1. Introduction

To date, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected 533,578,584 people and resulted in 6,315,786 (1.2%) deaths. The recovery rate, however, is very good, with 504,544,346 people recovered (94.6%) [

1]. An unprecedented level of burden has been laid upon public health resources [

2,

3]. The greatest challenge has been not just finding a cure/prevention for this viral disease but dealing with the aggressive host response and long-term sequelae [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The current treatment scenario is far from satisfactory. Complementary medicine, especially individualised medicine (such as homeopathy) focuses on optimisation of the host response during infection and therefore may be an ally in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic [

9,

10]. While many countries do not have specific regulations with regard to the use of homeopathy to treat COVID-19, many others do. India, for example, a country that has adopted homeopathy into the National healthcare system, issued a directive that homeopaths may provide immune boosting remedies to the public and may administer adjuvant homeopathy with conventional drugs in probable/suspected and confirmed cases [

11]. At this time, our pandemic readiness has been questioned, and deeper introspection on our healthcare policies is the need of the hour. During the lockdown, with heavy congestion at hospitals, in most countries, homeopaths’ advice was sought over telephone/video calls, and the remedies were administered remotely. However, homeopathy cannot be assessed as a single system of therapeutics, as the approach to the application of the principles of practice varies greatly. Many “schools of homeopathy” have propounded their own approach for COVID-19 treatment, which may or may not conform to the core principles [

12]. Classical homeopathy is the practice of homeopathy as originally laid down by the founder C F S Hahnemann, where the principle of individualisation and single remedies reign in every scenario, including epidemics [

13].

With such diversity in the comprehension and application of homeopathic principles, we sought to curate data on cases treated with classical homeopathy. Our aim was to bring clarity in terms of the approach and to have sound data to plan future studies and inform policy makers on the feasibility of using classical homeopathy in COVID-19 treatment.

The project was executed by an international team of homeopathic physicians who specialised in the classical approach and belonged to the scientific committee of the International Academy of Classical Homeopathy, Greece. The data were curated carefully and transparently to ensure reproducibility.

2. Materials and Methods

The objective of this study was to curate data on the treatment effect (improvement/no improvement/progress) of classical homeopathy for COVID-19 in a real-world scenario to provide basic data for future scientific investigations. The secondary objectives were to identify the remedies that helped, the main symptoms that were presented and the factors associated with the severity of disease.

Cases were recruited consecutively, irrespective of outcome.

Population: patients diagnosed with COVID-19 of any age, sex, and geographical location. diagnosed as suspected/probable/confirmed case, as determined by RT–PCR or antibody tests for S antigen or nucleocapsid antigen or clinically diagnosed according to the WHO parameters (

Supplementary Material).

Intervention: classical homeopathy – either stand-alone or combined with conventional therapy for COVID as dictated by legality in each country. We did not distinguish the two types at this point.

Comparison: none.

Until the patient was free of symptoms, or a negative PCR test was available.

Primary: improved/not improved/progressed posttreatment

Improved: implying symptomatic, general and/or lab investigation improvement with details provided on the response and time taken for said improvement

Not improved: implying no improvement in the above parameters

Progressed: implying progression of the disease to severe disease or the development of complications of the disease

For mild to moderately severe disease, recovery in 7 days was considered to be improved. Recovery after 7 days was considered to be not improved. For severe disease, up to 15 days to recovery was considered to be improved, and over 15 days was considered to be not improved. This time limit was based on the observations published by researchers to date on the time course for recovery under conventional treatment [

14,

15,

16].

- -

Number of homeopathic remedies required for improvement in each case

- -

Main presenting symptoms and other symptoms

- -

Factors associated with severity and complications – with respect to age, geographical location, time period of infection (wave), comorbidities, fever (yes/no) and fever temperature if available

Case reports that did not furnish complete participant and treatment details or contain an accurate diagnosis were excluded.

Classical homeopaths who were diplomates of International Academy of Classical Homeopathy (IACH) were asked to provide details on cases they treated by filling out a standardised form (

Supplementary Material).

The data gathered were plotted on an Excel sheet, and basic statistical analysis was carried out on the cases that provided complete data to obtain an initial impression. This analysis, however, is not projected to be of any scientific importance yet, as the data at this stage could be confounded and biased in many ways.

