Submitted:

20 April 2023

Posted:

21 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

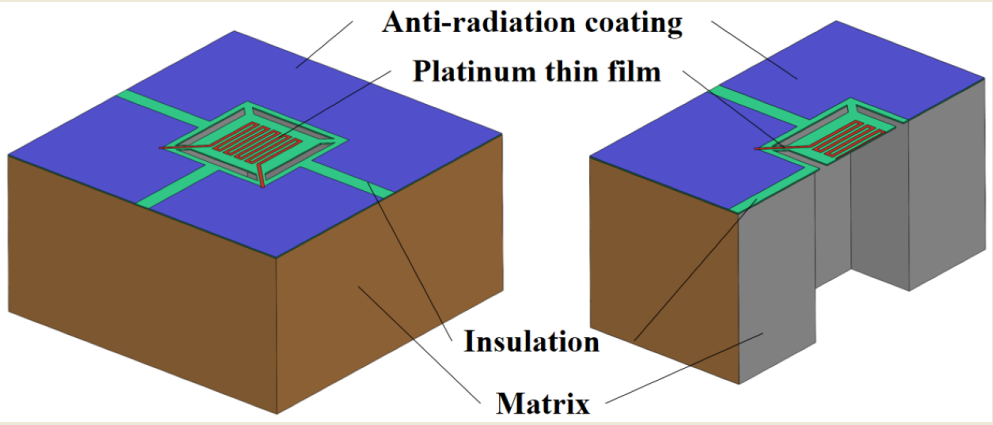

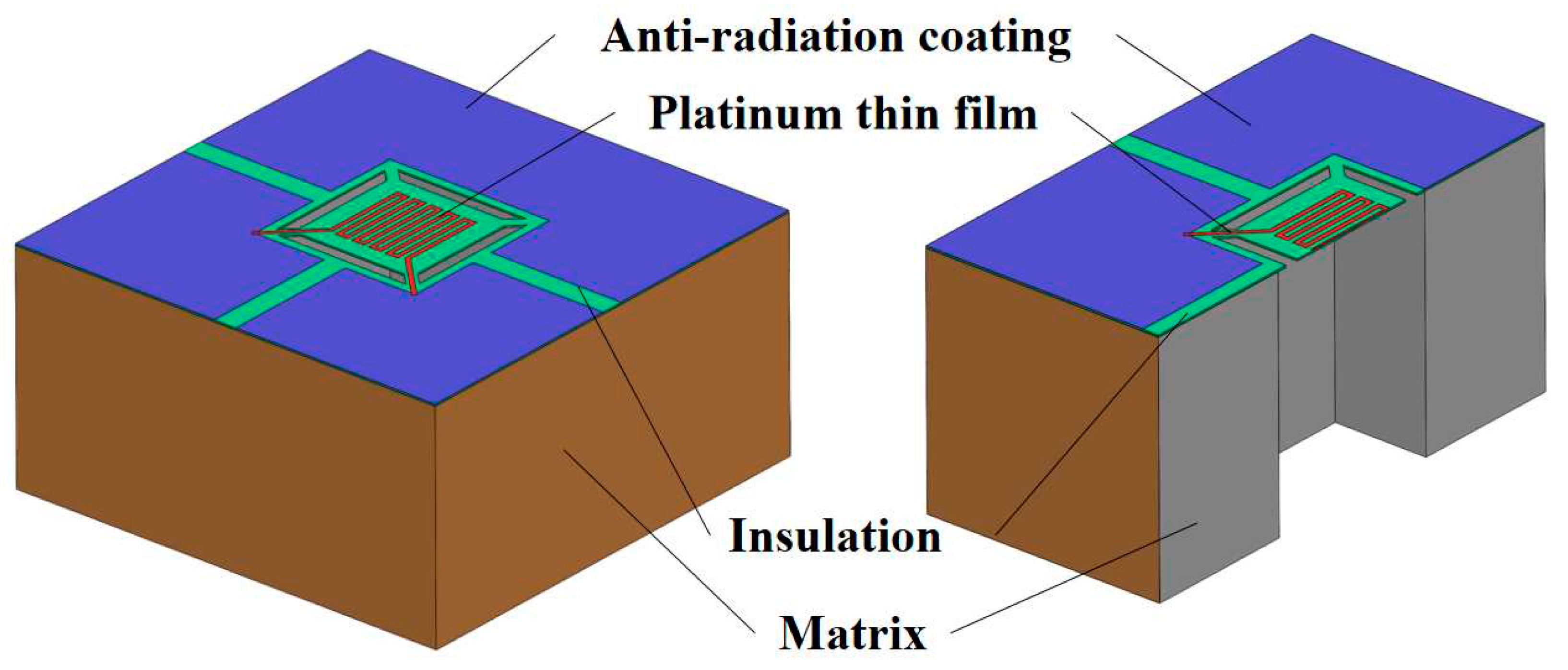

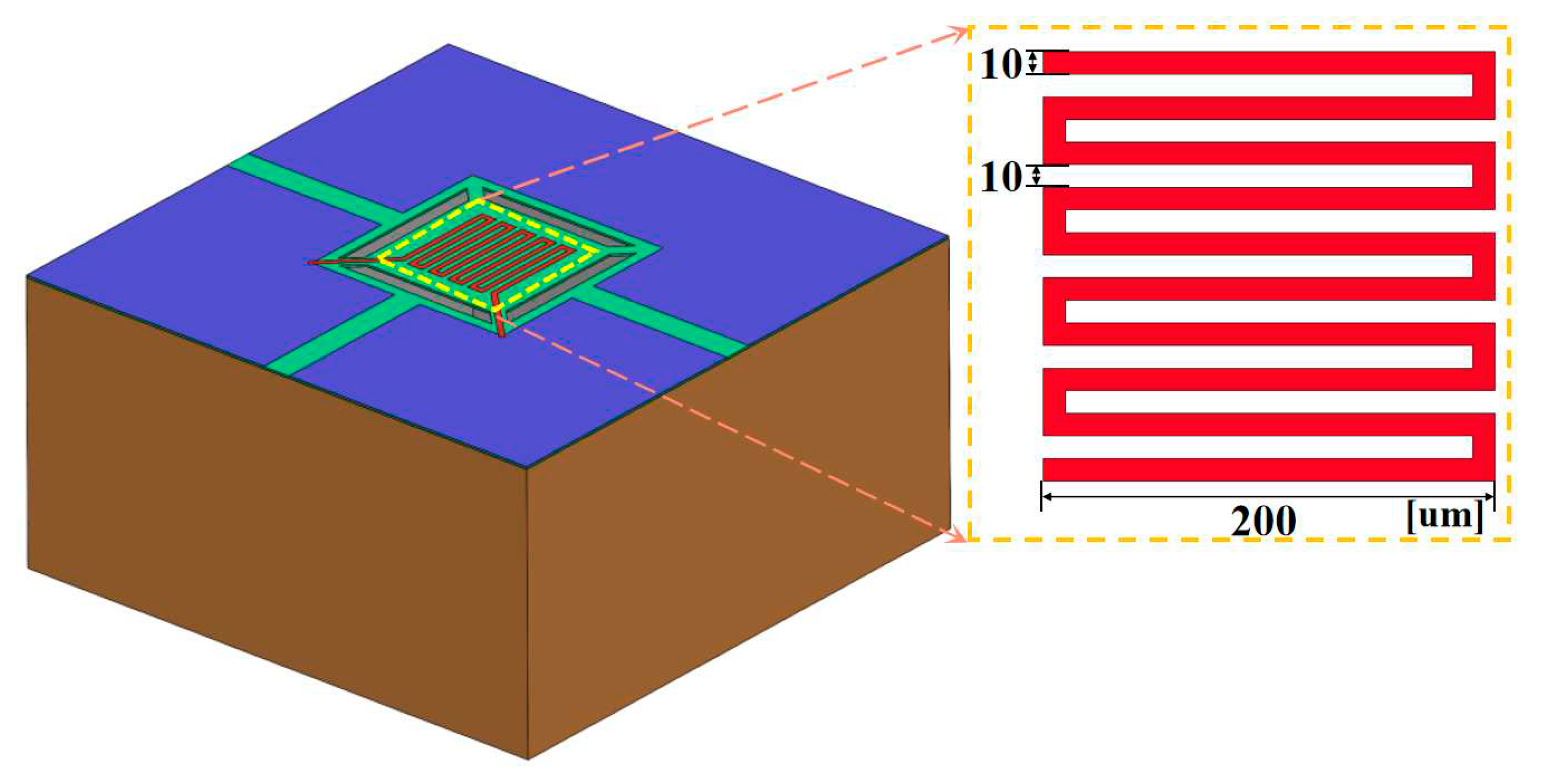

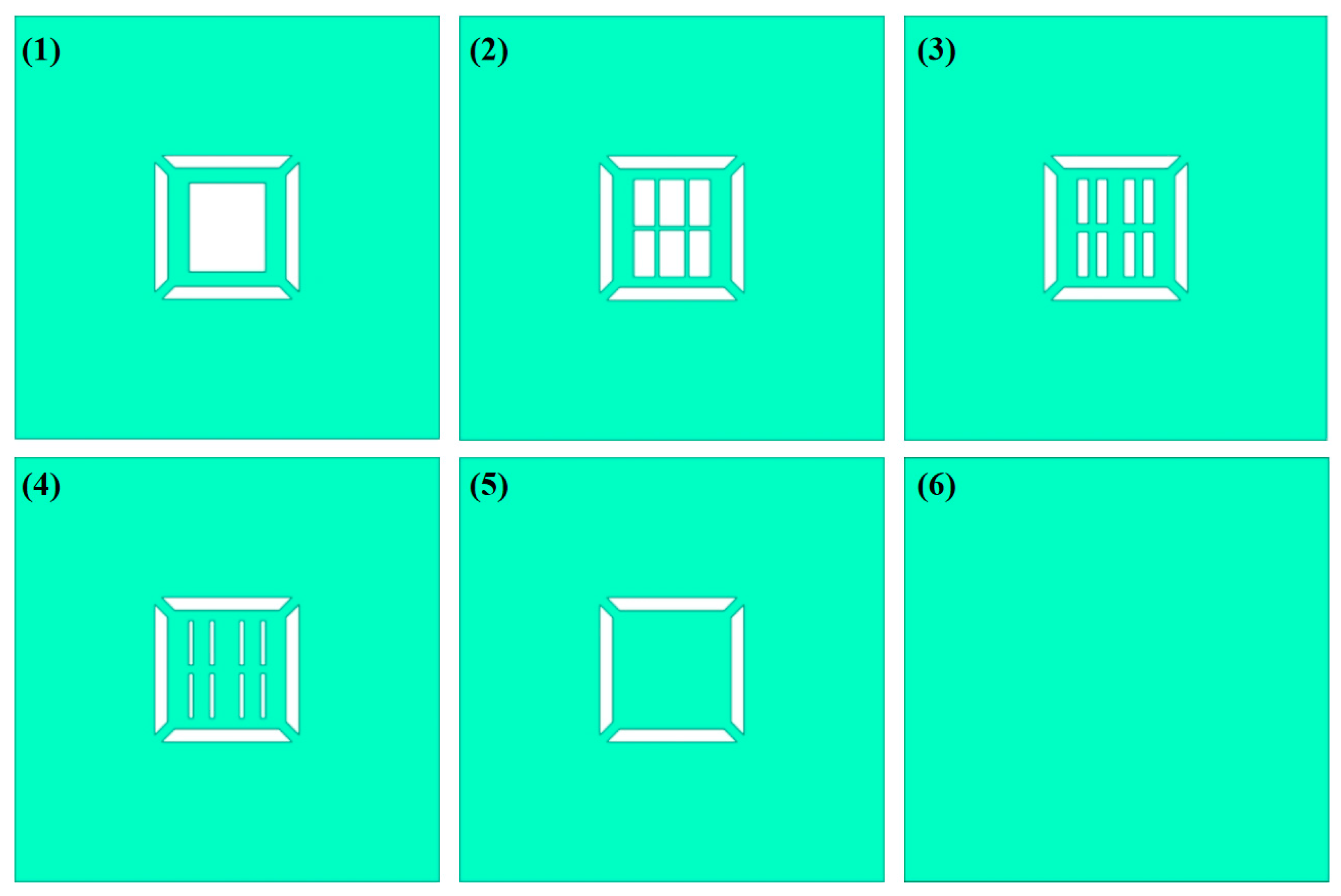

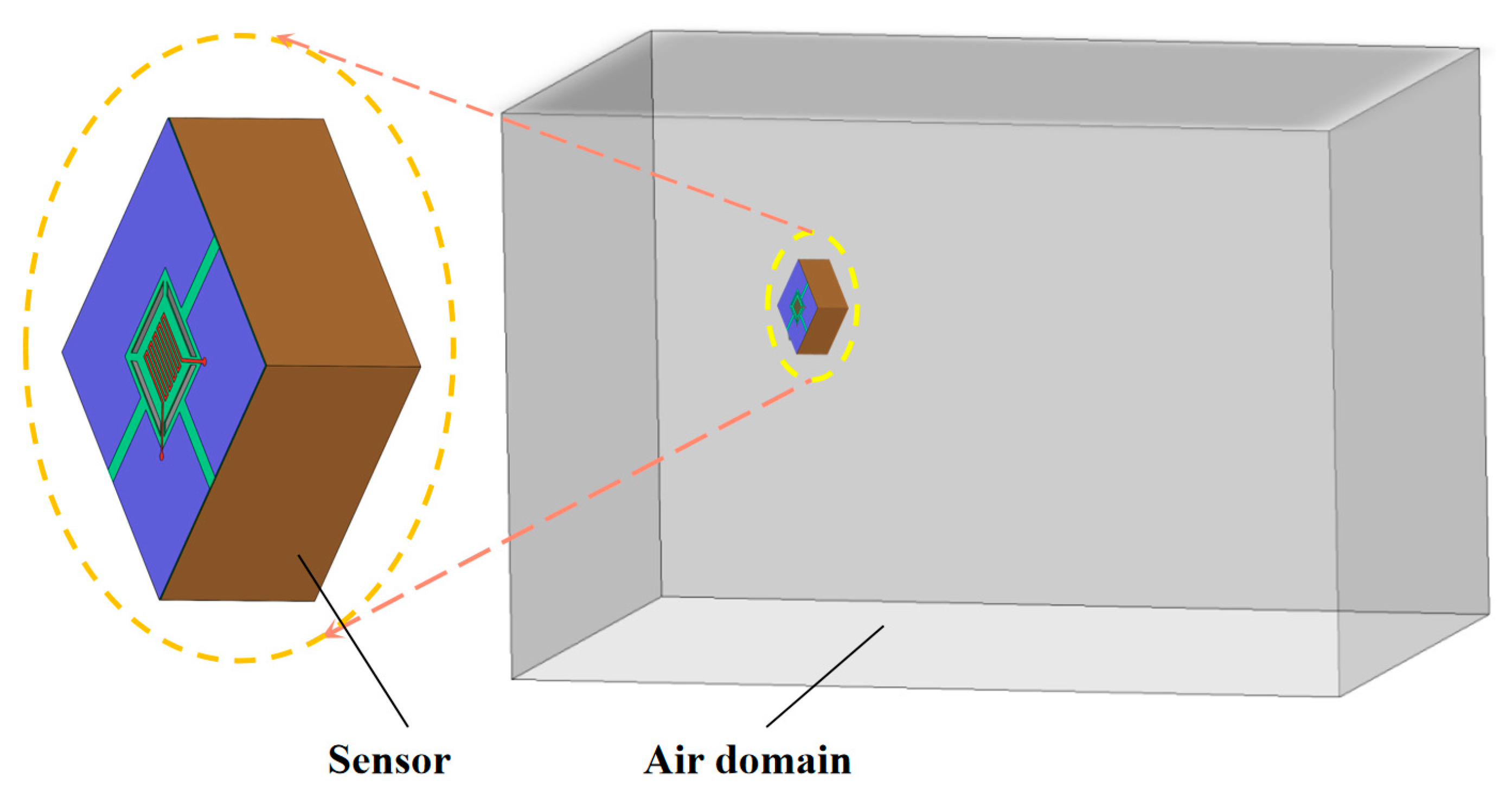

2.1. Structure of thin film temperature sensor

