1. Introduction

Suicidal behavior among children and adolescents is a critical public health concern with severe societal consequences. Despite showing a promising decreasing trend, suicides consistently rank among the leading causes of death for adolescents in Europe and the United States [

1,

2,

3,

4]. A common misconception persists that children are incapable of contemplating suicide due to their developmental stage. However, research demonstrates that even school-age children under twelve years of age can experience suicidal thoughts and behaviors [

3,

5]. These starting points predispose suicidality to be one of the main points of interest for child and adolescent psychiatrists today.

Suicidal behavior is not attributable to a single cause but rather arises through the dynamic interaction of multiple risk determinants, encompassing biological, psychological, social, and environmental conditions [

6]. While the influence of psychosocial stressors is widely acknowledged, a more profound comprehension of the underlying biological mechanisms is crucial for the development of truly effective prevention and intervention strategies [

7].

This review synthesizes current evidence on biological risk factors for suicidality in children and adolescents, with a focus on neurobiological mechanisms, genetic and epigenetic influences, and peripheral biomarkers. The findings aim to highlight knowledge gaps and potential opportunities for prevention and intervention.

2. Suicidality in Slovakia, Age, and the Gender Paradox

In Slovakia, the National Health Information Centre (NCZI) has been monitoring multiple parameters concerning suicidality and suicidal acts since 2008. Girls aged 0–14 consistently exhibited very low numbers of both completed suicides and suicide attempts until the year 2017, when the number of attempts in this group started rising and surpassing older age groups. The rate peaked in 2022 at 17.4 per 100,000, the second-highest among female cohorts, before falling back to 8.1 in 2024, the second-lowest among female cohorts. The number of completed suicides in girls aged 0-14 years old is consistently low. Adolescent females aged 15–19 follow a different trajectory. Since 2013, they have persistently shown the highest attempt rates of any group, with peaks in 2017 (48.7 per 100,000) and 2022 (89.9 per 100,000). While completed suicides remain relatively uncommon, mortality rose sharply in some years, reaching 5.5 per 100,000 in 2021 before dropping to 0.8 in 2024 [

8].

International evidence suggests that these Slovak patterns are not isolated and may reflect broader global trends associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. In Catalonia, Spain, a population-based registry recorded a 25% overall increase in adolescent suicide attempts during the first pandemic year. Still, the rise was driven almost entirely by girls. Their rates climbed from 99.2 to 146.8 per 100,000, with a dramatic 195% surge at the start of the 2020–2021 school year compared to the previous six months, while boys’ rates remained stable [

9]. Similar patterns emerged in the United States, where emergency visits for suspected suicide attempts among adolescent girls were 51% higher in early 2021 compared with the same period in 2019, in contrast to only minimal change among boys [

10]. Global analyses likewise point to sustained increases in female youth suicide mortality in several countries (including the United Kingdom, South Korea, and Japan) during the years preceding and overlapping with the pandemic [

2].

The stable pattern in male suicidality observed internationally is also evident in Slovakia, where boys and men follow a steady trajectory across age groups. Boys aged 0–14 and adolescent males aged 15–19 maintain relatively low suicide rates compared with older men. For example, the suicide rate among adolescents aged 15–19 was 9.3 per 100,000 in 2017 and 7.1 in 2024. These rates still far surpass those observed in their female counterparts. With age, male suicide mortality rises steeply, peaking in men aged 70 and older, where rates consistently exceed 30 per 100,000. This pattern suggests that older men are at a substantially higher risk of suicide, with rates far surpassing those seen in any female age group. In contrast, attempts are less common among males of all ages. Even in adolescent boys, the highest attempt rate observed since 2008 was 31.3 per 100,000 in 2012, declining to 20.7 in 2024 [

8].

The data [

8] underscores a gendered dimension to suicide risk, where adolescent girls are more prone to attempts, while older men are more likely to die by suicide. This is consistent with a pattern of gender paradox regardless of age observed across Europe and globally [

11,

12,

13,

14].

According to a 2025 study, suicide-related mortality in Europe declined between 2012 and 2021. The age-adjusted mortality rate dropped from 12.3 to 10.2 per 100,000, with a more pronounced decrease among men and individuals under 65 years. However, disparities persist across EU subregions, with Eastern Europe (including Slovakia) generally showing higher rates than Western Europe [

15]. Globally, suicide mortality rates vary widely. A 2024 study analyzing WHO data from 2000–2019 found that countries naturally cluster into high, medium, and low suicide mortality groups. Some European countries, like Estonia, Lithuania, and Hungary, similar to Slovakia, fall into the high suicide mortality rate category, especially among older men [

16].

