Submitted:

23 March 2023

Posted:

24 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. How to optimize workflow in Paediatric Emergency Departments?

3. How to optimize the use of structural approach?

4. How to rationalize the use of imaging methods?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lindner, G.; Woitok, B.K. Emergency Department Overcrowding. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2021, 133, 229–233. [CrossRef]

- Moylan, A.; Maconochie, I. Demand, Overcrowding and the Pediatric Emergency Department. CMAJ 2019, 191, E625–E626. [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, J.I.; Raban, M.Z.; Walter, S.R.; Douglas, H. Task Errors by Emergency Physicians Are Associated with Interruptions, Multitasking, Fatigue and Working Memory Capacity: A Prospective, Direct Observation Study. BMJ Qual Saf 2018, 27, 655–663. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.J.; Ernst, A.A.; Sills, M.R.; Quinn, B.J.; Johnson, A.; Nick, T.G. Development of a Novel Measure of Overcrowding in a Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2007, 23, 641–645. [CrossRef]

- Noel, G.; Jouve, E.; Fruscione, S.; Minodier, P.; Boiron, L.; Viudes, G.; Gentile, S. Real-Time Measurement of Crowding in Pediatric Emergency Department: Derivation and Validation Using Consensual Perception of Crowding (SOTU-PED). Pediatr Emerg Care 2021, 37, e1244–e1250. [CrossRef]

- Abudan, A.; Merchant, R.C. Multi-Dimensional Measurements of Crowding for Pediatric Emergency Departments: A Systematic Review. Global Pediatric Health 2021, 8, 2333794X21999153. [CrossRef]

- Doan, Q.; Wong, H.; Meckler, G.; Johnson, D.; Stang, A.; Dixon, A.; Sawyer, S.; Principi, T.; Kam, A.J.; Joubert, G.; et al. The Impact of Pediatric Emergency Department Crowding on Patient and Health Care System Outcomes: A Multicentre Cohort Study. CMAJ 2019, 191, E627–E635. [CrossRef]

- Kennebeck, S.S.; Timm, N.L.; Kurowski, E.M.; Byczkowski, T.L.; Reeves, S.D. The Association of Emergency Department Crowding and Time to Antibiotics in Febrile Neonates. Academic Emergency Medicine 2011, 18, 1380–1385. [CrossRef]

- Shenoi, R.; Ma, L.; Syblik, D.; Yusuf, S. Emergency Department Crowding and Analgesic Delay in Pediatric Sickle Cell Pain Crises. Pediatr Emerg Care 2011, 27, 911–917. [CrossRef]

- Sills, M.R.; Fairclough, D.; Ranade, D.; Kahn, M.G. Emergency Department Crowding Is Associated with Decreased Quality of Care for Children with Acute Asthma. Ann Emerg Med 2011, 57, 191-200.e1-7. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.M.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, Y.S.; Chung, H.S.; Chung, S.P.; Lee, J.H. The Effect of Overcrowding in Emergency Departments on the Admission Rate According to the Emergency Triage Level. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0247042. [CrossRef]

- Oredsson, S.; Jonsson, H.; Rognes, J.; Lind, L.; Göransson, K.E.; Ehrenberg, A.; Asplund, K.; Castrén, M.; Farrohknia, N. A Systematic Review of Triage-Related Interventions to Improve Patient Flow in Emergency Departments. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2011, 19, 43. [CrossRef]

- Weinick, R.M.; Burns, R.M.; Mehrotra, A. Many Emergency Department Visits Could Be Managed at Urgent Care Centers and Retail Clinics. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010, 29, 1630–1636. [CrossRef]

- Hampers, L.C.; Cha, S.; Gutglass, D.J.; Binns, H.J.; Krug, S.E. Fast Track and the Pediatric Emergency Department: Resource Utilization and Patient Outcomes. Academic Emergency Medicine 1999, 6, 1153–1159. [CrossRef]

- Hinson, J.S.; Martinez, D.A.; Cabral, S.; George, K.; Whalen, M.; Hansoti, B.; Levin, S. Triage Performance in Emergency Medicine: A Systematic Review. Ann Emerg Med 2019, 74, 140–152. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Mirhaghi, A.; Najafi, Z.; Shafaee, H.; Hamechizfahm Roudi, M. Are Pediatric Triage Systems Reliable in the Emergency Department? Emergency Medicine International 2020, 2020, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, G.; Jelinek, G.A.; Scott, D.; Gerdtz, M.F. Emergency Department Triage Revisited. Emerg Med J 2010, 27, 86–92. [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraman, M.M.; Alder, R.N.; Copstein, L.; Al-Yousif, N.; Suss, R.; Zarychanski, R.; Doupe, M.B.; Berthelot, S.; Mireault, J.; Tardif, P.; et al. Impact of Employing Primary Healthcare Professionals in Emergency Department Triage on Patient Flow Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e052850. [CrossRef]

- Abdulwahid, M.A.; Booth, A.; Kuczawski, M.; Mason, S.M. The Impact of Senior Doctor Assessment at Triage on Emergency Department Performance Measures: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Comparative Studies. Emerg Med J 2016, 33, 504–513. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-H.; Chan, N.B.; Leung, J.M.Y.; Meng, H.; So, A.M.-C.; Tsoi, K.K.F.; Graham, C.A. An Integrated Approach of Machine Learning and Systems Thinking for Waiting Time Prediction in an Emergency Department. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2020, 139, 104143. [CrossRef]

- Levin, S.; Toerper, M.; Hamrock, E.; Hinson, J.S.; Barnes, S.; Gardner, H.; Dugas, A.; Linton, B.; Kirsch, T.; Kelen, G. Machine-Learning-Based Electronic Triage More Accurately Differentiates Patients With Respect to Clinical Outcomes Compared With the Emergency Severity Index. Ann Emerg Med 2018, 71, 565-574.e2. [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, A.; Laven, M. Influence of Artificial Intelligence on the Work Design of Emergency Department Clinicians a Systematic Literature Review. BMC Health Serv Res 2022, 22, 669. [CrossRef]