2.2. Measurement model of thin film temperature sensor

3. Theoretical analysis and simulation model of temperature error

3.1. Joule heat

3.2. Solar radiation

3.3. Aerodynamic heat

3.4. Overall model

4. Results and discussion

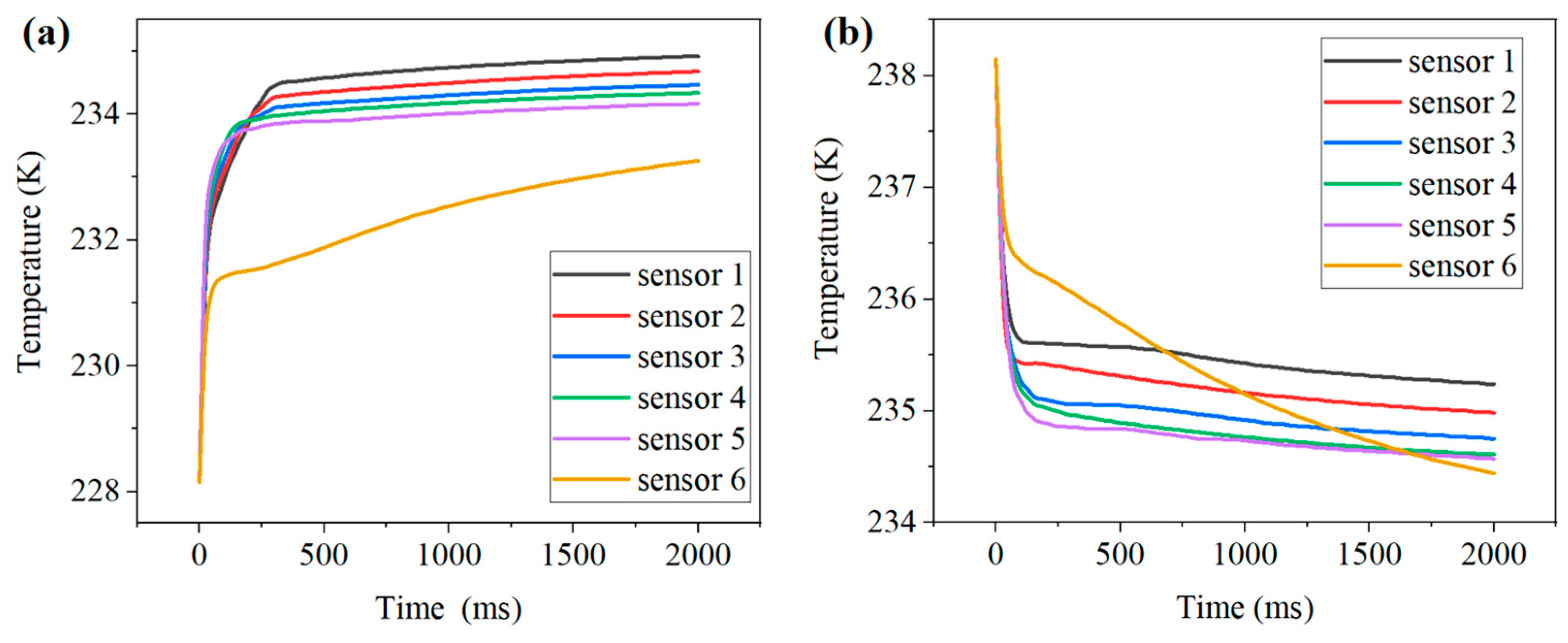

4.1. Joule heat

4.1.1. The effect of different insulators on Joule thermal errors

