1. Introduction

Individuals receive new information through

communications with their peers and mass media outlets. While proceeding with

new messages, people reorganize their belief systems in an attempt to approach

logically coherent cognitive constructions in their minds (Banisch &

Olbrich, 2021; Zafeiris, 2022). However, external information is rarely

unbiased. Facts and inferences based on them may be subject to inadvertent or

intended distortions. As a result, corrupted chunks of belief systems are

spreading across societies.

When social media began to appear, there was a

point of view that low-cost access to online information, not limited by

geographical and economical boundaries, should facilitate the formation of an

unbiased and faithful perception of the world (Baumann et al., 2020; Zafeiris,

2022). However, this never happened—social networks are divided into

conflicting groups of individuals espousing similar views, so that people in

these groups (aka echo-chambers) rarely have access to challenging messages,

preferring to consume information that aligns their opinions (Bail et al.,

2018). As a result of such segregation, disagreement, polarization, and fake

news persist in societies (Dandekar et al., 2013; Haghtalab et al., 2021).

Longstanding debates around possible reasons for

such social phenomena are going on in the scientific community. Among other

explanations, scholars hypothesize individuals’ intrinsic cognitive

mechanisms—selective exposure (the tendency to avoid information that could

bring any form of ideological discomfort) and biased assimilation (when new

information is perceived in a form that aligns existing belief systems) (Haghtalab

et al., 2021). Next, the online domain is subject to moderation by ranking

algorithms that may push people into closed information loops with no access to

challenging content (Rossi et al., 2021).

It is worth noting that interactions in the online

environment differ from those in the offline world because online platforms

provide a rich set of specific communication tools (Perra & Rocha, 2019).

First, apart from private text messages, it could be messages with media

content (images, videos, music). Further, most online platforms provide the

opportunity to participate in public conversations whereby users can

display their thoughts overtly, thus making them visible to a huge audience.

Such public discussions are usually structured into specific tree-like

hierarchies in which rooted messages (posts, tweets, etc.) are followed by replies/retweets/comments/reposts

and different forms of evaluation displaying various types of emotions (likes,

dislikes, etc.). These structures—information cascades—can grow very rapidly

achieving thereby large audiences in a very short time (Goel et al., 2012).

Information cascades constitute the spine of the

public online information environment, reflecting its various trends, evolving

with it, and affecting its development. While users participate in online

discussions, they display their views and thus contribute to the growth of

cascades. At the same time, users’ opinions are affected by cascades’ contents.

It is worth noting that due to the large sizes of cascades and users’ limited

attention (Weng et al., 2012), each individual is able to attend only a limited

number of a cascade’s elements. Further, the order of these elements when they

appear in a user’s news feed is governed by the social network’s ranking

systems (Peralta et al., 2021).

To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies

that capture all the points raised above. Some papers have already concerned

the issue of users’ interactions in the online domain subject to moderation by

personalization systems (Maes & Bischofberger, 2015; Perra & Rocha,

2019; Rossi et al., 2021). However, all these studies were drawn from minimal

models of online interactions, ignoring the rich nature of online communication

tools. The current paper aims to advance our knowledge regarding these social

phenomena by developing an agent-based model in which agents participate in a

discussion around a post on the Internet. While agents display their opinions

by writing comments to the post and liking them (i.e., leaving positive

evaluations), they also contribute to the development of the corresponding

information cascade. At the same time, agents update their views as they

communicate with the cascade’s contents. And what is important, all these

processes are governed by a ranking algorithm that decides which comments will

appear in agents’ news feeds first. Using this model, we attempt to figure out

what crucial factors determine macro-scale outcomes of opinion dynamics that

unfold in information cascade settings.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 lists a relevant literature. In Section 3 , we elaborate on the model. Section 4 describes the design of numerical

experiments, and Section 5 presents their

results. Section 6 makes concluding

remarks. The appendix includes supporting information.

2. Literature

To date, a huge number of opinion dynamics models have

been elaborated; we refer the reader to excellent review papers (Flache et al.,

2017; Mäs, 2019; Mastroeni et al., 2019; Noorazar, 2020; Peralta et al., 2022;

Proskurnikov & Tempo, 2017, 2018; Vazquez, 2022). Relatively recently, such

models started to account for the fact that online interactions differ from

those unfolding in the offline world and are hardly influenced by ranking

1

algorithms—specific intelligent systems incorporated in social media platforms

that affect the order in which new content appears in users’ news feeds.

Ranking algorithms base their decisions on the information in a user’s profile,

the history of the user’s actions on the Internet, and current trends in the

online domain: if a message is rapidly emerging as popular, then it will be

suggested to users foremost, as there is a high probability that it will get

positive evaluation from them. One of the main objectives of ranking algorithms

is to ensure that users will appreciate the time they spend on the platform and

thus do so repeatedly.

A nearly first attempt to investigate how ranking

algorithms affect opinion formation dates back to Ref. (Dandekar et al., 2013),

where the authors analyzed the polarizing effects of several prominent

recommendation algorithms. The Ref. (Maes & Bischofberger, 2015) focused on

the interplay between a recommendation algorithm (operationalized as a parameter

that measures to what extent like-minded individuals have more chances to

communicate) and two alternative opinion formation models (the rejection model

and the persuasion model) in order to figure out what opinion dynamics

mechanisms lead to opinion polarization. They demonstrated that the emergence

of polarization sufficiently depends on what social influence mechanisms are

implemented. In the case of the persuasion model, if the effect of the ranking

algorithm is strong, then opinion polarization will proliferate. In turn, the

rejection model leads to a consensus in the same situation. Perra & Rocha

(2019) investigated how different ranking algorithms affect opinion dynamics by

controlling for basic network features. They revealed that the effect of

ranking algorithms is reinforced in networks with topological and spatial

correlations. De Marzo et al. (2020) upgraded the classical Voter model (Clifford

& Sudbury, 1973) with a recommendation algorithm that with some

probability, on each iteration, replaces the standard Voter model protocol by

exposing an interacting agent to an external opinion that is designed to be

maximally coherent to the agent’s current opinion. For this advanced model, the

authors obtained a mean-field approximation and derived conditions under which

a consensus state can be achieved. In (Rossi et al., 2021), the authors

developed a model in which an agent communicates with an online news

aggregator. They showed that ranking algorithms, while pursuing their

commercial purposes, make users’ opinions more extreme. The Ref. (Peralta et

al., 2021) demonstrated that the macroscopic properties of opinion dynamics are

seriously affected by how agent interactions are organized: in the case of

pairwise interactions, ranking algorithms contribute to polarization, whereas

group interactions do not display the same tendency. The empirical study by Huszár

et al. (2022) showed that ranking algorithms treat various information sources

differently, with statistically significant variations along political lines.

The Ref. (Santos et al., 2021) analyzed the effect of link recommendation

algorithms (that moderate the dynamics of the social graph connecting users) on

opinion polarization. They obtained that algorithms that rely on structural

similarity (measured, for example, as the number of common online friends),

enhance the creation of unintentional echo-chambers and thus strengthen opinion

polarization.

All these papers ignored the fact that users’

interactions in online public debates are structured into complex tree-like

structures—information cascades. Apparently, it is conditioned by the fact that

information cascades (and other issues of information diffusion in the online

domain) are historically studied by a different research branch whereby

approaches from the percolation and social contagion theories are widely used (Aral

& Walker, 2011; Centola & Macy, 2007; Goel et al., 2012; Iribarren

& Moro, 2011; Juul & Ugander, 2021; Liben-Nowell & Kleinberg, 2008).

In this paper, we try to combine these perspectives by elaborating an

agent-based model that, on the one side, describes opinion dynamics of

interacting agents and, on the other side, accounts for threshold effects and

the rich nature of online information diffusion processes.

As a final remark, we would like to say that the

way users see these cascades is also subject to the moderation of specific

ranking algorithms that decide which comments/replies should be seen foremost.

Despite previous studies successfully examining how ranking algorithms affect

opinion formation by implementing them in unstructured news feeds, the

current paper presents the first (to the best of our knowledge) attempt to

investigate how opinion forms in a highly structured information

space.

