Submitted:

08 January 2023

Posted:

13 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Expression and Signaling Pathways of NGFR/p75NTR in AD

3. NGFR/p75NTR Genetic Variants and AD

4. NGFR/p75NTR as a Biomarker of AD

5. NGFR/p75NTR as a Therapeutic Target for AD

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breijyeh, Z.; Karaman, R. Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, E5789. [CrossRef]

- Goedert, M.; Spillantini, M.G.; Cairns, N.J.; Crowther, R.A. Tau Proteins of Alzheimer Paired Helical Filaments: Abnormal Phosphorylation of All Six Brain Isoforms. Neuron 1992, 8, 159–168. [CrossRef]

- Skaper, S.D. Alzheimer’s Disease and Amyloid: Culprit or Coincidence? Int Rev Neurobiol 2012, 102, 277–316. [CrossRef]

- Lindeboom, J.; Weinstein, H. Neuropsychology of Cognitive Ageing, Minimal Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Vascular Cognitive Impairment. Eur J Pharmacol 2004, 490, 83–86. [CrossRef]

- Altomari, N.; Bruno, F.; Laganà, V.; Smirne, N.; Colao, R.; Curcio, S.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Frangipane, F.; Maletta, R.; Puccio, G.; et al. A Comparison of Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD) and BPSD Sub-Syndromes in Early-Onset and Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2022, 85, 691–699. [CrossRef]

- Laganà, V.; Bruno, F.; Altomari, N.; Bruni, G.; Smirne, N.; Curcio, S.; Mirabelli, M.; Colao, R.; Puccio, G.; Frangipane, F.; et al. Neuropsychiatric or Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD): Focus on Prevalence and Natural History in Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 832199. [CrossRef]

- Abondio, P.; Sarno, S.; Giuliani, C.; Laganà, V.; Maletta, R.; Bernardi, L.; Bruno, F.; Colao, R.; Puccio, G.; Frangipane, F.; et al. Amyloid Precursor Protein A713T Mutation in Calabrian Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Population Genomics Approach to Estimate Inheritance from a Common Ancestor. Biomedicines 2021, 10, 20. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, F.; Laganà, V.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Bruni, A.C.; Maletta, R. Calabria as a Genetic Isolate: A Model for the Study of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2288. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, F.; Malvaso, A.; Canterini, S.; Bruni, A.C. Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 726. [CrossRef]

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The Neuropathological Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Neurodegener 2019, 14, 32. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.V.; Hanson, J.E.; Sheng, M. Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Cell Biol 2018, 217, 459–472. [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Wadhwa, P.K.; Jadhav, H.R. Reactive Astrogliosis: Role in Alzheimer’s Disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2015, 14, 872–879. [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; Khoury, J.E.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease. The Lancet Neurology 2015, 14, 388–405. [CrossRef]

- Müller, U.C.; Deller, T.; Korte, M. Not Just Amyloid: Physiological Functions of the Amyloid Precursor Protein Family. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017, 18, 281–298. [CrossRef]

- Kojro, E.; Fahrenholz, F. The Non-Amyloidogenic Pathway: Structure and Function of Alpha-Secretases. Subcell Biochem 2005, 38, 105–127. [CrossRef]

- Nalivaeva, N.N.; Turner, A.J. Targeting Amyloid Clearance in Alzheimer’s Disease as a Therapeutic Strategy. Br J Pharmacol 2019, 176, 3447–3463. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Xia, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. Targeting Amyloidogenic Processing of APP in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Mol Neurosci 2020, 13, 137. [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Hardy, J.; Blennow, K.; Chen, C.; Perry, G.; Kim, S.H.; Villemagne, V.L.; Aisen, P.; Vendruscolo, M.; Iwatsubo, T.; et al. The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 5481–5503. [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.; Vöglein, J.; Quiroz, Y.T.; Bateman, R.J.; Ghisays, V.; Lopera, F.; McDade, E.; Reiman, E.; Tariot, P.N.; Morris, J.C. Testing the Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis: Prevention Trials in Autosomal Dominant Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimers Dement 2022, 18, 2687–2698. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Lin, D.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, S.; Riaz, M.W.; Fu, N.; Mou, C.; Ye, M.; Zheng, Y. Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: Progress and Challenges. Aging Dis 2022, 13, 1745–1758. [CrossRef]