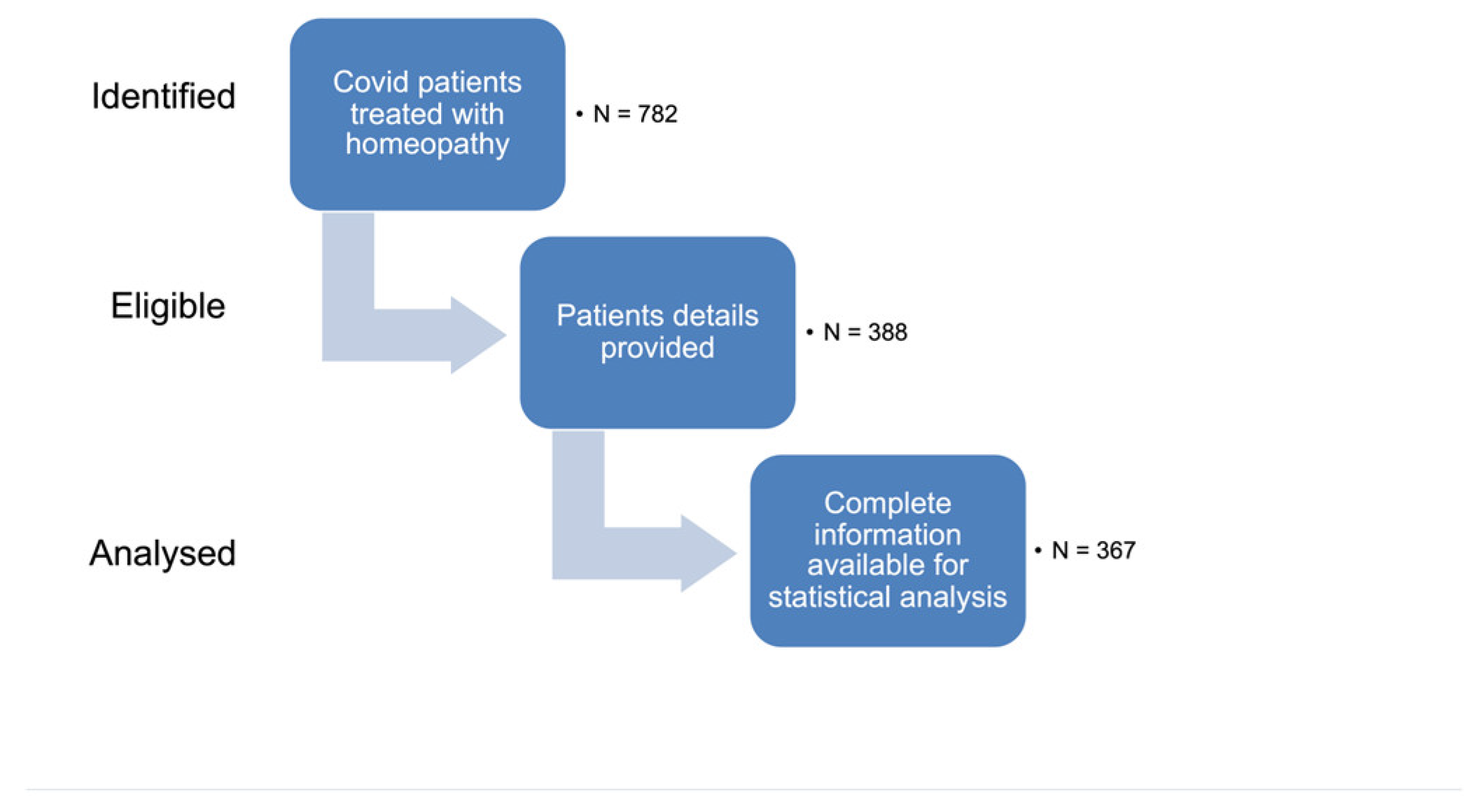

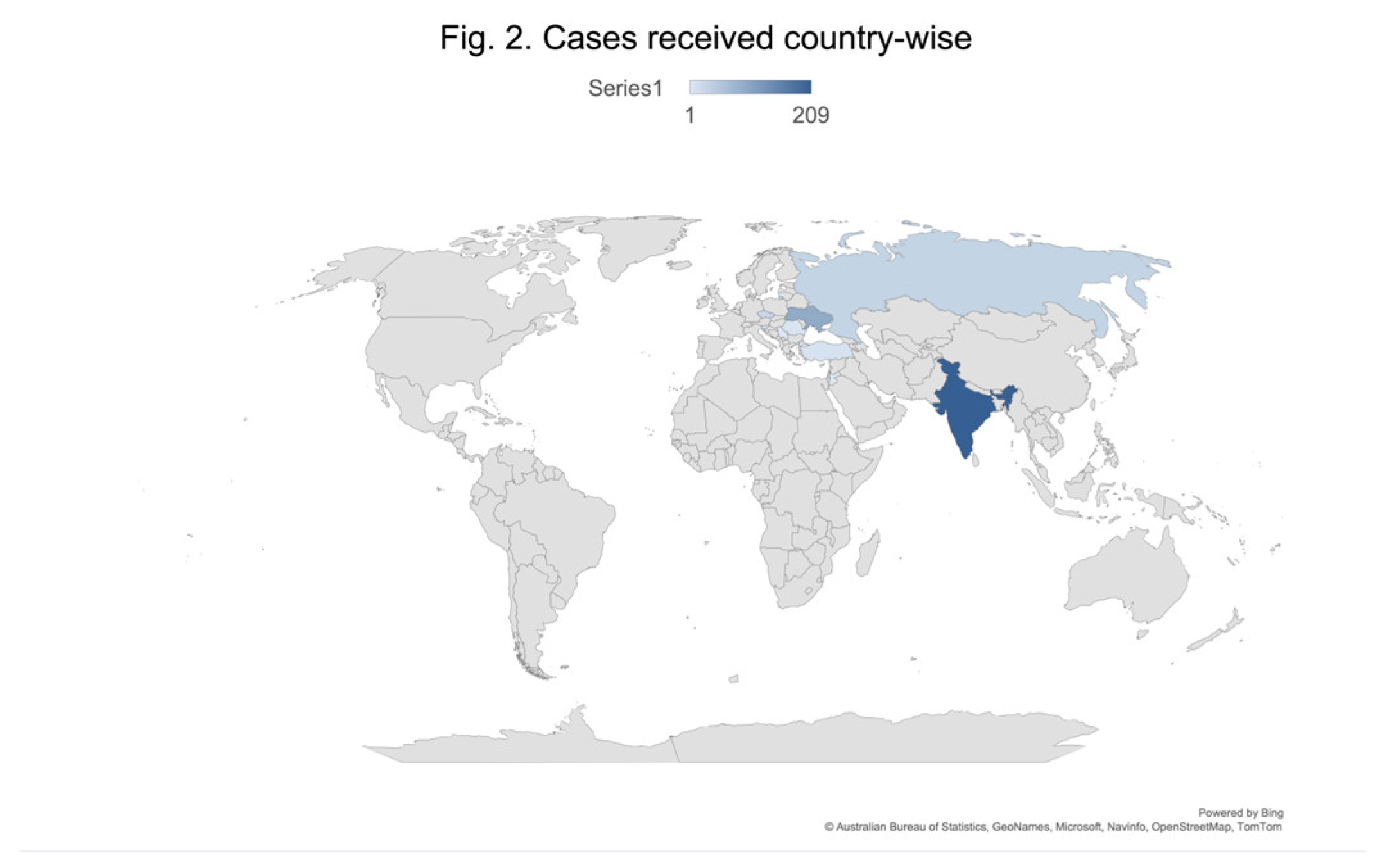

As per the protocol, we sent emails with an example of the case detail format to the diplomates of the IACH. We received replies from India, Jordan, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine. Of the 782 cases claimed to be treated, 388 had detailed enough data to be recorded (

Figure 1). Of the included cases, 209 were from India, 96 were from Ukraine, 32 were from Russia, 28 were from the Czech Republic, 8 were from Slovenia, 7 were from Turkey, 4 were from Romania, 3 were from Jordan, and one was from Serbia (

Figure 2).

For the statistical analysis, we considered only 367 cases, as details on age, sex, and severity of diseases were missing in the other cases (

Figure 1).

Considering potential variability in the individual physician’s case-taking style and bias regarding the response to treatment, we provided a standardised data collection form and requested that the physicians furnish data irrespective of the outcome. Uniformity was achieved by excluding case reports that did not adhere to this format, deeming them incomplete forms (all data forms as returned by the physicians:

Supplementary Material).

All the case reports were independently internally audited by a three-member committee of the scientific team to maximise validity of the treatment effect and ensure the reproducibility and completeness of the data.

3. Results

Initial findings

In the cases considered for statistical analysis (N = 367), the mean age of the participants was 42.75 (± 17.03) years (range: 82 years), and the numbers of males and females were 166 and 201, respectively. The mean follow-up period was 6.5 (SD 5.3) days, with a median of 1 remedy used.