- Worster, A.; Gilboy, N.; Fernandes, C.M.; Eitel, D.; Eva, K.; Geisler, R.; Tanabe, P. Assessment of Inter-Observer Reliability of Two Five-Level Triage and Acuity Scales: A Randomized Controlled Trial. CJEM 2004, 6, 240–245. [CrossRef]

- Recznik, C.T.; Simko, L.M. Pediatric Triage Education: An Integrative Literature Review. Journal of Emergency Nursing 2018, 44, 605-613.e9. [CrossRef]

- Cicero, M.X.; Auerbach, M.A.; Zigmont, J.; Riera, A.; Ching, K.; Baum, C.R. Simulation Training with Structured Debriefing Improves Residents’ Pediatric Disaster Triage Performance. Prehosp Disaster Med 2012, 27, 239–244. [CrossRef]

- Cicero, M.X.; Whitfill, T.; Overly, F.; Baird, J.; Walsh, B.; Yarzebski, J.; Riera, A.; Adelgais, K.; Meckler, G.D.; Baum, C.; et al. Pediatric Disaster Triage: Multiple Simulation Curriculum Improves Prehospital Care Providers’ Assessment Skills. Prehospital Emergency Care 2017, 21, 201–208. [CrossRef]

- Sanddal, T.L.; Loyacono, T.; Sanddal, N.D. Effect of JumpSTART Training on Immediate and Short-Term Pediatric Triage Performance. Pediatr Emerg Care 2004, 20, 749–753. [CrossRef]

- Tuyisenge, L.; Kyamanya, P.; Van Steirteghem, S.; Becker, M.; English, M.; Lissauer, T. Knowledge and Skills Retention Following Emergency Triage, Assessment and Treatment plus Admission Course for Final Year Medical Students in Rwanda: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Arch Dis Child 2014, 99, 993–997. [CrossRef]

- Alberti, S.G. Transforming Emergency Care in England 2004.

- Lamont, S.S. “See and Treat”: Spreading like Wildfire? A Qualitative Study into Factors Affecting Its Introduction and Spread. Emergency Medicine Journal 2005, 22, 548–552. [CrossRef]

- Sakr, M.; Angus, J.; Perrin, J.; Nixon, C.; Nicholl, J.; Wardrope, J. Care of Minor Injuries by Emergency Nurse Practitioners or Junior Doctors: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 1999, 354, 1321–1326. [CrossRef]

- Blick, C.; Vinograd, A.; Chung, J.; Nguyen, E.; Abbadessa, M.K.F.; Gaines, S.; Chen, A. Procedural Competency for Ultrasound-Guided Peripheral Intravenous Catheter Insertion for Nurses in a Pediatric Emergency Department. J Vasc Access 2021, 22, 232–237. [CrossRef]

