Introduction

Antarctic terrestrial arthropods have persisted for millions of years in microhabitats that are ice-free yet have some liquid water available (Convey et al., 2020; Hogg et al., 2014; Hogg & Stevens, 2002). The extent of these microhabitats, and how they are distributed across the landscape, will largely have been determined by the underlying geography and millennial-scale ice sheet dynamics (Caruso et al., 2010), although across much of Antarctica the precise locations of refugia have not been identified. Even during periods of extensive ice cover, such as during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), in some regions species likely survived either on protruding nunataks (Convey et al., 2020), or in association with geothermal features (Fraser et al., 2014), although such features do not appear to explain the persistence of most terrestrial arthropod diversity which is limited to lower altitude coastal areas (Convey et al., 2020). Long-term isolation of arthropod populations across the landscape, with resulting genetic bottlenecks, can ultimately lead to speciation through divergence via genetic drift or mutation (Coyne & Orr, 2004). However, as these isolated habitats in Antarctica are often difficult to access and sample, many locally-unique genetic lineages are likely to await discovery. Mites are the most taxonomically-diverse and widespread microarthropods in Antarctica, with at least 19 species currently recognized from the Ross Sea region alone (Pugh, 1993; Strandtmann, 1967, 1982a;

Table S1). However, estimates of their genetic diversity and levels of divergence among populations remain largely unknown.

Many Antarctic taxa are short-range endemics (Pugh & Convey, 2008), limited to spatially small geographical areas within the continent. The logistical constraints inherent to remote Antarctic fieldwork, which have limited sampling of spatially isolated habitats, also limit the number of species which can be addressed in a single study. This is unfortunate, because taxonomic breadth is essential for gaining a more comprehensive knowledge of diversity across the landscape and for understanding processes of evolution and speciation. The ice-free terrestrial habitats of continental Antarctica have been classified into several biologically-distinct regions (bioregions), known as Antarctic Conservation Biogeographic Regions (ACBRs) (Terauds et al., 2012; Terauds & Lee, 2016). Within these bioregions there are also many smaller-scale landscape barriers to dispersal, further structuring the distribution of species or genetic lineages (Collins et al., 2019; Fanciulli et al., 2001). Studies using DNA-based methods for discriminating species, including cryptic species, have now been carried out for several Antarctic terrestrial invertebrate groups including rotifers (Iakovenko et al., 2015), tardigrades (Kagoshima et al., 2013; Short et al., 2022), mites (Demetras et al., 2010; van Vuuren et al. 2018) and Collembola (Bennett et al., 2016; Carapelli et al., 2020a; Carapelli et al., 2020b; Stevens & Hogg, 2006). However, many of these studies are limited to small spatial scales, covering single bioregions (Liu et al., 2022).

Studies that have incorporated both morphological and genetic data have shown that some Antarctic taxa which were originally thought to be widespread single species often consist of multiple, distinct species. For example, the collembolan Friesea grisea Schäffer with its type locality in sub-Antarctic South Georgia, was widely reported from both maritime and continental Antarctica (Greenslade, 1995; Torricelli et al., 2010). Until recently, this was one of the only micro-arthropod species thought to occur in both the latter regions as well as the sub-Antarctic. However, driven by the application of molecular phylogenetic analyses and also supported by detailed micromorphological assessments, this species has now been redescribed as at least five species (Carapelli et al., 2020a; Carapelli et al., 2020b; Greenslade, 2018; Stevens et al., 2021).

Available genetic markers for species-level assessments include the 5' region of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI-5P) gene (Hebert et al., 2003), which is the most commonly used DNA-based marker, particularly for Antarctic taxa such as Collembola (Beet et al., 2016; McGaughran et al., 2010; Stevens et al., 2006). Unfortunately, this standard “DNA barcoding” region has seen limited sequencing success for mites (e.g., Lv et al., 2014), and previous Antarctic studies of the prostigmatid genus Stereotydeus have used the COI-3P region as an alternative (Brunetti et al., 2021a; Demetras et al., 2010; McGaughran et al., 2008; Stevens & Hogg, 2006). Collectively, these studies have provided evidence of local speciation, including two new species descriptions for S. nunatakis and S. ineffabilis in Victoria Land (Brunetti et al., 2021b). However, the difficulties obtaining specimens from a wider range of remote and isolated locations has limited the geographic coverage of available studies. Further, the absence of COI-5P sequences for Antarctic mites has limited a more widespread comparison with other taxa in Antarctica and elsewhere. Obtaining COI-5P sequences from Antarctic mite taxa would facilitate comparison with existing databases such as the Barcode of Life Datasystems (BOLD) database (Ratnasingham & Hebert, 2007), as well as assist in identifying potentially distinct species and population genetic structure.

One Antarctic mite taxon which would particularly benefit from further attention is Nanorchestes (Endeostigmata), a widespread genus of small-bodied mites that are also found globally (Uusitalo, 2010). Although yet to be subjected to similar molecular studies, the species Nanorchestes antarcticus Strandtmann, 1963 (type locality: Observation Hill, Ross Island, Victoria Land) likely provides an analogous example. It is another species that was originally recorded from both the maritime and continental Antarctic (Strandtmann, 1967). However, Strandtmann (1982c) subsequently described material from the former region as two distinct species, N. berryi and N. gressitti. Four new species were also described from Macquarie Island (Strandtmann, 1982b), and four species from the Ross Sea region (Strandtmann, 1982a), all of which were previously referred to as N. antarcticus. Considering the widespread geographic distribution of this taxon and its acknowledged morphological variability, it is likely that further species-level divergences will be revealed by application of modern molecular approaches.

Here, using integrated morphological and molecular approaches, we assessed the species diversity of terrestrial mites collected from the Ross Sea region of Antarctica, including North Victoria Land (NVL), South Victoria Land (SVL) and the Queen Maud Mountains (QMM), covering a regional latitudinal range of 72-85oS. We also obtained mites from Lauft Island near Mt. Siple (73oS) in West Antarctica and Macquarie Island (54oS) in the sub-Antarctic. We used mitochondrial DNA cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene sequences (COI-5P DNA barcode region) to assess levels of genetic diversity within and among locations, as well as assist with species-level identifications. Our data provide a framework for ongoing studies as well as initiating a reference library for the molecular identification (DNA barcoding) of Antarctic taxa.

