1. Introduction

Conspiracy beliefs in age of COVID-19 were distinctly prevalent. They were updated on multiple themes such as wearing masks, vaccines, the idea of the coronavirus as a biological weapon, oligarchic and government interventions with financial and economic motives and etc. [

1]. Research has recently proposed a social-functional model of conspiracy beliefs in which precarity is a central psychosocial construct. Adam-Troian et al. [

2] argue that precarity expands the social-psychological lore of conspiratorial attitudes as an indirect consequence of structural issues, for example, social inequalities. They define precarity as the subjective experience of persistent social and psychological insecurity within objective conditions of affiliation and economic deprivation. Perspective for precarity as a motivation of the conspiracy mentality, related as ontological uncertainty and existential threat [

3,

4,

5], is inherently affective. The way one projects oneself into the future suffers. A theoretical pole of that theory is ontological security, which implies fundamental senses of safety and trust suistaining to individual psychological well-being. According to the authors, people perceive conspiracy narratives through an already shaped basic sense of (dis)trust [

2]. In this way, the idea is articulated that contexts actualize affective human nature based on personal phenomenological experience.

The critical epidemic realities narrowed psychosocial functioning to a common pattern of public health regulation in all countries that have been affected by SARS-CoV-2. In turn, this pattern has opened up space for polarization in different societies [

6,

7,

8,

9]. While political polarization is better outlined, socio-psychological polarization is more delicate to explore. Some authors have analyzed cognitive rigidity and neglecting alternative information in interpretation of fake and real news as socio-cognitive polarization [

10]. Intragroup antagonistic tendencies in political and ideological contexts have been described as affective polarization. It has been established that affective polarization is related to phenomena of agonistic democracy and anti-democratic attitudes [

11,

12]. There is evidence that empathic concern, a latent trait of empathy, increases levels of affective polarization [

13]. Research on the relation between personality traits and affective polarization is actually insufficient and has concentrated on bias behavior and political preferences [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Personality traits explain the cognitive reading of reality, but group dynamics are moderated by universal variables as identity and belonging [

18,

19,

20]. We assume that the social-affective framework conceptually most syncretic for understanding the background of the current investigation, as described in the sections to follow.

The measures to protect against the viral invasion of COVID-19 were simple and universal – physical distancing, physical hygiene and long-term adherence to policies limiting all forms of group contact [

21]. However, human functioning in its integrative sense could not be simple and universal. Personality is an individual organization of a psychobiological system (body, thoughts, psyche), within which a person modulates their experience and adapts to an ever-changing internal and external environment [

22,

23]. Research on the psychobiological model of personality has operationalized well-being as an implicit variable of the functioning of human beings. More specifically, a tripartite structure of subjective well-being is investigated – positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction, and these components are analyzed and assessed both independently and jointly. Thus, the contribution of individual traits (temperament and character traits) to people's adaptive functioning reflected in well-being is well-established. Subjective well-being encompasses cognitive and emotional aspects of subjective feelings regarding individual life circumstances. Individual differences in positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction are explained by different organizations of psychobiological systems and processes [

24]. These differences correspond to three distinct systems of human learning and memory described as associative conditioning, intentional self-control, and self-awareness. Recent results show that negative affect and life satisfaction are dependent on a personality network for intentional self-control, and positive affect is dependent on a personality network for self-awareness [

25].

Globally, conspiracy beliefs were associated with low adherence to anti-epidemic public health guidelines. COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs also mediate a negative relation between national narcissism and engagement in health behaviors [

26]. In the same timeframe and within the same population survey, a positive association between conspiracy beliefs and dimensions of Moral Identity and Morality-as-Cooperation was found. This finding was interpreted as a dilemma in people's moral judgment that determines their behavior with regards to public health [

27]. Moral identity is associated with commitment, meaning, identification with and acceptance of others (Cooperativeness) and with feeling that one is part of something bigger than oneself (Self-transcendence)[