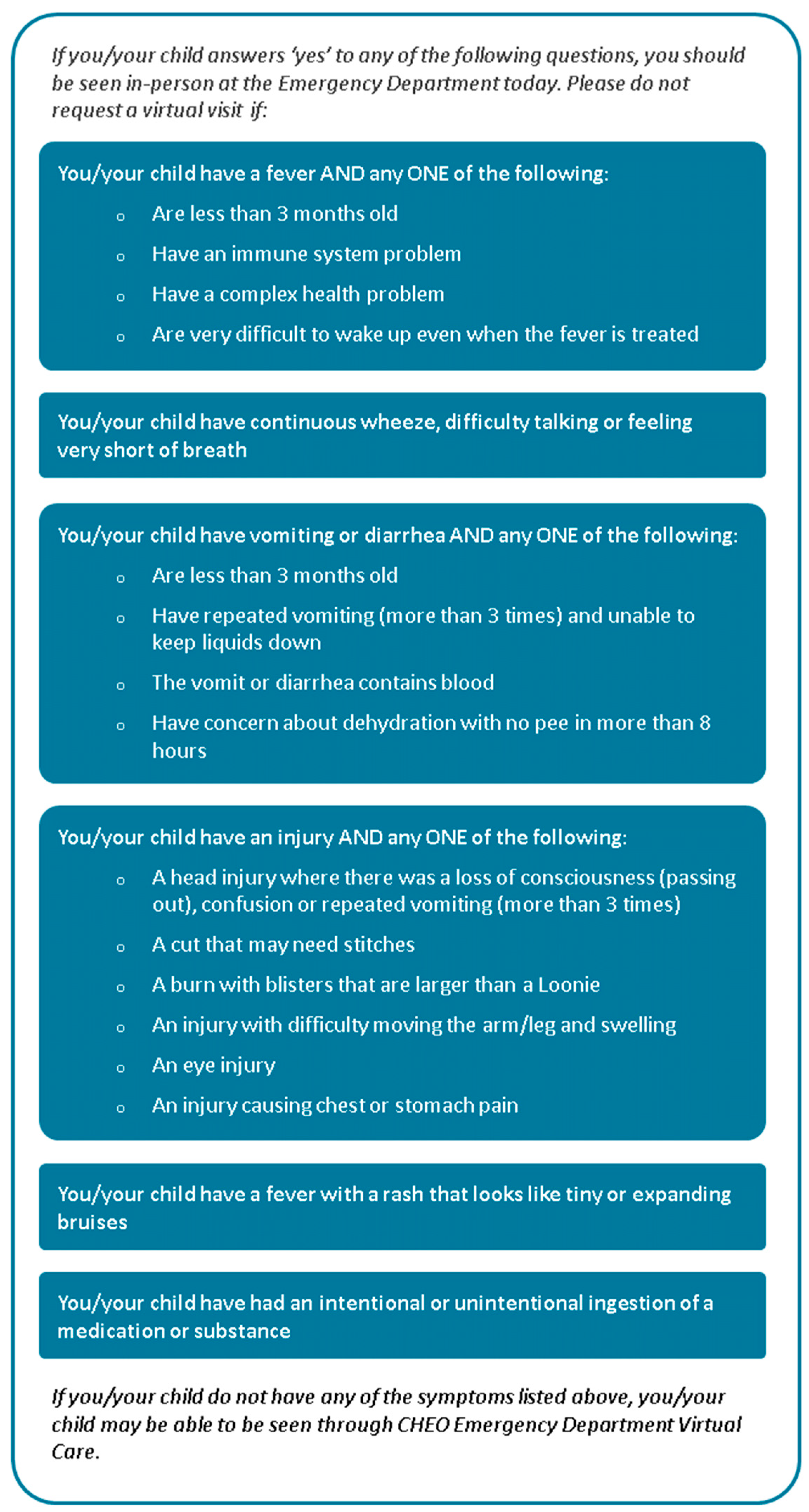

- Reid, S.; Bhatt, M.; Zemek, R.; Tse, S. Virtual Care in the Pediatric Emergency Department: A New Way of Doing Business? Can J Emerg Med 2021, 23, 80–84. [CrossRef]

- Brova, M.; Boggs, K.M.; Zachrison, K.S.; Freid, R.D.; Sullivan, A.F.; Espinola, J.A.; Boyle, T.P.; Camargo, C.A. Pediatric Telemedicine Use in United States Emergency Departments. Acad Emerg Med 2018, 25, 1427–1432. [CrossRef]

- Cotton, J.; Bullard-Berent, J.; Sapien, R. Virtual Pediatric Emergency Department Telehealth Network Program: A Case Series. Pediatr Emerg Care 2020, 36, 217–221. [CrossRef]

- Doan, Q.; Genuis, E.D.; Yu, A. Trends in Use in a Canadian Pediatric Emergency Department. CJEM 2014, 16, 405–410. [CrossRef]

- Stang, A.S.; McGillivray, D.; Bhatt, M.; Colacone, A.; Soucy, N.; Léger, R.; Afilalo, M. Markers of Overcrowding in a Pediatric Emergency Department. Academic Emergency Medicine 2010, 17, 151–156. [CrossRef]

- Ajmi, I.; Zgaya, H.; Gammoudi, L.; Hammadi, S.; Martinot, A.; Beuscart, R.; Renard, J.-M. Mapping Patient Path in the Pediatric Emergency Department: A Workflow Model Driven Approach. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2015, 54, 315–328. [CrossRef]

- Aronsky, D.; Jones, I.; Lanaghan, K.; Slovis, C.M. Supporting Patient Care in the Emergency Department with a Computerized Whiteboard System. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2008, 15, 184–194. [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.S.; Haimovich, A.D.; Taylor, R.A. Predicting Hospital Admission at Emergency Department Triage Using Machine Learning. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0201016. [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.A.; Liu, N.; Wu, S.X.; Shen, Y.; Lam, S.S.W.; Ong, M.E.H. Predicting Hospital Admission at the Emergency Department Triage: A Novel Prediction Model. Am J Emerg Med 2019, 37, 1498–1504. [CrossRef]

- Roquette, B.P.; Nagano, H.; Marujo, E.C.; Maiorano, A.C. Prediction of Admission in Pediatric Emergency Department with Deep Neural Networks and Triage Textual Data. Neural Networks 2020, 126, 170–177. [CrossRef]

- Kadri, F.; Chaabane, S.; Tahon, C. A Simulation-Based Decision Support System to Prevent and Predict Strain Situations in Emergency Department Systems. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory 2014, 42, 32–52. [CrossRef]

- Mazzocato, P.; Holden, R.J.; Brommels, M.; Aronsson, H.; Bäckman, U.; Elg, M.; Thor, J. How Does Lean Work in Emergency Care? A Case Study of a Lean-Inspired Intervention at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. BMC Health Serv Res 2012, 12, 28. [CrossRef]

- Murrell, K.L.; Offerman, S.R.; Kauffman, M.B. Applying Lean: Implementation of a Rapid Triage and Treatment System. West J Emerg Med 2011, 12, 184–191.

- Kuhlmann, S.; Piel, M.; Wolf, O.T. Impaired Memory Retrieval after Psychosocial Stress in Healthy Young Men. J Neurosci 2005, 25, 2977–2982. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Mackenzie, C.F.; Group, L. Decision Making in Dynamic Environments: Fixation Errors and Their Causes. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 1995, 39, 469–473. [CrossRef]

- Lingard, L.; Espin, S.; Whyte, S.; Regehr, G.; Baker, G.R.; Reznick, R.; Bohnen, J.; Orser, B.; Doran, D.; Grober, E. Communication Failures in the Operating Room: An Observational Classification of Recurrent Types and Effects. Qual Saf Health Care 2004, 13, 330–334. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.D.; Sanderson, P.; McIntosh, C.A.; Kolawole, H. The Effect of Two Cognitive Aid Designs on Team Functioning during Intra-Operative Anaphylaxis Emergencies: A Multi-Centre Simulation Study. Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 389–404. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.D.; Mehra, R. The Effects of a Displayed Cognitive Aid on Non-Technical Skills in a Simulated “can’t Intubate, Can’t Oxygenate” Crisis. Anaesthesia 2014, 69, 669–677. [CrossRef]

- Hepner, D.L.; Arriaga, A.F.; Cooper, J.B.; Goldhaber-Fiebert, S.N.; Gaba, D.M.; Berry, W.R.; Boorman, D.J.; Bader, A.M. Operating Room Crisis Checklists and Emergency Manuals. Anesthesiology 2017, 127, 384–392. [CrossRef]

