1. Introduction

A large body of research has identified that a small proportion of the population often accounts for a disproportionately larger proportion of public health system resources [

1,

2,

3]. Much of this usage is related to systemic, inequitable access and disproportionate health burdens faced by these individuals [

2]. While high-resource use impacts the wellbeing of high-resource users, it also depletes scarce health care resources and mounts health service expenditures [

1]. Thus, addressing the unmet needs of high-resource users is integral in ameliorating the efficacy of health care systems [

3].

Within the literature, this broad group of health system users is identified by variety of definitions and constructs, and include high-cost, high-frequency, repeat, or high-resource users [

4,

5]. Research has included examination of unplanned hospitalizations, emergency department visits, or physician usage, includes a range of conditions, and encompasses individuals across the life-course. Despite the many definitions, these studies are similar in their focus on those individuals who use greater than expected proportions of often-limited health system resources [

4].

Broadly, high-resource users are categorized in the literature as older aged adults from lower income quintiles with poorer self-reported health, often presenting with multiple chronic conditions and reduced access to primary health care [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Other social determinants of health have also been related to high-resource users, including unemployment, limited social support, rates of chronic illness, and rates of serious psychological illness and addiction [

2,

6]. Additionally, geographic differences have been identified, with certain areas demonstrating higher rates of high-resource users than others [

5]. These factors, as well as other social determinants of health often underpin or exacerbate frequent use, largely due to increased rates of unmet health needs, poorly managed chronic diseases, and comorbid conditions [

6,

7,

8]. Characteristics associated with high-resource users tend to differ depending upon the focus of the study, often fluctuating depending upon distinct regions, services, or populations [

2]. These findings indicate that an interplay of individual-level, community-level, and geographic factors contribute to differential rates of health-seeking behaviour [

7].

Rural and remote communities demonstrate persistent health inequities in comparison to their urban counterparts, largely due to geographic and structural inequities [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Individuals living remotely often report burdensome travel times and associated time and cost expenditure as drawbacks to accessing health care [

11]. Common challenges faced by rural and remote communities– notably a transient workforce, fragmentation of service providers, and resource shortages – compound geographic barriers in health care access. Community-level difficulty in recruiting and retaining physicians also reduces service access, as limited available local services impede early identification and treatment of health concerns [

7].

Despite structural barriers in health care, very few studies explicitly focus on high-resource users between and within rural regions, and no systematic or scoping review has been done for this population. With an overwhelming majority of urban-centric studies, gaps in rural-focused research limit our understanding of factors that impact a community’s and/or an individual’s vulnerability of being (or becoming) a high-resource health care user in rural communities.

Although rural areas are highly heterogeneous, rurality is often considered as a singular factor when considering social determinants of health [

12]. To account for the heterogeneity of rural communities, we must better understand the determinants within and between rural areas [

13]. The challenges faced in determining characteristics of high-resource users in rural communities are compounded by a lack of solidarity in the definitions of

rural and

high-resource. Such heterogeneity creates barriers in understanding and categorizing users that place a disproportionate burden on the health care system.

1.1. Objectives

As illustrated, there is no universal understanding of the individual factors that are associated with high-resource users in rural regions, and how these factors interact with. This scoping review aims to address this gap by gathering information of the individual factors that contribute to high resource healthcare service use in the lens of the individual’s residential rurality, to better inform future research and interventions aiming to address high-resource users in the health care system.

An additional objective of this research is to inform planners and practitioners in countries with public health systems and large rural and remote populations. While several countries could be included, our focus is on Australia and Canada, two similar countries with geographically vast rural landscapes, similar issues in rural health service provision, and long traditions of rural health research.

2. Materials and Methods

A structured scoping review was undertaken to identify and to analyze characteristics of high-resource health care users in rural Canadian communities. The objective of this review was two-fold: (1) to examine characteristics of high-resource users between and within rural communities in Canada through a rural-centered lens, and (2) to identify gaps in current research regarding the effect of rurality on being (or becoming) a high-resource user.

This review was guided by the work of Arksey and O’Malley [

14] and followed PRISMA-ScR guidelines on scoping reviews [

15]. Following the review, a thematic analysis was undertaken to synthesize the literature and identify key themes. Findings were then collated, summarized, and reported.

2.1. Key Terms

The term high-resource user encompasses several terminologies and categorizations that describe the population use a disproportionately higher than expected level of health care services. Common definitions include high-cost, high-frequency, and repeat users, along with categorizations such as avoidable hospitalizations, less-urgent hospital presentations, and cumulative risk of readmission. For the remainder of this paper, the term high resource will be used to denote all users that would fall into any of these categories.

Researchers categorize rurality using different definitions and indexes, depending upon geographical location, region, or focus. For this paper, the terms rural will be used to denote populations or health care regions that are categorized as such by researchers, regardless of the parameters of their definition. The working definitions included in the review will be provided and analyzed.

For this paper, term Aboriginal will be used as a general term inclusive of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people of Canada, in addition to Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islanders of Australia.

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

First, a search for rural high-resource users was conducted. The search string was used in PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus. Publications were limited to Australia and Canada, as these countries have similar health infrastructure and demonstrate similar geographical disparities in health. Only studies published between 2000–2022 in English were included. Second, two researchers conducted a title screening process in the three databases. Exclusion criteria included criteria previously established, in addition to the exclusion of titles that were not relevant in the Australian or Canadian contexts and/or did not focus on characteristics of high-resource users. Results were then pooled, and duplicates were removed. Third, three researchers conducted an abstract review. In addition to the previously established exclusion criteria, titles were excluded if the study focused on a single disease, did not include a rural analysis, did not pertain to high-resource users, and/or did not take place in Australia or Canada. Fourth, the authors conducted a full-text review with the same inclusion criteria as the title and abstract reviews.

2.3. Classification of Data

Thematic coding was conducted in a shared database to compile and to organize the data. Studies were first categorized based upon year of publication, geographic location, target population, study methodology, sample size, study objectives/results, degree of remoteness, and inclusion or exclusion of Aboriginal populations. Articles were then coded thematically to identify the key characteristics of high-resource users. The primary themes were extracted and organized based upon individual- and community-level factors. Theme headings for individual-level factors included age, sex, socioeconomic status, risk behaviours, Indigenous status, and presence or absence of primary care providers. Other factors identified in the literature were noted in the “other” category and included in discussion. Community-level themes included degree of rurality and degree of access to health care.