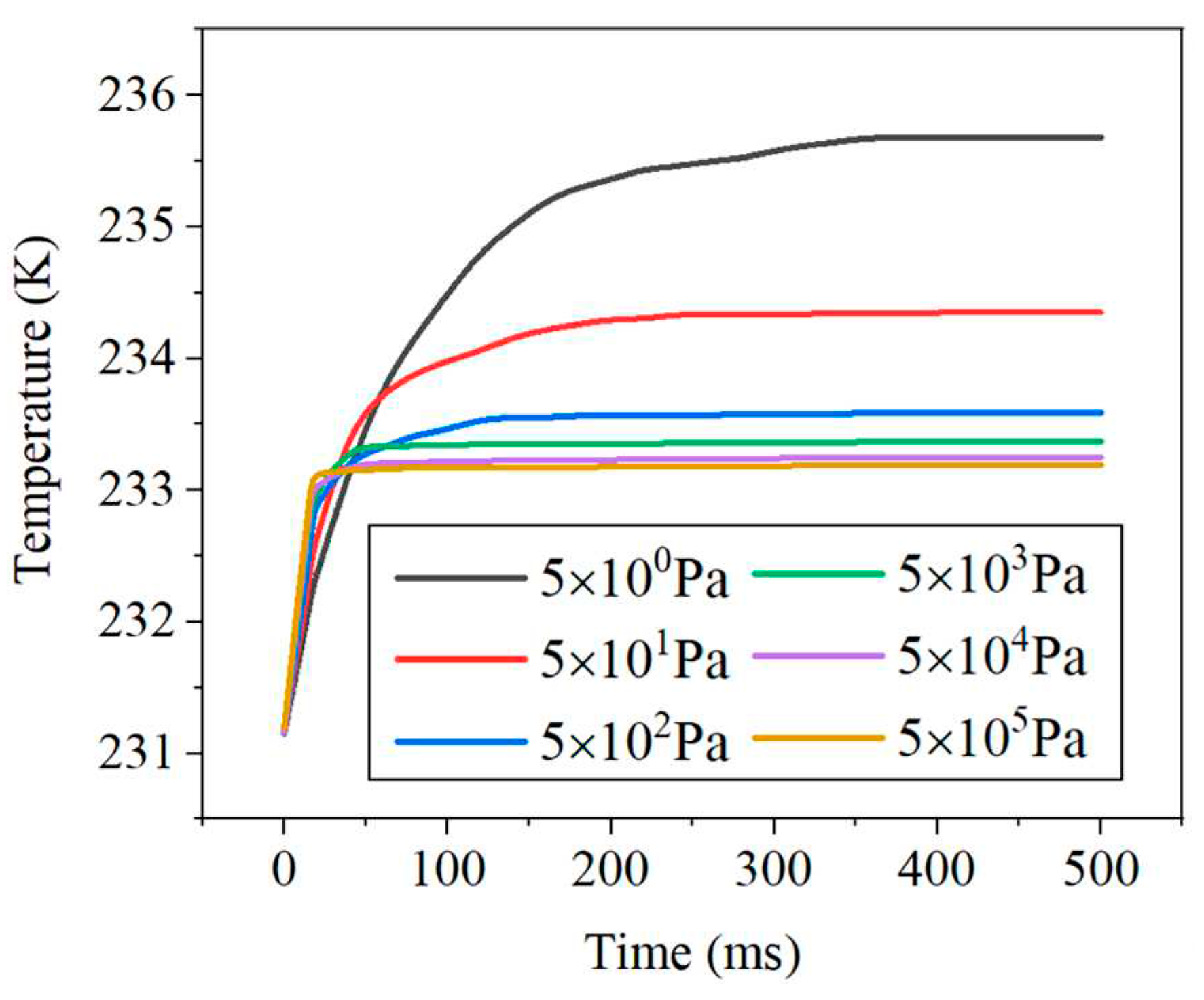

4.1.2. The effect of air pressure on the temperature measurement process of the temperature sensor

4.2. Solar radiation

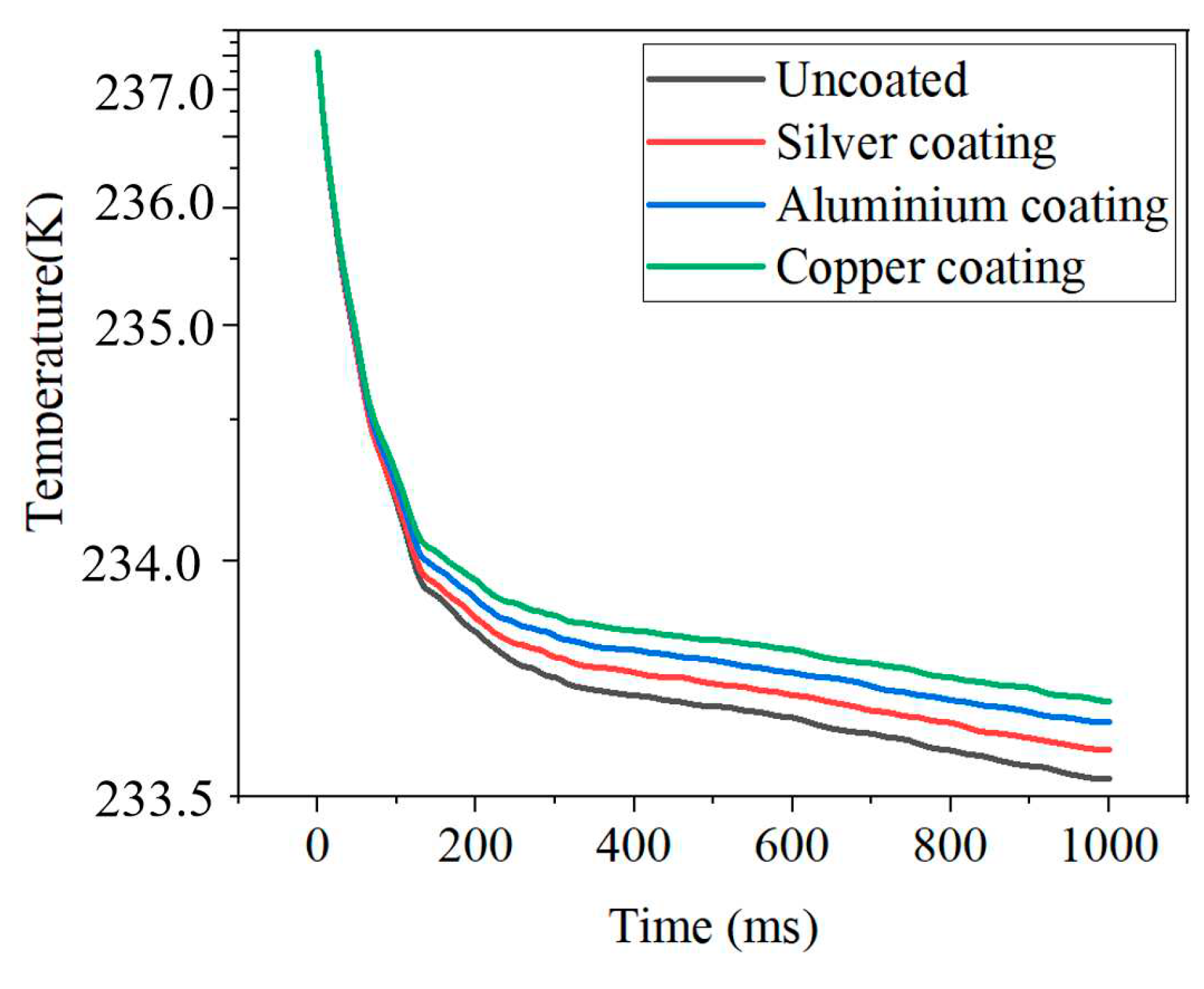

4.2.1. The effect of different coatings on radiant heat errors

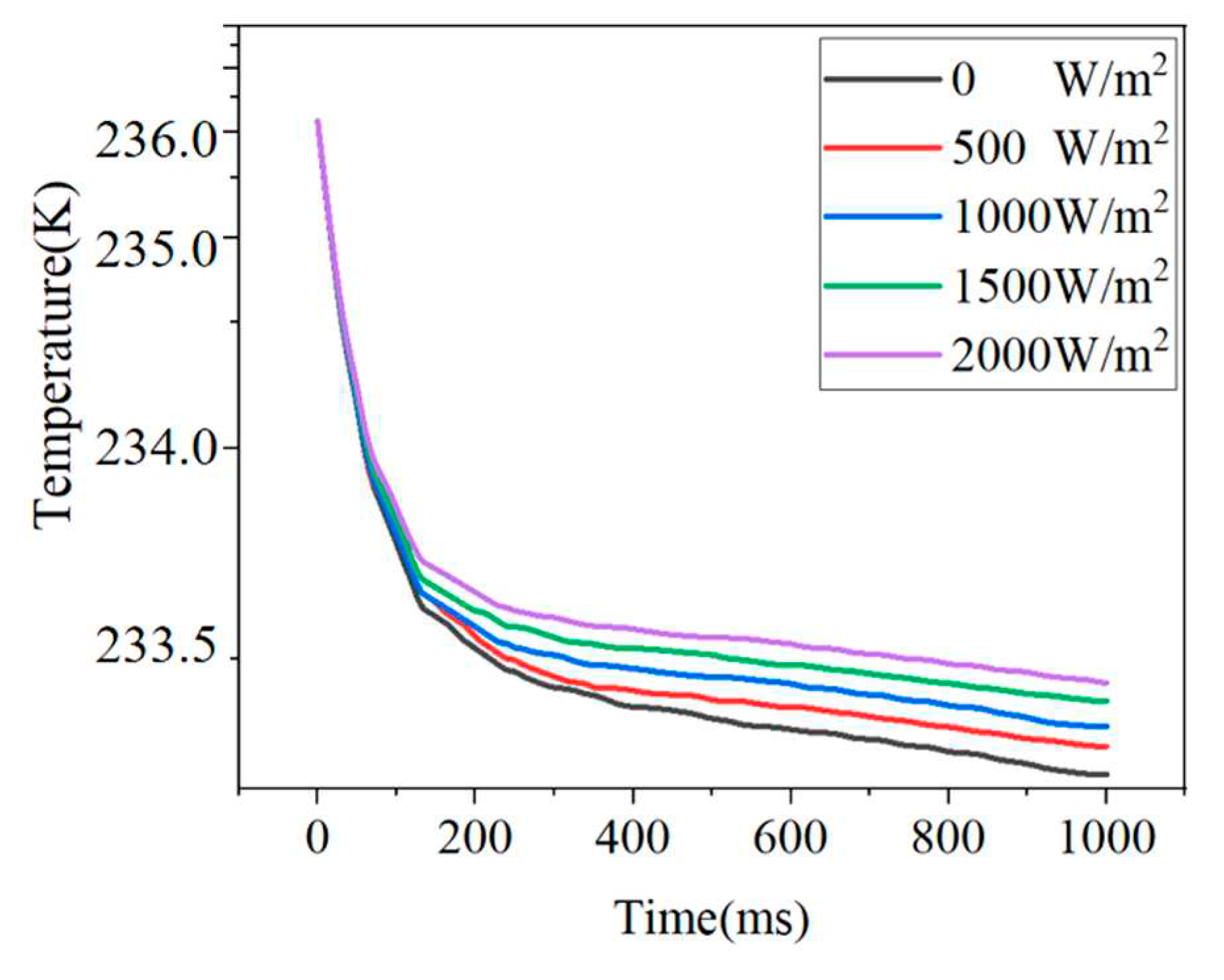

