Submitted:

29 March 2023

Posted:

31 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Lysosomal Storage Diseases

3. Mucopolysaccharidoses

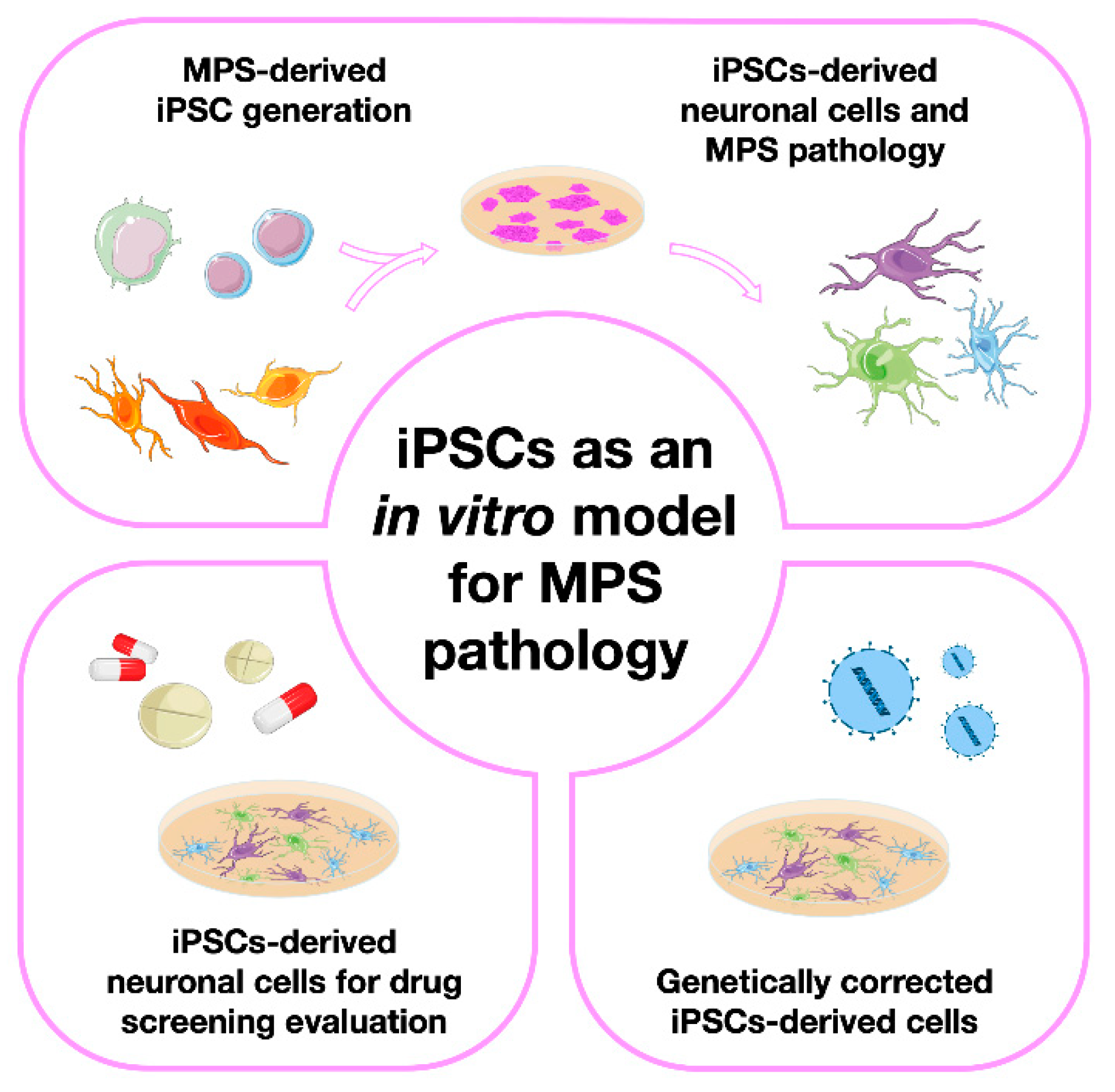

4. Modeling Mucopolysaccharidoses with induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)

4.1. The basic studies: iPSC generation from different MPS patient-derived cell sources

4.2. Moving one step further: generation of neuronal models from MPS-derived iPSCs

4.3. iPSCs-derived neuronal cells for drug screening/ therapies evaluation

4.4. Genetically corrected MPSs-derived iPSCs

5. An alternative approach to model Mucopolysaccharidoses

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scerra, G.; De Pasquale, V.; Scarcella, M.; Caporaso, M.G.; Pavone, L.M.; D’Agostino, M. Lysosomal Positioning Diseases: Beyond Substrate Storage. Open Biol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, A.F.; Benincore-Flórez, E.; Rintz, E.; Herreño-Pachón, A.M.; Celik, B.; Ago, Y.; Alméciga-Díaz, C.J.; Tomatsu, S. Mucopolysaccharidoses: Cellular Consequences of Glycosaminoglycans Accumulation and Potential Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, O.; Thompson, H.P.; Goodman, G.W.; Li, J.; Urayama, A. Mucopolysaccharidoses and the Blood–Brain Barrier. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, B.A.; Wrocklage, C.; Hasilik, A.; Saftig, P. The Proteome of Lysosomes. Proteomics 2010, 10, 4053–4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuscript, A. Lübke et Al., 2008 Lysosome.Pdf. 2010, 1793, 625–635.

- Platt, F.M. Emptying the Stores: Lysosomal Diseases and Therapeutic Strategies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Cognata, V.; Guarnaccia, M.; Polizzi, A.; Ruggieri, M.; Cavallaro, S. Highlights on Genomics Applications for Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Cells 2020, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenti, G.; Medina, D.L.; Ballabio, A. The Rapidly Evolving View of Lysosomal Storage Diseases. EMBO Mol. Med. 2021, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenti, G.; Andria, G.; Ballabio, A. Lysosomal Storage Diseases: From Pathophysiology to Therapy. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015, 66, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, F.M.; d’Azzo, A.; Davidson, B.L.; Neufeld, E.F.; Tifft, C.J. Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, V.; Dumpa, V. Lysosomal Storage Disease. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563270/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Boustany, R.M.N. Lysosomal Storage Diseases - The Horizon Expands. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 9, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleppin, S. Enzyme Replacement Therapy for Lysosomal Storage Diseases. J. Infus. Nurs. 2020, 43, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y. Chaperone Therapy for Molecular Pathology in Lysosomal Diseases. Brain Dev. 2021, 43, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desnick, R.J.; Schuchman, E.H. Enzyme Replacement Therapy for Lysosomal Diseases: Lessons from 20 Years of Experience and Remaining Challenges; 2012; Vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler, E. Enzyme Replacement in Gaucher Disease. PLoS Med. 2004, 1, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, L.; Huo, M.; Li, Q. Fabry Disease: Mechanism and Therapeutics Strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastores, G.M.; Hughes, D.A. Lysosomal Acid Lipase Deficiency: Therapeutic Options. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2020, 14, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.; Morrill, A.M.; Conway-Allen, S.L.; Kim, B. Review of Cerliponase Alfa: Recombinant Human Enzyme Replacement Therapy for Late-Infantile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis Type 2. J. Child Neurol. 2020, 35, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, G.A.; Jones, S.A.; Scarpa, M.; Mengel, K.E.; Giugliani, R.; Guffon, N.; Batsu, I.; Fraser, P.A.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. One-Year Results of a Clinical Trial of Olipudase Alfa Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Pediatric Patients with Acid Sphingomyelinase Deficiency. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarini, M.R.; Codini, M.; Conte, C.; Patria, F.; Cataldi, S.; Bertelli, M.; Albi, E.; Beccari, T. Alpha-Mannosidosis: Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monica, P.-P.; David R, B.; Paul, H. Current and New Therapies for Mucopolysaccharidoses. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kido, J.; Sugawara, K.; Nakamura, K.; Tomanin, R.; Azzo, A.D. Gene Therapy for Lysosomal Storage Diseases : Current Clinical Trial Prospects. 2023, 1–16.

