Submitted:

14 April 2023

Posted:

17 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

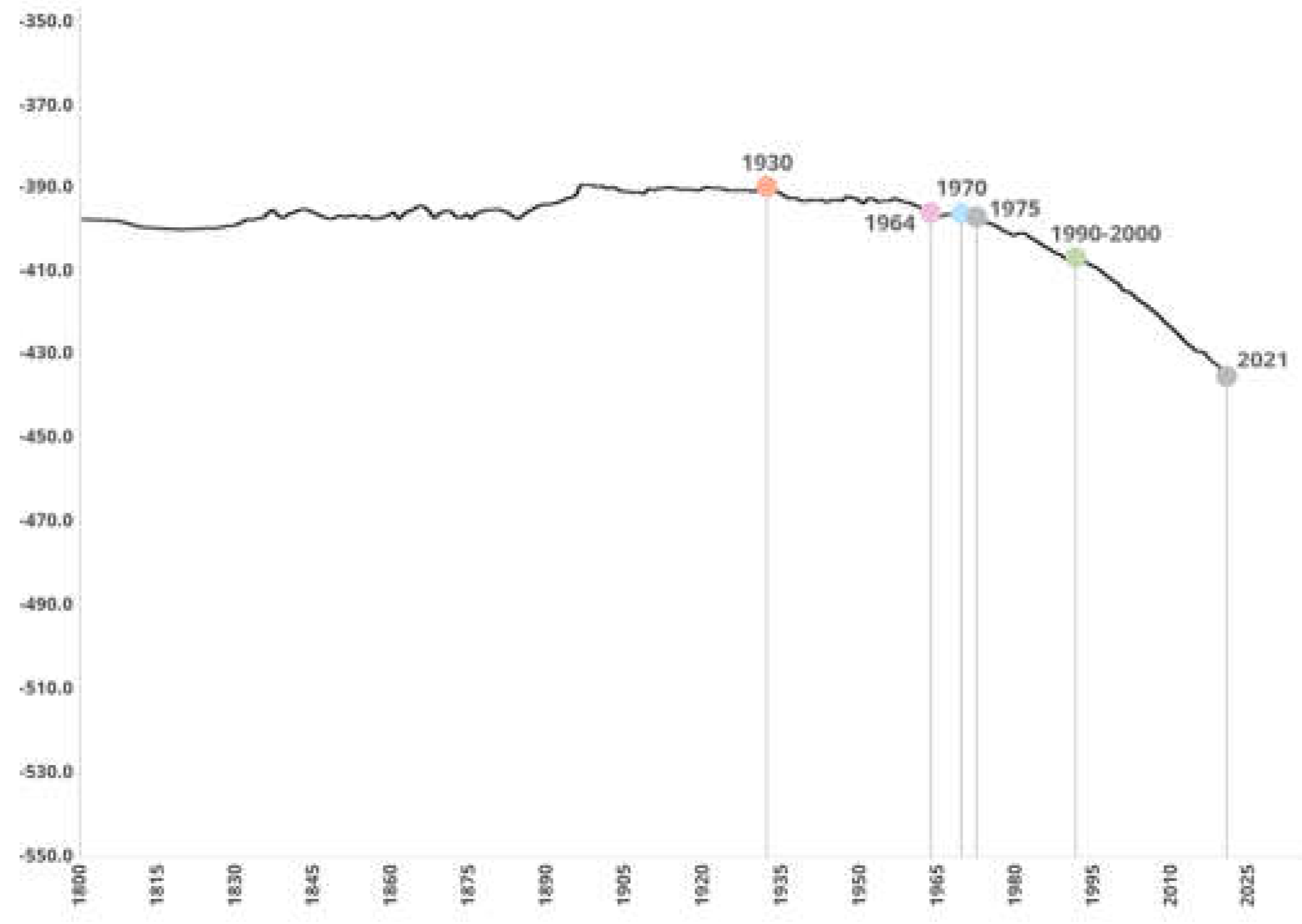