28]. Internalized moral identity was the most consistent predictor of attitudinal and behavioral responses to COVID-19. Morality-as-Cooperation was associated with the behavioral responses, most consistently in predicting hygiene maintenance. Open-mindedness and self-control were positively associated with avoiding contact and supporting policy, and Open-mindedness was interpreted as an aspect of cognitive humility, or the virtue of being able to accept one's fallibility and the willingness to accept information contrary to one's initial beliefs. Social Belonging predominantly predicted hygiene maintenance. Collective narcissism was a predictor of political support, and contact avoidance [

29]. We have theoretical and objective reasons to consider these results in the affective perspective of precarity and ontological certainty, of adaptation and subjective well-being. With a particular reference to Bulgarian context, recent studies of well-being and values-based mental health studies indicate the controversies and compromise which underpin the mental health in view of the cultural pluralism in Bulgaria [

30,

31].

Under the psychobiological paradigm as explanatory model, we argue that in collective behavior the individual organization of the psychobiological system is always revealed in an affective configuration of adaptive and maladaptive modalities. Our primary purpose was to distinguish traits and tendencies in PHS behaviors that are well established to be associated with affective dimensions of personality functioning.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

We conducted an online survey in Bulgarians that was part of International Collaboration on Social & Moral Psychology of COVID-19 (ICSMP) [

32]. A large multinational sample was generated with data from over 50,000 citizens [

33]. Within two months from the beginning of April to the end of May 2020, the survey was active and distributed through an administrative online link to which our research team had regular permanent access. A Google form was created, which was addressed on behalf of the Medical University of Plovdiv to its employees, students and their families, to the wider community and to institutional partners. The introductory section of the online form was unified according to project policy. It contained a summary of the purpose of the study, informed consent options and approval from Research Ethics Committee, University of Kent, United Kingdom, No. 202015872211976468. Also, we received an institutional support for conducting the research from Medical University of Plovdiv within the framework of a currently active national project, named "COVID-19 HUB – Information, Innovations and Implementation of Integrative Scientific Developments" in thematic area of Medical-biological problems, financed by the Bulgarian National Science Fund under contract No. KP-06-DK1/6 dated 29/03/2021.

Our sampling was by snowball method. The Bulgarian sample included 794 individuals. After data cleaning, 733 Bulgarian participants were included in this study.

We translated into Bulgarian the original English text of the survey using forward-backward method. The instrument essentially can be seen as a battery of self-assessment tests. Then we dedicated time to an independent psycholinguistic evaluation of the Bulgarian text to ensure feasibility of items toward Bulgarian cultural attitudes. To that end, we conducted a pilot online survey with feedback from respondents, which informed further revisions to the text. This turned out to be critically important, as the timing of research historically preceded the several epidemiological waves of the pandemic and the impact of world statistics in term to mortality and infection with coronavirus later. We conceptually tested both Bulgarian-specific and culture-independent psychological constructs.

2.2. Measures

Methodology, study materials, raw and cleaned data, codes, and translations, are shared in The Open Science Framework (OSF) repository accessible to all teams contributing to the global database [

32]. Cronbach's Аlpha coefficient was > 0.700 for most scales, according to the generally accepted interpretation for reliability (

Table 1). In the current study, we report results for the constructs described below.

Outcome variables

Public health support (PHS) behavior was assessed using the constructs Physical Contact (α=0.684), Physical Hygiene (α=0.756), and Anti-Corona Policy Support (α=0.859), which were developed as ad-hoc scales by leading authors of ICSMP.

Respondents self-assessed their behavior on items: ”Staying at home as much as practically possible”, “Visiting friends, family, or colleagues outside my home”, “Keeping the number of grocery store visits at an absolute minimum”, “Keeping physical distance from all other people outside my home”, “Avoiding handshaking with people outside my home”, Washing my hands longer than usual”, “Washing my hands (with soap) more thoroughly than usual”, Always washing my hands immediately after returning home”, “Disinfecting frequently used objects, such as mobile phones and keys”, “Sneezing and coughing into my upper sleeve”, “In favor of closing all schools and universities”, “In favor of closing all bars and restaurants”, “In favor of closing all parks”, “In favor of forbidding all public gatherings where many people are gathered at one place (sports and culture”, “In favor of forbidding all non-necessary travel” (0-Strongly Disagree, 100-Agree).

