Submitted:

18 April 2023

Posted:

19 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance of self-regulation during infancy and life outcomes.

1.2. Attention as the foundational basis for self-regulation.

1.3. Impact of the rearing environment on self-regulatory abilities.

1.4. Using machine-learning to understand the multiplicity of factors contributing to the development of self-regulation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Apparatus

2.3. Experimental tasks

2.3.1. Gap-overlap task

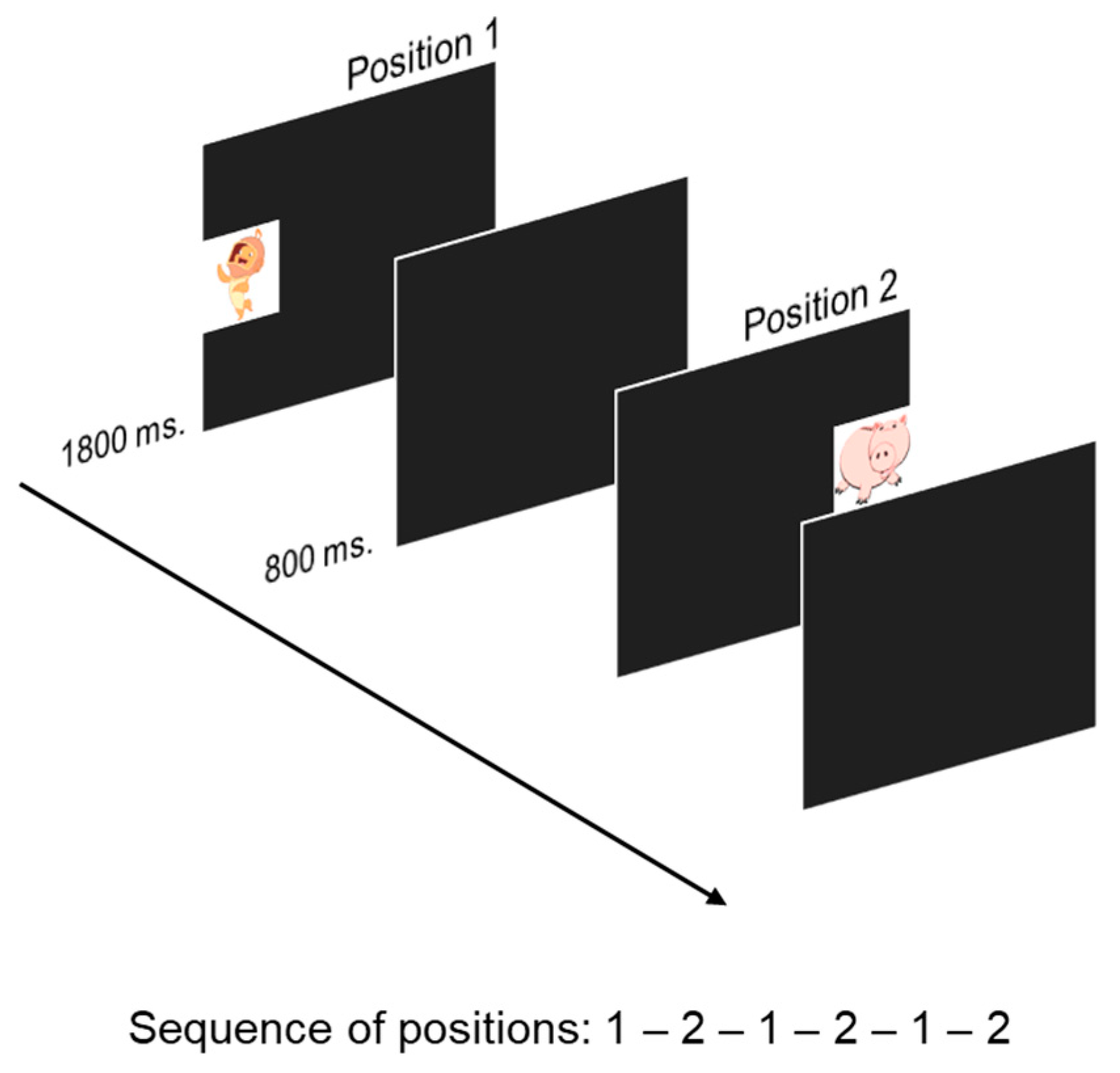

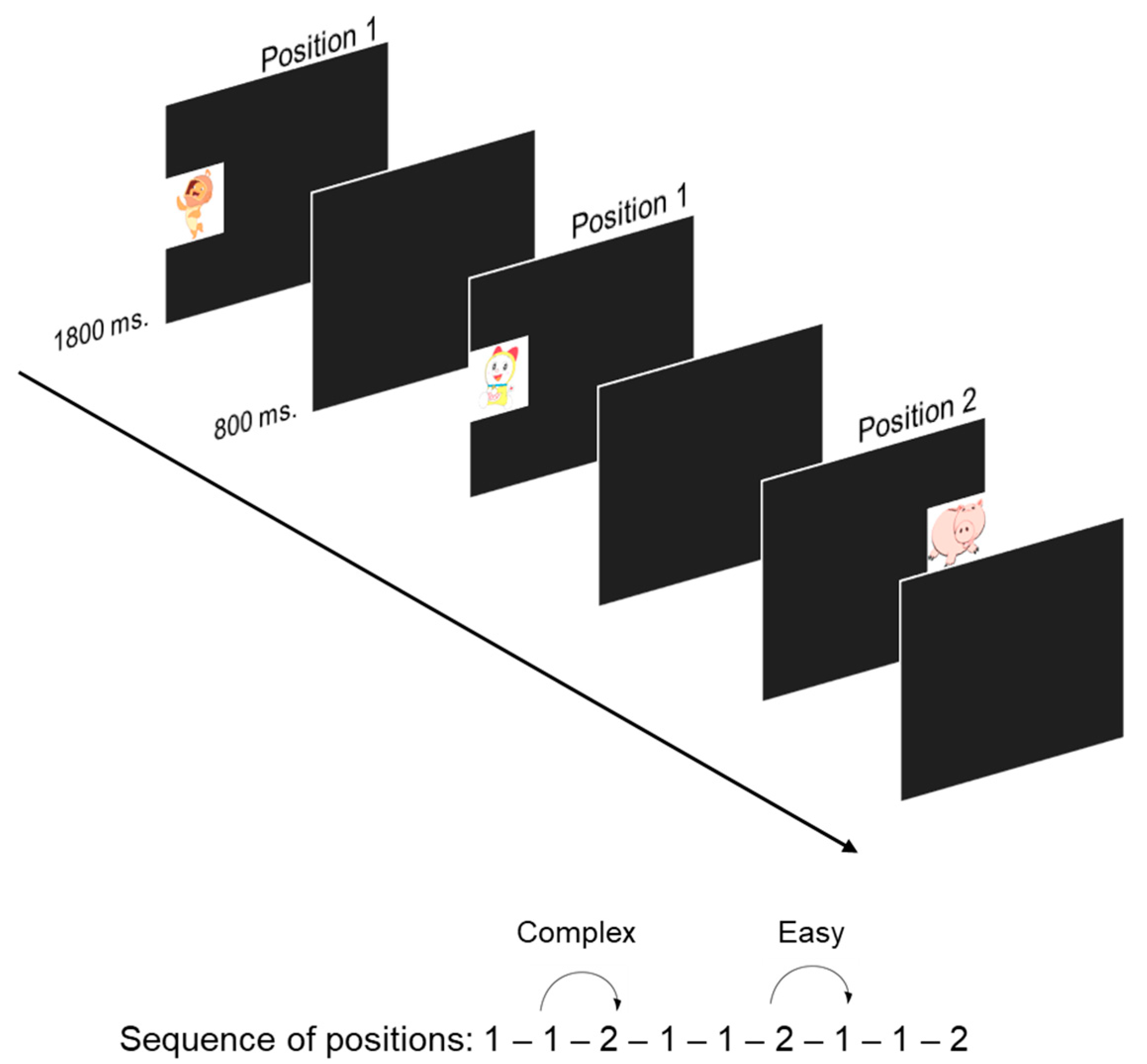

2.3.2. Visual Sequence-Learning (VSL)

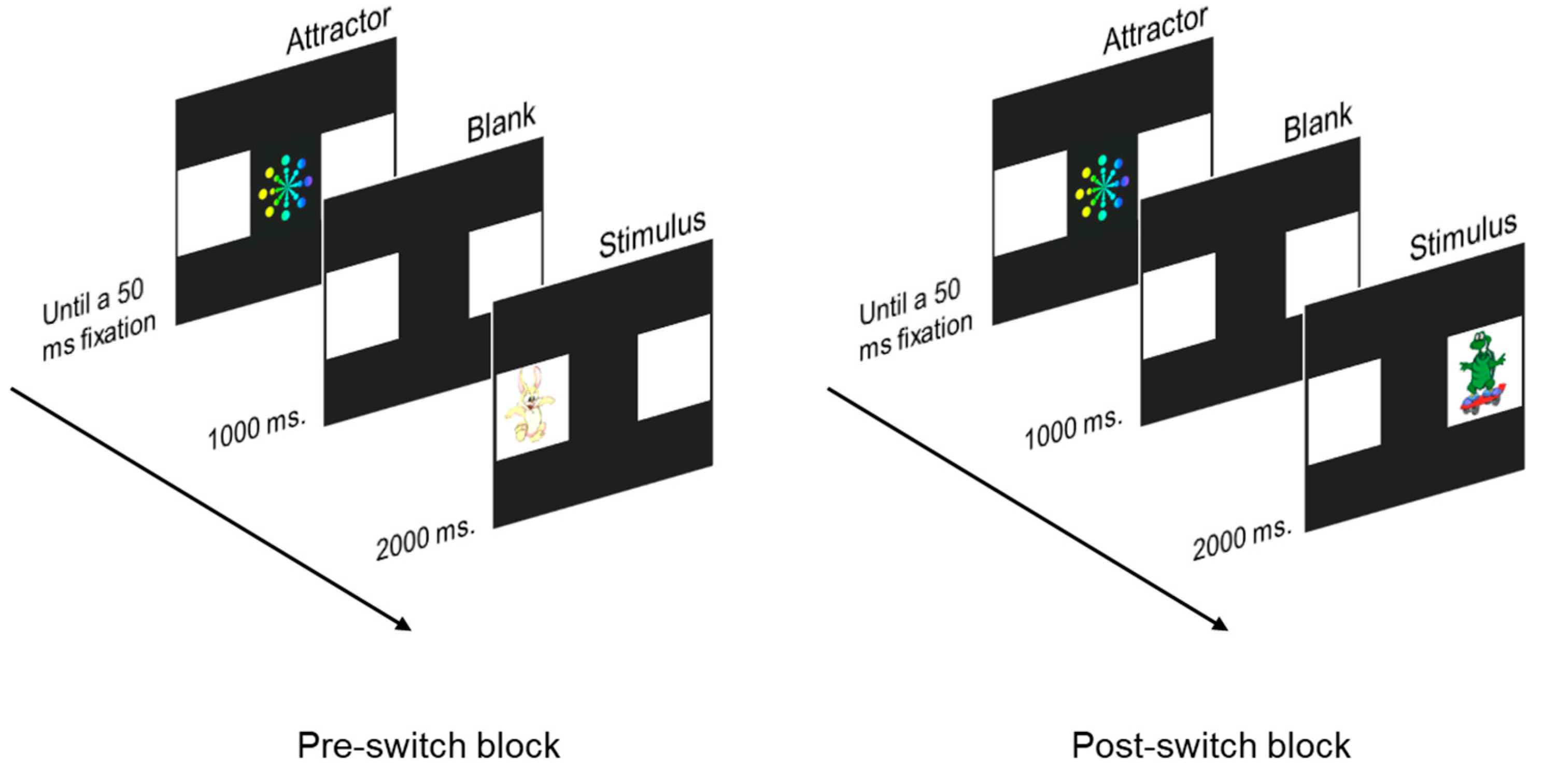

2.3.3. Switching task

2.3.4. Toy prohibition task

2.4. Questionnaires

2.4.1. Socioeconomic Status

2.4.2. Confusion, Hubbub and Order Scale (CHAOS)

2.4.3. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

2.4.3. Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ)

2.5. Procedure

| Age of measurement | Task/Questionnaire | Variable | Construct |

| 6 months | Gap-overlap | mdSL overlap | Attentional disengagement |

| mdSL gap | Attentional orienting | ||

| Switching | Perseverations (post-switch) | Attentional flexibility | |

| VSL | Reactive looks | Reactive attention | |

| Correct anticipations | Anticipatory attention | ||

| 9 months | Complex correct anticipations | Anticipatory attention + monitoring | |