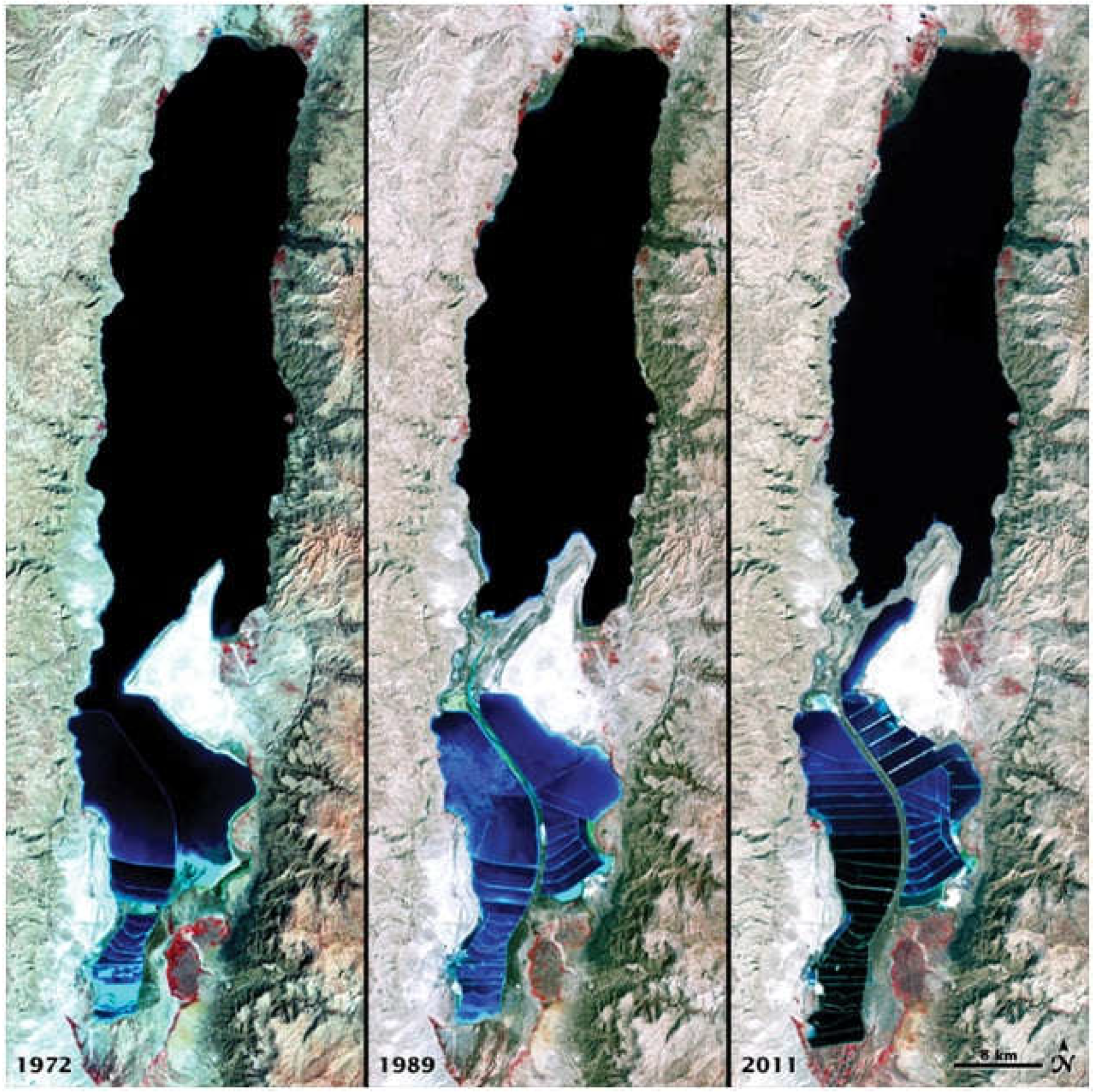

2. Dead Sea Review

2. Methods

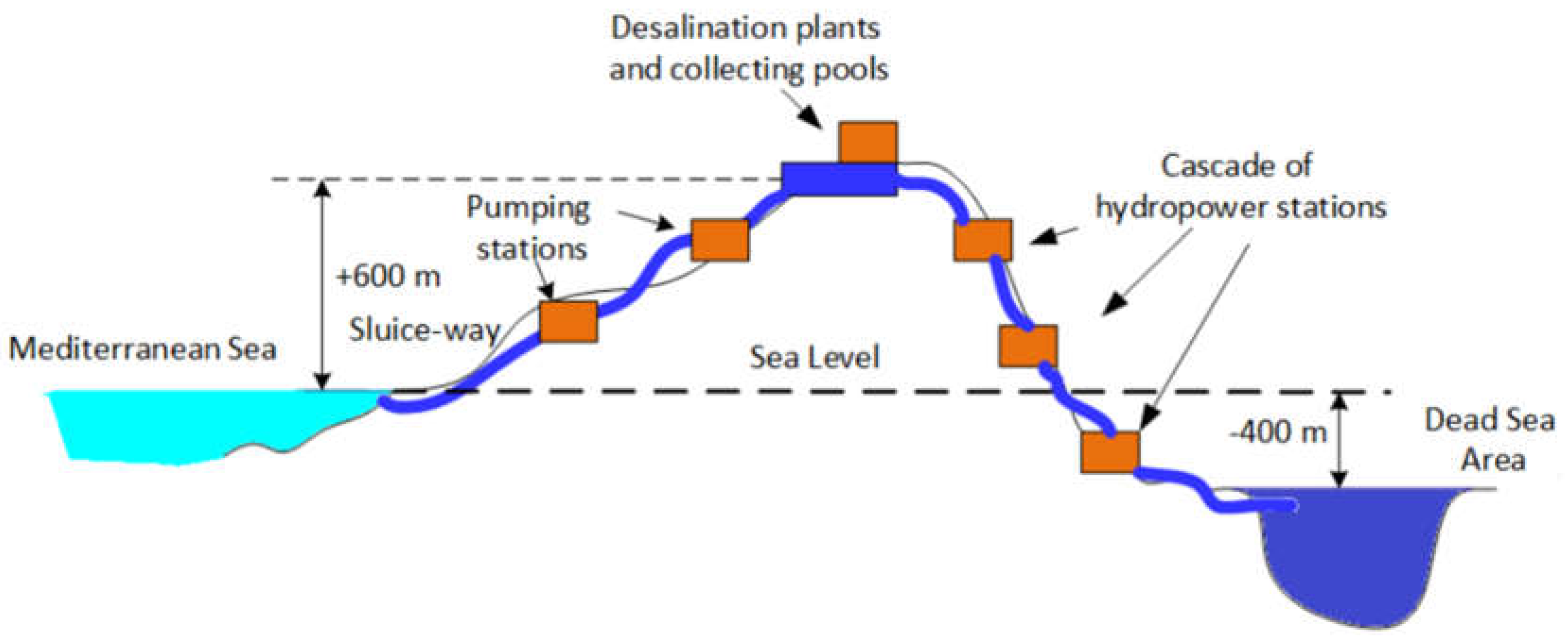

