Submitted:

25 April 2023

Posted:

26 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature review

2.1. Achieving project success in large construction and infrastructure projects

- Unique physical product

- Long planning phase and project duration

- Material costs exceed labor costs

- Stationary place of execution of the project

- Detailed specifications with many standards, norms, and regulations to meet

- Plan-driven approach to design and implementation

2.2. Engagement of the project stakeholders as critical success factor for infrastructure projects

- Inform - provide stakeholders with balanced and objective information that will help them understand problems, alternatives and/or solutions.

- Consult - get feedback from stakeholders about the analysis, alternatives and/or decisions made.

- Involve - work directly with stakeholders throughout the process to ensure that their concerns and aspirations are consistently understood and addressed.

- Collaborate - be in partnership with stakeholders in every aspect of the decision.

- Empower - place the final decision-making in the hands of stakeholders.

2.3. Complex context of Infrastructure projects – enabling engagement through specific project governance and management mechanisms

- phase gates with documentation requirements and comprehensive audits, especially very early consultations - initial gates (UK, NL) and use of external consultants from the private sector as external auditors (UK, NO)

- focus on needs and a more robust, clearer, and broader basis of planning in the early stages ("front-end planning")

- extensive early involvement of stakeholders (NL)

- active risk management, independent review of cost estimates and use of contingency reserves in budgets to protect against uncertainty and avoid cost overruns (UK, NO)

- professionalization of public project organizations in the management of projects and programs and public procurement by strengthening requirements, systems, training and issuing guidelines.

2.3.1. Croatian administrative and organizational context for infrastructure project and engagement of project stakeholders

- Act on the establishment of an institutional framework for the implementation of European structural and investment funds in the Republic of Croatia in the financial period 2014-2020 [78]

- Regulations that prescribe the jurisdiction of individual bodies for each European structural instrument (ESI), for example the Regulation on bodies in the management and control systems of the use of the European Social Fund, the European Fund for Regional Development and the Cohesion Fund, in connection with the objective » Investment for growth and jobs" [79].

- …establish its own system of project implementation (execution of activities) and update and, if necessary, detail the project implementation plan foreseen in the project proposal;

- updating and, if necessary, detailing the time plan (schedule) foreseen in the project proposal and updating responsibilities for execution of project activities... ;

-

…areas of project implementation monitoring include:

- ○

- Systematic updating and monitoring of the project implementation plan

- ○

- Project team management

- ○

- Management of outputs and results

- ○

- Project procurement management

- ○

- Human resource management

- ○

- Risk management

- ○

- Management of information dissemination and visibility

3. Methodology

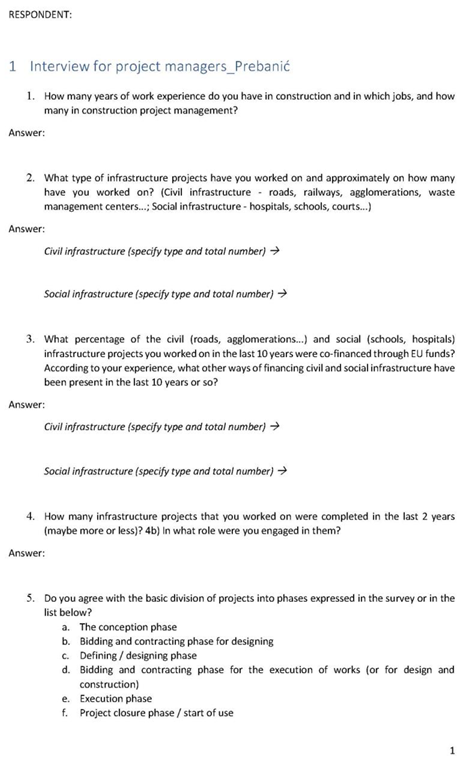

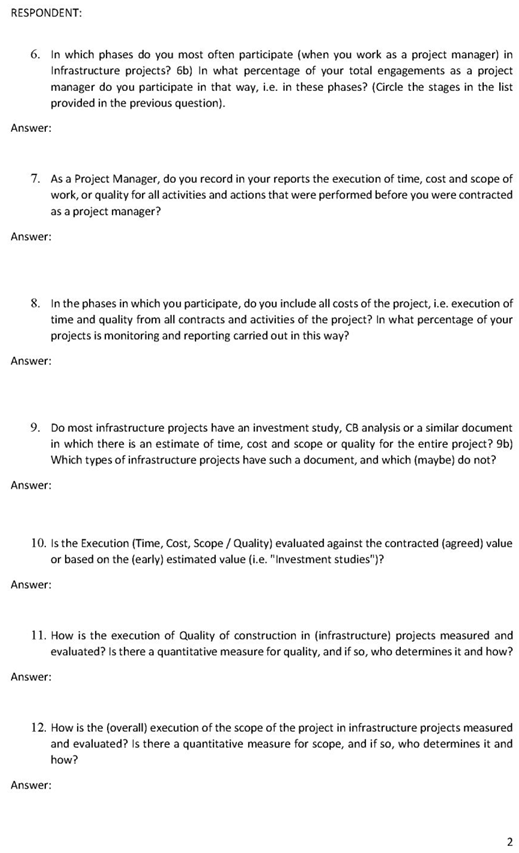

- 3 respondents - construction project manager (as a separate contracting party according to the Act on Works and Activities in Spatial Planning and Construction)

- 1 respondent - public client (planning, monitoring and control; project sponsor - as part of the organization of public clients)

- 1 respondent - public client consultant (consultation and preparation of initial documents and studies for programs and projects e.g. feasibility studies; consulting services and project management)

