1. Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is a minimally invasive procedure that was initially developed for the management of symptomatic severe aortic valve stenosis. The technique was first performed in 2002 on an inoperable 57-year-old patient who had previously undergone balloon aortic valvuloplasty (1). Since then, TAVR has gained more interest and established a sizeable clinical and market value with more than 110,000 procedures performed from 2015 through 2017 in the United States (US) alone, and a global market worth $2 billion annually (2,3). With TAVR being much less invasive than surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) and the accumulating evidence of its favorable outcomes, starting 2016 the food and drug administration (FDA) gradually expanded its indications to include low- and intermediate-risk patients (4).

In view of the expanding number of TAVR procedures, rare complications including infective endocarditis have been reported. Complications may manifest as catastrophic aortic root dissection, paravalvular and aortic root abscesses, and intra/paravalvular regurgitation (5). Studies have estimated that the 1-year incidence of prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) complicating TAVR (TAVR-PVE) ranges between 0.2% (in the PARTNER 3 trial) and 3.1% (in a Danish cohort study including 509 patients) (4,6). Additionally, the partner 1A trial and the NOTION trial recorded a cumulative 5-year incidence of 2% and 6.2% respectively (7,8). Although uncommon, TAVR-PVE is associated with a high in-hospital mortality rate reaching 34.4% in one systematic review (9). In a pooled analysis of patients from the PARTNER 1 and PARTNER 2 trial, TAVR-PVE was found to be an independent risk factor for mortality (10). However this risk is not higher compared to SAVR. A meta-analysis of four comparative randomized controlled trials (RCT) analyzing around 3,800 patients during a mean follow-up period of 3.4 years found no significant difference in the frequency of endocarditis between both approaches. Furthermore, a meta-analysis which included over 84,000 patients concluded that the short and long-term risk of PVE appears to be identical in patients undergoing TAVR and SAVR regardless of the type of valve used, the duration of follow-up, or the patients’ surgical risk (11).

The diagnosis of TAVR-PVE may be challenging due to the low sensitivity of conventional diagnostic tools and the panoply of non-specific symptoms (5). In light of its high mortality and dreadful complications, clinicians should have a low threshold to consider PVE in patients with a history of TAVR who present with suggestive symptoms and signs to promptly initiate proper management. It should be noted that the mortality remains elevated in patients who were only managed with antibiotics as well as those who also underwent repeat surgery (9).

Although years of experience with SAVR-PVE have generated a considerable amount of evidence and recommendations, this may not be the case for TAVR patients with PVE, who may present with different demographics, symptoms, and causative organisms. Hence, clinicians from different specialties should be familiar with the clinical presentation, diagnosis and microbiology of TAVR-PVE in order to optimize the care of these patients and avoid detrimental complications. Herein, we shall elucidate the disease’s predictors and risk factors and discuss the diagnostic challenges and pertinent microbiological data while focusing on differences between TAVR and SAVR. We will finally review the latest evidence on prevention strategies and antimicrobial management of TAVR-PVE.

Risk Factors and Predictors of TAVR-PVE

Younger age and male sex have been the most commonly reported non modifiable risk factors for TAVR-PVE (9,12,13). In fact, a recent meta-analysis including over 68,000 patients reported that older age was associated with a significantly lower risk of TAVR-PVE (RR 0.97, 95% CI: 0.95-0.99, P =0.007) (13). One suggested explanation is that younger patients requiring TAVR have more significant comorbidities compared to their older counterparts. For instance, a prospective study including 1,448 patients who underwent TAVR found that younger patients with TAVR-PVE had significantly higher rates of diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD) requiring hemodialysis (HD), prior cardiac surgery, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (14). The lower incidence of TAVR-PVE in female sex has been attributed to the protective effects of estrogen on the vascular endothelium, however, additional studies are warranted to thoroughly investigate the underlying mechanisms (12,14). Although most studies report male sex as a risk factor for TAVR-PVE, a recent retrospective cohort study revealed that the incidence was similar between both sexes. Moreover, female sex was identified as an independent risk factor for mortality (15).

Modifiable risk factors that affect the patients’ prognosis should be identified and addressed, if possible, as they may have significant implications on the management (10). Reported patient-related risk factors for PVE include diabetes mellitus (41.7% vs 30.0%; HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.02-2.29) (16), peripheral arterial disease (PAD), COPD, CKD, and HD (17). Moreover, a retrospective analysis of 3 combined national registries from Sweden found that body surface area, critical pre-operative state and atrial fibrillation were significant patient-related predictors of TAVR-PVE (18).

In addition to patient-related risk factors, some procedural factors have been incriminated in predisposing to TAVR-PVE. A meta-analysis and systematic review including 57,531 patients found that oro-tracheal intubation (RR 2.99, 95% CI:2.73-3.28, P<0.001) was a significant risk factor for TAVR-PVE (18). In fact, a study showed that over 10% of oro- or naso-tracheal intubations are complicated by Staphylococcus spp. or Streptococcus spp. bacteremia (19). Furthermore, TAVR has been associated with an increased incidence of high degree atrio-ventricular (AV) block requiring pacemaker implantation, which has been shown to increase the risk of TAVR-PVE (RR 5.19, 95% CI: 4.16-6.47. P<0.001) (18).

The impact of the valve’s type, self-expanding valve (SEV), or balloon expendable valve (BEV), on the incidence and mortality of TAVR-PVE is debatable. A recent meta-analysis including 30 studies and 73,780 patients found a numerically higher incidence of PVE among patients with BEV valves compared to those with SEV (0.8% vs 0.3%), however those findings were not significant (12). Additionally, Tinica et al. reported that SEV may be associated with lower mortality of TAVR-PVE (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.98, P<0.05) (20). On the other hand, a subgroup analysis in a study including 1,895 patients undergoing TAVR found no significant difference in the rates of TAVR-PVE among patients with SEV or BEV (21). Similarly, data from the multicenter “Infectious Endocarditis After TAVR International Registry” including 6,398 patients reported that neither the incidence of PVE nor the in-hospital mortality (34.4% in the SEV group vs 37.4% in the BEV group; P = 0.63) were correlated with the type of valve (16).

The route of vascular access (trans-femoral vs non-trans-femoral) does not seem to impact the incidence of TAVR-PVE as most studies have not been able to establish a definitive association (12). For instance, a meta-analysis including over 1,200 patients reported no association between trans-femoral vascular access and the risk of TAVR-PVE (RR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.71 to 1.02, P= 0.08) (13). Similar results were reported from a pooled analysis of all patients from the PARTNER 1 and PARTNER 2 trial (P=0.8) (10).

Residual aortic regurgitation (AR) is a common finding that has been reported in the majority of patients following TAVR (22). It may predispose to PVE either through mechanical damage caused by the high velocity regurgitate jet or through thrombus formation that serves as a nidus for infection (23,24). Early incidence of TAVR-PVE was significantly associated with post-procedural AR, particularly moderate to severe regurgitation (22.4% vs 14.7%; HR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.28-3.28) (16,18). This association could have implications on the management of patients post-TAVR as those with moderate to severe AR might require prophylactic antibiotics before procedures associated with a high risk of bacteremia.

