1. Introduction

As of March 28, 2023, more than 761 million people have been affected by SARS-CoV-2, and more than 6.8 million people have died worldwide. While vaccines play a critical role in public health preventive measures to prevent coronavirus from infecting our cells [

1], the emergence of mutations in the virus has led to concerns about vaccine efficacy, particularly among frontline healthcare workers as they interact with COVID-19 patients, leading to a higher risk of infection and further spread [

2].

During the initial phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Thailand, access to vaccine and the gold-standard test was limited [

3,

4]. In response, the inactivated CoronaVac vaccine from Sinovac Biotech was introduced as a mass vaccination for both healthcare workers and the general population. However, antibody levels to SARS-CoV-2 were found to decrease three months after two doses of CoronaVac [

5], necessitating a third booster dose. While the BNT162b2 demonstrated higher immunogenicity compared to the CoronaVac booster [

6], Thailand did not have access to this vaccine until the end of 2021. Instead, the viral vector vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 from AstraZeneca was a promising option for use as a third booster dose in the general population who had previously received two doses of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, showing promising immunogenicity for both humoral and cellular immune responses [

7,

8].

Given limited evidence regarding the immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 as a third booster dose following two doses of CoronaVac, we previously conducted a study in healthcare workers that demonstrated adequate but declining antibody levels to protect against SARS-CoV-2 at three months post-vaccination [

9]. With the recommendation for the fourth booster vaccination in Thailand being four months after the third booster vaccination [

10], there was concern about the sustainability of SARS-CoV-2 protection after three months, given the significant decrease in antibody levels. As such, this study represents an extended prospective cohort study aimed at evaluating the long-term sustainability of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 immunogenicity as the third vaccine dose in healthcare workers, specifically six months after vaccination.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was an observational, prospective cohort study that included 170 healthcare workers who had received two doses of CoronaVac between February to March 2021 and subsequently received a third dose of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine. Proof of CoronaVac vaccination was obtained through the use of case record forms (CRFs). To determine the levels of antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, blood samples were collected from all participants before (day 0) and after the administration of the third vaccine dose (at 1, 3, and 6 months). The levels of both immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody and neutralizing antibody were measured using an enzyme immunoassay (Euroimmun) ELISA. The IgG antibody assay works on the principle that the test kit contains microplate strips with 8 break-off reagent wells coated with the recombinant S1 domain of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. In the first reaction step, the diluted samples are incubated in the wells. If the samples are positive, specific IgG (also IgA and IgM) antibodies will bind to the antigens. To detect the bound antibodies, a second incubation is performed with an enzyme-labeled anti-human IgG (enzyme conjugate) that catalyzes a color reaction. The neutralizing antibody assay used in this study involves microplate strips with 8 reagent wells coated with recombinant S1/RBD domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. In the first step, both controls and samples are diluted with sample buffer containing soluble biotinylated ACE2 and then incubated in the wells. If neutralizing antibodies are present in the sample, they compete with receptor ACE2 for the binding sites of SARS-CoV-2 S1/RBD proteins. Any unbound ACE2 is removed in a subsequent wash step. To detect bound ACE2, a second incubation step is performed with peroxidase-labeled streptavidin, which catalyzes a color reaction in the third reaction step. The intensity of the color formed is inversely proportional to the concentration of neutralizing antibody in the sample.

Participants were categorized into quartiles based on their antibody levels prior to receiving the third dose. Random selection of five participants from each quartile was done to measure their IgG antibody levels. SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell responses were measured using Interferon-gamma ELISpot before and after vaccination with ChAdOx1 nCoV-19. Subgroup analysis was conducted to determine the effect of antibody level on each IgG group, with the Negative group defined as IgG < 32 BAU/ml and the Positive group defined as IgG ≥ 32 BAU/ml. The pseudovirus-based neutralization assay (PVNT) was utilized to evaluate the neutralization activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants, including Wuhan, Delta, and Omicron (BA.1, BA.2 and BA.4/BA.5). Serum samples were incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes to inactivate complement factors, and then a two-fold serial dilution of the serum samples starting at 1:40 was mixed with 50 µl of SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus in a 96-well culture plate. The mixture was incubated for 1 hour at 37◦C, 5% CO2, then HEK293T/17-hACE2-TMPRSS2 transfected cell suspensions (4 × 106 cells/well) were seeded into each well of the tissue culture plates and incubated for 48 hours at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus titer was measured based on luciferase activity using a microplate reader, and the IC50 was calculated using GraphPad Prism software.

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA software, version 15. Descriptive statistics were used to report mean and 95% confidence interval for normally distributed quantitative data, and the median and interquartile range for non-normally distributed quantitative data. Paired t-tests were performed to compare anti-spike IgG levels before vaccination to levels at 1, 3, and 6 months after vaccination for all participants. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research related to COVID-19 Disease or Public Health Emergency, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health (Ref.No. 64064, IRB.No. FWA 00013622). The participants provided written informed consent. The protocol was registered at the Thai Clinical Trial Registry (TCTR20211005001). The study received financial support from the National Research Council of Thailand (N5B640133).

