1. Introduction

Tensile structures have become very popular forms during the last decades. The innovative shapes are attractive to designers and ordinary people. However, while typical buildings and heavy structures are sensitive to earthquake forces, tensile membranes as lightweight structures are susceptible to the effects of wind loads. In light of limited design guides and standard codes available such as the European design guide for tensile surface structures [

1] and ASCE/SEI 55-16 [

2], few tensile membrane forms were investigated for wind pressure coefficient. Because of such a small number of investigations, the need for broader wind simulation on the tensile membrane structures has been emphasized in recent publications. With the diversity in forms and complicated shapes of tensile structures, it is important to investigate more complicated forms against the dynamic effect of wind load. Furthermore, appropriate wind pressure information is necessary to provide confidence in the load estimation and design processes and provide the much-needed extension of building standards that can result in the safe and practical design of tensile membrane structures.

Holmes and Wood [

3] investigated the main venue of the Sydney 2000 Olympics as a saddle shape membrane stadium in order to obtain the wind mean pressure through wind tunnel tests. The effects of aspect ratio for ridge-valley tensile membrane structures (rise-span ratio and evas height) as well as different wind directions, were studied by Xiaoying et al. [

4]. Prototyping methodology for hyperbolic paraboloid roof structures using a wind tunnel in order to obtain the mean wind pressure coefficient was investigated by Colliers et al. [

5]. Rizzo and Ricciardelli [

6] conducted the envelope of experimental wind tunnel test as the design pressure coefficients for hyperbolic paraboloid roofs with circular and elliptical plans. Bartko et al. [

7] assembled the wind direction, wind speed, and wind pressure information on full-scale measurements of the low slope of tensile membrane roofs.

Chavez et al. [

8] presented the results of in-situ wind load measurements on a commercial building with a low-slope membrane roof, and the effect of assembly construction on the wind-induced pressure of membrane roofs. Dong and Ye [

9] investigated the wind pressure distribution and the effect of conical vortices on saddle roofs. The geometry of structures plays an important role in calculating the wind pressure distribution on the surface of the roof and walls of a building. Roy and Singh [

10] presented the effect of wind direction and the roof slope on the wind pressure coefficient on the roof of a square plan pyramidal low-rise building by using CFD simulation. RANS turbulent model (realizable k–ε model) was employed for the pressure coefficient on the roof of the building model.

When a wind load is applied to a structure, it has basically two elements, i.e., lift force and drag force and both may be positive or negative wind pressures. It was observed that drag force leads to a rise in surge and heave reactions, but the impact of the current drag is usually determined by the extent of the wave energy spectrum [

11]. Colliers et al. [

12] investigated distributions of average pressure coefficient using CFD RANS simulations over double-curved roof and canopy structures with various shape characteristics due to very small turbulence. Standard k-ε, realizable k-ε, and SST k-ω were used to investigate the average wind pressure distributions for hyperbolic paraboloid form. Few studies examined the aerodynamic effect of spatial structures such as conical form and canopies [

13,

14], hypar roof [

15], large-scale membrane structure [

16], and conical canopies as reversed type [

17,

18]. The main concern that needs to specify is how the aerodynamic parameters would be changed by various wind directions, in particular for TMS that are sensitive to wind load as well as orientations. This approach provides insight into the critical scenario of the structural design of TMS and general forms against wind load. The steady-state RANS turbulence such as standard k-ε and k-ω SST as well-known and accurate enough turbulence models in aerodynamics are employed to perform flow simulation around structural forms. The effect of wind direction has a great impact on Cp-distribution of tensile membrane surface, which few studies [

12] were working on it, so this would be an important research gap to investigate. The results illustrate which direction regarding positive and negative wind pressure is the most critical case of the wind load. However, recent studies such as [

19] investigated the Cp value for the single direction of wind load.

The current research aims to study the effect of wind directions on aerodynamic parameters such as Cp distribution for classical tensile membrane forms and general shapes. In particular, this research focuses on the prediction of the mean Cp distribution after nonlinear form-finding analysis that is imposed by surface pre-tensioning in order to find the final shape of the TMS. The selected shapes, such as conical, ridge and valley, and saddle are basic from the TMS that few papers were undertaken aerodynamic simulation on them. The wind forces are calculated for each wind orientation in 3 directions. Knowledge of aerodynamics helps the engineer to have a better assessment of wind load of irregular forms that are not covered by standards. In the first part of the article, the turbulence model and validation case based on the experimental test will be introduced; after that, the geometry of different examples and form-finding analysis will be discussed, then the result of the CFD simulation regarding wind directions will be presented.

3. Results and Discussion

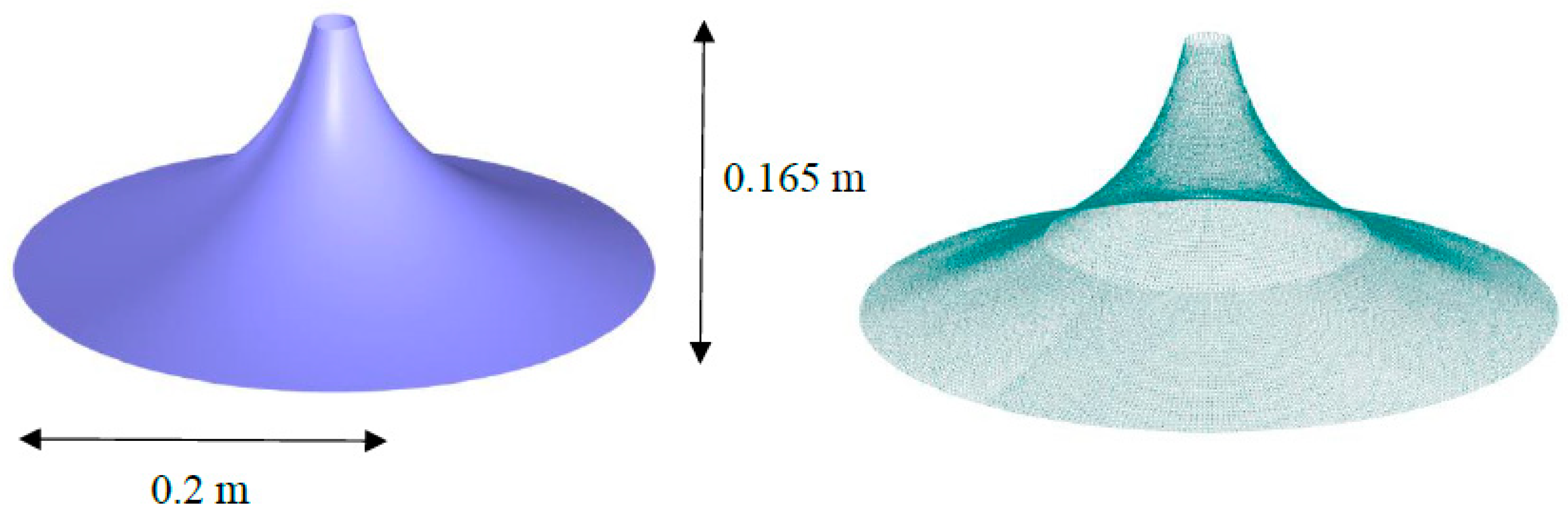

The average wind pressure distribution as diagrams, contours and wind force coefficient are investigated based on seven wind orientations for general and tensile surface forms. The SST k-ω turbulence model using enhanced wall function is employed to perform CFD simulation. For the evaluation of the laminar sub-layer with fine mesh, one equation relationship is employed, and for the assessment of the turbulent part of the boundary layer, a transition to a log-low function is used. These scalable improvements over the conventional wall functions can be obtained by the application of y+ in conjunction with increased wall treatment. It's possible that the restriction requiring the near-wall mesh to be adequately fine everywhere will impose an excessively high level of computing demand. The first form is a conical membrane shape that the geometry of the shape illustrates in

Figure 7; surface pre-tensioning equal to 2.5 kN/m is applied, as well as the projection form-finding procedure was performed in Dlubal RFEM. The scale of wind tunnel analysis is selected at 1:25 same as the validation reference.

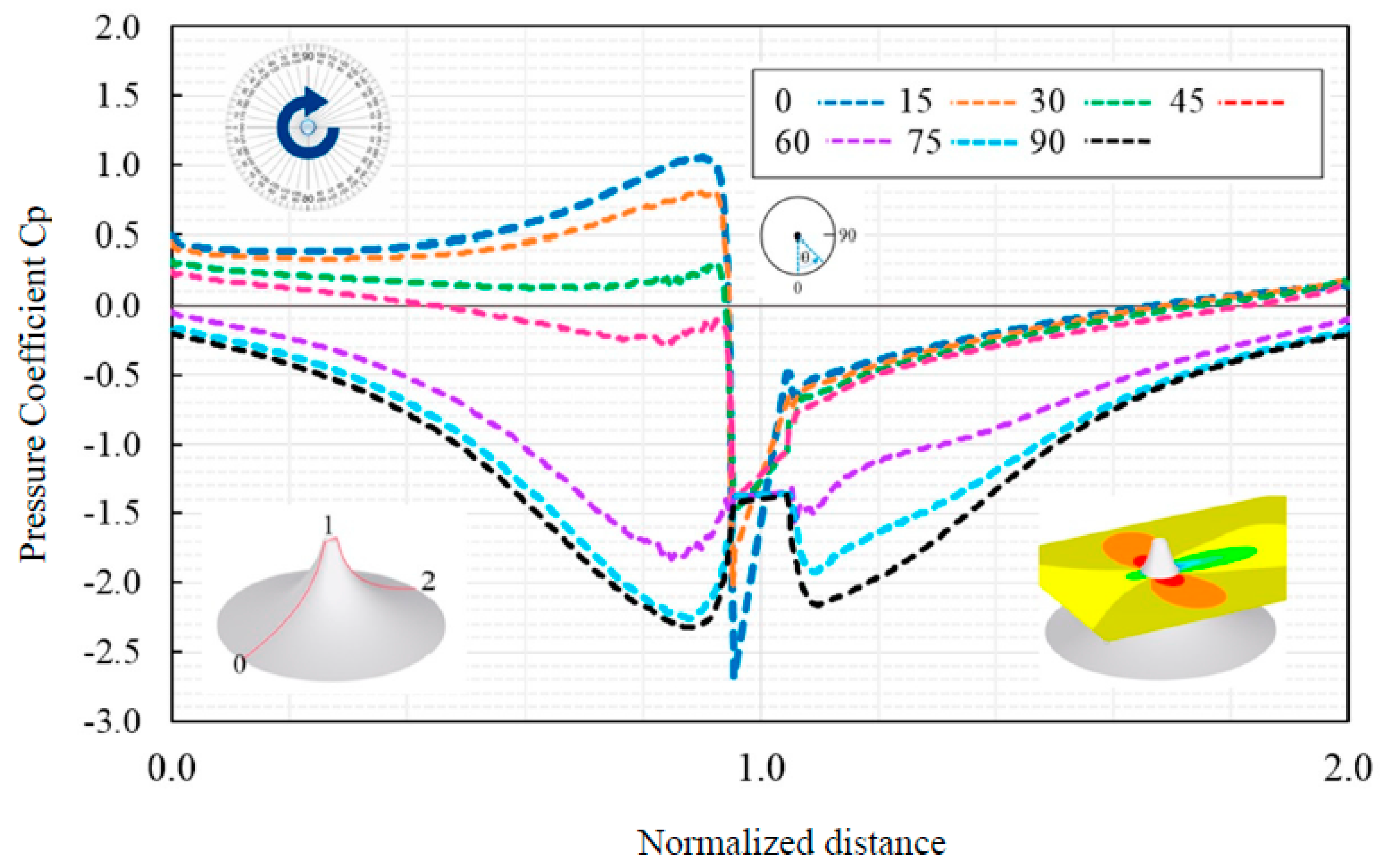

The wind flow analysis is investigated for seven wind directions, including θ=0,15,30,45,60,75,90

o which represent in

Figure 8. The average wind pressure distribution is obtained for each vertical probe line based on different orientations in

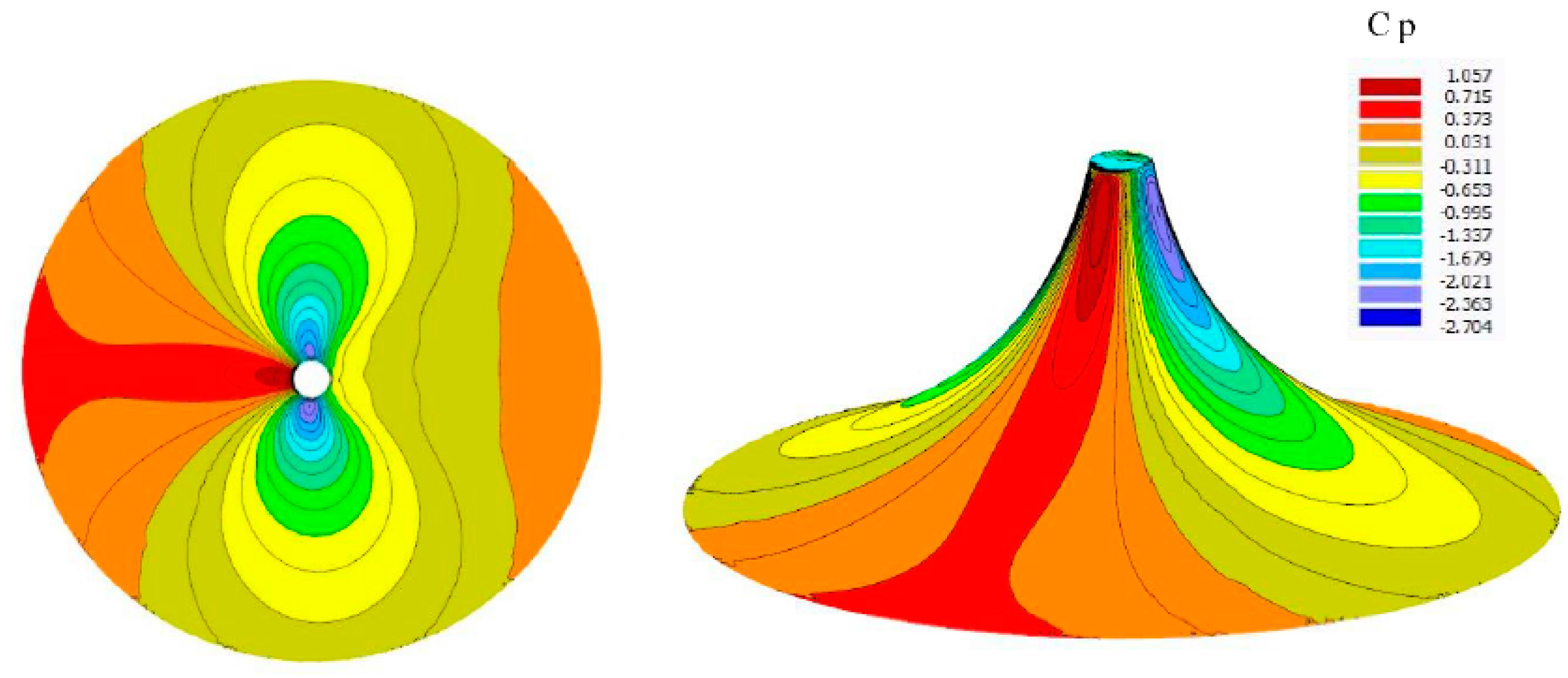

Figure 8, also by using a normalized line, the trend of distribution becomes apparent. Because of the symmetric form of conical, the results are independent of wind directions, and just a single simulation is enough for it. The maxim suction area is related to the top side near to apex of the conical shape. A clear relation between the increments in direction and the shift in the mean Cp-distributions is apparent. The most noticeable wind suction values are obtained at the top zones and reduce towards the downwind area of the roof. In addition, the contour of wind pressure is graphically demonstrated for the whole domain in

Figure 9. According to the symmetry form of conical form, the Cp-distribution does not vary with wind directions, so for a single wind direction, Drag forces and wind coefficient are calculated in

Table 2. Also, mesh independency is investigated by several numbers of cells, as can be seen in 1.5 million cells; the results are not changed regarding the next cell number.