2.4. Strength of Evidence

We included a strength of evidence framework that was guided by and adapted from the hierarchy of research designs and evidence. Papers were evaluated based upon their strength of design, including generalizability and depth of analysis. Reviewers also categorized papers depending upon their consideration of social inequities. These included gender-based factors and inclusion of at-risk populations.

3. Results

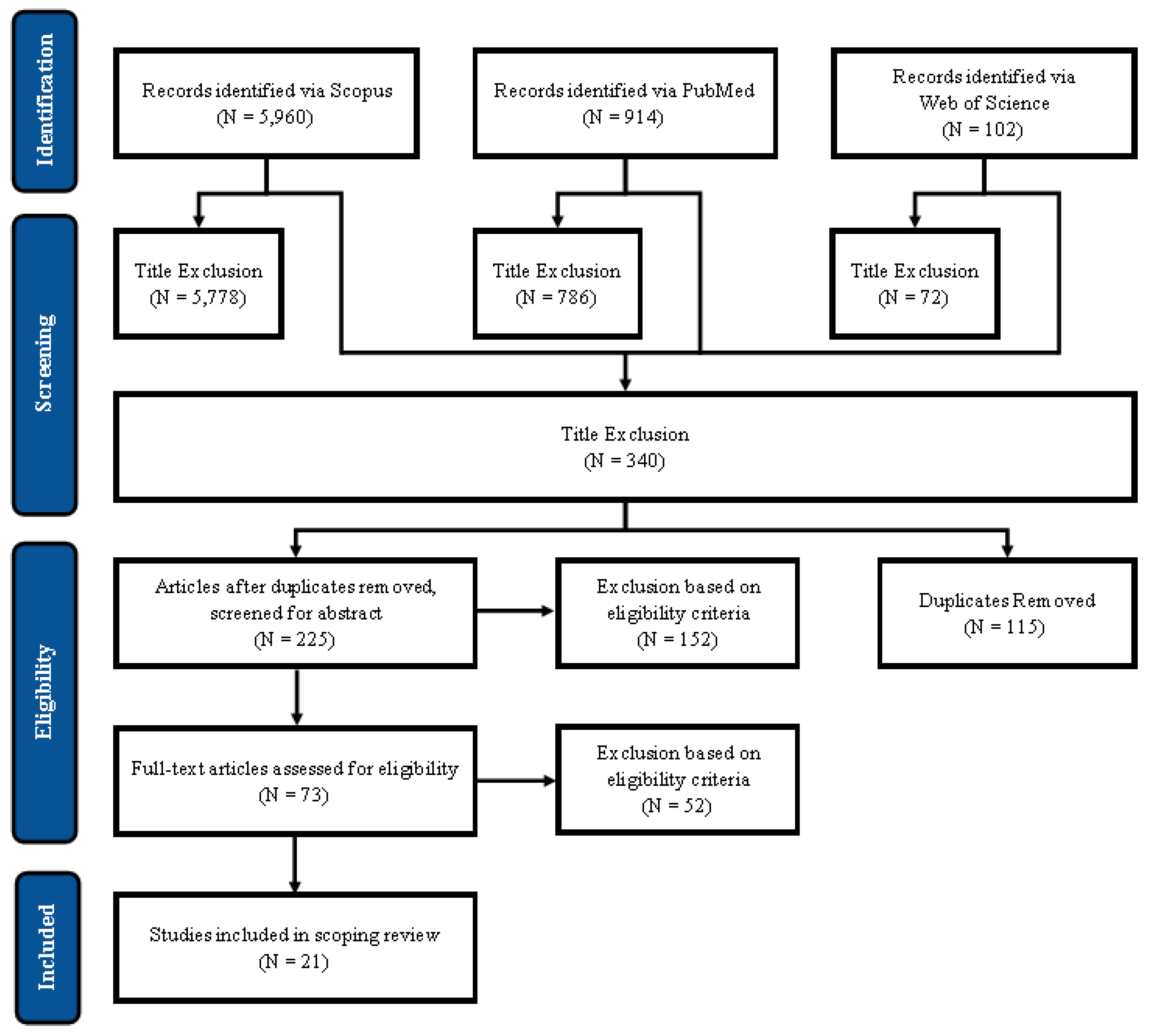

The primary search produced 5960 results in Scopus, 914 results in PubMed, and 102 results in Web of Science, as shown in

Figure 1. Titles were reviewed and assessed for eligibility based on their relevance to individual- and geographic-level characteristics of high-frequency health users, in accordance with inclusion criteria. The title screening produced 182 results in Scopus, 128 results in PubMed, and 30 results in Web of Science. The results from the three databases were then pooled and duplicates were removed, which produced 225 total results. The results were compared and agreed upon by two researchers at each stage of the review. Following the abstract review, 73 articles were deemed eligible, and 52 articles were excluded. Following the full-text review, 21 articles remained.

3.1. Individual-Level Characteristics

3.1.1. Older Age

Almost half of the studies included in the review identified older age as a risk factor for high-resource use of health care services. Older age was associated with greater ICU and hospital admittance [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]; longer hospital stays [

17,

22,

23,

24]; and higher usage of primary care [

17,

22,

25] and specialist services [

17]. Additionally, those aged 65 years and older accounted for more than 50% of high-resource users in remote Australia [

26] and for more than 50% of high-resource users of general health services in Ontario, Canada [

27].

3.1.2. Sex

Thirteen of the included studies (62%) reported sex as a predictor of high-resource use. Of these, seven studies found females were higher resource users than males and six found that sex-based differences were dependent upon other factors. Females were identified as higher resource users in multiple health care settings, including health services for all ages [

16,

17,

21,

22,

28], health services for youth [

29,

30], primary care for all ages, and adult emergency department presentations [

21,

31].

Penning (2016) found sex-based differences were depending upon which health service was being accessed [

17]. In a Canadian cohort aged 50 years and older, females were more likely to draw on primary care and specialist services, whereas males were more likely to be hospitalized [

17]. Different trends were identified when researchers examined usage within specific services. Of people who accessed primary care services at least once, females made more visits; however, of those who accessed specialist services or were hospitalized, males made more specialist visits and had higher hospitalization rates. Women also had longer hospitalizations [

17,

20,

23,

32].