Materials and methods

Study area and specimen collection

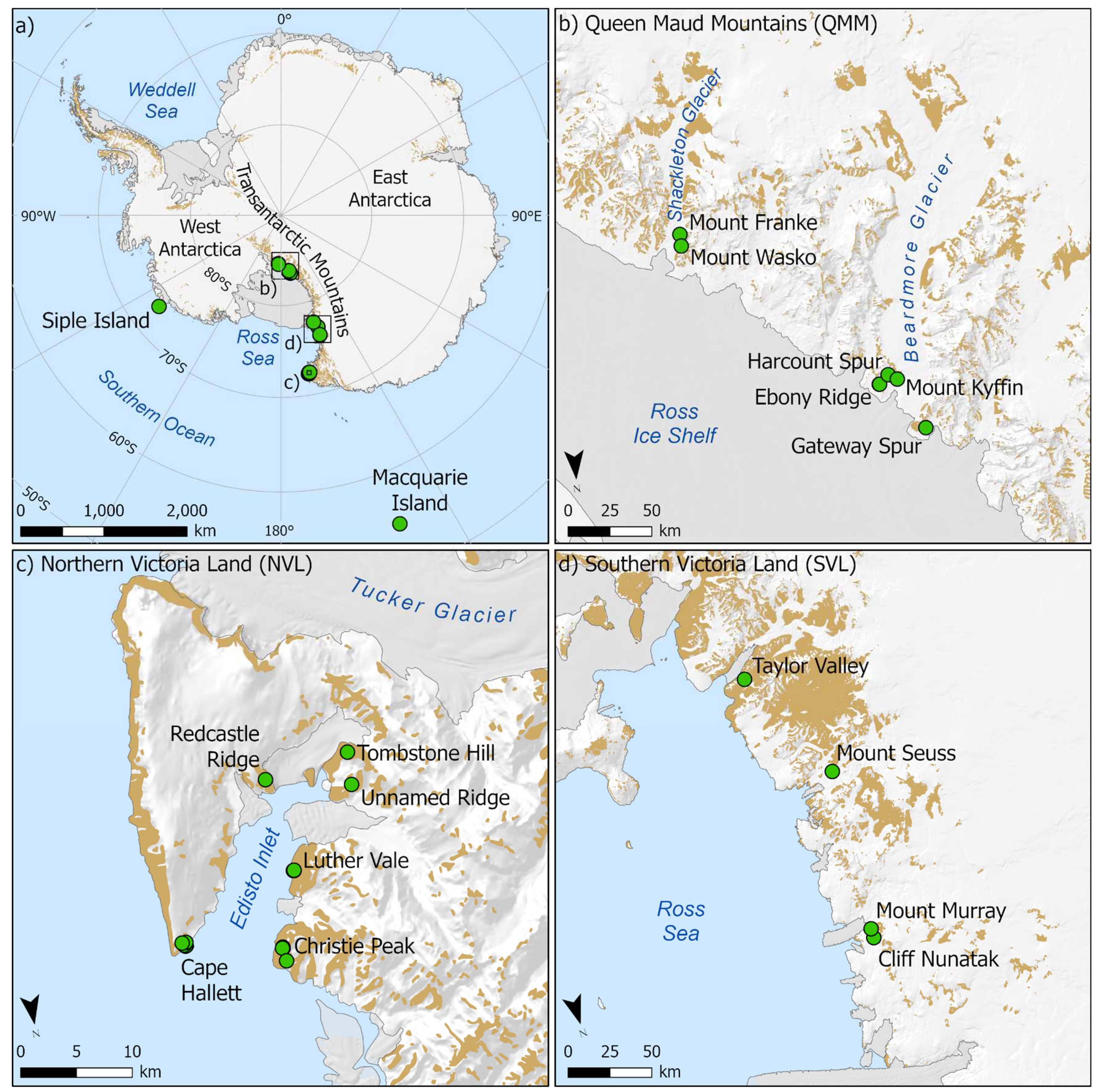

Sampling for free-living mites was undertaken during austral summer field seasons between 2008 and 2018 at 16 locations throughout the Ross Sea region (continental Antarctica), spanning latitudes from 72 to 85

oS, and occupying the longitudinal wedge between 160

oE and 160

oW (

Figure 1). This region includes three biologically-distinct zones, or Antarctic Biogeographic Conservation Regions (ACBRs) (

sensu Terauds et al., 2012; Terauds & Lee, 2016), North Victoria Land (NVL), South Victoria Land (SVL) and the Queen Maud Mountains (QMM, part of the Transantarctic Mountains ACBR (TAM)). The latter represent some of the southern-most terrestrial ice-free habitats in Antarctica. Further samples were obtained in 2017 from the previously unsampled Lauft Island (near Mt. Siple; 73

oS, 127

oW) in West Antarctica and sub-Antarctic Macquarie Island (54

oS, 159

oE). All specimens were collected using modified aspirators (Stevens & Hogg, 2002), pitfall traps (McGaughran et al., 2011), or flotation from soil samples (Freckman & Virginia, 1993) and immediately preserved in 100% ethanol.

Genetic and morphological analyses

For genetic analyses, we used DNA sequences from the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (COI-5P DNA barcode region; Hebert et al., 2003). On return of the specimens from Antarctica, DNA sequencing was undertaken either at the University of Waikato (UoW), New Zealand or the Canadian Centre for DNA barcoding (CCDB), Canada. For total DNA extraction, a REDExtract-NAmp kit (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at the UoW, while a glass fibre plate method (AcroPrep) was used at the CCDB. The DNA barcoding region (658 bp) of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene was amplified using the universal primers HCO2198 and LCO1490 (Folmer et al., 1994) at the UoW, and the combination of HCO2198, LCO1490 together with LepF1 and LepR1 (Hebert et al., 2004) at CCDB. At the UoW, PCR amplifications for each specimen were carried out in 15 µL volumes containing 7.5 µL PCR master mix solution (i-Taq) (Intron Biotechnology), 0.2 µM (0.3 µL) of each primer and 1 µL of DNA extract (unquantified). Thermal cycling conditions were: 94 oC for 5 min followed by 5 cycles (94 oC for 1 min, 48 oC for 1.5 min and 72 oC for 1 min) then 35 cycles (94 oC for 1 min, 52 oC for 1.5 min and 72 oC for 1 min) of denaturation and polymerase amplification, with a final elongation at 72 oC for 5 min. At CCDB, thermal cycling conditions were: 94 oC for 1 min followed by 5 cycles (94 oC for 1 min, 45 oC for 1.5 min and 72 oC for 1.5 min) then 60 cycles (94 oC for 1 min, 50 oC for 1.5 min and 72 oC for 1 min) of denaturation and polymerase amplification, with a final elongation at 72 oC for 5 min. Successful amplification products were cleaned with 0.1 μL exonuclease (EXO) (10 U/μL) and 0.2 μL shrimp alkaline phosphate (SAP) (1 U/μL) (Illustra from GE Healthcare) at 37 oC for 30 min then 80 oC for 15 min at the UoW, or Sephadex at CCDB. Sequencing was carried out in forward and reverse directions using an ABI 3130 at the UoW, or an ABI 3730x1 sequencer at CCDB. Sequences were uploaded to the Barcode of Life Datasystems (BOLD) database. Specimen collection details, photographs, primers used and full sequence data are available from the BOLD database under dataset DS-ANTMIT [doi to be added].

