Submitted:

06 January 2023

Posted:

09 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Animals, diets, and feeding interventions

2.3. Plasma lipid analysis

2.4. Glucose and Insulin Tolerance Test

2.5. Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

2.6. RNA extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

2.7. Liver lipid content

2.8. Liver reactive oxygen species and TBARS

2.9. Cannulation of the common bile duct and collection of hepatic bile

2.10. Biliary lipid analyses

2.11. Atherosclerotic lesions analysis

2.12. Statistical analysis

3. Results

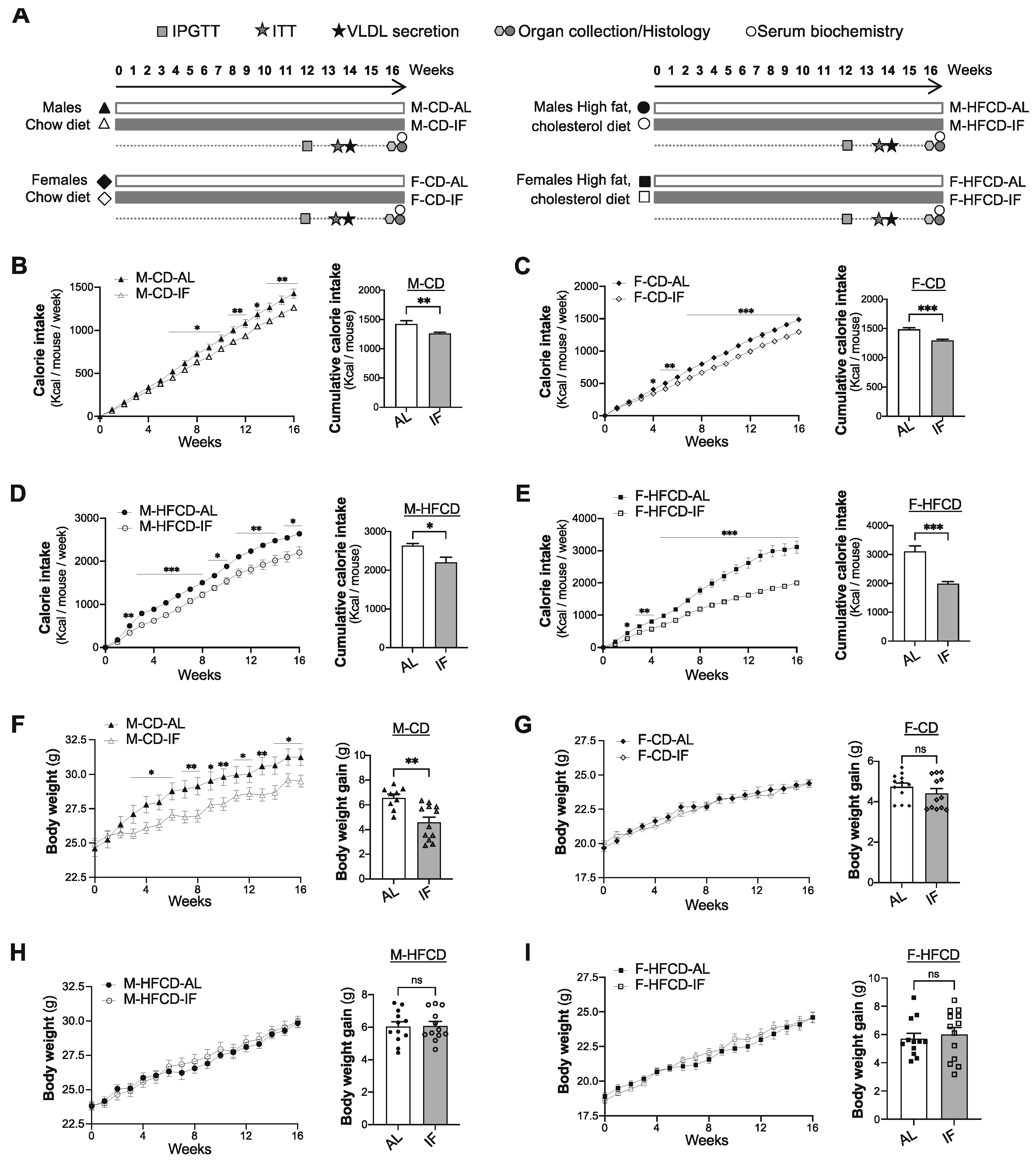

3.1. Food intake and body weight gain

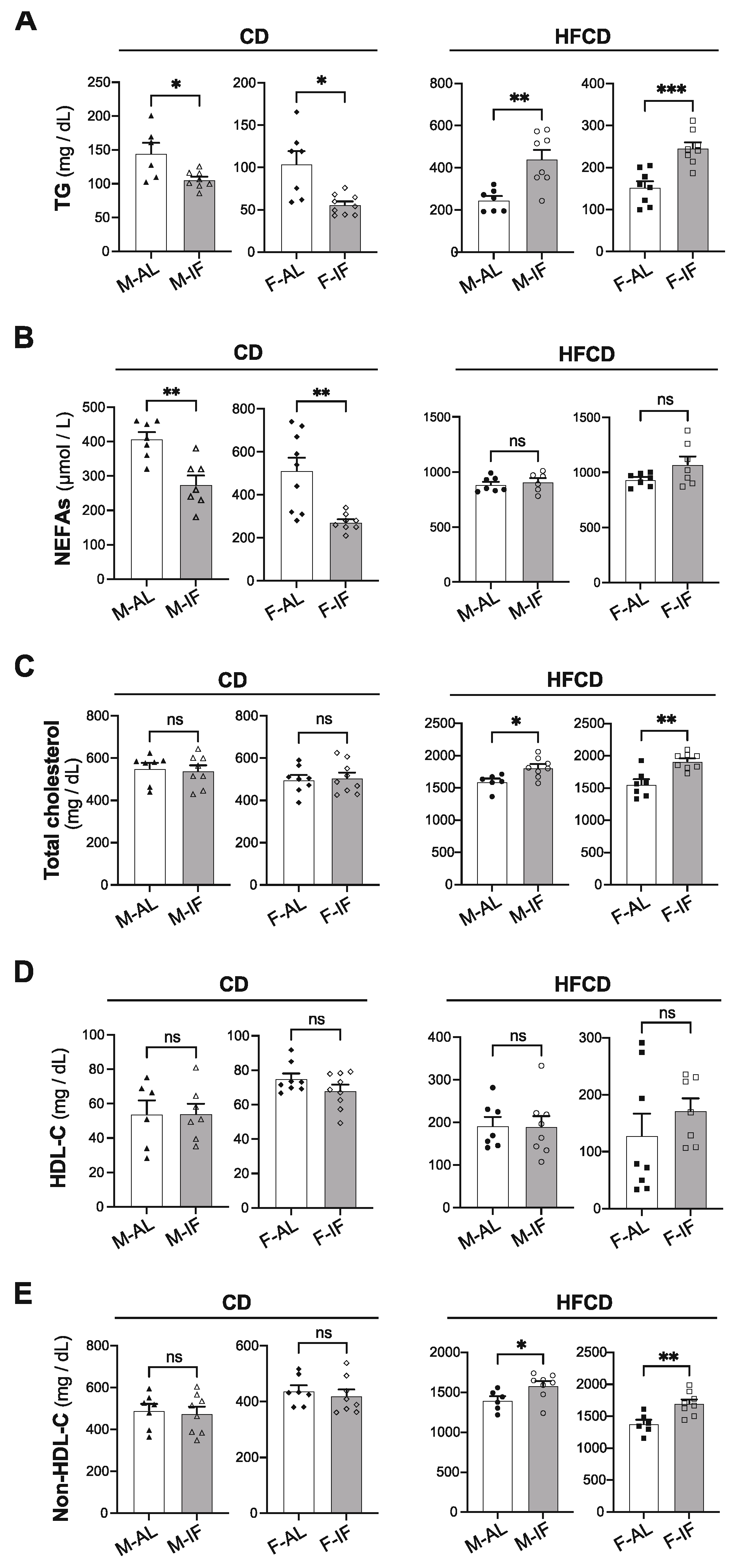

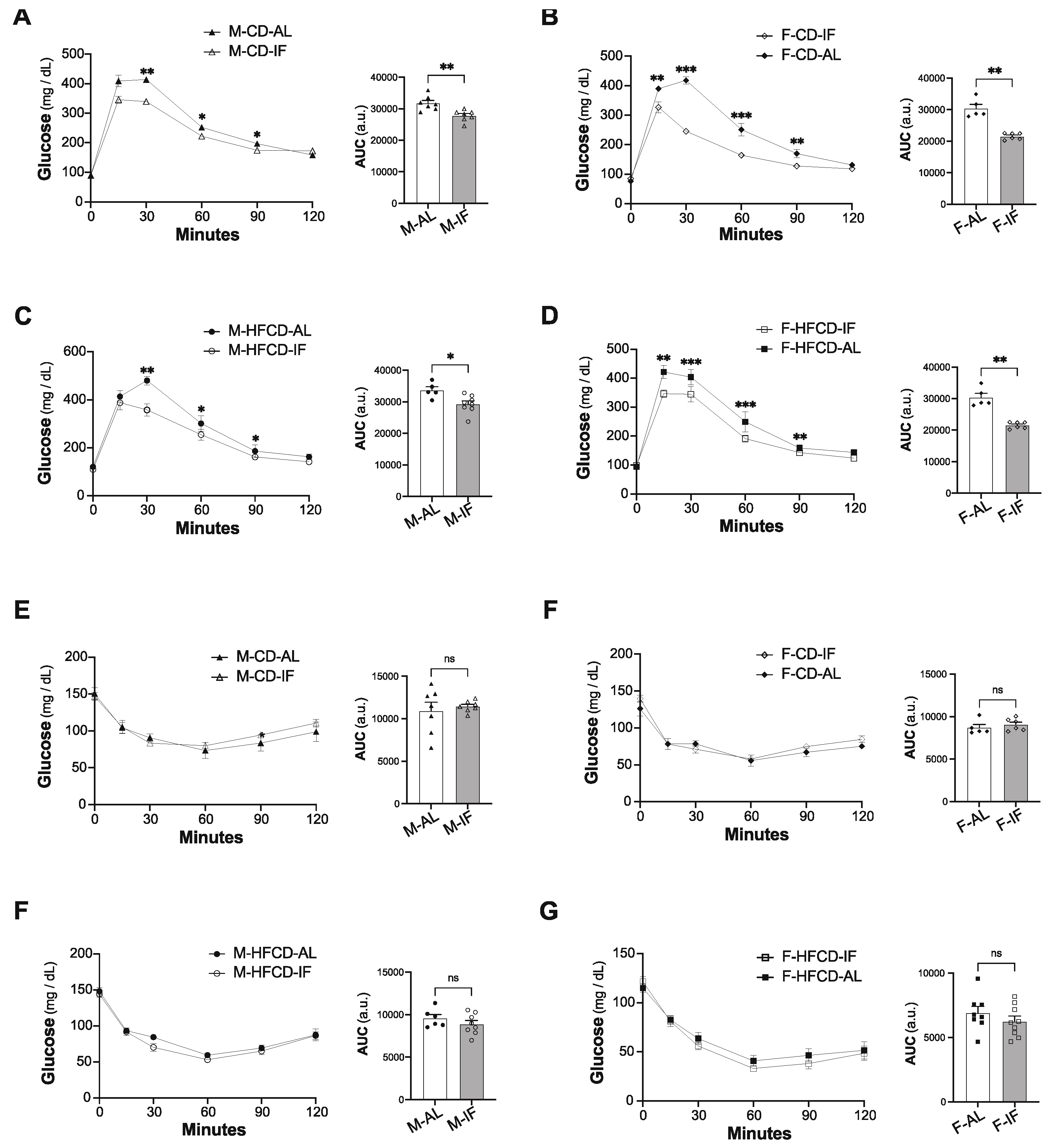

3.2. Lipid and glucose homeostasis

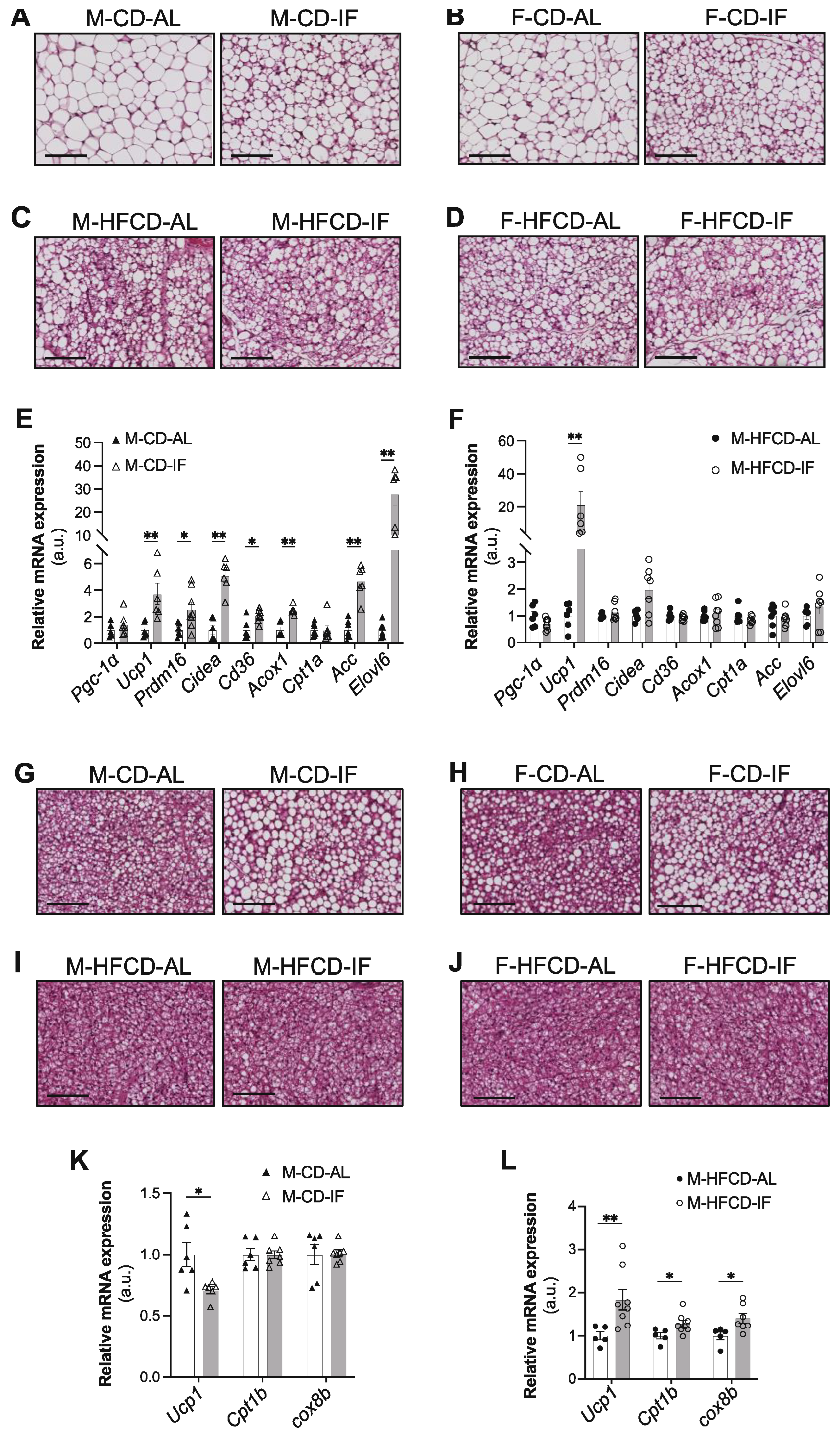

3.3. Adipose tissue features

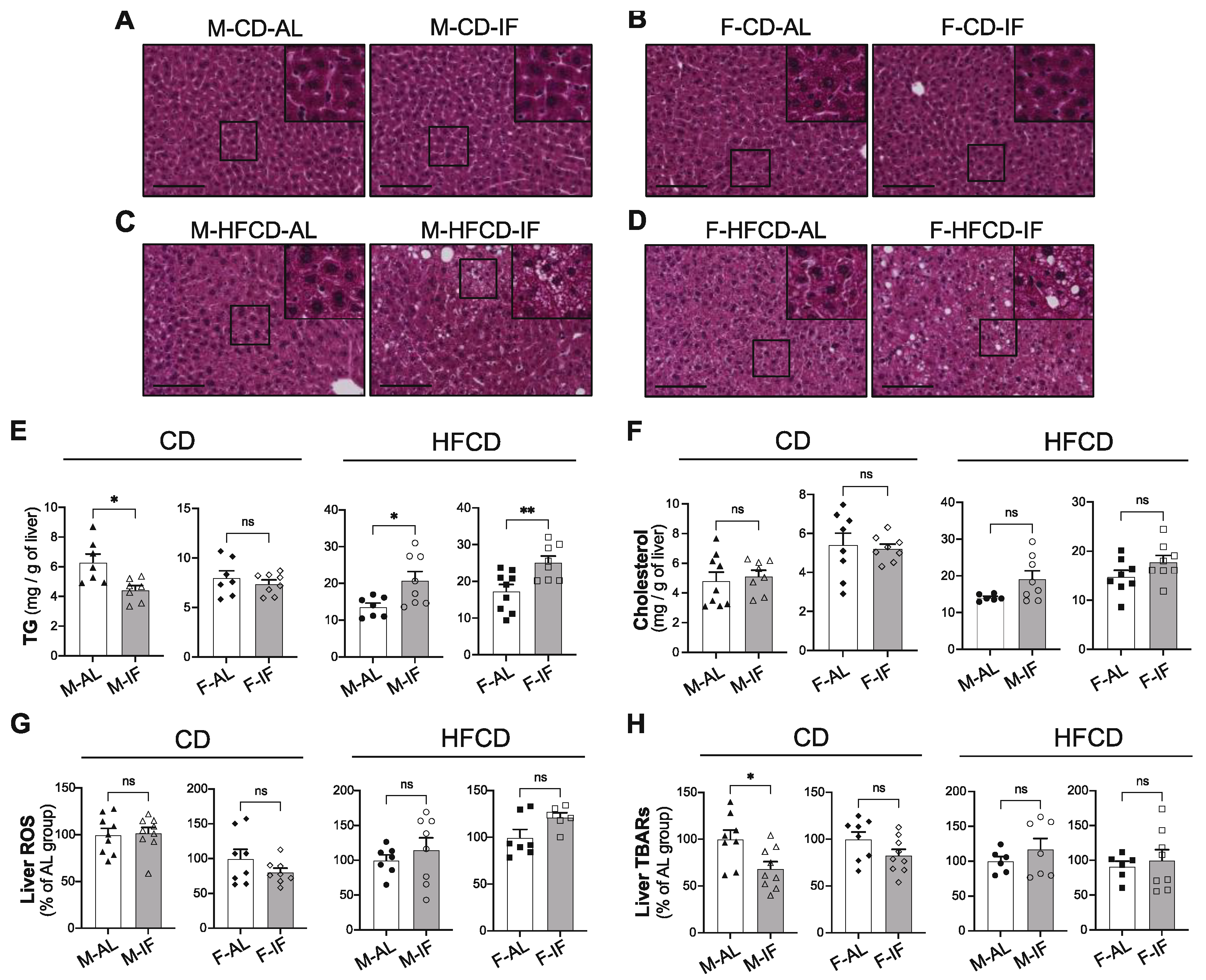

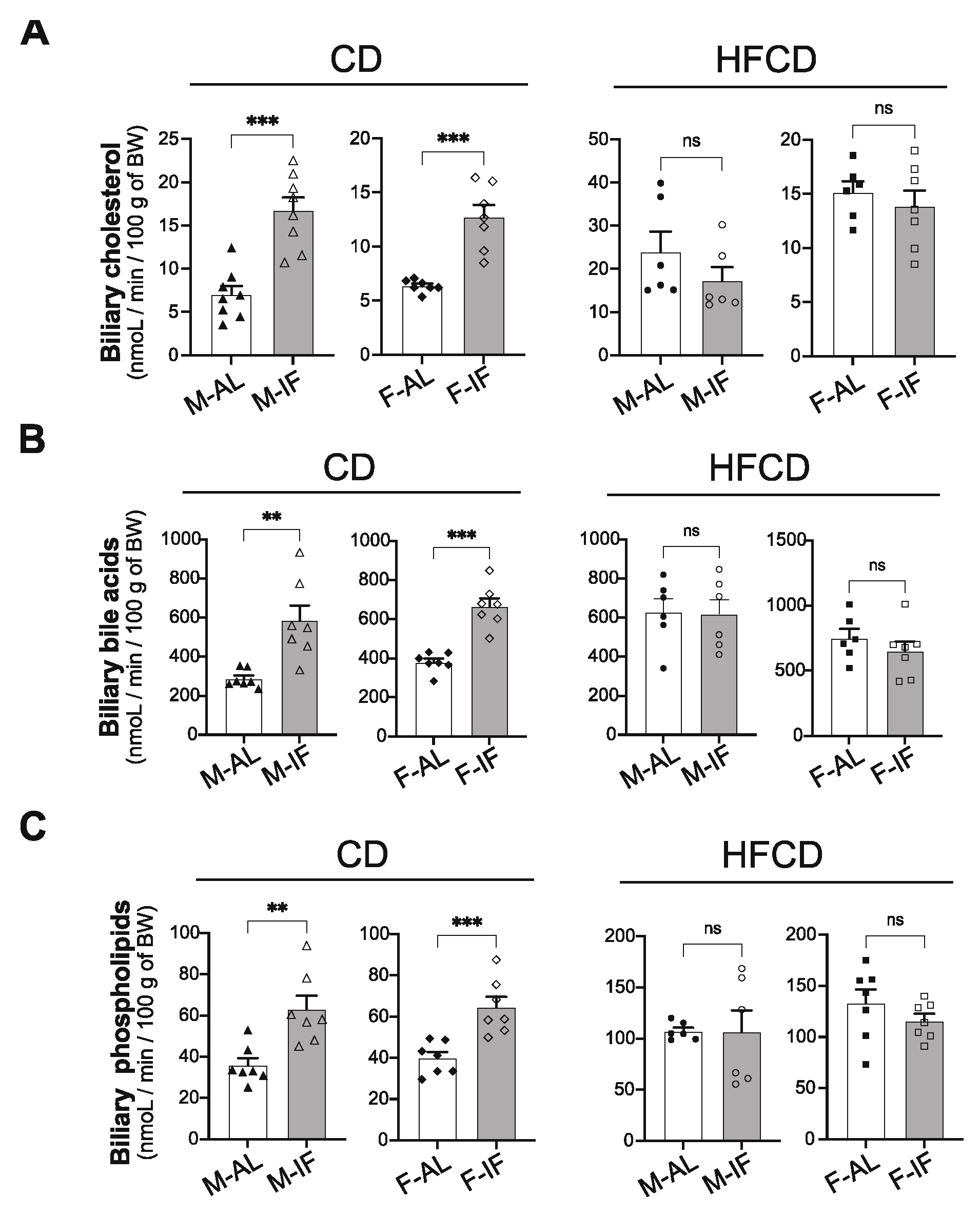

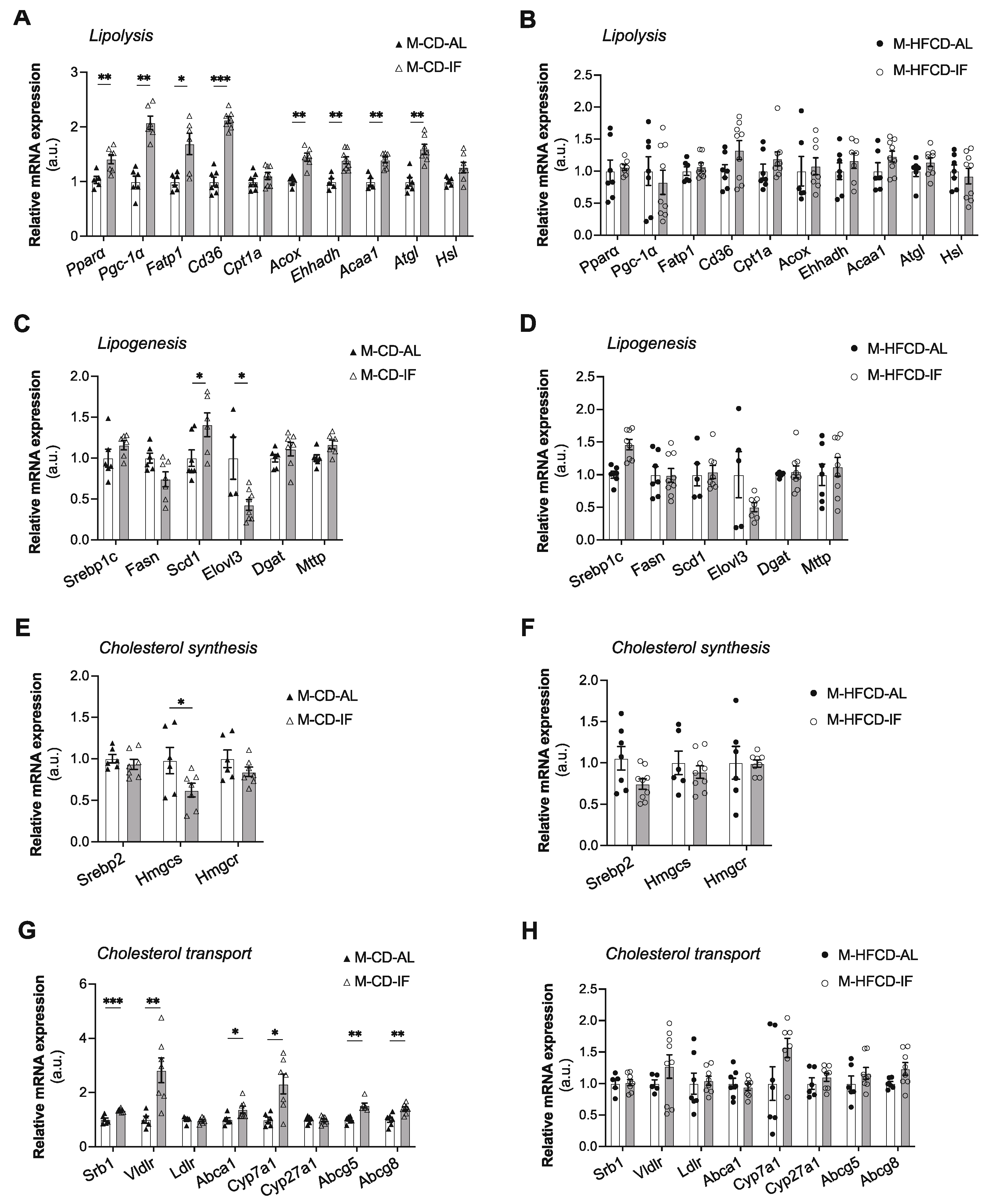

3.4. Hepatic lipid metabolism

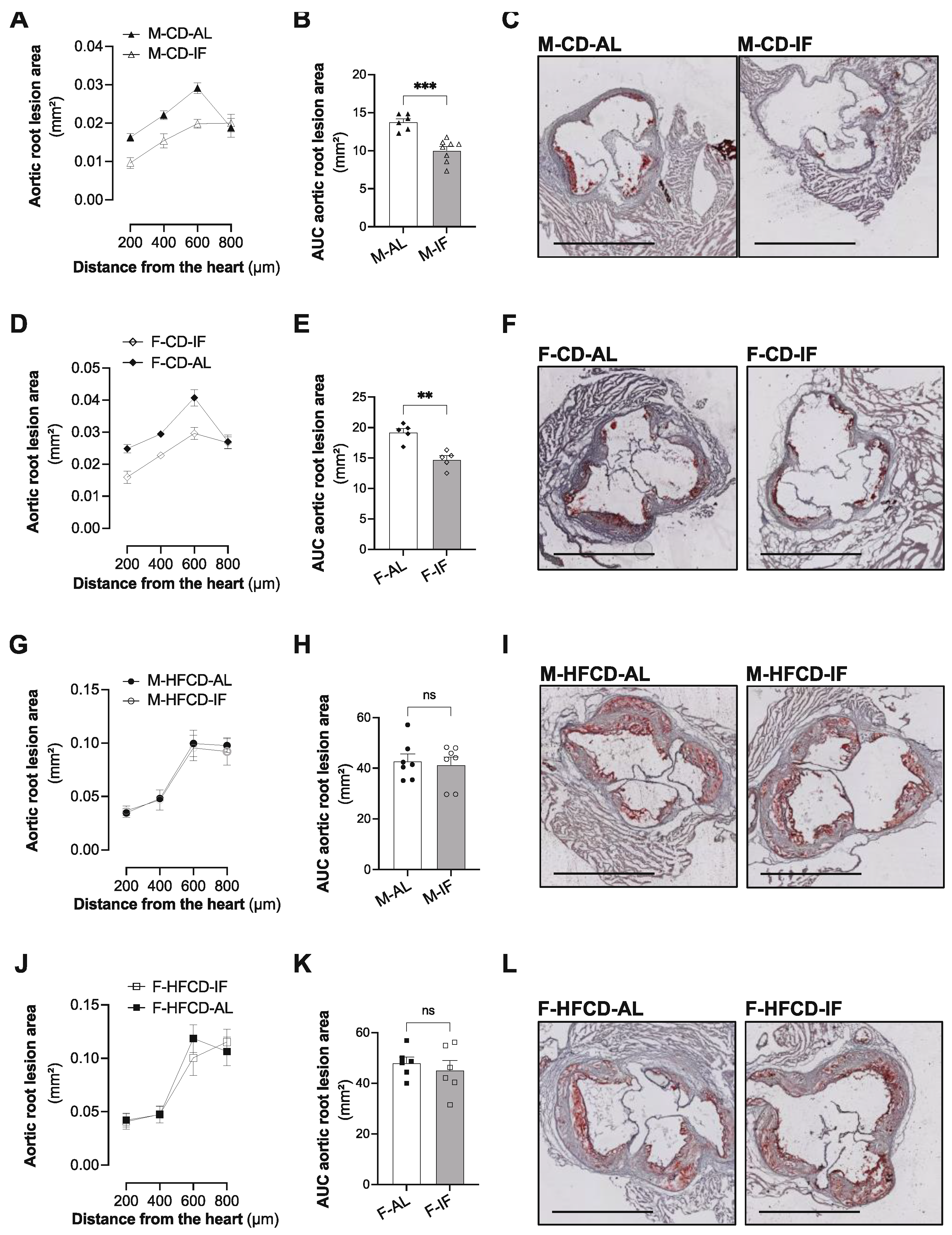

3.5. Atherosclerosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamman, R.F.; Wing, R.R.; Edelstein, S.L.; Lachin, J.M.; Bray, G.A.; Delahanty, L.; Hoskin, M.; Kriska, A.M.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Pi-Sunyer, X.; et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 2102–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, P.; Giles, T.D.; Bray, G.A.; Hong, Y.; Stern, J.S.; Pi-Sunyer, F.X.; Eckel, R.H. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: An update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on obesity and heart disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical. Circulation 2006, 113, 898–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavie, C.J.; Milani, R. V; Ventura, H.O. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease. Risk Factor, Paradox, and Impact of Weight Loss. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristow, M.; Schmeisser, S. Extending life span by increasing oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rynders, C.A.; Thomas, E.A.; Zaman, A.; Pan, Z.; Catenacci, V.A.; Melanson, E.L. Effectiveness of intermittent fasting and time-restricted feeding compared to continuous energy restriction for weight loss. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, D.E.; Wan, R.; Brown, M.; Cheng, A.; Wareski, P.; Abernethy, D.R.; Mattson, M.P. Caloric restriction and intermittent fasting alter spectral measures of heart rate and blood pressure variability in rats. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varady, K.A.; Hudak, C.S.; Hellerstein, M.K. Modified alternate-day fasting and cardioprotection: relation to adipose tissue dynamics and dietary fat intake. Metabolism. 2009, 58, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbronn, L.K.; De Jonge, L.; Frisard, M.I.; DeLany, J.P.; Larson-Meyer, D.E.; Rood, J.; Nguyen, T.; Martin, C.K.; Volaufova, J.; Most, M.M.; et al. Effect of 6-month calorie restriction on biomarkers of longevity, metabolic adaptation, and oxidative stress in overweight individuals: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006, 295, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halberg, N.; Henriksen, M.; Söderhamn, N.; Stallknecht, B.; Ploug, T.; Schjerling, P.; Dela, F. Effect of intermittent fasting and refeeding on insulin action in healthy men. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 99, 2128–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.B.; Summer, W.; Cutler, R.G.; Martin, B.; Hyun, D.H.; Dixit, V.D.; Pearson, M.; Nassar, M.; Tellejohan, R.; Maudsley, S.; et al. Alternate day calorie restriction improves clinical findings and reduces markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in overweight adults with moderate asthma. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 42, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, R.; Robertson, T.M.; Robertson, M.D.; Johnston, J.D. A pilot feasibility study exploring the effects of a moderate time-restricted feeding intervention on energy intake, adiposity and metabolic physiology in free-living human subjects. J. Nutr. Sci. 2018, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, T.; Tinsley, G.; Bianco, A.; Marcolin, G.; Pacelli, Q.F.; Battaglia, G.; Palma, A.; Gentil, P.; Neri, M.; Paoli, A. Effects of eight weeks of time-restricted feeding (16/8) on basal metabolism, maximal strength, body composition, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk factors in resistance-trained males. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchison, A.T.; Regmi, P.; Manoogian, E.N.C.; Fleischer, J.G.; Wittert, G.A.; Panda, S.; Heilbronn, L.K. Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Glucose Tolerance in Men at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Obesity 2019, 27, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.; Panda, S. A Smartphone App Reveals Erratic Diurnal Eating Patterns in Humans that Can Be Modulated for Health Benefits. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, M.J.; Manoogian, E.N.C.; Zadourian, A.; Lo, H.; Fakhouri, S.; Shoghi, A.; Wang, X.; Fleischer, J.G.; Navlakha, S.; Panda, S.; et al. Ten-Hour Time-Restricted Eating Reduces Weight, Blood Pressure, and Atherogenic Lipids in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 92–104.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.; Kang, J.; Kim, S.H.; Chung, H.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Yu, J.M.; Cho, S.T.; Oh, C.M.; Kim, T. Beneficial effects of time-restricted eating on metabolic diseases: A systemic review and meta- analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, V.D.; Di Tano, M.; Mattson, M.P.; Guidi, N. Intermittent and periodic fasting, longevity and disease. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaix, A.; Zarrinpar, A.; Miu, P.; Panda, S. Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 991–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.; Chou, W.; Sears, D.D.; Patterson, R.E.; Webster, N.J.G.; Ellies, L.G. Time-restricted feeding improves insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in a mouse model of postmenopausal obesity. Metabolism. 2016, 65, 1743–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutani, S.; Klempel, M.C.; Berger, R.A.; Varady, K.A. Improvements in coronary heart disease risk indicators by alternate-day fasting involve adipose tissue modulations. Obesity 2010, 18, 2152–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.D.; Mattson, M.P. Fasting: Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Su, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Ma, J.; Zhu, M.; He, X.; Zhang, B.; Xu, H.; Yang, X.; et al. Intermittent Fasting Inhibits High-Fat Diet–Induced Atherosclerosis by Ameliorating Hypercholesterolemia and Reducing Monocyte Chemoattraction. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.I.; Toyoda, S.; Jojima, T.; Abe, S.; Sakuma, M.; Inoue, T. Time-restricted feeding prevents high-fat and high-cholesterol diet-induced obesity but fails to ameliorate atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein e-knockout mice. Exp. Anim. 2021, 70, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorighello, G.G.; Rovani, J.C.; Luhman, C.J.F.; Paim, B.A.; Raposo, H.F.; Vercesi, A.E.; Oliveira, H.C.F. Food restriction by intermittent fasting induces diabetes and obesity and aggravates spontaneous atherosclerosis development in hypercholesterolaemic mice. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, Y.; Plump, A.S.; Raines, E.W.; Breslow, J.L.; Ross, R. ApoE-deficient mice develop lesions of all phases of atherosclerosis throughout the arterial tree. Arterioscler. Thromb. 1994, 14, 133–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eenige, R.; Verhave, P.S.; Koemans, P.J.; Tiebosch, I.A.C.W.; Rensen, P.C.N.; Kooijman, S. RandoMice, a novel, user-friendly randomization tool in animal research. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0237096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, R.E.; Sears, D.D. Metabolic Effects of Intermittent Fasting. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2017, 37, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duparc, T.; Briand, F.; Trenteseaux, C.; Merian, J.; Combes, G.; Najib, S.; Sulpice, T.; Martinez, L.O. Liraglutide improves hepatic steatosis and metabolic dysfunctions in a 3-week dietary mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2019, 317, G508–G517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane Stanley, G.H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, L.; Serhan, N.; Annema, W.; Combes, G.; Robaye, B.; Boeynaems, J.-M.M.; Perret, B.; Tietge, U.J.F.; Laffargue, M.; Martinez, L.O. Lack of P2Y13 in mice fed a high cholesterol diet results in decreased hepatic cholesterol content, biliary lipid secretion and reverse cholesterol transport. Nutr. Metab. (Lond). 2013, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, L.; Serhan, N.; Espinosa-Delgado, S.; Fabre, A.; Annema, W.; Tietge, U.J.F.; Robaye, B.; Boyenaems, J.-M.; Laffargue, M.; Perret, B.; et al. Increased Atherosclerosis in P2Y13 / Apolipoprotein E Double-Knockout Mice: Contribution of P2Y13 to Reverse Cholesterol Transport. Cardiovasc. Res. 2015, 106, 315–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenstein, L.; Serhan, N.; Espinosa-Delgado, S.; Fabre, A.; Annema, W.; Tietge, U.J.F.; Robaye, B.; Boeynaems, J.M.; Laffargue, M.; Perret, B.; et al. Increased atherosclerosis in P2Y13/apolipoprotein e double-knockout mice: Contribution of P2Y13 to reverse cholesterol transport. Cardiovasc. Res. 2015, 106, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, H.M.; Golozoubova, V.; Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J. UCP1 Ablation Induces Obesity and Abolishes Diet-Induced Thermogenesis in Mice Exempt from Thermal Stress by Living at Thermoneutrality. Cell Metab. 