Manos (2014) examined sex-based different in a population aged 12–24 years old in Nova Scotia, Canada. Females accounted for 2X more primary care and inpatient contacts and made up 84% of all high-resource users [

29].

3.1.3. Comorbidities

Fourteen papers identified health status as a determinant of high-resource service use; all these concluded that high-resource users are more likely to have higher comorbidity burdens. Three studies used comorbidity scores or indices—ie. the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)—to determine the burden of comorbidities [

16,

17,

21,

22,

28,

32]. Patients with higher scores on the comorbidity indices were more likely to be hospitalized [

28] and to see primary care and specialist visits [

17]. One study found that a higher comorbidity score (CCI) nearly quadrupled the odds of having 4 or more admissions and that a decrease in wellness score increased risk of frequent admittance by 53% [

27].

Studies also identified significant comorbidity burdens within their respective high-resource cohorts. Guilcher (2016) found that 58.5% of high-resource users presented with 8 or more distinct comorbid conditions, while less than 1% of the cohort had no pre-existing condition [

27]. Garne (2009) identified 3 or more primary care diagnoses among almost 50% of high-resource patients [

26], while Quilty (2019) determined 47% of the high-resource cohort presented with 3 or more comorbid conditions [

33].

Two studies associated condition severity with high-resource presentations, with contradictory findings. One study indicated that higher severity correlated with higher resource use [

19], whereas the other found that most frequent user presentations were benign [

34]. Albeit benign presentations, the high-resource users still frequently required admission [

34]. High-resource users were also found to have lower self-rated health compared to the general population [

23].

3.1.4. Socioeconomic Status

Two studies identified social and material deprivation as risk factors for high-resource use within an elderly cohort [

17,

29]. Social isolation and psychological distress were common in high-resource users, as a significant proportion lived alone and had lower social network scores [

23]. The proportion of high-resource users that lived alone was significantly higher than the general population, at a rate of 34% compared to 25% [

23,

32]. 22% who reported needing help to care of themselves did not have a close friend or relative that could regularly care for them [

23].

Nine of the included studies identified measures of socioeconomic status as important characteristics of high-resource use. Of these, 7 studies identified low socioeconomic status as a characteristic of high-resource use [

20,

21,

23,

28,

29,

30,

31], whereas two studies determined that differences depended upon the health service being accessed [

17,

20].

Wallar (2020) found that lower income was one of the largest risk factors for high-resource use for both males and females [

20]. Nearly one quarter of participants in the analysis conducted by Longman (2012) reported difficulty affording their medications; one third of participants were using 5 or more medications at the time. Further, 53% of respondents had an income of less than

$20,000 per year, and the majority were on a pension [

23].

Two studies determined that the influence of high- versus low-income [

17] or high- versus low-socioeconomic status [

29] varied according to the health service accessed. Overall, Penning (2016) determined that lower to middle income groups were significantly less likely to access primary care and specialist services compared to the highest income group [

17]. However, among those who accessed primary care services at least once, those with lower income demonstrated a greater increase in use over time [

17]. Additionally, among those that were hospitalized during the study period, the two lowest income quintiles had significantly higher hospitalization rates compared to the highest quintile [

17].

Manos (2014) also found differences in rates of SES-based presentations depending upon other factors [

29]. While those with lower SES had significantly fewer visits to primary care physicians, they demonstrated a higher number of inpatient, emergency department, and outpatient specialist visits in comparison to those with higher SES [

29]. This discrepancy was most notable in youth outpatient specialist visits, where youth in the lowest SES accounted for more than 3X the number of visits than those in the highest SES quartile [

29].

3.1.5. Risk Behaviours

Risk behaviours, including smoking and excessive alcohol consumption, were identified as predictors of high-resource use in ten of the included studies [

16,

18,

20,

22,

28,

31,

32,

33,

35,

36]. Ten studies identified excessive alcohol consumption and five studies identified smoking. One study found heavy smoking was one of the largest risk factors regardless of sex [

20] and another found alcohol was the largest risk factor [

18]. Springer (2017) found that the odds of being a frequent user were higher among those with a single alcohol-related condition; individuals with two or more alcohol-related hospital episodes had a higher risk of being a frequent user for more than one year.

3.1.6. Aboriginal Populations

Of the 21 papers included in the review, 7 included Aboriginal populations [

18,

20,

26,

28,

33,

34,

36]. Of these, five studies identified increased risk of high health care use in Aboriginal populations. The remaining two papers did not discuss differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal presentations. Springer (2017) found that Aboriginal patients were twice as likely to be frequent users (21.7%) in comparison to non-Aboriginal patients (10%); the two groups also had different clinical presentations. Risk of prolonged high-resource use was elevated for Aboriginal patients [

18], as was risk of hospitalization [

28].

Quilty (2019) identified a strong association between Aboriginal status and homelessness [

33]. Most Aboriginal people included in the study who were on dialysis were homeless [

33]. This impeded access to baseline requirements when undergoing dialysis, including food, transport, and a safe, clean home [

33]. Quilty (2019) also determined an underdiagnosis and/or under recognition of health concerns among Aboriginal patients. The high trauma exposure faced by Aboriginal populations would be indicative of mental health challenges; however, mental health concerns were not apparent in the communities under study [

33].

Springer (2017) identified that risk flags for alcohol-related and mental health conditions were much more common in Aboriginal frequent users compared to non-Aboriginal frequent users. Among Aboriginal patients with two or more years of frequent user status, rates of alcohol-related condition risk flags were over 3 times that of non-Aboriginal frequent users. Rates of risk flags for mental health conditions were 1.5–2 times more prevalent for Aboriginal compared to non-Aboriginal frequent users.

3.1.7. Other Factors

Other factors were identified as predictors of high-resource use, including being unmarried or widowed [

19,

20], homeless [

29,

35], physically inactive [

20], food insecure [

33], and underweight [

19]. Wallar (2020) found that being underweight was one of the largest risk factors for high-resource use [

20]. High-resource users were also more likely to be infrequent or non-users of clinics, indicating unmet primary health needs [

26].