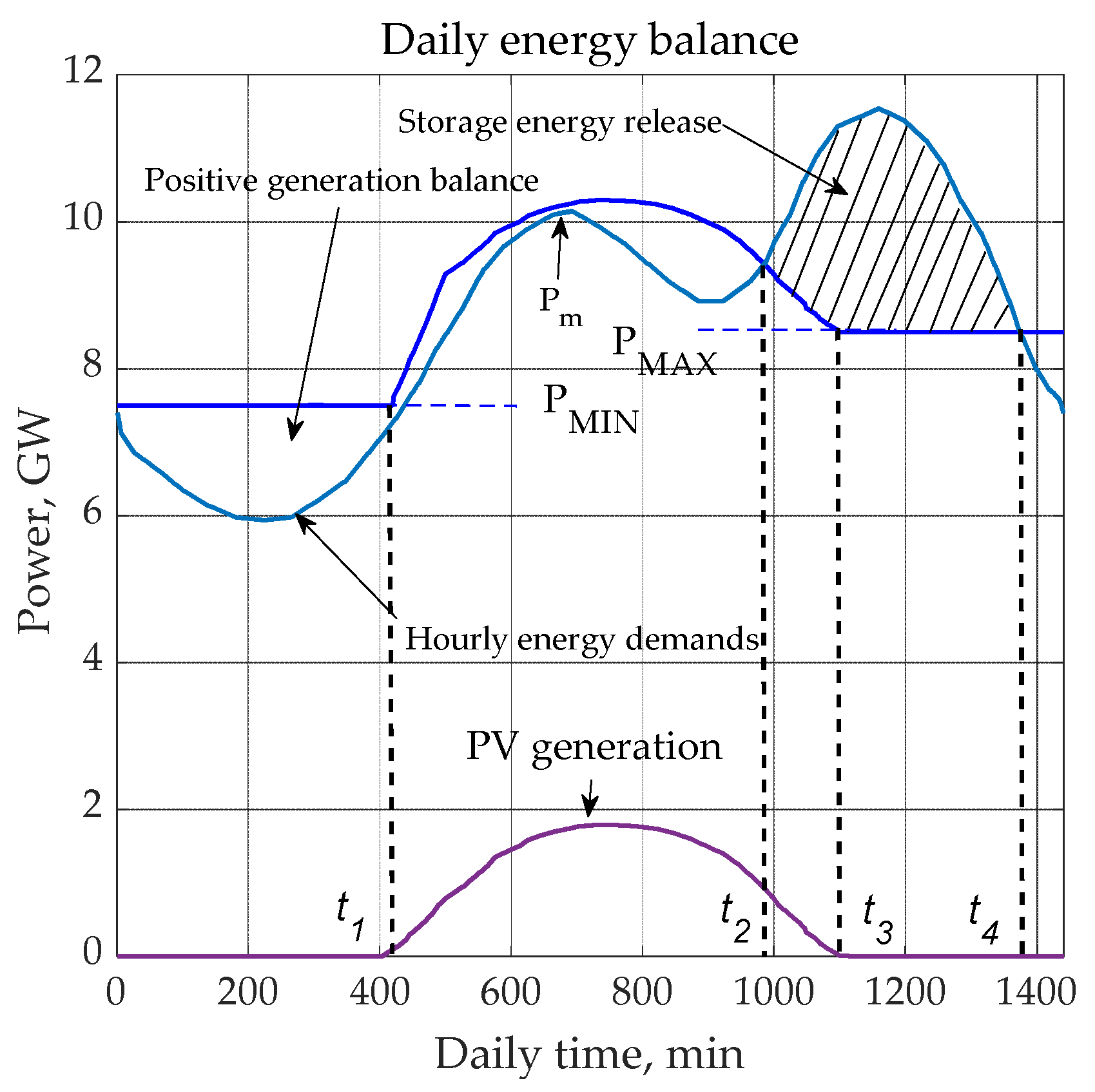

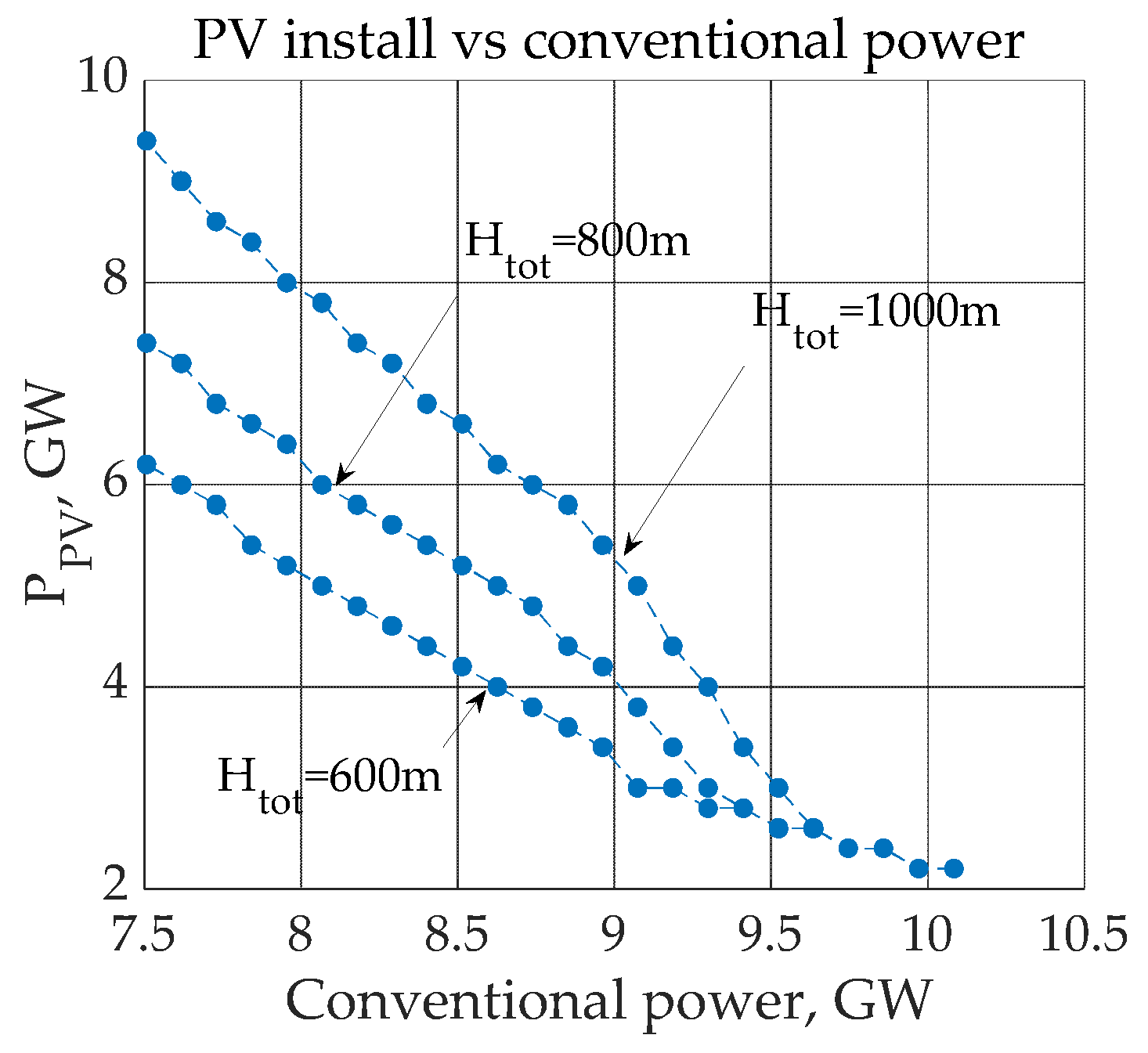

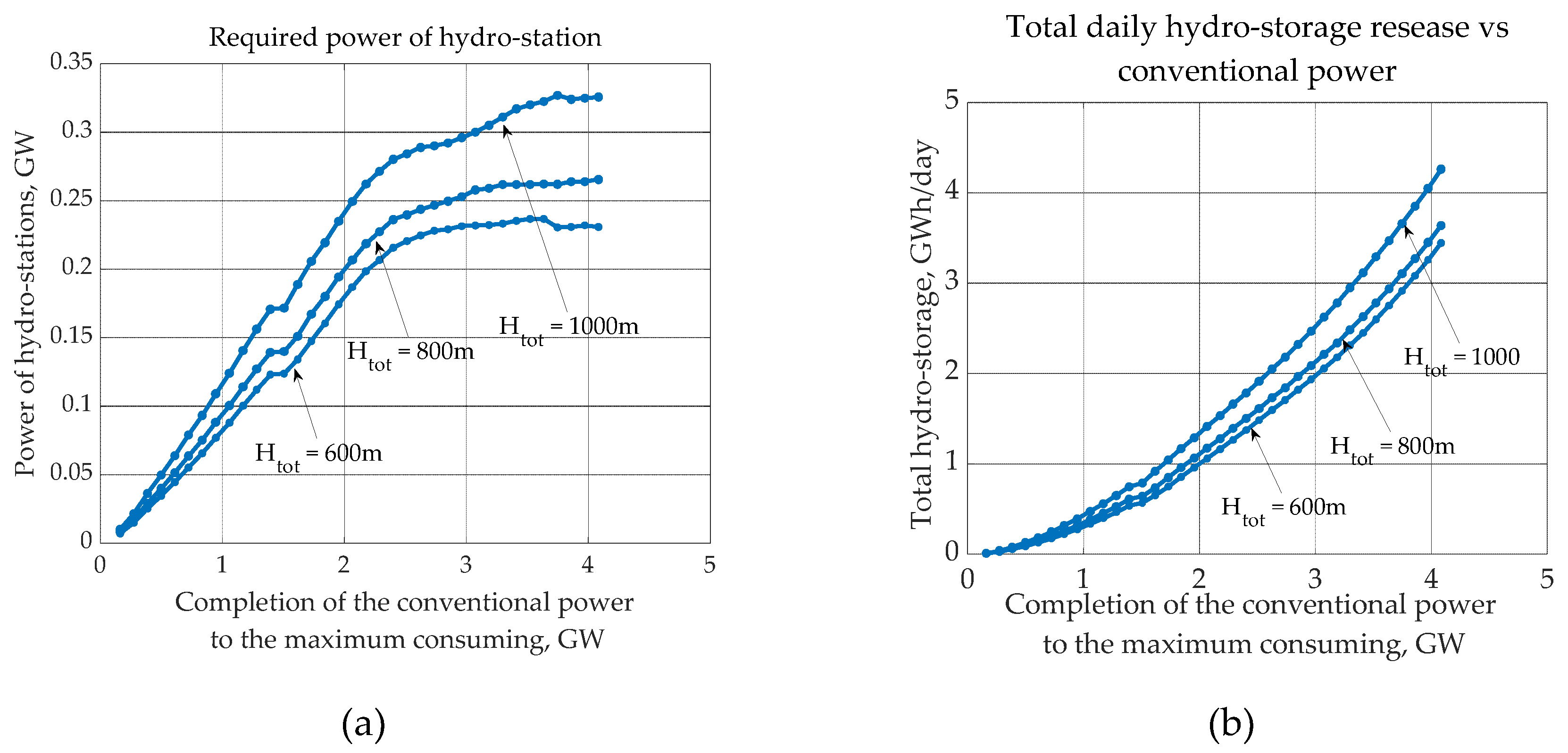

2.1. The schematic diagram of a domestic electric power system combined from conventional generating facilities together with PV plants and hydro-power storage.

