Submitted:

20 April 2023

Posted:

21 April 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

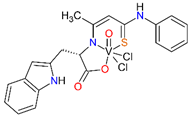

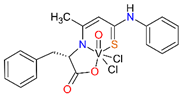

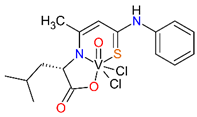

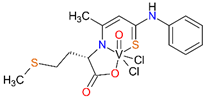

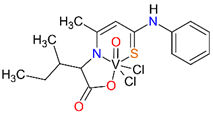

2.1. Synthesis and characteristics of the ONS and ONO complexes

2.2. The ONS complexes inhibit the activity of human tyrosine phosphatases stronger than the ONO complexes

2.3. The ONS and ONO complexes are inhibitors of non-tyrosine phosphatases

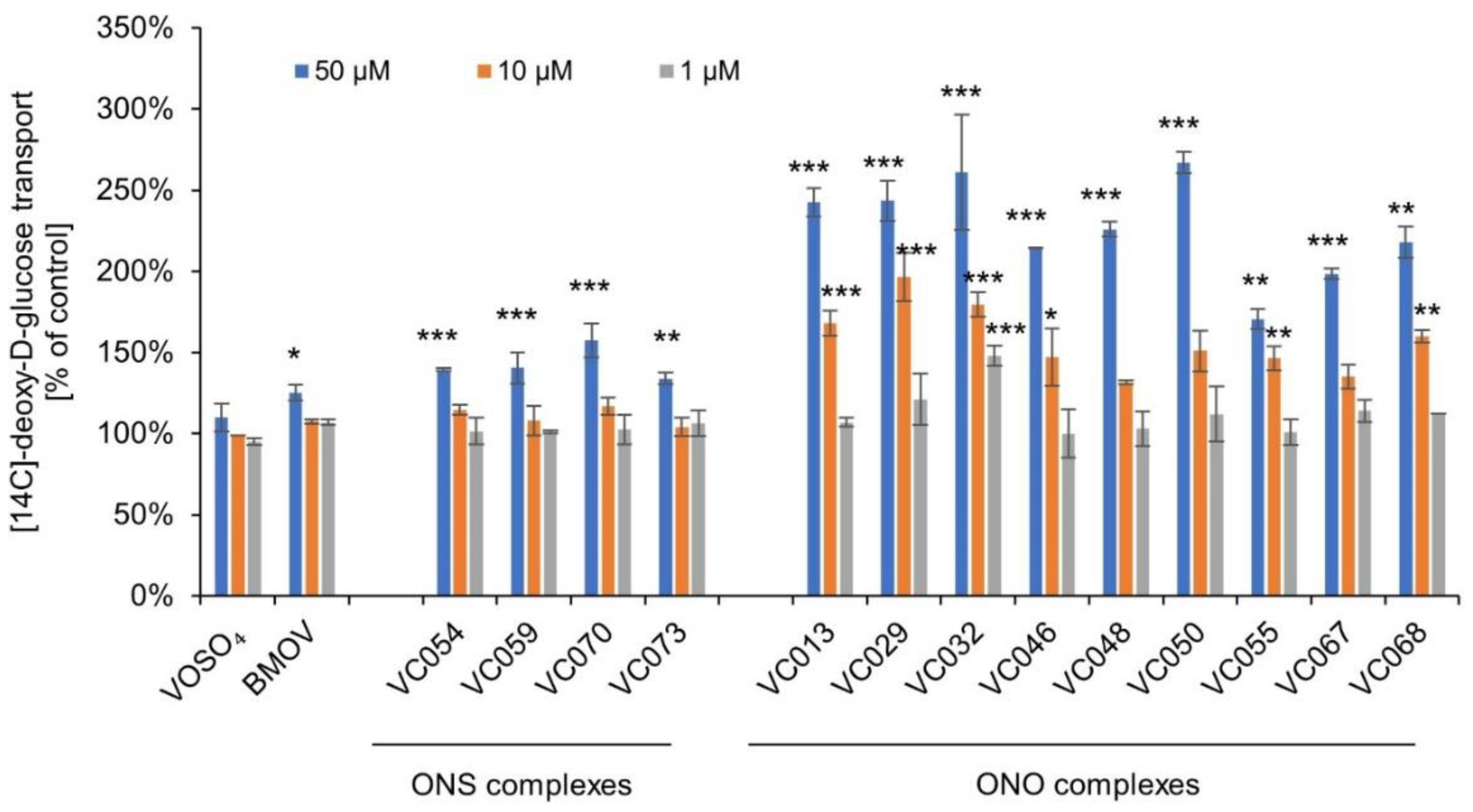

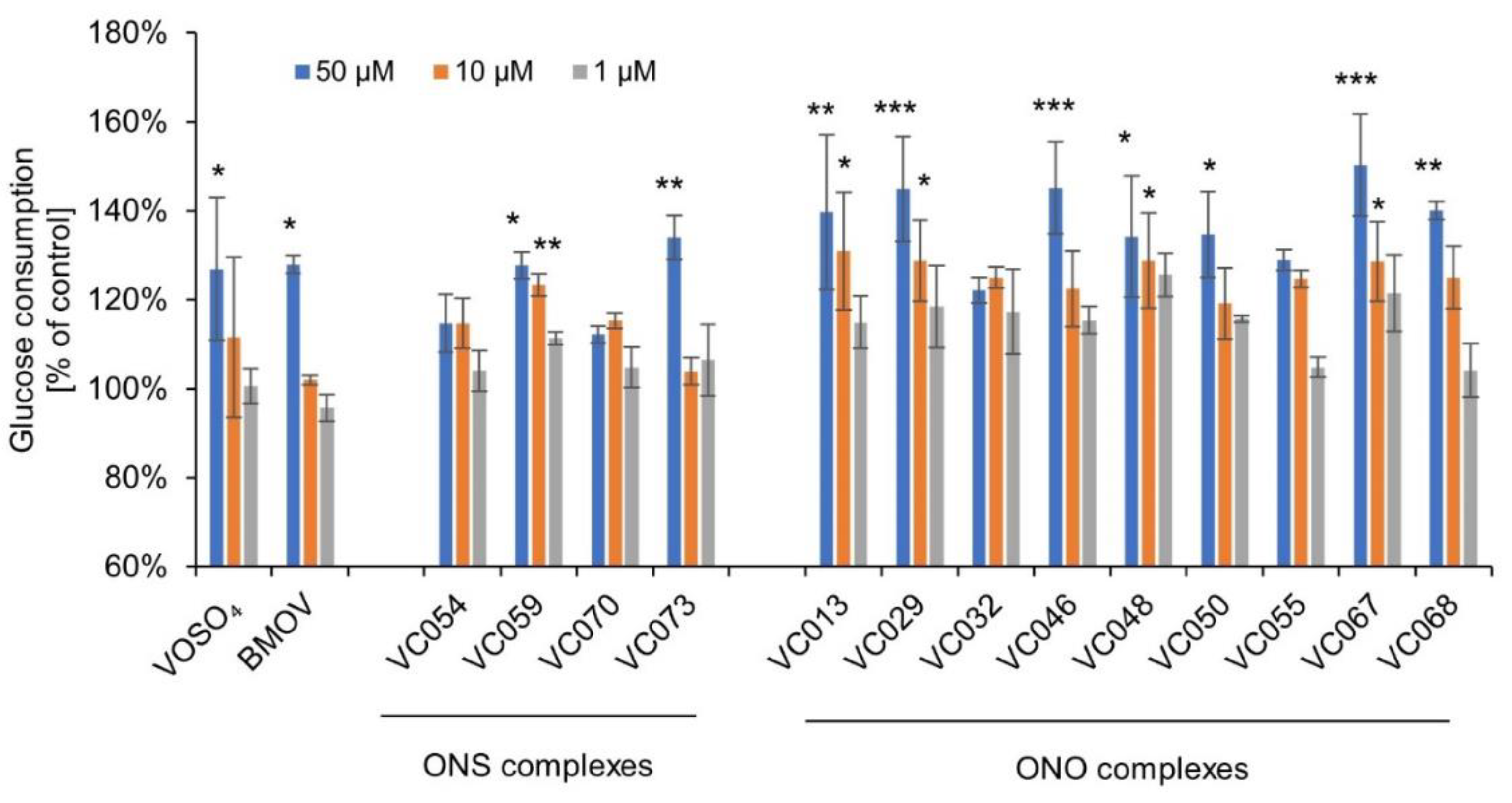

2.4. The ONS complexes enhance glucose transport into myocytes and adipocytes to a lesser extent than ONO complexes

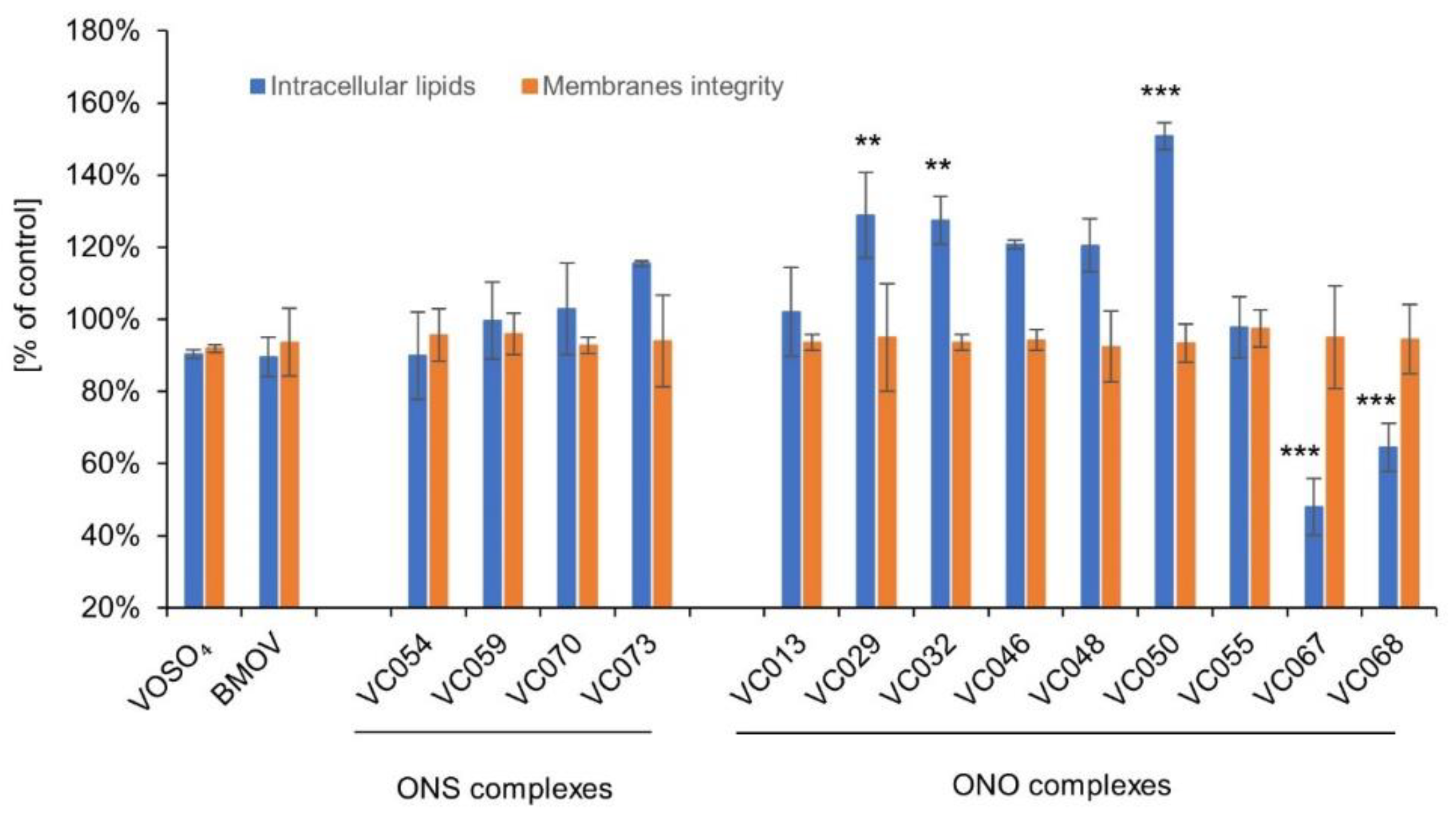

2.5. The ONO complexes but not the ONS complexes reduce hepatocyte steatosis in the cellular model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

