2.2. Develop a semi-structured complex numbers equation generator

With the representation of semi-structured complex numbers given in Equation (4) it is now simple to generate arithmetic equations that can be used to evaluate the efficiency of a calculator. Hence, an equation generator was developed to create equations to be evaluated by both a standard and a division by zero calculator. The equations produced are random but valid infix equations consisting of operators () and semi-structured complex number operands that have the form . Collectively, these operators and operands are called tokens. The rules for generating a random arithmetic equation are simple:

- i.

Generate a random odd number greater than or equal to three. The random odd number indicates the number of tokens (arithmetic operators and operands) that the equation would have. The number of tokens must be a minimum of three tokens, that is, an operand followed by an operator followed by another operand. Every valid equation greater than three tokens in length will have an odd number of tokens.

- ii.

Every equation must start and end with an operand.

- iii.

Operators were always in even positions within the infix expression and operands always in odd positions.

- iv.

For the sake of simplicity brackets were not produced in the infix expressions, instead the precedence of operators indicated the order in which operators were to be evaluated.

With these rules, the algorithm for the semi-structured complex numbers equation generator is given in

Table 5. From

Table 5 the variables, (minimum operand value, maximum operand value) in line 1 of the algorithm represented the range of numbers used in the semi-structured complex triple

. Each component of the triple will have an integer value that falls within the range (minimum operand value, maximum operand value). This gives the user control of the values in the semi-structured complex number triples. Additionally, equation length (L) represented the length of the equation to be generated. This number must always be odd.

Examples of the sort of equations generated by the algorithm shown in

Table 5 are given in

Table 6.

All the equations shown in

Table 6 are valid infix expressions containing semi-structured complex number operands. These equations are evaluated according to the normal rules of semi-structured complex number arithmetic given in paper [

2].

2.4. Developing an Arithmetic Machine for a standard and a division by zero calculator

Two “Arithmetic Machines” were developed for this research. The first was an arithmetic machine for the standard calculator “Arithmetic Machine STD” and the second was an arithmetic machine for the division by zero calculator “Arithmetic Machine DBZ”.

A standard arithmetic calculator has only 4 basic operations addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Modern calculators will show an error message when division by zero is performed. In which case the user of the calculator must reset the calculator before the calculator can be used to perform another arithmetic operation.

