1. Introduction

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency due to the Covid-19 pandemic [

1,

2]. On March 15, 2020, the Spanish Government declared a state of national alarm with regulations including restrictions on restricted mobility and confinement of the population, intended to facilitate diagnosis, guarantee adequate treatment and reduce the spread of CoVID-19 [

3].

Despite all these emergency measures, the number of admissions in the Intensive Care Units (ICU) of hospitals pandemics increased exponentially during the CoVID-19. To tackle this emergency situation Hospitals escalated the UCIs in order to assist the increasing number of patients. However, the lack of professionals and particularly of specialized nurses during the pandemic difficulted the expansion of ICU [

4]. To solve this problem, hospitals in the Catalan health network recruited nurses from other units, such as the operating theatre, and emergency wards. Nevertheless, this measure was insufficient due to the large number of contagions and led ICUs to a situation near to the collapse. In order to revert this situation, on 15 March 2020, the Ministerial order SND/232/2020 [

5] stated a series of measures with the main objective of strengthening the National Health System throughout the Spanish territory. This order included, the hiring of students in the last year of the Nursing Degree with temporary health care aid contracts. These students possessed insufficient skills to care for critical patients and the emergency situation prevented the possibility to provide them a proper training. For this reason, nursing students were incorporated into the ICUs as supporting staff but always under the supervision of a critical patient professional nurse, to train them as they were working. Similar measures were implemented by other countries, such as England and China, during the pandemic [

6,

7].

According to the Standards and recommendations of the ICUs [

8], drafted in 2010 by the Ministry of Health and Social Policy, expertise in the care of critical patients requires months of postgraduate training in order to acquire the specific competences to ensure a high quality care of these patients.

Competences are defined as "the intersection between knowledge, skills, attitudes and values, as well as the mobilization of these components, to transfer them to the context or real situation, creating the best action/solution, to respond to the different situations and problems that arise in each moment, with the available resources" [

9]. Based on the Dreyfus brothers’ model of acquisition and development of competences [

10] Patricia Benner determined that a nurse is not able to take care of a critical ill patient until the nurse is competent [

11]. A nurse is considered competent when she has 2-3 years of professional experience in the same circumstances that allow her to cope with the events of her daily clinical practice. On other words, nurses are competent when they have experience in the majority of the situations that allow her to develop patient’ care plans, as she knows the interventions and their results, acts based on rules and theory, plans daily, decides and carries out activities with long-term results in mind, and identifies the limitations of protocols and guidelines [

12,

13,

14]. For this reason despite an appropriate qualification, ICU nurses need to possess specific professional skills by combining technical-scientific knowledge, humanity and individualized care in order to develop an effective performance [

15].

Importantly, the absence of specific competences in the care of the critical ill patients by professionals is related to an increase in the number of complications and adverse effects on the provision of care that compromise patient safety [

16]. For this reason, it is crucial to evaluate the level of competence of the new enrolled ICU nurses during the COVID-19: nurses of other wards and nursing students in placement and health care aid, in the care of critical patients, in order to minimize the adverse effects in the patient care and to determine formative strategies to revert the competence deficiencies in the face of future new pandemics.

2. Methods

Cross-sectional descriptive study with a quantitative methodology that was carried out at a University and a Hospital in Catalonia.

2.1. Participants

A total and intended of 66 participants were selected; 36 new ICU nurses, 11 fourth year nursing students on placement and 19 fourth year nursing students on healthcare aid contract, during the months of October 2020-March 2021.

2.2. Data Collection

The independent variables were collected through a questionnaire of socio-demographic and occupational data designed ad-hoc by the research group that included: sex and age, category of participant (student, new professional, student on healthcare aid contract), professional experience, self-confidence in dealing with the critical patient (0-10) and finally their perceptions of their own abilities to care the critical patient (yes, no).

The dependent variables were collected through the questionnaire of Evaluation of Nursing Competences, COM-VA

©, a validated questionnaire, where the professional's and all the students self-evaluated and scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (very poor performance) to 10 (excellent performance) their usual daily performance [

17].