- Weller, J.; Boyd, M. Making a Difference Through Improving Teamwork in the Operating Room: A Systematic Review of the Evidence on What Works. Curr Anesthesiol Rep 2014, 4, 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, G.D.; Shannon, E.M.; Dawes, A.J.; Rollo, J.C.; Nguyen, D.K.; Russell, M.M.; Ko, C.Y.; Maggard-Gibbons, M.A. Teamwork, Communication and Safety Climate: A Systematic Review of Interventions to Improve Surgical Culture. BMJ Qual Saf 2015, 24, 458–467. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.; Robertson, D.; Rolfe, M.; Pascoe, S.; Passey, M.E.; Pit, S.W. Do Cognitive Aids Reduce Error Rates in Resuscitation Team Performance? Trial of Emergency Medicine Protocols in Simulation Training (TEMPIST) in Australia. Hum Resour Health 2020, 18, 1. [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, E.A.; Asch, S.M.; Adams, J.; Keesey, J.; Hicks, J.; DeCristofaro, A.; Kerr, E.A. The Quality of Health Care Delivered to Adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 2003, 348, 2635–2645. [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, T.A.; Cullum, N.; Dawson, D.; Lankshear, A.; Lowson, K.; Watt, I.; West, P.; Wright, D.; Wright, J. What’s the Evidence That NICE Guidance Has Been Implemented? Results from a National Evaluation Using Time Series Analysis, Audit of Patients’ Notes, and Interviews. BMJ 2004, 329, 999. [CrossRef]

- Runciman, W.B.; Hunt, T.D.; Hannaford, N.A.; Hibbert, P.D.; Westbrook, J.I.; Coiera, E.W.; Day, R.O.; Hindmarsh, D.M.; McGlynn, E.A.; Braithwaite, J. CareTrack: Assessing the Appropriateness of Health Care Delivery in Australia. Med J Aust 2012, 197, 100–105. [CrossRef]

- Sabharwal, S.; Patel, N.K.; Gauher, S.; Holloway, I.; Athanasiou, T.; Athansiou, T. High Methodologic Quality but Poor Applicability: Assessment of the AAOS Guidelines Using the AGREE II Instrument. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014, 472, 1982–1988. [CrossRef]

- Hogeveen, S.E.; Han, D.; Trudeau–Tavara, S.; Buck, J.; Brezden–Masley, C.B.; Quan, M.L.; Simmons, C.E. Comparison of International Breast Cancer Guidelines: Are We Globally Consistent? Cancer Guideline AGREEment. Curr Oncol 2012, 19, e184–e190. [CrossRef]

- Sabharwal, S.; Patel, V.; Nijjer, S.S.; Kirresh, A.; Darzi, A.; Chambers, J.C.; Malik, I.; Kooner, J.S.; Athanasiou, T. Guidelines in Cardiac Clinical Practice: Evaluation of Their Methodological Quality Using the AGREE II Instrument. J R Soc Med 2013, 106, 315–322. [CrossRef]

- Knai, C.; Brusamento, S.; Legido-Quigley, H.; Saliba, V.; Panteli, D.; Turk, E.; Car, J.; McKee, M.; Busse, R. Systematic Review of the Methodological Quality of Clinical Guideline Development for the Management of Chronic Disease in Europe. Health Policy 2012, 107, 157–167. [CrossRef]

- Brosseau, L.; Rahman, P.; Toupin-April, K.; Poitras, S.; King, J.; De Angelis, G.; Loew, L.; Casimiro, L.; Paterson, G.; McEwan, J. A Systematic Critical Appraisal for Non-Pharmacological Management of Osteoarthritis Using the Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation II Instrument. PLoS One 2014, 9, e82986. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Tan, L.-M.; Khan, K.S.; Deng, T.; Huang, C.; Han, F.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Q.; Huang, D.; Wang, D.; et al. Determinants of Successful Guideline Implementation: A National Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2021, 21, 19. [CrossRef]

- Kredo, T.; Bernhardsson, S.; Machingaidze, S.; Young, T.; Louw, Q.; Ochodo, E.; Grimmer, K. Guide to Clinical Practice Guidelines: The Current State of Play. Int J Qual Health Care 2016, 28, 122–128. [CrossRef]