Following DNA extraction, the exoskeletons for some individual specimens were carefully removed from the extract solution and up to five specimens from each cluster/BIN were permanently slide-mounted in polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) mounting medium (BioQuip) for morphological assessment while the remaining specimens were stored in 95% EtOH. The slide mounted specimens were then identified with the aid of a compound microscope using available taxonomic literature (e.g. Strandtmann 1967, 1982a, 1982b). All mounted slides are housed at the Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes (Agriculture and Agrifood Canada) and the remainder of the specimens are housed at the Centre for Biodiversity Genomics (University of Guelph). Identifications were possible for 12 specimens representing five currently recognized species. For any uncertainties with species-level identifications, the more conservative genus-level assignment was used.

Data analyses

In addition to our newly generated sequences, 491 publicly available COI-5P sequences of at least 400 bp in length were downloaded from GenBank in July 2022, for the genera

Nanorchestes,

Eupodes and

Rhagidia. No previous sequences were available for

Stereotydeus or

Coccorhagidia. None of the existing public records were from Antarctica or the sub-Antarctic. To simplify the analyses, we reduced these public records to one sequence per unique BIN or species (n = 26). The final sequence alignment of 156 sequences, each ranging from 404 to 658 bp in length, included our new sequences (n = 130) as well as the 26 representative publicly available sequences (n = 11

Eupodes, n = 10

Nanorchestes, n = 5

Rhagidia). All sequences were aligned in Geneious Prime v2021.2.2 using MUSCLE 3.8.425 and then exported as a PHYLIP file for downstream analyses. A maximum likelihood tree was built using IQ-TREE 2 (Minh et al., 2020) (-nt AUTO -s alignment.phy -st DNA -m MFP -bb 1000 -bnni -alrt 1000) where the best-fit model of TIM+F+R4 chosen according to BIC was inherently applied during the tree-building process. The resulting tree file was then imported to R using read.tree from ggtree v3.1.5.900 (Yu et al., 2017) for visualisation, along with tidyverse v1.3.1 (Wickham et al., 2019) and treeio v1.17.2 (Wang et al., 2020).

Table S2 provides collection details, BINs and BOLD codes for each sequence included in the phylogenetic tree. Haplotype networks were created in R for

Stereotydeus and

Nanorchestes, using pegas v1.1 (Paradis, 2010) and phylotools v0.2.2 (Zhang, 2017), and are available as supplementary material (

Figures S1 and S2).

Sequences from our dataset were grouped at the level of putative species and a barcode gap analysis (Čandek & Kuntner, 2015) was performed using ape v5.6.2 (Paradis & Schliep, 2019), spider v1.5.0 (Brown et al., 2012) and ggplot2 v3.3.5 (Wickham, 2016). Following the genetic analyses, all specimens which occurred within the same BIN as the morphologically identified specimens were also attributed to this taxonomic name following protocols in deWaard et al. (2019).

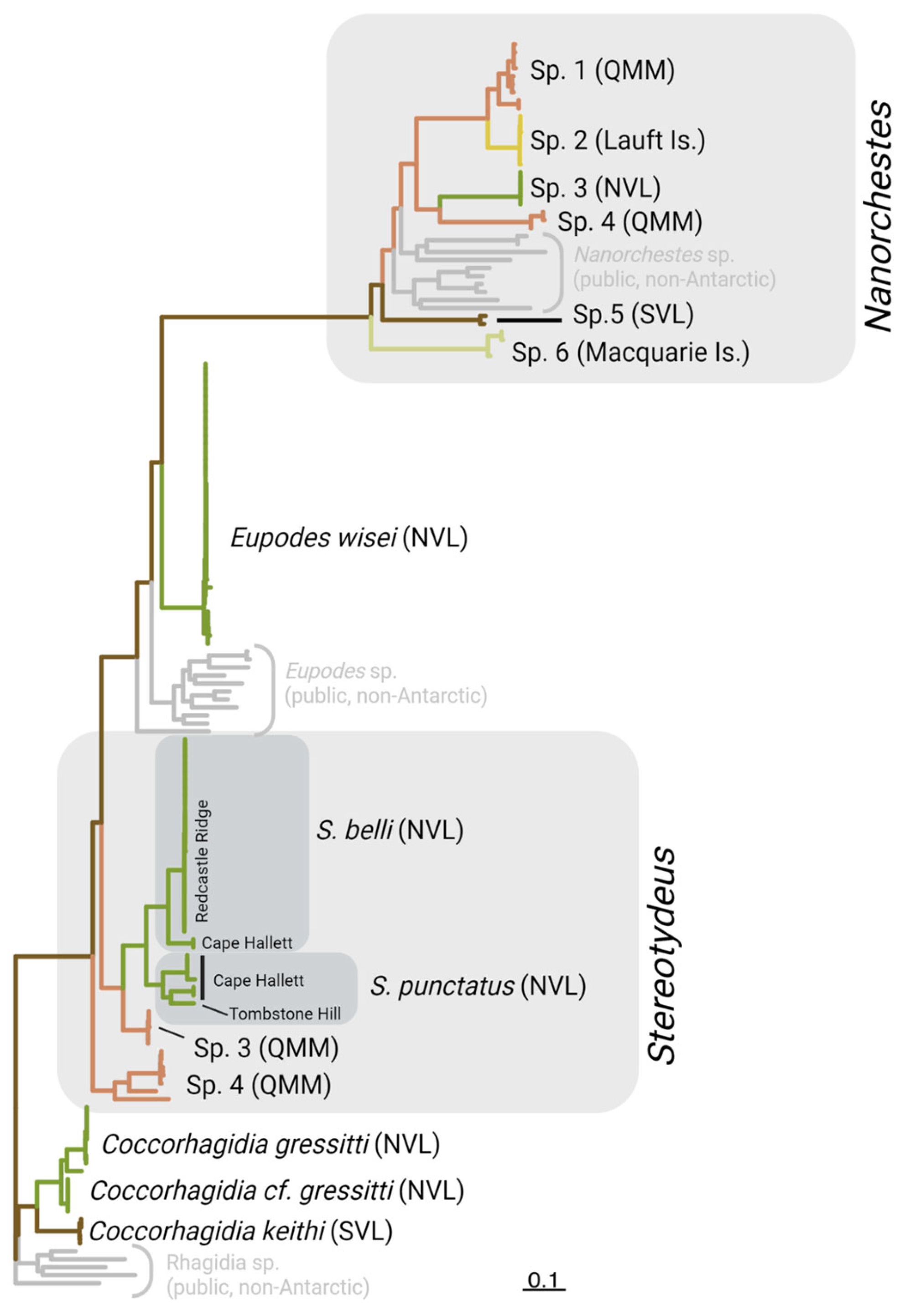

Results

We obtained 130 COI-5P sequences for individual free-living mites collected from 16 locations throughout the Ross Sea region as well as from Lauft and Macquarie Islands. Each specimen was identified morphologically to at least the genus level (Prostigmata:

Coccorhagidia, Eupodes, Stereotydeus; Endeostigmata:

Nanorchestes), and five taxa (12 specimens) were identified to species level (

Coccorhagidia gressitti,

C. keithi,

Eupodes wisei,

Stereotydeus belli and

S. punctatus). A maximum likelihood tree delineated the Antarctic sequences into 13 genetically-distinct clusters, five of which represented the taxonomically-identified species, and none of which contained the publicly-available (i.e., non-Antarctic) COI-5P sequences (

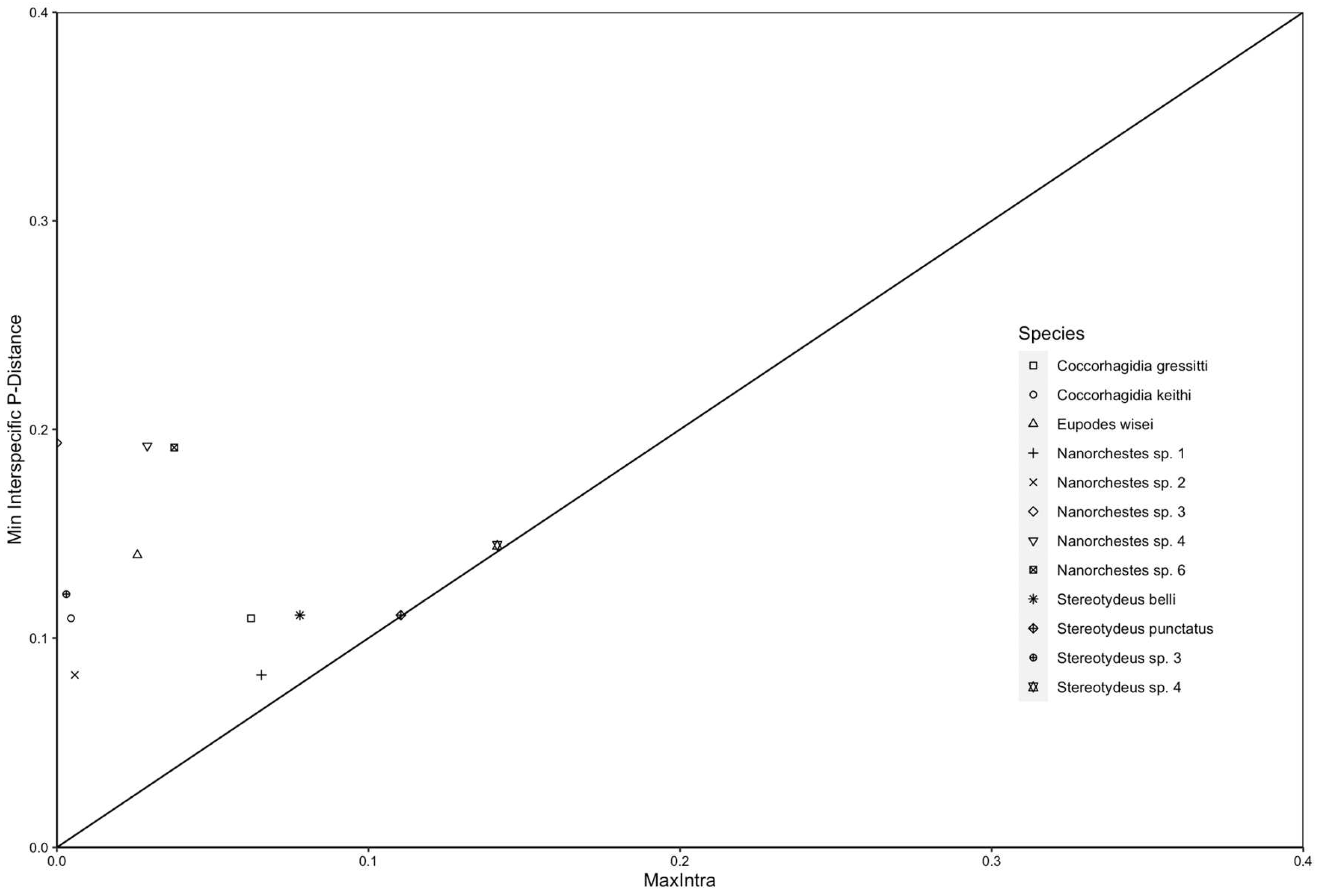

Figures 2 and S3). The 13 clusters were each separated by 8-19% sequence divergence (

Figure 3;

Table 1). Seven of the clusters were represented by a single Barcode Index Number (BIN) and contained < 2.9% sequence divergence, while the remaining six clusters each contained 2-3 BINS and 3.7-14% sequence divergence (

Table 1).

Our genetic data support the taxonomic species designations of

C. keithi and

E. wisei as they were represented by a single BIN each. However, we found multiple BINs (i.e. potential cryptic species) for

C. gressitti, S. belli and

S. punctatus (

Table 1). The three BINs of

C. gressitti (> 6% divergence) were all present at Christie Peak, while the BINs for

S. belli and

S. punctatus were geographically isolated.

Stereotydeus belli and

S. punctatus each had a unique population found only at Cape Hallett, which was genetically distinct from their respective populations found either at Redcastle Ridge (

S. belli; 7.8% divergent) or Tombstone Hill (

S. punctatus; 11.04% divergent).

Three further genetic clusters (

Nanorchestes sp. 1 and sp. 6,

Stereotydeus sp. 4), which were identified morphologically to genus level, also included more than one unique BIN. These BINs were distributed differently across the landscape, depending on the taxon. For instance, some taxa had all BINs present at a single location, while for other taxa unique BINs were each found at a different location. All three BINs of

Nanorchestes sp. 1 (> 6% divergence) were found at Ebony Ridge, and the two BINs for

Nanorchestes sp. 6 (> 3% divergence) were found at the same site on Macquarie Island. In contrast, BINs were unique to single locations for three of the four

Stereotydeus clusters, the exception being Cape Hallett where two BINs for

S. punctatus were present in sympatry (

Table 1).

Based on the morphological and genetic data, we identified two locations at which four or more putative mite species were present (

Table 1). At Cape Hallett in North Victoria Land (72

oS),

C. gressitti,

E. wisei,

S. belli and

S. punctatus were present in sympatry. Two unique BINs for

S. punctatus were also found at Cape Hallett, giving a total of five unique mite BINs at this location. At Mount Franke in the Queen Maud Mountain region (84

oS), two genetic clusters each of

Stereotydeus and

Nanorchestes were present (5 unique BINs in total), representing 4-5 putative species.

Figure 2.

Maximum Likelihood tree including 26 publicly-available COI-5P mite sequences (in grey), as well as our 130 individual mites sequenced from the Ross Sea region which were grouped into 13 genetic clusters (putative species) based on morphological identifications and sequence-based analyses. Each cluster was found in only one of the major biogeographic regions, being restricted to one of the Queen Maud Mountains (QMM), Southern Victoria Land (SVL) or Northern Victoria Land (NVL). The Lauft Island population of Nanorchestes was most similar to one of the QMM species. See the supplementary figures for a more detailed version of the tree. Created with BioRender.com.

Figure 2.