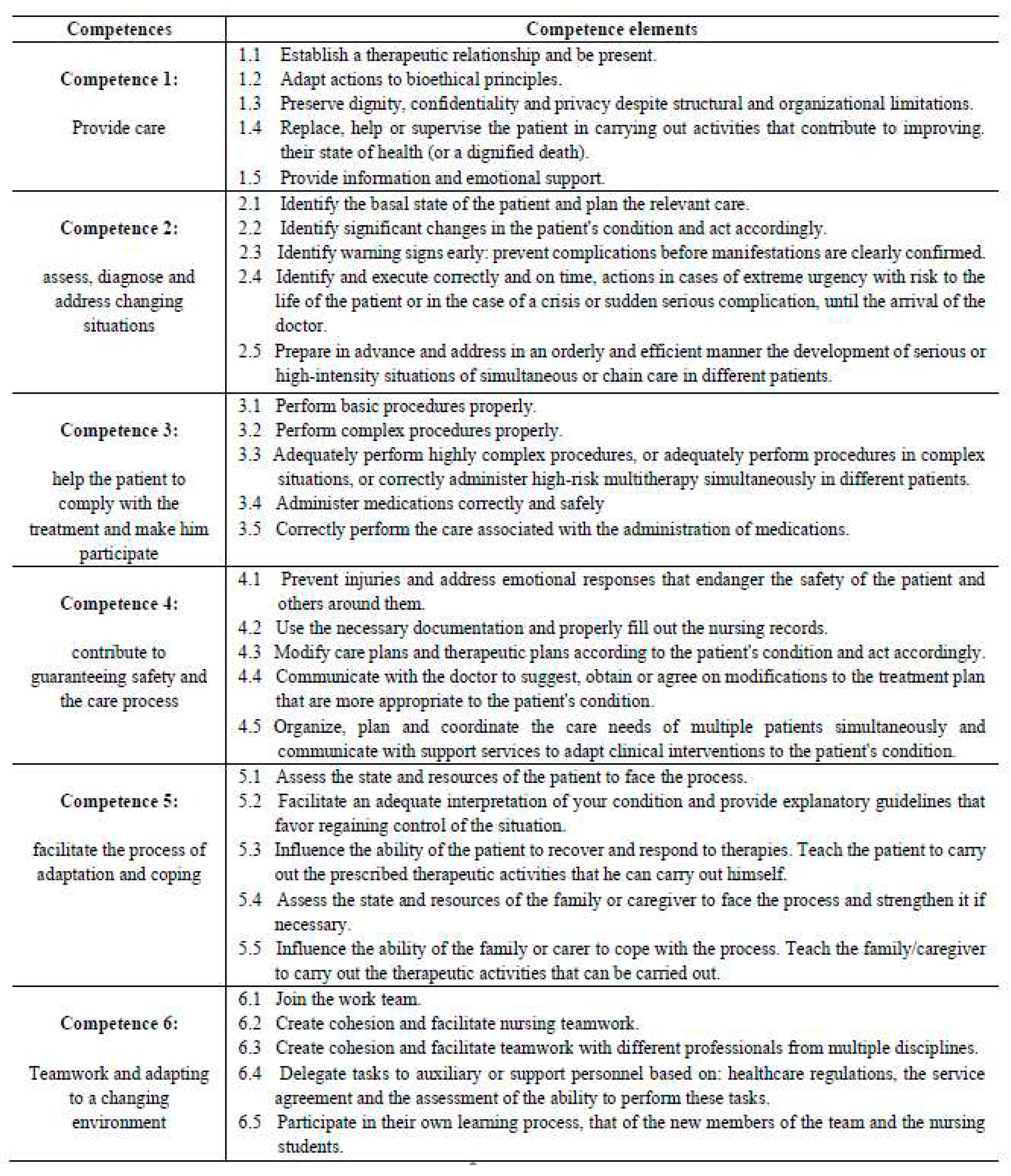

The COM-VA

© questionnaire consist of 6 transversal competences, each of them divided into 5 competency elements (

Figure 1) that allowed to evaluate 30 nursing competency elements [

18].

Self-assessment COM-VA© questionary of the participants and a parallel assessment of each participant by the supervisor/mentor was carried out. A third assessment was applicable, done by a second supervisor/mentor, if there was a difference of more than 20% between the two COM-VA© scores obtained.