| Toy prohibition | Touch time | Self-regulation | |

| 6 months | SES | SES index | Family general socioeconomic status |

| Mother’s education | Parent’s education level | ||

| Father’s education | |||

| Mother’s occupation | Parent’s occupational level | ||

| Father’s occupation | |||

| CHAOS | Chaos | Household disorganization | |

| BDI | Maternal depression | Maternal depressive symptomatology | |

| 36 months | CBQ | Effortful Control* | Children’s self-regulated behavior |

2.6. Analysis procedure

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robson, D.A.; Allen, M.S.; Howard, S.J. Self-Regulation in Childhood as a Predictor of Future Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 324–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, M.R.; Checa, P.; Rothbart, M.K. Contributions of Attentional Control to Socioemotional and Academic Development. Early Educ. Dev. 2010, 21, 744–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, N.P.; Hume, L.E.; Allan, D.M.; Farrington, A.L.; Lonigan, C.J. Relations between Inhibitory Control and the Development of Academic Skills in Preschool and Kindergarten: A Meta-Analysis. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 2368–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smithers, L.G.; Sawyer, A.C.P.; Chittleborough, C.R.; Davies, N.M.; Smith, G.D.; Lynch, J.W. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Effects of Early Life Non-Cognitive Skills on Academic, Psychosocial, Cognitive and Health Outcomes. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Bettis, A.H.; Watson, K.H.; Gruhn, M.A.; Dunbar, J.P.; Williams, E.; Thigpen, J.C. Coping, Emotion Regulation, and Psychopathology in Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-Analysis and Narrative Review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 939–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, T.C.; Turanovic, J.J.; Fox, K.A.; Wright, K.A. Self-Control and Victimization: A Meta-Analysis. Criminology 2014, 52, 87–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L.; Belsky, D.; Dickson, N.; Hancox, R.J.; Harrington, H.; Houts, R.; Poulton, R.; Roberts, B.W.; Ross, S.; et al. A Gradient of Childhood Self-Control Predicts Health, Wealth, and Public Safety. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 2693–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothbart, M.K. Temperament and the Pursuit of an Integrated Developmental Psychology. Merrill. Palmer. Q. 2004, 50, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C.; Raver, C.C. Poverty, Stress, and Brain Development: New Directions for Prevention and Intervention. Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16, S30–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes-Aitken, A.; Braren, S.; Swingler, M.; Voegtline, K.; Blair, C. Sustained Attention in Infancy: A Foundation for the Development of Multiple Aspects of Self-Regulation for Children in Poverty. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2019, 184, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M.K.; Ellis, L.K.; Rueda, M.R.; Posner, M.I. Developing Mechanisms of Temperamental Effortful Control. J. Pers. 2003, 71, 1113–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, M.R. Effortful Control. In Handbook of temperament; Marcel Zentner, Rebecca L. Shiner, Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, 2012; pp. 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, M.R.; Posner, M.I.; Rothbart, M.K. Attentional Control and Self-Regulation. In Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, theory and applications; Vohs, K.D., Baumeister, R.F., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, 2011; pp. 284–299. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, M.R.; Moyano, S.; Rico-Picó, J. Attention: The Grounds of Self-Regulated Cognition. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2021, e1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, M.A.; Deater-Deckard, K. Biological Systems and the Development of Self-Regulation: Integrating Behavior, Genetics, and Psychophysiology. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2007, 28, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, S.E.; Posner, M.I. The Attention System of the Human Brain: 20 Years After. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothbart, M.K.; Rueda, M.R. The Development of Effortful Control. In Developing individuality in the human brain: A tribute to Michael I. Posner; Mayr, U., Awh, E., Keele, S.W., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, D.C, 2005; ISBN 1-59147-210-5. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, M.I.; Rothbart, M.K. Attention, Self-Regulation and Consciousness. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 1998, 353, 1915–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, C.; Rothbart, M.K.; Posner, M.I. Distress and Attention Interactions in Early Infancy. Motiv. Emot. 1997, 21, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg, S.C.; Leerkes, E.M. Infant and Maternal Behaviors Regulate Infant Reactivity to Novelty at 6 Months. Dev. Psychol. 2004, 40, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.H.; Posner, M.I.; Rothbart, M.K. Components of Visual Orienting in Early Infancy: Contingency Learning, Anticipatory Looking, and Disengaging. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1991, 3, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, B.A.; Bryson, S.E. Visual Attention and Temperament: Developmental Data from the First 6 Months of Life. Infant Behav. Dev. 2005, 28, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, A.; Sukigara, M. Individual Differences in Disengagement of Fixation and Temperament: Longitudinal Research on Toddlers. Infant Behav. Dev. 2013, 36, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheese, B.E.; Rothbart, M.K.; Posner, M.I.; White, L.K.; Fraundorf, S.H. Executive Attention and Self-Regulation in Infancy. Infant Behav. Dev. 2008, 31, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochanska, G.; Murray, K.T.; Harlan, E.T. Effortful Control in Early Childhood: Continuity and Change, Antecedents, and Implications for Social Development. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 36, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, N.B.; Swingler, M.M.; Calkins, S.D.; Bell, M.A. Neurophysiological Correlates of Attention Behavior in Early Infancy: Implications for Emotion Regulation during Early Childhood. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2016, 142, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geeraerts, S.B.; Hessels, R.S.; Van der Stigchel, S.; Huijding, J.; Endendijk, J.J.; Van den Boomen, C.; Kemner, C.; Deković, M. Individual Differences in Visual Attention and Self-Regulation: A Multimethod Longitudinal Study from Infancy to Toddlerhood. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2019, 180, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papageorgiou, K.A.; Smith, T.J.; Wu, R.; Johnson, M.H.; Kirkham, N.Z.; Ronald, A. Individual Differences in Infant Fixation Duration Relate to Attention and Behavioral Control in Childhood. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papageorgiou, K.A.; Farroni, T.; Johnson, M.H.; Smith, T.J.; Ronald, A. Individual Differences in Newborn Visual Attention Associate with Temperament and Behavioral Difficulties in Later Childhood. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackey, A.P.; Raizada, R.D.S.; Bunge, S.A. Environmental Influences on Prefrontal Development. In Principles of Frontal Lobe Function; Stuss, D.T., Knight, R.T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2013; pp. 145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Brandes-Aitken, A.; Braren, S.; Vogel, S.C.; Perry, R.E.; Brito, N.H.; Blair, C. Within-Person Changes in Basal Cortisol and Caregiving Modulate Executive Attention across Infancy. Dev. Psychopathol. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conejero, Á.; Rueda, M.R. Infant Temperament and Family Socio-Economic Status in Relation to the Emergence of Attention Regulation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipina, S.J.; Martelli, M.I.; Vuelta, B.; Colombo, J.A. Performance on the A-Not-B Task of Argentinean Infants from Unsatisfied and Satisfied Basic Needs Homes. Rev. Interam. Psicol. J. Psychol. 2005, 39, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Musso, M.F.; Richaud, M.C.; Cascallar, E.C. Self-Regulation and Executive Functions: Understanding Learning and School Performance. Cogn. Psychol. Learn. Process. 2015, 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lipina, S.J.; Evers, K. Neuroscience of Childhood Poverty: Evidence of Impacts and Mechanisms as Vehicles of Dialog With Ethics. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, C. Stress and the Development of Self-Regulation in Context. Child Dev. Perspect. 2010, 4, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, P.; Evans, G.W.; Angstadt, M.; Ho, S.S.; Sripada, C.S.; Swain, J.E.; Liberzon, I.; Phan, K.L. Effects of Childhood Poverty and Chronic Stress on Emotion Regulatory Brain Function in Adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 18442–18447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberzon, I.; Ma, S.T.; Okada, G.; Shaun Ho, S.; Swain, J.E.; Evans, G.W. Childhood Poverty and Recruitment of Adult Emotion Regulatory Neurocircuitry. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raver, C.C.; Blair, C.; Garrett-Peters, P.; Vernon-Feagans, L.; Greenberg, M.; Cox, M.; Burchinal, P.; Willoughby, M.; Mills-Koonce, R.; Ittig, M. Poverty, Household Chaos, and Interparental Aggression Predict Children’s Ability to Recognize and Modulate Negative Emotions. Dev. Psychopathol. 2015, 27, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheny, A.P.; Wachs, T.D.; Ludwig, J.L.; Phillips, K. Bringing Order out of Chaos: Psychometric Characteristics of the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 1995, 16, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.A.; Petrill, S.A.; Deater Deckard, K.; Thompson, L.A. SES and CHAOS as Environmental Mediators of Cognitive Ability: A Longitudinal Genetic Analysis. Intelligence 2007, 35, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrill, S.A.; Pike, A.; Price, T.; Plomin, R. Chaos in the Home and Socioeconomic Status Are Associated with Cognitive Development in Early Childhood: Environmental Mediators Identified in a Genetic Design. Intelligence 2004, 32, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente, C.; Lemery-Chalfant, K.; Reiser, M. Pathways to Problem Behaviors: Chaotic Homes, Parent and Child Effortful Control, and Parenting. Soc. Dev. 2007, 16, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, K.; Atkinson, L.; Harris, M.; Gonzalez, A. Examining the Effects of Household Chaos on Child Executive Functions: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 147, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecheile, B.M.; Spinrad, T.L.; Xu, X.; Lopez, J.; Eisenberg, N. Longitudinal Relations among Household Chaos, SES, and Effortful Control in the Prediction of Language Skills in Early Childhood. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernon-Feagans, L.; Willoughby, M.; Garrett-Peters, P. Predictors of Behavioral Regulation in Kindergarten: Household Chaos, Parenting, and Early Executive Functions. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woody, C.A.; Ferrari, A.J.; Siskind, D.J.; Whiteford, H.A.; Harris, M.G. A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression of the Prevalence and Incidence of Perinatal Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 219, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyl, D.D.; Roggman, L.A.; Newland, L.A. Stress, Maternal Depression, and Negative Mother-Infant Interactions in Relation to Infant Attachment. Infant Ment. Health J. 2002, 23, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, P.B.; Gelfand, D.M.; Kulcsar, E.; Teti, D.M. Mother-Toddler Interaction Patterns Associated with Maternal Depression. Dev. Psychopathol. 1997, 9, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackman, D.A.; Farah, M.J.; Meaney, M.J. Socioeconomic Status and the Brain: Mechanistic Insights from Human and Animal Research. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.; Joung, Y.S.; Baek, J.; Yoo, N.H. Maternal Depression Trajectories and Child Executive Function over 9 Years. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckman-Westin, E.; Cohen, P.R.; Stueve, A. Maternal Depression and Mother-Child Interaction Patterns: Association with Toddler Problems and Continuity of Effects to Late Childhood. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2009, 50, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.; Roman, G.; Hart, M.J.; Ensor, R. Does Maternal Depression Predict Young Children’s Executive Function? A 4-Year Longitudinal Study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2013, 54, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, S.M.; Mâsse, L.C.; Brain, U.; Oberlander, T.F. A 6-Year Longitudinal Study: Are Maternal Depressive Symptoms and Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) Antidepressant Treatment during Pregnancy Associated with Everyday Measures of Executive Function in Young Children? Early Hum. Dev. 2019, 128, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, J.T. Annual Research Review: On the Relations among Self-Regulation, Self-Control, Executive Functioning, Effortful Control, Cognitive Control, Impulsivity, Risk-Taking, and Inhibition for Developmental Psychopathology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2017, 58, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, M.J.; Mills-Koonce, R.; Propper, C.; Gariépy, J.L. Systems Theory and Cascades in Developmental Psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S.; Cicchetti, D. Developmental Cascades. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everson, H.T. Modeling the Student in Intelligent Tutoring Sytems: The Promise of a New Psychometrics. Instr. Sci. 1995, 23, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascallar, E.; Boekaerts, M.; Costigan, T. Assessment in the Evaluation of Self-Regulation as a Process. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, M.F.; Hernández, C.F.R.; Cascallar, E.C. Predicting Key Educational Outcomes in Academic Trajectories: A Machine-Learning Approach. High. Educ. 2020, 80, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SR Research EyeLink 1000 Plus User Manual 2013.