Maximum Likelihood tree including 26 publicly-available COI-5P mite sequences (in grey), as well as our 130 individual mites sequenced from the Ross Sea region which were grouped into 13 genetic clusters (putative species) based on morphological identifications and sequence-based analyses. Each cluster was found in only one of the major biogeographic regions, being restricted to one of the Queen Maud Mountains (QMM), Southern Victoria Land (SVL) or Northern Victoria Land (NVL). The Lauft Island population of Nanorchestes was most similar to one of the QMM species. See the supplementary figures for a more detailed version of the tree. Created with BioRender.com.

Discussion

We assessed the genetic diversity of Antarctic mites from across a wide geographic and taxonomic range in the Ross Sea region. We obtained 130 standard COI-5P DNA barcode sequences (sensu Hebert et al., 2003) from individual mites representing the four genera Nanorchestes, Stereotydeus, Coccorhagidia and Eupodes. The sequences grouped into 13 distinct genetic clusters and a total of 23 unique BINs, some of which were found at only a single location. We also identified locations where multiple clusters or BINs occurred in sympatry, highlighting the potential conservation priorities for protecting sites with high levels of diversity, in keeping with the Antarctic Specially Protected Area priorities outlined by the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (ATCM 1991).

Nanorchestes was the most genetically diverse and widespread genus in our dataset, with six major genetic clusters distributed across ten locations, covering all three ACBRs in the Ross Sea region (Terauds et al., 2012; Terauds & Lee, 2016) as well as Lauft Island and Macquarie Island. Although considerable morphological variation was noted in the original description of Nanorchestes antarcticus (Strandtmann, 1967), this taxon was subsequently divided into multiple distinct species based on detailed morphology (Strandtmann, 1982a,b,c). Based on the geographic range of each of the genetic clusters we found, it is likely that Nanorchestes sp. 3 in NVL is either N. antarcticus or N. lalae, Nanorchestes sp. 5 in SVL could represent either N. bellus, N. lalae or N. antarcticus, and Nanorchestes sp. 1 and 4 in the QMM could represent N. lalae and N. brekkeristae. We also found a genetically distinct cluster (Nanorchestes sp. 2) at Lauft Island near Mt. Siple, a location from where microarthropods including Nanorchestes had not previously been sampled or described. The individuals collected from Lauft Island were genetically most similar to the Nanorchestes found in the QMM region (8% sequence divergence), and we speculate that refugial locations in the QMM may have potentially acted as a source habitat for Lauft Island. Based on available physical modelling and biological evidence (Collins et al., 2020; DeConto & Pollard, 2016) areas in the QMM were likely to have remained ice-free during the last glacial maximum (LGM). In the absence of the present-day Ross Ice Shelf during warmer periods (DeConto & Pollard, 2016), individuals could have dispersed (e.g. via rafting on ocean currents) from the QMM and populated any suitable habitats near Lauft Island until the Ross ice sheet reformed (Pollard & DeConto, 2009). Future morphological and multi-gene analyses focused on individuals from both Lauft Island and the QMM would help distinguish putative species and the evolutionary relationships between the Nanorchestes populations at these two locations.

Stereotydeus belli and S. punctatus are currently known only from the North Victoria Land region, with S. punctatus reported from only a single location, Crater Cirque (Brunetti, Siepel, Convey, et al., 2021). However, we found genetic variants of S. punctatus (three BINs) from two additional locations in NVL, suggesting that even further genetic diversity may exist within this species. Stereotydeus belli and S. punctatus were each represented by multiple BINs and some of these BINs were geographically isolated. Both species had a unique population found only at Cape Hallett and a genetically divergent population (7-11% sequence divergence) at either Tombstone Hill or Redcastle Ridge. Both Redcastle Ridge and Tombstone Hill are located towards the inner end of the Edisto Inlet, presumably isolated from Cape Hallett by local marine currents. Indeed, the isolation of Cape Hallett from other NVL sites has already been recognised for S. belli (Brunetti, Siepel, Convey, et al., 2021).

Patterns of genetic variability among sites in the QMM differed, depending on the taxon considered. We found two genetic clusters of Stereotydeus in the QMM and it is plausible that at least one of these is S. shoupi, the only Stereotydeus species currently described and recorded from this region (Strandtmann, 1967). Demetras et al. (2010) previously addressed the genetic diversity of S. shoupi from the QMM using the alternative COI-3P gene region, and found 8% genetic divergence between the Darwin Glacier (79oS) and Beardmore Glacier (83oS). We also found high levels of genetic divergence in this region, of up to 14% between populations at Beardmore Glacier and the more southerly Shackleton Glacier (84oS), for Stereotydeus sp. 4 (which also could be S. shoupi). Such high levels of genetic variation between the Beardmore and Shackleton Glaciers have also been found for Collembola, with over 13% COI-5P sequence divergence in Antarctophorus subpolaris between these two locations (Collins et al., 2020). In contrast, Nanorchestes had shared BINs between the Beardmore and Shackleton Glacier sites. One possible explanation is that a smaller body size and greater tolerance of lower environmental temperatures for Nanorchestes relative to Stereotydeus (Fitzsimons, 1971) has facilitated increased levels of dispersal among habitats. However, further work (sensu Hawes et al., 2007, 2008; McGaughran et al., 2011) would be required to test this hypothesis.

Stereotydeus sp. 3 was found only in the vicinity of the Shackleton Glacier, and could represent a more southern population for a northern species of Stereotydeus. This has previously been found for the collembolan Gomphiocephalus hodgsoni, a common SVL species that was only recently reported from the QMM region (Collins et al., 2020). Alternatively, Stereotydeus sp. 3 may represent a previously undescribed species unique to the area. Similar to Stereotydeus sp. 3, Tullbergia mediantarctica (Collembola) is also only known from a small area near the mouth of the Shackleton Glacier in the QMM and has previously been identified as potentially vulnerable to extinction due to this narrow distributional range (Collins et al., 2020). We suggest that some of the mite taxa we have identified with narrow geographic distributions may also be vulnerable under future climate scenarios (Lee et al. 2022).

Four genetic clusters were found at Mount Franke, near the Shackleton glacier in the QMM region, probably representing two species of Stereotydeus and two of Nanorchestes. While reductions in biodiversity are often observed with increasing latitude, we found no evidence of this occurring in the Ross Sea region, as a similar level of diversity was found at both QMM and NVL (four genetic clusters each). Caruso et al. (2009) and Colesie et al. (2014) also concluded that levels of diversity were more likely to have been influenced by microhabitat water availability rather than macroclimatic temperature changes associated with latitude in this region. For example, we found six Nanorchestes species clusters each with different distributional ranges, which could be due to different habitat preferences, a feature already hypothesised among other species of this genus from the Antarctic Peninsula region (Convey & Quintana, 1997). Notably, some soils which were exposed during the LGM may provide less suitable habitat today owing to salt accumulation (Lyons et al., 2016; Diaz et al., 2021; Franco et al., 2022). While abiotic factors are usually considered the predominant factor shaping biological communities across continental Antarctica (Hogg et al., 2006), it is possible that additional biotic interactions have remained undetected (Caruso et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2019).