2.3. Quantitative Analysis

In order to analyze the data, a descriptive analysis of frequency and percentage of the categorical variables and of median and interquartile range for the continuous variables by groups was carried out. The competences of both professionals and mentors were described using mean, standard deviation and median by groups.

In order to detect statistically significant differences in the competences between professionals, students with healthcare aid contract and nursing students on placement, the non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used.

2.4. Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Research with Medicines (CEIm) of the Pere Virgili Health Research Institute (IISPV) (256/2020) and the respective managements of the participating centers, and authorization was also obtained from the author of the COM-VA© questionnaire for its use. Each participant signed informed consent. In order to maintain anonymity, the questionnaires were coded. The research was carried out in accordance with the rules of the Helsinki Declaration.

3. Results

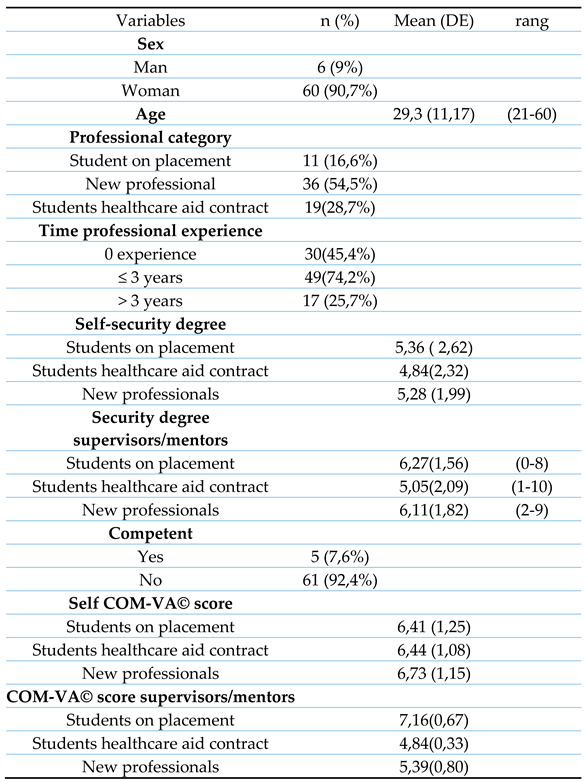

The average age of the 66 participants was 29.3 years old and 90.70% were women. 45.4% of the participants possessed nonprofessional experience and only 25.7% of participants declared to have more than 3 years of work experience (

Table 1).

The socio-demographic and occupational results revealed that the degree of self-confident perceived dealing with critical patients by the students on placement, was the highest, with a score of 5.36 (ds: 2.62) whereas the lowest 4.84 (ds: 2.32) was obtained by the students on healthcare aid contract.

The average score obtained in the COM-VA© questionnaire of all participants was between 6-7, indicating that their competency was good enough to work autonomously. In contrast, the average score of COM-VA© of the participants by the supervisors/mentors evaluation shows significant differences (p<0.001) between the different groups. Whereas, the group of students in placement obtained an average score of 7.16, which corresponds to a level of competency in an autonomous manner; the group of newly incorporated professionals and the group of contracted students presented and scored of 5.39, minimum acceptable execution, and 4.84, insufficient execution, respectively. These results indicate that 92.4% of participants did not feel competent enough to deal with critical ill patients.

Analysis in detail of the data from the COM-VA

© questionnaire (

Table 2) of the total number of participants, showed a significant difference in competency 2.4 corresponding to the ability to identify and carry out actions correctly and on time in cases of extreme urgency with risk to the patient's life or in the event of a crisis or complication (P=0.026); and competency 3.3 in carrying out highly complex procedures adequately or administering high-risk medication correctly (P=0.039).

When compared by groups, it is observed that the group of new professionals vs. students on placement only show significant differences in competency 1.2 in adapting actions to bioethical principles (P=0.039).

The group of professionals vs students in healthcare aid contract also showed significant differences in competence 2.3 in early identification of warning signs: anticipation of complications before the manifestations are clearly confirmed (P=0.037).

In the comparison of the group of new professionals with all the students, significant differences were observed in competency 4.4 in communicating with the doctor to suggest, obtain and/or agree on modifications to the therapeutic plan most appropriate to the patient's condition (P=0.020) and 4.5 in organize, plan and coordinate the care needs of multiple patients simultaneously (P=0.046).