- Li, M. Enzyme Replacement Therapy: A Review and Its Role in Treating Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Pediatr. Ann. 2018, 47, e191–e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga, F.; Ramírez, P.; Wietstruck, A.; Rojas, N. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Clinical Use and Perspectives. Biol. Res. 2012, 45, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffi, A. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Gene Therapy for Storage Disease: Current and New Indications. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffi, A.; Montini, E.; Lorioli, L.; Cesani, M.; Fumagalli, F.; Plati, T.; Baldoli, C.; Martino, S.; Calabria, A.; Canale, S.; et al. Lentiviral Hematopoietic Stem Cell Gene Therapy Benefits Metachromatic Leukodystrophy. Science (80-. ). 2013, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessa, M.; Lorioli, L.; Fumagalli, F.; Acquati, S.; Redaelli, D.; Baldoli, C.; Canale, S.; Lopez, I.D.; Morena, F.; Calabria, A.; et al. Lentiviral Haemopoietic Stem-Cell Gene Therapy in Early-Onset Metachromatic Leukodystrophy: An Ad-Hoc Analysis of a Non-Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 1/2 Trial. Lancet 2016, 388, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartier, N.; Hacein-Bey-Abina, S.; Bartholomae, C.C.; Veres, G.; Schmidt, M.; Kutschera, I.; Vidaud, M.; Abel, U.; Dal-Cortivo, L.; Caccavelli, L.; et al. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Gene Therapy with a Lentiviral Vector in X-Linked Adrenoleukodystrophy. Science (80-. ). 2009, 326, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagree, M.S.; Felizardo, T.C.; Faber, M.L.; Rybova, J.; Rupar, C.A.; Foley, S.R.; Fuller, M.; Fowler, D.H.; Medin, J.A. Autologous, Lentivirus-modified, T-rapa Cell “Micropharmacies” for Lysosomal Storage Disorders. EMBO Mol. Med. 2022, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccardi, R.; Gualandi, F. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Procedures. Autoimmunity 2008, 41, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, J.J.; Prasad, V.K.; Tolar, J.; Wynn, R.F.; Peters, C. Current International Perspectives on Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Inherited Metabolic Disorders. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2010, 57, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatack, J.J.; Consolini, D.M.; Bayever, E. The Status of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Lysosomal Storage Disease. Pediatr. Neurol. 2003, 29, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, M.F.; Santos, J.I.; Alves, S. Less Is More: Substrate Reduction Therapy for Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.E.; Hipp, M.S.; Bracher, A.; Hayer-Hartl, M.; Ulrich Hartl, F. Molecular Chaperone Functions in Protein Folding and Proteostasis; 2013; Vol. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.Q.; Ishii, S.; Asano, N.; Suzuki, Y. Accelerated Transport and Maturation of Lysosomal α-Galactosidase A in Fabry Lymphoblasts by an Enzyme Inhibitor. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.A.; Nicholls, K.; Shankar, S.P.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Koeller, D.; Nedd, K.; Vockley, G.; Hamazaki, T.; Lachmann, R.; Ohashi, T.; et al. Oral Pharmacological Chaperone Migalastat Compared with Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Fabry Disease: 18-Month Results from the Randomised Phase III ATTRACT Study. J. Med. Genet. 2017, 54, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F.; Martínez-Bailén, M.; Matassini, C.; Morrone, A.; Falliano, S.; Caciotti, A.; Paoli, P.; Goti, A.; Cardona, F. Synthesis of a New β-Galactosidase Inhibitor Displaying Pharmacological Chaperone Properties for GM1 Gangliosidosis. Molecules 2022, 27, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stütz, A.E.; Thonhofer, M.; Weber, P.; Wolfsgruber, A.; Wrodnigg, T.M. Pharmacological Chaperones for β-Galactosidase Related to GM1-Gangliosidosis and Morquio B: Recent Advances. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 2980–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuhisa, K.; Imaizumi, K. Loss of Function of Mutant Ids Due to Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Degradation: New Therapeutic Opportunities for Mucopolysaccharidosis Type Ii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Taherzadeh, M.; Bose, P.; Heon-Roberts, R.; Nguyen, A.L.A.; Xu, T.; Pará, C.; Yamanaka, Y.; Priestman, D.A.; Platt, F.M.; et al. Glucosamine Amends CNS Pathology in Mucopolysaccharidosis IIIC Mouse Expressing Misfolded HGSNAT. J. Exp. Med. 2022, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cuesta, M.; Herrera-González, I.; García-Moreno, M.I.; Ashmus, R.A.; Vocadlo, D.J.; García Fernández, J.M.; Nanba, E.; Higaki, K.; Ortiz Mellet, C. Sp2-Iminosugars Targeting Human Lysosomal β-Hexosaminidase as Pharmacological Chaperone Candidates for Late-Onset Tay-Sachs Disease. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2022, 37, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ponti, G.; Donsante, S.; Frigeni, M.; Pievani, A.; Corsi, A.; Bernardo, M.E.; Riminucci, M.; Serafini, M. MPSI Manifestations and Treatment Outcome: Skeletal Focus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorne A Clarke, M. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1162/.

- Lin, H.Y.; Lin, S.P.; Chuang, C.K.; Niu, D.M.; Chen, M.R.; Tsai, F.J.; Chao, M.C.; Chiu, P.C.; Lin, S.J.; Tsai, L.P.; et al. Incidence of the Mucopolysaccharidoses in Taiwan, 1984-2004. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2009, 149, 960–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moammar, H.; Cheriyan, G.; Mathew, R.; Al-Sannaa, N. Incidence and Patterns of Inborn Errors of Metabolism in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, 1983-2008. Ann. Saudi Med. 2010, 30, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, B.; Tomatsu, S.C.; Tomatsu, S.; Khan, S.A. Epidemiology of Mucopolysaccharidoses Update. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampe, C.S.; Eisengart, J.B.; Lund, T.C.; Orchard, P.J.; Swietlicka, M.; Wesley, J.; McIvor, R.S. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I: A Review of the Natural History and Molecular Pathology. Cells 2020, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medline Plus Mucopolysacchaidosis Type I. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/mucopolysaccharidosis-type-i/.

- HGMD. Available online: https://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php.

- Carbajal-Rodríguez, L.M.; Pérez-García, M.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Rosales, H.S.; Olaya-Vargas, A. Long-Term Evolution of Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I in Twins Treated with Enzyme Replacement Therapy plus Hematopoietic Stem Cells Transplantation. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giugliani, R.; Muschol, N.; Keenan, H.A.; Dant, M.; Muenzer, J. Improvement in Time to Treatment, but Not Time to Diagnosis, in Patients with Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIH; GARD Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I. Available online: https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/10335/mucopolysaccharidosis-type-i.

- Williams, I.M.; Pineda, R.; Neerukonda, V.K.; Stagner, A.M. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I–Associated Corneal Disease: A Clinicopathologic Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 231, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applegarth, D.A.; Toone, J.R.; Brian Lowry, R. Incidence of Inborn Errors of Metabolism in British Columbia, 1969-1996. Pediatrics 2000, 105, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krabbi, K.; Joost, K.; Zordania, R.; Talvik, I.; Rein, R.; Huijmans, J.G.M.; Verheijen, F. V.; Õunap, K. The Live-Birth Prevalence of Mucopolysaccharidoses in Estonia. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 2012, 16, 846–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NORD Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II. Available online: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/mucopolysaccharidosis-type-ii-2/.

- Mohamed, S.; He, Q.Q.; Singh, A.A.; Ferro, V. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II (Hunter Syndrome): Clinical and Biochemical Aspects of the Disease and Approaches to Its Diagnosis and Treatment. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 2020, 77, 71–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, P.J.; Meaney, C.A.; Hopwood, J.J.; Morris, C.P. Sequence of the Human Iduronate 2-Sulfatase (IDS) Gene. Genomics 1993, 17, 773–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Pantoom, S.; Petters, J.; Pandey, A.K.; Hermann, A.; Lukas, J. A Molecular Genetics View on Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II. Mutat. Res. - Rev. Mutat. Res. 2021, 788, 108392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lu, C.; Ding, Y.; Meng, Y. Update of Treatment for Mucopolysaccharidosis Type III (Sanfilippo Syndrome). Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valstar, M.J.; Ruijter, G.J.G.; van Diggelen, O.P.; Poorthuis, B.J.; Wijburg, F.A. Sanfilippo Syndrome: A Mini-Review. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2008, 31, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodamer, O.A.; Giugliani, R.; Wood, T. The Laboratory Diagnosis of Mucopolysaccharidosis III (Sanfilippo Syndrome): A Changing Landscape. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2014, 113, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josahkian, J.A.; Trapp, F.B.; Burin, M.G.; Michelin-Tirelli, K.; de Magalhães, A.P.P.S.; Sebastião, F.M.; Bender, F.; De Mari, J.F.; Brusius-Facchin, A.C.; Leistner-Segal, S.; et al. Updated Birth Prevalence and Relative Frequency of Mucopolysaccharidoses across Brazilian Regions. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2021, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorthuis, B.J.H.M.; Wevers, R.A.; Kleijer, W.J.; Groener, J.E.M.; de Jong, J.G.N.; van Weely, S.; Niezen-Koning, K.E.; van Diggelen, O.P. The Frequency of Lysosomal Storage Diseases in The Netherlands. Hum. Genet. 1999, 105, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medline Plus Mucopolysaccharidosis Type III. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/mucopolysaccharidosis-type-iii/.

- Benetó, N.; Vilageliu, L.; Grinberg, D.; Canals, I. Sanfilippo Syndrome: Molecular Basis, Disease Models and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NORD Mucopolysaccharidosis Type III. Available online: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/mucopolysaccharidosis-type-iii/.

