Submitted:

10 February 2023

Posted:

16 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Fresh Concrete: in general, SCMs incorporation results in improved mix rheology and consistency. The fine size of SCMs particles, mainly silica fume and fly ash, results in a larger surface area of the granular particles of the mix. Thus, high range water reducing chemicals are recommended to meet the slump requirements of the mix at low to moderate water-to-powder ratio. Fly ash and slag generally results in delayed setting which is beneficial for construction projects in hot weather. Because of the finer size of SCMs, the amount and rate of bleeding in fresh concrete is reduced. Retention of mixing water results in improved mechanical properties upon hardening.

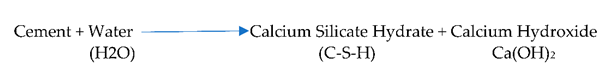

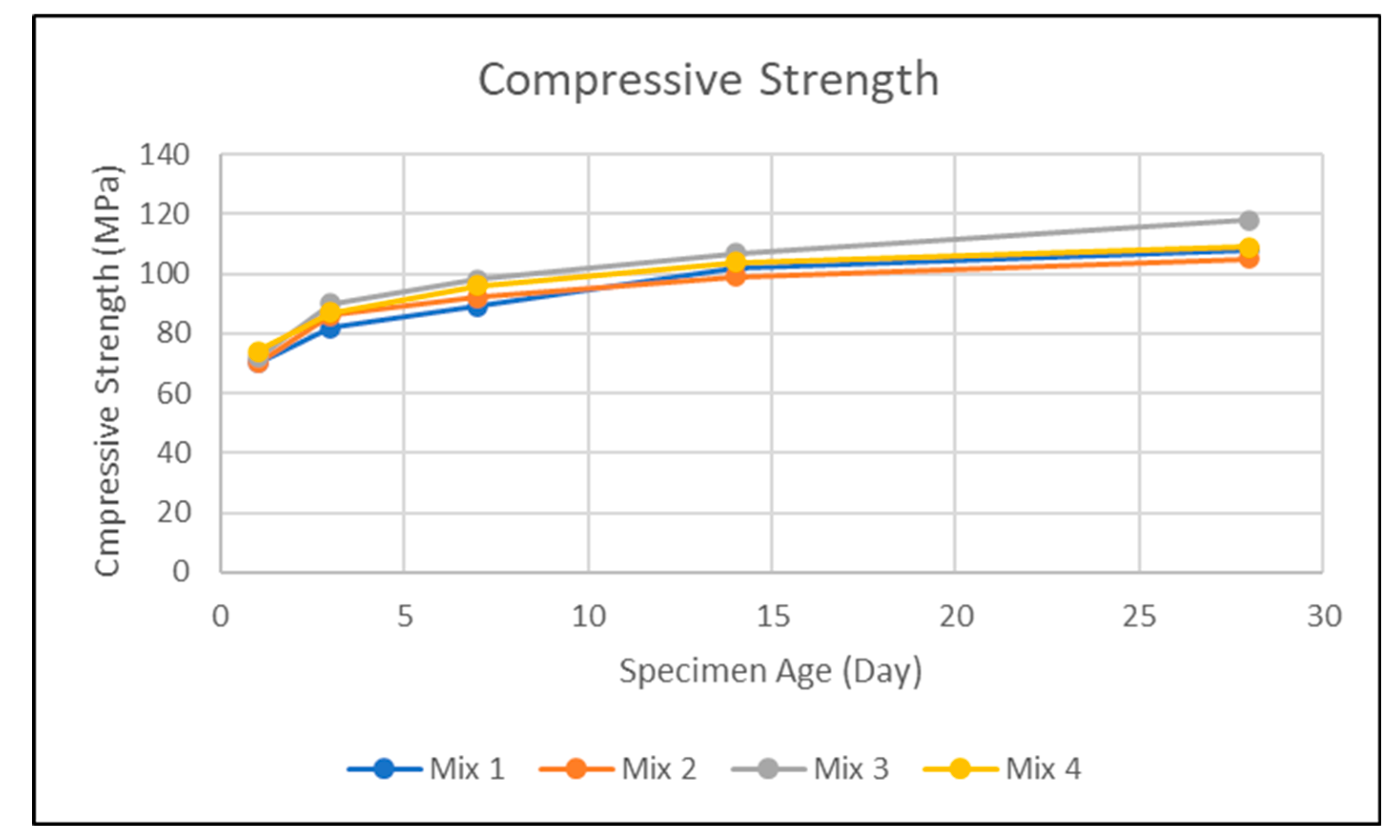

- Strength: concrete mixes are proportioned using SCMs in partial replacement of portland cement (by weight) to attain higher strength of hardened concrete [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. One type of SCM could be added to the mix to develop a “binary” concrete mix. Similarly, two types of SCMs could be added to form a “ternary” concrete mix. SCM other than silica fume, the rate of strength gain might be lower initially. However, strength gain continues for a longer period as compared to mixes with portland cement only. On the contrary, mixes with silica fume are characterized by early strength gains, and a final compressive strength in excess of 70 MPa. The overall contribution of SCMs to concrete compressive strength could be ex- plained as a two-step chemical reaction as follows:

- Durability: SCMs can be used to reduce the heat of hydration of portland cement. This is advantageous when pouring massive concrete structures. The reduced size of SCMs reduces the hardened concrete voids ratio and permeability. Reduced permeability results in improved long-term performance, less susceptibility to alkali-silica reactivity [13,14,15], and higher resistance to chloride attacks. The improved long-term performance of concrete structures incorporating SCMs results in a lower need to project maintenance and/or replacement. Increased strength and durability are extremely beneficial to precast/prestressed concrete industry applications. The main objective of this research is to develop economic non-proprietary high strength concrete mixes using SCMs widely available in the construction market through a two-phase research project. Phase I: a literature review to present the physical and mechanical properties of SCMs with large construction market share, namely silica fume and fly ash, and phase II: presents the experimental investigations to develop high strength “ternary” concrete mixes using SCMs. Mechanical properties of developed mixes including compressive strength, modulus of elasticity, and modulus of ruptures are tested to validate the superior mix characteristics.

2. Physical and Chemical Properties of Supplementary Cementitious Materials

3. High Strength Ternary Concrete Mix Design Criteria

- Early high strength: in excess of 70 MPa (10,000 psi) at 24-hrs for successful strands release at early age. This is required to increase the precast facility productivity

- High compressive strength: at 28-day to increase the precast girder capacity, and for possible construction of slender girders with large span-to-depth ratio. A minimum 28-day compressive strength of 100 MPa (14,250 psi) is specified