The timing of TAVR-PVE relative to the procedure may be classified as very early (within 30 days), early (within 30-60 days), intermediate (between 60 and 365 days), or late (after 365 days) (25). Similarly to endocarditis following SAVR, most cases of TAVR-PVE occur within the first-year post implantation followed by an exponentially decreasing incidence over time (26). One registry including 250 definite cases of TAVR-PVE reported that the median time from TAVR to infective endocarditis was 5.3 months (interquartile range [IQR], 1.5-13.4 months) (ref). Another national registry from Sweden reported the incidence to be 1.42% during the first year, 0.80% during the following 1–5 years, and 0.52% after 5–10 years from the procedure (18). The higher incidence of PVE during the early post-procedural period may be explained by the presence of risk factors for bacteremia (indwelling catheters, central lines, critical illness), nosocomial infections, and incomplete endothelialization of the newly implanted valve (18,27).

Diagnostic Challenges of TAVR-PVE

Patients with TAVR-PVE do not often present with the typical signs and symptoms of endocarditis, like fever or new onset heart murmur, which might complicate the diagnosis and delay appropriate management (28). In fact, acute heart failure is one of the most common presentations of TAVR-PVE, alongside vague nonspecific symptoms like malaise and fatigue (29). One study which included 7,891 patients with TAVR-PVE found that heart failure was the second most common presenting symptom (58.5 %) after fever (71.7%) (9). Although the modified Duke criteria are highly sensitive for the diagnosis of native valve endocarditis (NVE), they are not as sensitive for the diagnosis of PVE (24). The lack of sensitivity may reflect on the epidemiological data of TAVR-PVE as the use of Duke criteria may underestimate its real incidence (24). In one study comparing Duke criteria to those of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) which include multimodal imaging, ESC’s modified criteria were found to have a sensitivity of 100% compared to only 50% for Duke’s criteria (30).

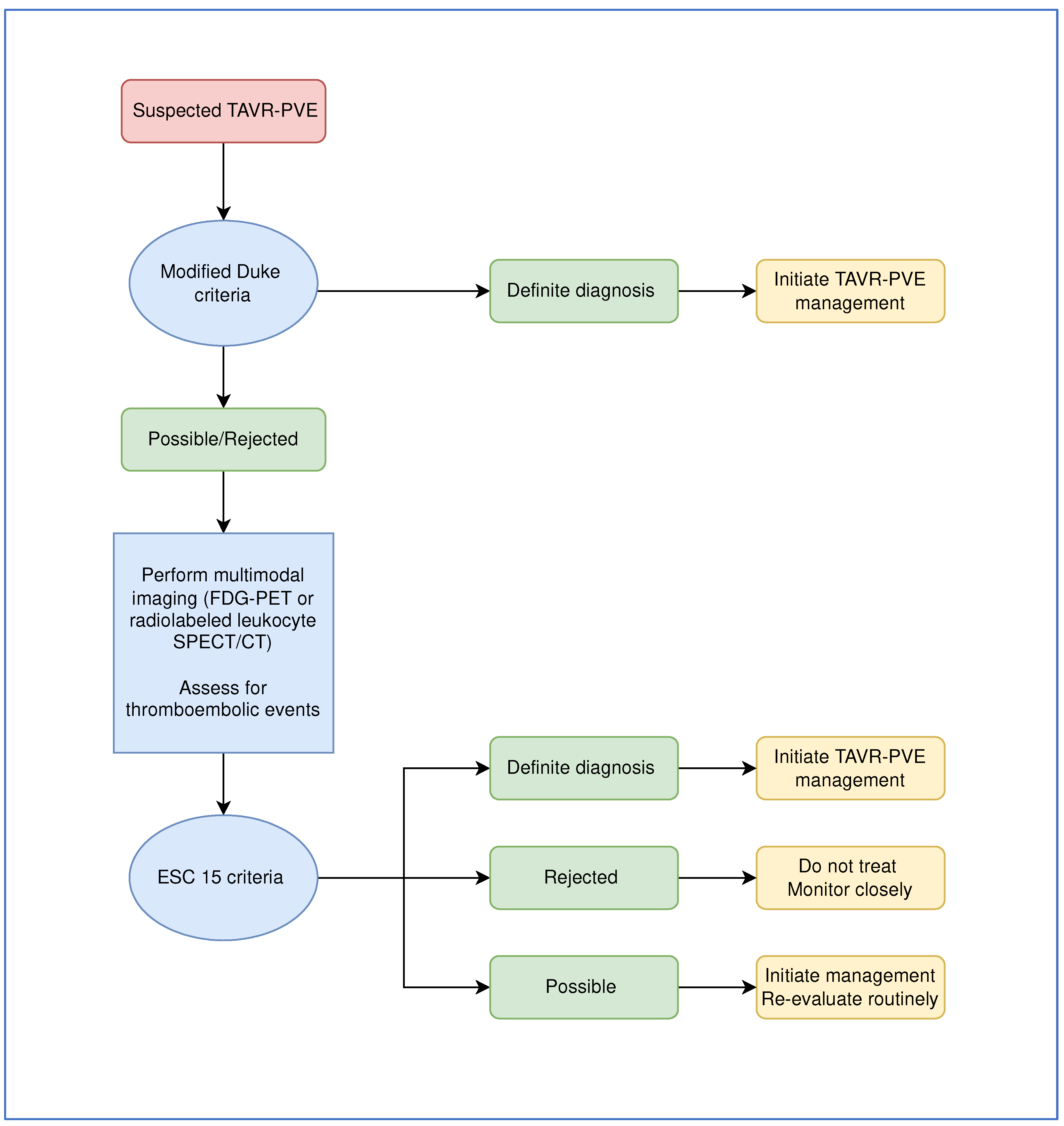

Echocardiography is the first line imaging modality to diagnose IE (30). Although trans-esophageal echocardiography (TEE) is more sensitive than trans-thoracic echocardiography (TTE), TTE is more often performed for its lower cost and convenience (31). However, in PVE, particularly TAVR-PVE, TTE may not be the optimal tool to establish the diagnosis (32). In fact, the high content of metal in TAVR valves and the distribution of metal struts within the valve may impair the visualization of vegetations, especially smaller ones (29). Additionally, vegetations are 3 times more likely to be detected on SEVs than BEVs on echocardiography because of the wider frame (16). Interestingly, one report by Mangner et al. showed that vegetations were observed in only 25% of 47 patients with TAVR-PVE while normal results were reported in up to 31.9%, confirming that TTE has a low diagnostic yield (17). TEE may also be unable to differentiate between vegetations and fibrous strands or thrombi (33). Hence, more advanced modalities of imaging are required such as fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and single proton emission CT scan to diagnose TAVR-PVE (scheme 1) (33). However, despite being integrated in the ESC’s guidelines, such advanced imaging techniques remain inaccessible and insufficiently performed especially in low-resource settings (34). The addition of abnormal FDG uptake on FDG-PET as a major criterion for the diagnosis of PVE may improve the diagnostic yield. For example, in a prospective study including patients with suspected PVE, the addition of FDG-PET to the modified Duke criteria as a major criterion significantly increased its sensitivity from 70% to 98% (p-value =0.008) (35). It should be noted that persistent vegetations after completion of the treatment course are often not an indicator of treatment failure and should not promote continuation of therapy beyond 6 weeks if clinical, biological, and microbiological cure is documented. However, it is advised that patients with persistent vegetations undergo repeat echocardiography as the increase in vegetation size or a size greater than 10 mm have been associated with poorer outcomes (36).