- 1 respondent - contractor

- 1 respondent - designer

- 1 respondent - professional supervisor/superintendent/FIDIC engineer

4. Results - Multifaceted nature of stakeholder engagement and project success in infrastructure projects

“…time and cost are monitored based on the (secondary) contract. It is important to distinguish between the so-called primary contract, i.e., the grant award contract (with Managing body of ESI fund) which is based on feasibility study and grant application, and all other contracts for construction project services (e.g., contractor, supervising engineer), which are called secondary contracts. Monitoring and control can be done against both type of contracts if the construction project manager role was procured in that way...”.(Project Manager 1)

“...durability, use value, defects in the warranty period (Designer)"; "descriptive through a list of specifications in the tender (Public client consultant)" ; "...the client's requirements, i.e technical specifications, are a measure of quality/scope, that's how the contract was formed... (Contractor)"; "...Quality is a very broad term, it is mostly related to client satisfaction...”.(Project Manager 3)

“…social infrastructure – user representative and project manager are key to quality and scope… civil infrastructure – designer / author of the feasibility study and supervising engineer affect the quality; all stakeholders defined in Building Act influence time and cost in all projects, and in EU co-financed projects intermediary body 2 can have a significant influence on quality and cost, even though this is not good...”(Project manager 3)

“infrastructure operator, contractor (for technically complex projects), designer, permits authorities, local community, Ministry of Interior Affairs, design supervision... there are many important stakeholders and depending on the project, some of them should definitely be engaged earlier if we want a good story in our project (Public client)”

“The client is extremely important because he formally has a contract with (internal) stakeholders, the project manager (PM) has quite limited mandate because he is external consultant, but there are situations where the client relies heavily on the PM because the PM, in most cases, has more competences in the field of engagement (at least for internal stakeholders)... ...PM in principle has the responsibility of engaging all stakeholders if he proves capable and if the client needs it, the client sometimes delegates a lot of responsibility to him, which can include communication with intermediary body 1 and 2 (of ESI funds) and certain external stakeholders...”(Project manager 2)

“...it is absolutely important and it is important that it be formalized, i.e. according to the best practices, for example according to the forms in standard PM'2... (Public client)"; "...formal management of stakeholders could bring improvements in management, but a balanced approach should be taken because it consumes energy and time..." (Client consultant)”

“(The procurement model) affects, directly and indirectly. It directly affects which internal stakeholder will be engaged, when and to what extent, and indirectly it affects how much this procurement model enables project manager and his team to implement their own approach to stakeholders and possibly to influence on some possible shortcomings which came from ill performed procurement procedure...”(Project manager 2)

"(technological complexity) It has some influence, and it is mainly related to competences, the more competent individuals and firms should have priority during tender. Sometimes you can influence if you have an incompetent project participant and sometimes you can't, it all depends on whether you can subcontract a part of services or works... (organizational complexity) It greatly affects all aspects, much more than technological complexity, it affects how much you can do and how you can do it and when and what will you do in relation to engagement of crucial stakeholders"(Project Manager 1)

"Soft certainly more... both serve and are very entwined, but if people are not motivated, encouraged in some way, not even the best procedure can help. Of course, the procedures serves it puropse, but sometimes people don't want to submit to the procedures or implement them in the right way... (Project manager 2)" ; "...if the "soft" ones don't work, then „hard“ are very important. First, a "soft" approach is tried e.g. an attempt is made to solve the problem through conversation, and if it does not work, then the defined procedures are strictly followed (if you are lucky enough that they are clearly defined)... if there are no major problems in the project, then the project (and the engagement of stakeholders) depends on "soft" skills..."(Project Manager 3)

„The client decision has the greatest influence. The decision refers to the expertise and desire of whether and how the client will engage an individual stakeholder (Supervising engineer)"; "..all this has a feedback loop, the engagement depends on the recipient (of the engagement) and not only on the one who engages. The combination of contractors, supervising engineer and other stakeholders is important... (Contractor)”