However, the results obtained from the evaluation of the different competencies by the supervisors and mentors, significant differences are observed in all 6 competences and competency elements (P<0.001).

4. Discussion

Clinical practice is an essential part of the training of nursing students as helps them to become confidents and competent professionals [

19]. In order to generate competent professionals, there are three indispensable elements: knowledge, specialized practice and ethics [

20,

21]. Working experience is a key factor to gain competence and security in specialized nursing care. Accordingly, our data showed that students on healthcare aid contract and new professionals, without work experience felt insecure dealing with critical patients. This observation supports the idea of that a new student or professional has a solid body of knowledge but lack of sufficient skills to deal with a real clinical situation [

22]. Surprisingly, students on placement presented the highest confidence in critical patient care. Such difference perception about security might be explained by the presence of the figure of the mentor during the placement period. In this sense, it has been shown that supervision and clinical support improves self-confidence of unexperienced nurses and patient safety [

23,

24,

25].

On the other hand, the self-assessment COM-VA

© score of the participants shows a relative high level of nursing competency corresponding to an autonomous and correct management of the critical ill patient. These results contrast with the COM-VA

© scores of the participants evaluated by the supervisors/mentors. Intriguingly, whereas mentor considers that students in practice possess sufficient nursing competency, ICU supervisors determined that students on healthcare aid contract and new professionals lacked of enough level of competence to deal with critical patient. This surprising finding seems to contradict the general statement that students in practice do not have sufficient internalized skills to cope with certain types of environment and patients [

26]. However, the most likely explanation might be that mentors overestimate the level of competence and degree of safety of the students with regard to critical patient care. In this sense it is important to remark that mentors provide the scientific-methodological support with the aim of guiding students in their correct choice of the methodologies, essential care techniques and instruments of critical ill patients [

27]. A close student support, therefore might explain the higher confidence of students and an overestimation of their competences by mentors. On the other hand, UCI supervisors usually consider new graduate to be practice-ready in critical patient care than student nurses [

28,

29]. This makes UCI supervisor probably more demanding and estrict when evaluating the competence of students’ healthcare contract and new professionals. In this regard, simulation could be a good tool for a more objective evaluation of critical patient care competence of studens and new professionals.

This transition from nursing student to nurse can be stressful because, according to Marrero-Gonzalez, they leave a “safe environment” and move into the real world of work, a fact that affects patient safety and the quality of their care [

30].

In relation to new professionals and students on healthcare aid contract, our data showed that the lowest scores in the COM-VA

© were obtained in those competences and competency elements that are related to the lack of theoretical and practical knowledge in relation to deal with critical ill patients and their care. This was expected as the 45.4% of the participants in the study have no professional experience in critical ill patient, especially in the comprehension of the environment and the analysis of the situation in order to take decisions [

31]. In this sense, most of the

ICU recently arrived nurses

and students feel anxiety and fear due to lack of skill and/or knowledge of specific techniques, service's organization and the diseases treated [

32]. Thus, according to a review by Cant and Cooper, simulation can imitate the reality of patient care and contributes to graduate and nursing students’ learning by improving their knowledge and also enhancing their acquisition of clinical skills, efficacy, and self-confidence [

33].

5. Limitations

This study was limited in one sense. The sample was small but has obtained statistically significant results. The study is predominantly female, an aspect that may have influenced the results.

6. Conclusions

The study concludes that the students on placement perceive a higher degree of security in their approach to critical ill patients and obtain higher scores of the COM-VA© from their mentors than others participants.

The presence of the mentor may be influencing how students on placement and mentors perceive the reality about critical patient care, affecting their self-perception in terms of safety and level of competence.

