Submitted:

28 April 2023

Posted:

28 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. A Classical SIR Epidemic Pattern with Demography

- For the disease-free equilibrium , the Jacobi matrix is with eigenvalues , . Then is unstable (saddle point) if and only if , and is locally asymptotically stable (stable node) if and only if . If , then is a non hyperbolic equilibrium point and we cannot apply Hartman-Grobman Theorem for the local behavior study.

-

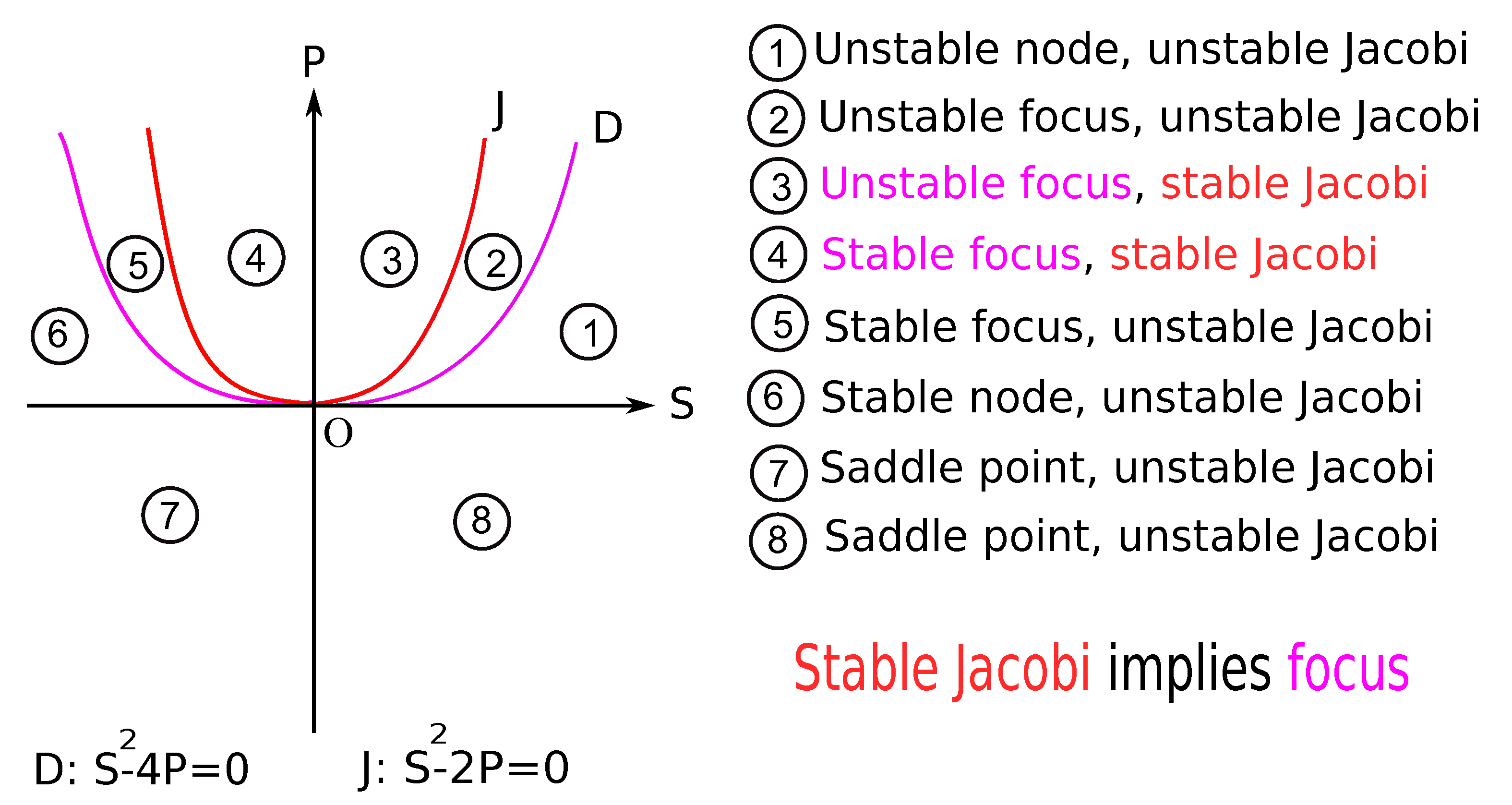

For the endemic equilibrium , the Jacobianwith characteristic polynomial and eigenvalues. Since , we have that and , that means that, if exists, the endemic equilibrium is always locally asymptotically stable (stable node or stable focus). More precisely, is a stable node if and only if , and is a stable focus if and only if .