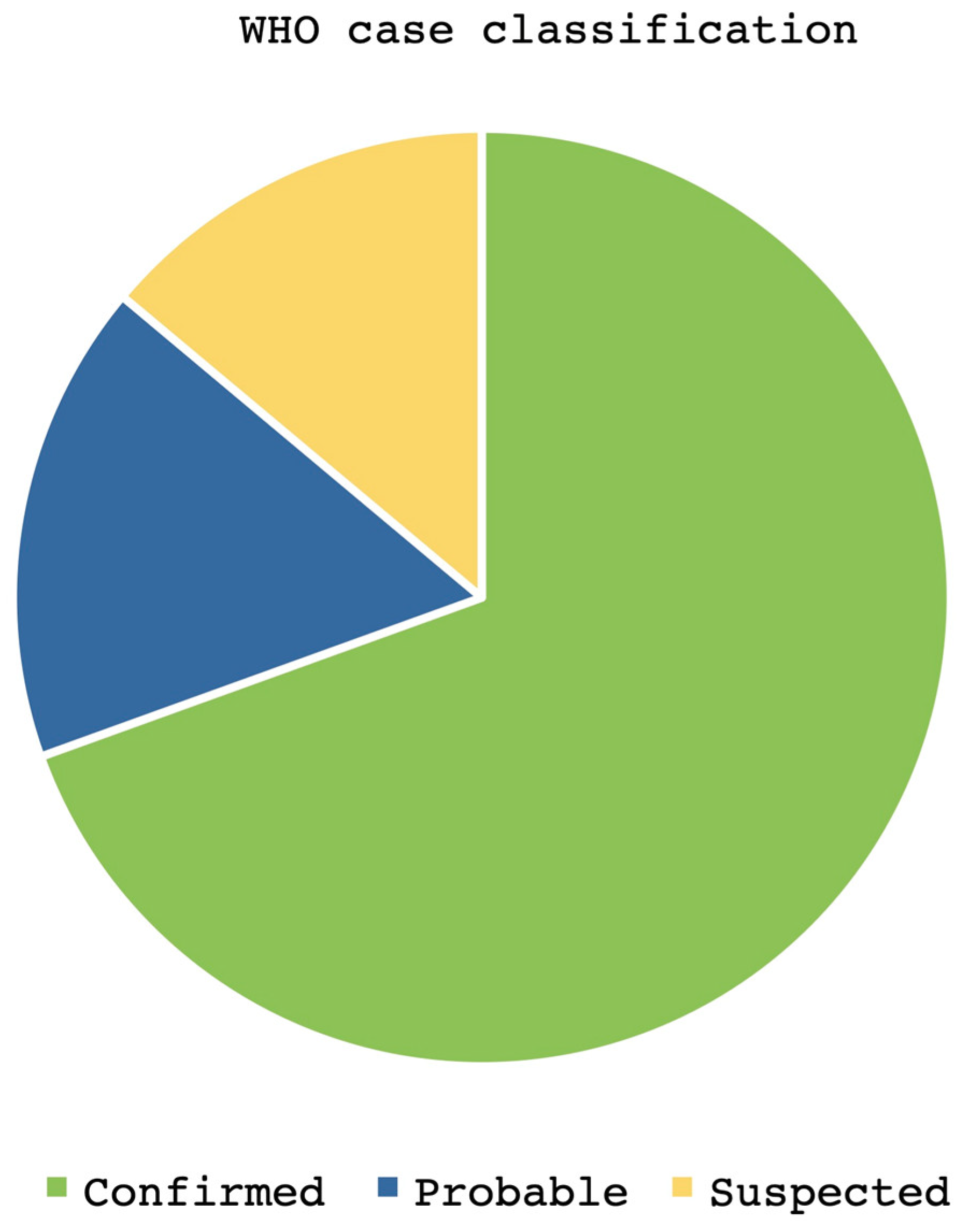

A total of 192 patients were diagnosed by RT–PCR, 111 by the WHO clinical criteria and 64 via retrospective antibodies. According to the WHO criteria, 255 were confirmed cases, 61 were probable cases, and 51 were suspected cases (

Figure 3).

Primary outcome: improvement under classical homeopathy

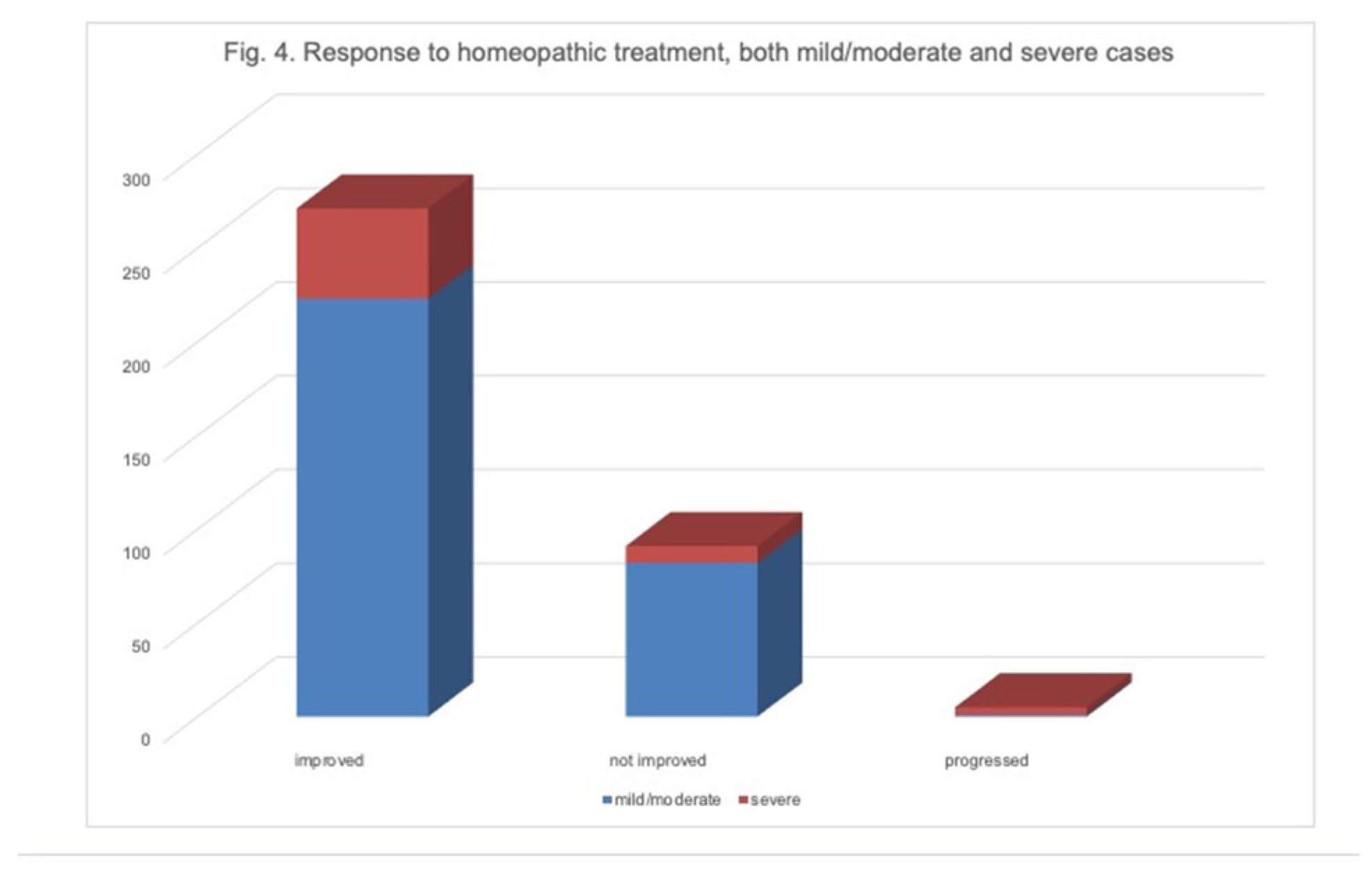

Overall, 271 (73.8%) of the reported cases improved under homeopathic treatment, 91 (24.8%) did not improve, and five cases (1.4%) progressed to become complicated. No deaths while under their care were reported by any homeopaths. However, this is probably because most serious cases were in the ICU, and not accessible for homeopathic treatment. 61 of the 367 were (16.6%) severe disease cases. Of these, 48 improved under homeopathic treatment, 9 cases did not improve, and 4 cases progressed to become complicated (

Figure 4).