3.2. Geographic Factors

3.2.1. Rural Definitions

All the papers included in this review discussed geographic indicators of high-resource use, per inclusion criteria. Of these, 11 papers found that rural patients were more likely to be high-resource users, 2 found service use depended upon which service was being accessed, and 1 paper reported urban patients accounted for more high-resource users. The remaining 7 papers only analyzed rural populations and therefore did not provide a rural/urban comparison.

Ten studies used various indices to classify rurality. Three used the Accessibility Remoteness Index of Australia [

24,

28,

35], one used the Victorian health service regions [

28], one used the Rurality Index of Ontario [

27], two used the Statistics Canada Rurality Index, through the Canadian Community Health Survey [

17,

20]. The indicators used, their definitions, and the articles that used them have been provided in

Table 1. Dufour (2020) and Chiu (2022) used a self-generated (not referenced) categorization based upon area populations: metropolitan area ≥100,000 inhabitants; small town: 10,000–100,000 inhabitants; and rural: <10,000 inhabitants.

The remaining 11 studies did not specify how rurality was classified. Seven studies demarked rurality as a dichotomous variable (rural or urban); four classified based upon home postal code [

20,

21,

22,

32], while the other three did not indicate categorization method [

18,

30]. Four studies did not provide definitions of rural versus urban, but all took place in preestablished rural regions [

25,

26,

33,

34]. Two studies did not specify rural definitions [

23,

36].

3.2.2. Health Service Use

Rural patients placed a larger burden in terms of rates for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions (ACSC) [

16,

20,

35] and general emergency department attendance [

21,

22,

25,

30,

32,

33] compared to urban centres. Quilty (2019) found that 85% of frequent attenders came from communities in more remote locations. Two papers determined that geographic health usage trends depended upon the service being accessed [

29,

30]. Youth living in rural areas accounted for higher rates of specialist visits, whereas youth living in urban areas were more likely to draw on family physician and emergency department visits [

29,

30]. Penning (2016) found that rural frequent attenders were more likely to be hospitalized, whereas urban folk were more likely to draw on general practitioner and specialist services in general. Another study indicated that hospitalization rates, average length of hospital stay, total length of hospital stay, and readmission rates all increased with increasing distance that a patient lived from the hospital [

36].

In contrast, two studies determined that urban populations comprised an increased proportion of high-resource users. While Springer (2017) only identified a slight increase in urban frequent use than in rural, Guilcher (2016) found that urban dwellers accounted for almost 90% of high-cost health users.

3.2.3. Service Access

Five studies analyzed the impact of service access on high-frequency use; all 5 of these identified low access/remoteness as a risk factor [

19,

23,

24,

33,

35]. Greater access problems were associated with higher admission rates in all ACSC categories [

35] and in hospitalization rates in general [

19]. In one study, people who reported inadequate access to health care services had ten-times higher hospitalization rates than those with highest service access [

19]. Of those, people who lacked access to a primary care doctor demonstrated an 8% increase in hospitalization rates and 11–14% higher admittance rates than baseline [

19]. Inadequate access to hospital services resulted in twice the higher raw probability of admission than the baseline group, with a 25% increase in admissions for physical conditions and a 21% increase in admissions for mental conditions [

19]. Inability to fully access hospital services raised emergency department visits by more than 20% for both mental and physical conditions [

19].

Brameld (2006) analyzed the impact of accessibility via hospitalization rates for those with low, moderate, and high access to health care services [

24]. Hospital admissions in the lowest access category were 3.2–4.6 times higher than those in highest access category, while those in the moderate access were 2.4–3.4 times higher. The highest access group demonstrated lowest hospital admissions, lowest surgical admission rates, and lowest medical admission rates for most diseases in the major diagnostic categories. When examining specific admissions, lowest access regions had the highest admission rates for injuries and burns, and lowest admission rates for diseases of the kidney and urinary tract, and neoplastic disorders. Lower access regions also had higher risk of readmission and of longer lengths of stay.

Two studies identified inaccessible transportation as a predictor of high-frequency use. Quilty (2019) noted that only 20% of high-frequency users had a car and, due to rural and remote living, no public transport was available [

33]. Similarly, Longman (2012) found nearly one third of high-frequency users did not have a car they could drive and, of those living alone, 29% did not have access to a car at all [

23].

4. Discussion

4.1. Individual-level characteristics

Several individual-level characteristics served as indicators for high-resource use, regarding how often services were accessed and which services were accessed most frequently. Older age, greater health needs, lower socioeconomic status, higher risk behaviour(s) and Aboriginal status all increased the risk of reliance on high-resource use. The relationship between sex and high-resource use was less linear, as sex served as an indicator for which type of service was more frequently accessed. For example, females were more likely to access preventative, primary, and specialist care services, whereas males were more likely to be hospitalized. Due to the impact of high-resource users on national health care expenditure, and the potential to alleviate this by targeting risk-factors, these individual-level characteristics must be better understood in the context in which they arise.

4.1.1. Need Factors

People with higher comorbidity indices face greater risk of illness exacerbation and complication, thereby increasing emergency care use. When chronic conditions are inadequately addressed, admission rates climb [

19]; patients with chronic conditions are more likely to visit the emergency department if they do not have a regular health care provider [

25]. Researchers noted that most high-resource users presenting with comorbidities would benefit from multidisciplinary primary care and/or specialist care, suggesting that high-resource users have unmet health needs and/or poorly managed chronic diseases [

26]. Garne (2009) noted that those with chronic health conditions may also benefit from living closer to secondary or tertiary health care centres, indicating that rural and remote living was contributing to poorer health.

In terms of quantifying comorbidities, Penning (2016) argues that a broader set of health status indicators would be more appropriate when examining whole populations [

17]. For example, inclusion of acute conditions may better reflect the health care needs of younger populations who may not have developed comorbid conditions yet. This would indicate an underestimate of comorbid conditions in younger populations, thereby suggesting greater comorbidity burdens than reported.

4.1.2. Older Ages

The relationship between age and health care expenditure has been of growing interest to Canadian researchers and policy makers alike due to the impending health care implications of rapid population ageing [

37]. While older age in of itself was identified as a risk factor for high-resource use, older people also presented with other risk factors, including elevated rates of comorbid conditions and social isolation.