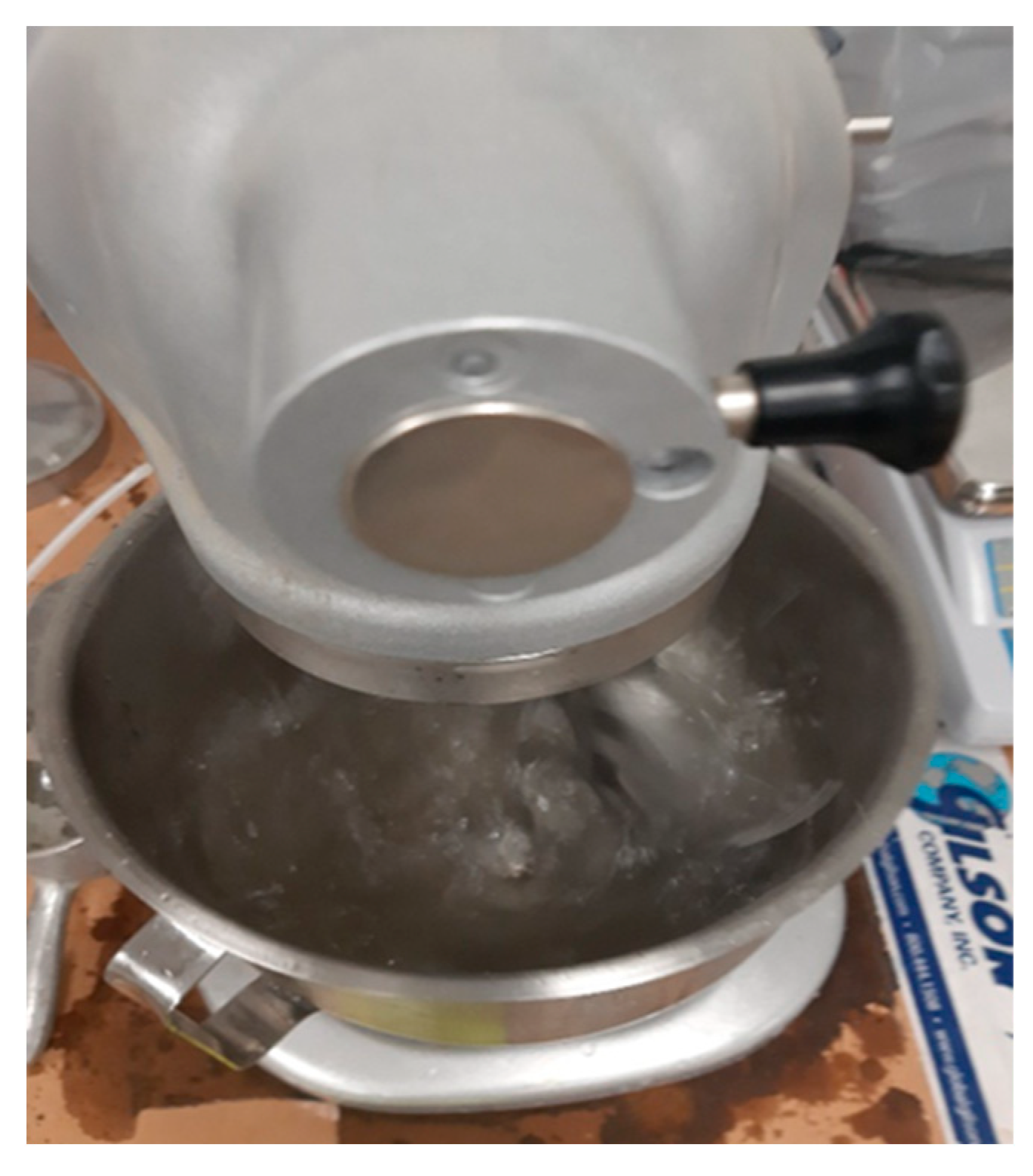

- Self-compacting concrete: flowing ability with a minimum spread diameter of 62.5 cm. (25 in.) to successfully precast heavily reinforced girders without honeycomb development.

- Maximum mixing time: does not exceed 20 minutes to allow for the continuous pour of precast members without the formation of cold joints.

- Maximum cementitious materials content (Cement + silica fume + fly ash) does not exceed 950 kg. per cubic meter of concrete

- Maximum SCMs replacement does not exceed 30% of the total cementitious materials content

- Water to cementitious materials ratio does not exceed 20% to attain high strength

- HRWR quantity is adjusted to attain the specified spread diameter. Thus, a high energy paddle mixer is used in mix development, as shown in Figure 1.

- Trail concrete batches were made to optimize mixing criteria and for possible production of HSC in 20-minute maximum mixing duration. The following presents the mixing procedures concluded for this experimental research program:

- Granular materials including portland cement, SCMs, and aggregates are preblended for a total duration of 2 min. Dry mixing is required to enhance the mix packing order and minimize the voids ratio for hardened concrete

- Mixing water, infused with HRWR, is added to the preblended granular materials. Wet mixing continues for a maximum duration of 18 min. Developed mix spread diameter is measured. A minimum spread diameter of 62.5 cm. (25 in.) is required for successful mix development, as shown in Figure 2.