Predictor variables

Conspiracy Theories COVID-19 (α=0.893) were assessed by statements: “The coronavirus is a bioweapon engineered by scientists”, “The coronavirus is a conspiracy to take away citizen’s rights for good and establish an authoritarian government”, “The coronavirus is a hoax invented by interest groups for financial gains”, “The coronavirus was created as a cover up for the impending global economic crash” (0-Strongly disagree, 10- Strongly agree).

COVID-19 Risk Perception (α=0.752) was assessed by answering questions: “By April 30, 2021: How likely do you think it is that you will get infected by the Coronavirus?”, “By April 30, 2021: How likely do you think it is that the average person in Bulgaria will get infected by the Coronavirus?” (0% = Impossible, 50% = Neither likely nor unlikely, 100% = Certain).

Identity and Social Attitudes were represented by scales National Identification (α=0.550), Collective Narcissism (α=0.838), and Social Belonging (α=0.778). The statements on these scales examine the extent to which a person identifies with his or her nation and with a reference group (0-Strongly Disagree, 10-Agree).

Psychological well-being (α=0.769) dimension was related with self-assessment of feeling of happiness and satisfaction with life in the current moment (0-Very unhappy, 10-Very happy, 0-Worst possible life, 10-Best possible life).

Moral Beliefs and Motivation were explored with the Morality-as-Cooperation (α=0.339) and Moral Identity (α=0.772) scales (0-Strongly Disagree, 10-Agree).

There were examined the personality traits Open-mindedness (α=0.561), Trait Optimism (α=0.833), Trait Self-control (α=0.577), and Narcissism (α=0.759). The items reflected tolerance to learning and mistakes, optimistic/pessimistic attitudes, self-control skills, and narcissistic characteristics (0-Strongly Disagree, 10-Agree).

Some of scales contained reversed items. In the Bulgarian adaptation of the study, we kept the range from 0 to 10 for all scales. According us this is closer to our ethnocultural attitude. After reviewing the raw data, we transformed the obtained scores into a five-point Likert scale so that neutral ratings would be interpreted more refined. Then we analyzed the scales for each construct as interval variables.

Confounding variables

Quantitative and qualitative data on age, sex, marital status, number of children and employment status were collected.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