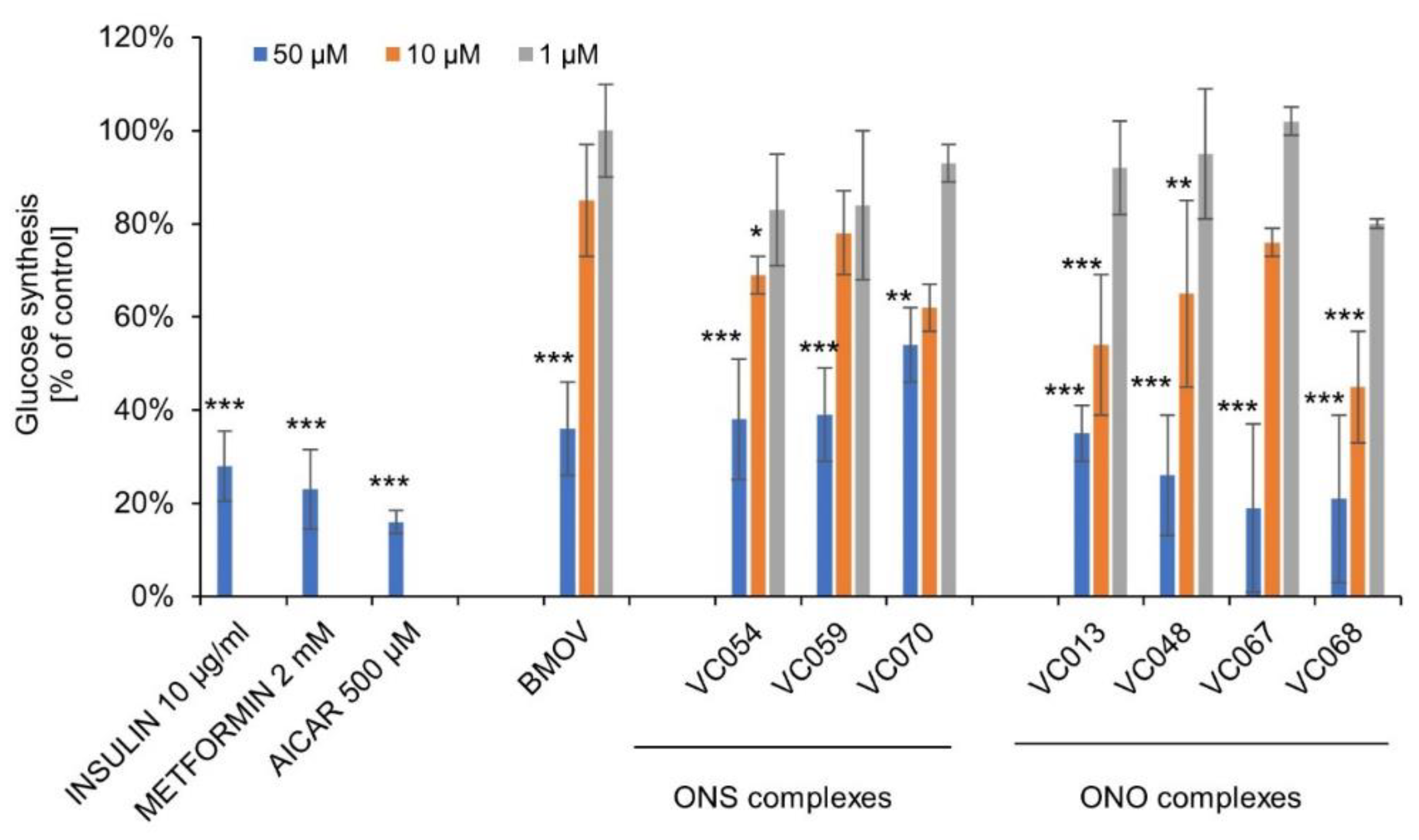

2.6. The ONS and the ONO complexes inhibit gluconeogenesis in hepatocytes

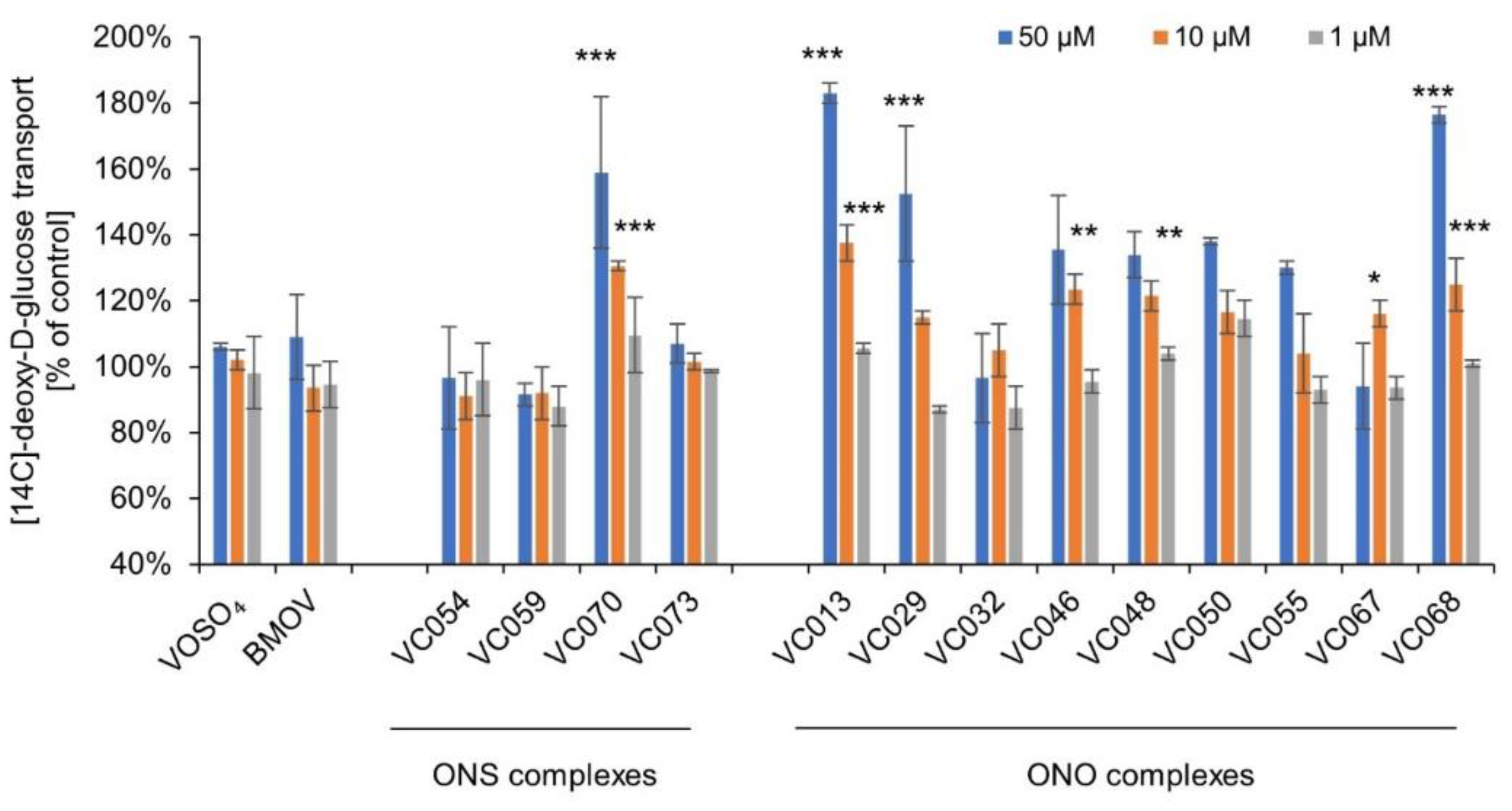

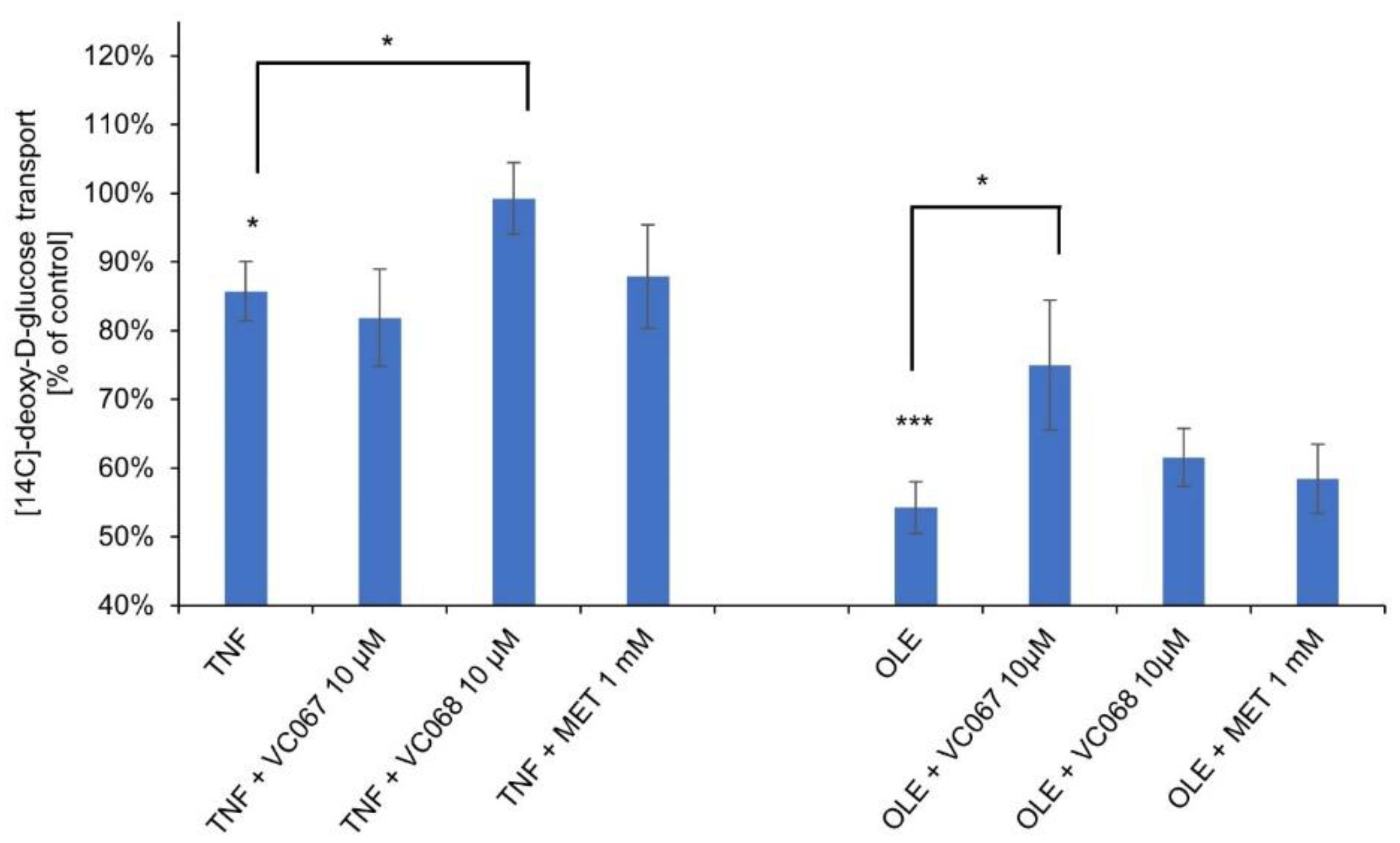