3. Results

The study included 170 healthcare workers who received ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 as a third dose following two shots of CoronaVac. None of the participants had a history of COVID-19 infection. The majority of the participants were female (81.8%), and 42.35% had comorbidities. The mean age of the participants was 45 (IQR, 35-52) years. Before the administration of the third dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, a subgroup of individuals underwent a seroneutralization test, and their results were analyzed based on their IgG levels. The test considered concentrations below 32 BAU/ ml as negative. Of the 170 participants, 25 (14.7%) had negative anti-spike IgG levels at baseline (

Table 1).

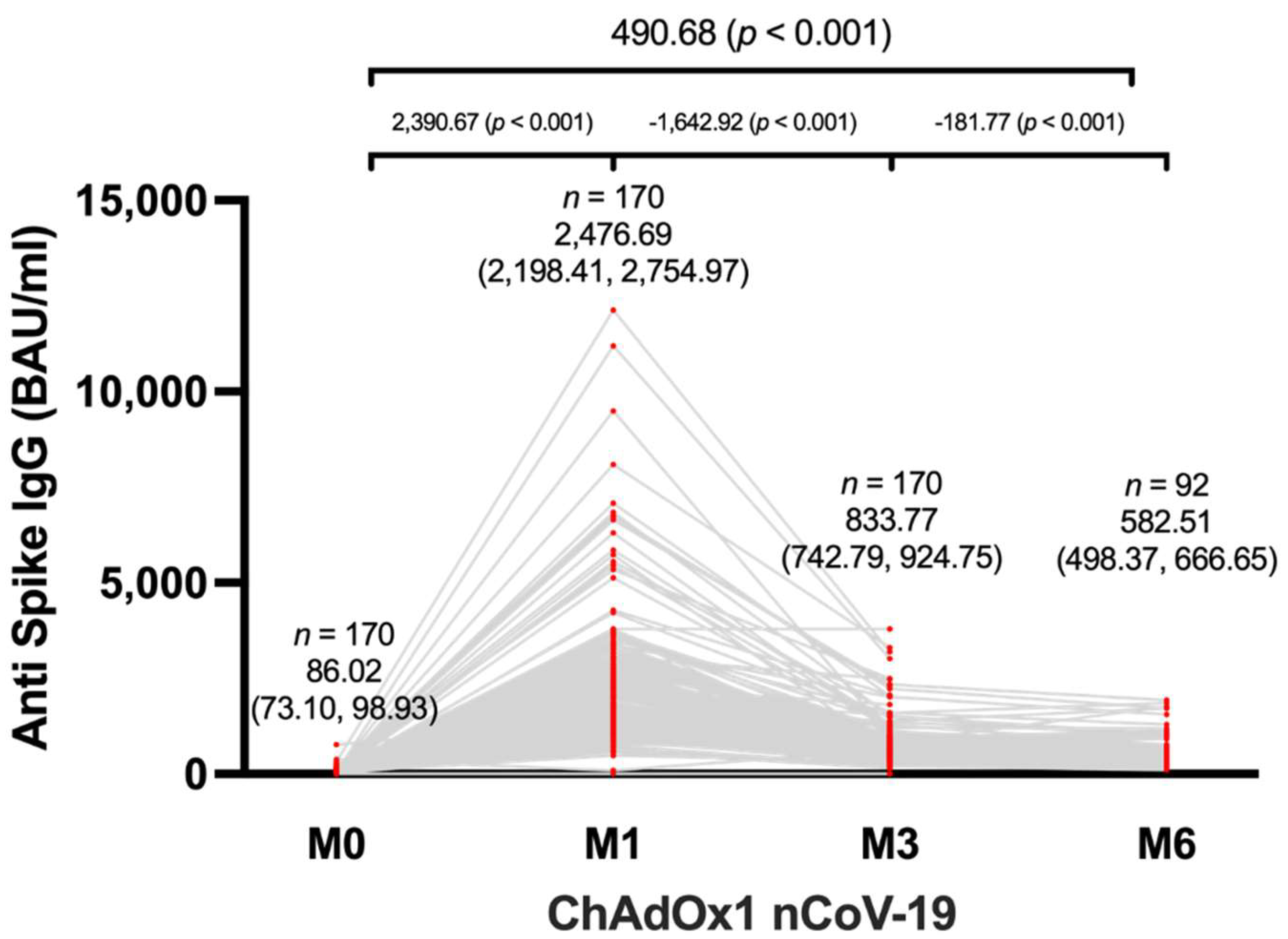

The study investigated the levels of anti-spike IgG in 170 participants before and after receiving the third dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, following two shots of CoronaVac. The mean anti-spike IgG level before vaccination was 86.02 BAU/mL (95% CI, 73.10-98.93). After the third dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, the mean anti-spike IgG level significantly increased to 2,476.69 BAU/mL (95% CI, 2198.41-2754.97) one month after vaccination, and the levels remained elevated at 833.77 BAU/mL (95% CI, 742.79-924.75) three months after vaccination and 582.51 BAU/mL (95% CI, 498.37-666.65) six months after vaccination (