4. Experimental Investigation, Mix Trials, and Final Mix(es) Selection

- Testing results of high strength mixes initial trials shown in Table 4 are classified into three different categories:

- Category 1: including mixes 1 through 4, where duration time was lesser than or equal 20 minutes, spread diameter greater than or equal 67 cm, and initial compressive strength (24-hour) of 70 MPa was attained. According to predetermined criteria, mixes 1 through 4 were approved for further investigation including additional mechanical properties testing.

- Category 2: including mixes 4 through 7, where flowing ability required was not acceptable due to spread diameter less than 62.5 cm recorded. Lack of flowing ability may result in potential voids and honeycombs problems when bridge girders with high percentage of reinforcement are prefabricated. Thus, mixes 4 through 7 were rejected due to low flowing ability.

- Category 3: including mixes 8 through 11, where initial compressive strength recorded at 24-hour of age was less than 70 MPa. High initial compressive strength are required to allow for the removal of forms and cutting prestressing strands. Thus, mixes 8 through 11 are rejected due to their inability to meet the predetermined initial compressive strength [30,31,32].

5. Mechanical Properties Investigation

5.1. Compressive Strength

5.2. Modulus of Elasticity

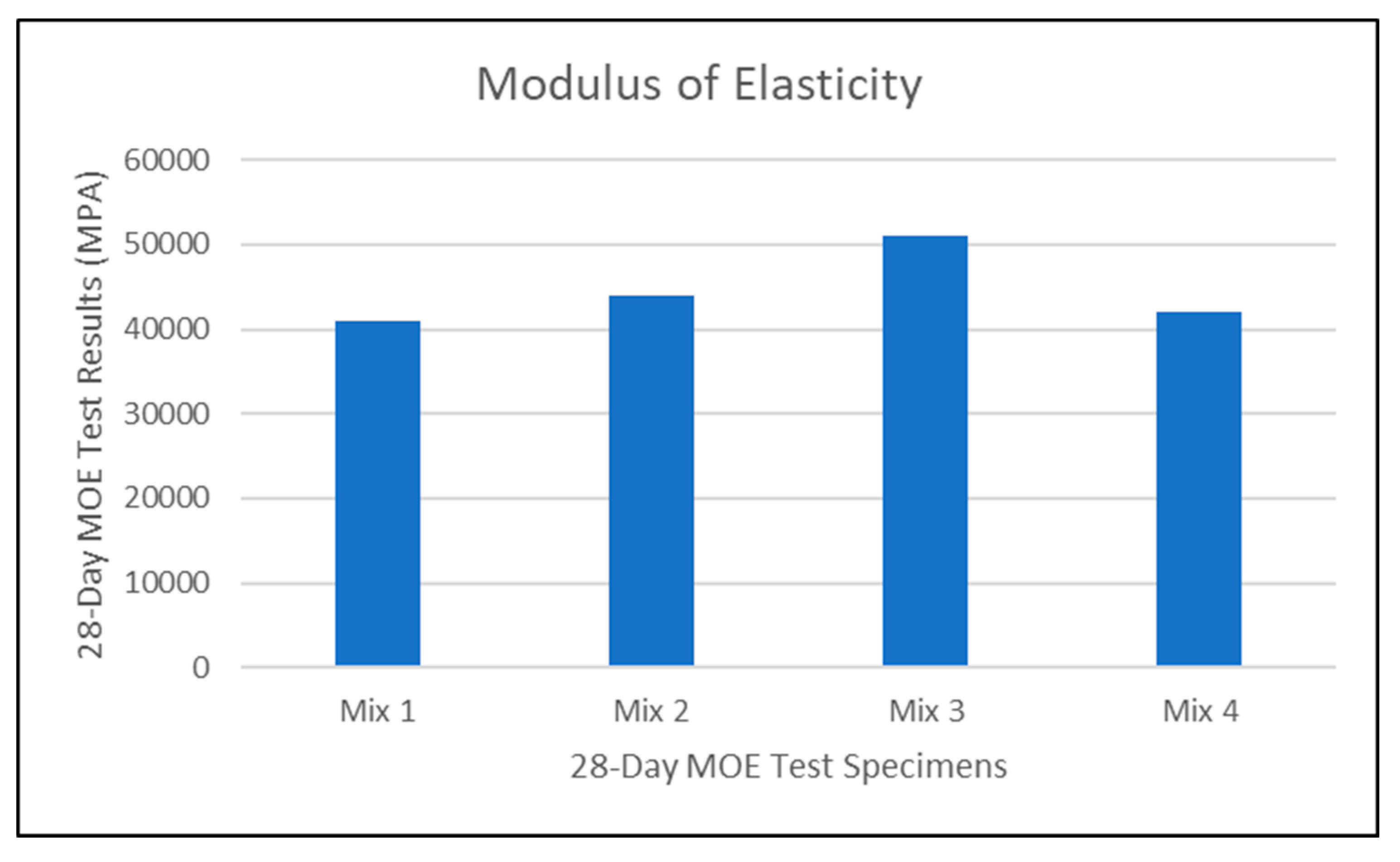

- MoE test results for developed mixes, as shown in Figure 5, are significantly higher than the average MoE mixes for normal strength concrete. In this experimental investigation, the MoE values ranged from a minimum of 41 GPa to 51 GPa, as compared to a MoE of 25 to 30 GPa for regular strength concrete mixes. This MoE increase is attributed to the substantial increase in mix strengths due to SCMs incorporation.