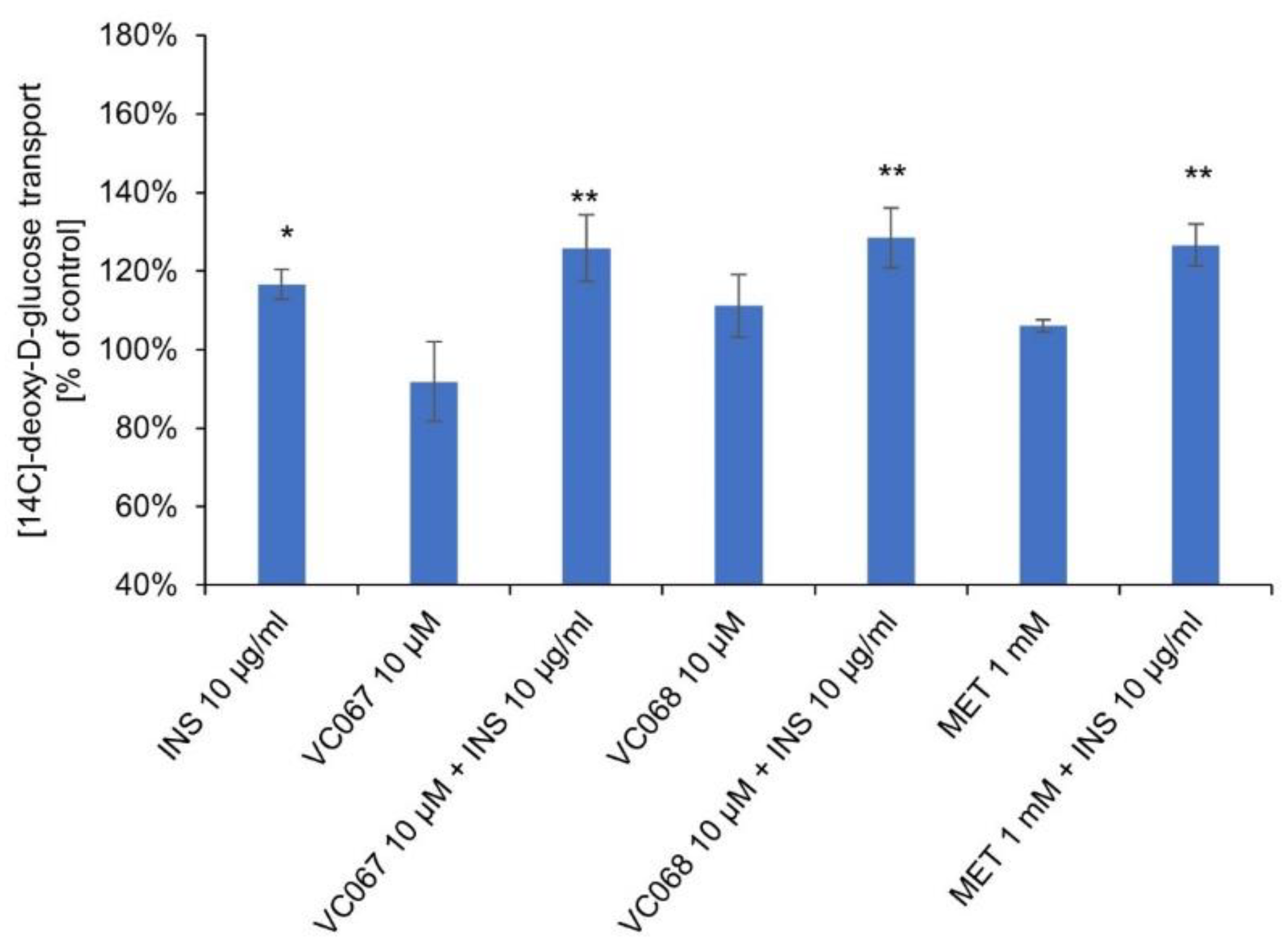

2.7. The ONO complexes reverse the impairment of glucose transport to hepatocytes under conditions of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia

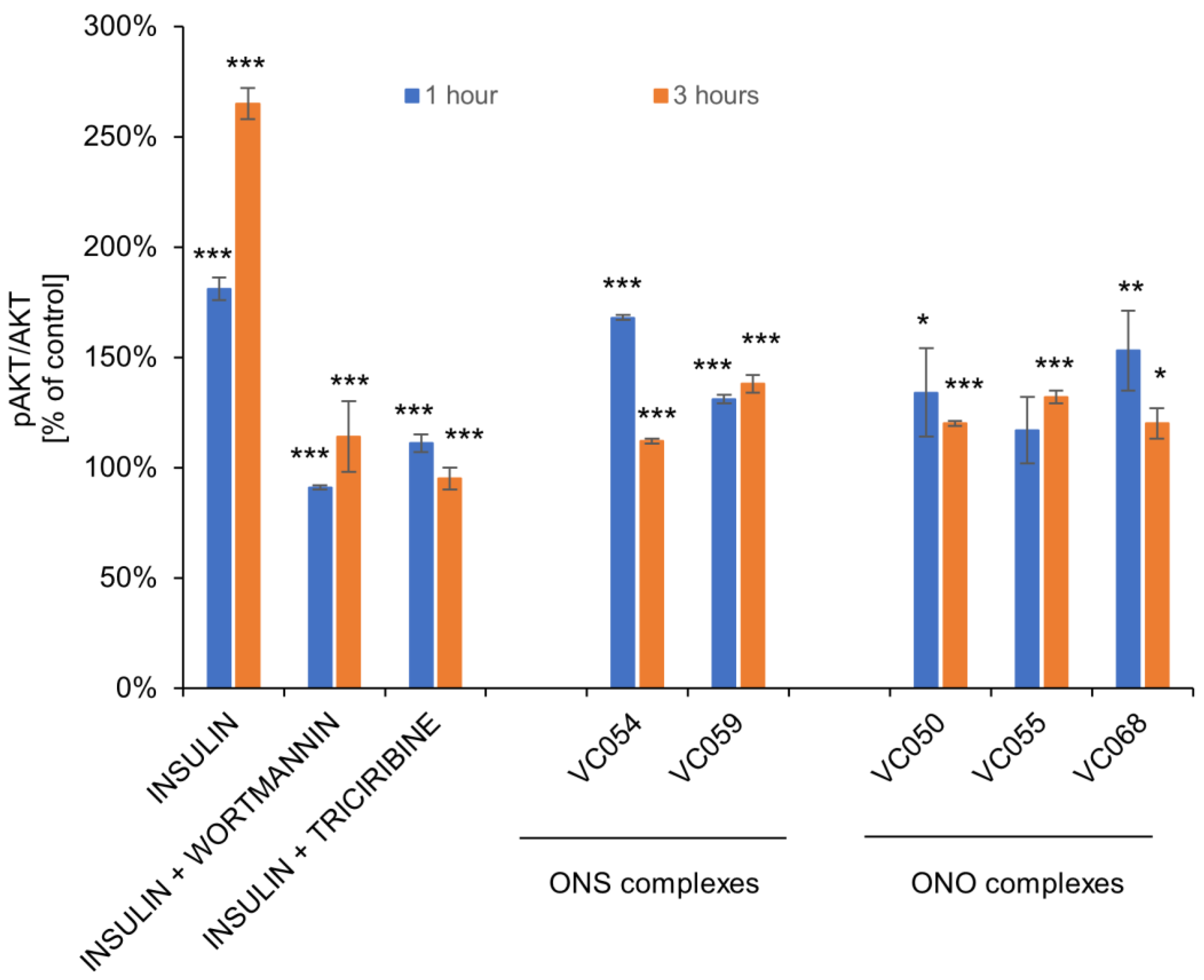

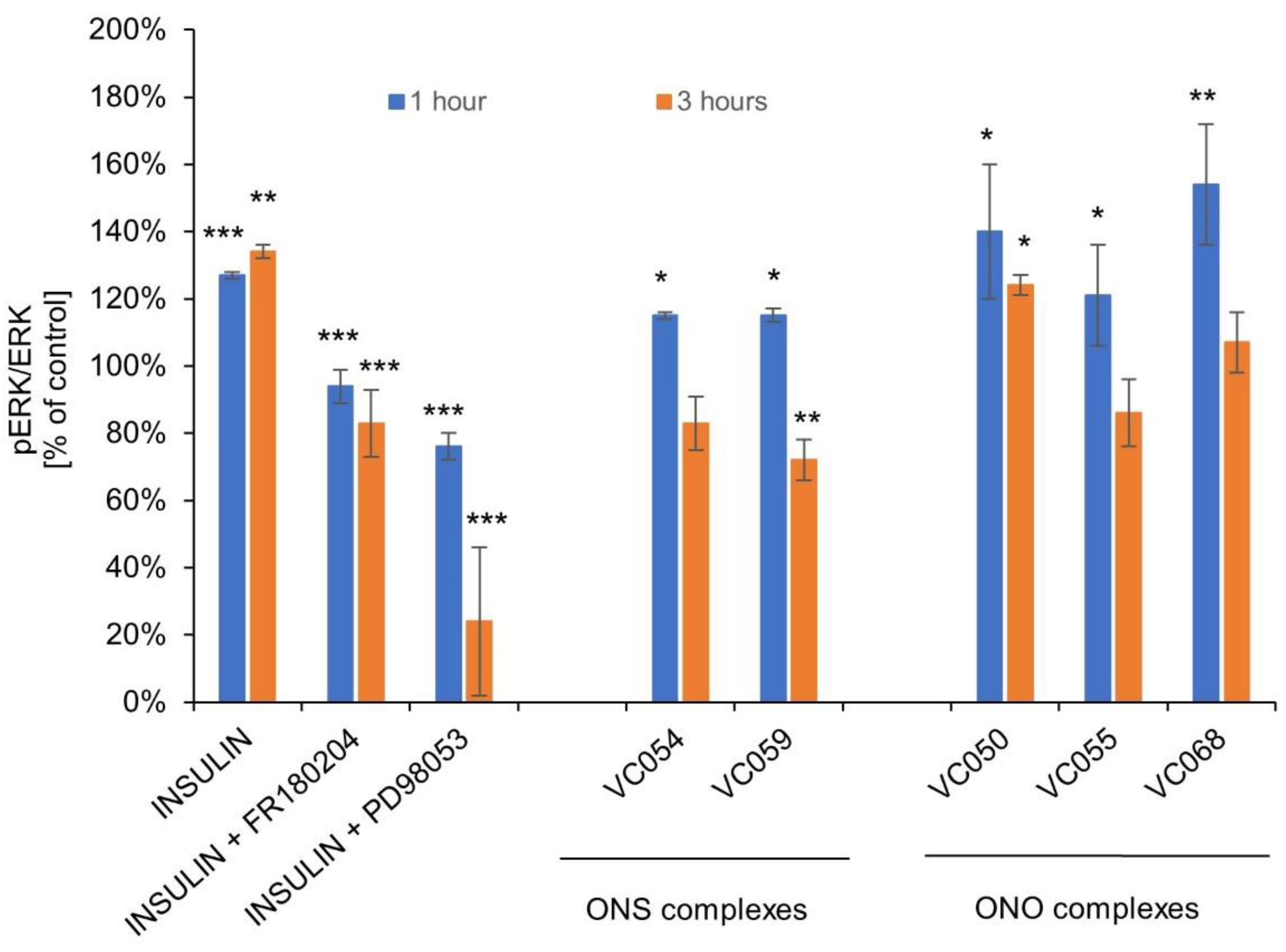

2.8. The ONS and ONO complexes activate ERK and Akt signaling pathways

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

6. Materials and Methods

4.1. Complexes synthesis and characterization

4.1.1. Materials and analytical methods

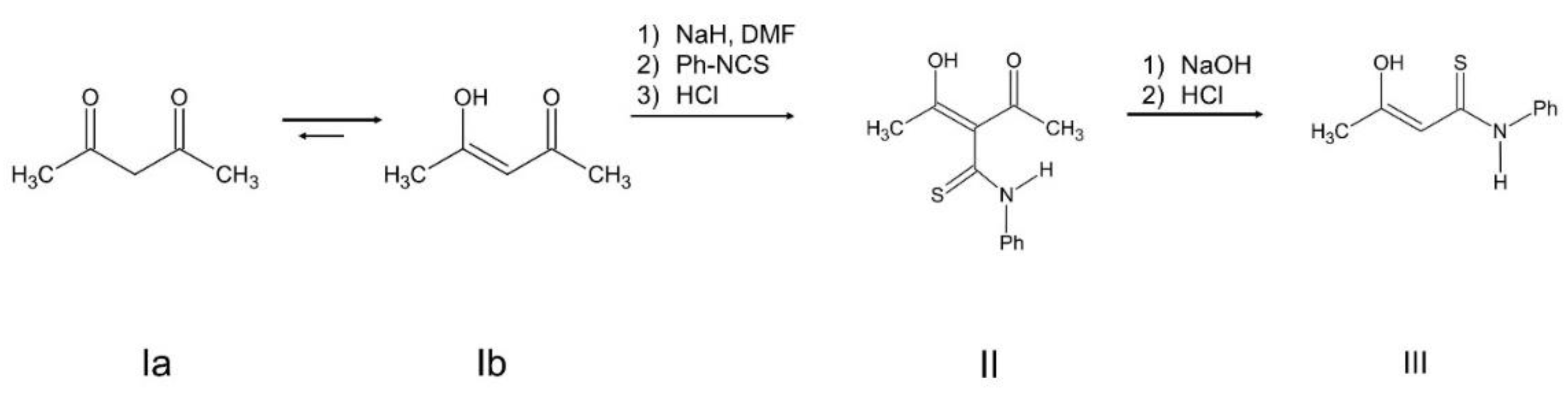

4.1.2. The synthesis of vanadium complexes with ONS Schiff base ligands

4.1.2.1. Synthesis of 3-hydroxytiocrotonic acid anilide

4.1.2.2. Condensation reaction of 3-hydroxythiocrotonic acid anilide with an amino acid salt

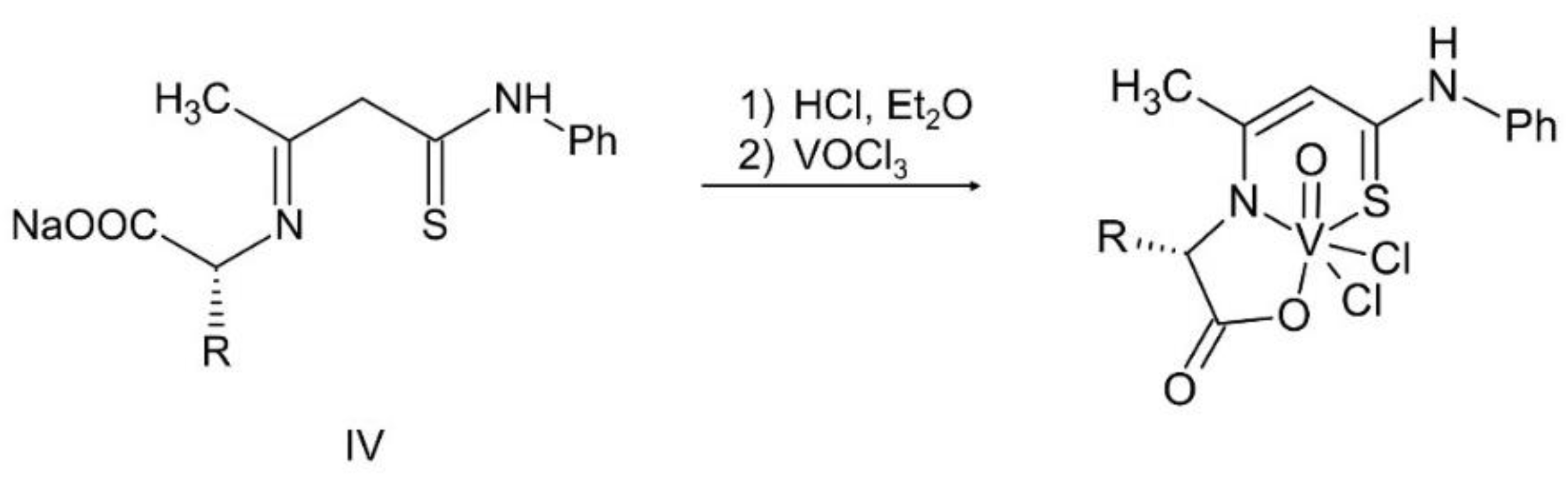

4.1.2.3. Syntheses of complexes with ONS ligands (VC054, VC059, VC070, VC073, VC109)

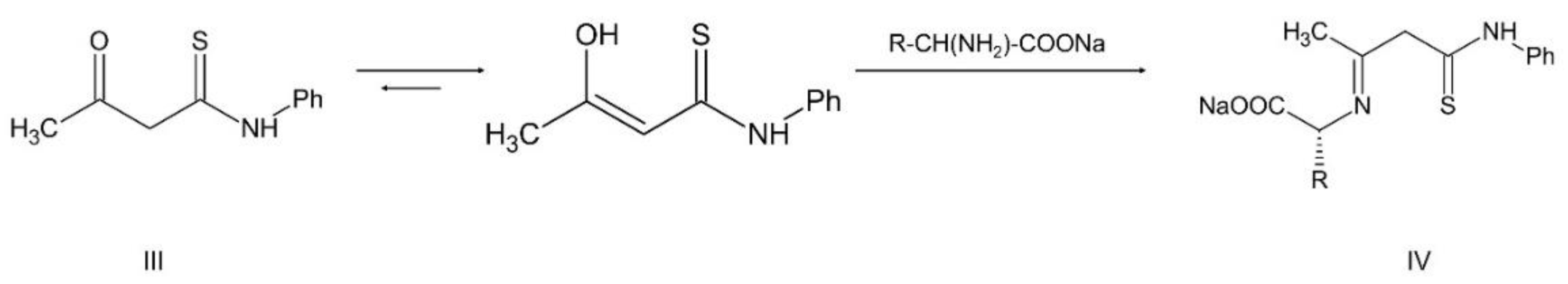

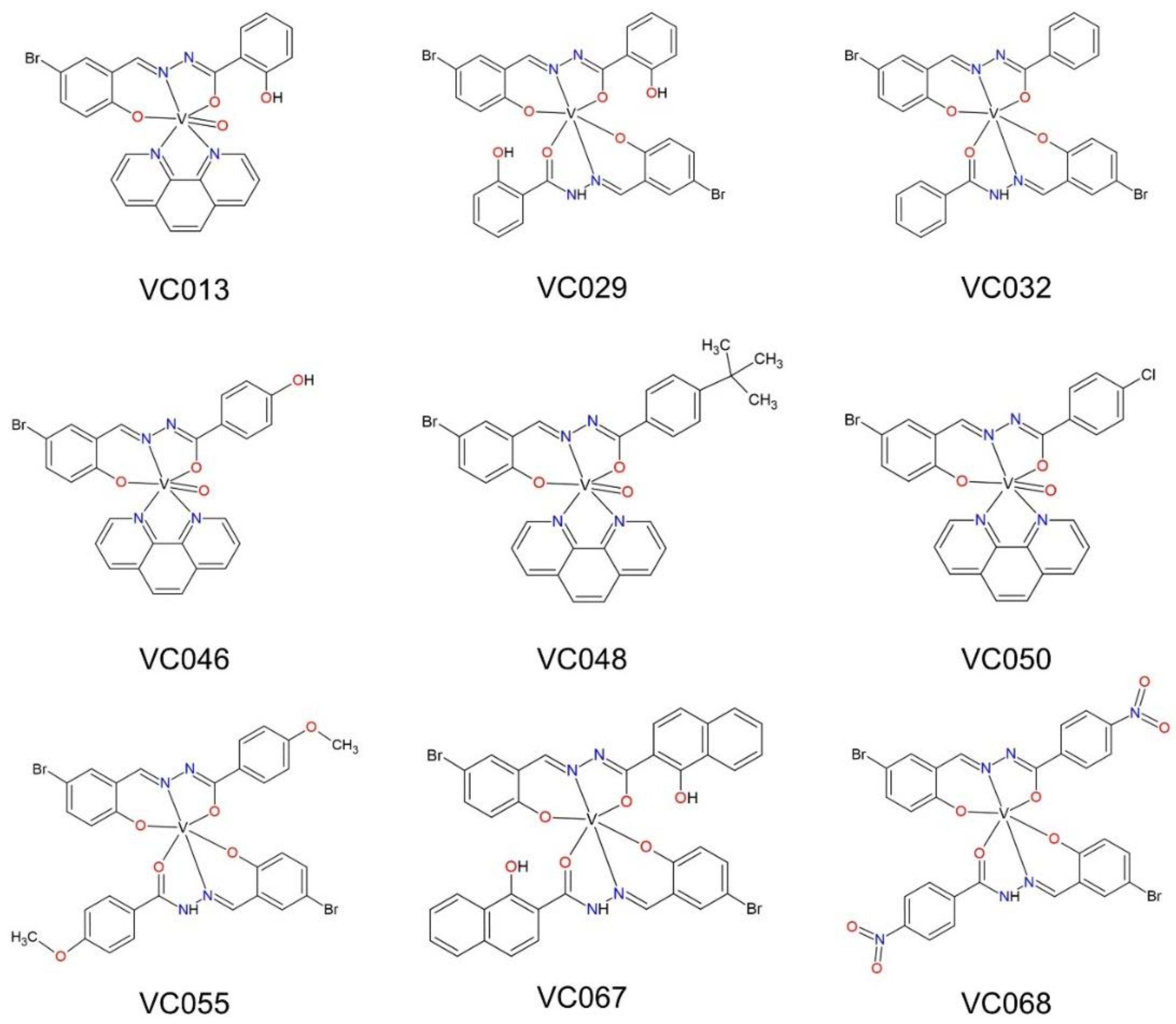

4.1.3. The synthesis of vanadium complexes with ONO Schiff base ligands

4.1.3.1. Synthesis of ONO complex [V(L13)(HL13)] (VC055)

4.2. Methods of biological assays

4.2.1. Materials

4.2.2. Inhibition of human recombinant tyrosine phosphatases

4.2.3. Inhibition of human recombinant non-tyrosine phosphatases

4.2.4. Cell models and culture conditions

4.2.5. Scintillation proximity assay for uptake of radiolabeled 2-deoxy-D-[U-14C]-glucose

4.2.6. Glucose utilization in myocytes

4.2.7. Inhibition of lipid accumulation in cell model of NAFLD

4.2.8. Inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis

4.2.9. Hyperinsulinemia condition and induction of insulin resistant hepatocytes

4.2.10. Cytotoxicity assay (cell membrane damage)

4.2.11. Homogeneous proximity-based assay for AKT and MAPK/ERK phosphorylation

4.3. Statistical methods

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; Shaw, J.E.; Bright, D.; Williams, R. IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843.

- Grundy, S.M. Pre-diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 635-43. [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.M. Prediabetes definitions and clinical outcomes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 92-93. [CrossRef]

- Yip, W.C.Y.; Sequeira, I.R.; Plank, L.D.; Poppitt, S.D. Prevalence of pre-diabetes across ethnicities: a review of impaired fasting glucose (ifg) and impaired glucose tolerance (igt) for classification of dysglycaemia. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1273. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.R.; Rosso, N.; Bedogni, G.; Tiribelli, C.; Bellentani, S. Global epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: What we need in the future. Liver Int. 2018, 38, 47-5. [CrossRef]

- Marjot, T.; Moolla, A.; Cobbold, J.F.; Hodson, L.; Tomlinson, J.W. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: current concepts in etiology, outcomes, and management. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, bnz009. [CrossRef]

- Dahlén, A.D.; Dashi, G.; Maslov, I.; Attwood, M.M.; Jonsson, J.; Trukhan, V.; Schiöth, H.B. Trends in antidiabetic drug discovery: FDA approved drugs, new drugs in clinical trials and global sales. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 807548. [CrossRef]

- Artasensi, A.; Pedretti, A.; Vistoli, G.; Fumagalli, L. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review of multi-target drugs. Molecules. 2020, 25, 1987. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.H.; Orvig, C. Vanadium in diabetes: 100 years from Phase 0 to Phase I. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006, 100, 1925-35. [CrossRef]

- Crans, D.C.; Henry, L.; Cardiff, G.; Posner, B.I. Developing vanadium as an antidiabetic or anticancer drug: A clinical and historical perspective. in: essential metals in medicine: therapeutic use and toxicity of metal ions in the clinic, Edited by Peggy L. Carver, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2019; 8, pp. 203-230. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.H.; Lichter, J.; LeBel, C.; Scaife, M.C.; McNeill, J.H.; Orvig, C. Vanadium treatment of type 2 diabetes: a view to the future. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009, 103, 554-558. [CrossRef]

- Soveid, M.; Dehghani, G.A.; Omrani, G.R. Long- term efficacy and safety of vanadium in the treatment of type 1 diabetes. Arch. Iran Med. 2013, 16, 408-411.

- Kahn, S.E.; Cooper, M.E.; Del Prato, S. Pathophysiology and treatment of type 2 diabetes: perspectives on the past, present, and future. Lancet 2014, 383, 1068-83. [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, A.; Kanwar, N.; Bharati, S.; Srivastava, P.; Singh, S.P.; Amar, S. Exploring new drug targets for type 2 diabetes: success, challenges and opportunities. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 331. [CrossRef]

- Treviño, S.; Díaz, A.; Sánchez-Lara, E.; Sanchez-Gaytan, B.L.; Perez-Aguilar, J.M.; González-Vergara, E. Vanadium in biological action: chemical, pharmacological aspects, and metabolic implications in diabetes mellitus. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 188, 68-98. [CrossRef]