Figure 1). Furthermore, it was observed that SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG levels peaked at one month after vaccination and remained higher than pre-vaccination levels until 6 months after vaccination. Although there was a decrease in IgG levels at 6 months post-vaccination compared to 1 and 3 months, the levels were significantly higher than baseline.

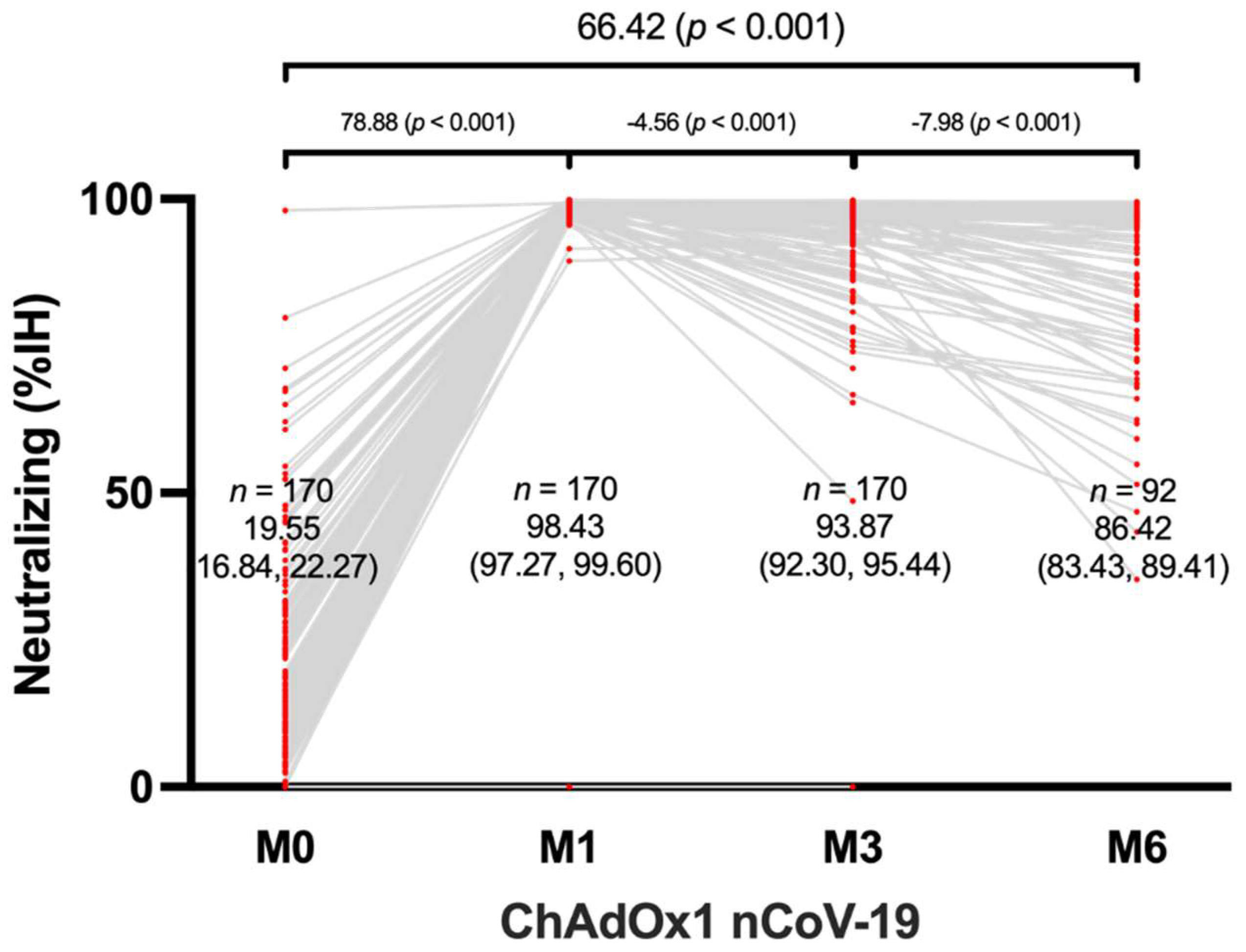

The neutralizing antibody levels of all 170 participants were tested using the aforementioned method. After one month of vaccination, the mean neutralizing antibody level shoed a significant increase from 19.55% to 98.43% when compared to the baseline. At the 6-month mark, the mean neutralizing antibody level remained high at 86.42% (p < 0.001). The data also indicated that there was no significant difference between the neutralizing levels at 3 and 6 months after the third dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, indicating that the immune response elicited by the vaccine is robust and sustained over several months.