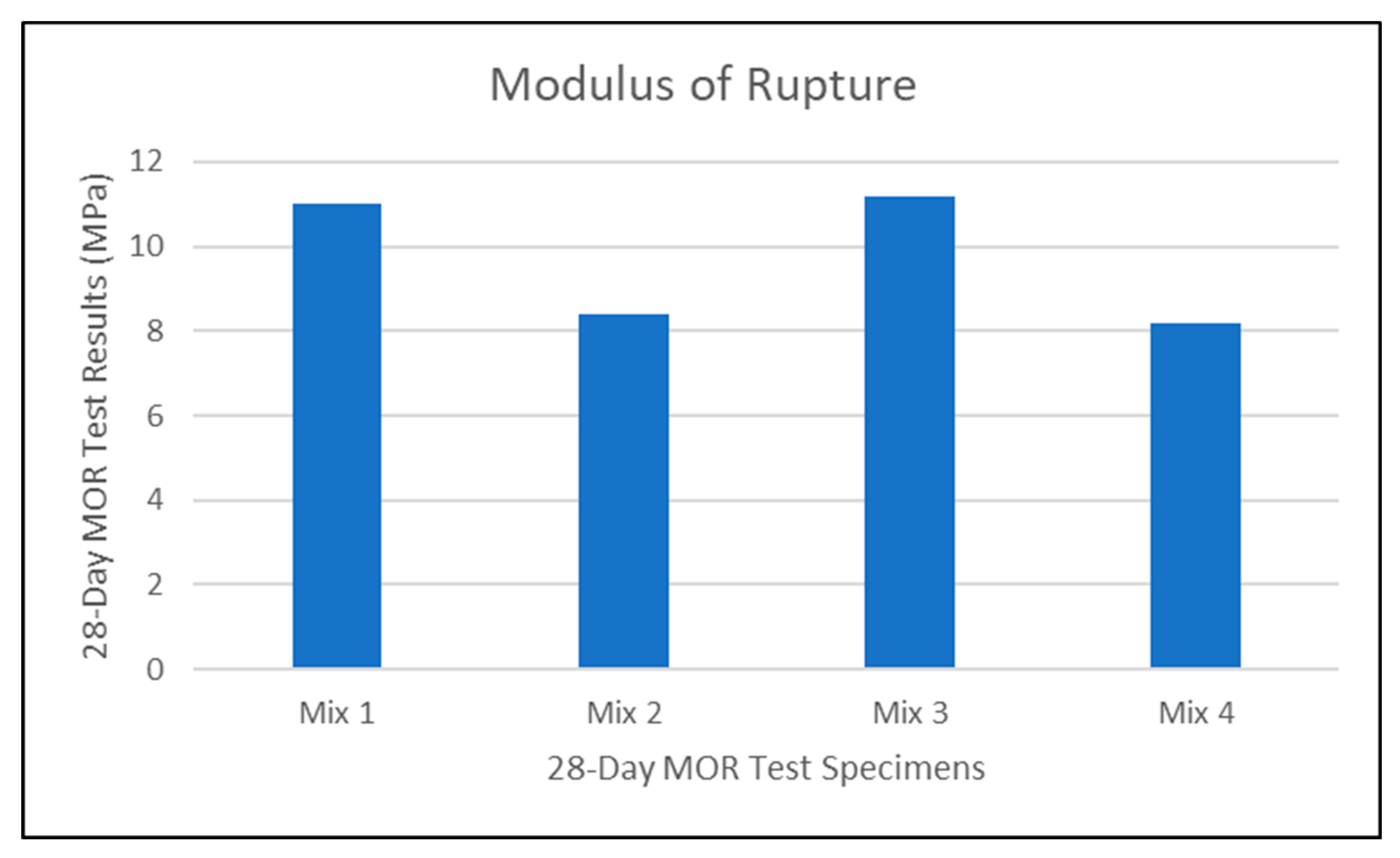

5.3. Modulus of Rupture

6. Summary and Conclusions

7. Future Research

Acknowledgements

References

- Akhnoukh, A.K. The use of micro-and nano-sized particles in increasing concrete durability. Particulate Science and Technology, Vol. 38, No. 5, 2019, pp. 529-534. [CrossRef]

- Akhnoukh, A.K. Implementation of nanotechnology in improving the environmental compliance of construction projects in the USA. Particulate Science and Technology, Vol. 36, No. 3, 2018, pp. 357-361. [CrossRef]

- Elia, H.N., Ghosh, A., Akhnoukh, A.K., and Nima, Z.A. Using nano- and micro-titanium dioxide (TiO2) in concrete to reduce air pollution. Journal of Nanomedicine and Nanotechnology, Vol. 9, No. 3, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Akhnoukh, A.K., and Elia, H.N. Developing high performance concrete for precast/prestressed concrete industry. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 11, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Akhnoukh, A.K. Accelerated bridge construction projects using high performance concrete. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Graybeal, BA. Design and construction of field-cast UHPC connections. FHWA-HRT-14-084. 2014.

- Koh, K.T., Park, S.H., Ryu, G.S., An, G.H., and Kim, B.S. Effect of the type of silica fume and filler on mechanical properties of ultra-high-performance concrete. Key Eng. Mater. Vol. 774, 2018, pp. 349-354. [CrossRef]

- Akhnoukh, A.K., and Buckhalter, C. Ultra-high-performance concrete: constituents, mechanical properties, applications, and current challenges. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 15, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Akhnoukh, A.K. Development of high-performance precast/prestressed bridge girders. A Dissertation. University of Nebraska-Lincoln, USA, 2008.