For the five species which were taxonomically-verified, we found 0.46% to 11.04% sequence divergence among populations. Previous genetic studies of Antarctic mites have suggested that they may have differing levels of genetic divergence relative to sympatric Collembola. Possible explanations include ecological factors, such as mites being able to colonize and tolerate newly available habitat before Collembola (and hence longer potential divergence time) or that they have differing rates of evolution (Demetras et al., 2010; McGaughran et al., 2008; Stevens & Hogg, 2006). The Dry Valleys are the most accessible and widely studied ice-free areas in SVL. However, at the time of those studies, only Stereotydeus mollis was known from this area. With the recent description of an additional species in the same area, S. ineffabilis (Brunetti, Siepel, Fanciulli, et al., 2021), we suggest the possibility that the “intraspecific diversity” described for S. mollis by McGaughran et al. (2008) and Stevens & Hogg (2006b) may be the result of genetic differences between S. mollis and S. ineffabilis. Furthermore, all existing mite studies that include DNA-based methods (Brunetti, Siepel, Convey, et al., 2021; Demetras et al., 2010; McGaughran et al., 2008; Stevens & Hogg, 2006) have used the alternative COI-3P gene region. The COI-3P gene region is more suitable for resolving more deeply-rooted phylogenetic relationships and is more reliably amplified and sequenced than the standard COI-5P region which has a particularly low success rate (< 50%) in mites (Otto & Wilson, 2001). Unfortunately, direct comparisons of genetic divergence for mites and Collembola are only likely to be accurate when the same gene region is used. The COI-5P sequences we provide here can now be used as a reference for future comparisons of divergence rates.

In conclusion, based on sequencing of the COI-5P gene region we found between 13 and as many as 23 putative species representing four mite genera, far exceeding previously recognized diversity from this geographic region. Further mite diversity is likely to remain undetected and ongoing and targeted sampling initiatives (e.g. TAM, 2019) will advance this field. Understudied areas that should be specifically targeted include the area south of the Drygalski Ice Tongue (76oS) in NVL, around the Darwin Glacier (80oS) in the Transantarctic Mountains and in the vicinity of the Byrd Glacier (82oS) in the QMM. The standardized DNA sequences (barcodes) we provide serve as a baseline reference library for mites in the Antarctic, and will facilitate future DNA-based studies, including comparative studies among locations and taxa. Future studies are likely to benefit from multi-gene or meta-genomic approaches. Depending on the quality of DNA preservation, future studies may be able to use existing sample collections and thereby limit the need for repeat visits to previously-visited locations, thereby helping to reduce the costs and carbon footprint of conducting research in Antarctica (SCAR, 2023). However, ongoing fieldwork will be required for fresh specimens (non-degraded) which may not have yet been analysed for DNA variability (e.g., Stereotydeus villosus from the maritime Antarctic) or for targeting specific taxa which may not have been collected yet such as the oribatid mite Maudheimia petronia from NVL or Protereunetes maudae (Eupodidae) from QMM (Strandtmann, 1967). Overall, our data suggest that the combination of highly isolated locations and long evolutionary timescales have resulted in high levels of genetic differentiation and local speciation for mites throughout the Ross Sea region. A fuller understanding of the locally unique and endemic mite taxa of Antarctica, which occupy the most southern terrestrial habitats on Earth, will provide valuable insights into the evolutionary history of the Antarctic landscape.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: List of 19 mite species known from the Ross Sea region and from which area they occur: North Victoria Land (NVL), South Victoria Land (SVL) or the Queen Maud Mountains (QMM); Table S2: Extended collection information for each sequence in the phylogenetic tree, including BOLD codes used in the ANTMIT dataset Table S3: Results from the barcode gap analysis; Figure S1: Haplotype network for Stereotydeus specimens; Figure S2: Haplotype network for Nanorchestes specimens Figure S3: Full maximum likelihood tree with additional collection information included in the tip labels, and bootstrap support values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: [I.D.H., B.J.A., D.H.W.]; Methodology: [G.E.C., M.R.Y., B.J.A., SCC, D.H.W., I.D.H.]; Formal analysis and investigation: [G.E.C., M.R.Y.]; Writing - original draft preparation: [G.E.C., I.D.H., P.C., M.R.Y.]; Writing - review and editing: [G.E.C., M.R.Y., P.C., S.L.C., S.C.C., B.J.A., D.H.W., I.D.H.]; Funding acquisition: [I.D.H., S.L.C., S.C.C., B.J.A., D.H.W.]; Resources: [S.L.C., S.C.C., B.J.A., D.H.W., I.D.H.]; Supervision: [I.D.H., P.C.].

Data Availability Statement

All original photographs, specimen and sequence data are available online from the Barcode of Life DataSystems (BOLD) database (www. boldsystems.org) under dataset DS-ANTMIT (doi to be added).

Acknowledgements

Funding and/or logistic support was provided by: New Zealand Antarctic Research Institute (NZARI) and Antarctica New Zealand (AntNZ) to I.D.H. for work in South Victoria Land (SVL) and the Queen Maud Mountains (QMM); PC was supported by NERC core funding to the BAS ‘Biodiversity, Evolution and Adaptation’ Team; S.C.C. and the work in North Victoria Land (NVL) was supported by a grant from NZARI and a Catalyst Award from the New Zealand Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment (MBIE); we thank AntNZ, the Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI) and staff at Jan Bogo Station, for support of the work in NVL; the United States National Science Foundation (ANT-1341736, OPP-1637708) for support of D.H.W., I.D.H. and B.J.A. in SVL and QMM; and the Antarctic Circumpolar Expedition (ACE) for funding to S.L.C. (for Mt. Siple) and the Australian Antarctic Program for funding to S.L.C. (for Macquarie Island). We thank C. Beet, D. Cowan, U. Nielsen, L Sancho, A. Green, P. Roudier, M. Stevens, H. Morgan, B. Storey, M. Shaver-Adams, N. Fierer, M. Diaz and G. Schellens for assistance and company in the field and/or laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ATCM. Annex V to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty. Area Protection and Management. Antarctic Treaty Secretariat, Buenos Aires. 1991. Available online: https://ats.aq/documents/keydocs/vol_1/vol1_9_AT_Protocol_Annex_V_e.pdf.