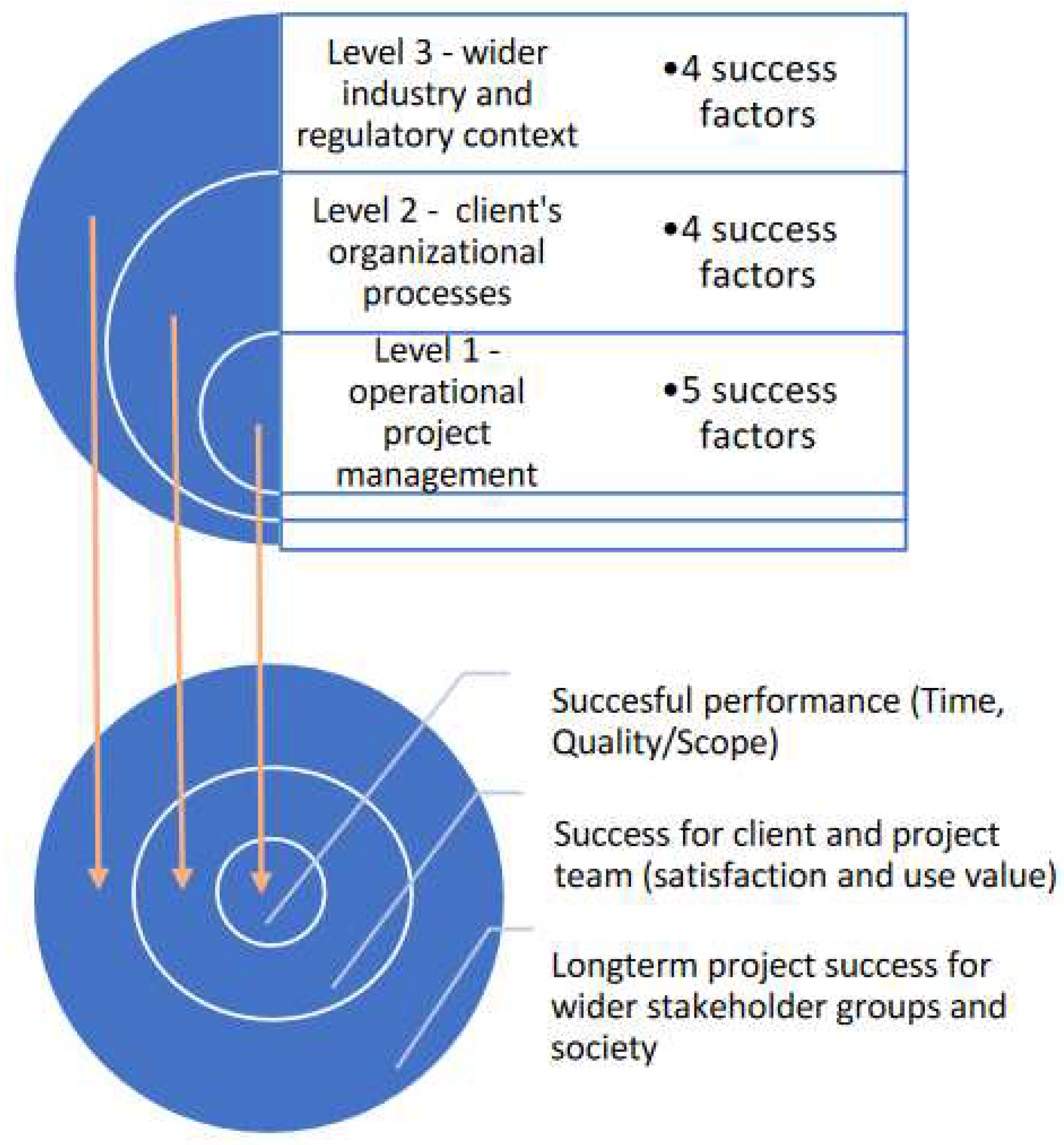

4.1. Identifying factors of success/failure and conceptualizing the framework model for stakeholder engagement in infrastructure projects

- Level 3 – The level of the broader industry and regulatory context – factors of success/failure that are related with aspects that are not under client organization or the project management direct influence

- Level 2 – Level of the client's organization (management and procurement) – factors of success/failure that are related with the client's organizational processes/activities and competences

- Level 1 – Level of operational project management – factors of success/failure that are related with activities/processes of the project manager and his core team

4.1.1. Level of operational project management approach (Level 1)

4.1.2. Level of processes and procedures of the client organization (Level 2)

4.1.3. The level of the broader industry and regulatory project context (Level 3)

4.2. Sumarry analysis and elaboration the framework model for engaging stakeholders and achieving success in infrastructure projects

4.3. Verification of developed conceptual framework

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A (Interview)

References

- Kumaraswamy, M.; Wong, K. K. W.; Chung, J. Focusing Megaproject Strategies on Sustainable Best Value of Stakeholders. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2017, 7 (4), 441–455. [CrossRef]

- Ninan, J.; Mahalingam, A.; Clegg, S. Power and Strategies in the External Stakeholder Management of Megaprojects: A Circuitry Framework. Engineering Project Organization Journal. 2020, pp 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Safa, M.; Sabet, A.; MacGillivray, S.; Davidson, M.; Kaczmarczyk, K.; Haas, C. T.; Gibson, G. E.; Rayside, D. Classification of Construction Projects. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. Int. J. Civil, Environ. Struct. Constr. Archit. Eng. 2015, 9 (6), 721–729.

- Dyer, M.; Dyer, R.; Weng, M.-H.; Wu, S.; Grey, T.; Gleeson, R.; Ferrari, T. G. Framework for Soft and Hard City Infrastructures. Urban Des. Plan. 2019, 172 (6), 219–227.

- Al-Bahar, J. F.; Crandall, K. C. Systematic Risk Management Approach for Construction Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 1990, 116 (3), 533–546. [CrossRef]

- Henisz, W. J.; Levitt, R.; Scott, W. R. Toward a Unified Theory of Project Governance: Economic, Sociological and Psychological Supports for Relational Contracting. Eng. Proj. Organ. J. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chan, A. P. C.; Le, Y.; Jin, R. From Construction Megaproject Management to Complex Project Management: Bibliographic Analysis. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31 (4).

- Agarwal, R.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Sridhar, M. Imagining Construction’s Digital Future. Capital Projects and Infrastructure, McKinsey Productivity Sciences Center, Singapore. 2016, p 13.

- Dunovic, I. B.; Prebanic, K. R.; Durrigl, P. Method for Base Estimation of Construction Time for Linear Projects in Front-End Project Phases. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. 2021, 13 (1), 2312–2326. [CrossRef]

- Mok, K. Y.; Shen, G. Q.; Yang, R. J.; Li, C. Z. Investigating Key Challenges in Major Public Engineering Projects by a Network-Theory Based Analysis of Stakeholder Concerns: A Case Study. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35.