3. Model

We consider a group of agents who participate in an online discussion on

a social network. This discussion grows around a post published by an information source (say, by a

social media account of a news outlet). The post bears a message, which is

characterized by an opinion that belongs to an opinion space whereby variables represent an opinion alphabet . One could

think of these opinions as arranged in such a way that the first and the last

elements and stand for polar positions, whereas the middle

opinion represents a neutral stance. More complex

interpretations are also allowed.

Agents start the discussion by being assigned

opinions that are also conceptualized as elements of the space . Following online interactions, agents may change

their views, whereas the opinion of the post remains constant. Agents interact

with each other by translating their views via special actions allowed

by the online platform. Model dynamics proceed in a discrete time: . At time , the post appears, and agents’ opinions are

initialized. After that, at each time moment , a randomly chosen agent communicates with their

news feed. Two actions are allowed for the agent: (1) write a reply (comment)

to the post/comment and (2) like the post/comment. Therefore, each comment at time is characterized by the number of replies and likes it has been received by this time. The post is characterized by the similar quantities and . Note that and counts only direct replies. As a result of agents’

actions, new comments and likes appear—the information cascade is growing.

Let us assume that at time , agent is selected. At this moment, they observe the news

feed —an online display that contains textual elements

(the post, comments) from the cascade arranged in some way as well as

associated metrics demonstrating the corresponding numbers of likes/replies.

The agent proceeds the news feed in a sequential fashion, starting from the

first element (which is always the post: ). The order of the news feed elements is subject

to a ranking algorithm, which will be introduced below. It is important to

clarify that the news feed essentially includes all the cascade textual

elements (numbered as ). However, the agent may not be willing to attend

all of them—it could be the case that they do not have enough time for this or,

say, the topic of discussion is not important for this particular agent. As

such, to define the agent’s behavior, one should pinpoint what of the cascade

elements will be attended to by the agent. We denote the set of these elements

by . It is worth noting that may be subject to dynamical updates as a result of

the agent’s communications—for example, because of changes in the agent’s level

of engagement in the discussion (as the agent’s opinion becomes more extreme,

the agent may want to discuss the topic at stake fiercely).

While proceeding with an element from the news feed, agent may:

*Change

their opinion.

*Put

a like on the element.

*Write

a reply to the element.

These options are not mutually exclusive. The order

of these events can vary, but it would be meaningful to assume that the agent

updates their opinion first. The motivation behind this assumption is that,

prior to displaying any reaction, the agent should first read the message.

While reading the text, the agent updates their views according to the

arguments presented in the message. After that, the agent may put a like on the

element and write a reply. We assume that the order of these two reactions is

subject to the model’s specification. As a basic configuration, we will suppose

that the like appears first (as an estimation that does not require much time

and cognitive resources to be displayed) and that only after that the agent may

write the reply.

3.1. Opinion Update Protocol

Following the approach from Ref. (Kozitsin, 2022),

we model opinion updates as a function of the focal agent’s opinion and the

element’s properties. Being exposed to the textual element of the news feed,

the agent can switch its current opinion

to one of

alternatives

with some probabilities that add up to one. These

probabilities may depend on the agent’s and the element’s opinions or, say, on

the number of likes the element has. In Ref. (Kozitsin, 2022), the author

outlined that the probability of an opinion update

, subject to the influencing opinion is

, is determined by a quantity

, where the lower indices

are synchronized with the lower indices of the

interacting opinions

and the potential opinion

. The variables

constitute a 3D mathematical construction

, which was called the transition matrix in

Ref. (Kozitsin, 2022). In fact, this object is not a matrix per se: many matrix

operations are not applicable here. In this regard, we will adopt a different

notation strategy throughout this paper, and we will refer to

as to the transition table . The components

of the transition table meet the restriction

for any fixed

and

. The transition table can be straightforwardly

represented as a list of square row-stochastic matrices:

where

the matrix

encodes

how agents with the opinion

reacts

to social influence:

This approach can be modified to account for the

fact that our perception of the post/comment may depend not only on its

opinion, but also on how other individuals perceive this object. For example,

if a person notices that a comment has acquired many likes, the person receives

the signal that the society appreciates this message. In this regard, they will

likely adopt the message’s opinion attempting to conform to society’s norms (Cialdini

& Goldstein, 2004). The social contagion theory posits that the probability

of accepting the message is positively associated with the number of positive

appraisals the message has received, and empirical studies witness that the

dependency typically features a diminishing returns character (Centola, 2010;

Christakis & Fowler, 2013; Guilbeault & Centola, 2021). These ideas can

be incorporated into our framework by adding a special term to the transition

table’s elements, which is responsible for the effect of social contagions:

where a monotonically increasing (upward convex)

function represents the social contagion factor (it is assumed

that ). In this case, the probability depicts the situation when the agent is exposed to

the message that has not been liked by anyone yet.

As agents communicate, their opinions evolve. This

process can be monitored both at the individual and the macroscopic levels. To

investigate opinion dynamics at the macroscopic level, we use the quantities . Thus said, represents the number of agents having opinion at time .

3.2. Replies and Likes

Let us now outline how agents display reactions to

textual messages. Still, we follow the probabilistic framework by encoding

agents’ behavior using specific probability distributions. First, we assume

that if the agent writes a reply, then the agent’s opinion is translated into

the message. In principle, it is also possible to introduce a specific alphabet

of textual opinions, accounting for the fact that our views cannot be

transferred into textual form without any deformations (from this perspective,

the opinion of the post should also be represented using this textual alphabet)

(Carpentras et al., 2022). However, we not do so here and assume that both

agents’ opinions and textual messages are elements of the same opinion

alphabet. We now introduce the probability

that a user with opinion

will write a reply to the post/comment with

opinion

. Grouping these quantities into the matrix

(hereafter – the Reply matrix )

we get a full description of agents’

textual-reaction behavior. Within this notation strategy, denotes how often agents with opinion response to like-minded messages whereas and encode the chances of replying to messages with

opposite stances. In this paper, we do not account for the semantic facets of

textual messages. However, one can think of responses to opposite opinions as

those that translate negative emotions and represent animosity (hostile

replies). In turn, replies to similar opinions are likely to bear positive

sentiments (supporting replies).

Elaborating analogously, we introduce the Like

matrix

whose entry

is the probability that an agent with opinion

will put a like on a message with opinion

. Because the act of liking tends to display a

positive evaluation, it would be rational to suppose that the like matrix’s

elements should occupy predominantly the main diagonal, showing thus that

agents tend to like content that aligns with their views

2

In contrast, in the Reply matrix, elements beyond the main diagonal can appear

to be positive, indicating individuals’ intentions to debate with challenging

arguments. For the sake of brevity, we will refer to the Reply and Like

matrices as to the Activity matrices. Note that the Activity matrices are not

restricted to being row-stochastic.

The Activity matrices can also be modified to

account for the social contagion factor in a similar fashion as the transition

table. For example, we can outline that the components of the Like matrix are

additively incremented by a special term

, which governs agents’ sensitivity towards how the

audience evaluates the post/comment. As a result, the probability that an agent

with opinion

will put a like on the post/comment with opinion

that has

likes, is given by

where the quantity describes the situation when the post/comment has

no likes (we assume that ).