With a view to future studies, strategies such as the use of clinical simulation could help new students and professionals to improve their competences and self-perceptions in dealing with critical ill patients. The use of this methodology would allow them to reach a level of competent execution as well as autonomy in making decisions without the presence of the figure of the mentor, while allowing them to better modulate their self-perception in relation to this patient. The fact of having these simulated experiences could allow professionals and students to shorten the time spent between levels of competence as prepare them to better face future pandemics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P.-C., E.M.-S., M.F.J.-H.; methodology, E.P.-C., E.M-S., M.FJ.-H.; validation, E.P.-C., E.M.-S., M.F.J-H., J.F.-S., P.C.-M. and E. G.-M.; formal analysis, E.P.-C., E.M-S., M.F.J-H. and J.F.-S.; investigation, E.P.-C., E.M-S., M.F.J-H., P.C.-M. and E. G.-M.; writing—original draft, E.P.-C.; writing—review and editing, E.P.-C., E.M-S., M.F.J-H., J.F.-S., P.C.-M. And E.G.-M.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Research with Medicines (CEIm) of the Pere Virgili Health Research Institute (IISPV) (256/2020) and the respective managements of the participating centers, and authorization was also obtained from the author of the COM-VA© questionnaire for its use. The research was carried out in accordance with the rules of the Helsinki Declaration.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the students of the Rovira and Virgili University and professionals of Hospital Tortosa Verge de la Cinta for participating in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. 2020; Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---20-march-2020.

- Xiong Y, Peng L. Focusing on health-care providers’ experiences in the COVID-19 crisis. Lancet Glob Heal [Internet]. 2020 Jun 1 [cited 2022 Nov 5];8(6):e740. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7190304/.

- BOE. Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 de marzo, por el que se declara el estado de alarma para la gestión de la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19. BOE [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2020-3692.

- Raurell-Torredà M. Gestión de los equipos de enfermería de UCI durante la pandemia COVID-19. Enfermería Intensiva [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 May 8];31(2):49–51. Available from: www.elsevier.es/ei.

- La Presidencia M DE, Con Las Cortes Memoria Democrática RY. I. Disposiciones Generales Ministerio de la Presidencia, Relaciones con las Cortes y Memoria Democrática. BOE [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 May 9];(43):15667–80. Available from: https://www.boe.es.

- Huang L, Lei W, Xu F, Liu H, Yu L. Emotional responses and coping strategies in nurses and nursing students during Covid-19 outbreak: A comparative study. PLoS One [Internet]. 2020 Aug 1 [cited 2022 May 9];15(8):e0237303. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0237303.

- Swift A;, Banks L;, Baleswaran A;, Cooke N;, Little C;, Mcgrath L;, et al. COVID-19 and student nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(18):3111–4.

- Sánchez, I., De la Torre, A., Somoza, J., Sobrino, J. B., & Caparrós JP. Unidad de cuidados intensivos: Estándares y recomendaciones. Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social. 2010.

- Gómez M. Evaluación de competencias en el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior (Tesis doctoral) [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2022 Mar 25]. Available from: https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/21343/.

- Benner, P. Using the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition to Describe and Interpret Skill Acquisition and Clinical Judgment in Nursing Practice and Education. Bull Sci Technol Soc. 2004;24(3):188–99.

- Marañón AA, Estorach Querol MJ, Ferrer Francés S. La enfermera experta en el cuidado del paciente crà tico segÃon Patricia Benner. Enfermería intensiva [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2022 Jul 28];22(3):112–6. Available from: www.elsevier.es/ei.

- Carrillo AJ, Paula A, Martínez C, Steffany P, Taborda Sánchez C. Aplicación de la Filosofía de Patricia Benner para la formación en enfermería Application of Patricia Benner’s Philosophy in nursing training. Rev Cubana Enferm. 2018;34(2):421–32.

- Lopera Betancur, MA. Nursing care of patients during the dying process: a painful professional and human function. Investig y Educ en enfermería. 2015;33(2):297–304.

- María Clara Quintero, L. Directrices para la enseñaza de enfermería en la educación superior. 2007;7:5997.

- Helena S, Camelo H. Professional competences of nurse to work in Intensive Care Units: an integrative review. 2012 [cited 2022 May 8];20(1):192–200. Available from: www.eerp.usp.br/rlaewww.eerp.usp.br/rlae.

- González-Méndez MI, López-Rodríguez L. Seguridad y calidad en la atención al paciente crítico. Enfermería Clínica [Internet]. 2017 Mar 1 [cited 2022 May 11];27(2):113–7. Available from: https://www-sciencedirect-com.sabidi.urv.cat/science/article/pii/S1130862117300098?via%3Dihub.