- If , then there exists only the disease-free equilibrium point, which is an attractive equilibrium (stable node), i.e. any trajectory of the dynamical system (3) starting near to converges at this equilibrium when time tends to infinity, and the disease disappears from the population.

- If , then there exists two equilibrium points: the disease-free equilibrium and the endemic equilibrium. The disease-free equilibrium is not attractive (unstable, a saddle point), in the sense that there exists trajectories of the system (3) that start very close to , but it tend to go away. Instead, the endemic equilibrium is attractive (stable node or stable focus), that means any orbit of the system (3) starting near to converge to as time goes to infinity. So, in this case, the disease remains endemic in the population.

3. SODE Formulation of the Classical SIR Pattern with Demography

4. Jacobi Stability Analysis of the Classical SIR System with Demography

4.1. Dynamics of the Deviation Vector for the Classical SIR System with Demography

5. A Simple SIR Epidemic Pattern with Demography and Vaccination

6. A Modified SIR Epidemic Pattern with Demography

7. SODE Formulation of the Modified SIR Pattern with Demography

8. Jacobi Stability Analysis of the Modified SIR System with Demography

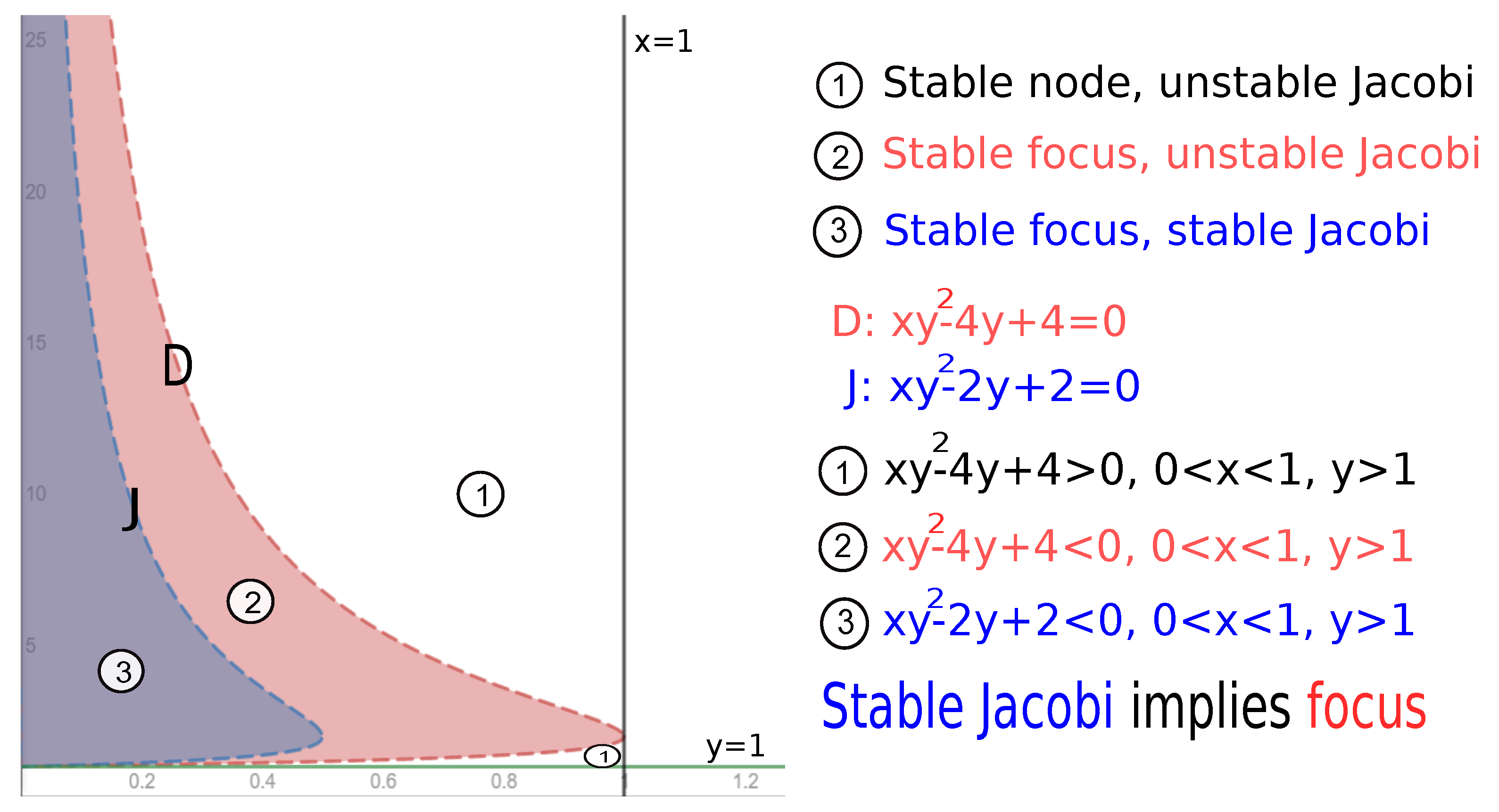

8.1. Jacobi Stability Near to Endemic Equilibrium for

8.2. Jacobi Stability Near to Endemic Equilibrium for

8.3. Jacobi Stability Near to Endemic Equilibrium for

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Kosambi–Cartan–Chern (KCC) Geometric Theory and Jacobi Stability

Appendix A.1. Comparison between Lyapunov Stability and Jacobi Stability for Two-Dimensional Systems

References

- Martcheva, M. Texts in Applied Mathematics. In An Introduction to Mathematical Epidemiology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 61, pp. 33–66. [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, F.; Castillo-Chavez, C. Mathematical Models in Population Biology and Epidemiology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, H.I. Deterministic Mathematical Models in Population Biology; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Trejos, D.Y.; Valverde, J.C.; Venturino, E. Dynamics of infectious diseases: A review of the main biological aspects and their mathematical translation. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2021, 7, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacaër, N. Mathématiques et Épidémies; Cassini: Paris, France, 2021; 320p. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Bacaër, N.; Halanay, A.; Avram, F.; Munteanu, F. O Scurtă Istorie a Modelării Matematice a Dinamicii Populaţiilor; Cassini: Paris, France, 2022; 167p. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Munteanu, F. A Comparative Study of Three Mathematical Models for the Interaction between the Human Immune System and a Virus. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, F. A 4-Dimensional Mathematical Model for Interaction between the Human Immune System and a Virus. Preprints.org 2022, 2022070282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, F. A Local Analysis of a Mathematical Pattern for Interaction between the Human Immune System and a Pathogenic Agent. Int J. Biomath. 2023. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, P.L.; Ingarden, R.S.; Matsumoto, M. The Theories of Sprays and Finsler Spaces with Application in Physics and Biology; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA; London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, P.L. Equivalence Problem for Systems of Second Order Ordinary Differential Equations, Encyclopedia of Mathematics; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, P.L. Handbook of Finsler Geometry; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, P.L.; Bucătaru, I. New results about the geometric invariants in KCC-theory. An. St. Al.I. Cuza Univ. Iaşi Mat. N.S. 2001, 47, 405–420. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, D.; Chern, S.S.; Shen, Z. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. In An Introduction to Riemann–Finsler Geometry; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 200. [Google Scholar]