- Bennett, K.R.; Hogg, I.D.; Adams, B.J.; Hebert, P.D.N. High levels of intraspecific genetic divergences revealed for Antarctic springtails: evidence for small-scale isolation during Pleistocene glaciation. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 119, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.D.J.; Collins, R.A.; Boyer, S.; Lefort, M.; Malumbres-Olarte, J.; Vink, C.J.; Cruickshank, R.H. Spider: An R package for the analysis of species identity and evolution, with particular reference to DNA barcoding. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2012, 12, 562–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunetti, C.; Siepel, H.; Convey, P.; Fanciulli, P.P.; Nardi, F.; Carapelli, A. Overlooked Species Diversity and Distribution in the Antarctic Mite Genus Stereotydeus. Diversity 2021, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, C.; Siepel, H.; Fanciulli, P.P.; Nardi, F.; Convey, P.; Carapelli, A. Two New Species of the Mite Genus Stereotydeus Berlese, 1901 (Prostigmata: Penthalodidae) from Victoria Land, and a Key for Identification of Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic Species. Taxonomy 2021, 1, 116–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čandek, K.; Kuntner, M. DNA barcoding gap: reliable species identification over morphological and geographical scales. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2014, 15, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carapelli, A.; Cucini, C.; Fanciulli, P.P.; Frati, F.; Convey, P.; Nardi, F. Molecular Comparison among Three Antarctic Endemic Springtail Species and Description of the Mitochondrial Genome of Friesea gretae (Hexapoda, Collembola). Diversity 2020, 12, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapelli, A.; Greenslade, P.; Nardi, F.; Leo, C.; Convey, P.; Frati, F.; Fanciulli, P.P. Evidence for Cryptic Diversity in the “Pan-Antarctic” Springtail Friesea antarctica and the Description of Two New Species. Insects 2020, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, T.; Hogg, I.D.; Bargagli, R. Identifying appropriate sampling and modelling approaches for analysing distributional patterns of Antarctic terrestrial arthropods along the Victoria Land latitudinal gradient. Antarct. Sci. 2010, 22, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, T.; Hogg, I.D.; Carapelli, A.; Frati, F.; Bargagli, R. Large-scale spatial patterns in the distribution of Collembola (Hexapoda) species in Antarctic terrestrial ecosystems. J. Biogeogr. 2009, 36, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, T.; Hogg, I.D.; Nielsen, U.N.; Bottos, E.M.; Lee, C.K.; Hopkins, D.W.; Cary, S.C.; Barrett, J.E.; Green, T.G.A.; Storey, B.C.; et al. Nematodes in a polar desert reveal the relative role of biotic interactions in the coexistence of soil animals. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colesie, C.; Green, T.G.A.; Türk, R.; Hogg, I.D.; Sancho, L.G.; Büdel, B. Terrestrial biodiversity along the Ross Sea coastline, Antarctica: lack of a latitudinal gradient and potential limits of bioclimatic modeling. Polar Biol. 2014, 37, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.E.; Hogg, I.D.; Convey, P.; Barnes, A.D.; McDonald, I.R. Spatial and Temporal Scales Matter When Assessing the Species and Genetic Diversity of Springtails (Collembola) in Antarctica. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.E.; Hogg, I.D.; Convey, P.; Sancho, L.G.; Cowan, D.A.; Lyons, W.B.; Adams, B.J.; Wall, D.H.; Green, T.G.A. Genetic diversity of soil invertebrates corroborates timing estimates for past collapses of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 22293–22302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convey, P.; Biersma, E.M.; Casanova-Katny, A.; Maturana, C.S. Refuges of Antarctic diversity. In Past Antarctica; Elsevier: 2020; pp. 181–200. [CrossRef]

- Convey, P.; Quintana, R. The terrestrial arthropod fauna of Cierva Point SSSI, Danco Coast, northern Antarctic Peninsula; European Journal of Soil Biology: 1997; Volume 33, pp. 19–29.