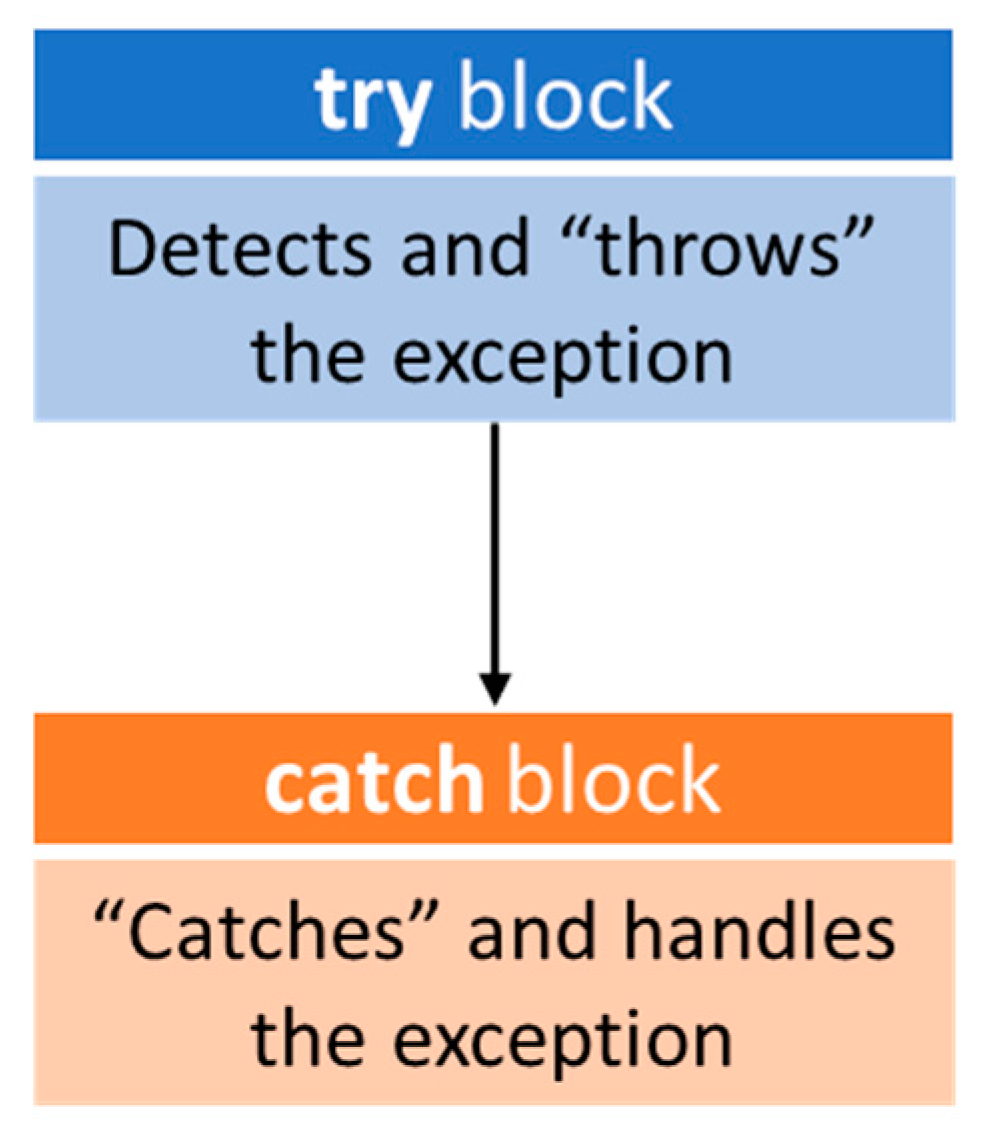

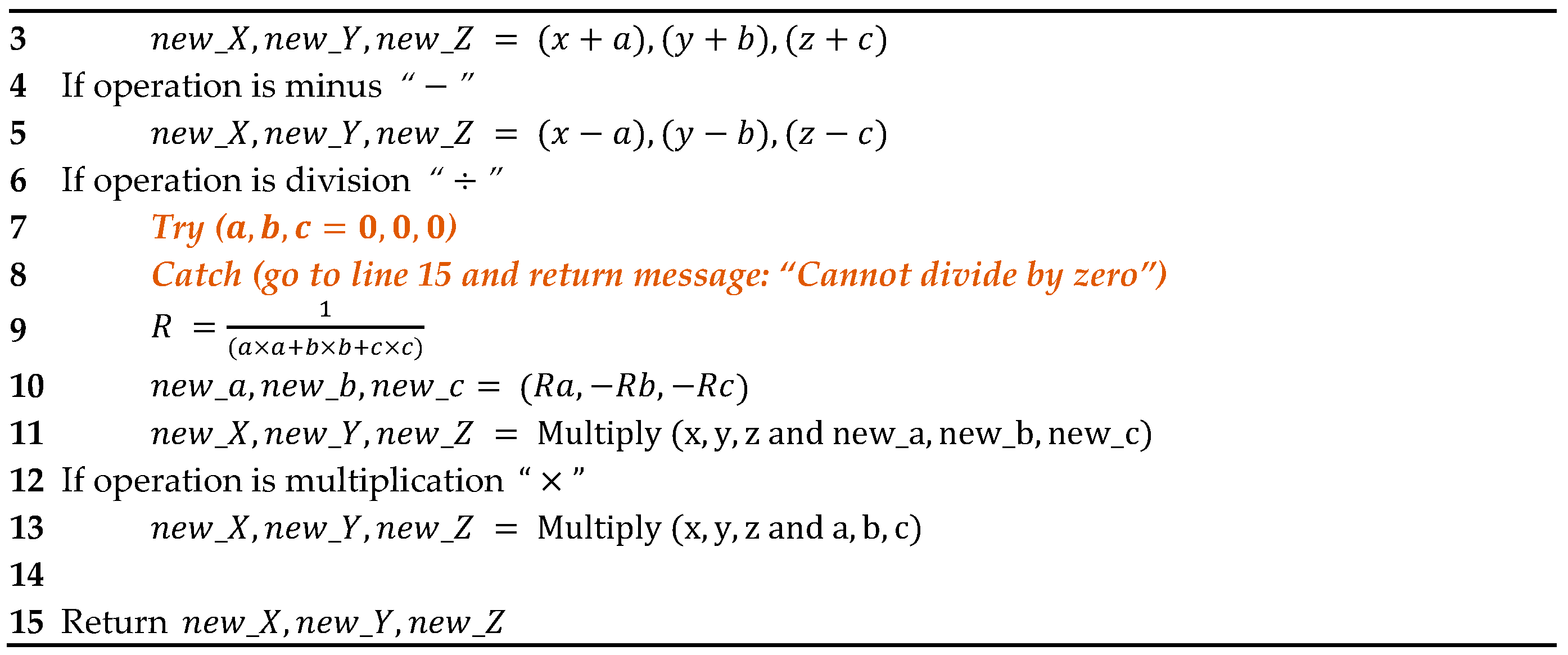

In the standard calculator developed for this paper when the calculator faces a division by zero operation it will output an error and the calculator will use a try-catch statement to deal with the division by zero error. The try catch statement will show an error message and reset the calculator for the next equation to be processed. This operation is part of the “Arithmetic Machine STD” given in

Table 7 for the standard calculator. The “Arithmetic Machine STD” given in

Table 7 takes two semi-structured complex numbers

and

and performs one of the simple arithmetic operations on these numbers.

In the algorithm shown in

Table 7, the try catch statement for division by zero is given in lines 7 to line 8. If the second operand is not zero, then the try catch statement is not executed and the algorithm continues to line 9. The algorithm also has a “Multiply” function in line 11 and line 13. This function is given in

Table 16 in Appendix 2. This “Multiply” function multiplies two semi-structed complex numbers according to the normal rules of multiplication for semi-structured complex numbers given in paper [

2].