- Stancu, I.-C.; Vasconcelos, B.; Terwel, D.; Dewachter, I. Models of β-Amyloid Induced Tau-Pathology: The Long and “Folded” Road to Understand the Mechanism. Mol Neurodegener 2014, 9, 51. [CrossRef]

- von Schack, D.; Casademunt, E.; Schweigreiter, R.; Meyer, M.; Bibel, M.; Dechant, G. Complete Ablation of the Neurotrophin Receptor P75NTR Causes Defects Both in the Nervous and the Vascular System. Nat Neurosci 2001, 4, 977–978. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-T.; Lu, X.-M.; Shu, Y.-H.; Xiao, L.; Chen, K.-T. Selection of Human P75NTR Tag SNPs and Its Biological Significance for Clinical Association Studies. Bio-Medical Materials and Engineering 2014, 24, 3833–3839. [CrossRef]

- Underwood, C.K.; Coulson, E.J. The P75 Neurotrophin Receptor. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2008, 40, 1664–1668. [CrossRef]

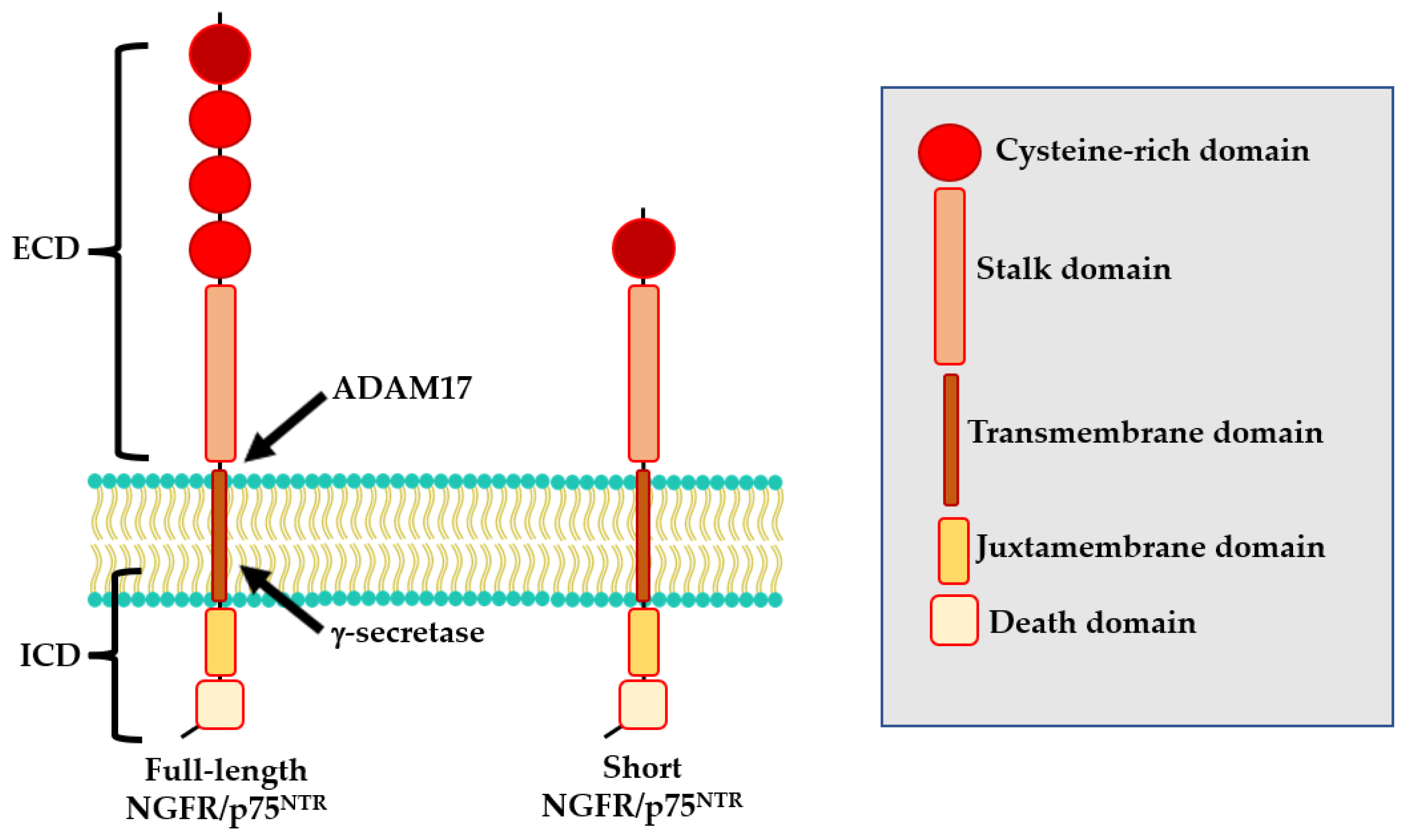

- Skeldal, S.; Matusica, D.; Nykjaer, A.; Coulson, E.J. Proteolytic Processing of the P75 Neurotrophin Receptor: A Prerequisite for Signalling?: Neuronal Life, Growth and Death Signalling Are Crucially Regulated by Intra-Membrane Proteolysis and Trafficking of P75(NTR). Bioessays 2011, 33, 614–625. [CrossRef]

- Casaccia-Bonnefil, P.; Gu, C.; Khursigara, G.; Chao, M.V. P75 Neurotrophin Receptor as a Modulator of Survival and Death Decisions. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1999, 45, 217–224. [CrossRef]

- Meeker, R.; Williams, K. The P75 Neurotrophin Receptor: At the Crossroad of Neural Repair and Death. Neural Regen Res 2015, 10, 721. [CrossRef]

- Sabry, M.A.; Fares, M.; Folkesson, R.; Al-Ramadan, M.; Alabkal, J.; Al-Kafaji, G.; Hassan, M. Commentary: Impact of a Deletion of the Full-Length and Short Isoform of P75NTR on Cholinergic Innervation and the Population of Postmitotic Doublecortin Positive Cells in the Dentate Gyrus. Front Neuroanat 2016, 10, 14. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.D.; Duarte, C.B. P75NTR Processing and Signaling: Functional Role. In Handbook of Neurotoxicity; Kostrzewa, R.M., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2014; pp. 1899–1923 ISBN 978-1-4614-5835-7.