- Joe, C.D., Moustafa, M.A., Ryan, K.L. Cost and ecological feasibility of using UHPC in highway bridge. Report No. 803, Nevada Department of Transportation (NDOT), 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J. Development of cost-effective ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) for Colorado sustainable infrastructure, Report No.CDOT-2018-15, 2018.

- Akhnoukh, A.K., and Soares, R. Reactive powder concrete application in the construction industry in the United States. Proceedings of the 10th Conference of Construction in the 21st Century (CITC-10), Sri Lanka, 2018.

- Akhnoukh, A.K., Kamel, L.Z., and Barsoum, M.M. Alkali-silica reaction mitigation and prevention measures for Arkansas local aggregates. World Academy of Science, Engineering, and Technology International Journal of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Abd Elssamd, A., and Ma, J.Z. Alkali silica reactivity (ASR) risk assessment and mitigation in Tennessee. Research Report, University of Tennessee at Knoxville, Report No. RES2016-03, 2021.

- Akhnoukh, A.K., and Mallu, A. R. Detection of alkali-silica reactivity using field exposure site investigation. Proceedings of the 58th Annual Associated Schools of Construction International Conference, Vol. 3, pp. 74-81, 2022. [CrossRef]

- 16. ASTM International. Standard specification for coal fly ash and raw calcined natural pozzolan for use in concrete. ASTM C618-19, 2019. [CrossRef]

- American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Standard specification for coal fly ash and raw or calcined natural pozzolan for use in concrete. AASHTO M 295, 2021.