- Rezvani, A.; Khosravi, P.; Ashkanasy, N. M. Examining the Interdependencies among Emotional Intelligence, Trust, and Performance in Infrastructure Projects: A Multilevel Study. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 1034–1046. [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. What You Should Know about Megaprojects and Why: An Overview. Proj. Manag. J. 2014, 45 (2).

- Nguyen, T. S.; Mohamed, S.; Mostafa, S. Project Stakeholder’s Engagement and Performance: A Comparison between Complex and Non-Complex Projects Using SEM. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2021, 11 (5), 804–818. [CrossRef]

- Prebanic, K. R.; Vukomanović, M. Realizing the Need for Digital Transformation of Stakeholder Management: A Systematic Review in the Construction Industry. Sustain. 2021, 13, 27. [CrossRef]

- Brunet, M.; Aubry, M. The Three Dimensions of a Governance Framework for Major Public Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1596–1607. [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; He, Q.; Jaselskis, E. J.; Xie, J. Construction Project Complexity: Research Trends and Implications. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143 (7).

- Volden, G. H. Public Project Success as Seen in a Broad Perspective. Lessons from a Meta-Evaluation of 20 Infrastructure Projects in Norway. Eval. Program Plann. 2018, 69, 109–117. [CrossRef]

- Pascale, F.; Pantzartzis, E.; Krystallis, I.; Price, A. D. F. Rationales and Practices for Dynamic Stakeholder Engagement and Disengagement Evidence from Dementia-Friendly Health and Social Care Environments. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38 (7), 623–639. [CrossRef]

- Cuppen, E.; Bosch-Rekveldt, M. G. C.; Pikaar, E.; Mehos, D. C. Stakeholder Engagement in Large-Scale Energy Infrastructure Projects: Revealing Perspectives Using Q Methodology. International Journal of Project Management. 2016, pp 1347–1359. [CrossRef]

- Müller, R. Project Governance; Gower Publishing, Ltd: London, 2009.

- Bahadorestani, A.; Karlsen, J. T.; Motahari Farimani, N. Novel Approach to Satisfying Stakeholders in Megaprojects: Balancing Mutual Values. J. Manag. Eng. 2020.

- Lehtinen, J.; Peltokorpi, A.; Artto, K. Megaprojects as Organizational Platforms and Technology Platforms for Value Creation. International Journal of Project Management. 2019, pp 43–58. [CrossRef]

- Chinyio, E. A.; Akintoye, A. Practical Approaches for Engaging Stakeholders: Findings from the UK. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2008, 26 (6), 591–599. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, K.; Kim, Y.-W.; Kim, H. Stakeholder Management in Long-Term Complex Megaconstruction Projects: The Saemangeum Project. J. Manag. Eng. 2017, 33 (4). [CrossRef]

- Heravi, A.; Coffey, V.; Trigunarsyah, B. Evaluating the Level of Stakeholder Involvement during the Project Planning Processes of Building Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33 (5). [CrossRef]

- Sydow, J.; Braun, T. Projects as Temporary Organizations: An Agenda for Further Theorizing the Interorganizational Dimension. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36 (1). [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Warris, M.; Panigrahi, S.; Rizwan Sajid, M.; Rana, F. Improving the Performance of Public Sector Infrastructure Projects: Role of Project Governance and Stakeholder Management. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37 (2), 20. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Waris, M.; Ismail, I.; Sajid, M.; Ullah, M.; Usman, F. Deficiencies in Project Governance: An Analysis of Infrastructure Development Program. Administrative Sciences. 2019, p 9. [CrossRef]

- Klakegg, O. J.; Williams, T.; Shiferaw, A. T. Taming the ‘Trolls’: Major Public Projects in the Making. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34 (2), 282–296. [CrossRef]

- Prebanic, K. R.; Dunović, I. B. Explicit and Implicit Relationship Between Stakeholder Management and Trust Concepts: Construction Project Management Perspective. In 14TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ORGANIZATION, TECHNOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT IN CONSTRUCTION AND 7TH INTERNATIONAL PROJECT MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATION RESEARCH CONFERENCE; 2019; pp 177–194.

- Mok, K. Y.; Shen, G. Q.; Yang, R. J.; Li, C. Z. Investigating Key Challenges in Major Public Engineering Projects by a Network-Theory Based Analysis of Stakeholder Concerns: A Case Study. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35 (1). [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. J.; Jayasuriya, S.; Gunarathna, C.; Arashpour, M.; Xue, X.; Zhang, G. The Evolution of Stakeholder Management Practices in Australian Mega Construction Projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25 (6), 690–706. [CrossRef]

- Collinge, W. H. Stakeholder Engagement in Construction: Exploring Corporate Social Responsibility, Ethical Behaviors, and Practices. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020.

- Jugdev, K.; Müller, R. A RETROSPECTIVE LOOK AT OUR EVOLVING UNDERSTANDING OF PROJECT SUCCESS. Proj. Manag. J. 2005, 36 (4), 19–31.

- Albert, M.; Balve, P.; Spang, K. Evaluation of Project Success: A Structured Literature Review. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business. 2017, pp 796–821. [CrossRef]

- Cooke-Davies, T. The “Real” Success Factors on Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2002, 20 (3), 185–190. [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Turner, J. R. The Influence of Project Managers on Project Success Criteria and Project Success by Type of Project. European Management Journal. 2007, pp 289–309.

- Gunathilaka, S.; Tuuli, M. M.; Dainty, A. R. J. Critical Analysis of Research on Project Success in Construction Management Journals. Proceedings 29th Annual Association of Researchers in Construction Management Conference, ARCOM 2013. 2013, pp 979–988.