- Crans, D.C.; Smee, J.J.; Gaidamauskas, E.; Yang, L. The chemistry and biochemistry of vanadium and the biological activities exerted by vanadium compounds. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 849-902. [CrossRef]

- Pendergrass, M.; Bertoldo, A.; Bonadonna, R.; Nucci, G.; Mandarino, L.; Cobelli, C.; Defronzo, R.A. Muscle glucose transport and phosphorylation in type 2 diabetic, obese nondiabetic, and genetically predisposed individuals. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 292, E92-E100. [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Gunnarsson, R.; Björkman, O.; Olsson, M.; Wahren, J. Effects of insulin on peripheral and splanchnic glucose metabolism in noninsulin-dependent (type II) diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Invest. 1985, 76, 149-155. [CrossRef]

- Chait, A.; den Hartigh, L.J. Adipose tissue distribution, inflammation and its metabolic consequences, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 22. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, A.; Duvoor, C.; Reddy Dendi, V.S.; Kraleti, S.; Chada, A.; Ravilla, R.; Marco, A.; Shekhawat, N.S.; Montales, M. T.; Kuriakose, K.; Sasapu, A.; Beebe, A.; Patil, N.; Musham, C.K;, Lohani, G.P.; Mirza, W. Clinical review of antidiabetic drugs: implications for type 2 diabetes mellitus management. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2017, 8, 6. [CrossRef]

- Irving, E.; Stoker, A.W. Vanadium compounds as PTP Inhibitors. Molecules 2017, 22, 2269. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Théberge, J.F.; Bernier, M.; Srivastava, A.K. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase requirement in activation of the ras/C-raf-1/MEK/ERK and p70(s6k) signaling cascade by the insulinomimetic agent vanadyl sulfate. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 14667-75. [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriou, P.; Geronikaki, A.; Petrou, A. PTP1b inhibition, a promising approach for the treatment of diabetes type II. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 246-263. [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, M.Z.; Pandey, S.K.; Théberge, J.F.; Srivastava, A.K. Insulin signal mimicry as a mechanism for the insulin-like effects of vanadium. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2006, 44, 73-81. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Chiasson, J.L.; Srivastava, A.K. Vanadium salts stimulate mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases and ribosomal S6 kinases. Mol. Cell Biochem. 1995, 153, 69-78. [CrossRef]

- Neel, B.G.; Tonks, N.K. Protein tyrosine phosphatases in signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1997, 9, 193-204. [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.; Schwab, M.; Marette, A. Role of protein tyrosine phosphatases in the modulation of insulin signaling and their implication in the pathogenesis of obesity-linked insulin resistance. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2014, 15, 79-97. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhu, M. Protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibition by metals and metal complexes. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2014, 20, 2210-24. [CrossRef]

- Krüger, J.; Wellnhofer, E.; Meyborg, H.; Stawowy, P.; Östman, A.; Kintscher, U.; Kappert, K. Inhibition of Src homology 2 domain-containing phosphatase 1 increases insulin sensitivity in high-fat diet-induced insulin-resistant mice. FEBS Open Bio. 2016, 6, 179-89. [CrossRef]

- Sevillano, J.; Sánchez-Alonso, M.G.; Pizarro-Delgado, J.; Ramos-Álvarez, M.D.P. Role of receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases (RPTPs) in insulin signaling and secretion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5812. [CrossRef]

- Morioka, M.; Fukunaga, K.; Kawano, T.; Hasegawa, S.; Korematsu, K.; Kai, Y.; Hamada, J.; Miyamoto, E.; Ushio, Y. Serine/threonine phosphatase activity of calcineurin is inhibited by sodium orthovanadate and dithiothreitol reverses the inhibitory effect. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 253, 342-5. [CrossRef]

- Semiz, S.; McNeill, J.H. Oral treatment with vanadium of Zucker fatty rats activates muscle glycogen synthesis and insulin-stimulated protein phosphatase-1 activity. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2002, 236, 123-31. [CrossRef]

- Honkanen, R.E.; Golden, T. Regulators of serine/threonine protein phosphatases at the dawn of a clinical era?. Curr. Med. Chem. 2002, 9, 2055-2075. [CrossRef]

- Copps, K.D.; White, M.F. Regulation of insulin sensitivity by serine/threonine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate proteins IRS1 and IRS2. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 2565-2582. [CrossRef]

- Scrivens, P.J.; Alaoui-Jamali, M.A.; Giannini, G.; Wang, T.; Loignon, M.; Batist, G.; Sandor, V.A. Cdc25A-inhibitory properties and antineoplastic activity of bisperoxovanadium analogues. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2003, 2, 1053-9. PMID: 14578470.