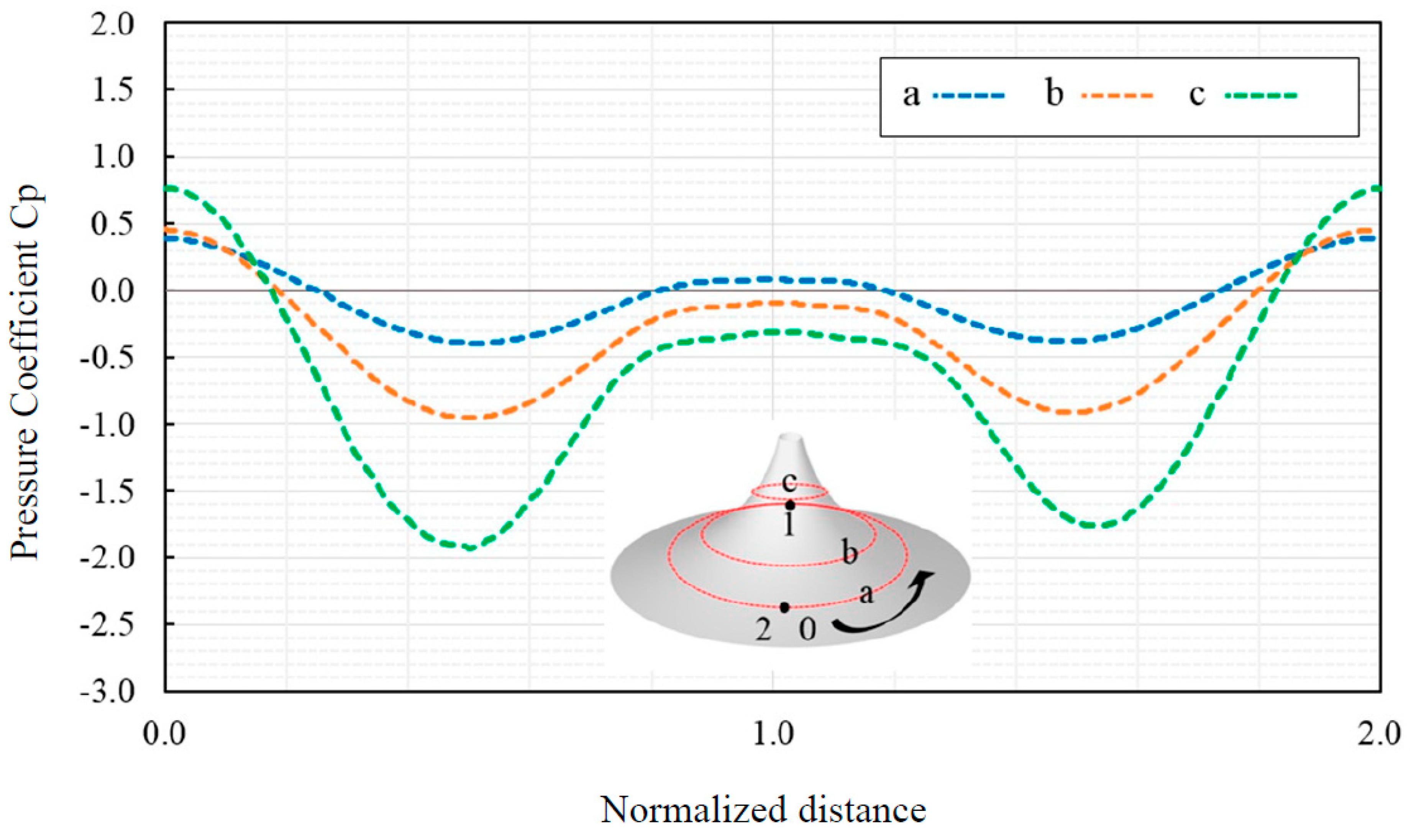

Also, the horizontal Cp-value is demonstrated in

Figure 10 which 3 probe lines are selected (same distance to each lines) on the horizontal surface direction. The upper and lower value of the average wind pressure coefficient can be seen through normalized distance, in which the peak value of Cp is important on the windward and leeward of the conical surface.

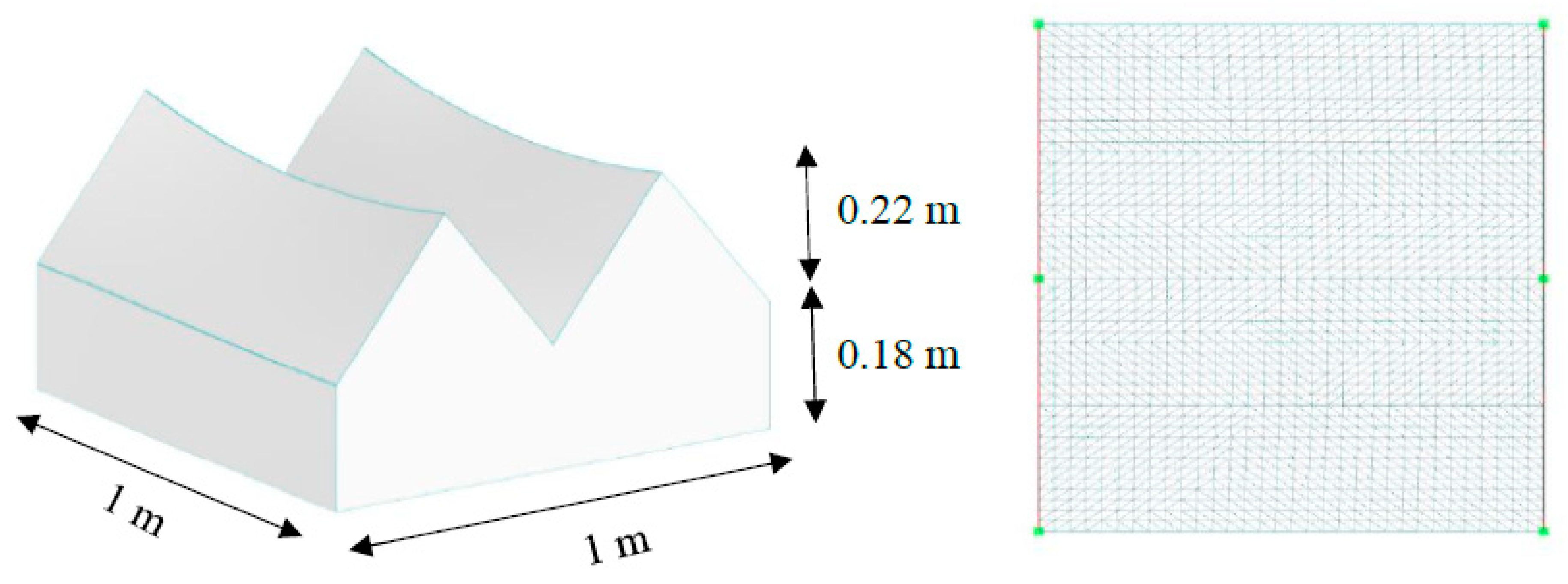

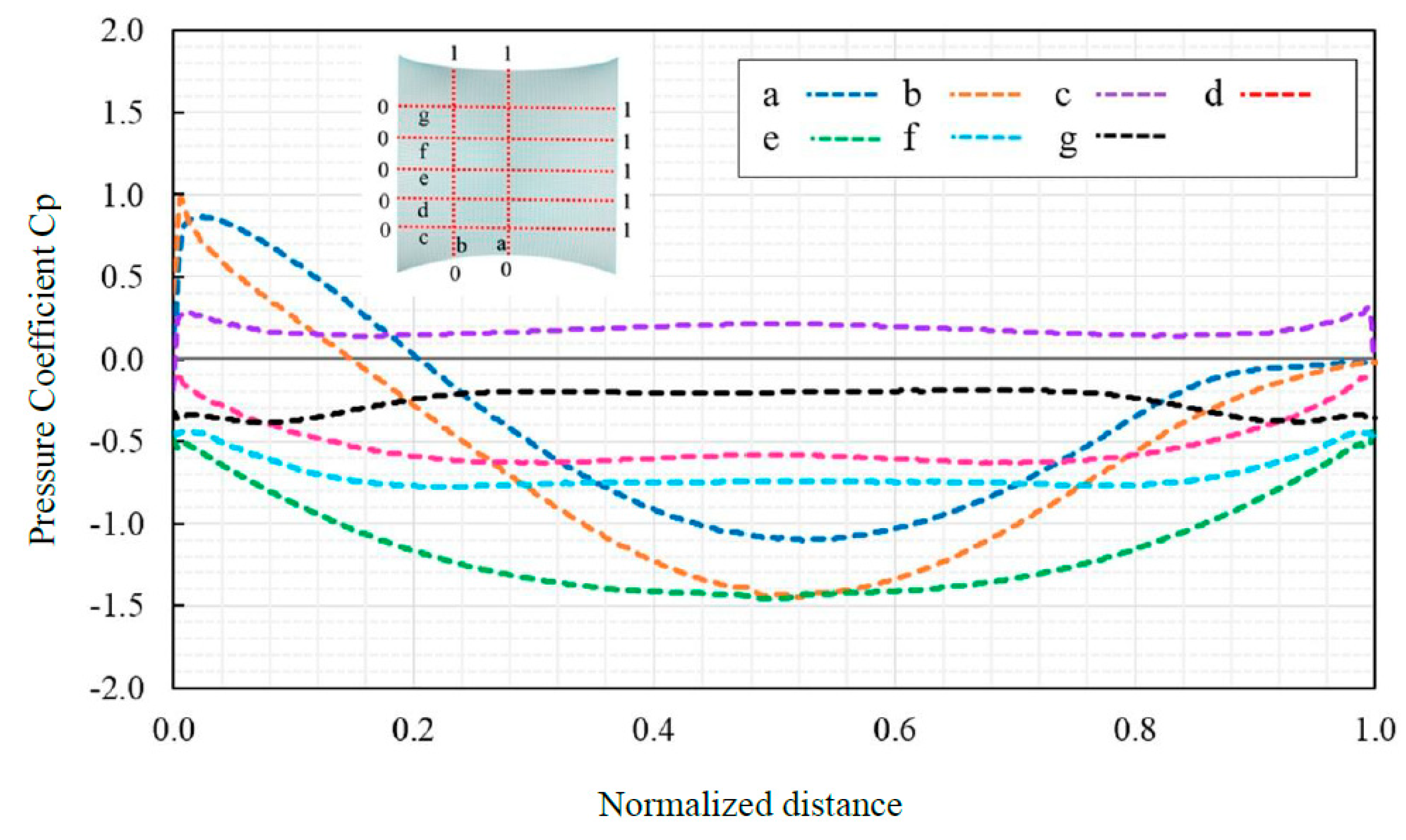

The next form is the closed tensile ridge valley roof that geometry dimension is illustrated in

Figure 11., the pre-tension surface force is applied equally to 2.5 kN/m in order to perform form-finding analysis in RFEM after that final form was transferred to RWIND Simulation for starting wind simulation procedure. The computational mesh became independent in 2,782,823 cells. Wind parameters are obtained due to wind direction for this shape, so seven wind angles are selected to evaluate Cp-value for each direction in

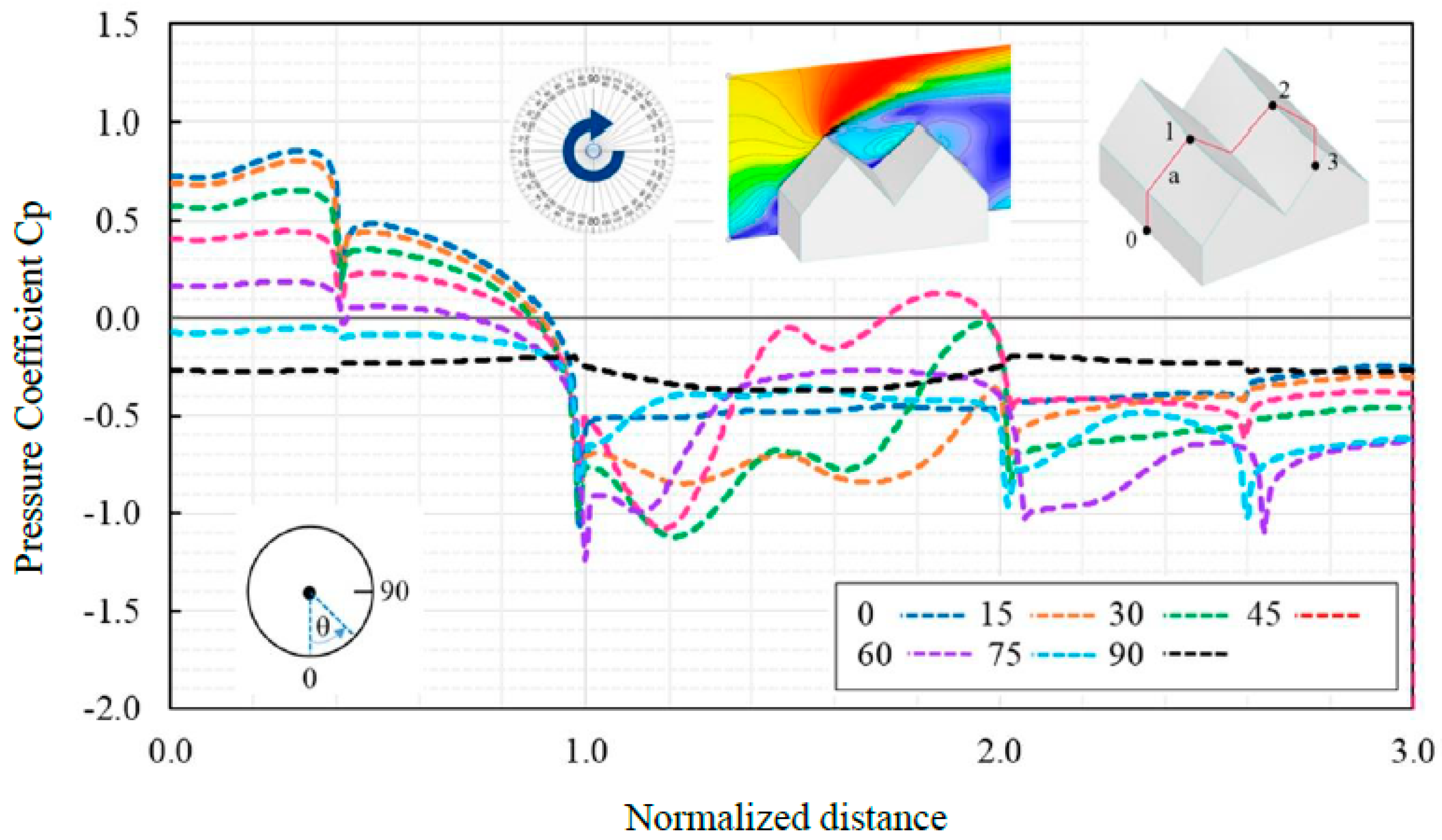

Figure 12.