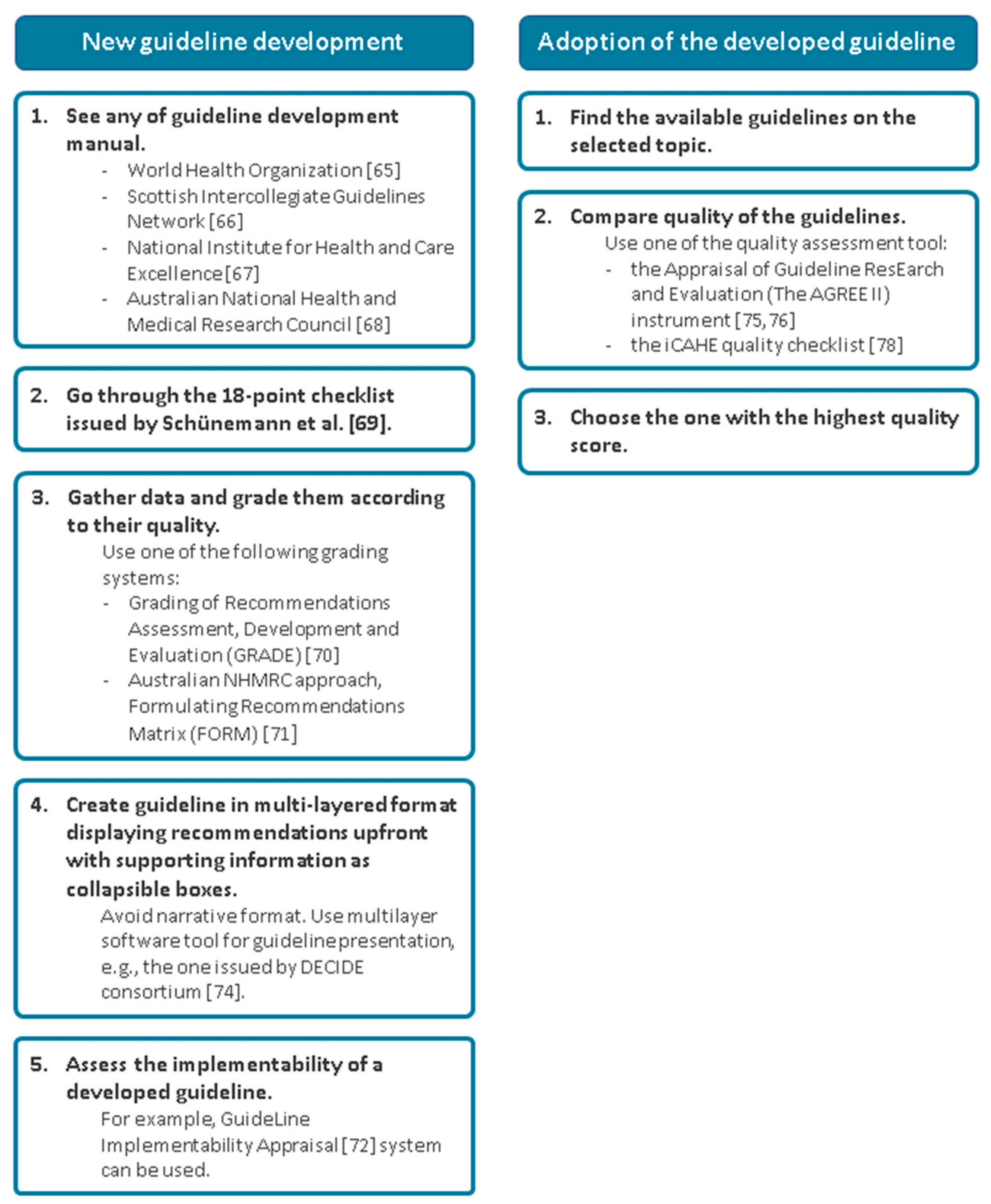

- World Health Organization WHO Handbook for Guideline Development; World Health Organization, 2014; ISBN 978-92-4-154896-0.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Sign 50: A Guideline Developer’s Handbook.; Healthcare Improvement Scotland, 2014; ISBN 978-1-909103-30-6.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence The Guidelines Manual; NICE Process and Methods Guides; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4731-1906-2.

- National Health & Medical Research Council (Australia), H.A.C. A Guide to the Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines.; AGPS: Canberra, 1999; ISBN 978-1-86496-048-8.

- Schünemann, H.J.; Wiercioch, W.; Etxeandia, I.; Falavigna, M.; Santesso, N.; Mustafa, R.; Ventresca, M.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Laisaar, K.-T.; Kowalski, S.; et al. Guidelines 2.0: Systematic Development of a Comprehensive Checklist for a Successful Guideline Enterprise. CMAJ 2014, 186, E123–E142. [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J.; GRADE Working Group GRADE: An Emerging Consensus on Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [CrossRef]

- Hillier, S.; Grimmer-Somers, K.; Merlin, T.; Middleton, P.; Salisbury, J.; Tooher, R.; Weston, A. FORM: An Australian Method for Formulating and Grading Recommendations in Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2011, 11, 23. [CrossRef]

- Shiffman, R.N.; Dixon, J.; Brandt, C.; Essaihi, A.; Hsiao, A.; Michel, G.; O’Connell, R. The GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA): Development of an Instrument to Identify Obstacles to Guideline Implementation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2005, 5, 23. [CrossRef]

- Brandt, L.; Vandvik, P.O.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Akl, E.A.; Thornton, J.; Rigau, D.; Adams, K.; O’Connor, P.; Guyatt, G.; Kristiansen, A. Multilayered and Digitally Structured Presentation Formats of Trustworthy Recommendations: A Combined Survey and Randomised Trial. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e011569. [CrossRef]

- Treweek, S.; Oxman, A.D.; Alderson, P.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Brandt, L.; Brożek, J.; Davoli, M.; Flottorp, S.; Harbour, R.; Hill, S.; et al. Developing and Evaluating Communication Strategies to Support Informed Decisions and Practice Based on Evidence (DECIDE): Protocol and Preliminary Results. Implement Sci 2013, 8, 6. [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Kho, M.E.; Browman, G.P.; Burgers, J.S.; Cluzeau, F.; Feder, G.; Fervers, B.; Graham, I.D.; Hanna, S.E.; Makarski, J.; et al. Development of the AGREE II, Part 1: Performance, Usefulness and Areas for Improvement. CMAJ 2010, 182, 1045–1052. [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Kho, M.E.; Browman, G.P.; Burgers, J.S.; Cluzeau, F.; Feder, G.; Fervers, B.; Graham, I.D.; Hanna, S.E.; Makarski, J.; et al. Development of the AGREE II, Part 2: Assessment of Validity of Items and Tools to Support Application. CMAJ 2010, 182, E472-478. [CrossRef]

- Chiappini, E.; Bortone, B.; Galli, L.; Martino, M. de Guidelines for the Symptomatic Management of Fever in Children: Systematic Review of the Literature and Quality Appraisal with AGREE II. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015404. [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, K.; Dizon, J.M.; Milanese, S.; King, E.; Beaton, K.; Thorpe, O.; Lizarondo, L.; Luker, J.; Machotka, Z.; Kumar, S. Efficient Clinical Evaluation of Guideline Quality: Development and Testing of a New Tool. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2014, 14, 63. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Haddour, M.; Colas, M.; Lefevre-Scelles, A.; Durand, Z.; Gillibert, A.; Roussel, M.; Joly, L.-M. A Cognitive Aid Improves Adherence to Guidelines for Critical Endotracheal Intubation in the Resuscitation Room: A Randomized Controlled Trial With Manikin-Based In Situ Simulation. Simul Healthc 2021. [CrossRef]

- Koers, L.; van Haperen, M.; Meijer, C.G.F.; van Wandelen, S.B.E.; Waller, E.; Dongelmans, D.; Boermeester, M.A.; Hermanides, J.; Preckel, B. Effect of Cognitive Aids on Adherence to Best Practice in the Treatment of Deteriorating Surgical Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial in a Simulation Setting. JAMA Surgery 2020, 155, e194704. [CrossRef]