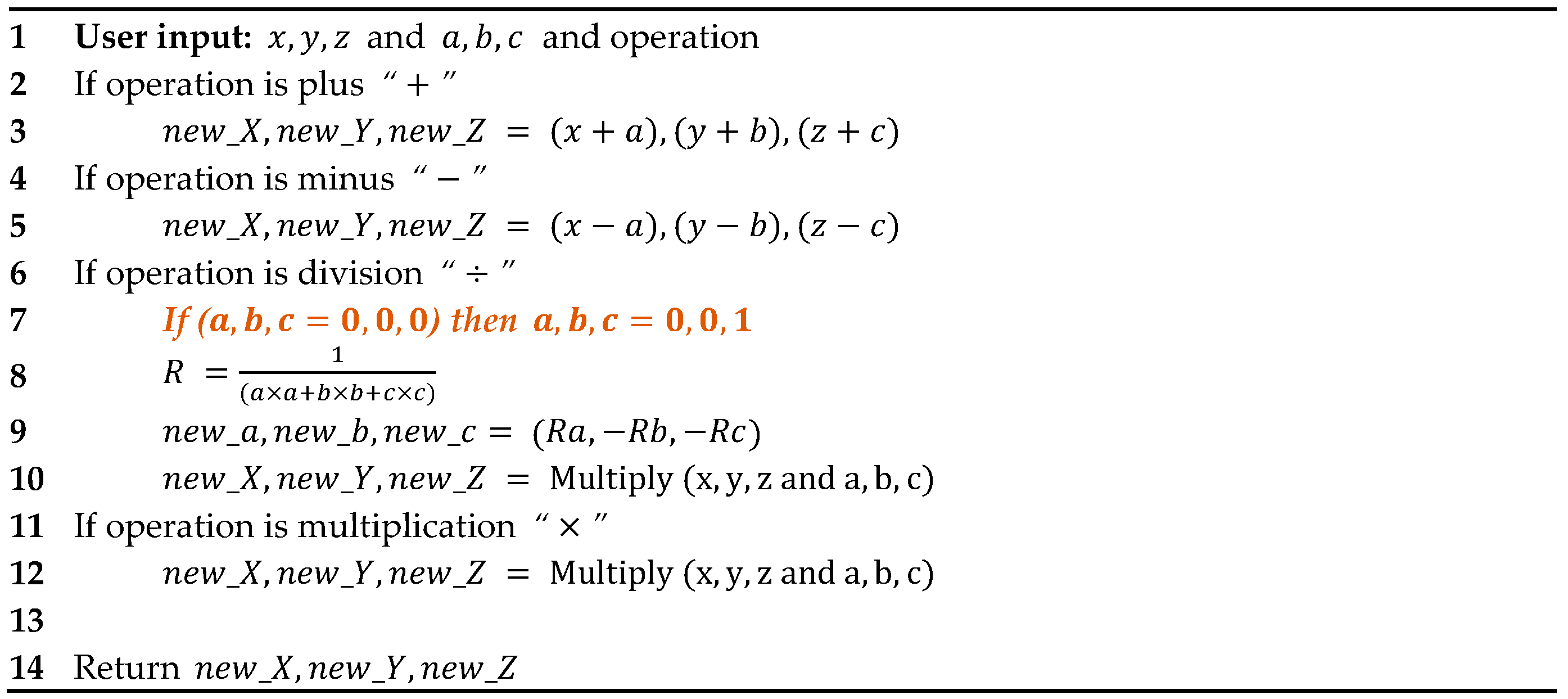

The “Arithmetic Machine DBZ” algorithm for the division by zero calculator was similar to the algorithm shown in

Table 7. However, the “Arithmetic Machine DBZ" handles division by zero differently as shown in

Table 8.

In the algorithm shown in

Table 8, if the second operand is zero, then the algorithm simply changes the second operand (line 7) to the unstructured unit value

(represented as the triple 0,0,1 in semi-structured complex number format shown in Equation (4)) where

. The algorithm then goes on to use the “Multiply” function in line 10. This function is given in

Table 16 in Appendix 2.

The final general algorithm for both the standard calculator and the division by zero calculator is given in

Table 9.

All the algorithms discussed thus far was developed and executed on an online Python platform [

8]. The speed of the platform was largely dependent on the speed of the servers on which the platform was ran. Since both calculators was ran from this platform, it provided a uniform starting point to evaluate their efficiency.

2.5. Simulation procedure to compare standard and division by zero calculator

To determine the efficiency of the standard calculator and the division by zero calculator, the space and time complexity of both calculators were compared. The measures for space and time complexity are given in

Table 10.

To begin, the space complexity for the standard calculator was first examined. This was done by examining the processing and output memory involved in running the standard calculator. The standard calculator was put through 20 simulations.

For the first simulation, 1000 equations were randomly generated (equation generator is given in

Table 5) with each equation having a length (L) of 5 tokens. The 5 tokens consisted of 2 operators chosen at random from the group

and Three operands in the form

with each component of the operand being integers generated within the range

to

. The range was kept small to increase the probability that there was division by zero operations within the set of 1000 equations.

The average number of operations per equations was found using the equation , where L is the length of the equation (number of tokens). This value was recorded as the variable “No. of operations per equation”.

In the process of generating the equations the number of equations with division by zero was calculated and recorded as the variable “No. of Equations with division by zero operations”. This was calculated by parsing each equation to determine if it had the subsequence “/ 0,0,0”. If the subsequence existed, then the equation was recorded as having a division by zero operation.

Additionally, the number of division by zero operations that exist across all 1000 equations was calculated and recorded in the variable “Total no. of division by zero operations”. The “No. of operations per equation”, “No. of Equations with division by zero operations” and “Total no. of division by zero operations” represent the characteristics of the equations that was processed by the standard calculator.

The 1000 equations were fed into the standard calculator algorithm (shown in

Table 9 with the user input for type of “Arithmetic machine” set to 1), and the total memory used to process all the equations was calculated and recorded. This was done using the Python functions tracemalloc.start() and tracemalloc.stop(). The result was recorded in the variable “

Total Processing Memory”. The total number of equations successfully calculated (that is equations that did not throw any exception errors) was recorded in the variable “

No. of equations successfully computed”.

The average processing memory per operation was calculated then recorded. This was done using the following formula given in Equation (5). This value was recorded as “

Average Processing Memory Per operation”.

In cases where an equation had division by zero in the standard calculator, the calculator did not compute a result but threw an exception and an error message was displayed and recorded as output.

After calculating the result of each equation, the output of the results of all 1000 equations were recorded in a text file. The total output memory (the size of the text file in bytes) was then recorded.

Once the space complexity of the standard calculator was examined the time complexity for the calculator was also examined. The total time taken to process all 1000 equations for the first simulation was calculated using the Python functions time.start() and time.stop(). The function time.start() was placed at the beginning of the standard calculator function to start measuring processing time and time.stop() was placed at the end of the standard calculator function to end the measurement. The time taken to process one equation was given by Equation (6).