In light of all the diagnostic challenges of TAVR-PVE, it is encouraged that a multidisciplinary team consisting of cardiologists, infectious diseases specialists, microbiologists, cardiac imaging specialists, and cardiothoracic surgeons be involved in the care of the infected patient (37). Delays in establishing the diagnosis should be avoided to reduce mortality and spare the need for surgical intervention in this subset of patients who are at a high operative risk (38,39).

Scheme 1.

Decision pathway for the diagnosis and management of TAVR-PVE. FDG-PET, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography; ESC, European Society of Cardiology.

Scheme 1.

Decision pathway for the diagnosis and management of TAVR-PVE. FDG-PET, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography; ESC, European Society of Cardiology.

Microbiology of TAVR-PVE

Like all cases of endocarditis, identifying the causative organism is essential for the successful targeted management of TAVR-PVE. However, in the setting of severe presentation and critical illness, select patients may require empiric therapy prior to the identification of a causative organism (20). In fact, the causative organism may not be isolated in up to 12% of TAVR-PVE and in such cases, empiric therapy will be the cornerstone of treatment (40). Knowledge of the local epidemiology and microbiological profile of infections is essential to guide empiric therapy. This is particularly important for multi-drug resistant (MDR) pathogens which may complicate the course of treatment and increase mortality. Hence, medical centers are encouraged to identify their local epidemiology to guide empirical therapy in alignment with antimicrobial stewardship principles.

In most reports of TAVR-PVE, Gram-positive organisms seem to be predominant (28). In a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis, Streptococcus spp. (25.3%), Staphylococcus spp. (25.3%) and Enterococcus spp. (24.1%) were the most commonly reported causative organisms of TAVR-PVE (table 1) (20). Among staphylococci and enterococci, S. aureus and E. faecalis were the predominant species (60% and 65.8% respectively). Interestingly, enterococci have been much more reported in TAVR-PVE compared to SAVR-PVE, possibly owing to the trans-femoral access of TAVR (41). Moreover, enterococci seem to be more common in TAVR-PVE in patients who have SEVs rather than BEVs (42).

Table 1.

Most commonly reported causative organisms from cohorts of TAVR-PVE patients. CoNS, coagulase-negative staphylococci.

Table 1.

Most commonly reported causative organisms from cohorts of TAVR-PVE patients. CoNS, coagulase-negative staphylococci.

| |

S. aureus |

CoNS |

Enterococcus spp.

|

Viridans group streptococci |

Gram-negative bacilli |

Panagides et al. (15)

(N=553)

|

24.7%

of which 18.2% methicillin-resistant |

17.5%

of which 28.9% methicillin-resistant |

25.9% |

17.5% |

|

Panagides et al. (43)

(N=272)

|

20.6% |

18.8% |

|

27.6% |

|

Del Val et al. (44)

(N=552)

|

24%

of which 16% methicillin-resistant |

18.1%

of which 29.5% methicillin resistant |

25% |

19.2% |

|

Mentias et al. (45)

(N=1868)

|

19.7% |

|

15.5% |

20% |

|

Stortecky et al. (46)

(N=149)

|

21.5%

|

12.8% |

26.2% |

22.8% |

5.4% |

Regueiro et al. (16)

(N=245)

|

24% |

18.8% |

25.3% |

7% |

|

Bjursten et al. (18)

(N=103)

|

22.3% |

6.8% |

20.4%

(E. faecalis only) |

34%

|

|

Kolte et al. (47)

(N=224)

|

30.4%

of which 36.8% methicillin-resistant |

8%

of which 20.5% methicillin-resistant |

|

29.9% |

3.1% |

Although Gram-negative pathogens are rarely reported as causative organisms for TAVR-PVE, they are often responsible for other nosocomial infections after TAVR in hospitalized patients. For instance, a recent prospective cohort study of 303 patients reported that 17% of patients developed nosocomial infections following TAVR. In those patients, Gram-negative organisms were isolated in more than 60% of cultures (48). Additionally, urgent indication of TAVR, length of coronary care unit (CCU) stays, and need for blood transfusion were identified as independent risk factors for post-TAVR nosocomial infections on multivariate analysis (48). Since most of these infections were pneumonias and UTIs, the risk for secondary bacteremia is non-negligeable, and hence, such patients may be at increased risk for Gram-negative PVE. Gram-negative infections should also be considered in TAVR-PVE occurring early after TAVR as a meta-analysis suggests that the median time from TAVR to PVE was 1.1 months (IQR 0.9-6.2) for Gram-negative pathogens whereas it was 5.4 months (IQR 0.9-6.2) for Gram-positive bacteria (20).

Besides the increased incidence of enterococcal infection in the early phase after TAVR, and the association of early TAVR-PVE with hospital-acquired S. aureus, there are no notable differences in the microbiology of early (<1 year) and late (> 1 year) TAVR-PVE (45). However, since up to 52% of TAVR-PVE may be hospital-acquired, the possibility of nosocomial MDR organisms should be considered in cases of early TAVR-PVE (16). A recently published multicenter study including 91 patients with very early TAVR-PVE (<30 days after TAVR) reported that up to one third of the isolated Staphylococcus spp. (35.2%) were methicillin-resistant, the second most common organism was Enterococcus spp. (34.1%) (49). These rates are comparable to those published from patients with endocarditis occurring after 30 days of TAVR. It should be noted that in up to 50 percent of TAVR-PVE the primary source of bacteremia cannot be identified (20). However, if identified a primary site of infection causing secondary bacteremia and IE can help guide empiric therapy by targeting the most likely causative organisms particularly when cultures are negative.

Fungal endocarditis in patients with a history of TAVR is rather rare but highly deadly. The reported rates of fungal TAVR-PVE range between 0.8% and 3% of all TAVR-PVE (9,16,45). Because of its low incidence, the true mortality of fungal TAVR-PVE is not well known. When compared with bacterial etiologies, it has been associated with an increased risk of mortality (aHR: 1.72; 95% CI: 1.23-2.39; p < 0.05) (45). Besides case reports of TAVR-PVE caused by Candida parapsilosis (50,51) and Histoplasma capsulatum (52,53), the microbiology of these fungal infections is hard to characterize given that most large studies do not report the genus nor species of causative fungal organisms. Fungal TAVR-PVE are challenging to treat given the high production of biofilm, difficulty of eradication, risk of relapse, and need for surgical intervention (54).