We assessed the correlation between improvement with homeopathy and severity of disease using Cramer’s V correlation between two nominal variables, namely, improvement status with 3 levels (disease progressed, no improvement and improvement) and disease severity with 2 levels (mild/moderate and severe). The Cramer’s V value was 0.220 (p<0.01), indicating that there exists a significant moderate positive relationship between improvement status and disease severity, indicating that improvement was moderately more common among patients with severe symptoms than among those with mild symptoms (

Table 2).

Secondary outcome: Main symptoms presented

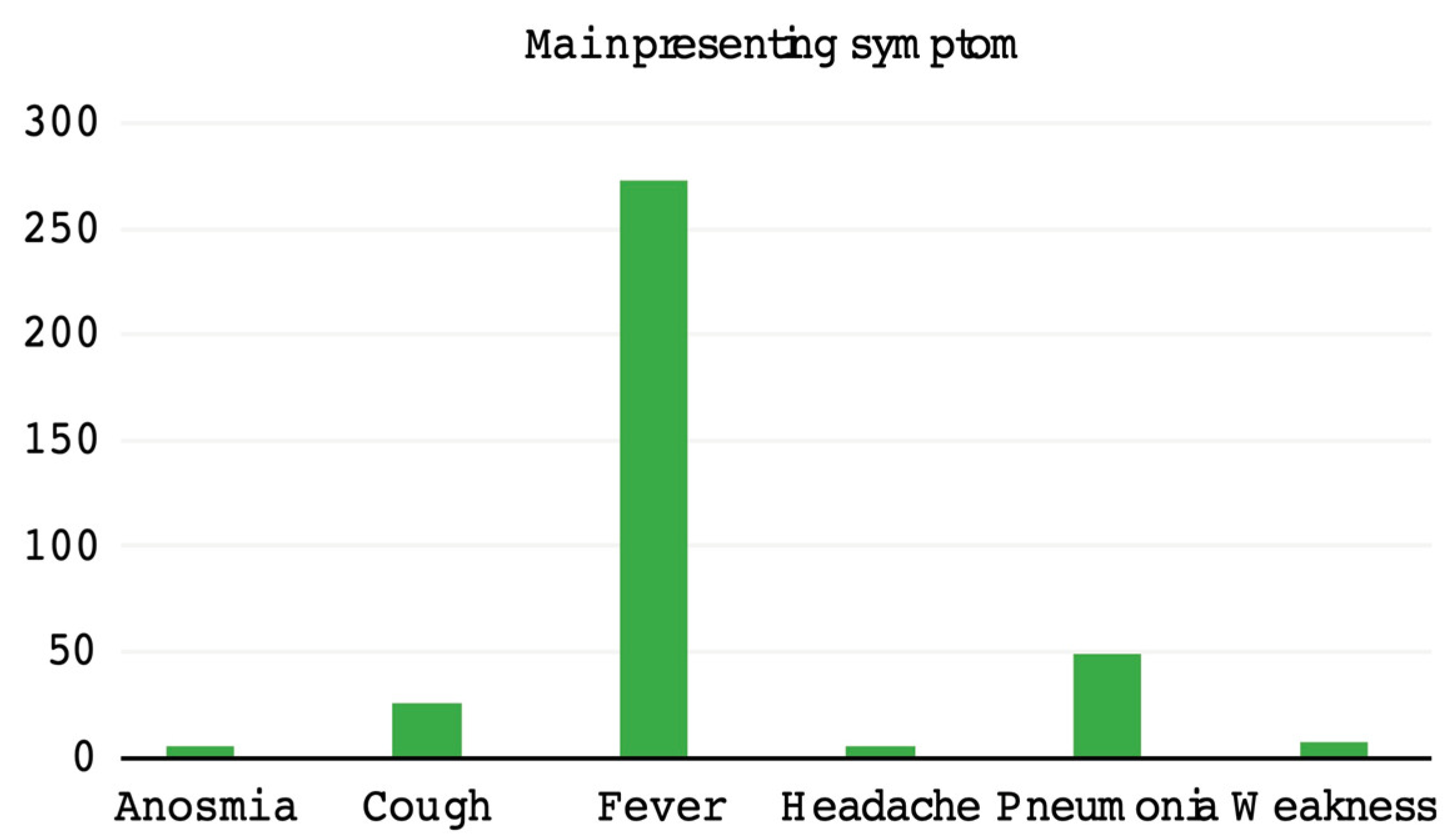

Fever was the most common presenting symptom, with 273 (74.4%) patients presenting with it. Forty-nine patients directly presented with pneumonia on imaging. Where fever was absent, the main presenting symptoms were cough in 26 cases, weakness in 7 cases, anosmia/ageusia in 6 cases and headache in 6 cases (

Figure 5).

Secondary outcome: association of fever with severity of disease

Fever presence was the prime focus of our analysis. For cases with known body temperature at presentation (339), we calculated the Cramer’s V correlation between two nominal variables, namely, improvement status with 3 levels (disease progressed, no improvement and improvement) and presence of fever with 2 levels (absent and present). The Cramer’s V value was found to be 0.167 (p<0.01), indicating that there exists a significant weak positive relationship between the improvement status and the presence of fever, indicating that improvement was slightly more common among patients with fever than among the group without (

Table 3).

We analysed fever according to four categories of temperature to assess the correlation between improvement and temperature range. Fever categories and the number of cases in each range are provided in the

Table 4.

Secondary outcome: association of age and sex with severity of disease

Sex was not associated with any significant difference in response to treatment. It was, however observed, that the Pearson correlation coefficient was -0.146 (p<0.01), indicating a significant negligible positive relationship between the improvement status and age (

Table 5). This means that when the age of the patients increased, the level of improvement decreased (negligibly).