The total time taken to process all 1000 equations was recorded as “

Total Processing Time”. The number of operations successfully computed by the standard calculator per unit time was calculated using Equation (7).

The result was recorded as “No. of operations per unit time”.

Once the space and time complexity for the standard calculator for the first simulation was determined, the process of calculating the characteristics of the equations, the space complexity and the time complexity of the standard calculator was repeated for 19 more simulations. For each simulation the length (L) of the equations was increased by 10 tokens from the previous simulation. The results were then tabulated.

The entire process of calculating the characteristics of the equations, the space and time complexity for 20 simulations of 1000 equations was repeated for the division by zero calculator. The results were then tabulated.

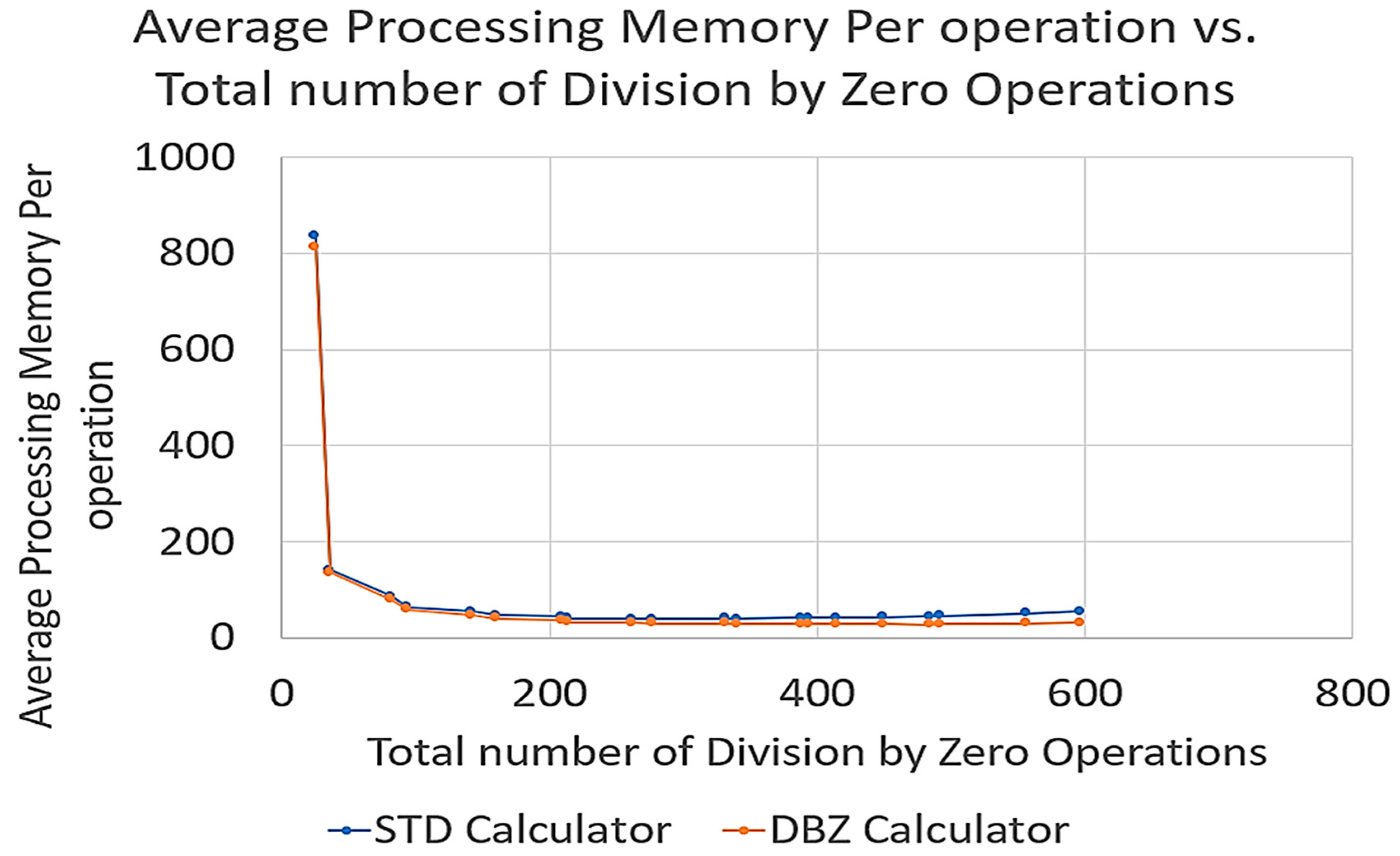

After the results were tabulated for the standard calculator and the division by zero calculator, three graphs were drawn. The first graph was a graph of “Average processing Memory per operation vs. Number of division by zero operations”. This graph was meant to determine how processing memory was affected by the presence of division by zero operation.