4.2.2. The effect of radiation conditions on radiant heat errors

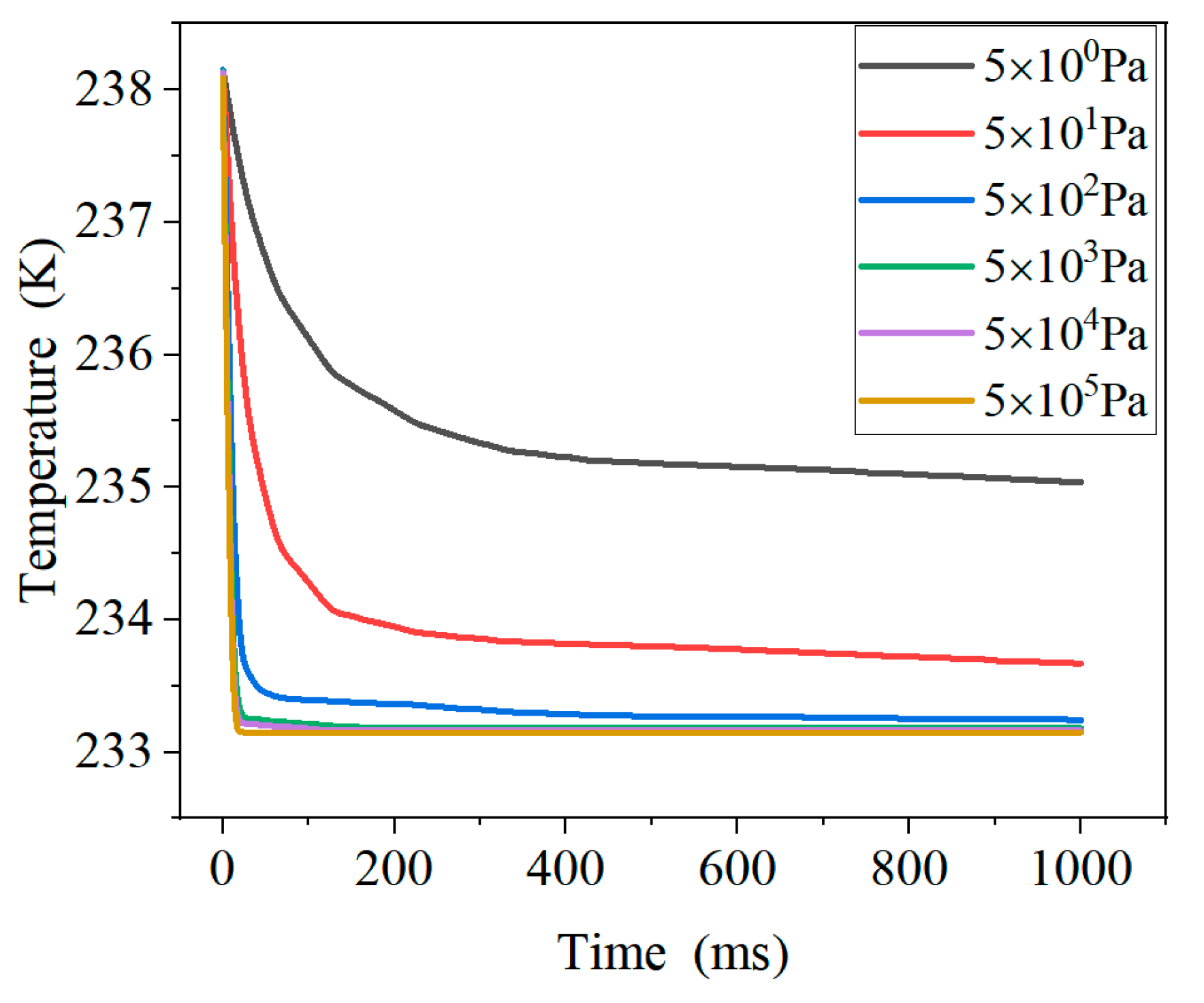

4.2.3. The effect of different air pressures on radiant heat errors

4.3. Aerodynamic heat

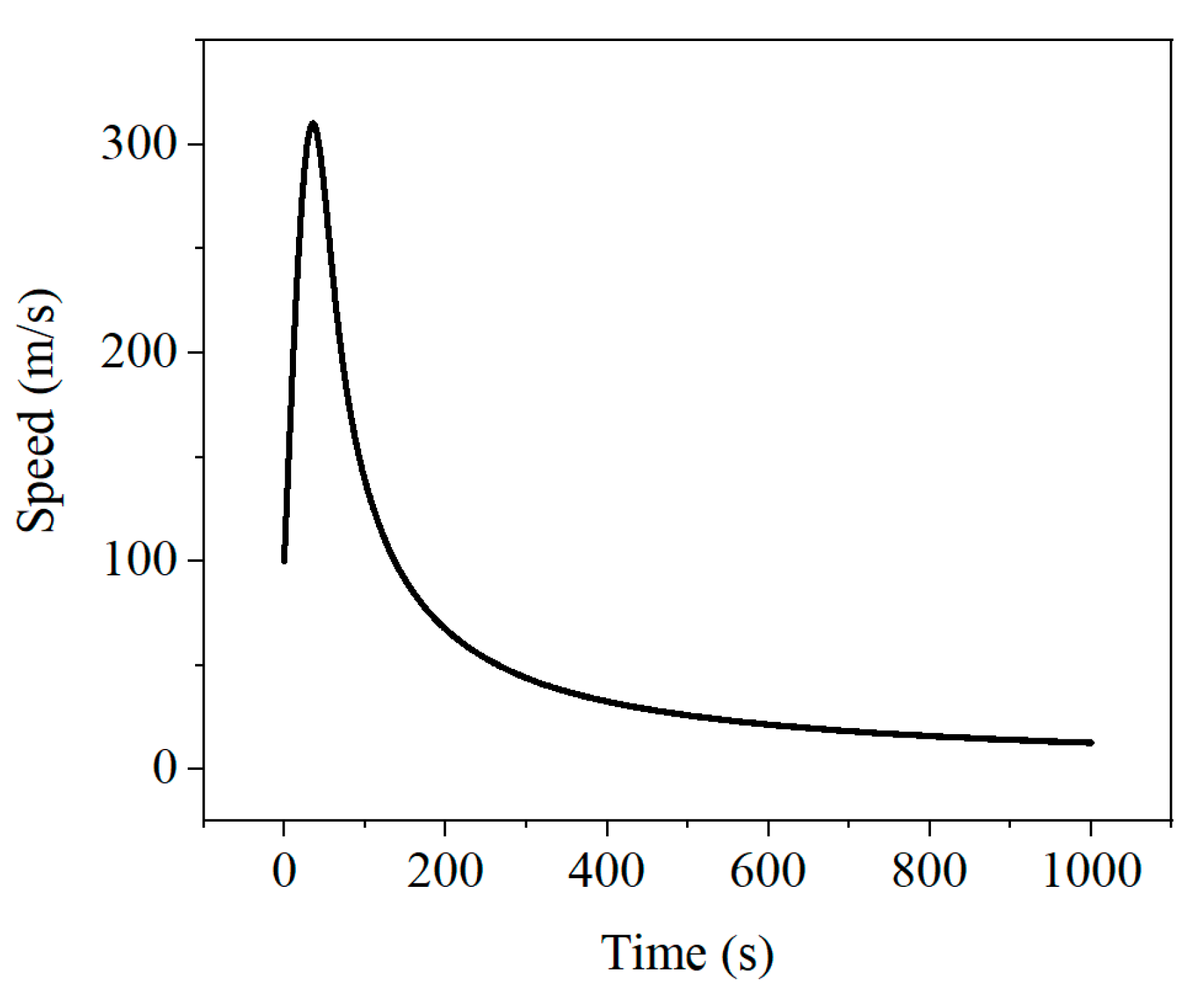

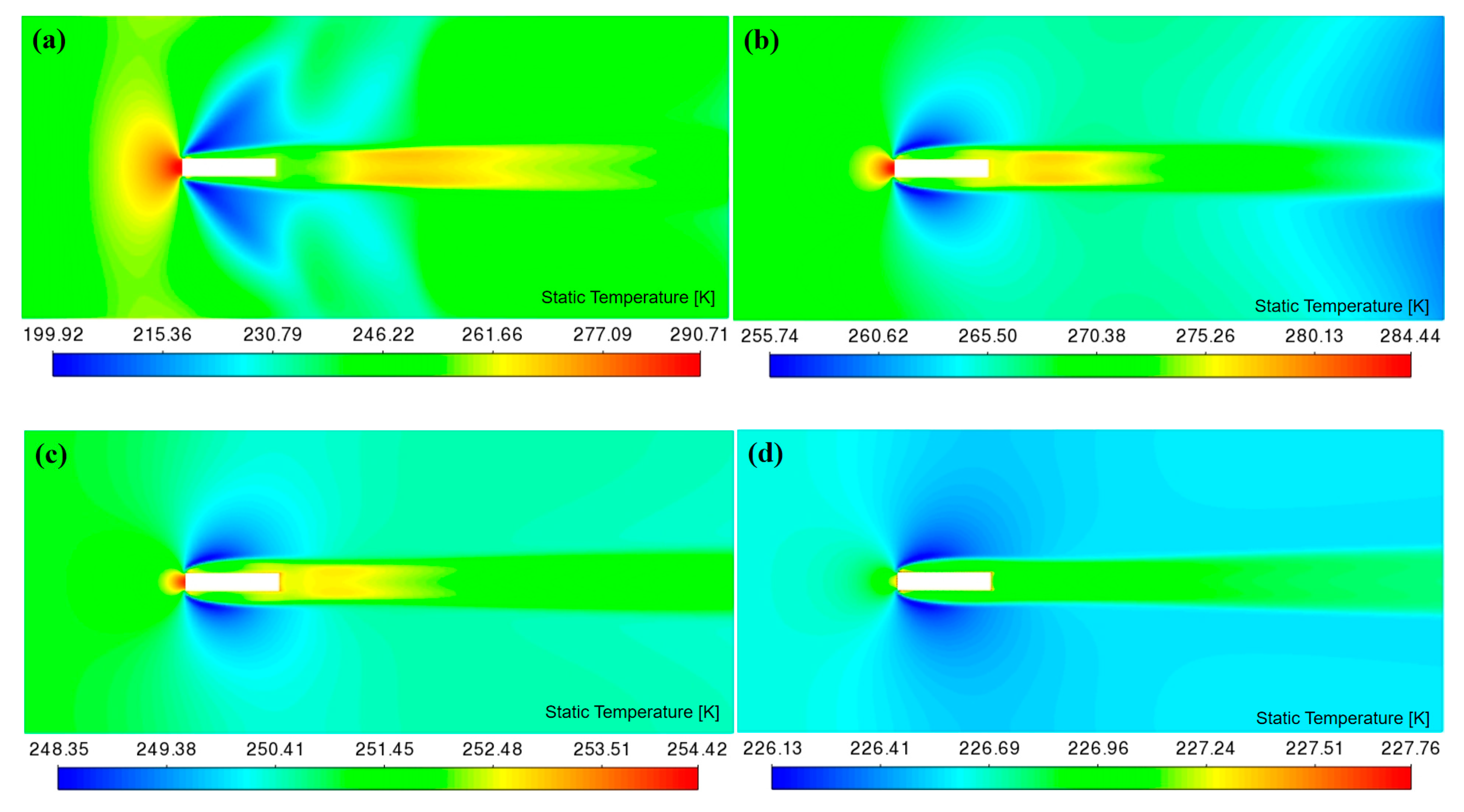

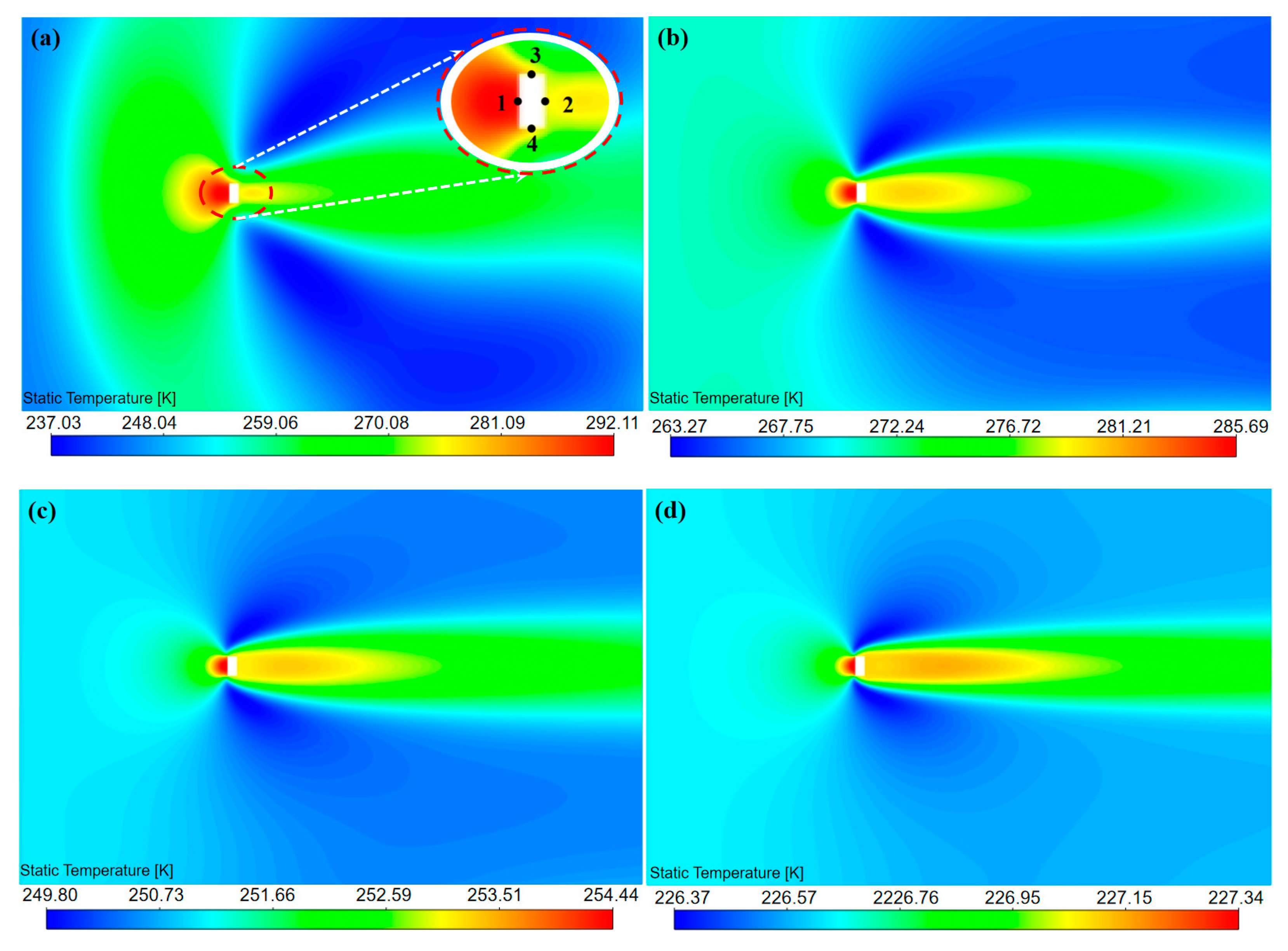

4.3.1. Aerodynamic heat field distribution at different altitudes