These specifications end the description of the

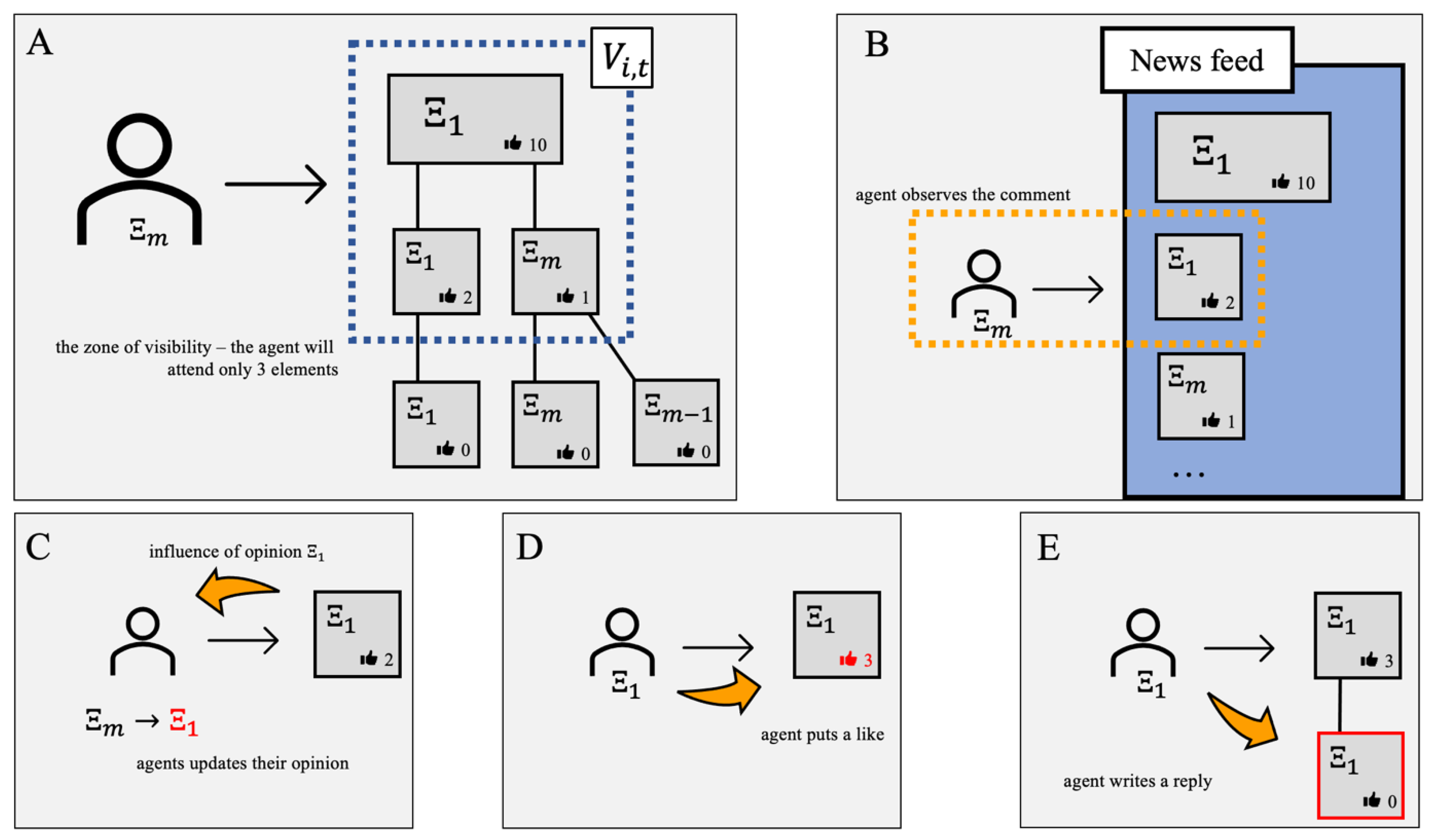

model. Its sketch is depicted in Figure 1 .

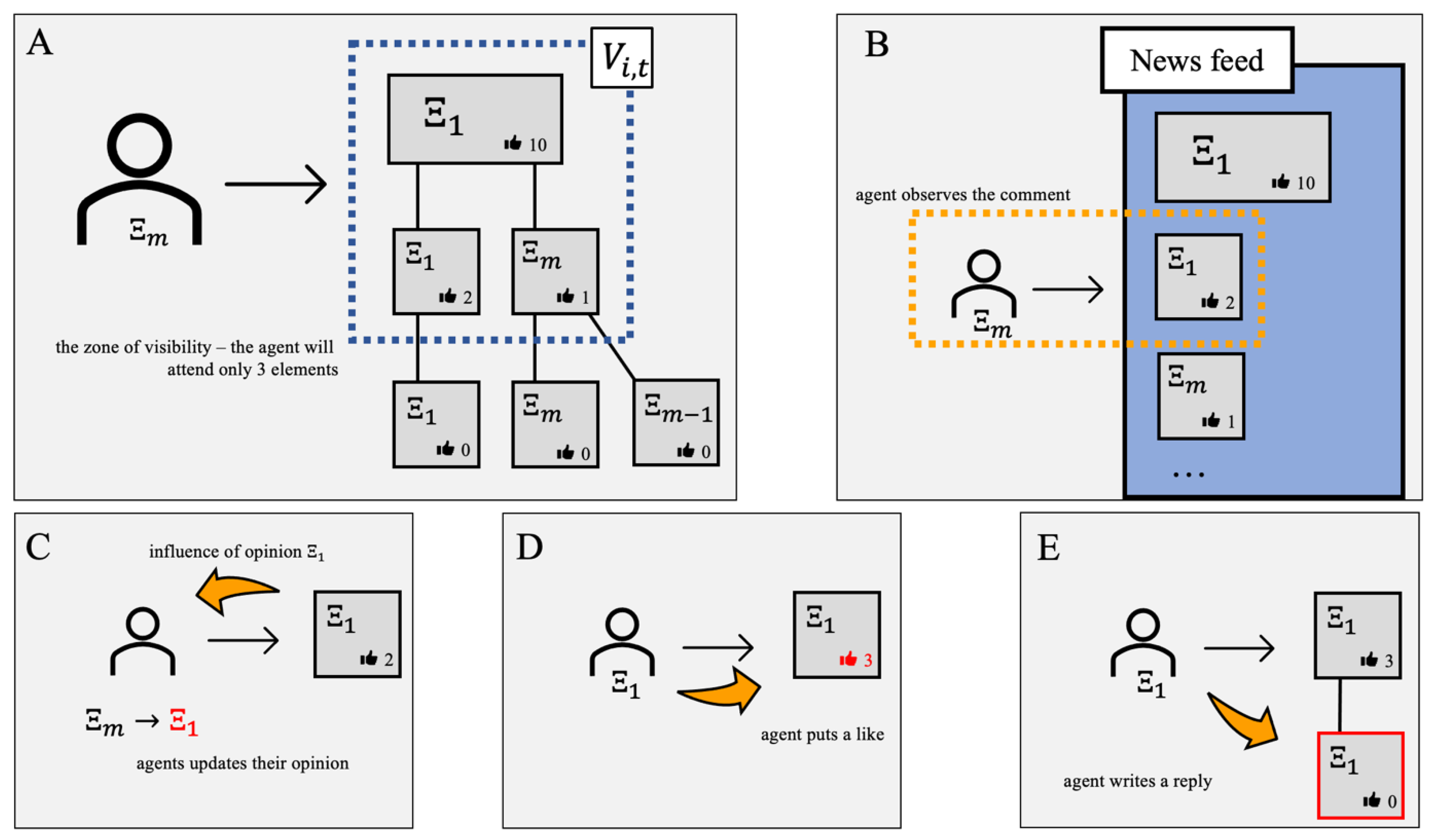

Figure 1.

(Panel A). We investigate how an agent with opinion (rightist) participates in the discussion

initiated by a leftist post with opinion (large rectangle). After being selected at some

time , the agent observes the news feed (see panel B),

whose elements (the number of which equals 6 – see panel A) are prioritized

according to the number of likes. The zone of visibility of the agent () includes only three elements—the post and two

comments that are direct replies to the post (see panels A and B). These two

comments were chosen by the ranking algorithm because they have more likes than

others. In this example, the agent does not change their opinion and does not

display any reactions after reading the post. Instead, the second element of

the news feed (the leftist comment with two likes) makes the agent change their

opinion (panel C), induces a like reaction (panel D), and receives a reply from

the focal agent (in which the agent translates their newly formed opinion )—see panel E. All updates are highlighted in red.