- Ibáñez, C.F. Jekyll-Hyde Neurotrophins: The Story of ProNGF. Trends Neurosci 2002, 25, 284–286. [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.K.; Teng, K.K.; Lee, R.; Wright, S.; Tevar, S.; Almeida, R.D.; Kermani, P.; Torkin, R.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Lee, F.S.; et al. ProBDNF Induces Neuronal Apoptosis via Activation of a Receptor Complex of P75NTR and Sortilin. J Neurosci 2005, 25, 5455–5463. [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.-H.; Lu, X.-M.; Wei, J.-X.; Xiao, L.; Wang, Y.-T. Update on the Role of P75NTR in Neurological Disorders: A Novel Therapeutic Target. Biomed Pharmacother 2015, 76, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Pang, P.T.; Woo, N.H. The Yin and Yang of Neurotrophin Action. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005, 6, 603–614. [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, C.F.; Simi, A. P75 Neurotrophin Receptor Signaling in Nervous System Injury and Degeneration: Paradox and Opportunity. Trends Neurosci 2012, 35, 431–440. [CrossRef]

- Blöchl, A.; Blöchl, R. A Cell-Biological Model of P75NTR Signaling. J Neurochem 2007, 102, 289–305. [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Wu, Z.; Tan, B.; Liu, Z.; Zu, Z.; Wu, X.; Bi, Y.; Hu, X. Ibuprofen Promotes P75 Neurotrophin Receptor Expression through Modifying Promoter Methylation and N6-Methyladenosine-RNA-Methylation in Human Gastric Cancer Cells. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 14595–14604. [CrossRef]

- Vicario, A.; Kisiswa, L.; Tann, J.Y.; Kelly, C.E.; Ibáñez, C.F. Neuron-Type-Specific Signaling by the P75NTR Death Receptor Regulated by Differential Proteolytic Cleavage. Journal of Cell Science 2015, jcs.161745. [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Shi, J.; Xie, F.; Liu, Z.; Yu, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Q. Proteolytic Release of the P75NTR Intracellular Domain by ADAM10 Promotes Metastasis and Resistance to Anoikis. Cancer Research 2018, 78, 2262–2276. [CrossRef]

- Cragnolini, A.B.; Friedman, W.J. The Function of P75NTR in Glia. Trends in Neurosciences 2008, 31, 99–104. [CrossRef]