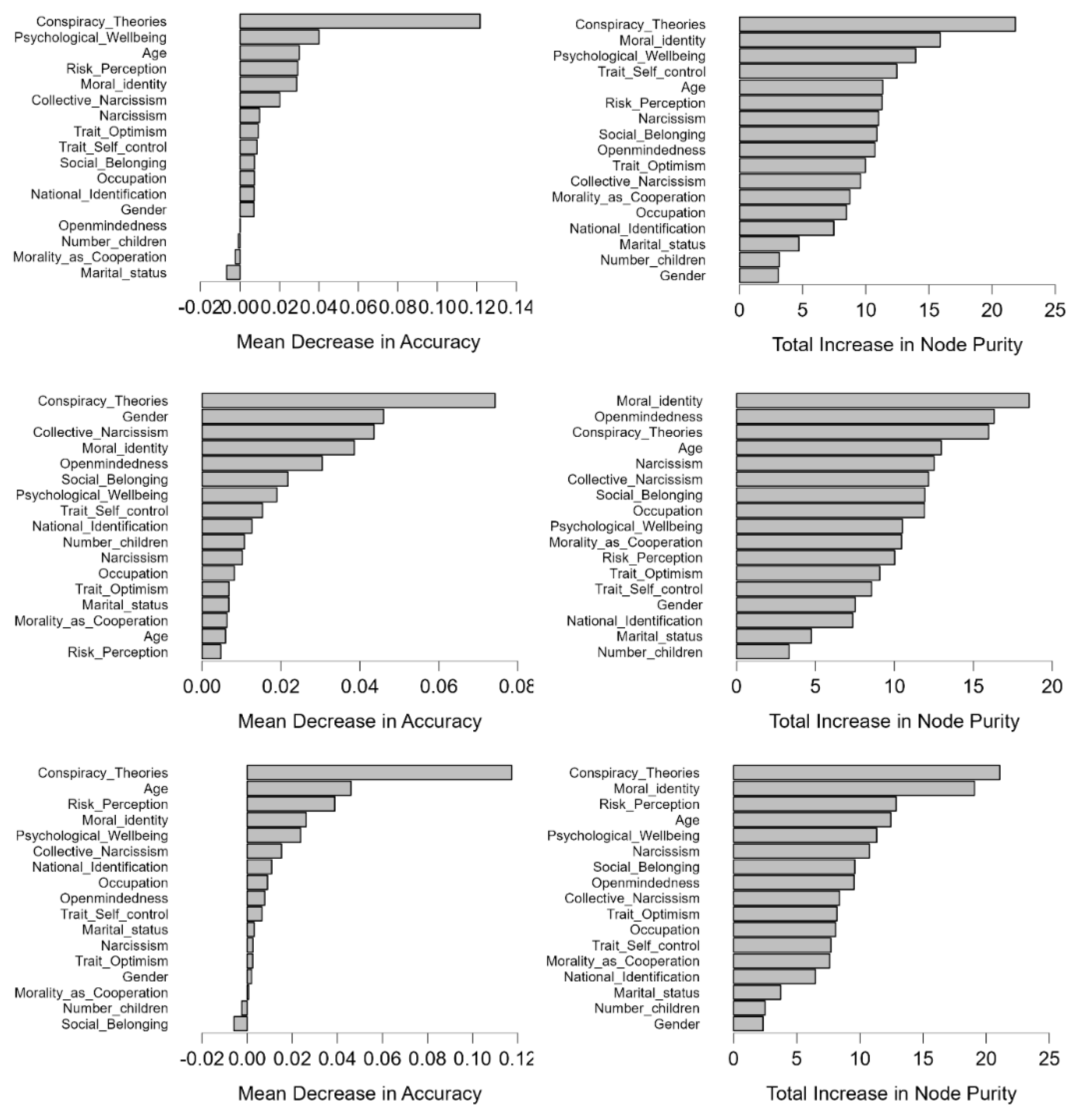

We used two complementary approaches to establish the relative importance of different participant psychosocial characteristics as predictors of the Physical Contact, Physical Hygiene, and Anti-Corona Policy Support scales. The first analytic step was to assess data distribution and distributional assumptions (

Table S1), reliability, and bivariate relations between variables. We approached the data agnostically using a random forest machine learning algorithm to empirically identify which predictors contribute most to explaining COVID-19 Beliefs and Compliance variables. The algorithm uses 50% of the data in the machine learning sample of each tree (maximum number of decision trees 100). For validation and test of the algorithm, 20% of cases in the sample were used. Model evaluation was done using Mean squared error (MSE), Root mean squared error (RMSE) and R2 indicators. The predictor importance was assessed by plotting the indicators Mean decrease in accuracy and Total increase in node purity, with higher values indicating greater impact of the predictor. As a next and main analysis step, we used linear regression models to test the significance of the predictors. All predictors were tested as independent variables simultaneously, the effect of each being adjusted for the influence of the others. Tests for multicollinearity between the predictors showed that there was no reason for concern (VIF < 5 and Tolerance index > 0.2) and they could be tested simultaneously. The analysis sample size was lower for these models (N=615) due to missing data. A statistical significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted.

All analyses were performed with SPSS Version 28.0 and JASP Version 0.17.1.

3. Results

Cronbach's Аlpha coefficient was > 0.700 for most scales, according to the generally accepted interpretation for reliability (

Table 1). We refrain from interpreting Cronbach's Alpha values < 0.700 as a sign of low reliability, since concrete scales are composed of a small number of items [

34,

35,

36]. Here, we refer to the Physical Contact, National Identification, Morality-as-Cooperation, and Open-mindedness scales. Breadth or narrowness of the construct measured can impact on the scale’s reliability coefficient [

37].