Figure 2.

Neutralization antibody response in ChAdOx1 nCoV-19-vaccinated healthcare workers.

Figure 2.

Neutralization antibody response in ChAdOx1 nCoV-19-vaccinated healthcare workers.

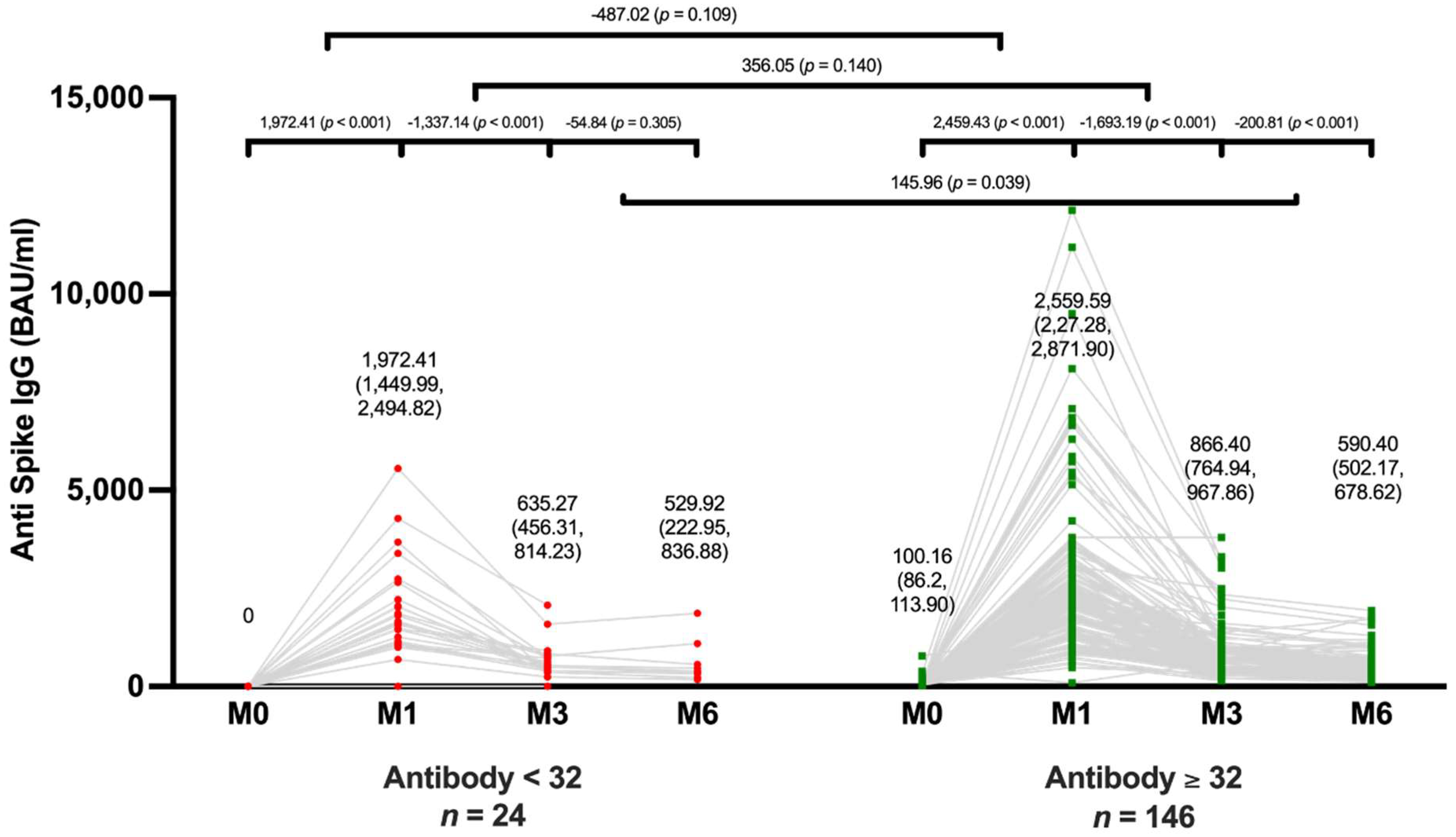

Comparisons of an Antibody Level between Subgroups

The mean IgG levels decreased significantly from 635.27 BAU/ ml (95% CI, 435.31-814.23) at 3 months to 529.92 BAU/ ml (95% CI, 222.95-836.88) at 6 months after an additional shot (p < 0.001). In the positive IgG group, mean IgG level also decreased significantly at 6 months, from 866.40 BAU/ ml (95% CI, 764.94-967.86) at 3 months to 590.40 BAU/ ml (95% CI, 502.17-678.62) after additional vaccination (p < 0.001) (

Figure 3). Although the mean anti-spike IgG level was significantly higher in the positive group at 3 months, there was no significant difference in mean anti-spike IgG levels between the positive and negative groups at 6 months after vaccination.