- Nykjaer, A.; Willnow, T.E.; Petersen, C.M. P75NTR--Live or Let Die. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2005, 15, 49–57. [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.-W.; Chong, Y.S.; Lin, W.; Kisiswa, L.; Sim, E.; Ibáñez, C.F.; Sajikumar, S. Age-Related Changes in Hippocampal-Dependent Synaptic Plasticity and Memory Mediated by P75 Neurotrophin Receptor. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13305. [CrossRef]

- Xuan, A.G.; Long, D.H.; Gu, H.G.; Yang, D.D.; Hong, L.P.; Leng, S.L. BDNF Improves the Effects of Neural Stem Cells on the Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease with Unilateral Lesion of Fimbria-Fornix. Neurosci Lett 2008, 440, 331–335. [CrossRef]

- Xuan, A.G.; Luo, M.; Ji, W.D.; Long, D.H. Effects of Engrafted Neural Stem Cells in Alzheimer’s Disease Rats. Neurosci Lett 2009, 450, 167–171. [CrossRef]

- Tiernan, C.T.; Mufson, E.J.; Kanaan, N.M.; Counts, S.E. Tau Oligomer Pathology in Nucleus Basalis Neurons During the Progression of Alzheimer Disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2018, 77, 246–259. [CrossRef]

- Cade, S.; Zhou, X.-F.; Bobrovskaya, L. The Role of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and the Neurotrophin Receptor P75NTR in Age-Related Brain Atrophy and the Transition to Alzheimer’s Disease. Rev Neurosci 2022, 33, 515–529. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, T.W.; Nathan Spreng, R.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Basal Forebrain Degeneration Precedes and Predicts the Cortical Spread of Alzheimer’s Pathology. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 13249. [CrossRef]

- Boissiere, F.; Faucheux, B.; Ruberg, M.; Agid, Y.; Hirsch, E.C. Decreased TrkA Gene Expression in Cholinergic Neurons of the Striatum and Basal Forebrain of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Exp Neurol 1997, 145, 245–252. [CrossRef]

- Mufson, E.J.; Lavine, N.; Jaffar, S.; Kordower, J.H.; Quirion, R.; Saragovi, H.U. Reduction in P140-TrkA Receptor Protein within the Nucleus Basalis and Cortex in Alzheimer’s Disease. Exp Neurol 1997, 146, 91–103. [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, S.D.; Che, S.; Wuu, J.; Counts, S.E.; Mufson, E.J. Down Regulation of Trk but Not P75NTR Gene Expression in Single Cholinergic Basal Forebrain Neurons Mark the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Neurochem 2006, 97, 475–487. [CrossRef]

- Goedert, M.; Fine, A.; Dawbarn, D.; Wilcock, G.K.; Chao, M.V. Nerve Growth Factor Receptor MRNA Distribution in Human Brain: Normal Levels in Basal Forebrain in Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1989, 5, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ernfors, P.; Lindefors, N.; Chan-Palay, V.; Persson, H. Cholinergic Neurons of the Nucleus Basalis Express Elevated Levels of Nerve Growth Factor Receptor MRNA in Senile Dementia of the Alzheimer Type. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1990, 1, 138–145. [CrossRef]

- Mufson, E.J.; Kordower, J.H. Cortical Neurons Express Nerve Growth Factor Receptors in Advanced Age and Alzheimer Disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992, 89, 569–573. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-Y.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Qin, S.; Xu, H.; Swaab, D.F.; Zhou, J.-N. Increased P75(NTR) Expression in Hippocampal Neurons Containing Hyperphosphorylated Tau in Alzheimer Patients. Exp Neurol 2002, 178, 104–111. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, B.; Ménard, M.; Ito, S.; Gaudet, C.; Dal Prà, I.; Armato, U.; Whitfield, J. Hippocampal Membrane-Associated P75NTR Levels Are Increased in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2012, 30, 675–684. [CrossRef]