- Liu, K.; Zheng, M.; Lu, R.; Du, J.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. The role of CDC25C in cell cycle regulation and clinical cancer therapy: a systematic review. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 213. [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, J.C.; Etcheverry, S.; Gambino, D. Vanadium compounds in medicine. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 301, 24-48. [CrossRef]

- Crans, D.C.; Yang, L.; Haase, A.; Yang, X. "Health benefits of vanadium and its potential as an anticancer agent". In: Metallo-drugs: Development and action of anticancer agents, Edited by Astrid Sigel, Helmut Sigel, Eva Freisinger and Roland K.O. Sigel, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2018; 9, pp. 251-280. [CrossRef]

- Crans, D.C.; Meade, T.J. Preface for the forum on metals in medicine and health: new opportunities and approaches to improving health. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 12181-12183. [CrossRef]

- Scior, T.; Guevara-García, A.; Bernard, P.; Do, Q.T.; Domeyer, D.; Laufer, S. Are vanadium compounds drugable? Structures and effects of antidiabetic vanadium compounds: a critical review. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2005, 5, 995-1008. [CrossRef]

- Scior, T.; Guevara-Garcia, J.A.; Do, Q.T.; Bernard, P.; Laufer, S. Why antidiabetic vanadium complexes are not in the pipeline of "Big Pharma" drug research? A critical review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 2874-2891. [CrossRef]

- Gryboś, R.; Paciorek, P.; Szklarzewicz, J.; Matoga, D.; Zabierowski, P.; Kazek, G. Novel vanadyl complexes of acetoacetanilide: Synthesis, characterization and inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase. Polyhedron 2013, 49, 100–104.

- Zabierowski, P.; Szklarzewicz, J.; Gryboś, R.; Mordyl, B.; Nitek, W. Assemblies of salen-type oxidovanadium(IV) complexes: substituent effects and in vitro protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibition. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 17044-17053. [CrossRef]

- Szklarzewicz, J.; Jurowska, A.; Hodorowicz, M.; Gryboś, R.; Matoga, D. Role of co-ligand and solvent on properties of V(IV) oxido complexes with ONO Schiff bases. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1180, 839–848.

- Gryboś, R.; Szklarzewicz, J.; Jurowska, A.; Hodorowicz, M. Properties, structure and stability of V(IV) hydrazide Schiff base ligand complex. J. Mol. Struct. 2018; 1171: 880–887.

- Szklarzewicz, J.; Jurowska, A.; Matoga, D.; Kruczała, K.; Kazek, G.; Mordyl, B.; Sapa, J.; Papież, M. Synthesis, coordination properties and biological activity of vanadium complexes with hydrazone Schiff base ligands. Polyhedron 2020, 185, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Szklarzewicz, A.; Jurowska, M.; Hodorowicz, M.; Gryboś, R.; Kruczała, K.; Głuch-Lutwin, M.; Kazek, G. Vanadium complexes with salicylaldehyde-based Schiff base ligands-structure, properties and biological activity. J. Coord. Chem. 2020, 73, 986-1008. [CrossRef]

- Szklarzewicz, J.; Jurowska, A.; Hodorowicz, M.; Kazek, G.; Głuch-Lutwin, M.; Sapa, J. Ligand role on insulin-mimetic properties of vanadium complexes. Structural and biological studies. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 516, 120135. [CrossRef]

- Szklarzewicz, J.; Jurowska, A.; Hodorowicz, M.; Kazek, G.; Mordyl, B.; Menaszek, E.; Sapa, J. Characterization and antidiabetic activity of salicylhydrazone Schiff base vanadium(IV) and (V) complexes. Transit. Met. Chem. 2021, 46, 201–217. [CrossRef]

- Jurowska, A.; Serafin, W.; Hodorowicz, M.; Kruczała, K.; Szklarzewicz, J. Vanadium precursors and the type of complexes formed with Schiff base ligand composed of 5-bromosalicylaldehyde and 2-hydroxybenzhydrazide—Structure and characterization. Polyhedron 2022, 222, 115903.

- Jasińska, A.; Szklarzewicz, J.; Jurowska, A.; Hodorowicz, M.; Kazek, G.; Mordyl, B.; Głuch-Lutwin, M. V(III) and V(IV) Schiff base complexes as potential insulin-mimetic compounds—Comparison, characterization and biological activity. Polyhedron 2022, 215, 115682.

- Gryboś, R.; Szklarzewicz, J.; Matoga, D.; Kazek, G.; Stępniewski, M.; Krośniak, M.; Nowak, G.; Paciorek, P.; Zabierowski, P. Vanadium complexes with hydrazide-hydrazones, process for their preparation, pharmaceutical formulations and the use of thereof. World Patent No. WO2014073992A1. May 15, 2014.

- Gryboś, R.; Szklarzewicz, J.; Matoga, D.; Kazek, G.; Stępniewski, M.; Krośniak, M.; Nowak, G.; Paciorek, P.; Zabierowski, P. Vanadium complexes with hydrazide-hydrazones, process for their preparation, pharmaceutical formulations and their use. PL Patent No. PL231079B1. November 07, 2012.

- Kazek, G.; Głuch-Lutwin, M.; Mordyl, B.; Menaszek, E.; Szklarzewicz, J.; Gryboś, R.; Papież, M. Cell-based screening for identification of novel vanadium complexes with multidirectional activity relative to cells associated with metabolic disorders. ST&I 2019, 4, 47–54. [CrossRef]

- Kazek, G.; Głuch-Lutwin, M.; Mordyl, B.; Menaszek, E.; Sapa, J.; Szklarzewicz, J.; Gryboś, R.; Papież, M. Potentiation of adipogenesis and insulinomimetic effects of novel vanadium complex (N'-[(E)-(5-bromo-2-oxophenyl)methylidene]-4-methoxybenzohydrazide)oxido(1,10-phenanthroline)vanadium(IV) in 3T3-L1 cells. ST&I 2019, 1, 55-62. [CrossRef]

- ISO 10993-5:2009 Biological evaluation of medical devices. Part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2009.

- Dash, A.; Figler, R.A.; Sanyal, A.J.; Wamhoff, B.R. Drug-induced steatohepatitis. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2017, 13, 193-204. [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.G.; Davis, M.G.; Howard, B.W.; Pokross, M.; Rastogi, V.; Diven, C.; Greis, K.D.; Eby-Wilkens, E.; Maier, M.; Evdokimov, A.; Soper, S.; Genbauffe, F. Mechanism of insulin sensitization by BMOV (bis maltolato oxo vanadium); unliganded vanadium (VO4) as the active component. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2003, 96, 321-30. [CrossRef]

- Cuncic, C.; Detich, N.; Ethier, D.; Tracey, A.S.; Gresser, M.J.; Ramachandran, C. Vanadate inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatases in Jurkat cells: modulation by redox state. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 4, 354-359. [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lu, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, M.; Yuan, C.; Xing, S.; Fu, X. Synthesis and evaluation of oxovanadium(IV) complexes of Schiff-base condensates from 5-substituted-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde and 2-substituted-benzenamine as selective inhibitors of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 11116-11124. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Gao, X.; Zhu, M.; Wang, S.; Wu, Q.; Xing, S.; Fu, X.; Liu, Z.; Guo, M. Exploration of biguanido-oxovanadium complexes as potent and selective inhibitors of protein tyrosine phosphatases. Biometals 2012, 25, 599-610. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Wang, S.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Z.; Guo, M.; Xing, S.; Fu, X. Inhibition protein tyrosine phosphatases by an oxovanadium glutamate complex, Na2[VO(Glu)2(CH3OH)](Glu = glutamate). Biometals 2010, 23, 1139-1147. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Lu, L.; Gao, X.; Wu, Y.; Guo, M.; Li, Y.; Fu, X.; Zhu, M. Ternary oxovanadium(IV) complexes of ONO-donor Schiff base and polypyridyl derivatives as protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors: synthesis, characterization, and biological activities. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 14, 841-851. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.J.; Bergeron, S.; Kim, H.J.; Dombrowski, L.; Perreault, M.; Fournès, B.; Faure, R.; Olivier, M.; Beauchemin, N.; Shulman, G.I.; Siminovitch, K.A.; Kim, J.K.; Marette, A. The SHP-1 protein tyrosine phosphatase negatively modulates glucose homeostasis. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 549-56. [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, S.; Dubois, M.J.; Bellmann, K.; Schwab, M.; Larochelle, N.; Nalbantoglu, J.; Marette, A. Inhibition of the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 increases glucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells by augmenting insulin receptor signaling and GLUT4 expression. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 4581-8. [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.; Charbonneau, A.; Rolland, Y.; Bellmann, K.; Pao, L.; Siminovitch, K. A.; Neel, B.G.; Beauchemin, N.; Marette, A. Hepatocyte-specific Ptpn6 deletion protects from obesity-linked hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes 2012, 61, 1949-1958. [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.K. The SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase: signaling mechanisms and biological functions. Cell. Res. 2000, 10, 279-88. [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Han, T.; Hao, W.; Wang, M.; Fu, Y. SHP2 knockdown ameliorates liver insulin resistance by activating IRS-2 phosphorylation through the AKT and ERK1/2 signaling pathways. FEBS Open Bio 2020, 10, 2578-2587. [CrossRef]

- Nagata, N.; Matsuo, K.; Bettaieb, A.; Bakke, J.; Matsuo, I.; Graham, J.; Xi, Y.; Liu, S.; Tomilov, A.; Tomilova, N.; Gray, S.; Jung, D.Y.; Ramsey, J.J.; Kim, J.K.; Cortopassi, G.; Havel, P.J.; Haj, F.G. Hepatic Src homology phosphatase 2 regulates energy balance in mice. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3158-3169. [CrossRef]

- Kulas, D.T.; Zhang, W.R.; Goldstein, B.J.; Furlanetto, R.W.; Mooney, R.A. Insulin receptor signaling is augmented by antisense inhibition of the protein tyrosine phosphatase LAR. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 2435-8.

- Zabolotny, J.M.; Kim, Y.B.; Peroni, O.D.; Kim, J.K.; Pani, M.A.; Boss, O.; Klaman, L.D.; Kamatkar, S.; Shulman, G.I.; Kahn, B.B.; Neel, B.G. Overexpression of the LAR (leukocyte antigen-related) protein-tyrosine phosphatase in muscle causes insulin resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 5187-92. [CrossRef]

- Mooney, R.A.; LeVea, C.M. The leukocyte common antigen-related protein LAR: candidate PTP for inhibitory targeting. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2003, 3, 809-19. [CrossRef]

- Gundhla, I.Z.; Walmsley, R.S.; Ugirinema, V.; Mnonopi, N. O.; Hosten, E.; Betz, R.; Frost, C. L.; Tshentu, Z. R.pH-metric chemical speciation modeling and studies of in vitro antidiabetic effects of bis[(imidazolyl)carboxylato]oxidovanadium(IV) complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2015, 145, 11-18. [CrossRef]

- Huyer, G.; Liu, S.; Kelly, J.; Moffat, J.; Payette, P.; Kennedy, B.; Tsaprailis, G.; Gresser, M.J.; Ramachandran, C. Mechanism of inhibition of protein-tyrosine phosphatases by vanadate and pervanadate. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 843-51. [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.S.; Ryu, J.M.; Park, S.M.; Park, J.H.; Lee, H.C.; Hwang, K.Y.; Kim, J. Structural basis for inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatases by Keggin compounds phosphomolybdate and phosphotungstate. Exp. Mol. Med. 2002, 34, 211-23. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, F.; Huang, C.; Shi, X. Vanadate induces G2/M phase arrest in p53-deficient mouse embryo fibroblasts. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2002, 21, 223-231.