- Köhn, A.F.; Grigull, L.; du Moulin, M.; Kabisch, S.; Ammer, L.; Rudolph, C.; Muschol, N.M. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IIIA: A Case Description and Comparison with a Genotype-Matched Control Group. Mol. Genet. Metab. Reports 2020, 23, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogerbrugge, P.M.; Brouwer, O.F.; Bordigoni, P.; Cornu, G.; Kapaun, P.; Ortega, J.J.; O’Meara, A.; Souillet, G.; Frappaz, D.; Blanche, S.; et al. Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplantation for Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Lancet 1995, 345, 1398–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, E.G.; Lockman, L.A.; Balthazor, M.; Krivit, W. Neuropsychological Outcomes of Several Storage Diseases with and without Bone Marrow Transplantation. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1995, 18, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivakumur, P.; Wraith, J.E. Bone Marrow Transplantation in Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IIIA: A Comparison of an Early Treated Patient with His Untreated Sibling. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1999, 22, 849–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Okuyama, T. Novel Enzyme Replacement Therapies for Neuropathic Mucopolysaccharidoses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, H.; Chidlow, G.; Neumann, D.; Nazri, N.; Douglass, M.; Trim, P.J.; Snel, M.F.; Casson, R.J.; Hemsley, K.M. Is the Eye a Window to the Brain in Sanfilippo Syndrome? Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belur, L.R.; Romero, M.; Lee, J.; Podetz-Pedersen, K.M.; Nan, Z.; Riedl, M.S.; Vulchanova, L.; Kitto, K.F.; Fairbanks, C.A.; Kozarsky, K.F.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Intracerebroventricular, Intrathecal, and Intranasal Routes of AAV9 Vector Administration for Genetic Therapy of Neurologic Disease in Murine Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, A.; Crippen-Harmon, D.; Nave, L.; Vincelette, J.; Wait, J.C.M.; Melton, A.C.; Lawrence, R.; Brown, J.R.; Webster, K.A.; Yip, B.K.; et al. Translational Studies of Intravenous and Intracerebroventricular Routes of Administration for CNS Cellular Biodistribution for BMN 250, an Enzyme Replacement Therapy for the Treatment of Sanfilippo Type B. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2020, 10, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.L.; Ashmead, R.E.; Choy, F.Y.M. Cell and Gene Therapies for Mucopolysaccharidoses: Base Editing and Therapeutic Delivery to the CNS. Diseases 2019, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safary, A.; Akbarzadeh Khiavi, M.; Omidi, Y.; Rafi, M.A. Targeted Enzyme Delivery Systems in Lysosomal Disorders: An Innovative Form of Therapy for Mucopolysaccharidosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 3363–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, O.; Thompson, H.P.; Goodman, G.W.; Li, J.; Urayama, A. Mucopolysaccharidoses and the Blood-Brain Barrier. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tordo, J.; O’Leary, C.; Antunes, A.S.L.M.; Palomar, N.; Aldrin-Kirk, P.; Basche, M.; Bennett, A.; D’Souza, Z.; Gleitz, H.; Godwin, A.; et al. A Novel Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid with Enhanced Neurotropism Corrects a Lysosomal Transmembrane Enzyme Deficiency. Brain 2018, 141, 2014–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcó, S.; Haurigot, V.; Bosch, F. In Vivo Gene Therapy for Mucopolysaccharidosis Type III (Sanfilippo Syndrome): A New Treatment Horizon. Hum. Gene Ther. 2019, 30, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, A.L.; O’Leary, C.; Liao, A.; Agúndez, L.; Youshani, A.S.; Gleitz, H.F.; Parker, H.; Taylor, J.T.; Danos, O.; Hocquemiller, M.; et al. An Improved Adeno-Associated Virus Vector for Neurological Correction of the Mouse Model of Mucopolysaccharidosis IIIA. Hum. Gene Ther. 2019, 30, 1052–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, V.; Sarogni, P.; Pistorio, V.; Cerulo, G.; Paladino, S.; Pavone, L.M. Targeting Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Mucopolysaccharidoses. Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev. 2018, 10, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, H.; Park, C.; Maeng, S. Mucopolysaccharidoses I and II: Brief Review of Therapeutic Options and Supportive/Palliative Therapies. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, M.; Santos, J.; Matos, L.; Alves, S. Genetic Substrate Reduction Therapy: A Promising Approach for Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Diseases 2016, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, F.; Aldámiz-Echevarría, L.; Llarena, M.; Couce, M.L. Sanfilippo Syndrome: Overall Review. Pediatr. Int. 2015, 57, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobkiewicz-banecka, J.; Gabig-ciminska, M.; Kloska, A.; Malinowska, M.; Piotrowska, E.; Banecka-majkutewicz, Z.; Banecki, B.; Wegrzyn, A. Glycosaminoglycans and Mucopolysaccharidosis Type III Table 1. Birth Prevalence of MPS III. 2016, 1393–1409. [Google Scholar]

- Malm, G.; Lund, A.M.; Månsson, J.E.; Heiberg, A. Mucopolysaccharidoses in the Scandinavian Countries: Incidence and Prevalence. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2008, 97, 1577–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Politei, J.; Schenone, A.B.; Guelbert, N.; Fainboim, A.; Szlago, M. Morquio Disease (Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IV-A): Clinical Aspects, Diagnosis and New Treatment with Enzyme Replacement Therapy. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2015, 113, 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriksz, C.J.; Berger, K.I.; Giugliani, R.; Harmatz, P.; Kampmann, C.; Mackenzie, W.G.; Raiman, J.; Villarreal, M.S.; Savarirayan, R. International Guidelines for the Management and Treatment of Morquio a Syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2015, 167, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Alméciga-Díaz, C.J.; Sawamoto, K.; Mackenzie, W.G.; Theroux, M.C.; Pizarro, C.; Mason, R.W.; Orii, T.; Tomatsu, S. Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA and Glycosaminoglycans. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 120, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NORD Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IV. Available online: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/morquio-syndrome/.

- Jurecka, A.; Ługowska, A.; Golda, A.; Czartoryska, B.; Tylki-Szymańska, A. Prevalence Rates of Mucopolysaccharidoses in Poland. J. Appl. Genet. 2015, 56, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NORD Maroteaux Lamy Syndrome. Available online: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/maroteaux-lamy-syndrome/.

- Vi, M. Disease Name with Synonyms. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tomanin, R.; Karageorgos, L.; Zanetti, A.; Al-Sayed, M.; Bailey, M.; Miller, N.; Sakuraba, H.; Hopwood, J.J. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type VI (MPS VI) and Molecular Analysis: Review and Classification of Published Variants in the ARSB Gene. Hum. Mutat. 2018, 39, 1788–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmatz, P.R.; Shediac, R. Mucopolysaccharidosis VI: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Front. Biosci. - Landmark 2017, 22, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poup, H.; Ledvinová, J.; Berná, L.; Dvo, L.; Ko, V.; Elleder, M. The Birth Prevalence of Lysosomal Storage Disorders in the Czech Republic : Comparison with Data in Different Populations. 2010, 387–396. [Google Scholar]

- Federhen, A.; Pasqualim, G.; de Freitas, T.F.; Gonzalez, E.A.; Trapp, F.; Matte, U.; Giugliani, R. Estimated Birth Prevalence of Mucopolysaccharidoses in Brazil. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2020, 182, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.A.; Peracha, H.; Ballhausen, D.; Wiesbauer, A.; Rohrbach, M.; Gautschi, M.; Mason, R.W.; Giugliani, R.; Suzuki, Y.; Orii, K.E.; et al. Epidemiology of Mucopolysaccharidoses. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 121, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaño, A.M.; Lock-Hock, N.; Steiner, R.D.; Graham, B.H.; Szlago, M.; Greenstein, R.; Pineda, M.; Gonzalez-Meneses, A.; çoker, M.; Bartholomew, D.; et al. Clinical Course of Sly Syndrome (Mucopolysaccharidosis Type VII). J. Med. Genet. 2016, 53, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medline Plus Mucopolysaccharidosis Type VII. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/mucopolysaccharidosis-type-vii/.

- Tomatsu, S.; Montano, A.M.; Dung, V.C.; Grubb, J.H.; Sly, W.S. Mutations and Polymorphisms in GUSB Gene in Mucopolysaccharidosis VII (Sly Syndrome). Hum. Mutat. 2009, 30, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NORD Mucopolysaccharidosis Type VII. Available online: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/sly-syndrome/.

- Of, A.; Report, C. Clinical and Biochemical Manifestations of Hyaluronidase Deficiency. New Engl. J. Med. Fig. 1996, 335, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Society, M. MPS IX. Available online: https://www.mpssociety.org.uk/mps-ix.