As a result, the information cascade is replenished with one more comment, one

of its previous comments receives one additional like, and the opinion of the

selected agent is flipped to the opposite side.

Figure 1.

(Panel A). We investigate how an agent with opinion (rightist) participates in the discussion

initiated by a leftist post with opinion (large rectangle). After being selected at some

time , the agent observes the news feed (see panel B),

whose elements (the number of which equals 6 – see panel A) are prioritized

according to the number of likes. The zone of visibility of the agent () includes only three elements—the post and two

comments that are direct replies to the post (see panels A and B). These two

comments were chosen by the ranking algorithm because they have more likes than

others. In this example, the agent does not change their opinion and does not

display any reactions after reading the post. Instead, the second element of

the news feed (the leftist comment with two likes) makes the agent change their

opinion (panel C), induces a like reaction (panel D), and receives a reply from

the focal agent (in which the agent translates their newly formed opinion )—see panel E. All updates are highlighted in red.

As a result, the information cascade is replenished with one more comment, one

of its previous comments receives one additional like, and the opinion of the

selected agent is flipped to the opposite side.

4. Numerical Experiments

4.1. Baseline Settings

We use the model introduced above to investigate a

stylized situation in which a generally neutral population of agents are exposed to a radical post. We consider

an opinion alphabet with three elements () whereby opinions and are opposite radical positions whereas stands for the neutral stance. Without loss of

generality, we assume that the post has opinion . The initial opinion distribution is given by That is the majority of agents in the system hold

the neutral position, whereas the number of individuals with radical opinions (leftists) and (rightists) are balanced.

We assume that opinion updates are governed by the

following transition table:

According to (1), agents with radical positions are

not subject to opinion changes, whereas the neutral opinion can be reconsidered after communications with

leftists or rightists. However, this occurs in only 10 cases out of 100. Such

an assumption relies on empirical studies that witness the generally low

tendency of individuals to change their views and the high resistance to social

influence among individuals with strong opinions (Carpentras et al., 2022;

Kozitsin, 2021). What is important, we assume only assimilative opinion

shifts—agents cannot adopt opinions opposite to those they were exposed to (in

terms of the transition table, it means that ).

Next, we focus on the following Activity matrices:

which indicate that

-Only

leftists and rightists (that is, only individuals with clear positions) can

take part in public debates and thus contribute to the information cascade,

whereas neutral individuals are silent (until they change opinions).

-Agents

put likes only on those messages with opinions similar to their own.

-Agents

may reply to cross-ideological messages, but they do it two times less

frequently than they reply to coherent messages.

-The

probability of a like is at least three times greater that the chance of

writing a comment.

All these patterns are empirically motivated and

can be observed in real life. For example, users far more often put likes than

comments on social media. Perhaps only the one assumption—regarding the balance

between cross-ideological and coherent replies—may raise some concerns, but we

will proceed from the notice that people prefer to avoid conflict situations

and communicate primarily with those espousing similar views, as reported by

empirical studies of online communication networks (Cota et al., 2019).

4.2. Social Contagions

We incorporate social contagions into our model by

adding adjustments to the Activity matrices, ignoring any modifications in the

transition table. This assumption relies on the general notion that threshold

effects are widely observed in how people perform physical actions

(express their opinions publicly, subscribe to mass media accounts, lead a

healthy lifestyle, and choose accommodations) (Aral & Nicolaides, 2017;

Schelling, 1969), whereas opinion formation processes (that concern the

transformation of internal individual characteristics) are moderated by

a different family of mechanisms (Flache et al., 2017). Amendments

and

in the Reply and Like matrices are defined as

where

and

, as well as their powers, represent the marginal

revenue from each additional like or reply. In agreement with the empirics (Backstrom

et al., 2006),

and

feature diminishing returns in the sense that the

marginal increment decreases as the number of likes or replies goes up. If the

number of likes or replies is huge, then we obtain:

4.3. Ranking Algorithms and Specification of the Visibility Zone

As was previously said, agents interact with each

other through an interface (the news feed), in which they observe the post and

comments sorted in a special fashion. The order of comments is defined by a

ranking algorithm. We consider three ranking algorithm specifications:

-“Time”

– comments are sorted according to their time of appearance, from the newest to

the oldest (this ranking algorithm is usually considered basic on social media

sites).

-“Likes

Count” – comments that have more likes appear at the top of the news feed.

-“Replies

Count” – comments are prioritized according to the number of direct replies.

The more replies a comment has, the higher its priority.

In fact, the real ranking algorithms that are

employed on social media sites are much more complex and account for a wide

range of metrics, including the history of users’ actions. However, our

approach gives us an opportunity to isolate the effects of some, perhaps

the most simple, metrics and study them separately—a similar methodology was

implemented in Ref. (Perra & Rocha, 2019).

Apart from defining the organization of the news

feed, we should also clarify how many of its elements a given agent

is willing to attend. The process of learning is a

complex operation, in which many factors govern the volume of information with

which the user is able to proceed, such as: cognitive constraints, the amount

of free time, the level of the user’s engagement in the discussion topic, etc.

In this paper, we will rely on the assumption that the majority of agents are

able to learn only a few news feed elements, whereas the number of agents who

can proceed with more comments decays exponentially. More specifically, we

define the size of

using the exponential distribution:

To avoid situations where this random variable is

non-integer, we round it down and then increment by one. By doing so, we ensure

that at least one of the elements of the news feed (the post, which is always

located at the top) will be looked at. Besides, we assume that while proceeding

with the news feed, the agent does not skip its elements. As a result, they

learn the first elements of the news feed.

4.4. Experiment Design

Dynamics of the social system presented above can

be understood as a competition between the left () and right () opinions. Settings introduced in the previous

subsection imply that the competing opinions have no advantage over each

other—the transition table and the activity matrices are symmetric with respect

to the radical positions. However, the left opinion has one sticking privilege—it is translated by the

post and thus each agent when observing the news feed, is first exposed to . As a result, in the long run, the left opinion

should prevail. Inspired by this observation, we focus on answering the following

questions:

(Q1) “What way should the rightists alter their

activity rates to turn things around?”

(Q2) “What way should the rightists modify the

persuasiveness of their arguments which they use to influence neutral agents to

facilitate proliferation of the right opinion?”

(Q3) “What way should the rightists alter their

presence in discussion to turn things around?”

(Q4) “How the presence of social contagions,

strength of cognitive constraints, and the type of the ranking algorithm affect

the outcome of the opinion competition?”

From a mathematical point of view, our purpose is

to find a hyperplane in the parameter space that marks the draw in the opinion

competition. To address the questions formulated above, we conduct Monte-Carlo

simulations in which the one-variable-at-a-time approach is applied. We

manipulate the Activity matrices via the variables

and

(question Q1) just as follows:

Parameter alters the probability of writing a reply to the

hostile opinion , regulates the probability of replying to the

coherent opinion , changes the probability of liking opinion , and varies the probability of liking the congruent

opinion .

Next, we isolate the effect of opinion

’s persuasiveness (question Q2) by introducing the

parameter

in the following fashion:

In other words, the greater is , the more often neutral agents adopt after being exposed to this opinion.

The question Q3 is addressed just by controlling

the initial opinion distribution as the total number of agents is fixed.

While altering all these parameters, we also

control for the social contagion factor and type of the ranking algorithm. The

former covariate is operationalized via two stylized situations: (i)

and (ii)

. The second case covers the settings when there

are no social contagions. In turn, in the first case, the Activity matrices are

subject to amendments that depend on the post’s /comment’s metrics. It is

straightforward to calculate that, in this case, the probability of writing a

reply to the post/comment with a huge number of replies is described by the

following the Reply matrix:

Analogously, a comment/post that has already received many likes will get one more according to the following Like matrix:

The issue of cognitive constraints is operationalized via two regimes: (i)

(strong cognitive constraints) and (ii)

(weak cognitive constraints). We recognize that the term “cognitive constraints” is not fully correct here as other factors different from cognitive limitations do also affect the value of

, but for the sake of simplicity we will adopt this terminology. In Appendix (see

Figure A1), we show the distributions of

that appear in these two regimes.