- Pandian, N.S., Rajasekhar, C., Sridharan, A. Studies of the specific gravity of come Indian coal ashes. Journal of Testing and Evaluation, Vol. 26, No. 3, 1998 pp. 177-186. [CrossRef]

- STM International. Standard test methods for sampling and testing fly ash or natural pozzolans for use in portland-cement concrete. ASTM C311, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Amran, M, Debbarma, S., and Ozbakkaloglu, T. Fly ash-based eco-friendly geopolymer concrete: A critical review of the long-term durability properties. Construction and Building Materials. Vol. 270, No. 8, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gollakota, A.R.K., Volli, V., Shu, C.M. Progressive utilization prospects of coal fly ash: a review. Sci tot. Environ., 2019. [CrossRef]

- Amin, M., and Abdelsalam, B.A. Efficiency of rice husk ash and fly ash as reactivity materials in sustainable concrete. Sust. Env. Research, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Amran, Y.H.M., Alyousef, R., Alabduljabbar, H., and El-Zeadani, M. Clean production and properties of geopolymer concrete; a review. J. of clean prod/, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L., Alkali-activated materials. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 114, pp. 40-48, 2018. [CrossRef]

- ASTM International. Standard specification for silica fume used in cementitious materials. ASTM C1240-20, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Akhnoukh, A. Overview of nanotechnology applications in construction industry in the United States. Journal of Micro and Nano-systems, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2013.

- Panjehpour, M., Ali, A.A.A., Demirboga, R. A review for characterization of silica fume and its effects on concrete properties. International Journal of Sustainable Construction Engineering and Technology, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2011.

- Sahoo, K.K., Sarkar, P., and Davis, R. Mechanical properties of silica fume concrete designed as per construction practice. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Construction Materials, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Bubshait, A.A., Tahir, B.M., and Jannadi, M.O. Use of micro silica in concrete construction. Journal of Building Research and Information, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 41-49, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Akhnoukh, A. Prestressed concrete bridge girders using 0.7 in. strands. International Journal of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Vol. 7, No. 8, pp. 613-617, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Akhnoukh, A. Application of large prestress strands in precast/prestressed concrete bridges, Civil Engineering Journal, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 130-141. [CrossRef]

- Akhnoukh, A., and Ekhande, T. Supplementary cementitious materials in concrete industry – A new horizon, Proceedings of the 18th International Road Federation World Meeting and Exhibition, Dubai, 2021.

- ASTM International. Standard test method for compressive strength of cylindrical concrete specimens. ASTM C39/C39M-21, 2021. [CrossRef]

- STM International. Standard test method for static modulus of elasticity and Poisson’s ratio of concrete in compression. ASTM C469/C469M-14, 2021. [CrossRef]

- ASTM International. Standard test method for flexural strength of concrete (using simple beam with third-point loading). ASTM C78/C78M-22, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Akhnoukh, A.K. The effect of confinement on transfer and development length of 0.7-inch prestressing strands. 2010 Concrete Bridge Conference: Achieving Safe, Smart, and Sustainable Bridges, Phoenix, AZ, 2010.

- Morcous, G, and Akhnoukh, A.K. Reliability analysis of NU girders designed using AASHTO LRFD. Structures Congress 2007, Long Beach, California, 2007 . [CrossRef]