Blood culture negative endocarditis (BCNE) can greatly complicate the management of patients with endocarditis. Some studies have even reported rates as high as 70% (55). Notably, patients with BCNE may require prolonged duration of broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy which puts them at risk of adverse events such as drug toxicity and Clostridioides difficile infection. Most commonly, BCNE is due to exposure to antimicrobials prior to blood cultures or in cases of endocarditis caused by fastidious organisms (40). Novel diagnostic techniques other than standard blood cultures may help identify more causative organisms and offer more targeted antimicrobial therapy. Molecular sequencing techniques such as metagenomic next generation sequencing or targeted metagenomic sequencing and 16s rRNA PCR have been shown to improve the diagnostic yield in infective endocarditis, including PVE (56). Such advanced technologies can also be applied in patients with culture negative TAVR-PVE.

Infection Prevention and Control

The risk of TAVR PVE seems to be the highest during the first year, which might be possibly caused by the incomplete healing and occasional persistence of paravalvular leaks for up to 12 months after the procedure (27). Peri-procedural bacteremia may also contribute to this early increased risk (27). Hence, patients undergoing TAVR may benefit from peri-procedural antimicrobial prophylaxis (57). According to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, most patients receive peri-procedural prophylaxis with cephalosporins (61.8%) while others receive vancomycin (16%) or penicillin (22%) (9). Although cefazolin is the most commonly used agent, it exhibits no activity against Enterococcus spp. and hence, may not be the most appropriate agent for prophylaxis (58). The rationale behind the use of first or second generation cephalosporins is extrapolated from data on SAVR (59). Nevertheless, compared to SAVR, the likelihood of the involvement of enterococci is much higher (39). Additionally, Gram-negative organisms may be more frequent during the early period following TAVR-PVE (58). Hence, prophylactic regimens for use during cardiac surgery may not be adequate for TAVR. A subset of patients may also require intracardiac devices for conduction anomalies (e.g. pacemakers) which could further alter the microbiological profile of these infections (60). Patients admitted for TAVR often have multiple comorbidities causing frequent contact with healthcare and colonization with MDR pathogens (16). Eventually, prophylaxis should be guided by each center’s epidemiology and rates of resistance, most importantly the rates of MRSA and vancomycin resistant enterococci (VRE).

For the choice of antimicrobial prophylaxis, a single dose of amoxicillin-clavulanate (2.2 g intravenous 0-60 minutes prior to arterial puncture) or alternatively ampicillin-sulbactam (3 g intravenous 0-60 minutes prior to arterial puncture) is more appropriate than cephalosporins, with another dose to be administered if the procedure lasts for more than 2 hours (59). In the setting of beta-lactam allergy or high rates of MRSA, a single dose of IV vancomycin (15 mg/kg to be infused over one to 2 hours) or teicoplanin (9-12 mg/kg) may be administered. If local rates of VRE are high, teicoplanin (9-12 mg/kg) or daptomycin (>10 mg/kg) as single dose are suitable alternatives (61). Combination of vancomycin with a first- or second-generation cephalosporin may offer synergistic activity in settings with very high rates of MRSA (62). In patients with positive MRSA screening or diabetes with a BMI > 30 kg/m2, decolonization with chlorhexidine shower bath and nasal mupirocin ointment is recommended 1-6 weeks before the procedure (59). On the other hand, patients with frequent hospitalizations and risk factors for VRE colonization should be screened to optimize prophylactic therapy (63). In fact, a recently published prospective cohort including 290 patients who were admitted for trans-femoral vascular interventions (angiography, TAVR, foramen closure) reported that enterococci were isolated in 16.6% of patients prior to disinfection and 1.4% after disinfection (64). Moreover, special attention should be given to skin care, oral and dental hygiene, dialysis catheters and other invasive catheters and optimizing serum glucose levels. There is little evidence on the benefits of longer duration of periprocedural antimicrobial prophylaxis. For instance, a retrospective study comparing one day of prophylaxis regimen with cefuroxime compared to more than 3 days regimen in 450 patients undergoing TAVR showed no advantage of a longer regimen. Longer duration of prophylaxis was associated with a significantly higher incidence of C. difficile colitis (4% vs 0.4% p=0.01) (65).

Infection control and prevention measures should be implemented during TAVR procedures to minimize the risk of nosocomial infections, which are often caused by MDR pathogens that further complicate the management. Unlike SAVR which is performed in the operating room (OR) where strict, evidence-based infection control measures are implemented, TAVR might be performed in a catheterization lab or a hybrid OR where strict infection measures are not applied. However, a recent study showed no difference in the rates of PVE in patients who underwent TAVR in a hybrid OR compared to those who underwent the procedure in a catheterization laboratory (16). Nevertheless, the infection control and prevention measures in a diagnostic catheterization laboratory may be insufficient for an implanted prosthetic devise (59). Restriction of traffic inside the room, use of surgical hand hygiene, sterile gowns and gloves, wearing masks, pre-procedural chlorhexidine showers, and unpacking of the valve immediately prior to implantation are all examples of practices that might help minimize the risk of infection, despite the lack of evidence (59). Although there are no data comparing chlorhexidine and iodine for vascular access sterilization in TAVR, data may be extrapolated from studies showing superiority of chlorhexidine at preventing post-procedural BSI in central vascular lines or surgical procedures (66,67).

Despite the absence of randomized trials assessing the benefits of prophylaxis in this subset of patients, the American Heart Association (AHA) and the ESC, recommend antimicrobial prophylaxis before dental interventions involving the gingiva, genitourinary, gastrointestinal procedures, and TEE for high-risk patients including those with a history of TAVR (34). This has become debatable with reports confirming greater adverse events from antimicrobial prophylaxis prior to such procedures than benefits. In fact, it is estimated that the risk of bacteremia is higher during routine daily activities such as tooth brushing and picking than during dental visits, hence, antibiotic prophylaxis would avoid few, if any, episodes of endocarditis (68). If prophylaxis is chosen, the agent of choice is oral amoxicillin given as a single oral dose of 2 g, but alternative oral (cephalexin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, doxycycline) and intravenous (ampicillin, cefazolin, ceftriaxone) agents are acceptable for patients who are allergic to penicillin and/or cannot tolerate oral intake (69). Patients should be educated about their increased risk of endocarditis, and the importance of avoiding activities that increase the risk of bacteremia such as piercings, tattoos, and intravenous (IV) drug use, and to maintain proper dental hygiene.

Management Challenges

Surgical Intervention

The dogma in various infections is that source control, particularly those involving foreign bodies, is highly advisable as it can drastically reduce the pathogen inoculum, eradicate the source, and substantially reduce mortality (70). Source control in TAVR-PVE require surgical intervention and advantages should be carefully weighed against surgical risks. In fact, many patients who have undergone TAVR have multiple comorbidities and contraindications that put them at a high operative risk (16). Most commonly, surgical interventions include retrieval of the large prosthetic frame adherent to the annulus and ascending aorta, valve replacement and sometimes replacement of the aortic root, and may prove to be very challenging (9).

