with Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) in Acute Intestinal Obstruction and Analysis of Prognostic Factors: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Biomed Res Int. 2022, 2022, 5771526. [Google Scholar]

- Saurabh K, Sureshkumar S, Mohsina S, Mahalakshmy T, Kundra P, Kate V. Adapted ERAS Pathway Versus Standard Care in Patients Undergoing Emergency Small Bowel Surgery: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020, 24, 2077–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).