- Edmunson, J., Fiske, M.R., Mueller, R.P., Alkhateb, H.S., Akhnoukh, A.K., Morris, H.C., Townsend, I.I., Fikes, J.C., and Johnston, M.M. Additive construction with mobile emplacement: multifaceted planetary construction materials development. 16th Biennial International Conference on Engineering, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Akhnoukh, A.K. Advantages of contour crafting in construction applications. Journal of Recent Patent on Engineering, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 294-300, 2021. [CrossRef]

| Component | Bituminous | Subbituminous | Lignite |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 20-60 | 40-60 | 15-45 |

| Al2O3 | 5-35 | 20-30 | 10-25 |

| Fe2O3 | 10-40 | 4-10 | 4-15 |

| CaO | 1-12 | 5-30 | 15-40 |

| MgO | 0-5 | 1-6 | 3-10 |

| SO3 | 0-4 | 0-2 | 0-10 |

| Na2O | 0-4 | 0-2 | 0-6 |

| K2O | 0-3 | 0-4 | 0-4 |

| LOI | 0-15 | 0-3 | 0-5 |

| Percentage | Class F | Class C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Requirements | SiO2+Al2O3+Fe2O3 | Min % | 70 | 50 |

| SiO3 | Max % | 5 | 5 | |

| Moisture Content | Max % | 3 | 3 | |

| Loss on Ignition | Max % | 5 | 5 | |

| Optional Chemical Requirement | Available alkalis | Max % | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Physical Requirements | Fineness (+325 Mesh) | Max % | 34 | 34 |

| Pozzolanic Activity/Cement (7 days) | Min % | 75 | 75 | |

| Water requirement | Max % | 105 | 105 | |

| Autoclave expansion | Max % | 0.8 | 0.8 | |

| Optional Physical Requirements | Multiple factor (LOI x fineness) | 255 | - | |

| Increase in drying shrinkage | Max % | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| Uniformity requirement (air entraining agent) | Max % | 20 | 20 |

| Percentage | Silica Fume | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Requirements | SiO2 | Min % | 85 |

| Moisture content | Max % | 3 | |

| Loss on ignition | Max % | 6 | |

| Physical Requirements | Percent retained on No. 325 | Max % | 10 |

| Accelerated pozzolanic strength activity index | Min % percent of control | 105 | |

| Specific surface | Min (m2/g) | 15 | |

| Optional Physical Requirements | Reactivity with concrete alkalis, reduction of mortar expansion at 14 days | Min % | 80 |

| Sulfate resistance expansion, moderate resistance (6 month) | Max % | 0.1 | |

| Sulfate resistance expansion, high resistance (6 month) | Max % | 0.05 | |

| Sulfate resistance expansion, very high resistance (1 year) | Max % | 0.05 |

| Mix # | Cem. Mat. | W/CM | Mixing Duration | Flowing Ability | Early Strength | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mix 1 | 900 | 0.17 | 20 min. | 67 cm. | 70 MPa | Mix Accepted |

| Mix 2 | 900 | 0.18 | 18 min. | 68 cm. | 70 MPa | |

| Mix 3 | 900 | 0.19 | 18 min. | 68 cm. | 72 MPa | |

| Mix 4 | 900 | 0.18 | 18 min. | 67 cm. | 74 MPa | |

| Mix 5 | 850 | 0.19 | 18 min. | 60 cm. | Low Flowing Ability (Rejected) |

|

| Mix 6 | 825 | 0.19 | 18 min. | 59 cm. | ||

| Mix 7 | 800 | 0.22 | 18 min. | 59 cm. | ||

| Mix 8 | 770 | 0.24 | 17 min. | 71 cm. | Low Initial Strength (Rejected) |

|

| Mix 9 | 770 | 0.24 | 17 min. | 70 cm. | ||

| Mix 10 | 770 | 0.24 | 17 min. | 69 cm. | ||

| Mix 11 | 770 | 0.24 | 17 min. | 70 cm. |

| Cement | SF | Fly Ash | Total CM | SCM/Cement | Sand | LS | Water | HRWR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mix 1 | 630 | 90 | 180 | 900 | 0.3 | 1350 | 0 | 135 | 35 |

| Mix 2 | 630 | 90 | 180 | 900 | 0.3 | 950 | 400 | 145 | 35 |

| Mix 3 | 630 | 135 | 135 | 900 | 0.3 | 1350 | 0 | 145 | 40 |

| Mix 4 | 630 | 90 | 180 | 900 | 0.3 | 950 | 400 | 140 | 40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).