Each experiment lasts until the agents’ opinions converge (it happens when the faction of neutral agents disappears). Each simulation run is associated with the convergence time and the quantity (the dependent variable) that signifies the relative advantage of opinion over after iterations. For each combination of parameters, we perform 100 independent experiments. In ongoing analysis, if we say “the draw can be achieved”, it means that the value of the dependent variable averaged over independent simulations equals 0.

5. Results

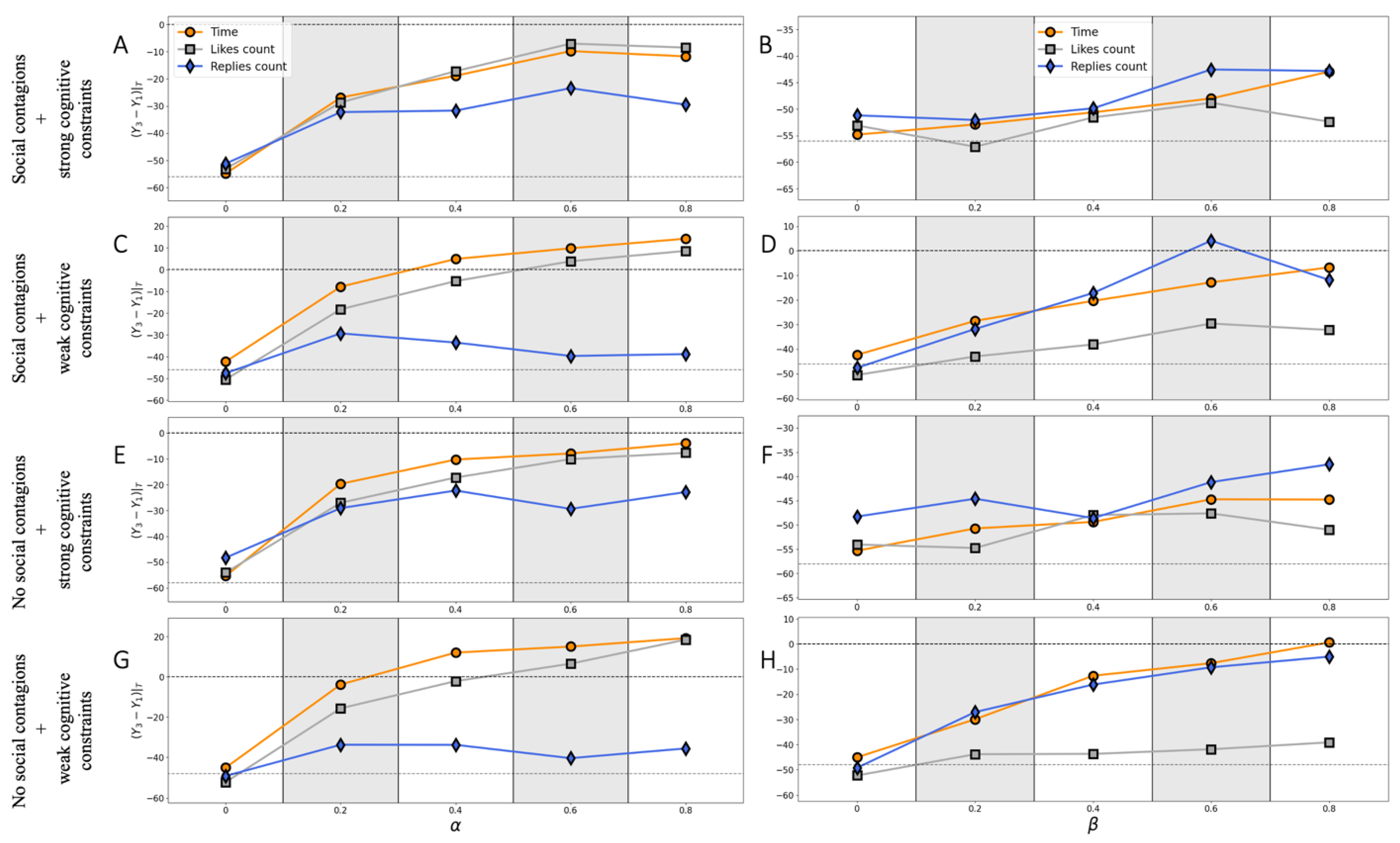

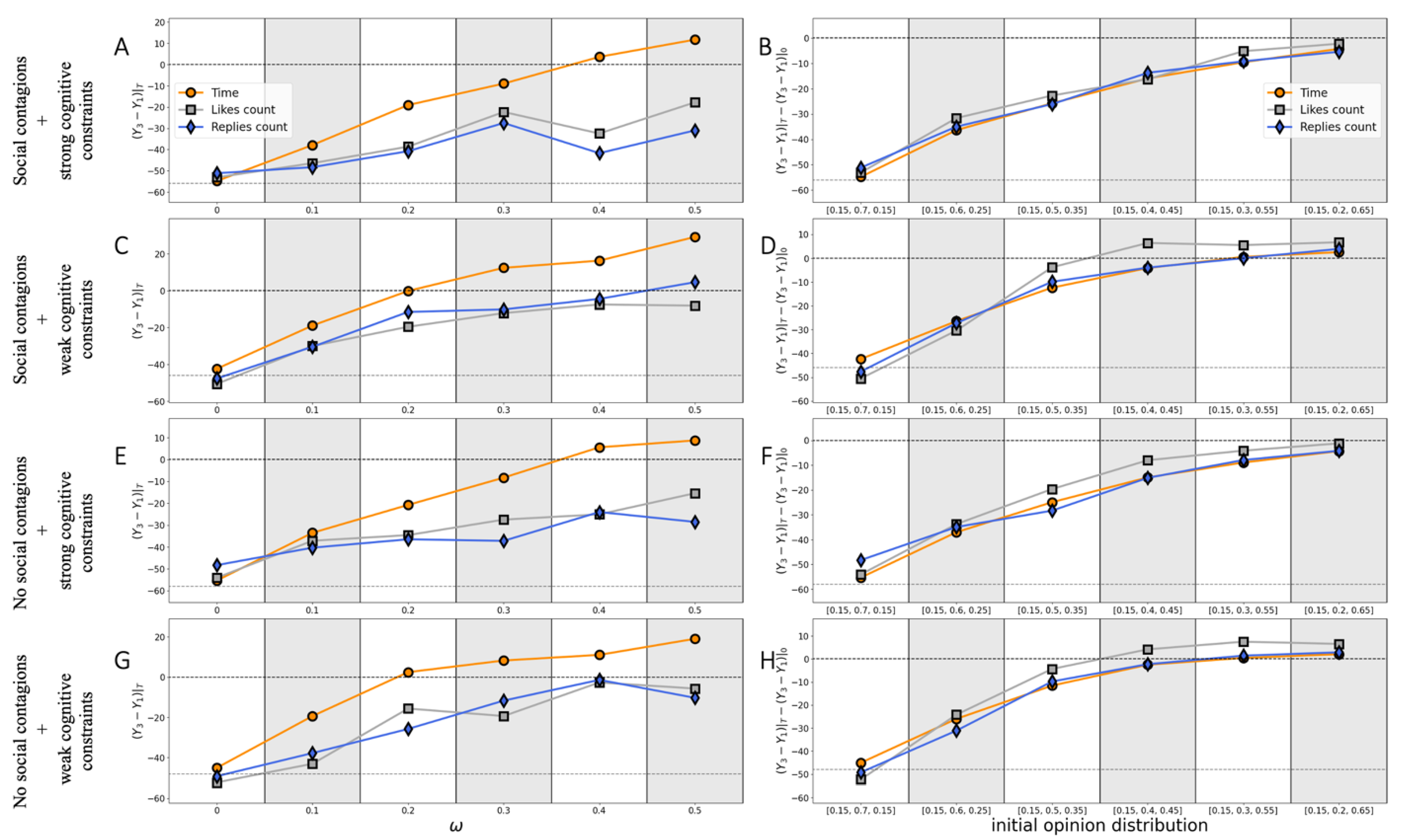

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show how the result of the discussion depends on how active the rightists are. More precisely,