- SR Research SR Research Experiment Builder User Manual 2017.

- SR Research EyeLink Data Viewer User Manual 2017.

- Hessels, R.S.; Niehorster, D.C.; Kemner, C.; Hooge, I.T.C. Noise-Robust Fixation Detection in Eye Movement Data: Identification by Two-Means Clustering (I2MC). Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 1802–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmboe, K.; Bonneville-Roussy, A.; Csibra, G.; Johnson, M.H. Longitudinal Development of Attention and Inhibitory Control during the First Year of Life. Dev. Sci. 2018, e12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, S.; Rico-Picó, J.; Conejero, Á.; Hoyo, Á.; Ballesteros-Duperón, M.A.; Rueda, M.R. Influence of the Environment on the Early Development of Attentional Control. PsyArXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csibra, G.; Tucker, L.A.; Johnson, M.H. Neural Correlates of Saccade Planning in Infants: A High-Density ERP Study. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1998, 29, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clohessy, A.B.; Posner, M.I.; Rothbart, M.K. Development of the Functional Visual Field. Acta Psychol. (Amst). 2001, 106, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haith, M.M.; Hazan, C.; Goodman, G.S. Expectation and Anticipation of Dynamic Visual Events by 3.5-Month-Old Babies; 1988.

- Canfield, R.L.; Haith, M.M. \bung Infants’ Visual Expectations for Symmetric and Asymmetric Stimulus Sequences; 1991; Vol. 27.

- Rothbart, M.K.; Ellis, L.K.; Rueda, M.R.; Posner, M.I. Developing Mechanisms of Temperamental Effortful Control. J. Pers. 2003, 71, 1113–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, A.M.; Mehler, J. Cognitive Gains in 7-Month-Old Bilingual Infants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 6556–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, A.; Greenhalgh, I.; Bailey, R.; Fiske, A.; Dvergsdal, H.; Holmboe, K. Development of Directed Global Inhibition, Competitive Inhibition and Behavioural Inhibition during the Transition between Infancy and Toddlerhood. Dev. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyano, S.; Conejero, Á.; Fernández, M.; Serrano, F.; Rueda, M.R. Development of Visual Attention Control in Early Childhood: Associations with Temperament and Home Environment. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II; Psychological Corportation: San Antonio, TX, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart, M.K.; Ahadi, S.A.; Hershey, K.L.; Fisher, P. Investigations of Temperament at Three to Seven Years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1394–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G.D. Neural Network Models; Statistical Associates Publishers, 2014.

- Somers, M.J.; Casal, J.C. Somers, M.J.; Casal, J.C. Using Artificial Neural Networks to Model Nonlinearity. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428107309326 2008, 12, 403–417. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, C.F.; Musso, M.; Kyndt, E.; Cascallar, E. Artificial Neural Networks in Academic Performance Prediction: Systematic Implementation and Predictor Evaluation. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykin, S. Neural Networks and Learning Machines; Pearson, 2009; Vol. 3; ISBN 9780131471399.

- Attoh-Okine, N.O. Analysis of Learning Rate and Momentum Term in Backpropagation Neural Network Algorithm Trained to Predict Pavement Performance. Adv. Eng. Softw. 1999, 30, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M.K.; Sheese, B.E.; Rueda, M.R.; Posner, M.I. Developing Mechanisms of Self-Regulation in Early Life. Emot. Rev. 2011, 3, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekaerts, M.; Musso, M.F.; Cascallar, E.C. Predicting Attribution of Letter Writing Performance in Secondary School: A Machine Learning Approach. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascallar, E.; Musso, M.; Kyndt, E.; Dochy, F. Modelling for Understanding AND for Prediction / Classification - the Power of Neural Networks in Research. Front. Learn. Res. 2015, 2, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golino, H.; Gomes, C.M.A. Four Machine Learning Methods to Predict Academic Achievement of College Students : A Comparison Study. Rev. Electrónica Psicol. 2014, 1, 68–101. [Google Scholar]