From

Table 2, the sample was unbalanced and not representative of the general population. Most participants were female, and mostly in their thirties, with the youngest being 18 and the older 69 years old. The majority were in a committed relationship, and employed full-time.

Table 3 shows correlations between the variables in the study. We observed two polar trends regarding public health support. The behavior of compliance to all measures of physical distance, hygiene and the recommended social-distancing policies was positively associated with higher Open-mindedness, Moral Identity and Risk Perception. Psychological well-being was strongly associated with contact avoidance and support for restrictive policies. Maintaining physical hygiene also positively correlated with Collective Narcissism, Morality-as-Cooperation, Trait Optimism, Social Belonging, and Trait Self-Control. On other hand, conspiracy beliefs were associated with lower compliance to public health measures, lower Risk Perception and with narcissistic traits and attitudes. Conspiracy beliefs are inversely related to Open-mindedness, but associated with Morality-as-cooperation, optimism and self-control.

Main analyses

We approached the data agnostically using a random forest machine learning algorithm to empirically identify which predictors contribute most to explaining COVID-19 Beliefs and Compliance variables. Results of the random forest models exploring the contribution of participant characteristics to the outcomes are shown in

Figure 1. Belief in conspiracy theories was the most influential predictor of all outcomes. Moral Identity also ranked relatively high as a predictor of Physical Hygiene and Anti-Corona Policy Support.

Next, we tested these observations with multivariate regressions, shown in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6. Physical Contact was explained at 18%, with several variables as significant predictors. That is, less Conspiracy theories beliefs, higher Collective Narcissism, Open-mindedness, higher Trait Self-Control, Moral Identity, Risk Perception, and Psychological Well-Being were associated with higher levels of Physical Contact. Women reported higher Physical Contact scores than men (

Table 4).

A similar trend was observed for Physical Hygiene, where conspiracy theories beliefs related to lower Physical Hygiene, while higher Collective Narcissism, Moral Identity, and Psychological Well-Being, with better Physical Hygiene (

Table 5). Women and participants in a relationship reported higher Physical Hygiene than men and those who were single. This model explained 14% of the variance in Physical Hygiene.

In the third model, 25% of the variance in Anti-Corona Policy Support was explained. Once again, Conspiracy Theories were significantly associated with weaker Anti-Corona Policy Support, while higher Collective Narcissism, Moral Identity, Risk Perception, and Psychological Well-Being, and being a woman were associated with stronger Anti-Corona Policy Support.

4. Discussion

We observed two polar trends in the public health behavior of Bulgarians. The first trend of public health non-support revealed more complex dependencies. Conspiracy beliefs were a significant predictor of lower compliance with public health anti-epidemic measures, as was found in most countries included in the global survey [

26]. On the one hand, Conspiracy Theories beliefs were significantly associated with lower Risk Perception and lower levels of Open-mindedness, and on the other associated with the Morality-as-Cooperation, Trait Optimism and Trait Self-control dimensions. Such an affective ratio in behavior has been interpreted as a moral dilemma state by researchers [

27,

36]. This condition resembles a value conflict in following policies that people distrust but are able to co-relate ethically. These constructs are related to cooperativeness, self-directedness, and self-transcendence as adaptive personality traits in the psychobiological model [

30,

38].

Multivariate regressions confirmed the two distinct patterns of support and non-support. All PHS dimensions were consistently and negatively predicted by Conspiracy Theories beliefs. Collective Narcissism, Moral Identity, and Psychological Well-Being were consistent predictors of PHS dimensions. These findings are a marker of affective polarization. They can also be seen as socio-cognitive polarization, as was described in a recent study [

10]. The data was generated at the time of the first lockdown, when people were confined to their homes. It was a collective phase of anxiety and resistance. Inhibited psychosocial functioning was transformed into affective and adaptive behaviors. Relations were overloaded by virtual communications, and analysts of psychological effects of the pandemic used concepts such as cognitive invasion, cognitive acceleration, and sensory deprivation [

39]. In all prediction models, women were associated significantly higher support scores.