Secondary outcome: Most common remedies used and association of number of remedies with improvement

We plotted the frequency table for the most frequently used remedies (≥10 cases) (

Table 6). It was observed that the most common form of drug used was Arsenicum album, with a total of 103 cases treated. The second most common form of drug used was Bryonia, with a total of 100 cases and the third most common form of drug used was Pulsatilla, with a total of 48 cases. 200C was the most commonly used potency for all these remedies (

Table 6). As the number of remedies prescribed increased, the level of improvement decreased slightly among patients (

Table 7).

Factors associated with improvement under homeopathy

Using the insights from the correlational analyses, a multinomial logistic regression model was constructed for the nominal data, with improvement status as the dependent variable and the significantly correlated variables, such as the number of remedies, presence of fever and disease severity, as independent variables, to predict improvement status.

The model fitting criteria value was 57.664. The significance value is less than 0.01, indicating that the final model fit well. The goodness of fit for the model was calculated, and the Pearson value was 20.679 (p>0.05). The significance value was 0.541 (>0.05), thus indicating that the model was adequately fit.

The pseudo R square values were calculated for the regression model. The Nagelkerke value was 0.311, which means only 31.1% change in improvement status could be attributed to the number of remedies, presence of fever and disease severity, indicating that the studied independent variables are not sufficient to predict improvement status.

When computing the likelihood ratio for the regression model, it was observed that the number of remedies (p<0.01), disease severity (p<0.05) and presence of fever (p<0.05) significantly contributed to improvement status. Parameter estimates for the regression model were not taken into consideration, as the data representations across the three categories of improvement status were not comparable.

The comorbidities were not uniformly available and thus could not be used for correlational analyses.

4. Discussion

Many databases have been created and are actively collecting data on the new pandemic [

17]. There are also many reports on the use of traditional and complementary medicine for COVID-19, including homeopathy [

18,

19]. India has pioneered many research projects on both prophylaxis and treatment of COVID-19 with homeopathy [

20]. However, a database dedicated to this therapy is novel and will go a long way in providing material for investigation in the future.

The preliminary data collected from 9 countries has shown some interesting outcomes. The average age of participants and the influence of age on the severity of infection are slightly different (younger) from those seen in other studies thus far [

21,

22,

23]. This is probably due to the trend of patients opting for homeopathy being in this age range, compared to the general population.

The primary outcome of interest for the analysis was improvement under homeopathic treatment. This was seen to be significant, especially in severe cases (

Figure 4,

Table 2). The mean time required for improvement was 6.5 days. While no deaths were reported, this could be due to the hospitalisation of most severe cases and cessation of homeopathic treatment under such conditions although favourable direction was seen in the few severe cases who continued with homeopathy. The most common remedies used were Arsenicum album, Bryonia and Pulsatilla (

Table 6), which have been recommended by other studies as well [

21]. However, it must be noted that contrary to popular belief among homeopaths, no single remedy (serviceable as prophylaxis and/or treatment) emerged as a “genus epidemicus”. We investigated other parameters associated with improvement under homeopathic treatment as secondary outcomes of interest. Fever was the main presenting symptom/condition in most cases (

Figure 5), as corroborated by many other studies [

21]. The stochastic model of symptom progression also corroborates fever as the first symptom that may arise in COVID-19 [

24], which seems to be the stage at which homeopaths were approached by patients. In the absence of fever, cough and a clinical/laboratory image of pneumonia (without fever) were seen to dominate. Fever is of special interest, as fever is conventionally suppressed during infections [

25], whereas homeopathy promotes a high fever during infection as a part of the efficient acute inflammatory response [

26,

27]. Studies have hitherto shown that the presence of fever may be associated with better outcomes during infection, although the evidence is still lacking in certainty [

25,

28,

29]. In our database, the presence of fever was indeed associated with better prognosis (

Table 3). However, the temperature range did not influence the clinical outcome in the cases presented here (

Table 4). In previous studies, sepsis and COVID-19 were influenced by the temperature trajectory during the sepsis [

30,

31], and it would be interesting to investigate whether the temperature trajectory can influence the clinical outcome of COVID-19 in a similar manner.

The number of homeopathic remedies required was strongly correlated with improvement (

Table 7). This is in keeping with the homeopathic principles of levels of health [

27]. Healthier patients present with stronger and clearer symptoms for homeopathic prescription, and their response is quick and in the right direction. Less healthy patients require a few more remedies in the right sequence to bring them up to the same level of efficient response. If a homeopath makes mistakes in identifying the remedy, the response is delayed, and the number of remedies required will also increase. In either case, improvement is inversely correlated to the number of remedies required [

27].

In this database, not enough information was available regarding the comorbidities in the patients. Hence, we could not analyse the influence of comorbidities on the clinical outcome. This lack of complete information is attributable to telephone consultations, which accounted for the majority of consultations during COVID lockdowns. It will be essential to collect this information for future cases, as studies have shown that comorbidities have an adverse effect on improvement in COVID patients [

5], and it will be necessary to evaluate this in homeopathic treatment scenarios.

At this juncture, only the presence of fever, number of remedies required and severity of disease were significant contributors to the improvement status under homeopathic treatment. The impact of other parameters (age, temperature range, comorbidities, geographical location, period of infection - wave) on homeopathic treatment are yet to be determined.