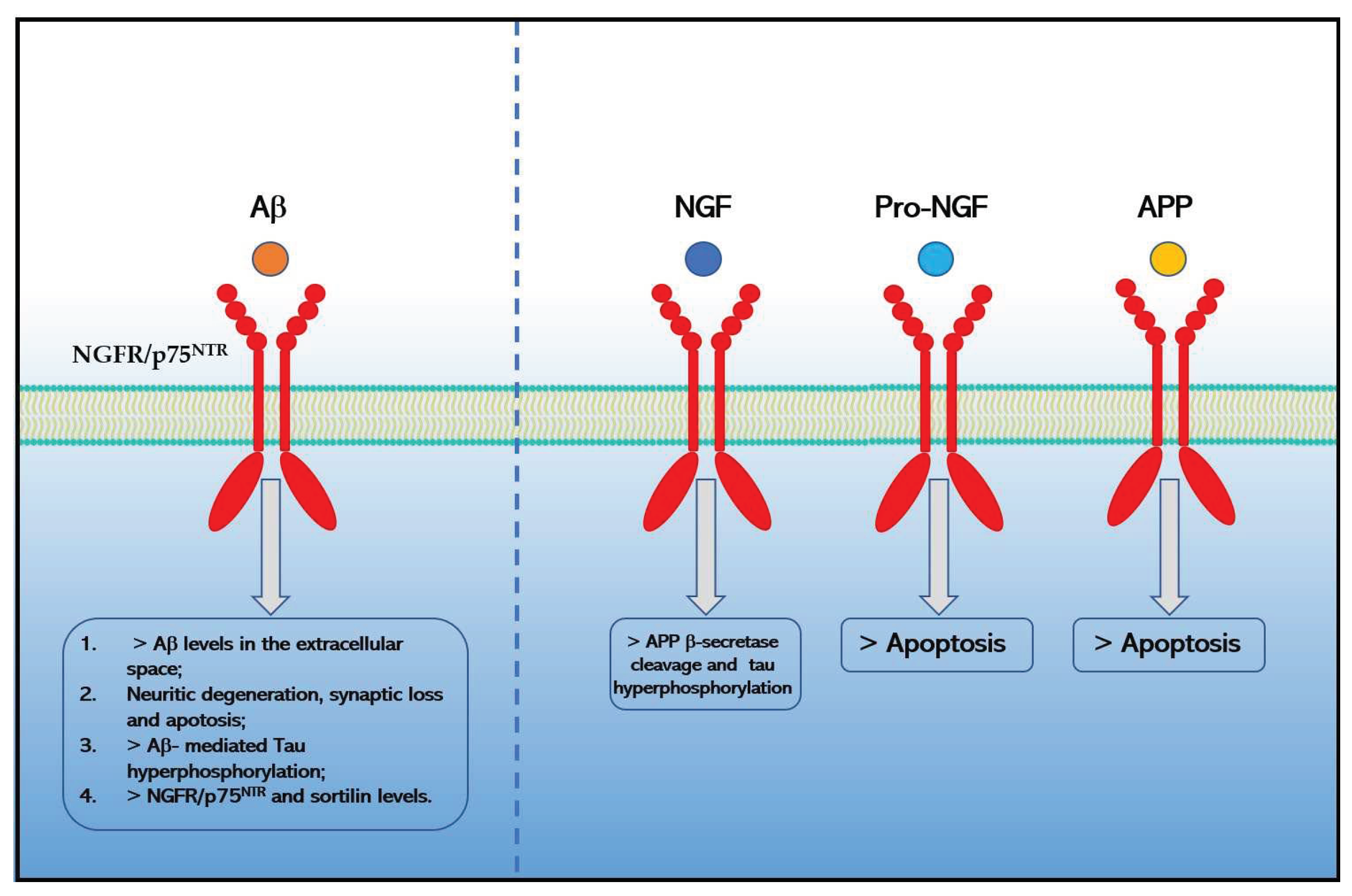

- Rabizadeh, S.; Bitler, C.M.; Butcher, L.L.; Bredesen, D.E. Expression of the Low-Affinity Nerve Growth Factor Receptor Enhances Beta-Amyloid Peptide Toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91, 10703–10706. [CrossRef]

- Sáez, E.T.; Pehar, M.; Vargas, M.R.; Barbeito, L.; Maccioni, R.B. Production of Nerve Growth Factor by Beta-Amyloid-Stimulated Astrocytes Induces P75NTR-Dependent Tau Hyperphosphorylation in Cultured Hippocampal Neurons. J Neurosci Res 2006, 84, 1098–1106. [CrossRef]

- Costantini, C.; Weindruch, R.; Della Valle, G.; Puglielli, L. A TrkA-to-P75NTR Molecular Switch Activates Amyloid Beta-Peptide Generation during Aging. Biochem J 2005, 391, 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Devarajan, S.; Sharmila, J.S. Computational Studies of Beta Amyloid (Aβ42) with P75NTR Receptor: A Novel Therapeutic Target in Alzheimer’s Disease. Adv Bioinformatics 2014, 2014, 736378. [CrossRef]