The second trend of public health support was significantly associated with Open-mindedness, Moral Identity, and Risk Perception. The compliance with physical hygiene correlated positively with Collective Narcissism, Morality-as-Cooperation, Trait Optimism, Trait Self-Control, and Social Belonging. Establishment of these dependencies may be related to rational behavior of acceptance and awareness to the realities of the pandemic. Moreover, they are indicative of value-oriented behavior [

28,

29].

A particularly important finding was the significant association between Psychological Well-being, avoidance of Physical Contact and Anti-Corona Policy Support. Well-being is implicit characteristic of human functioning. Subjective well-being reflects cognitive and emotional aspects of the experience of individual life circumstances [

25]. In other words, the affective reprocessing of human experience is a phenomenon of psychological well-being. Personality profiles in terms of Robert Cloninger's model are considered to be among the most consistent predictors of well-being because they specify the synergistic nonlinear relations between emotion and cognition. For instance, combination of high Self-directedness, Cooperativeness, and Self-transcendence (the three TCI character dimensions) predicts greater physical, mental, and social well-being than any other profile or trait [

40].

Previous studies have researched a more in-depth interpretation of subjective well-being a model of affective profiles [

41,

42]. Four affective profiles have been defined: individuals who are self-fulfilling (high positive affect, low negative affect), individuals who are high affective (high positive affect, high negative affect), individuals who are low affective (low positive affect, low negative affect), and individuals who are self-destructive (low positive affect, high negative affect). Various results have been reported based on that profiling, e.g., that individuals with self-fulfilling and high affective profiles perform best during stressful situations and demonstrate a more dynamic lifestyle than low affective and self-destructive individuals. Self-fulfilling individuals also believe that they are more energetic and optimistic and indicate greater life satisfaction and psychological well-being compared individuals with the other affective profiles. Individuals with self-fulfilling profiles are characterized by high self-esteem, high optimism, and an internal locus of control, whereas for individuals with self-destructive profiles are inherent by low self-esteem, low optimism, and an external locus of control. There is evidence that self-destructive and high affective profiles are more strongly associated with more severe post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in Dutch victims of violence, as well as evidence from cross-cultural comparative studies that report differences in life satisfaction and psychological well-being [

41,

42,

43,

44]. Although the research methodology does not capture the structure of well-being in this study, the correlations between psychological well-being, contact avoidance and agreement with anticorona policies can be interpreted as evidence of an affective mode of adaptive functioning.

The time of conducting the research precedes the first epidemiological wave of illness from coronavirus in Bulgaria [

45]. It was the period of the first long-term total lockdown in Bulgaria, when socio-economic life was reduced to distance education and work. People were facing a looming economic collapse and potential job loss, stress and anxiety levels were very higher [

46,

47]. The adaptation to an unpredictable duration of the pandemic was in a process of active psychologization. We argue that trends of support and non-support can be seen phenomenologically as processes of precarity and non-precarity in pandemic realities. Conspiracy mentality is motivated by basic sense of distrust and ontological uncertainty [

3,

4,

5], and the recent pandemic created events and psychosocial contexts that activated existential emotions in people. Our results align with an affective framework of adaptation expressed in support and non-support of public health and those should be observed seriously in the action plan protocols as a major resource to foster cooperativeness and resilience by avoiding aggressive and self-contradictory measures and by means of increased awareness and respect of the health attitudes in a specific population.

Our results can inform and motivate more careful, consistent with the attitudes and evidence-based decision-making under the conditions of a similar public health crisis to limit the collateral damages of the pandemic both in terms of economic burden and increased anxiety and worries on the population level [

39,

48].

5. Conclusions

This study revealed two polar trends in the public health behavior response of Bulgarians during the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis. The tendency not to support public health was significantly predicted by the presence of beliefs in Conspiracy Theories. The trend of public health support, was significantly associated with Open-mindedness, Moral Identity, and Risk Perception. Those results outline a values-based profile of the initial response to the critical situation in Bulgaria, which, however, was later distorted by the inconsistent health policy and decision making during the following waves of the pandemic and by the mandatory vaccination.