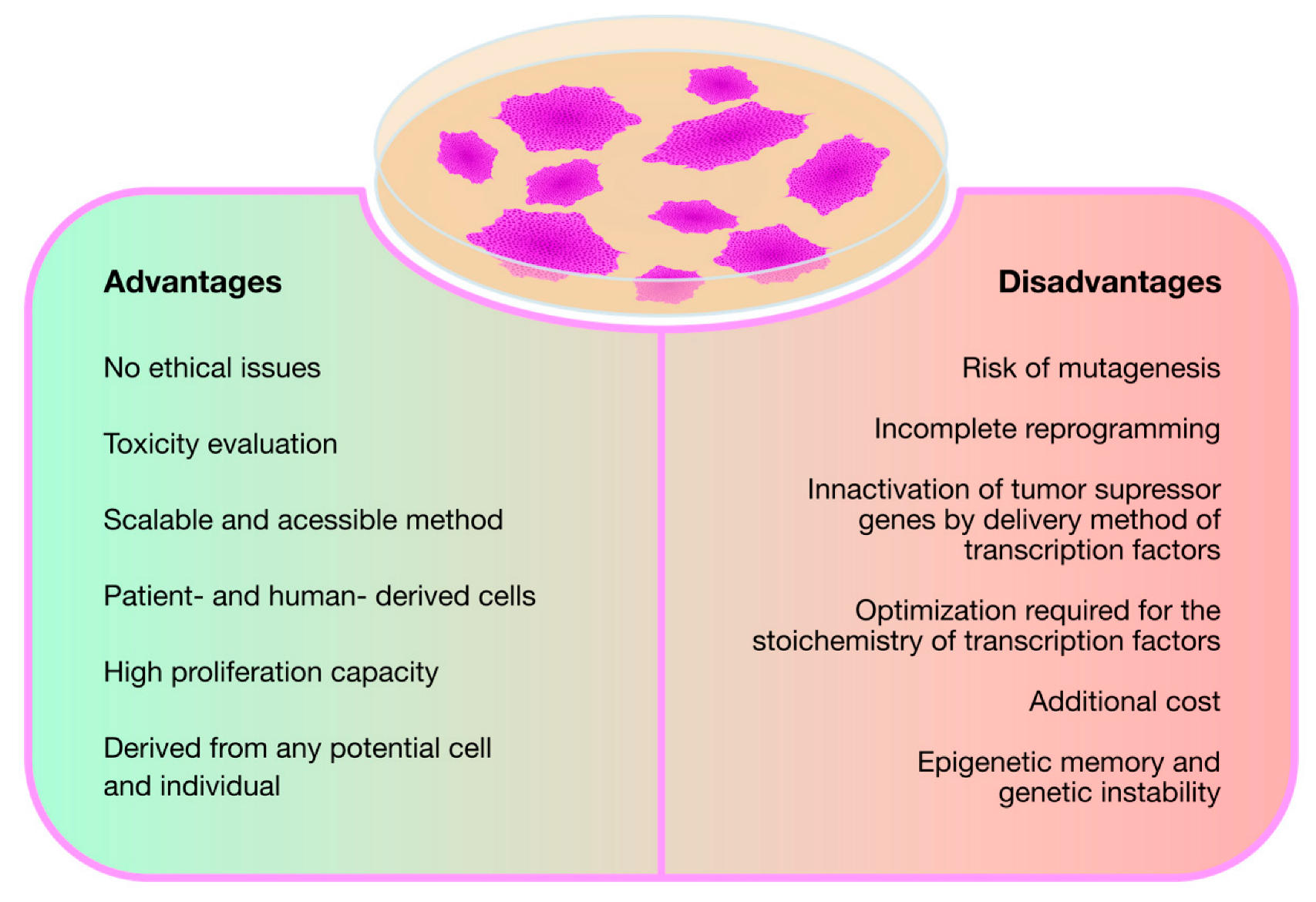

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.; Rao, M.S. A Review of the Methods for Human IPSC Derivation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 997, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier, T.; Blanchard, S.; Toli, D.; Roy, E.; Bigou, S.; Froissart, R.; Rouvet, I.; Vitry, S.; Heard, J.M.; Bohl, D. Modeling Neuronal Defects Associated with a Lysosomal Disorder Using Patient-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 3653–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo-Diez, S.; Fleischer, A.; Martín-Fernández, J.M.; Sánchez-Gilabert, A.; Bachiller, D. Generation of Two Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Lines from a Mucopolysaccharydosis IIIB (MPSIIIB) Patient. Stem Cell Res. 2018, 33, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, S.; Fleischer, A.; Martín, J.M.; Sánchez, A.; Palomino, E.; Bachiller, D. Generation of Two Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Lines from Mucopolysaccharydosis IIIA Patient: IMEDEAi004-A and IMEDEAi004-B. Stem Cell Res. 2018, 32, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Jehuda, R.; Shemer, Y.; Binah, O. Genome Editing in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Using CRISPR/Cas9. Stem Cell Rev. Reports 2018, 14, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetó, N.; Cozar, M.; García-Morant, M.; Creus-Bachiller, E.; Vilageliu, L.; Grinberg, D.; Canals, I. Generation of Two Compound Heterozygous HGSNAT-Mutated Lines from Healthy Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Using CRISPR/Cas9 to Model Sanfilippo C Syndrome. Stem Cell Res. 2019, 41, 101616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, E.; Nemes, C.; Bock, I.; Varga, N.; Fehér, A.; Dinnyés, A.; Kobolák, J. Generation of Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II (MPS II) Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (IPSC) Line from a 1-Year-Old Male with Pathogenic IDS Mutation. Stem Cell Res. 2016, 17, 482–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, E.; Nemes, C.; Bock, I.; Varga, N.; Fehér, A.; Kobolák, J.; Dinnyés, A. Generation of Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II (MPS II) Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (IPSC) Line from a 3-Year-Old Male with Pathogenic IDS Mutation. Stem Cell Res. 2016, 17, 479–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, E.; Nemes, C.; Bock, I.; Varga, N.; Fehér, A.; Kobolák, J.; Dinnyés, A. Generation of Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II (MPS II) Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (IPSC) Line from a 7-Year-Old Male with Pathogenic IDS Mutation. Stem Cell Res. 2016, 17, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, E.; Nemes, C.; Kovács, E.; Bock, I.; Varga, N.; Fehér, A.; Dinnyés, A.; Kobolák, J. Generation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (IPSC) Line from an Unaffected Female Carrier of Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II (MPS II) Disorder. Stem Cell Res. 2016, 17, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lito, S.; Burda, P.; Baumgartner, M.; Sloan-Béna, F.; Táncos, Z.; Kobolák, J.; Dinnyés, A.; Krause, K.H.; Marteyn, A. Generation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Line UNIGEi001-A from a 2-Years Old Patient with Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IH Disease. Stem Cell Res. 2019, 41, 101604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suga, M.; Kondo, T.; Imamura, K.; Shibukawa, R.; Okanishi, Y.; Sagara, Y.; Tsukita, K.; Enami, T.; Furujo, M.; Saijo, K.; et al. Generation of a Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Line, BRCi001-A, Derived from a Patient with Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I. Stem Cell Res. 2019, 36, 101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyère, J.; Roy, E.; Ausseil, J.; Lemonnier, T.; Teyre, G.; Bohl, D.; Etienne-Manneville, S.; Lortat-Jacob, H.; Heard, J.M.; Vitry, S. Heparan Sulfate Saccharides Modify Focal Adhesions: Implication in Mucopolysaccharidosis Neuropathophysiology. J. Mol. Biol. 2015, 427, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canals, I.; Soriano, J.; Orlandi, J.G.; Torrent, R.; Richaud-Patin, Y.; Jiménez-Delgado, S.; Merlin, S.; Follenzi, A.; Consiglio, A.; Vilageliu, L.; et al. Activity and High-Order Effective Connectivity Alterations in Sanfilippo C Patient-Specific Neuronal Networks. Stem Cell Reports 2015, 5, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetó, N.; Cozar, M.; Castilla-Vallmanya, L.; Zetterdahl, O.G.; Sacultanu, M.; Segur-Bailach, E.; García-Morant, M.; Ribes, A.; Ahlenius, H.; Grinberg, D.; et al. Neuronal and Astrocytic Differentiation from Sanfilippo C Syndrome IPSCs for Disease Modeling and Drug Development. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, R.J.; Jolly, L.A.; Johnson, B. V.; Lord, M.S.; Kim, H.N.; Saville, J.T.; Fuller, M.; Byers, S.; Derrick-Roberts, A.L.K. Impaired Neural Differentiation of MPS IIIA Patient Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Neural Progenitor Cells. Mol. Genet. Metab. Reports 2021, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobolák, J.; Molnár, K.; Varga, E.; Bock, I.; Jezsó, B.; Téglási, A.; Zhou, S.; Lo Giudice, M.; Hoogeveen-Westerveld, M.; Pijnappel, W.P.; et al. Modelling the Neuropathology of Lysosomal Storage Disorders through Disease-Specific Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2019, 380, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yick, L.W.; Ma, O.K.F.; Ng, R.C.L.; Kwan, J.S.C.; Chan, K.H. Aquaporin-4 Autoantibodies from Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder Patients Induce Complement-Independent Immunopathologies in Mice. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaroop, M.; Brooks, M.J.; Gieser, L.; Swaroop, A.; Zheng, W. Patient IPSC-Derived Neural Stem Cells Exhibit Phenotypes in Concordance with the Clinical Severity of Mucopolysaccharidosis I. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 3612–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lito, S.; Sidibe, A.; Ilmjarv, S.; Burda, P.; Baumgartner, M.; Wehrle-Haller, B.; Krause, K.H.; Marteyn, A. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Understand Mucopolysaccharidosis. I: Demonstration of a Migration Defect in Neural Precursors. Cells 2020, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canals, I.; Benetó, N.; Cozar, M.; Vilageliu, L.; Grinberg, D. EXTL2 and EXTL3 Inhibition with SiRNAs as a Promising Substrate Reduction Therapy for Sanfilippo C Syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Cheng, Y.S.; Yang, S.; Swaroop, M.; Xu, M.; Huang, W.; Zheng, W. Disease Modeling for Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IIIB Using Patient Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2021, 407, 112785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, T.; Contreras, P.; Castro, J.F.; Chamorro, D.; Balboa, E.; Bosch-Morató, M.; Muñoz, F.J.; Alvarez, A.R.; Zanlungo, S. Vitamin E Dietary Supplementation Improves Neurological Symptoms and Decreases C-Abl/P73 Activation in Niemann-Pick C Mice. Nutrients 2014, 6, 3000–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val, E. C ELL -B ASED D RUG D EVELOPMENT, S CREENING, AND T OXICOLOGY Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Reveal Functional Differences Between Drugs Currently Investigated in Patients With Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome. 2014, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.S.; Yang, S.; Hong, J.; Li, R.; Beers, J.; Zou, J.; Huang, W.; Zheng, W. Modeling Cns Involvement in Pompe Disease Using Neural Stem Cells Generated from Patient-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Cheng, Y.S.; Yang, S.; Swaroop, M.; Xu, M.; Beers, J.; Zou, J.; Huang, W.; Marugan, J.J.; Cai, X.; et al. IPS-Derived Neural Stem Cells for Disease Modeling and Evaluation of Therapeutics for Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II. Exp. Cell Res. 2022, 412, 113007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybová, J.; Ledvinová, J.; Sikora, J.; Kuchař, L.; Dobrovolný, R. Neural Cells Generated from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells as a Model of CNS Involvement in Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2018, 41, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, T.A.; Anderson, H.C.; Wolfe, J.H. Ex Vivo Gene Therapy Using Patient IPSC-Derived NSCs Reverses Pathology in the Brain of a Homologous Mouse Model. Stem Cell Reports 2015, 4, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, D.; Pearse, Y.; Kan, S. hsin; Le, S.Q.; Sanghez, V.; Cooper, J.D.; Dickson, P.I.; Iacovino, M. Genetically Corrected IPSC-Derived Neural Stem Cell Grafts Deliver Enzyme Replacement to Affect CNS Disease in Sanfilippo B Mice. Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev. 2018, 10, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearse, Y.; Clarke, D.; Kan, S.; Le, S.Q.; Sanghez, V.; Luzzi, A.; Pham, I.; Nih, L.R.; Cooper, J.D.; Dickson, P.I.; et al. Brain Transplantation of Genetically Corrected Sanfilippo Type B Neural Stem Cells Induces Partial Cross-Correction of the Disease. Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev. 2022, 27, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miki, T.; Vazquez, L.; Yanuaria, L.; Lopez, O.; Garcia, I.M.; Ohashi, K.; Rodriguez, N.S. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Derivation and Ex Vivo Gene Correction Using a Mucopolysaccharidosis Type 1 Disease Mouse Model. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