2009, 9, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Xie, C.; Lu, S.; Nichols, R.G.; Tian, Y.; Li, L.; Patel, D.; Ma, Y.; Brocker, C.N.; Yan, T.; et al. Intermittent Fasting Promotes White Adipose Browning and Decreases Obesity by Shaping the Gut Microbiota. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 672–685.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Katagiri, H.; Ishigaki, Y.; Yamada, T.; Ogihara, T.; Imai, J.; Uno, K.; Hasegawa, Y.; Kanzaki, M.; Yamamoto, T.T.; et al. Involvement of apolipoprotein E in excess fat accumulation and insulin resistance. Diabetes 2007, 56, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Choi, E.Y.; Liu, X.; Martin, A.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; During, M.J. White to brown fat phenotypic switch induced by genetic and environmental activation of a hypothalamic-adipocyte axis. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.O.; Ingueneau, C.; Genoux, A. Is it time to reconcile HDL with cardiovascular diseases and beyond? An update on a paradigm shift. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2020, 31, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Wang, Y.N.; Ma, H.; He, Z.H.; Tang, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y.; Ding, M.; Qian, S.W.; Tang, Q.Q. SCD1 promotes lipid mobilization in subcutaneous white adipose tissue. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 1589–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varady, K.A.; Allister, C.A.; Roohk, D.J.; Hellerstein, M.K. Improvements in body fat distribution and circulating adiponectin by alternate-day fasting versus calorie restriction. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010, 21, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkacemi, L.; Selselet-Attou, G.; Hupkens, E.; Nguidjoe, E.; Louchami, K.; Sener, A.; Malaisse, W.J. Intermittent fasting modulation of the diabetic syndrome in streptozotocin-injected rats. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 2012, 962012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaix, A.; Lin, T.; Le, H.D.; Chang, M.W.; Panda, S. Time-Restricted Feeding Prevents Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome in Mice Lacking a Circadian Clock. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 303–319.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaix, A.; Deota, S.; Bhardwaj, R.; Lin, T.; Panda, S. Sex- and age-dependent outcomes of 9-hour time-restricted feeding of a Western high-fat high-sucrose diet in C57BL/6J mice. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Pearson, M.; Brenneman, R.; Golden, E.; Wood, W.; Prabhu, V.; Becker, K.G.; Mattson, M.P.; Maudsley, S. Gonadal transcriptome alterations in response to dietary energy intake: Sensing the reproductive environment. PLoS One 2009, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruder-Nascimento, T.; Ekeledo, O.J.; Anderson, R.; Le, H.B.; Belin de Chantemèle, E.J. Long term high fat diet treatment: An appropriate approach to study the sex-specificity of the autonomic and cardiovascular responses to obesity in mice. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, S.M.; Perez-Tilve, D.; Greer, T.M.; Coburn, B.A.; Grant, E.; Basford, J.E.; Tschöp, M.H.; Hui, D.Y. Defective lipid delivery modulates glucose tolerance and metabolic response to diet in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Diabetes 2008, 57, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desautels, M.; Dulos, R.A. Effects of repeated cycles of fasting-refeeding on brown adipose tissue composition in mice. Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab. 1988, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, M.; Nagasaka, T. Suppression of norepinephrine-induced thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue by fasting. Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab. 1983, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivitz, W.I.; Fink, B.D.; Donohoue, P.A. Fasting and leptin modulate adipose and muscle uncoupling protein: Divergent effects between messenger ribonucleic acid and protein expression. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.Y.Y.; Virtue, S.; Bidault, G.; Dale, M.; Hagen, R.; Griffin, J.L.L.; Vidal-Puig, A. Brown Adipose Tissue Thermogenic Capacity Is Regulated by Elovl6. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 2039–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Yang, X.; Lim, S.; Cao, Z.; Honek, J.; Lu, H.; Zhang, C.; Seki, T.; Hosaka, K.; Wahlberg, E.; et al. Cold exposure promotes atherosclerotic plaque growth and instability via UCP1-dependent lipolysis. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, W.