- Udrişte, C.; Nicola, R. Jacobi stability for geometric dynamics. J. Dyn. Sys. Geom. Theor. 2007, 5, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabău, S.V. Systems biology and deviation curvature tensor. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2005, 6, 563–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabău, S.V. Some remarks on Jacobi stability. Nonlinear Anal. 2005, 63, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohmer, C.G.; Harko, T.; Sabau, S.V. Jacobi stability analysis of dynamical systems—Applications in gravitation and cosmology. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2012, 16, 1145–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harko, T.; Ho, C.Y.; Leung, C.S.; Yip, S. Jacobi stability analysis of Lorenz system. Int. J. Geom. Meth. Mod. Phys. 2015, 12, 1550081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harko, T.; Pantaragphong, P.; Sabau, S.V. Kosambi–Cartan–Chern (KCC) theory for higher order dynamical systems. Int. J. Geom. Meth. Mod. Phys. 2016, 13, 1650014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K.; Yadav, C.K. Jacobi stability of modified Chua circuit system. Int. J. Geom. Meth. Mod. Phys. 2017, 14, 1750089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K.; Yadav, C.K. Rabinovich-Fabrikant system in view point of KCC theory in Finsler geometry. J. Interdisc. Math. 2019, 22, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, F.; Ionescu, A. Analyzing the Nonlinear Dynamics of a Cubic Modified Chua’s Circuit System. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Applied and Theoretical Electricity (ICATE), Craiova, Romania, 27–29 May 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Munteanu, F. Analyzing the Jacobi Stability of Lü’s Circuit System. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, F. A Study of the Jacobi Stability of the Rosenzweig–MacArthur Predator–Prey System through the KCC Geometric Theory. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, F.; Grin, A.; Musafirov, E.; Pranevich, A.; Şterbeţi, C. About the Jacobi Stability of a Generalized Hopf–Langford System through the Kosambi–Cartan–Chern Geometric Theory. Symmetry 2023, 15, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosambi, D.D. Parallelism and path-space. Math. Z. 1933, 37, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartan, E. Observations sur le memoire precedent. Math. Z. 1933, 37, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chern, S.S. Sur la geometrie dn systeme d’equations differentielles du second ordre. Bull. Sci. Math. 1939, 63, 206–249. [Google Scholar]

- Miron, R.; Hrimiuc, D.; Shimada, H.; Sabău, S.V. The Geometry of Hamilton and Lagrange Spaces; Book Series Fundamental Theories of Physics (FTPH 118); Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miron, R.; Bucătaru, I. Finsler–Lagrange Geometry. Applications to Dynamical Systems; Romanian Academy: Bucharest, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Munteanu, F. On the semispray of nonlinear connections in rheonomic Lagrange geometry. In Finsler and Lagrange Geometries, Proceedings of the Finsler–Lagrange Geometries Conference, Iaşi, Romania, 26–31 August 2002; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, K.; Yajima, T. Lotka–Volterra system and KCC theory: Differential geometric structure of competitions and predations. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2013, 14, 1845–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolghasem, H. Stability of circular orbits in Schwarzschild spacetime. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2013, 12, 131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Abolghasem, H. Jacobi stability of Hamiltonian systems. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2013, 87, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolebaje, O.; Popoola, O. Jacobi stability analysis of predator-prey models with holling-type II and III functional responses. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings of the International Conference on Mathematical Sciences and Technology 2018, Penang, Malaysia, 10–12 December 2018; Volume 2184, p. 060001. [Google Scholar]

- Porwal, P.; Shrivastava, P.; Tiwari, S.K. Study of simple SIR epidemic model. Adv. Appl. Sci. Res. 2015, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Turkyilmazoglu, M. An extended epidemic model with vaccination: Weak-immune SIRVI. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2022, 598, 127429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucur, L. The behaviour of an epidemiological model. In Proceedings of the ITM Web of International Conference on Applied Mathematics and Numerical Methods—Fourth Edition (ICAMNM 2022), Craiova, Romania, 29 June–2 July 2022; Volume 49, p. 01002. [Google Scholar]

- Munteanu, F. A study of a three-dimensional competitive Lotka–Volterra system. In Proceedings of the ITM Web of Conferences of the International Conference on Applied Mathematics and Numerical Methods—Third Edition (ICAMNM 2020), Craiova, Romania, 29–31 October 2020; Volume 34, p. 03010. [Google Scholar]

| Case | Conditions | Equilibrium points type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | , | saddle point, stable node |

| 2 | , | saddle point, stable focus |

| 3 | non hyperbolic | |

| 4 | stable node, |

| Case | Conditions | Equilibrium points type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | saddle point, , attractor or repeller | |

| 2 | , | non hyperbolic, attractor or repeller |

| 3 | , | non hyperbolic |

| 4 | , | non hyperbolic, |

| 5 | stable node, saddle point, attractor or repeller | |

| 6 | stable node, non hyperbolic, | |

| 7 | stable node, , don’t exists |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).