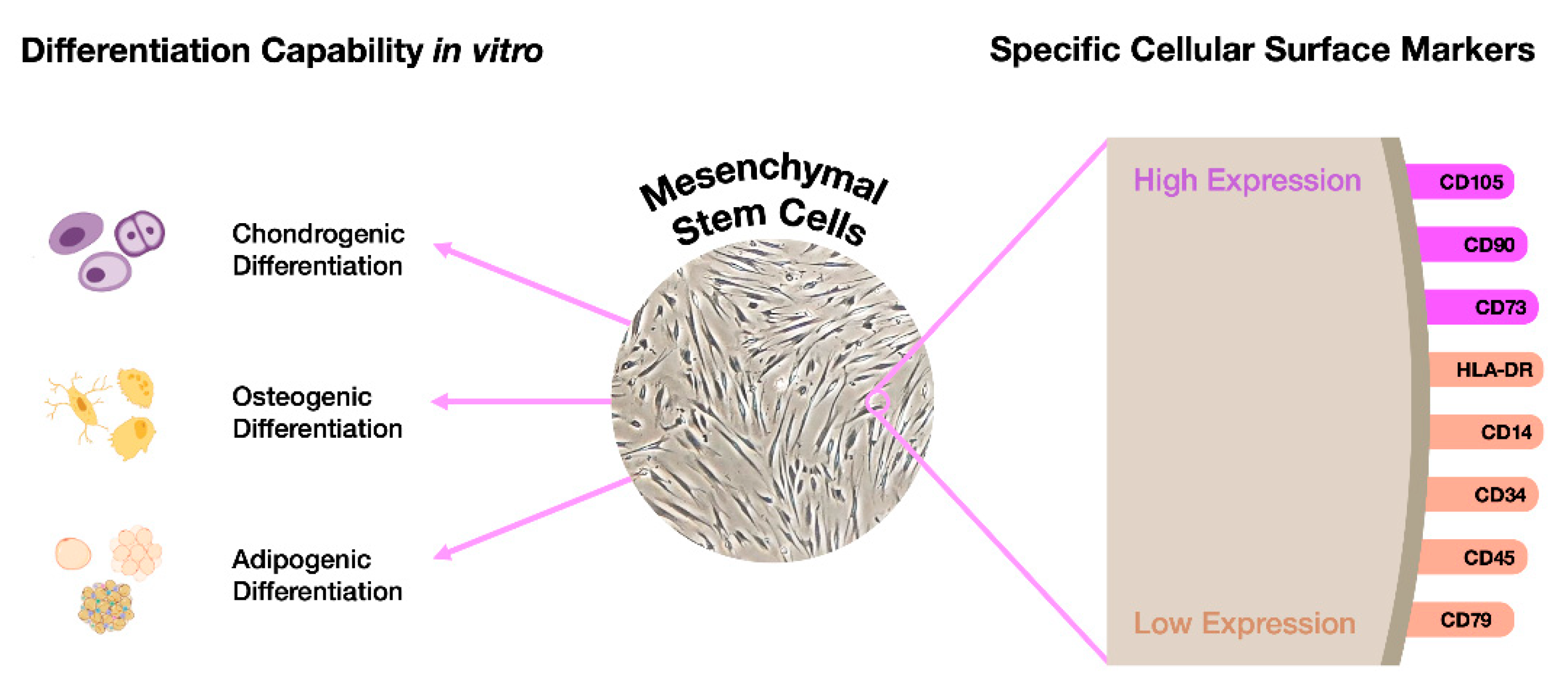

- Liu, J.; Gao, J.; Liang, Z.; Gao, C.; Niu, Q.; Wu, F.; Zhang, L. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Microenvironment. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