- Haynes, A.B.; Weiser, T.G.; Berry, W.R.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Breizat, A.-H.S.; Dellinger, E.P.; Herbosa, T.; Joseph, S.; Kibatala, P.L.; Lapitan, M.C.M.; et al. A Surgical Safety Checklist to Reduce Morbidity and Mortality in a Global Population. New England Journal of Medicine 2009, 360, 491–499. [CrossRef]

- Bergs, J.; Lambrechts, F.; Simons, P.; Vlayen, A.; Marneffe, W.; Hellings, J.; Cleemput, I.; Vandijck, D. Barriers and Facilitators Related to the Implementation of Surgical Safety Checklists: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Evidence. BMJ Qual Saf 2015, 24, 776–786. [CrossRef]

- Burian, B.K.; Clebone, A.; Dismukes, K.; Ruskin, K.J. More Than a Tick Box: Medical Checklist Development, Design, and Use. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2018, 126, 223–232. [CrossRef]

- Goldhaber-Fiebert, S.N.; Pollock, J.; Howard, S.K.; Bereknyei Merrell, S. Emergency Manual Uses During Actual Critical Events and Changes in Safety Culture From the Perspective of Anesthesia Residents: A Pilot Study. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2016, 123, 641–649. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, S.C.; Anders, S.; Clebone, A.; Hughes, E.; Patel, V.; Zeigler, L.; Shi, Y.; Shotwell, M.S.; McEvoy, M.D.; Weinger, M.B. Mode of Information Delivery Does Not Effect Anesthesia Trainee Performance During Simulated Perioperative Pediatric Critical Events: A Trial of Paper Versus Electronic Cognitive Aids. Simulation in Healthcare 2016, 11, 385–393. [CrossRef]

- Clebone, A.; Burian, B.K.; Watkins, S.C.; Gálvez, J.A.; Lockman, J.L.; Heitmiller, E.S.; Members of the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia Quality and Safety Committee (see Acknowledgments) The Development and Implementation of Cognitive Aids for Critical Events in Pediatric Anesthesia: The Society for Pediatric Anesthesia Critical Events Checklists. Anesth Analg 2017, 124, 900–907. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.D. Lost in Translation? Comparing the Effectiveness of Electronic-Based and Paper-Based Cognitive Aids. Br J Anaesth 2017, 119, 869–871. [CrossRef]

- Grundgeiger, T.; Hahn, F.; Wurmb, T.; Meybohm, P.; Happel, O. The Use of a Cognitive Aid App Supports Guideline-Conforming Cardiopulmonary Resuscitations: A Randomized Study in a High-Fidelity Simulation. Resusc Plus 2021, 7, 100152. [CrossRef]

- Lelaidier, R.; Balança, B.; Boet, S.; Faure, A.; Lilot, M.; Lecomte, F.; Lehot, J.-J.; Rimmelé, T.; Cejka, J.-C. Use of a Hand-Held Digital Cognitive Aid in Simulated Crises: The MAX Randomized Controlled Trial. BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia 2017, 119, 1015–1021. [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, M.D.; Hand, W.R.; Stoll, W.D.; Furse, C.M.; Nietert, P.J. Adherence to Guidelines for the Management of Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity Is Improved by an Electronic Decision Support Tool and Designated ‘Reader.’ Reg Anesth Pain Med 2014, 39, 299–305. [CrossRef]

- Burden, A.R.; Carr, Z.J.; Staman, G.W.; Littman, J.J.; Torjman, M.C. Does Every Code Need a “Reader?” Improvement of Rare Event Management with a Cognitive Aid “Reader” during a Simulated Emergency: A Pilot Study. Simul Healthc 2012, 7, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.; Ganyani, R.; King, R.; Pandit, M. Does a Novel Method of Delivering the Safe Surgical Checklist Improve Compliance? A Closed Loop Audit. International Journal of Surgery 2016, 32, 99–108. [CrossRef]

- Safar, P.; Brown, T.C.; Holtey, W.J.; Wilder, R.J. Ventilation and Circulation with Closed-Chest Cardiac Massage in Man. JAMA 1961, 176, 574–576. [CrossRef]

- Moretti, M.A.; Cesar, L.A.M.; Nusbacher, A.; Kern, K.B.; Timerman, S.; Ramires, J.A.F. Advanced Cardiac Life Support Training Improves Long-Term Survival from in-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Resuscitation 2007, 72, 458–465. [CrossRef]

- Peran, D.; Kodet, J.; Pekara, J.; Mala, L.; Truhlar, A.; Cmorej, P.C.; Lauridsen, K.G.; Sari, F.; Sykora, R. ABCDE Cognitive Aid Tool in Patient Assessment – Development and Validation in a Multicenter Pilot Simulation Study. BMC Emergency Medicine 2020, 20, 95. [CrossRef]

- Olgers, T.J.; Dijkstra, R.S.; Drost-de Klerck, A.M.; Ter Maaten, J.C. The ABCDE Primary Assessment in the Emergency Department in Medically Ill Patients: An Observational Pilot Study. Neth J Med 2017, 75, 106–111.