Figure 1 investigates the effect of reply activity, whereas

Figure 2 outlines that of like activity. We see that the most straightforward way for rightists to mitigate the dominance of the left opinion is to write comments more often. What is important, replies to the disagreeable opinion

are most effective – see panels A, C, E, G. However, the draw is more real in the case of weak cognitive constraints (see panels C, G). More detailed analysis (see Figure A 2, Appendix) revealed that the presence of social contagions favors the leftists. Under the most propitious for rightists conditions (see panel G), the draw can be achieved at

(ranking algorithm: Likes Count) and

(ranking algorithm: Time). Apparently, if rightists reply to opposite comments more often, then the ranking algorithm Replies Count favors leftists as their comments become more visible to neutrals on this occasion. In contrast, panels D and H indicate that this ranking algorithm contributes to proliferation of right opinion in the case the rightists interact with congruent-opinion comments more often. The same can be said about the ranking algorithm Time. Again, the settings of weak cognitive constraints and absence of social contagions are more advantageous for rightists if the value of

goes up. However, in such settings, the draw can be achieved only at

(see panel H). Panel D, however, indicates that the draw becomes real at

(raking algorithm Replies Count), but the further increase in

leads to lower values of the dependent variable, indicating thus that this extremum could be just an artefact of statistical fluctuations.

Figure 1.

We study the effect of reply activity on the advantage of opinion over opinion after iterations (averaged over 100 independent simulation runs). The left panels show how replies to opposite comments (with opinion ) condition the dependent variable, whereas the right panels showcase how the outcome of the opinion competition varies with how frequently agents reply to comments with congruent opinion . On each subplot, two dashed lines signify (i) the draw () and (ii) the median value of the dependent variable in the case the Activity matrices hold the baseline configuration given by (2).

Figure 1.

We study the effect of reply activity on the advantage of opinion over opinion after iterations (averaged over 100 independent simulation runs). The left panels show how replies to opposite comments (with opinion ) condition the dependent variable, whereas the right panels showcase how the outcome of the opinion competition varies with how frequently agents reply to comments with congruent opinion . On each subplot, two dashed lines signify (i) the draw () and (ii) the median value of the dependent variable in the case the Activity matrices hold the baseline configuration given by (2).

Figure 2 clearly indicates that the potentiation of like activity cannot strengthen positions of rightists. To some extent, this result is counterintuitive—we hypothesized that if rightists were more active in supporting their comments with likes, then, in the case of the ranking algorithm Likes Count, right-opinion comments would become more visible and thus affect more neutral agents. Indeed, positive relationships between the quantity

and the value of

can be found on panels C, E, and G in

Figure 2 (see the gray curves). However, these curves are very far from the line

that fixes the draw.

Figure 2.

We study the effect of like activity on the advantage of opinion over opinion after iterations (averaged over 100 independent simulation runs). The left panels show how likes to opposite comments (with opinion ) condition the dependent variable, whereas the right panels showcase how the outcome of the opinion competition varies with how frequently agents like comments with coherent opinion . On each subplot, the dashed line showcases the median value of the dependent variable in the case the activity matrices hold the baseline configuration defined by (2). The line (the draw) did not fit into the figure.

Figure 2.

We study the effect of like activity on the advantage of opinion over opinion after iterations (averaged over 100 independent simulation runs). The left panels show how likes to opposite comments (with opinion ) condition the dependent variable, whereas the right panels showcase how the outcome of the opinion competition varies with how frequently agents like comments with coherent opinion . On each subplot, the dashed line showcases the median value of the dependent variable in the case the activity matrices hold the baseline configuration defined by (2). The line (the draw) did not fit into the figure.

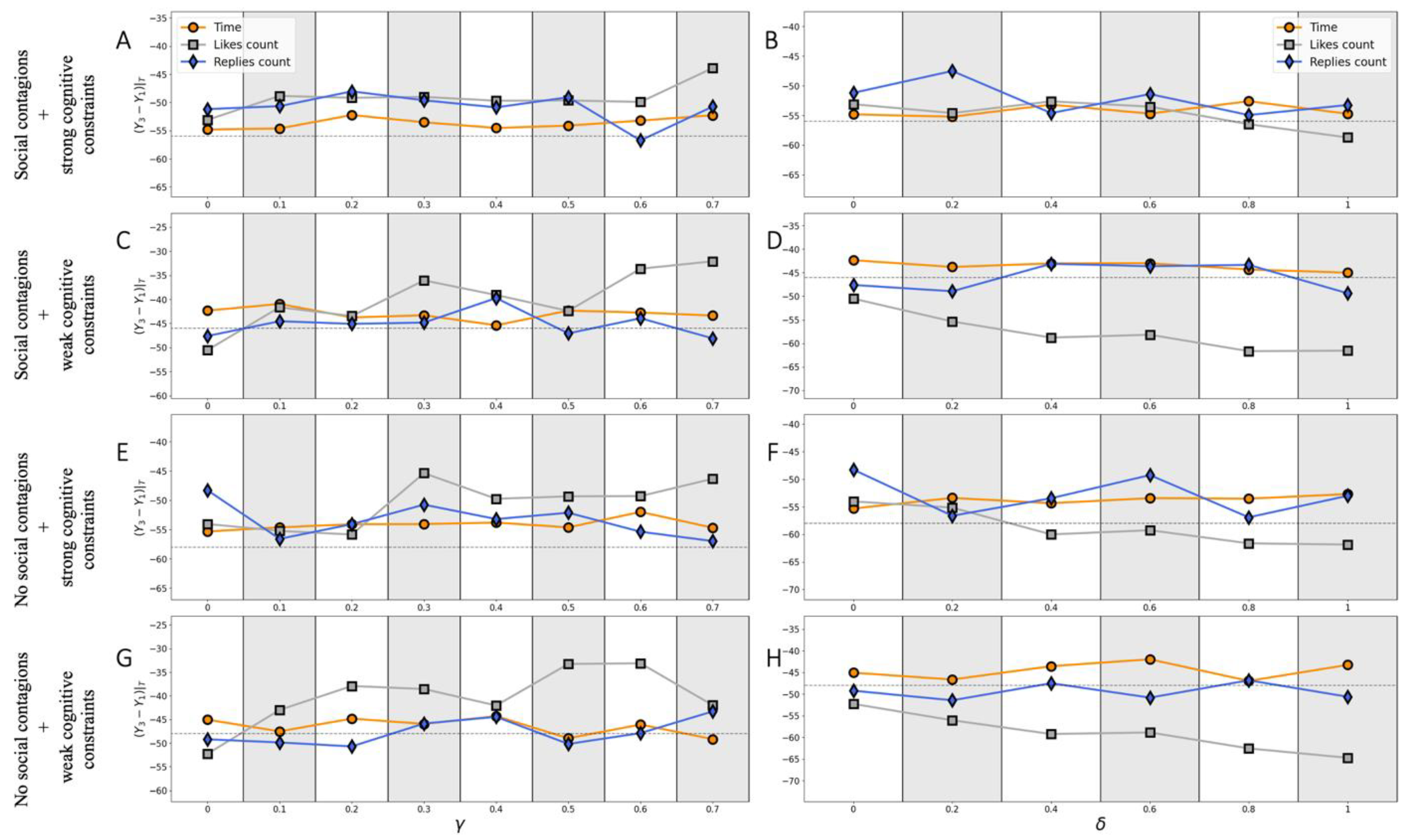

The left panels of

Figure 3 demonstrate how the changes in the transition table related to the growth of the persuasiveness of rightists affect the final opinion distribution. As expected, the more influential the rightists are, the larger is the value of the dependent variable. We report that the ranking algorithm Time more favors rightists than other algorithms on this occasion. The critical value at which the draw appears strongly depends on how strong the cognitive constraints are. Weak cognitive constraints make draw more feasible for rightists: such settings ensure the draw at

regardless of the presence of social contagions (subject to the ranking algorithm Time is in charge). Note that setting

leads to the following transition table:

Figure 3.