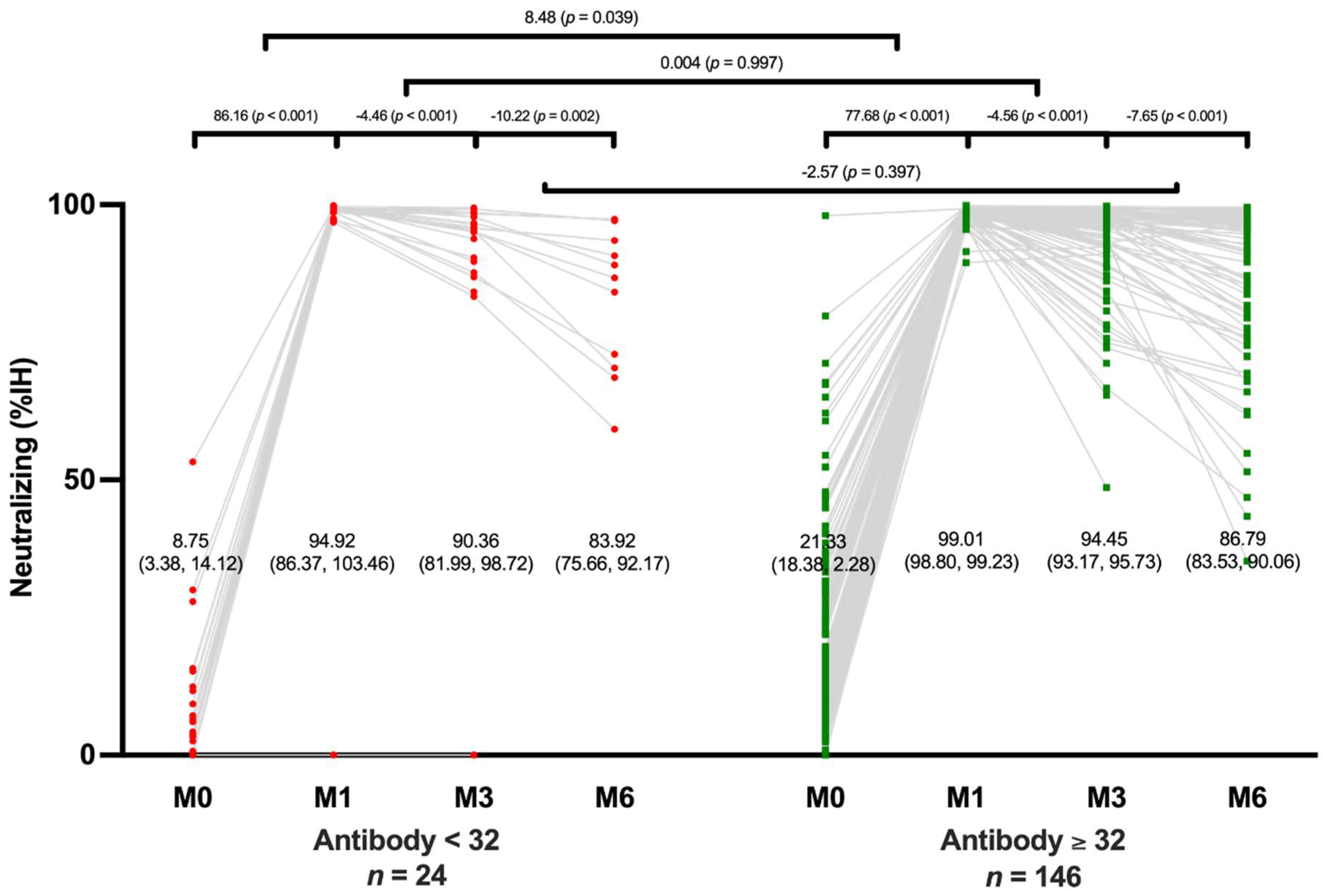

Neutralizing antibody levels decreased rapidly in both the positive and negative groups during the first 3 months after vaccination and then decreased at a relatively slower rate after 6 months. The level of neutralizing antibodies in the positive group decreased from 94.45% (95% CI, 93.17-95.73) at 3 months to 86.79% (95% CI, 93.53-90.06) at 6 months while the level in the negative group decreased from 90.36% (95% CI, 81.99-98.72) at 3 months to 83.92% (95% CI, 75.66-92.17) at 6 months. Both the positive and negative groups experienced a significant decrease in neutralizing antibody levels during the 6 months after vaccination (p < 0.001 and p = 0.002, respectively). There was no significant difference in neutralizing antibody levels between the positive and negative groups at 6 months after vaccination (p = 0.397) (

Figure 4).