An obvious relation between the increments in wind directions and the shift in the mean Cp-distributions is apparent. The most noticeable wind suction values are obtained at near top edges and fluctuate towards the downwind area of the roof due to

Figure 12.

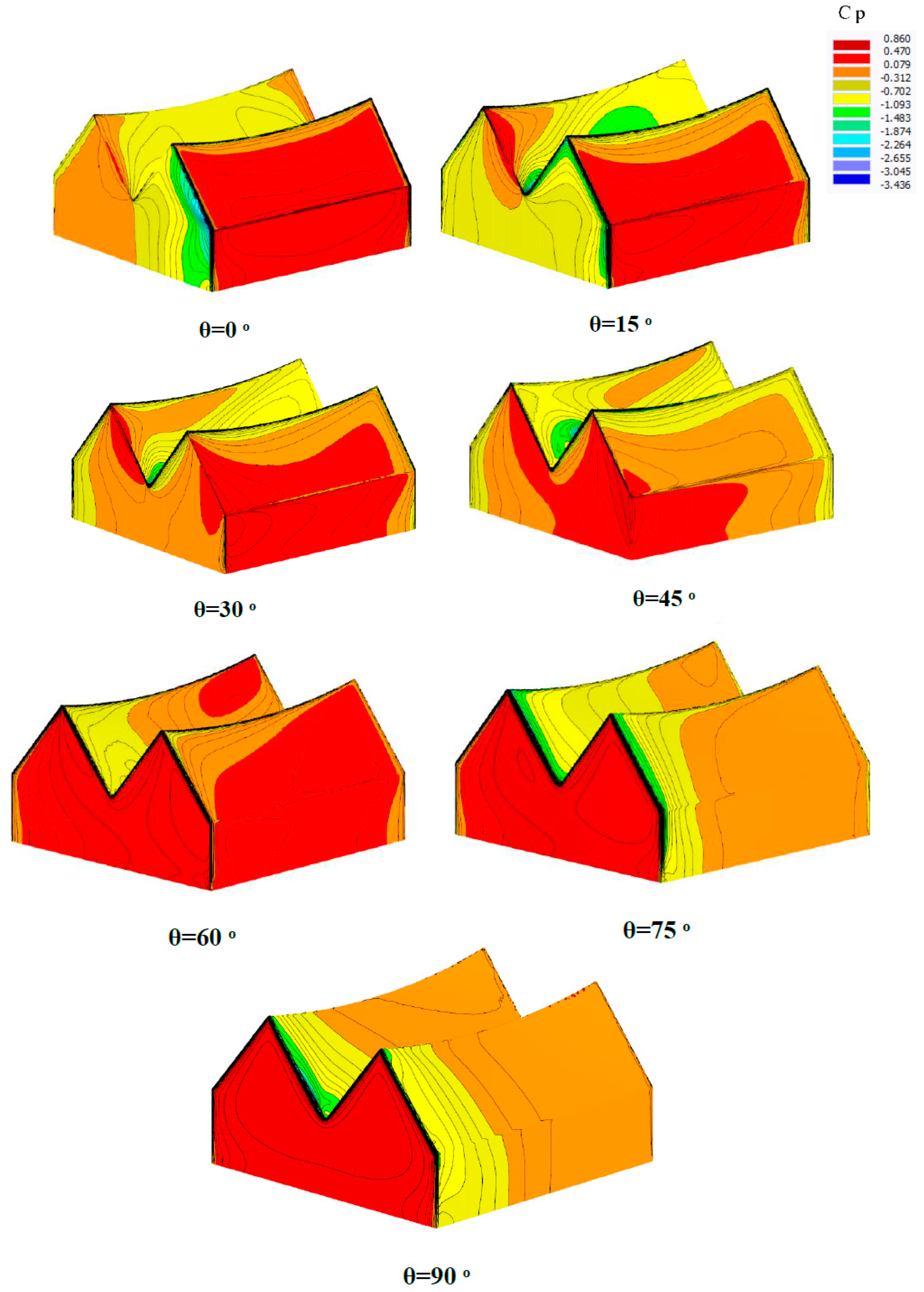

Table 3 describes the effect of wind directions on Drag forces and wind pressure coefficient, it is clear that the variation of projected area for different directions leads to different Drag forces and wind pressure coefficient. Also, Cp-counter is displayed for each direction due to

Figure 13. Based on the unsymmetric form of tensile ridge valley, the results depend on various orientations, so pressure and suction zones are changed for each wind direction.

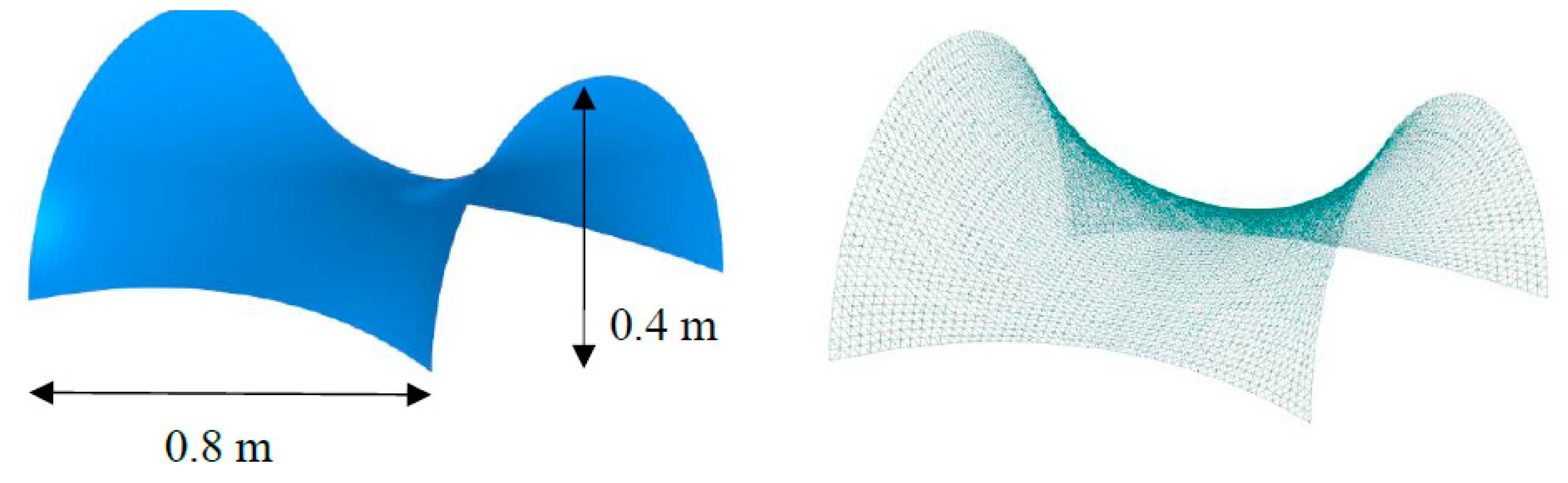

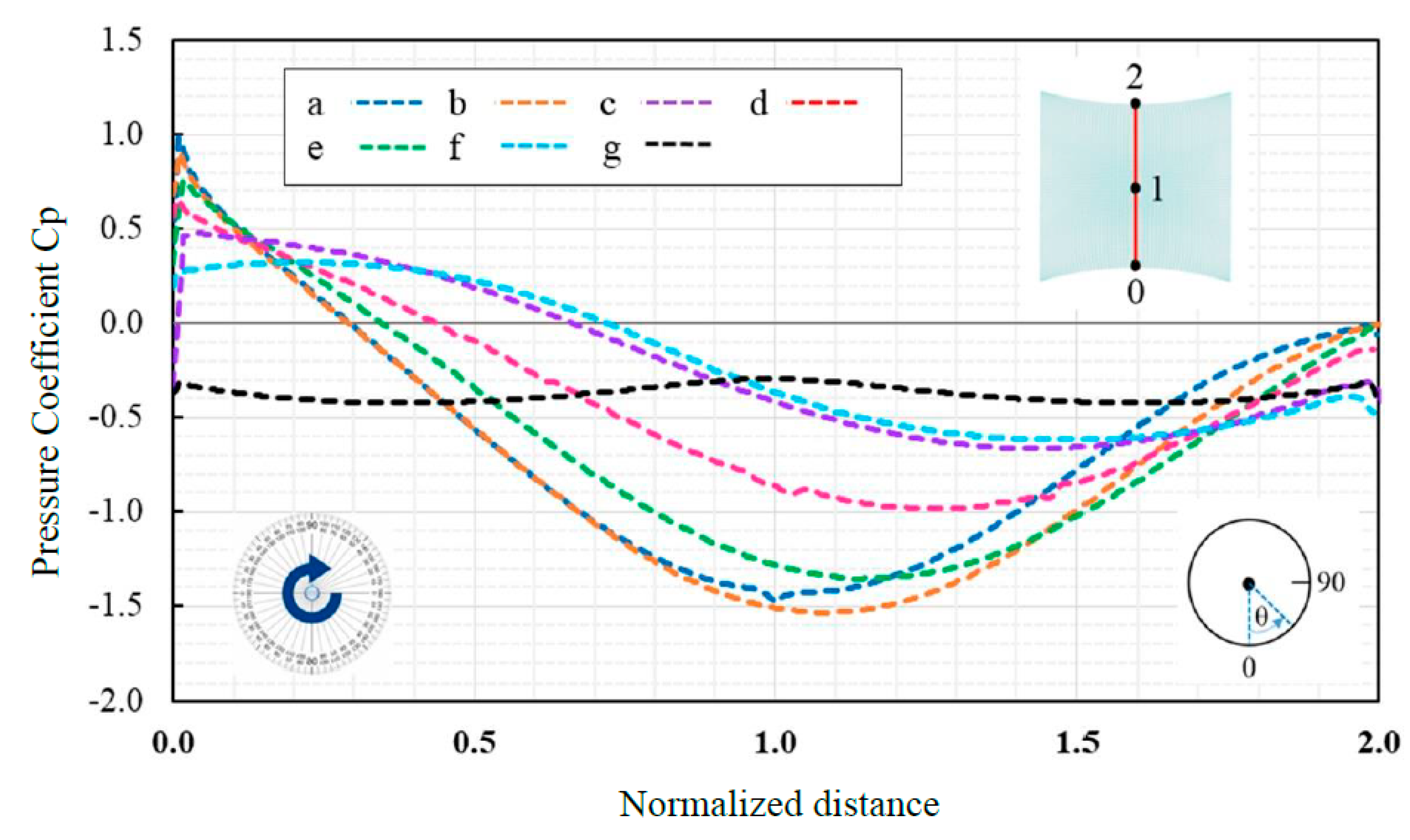

The next shape is the saddle form that is a double-curved surface, the geometry of the saddle is displayed in

Figure 14, the pre-tension surface force is applied equally to 2.5 kN/m in order to perform the standard type of form-finding analysis in RFEM after that final form was transferred to RWIND Simulation for starting wind simulation procedure. The computational mesh became independent in 2,919,277 cells. Several probe lines in horizontal and vertical directions are considered to cover Cp-distribution value on the whole domain for θ=0 (

Figure 15.) and seven directions θ=0,15,30,45,60,75,90

o on center-line (

Figure 16). Based on

Figure 16, for each wind orientation, Cp-variation on the saddle tensile surface is measured on the center-line, it is clear that the Cp-value is positive in the windward face and become gradually negative by moving to the leeward side, also the amount of Cp is decreeing when the wind direction changes from θ=0

o to 90

o. A clear relation between the increments in wind orientation and the shift in the mean Cp-distributions is apparent. The most noticeable wind suction values are obtained at the middle area and reducing towards the downwind area of the roof.