Once TAVR-PVE is diagnosed, the cardiac surgery team should be consulted. However, there is no consensus regarding the absolute need for surgical intervention for the management of TAVR-PVE as most evidence is derived from observational studies and no randomized trials have compared surgical management to conservative management with antimicrobials alone. In light of the absence of guidelines that are specific to TAVR-PVE, extrapolating from the guidelines on the management of PVE may be appropriate at this time while more conclusive evidence emerges. As stated earlier, a multidisciplinary approach involving all stakeholders is warranted alongside a meticulous surgical risk assessment. The 2015 AHA guidelines recommend surgery for all cases of PVE (71). On the other hand, the ESC 2015 guidelines regarding the management of infective endocarditis recommend surgical intervention for PVE cases only when there are concerns for cardiogenic shock of valvular origin, uncontrolled infection (persistent bacteremia, abscess, enlarging vegetation, fistula, false aneurysm), fungal or resistant bacterial organisms, and embolic threats (large vegetations) (34).

The first registry reporting outcomes of surgical interventions versus conservative management for TAVR-PVE included 205 patients. Surgery was only performed in 14.8% of patients despite the fact that 81.2% of them had at least one indication for surgery according to the aforementioned guidelines. Most importantly, surgery was not associated with a reduced in-hospital death (29.7% vs 37.1%, P=0.39). However, these findings may have been caused by selection bias (16). Similarly, an unmatched cohort comparing outcomes between 20 patients with TAVR who underwent surgical management and 44 patients who were managed conservatively also did not find a significant difference in mortality among both groups. When subjects were matched, all-cause 1-year mortality was also not significantly different among both groups (65% in patients treated surgically vs 75% in patients treated with antibiotics alone, P=0.49) (72). Additionally, another multicenter study including 584 patients with TAVR-PVE of which 19% underwent surgery and 81% were managed with antimicrobials only did not find a significantly different in-hospital and 1-year all-cause mortality. Notably, surgery was less likely to be performed in older patients, those with neurologic symptoms, and more likely to be performed in those with large vegetations >10 mm, peri annular complications, systemic embolization and persistent bacteremia (73). In other reports, patients who effectively underwent surgery were also more likely to be young, have a lower baseline Surgical Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score reflecting a lower operative risk, and a higher glomerular filtration rate (74). Given that most observational studies mention selection bias regarding surgical management and did not report surgical outcomes in specific subpopulations (e.g. patients with uncontrolled infection, fungal or S. aureus infection), randomized trials are needed to further understand the role of surgical intervention in the management of TAVR-PVE.

Antimicrobial Treatment

Empirical Antimicrobial Therapy of TAVR-PVE

The course of infective endocarditis can be insidious. In hemodynamically stable patients with a subacute illness, antimicrobial therapy can be deferred until every attempt is made to identify the causative organism and susceptibility results (40). However, in cases of severe illness such as septic or cardiogenic shock, empirical therapy should be initiated, preferably after 3 sets of blood cultures are drawn from different sites if possible (34). The AHA’s guidelines, which have been endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), recommend that infectious diseases specialists be consulted to guide with the proper empirical regimen (40) which should cover staphylococci, enterococci and streptococci, being the most encountered pathogens in TAVR-PVE. The spectrum should be guided by local epidemiological data and rates of resistance. Additionally, when selecting antimicrobial agents, risk factors for MDR pathogens (intensive care unit (ICU) admission, critical illness, indwelling catheters, central lines, recent broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy) and the possibility of concomitant bacterial and fungal infections should be considered in certain scenarios.

A combination of bactericidal antibiotics including aminoglycosides is recommended. The rationale behind using aminoglycosides lies in its synergistic effect when combined with cell-wall inhibitors (B-lactams and glycopeptides) which optimizes their bactericidal activity (34). The choice of coverage of MRSA during empirical antimicrobial therapy should be guided by the local epidemiology and rates of community-acquired and hospital-acquired MRSA. Empirical coverage of MRSA in all critically ill patients with TAVR-PVE is reasonable with vancomycin to be empirically initiated with de-escalation once identification and susceptibility results are available. The choice of empirical vancomycin is also appropriate given the high prevalence of enterococci among causative organisms of TAVR-PVE. The addition of rifampicin is not warranted for empirical therapy. Although it is characterized by its ability to penetrate adherent prostheses and biofilms and exhibits a potent bactericidal effect on S. aureus organisms, rifampicin should not be administered until 3-5 days after effective antimicrobial therapy when the bacterial load has decreased and the risk of treatment-emergent resistance is lower (34,75,76). On the other hand, Pseudomonas aeruginosa is rarely a causative organism of infective endocarditis (77). However, empirical antipseudomonal therapy should be initiated in critically ill patients with risk factors for P. aeruginosa infection (78). A combination of a beta-lactam agent such as ceftazidime, cefepime or piperacillin-tazobactam in addition to vancomycin and an aminoglycoside (gentamicin or amikacin) is appropriate. However, if local rates of MDR P. aeruginosa are high, or if the patient is known to be colonized with MDR organisms, a carbapenem or a novel beta-lactam-beta-lactamase inhibitor combination (ceftazidime-avibactam, or ceftolozane-tazobactam) should be considered. It should be reiterated that there are no randomized trials comparing different antimicrobial agents for TAVR-PVE, and recommendations are extrapolated from studies where the majority of patients had undergone prosthetic SAVR.

Directed Antimicrobial Therapy of TAVR-PVE

Directed therapy for TAVR-PVE is similar to SAVR-PVE and should be guided by susceptibility profile as per the international guidelines (34,40). There are no studies that have compared head-to-head various anti-Gram-positive agents specifically in TAVR-PVE. Agents with good biofilm activity are preferred.

As mentioned previously, the epidemiology of fungal TAVR-PVE is unclear given the rarity of this event. Hence, the antimicrobial management is highly variable depending on the causative fungus. Based on the recommendations of AHA guidelines on PVE, a combined medical and surgical approach is recommended for the management of TAVR-PVE caused by Candida spp. (40). Nonetheless, the guidelines stem from conflicting evidence regarding the impact of surgical intervention on mortality (79,80). Moreover, no current data has shown superiority of any antifungal agent compared to the other. Hence, the use of lipid formulation of amphotericin B (3 to 5 mg/kg intravenously daily) with or without flucytosine (25 mg/kg orally 4 times daily) or echinocandins at a high dose (caspofungin 150 mg IV daily, micafungin 150 mg IV daily, anidulafungin 200 mg IV daily), as advised by the AHA guidelines, is acceptable (54). Speciation and susceptibility testing of all fungal isolates should be done to determine appropriateness of treatment and allow for potential step-down therapy if possible. Even if surgery is performed, antifungal therapy should be continued for at least 6 weeks. Treatment duration may be extended according to clinical and laboratory parameters as the risk of relapse is high in candida endocarditis [ref]. If surgery is not performed, lifelong suppression with an oral azole (according to the isolate susceptibilities) may be warranted (54).