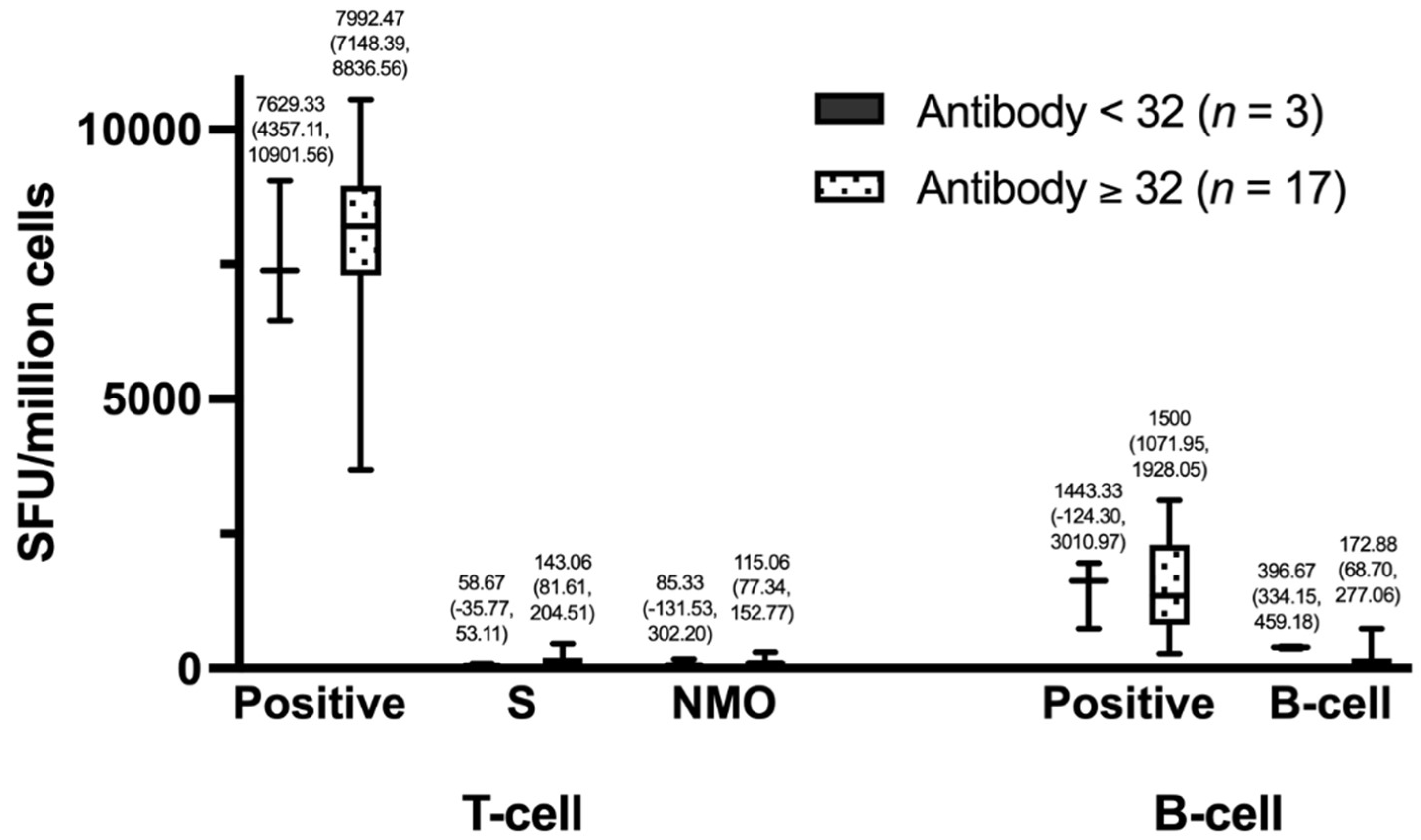

SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell responses between Subgroups

The group with positive IgG had higher T-cell counts than the group with negative IgG. Specifically, the positive group had T-cell counts of 7,992.47 (95% CI, 7,148.39-8,836.56) compared to 7,629.33 (95% CI, 4,357.11-10,901.56) in the negative group, S-cell counts of 143.06 (95% CI, 81.61-204.51) compared to 58.67 (95% CI, -35.77-53.11), and NMO counts of 115.06 (95% CI, 77.34-152.77) compared to 85.33 (95% CI, -131.53-302.20). Similarly, the group with positive IgG had higher B-cell counts than the group with negative IgG, with positive counts of 1,500 (95% CI, 1,071.95-1,928.05) compared to 1,443.33 (95% CI, -124.30-3,010.97). However, for B cells, the negative IgG group had higher counts than the positive group, with counts of 396.67 (95% CI, 334.15-459.18) compared to 172.88 (95% CI, 68.70-277.06), as shown in

Figure 5.