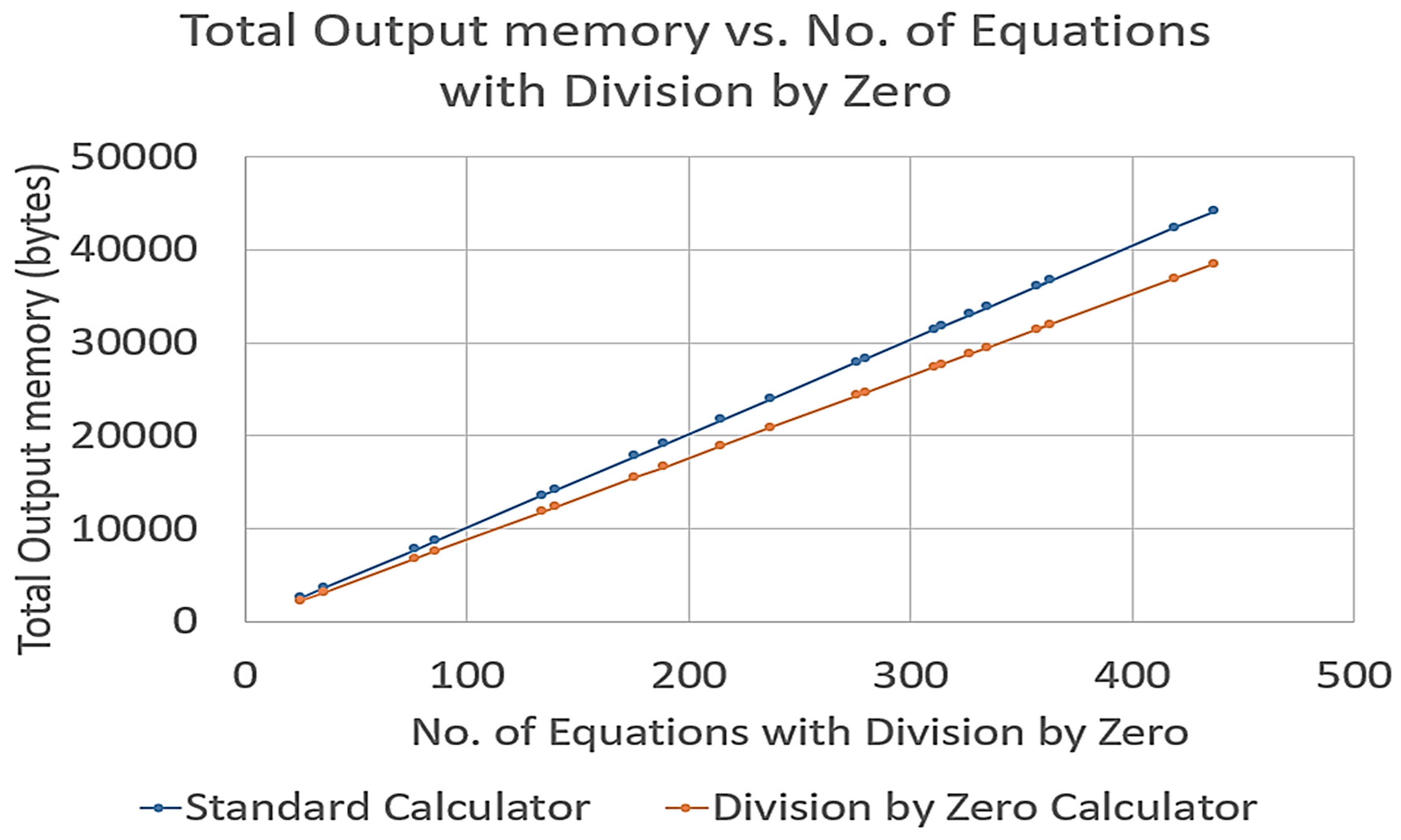

The second graph was a graph of “Total Output memory vs. Number of equations with division by zero”. This graph was meant to determine how the two calculators handle division by zero affected the amount of memory needed to output the results.