Duration of Therapy

Controlling duration of therapy is among the most important pillars of antimicrobial stewardship. As the evidence accumulates against long duration of treatment, most guidelines have moved towards recommending shorter duration of therapy for various infections particularly for Gram-negative pathogens (81). However, little to no data is available about the efficacy of a shorter duration of treatment for PVE. The AHA and ESC’s guidelines both recommend a minimum duration of antibiotics of 6 weeks for PVE compared to NVE. In fact, prolonged treatment is needed for all types of PVE as biofilms tend to be formed on the implanted valve and bacteria may remain dormant in the vegetations and display tolerance towards most antimicrobials (34). For SAVR-PVE patients who undergo surgery and have positive cultures from valvular material, a post-operative antibiotic course of six weeks is recommended. On the other hand, for patients with negative intra-operative cultures the course can be shortened to 2 weeks. However, because of the high mortality and risk for devastating complications of TAVR-PVE, until more studies are available, we favor at least 6 weeks of antimicrobial therapy regardless of the status of intraoperative cultures (71).

Route of Administration

It is recommended that all patients with endocarditis (including those with NVE and PVE) receive initial parenteral treatment. In fact, parenteral administration may provide a more predictable serum concentration than oral drugs and enhance bacterial killing (82). However, some studies have attempted transitioning to oral therapy, in alignment with antimicrobial stewardship principles. A recent RCT including 400 patients with endocarditis, of which 26% had prosthetic valves found that transitioning to oral therapy after a minimum of 10 days of parenteral therapy was non-inferior to completing the treatment course parenterally (83). The data from this study should be cautiously extrapolated to TAVR-PVE, since the population size was small, and heterogenous and none of the patients had severe illness. Because of the lack of evidence on the safety of transitioning to oral therapy in TAVR-PVE, we believe that a full course of parenteral antimicrobial treatment is recommended to optimize patients’ outcomes.

Conclusion

TAVR-PVE has emerged in light of the increasing number of patients undergoing TAVR. Contrarily to SAVR-PVE, clinicians have less experience identifying, diagnosing, and managing TAVR-PVE. Studies have shown a similar rate of incidence between PVE in patients with SAVR and TAVR but have identified different risk factors. Notably, younger age and male sex are the most important non-modifiable ones. Additionally, other co-morbidities and procedural risk factors may play a role in TAVR-PVE. Most importantly, TAVR-PVE tends to have a different microbiological profile than SAVR-PVE. The overwhelming prevalence of enterococci in TAVR-PVE has major implications regarding empiric therapy, peri-procedural and post-procedural prophylaxis, and infection prevention and control measures. As little evidence exists regarding the management of these infections, clinicians have no choice but to extrapolate from previous guidelines on the management of SAVR-PVE. The decision for surgical intervention and choice of empirical antimicrobial therapy should be personalized and adjusted to the local epidemiology and rates of resistance. Although most clinicians have promoted transitioning to shorter duration of therapy or to oral therapy, there is not enough evidence to recommend such practices in TAVR-PVE.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SSK.; writing—original draft preparation, JZ, FA, SK, SW; writing—review and editing, JZ, FA, SK, SW; supervision, SSK. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding nor grants were used for the writing of this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Percutaneous Transcatheter Implantation of an Aortic Valve Prosthesis for Calcific Aortic Stenosis | Circulation [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 28]. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.CIR.0000047200.36165.B8.

- Procedural Volume and Outcomes for Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement | NEJM [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 28]. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmsa1901109.

- Cahill TJ, Chen M, Hayashida K, Latib A, Modine T, Piazza N, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: current status and future perspectives. Eur Heart J. 2018 Jul 21;39(28):2625-34. [CrossRef]

- Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Balloon-Expandable Valve in Low-Risk Patients | NEJM [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 28]. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa1814052.

- Lnu K, Ansari S, Mahto S, Gada H, Mumtaz M, Loran D, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement associated infective endocarditis case series: broadening the criteria for diagnosis is the need of the hour. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021 Dec;21(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Olsen NT, De Backer O, Thyregod HGH, Vejlstrup N, Bundgaard H, Søndergaard L, et al. Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Apr;8(4):e001939. [CrossRef]

- Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, Miller DC, Moses JW, Tuzcu EM, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2015 Jun 20;385(9986):2477-84. [CrossRef]

- Thyregod HGH, Ihlemann N, Jørgensen TH, Nissen H, Kjeldsen BJ, Petursson P, et al. Five-Year Clinical and Echocardiographic Outcomes from the Nordic Aortic Valve Intervention (NOTION) Randomized Clinical Trial in Lower Surgical Risk Patients. Circulation. 2019 Feb 1; [CrossRef]

- Amat-Santos IJ, Ribeiro HB, Urena M, Allende R, Houde C, Bédard E, et al. Prosthetic valve endocarditis after transcatheter valve replacement: a systematic review. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Feb;8(2):334-46. [CrossRef]

- Summers MR, Leon MB, Smith CR, Kodali SK, Thourani VH, Herrmann HC, et al. Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis After TAVR and SAVR: Insights From the PARTNER Trials. Circulation. 2019 Dec 10;140(24):1984-94. [CrossRef]

- Thourani VH, Kodali S, Makkar RR, Herrmann HC, Williams M, Babaliaros V, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement versus surgical valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients: a propensity score analysis. Lancet Lond Engl. 2016 May 28;387(10034):2218-25. [CrossRef]

- Prasitlumkum N, Vutthikraivit W, Thangjui S, Leesutipornchai T, Kewcharoen J, Riangwiwat T, et al. Epidemiology of infective endocarditis in transcatheter aortic valve replacement: systemic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Med Hagerstown Md. 2020 Oct;21(10):790-801. [CrossRef]

- Jiang W, Wu W, Guo R, Xie M, Yim WY, Wang Y, et al. Predictors of Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Meta-Analysis. Heart Surg Forum. 2021 Feb 10;24(1):E101-7. [CrossRef]

- Tabata N, Al-Kassou B, Sugiura A, Shamekhi J, Sedaghat A, Treede H, et al. Predictive factors and long-term prognosis of transcatheter aortic valve implantation-associated endocarditis. Clin Res Cardiol Off J Ger Card Soc. 2020 Sep;109(9):1165-76. [CrossRef]

- Panagides V, Abdel-Wahab M, Mangner N, Durand E, Ihlemann N, Urena M, et al. Sex Differences in Infective Endocarditis After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Can J Cardiol. 2022 Sep 1;38(9):1418-25. [CrossRef]

- Regueiro A, Linke A, Latib A, Ihlemann N, Urena M, Walther T, et al. Association Between Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement and Subsequent Infective Endocarditis and In-Hospital Death. JAMA. 2016 Sep 13;316(10):1083-92. [CrossRef]

- Mangner N, Woitek F, Haussig S, Schlotter F, Stachel G, Höllriegel R, et al. Incidence, Predictors, and Outcome of Patients Developing Infective Endocarditis Following Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Jun 21;67(24):2907-8. [CrossRef]

- Bjursten H, Rasmussen M, Nozohoor S, Götberg M, Olaison L, Rück A, et al. Infective endocarditis after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a nationwide study. Eur Heart J. 2019 Oct 14;40(39):3263-9. [CrossRef]

- Valdés C, Tomás I, Alvarez M, Limeres J, Medina J, Diz P. The incidence of bacteraemia associated with tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia. 2008 Jun;63(6):588-92. [CrossRef]