- Yaar, M.; Zhai, S.; Pilch, P.F.; Doyle, S.M.; Eisenhauer, P.B.; Fine, R.E.; Gilchrest, B.A. Binding of Beta-Amyloid to the P75 Neurotrophin Receptor Induces Apoptosis. A Possible Mechanism for Alzheimer’s Disease. J Clin Invest 1997, 100, 2333–2340. [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, E.; Hashimoto, Y.; Kanekura, K.; Niikura, T.; Aiso, S.; Nishimoto, I. Characterization of the Toxic Mechanism Triggered by Alzheimer’s Amyloid-Beta Peptides via P75 Neurotrophin Receptor in Neuronal Hybrid Cells. J Neurosci Res 2003, 73, 627–636. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Kaneko, Y.; Tsukamoto, E.; Frankowski, H.; Kouyama, K.; Kita, Y.; Niikura, T.; Aiso, S.; Bredesen, D.E.; Matsuoka, M.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Neurohybrid Cell Death Induced by Alzheimer’s Amyloid-Beta Peptides via P75NTR/PLAIDD. J Neurochem 2004, 90, 549–558. [CrossRef]

- Sotthibundhu, A.; Sykes, A.M.; Fox, B.; Underwood, C.K.; Thangnipon, W.; Coulson, E.J. Beta-Amyloid(1-42) Induces Neuronal Death through the P75 Neurotrophin Receptor. J Neurosci 2008, 28, 3941–3946. [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.-L.; Li, W.-W.; Xu, Y.-L.; Gao, S.-H.; Xu, M.-Y.; Bu, X.-L.; Liu, Y.-H.; Wang, J.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, F.; et al. Neurotrophin Receptor P75 Mediates Amyloid β-Induced Tau Pathology. Neurobiol Dis 2019, 132, 104567. [CrossRef]

- Saadipour, K.; Yang, M.; Lim, Y.; Georgiou, K.; Sun, Y.; Keating, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.-R.; Gai, W.-P.; Zhong, J.-H.; et al. Amyloid Beta₁₋₄₂ (Aβ₄₂) up-Regulates the Expression of Sortilin via the P75(NTR)/RhoA Signaling Pathway. J Neurochem 2013, 127, 152–162. [CrossRef]

- Skeldal, S.; Sykes, A.M.; Glerup, S.; Matusica, D.; Palstra, N.; Autio, H.; Boskovic, Z.; Madsen, P.; Castrén, E.; Nykjaer, A.; et al. Mapping of the Interaction Site between Sortilin and the P75 Neurotrophin Receptor Reveals a Regulatory Role for the Sortilin Intracellular Domain in P75 Neurotrophin Receptor Shedding and Apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 43798–43809. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, B.; Gaudet, C.; Ménard, M.; Atkinson, T.; Brown, L.; Laferla, F.M.; Armato, U.; Whitfield, J. Amyloid-Beta Peptides Stimulate the Expression of the P75(NTR) Neurotrophin Receptor in SHSY5Y Human Neuroblastoma Cells and AD Transgenic Mice. J Alzheimers Dis 2010, 19, 915–925. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lee, X.; Shao, Z.; Apicco, D.; Huang, G.; Gong, B.J.; Pepinsky, R.B.; Mi, S. A DR6/P75(NTR) Complex Is Responsible for β-Amyloid-Induced Cortical Neuron Death. Cell Death Dis 2013, 4, e579. [CrossRef]

- Pedraza, C.E.; Podlesniy, P.; Vidal, N.; Arévalo, J.C.; Lee, R.; Hempstead, B.; Ferrer, I.; Iglesias, M.; Espinet, C. Pro-NGF Isolated from the Human Brain Affected by Alzheimer’s Disease Induces Neuronal Apoptosis Mediated by P75NTR. Am J Pathol 2005, 166, 533–543. [CrossRef]

- Podlesniy, P.; Kichev, A.; Pedraza, C.; Saurat, J.; Encinas, M.; Perez, B.; Ferrer, I.; Espinet, C. Pro-NGF from Alzheimer’s Disease and Normal Human Brain Displays Distinctive Abilities to Induce Processing and Nuclear Translocation of Intracellular Domain of P75NTR and Apoptosis. Am J Pathol 2006, 169, 119–131. [CrossRef]