Table 4. shows the drag forces and wind force coefficient for seven wind directions. For each direction based on the value of the projected area that is directly exposed to wind flow, the amount of wind forces, and wind coefficient in x,y,z directions are changing. As a consequence, it is clear that the table illustrates how these parameters are changing through wind directions. For example in θ=75, the value of total drag forces is the maximum case related to all directions

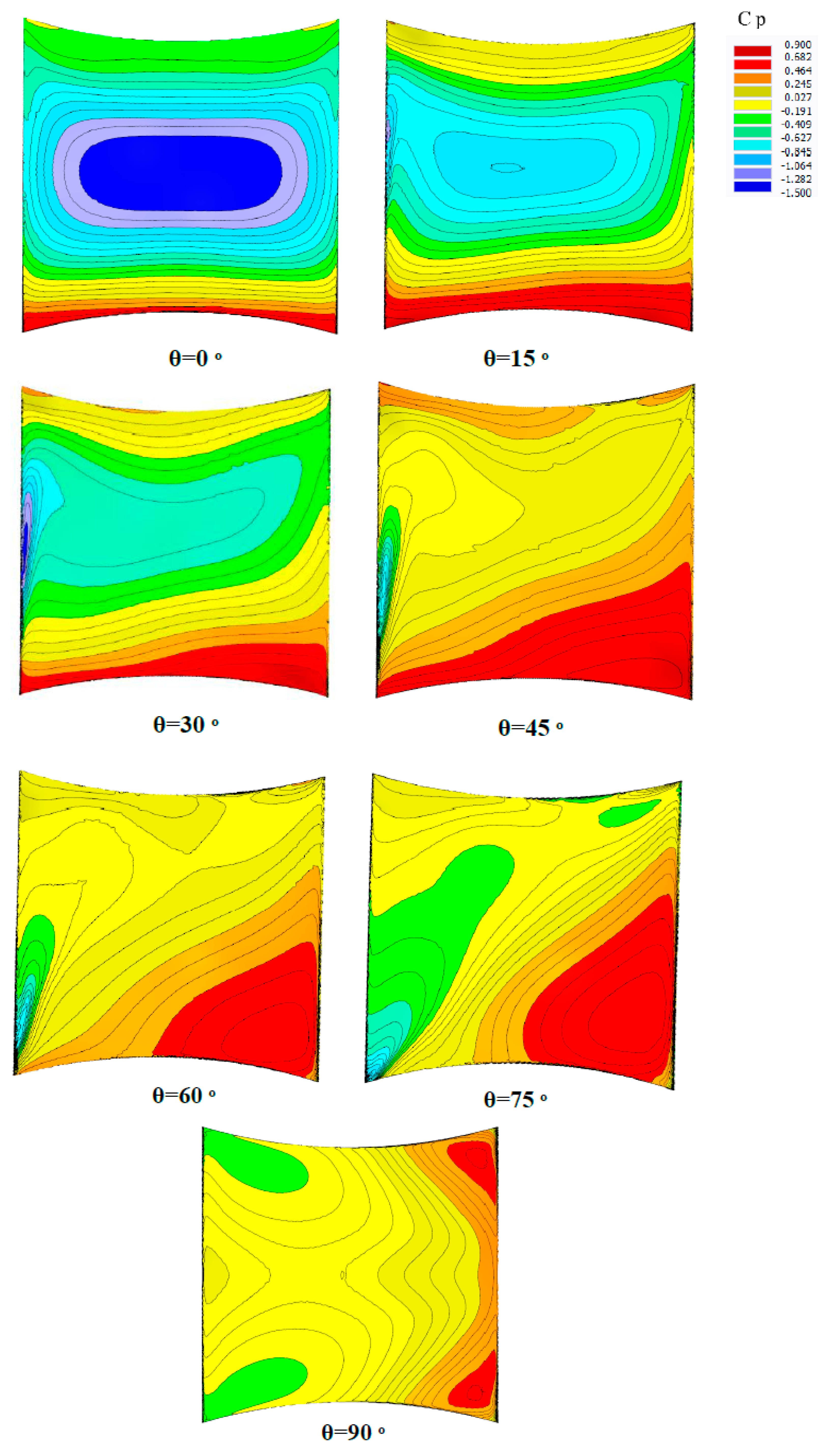

Figure 17, displays how the average Cp contour is changing due to different wind directions, the positive and negative pressure gradually varying on the surface from θ=0

o to 90

o. As can be seen, the positive and negative pressure zones are going to localize in specific areas. The maximum positive and negative pressure zone is moving to the right and left the area while localization has happened. By reducing perpendicular surface due to wind attack, the amount of Cp-distribution starts to decrease.

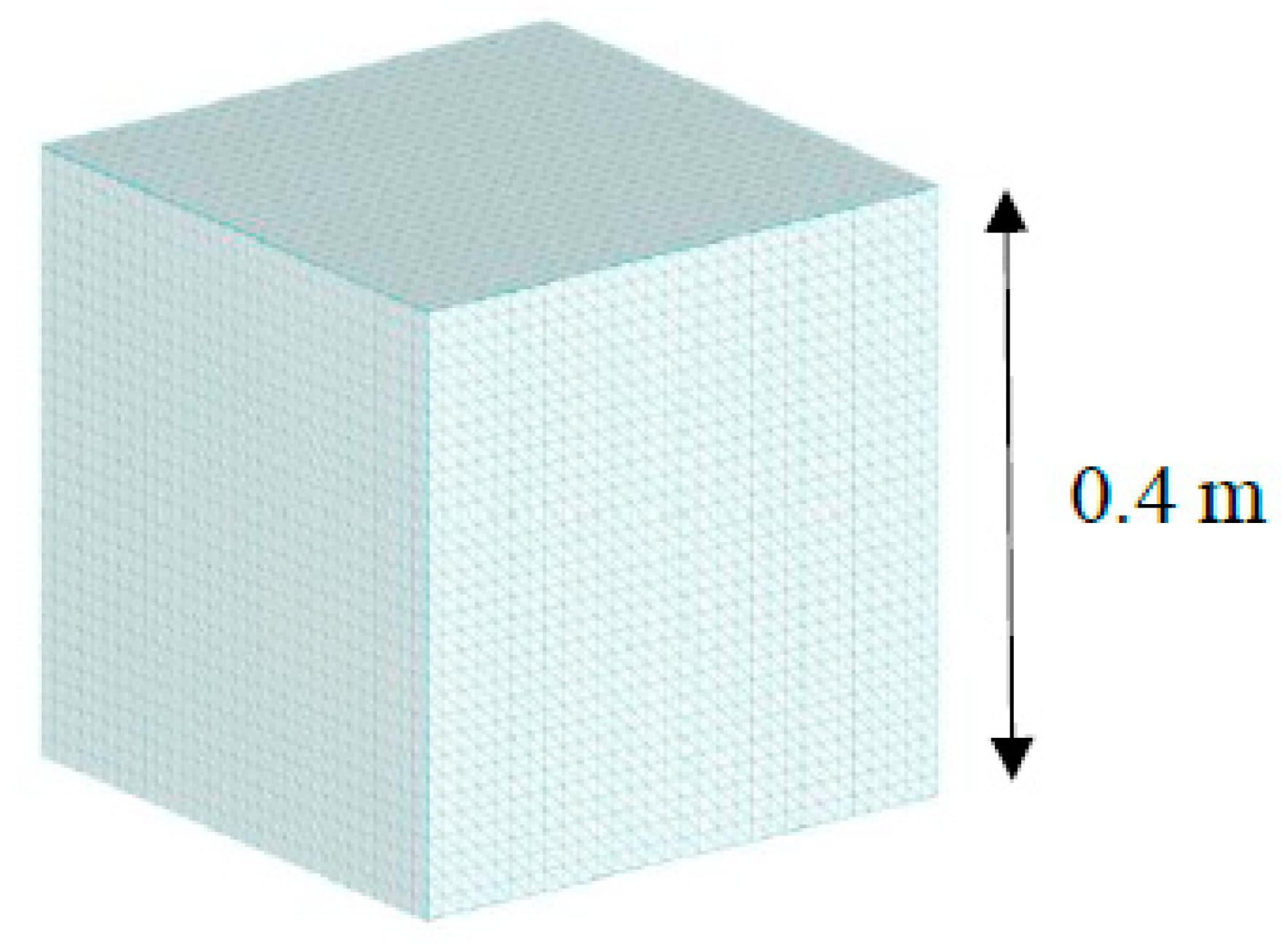

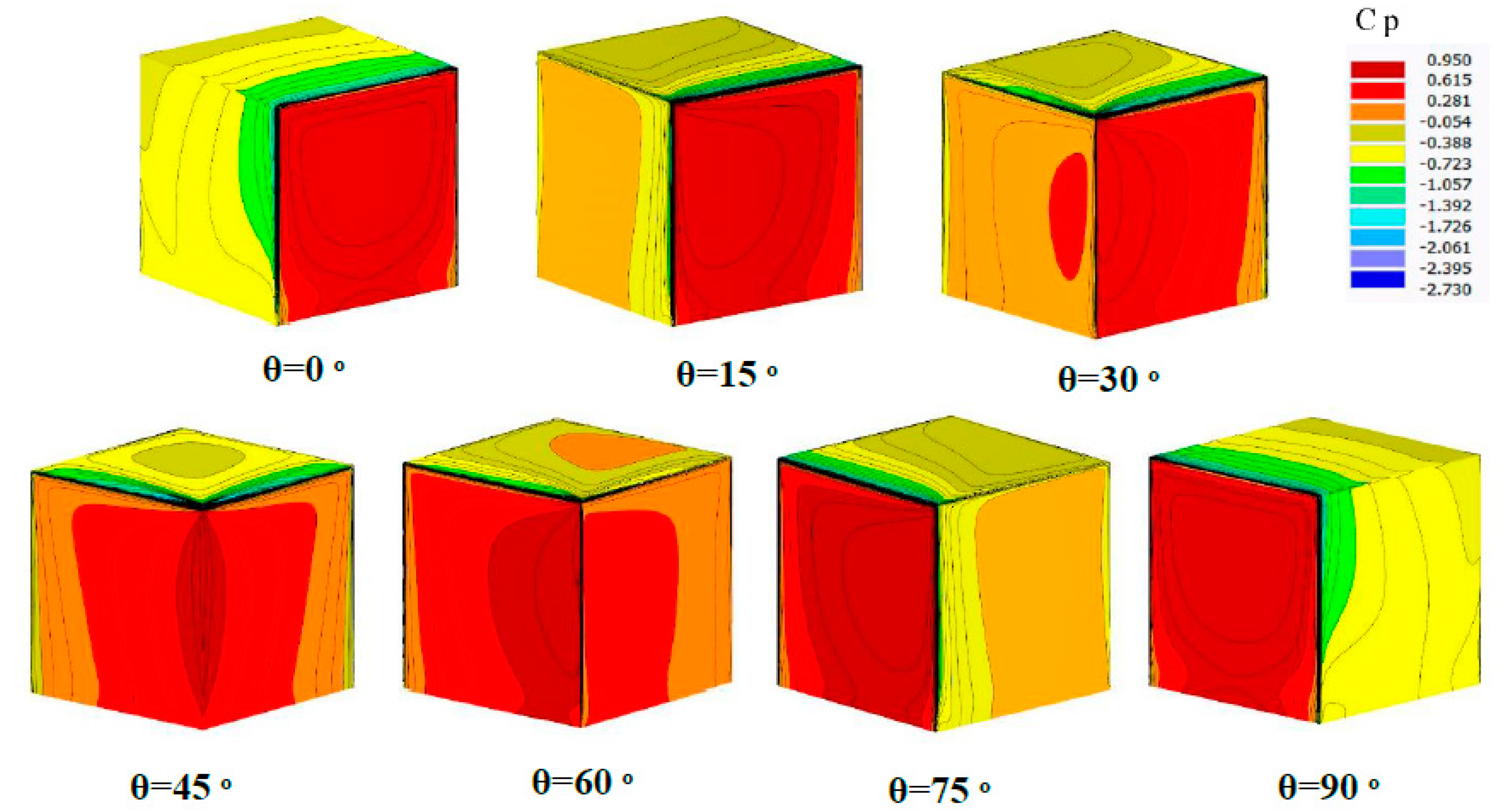

The cube shape is selected as the first shape of general forms, the geometry of the cube is shown in

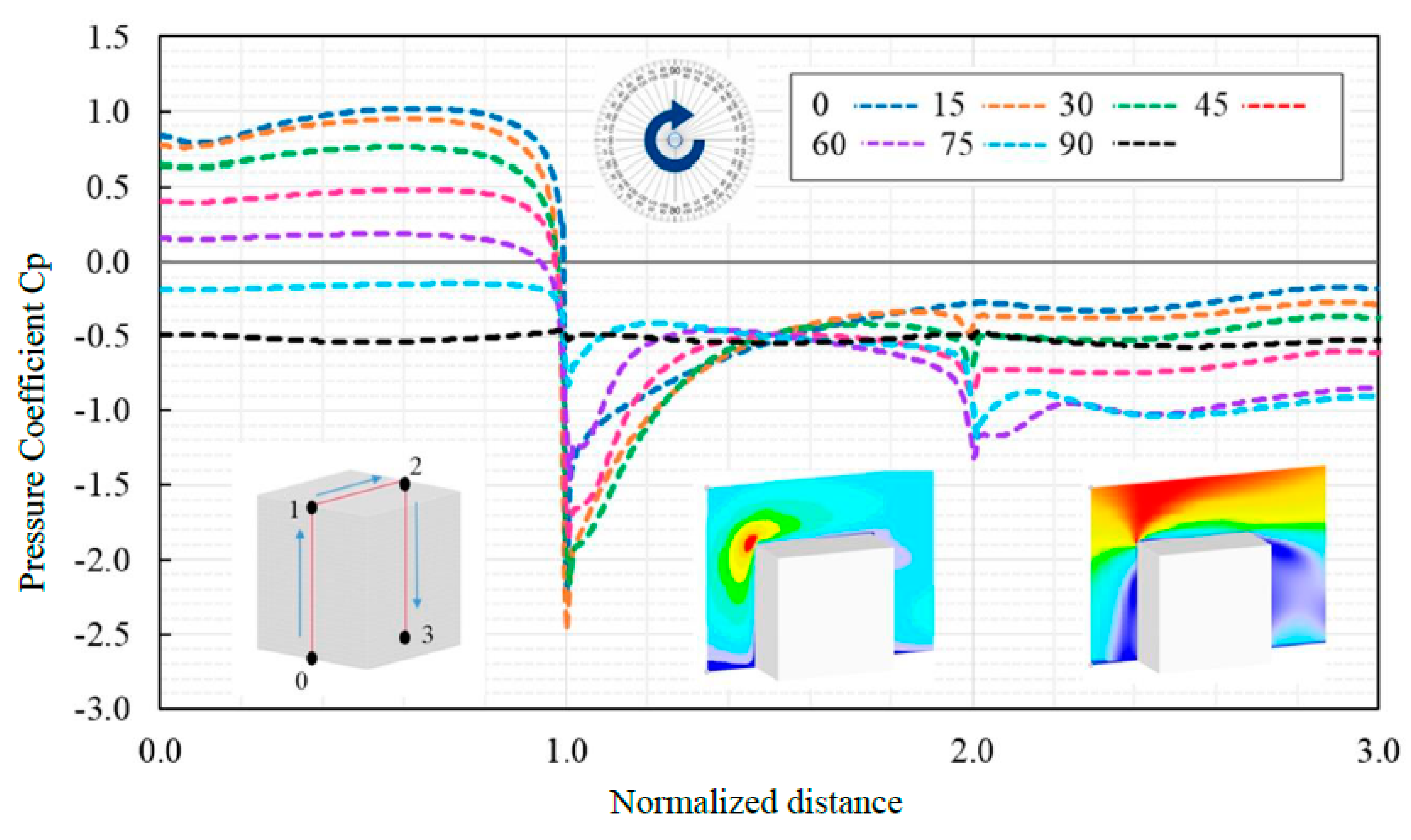

Figure 18. The computational mesh became independent in 2,447,998 cells. Cp-value is calculated on the normalized center-line for different wind directions θ=0,15,30,45,60,75,90 (

Figure 19.), because it is an unsymmetrical structural form due to wind directions. The upper and lower Cp-value is changing between +1 to -2.5.