The lethality of a suicide attempt is shaped by several factors, including access to the chosen method, awareness of its fatal potential, familiarity with its use, and the influence of substances such as alcohol or drugs [

11,

13]. Studies of psychiatric inpatients further indicate that those who employ highly lethal means often share identifiable demographic and clinical characteristics, though not all investigations have observed sex differences in lethality [

11]. Research more broadly suggests that men are more likely to employ highly lethal methods such as firearms or jumping in front of vehicles, whereas women more often attempt self-poisoning [

11,

13,

14].

Taken together, these findings show that suicidal behavior varies systematically across gender and age. For research on children and adolescents, the key implication is to investigate why suicidal behavior is more prevalent in youth, even if it less often results in death compared with older populations. These distinct age-related patterns suggest that specific neurobiological vulnerabilities, such as an immature stress-response, might play a role in driving the elevated risks observed in young people.

3. Psychological, Social, and Environmental Risk Factors for Suicidal Behavior

Suicidal behavior in children and adolescents is shaped by biological, psychological, social, and environmental influences. Due to the developmental immaturity of young people, which includes ongoing identity formation, reliance on caregivers, and limited emotion regulation, they are particularly vulnerable to these stressors [

17]. Based on this, contemporary research adopts a socio-ecological perspective, showing how risks across individual, relational, community, and societal domains accumulate and interact to trigger suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth [

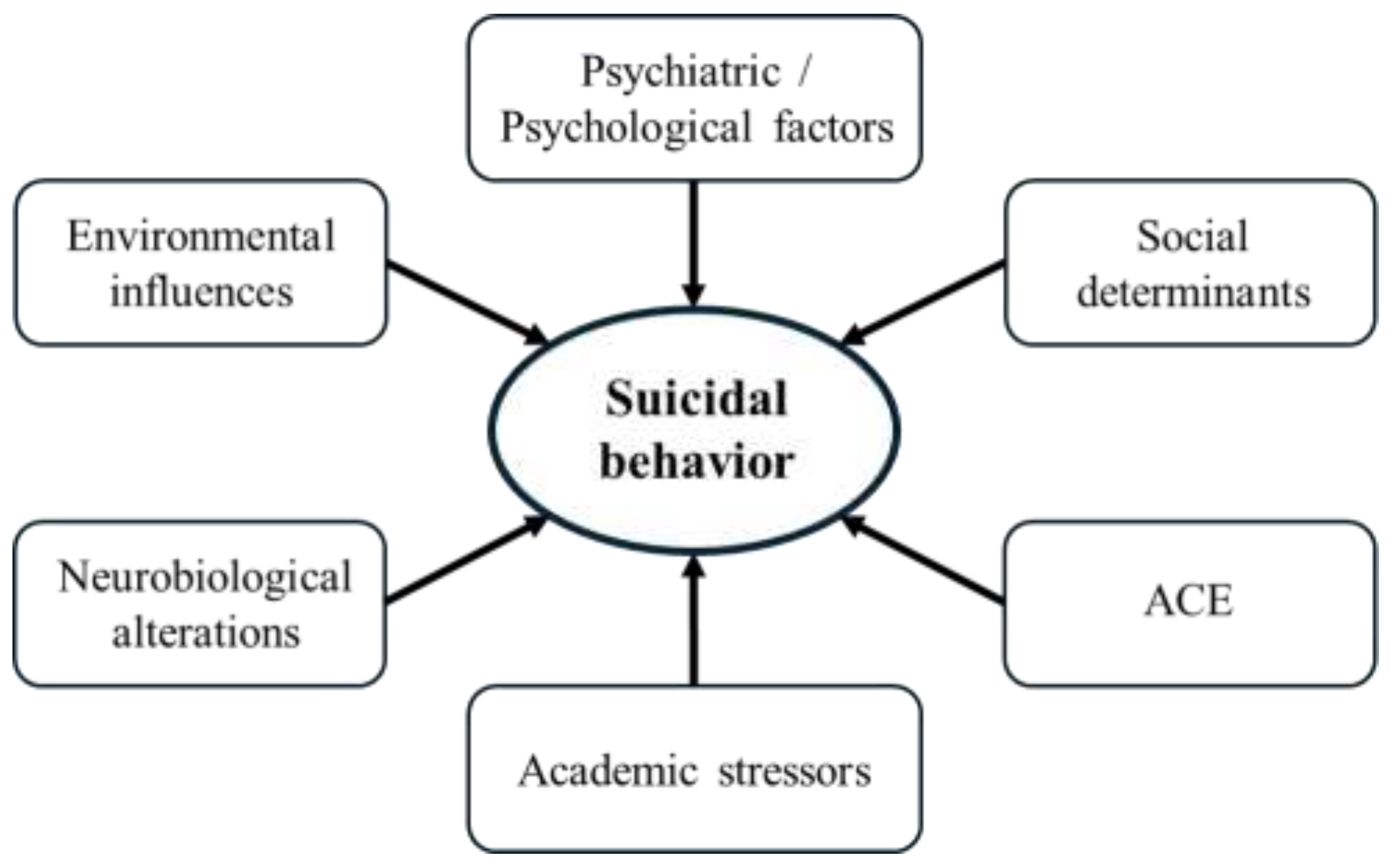

18]. Some of the main risk factors for suicidal behavior are shown in

Figure 1.

Psychiatric and psychological factors remain among the most robust predictors of suicidality. Depressive and anxiety disorders, as well as self-harming behavior, are consistently implicated in suicidal processes among adolescents [

17,

19,

20]. Emotion regulation difficulties, manifesting as low self-esteem, hopelessness, and poor coping strategies, have also emerged as strong correlates of suicidal behavior in youth populations [

5,

18,

21,

22,

23]. Notably, sleep disturbances constitute a modifiable risk factor. One study found that extending nightly sleep by one hour correlated with a reduction in suicidal ideation by up to 11% [

18].

Research consistently highlights the profound impact of adverse childhood experiences on suicidality. Childhood trauma, abuse, family dysfunction and related familial stressors significantly elevate suicidal risk among adolescents. Indeed, parental neglect, conflict, low socioeconomic status, and unstable family environment are frequently cited as foundational contributors to suicidal vulnerability [

18,

21,

22,

23]. Furthermore, broader social determinants such as racial and ethnic minority status, socioeconomic marginalization, and associated stigma exacerbate risk. Minorities, particularly multi-racial or marginalized youth groups, experience higher rates of suicide-related behaviors [

24].

Academic stressors have been increasingly recognized as significant contributors to suicidality among children and adolescents, operating through complex psychosocial and neurobiological pathways. Qualitative and systematic reviews show that pressures such as excessive workload, high-stakes examinations, and competitive educational environments are linked with greater suicidal ideation and attempts in youth populations [

25,

26]. These stressors rarely occur in isolation, often compounding existing vulnerabilities such as depression, anxiety, or bullying, thereby amplifying the risk of self-harm behaviors [

27,

28].

Evidence from Asia further highlights the magnitude of this problem. In Japan, stress related to school records and academic courses has been identified as a major predictor of suicidality among adolescents [

29]. In South Korea, academic achievement stress is strongly linked with suicidal ideation in young people [

30], and in South Asia, competitive entrance examinations have been documented as drivers of suicidal impulses among Bangladeshi students [

31]. While cultural dynamics differ, similar challenges are present in Slovakia and Central Europe, where academic demands and exam-related pressures have been shown to contribute to negative effects like elevated levels of stress, anxiety, and depression among students, underscoring their potential to worsen suicidality in vulnerable youth [

32,

33].

Cultural and structural components of society also shape suicidal behavior in young people. Evidence shows that sexual and gender minority adolescents are at particularly high risk, driven by stigma, discrimination, and hostile environments, with risks most significant in societies where laws and norms are restrictive [

18,

34]. Ethnic minority status and migration-related stressors likewise heighten vulnerability, as discrimination and exclusion erode mental health and increase suicidality [

17,

18]. Studies focusing on Black children show how racism, poverty, and limited access to care combine to increase suicide risk. This highlights the dangerous impact of facing multiple, overlapping disadvantages. [

35]. Religion further conditions outcomes. While faith communities may foster resilience, rigid or exclusionary doctrines can intensify marginalization, especially for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth [

36].

At the same time, broader societal determinants such as economic inequality, unemployment, and political environments represent structural risk factors that shape population-level suicide patterns [

37]. In other words, the risk is further influenced by demographic and contextual variables [

38]. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, urban residence and family job loss were linked with greater adolescent suicide attempts [

25].