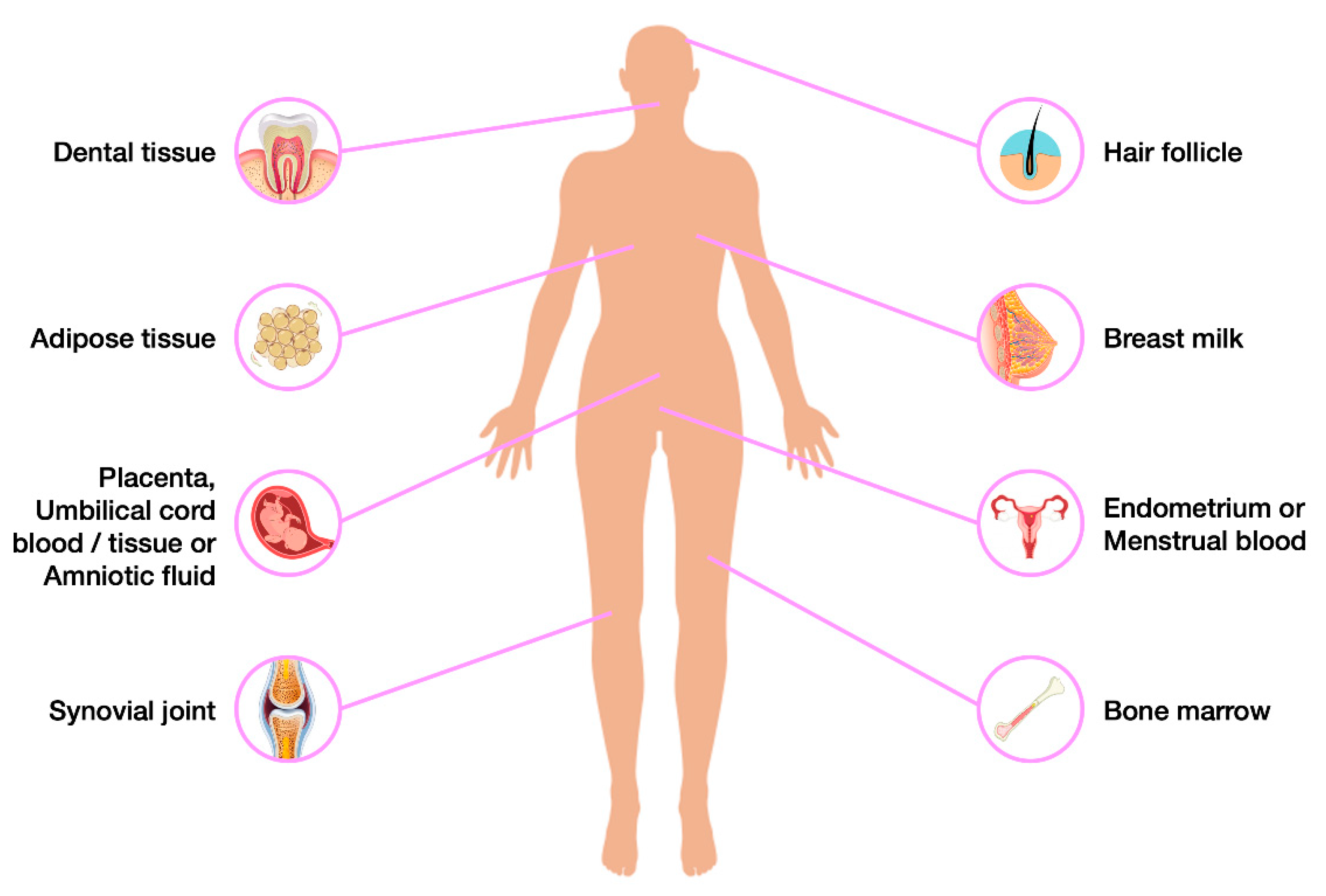

- Berebichez-Fridman, R.; Montero-Olvera, P.R. Sources and Clinical Applications of Mesenchymal Stem Cells State-of-the-Art Review. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2018, 18, e264–e277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macrin, D.; Joseph, J.P.; Pillai, A.A.; Devi, A. Eminent Sources of Adult Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Therapeutic Imminence. Stem Cell Rev. Reports 2017, 13, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.T.J.; Gronthos, S.; Shi, S. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology & Medicine: Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Dental Tissues vs. Those from Other Sources: Their Biology and Role in Regenerative Medicine. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 88, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gronthos, S.; Mankani, M.; Brahim, J.; Robey, P.G.; Shi, S. Postnatal Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells (DPSCs) in Vitro and in Vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97, 13625–13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuti, N.; Corallo, C.; Chan, B.M.F.; Ferrari, M.; Gerami-Naini, B. Multipotent Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells: A Literature Review. Stem Cell Rev. Reports 2016, 12, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koussoulakou, D.S.; Margaritis, L.H.; Koussoulakos, S.L. A Curriculum Vitae of Teeth: Evolution, Generation, Regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2009, 12, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaukua, N.; Shahidi, M.K.; Konstantinidou, C.; Dyachuk, V.; Kaucka, M.; Furlan, A.; An, Z.; Wang, L.; Hultman, I.; Ährlund-Richter, L.; et al. Glial Origin of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in a Tooth Model System. Nature 2014, 513, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronthos, S.; Brahim, J.; Li, W.; Fisher, L.W.; Cherman, N.; Boyde, A.; Denbesten, P.; Robey, P.G.; Shi, S. Stem Cell Properties Of. J. Dent. Res. 2002, 81, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, M.; Gronthos, S.; Zhao, M.; Lu, B.; Fisher, L.W.; Robey, P.G.; Shi, S. SHED: Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 5807–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Madhoun, A.; Sindhu, S.; Haddad, D.; Atari, M.; Ahmad, R.; Al-Mulla, F. Dental Pulp Stem Cells Derived From Adult Human Third Molar Tooth: A Brief Review. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handa, K.; Saito, M.; Yamauchi, M.; Kiyono, T.; Sato, S.; Teranaka, T.; Narayanan, A.S. Cementum Matrix Formation in Vivo by Cultured Dental Follicle Cells. Bone 2002, 31, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morsczeck, C.; Götz, W.; Schierholz, J.; Zeilhofer, F.; Kühn, U.; Möhl, C.; Sippel, C.; Hoffmann, K.H. Isolation of Precursor Cells (PCs) from Human Dental Follicle of Wisdom Teeth. Matrix Biol. 2005, 24, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, S.; Zibandeh, N.; Genc, D.; Ozcan, E.M.; Goker, K.; Akkoc, T. The Comparison of the Immunologic Properties of Stem Cells Isolated from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth, Dental Pulp, and Dental Follicles. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, Q.; Zou, D.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Q. Comparison of Osteogenic Differentiation Potential of Human Dental-Derived Stem Cells Isolated from Dental Pulp, Periodontal Ligament, Dental Follicle, and Alveolar Bone. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunimatsu, R.; Nakajima, K.; Awada, T.; Tsuka, Y.; Abe, T.; Ando, K.; Hiraki, T.; Kimura, A.; Tanimoto, K. Comparative Characterization of Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth, Dental Pulp, and Bone Marrow–Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 501, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Jeon, H.J.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, K.Y.; Park, K.; Lee, E.S.; Choi, J.M.; Park, C.G.; Jeon, S.H. Comparative Analysis of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Surface Marker Expression for Human Dental Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Regen. Med. 2013, 8, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, J.; Qiao, X.; Yu, M.; Tang, W.; Wang, H.; Guo, W.; Tian, W. Comparison of Odontogenic Differentiation of Human Dental Follicle Cells and Human Dental Papilla Cells. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakopoulou, A.; Leyhausen, G.; Volk, J.; Tsiftsoglou, A.; Garefis, P.; Koidis, P.; Geurtsen, W. Comparative Analysis of in Vitro Osteo/Odontogenic Differentiation Potential of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells (DPSCs) and Stem Cells from the Apical Papilla (SCAP). Arch. Oral Biol. 2011, 56, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Miura, M.; Seo, B.M.; Robey, P.G.; Bartold, P.M.; Gronthos, S. The Efficacy of Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Regenerate and Repair Dental Structures. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2005, 8, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleuterio, E.; Trubiani, O.; Sulpizio, M.; Di Giuseppe, F.; Pierdomenico, L.; Marchisio, M.; Giancola, R.; Giammaria, G.; Miscia, S.; Caputi, S.; et al. Proteome of Human Stem Cells from Periodontal Ligament and Dental Pulp. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winning, L.; El Karim, I.A.; Lundy, F.T. A Comparative Analysis of the Osteogenic Potential of Dental Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2019, 28, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Subbarao, R.B.; Kim, E.J.; Bharti, D.; Jang, S.J.; Park, J.S.; Shivakumar, S.B.; Lee, S.L.; Kang, D.; Byun, J.H.; et al. In Vitro Comparative Analysis of Human Dental Stem Cells from a Single Donor and Its Neuronal Differentiation Potential Evaluated by Electrophysiology. Life Sci. 2016, 154, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, R.; Kumar, B.M.; Lee, W.J.; Jeon, R.H.; Jang, S.J.; Lee, Y.M.; Park, B.W.; Byun, J.H.; Ahn, C.S.; Kim, J.W.; et al. Multilineage Potential and Proteomic Profiling of Human Dental Stem Cells Derived from a Single Donor. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 320, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Xu, W.; Chen, H.; Li, S.; Dou, R.; Shen, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Hong, Y.; He, J. Comparison of the Differentiation of Dental Pulp Stem Cells and Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells into Neuron-like Cells and Their Effects on Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai). 2020, 52, 1016–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morsczeck, C.; Völlner, F.; Saugspier, M.; Brandl, C.; Reichert, T.E.; Driemel, O.; Schmalz, G. Comparison of Human Dental Follicle Cells (DFCs) and Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth (SHED) after Neural Differentiation in Vitro. Clin. Oral Investig. 2010, 14, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, D.F.; Sunaga, D.Y.; Kobayashi, G.S.; Aguena, M.; Raposo-Amaral, C.E.; Masotti, C.; Cruz, L.A.; Pearson, P.L.; Passos-Bueno, M.R. Human Stem Cell Cultures from Cleft Lip/Palate Patients Show Enrichment of Transcripts Involved in Extracellular Matrix Modeling By Comparison to Controls. Stem Cell Rev. Reports 2011, 7, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.L.; Chen, M.F.; Liao, C.H.; Pang, C.Y.; Lin, P.Y. A Simple and Efficient Method for Generating Nurr1-Positive Neuronal Stem Cells from Human Wisdom Teeth (TNSC) and the Potential of TNSC for Stroke Therapy. Cytotherapy 2009, 11, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gancheva, M.R.; Kremer, K.L.; Gronthos, S.; Koblar, S.A. Using Dental Pulp Stem Cells for Stroke Therapy. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, W.K.; Henshall, T.L.; Arthur, A.; Kremer, K.L.; Lewis, M.D.; Helps, S.C.; Field, J.; Hamilton-Bruce, M.A.; Warming, S.; Manavis, J.; et al. Human Adult Dental Pulp Stem Cells Enhance Poststroke Functional Recovery Through Non-Neural Replacement Mechanisms. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2012, 1, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Kim, H.; Tsuboi, N.; Yamamoto, A.; Akiyama, S.; Shi, Y.; Katsuno, T.; Kosugi, T.; Ueda, M.; Matsuo, S.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth in Models of Acute Kidney Injury. PLoS One 2015, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, M.A.; Martins, J.F.P.; Maria, D.A.; Wenceslau, C.V.; De Souza, D.M.; Kerkis, A.; Câmara, N.O.S.; Balieiro, J.C.C.; Kerkis, I. Immature Dental Pulp Stem Cells Showed Renotropic and Pericyte-Like Properties in Acute Renal Failure in Rats. Cell Med. 2015, 7, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Makino, Y.; Yamaza, H.; Akiyama, K.; Hoshino, Y.; Song, G.; Kukita, T.; Nonaka, K.; Shi, S.; Yamaza, T. Cryopreserved Dental Pulp Tissues of Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth Is a Feasible Stem Cell Resource for Regenerative Medicine. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakayama, H.; Hashimoto, N.; Matsushita, Y.; Matsubara, K.; Yamamoto, N.; Hasegawa, Y.; Ueda, M.; Yamamoto, A. Factors Secreted from Dental Pulp Stem Cells Show Multifaceted Benefits for Treating Acute Lung Injury in Mice. Cytotherapy 2015, 17, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, H.; Matsubara, K.; Sakai, K.; Ito, M.; Ohno, K.; Ueda, M.; Yamamoto, A. Dopaminergic Differentiation of Stem Cells from Human Deciduous Teeth and Their Therapeutic Benefits for Parkinsonian Rats. Brain Res. 2015, 1613, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, C.; Gan, Q.F.; Kathivaloo, P.; Mohamad, N.A.; Dhamodharan, J.; Krishnan, A.; Sengodan, B.; Palanimuthu, V.R.; Marimuthu, K.; Rajandas, H.; et al. Deciduous DPSCs Ameliorate MPTP-Mediated Neurotoxicity, Sensorimotor Coordination and Olfactory Function in Parkinsonian Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mita, T.; Furukawa-Hibi, Y.; Takeuchi, H.; Hattori, H.; Yamada, K.; Hibi, H.; Ueda, M.; Yamamoto, A. Conditioned Medium from the Stem Cells of Human Dental Pulp Improves Cognitive Function in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2015, 293, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Sugiyama, M.; Hattori, H.; Wakita, H.; Wakabayashi, T.; Ueda, M. Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Tooth-Derived Conditioned Medium Enhance Recovery of Focal Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. Tissue Eng. - Part A 2013, 19, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, M.; Yamamoto, A.; Kako, E.; Kaneko, N.; Matsubara, K.; Sakai, K.; Sawamoto, K.; Ueda, M. Human Dental Pulp-Derived Stem Cells Protect against Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury in Neonatal Mice. Stroke 2013, 44, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, K.; Matsushita, Y.; Sakai, K.; Kano, F.; Kondo, M.; Noda, M.; Hashimoto, N.; Imagama, S.; Ishiguro, N.; Suzumura, A.; et al. Secreted Ectodomain of Sialic Acid-Binding Ig-like Lectin-9 and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Promote Recovery after Rat Spinal Cord Injury by Altering Macrophage Polarity. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 2452–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, F. do C.; Marques, M.R.; Odorcyk, F.; Arcego, D.M.; Petenuzzo, L.; Aristimunha, D.; Vizuete, A.; Sanches, E.F.; Pereira, D.P.; Maurmann, N.; et al. Neuroprotector Effect of Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth Transplanted after Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury Involves Inhibition of Early Neuronal Apoptosis. Brain Res. 2017, 1663, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghipour, Z.; Karbalaie, K.; Kiani, A.; Niapour, A.; Bahramian, H.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H.; Baharvand, H. Transplantation of Undifferentiated and Induced Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth-Derived Stem Cells Promote Functional Recovery of Rat Spinal Cord Contusion Injury Model. Stem Cells Dev. 2012, 21, 1794–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Li, X.; Sun, L.; Guo, W.; Tian, W. Potential of Human Dental Stem Cells in Repairing the Complete Transection of Rat Spinal Cord. J. Neural Eng. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Cho, Y.A.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, S.Y.; Bae, W.J.; Kim, E.C. PIN1 Suppresses the Hepatic Differentiation of Pulp Stem Cells via Wnt3a. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaza, T.; Alatas, F.S.; Yuniartha, R.; Yamaza, H.; Fujiyoshi, J.K.; Yanagi, Y.; Yoshimaru, K.; Hayashida, M.; Matsuura, T.; Aijima, R.; et al. In Vivo Hepatogenic Capacity and Therapeutic Potential of Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth in Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prins, Henk-Jan, Schulten, Engelbert Bruggenkate, C. Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine T ISSUE E NGINEERING AND R EGENERATIVE M EDICINE Concise Review : New Frontiers in MicroRNA-Based Tissue Regeneration. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2014; 969–976. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Shibata, R.; Yamamoto, N.; Nishikawa, M. Dental Pulp-Derived Stem Cell Conditioned Medium Reduces Cardiac Injury Following Ischemia- Reperfusion. Nat. Publ. Gr. 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdugo, A.; O, E.L.L.L.E.D.; Orrijos, J.O.S.A.; A, R.A.P.A.Y. T ISSUE -S PECIFIC S TEM C ELLS Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells Improve Left Ventricular Function, Induce Angiogenesis, and Reduce Infarct Size in Rats with Acute Myocardial Infarction ´, a A MPARO R UIZ, b AND. 2008, 638–645. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sarrà, E.; Montori, S.; Gil-Recio, C.; Núñez-Toldrà, R.; Costamagna, D.; Rotini, A.; Atari, M.; Luttun, A.; Sampaolesi, M. Human Dental Pulp Pluripotent-like Stem Cells Promote Wound Healing and Muscle Regeneration. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerkis, I.; Ambrosio, C.E.; Kerkis, A.; Martins, D.S.; Zucconi, E.; Fonseca, S.A.S.; Cabral, R.M.; Maranduba, C.M.C.; Gaiad, T.P.; Morini, A.C.; et al. Early Transplantation of Human Immature Dental Pulp Stem Cells from Baby Teeth to Golden Retriever Muscular Dystrophy (GRMD) Dogs: Local or Systemic? J. Transl. Med. 2008, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisciotta, A.; Riccio, M.; Carnevale, G.; Lu, A.; De Biasi, S.; Gibellini, L.; La Sala, G.B.; Bruzzesi, G.; Ferrari, A.; Huard, J.; et al. Stem Cells Isolated from Human Dental Pulp and Amniotic Fluid Improve Skeletal Muscle Histopathology in Mdx/SCID Mice. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, M.; Feitosa, T.; Ii, L.F.; Cristina, P.; Iii, B.B.; Valverde, C.; Iv, W.; X, M.A.M.; Eduardo, C.; Ix, A. Successful Transplant of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Induced Osteonecrosis of the Ovine Sucesso No Transplante de Células Tronco Mesenquimais Em Ovinos Com Osteonecrose Induzida Da Cabeça Do Fêmur. Resultados Preliminares. Acta Cir. Bras. 2010, 25, 416–422. [Google Scholar]