- Tinica G, Tarus A, Enache M, Artene B, Rotaru I, Bacusca A, et al. Infective endocarditis after TAVI: a meta-analysis and systematic review of epidemiology, risk factors and clinical consequences. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020 Jun 30;21(2):263-74. [CrossRef]

- Ando T, Ashraf S, Villablanca PA, Telila TA, Takagi H, Grines CL, et al. Meta-Analysis Comparing the Incidence of Infective Endocarditis Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. Am J Cardiol. 2019 Mar 1;123(5):827-32. [CrossRef]

- Mihara H, Shibayama K, Jilaihawi H, Itabashi Y, Berdejo J, Utsunomiya H, et al. Assessment of Post-Procedural Aortic Regurgitation After TAVR: An Intraprocedural TEE Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015 Sep 1;8(9):993-1003. [CrossRef]

- Athappan G, Patvardhan E, Tuzcu EM, Svensson LG, Lemos PA, Fraccaro C, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of aortic regurgitation after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: meta-analysis and systematic review of literature. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Apr 16;61(15):1585-95. [CrossRef]

- Kuttamperoor F, Yandrapalli S, Siddhamsetti S, Frishman WH, Tang GHL. Infectious Endocarditis After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Epidemiology and Outcomes. Cardiol Rev. 2019;27(5):236-41. [CrossRef]

- Habib G. Infective Endocarditis After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: The Worst That Can

Happen. J Am Heart Assoc Cardiovasc Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018 Aug 31;7(17):e010287.

- Butt JH, Ihlemann N, De Backer O, Søndergaard L, Havers-Borgersen E, Gislason GH, et al. Long-Term Risk of Infective Endocarditis After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Apr 9;73(13):1646-55. [CrossRef]

- Østergaard L, Lauridsen TK, Iversen K, Bundgaard H, Søndergaard L, Ihlemann N, et al. Infective endocarditis in patients who have undergone transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Aug 1;26(8):999-1007. [CrossRef]

- Khan A, Aslam A, Satti KN, Ashiq S. Infective endocarditis post-transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), microbiological profile and clinical outcomes: A systematic review. PLOS ONE. 2020 Jan 17;15(1):e0225077. [CrossRef]

- Chourdakis E, Koniari I, Hahalis G, Kounis NG, Hauptmann KE. Endocarditis after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a current assessment. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2018 Jan 1;15(1):61-5.

- Salaun E, Sportouch L, Barral PA, Hubert S, Lavoute C, Casalta AC, et al. Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis After TAVR: Value of a Multimodality Imaging Approach. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Jan 1;11(1):143-6. [CrossRef]

- Holland TL, Baddour LM, Bayer AS, Hoen B, Miro JM, Fowler VG. Infective endocarditis. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2016 Sep 1;2(1):1-22. [CrossRef]

- Pizzi MN, Roque A, Fernández-Hidalgo N, Cuéllar-Calabria H, Ferreira-González I, Gonzàlez-Alujas MT, et al. Improving the Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis in Prosthetic Valves and Intracardiac Devices With 18F-Fluordeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography Angiography: Initial Results at an Infective Endocarditis Referral Center. Circulation. 2015 Sep 22;132(12):1113-26. [CrossRef]

- Lancellotti P, Pibarot P, Chambers J, Edvardsen T, Delgado V, Dulgheru R, et al. Recommendations for the imaging assessment of prosthetic heart valves: a report from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging endorsed by the Chinese Society of Echocardiography, the Inter-American Society of Echocardiography, and the Brazilian Department of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 Jun;17(6):589-90. [CrossRef]

- Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 21;36(44):3075-128. [CrossRef]

- Saby L, Laas O, Habib G, Cammilleri S, Mancini J, Tessonnier L, et al. Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography for Diagnosis of Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis: Increased Valvular 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Uptake as a Novel Major Criterion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jun 11;61(23):2374-82. [CrossRef]

- Houard V, Porte L, Delon C, Carrié D, Delobel P, Galinier M, et al. Prognostic value of residual vegetation after antibiotic treatment for infective endocarditis: A retrospective cohort study. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 May 1;94:34-40. [CrossRef]

- Habib G. Management of infective endocarditis. Heart Br Card Soc. 2006 Jan;92(1):124–30.

- Mihos CG, Capoulade R, Yucel E, Picard MH, Santana O. Surgical Versus Medical Therapy for Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis: A Meta-Analysis of 32 Studies. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017 Mar;103(3):991-1004. [CrossRef]

- Lalani T, Chu VH, Park LP, Cecchi E, Corey GR, Durante-Mangoni E, et al. In-hospital and 1-year mortality in patients undergoing early surgery for prosthetic valve endocarditis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Sep 9;173(16):1495-504. [CrossRef]

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG, Tleyjeh IM, Rybak MJ, et al. Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications. Circulation. 2015 Oct 13;132(15):1435-86. [CrossRef]

- Infective Endocarditis After Surgical and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A State of the Art Review [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 28]. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/JAHA.120.017347.

- Prasitlumkum N, Thangjui S, Leesutipornchai T, Kewcharoen J, Limpruttidham N, Pai RG. Comparison of infective endocarditis risk between balloon and self-expandable valves following transcatheter aortic valve replacement: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2021 Jul;36(3):363-74. [CrossRef]

- Panagides V, del Val D, Abdel-Wahab M, Mangner N, Durand E, Ihlemann N, et al. Mitral Valve Infective Endocarditis after Trans-Catheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2022 Jun 1;172:90-7.

- Del Val D, Abdel-Wahab M, Linke A, Durand E, Ihlemann N, Urena M, et al. Temporal Trends, Characteristics, and Outcomes of Infective Endocarditis After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2021 Dec 6;73(11):e3750-8.

- Mentias A, Girotra S, Desai MY, Horwitz PA, Rossen JD, Saad M, et al. Incidence, Predictors, and Outcomes of Endocarditis After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in the United States. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020 Sep 14;13(17):1973-82. [CrossRef]

- Stortecky S, Heg D, Tueller D, Pilgrim T, Muller O, Noble S, et al. Infective Endocarditis After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Jun 23;75(24):3020-30. [CrossRef]

- Kolte D, Goldsweig A, Kennedy KF, Abbott JD, Gordon PC, Sellke FW, et al. Comparison of Incidence, Predictors, and Outcomes of Early Infective Endocarditis after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2018 Dec 15;122(12):2112-9. [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Conte G, Freitas-Ferraz AB, Nombela-Franco L, Jimenez-Quevedo P, Biagioni C, Cuadrado A, et al. Incidence, Causes, and Impact of In-Hospital Infections After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2016 Aug 1;118(3):403-9. [CrossRef]

- Very early infective endocarditis after transcatheter aortic valve replacement - Albert Einstein College of Medicine [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 28]. Available from: https://einstein.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/very-early-infective-endocarditis-after-transcatheter-aortic-valv.