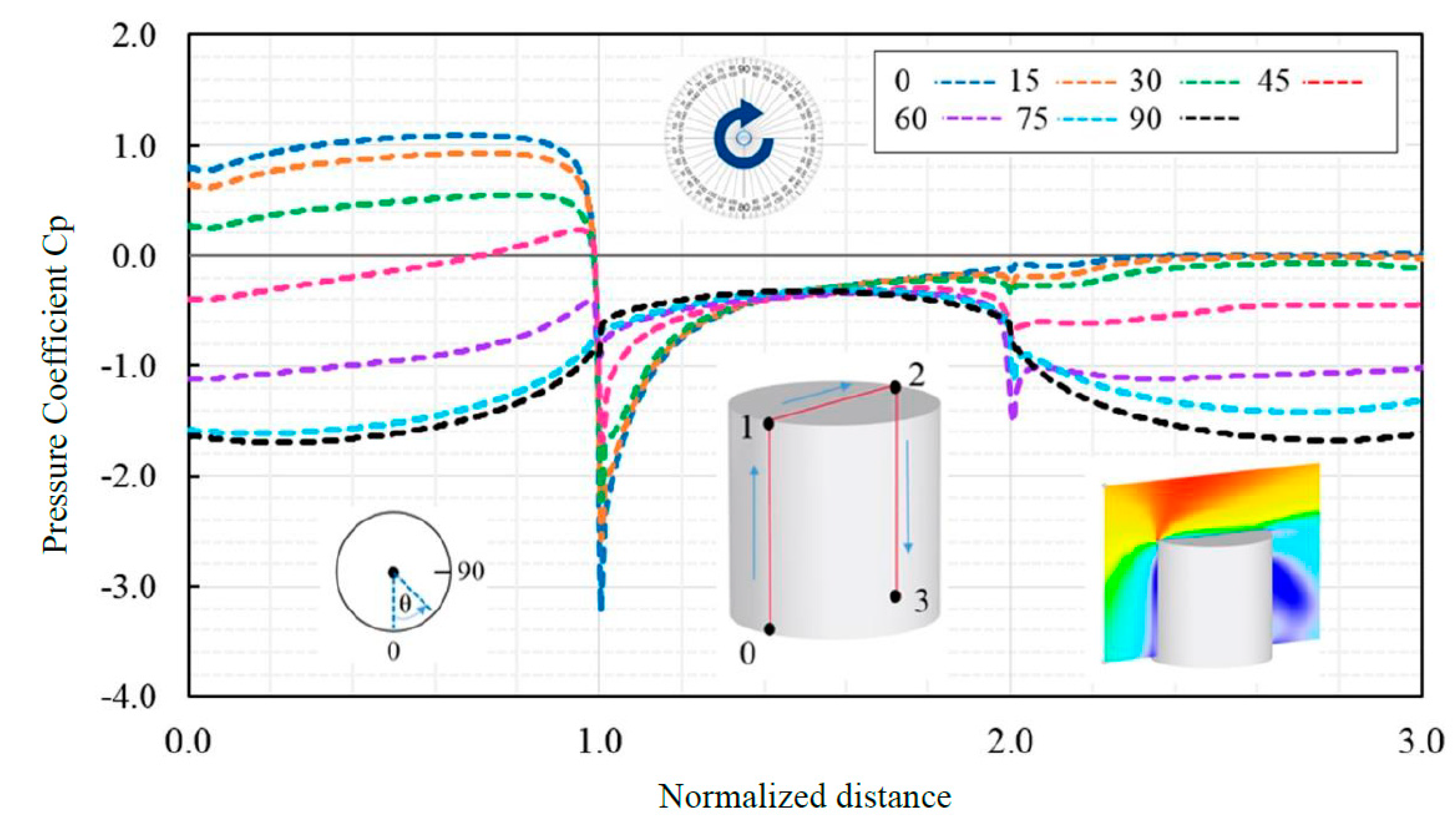

As it can be seen in

Figure 19 and

Figure 20, by increasing wind direction from θ=0 to 90, the positive and negative Cp-value is changing, the main reason comes back to change in perpendicular angle of wind attack. A clear relation between the increments in wind orientation and the shift in the mean Cp-distributions is obvious in

Figure 20. The most noticeable wind suction values are obtained at top windward edges and reducing towards the downwind area of the cube shape. In other words, the positive wind pressure happened in the orthogonal position of the surface. Compared to the other directions, the maximum suction values happened at the upwind-edge and start to decrease less at the downwind zones. The amount of wind drag forces is illustrated in

Table 5, the most drag forces happened on θ=45, which shows that in this angle, the largest amount of wind pressure is absorbed based on the projected surface.

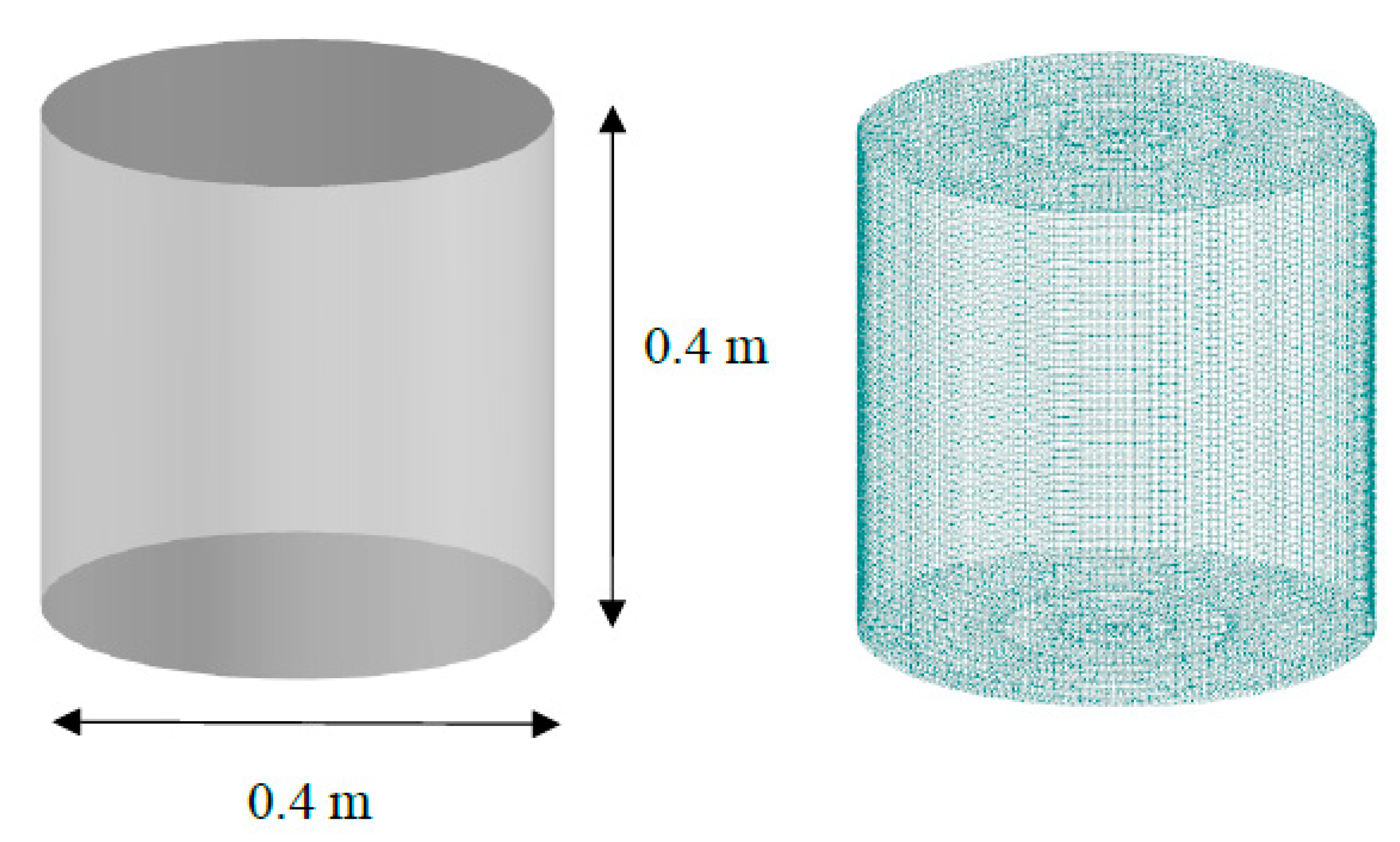

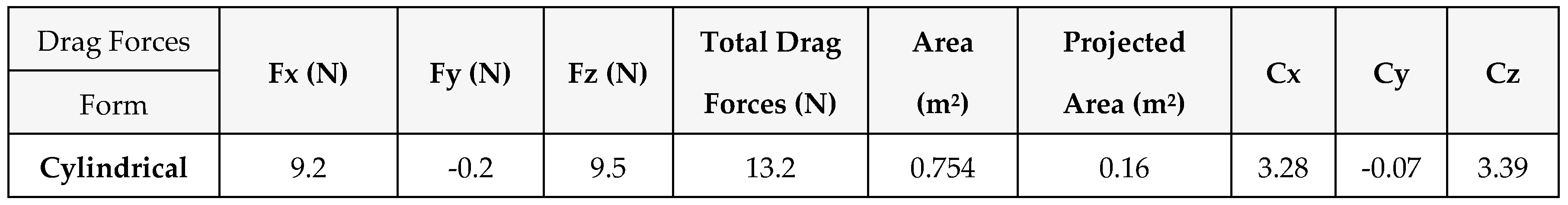

The cylindrical shape is investigated as the next form, the surface geometry is displayed in

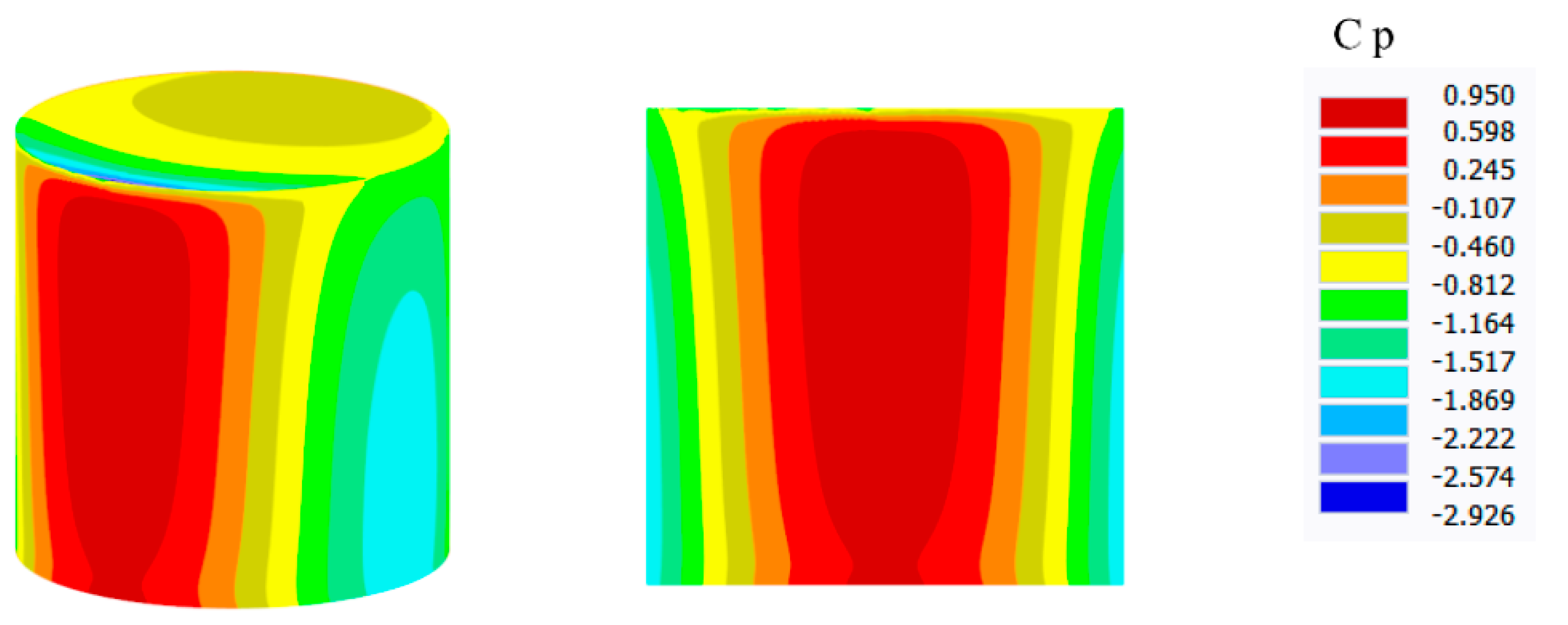

Figure 21. The model is created in RFEM, then export to RWIND simulation for airflow analysis. Because of the symmetric form of the cylinder, the value of Cp is independent of wind direction. The computational mesh became independent in 2,305,232 cells.