Neutralizing antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 variants 6 months after boosting

The pseudovirus-based neutralization assay (PVNT) was used to evaluate neutralization activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants among participants 6 months after boosting. The results showed high neutralization activity against the Wuhan variant, with a mean PVNT level of 177.55 (95% CI, 134.94-220.16). However, for the other variants, the mean PVNT levels were lower, with 91.92 (95% CI, 56.53-127.31) for Delta, 72.22 (95% CI, 17.87-126.57) for BA.4/BA.5, 53.97 (95% CI, 22.88-85.07) for BA.2, and 49.92 (95% CI, 9.85-90.00) for BA.1 (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

In this prospective observational study, 170 healthcare workers were enrolled, among whom 146 had positive anti-spike antibody levels at baseline, three months after receiving two doses of CoronaVac, and these antibody levels decreased dramatically over time. The administration of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 as a third booster dose resulted in a significant improvement in both anti-spike and neutralizing antibody levels. Although antibody levels declined at 3- and 6-month time points after vaccination, they remained above the protective threshold, thereby providing adequate protection against severe disease. Additionally, our findings demonstrate notable neutralizing activity against the five most common variants after 6 months of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 as the third dose.

In a recent study, we investigated the antibody levels of healthcare workers who received two doses of CoronaVac followed by a third dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine [

9]. Our findings revealed a significant decline in antibody levels to SARS-CoV-2 after 3 months, raising concerns about the potential inadequacy of antibody levels to protect against the virus and prompting questions about the optimal timing for a fourth booster dose.

However, we also observed that the decline in antibody levels was slower in the 3- to 6-month period after vaccination than in the 1- to 3-month, and adequate antibody protection was maintained 6 months after the third dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19. This provides evidence to support the sustainability of the vaccine effect and allays concerns about the need for a fourth booster dose.

The current recommendation in Thailand is to administer a fourth booster dose 4 months after the third dose, with a 2-month window of protection in case the schedule cannot be met [

10]. Our study suggests that a longer interval between the third and fourth booster doses may be possible since there is evidence of protection against SARS-CoV-2 6 months after a third booster dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19. However, it is important to note that the current recommendation for a fourth booster dose was based on previous evidence that did not include studies of long-term protection.

Six months after administering the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 booster dose, the neutralizing activity against the most common SARS-CoV-2 variants, including the Wuhan, Delta, and Omicron subtypes BA.1, BA.2, and BA.4/5 was sufficient. The highest protection was observed against the Wuhan variant, followed by the Delta variant, which caused more severe COVID-19 than the Omicron variant [

11,

12]. These findings were consistent with previously published short-term results for ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine as the third dose in participants who had received two doses of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 [

13,

14]. Notably, we observed high neutralization activity against the highly infectious Omicron subtype BA.4/5, which is currently prevalent in Thailand [

15]. Although neutralization activity against the Omicron subtypes BA.1 and BA.2 was lower, it was still sufficient to protect against severe disease caused by these variants. This was demonstrated in a vaccine efficacy study where participants received two doses of CoronaVac followed by a third dose booster of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 [

16].

While the findings of this study are significant, it is important to note that the study population consisted solely of healthcare workers and may not be fully generalizable to the broader population. Therefore, any extrapolation of these results to other groups should be done with caution. Nevertheless, these results provide valuable insights into the durability of the immune response following ChAOx1 nCoV-19 booster vaccination in individuals who previously received two doses of CoronaVac, suggesting that the vaccine provides sustained protection against SARS-CoV-2 for up to 6 months.