- Turner, R.; Zolin, R. Forecasting Success on Large Projects: Developing Reliable Scales to Predict Multiple Perspectives by Multiple Stakeholders Over Multiple Time Frames. Proj. Manag. J. 2012, 10.

- Pinto, J. K.; Slevin, D. P. Project Success: Definitions and Measurement Techniques. Proj. Manag. J. 1998, 19 (1).

- He, Q.; Wang, T.; Chan, A. P. C.; Xu, J. Developing a List of Key Performance Indictors for Benchmarking the Success of Construction Megaprojects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147 (2). [CrossRef]

- Koops, L.; Bosch-Rekveldt, M.; Coman, L.; Hertogh, M.; Bakker, H. Identifying Perspectives of Public Project Managers on Project Success: Comparing Viewpoints of Managers from Five Countries in North-West Europe. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34 (5), 874–889. [CrossRef]

- Koops, L.; van Loenhout, C.; Bosch-Rekveldt, M. Different Perspectives of Public Project Managers on Project Success. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2017.

- Williams, T. Identifying Success Factors in Construction Projects: A Case Study. Project Management Journal. 2015, pp 97–112.

- Al-Tmeemy, S. M. H. M.; Abdul-Rahman, H.; Harun, Z. Future Criteria for Success of Building Projects in Malaysia. International Journal of Project Management. 2011, pp 337–348. [CrossRef]

- Bryde, D. J.; Robinson, L. Client versus Contractor Perspectives on Project Success Criteria. International Journal of Project Management. 2005, pp 622–629. [CrossRef]

- Vuorinen, L.; Martinsuo, M. Value-Oriented Stakeholder Influence on Infrastructure Projects. International Journal of Project Management. 2019, pp 750–766. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J. K.; Slevin, D. P. Critical Factors in Successful Project Implementation. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1987, 34 (1), 22–27. [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. Reconciling the Views of Project Success: A Multiple Stakeholder Model. Proj. Manag. J. 2018, 49 (5), 38–47. [CrossRef]

- Jha, K. N.; Iyer, K. C. Commitment, Coordination, Competence and the Iron Triangle. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 25 (5), 527–540. [CrossRef]

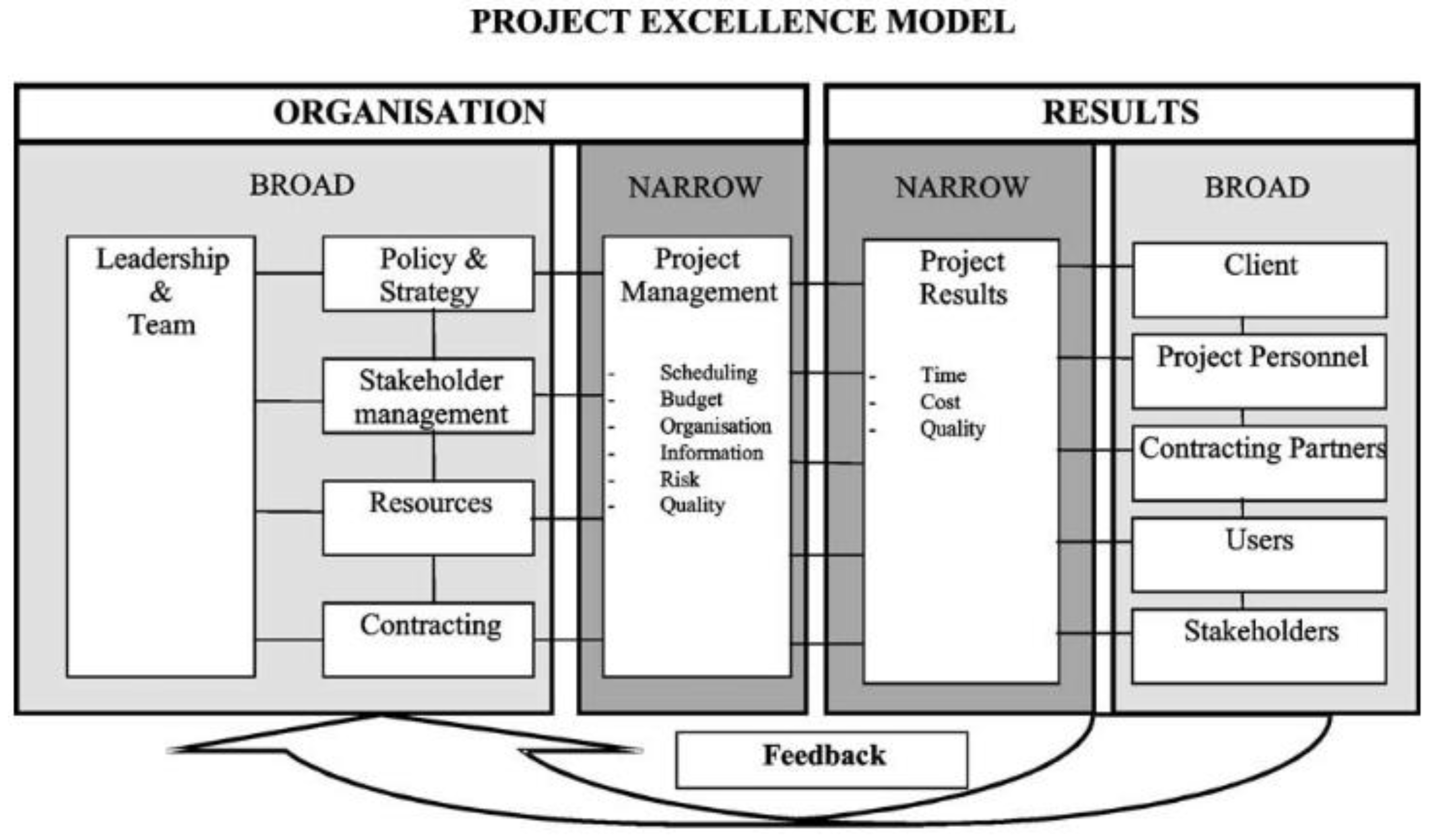

- Westerveld, E. The Project Excellence Model®: Linking Success Criteria and Critical Success Factors. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21 (6), 411–418. [CrossRef]