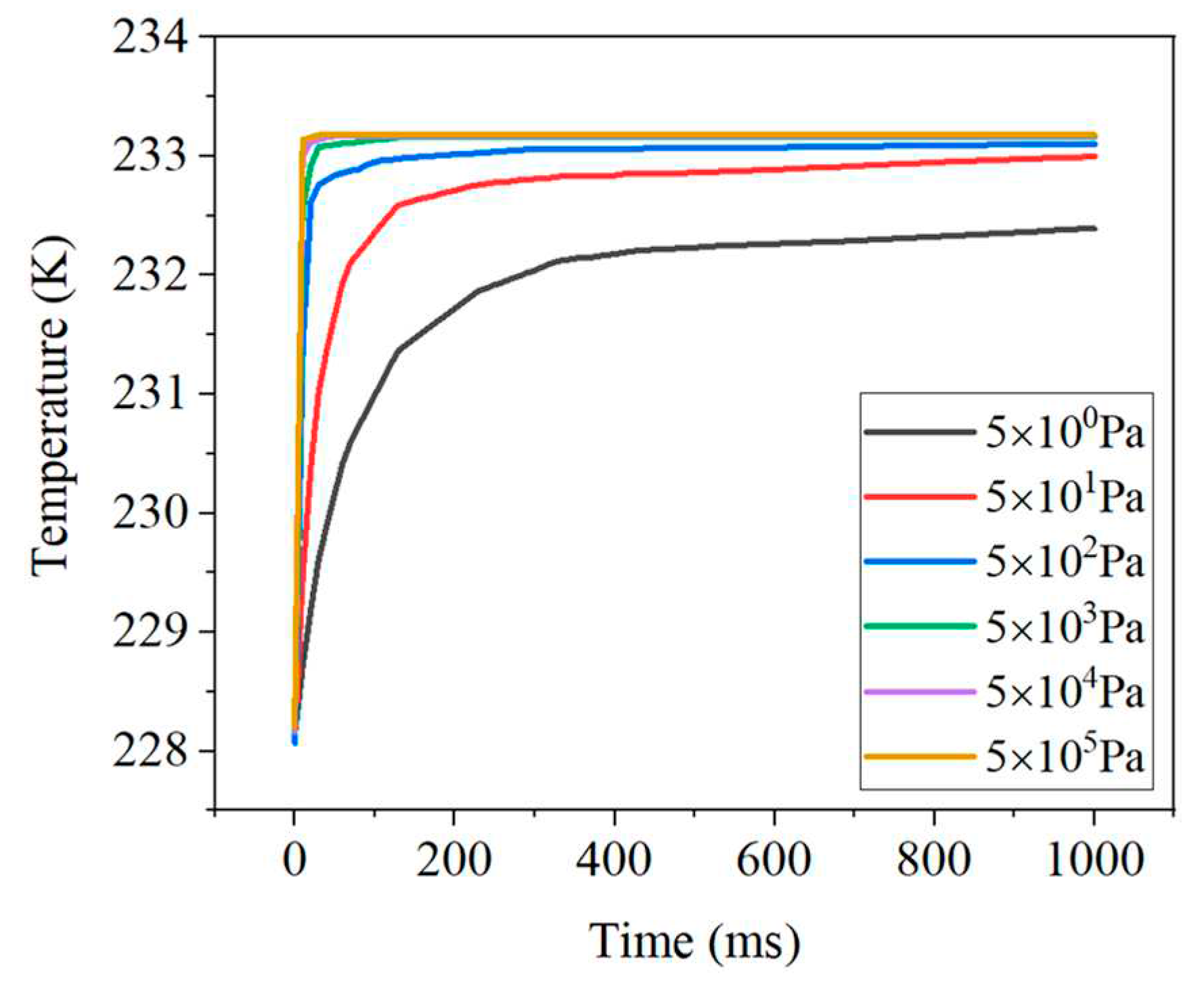

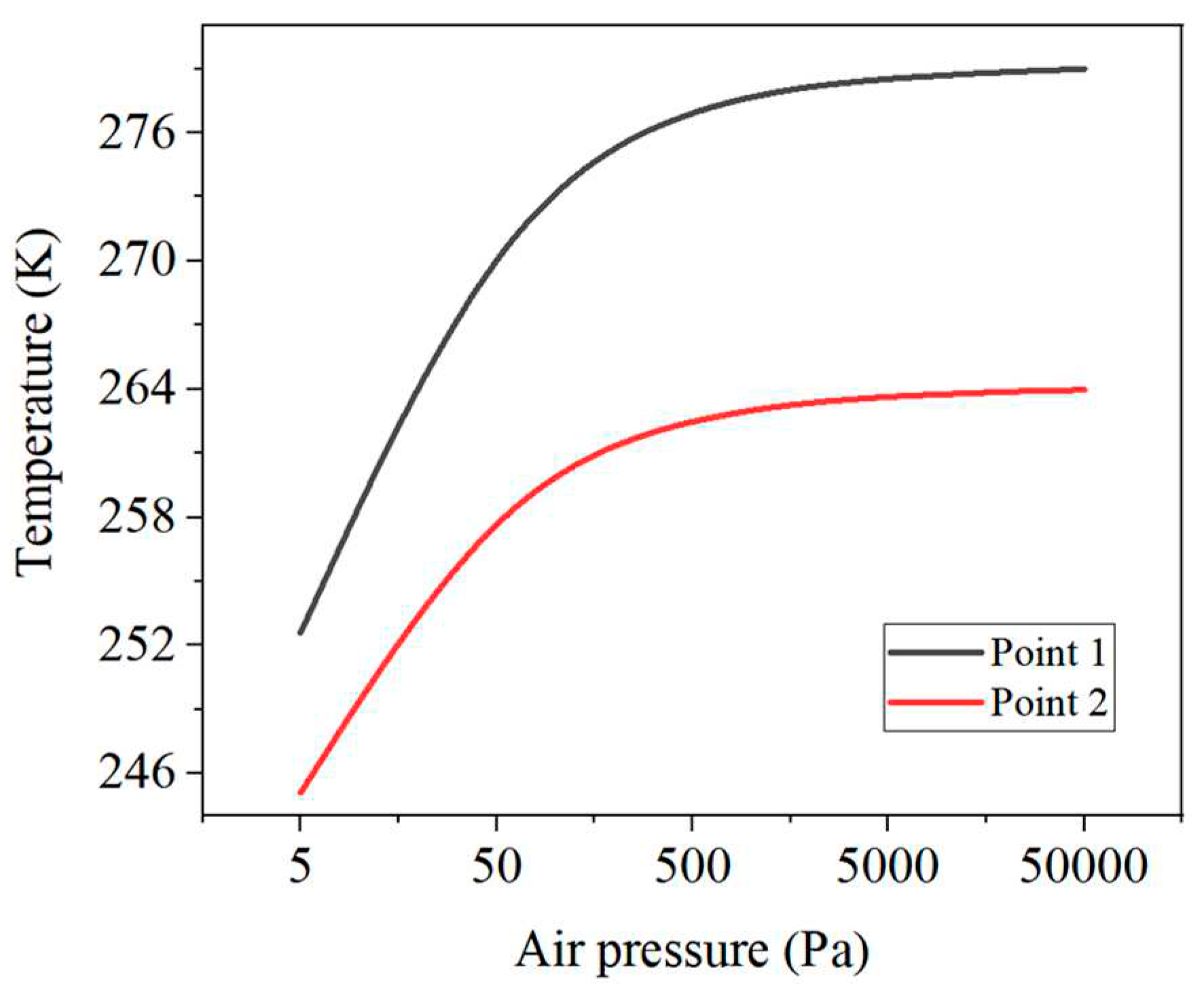

4.3.2. The effect of different air pressures on aerodynamic heat errors

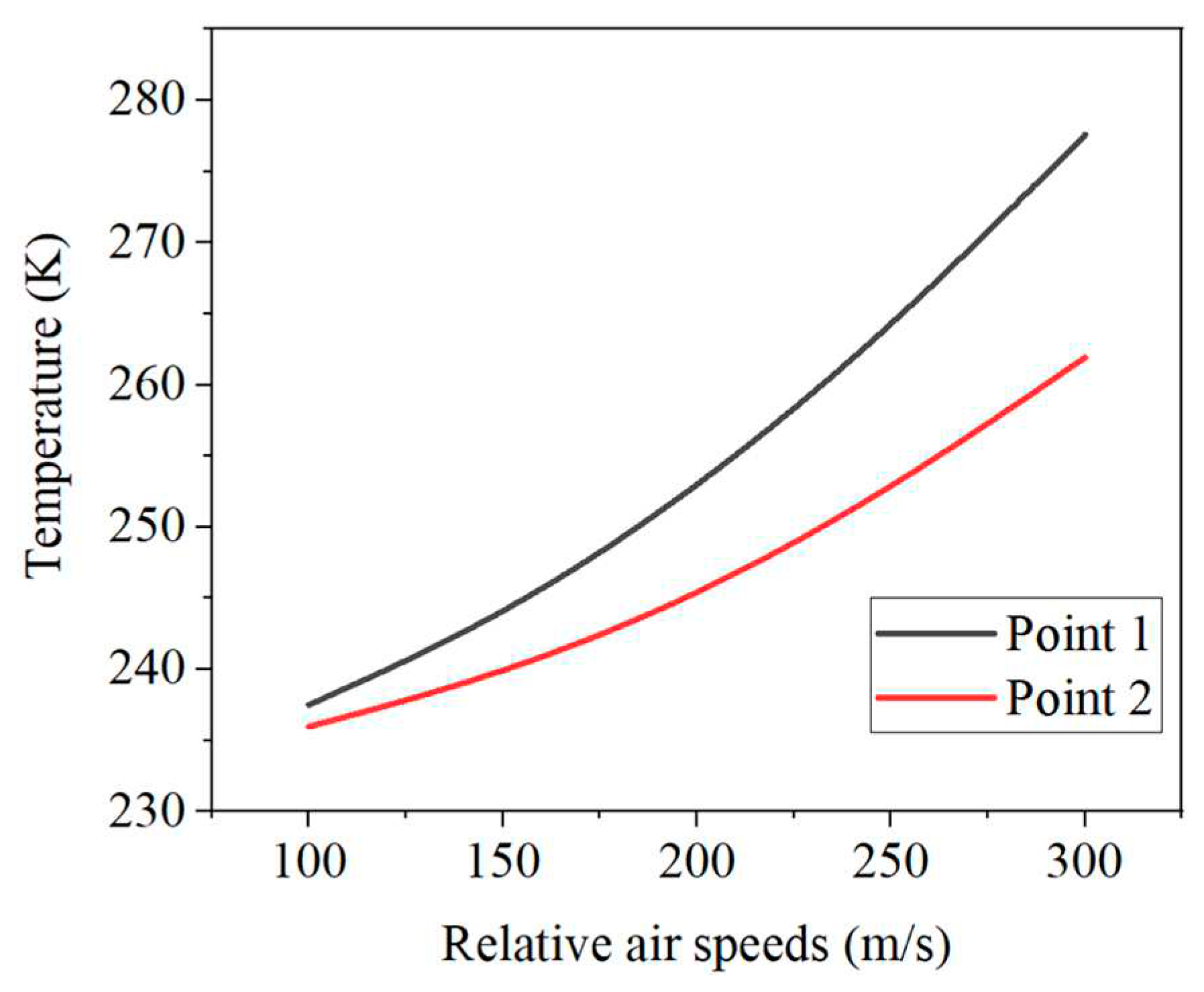

4.3.3. The effect of different relative air speeds on aerodynamic heat errors

4.4. Overall analysis

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The temperature sensor has a micro-bridge structure and uses silver as the radiation-proof coating with a small response time. The sensor has a response time of 20 ms when heating up and 99 ms when cooling down under the influence of Joule heat. The choice of silver as the radiation-proof coating, with small radiation heat error, improves the measurement accuracy of the temperature sensor.

- (2)

- According to the optimized near space temperature error model, the resulting temperature measurement errors include aerodynamic heat, solar radiation and Joule heat. Aerodynamic heat has the greatest effect on temperature error, and solar radiant heat has the least effect.