Limitations

Our study was not representative of the general population in terms of sex, age, ethnicity and educational structure. It was conducted before the inclusion of the (obligatory) vaccination into the public health policies to prevent the spread of COVID-19 on population level. This particular intervention in the territory of shared decision making on one hand and the privacy of the individual informed consent present a major ethical concern as determinant of the public health policy support after the first wave of the pandemic and is not considered in our design.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Descriptive statistics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.; methodology, K.S.; software, K.S. and A.D.; validation, K.S. and A.D.; formal analysis, K.S.; investigation, K.S. and D.S.; data curation, K.S. and A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S.; writing—review and editing, D.S. and A.D..; supervision, D.S.; project administration, K.S. and D.S.; funding acquisition, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Bulgarian National Science Fund under contract No. KP-06-DK1/6 from 29/03/2021 within national project: "COVID-19 HUB – Information, Innovations and Implementation of Integrative Scientific Developments”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved from Research Ethics Committee, University of Kent, United Kingdom, No. 202015872211976468 within project "International Collaboration on Social & Moral Psychology of COVID-19". The study was also approved by the Committee on Scientific Ethics of Medical University-Plovdiv with protocol No. 1/25.01.2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Research Methodology

References

- Stein, R.A.; et al. Conspiracy theories in the era of COVID-19: A tale of two pandemics. International journal of clinical practice 2021, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam-Troian, J.; et al. Of precarity and conspiracy: Introducing a socio-functional model of conspiracy beliefs. British journal of social psychology 2023, 62, 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, E.; Fritsche, I. Destined to die but not to wage war: How existential threat can contribute to escalation or de-escalation of violent intergroup conflict. American Psychologist 2013, 68, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnvall, C.; Mitzen, J. Anxiety, fear, and ontological security in world politics: thinking with and beyond Giddens. International theory 2020, 12, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, Ronald David. The divided self: An existential study in sanity and madness London. The Sciences 1960.

- Azzimonti, M.; Fernandes, M. Social media networks, fake news, and polarization. European Journal of Political Economy 2023, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacer, J.; et al. Polarization of beliefs as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Spain. PloS one 2021, 16, e0254511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, A.; Rennó, L. Brazilian response to Covid-19: polarization and conflict. COVID-19's political challenges in Latin America 2021, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dandekar, P.; Goel, A.; Lee, D.T. Biased assimilation, homophily, and the dynamics of polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 5791–5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, C.; et al. Going viral: How fear, socio-cognitive polarization and problem-solving influence fake news detection and proliferation during COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Communication 2021, 5, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, F.; Treib, O.; Eckardt, F. The virus of polarization: online debates about Covid-19 in Germany. Political Research Exchange 2023, 5, 2150087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelkel, J.G.; et al. Interventions reducing affective polarization do not necessarily improve anti-democratic attitudes. Nature human behaviour 2023, 7, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simas, E.N.; Clifford, S.; Kirkland, J.H. How empathic concern fuels political polarization. American Political Science Review 2020, 114, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowes, S.M.; et al. Intellectual humility and between-party animus: Implications for affective polarization in two community samples. Journal of Research in Personality 2020, 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, N.; Lelkes, Y. The nature of affective polarization: Disentangling policy disagreement from partisan identity. American Journal of Political Science 2022, 66, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, K.N.; Bankert, A. The Moral Roots of Partisan Division: How Moral Conviction Heightens Affective Polarization. British Journal of Political Science 2020, 50, 621–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satherley, N.; Sibley, C.G.; Osborne, D. Identity, ideology, and personality: Examining moderators of affective polarization in New Zealand. Journal of Research in Personality 2020, 87, 103961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D. Personal identity is social identity. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 2021, 20, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWall, C.N.; et al. Belongingness as a core personality trait: How social exclusion influences social functioning and personality expression. Journal of personality 2011, 79, 1281–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusting, C.L.; Larsen, R.J. Personality and cognitive processing of affective information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 1998, 24, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Advice for the public: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Accessed March 27, 2023. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public. 27 March.