Longman (2012) identified other aspects of social deprivation, including lower social network scores and social isolation, among older high-resource users. Social isolation is associated with poorer health, depression, and loss of confidence [

23]. Interventions to ameliorate health outcomes of ageing Canadians should consider the social implications of ageing, including social isolation, due to the associations between social networks and health outcomes.

4.1.3. Sex

Although many of the papers in this review analyzed sex-based differences, none considered the social implications of gender. The ramifications of entrenched gender norms, especially in rural and remote communities, largely impact health-seeking and health behaviours. These place men at greater risk of undetected disease and subsequent illness exacerbation in comparison to females.

Generally, men are less likely to partake in preventative health and to seek health care. Prior studies suggest that men in rural communities are especially vulnerable, as they are less likely to use preventative health services than their urban counterparts [

26]. Men are also more likely to partake in risk behaviours, such as excessive alcohol consumption and smoking. Current gender-neutral or gender-blind research may be failing to identify social factors that impact other risk factors for high-resource use. These social risk factors could serve as targets for intervention, which could prevent dependence on health care services by ameliorating baseline levels of health.

4.1.4. Socioeconomic Status

In the case of rural and remote regions, generalized lower socioeconomic status, lower education attainment, and increased health burdens place rural health seekers at further disadvantage. While rural and remote regions face higher comorbidity burdens in comparison to urban centres, interventions such as multidisciplinary care are often not practically feasible due to prevailing inadequacy in rural and remote health care services, in which limited resources and staff shortages challenge health care delivery.

Despite universal care rebates and the potential for private health insurance coverage, lower socioeconomic status was a risk factor for lower access to care. In the study conducted by Manos (2014), youth from lower socioeconomic backgrounds were less likely to access primary care services. This finding is consistent with data from the United States, despite Canada’s publicly funded health care [

29].

In prior research, pro-rich inequities in accessing primary care have been referred to as minor, whereas inequities in specialist care are widely considered problematic [

17]. Over the course of the study by Penning (2016), those in the lowest income quintile were significantly less likely to receive primary care services compared to higher income quintiles as the decade progressed. This association was attributed to an increasing disadvantage of health care for those in the lowest income group [

17]. The inability for lower income groups to access adequate care contributes to a growing, negative cycle: lower socioeconomic status contributes to poorer health, which increases the need for money spent on health care needs, which then worsens lower socioeconomic status.

4.1.5. Risk behaviours

Excessive alcohol consumption and smoking were both identified as risk factors for high-resource use. Excessive alcohol consumption was identified as the largest risk factor for high-resource use in the Northern Territory of Australia [

18], whereas smoking was one of the largest risk factors for adults living in Québec [

20]. Risk behaviours are elevated both in rural and remote communities and in Aboriginal communities, thereby placing these populations at greater risk for related comorbidities and related outcomes. Springer (2017) highlighted the associations between alcohol and other comorbidities, highlighting its risk of exacerbating existing susceptibility to high-resource use and its impact on others.

4.1.6. Aboriginal status

Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people demonstrate distinct presentations of high-resource use. High-resource users who were Aboriginal were found to be younger and more commonly female than their non-Aboriginal counterparts. Such differences were largely attributed to considerable social disadvantages for Aboriginal populations, which serve to exacerbate existing inequities in health outcomes and access to health care [

33].

Overall, aboriginal people demonstrate shorter life expectancy; lower education levels; low employment and income levels; higher comorbidity burdens; higher risk behaviours; elevated rates of childhood abuse, neglect, and violence; and inadequate housing [

28]. With such inherent disadvantage, it is no surprise that Aboriginal people account for a greater proportion of high-resource users than non-Aboriginal people. Aboriginal people experience inadequate housing much more than non-Aboriginal high-resource users, which can exacerbate illness severity and subsequent hospital use [

33]. Housing insecurity and subsequent exposure to extreme weather are likely to increase hospital utilization [

36]. As the climate crisis continues to worsen, the health problems associated with experiencing homelessness will also become more challenging [

36].

Historical oppression and marginalization of Aboriginal people propagate widespread disengagement from mainstream health care systems. Aboriginal populations face barriers in accessing western health care due to pervasive colonial disadvantage. Common concerns include fear of discrimination, lack of trust or confidence in providers, and culturally inappropriate service [

28]. To improve the health outcomes of Aboriginal populations, the systemic barriers and inequalities must first be addressed through broad policy and local practice initiatives [

28].

4.2. Geographic-Level Characteristics

4.2.1. Rural and Remote Determinants of Health

Generally, rural, and remote regions tend to have higher comorbidity burdens, higher rates of physical inactivity, elevated risk of injury, and higher risk behaviours. These factors compound existing geographic challenges in achieving better health outcomes, including access to health care, and limited local resources. The literature included in this review cited rural and remote living as a risk factor for high-resource use. Despite commonly attributing rurality as a risk factor for high-resource use, limited studies discussed the implications of this discrepancy. Of those that did discuss geographic determinants, decreased access to health care and challenges maintaining a stable work force contributed to high-resource use.

Rural and urban emergency departments are characteristically different due to resource availability, provider shortages, and baseline health levels of populations. In rural and remote regions, a higher proportion of people visit emergency departments for less urgent or non-urgent conditions in comparison to urban centres due to a lack of primary care services [

38]. Accessing emergency services for less urgent or non-urgent conditions is often classified as inappropriate or even abusive use of the health care system; however, such categorization overlooks the inability to adequately respond to these health concerns outside of the emergency setting.

Despite longstanding geographic-based health discrepancies, the impact of “place” in shaping health behaviours has not been clearly defined [

38]. This may be due to prior research that determined sociocultural characteristics were relatively unimportant in explaining health care service use [

38]. Although this finding is now dated almost thirty years, the characteristics of the people who use health care services are still the focus of most high-resource use rather than the communities from which they are sought [

38]. For example, a significant proportion of rural emergency department presentations required routine or primary care, often because it was the only place that could provide routine care [

38]. Some patients reported that they accessed emergency services because their primary care physician was the ED physician on-call, whereas others did not have a primary care physician. Despite opposite motivations, both indicate fractured continuity of care.