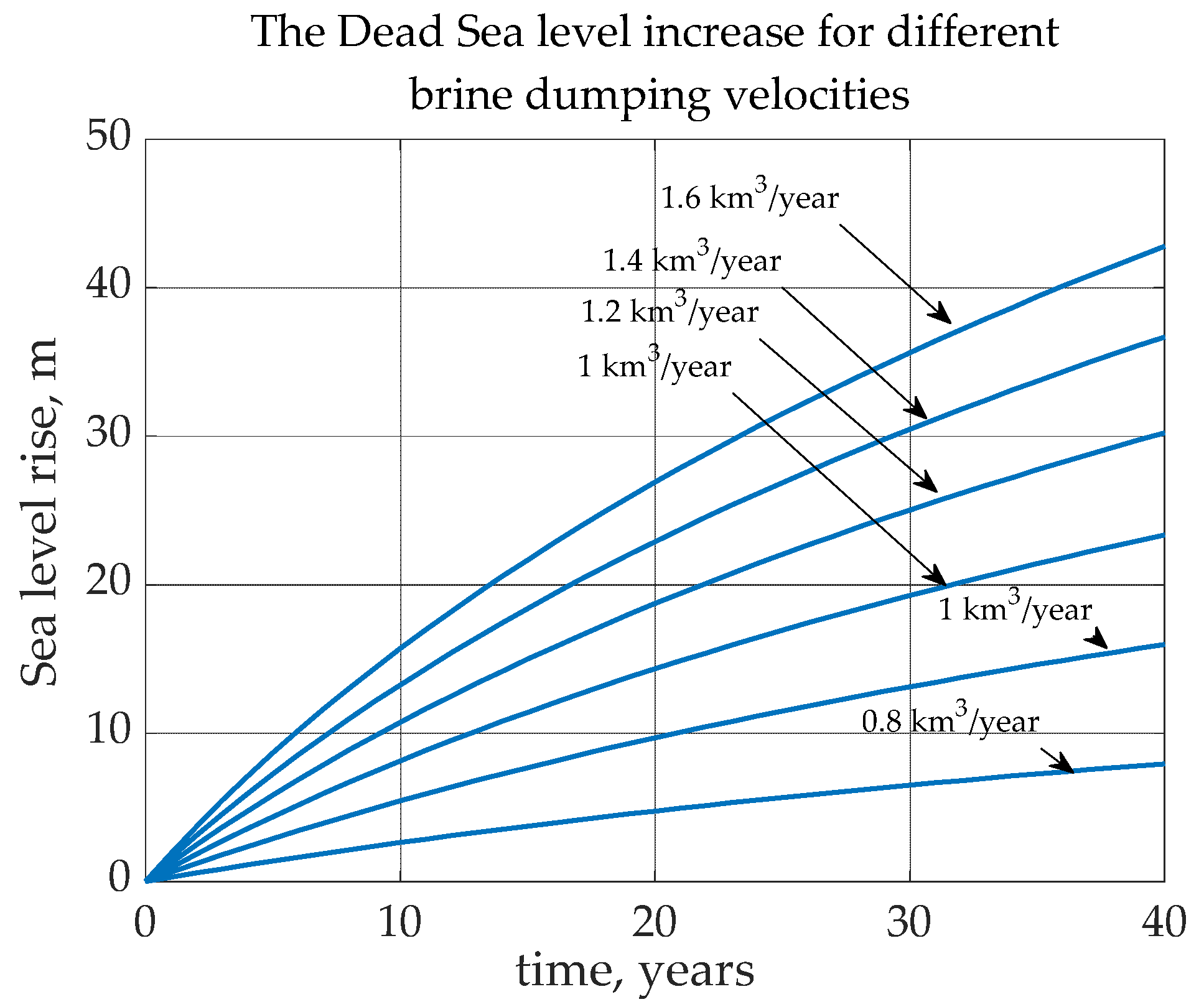

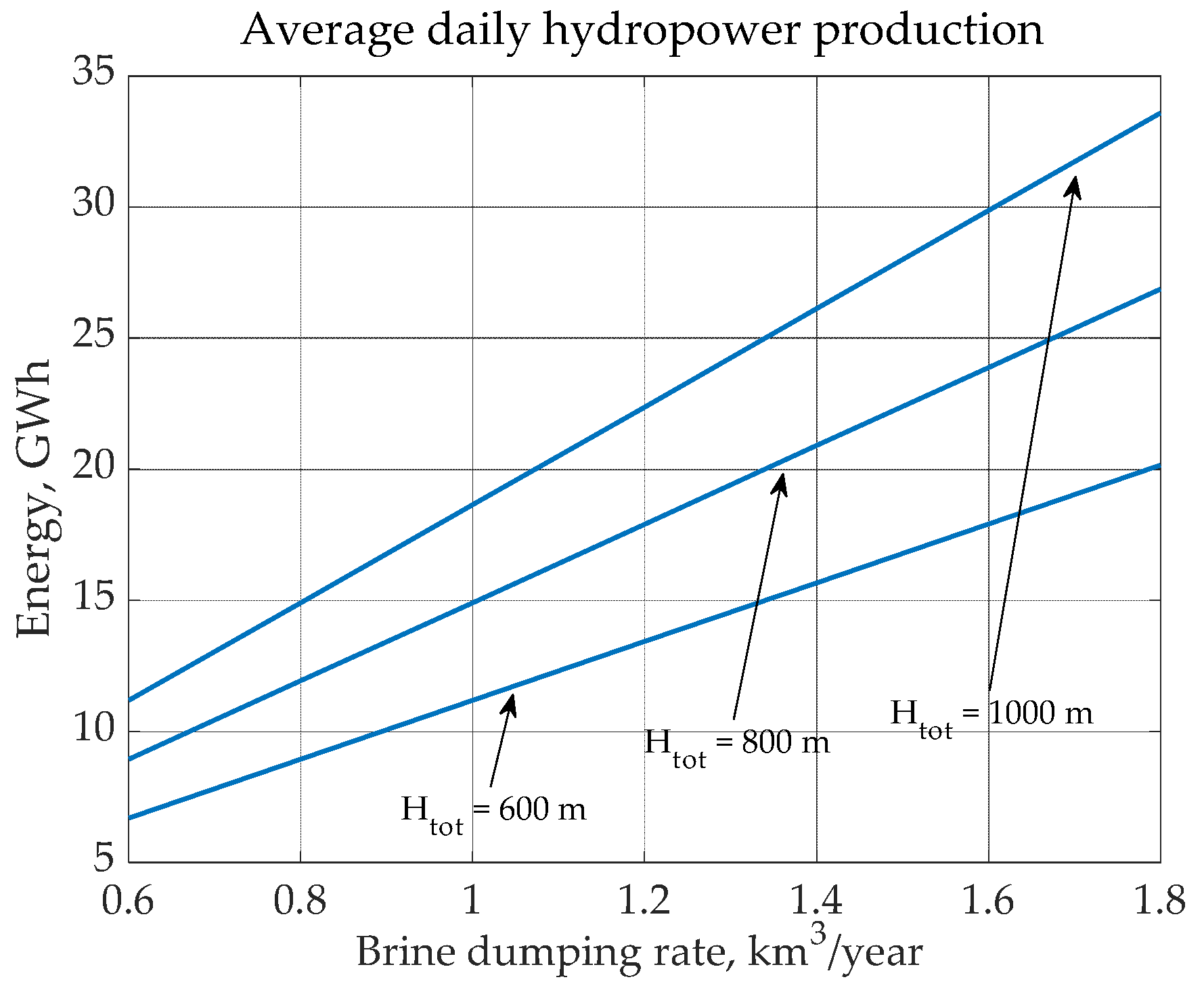

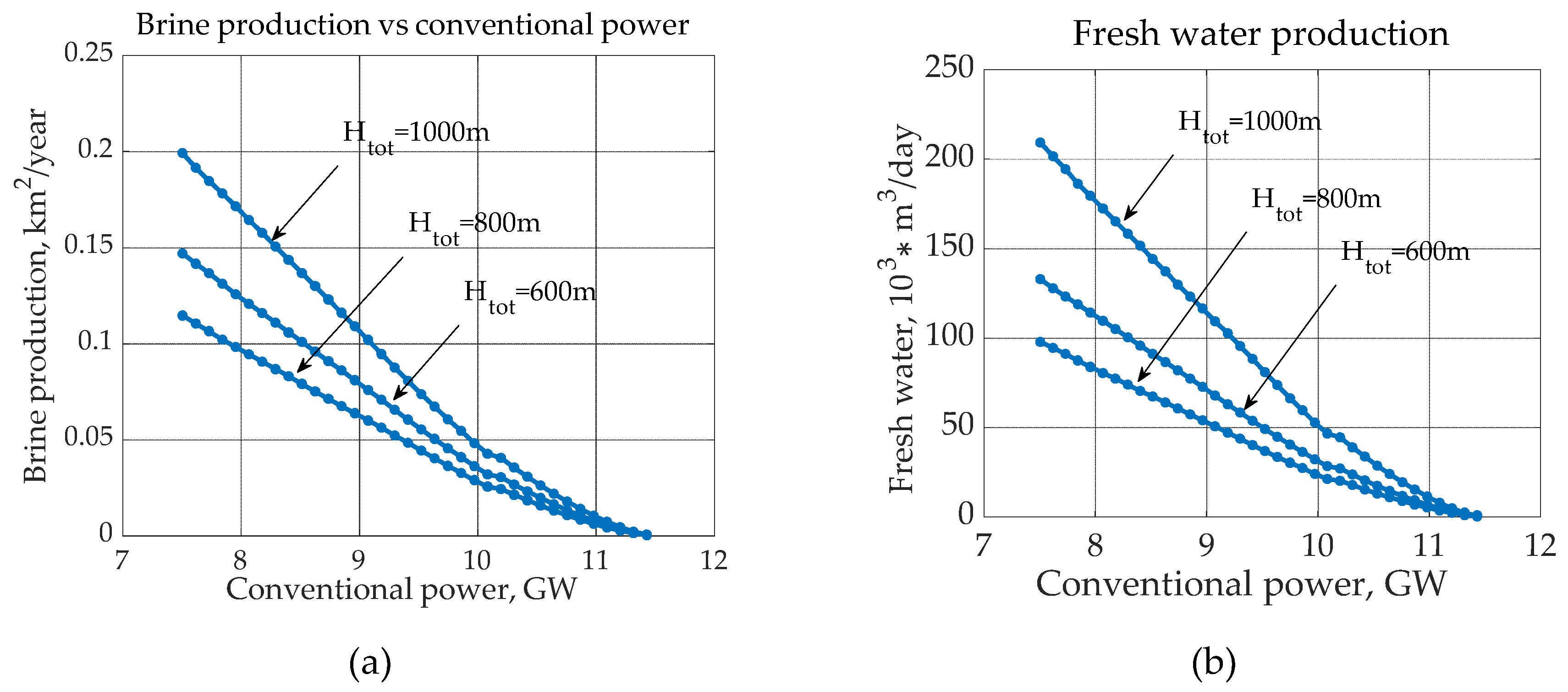

2.2. Estimation of the Dead Sea level increase as per the dumping of the sea water

2.3. Analysis of the electricity demands and hypothetical solar electricity production.

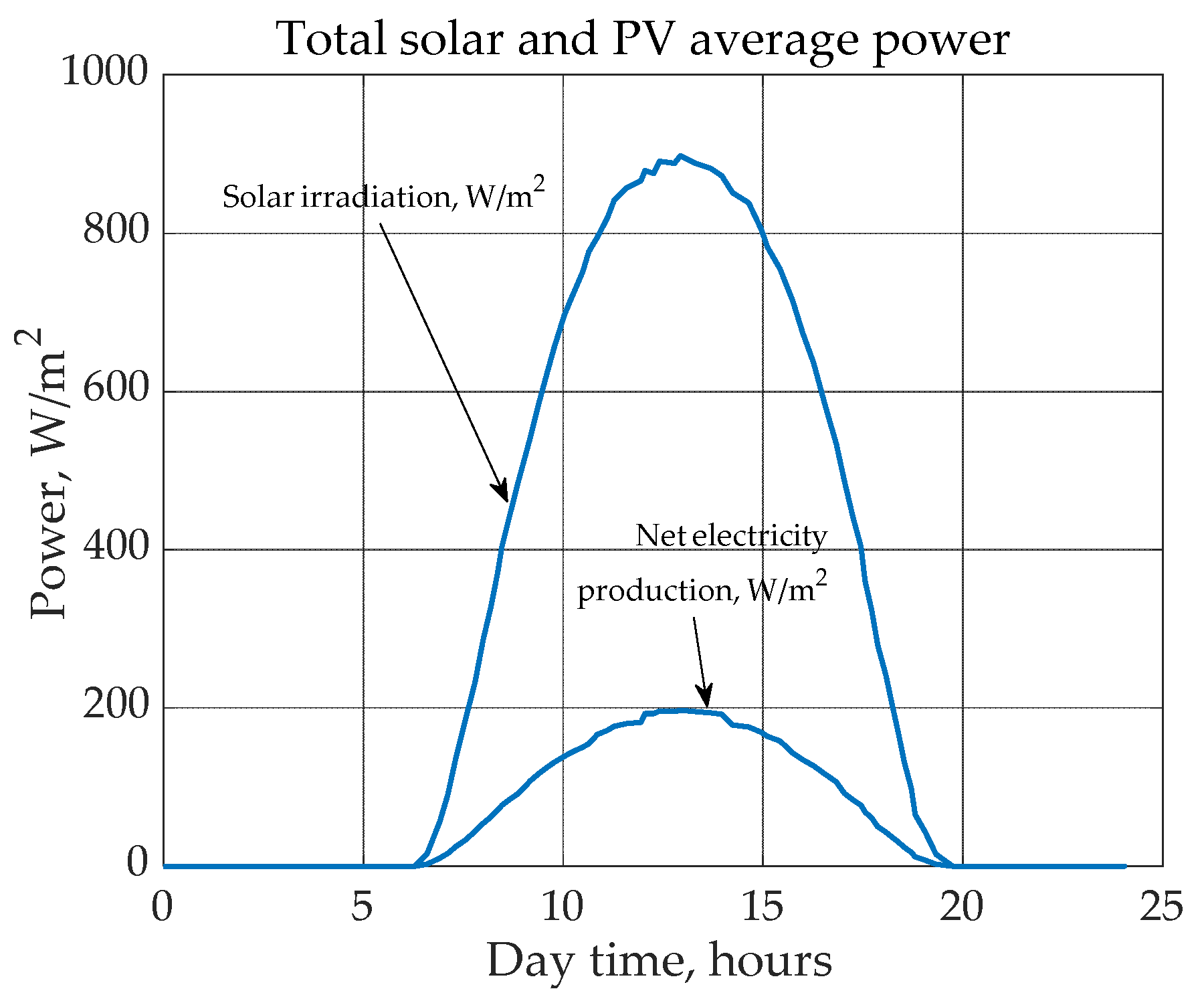

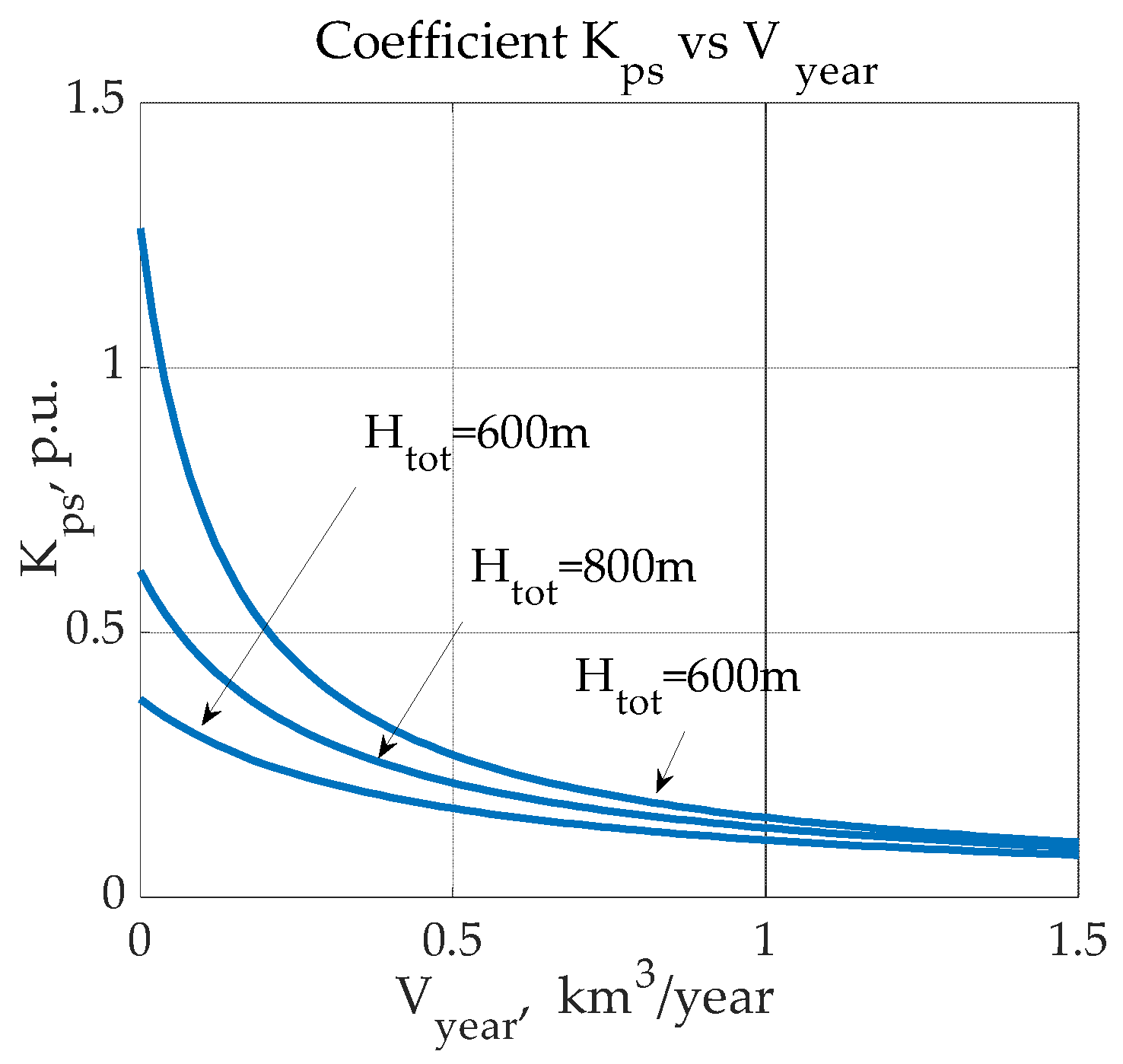

3. Results

6. Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, G.; Shittu, S.; Diallo, T.M.; Yu, M.; Zhao, X.; Ji, J. A review of solar photovoltaic-thermoelectric hybrid system for electricity generation. Energy 2018, 158, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyridonidou, S.; Sismani, G.; Loukogeorgaki, E.; Vagiona, D.G.; Ulanovsky, H.; Madar, D. Sustainable spatial energy planning of large-scale wind and PV farms in Israel: A collaborative and participatory planning approach. Energies 2021, 14, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milstein, I.; Tishler, A.; Woo, C. Wholesale electricity market economics of solar generation in Israel. Utilities Policy 2022, 79, 101443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttikunda, S.K.; Jawahar, P. Atmospheric emissions and pollution from the coal-fired thermal power plants in India. Atmos Environ 2014, 92, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Duan, L.; Lei, Y.; Cao, P.; Hao, J. Primary air pollutant emissions of coal-fired power plants in