5. Conclusions

Our study provides evidence that the ChAOx1 nCov-19 vaccine as a third booster dose can induce a sustained antibody response against SARS-CoV-2 for at least 6 months, including protection against commonly circulating variants such as Delta and Omicron. However, the duration and extent of protection against emerging variants of concern remain to be evaluated in future studies. It is important to note that the findings of this study may not be generalizable to the general population, as our samples was limited to healthcare workers. Despite these limitations, our study highlights the importance of continued monitoring of vaccine effectiveness and the potential need for additional booster doses to maintain immunity against SARS-CoV-2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.P. (Wisit Prasithsirikul), K.P. and T.N.; methodology, K.P., W.P. (Wannarat Pongpirul) and T.N.; software, K.P., M.H. and P.P.; validation, C.S., A.J., W.P. (Wannarat Pongpirul) and K.P.; formal analysis, M.H., P.P. and P.S.; investigation, M.H., P.S., W.P. (Wannarat Pongpirul) and C.S.; resources, W.P. (Wisit Prasithsirikul) and K.P.; data curation, M.H., P.S., W.P. (Wannarat Pongpirul) and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H., K.P. and T.N.; writing—review and editing, M.H., T.N., K.P. and A.J.; visualization, P.P. and M.H.; supervision, W.P. (Wisit Prasithsirikul) and A.J.; project administration, K.P. and W.P. (Wannarat Pongpirul); funding acquisition, W.P. (Wisit Prasithsirikul) and K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT), grant number N5B640133.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Research related to COVID-19 Disease or Public health Emergency, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand (Ref.No. 64064; IRB.No. FWA00013622; 8 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The supporting data for the findings of this study are available from corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the healthcare workers for their kind participation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fiolet, T.; Kherabi, Y.; MacDonald, C.; Ghosn, J.; Peiffer-Smadja, N. Comparing COVID-19 vaccines for their characteristics, efficacy and effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern: a narrative review. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022, 28, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, N.; Cheong, C.; Kong, G.; Phua, K.; Ngiam, J.; Tan, B.; Wang, B.; Hao, F.; Tan, W.; Han, X.; et al. An Asia-Pacific study on healthcare workers' perceptions of, and willingness to receive, the COVID-19 vaccination. Int J Infect Dis 2021, 106, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nopsopon, T.; Pongpirul, K.; Chotirosniramit, K.; Hiransuthikul, N. COVID-19 seroprevalence among hospital staff and preprocedural patients in Thai community hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nopsopon, T.; Pongpirul, K.; Chotirosniramit, K.; Jakaew, W.; Kaewwijit, C.; Kanchana, S.; Hiransuthikul, N. Seroprevalence of hospital staff in a province with zero COVID-19 cases. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0238088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamanukul, S.; Traiyan, S.; Yorsaeng, R.; Vichaiwattana, P.; Sudhinaraset, N.; Wanlapakorn, N.; Poovorawan, Y. Safety and immunogenicity of inactivated COVID-19 vaccine in health care workers. J Med Virol 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keskin, A.; Bolukcu, S.; Ciragil, P.; Topkaya, A. SARS-CoV-2 specific antibody responses after third CoronaVac or BNT162b2 vaccine following two-dose CoronaVac vaccine regimen. J Med Virol 2022, 94, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, A.; Janani, L.; Cornelius, V.; Aley, P.; Babbage, G.; Baxter, D.; Bula, M.; Cathie, K.; Chatterjee, K.; Dodd, K.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of seven COVID-19 vaccines as a third dose (booster) following two doses of ChAdOx1 nCov-19 or BNT162b2 in the UK (COV-BOOST): a blinded, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 2258–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaxman, A.; Marchevsky, N.; Jenkin, D.; Aboagye, J.; Aley, P.; Angus, B.; Belij-Rammerstorfer, S.; Bibi, S.; Bittaye, M.; Cappuccini, F.; et al. Reactogenicity and immunogenicity after a late second dose or a third dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 in the UK: a substudy of two randomised controlled trials (COV001 and COV002). Lancet 2021, 398, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasithsirikul, W.; Pongpirul, K.; Nopsopon, T.; Phutrakool, P.; Pongpirul, W.; Samuthpongtorn, C.; Suwanwattana, P.; Jongkaewwattana, A. Immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Booster Vaccination Following Two CoronaVac Shots in Healthcare Workers. Vaccines 2022, 10, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry recommends boosters every 4 months. Available online: https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2327243/ministry-recommends-boosters-every-4-months (accessed on 4 April).

- Wolter, N.; Jassat, W.; Walaza, S.; Welch, R.; Moultrie, H.; Groome, M.; Amoako, D.; Everatt, J.; Bhiman, J.; Scheepers, C.; et al. Early assessment of the clinical severity of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant in South Africa: a data linkage study. Lancet 2022, 399, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auvigne, V.; Vaux, S.; Strat, Y.; Schaeffer, J.; Fournier, L.; Tamandjou, C.; Montagnat, C.; Coignard, B.; Levy-Bruhl, D.; Parent du Châtelet, I. Severe hospital events following symptomatic infection with Sars-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta variants in France, December 2021-January 2022: A retrospective, population-based, matched cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 48, 101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, W.; Raju, R.; Babji, S.; George, A.; Madhavan, R.; Leander Xavier, J.; David Chelladurai, J.; Nikitha, O.; Deborah, A.; Vijayakumar, S.; et al. Immunogenicity and safety of homologous and heterologous booster vaccination of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (COVISHIELD™) and BBV152 (COVAXIN®): a non-inferiority phase 4, participant and observer-blinded, randomised study. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia 2023, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsebom, F.; Andrews, N.; Sachdeva, R.; Stowe, J.; Ramsay, M.; Lopez Bernal, J. Effectiveness of ChAdOx1-S COVID-19 booster vaccination against the Omicron and Delta variants in England. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 7688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- What to Know About the Newest, Most Contagious Omicron Subvariants.

- Wong, M.; Dhaliwal, S.; Balakrishnan, V.; Nordin, F.; Norazmi, M.; Tye, G. Effectiveness of Booster Vaccinations on the Control of COVID-19 during the Spread of Omicron Variant in Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).