4.2.2. Access to Health Care

Inadequate health care services in rural and remote communities can enable undertreated or untreated health conditions, thereby increasing the risk of escalating existing conditions [

19]. People from rural and remote locations tend to have longer hospital stays, which is partially attributed to lower access to care [

24]. For example, when a doctor suspects a patient has little to no access to ambulatory care, they may be more inclined to keep the patient for observation [

36]. Similarly, they may more readily admit patients if there is possibility of serious complications with insufficient local resources. This scenario would be similar if a patient does not have adequate transportation to or from a hospital. Lack of transport also exacerbates social isolation, which was identified as a risk-factor for high-resource use in elderly populations.

4.2.3. Recruitment and Retention of Physicians

Often, challenges in recruiting and retaining physicians widens gaps in health services in rural and remote communities. In addition to a lack of specialist and subspecialists [

26], rural regions also struggle with primary care practitioner shortage [

25]. Lack of health services leads to challenges accessing care, often due to long travel distances and/or inaccessible transportation options. Even if general practitioners are available in the region, patients are less likely to seek care if they perceive the doctor as unavailable [

19]. Availability of primary care doctors is integral in preventing hospital admissions, especially in rural and remote regions [

28], as suboptimal provisions of local health care continue to contribute to excessive emergency department burdens [

19].

4.3. Strength of Evidence Analysis

4.3.1. Prolonged High-Resource Use

Generally, few studies investigated long-term patterns of high-resource users. Despite its burden on health infrastructure, only one study included in the review investigated characteristics of patients with prolonged periods of high-resource use. Springer (2017) found risk factors for prolonged high-resource use, including older age, alcohol-related conditions, and Aboriginal status. Differentiating between short-term and long-term frequent attenders could enable identification of characteristics to create more specific, targeted interventions for prolonged high-resource users. The generalization of high-resource users is widespread, as most international intervention studies have been aimed at the entire high-resource cohort instead of targeting either short- or long-term users [

39]. Prior research suggests that persistent high-resource users may benefit from case management and increased continuity of primary care in comparison to temporary high-resource users [

39]. Discrepancies have also been identified between age groups. For example, young adults with prolonged high-resource use may benefit from additional services outside of the emergency department, whereas children could benefit from longer-term interventions that reduce likelihood of admission and subsequent length of hospital stays [

39]. The relationships between length of high-resource use and other individual- and geographic-risk factors demarks the complexities of researching and of subsequently ameliorating overreliance on health care services. Like the neglect of heterogeneity in rural populations, the vast variation between and within high-resource cohorts is markedly overlooked, thereby undermining more targeted efforts to ameliorate high-resource health care use.

4.3.2. Length of Follow-Up

Longitudinal studies are currently lacking in the literature; these could enable the examination of whether and how relationships between people and health care services have changed over time [

17,

20]. In the analysis by Penning (2016), researchers found that declines in access to hospital care are coupled with increasing income-related disparities in access to care. Such trends would denote increasing inequities in access to health care, thereby challenging the equity principles in Canada’s publicly funded health care system [

20]. In addition to larger-scale studies that compare health use within and across provinces, identifying localized areas of need would enable targeted resources for populations as opposed to individuals [

28]. This would be especially applicable in rural and remote populations, due to community-wide health determinants.

4.3.3. Length of Hospital Stays

Emergency department overcrowding is primarily attributed to preventable/avoidable hospital visits and lengthy hospital stays [

40]. Many studies focus on avoidable hospital visits (i.e., ACSC) to measure high-resource use; however, studies indicate that lengthy hospital visits contribute more to emergency department congestion [

40]. In this scoping review, Springer (2017) determined that the duration of high-resource use was elevated among older adults compared to younger high-resource users, indicating prolonged elevated health utilization and expenditure.

4.3.4. Social Determinants of Health

The primary social inequities considered in included studies were education, income, employment, and homelessness. Three studies did not include consideration of social inequities, whereas the remaining 18 included social inequities in analyses, discussion, or both. Ansari (2006) acknowledged the inability to include social determinants of health due to inaccessibility of data.

Wallar (2020) analyzed and discussed the impacts of immigrant status and race in high-resource use patterns, where he found that immigrant status was a protective factor. He attributed this to the healthy immigrant effect [

20]. No other studies considered the impact of immigrant status or race.

4.3.5. Consistent Definitions

Despite diverse realities within and between rural communities, geographic determinants are often operationalized as urban or rural [

38]. Such dichotomization of rurality denotes limited understanding of the heterogeneity of rural populations and masks disparities between and within rural regions. Evaluations of geographic disparities in health outcomes are difficult due to the multiplicity of ways in which rural has been defined [

41]. While researchers and policy makers alike have attempted to create a standardized definition of rural, many assert that one definition would be insufficient due to the heterogeneity between rural communities [

41]. Although the various definitions of rural serve as a shortcoming of individual studies, the discrepancies point to widespread systemic barriers that impede rural-centric classifications on national and international levels.

High-resource users were also treated as a homogenous group, despite differing health needs and risk factors based upon a person’s sex, age, and geographic location. Definitions of high-resource use varied depending upon study design and region. To address high-resource use on a national scale, standardized methods of quantifying high-resource users must be developed and adopted, with consideration of differences based upon geographic location.

4.3.6. Social Inequities

This review identified a gap in social inequity analyses in available literature, primarily in relation to gender-based and cultural factors. The exclusion of cultural differences in service use is significant, as culturally based attitudes, care preferences, and health seeking behaviours largely impact health outcomes for those from non-English speaking backgrounds [

38]. Due to ongoing marginalization of rural and remote and of Aboriginal communities, cultural considerations must be prioritized when developing and integrating interventions in these regions. In the same way that rural and remote communities are not homogenous, their challenges in accessing and utilizing health care efficiently and adequately are also not homogenous. Because of this, a “one-size-fits-all” model is not effective. The social, demographic, logistic, and cultural constructs of certain demographics should be considered when creating solutions [

33]. Further, common skepticism of outsiders in rural and remote communities often render interventions less effective. Collaboration with community members to identify problems and to develop solutions mitigates this gap and promotes participation.