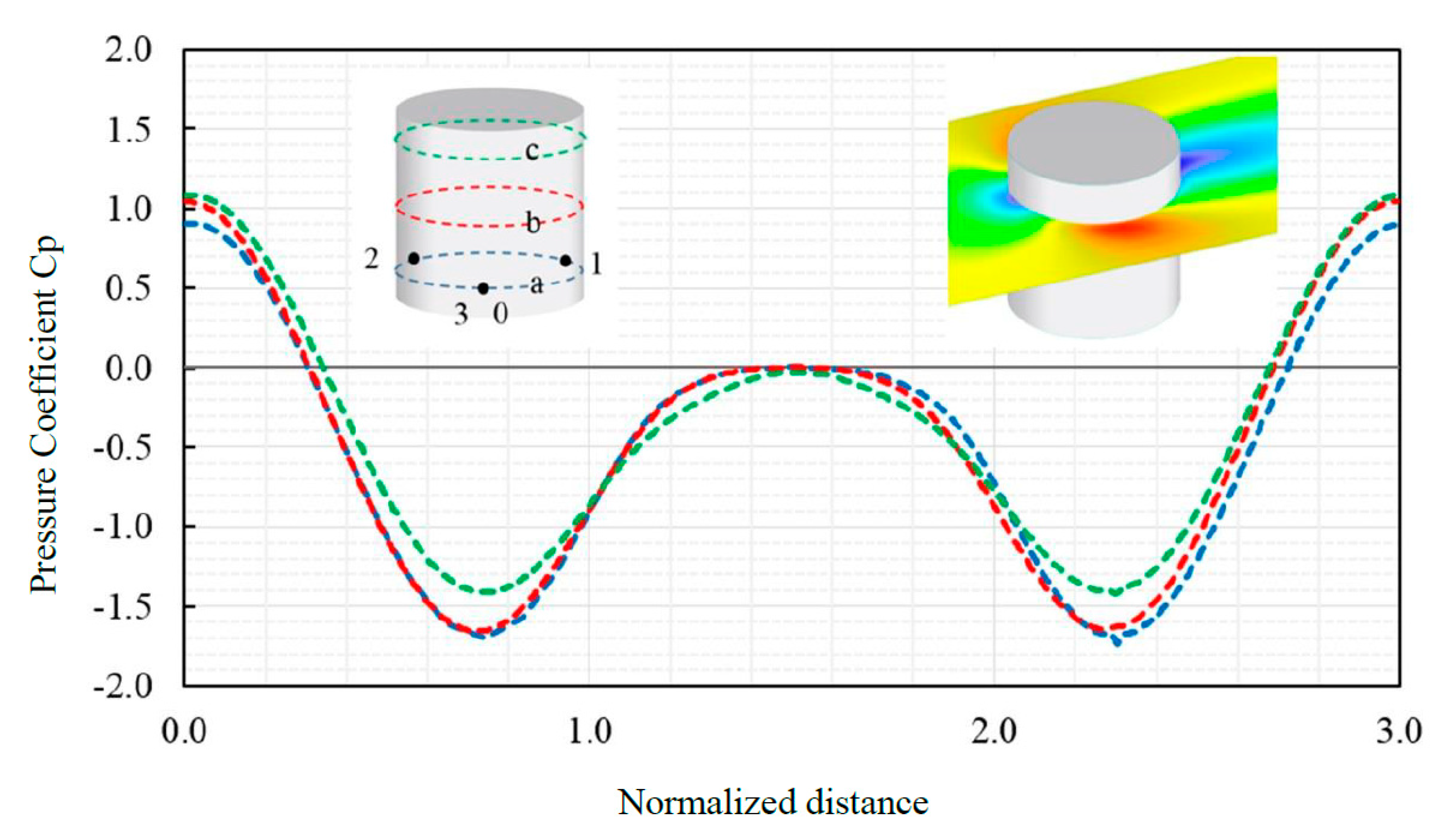

The average Cp contour is demonstrated in

Figure 22 for a single wind attack, also Cp-distribution is calculated for seven probe lines from θ=0

o to 90

o in vertical directions (

Figure 23.), so the upper and lower value is observed through normalized distance. There is an obvious relation between the increments in wind orientation and the shift in the mean Cp-distributions is clear. The most noticeable wind suction values are obtained at windward edges and reducing towards the downwind area of the cylindrical shape. For 3 horizontal probe lines, the Cp-variation is plotted as well due to

Figure 24. In

Table 6, Drag forces and wind force coefficient is shown respectively.

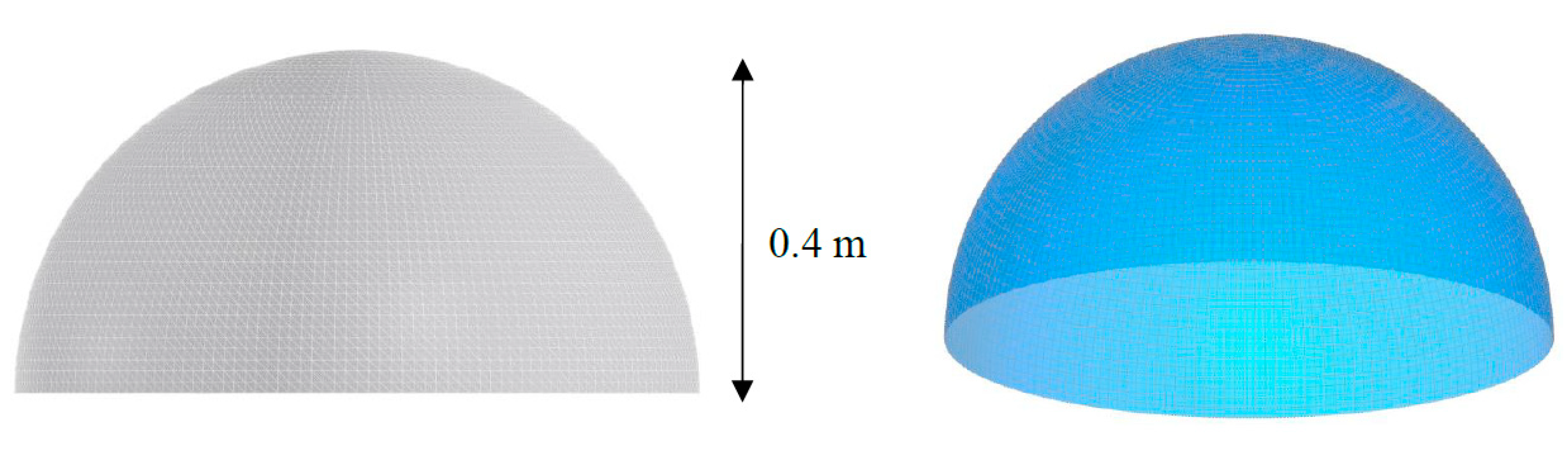

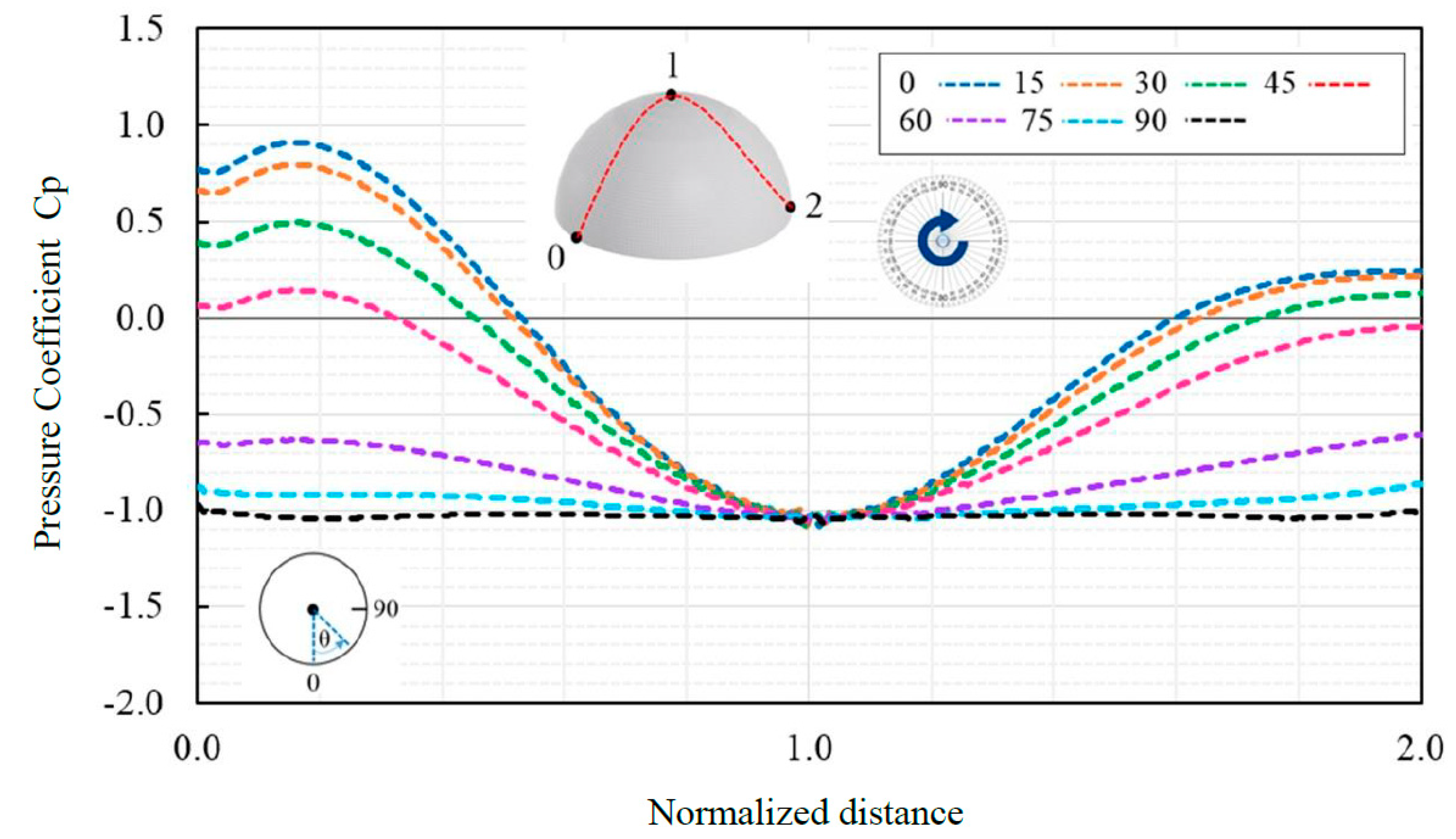

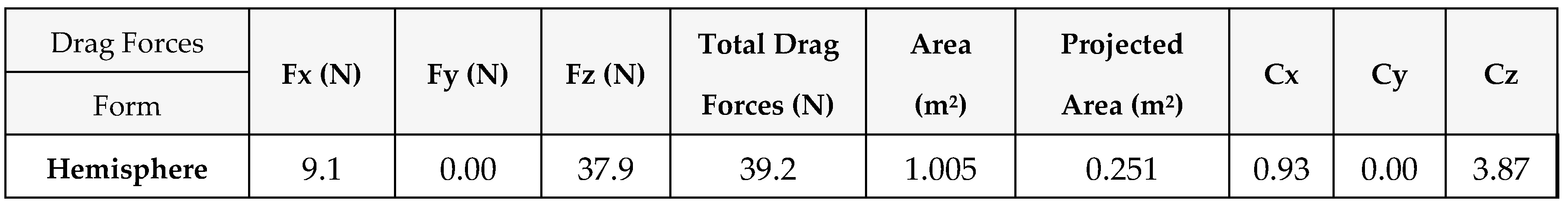

As another symmetrical form, a hemisphere shape is selected as an independent shape of wind direction. The geometry of the hemisphere is shown in

Figure 25. The computational mesh became independent in 3,202,462 cells. Due to seven vertical probe lines, Cp-variation is plotted on the surface (

Figure 26.), so the upper and lower value of Cp from positive to negative can be observed clearly. The maximum suction values become happened at the top middle point while for the downwind zones, and in other area the suction value is decreasing. Similarly, the variation of mean wind pressure Cp is investigated for horizontal line probes that changed approximately periodically from positive to negative value through normalized distance (

Figure 27).

Therefore, as the probe line gets distance from the center point of the hemisphere, the amount of Cp is going to decrease. The Cp contour for hemisphere in

Figure 28 shows pressure and suction zone obviously. Finally, in

Table 7, the amount of drag forces and wind coefficients are calculated for all global directions using a single simulation as well.

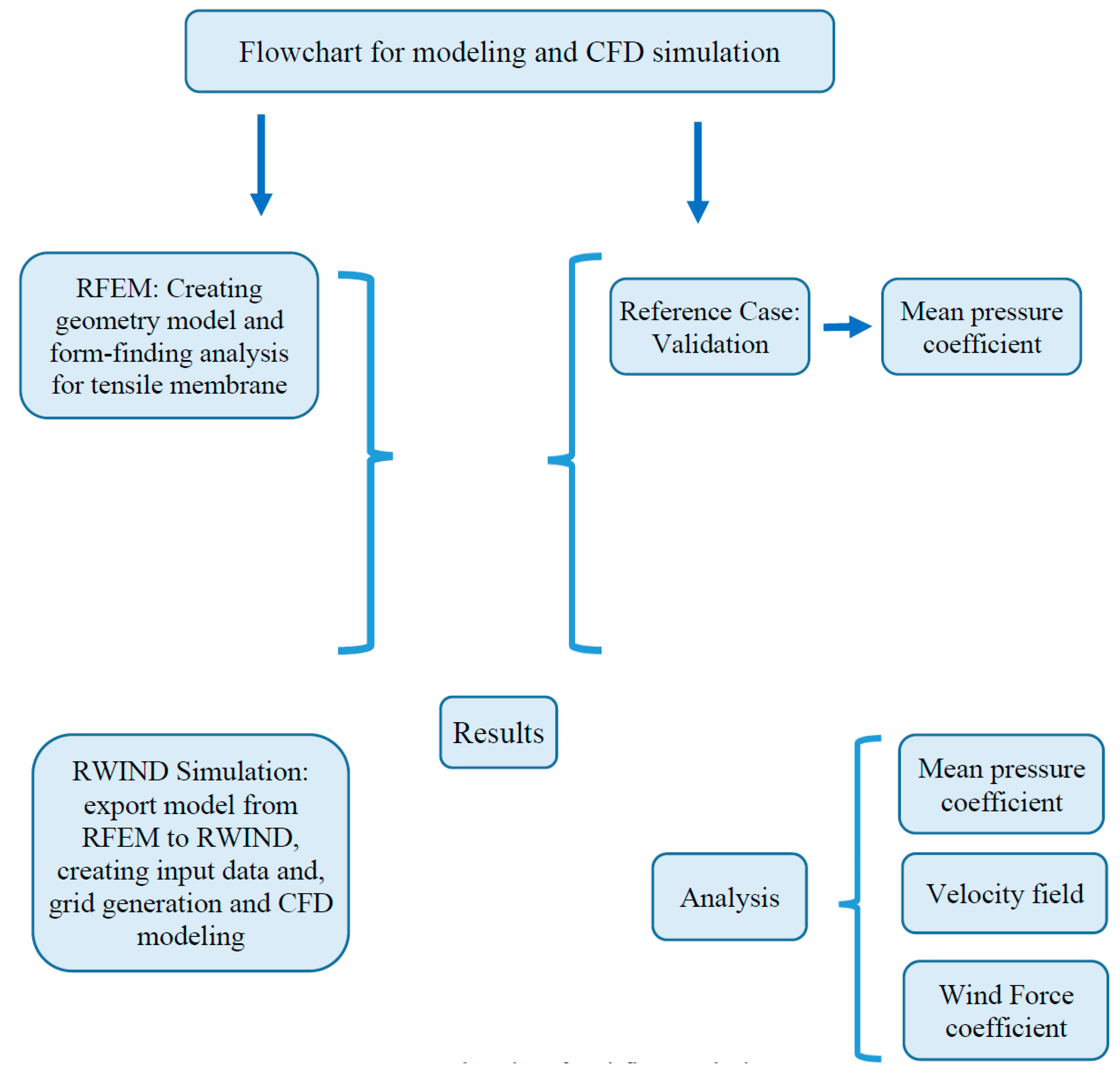

Figure 1.