- Fombonne, J.; Rabizadeh, S.; Banwait, S.; Mehlen, P.; Bredesen, D.E. Selective Vulnerability in Alzheimer’s Disease: Amyloid Precursor Protein and P75(NTR) Interaction. Ann Neurol 2009, 65, 294–303. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.-Q.; Jiao, S.-S.; Saadipour, K.; Zeng, F.; Wang, Q.-H.; Zhu, C.; Shen, L.-L.; Zeng, G.-H.; Liang, C.-R.; Wang, J.; et al. P75NTR Ectodomain Is a Physiological Neuroprotective Molecule against Amyloid-Beta Toxicity in the Brain of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Psychiatry 2015, 20, 1301–1310. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.-F.; Wang, Y.-J. The P75NTR Extracellular Domain: A Potential Molecule Regulating the Solubility and Removal of Amyloid-β. Prion 2011, 5, 161–163. [CrossRef]

- He, C.-Y.; Tian, D.-Y.; Chen, S.-H.; Jin, W.-S.; Cheng, Y.; Xin, J.-Y.; Li, W.-W.; Zeng, G.-H.; Tan, C.-R.; Jian, J.-M.; et al. Elevated Levels of Naturally-Occurring Autoantibodies Against the Extracellular Domain of P75NTR Aggravate the Pathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurosci Bull 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hatchett, C.S.; Tyler, S.; Armstrong, D.; Dawbarn, D.; Allen, S.J. Familial Alzheimer’s Disease Presenilin 1 Mutation M146V Increases Gamma Secretase Cutting of P75NTR in Vitro. Brain Res 2007, 1147, 248–255. [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Goh, K.Y.; Wong, L.-W.; Ramanujan, A.; Tanaka, K.; Sajikumar, S.; Ibáñez, C.F. Inactive Variants of Death Receptor P75NTR Reduce Alzheimer’s Neuropathology by Interfering with APP Internalization. EMBO J 2021, 40, e104450. [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Talavera, Y.; Balleza-Tapia, H.; Dolz-Gaitón, P.; Chen, G.; Johansson, J.; Fisahn, A. Ablation of P75NTR Signaling Strengthens Gamma-Theta Rhythm Interaction and Counteracts Aβ-Induced Degradation of Neuronal Dynamics in Mouse Hippocampus in Vitro. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 212. [CrossRef]

- Cozza, A.; Melissari, E.; Iacopetti, P.; Mariotti, V.; Tedde, A.; Nacmias, B.; Conte, A.; Sorbi, S.; Pellegrini, S. SNPs in Neurotrophin System Genes and Alzheimer’s Disease in an Italian Population. J Alzheimers Dis 2008, 15, 61–70. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-C.; Sun, Y.; Lai, L.-C.; Chen, S.-Y.; Lee, W.-C.; Chen, J.-H.; Chen, T.-F.; Chen, H.-H.; Wen, L.-L.; Yip, P.-K.; et al. Genetic Polymorphisms of Nerve Growth Factor Receptor (NGFR) and the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Negat Results Biomed 2012, 11, 5. [CrossRef]

- Matyi, J.; Tschanz, J.T.; Rattinger, G.B.; Sanders, C.; Vernon, E.K.; Corcoran, C.; Kauwe, J.S.K.; Buhusi, M. Sex Differences in Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease Related to Neurotrophin Gene Polymorphisms: The Cache County Memory Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017, 72, 1607–1613. [CrossRef]

- Vacher, M.; Porter, T.; Villemagne, V.L.; Milicic, L.; Peretti, M.; Fowler, C.; Martins, R.; Rainey-Smith, S.; Ames, D.; Masters, C.L.; et al. Validation of a Priori Candidate Alzheimer’s Disease SNPs with Brain Amyloid-Beta Deposition. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 17069. [CrossRef]

- He, C.-Y.; Wang, Z.-T.; Shen, Y.-Y.; Shi, A.-Y.; Li, H.-Y.; Chen, D.-W.; Zeng, G.-H.; Tan, C.-R.; Yu, J.-T.; Zeng, F.; et al. Association of Rs2072446 in the NGFR Gene with the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Amyloid-β Deposition in the Brain. CNS Neurosci Ther 2022, 28, 2218–2229. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.-S.; Bu, X.-L.; Liu, Y.-H.; Wang, Q.-H.; Liu, C.-H.; Yao, X.-Q.; Zhou, X.-F.; Wang, Y.-J. Differential Levels of P75NTR Ectodomain in CSF and Blood in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Novel Diagnostic Marker. Transl Psychiatry 2015, 5, e650. [CrossRef]