- Musso, M.; Kyndt, E.; Cascallar, E.; Dochy, F. Predicting Mathematical Performance: The Effect of Cognitive Processes and Self-Regulation Factors. Educ. Res. Int. 2012, 2012, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, M.F.; Kyndt, E.; Cascallar, E.C.; Dochy, F. Predicting General Academic Performance and Identifying the Differential Contribution of Participating Variables Using Artificial Neural Networks. Front. Learn. Res. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, M.F.; Cómbita, L.M.; Cascallar, E.C.; Rueda, M.R. Modeling the Contribution of Genetic Variation to Cognitive Gains Following Training with a Machine Learning Approach. Mind, Brain Educ. 2022, 16, 300–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, A.; Johnson, M.H.; Holmboe, K. Early Development of Visual Attention: Change, Stability, and Longitudinal Associations. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 1, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, M.R.; Conejero, A. Developing Attention and Self-Regulation in Infancy and Childhood. In Neural Circuit and Cognitive Development; Rubenstein, J., Rakic, P., Chen, B., Kwan, K.Y., Zeng, H., Tager-Flusberg, H., Eds.; Academic Press: London, 2020; pp. 505–522. [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta, M.; Shulman, G.L. Control of Goal-Directed and Stimulus-Driven Attention in the Brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M.K.; Ahadi, S.A. Temperament and the Development of Personality. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1994, 103, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clearfield, M.W.; Diedrich, F.J.; Smith, L.B.; Thelen, E. Young Infants Reach Correctly in A-Not-B Tasks: On the Development of Stability and Perseveration. Infant Behav. Dev. 2006, 29, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Development of the Ability to Use Recall to Guide Action, as Indicated by Infants’ Performance on AB. Child Dev. 1985, 56, 868–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, K.; Bell, M.A. Developmental Progression of Looking and Reaching Performance on the A-Not-b Task. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 46, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farah, M.J.; Shera, D.M.; Savage, J.H.; Betancourt, L.; Giannetta, J.M.; Brodsky, N.L.; Malmud, E.K.; Hurt, H. Childhood Poverty: Specific Associations with Neurocognitive Development. Brain Res. 2006, 1110, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, K.G.; McCandliss, B.D.; Farah, M.J. Socioeconomic Gradients Predict Individual Differences in Neurocognitive Abilities. Dev. Sci. 2007, 10, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W.; Cohen, S. Environmental Stress. Encycl. Appl. Psychol. Three-Volume Set 2004, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.H.; Corwyn, R.F.; McAdoo, H.P.; Coll, C.G. The Home Environments of Children in the United States Part I: Variations by Age, Ethnicity, and Poverty Status. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1844–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, G.M.; Hook, C.J.; Farah, M.J. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Socioeconomic Status and Executive Function Performance among Children. Dev. Sci. 2018, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deater-Deckard, K. Family Matters: Intergenerational and Interpersonal Processes of Executive Function and Attentive Behavior. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. Black Holes and the Information Paradox. Sci. Am. 1997, 276, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Information in the Holographic Universe. Sci. Am. 2003, 289, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckstein, A.M.; Holt, R.J.; Netravali, A.N. Holographic Representations of Images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1998, 7, 1583–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigato, S.; Stets, M.; Bonneville-Roussy, A.; Holmboe, K. Impact of Maternal Depressive Symptoms on the Development of Infant Temperament: Cascading Effects during the First Year of Life. Soc. Dev. 2020, 29, 1115–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigato, S.; Charalambous, S.; Stets, M.; Holmboe, K. Maternal Depressive Symptoms and Infant Temperament in the First Year of Life Predict Child Behavior at 36 Months of Age. Infant Behav. Dev. 2022, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checa, P.; Rodríguez-Bailón, R.; Rueda, M.R. Neurocognitive and Temperamental Systems of Self-regulation and Early Adolescents’ Social and Academic Outcomes. Mind, Brain Educ. 2008, 2, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 6 months | 9 months | 36 months | |