- Grau, N. Standards and Excellence in Project Management – In Who Do We Trust? Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 74, 10–20. [CrossRef]

- Yong, Y. C.; Mustaffa, N. E. Critical Success Factors for Malaysian Construction Projects: An Empirical Assessment. Construction Management and Economics. 2013, pp 959–978. [CrossRef]

- Aapaoja, A.; Haapasalo, H.; Soderstrom, P. Early Stakeholder Involvement in the Project Definition Phase: Case Renovation. ISRN Ind. Eng. 2013, Volume 201, 14.

- Love, P. E. D.; O’Donoghue, D.; Davis, P. R.; Smith, J. Procurement of Public Sector Facilities Views of Early Contractor Involvement. Facilities 2014, 32 (9/10), 460–471.

- Di Maddaloni, F.; Davis, K. The Influence of Local Community Stakeholders in Megaprojects: Rethinking Their Inclusiveness to Improve Project Performance. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35 (8). [CrossRef]

- Erkul, M.; Yitmen, I.; Celik, T. Dynamics of Stakeholder Engagement in Mega Transport Infrastructure Projects. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2020, 13 (7), 1465–1495.

- Aaltonen, K. Stakeholder Management in International Projects. 2010, p 134.

- Bourne, L. Targeted Communication: The Key to Effective Stakeholder Engagement. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 226, 431–438. [CrossRef]

- Aaltonen, K.; Sivonen, R. Response Strategies to Stakeholder Pressures in Global Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2009, 27 (2), 131–141. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. J.; Shen, G. Q. P. Framework for Stakeholder Management in Construction Projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31 (4), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Aaltonen, K.; Kujala, J. A Project Lifecycle Perspective on Stakeholder Influence Strategies in Global Projects. Scand. J. Manag. 2010, 26 (4), 381–397. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shen, G. Q.; Bourne, L.; Ho, C. M.; Xue, X. A Typology of Operational Approaches for Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29 (2), 145–162. [CrossRef]

- Mok, K. Y.; Shen, G. Q.; Yang, J. Stakeholder Management Studies in Mega Construction Projects: A Review and Future Directions. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33 (2), 446–457. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Luo, M.; Zhang, Y. Impact of Megaproject Governance on Project Performance: Dynamic Governance of the Nanning Transportation Hub in China. J. Manag. Eng. 2019, 35 (3).

- Winch, G. M. Managing Construction Projects; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, United Kingdom, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Ahola, T.; Ruuska, I.; Artto, K.; Kujala, J. What Is Project Governance and What Are Its Origins? Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32 (8), 1321–1332.

- Biesenthal, C.; Wilden, R. Multi-Level Project Governance: Trends and Opportunities. International Journal of Project Management. 2014, pp 1291–1308. [CrossRef]

- Too, E. G.; Weaver, P. The Management of Project Management: A Conceptual Framework for Project Governance. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32 (8). [CrossRef]

- Bekker, M.; Steyn, H. Defining ‘Project Governance’ for Large Capital Projects. In AFRICON; 2007; pp 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Klakegg, O. J.; Williams, T.; Magnussen, O. M. Design of Innovative Government Frameworks for Major Public Investment Projects: A Comparative Study of Governance Frameworks in UK and Norway. In The International Research Network on Organizing by Projects (IRNOP VIII): Project Research Conference, Sussex, UK; 2007; p 22.

- The State of Queensland. Gateway Review Guidebook for Project Owners and Review Teams. 2013, p 17.

- Office of Government Commerce. The OGC Gateway Process: Gateway to Success. 2004, pp 4–5.

- Burcar Dunović, I. Upravljanje Rizicima Kod Velikih Infrastrukturnih Projekata, PhD Thesis, University of Zagreb. Zagreb, HR, 2012.

- European Commision Centre of Excellence. The PM2 Project Management Methodology Guide. 2016, p 147. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Regional Development and EU funds. Operational Programmes https://razvoj.gov.hr/o-ministarstvu/djelokrug-1939/eu-fondovi/financijsko-razdoblje-eu-2014-2020/operativni-programi/356.

- The Croatian Chamber of Economy. Cohesion Policy of European Union and Croatia 2014 - 2020: Guide through the Strategic Framework and an Overview of Funding Opportunities; 2015.

- Technical Gazzete NN92/14. Act on the Establishment of an Institutional Framework for the Implementation of European Structural and Investment Funds in the Republic of Croatia in the Period 2014-2020; 2014.

- Technical Gazzete NN 107/2014. Regulation on Bodies in the Management and Control Systems of the Use of the European Social Fund, the European Fund for Regional Development and the Cohesion Fund, in Connection with the Objective “Investment for Growth and Jobs”; 2014.

- European Commission. Europa, Regional Policy, Major projects https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/projects/major/.

- Central Agency for Financing and Contracting. Handbook for Beneficiaries of Grants; within the Framework of Projects Financed from European Structural and Investment Funds; 2018.