- Crispoltoni, L.; Stabile, A.M.; Pistilli, A.; Venturelli, M.; Cerulli, G.; Fonte, C.; Smania, N.; Schena, F.; Rende, M. Changes in Plasma β-NGF and Its Receptors Expression on Peripheral Blood Monocytes During Alzheimer’s Disease Progression. J Alzheimers Dis 2017, 55, 1005–1017. [CrossRef]

- Crooks, A.M.; Meeker, R.B. The New Wave of P75 Neurotrophin Receptor Targeted Therapies. Neural Regen Res 2022, 17, 95–96. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Knowles, J.K.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Arancio, O.; Moore, L.A.; Chang, T.; Wang, Q.; Andreasson, K.; Rajadas, J.; et al. Small Molecule, Non-Peptide P75 Ligands Inhibit Abeta-Induced Neurodegeneration and Synaptic Impairment. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3604. [CrossRef]

- Yaar, M.; Zhai, S.; Panova, I.; Fine, R.E.; Eisenhauer, P.B.; Blusztajn, J.K.; Lopez-Coviella, I.; Gilchrest, B.A. A Cyclic Peptide That Binds P75(NTR) Protects Neurones from Beta Amyloid (1-40)-Induced Cell Death. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2007, 33, 533–543. [CrossRef]

- Yaar, M.; Arble, B.L.; Stewart, K.B.; Qureshi, N.H.; Kowall, N.W.; Gilchrest, B.A. P75NTR Antagonistic Cyclic Peptide Decreases the Size of Beta Amyloid-Induced Brain Inflammation. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2008, 28, 1027–1031. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhan, Z.; Li, X.; Zhou, F.; Xing, A.; Jiang, C.; Chen, Y.; An, L. Beneficial Effects of Sulforaphane Treatment in Alzheimer’s Disease May Be Mediated through Reduced HDAC1/3 and Increased P75NTR Expression. Front Aging Neurosci 2017, 9, 121. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-H.; Wang, Y.-R.; Zhang, T.; Jiao, S.-S.; Liu, Y.-H.; Zeng, F.; Li, J.; Yao, X.-Q.; Zhou, H.-D.; Zhou, X.-F.; et al. Intramuscular Delivery of P75NTR Ectodomain by an AAV Vector Attenuates Cognitive Deficits and Alzheimer’s Disease-like Pathologies in APP/PS1 Transgenic Mice. J Neurochem 2016, 138, 163–173. [CrossRef]

- Massa, S.M.; Xie, Y.; Yang, T.; Harrington, A.W.; Kim, M.L.; Yoon, S.O.; Kraemer, R.; Moore, L.A.; Hempstead, B.L.; Longo, F.M. Small, Nonpeptide P75NTR Ligands Induce Survival Signaling and Inhibit ProNGF-Induced Death. J Neurosci 2006, 26, 5288–5300. [CrossRef]

- Knowles, J.K.; Simmons, D.A.; Nguyen, T.-V.V.; Vander Griend, L.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, T.; Pollak, J.; Chang, T.; Arancio, O.; et al. Small Molecule P75NTR Ligand Prevents Cognitive Deficits and Neurite Degeneration in an Alzheimer’s Mouse Model. Neurobiol Aging 2013, 34, 2052–2063. [CrossRef]

- Simmons, D.A.; Knowles, J.K.; Belichenko, N.P.; Banerjee, G.; Finkle, C.; Massa, S.M.; Longo, F.M. A Small Molecule P75NTR Ligand, LM11A-31, Reverses Cholinergic Neurite Dystrophy in Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Models with Mid- to Late-Stage Disease Progression. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102136. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Tran, K.C.; Zeng, A.Y.; Massa, S.M.; Longo, F.M. Small Molecule Modulation of the P75 Neurotrophin Receptor Inhibits Multiple Amyloid Beta-Induced Tau Pathologies. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 20322. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Liu, H.; Tran, K.C.; Leng, A.; Massa, S.M.; Longo, F.M. Small-Molecule Modulation of the P75 Neurotrophin Receptor Inhibits a Wide Range of Tau Molecular Pathologies and Their Sequelae in P301S Tauopathy Mice. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2020, 8, 156. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).