4.3.7. Overall Strength of Evidence

Although high-resource health care users account for a disproportionate amount of health care resources, they are often overlooked in literature and in health policy discourse. This broad-based scoping review produced 21 studies with each of these studies demonstrating the extent to which high-resource users impact local/regional health systems. However, no national-level review has been conducted.

Overall, the strength of high-resource health research in Canada and Australia is low, due to narrow geographic breadth, lack of longitudinal analyses, exclusion of population groups, and limited considerations of social determinants of health. Although most studies included in the review identified remoteness as an indicator of high-resource use, few discussed the rural-specific factors that promote such dependence upon health care services. To address the national burden of high-resource users, national-level studies must be conducted. Further, specific regions with increased risk must be identified and prioritized when developing interventions.

Although prolonged high-resource use places a larger burden on the health care system than short-term frequent use, only two studies in this review included analyses of high-resource use over time. Prolonged high-resource users should be prioritized in health interventions, due to their longer-term impact on the health care system. Further, since prolonged high-resource use indicates prolonged unmet health needs, regions with a high rate of prolonged high-resource users should be the primary focus of initial efforts to mitigate high-resource use.

To create a framework to ameliorate the health of high-resource users, nationally funded studies are needed. Such data can then enable evidence-based alterations to health policy, especially in relation to better serving those at risk for high-resource use via prevention and primary care.

4.4. Study Limitations

Scoping reviews are limited by an inherent risk of selection bias, as relevant sources may have been omitted due to relevance to the research question. To mitigate bias, the scoping review was completed by two researchers with predetermined exclusion and inclusion criteria. A relatively small number of papers were included in the study, which may limit its generalizability. However, the small pool of available papers also denotes a lack of research in rural high-resource users and serves as an indicator of future growth. The disparities in definitions of rural and high-resource between papers also serves as a limitation on a review-level. Although this was accounted for in the discussion, the lack of standardized terminology challenges collation of findings. Further, due to limited pool of Canadian literature on high-resource users, studies regarding high-resource users in Australia and Canada were grouped and analyzed together. This analysis may have overlooked the differences between Australian and Canadian health infrastructure and inequities, i.e., in relation to Aboriginal populations.

5. Conclusions

Despite promises of universal health care, a significant proportion of the Canadian population struggle in accessing health care and in staying healthy, which subsequently promotes high-resource reliance on health care services. Shortcomings in providing adequate health care reveal significant gaps within the current national health care infrastructure. To alleviate the economic and health burdens of high-resource users, the risk factors of being or becoming a high-resource user should be identified and subsequently targeted in mitigation efforts. This review served to identify risk factors of rural high-resource use based upon available literature in Canada and Australia.

The primary risk factors of being or becoming a high-resource user as identified in this review include older age, female sex, increased need factors, lower socioeconomic status, elevated risk behaviour(s), and Aboriginal status. However, differing levels of risk were identified between and within these categories. For example, although high-resource users were more commonly female than male, males were more at-risk of frequent hospitalization.

Although these findings summarize those of available literature, national-level studies are necessary to better understand high-resource use on a national level and subsequently alleviate its burden on the national health care system. Once individual risk factors for high-resource use are identified, geographic determinants of high-resource use should be identified to provide interventions where they are most needed. Further, the structural health care shortfalls that propagate high-resource use would need to be identified and addressed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1: Synthesis Table of Included Literature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and P.P.; methodology, M.L.; evidence review and summary, M.L, T.M, and P.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.; writing—review and editing, M.L, T.M, and P.P.; funding acquisition, P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ontario Ministry of Health (Canada), through an Ontario Early Researcher Award (ERA) number ER18-14-064, Patient Experiences of High Health System Users in Rural Canada; and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Canada) Connection Grant number 611-2017-0548, Free Range International Knowledge Exchange.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Figueroa, J.F.; Papanicolas, I.; Riley, K.; Abiona, O.; Arvin, M.; Atsma, F.; et al. International comparison of health spending and utilization among people with complex multimorbidity. Health Serv Res. 2021, 56 (Suppl. S3), 1317–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosella, L.C.; Fitzpatrick, T.; Wodchis, W.P.; Calzavara, A.; Manson, H.; Goel, V. High-cost health care users in Ontario, Canada: demographic, socio-economic, and health status characteristics. Bmc Health Serv Res. 2014, 14, 532–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wammes, J.J.G.; Wees PJ van der Tanke, M.A.C.; Westert, G.P.; Jeurissen, P.P.T. Systematic review of high-cost patients’ characteristics and healthcare utilisation. Bmj Open. 2018, 8, e023113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.; Evans, R.; Barer, M.; Sheps, S.; Kerluke, K.; McGrail, K.; et al. Conspicuous consumption: Characterizing high users of physician services in one Canadian province. J Heal Serv Res Policy. 2003, 8, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.H.X.; Rahman, N.; Ang, I.Y.H.; Sridharan, S.; Ramachandran, S.; Wang, D.D.; et al. Characterization of high healthcare utilizer groups using administrative data from an electronic medical record database. Bmc Health Serv Res. 2019, 19, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, T.; Rosella, L.C.; Calzavara, A.; Petch, J.; Pinto, A.D.; Manson, H.; et al. Looking beyond Income and Education: Socioeconomic Status Gradients among Future High-Cost Users of Health Care. Am J Prev Med. 2015, 49, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibley, L.M.; Weiner, J.P. An evaluation of access to health care services along the rural-urban continuum in Canada. Bmc Health Serv Res. 2011, 11, 20–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garasia, S.; Dobbs, G. Socioeconomic determinants of health and access to health care in rural Canada. University of Toronto Medical Journal. 2019, 96, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, L.; Humphreys, J.S.; Wakerman, J.; Taylor, J. Understanding rural and remote health: A framework for analysis in Australia. Health Place. 2012, 18, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhold, I.; Gurtner, S. Understanding shortages of sufficient health care in rural areas. Health Policy. 2014, 118, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesbrecht, M.; Crooks, V.A.; Castleden, H.; Schuurman, N.; Skinner, M.W.; Williams, A.M. Revisiting the use of ‘place’ as an analytic tool for elucidating geographic issues central to Canadian rural palliative care. Health Place. 2016, 41, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, P.A. Broadening the narrative on rural health: From disadvantage to resilience. University of Toronto Medical Journal. 2019, 96, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lavergne, M.R.; Kephart, G. Examining variations in health within rural Canada. Rural and remote health. 2012, 12, 1848–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018, 169, 467–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufour, I.; Chiu, Y.; Courteau, J.; Chouinard, M.; Dubuc, N.; Hudon, C. Frequent emergency department use by older adults with ambulatory care sensitive conditions: A population-based cohort study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020, 20, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penning, M.J.; Zheng, C. Income Inequities in Health Care Utilization among Adults Aged 50 and Older. Can J Aging La Revue Can Du Vieillissement. 2016, 35, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, A.M.M.; Condon, J.R.R.; Li, S.Q.Q.; Guthridge, S.L.L. Frequent use of hospital inpatient services during a nine year period: A retrospective cohort study. Bmc Health Serv Res. 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, N.; Davies, D.; Rohde, N. The effect of inadequate access to healthcare services on emergency room visits. A comparison between physical and mental health conditions. Plos One. 2018, 13, e0202559. [Google Scholar]