- Coyne, J.A.; Orr, H.A. Speciation: A catalogue and critique of species concepts. Chapter 19 In Philosophy of Biology: An Anthology; Rosenberg, A., Arp, R., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, England, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- DeConto, R.M.; Pollard, D. Contribution of Antarctica to past and future sea-level rise. Nature 2016, 531, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetras, N.J.; Hogg, I.D.; Banks, J.C.; Adams, B.J. Latitudinal distribution and mitochondrial DNA (COI) variability of Stereotydeus spp. (Acari: Prostigmata) in Victoria Land and the central Transantarctic Mountains. Antarct. Sci. 2010, 22, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaard, J.R.; Levesque-Beaudin, V.; Dewaard, S.L.; Ivanova, N.V.; McKeown, J.T.A.; Miskie, R.; Naik, S.; Perez, K.H.J.; Ratnasingham, S.; Sobel, C.N.; et al. Expedited assessment of terrestrial arthropod diversity by coupling Malaise traps with DNA barcoding. Genome 2019, 62, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.A.; Gardner, C.B.; Welch, S.A.; Jackson, W.A.; Adams, B.J.; Wall, D.H.; Hogg, I.D.; Fierer, N.; Lyons, W.B. Geochemical zones and environmental gradients for soils from the central Transantarctic Mountains, Antarctica. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 1629–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanciulli, P.P.; Summa, D.; Dallai, R.; Frati, F. High levels of genetic variability and population differentiation in Gressittacantha terranova (Collembola, Hexapoda) from Victoria Land, Antarctica. Antarct. Sci. 2001, 13, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, J.M. Temperature and three species of Antarctic arthropods. Pac. Insects Monogr. 1971, 25, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, A.L.C.; Adams, B.J.; Diaz, M.A.; Lemoine, N.P.; Dragone, N.B.; Fierer, N.; Lyons, W.B.; Hogg, I.; Wall, D.H. Response of Antarctic soil fauna to climate-driven changes since the Last Glacial Maximum. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 28, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, C.I.; Terauds, A.; Smellie, J.; Convey, P.; Chown, S.L. Geothermal activity helps life survive glacial cycles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 5634–5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freckman, D.W.; Virginia, R.A. Extraction of nematodes from Dry Valley Antarctic soils. Polar Biol. 1993, 13, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenslade, P. Collembola from the Scotia Arc and Antarctic Peninsula including descriptions of two new species and notes on biogeography. Pol. Pismo Entomol. 1995, 64, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Greenslade, P. An antarctic biogeographical anomaly resolved: the true identity of a widespread species of Collembola. Polar Biol. 2018, 41, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, T.C.; Bale, J.S.; Worland, M.R.; Convey, P. Plasticity and superplasticity in the acclimation potential of the Antarctic mite Halozetes belgicae (Michael). J. Exp. Biol. 2007, 210, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, T.C.; Worland, M.R.; Bale, J.S.; Convey, P. Rafting in Antarctic Collembola. J. Zoöl. 2007, 274, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Cywinska, A.; Ball, S.L.; Dewaard, J.R. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Penton, E.H.; Burns, J.M.; Janzen, D.H.; Hallwachs, W. Ten species in one: DNA barcoding reveals cryptic species in the neotropical skipper butterflyAstraptes fulgerator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14812–14817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, I.D.; Cary, S.C.; Convey, P.; Newsham, K.K.; O’donnell, A.G.; Adams, B.J.; Aislabie, J.; Frati, F.; Stevens, M.I.; Wall, D.H. Biotic interactions in Antarctic terrestrial ecosystems: Are they a factor? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 3035–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, I.D.; Stevens, M.I. Soil fauna of Antarctic Coastal Landscapes. In Geoecology of Antarctic Ice-free Coastal Landscapes; Beyer, L., Boelter, M., Eds.; Chapter 15; Ecological Studies Analysis and Synthesis; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2002; Volume 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, I.D.; Stevens, M.I.; Wall, D.H. Invertebrates. In Antarctic Terrestrial Microbiology; Cowan, D.A., Ed.; Chapter 4; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Iakovenko, N.S.; Smykla, J.; Convey, P.; Kašparová, E.; Kozeretska, I.A.; Trokhymets, V.; Dykyy, I.; Plewka, M.; Devetter, M.; Duriš, Z.; et al. Antarctic bdelloid rotifers: diversity, endemism and evolution. Hydrobiologia 2015, 761, 5–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagoshima, H.; Imura, S.; Suzuki, A.C. Molecular and morphological analysis of an Antarctic tardigrade, Acutuncus antarcticus. J. Limnol. 2013, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Laughlin, D.C.; Bottos, E.M.; Caruso, T.; Joy, K.; Barrett, J.E.; Brabyn, L.; Nielsen, U.N.; Adams, B.J.; Wall, D.H.; et al. Biotic interactions are an unexpected yet critical control on the complexity of an abiotically driven polar ecosystem. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.R.; Terauds, A.; Carwardine, J.; Shaw, J.D.; Fuller, R.A.; Possingham, H.P.; Chown, S.L.; Convey, P.; Gilbert, N.; Hughes, K.A.; et al. Threat management priorities for conserving Antarctic biodiversity. PLOS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.P.; Duffy, G.A.; Pearman, W.S.; Pertierra, L.R.; Fraser, C.I. Meta-analysis of Antarctic phylogeography reveals strong sampling bias and critical knowledge gaps. Ecography 2022, 2022, e06312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Feng, C.; Yuan, X.; Jia, G.; Deng, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; et al. Assessment of four DNA fragments (COI, 16S rDNA, ITS2, 12S rDNA) for species identification of the Ixodida (Acari: Ixodida). Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, W.B.; Deuerling, K.; Welch, K.A.; Welch, S.A.; Michalski, G.; Walters, W.W.; Nielsen, U.; Wall, D.H.; Hogg, I.; Adams, B.J. The Soil Geochemistry in the Beardmore Glacier Region, Antarctica: Implications for Terrestrial Ecosystem History. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaughran, A.; Hogg, I.D.; Convey, P. Extended ecophysiological analysis of Gomphiocephalus hodgsoni (Collembola): flexibility in life history strategy and population response. Polar Biol. 2011, 34, 1713–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaughran, A.; Hogg, I.D.; Stevens, M.I. Patterns of population genetic structure for springtails and mites in southern Victoria Land, Antarctica. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2008, 46, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.C.; Wilson, K. Assessment of the usefulness of ribosomal 18S and mitochondrial COI sequences in Prostigmata phylogeny. In Acarology: Proceedings of the 10th International Congress; CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2001; Volume 100, p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, E. pegas: an R package for population genetics with an integrated-modular approach. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, E.; Schliep, K. ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 2018, 35, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, D.; DeConto, R.M. Modelling West Antarctic ice sheet growth and collapse through the past five million years. Nature 2009, 458, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, P. A synonymic catalogue of the Acari from Antarctica, the sub-Antarctic Islands and the Southern Ocean. J. Nat. Hist. 1993, 27, 323–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, P.J.A.; Convey, P. Surviving out in the cold: Antarctic endemic invertebrates and their refugia. J. Biogeogr. 2008, 35, 2176–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D.N. BOLD: the Barcode of Life Data System (http://www.barcodinglife.org). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, K.; Sands, C.; McInnes, S.; Pisani, D.; Stevens, M.; Convey, P. An ancient, Antarctic-specific species complex: large divergences between multiple Antarctic lineages of the tardigrade genus Mesobiotus. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2022, 170, 107429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.I.; Greenslade, P.; D’haese, C.A. Species diversity in Friesea (Neanuridae) reveals similar biogeographic patterns among Antarctic Collembola. Zoöl. Scr. 2021, 50, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.I.; Hogg, I.D. Expanded distributional records of Collembola and Acari in southern Victoria Land, Antarctica. Pedobiologia 2002, 46, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.I.; Hogg, I.D. Contrasting levels of mitochondrial DNA variability between mites (Penthalodidae) and springtails (Hypogastruridae) from the Trans-Antarctic Mountains suggest long-term effects of glaciation and life history on substitution rates, and speciation processes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 3171–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandtmann, R.W. Terrestrial Prostigmata (trombidiform mites). In Entomology of Antarctica (Antarctic Research Series; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 1967; Volume 10, pp. 51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Strandtmann, R.W. Notes on Nanorchestes. II. Four species from Victoria Land, Antarctica (Acari: Nanorchestidae). Pac. Insects 1982, 24, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Strandtmann, R.W. Notes on Nanorchestes. IV. Four new species from Macquarie Island, Australia (Acari: Endeostigmatides: Nanorchestidae). Pac. Insects 1982, 24, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Strandtmann, R.W. Notes on Nanorchestes. V. Two new species of Nanorchestes (Acari: Nanorchestidae) from the Antarctic Peninsula and South Atlantic islands. Pac. Insects 1982, 24, 252–258. [Google Scholar]

- TAM. 2019. https://tamcamp.

- Terauds, A.; Chown, S.L.; Morgan, F.; Peat, H.J.; Watts, D.J.; Keys, H.; Convey, P.; Bergstrom, D.M. Conservation biogeography of the Antarctic. Divers. Distrib. 2012, 18, 726–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terauds, A.; Lee, J.R. Antarctic biogeography revisited: updating the Antarctic Conservation Biogeographic Regions. Divers. Distrib. 2016, 22, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torricelli, G.; Frati, F.; Convey, P.; Telford, M.; Carapelli, A. Population structure of Friesea grisea (Collembola, Neanuridae) in the Antarctic Peninsula and Victoria Land: evidence for local genetic differentiation of pre-Pleistocene origin. Antarct. Sci. 2010, 22, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uusitalo, M. Terrestrial species of the genus Nanorchestes (Endeostigmata: Nanorchestidae) in Europe. In In Trends in Acarology. In Proceedings of the 12th International Congress; Springer: The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vuuren, B.J.; Lee, J.E.; Convey, P.; Chown, S.L. Conservation implications of spatial genetic structure in two species of oribatid mites from the Antarctic Peninsula and the Scotia Arc. Antarct. Sci. 2018, 30, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-G.; Lam, T.T.-Y.; Xu, S.; Dai, Z.; Zhou, L.; Feng, T.; Guo, P.; Dunn, C.W.; Jones, B.R.; Bradley, T.; et al. Treeio: An R Package for Phylogenetic Tree Input and Output with Richly Annotated and Associated Data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2019, 37, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.A.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Smith, D.K.; Zhu, H.; Guan, Y.; Lam, T.T.Y. ggtree: An r package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2017, 8, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. phylotools: Phylogenetic tools for Eco-phylogenetics (R package version 0. 2.2). 2017.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).