| n | 142 (73 female) | 122 (60 female) | 92 (46 female) |

| Age (days) | 193.80 (8.49) | 284.75 (9.21) | 1119.09 (18.42) |

| Weight at birth | 3354.87 (472.43) | - | - |

| Gestational weeks | 39.65 (1.38) | - | - |

| Topology | Attention model | Environment model | Combined model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Training Set Data Testing Set Data |

76.1%; n=35 | 78.3%; n=36 | 77.8%; n=42 | 81.8%; n=45 | 87.9%; n=29 | 69.7%; n=23 | |||

| 23.9%; n=11 | 21.7%; n=10 | 22.2%; n=12 | 18.2%; n=10 | 12.1%; n=4 | 30.3%; n=10 | ||||

|

Cross-entropy error Stopping error |

15.243 | 10.073 | 15.888 | 12.397 | .015 | .146 | |||

| 1 consecutive step with no decrease in error | 1 consecutive step with no decrease in error | 1 consecutive step with no decrease in error | |||||||

| Number of input nodes | 7 | 31 | 32 | 37 | |||||

| Number of output units | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Number of hidden layers | 1 hidden layer with 2 units |

1 hidden layer with 1 unit |

1 hidden layer with 5 units |

1 hidden layer with 1 unit |

|||||

| Number of epochs for training | 10 | 10 | 10 | ||||||

| Method for rescaling covariates | Standardized method | Standardized method | Standardized method | ||||||

| Activation function for hidden layers | Hyperbolic tangent | Hyperbolic tangent | Hyperbolic tangent | ||||||

| Activation and error function for output layer | Softmax. cross- entropy. |

Softmax. cross-entropy |

Softmax. cross-entropy |

||||||

| Methodology in the training phase | Online (one case by cycle) | Online | Online | ||||||

| Parameters | Initial learning rate= .1 Momentum= .9 Optimization algorithm: gradient descent Minimum relative change in training error= .0001 |

Initial learning rate= .04Momentum= 1.2 Optimization algorithm: gradient descent Minimum relative change in training error= .0001 |

Initial learning rate= .4 Momentum= .9 Optimization algorithm: gradient descent Minimum relative change in training error= .0001 |

Initial learning rate= .0004 Momentum= 1.5 Optimization algorithm: gradient descent Minimum relative change in training error= .0001 |

Initial learning rate= .6 Momentum= .7 Optimization algorithm: gradient descent Minimum relative change in training error= .0001 |

Initial learning rate= .8 Momentum= .5Optimization algorithm: gradient descent Minimum relative change in training error= .0001 |

|||

| Task/Questionnaire | Variable | M (SD) |

| Gap-overlap | mdSL overlap (ms) | 451.84 (100.40) |

| mdSL gap (ms) | 275.59 (30.18) | |

| Switching | Perseverations (post-switch; %) | 68.41 (34.14) |

| VSL | Reactive looks (%) | 88.31 (11.19) |

| Correct anticipations (%) | 11.51 (10.89) | |

| Complex correct anticipations (%) | 22.54 (27.50) | |

| Toy prohibition | Touch time (s) | 5.91 (6.38) |

| SES | SES index (z-score) | .08 (.82) |

| Mother’s education | 4.10 (1.54) | |

| Father’s education | 3.49 (1.72) | |

| Mother’s occupation | 3.88 (3.38) | |

| Father’s occupation | 4.59 (2.73) | |

| CHAOS | Chaos | 41.09 (13.07) |

| BDI | Maternal depression | 10.74 (7.43) |

| CBQ | Effortful control | 4.91 (.57) |

| Measures | Attention model | Environment model | Combined model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NN1 | NN2 | NN1 | NN2 | NN1 | NN2 | |||||||

| Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | |

| Accuracy for “Low-EC” group (TP): Sensitivity/Recall. | .82 | .75 | .82 | .75 | .64 | .50 | .67 | .50 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Accuracy for “the rest” group (TN): Specificity. | .79 | 1 | .88 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .97 | .83 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Overall Accuracy | .80 | .91 | .86 | .90 | .88 | .91 | .88 | .70 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Precision | .64 | 1 | .75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .89 | .67 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| F1 score | .72 | .86 | .78 | .86 | .78 | .67 | .76 | .57 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| AUC | .87 | .96 | .75 | .93 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