- Fellows, R.; Liu, A. Research Methods for Construction. 2015, p 302.

- Milas, G. Istraživačke Metode u Psihologiji i Drugim Društvenim Znanostima, 2. Izdanje; Naklada Slap: Jastrebarsko, 2009.

- Walker, D. H. T.; Lloyd-Walker, B. M. Understanding the Motivation and Context for Alliancing in the Australian Construction Industry. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2016, 9 (1), 74–93. [CrossRef]

- Brunet, M. Governance-as-Practice for Major Public Infrastructure Projects: A Case of Multilevel Project Governing. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 283–297. [CrossRef]

- Di Maddaloni, F.; Davis, K. Project Manager’s Perception of the Local Communities’ Stakeholder in Megaprojects. An Empirical Investigation in the UK. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017.

- Molwus, J. J.; Erdogan, B.; Ogunlana, S. O. A Study of the Current Practice of Stakeholder Management in Construction Projects. Procs 30th Annual ARCOM Conference, 1-3 September 2014. 2014, pp 945–954.

- Bosch-Rekveldt, M.; Jongkind, Y.; Mooi, H.; Bakker, H.; Verbraeck, A. Grasping Project Complexity in Large Engineering Projects: The TOE (Technical, Organizational and Environmental) Framework. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010.

- Aaltonen, K.; Kujala, J. Towards an Improved Understanding of Project Stakeholder Landscapes. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34 (8), 1537–1552. [CrossRef]

| Name/description of success model (author and year of published article) | Construction stakeholder type which perspective was considered | The category of success criteria and the number of associated success criteria or measures |

|---|---|---|

| Success criteria of buildings projects (Al-Tmeemy et al., 2011) | Contractors (project) perspective | Project management success (3 criteria) Product success (3 criteria) Market success (4 criteria) |

| Project success criteria (Williams 2015) | Contractors (organization) perspective | Was the final product good? (3 measures/criteria) Were the stakeholders satisfied with the project? (5 measures/criteria) Did the project meet its delivery objectives? (3 measures/criteria) Was project management successful? (6 measures/criteria) |

| Dimensions of project value, (Vuorinen and Martinsuo, 2019) | Perspective of public client/government and wider society | Social and environmental value (descriptive) Financial value (descriptive) Systemic value (descriptive) |

| KPIs for assessing construction megaproject success (He et al., 2021) | Perspective of public client/government | Project efficiency (3 KPI) Key stakeholders’ satisfaction (2 KPI) Organizational strategic goals (2 KPI) Comprehensive impact on society (2 KPI) |

| Years of experience in construction and project management; education | The project role(s) they perform in projects | The type of infrastructure projects respondent has experience with | Phases of the project in which they participate (see Appendix A) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project manager 1 | 20 in construction and 16 in project management; Civil engineer | Construction project management, client consultation and construction supervision | Civil - i.e roads, railroads, water agglomeration… Social – i.e hospitals schools… |

Most often in the last 2 stages, sometimes in the last 3, and there were rare cases from the early stages |

| Project manager 2 | 28 in construction and 20 in project management; Civil engineer | Construction project management, client consultation and construction supervision | Civil - i.e water agglomeration, waste management centers, ports and marines… Social – i.e hospitals schools… |

Most often in the last 2 stages, sometimes in the last 3, and there were rare cases from the early stages |

| Project manager 3 | 20 in construction and 10 in project management; Civil engineer | Consulting in planning and monitoring and control; Construction project management | Civil - i.e roads, water agglomerations Social – i.e schools, courts… |

Most often in the last 2 stages, sometimes in the last 3, and there were rare cases from the early stages |

| Public client consultant | 12 in consultancy (project management), 7 in construction; Economist | Consultations in the preparation of study and tender documentation; project management | Civil - water agglomeration Social - visitor centers, adaptations of cultural buildings… |

Most often early stages in the capacity of consulting, in the case of project management in all stages |

| Public client | 20 in construction and project management; Civil engineer | Consulting in planning, monitoring and control | Civil – i.e roads, waste management centers, power plants, airports … | Most often in the last 4 phases, there are examples in all phases (sometimes only early phases) |

| Supervising engineer/FIDIC engineer | 15 in construction and project management; Civil engineer | Construction supervision and construction project management | Civil – i.e roads, water agglomerations Social – i.e social housing (POS) |

Most often in the last two stages, very rarely earlier |

| Designer | 20 in construction and 15 in project management; Civil engineer | Designing, design supervision; construction supervision; project management | Civil - i.e roads, water, agglomerations… Social – i.e hospitals schools… |

Most often in the last four phases |

| Contractor | 23 in construction and 17 in project management (contractor side); Civil engineer | Contractor | Civil – waste water treatment device Social – school, hospital |

Most often in the last 3 phases, and rarely in the last 5 (within the "design and build" procurement model) |

| Success/failure factors | Suggestions for improvement on these factors (project management level) |

|---|---|

| 1) Some stakeholders must be prioritized because of their influence (those named in Building Act and project manager. In some cases, additional few due to specific complex project environment) | For prioritized stakeholders, it is necessary to systematically approach to the planning and the implementation of the operational engagement approach (i.e use tools and methods). It is proposed to create a separate detailed (formal) approach. Other stakeholders are considered as a lower priority but constantly monitored. If they acquire more influence, set them as a higher priority. |

| 2) There are several key activities/approaches of engagement that must be systematically implemented in the project (e.g. SE1 – enable relevant stakeholders to provide inputs in scope definition for the project and/or phase(s) when starting the project and/or phases…) | The effectiveness of seven stakeholder engagement activities/processes was confirmed (part of other research). It is necessary to pay attention to these processes and systematically carry out related activities. Depending on the project phase, certain activities should be strengthened for the currently engaged (influential) stakeholders. |