- Weng, T.-I.; Huang, C.-H.; Ma, M.H.-M.; Chang, W.-T.; Liu, S.-C.; Wang, T.-D.; Chen, W.-J. Improving the Rate of Return of Spontaneous Circulation for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrests with a Formal, Structured Emergency Resuscitation Team. Resuscitation 2004, 60, 137–142. [CrossRef]

- Ornato, J.P.; Peberdy, M.A.; Reid, R.D.; Feeser, V.R.; Dhindsa, H.S. Impact of Resuscitation System Errors on Survival from In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Resuscitation 2012, 83, 63–69. [CrossRef]

- Soar, J.; Böttiger, B.W.; Carli, P.; Couper, K.; Deakin, C.D.; Djärv, T.; Lott, C.; Olasveengen, T.; Paal, P.; Pellis, T.; et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Adult Advanced Life Support. Resuscitation 2021, 161, 115–151. [CrossRef]

- Abdolrazaghnejad, A.; Banaie, M.; Safdari, M. Ultrasonography in Emergency Department; a Diagnostic Tool for Better Examination and Decision-Making. Adv J Emerg Med 2017, 2, e7. [CrossRef]

- Valle Alonso, J.; Turpie, J.; Farhad, I.; Ruffino, G. Protocols for Point-of-Care-Ultrasound (POCUS) in a Patient with Sepsis; An Algorithmic Approach. BEAT 2019, 7, 67–71. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, P.R.; Milne, J.; Diegelmann, L.; Lamprecht, H.; Stander, M.; Lussier, D.; Pham, C.; Henneberry, R.; Fraser, J.M.; Howlett, M.K.; et al. Does Point-of-Care Ultrasonography Improve Clinical Outcomes in Emergency Department Patients With Undifferentiated Hypotension? An International Randomized Controlled Trial From the SHoC-ED Investigators. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2018, 72, 478–489. [CrossRef]

- Mosier, J.M.; Stolz, U.; Milligan, R.; Roy-Chaudhury, A.; Lutrick, K.; Hypes, C.D.; Billheimer, D.; Cairns, C.B. Impact of Point-of-Care Ultrasound in the Emergency Department on Care Processes and Outcomes in Critically Ill Nontraumatic Patients. Critical Care Explorations 2019, 1, e0019. [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, A.J.; Shokoohi, H.; Loesche, M.; Patel, R.C.; Kimberly, H.; Liteplo, A. Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Morbidity and Mortality Cases in Emergency Medicine: Who Benefits the Most? West J Emerg Med 2020, 21, 172–178. [CrossRef]

- Ultrasound Guidelines: Emergency, Point-of-Care and Clinical Ultrasound Guidelines in Medicine. Ann Emerg Med 2017, 69, e27–e54. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, R.L.; Hsu, D.; Nagler, J.; Chen, L.; Gallagher, R.; Levy, J.A. Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellow Training in Ultrasound: Consensus Educational Guidelines. Academic Emergency Medicine 2013, 20, 300–306. [CrossRef]

- Blehar, D.J.; Barton, B.; Gaspari, R.J. Learning Curves in Emergency Ultrasound Education. Academic Emergency Medicine 2015, 22, 574–582. [CrossRef]

- Lewiss, R.E.; Hoffmann, B.; Beaulieu, Y.; Phelan, M.B. Point-of-Care Ultrasound Education. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 2014, 33, 27–32. [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; van Holsbeeck, L.; Musial, J.L.; Parker, A.; Bouffard, J.A.; Bridge, P.; Jackson, M.; Dulchavsky, S.A. A Pilot Study of Comprehensive Ultrasound Education at the Wayne State University School of Medicine. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 2008, 27, 745–749. [CrossRef]

- Bahner, D.P.; Royall, N.A. Advanced Ultrasound Training for Fourth-Year Medical Students: A Novel Training Program at The Ohio State University College of Medicine. Acad Med 2013, 88, 206–213. [CrossRef]

- Boccatonda, A. Emergency Ultrasound: Is It Time for Artificial Intelligence? JCM 2022, 11, 3823. [CrossRef]

- Nti, B.; Lehmann, A.S.; Haddad, A.; Kennedy, S.K.; Russell, F.M. Artificial Intelligence-Augmented Pediatric Lung POCUS: A Pilot Study of Novice Learners. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine n/a. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gajjala, S.; Agrawal, P.; Tison, G.H.; Hallock, L.A.; Beussink-Nelson, L.; Lassen, M.H.; Fan, E.; Aras, M.A.; Jordan, C.; et al. Fully Automated Echocardiogram Interpretation in Clinical Practice. Circulation 2018, 138, 1623–1635. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mao, R.; Li, F.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Deep Learning Radiomics Can Predict Axillary Lymph Node Status in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 1236. [CrossRef]

- Chartier, L.B.; Bosco, L.; Lapointe-Shaw, L.; Chenkin, J. Use of Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Long Bone Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. CJEM 2017, 19, 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Ozkaya, E.; Topal, F.E.; Bulut, T.; Gursoy, M.; Ozuysal, M.; Karakaya, Z. Evaluation of an Artificial Intelligence System for Diagnosing Scaphoid Fracture on Direct Radiography. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2022, 48, 585–592. [CrossRef]