The left panels (A, C, E, and G) of this figure investigate the effect of the persuasiveness of rightists on the outcome of the discussion, measured as the advantage of opinion over opinion after iterations (averaged over 100 independent simulation runs). The right panels (B, D, F, and H) study how the initial opinion distribution impacts the outcome of conversations. However, since the system is not opinion-balanced at the beginning on this occasion, we now use a different dependent variable: , which accounts for the fact that the initial number of rightists can be greater than that of leftists[3]. On each subplot, two dashed lines signify (i) the draw (when the dependent variable is zero) and (ii) the median value of the dependent variable in the case the activity matrices hold the baseline configuration defined by (2).

Figure 3.

The left panels (A, C, E, and G) of this figure investigate the effect of the persuasiveness of rightists on the outcome of the discussion, measured as the advantage of opinion over opinion after iterations (averaged over 100 independent simulation runs). The right panels (B, D, F, and H) study how the initial opinion distribution impacts the outcome of conversations. However, since the system is not opinion-balanced at the beginning on this occasion, we now use a different dependent variable: , which accounts for the fact that the initial number of rightists can be greater than that of leftists[3]. On each subplot, two dashed lines signify (i) the draw (when the dependent variable is zero) and (ii) the median value of the dependent variable in the case the activity matrices hold the baseline configuration defined by (2).

Finally, we investigate if the outcome of the opinion competition can be challenged by increasing the number of rightists in the discussion. From panels B, D, F and H in

Figure 3, we conclude that the rightists should have a significant numerical advantage to combat the effect of the left-opinion post. Panels D and H indicate that in the case of weak cognitive constraints and under the assumption that the ranking algorithm

Likes Count moderates news feeds, the draw can be achieved if the discussion starts from the opinion distribution

. That is, the number of rightists should be comparable to the number of neutral agents. Other settings are less favorable for rightists.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

In general, our results demonstrate that, despite the initial advantage of leftists (ensured by the influence of the rooted message (the post) that bears the left opinion), the rightists would have more success in the discussion if the agents were able to proceed with more information. Further, we obtained that the ranking algorithm Time, which is unbiased to how popular comments are in terms of likes or replies favors rightists in most situations. However, if rightists try to challenge the result of the discussion by increasing the number of their coalition, then the ranking algorithm Likes Count will be more appropriate. We also report that social contagions typically hamper the proliferation of the right-side position.

In various scenarios, we found the critical values at which the advantage of the left opinion in the discussion disappears. Among other things, we found that replies to opposite comments have an extremely strong effect on the outcome of the opinion competition. In turn, our results indicate that like activity is rather insignificant.

It is worth noting that we did not discuss how the corresponding modifications in the parameter space can be achieved in reality. For example, from the technical point of view, changes in activity patterns or the numerical relation between opinion camps seem more feasible than an increase in persuasiveness. In the first two cases, rightists should just consolidate their efforts (call like-minded persons for help) and behavior (for example, write replies to hostile comments more often), whereas any modifications in the transition table require more subtle behavioral transformations.

The current paper concerned only one stylized situation when a discussion unfolds around one post on the Internet. We did not touch more realistic scenarios where posts appear one after another, as it happens on social media sites. Besides, there could be several conflicting mass media accounts that may fight for followers. Further, we did not include in the model social bots that may act strategically and in a coordinated manner. Such artificial accounts are not bound by cognitive constraints and may display abnormal activity. Further, they could be configured to give immediate answers to posts and thus be extremely effective in moderating the discussion. All these ideas constitute promising avenues for further model development.

Finally, we did not study the structure of the information cascades generated by our model. From this perspective, it would be interesting to compare cascades that appear in the model with those that were observed on social media sites throughout empirical studies (Iribarren & Moro, 2011; Juul & Ugander, 2021).

Data availability: Simulation experiments, visualization, and analysis were performed in JupiterHub using Python 3 language—see

https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FZOGGZ (Online Supplementary Materials).

8. Acknowledgment

The research is supported by a grant of the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 23-21-00408).

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Panel A shows the distribution of the number of attended elements in the case of the Strong cognitive constraints regime. Panel B stands for the regime of weak cognitive constraints.

Figure A1.

Panel A shows the distribution of the number of attended elements in the case of the Strong cognitive constraints regime. Panel B stands for the regime of weak cognitive constraints.

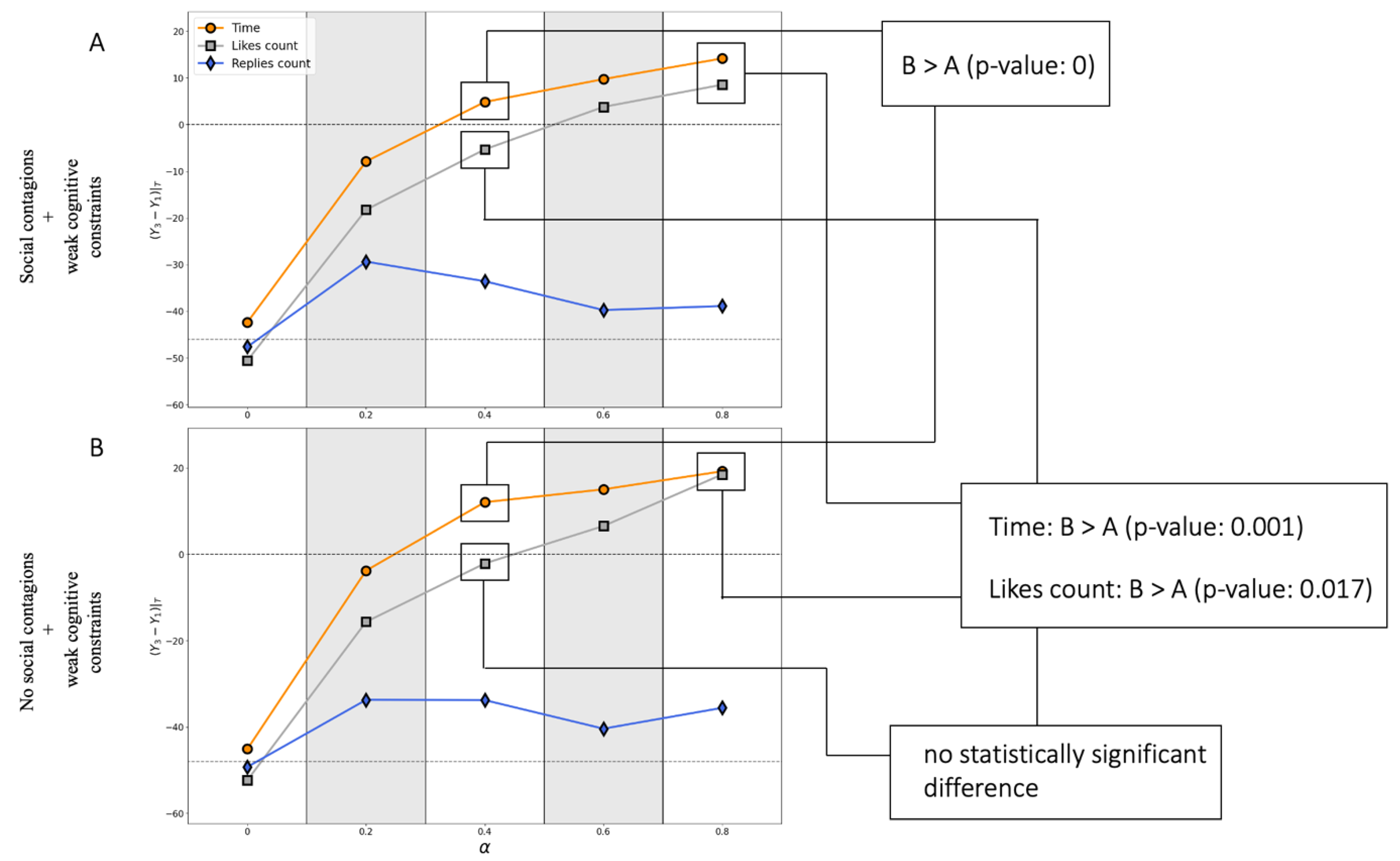

Figure A2.