- Novais, A.; Lesieur, J.; Sadoine, J.; Slimani, L.; Baroukh, B.; Saubaméa, B.; Schmitt, A.; Vital, S.; Poliard, A.; Hélary, C.; et al. Priming Dental Pulp Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth with Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 Enhances Mineralization Within Tissue-Engineered Constructs Implanted in Craniofacial Bone Defects. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2019, 8, 844–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asutay, F.; Polat, S.; Gül, M.; Subaşi, C.; Kahraman, S.A.; Karaöz, E. The Effects of Dental Pulp Stem Cells on Bone Regeneration in Rat Calvarial Defect Model: Micro-Computed Tomography and Histomorphometric Analysis. Arch. Oral Biol. 2015, 60, 1729–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.; Shi, X.; Xiao, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.S.; Wu, C.T.; Wang, H. Transplantation of Hepatocyte Growth Factor-Modified Dental Pulp Stem Cells Prevents Bone Loss in the Early Phase of Ovariectomy-Induced Osteoporosis. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018, 29, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishino, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Ebisawa, K.; Nakamura, S.; Okabe, K.; Umemura, E.; Hara, K.; Ueda, M. Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth (SHED) Enhance Wound Healing and the Possibility of Novel Cell Therapy. Cytotherapy 2011, 13, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishino, Y.; Ebisawa, K.; Yamada, Y.; Okabe, K.; Kamei, Y.; Ueda, M. Human Deciduous Teeth Dental Pulp Cells with Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor Enhance Wound Healing of Skin Defect. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2011, 22, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumoto-Akita, T.; Tsunekawa, S.; Yamamoto, A.; Uenishi, E.; Ishikawa, K.; Ogata, H.; Iida, A.; Ikeniwa, M.; Hosokawa, K.; Niwa, Y.; et al. Secreted Factors from Dental Pulp Stem Cells Improve Glucose Intolerance in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Mice by Increasing Pancreatic β-Cell Function. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2015, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanafi, M.M.; Rajeshwari, Y.B.; Gupta, S.; Dadheech, N.; Nair, P.D.; Gupta, P.K.; Bhonde, R.R. Transplantation of Islet-like Cell Clusters Derived from Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells Restores Normoglycemia in Diabetic Mice. Cytotherapy 2013, 15, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, B.; Hill, L.J.; Blanch, R.J.; Ward, K.; Logan, A.; Berry, M.; Leadbeater, W.; Scheven, B.A. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Mediated Neuroprotection and Functional Preservation of Retinal Ganglion Cells in a Rodent Model of Glaucoma. Cytotherapy 2016, 18, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, J.; Takahashi, N.; Matsumoto, T.; Yoshioka, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Nishikawa, M.; Hibi, H.; Ishigro, N.; Ueda, M.; Furukawa, K.; et al. Factors Secreted from Dental Pulp Stem Cells Show Multifaceted Benefits for Treating Experimental Rheumatoid Arthritis. Bone 2016, 83, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimojima, C.; Takeuchi, H.; Jin, S.; Parajuli, B.; Hattori, H.; Suzumura, A.; Hibi, H.; Ueda, M.; Yamamoto, A. Conditioned Medium from the Stem Cells of Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth Ameliorates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 4164–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, B.; Wu, D.; Xiang, L.; Fu, Y.; Kou, X.; Shi, S. Dental Pulp Stem Cells: From Discovery to Clinical Application. J. Endod. 2020, 46, S46–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Mao, J.; Liu, Y. Pulp Stem Cells Derived from Human Permanent and Deciduous Teeth: Biological Characteristics and Therapeutic Applications. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2020, 9, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, S.; Tomokiyo, A.; Hasegawa, D.; Hamano, S.; Sugii, H.; Maeda, H. Insight into the Role of Dental Pulp Stem Cells in Regenerative Therapy. Biology (Basel). 2020, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, A.K.; Reiter, L.T. Dental Pulp Stem Cells for the Study of Neurogenetic Disorders. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, R166–R171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, M.; Derrick Roberts, A.; Martin, E.; Rout-Pitt, N.; Gronthos, S.; Byers, S. Mucopolysaccharidosis Enzyme Production by Bone Marrow and Dental Pulp Derived Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2015, 114, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Liu, G.; Shi, Y.; Wu, R.; Yang, B.; He, T.; Fan, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; et al. Multipotential Differentiation of Human Urine-Derived Stem Cells: Potential for Therapeutic Applications in Urology. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 1840–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzarano, M.S.; D’Amario, D.; Siracusano, A.; Massetti, M.; Amodeo, A.; La Neve, F.; Maroni, C.R.; Mercuri, E.; Osman, H.; Scotton, C.; et al. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Myogenic Cells from Urine-Derived Stem Cells Recapitulate the Dystrophin Genotype and Phenotype. Hum. Gene Ther. 2016, 27, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Han, P.; Jiang, D.; Yang, S.; Cui, Q.; Li, Z. Effects of the Donor Age on Proliferation, Senescence and Osteogenic Capacity of Human Urine-Derived Stem Cells. Cytotechnology 2017, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzarano, M.S.; Rossi, R.; Grilli, A.; Fang, M.; Osman, H.; Sabatelli, P.; Antoniel, M.; Lu, Z.; Li, W.; Selvatici, R.; et al. Urine-Derived Stem Cells Express 571 Neuromuscular Disorders Causing Genes, Making Them a Potential in Vitro Model for Rare Genetic Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 716471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzarano, M.S.; Ferlini, A. Urinary Stem Cells as Tools to Study Genetic Disease: Overview of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabitha, K.R.; Chandran, D.; Shetty, A.K.; Upadhya, D. Delineating the Neuropathology of Lysosomal Storage Diseases Using Patient-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2022, 31, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disorder | Affected gene | Defective Enzyme | Stored substrate | Subtype | Generation of MPS-derived iPSCs | Drug Screening | Ex vivo gene therapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | iPSC | NPC | Mature Neurons | |||||||