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Jing, X.; Xue, F.; Cheng, J.; Dong, M.; Zhang, M.; Pan, H.; Chen, Y.; et al. Bladder drug mirabegron exacerbates atherosclerosis through activation of brown fat-mediated lipolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 166, 10937–10942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Page, A.J.; Hatzinikolas, G.; Chen, M.; Wittert, G.A.; Heilbronn, L.K. Intermittent fasting improves glucose tolerance and promotes adipose tissue remodeling in male mice fed a high-fat diet. Endocrinology 2019, 160, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Page, A.J.; Hutchison, A.T.; Wittert, G.A.; Heilbronn, L.K. Intermittent fasting increases energy expenditure and promotes adipose tissue browning in mice. Nutrition 2019, 66, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinho, T. de S.; Ornellas, F.; Aguila, M.B.; Mandarim-de-Lacerda, C.A. Browning of the subcutaneous adipocytes in diet-induced obese mouse submitted to intermittent fasting. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrén, B.; Pacini, G. Glucose effectiveness: Lessons from studies on insulin-independent glucose clearance in mice. J. Diabetes Investig. 2021, 12, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Wei, X.; Sun, F.; Zhang, H.; Gao, P.; Pu, Y.; Wang, A.; Chen, J.; Tong, W.; Li, Q.; et al. Non-insulin determinant pathways maintain glucose homeostasis upon metabolic surgery. Cell Discov. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebeling, P.; Koistinen, H.A.; Koivisto, V.A. Insulin-independent glucose transport regulates insulin sensitivity. FEBS Lett. 1998, 436, 301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karavia, E.A.; Papachristou, D.J.; Kotsikogianni, I.; Giopanou, I.; Kypreos, K.E. Deficiency in apolipoprotein e has a protective effect on diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 3119–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Mei, J.; Yang, J.; Wu, Z.; Liu, J.; Miao, P.; Chen, Y.; Wen, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Kong, H.; et al. ApoE deficiency promotes non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice via impeding AMPK/mTOR mediated autophagy. Life Sci. 2020, 252, 117601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikkers, A.; Tietge, U.J.F. Biliary cholesterol secretion: More than a simple ABC. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 5936–5945. [Google Scholar]