- Eulàlia Juvé M, Huguet M, Monterde D, José Sanmartín M, Martí N, Cuevas B, et al. Marco teórico y conceptual para la definición y evaluación de competencias del profesional de enfermería en el ámbito hospitalario. Parte I. Nurs (Ed española) [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2021 Nov 1];25(4):56–61. Available from: http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/handle/2445/34003.

- Martínez-Segura E. Family caregivers View project Seguridad del paciente View project. 2017 [cited 2022 May 15]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317318102.

- Hill E, Abhayasinghe K. Factors which influence the effectiveness of clinical supervision for student nurses in Sri Lanka: A qualitative research study. Nurse Educ Today [Internet]. 2022 Jul [cited 2022 May 25];114:105387. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S026069172200123X.

- Garcia TR, Nóbrega MML da. Contribuição das teorias de enfermagem para a construção do conhecimento da área. Rev Bras Enferm. 2004;57(2):228–32.

- Waldner MH, Olson JK. Taking the Patient to the Classroom: Applying Theoretical Frameworks to Simulation in Nursing Education. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2007;4(1):18-Article18.

- Escobar-Castellanos B, Jara Concha P. Filosofía de Patricia Benner, aplicación en la formación de enfermería: propuestas de estrategias de aprendizaje. Educación [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2021 Nov 1];28(54):182–202. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?pid=S1019-94032019000100009&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt.

- Sharif F, Masoumi S. A qualitative study of nursing student experiences of clinical practice. 2005. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6955/4/6.

- Vizcaya-Moreno MF, Pérez-Cañaveras RM, Jiménez-Ruiz I, de Juan J. Student nurse perceptions of supervision and clinical learning environment: A phenomenological research study. Enferm Glob. 2018;17(3):319–31.

- Warne T, Johansson U-B, Papastavrou E, Tichelaar E, Tomietto M, den Bossche K Van, et al. An exploration of the clinical learning experience of nursing students in nine European countries. Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30(8):809–15.

- Carrillo Algarra AJ, García Serrano L, Cárdenas Orjuela CM, Díaz Sánchez IR, Yabrudy Wilches N. La filosofía de patricia benner y la práctica clínica. Enferm Glob [Internet]. 2013 Oct 5 [cited 2021 Oct 12];12(4):346–61. Available from: https://revistas.um.es/eglobal/article/view/eglobal.12.4.151581.

- Gónzalez Sánchez A, Juan Jesús Mondéjar Rodríguez IC, Jorge Domingo Ortega Suárez IC, Lic Ana María Sánchez Silva I, Lic Lázara Nélida Silva Polledo I, Lic Yaneisi Sánchez Sierra I Filial de Ciencias Médicas Eusebio Hernández Pérez Matanzas II. Evolución histórica de la tutoría en la formación de profesionales de la enfermería Historical evolution of mentoring in preparing nursing professionals. Rev medica electrónic [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2022 Jul 29];38(4):1684–824. Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1684-18242016000400017&lng=es&nrm=iso.

- Sterner A, Hagiwara MA, Ramstrand N, Palmér L. Factors developing nursing students and novice nurses’ ability to provide care in acute situations. Nurse Educ Pract. 2019;35:135–40.

- Wolff AC, Pesut B, Regan S. New graduate nurse practice readiness: Perspectives on the context shaping our understanding and expectations. Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30(2):187–91.

- Marrero González CM, García Hernández AM. La vivencia del paso de estudiante a profesional en enfermeras de Tenerife (España): un estudio fenomenológico. Ene. 2017;11(1).

- Payne LK. Toward a Theory of Intuitive Decision–Making in Nursing. Nurs Sci Q [Internet]. 2015;28(3):223–8. Available from: https://journals-sagepub-com.sabidi.urv.cat/doi/full/10.1177/0894318415585618.

- Navarro Arnedo JM, Orgiler Uranga PE, de Haro Marín S. Practical nursing guide in the critical patient. Enferm Intensiva [Internet]. 2005;16(1):15–22. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Cant RP, Cooper SJ. Use of simulation-based learning in undergraduate nurse education: An umbrella systematic review [Internet]. Vol. 49, Nurse Education Today. 2017 [cited 2023 Jan 19]. p. 63–71. Available from. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).