Flowchart for airflow analysis.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for airflow analysis.

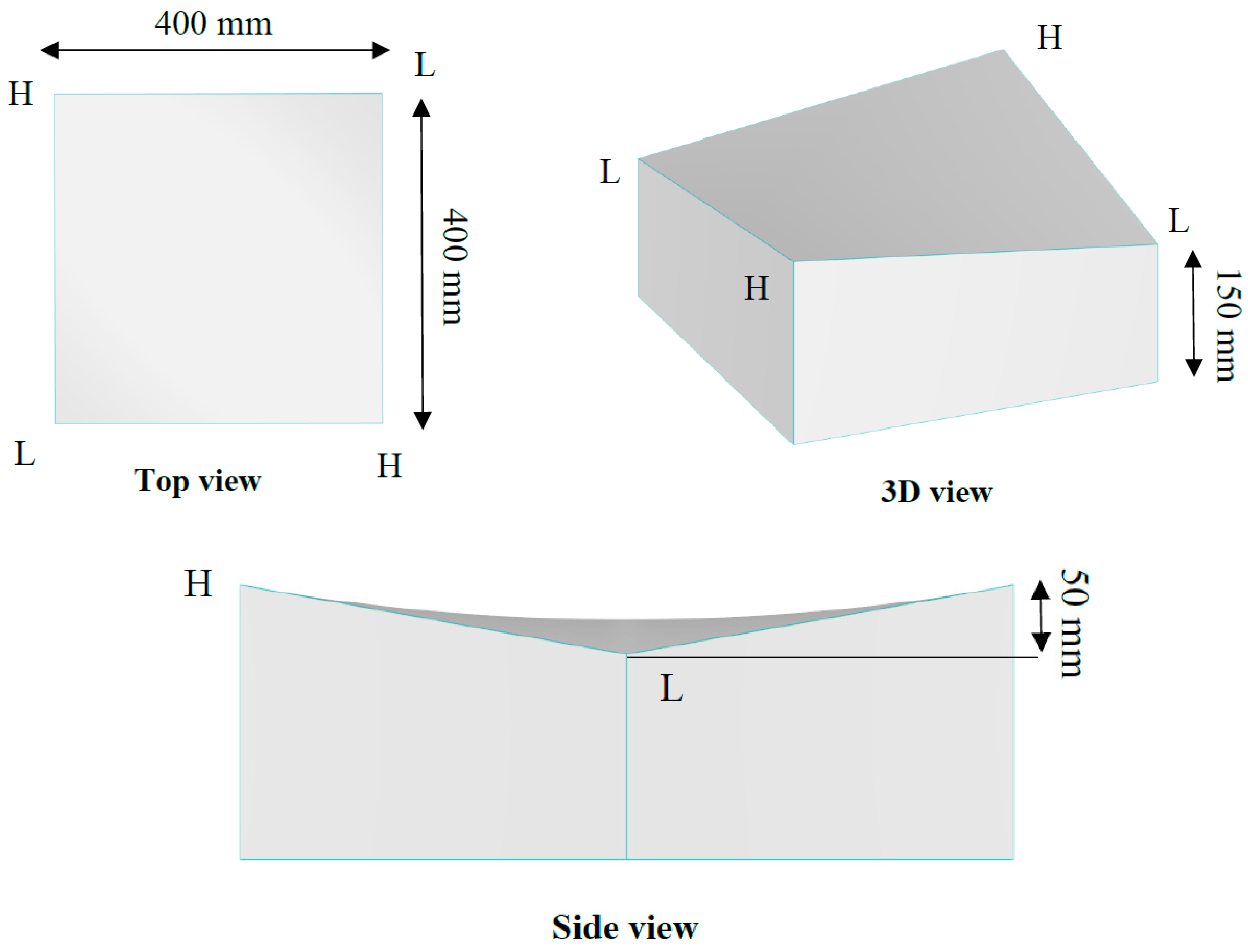

Figure 2.

Dimention of the slightly curved hypar roof.

Figure 2.

Dimention of the slightly curved hypar roof.

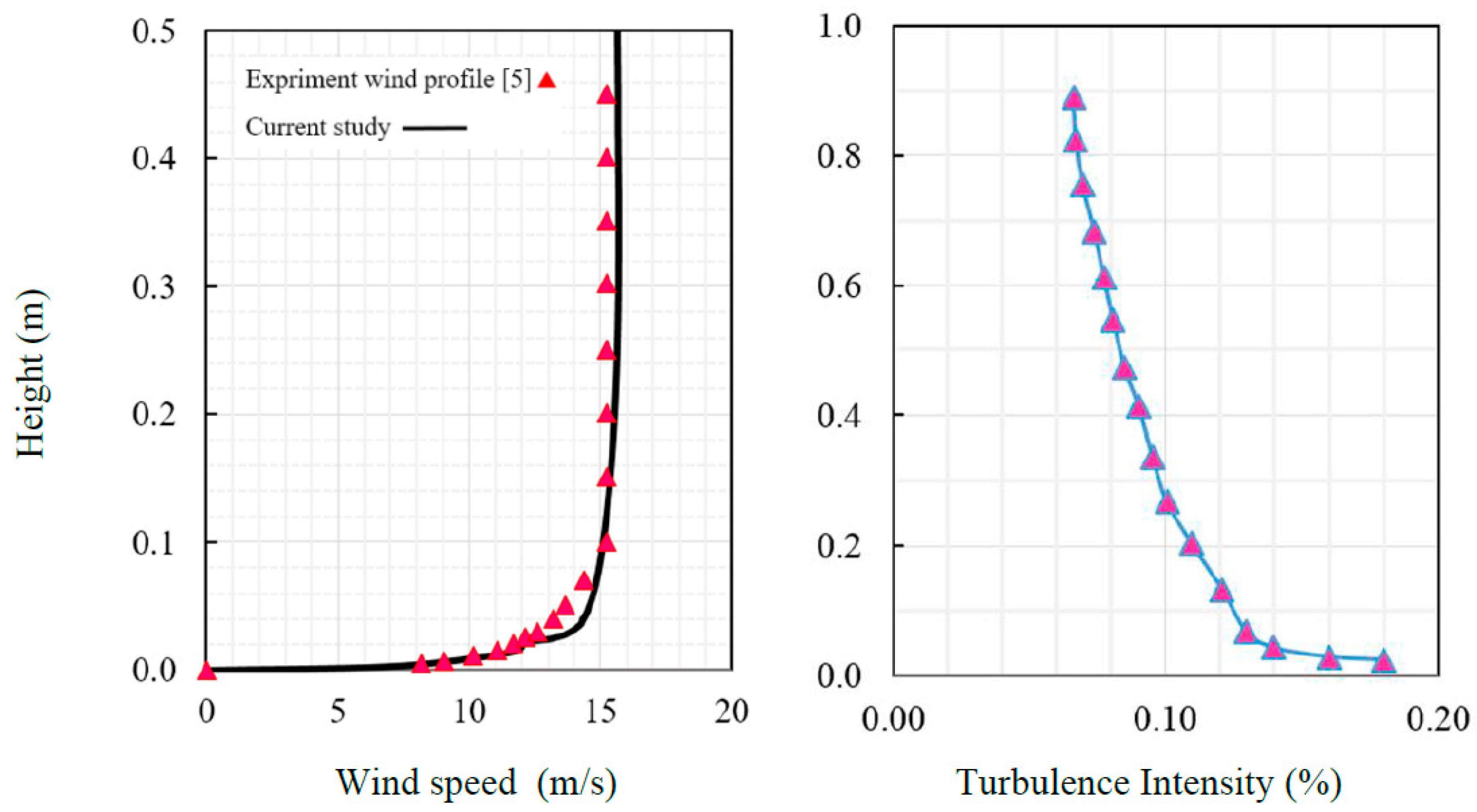

Figure 3.

Profile of wind speed and turbulence intensity due to height.

Figure 3.

Profile of wind speed and turbulence intensity due to height.

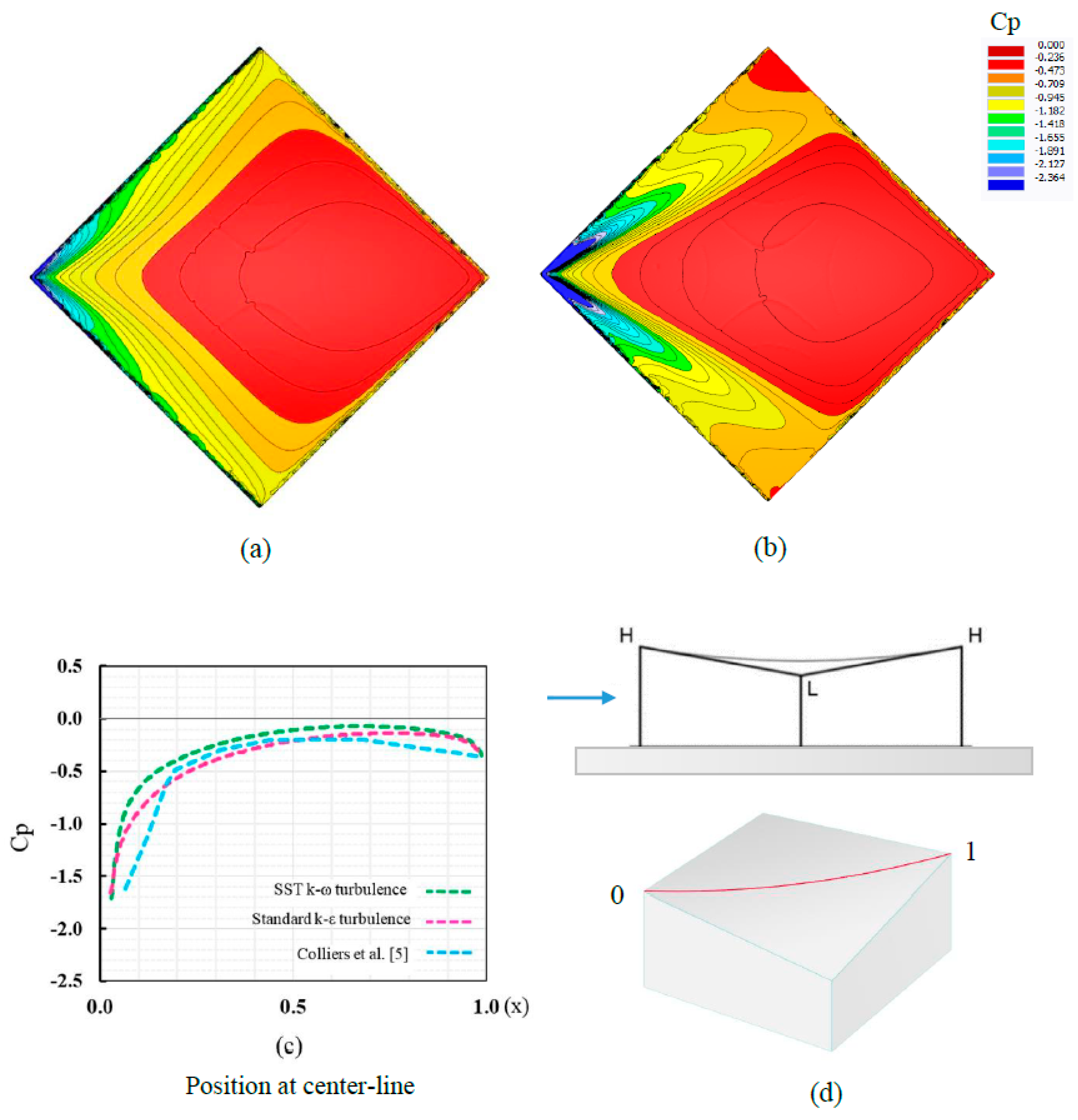

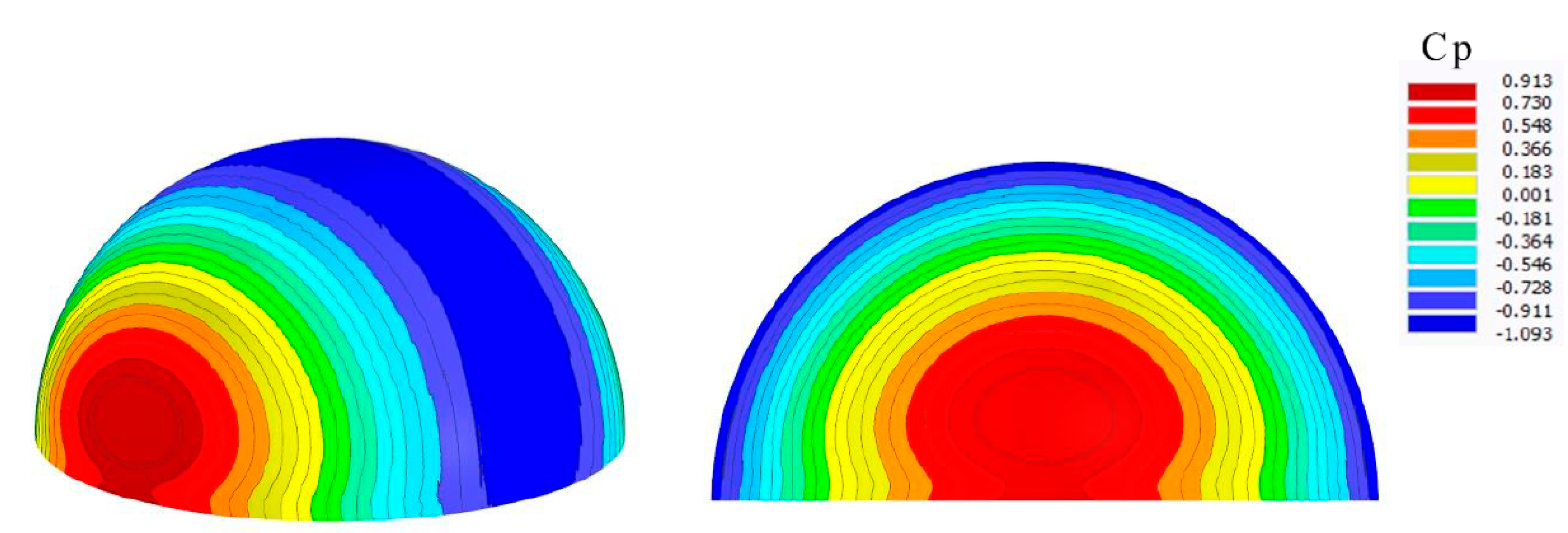

Figure 5.