China: Current status and future prediction. Atmos Environ 2008, 42, 8442–8452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Vargas, A.; Cansino, J.M.; Román-Collado, R. Economic and environmental analysis of a residential PV system: A profitable contribution to the Paris agreement. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 94, 1024–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenk, G.; Meier, R.; Reichelstein, S. Cost dynamics of clean energy technologies. Schmalenbach Journal of Business Research 2021, 73, 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branker, K.; Pathak, M.; Pearce, J.M. A review of solar photovoltaic levelized cost of electricity. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 2011, 15, 4470–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comello, S.; Reichelstein, S.; Sahoo, A. The road ahead for solar PV power. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 92, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balali, M.H.; Nouri, N.; Omrani, E.; Nasiri, A.; Otieno, W. An overview of the environmental, economic, and material developments of the solar and wind sources coupled with the energy storage systems. Int J Energy Res 2017, 41, 1948–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwarya, S. Israel’s Renewable Energy Strategy: A Review of its Stated Goals, Current Status, and Future Prospects. Perceptions: Journal of International Affairs 2021, 26, 321–340. [Google Scholar]

- Rajput, S.; Amiel, I.; Sitbon, M.; Aharon, I.; Averbukh, M. Control the Voltage Instabilities of Distribution Lines using Capacitive Reactive Power. Energies 2020, 13, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiel, I.; Rajput, S.; Averbukh, M. Capacitive reactive power compensation to prevent voltage instabilities in distribution lines. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2021, 131, 107043. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, H.M.; Diab, A.A.Z.; Kuznetsov, O.N.; Ali, Z.M.; Abdalla, O. Evaluation of the impact of high penetration levels of PV power plants on the capacity, frequency and voltage stability of Egypt’s unified grid. Energies 2019, 12, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Saha, T.K. Investigation of voltage stability for residential customers due to high photovoltaic penetrations. IEEE Trans Power Syst 2012, 27, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, A.S. Impact of grid-tied photovoltaic systems on voltage stability of 15unisian distribution networks using dynamic reactive power control. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2022, 13, 101537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yan, X.; Liu, G. A review on voltage control using on-load voltage transformer for the power grid, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, IOP Publishing: 2019;, pp. 03 2144.