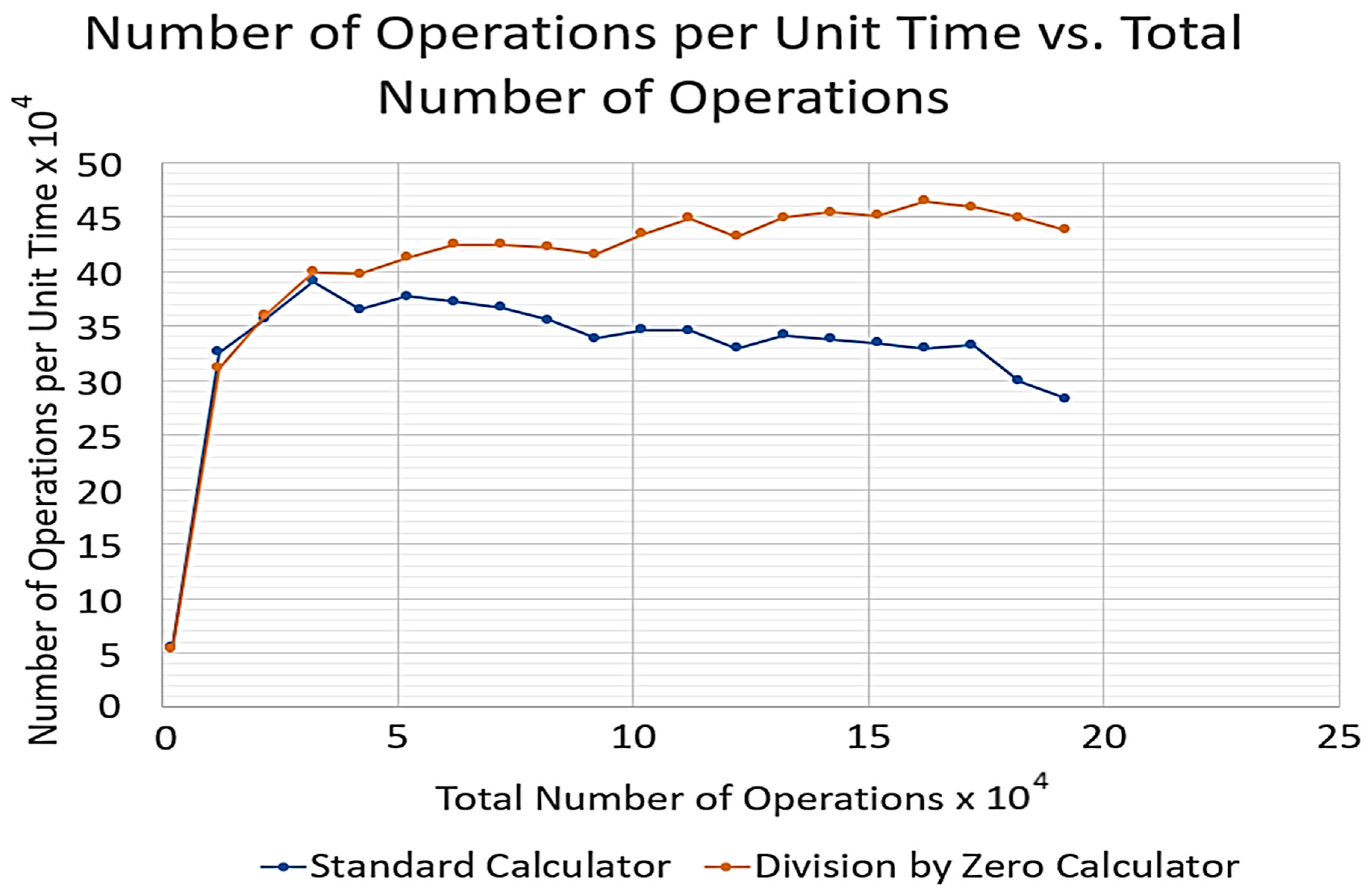

Finally, a graph of “Number of operations per unit time vs. Total number of operations” was plotted. The first two graphs provide a deeper look at the space complexity of the two calculators, whilst the final graph provides a closer look at the time complexity of the calculators.