The objective of this database was to provide a reliable data pool for those interested in further research. There are simply too many confounders to account for in such a scenario, and the authors suggest a thorough study of this database to account for these confounders in their research plans. Some confounders that were apparent to the authors in this database that need to be considered in future data collection plans are as follows:

- i)

Mode of data gathering – the homeopaths gathered data via telephone consultations and in-person at varying times, which may lead to overemphasis or neglect of certain information. Therefore, a distinction needs to be made with regard to the mode of case taking, and a comparison needs to be made about the completeness obtained with these modes.

- ii)

Geographic location – while COVID seems to affect patients in a similar manner globally, there still might be differences in the manner it affects different geographic locations.

- iii)

Time period of data collection – each genetic variant of the virus has been affecting the population in a different manner, and depending on which time period the data were collected the predominant infecting variant may be different. The symptoms and treatment response will likewise vary. Hence, it will be helpful to make a distinction about these. There was a major constraint in some cases that the dates of first consultation were not provided. Collecting these data will be important for research studies.

- iv)

Data on temperature trajectory – a lot is being said about the importance of fever. The authors recognise that presenting temperature alone is not sufficient but that the course of the illness depicts the immune response better. This information needs to be collected for future cases.

- v)

Laboratory parameters – although the lab parameters suggested for COVID-19 cases are similar globally, the availability of such records to patients and homeopaths varies from country to country. This can be overcome by requesting the parameter measurements and recording them meticulously

- vi)

Comorbidities – as outlined before, the method of case taking influences the completeness of the data, and most cases did not detail the comorbidities. This must be overcome, as it is a simple matter of inquiry.

Limitations

This dataset relies heavily on the reporting by homeopathic physicians, introducing a reporting bias, as it is possible that the physicians may not report cases that did not improve or progressed to complications as readily as they report successful cases. Effort was made to brief all the participating physicians in advance on the importance of unbiased reporting to minimise this bias. Second, the difference in the national health policies of the participating countries makes it difficult to attain real uniformity and is a limitation that cannot be overcome. This introduces a selection bias, as those with mild or moderate symptoms from some countries may seek homeopathic treatment, while in others, there is homeopathic treatment for patients in any condition. Some countries had no prohibition on patients seeking homeopathic treatment as stand-alone treatment, while in countries such as India, it was regulated that it could only be given as adjunct therapy. There was also some bias introduced due to the incompleteness of data in over half of the case reports sent in. This was mainly attributable to the telephone/online nature of homeopathic consultation in most cases. These were identified as potential biases and challenges for future studies aimed at investigating the effect of homeopathy in COVID-19. The greatest confounding effect is that of conventional medicines taken along with homeopathy, and at this point, this remains an insurmountable challenge. The aim of this study was to provide data for studies in the future, and a prospective design may help overcome these limitations.

Future direction

Despite the confounding and bias, the data we compiled are impressive. We strongly urge governments to consider providing free reign to homeopathic doctors to deal with COVID cases. Similar appeals have been made by investigators previously [

19]. The severe cases will by default be hospitalised and will not be under homeopathic care, but the burden from mild and moderately severe cases can be significantly alleviated by including homeopaths in care delivery [

32]. Many other epidemics, including viral ones, have responded well to homeopathy since the days of Hahnemann [

10,

19,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]; therefore, there are grounds to reconsider homeopathy in the National Health Systems now. Many investigators have made observations and have already registered protocols that need the support of governments to succeed [

40].

In the future, with permission given for homeopaths to treat, an intensive and refined study design should be applied to overcome the confounding and bias that exist in this database. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are difficult, as patients may not like being deprived of conventional therapy with such a risky pathology. Therefore, a prospective observational study is the best option for homeopathy, and a comparison study can be established with adjunct conventional treatment as well. A greater cooperation between homeopathic organisations may be designed to obtain sufficient evidence. A more elegant study can be devised to obtain evidence of the “genus epidemicus” for homeopaths. Using the levels of health model of Prof. Vithoulkas [

27], a retrospective analysis of remedies indicated in the healthiest COVID patients may be analysed, and evidence towards the possibility of one or few such remedies may be obtained. However, obtaining adequate information will again be a challenge for such a study, and cooperation among homeopaths will be of utmost importance.

COVID-19 seems to attack the immune system more than any other viral disease discovered thus far [

41], and homeopathy, being a system capable of enhancing immune efficiency [

10], must be given a chance to show its efficacy with an appropriate infrastructure in place.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