- Morioka H, Tokuda Y, Oshima H, Iguchi M, Tomita Y, Usui A, et al. Fungal endocarditis after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR): Case report and review of literature. J Infect Chemother. 2019 Mar 1;25(3):215-7. [CrossRef]

- Carrel T, Eberle B. Candida Endocarditis after TAVR. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 3;380(1):e1. [CrossRef]

- Nelson AJ, Montarello NJ, Roberts-Thomson RL, Montarello N, Delacroix S, Chokka RG, et al. Fungal Obstruction of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Valve. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Aug;9(8):e004117. [CrossRef]

- Head SJ, Dewey TM, Mack MJ. Fungal endocarditis after transfemoral aortic valve implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv Off J Soc Card Angiogr Interv. 2011 Dec 1;78(7):1017-9. [CrossRef]

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2016 Feb 15;62(4):e1-50. [CrossRef]

- Topan A, Carstina D, Slavcovici A, Rancea R, Capalneanu R, Lupse M. Assesment of the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis after twenty-years. An analysis of 241 cases. Med Pharm Rep. 2015 Jun 19;88(3):321-6. [CrossRef]

- Haddad SF, DeSimone DC, Chesdachai S, Gerberi DJ, Baddour LM. Utility of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing in Infective Endocarditis: A Systematic Review. Antibiot Basel Switz. 2022 Dec 11;11(12):1798. [CrossRef]

- Otto CM, Kumbhani DJ, Alexander KP, Calhoon JH, Desai MY, Kaul S, et al. 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in the Management of Adults With Aortic Stenosis: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Mar 14;69(10):1313-46. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Martinez A, Cobo M, Munez E, Restrepo A, Fernandez-Cruz A. Searching for the best agent for antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Hosp Infect. 2018 Dec 1;100(4):458-9. [CrossRef]

- Conen A, Stortecky S, Moreillon P, Hannan MM, Franzeck FC, Jeger R, et al. A review of recommendations for infective endocarditis prevention in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. EuroIntervention J Eur Collab Work Group Interv Cardiol Eur Soc Cardiol. 2021 Feb 19;16(14):1135-40. [CrossRef]

- Cardiac implantable electronic device and associated risk of infective endocarditis in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement | EP Europace | Oxford Academic [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 28]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/europace/article/20/10/e164/4774615 . [CrossRef]

- Allegranzi B, Zayed B, Bischoff P, Kubilay NZ, de Jonge S, de Vries F, et al. New WHO recommendations on intraoperative and postoperative measures for surgical site infection prevention: an evidence-based global perspective. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Dec;16(12):e288-303. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen SCJ, Trinh TD, Zasowski EJ, Alosaimy S, Melvin S, Bhatia S, et al. 2250. Combination Vancomycin Plus Cefazolin for Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019 Oct 23;6(Suppl 2):S769. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds JL, Trudeau RE, Seville MT, Chan L. Impact of a vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) screening result on appropriateness of antibiotic therapy. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol ASHE. 2021 Nov 3;1(1):e41. [CrossRef]

- Widmer D, Widmer AF, Jeger R, Dangel M, Stortecky S, Frei R, et al. Prevalence of enterococcal groin colonization in patients undergoing cardiac interventions: challenging antimicrobial prophylaxis with cephalosporins in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Hosp Infect. 2022 Nov;129:198-202. [CrossRef]

- Gomes B, Geis NA, Leuschner F, Meder B, Konstandin M, Katus HA, et al. Periprocedural antibiotic treatment in transvascular aortic valve replacement. J Intervent Cardiol. 2018;31(6):885-90. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Chen JW, Guo B, Xu CC. Preoperative Antisepsis with Chlorhexidine Versus Povidone-Iodine for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2020 May;44(5):1412-24. [CrossRef]

- Chaiyakunapruk N, Veenstra DL, Lipsky BA, Saint S. Chlorhexidine Compared with Povidone-Iodine Solution for Vascular Catheter-Site Care. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Jun 4;136(11):792-801. [CrossRef]

- Lockhart PB, Durack DT. Oral microflora as a cause of endocarditis and other distant site infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1999 Dec;13(4):833-50, vi. [CrossRef]

- Prevention of Viridans Group Streptococcal Infective Endocarditis: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association | Circulation [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 28]. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000969.

- 2016 The American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) consensus guidelines: Surgical treatment of infective endocarditis: Executive summary - The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 28]. Available from: https://www.jtcvs.org/article/S0022-5223(17)30116-2/fulltext.

- 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines | Circulation [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 28]. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923#d1e11386.

- A L, C N, M DB, Jm S, F M, M B, et al. TAVR-associated prosthetic valve infective endocarditis: results of a large, multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet]. 2014 Nov [cited 2022 Dec 28];64(20). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25457406/.

- Mangner N, del Val D, Abdel-Wahab M, Crusius L, Durand E, Ihlemann N, et al. Surgical Treatment of Patients With Infective Endocarditis After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Mar 1;79(8):772-85.

- Mangner N, Leontyev S, Woitek FJ, Kiefer P, Haussig S, Binner C, et al. Cardiac Surgery Compared With Antibiotics Only in Patients Developing Infective Endocarditis After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Sep 4;7(17):e010027. [CrossRef]

- Miró JM, García-de-la-Mària C, Armero Y, Soy D, Moreno A, del Río A, et al. Addition of Gentamicin or Rifampin Does Not Enhance the Effectiveness of Daptomycin in Treatment of Experimental Endocarditis Due to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009 Oct;53(10):4172-7. [CrossRef]

- Garrigós C, Murillo O, Lora-Tamayo J, Verdaguer R, Tubau F, Cabellos C, et al. Fosfomycin-Daptomycin and Other Fosfomycin Combinations as Alternative Therapies in Experimental Foreign-Body Infection by Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013 Jan;57(1):606-10. [CrossRef]

- Essien F, Patterson S, Estrada F, Wall T, Madden J, McGarvey M. "TAVR Infected Pseudomonas Endocarditis": a case report. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2022;9:20499361221138460. [CrossRef]

- J Z, Sl S, Jr H, Sf H, Ss K. Antimicrobial Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Severe Sepsis. Antibiot Basel Switz [Internet]. 2022 Oct 18 [cited 2022 Dec 28];11(10). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36290092/ . [CrossRef]

- Steinbach WJ, Perfect JR, Cabell CH, Fowler VG, Corey GR, Li JS, et al. A meta-analysis of medical versus surgical therapy for Candida endocarditis. J Infect. 2005 Oct;51(3):230-47. [CrossRef]

- Arnold CJ, Johnson M, Bayer AS, Bradley S, Giannitsioti E, Miró JM, et al. Candida infective endocarditis: an observational cohort study with a focus on therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015 Apr;59(4):2365-73. [CrossRef]

- Haddad SF, Allaw F, Kanj SS. Duration of antibiotic therapy in Gram-negative infections with a particular focus on multidrug-resistant pathogens. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2022 Dec 1;35(6):614-20. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hasan MN, Rac H. Transition from intravenous to oral antimicrobial therapy in patients with uncomplicated and complicated bloodstream infections. Clin Microbiol Infect Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020 Mar;26(3):299-306. [CrossRef]

- Iversen K, Ihlemann N, Gill SU, Madsen T, Elming H, Jensen KT, et al. Partial Oral versus Intravenous Antibiotic Treatment of Endocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 31;380(5):415-24. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).