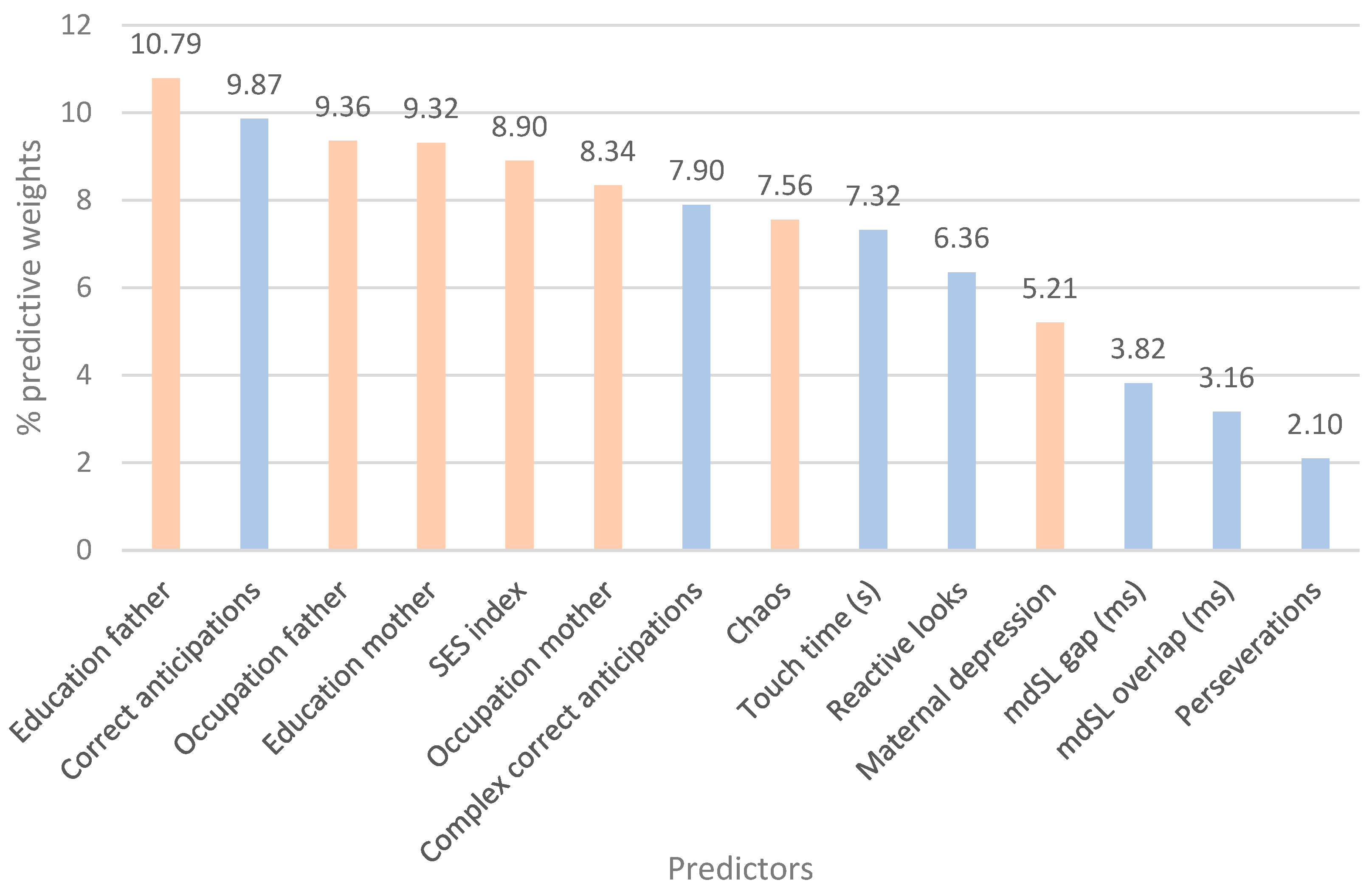

| Attentional predictors |

Importance | Environmental predictors |

Importance | Attentional + environmental predictors |

Importance |

| Correct anticipations | 0.19 | Maternal depression | 0.23 | Education father | 0.11 |

| mdSL overlap (ms) | 0.19 | Education father | 0.19 | Correct anticipations | 0.10 |

| Reactive looks | 0.18 | Occupation father | 0.17 | Occupation father | 0.09 |

| mdSL gap (ms) | 0.16 | Occupation mother | 0.14 | Education mother | 0.09 |

| Perseverations | 0.11 | Education mother | 0.14 | SES index | 0.09 |

| Complex correct anticipations | 0.10 | Chaos | 0.08 | Occupation mother | 0.08 |

| Touch time (s) | 0.07 | SES index | 0.06 | Complex correct anticipations | 0.08 |

| Chaos | 0.08 | ||||

| Touch time (s) | 0.07 | ||||

| Reactive looks | 0.06 | ||||

| Maternal depression | 0.05 | ||||

| mdSL gap (ms) | 0.04 | ||||

| mdSL overlap (ms) | 0.03 | ||||

| Perseverations | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).