| 3) Procurement model and defined responsibilities (through contracts) have great influence on the abilities to properly engage project stakeholders. | Educate the project manager and his team to assist clients in procurement process, especially in elaboration of key roles and responsibilities for internal stakeholders through the 'procurement tender documentation'. It is necessary to ensure that the responsibilities of stakeholders do not overlap or are not overlooked. |

| 4) The complexity of project organization and environment has a significant influence on the stakeholder engagement approach | Acquire/Improve competences and develop methods for evaluating the organizational complexity of the project, namely the complexity and dynamism of project stakeholder landscapes. Also, develop method to tailor engagement strategies according to the level of complexity and dynamism in the project. |

| 5) Great importance of both "soft" and "hard" skills for proper engagement of stakeholders in infrastructure projects. "Soft" are a little more emphasized. | Raising competences related to people, for example in the form of communication, coordination, cooperation, engagement, and negotiation. Also, raising technical competencies such as planning, monitoring and control for key project aspects, ie time, cost, quality, scope, technical performance. |

| Success/failure factors | Suggestions for improvement on these factors (client’s organization management and procurement level) |

|---|---|

| 1) The project manager needs to be engaged earlier than the usual (current) practice to enable proper engagement of other key stakeholders. | Improve the current practice and procedure of giving mandate to the project manager. It is necessary to systematically design the project development process in the early stages, i.e. to clearly define the moment of involvement of the project manager, especially if procurement is carried out for (external) project management services (e.g. develop and implement a project management framework) |

| 2) Procurement model and defined responsibilities (through contracts) have great influence on the abilities to properly engage project stakeholders. | After obtaining the project mandate, refer to the delimitation of the responsibilities of the client team and the project manager regarding the organization of the project procurement process, and the implementation of the procurement plan (i.e a series of public procurements). Also, determine the responsibilities for the process of communication and negotiation in a particular procurement procedure. |

| 3) The complexity of project organization and environment has a significant influence on the stakeholder engagement approach | Plan the number and size of different procurements, e.g. contracts, and control procedures depending on the assessment of the project complexity to enable better conditions for engagement. Try to reduce the number of different procurements depending on the complexity (e.g., to combine certain services into one contracts) or, if necessary, to increase the number of procurements (e.g, one larger contract is separated into a few smaller). This directly affects the final number of stakeholders and their mutual relations. |

| 4) Significant differences in the engagement of external (non-contractual) stakeholders is often a source of unforeseen risks | Educate the employees of public contracting authorities on the importance of the discipline of engaging interested parties and its proper or formal application in the project to establish a uniform and high-quality approach to external interested parties in each project. For example, access to public consultation, i.e. access to the local community that is located in the immediate vicinity (of the works) of the project. |

| Success/failure factors | Suggestions for improvement on these factors (level of broader industry and regulatory context) |

| 1) Some stakeholders must be prioritized because of their influence (those named in Building Act and project manager. In some cases, additional few due to specific complex project environment) | Amend the Building Act and name the role of construction project manager and specify its legal responsibility or detail his responsibilities listed in Act on Business and Actions in Spatial Planning and Construction. Other possible way is to provide guideline for the relationship between the construction project manager and other project participants. Also, it is possible to legally introduce "other" stakeholders which represent usual public or private interests (that may or may not appear in the project). |

| 2) The project manager needs to be engaged earlier than the usual (current) practice to enable proper engagement of other key stakeholders. | It is possible to implement special procedures for complex or financially significant projects (the timing and extent of responsibility of key stakeholders can depend on the type of project, the complexity of the project or the size of the largest contract). This aspect is often part of project governance frameworks (i.e. EU and UK both have definition of Major/Critical projects with its specific management framework). Devising the governance framework can also clarify the project early stages and enable better context for proper stakeholder engagement. |

| 3) Procurement model and defined responsibilities (through contracts) have great influence on the abilities to properly engage project stakeholders. | Introduce new types/models of the so-called collaborative contractual arrangements. Adopt the practices tried in some countries (e.g. Australia, UK, Norway, OECD guidelines) to move towards a procurement model that falls within the spectrum of collaborative procurement arrangements. In these collaborative models the most attention is put on the cooperation of the client and the delivery team from the earliest stages. |

| 4) Significant differences in the engagement of external (non-contractual) stakeholders is often a source of unforeseen risks | On a broader level of the entire industry effort is needed to change the perception about involving stakeholders in important project decisions (not only because of their intrinsic value but also because of the risks that arise if certain interests/stakes are neglected). In process of developing the public strategies and programs, new governance frameworks can be introduced. These frameworks should emphasize engagement of infrastructure end users and the local community and thus honestly advocate sustainability and value co-creation. |

| Verification questions (in their short form) | Verifier 1 | Verifier 2 | Verifier 3 | Verifier 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. What do you think about the proposed breakdown of factors into 3 levels… | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 2. ...the client and the project manager of the two key stakeholders for the implementation... | 5 | 4,5 | 5 | 5 |

| 3. …the proposed framework enhances your understanding of SE… | 4 | 4,5 | 4 | 3 |

| 4. Suggestions for exploiting and improving factors related to stakeholder engagement are appropriate… | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 5. ...the framework model covers most of the factors of successful execution related to SE... | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| 6. ...the proposed framework can contribute to the organization of the client... | 3 | 4,5 | 3 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).