- Cloninger, C. Robert. Feeling good: the science of well-being. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Cloninger, C. Robert. Evolution of human brain functions: the functional structure of human consciousness. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2009, 43, 994–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, D.; et al. Differences in subjective well-being between individuals with distinct Joint Personality (temperament-character) networks in a Bulgarian sample. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, P.A. , Inman, R.A. and Cloninger, C.R. Disentangling the personality pathways to well-being. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternisko, A.; et al. National narcissism predicts the belief in and the dissemination of conspiracy theories during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from 56 countries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2023, 49, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkinopoulos, T.; Elbæk, C.T.; Mitkidis, P. Morality in the echo chamber: The relationship between belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories and public health support and the mediating role of moral identity and morality-as-cooperation across 67 countries. Plos one 2022, 17, e0273172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, D.; et al. Well-being and moral identity. PsyCh journal 2018, 7, 53–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlović, T.; et al. Predicting attitudinal and behavioral responses to COVID-19 pandemic using machine learning. PNAS nexus 2022, 1, pgac093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, D.; et al. Affectivity in Bulgaria: Differences in Life Satisfaction, Temperament, and Character." The Affective Profiles Model: 20 Years of Research and Beyond. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2023): 127-143.

- Stoyanov, Drozdstoy, et al. International perspectives in values-based mental health practice: Case studies and commentaries. Springer Nature (2021): 436.

- Azevedo, Flavio, Tomislav Pavlović, Gabriel G. d. Rêgo, F. C. Ay, Biljana Gjoneska, Tom Etienne, Robert M. Ross, et al. 2022. Social and moral psychology of COVID-19 across 69 countries. PsyArXiv. Accessed March 27, 2023. [CrossRef]

- ICSMP. An International Collaboration on the Social & Moral Psychology of COVID-19. Home page. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://icsmp-covid19.netlify.app/index.html.

- Briggs, S.R.; Cheek, J.M. The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. Journal of Personality 1986, 54, 106–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L. Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. Journal of personality assessment 2003, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bavel, J.J.; et al. National identity predicts public health support during a global pandemic. Nature communications 2022, 13, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, Mohsen, and Reg Dennick. "Making sense of Cronbach's alpha." International journal of medical education no. 2 (2011): 53. Accessed March 28, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4205511/. 28 March.

- Cloninger, C. Robert, et al. "Empowerment of health professionals: Promoting well-being and overcoming burn-out." Person Centered Medicine. Cham: Springer International Publishing 2023, 703-723.

- Stoyanova, K.; Stoyanov, D. A transdisciplinary dissection of the pandemic: where phenomenology meets neuroscience. Dialogues in Philosophy, Mental & Neuro Sciences 2022, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger, C.R.; Cloninger, K.M. People create health: effective health promotion is a creative process. International journal of person centered medicine 2013, 3, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, D.; Al Nima, A.; Kjell, O.N. The affective profiles, psychological well-being, and harmony: environmental mastery and self-acceptance predict the sense of a harmonious life. PeerJ 2014, 2, e259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; et al. Differences between affective profiles in temperament and character in Salvadorians: the self–fulfilling experience as a function of agentic (self–directedness) and communal (cooperativeness) values. International Journal of Happiness and Development 2015, 2, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Bucci, O. Affective profiles in Italian high school students: life satisfaction, psychological well-being, self-esteem, and optimism. Frontiers in psychology 2015, 6, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, D.; Moradi, S. The affective temperaments and well-being: Swedish and Iranian adolescents’ life satisfaction and psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies 2013, 14, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Infectious and Parasitic Diseases. Home page. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://covid19.ncipd.org/. 20 April.

- Backhaus, I.; et al. Resilience and coping with COVID-19: the COPERS study. International journal of public health 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarkov, Z.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of citizens of the republic of Bulgaria. Bulgarian Journal of Public Health 2022, 14, 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanov, D.; Stoyanova, K. Commentary: Coronavirus Disease 2019 Worry and Related Factors: Turkish Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Worry Scale. Alpha Psychiatry 2023, 24, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).