- Alam, M.; Chowdhury, T.A.; Dhar, A.; Al-Ismail, F.S.; Choudhury, M.; Shafiullah, M.; Hossain, M.; Ullah, A.; Rahman, S.M. Solar and Wind Energy Integrated System Frequency Control: A Critical Review on Recent Developments. Energies 2023, 16, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, N.; Lashab, A.; Sera, D.; Guerrero, J.M.; Cherif, A. Large photovoltaic power plants integration: A review of challenges and solutions. Energies 2019, 12, 3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzum, B.; Onen, A.; Hasanien, H.M.; Muyeen, S. Rooftop solar pv penetration impacts on distribution network and further growth factors—a comprehensive review. Electronics 2020, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R.; Fernandez, F.M.; Yang, Y. Primary frequency control techniques for large-scale PV-integrated power systems: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 144, 110998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiullah, M.; Ahmed, S.D.; Al-Sulaiman, F.A. Grid Integration Challenges and Solution Strategies for Solar PV Systems: A Review. IEEE Access 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Mao, M.; Ke, G.; Zhou, L.; Xie, B. Stability problems of PV inverter in weak grid: a review. IET Power Electronics 2020, 13, 2165–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, A.A.; Faiman, D.; Meron, G. Grid matching of large-scale wind energy conversion systems, alone and in tandem with large-scale photovoltaic systems: An Israeli case study. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7070–7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X Luo, J Wang, M Dooner, J Clarke. Overview of current development in electrical energy storage technologies and the application potential in power system operation. Appl. Energy. 2015, 137, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D Akinyele, R Rayudu. Review of energy storage technologies for sustainable power networks. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments. 2014, 8, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzuni and, C. Breyer, "Energy security and energy storage technologies. " Energy Procedia 2018, 155, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Z. Jacobson, M.A. Delucchi, M.A. Cameron and B.A. Frew, Low-cost solution to the grid reliability problem with 100% penetration of intermittent wind, water, and solar for all purposes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15060–15065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Z. Jacobson and M.A. Delucchi, "Providing all global energy with wind, water, and solar power, part I: Technologies, energy resources, quantities and areas of infrastructure, and materials. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 1154–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Aliyu, G. Hassan, S.A. Said, M.U. Siddiqui, A.T. Alawami and I.M. Elamin, "A review of solar-powered water pumping systems." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 87, 61–76.

- V. C. Sontake and V.R. Kalamkar, "Solar photovoltaic water pumping system - A comprehensive review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 59, 1038–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Ma, H. Yang and L. Lu, "Feasibility study and economic analysis of pumped hydro storage and battery storage for a renewable energy powered island. Energy Conversion and Management 2014, 79, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakers, A.; Stocks, M.; Lu, B.; Cheng, C. A review of pumped hydro energy storage. Progress in Energy 2021, 3, 022003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.D.; Zakeri, B.; Lopes, R.; Barbosa, P.S.F.; Nascimento, A.; de Castro, N.J.; Brandão, R.; Schneider, P.S.; Wada, Y. Existing and new arrangements of pumped-hydro storage plants. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 129, 109914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.D.; Byers, E.; Wada, Y.; Parkinson, S.; Gernaat, D.E.; Langan, S.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Riahi, K. Global resource potential of seasonal pumped hydropower storage for energy and water storage. Nature communications 2020, 11, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- W. Fang, Q. Huang, S. Huang, J. Yang, E. Meng and Y. Li, "Optimal sizing of utility-scale photovoltaic power generation complementarily operating with hydropower: A case study of the world’s largest hydro-photovoltaic plant. Energy Conversion and Management 2017, 136, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, P. Liu, S. Guo, X. Zhang, M. Feng and X. Wang, "Optimizing utility-scale photovoltaic power generation for integration into a hydropower reservoir by incorporating long- and short-term operational decisions. Applied Energy 2017, 204, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Ma, H. Yang, L. Lu and J. Peng, "An optimization sizing model for solar photovoltaic power generation system with pumped storage. Energy Procedia 2014, 61, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Cipollina, G Micale, L Rizzuti, Seawater desalination: conventional and renewable energy processes, Springer Science & Business Media 2009.

- E Chafik. A new type of seawater desalination plants using solar energy. Desalination. 2003, 156, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WG Shim, K He, S Gray, IS Moon. Solar energy assisted direct contact membrane distillation (DCMD) process for seawater desalination. Separation and Purification Technology. 2015, 143, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Chen and W. Lam, "A review of survivability and remedial actions of tidal current turbines. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 43, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://icl-group-sustainability.com/reports/dead-sea-water-level/.

- https://water.fanack.com/publications/red-sea-dead-sea-project/.

- Salhotra, A.M.; Adams, E.E.; Harleman, D.R. Effect of salinity and ionic composition on evaporation: Analysis of Dead Sea evaporation pans. Water Resour Res 1985, 21, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Kuang, Y.; Hu, L. Challenges and opportunities for solar evaporation. Joule 2019, 3, 683–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.gov.il/en/departments/publications/reports/potential_for_solar_production_on_existing_structures_jan_2020. 2020.

- Chang, J.; Li, Y.; Yuan, M.; Wang, Y. Efficiency evaluation of hydropower station operation: A case study of Longyangxia station in the Yellow River, China. Energy 2017, 135, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, N.; Gertner, Y.; Shoham-Frider, E. Seawater quality at the brine discharge site from two mega size seawater reverse osmosis desalination plants in Israel (Eastern Mediterranean). Water Res 2020, 171, 115402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stover, R.L. Seawater reverse osmosis with isobaric energy recovery devices. Desalination 2007, 203, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, K.; Yang, D.R.; Hong, S. A comprehensive review of energy consumption of seawater reverse osmosis desalination plants. Appl Energy 2019, 254, 113652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watton, J. Fundamentals of fluid power control, Cambridge University Press: 2009.

- Solomon, A.A.; Faiman, D.; Meron, G. Properties and uses of storage for enhancing the grid penetration of very large photovoltaic systems. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 5208–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).