| MPS I | IDUA | α-L-iduronidase | DS and HS | Hurler | Fibroblasts | [118,126,127] | [126,127] | |||

| Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts | [138] | [138] | ||||||||

| Hurler/Scheie | Fibroblasts | [126] | [126] | |||||||

| Scheie | Fibroblasts | [119] | ||||||||

| PBMCs | [126] | [126] | ||||||||

| MPS II | IDS | Iduronate-2-sulfatase | DS and HS | Fibroblasts | [123,133] | [123,133] | [133] | |||

| PBMCs | [114,115,116,134] | [124,134] | [124,134] | [134] | ||||||

| MPS III | SGSH | Sulfamidase | HS | A | Fibroblasts | [111] | ||||

| NAGLU | α-N-acetylglucosaminidase | B | Fibroblasts | [109,110,120,129] | [109,120,129] | [129] | [129] | |||

| Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts | [136,137] | [136,137] | [136,137] | |||||||

| HGSNAT | N-acetyltransferase | C | Fibroblasts | [113,121] | [121,122] | [121,122] | [121,122] | |||

| MPS VII | GUSB | β-Glucuronidase | DS, HS, and CS | Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts | [135] | [135] | [135] | |||

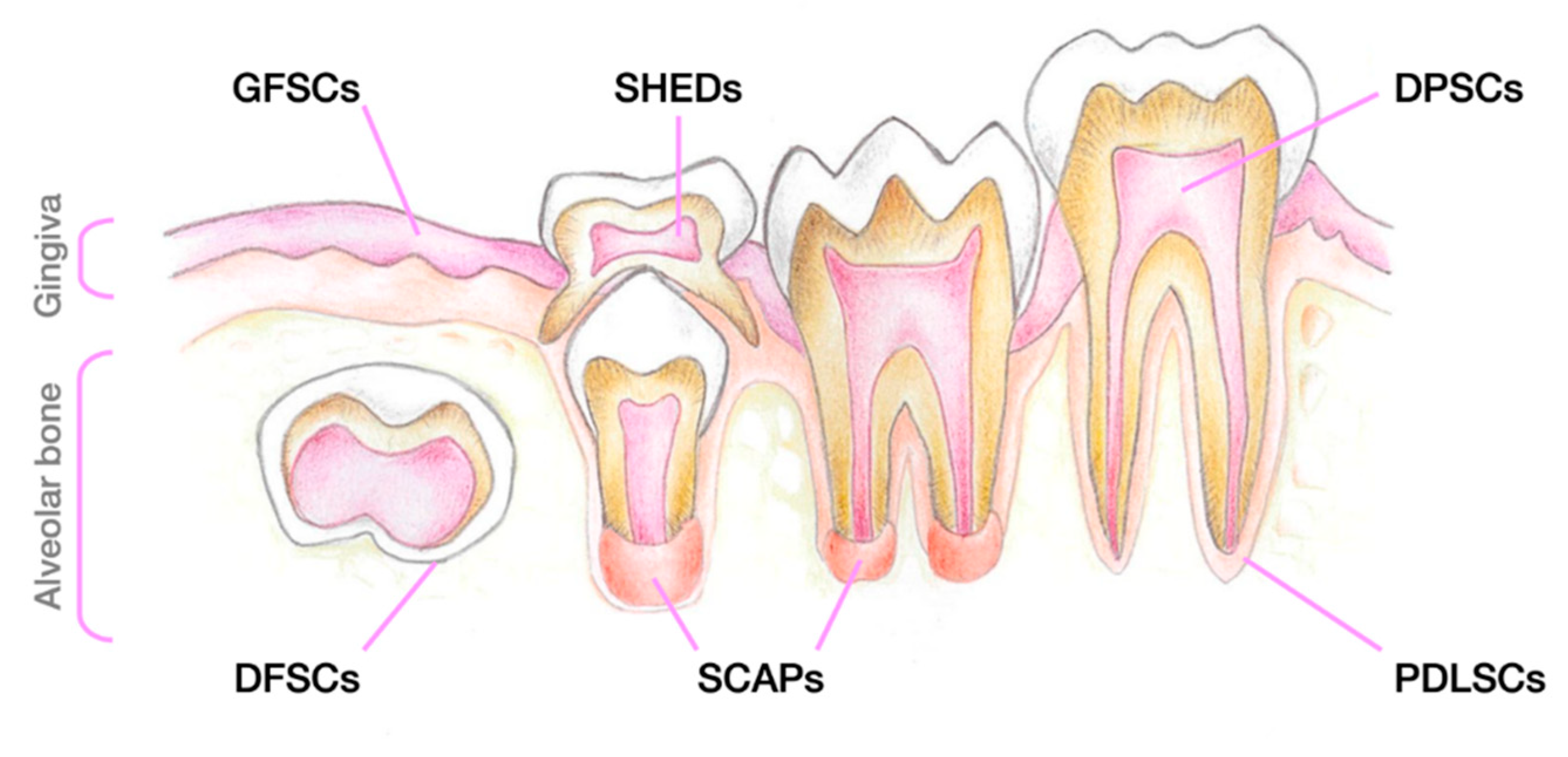

| Type of Differentiation | Potential Differentiation | References |

|---|---|---|

| Osteogenic | PDLSCs>DFSCs/SHEDs>DPSCs>SCAPs | [148,153,159,160,161,162] |

| Chondrogenic | DPSCs>SCAPs/DFSCs/PDLSCs | [153,161,162] |

| Adipogenic | DFSCs>DPSCs/SCAPs>PDLSCs | [153,162] |

| Neurogenic | SHEDs>PDLSCs>DPSCs>DFSCs>SCAPs | [161,163,164] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).