- Olivecrona, G. Role of lipoprotein lipase in lipid metabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2016, 27, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdier, L.L.; Boirie, Y.; Van Drieesche, S.; Mignon, M.; Begue, R.J.; Meynial-Denis, D. LDL receptor but not apolipoprotein E deficiency increases diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 282, 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, G.S.; Reardon, C.A. Do the Apoe-/- and Ldlr-/- mice yield the same insight on atherogenesis? Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 1734–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Wu, W.; Yan, H.; Wang, Y. Hyperlipidemia and atherosclerotic lesion development in Ldlr-deficient mice on a long-term high-fat diet. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, D.; Ni, R.; Bernards, M.A. Dietary fatty acids alter lipid profiles and induce myocardial dysfunction without causing metabolic disorders in mice. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parathath, S.; Grauer, L.; Huang, L.S.; Sanson, M.; Distel, E.; Goldberg, I.J.; Fisher, E.A. Diabetes adversely affects macrophages during atherosclerotic plaque regression in mice. Diabetes 2011, 60, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagareddy, P.R.; Murphy, A.J.; Stirzaker, R.A.; Hu, Y.; Yu, S.; Miller, R.G.; Ramkhelawon, B.; Distel, E.; Westerterp, M.; Huang, L.S.; et al. Hyperglycemia promotes myelopoiesis and impairs the resolution of atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).