- Liu, T.T.; Liu, Y.J.; Wang, Q.; Yang, X.G.; Wang, K. Reactive-oxygen-species-mediated Cdc25C degradation results in differential antiproliferative activities of vanadate, tungstate, and molybdate in the PC-3 human prostate cancer cell line. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 17, 311-20. [CrossRef]

- Ajeawung, N.F.; Faure, R.; Jones, C.; Kamnasaran, D. Preclinical evaluation of dipotassium bisperoxo (picolinato) oxovanadate V for the treatment of pediatric low-grade gliomas. Future Oncol. 2013, 9, 1215-29. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, G.; Gogoi, S.R.; Boruah, J.; Ram, B.; Begum, P.; Ahmed, K.; Sharma, M.; Ramakrishna, G.; Ramasarma, T.; Islam, N.S. Peroxo compounds of Vanadium(V) and Niobium(V) as potent inhibitors of calcineurin activity towards RII-Phosphopeptide. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 5838-5848. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Tracey, A.S. Vanadium(V) complexes in enzyme systems: aqueous chemistry, inhibition and molecular modeling in inhibitor design. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2001, 85, 9-13. [CrossRef]

- Blau, H.M.; Chiu, C.P.; Webster, C. Cytoplasmic activation of human nuclear genes in stable heterocaryons. Cell 1983, 32, 1171-1180. [CrossRef]

- Mangnall, D.; Bruce, C.; Fraser, R.B. Insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in C2C12 myoblasts. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1993, 21, 438S. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.Y.; Al-Salami, H.; Dass, C.R. C2C12 cell model: its role in understanding of insulin resistance at the molecular level and pharmaceutical development at the preclinical stage. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2020, 72, 1667-1693. [CrossRef]

- Shinde, U.A.; Sharma, G.; Goyal, R.K. In vitro insulin mimicking action of Bis(Maltolato) Oxovanadium (IV). Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2004, 66, 392-395.

- Lei, J.X.; Wang, J.; Huo, Y.; You, Z. 4-Fluoro-N'-(2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzylidene) benzohydrazide and its Oxidovanadium(V) complex: Syntheses, crystal structures and insulin-enhancing activity. Acta Chim. Slov. 2016, 63, 670-677. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.B.; Xie, Q.; Li, W.; Ding, Y.; Ye, Y.T. Synthesis, Crystal structures, and insulin enhancement of Vanadium(V) complexes derived from 2-Bromo-N’-(2-hydroxybenzylidene)benzohydrazide. Synth. React. Inorg. Met. Org. Chem. 2016, 46, 1613-1617. [CrossRef]

- Green, H.; Kehinde, O. Sublines of mouse 3T3 cells that accumulate lipid. Cell 1974, 3, 113-116. [CrossRef]

- Dufau, J.; Shen, J.X.; Couchet, M.; De Castro Barbosa, T.; Mejhert, N.; Massier, L.; Griseti, E.; Mouisel, E.; Amri, E.Z.; Lauschke, V.M.; Rydén, M.; Langin, D. In vitro and ex vivo models of adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C822-C841. [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A. The triumvirate: beta-cell, muscle, liver. A collusion responsible for NIDDM. Diabetes 1988, 37, 667-687. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Ghani, M.A.; DeFronzo, R.A. Pathogenesis of insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 2010, 476279. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.J.; Carvalho, E.; Eriksson, J.W.; Crans, D.C.; Aureliano, M. Effects of decavanadate and insulin enhancing vanadium compounds on glucose uptake in isolated rat adipocytes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009, 103, 1687-1692. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, W.M.; Stanhope, K.L.; Gregoire, F.; Evans, J.L.; Havel, P.J. Effects of metformin and vanadium on leptin secretion from cultured rat adipocytes. Obes. Res. 2000, 8, 530-539. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N.; Halberstam, M.; Shlimovich, P.; Chang, C.J.; Shamoon, H.; Rossetti, L. Oral vanadyl sulfate improves hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Invest. 1995, 95, 2501-2509. [CrossRef]

- Tsiani, E.; Bogdanovic, E.; Sorisky, A.; Nagy, L.; Fantus, I.G. Tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors, vanadate and pervanadate, stimulate glucose transport and GLUT translocation in muscle cells by a mechanism independent of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and protein kinase C. Diabetes 1998, 47, 1676-1686. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P.; Correia, I.; Cavaco, I.; Marques, F.; Pinheiro, T.; Avecilla, F.; Pessoa, J.C. Therapeutic potential of vanadium complexes with 1,10-phenanthroline ligands, quo vadis? Fate of complexes in cell media and cancer cells. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2021, 217, 111350. [CrossRef]

- Levina, A.; McLeod, A.I.; Pulte, A.; Aitken, J.B.; Lay, P.A. Biotransformations of antidiabetic vanadium prodrugs in mammalian cells and cell culture media: A XANES spectroscopic study. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 6707-6718.

- Rampersad, S.N. Multiple applications of Alamar Blue as an indicator of metabolic function and cellular health in cell viability bioassays. Sensors (Basel) 2012, 12, 12347-12360. [CrossRef]

- Mbatha, B., Khathi, A., Sibiya, N., Booysen, I., Ngubane, P. A Dioxidovanadium complex cis-[VO2 (obz) py] attenuates hyperglycemia in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic male sprague-dawley rats via increased GLUT4 and glycogen synthase expression in the skeletal muscle. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2022, 2022, 5372103. Published 2022 Jan 31. [CrossRef]

- Scalise, M.; Galluccio, M.; Console, L.; Pochini, L.; Indiveri, C. The human SLC7A5 (LAT1): The intriguing histidine/large neutral amino acid transporter and its relevance to human health. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 243. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Ecker, G.F. Insights into the structure, function, and ligand discovery of the large neutral amino acid transporter 1, LAT1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1278. [CrossRef]

- Klajner, M.; Licona, C.; Fetzer, L.; Hebraud, P.; Mellitzer, G.; Pfeffer, M.; Harlepp, S.; Gaiddon, C. Subcellular localization and transport kinetics of ruthenium organometallic anticancer compounds in living cells: a dose-dependent role for amino acid and iron transporters. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 5150-5158. [CrossRef]

- Minemura, T.; Lacy, W.W.; Crofford, O.B. Regulation of the transport and metabolism of amino acids in isolated fat cells. Effect of insulin and a possible role for adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 1970, 245, 3872-3881.

- Nishitani, S.; Matsumura, T.; Fujitani, S.; Sonaka, I.; Miura, Y.; Yagasaki, K. Leucine promotes glucose uptake in skeletal muscles of rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 299, 693-696. [CrossRef]

- Iwai, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Ikeda, H.O.; Tsujikawa, A. Branched chain amino acids promote ATP production via translocation of glucose transporters. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 7. [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, D.E.; Ockner, R.K.; Peterson, N.A.; Raghupathy, E. Modulation of membrane transport by free fatty acids: inhibition of synaptosomal sodium-dependent amino acid uptake. Biochemistry 1983, 22, 1965-1970. [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, D.E.; Kaplan, M.A.; Peterson, N.A.; Raghupathy, E. Effects of free fatty acids on synaptosomal amino acid uptake systems. J. Neurochem. 1982, 38, 1255-1260. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, S47-S64. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhang, F.; Liu, P.; Xu, T.; Ding, W. Vanadium(IV)-chlorodipicolinate alleviates hepatic lipid accumulation by inducing autophagy via the LKB1/AMPK signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 183, 66-76. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, R.; Li, J.; Zeng, G.; Yuan, J.; Su, J.; Wu, C.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Ding, W. Vanadium(IV)-chlorodipicolinate protects against hepatic steatosis by ameliorating lipid peroxidation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and inflammation. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11, 1093. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, L.; Gao, L.; Li, C.; Huan, Y.; Lei, L.; Cao, H.; Li, L.; Gao, A.; Liu, S.; Shen, Z. Combination of bis (α-furancarboxylato) oxovanadium (IV) and metformin improves hepatic steatosis through down-regulating inflammatory pathways in high-fat diet-induced obese C57BL/6J mice. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2021, 128, 747-757. [CrossRef]

- Le, M.; Rathje, O.; Levina, A.; Lay, P.A. High cytotoxicity of vanadium(IV) complexes with 1,10-phenanthroline and related ligands is due to decomposition in cell culture medium. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 22, 663-672. [CrossRef]

- Levina, A.; Crans, D.C.; Lay, P.A. Speciation of metal drugs, supplements and toxins in media and bodily fluids controls in vitro activities. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 352, 473–498. [CrossRef]

- Ścibior, A.; Zaporowska, H.; Ostrowski, J.; Banach, A. Combined effect of vanadium(V) and chromium(III) on lipid peroxidation in liver and kidney of rats. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2006, 159, 213-222. [CrossRef]

- Aureliano, M.; De Sousa-Coelho, A.L.; Dolan, C.C.; Roess, D.A.; Crans, D.C. Biological consequences of Vanadium effects on formation of reactive oxygen species and lipid peroxidation. Int. J. Mol. Sciences 2023, 24, 5382. [CrossRef]

- Marzban, L.; Rahimian, R.; Brownsey, R.W.; McNeill, J.H. Mechanisms by which bis(maltolato)oxovanadium(IV) normalizes phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucose-6-phosphatase expression in streptozotocin-diabetic rats in vivo. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 4636-4645. [CrossRef]

- Valera, A.; Rodriguez-Gil, J.E.; Bosch, F. Vanadate treatment restores the expression of genes for key enzymes in the glucose and ketone bodies metabolism in the liver of diabetic rats. J. Clin. Invest. 1993, 92, 4-11. [CrossRef]

- Ferber, S.; Meyerovitch, J.; Kriauciunas, K.M.; Kahn, C.R. Vanadate normalizes hyperglycemia and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase mRNA levels in ob/ob mice. Metabolism 1994, 43, 1346-1354. [CrossRef]

- Mosseri, R.; Waner, T.; Shefi, M.; Shafrir, E.; Meyerovitch, J. Gluconeogenesis in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice: in vivo effects of vandadate treatment on hepatic glucose-6-phoshatase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. Metabolism 2000, 49, 321-325. [CrossRef]

- Rines, A.K.; Sharabi, K.; Tavares, C.D.; Puigserver, P. Targeting hepatic glucose metabolism in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 786-804. [CrossRef]

- Vardatsikos, G.; Mehdi, M.Z.; Srivastava, A.K. Bis(maltolato)-oxovanadium (IV)-induced phosphorylation of PKB, GSK-3 and FOXO1 contributes to its glucoregulatory responses (review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2009, 24, 303-309. [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, M.Z.; Srivastava, A.K. Organo-vanadium compounds are potent activators of the protein kinase B signaling pathway and protein tyrosine phosphorylation: mechanism of insulinomimesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005, 440, 158-164. [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, I.A.; Da Silva Morais, A.; Schroyen, B.; Van Hul, N.; Geerts, A. Insulin resistance in hepatocytes and sinusoidal liver cells: mechanisms and consequences. J. Hepatol. 2007, 47, 142-156. [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, S.; McPherson, K.; Nair, S.; Ruff, D.; Stapleton, S.R. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the insulin-mimetics, selenium and vanadium, in insulin-resistance in primary hepatocytes. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 530.5-530.5. [CrossRef]