PH conceived the idea and curated the data along with SM, who also wrote the manuscript and performed the statistical analysis. The ICC are all the physicians who volunteered to send the data for the database, and GV is the guide, auditor and guarantor of the work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the help of Harshitha Narayanaswamy, Vishrutha M, Pooja Dhamodar and Amritha Belagaje for rendering technical help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Worldometer. COVID-19 Corona Virus Pandemic. Dadax. 2021. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Gebru AA, Birhanu T, Wendimu E, et al. Global burden of COVID-19: situational analyis and review. Hum Antibodies 2021, 29, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan CY, Fann JCY, Yang MC, et al. Estimating global burden of COVID-19 with disability-adjusted life years and value of statistical life metrics. J Formos Med Assoc 2021, 120, S106–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederman MS, Richeldi L, Chotirmall SH, Bai C. Rising to the challenge of COVID-19: advice for pulmonary and critical care and an agenda for research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020, 201, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang B, Li R, Lu Z, Huang Y. Does comorbidity increase the risk of patients with covid-19: Evidence from meta-analysis. Aging 2020, 12, 6049–6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller AL, McNamara MS, Sinclair DA. Why does COVID-19 disproportionately affect older people? Aging 2020, 12, 9959–9981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang F, Kream RM, Stefano GB. Long-term respiratory and neurological sequelae of COVID-19. Med Sci Monit 2020, 26, e928996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrotek S, LeGrand EK, Dzialuk A, Alcock J. Let fever do its job: the meaning of fever in the pandemic era. Evol Med Public Health 2021, 9, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vithoulkas, G. The Science of Homeopathy; B. Jain Publishers, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mahesh S, Mahesh M, Vithoulkas G. Could homeopathy become an alternative therapy in dengue fever? An example of 10 case studies. J Med Life 2018, 11, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of AYUSH. Guidelines for Homoeopathic Practitioners for COVID 19; Ministry of AYUSH, Govt of India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, R. COVID and classical homeopathy. Homœopathic Links 2020, 33, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahnemann, S. Organon of Medicine; B. Jain Publishers, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahim SA, Tessema M, Defar A, et al. Time to recovery and its predictors among adults hospitalized with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study in Ethiopia. PLoS One 2021, 15, e0244269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinsky I, Baristaite G, Gurwitz D. Effects of age and sex on recovery from COVID-19: analysis of 5769 Israeli patients. J Infect 2020, 81, e102–e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen C, Zhang Y, Huang J, et al. Favipiravir versus arbidol for COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. medRxiv 2020. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Humanitarian Data Exchange. v1.62.1. United Nations Organisation. 2022. Available online: https://data.humdata.org/event/covid-19 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Jeon SR, Kang JW, Ang L, Lee HW, Lee MS, Kim TH. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) interventions for COVID-19: an overview of systematic reviews. Integr Med Res 2022, 11, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, EG. The experience of an Italian public homeopathy clinic during the COVID-19 epidemic, March-May 2020. Homeopathy 2020, 109, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varanasi R, Nayak D, Khurana A. Clinical repurposing of medicines is intrinsic to homeopathy: research initiatives on COVID-19 in India. Homeopathy 2021, 110, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jethani B, Gupta M, Wadhwani P, et al. Clinical characteristics and remedy profiles of patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Homeopathy 2021, 110, 086–093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslo C, Friedland R, Toubkin M, Laubscher A, Akaloo T, Kama B. Characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized patients in South Africa during the COVID-19 omicron wave compared with previous waves. JAMA 2022, 327, 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogier T, Eberl I, Moretto F, et al. COVID-19 or not COVID-19? Compared characteristics of patients hospitalized for suspected COVID-19. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2021, 40, 2023–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen JR, Martin MR, Martin JD, Kuhn P, Hicks JB. Modeling the onset of symptoms of COVID-19. Front Public Health 2020, 8, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh S, van der Werf E, Mallappa M, Vithoulkas G, Lai N. Long-term health effects of antipyretic drug use in the ageing population: protocol for a systematic review. F1000Research 2020, 9, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh S, Mallappa M, Habchi O, et al. Appearance of acute inflammatory state indicates improvement in atopic dermatitis cases under classical homeopathic treatment: a case series. Clin Med Insights Case Rep 2021, 14, 1179547621994103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vithoulkas, G. Levels of Health; International Academy of Classical Homeopathy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cann SAH. Fever: could a cardinal sign of COVID-19 infection reduce mortality? Am J Med Sci 2021, 361, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, AA. Should we let fever run its course in the early stages of COVID-19? J R Soc Med 2020, 113, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guihur A, Rebeaud ME, Fauvet B, Tiwari S, Weiss YG, Goloubinoff P. Moderate fever cycles as a potential mechanism to protect the respiratory system in COVID-19 patients. Front Med 2020, 7, 564170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhavani SV, Huang ES, Verhoef PA, Churpek MM. Novel temperature trajectory subphenotypes in COVID-19. Chest 2020, 158, 2436–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waisse S, Oberbaum M, Frass M. The hydra-headed coronaviruses: implications of COVID-19 for homeopathy. Homeopathy 2020, 109, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewett, DB. Homeopathy in Influenza-A chorus of fifty in harmony. J Am Inst Homeopathy 1921, 1921, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Hahnemann, S. Cure and prevention of scarlet fever. In The Lesser Writings of Samuel Hahnemann; Dudgeon, R.E., Ed.; B Jain Publishers (P) Ltd, 2004; pp. 369–389. [Google Scholar]

- Von Boenninghausen CMF. Concerning the Curative Effects of Thuja in Small-Pox; B. Jain Publishers (P) Ltd, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak D, Chadha V, Jain S, et al. Effect of adjuvant homeopathy with usual care in management of thrombocytopenia due to dengue: a comparative cohort study. Homeopathy 2019, 32, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilip C, Saraswathi R, Krishnan PN, et al. Comparitive evaluation of different systems of medicines and the present scenario of chikungunya in Kerala. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2010, 3, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastri V, Patel G, Shah P. A study of efficacy of homeopathic management of chikungunya. Natl J Integr Res Med 2021, 12, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary A, Khurana A. A review on the role of Homoeopathy in epidemics with some reflections on COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2). Indian J Res Homoeopathy 2020, 14, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler UC, Adler MS, Hotta LM, et al. Homeopathy for Covid-19 in primary care: a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2021, 22, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugam C, Mohammed AR, Ravuri S, Luthra V, Rajagopal N, Karre S. COVID-2019-a comprehensive pathology insight. Pathol Res Pract 2020, 216, 153222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).