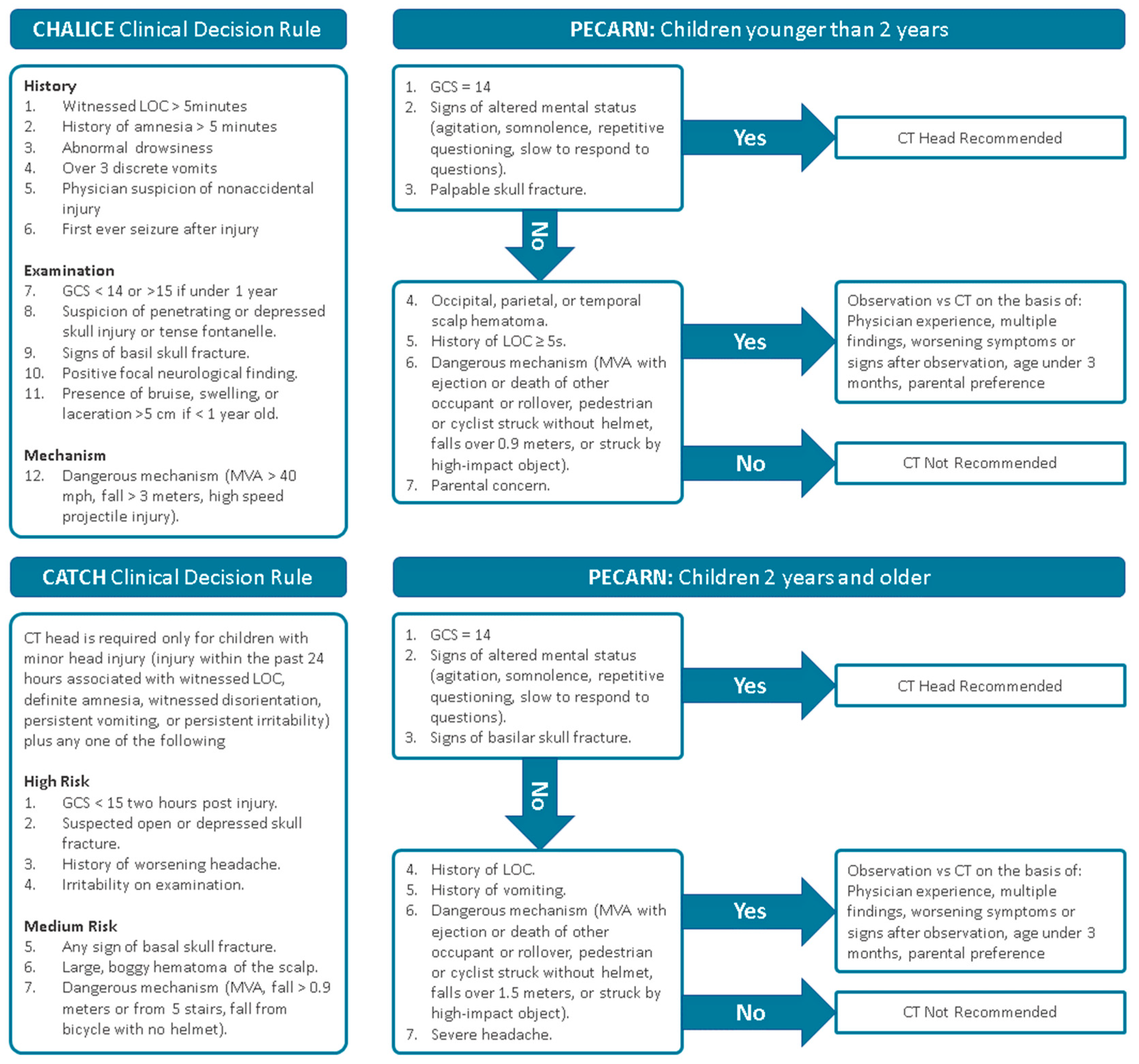

- McGraw, M.; Way, T. Comparison of PECARN, CATCH, and CHALICE Clinical Decision Rules for Pediatric Head Injury in the Emergency Department. CJEM 2019, 21, 120–124. [CrossRef]

- Harjai, M.M.; Sharma, A.K. HEAD INJURIES IN CHILDREN : ROLE OF X-RAY SKULL, CT SCAN BRAIN AND IN-HOSPITAL OBSERVATION. Medical Journal Armed Forces India 1998, 54, 322–324. [CrossRef]

- Radiation Risks and Pediatric Computed Tomography - NCI Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/radiation/pediatric-ct-scans (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Easter, J.S.; Bakes, K.; Dhaliwal, J.; Miller, M.; Caruso, E.; Haukoos, J.S. Comparison of PECARN, CATCH, and CHALICE Rules for Children with Minor Head Injury: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Emerg Med 2014, 64, 145–152, 152.e1-5. [CrossRef]

- Babl, F.E.; Borland, M.L.; Phillips, N.; Kochar, A.; Dalton, S.; McCaskill, M.; Cheek, J.A.; Gilhotra, Y.; Furyk, J.; Neutze, J.; et al. Accuracy of PECARN, CATCH, and CHALICE Head Injury Decision Rules in Children: A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet 2017, 389, 2393–2402. [CrossRef]

- Schonfeld, D.; Bressan, S.; Da Dalt, L.; Henien, M.N.; Winnett, J.A.; Nigrovic, L.E. Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network Head Injury Clinical Prediction Rules Are Reliable in Practice. Arch Dis Child 2014, 99, 427–431. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, H.; Malhotra, R.; Yadav, R.K.; Griwan, M.S.; Paliwal, P.K.; Aggarwal, A.D. Diagnostic Utility of Conventional Radiography in Head Injury. J Clin Diagn Res 2015, 9, TC13–TC15. [CrossRef]

- Parri, N.; Crosby, B.J.; Glass, C.; Mannelli, F.; Sforzi, I.; Schiavone, R.; Ban, K.M. Ability of Emergency Ultrasonography to Detect Pediatric Skull Fractures: A Prospective, Observational Study. J Emerg Med 2013, 44, 135–141. [CrossRef]

| Triage system | CTAS | ESI | MTS | ATS | SATS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stated objective | Provide patients with timely care | Prioritize patients by immediacy of care needs and resource | Rapidly assess a patient and assign a priority based on clinical need | Ensure patients are treated in order of clinical urgency and allocate patients to the most appropriate treatment area | Prioritize patients based on medical urgency in contexts where there is a mismatch between demand and capacity |

| Recommended time to physician contact, min | 1: immediate 2: ≤ 15 3: ≤ 30 4: ≤ 60 5: ≤ 120 |

1: immediate 2: ≤ 15 3: none 4: none 5: none |

Red: immediate Orange: ≤ 10 Yellow: ≤ 60 Green: ≤ 120 Blue: ≤ 240 |

1: immediate 2: ≤ 15 3: ≤ 30 4: ≤ 60 5: ≤ 120 |

Red: immediate Orange: ≤ 10 Yellow: ≤ 60 Green: ≤ 120 Blue: ≤ 240 |

|

Discriminators Clinical Vital signs Pain score Resource use |

Yes Yes Yes (10-point) No |

No Yes Yes (visual scale) Yes |

Yes Yes Yes (3-point) No |

Yes Yes No No |

Yes Yes Yes (4-point) No |

| Paediatrics | Separate version | Separate vital sign differentiators | Considered within algorithm | Considered within algorithm | Separate flowchart |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).