- Wallar, L.E.; Rosella, L.C. Risk factors for avoidable hospitalizations in Canada using national linked data: A retrospective cohort study. Plos One. 2020, 15, e0229465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Ospina, M.; McRae, A.; McLane, P.; Hu, X.J.; Fielding, S.; et al. Characteristics of frequent users of emergency departments in Alberta and Ontario, Canada: an administrative data study. Can J Emerg Med Care. 2021, 23, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, J.; Wang, E.; McGregor, M.J.; Schull, M.J.; Dong, K.; Holroyd, B.R.; et al. Subgroups of people who make frequent emergency department visits in Ontario and Alberta: a retrospective cohort study. Can Medical Assoc Open Access J. 2022, 10, E232–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longman, J.M.; Rolfe, M.I.; Passey, M.D.; Heathcote, K.E.; Ewald, D.P.; Dunn, T.; et al. Frequent hospital admission of older people with chronic disease: a cross-sectional survey with telephone follow-up and data linkage. Bmc Health Serv Res. 2012, 12, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brameld, K.J.; Holman, C.D.J. The effect of locational disadvantage on hospital utilisation and outcomes in Western Australia. Health Place. 2006, 12, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, E.; Leblanc-Duchin, D.; Murray, J.; Atkinson, P. Emergency department use: is frequent use associated with a lack of primary care provider? Can Fam Physician Med De Fam Can. 2014, 60, e223–e229. [Google Scholar]

- Garne, D.L.; Perkins, D.A.; Boreland, F.T.; Lyle, D.M. Frequent users of the Royal Flying Doctor Service primary clinic and aeromedical services in remote New South Wales: a quality study. Med J Australia. 2009, 191, 602–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilcher, S.J.T.; Bronskill, S.E.; Guan, J.; Wodchis, W.P. Who Are the High-Cost Users? A Method for Person-Centred Attribution of Health Care Spending. Plos One. 2016, 11, e0149179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Z.; Rowe, S.; Ansari, H.; Sindall, C. Small Area Analysis of Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions in Victoria, Australia. Popul Health Manag. 2013, 16, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manos, S.H.; Cui, Y.; MacDonald, N.N.; Parker, L.; Dummer, T.J.B. Youth health care utilization in Nova Scotia: What is the role of age, sex and socio-economic status? C J Public Health. 2014, 105, e431–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiller, R.; Chan, K.; Knight, J.C.; Chafe, R. Pediatric high users of Canadian hospitals and emergency departments. Plos One. 2021, 16, e0251330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.M.; Dufour, I.; Courteau, J.; Vanasse, A.; Chouinard, M.C.; Dubois, M.F.; et al. Profiles of frequent emergency department users with chronic conditions: a latent class analysis. Bmj Open. 2022, 12, e055297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, J.; O’Sullivan, F.; McGregor, M.J.; Schull, M.J.; Dong, K.; Holroyd, B.R.; et al. Identifying subgroups and risk among frequent emergency department users in British Columbia. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021, 2, e12346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilty, S.; Wood, L.; Scrimgeour, S.; Shannon, G.; Sherman, E.; Lake, B.; et al. Addressing Profound Disadvantages to Improve Indigenous Health and Reduce Hospitalisation: A Collaborative Community Program in Remote Northern Territory. Int J Environ Res Pu. 2019, 16, 4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, C.L.; O’Driscoll, T.; Blakeloch, B.; Kelly, L. Characterizing high-frequency emergency department users in a rural northwestern Ontario hospital: a 5-year analysis of volume, frequency and acuity of visits. Can J Rural Medicine Official J Soc Rural Physicians Can J Can De La Med Rurale Le J Officiel De La Soc De Med Rurale Du Can. 2018, 23, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, Z.; Laditka, J.N.; Laditka, S.B. Access to Health Care and Hospitalization for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions. Med Care Res Rev. 2006, 63, 719–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilty, S.; Shannon, G.; Yao, A.; Sargent, W.; McVeigh, M.F. Factors contributing to frequent attendance to the emergency department of a remote Northern Territory hospital. Med J Australia. 2016, 204, 111–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falster, M.O.; Jorm, L.R.; Douglas, K.A.; Blyth, F.M.; Elliott, R.F.; Leyland, A.H. Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics, Rather Than Primary Care Supply, are Major Drivers of Geographic Variation in Preventable Hospitalizations in Australia. Med Care. 2015, 53, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M.; O’Flaherty, M.; Haynes, M.; Mitchell, G.; Haines, T.P. Health for all? Patterns and predictors of allied health service use in Australia. Aust Health Rev. 2013, 37, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreindler, S.A.; Cui, Y.; Metge, C.J.; Raynard, M. Patient characteristics associated with longer emergency department stay: a rapid review. Emerg Medicine J Emj. 2015, 33, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, L.; Westley-Wise, V.; Mullan, J.; Lambert, K.; Zingel, R.; Carrigan, T.; et al. Here one year, gone the next? Investigating persistence of frequent emergency department attendance: a retrospective study in Australia. Bmj Open. 2019, 9, e027700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, M.J.; Wuest, J. Uncovering factors affecting use of the emergency department for less urgent health problems in urban and rural areas. Can J Nurs Res Revue Can De Recherche En Sci Infirm. 2007, 39, 78–102. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).