Mean wind pressure coefficient (Cp,e) over the slightly curved hypar roof (a). Standard k-ε turbulence model (b). SST k-ω turbulence model (c). comparison of mean Cp,e value at the centerline (d). normalized line on the hypar roof.

Figure 5.

Mean wind pressure coefficient (Cp,e) over the slightly curved hypar roof (a). Standard k-ε turbulence model (b). SST k-ω turbulence model (c). comparison of mean Cp,e value at the centerline (d). normalized line on the hypar roof.

Figure 6.

Grid independency of Cp-distribution for three numbers of elements.

Figure 6.

Grid independency of Cp-distribution for three numbers of elements.

Figure 7.

Conical geometry form in RFEM and FE mesh information.

Figure 7.

Conical geometry form in RFEM and FE mesh information.

Figure 8.

Average of wind pressure distribution on vertical probe lines for conical form.

Figure 8.

Average of wind pressure distribution on vertical probe lines for conical form.

Figure 9.

Average Cp contour for conical form.

Figure 9.

Average Cp contour for conical form.

Figure 10.

Average of wind pressure distribution on horizental probe lines for conical form.

Figure 10.

Average of wind pressure distribution on horizental probe lines for conical form.

Figure 11.

Tensile ridge-valley form in RFEM and FE mesh information.

Figure 11.

Tensile ridge-valley form in RFEM and FE mesh information.

Figure 12.

Average of Cp-distribution on vertical probe lines for tensile ridge-valley.

Figure 12.

Average of Cp-distribution on vertical probe lines for tensile ridge-valley.

Figure 13.

Average Cp contour for tensile ridge-valley surface.

Figure 13.

Average Cp contour for tensile ridge-valley surface.

Figure 14.

Saddle geometry information in RFEM and FE mesh data.

Figure 14.

Saddle geometry information in RFEM and FE mesh data.

Figure 15.

Average wind pressure distribution on vertical probe lines for saddle shape on θ=0o.

Figure 15.

Average wind pressure distribution on vertical probe lines for saddle shape on θ=0o.

Figure 16.

Average of wind pressure distribution on probe lines for saddle shape.

Figure 16.

Average of wind pressure distribution on probe lines for saddle shape.

Figure 17.

Average of Cp countour for tensile saddle through 7 wind directions.

Figure 17.

Average of Cp countour for tensile saddle through 7 wind directions.

Figure 18.

Cube shape geometry.

Figure 18.

Cube shape geometry.

Figure 19.

Average of wind pressure distribution on vertical probe lines for cube shape.

Figure 19.

Average of wind pressure distribution on vertical probe lines for cube shape.

Figure 20.

Average of Cp-distribution for cube form through 7 wind directions.

Figure 20.

Average of Cp-distribution for cube form through 7 wind directions.

Figure 21.

Cylindrical geometry in RFEM and FE mesh information.

Figure 21.

Cylindrical geometry in RFEM and FE mesh information.

Figure 22.

Average of Cp- distribution for cylindrical form through 7 wind directions.

Figure 22.

Average of Cp- distribution for cylindrical form through 7 wind directions.

Figure 23.

Average of wind pressure distribution on vertical probe lines for cylindrical shape.

Figure 23.

Average of wind pressure distribution on vertical probe lines for cylindrical shape.

Figure 24.

Average of wind pressure distribution on horizontal probe lines for the cylindrical shape.

Figure 24.

Average of wind pressure distribution on horizontal probe lines for the cylindrical shape.

Figure 25.

Hemisphere geometry information in RFEM and FE mesh data.

Figure 25.

Hemisphere geometry information in RFEM and FE mesh data.

Figure 26.

Average of wind pressure distribution on vertical probe lines for hemisphere shape.

Figure 26.

Average of wind pressure distribution on vertical probe lines for hemisphere shape.

Figure 27.

Average of average wind pressure distribution on horizontal probe lines for hemisphere shape.

Figure 27.

Average of average wind pressure distribution on horizontal probe lines for hemisphere shape.

Figure 28.

Average Cp contour for hemisphere form.

Figure 28.

Average Cp contour for hemisphere form.

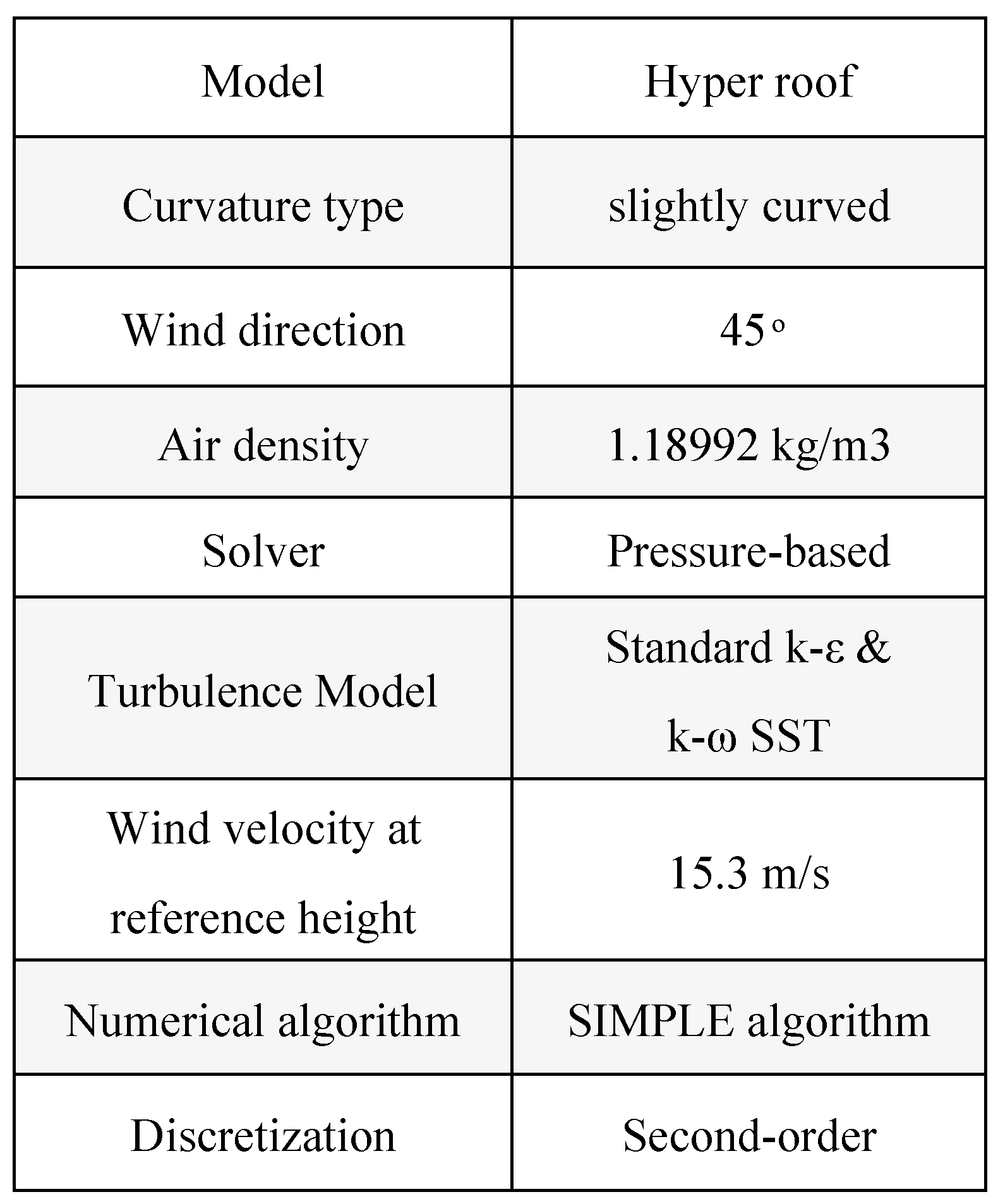

Table 1.

Model specifications.

Table 1.

Model specifications.

Table 2.

Drag forces and wind coefficient for conical form.

Table 2.

Drag forces and wind coefficient for conical form.

Table 3.

Drag forces and wind coefficient for tensile ridge valley form.

Table 3.

Drag forces and wind coefficient for tensile ridge valley form.

Table 4.

Drag forces and wind coefficient for Saddle form.

Table 4.

Drag forces and wind coefficient for Saddle form.

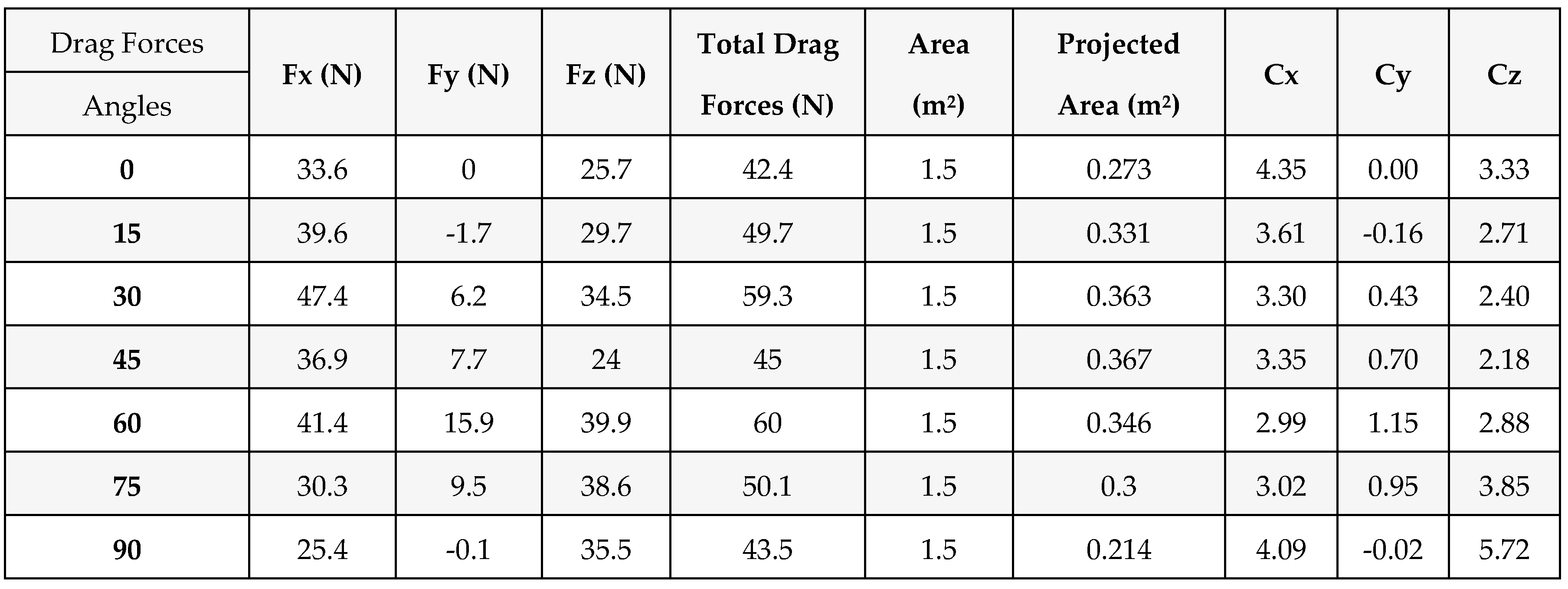

Table 5.

Drag forces and wind coefficient for cube form.

Table 5.

Drag forces and wind coefficient for cube form.

Table 6.

Drag forces and wind coefficient for the cylindrical shape.

Table 6.

Drag forces and wind coefficient for the cylindrical shape.

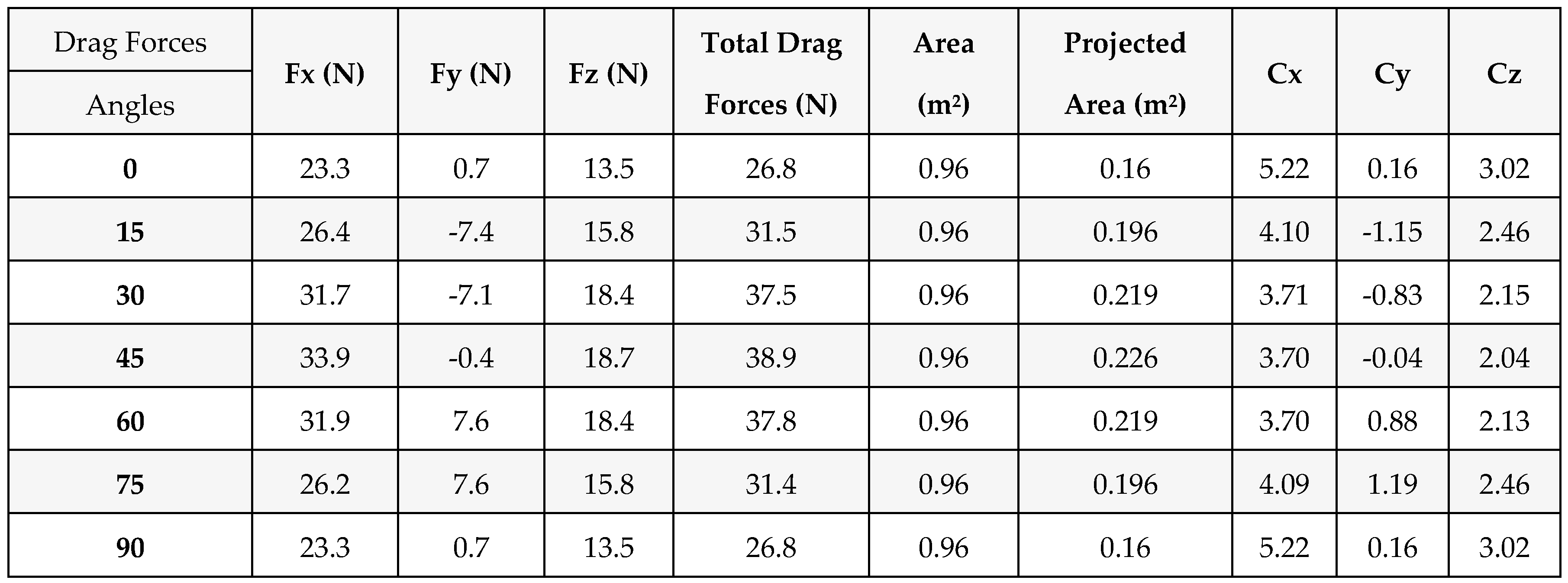

Table 7.

Drag forces and wind coefficient for Hemisphere form.

Table 7.

Drag forces and wind coefficient for Hemisphere form.