- (3)

- The aerodynamic thermal error at the front end of the radionsonde is the largest, and the temperature error at the rear end is the smallest. The temperature sensor is arranged at the front end of the radiosonde. The aerodynamic thermal error of the front end of the sensor is the largest, the rear end has the smallest temperature error, and the Pt thin film is installed at the rear end of the sensor.

- (4)

- As the air pressure increases there will be the following changes: the response rate of the temperature sensor increases and the steady-state temperature is closer to the ambient temperature, i.e. the temperature error decreases. The temperature of the sensor rises rapidly and then slowly.

- (5)

- As the relative flow rate of air increases, the temperature of the sensor increases, and the rate of temperature rise increases.

- (6)

- Through the establishment of the temperature error model, the accuracy of obtaining the temperature value of near space can be greatly improved.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roney, J.A. Statistical wind analysis for near-space applications. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 2007, 69, 1485–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadi, M.; Popov, G.A; Lu, Z.; Eskenazi, A.G.; Bang, A.J.W.; Campbell, M.F.; Hu, H.; Bargatin, I. Controlled levitation of nanostructured thin films for sun-powered near-space flight. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.Q.; Cai, J.; Peng, Q. Near-space microwave radar remote sensing: Potentials and challenge analysis. Remote Sens. 2010, 2, 717–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Q. Near-space vehicles: Supply a gap between satellites and airplanes for remote sensing. IEEE Aero. El. Sys. Mag. 2011, 26, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Hu, X.; Guo, Z.; Zhu, L. Temperature-compensated fiber-optic online monitoring methodology for 3D shape and strain of near-space airship envelope. Appl. Opt. 2022, 61, 9279–9295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wu, K.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, F. The near-space wind and temperature sensing interferometer: forward model and measurement simulation. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.X.; Li, Y.Z.; Yu, X.K.; Li, G.C.; Ji, X.Y. Investigation of heat transfer mechanism of low environmental pressure large-space spray cooling for near-space flight systems. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2018, 119, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Yang, G.; Liu, G.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, T. Effects and mechanism on Kapton film under ozone exposure in a ground near space simulator. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 440, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozubek, M.; Laštovička, J.; Zajicek, R. Climatology and long-term trends in the stratospheric temperature and wind using ERA5. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Sheng, Z.; Fan, Z.Q.; Zhou, S.D.; Shi, W.L. Data analysis of upper atmosphere temperature detected by sounding rockets in China. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2017, 34, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Sheng, Z.; He, M. Spectral analysis of gravity waves from near space high-resolution balloon data in Northwest China. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, L.; Chen, R.; Fu, W.; Xu, B.; Jiang, P.; Han, Y. Refining the empirical global pressure and temperature model with the ERA5 reanalysis and radiosonde data. J. Geod. 2021, 95, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Song, J.; Zheng, Z.; Han, Q.L. A survey on modelling, control and challenges of stratospheric airships. Control. Eng. Pract. 2022, 119, 104979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Sheng, Z.; Fan, Z.; Liao, Q. Data analysis of the TK-1G sounding rocket installed with a satellite navigation system. Atmosphere 2017, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S.; Podesta, M.D. Response times of meteorological air temperature sensors. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 2789–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, S.A.P.; Slingerland, J.D.; Van de Giesen, N.C. Fiber optic distributed temperature sensing for the determination of air temperature. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2015, 8, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Xie, W.; Wang, X.; Chen, C. Simulation and analysis of fluid–solid–thermal unidirectional coupling of near-space airship. Aerospace 2022, 9, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Oran, E.S. New principle for aerodynamic heating. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2018, 5, 606–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursultanov, N.; Heffernan, W.J.B.; van Herel, M.J.W.M.R.; Nijdam, J.J. Computational calculation of temperature and electrical resistance to control Joule heating of green Pinus radiata logs. Appl. Ther. Eng. 2019, 159, 113855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Baker, J. Multimode heat transfer in a near-space environment. Heat Transfer Eng. 2010, 31, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Mei, X. Radiation environment study of near space in China area. In Proceedings of the Remote Sensing of Clouds and the Atmosphere XX, Toulouse, France, 16 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.W.; Yang, I.; Choi, B.I.; Kim, S.; Woo, S.B.; Kang, W.; Oh, Y.K.; Park, S.; Yoo, J.; Kim, J.C.; et al. Development of upper air simulator for the calibration of solar radiation effects on radiosonde temperature sensors. Meteorol. Appl. 2020, 27, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Yuan, J.; Zhu, H. Research on temperature measurement technology of platinum film thermistor. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2021, 1907, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žužek, V.; Batagelj, V.; Bojkovski, J. Determination of PRT Hysteresis in the Temperature Range from −50℃ to 300℃. Int. J. Thermophys. 2010, 31, 1771–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, J.A.; Chen, S. Thermal hysteresis analysis of MEMS pressure sensors. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2005, 14, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, S.B.; Palha, J.M.; Fernandes, H.C.; Souto, M.R.; Pimenta, S.; Dong, T.; Yang, Z.; Ribeiro, J.; Correia, J.H. LED optrode with integrated temperature sensing for optogenetics. Micromachines 2018, 9, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandpal, M.; Shirhatti, V.; Singh, J.; Sontakke, B.A.; Jejusaria, A.; Arora, S.P.S.; Singh, S. Experimental study of chromium oxide thin films as an intermediate layer for Pt-based temperature sensor applications. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 21287–21296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Zhao, X.; Gu, S.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Deng, X.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, W. Pt thin-film resistance temperature detector on flexible Hastelloy tapes. Vacuum 2021, 184, 109966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.M.; Zhao, L.B.; Han, X.G.; Jia, C.; Gao, Y.; Fan, S.; Yang, P.; Dong, L.; Jiang, Z.D. MEMS-based Pt film temperature sensor chip on silicon substrate. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2022, 33, 125113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakawa, N.; Legner, W.; Ziemann, T.; Telitschkin, D.; Fecht, H. J.; Friedberger, A. Microthruster with integrated platinum thin film resistance temperature detector (RTD), heater, and thermal insulation. In Proceedings of the Smart Sensors, Actuators, and MEMS V, Ulm, Germany, 5 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Babita; Pant, U.; Meena, H.; Gupta, G.; Bapna, K.; Shivagan, D.D. Evaluation of self-heating effect in platinum resistance thermometers. Measurement 2022, 203, 111994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, Q.; Han, X.; Dai, W.; Yang, J. An E-type temperature sensor for upper air meteorology. Nanotechnol. Precis. Eng. 2018, 1, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Philipona, R.; Kräuchi, A.; Romanens, G.; Levrat, G.; Ruppert, P.; Brocard, E.; Jeannet, P.; Ruffieux, D.; Calpini, B. Solar and thermal radiation errors on upper-air radiosonde temperature measurements. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2013, 30, 2382–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Park, E.U.; Choi, B.I.; Kim, J.C.; Woo, S.B.; Kang, W.; Park, S.; Yang, S.D.; Kim, Y.G. Compensation of solar radiation and ventilation effects on the temperature measurement of radiosondes using dual thermistors. Meteorol. Appl. 2018, 25, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsad, S.; Ardekani, M.A.; Farhani, F. Experimental investigation of aerodynamic effects of probe on heat transfer from hot-wire sensors at vertical and horizontal orientations. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2019, 70, 101642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, F. Using nanometer platinum films as temperature sensors (constraints from experimental, mathematical, and finite-element analysis). IEEE Sens. J. 2009, 9, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, M.D.; Clark, P.; Thompson, K.; Wilson, Z.; Wilson, J.; Adams, C. Multicore fiber temperature sensor with fast response times. OSA Continuum 2018, 1, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrienko, Y.; Zakharov, A.; Koryakov, M. Coupled problems of high-speed aerodynamics and thermomechanics of heat-shielding structures. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2018, 1141, 012094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Yang, J. High-speed and accurate non-linear calibration of temperature sensors for transient aerodynamic heating experiments. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2014, 36, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Altitude (m) |

Falling speed (m/s) |

Ambient temperature (K) |

Air pressure (Pa) |

Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70000 | 100 | 217.452 | 5.01699 | 0 |

| 61724 | 310.35 | 240.63 | 15.94 | 35.41 |

| 60000 | 304.34 | 245.45 | 20.31 | 40.97 |

| 50000 | 166.31 | 270.65 | 75.95 | 84.23 |

| 40000 | 77.76 | 251.05 | 277.55 | 174.27 |

| 30000 | 35.19 | 226.65 | 1171.95 | 370.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).