This Figure replicates two panels from

Figure 1 (C and G). Using the Mann–Whitney U test, we compare distributions of the dependent variable obtained with social contagions (denoted A) and without (denoted B), other things being equal.

Figure A2.

This Figure replicates two panels from

Figure 1 (C and G). Using the Mann–Whitney U test, we compare distributions of the dependent variable obtained with social contagions (denoted A) and without (denoted B), other things being equal.

References

- Aral, S., & Nicolaides, C. (2017). Exercise contagion in a global social network. Nature Communications, 8(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Aral, S., & Walker, D. (2011). Creating Social Contagion Through Viral Product Design: A Randomized Trial of Peer Influence in Networks. Management Science, 57(9), 1623–1639. [CrossRef]

- Backstrom, L., Huttenlocher, D., Kleinberg, J., & Lan, X. (2006). Group formation in large social networks: Membership, growth, and evolution. 44–54.

- Bail, C. A., Argyle, L. P., Brown, T. W., Bumpus, J. P., Chen, H., Hunzaker, M. B. F., Lee, J., Mann, M., Merhout, F., & Volfovsky, A. (2018). Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(37), 9216–9221. [CrossRef]

- Banisch, S., & Olbrich, E. (2021). An Argument Communication Model of Polarization and Ideological Alignment. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 24(1), 1. (.

- Baumann, F., Lorenz-Spreen, P., Sokolov, I. M., & Starnini, M. (2020). Modeling Echo Chambers and Polarization Dynamics in Social Networks. Physical Review Letters, 124(4), 048301. [CrossRef]

- Carpentras, D., Maher, P. J., O’Reilly, C., & Quayle, M. (2022). Deriving an Opinion Dynamics Model from Experimental

Data. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 25(4), 4.

- Centola, D. (2010). The spread of behavior in an online social network experiment. Science, 329(5996), 1194–1197. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Centola, D., & Macy, M. (2007). Complex Contagions and the Weakness of Long Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 113(3), 702–734. 3. [CrossRef]

- Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2013). Social contagion theory: Examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Statistics in Medicine, 32(4), 556–577. [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 55, 591–621.

- Clifford, P., & Sudbury, A. (1973). A model for spatial conflict. Biometrika, 60(3), 581–588.

- Cota, W., Ferreira, S. C., Pastor-Satorras, R., & Starnini, M. (2019). Quantifying echo chamber effects in information spreading over political communication networks. EPJ Data Science, 8(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Dandekar, P., Goel, A., & Lee, D. T. (2013). Biased assimilation, homophily, and the dynamics of polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(15), 5791–5796.

- De Marzo, G., Zaccaria, A., & Castellano, C. (2020). Emergence of polarization in a voter model with personalized information.

Physical Review Research, 2(4), 043117.

- Flache, A., Mäs, M., Feliciani, T., Chattoe-Brown, E., Deffuant, G., Huet, S., & Lorenz, J. (2017). Models of Social Influence: Towards the Next Frontiers. Journal of Artificial Societies & Social Simulation, 20(4).

- Goel, S., Watts, D. J., & Goldstein, D. G. (2012). The structure of online diffusion networks. Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Electronic Commerce, 623–638. [CrossRef]

- Guilbeault, D., & Centola, D. (2021). Topological measures for identifying and predicting the spread of complex contagions. Nature Communications, 12(1), 4430. [CrossRef]

- Haghtalab, N., Jackson, M. O., & Procaccia, A. D. (2021). Belief polarization in a complex world: A learning theory perspective. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(19). [CrossRef]

- Huszár, F., Ktena, S. I., O’Brien, C., Belli, L., Schlaikjer, A., & Hardt, M. (2022). Algorithmic amplification of politics on Twitter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(1). [CrossRef]

- Iribarren, J. L., & Moro, E. (2011). Branching dynamics of viral information spreading. Physical Review E, 84(4), 046116. (. [CrossRef]

- Juul, J. L., & Ugander, J. (2021). Comparing information diffusion mechanisms by matching on cascade size. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(46). [CrossRef]

- Kozitsin, I. V. (2021). Opinion dynamics of online social network users: A micro-level analysis. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 0(0), 1–41. [CrossRef]

- Kozitsin, I. V. (2022). A general framework to link theory and empirics in opinion formation models. Scientific Reports, 12(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Liben-Nowell, D., & Kleinberg, J. (2008). Tracing information flow on a global scale using Internet chain-letter data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(12), 4633–4638.

- Maes, M., & Bischofberger, L. (2015). Will the Personalization of Online Social Networks Foster Opinion Polarization? Available at SSRN 2553436.

- Mäs, M. (2019). Challenges to Simulation Validation in the Social Sciences. A Critical Rationalist Perspective. In C. Beisbart & N. J. Saam (Eds.), Computer Simulation Validation: Fundamental Concepts, Methodological Frameworks, and Philosophical Perspectives (pp. 857–879). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Mastroeni, L., Vellucci, P., & Naldi, M. (2019). Agent-Based Models for Opinion Formation: A Bibliographic Survey. IEEE Access, 7, 58836–58848. [CrossRef]

- Noorazar, H. (2020). Recent advances in opinion propagation dynamics: A 2020 survey. The European Physical Journal Plus, 135(6), 521. [CrossRef]

- Peralta, A. F., Kertész, J., & Iñiguez, G. (2022). Opinion dynamics in social networks: From models to data. ArXiv:2201.01322 [Nlin, Physics:Physics]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2201.01322.

- Peralta, A. F., Neri, M., Kertész, J., & Iñiguez, G. (2021). Effect of algorithmic bias and network structure on coexistence, consensus, and polarization of opinions. Physical Review E, 104(4), 044312. [CrossRef]

- Perra, N., & Rocha, L. E. (2019). Modelling opinion dynamics in the age of algorithmic personalisation. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–11.

- Proskurnikov, A. V., & Tempo, R. (2017). A tutorial on modeling and analysis of dynamic social networks. Part I. Annual Reviews in Control, 43, 65–79.

- Proskurnikov, A. V., & Tempo, R. (2018). A tutorial on modeling and analysis of dynamic social networks. Part II. Annual Reviews in Control.

- Rossi, W. S., Polderman, J. W., & Frasca, P. (2021). The closed loop between opinion formation and personalised recommendations. IEEE Transactions on Control of Network Systems, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Santos, F. P., Lelkes, Y., & Levin, S. A. (2021). Link recommendation algorithms and dynamics of polarization in online social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(50). [CrossRef]

- Schelling, T. C. (1969). Models of segregation. The American Economic Review, 59(2), 488–493.

- Vazquez, F. (2022). Modeling and Analysis of Social Phenomena: Challenges and Possible Research Directions. Entropy, 24(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Weng, L., Flammini, A., Vespignani, A., & Menczer, F. (2012). Competition among memes in a world with limited attention. Scientific Reports, 2, 335.

- Zafeiris, A. (2022). Opinion Polarization in Human Communities Can Emerge as a Natural Consequence of Beliefs Being Interrelated. Entropy, 24(9), Article 9. [CrossRef]

Notes

| 1 |

The term “ranking algorithm” stands rather for content ordering. In turn, recommendation algorithms, as it follows from the name,

suggest something to a user (for example, new information sources that could be appreciated by the user or potential friends).

However, content ordering can be also understood as a sort of recommendation as it implicitly assumes that contents that have more priority are recommended by the platform. In this regard, in some situations where it is possible, we will use the terms “ranking

algorithm” and “recommendation algorithm” interchangeably. |

| 2 |

We do not use dislikes in our model. In fact, many online platforms ignore this sort of reaction. However, this modification seems

to be a natural update of the model. |

| 3 |

In fact, this quantity just compares how many neutrals were convinced by rightists against those that were persuaded by leftists. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).