- Bulger, D.A.; Conley, J.; Conner, S.H.; Majumdar, G.; Solomon, S.S. Role of PTEN in TNFα induced insulin resistance. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 461, 533-536. [CrossRef]

- Boccato Payolla, F.; Andrade Aleixo N.; Resende Nogueira, F.A.; Massabni, A.C. Estudos in vitro da Atividade Antitumoral de Complexos de Vanádio com Ácidos Órotico e Glutâmico. Rev. Bras. Cancerol. [Internet]. 2020 Jan. 29 [cited 2023 Apr. 14];66(1):e-04649. [CrossRef]

- Levina, A.; Crans, D.C.; Lay, P.A. Advantageous reactivity of unstable metal complexes: Potential applications of metal-based anticancer drugs for intratumoral injections. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 790. [CrossRef]

- Szlasa, W.; Zendran, I.; Zalesińska, A.; Tarek, M.; Kulbacka, J. Lipid composition of the cancer cell membrane. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2020, 52, 321-342. [CrossRef]

- Welte, S.; Baringhaus, K.H.; Schmider, W.; Müller, G.; Petry, S.; Tennagels, N. 6,8-Difluoro-4-methylumbiliferyl phosphate: a fluorogenic substrate for protein tyrosine phosphatases. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 338, 32-8. [CrossRef]

- Pastula, C.; Johnson, I.; Beechem, J.M.; Patton, W.F. Development of fluorescence-based selective assays for serine/threonine and tyrosine phosphatases. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2003, 6, 341-6. [CrossRef]

- Wensaas, A.J.; Rustan, A.C.; Lövstedt, K.; Kull, B.; Wikström, S.; Drevon, C.A.; Hallén, S. Cell-based multiwell assays for the detection of substrate accumulation and oxidation. J. Lipid Res. 2007, 48, 961-7. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Ueda-Wakagi, M.; Sato, T.; Kawasaki, K.; Sawada, K.; Kawabata, K.; Akagawa, M.; Ashida, H. Measurement of glucose uptake in cultured cells. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2015, 71, 12.14.1-12.14.26. [CrossRef]

- Pither, R.; Game, S.; Davis, J.; Katz, M.; McLane, J. The use of Cytostar-T™ scintillating microplates to monitor insulin-dependent glucose uptake by 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 1996, 104, 115-116. [CrossRef]

- Tanti, J.F.; Cormont, M.; Grémeaux, T.; Le Marchand-Brustel, Y. Assays of glucose entry, glucose transporter amount, and translocation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2001, 155, 157-65. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Lechón, M.J.; Donato, M.T.; Martínez-Romero, A.; Jiménez, N.; Castell, J.V.; O'Connor, J.E. A human hepatocellular in vitro model to investigate steatosis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2007, 165, 106-16. [CrossRef]

- Ricchi, M.; Odoardi, M.R.; Carulli, L.; Anzivino, C.; Ballestri, S.; Pinetti, A.; Fantoni, L.I.; Marra, F.; Bertolotti, M.; Banni, S.; Lonardo, A.; Carulli, N.; Loria, P. Differential effect of oleic and palmitic acid on lipid accumulation and apoptosis in cultured hepatocytes. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 24, 830-40. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, T.; Kanemoto, N.; Ban, T.; Sudo, T.; Nagano, K.; Niki, I. Establishment and characterization of a novel method for evaluating gluconeogenesis using hepatic cell lines, H4IIE and HepG2. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2009, 491, 46-52. [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, I.; Solís-Muñoz, P.; Gómez-Izquierdo, E.; Muñoz-Yagüe, M.T.; Valverde, A.M.; Solís-Herruzo, J.A. Protein-tyrosine phosphatases are involved in interferon resistance associated with insulin resistance in HepG2 cells and obese mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 19564-73. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Han, Z.; Bei, W.; Rong, X.; Guo, J.; Hu, X. Oleanolic acid attenuates insulin resistance via NF-κB to regulate the IRS1-GLUT4 pathway in HepG2 cells. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 2015, 643102. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, T.; Gulliksson, H.; Palmeborn, M.; Bergström, K.; Thore, A. Leakage of adenylate kinase from stored blood cells. J. Appl. Biochem. 1983, 5, 437-45.

- Eglen, R.M.; Reisine, T.; Roby, P.; Rouleau, N.; Illy, C.; Bossé, R.; Bielefeld, M. The use of AlphaScreen technology in HTS: current status. Curr .Chem. Genomics. 2008, 1, 2-10. [CrossRef]

| Compound | Starting amino acid | Structural formula of the complex |

Elemental analysis of the complex* [%] | IR bands [cm-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VC054 | L-tryptophan | [VOCl2(L1)]·THF·6HCl

|

C, 37.38; 37.20 H, 4.86; 4.25 N, 5.22; 5.21 S, 2.91; 3.97 |

3192 (w), 3054 (w), 2922 (s), 1709 (w), 1645 (s), 1619 (w), 1523 (w), 1491 (w), 1430 (m), 1396 (w), 1370 (m), 1253 (w), 1199 (w), 1120 (w), 1040 (w), 983 (m), 807 (w), 744 (m), 701 (m), 599 (w) |

| VC059 | L-phenylalanine | [VOCl2(L2)]·0.5Et2O·1.5HCl

|

C, 44.62; 44.91 H, 4.35; 4.47 N, 4.58; 4.87 S, 5.55; 5.58 |

3059 (s), 1709 (w), 1624 (s), 1606 (s), 1524 (w), 1497 (s), 1439 (m), 1407 (w), 1349 (w), 1221 (w), 1131 (w), 1078 (w), 1025 (w), 986 (m), 813 (w), 755 (m), 701 (m), 600 (w) |

| VC070 | L-leucine | [VOCl2(L3)]·2.5HCl

|

C, 36.54; 35.96 H, 4.66; 4.43 N, 4.88; 5.24 S, 5.40; 6.00 |

3070 (s), 2958 (s), 1714 (w), 1618 (s), 1560 (w), 1523 (m), 1497 (s), 1447 (m), 1412 (w), 1231 (w), 1179 (w), 1120 (w), 1078 (w), 988 (m), 946 (w), 876 (w), 760 (m), 696 (m), 603 (w) |

| VC073 | L-methionine | [VOCl2(L4)]·THF·2HCl

|

C, 37.29; 37.64 H, 4.79; 4.82 N, 3.98; 4.62 S, n/a |

3181 (w), 3001 (s), 2921 (s), 1709 (w), 1614 (s), 1603 (s), 1560 (w), 1528 (s), 1491 (s), 1433 (s), 1346 (w), 1243 (w), 1136 (w), 1078 (w), 983 (m), 760 (m), 692 (m), 596 (w) |

| VC109 | D/L-isoleucine | [VOCl2(L5)]·3HCl

|

C, 34.77; 34.55 H, 4.38; 4.35 N, 5.07; 5.04 S, 5.80; 5.77 |

3338 (w), 3059 (w), 2970 (s), 2939 (w), 2885 (w), 1729 (w), 1606 (s), 1520 (s), 1489 (s), 1447 (m), 1389 (w), 1350 (w), 1218 (w), 1180 (w), 1114 (w), 986 (m), 865 (w), 758 (m), 696 (m), 599 (w) |

| Compound | Formula | Ln components (1:1 molar ratio) | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldehyde | Hydrazide | |||

| VC013 | [VO(L6)(phen)] ⋅H2O | 5-bromosalicyl-aldehyde | 2-hydroxybenzhydrazide | [45] |

| VC029 | [V(L7)(HL7)] | 2-hydroxybenzhydrazide | [46] | |

| VC032 | [V(L8)(HL8)]⋅H2O | benzhydrazide | [47] | |

| VC046 | [VO(L9)(phen)]⋅2H2O | 4-hydroxybenzhydrazide | [46] | |

| VC048 | [VO(L10)(phen)]⋅0.5H2O | 4-tertbutylbenzhydrazide | [47] | |

| VC055 | [V(L11)(HL11)] | 4-methoxybenzhydrazide | -* | |

| VC050 | [VO(L11)(phen)] | 4-chlorobenzhydrazide | [46] | |

| VC067 | [V(L12)(HL12)] | 3-hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid hydrazide | [46] | |

| VC068 | [V(L13)(HL13)] | 4-nitrobenzhydrazide | [46] | |

| PTP1B | LAR | SHP1 | SHP2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparators | VOSO4 | 62 | 44 | 70 | 77 |

| BMOV | 77 | 58 | 76 | 82 | |

| ONS complexes | VC054 | 78 | 67 | 84 | 87 |

| VC059 | 79 | 71 | 82 | 87 | |

| VC070 | 79 | 69 | 84 | 88 | |

| VC073 | 74 | 63 | 82 | 86 | |

| VC109 | 70 | 56 | 80 | 83 | |

| ONO complexes | VC013 | 60 | 66 | 67 | 74 |

| VC029 | 31 | 25 | 62 | 68 | |

| VC032 | 9 | 8 | 44 | 48 | |

| VC046 | 34 | 37 | 62 | 66 | |

| VC048 | 36 | 35 | 62 | 64 | |

| VC050 | 25 | 19 | 53 | 57 | |

| VC055 | 24 | 18 | 56 | 57 | |

| VC067 | 42 | 39 | 70 | 74 | |

| VC068 | 40 | 33 | 70 | 74 |

| IC50 [nM] | Log IC50±SD | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTP1B | LAR | SHP1 | SHP2 | PTP1B | LAR | SHP1 | SHP1 | ||

| Comparators | VOSO4 | 99 | 95 | 17 | 13 | -7.00±0.07 | -7.88±0.10 | -7.77±0.02 | -7.77±0.02 |

| BMOV | 149 | 140 | 14 | 8 | -6.83±0.02 | -8.09±0.11 | -7.86±0.03 | -7.86±0.03 | |

| ONS complexes | VC054 | 141 | 112 | 20 | 20 | -6.85±0.01 | -7.70±0.06 | -7.56±0.02 | -7.56±0.02 |

| VC059 | 107 | 76 | 26 | 13 | -6.97±0.01 | -7.87±0.06 | -7.59±0.04 | -7.59±0.04 | |

| ONO complexes | VC050 | 4263 | 1714 | 657 | 273 | -5.37±0.03 | -6.56±0.04 | -6.18±0.03 | -6.18±0.03 |

| VC068 | 2034 | 619 | 517 | 235 | -5.69±0.02 | -6.63±0.03 | -6.29±0.02 | -6.29±0.02 | |

| CDC25A | PP2A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 µM | 1 µM | 10 µM | 1 µM | ||

| Comparators | VOSO4 | 62±1 | 54±2 | 40±3 | 32±2 |

| BMOV | 61±1 | 54±1 | 63±4 | 52±15 | |

| ONS complexes | VC054 | 65±3 | 51±2 | 75±7 | 41±15 |

| VC059 | 68±3 | 55±3 | 54±9 | 44±1 | |

| ONO complexes | VC050 | 38±1 | 12±8 | 51±4 | 24±3 |

| VC068 | 62±2 | 54±3 | 55±15 | 26±12 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).