From a practical standpoint, access to highly lethal means, such as firearms or toxic substances, is a major determining factor of whether suicidal crises in adolescents prove fatal [

1,

18]. Reviews consistently show that the availability of these methods, combined with unsafe storage, increases risk of suicide, while secure storage practices and policy restrictions are associated with reduced mortality [

1,

17]. Limiting access to lethal means is therefore one of the most available and effective strategies for preventing youth suicide [

1,

18].

Current research indicates that psychosocial stressors such as bullying may influence suicidality through neurobiological alterations, including hyperactivation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, serotonergic dysregulation, and reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels, which collectively impair stress regulation and neuroplasticity [

39,

40]. Given the accumulating body of scientific evidence in this area, this review focuses on biological risk factors for suicidal behavior in children and adolescents.

4. Biological Risk Factors for Suicidal Behavior

4.1. Genetic and Familial Factors

Genetic factors play a substantial role in shaping the risk of suicidal behavior in children and adolescents [

41,

42]. Studies comparing relatives and twins indicate that genetic liability plays a significant role in suicidality, with heritability estimates falling between 30 and 55 percent [

43]. Moreover, the risk to offspring of suicidal parents remains elevated even when controlling for shared environmental factors, suggesting that both inherited genetic liability and other familial influences, such as exposure to suicidal behavior of caretaking adults, independently contribute to youth vulnerability [

21,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47].

Genetic research on suicidality has historically focused on genes regulating stress responses and mood pathways, with SLC6A4 (the serotonin transporter) and BDNF among the most studied [

48,

49]. Early findings suggested that the short allele of 5-HTTLPR and the BDNF Val66Met variant might increase vulnerability to suicidal behavior, particularly under stress, but recent evidence indicates these effects are modest and highly context-dependent [

48,

50,

51]. Genes influencing the HPA axis, such as FKBP5, have also gained attention for their role in gene–environment interactions, especially when childhood trauma is present [

48,

49]. Foundational genome-wide association studies (GWAS) later confirmed that suicide risk is not attributable to individual common variants of large effect. This has decisively shifted the field toward polygenic risk models, which acknowledge that suicide’s heritability likely arises from the cumulative impact of many small genetic variations interacting with contextual stressors [

48,

52].

Recent findings using polygenic risk scores also suggest that genetic liability can intensify the effects of adverse experiences. Evidence shows that adolescents, and particularly adolescent girls, are more vulnerable when academic problems or substance use co-occur with elevated genetic risk for suicidal behavior. This interaction between genes and environment indicates that inherited predispositions may magnify the impact of negative psychosocial exposures early in life [

41].

4.2. Neurotransmitter Dysregulation and Impaired Neuroplasticity

4.2.1. Serotonergic System Dysfunction

Dysfunction within the central serotonin (5-HT) system is one of the most consistently identified neurobiological correlates of suicidal behavior [

49,

53]. Postmortem studies of suicide victims reveal a decreased density of serotonin transporters in key brain regions like the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, which may impair the brain’s capacity for top-down emotional and decision-making control [

40,

49]. This deficit in serotonin signaling is further supported by findings of low concentrations of the serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in the cerebrospinal fluid of individuals who attempt suicide [

49,

54]. One of the possible ways the brain appears to compensate for this low serotonergic activity is through the upregulation of postsynaptic 5-HT2A receptors and presynaptic 5-HT1A auto receptors in the prefrontal cortex and raphe nucleus, respectively [

40,

55].

Fundamental disruptions in serotonin signaling may be especially consequential because of heightened neural plasticity in adolescents, creating a significant vulnerability for the development of suicidal behaviors in response to stress [

49,

54,

55].

The clinical relevance of serotonergic dysfunction in suicidality is underscored by evidence from antidepressant treatment studies. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), medications that block serotonin reuptake and thereby increase its synaptic presence, are widely used as an effective first-line therapy for depression. As mentioned earlier, depressive disorders are associated with a heightened risk of suicidality [

56,

57,

58]. However, large-scale cohort and meta-analytic data indicate that initiation of SSRIs in adolescents and young adults can be associated with a transient increase in suicidal behavior, particularly in the first weeks of treatment [

56].

Serotonin’s role in suicide risk is therefore complex. SSRIs act on affective symptoms such as depressed mood and anxiety, with subsequent improvements in cognitive domains like guilt or loss of interest, which are closely linked to hopelessness and suicidal thinking [

59]. Treatment-emergent suicidal ideation and its worsening are not uniform phenomena. They are influenced by age, baseline severity, genetics, and comorbid conditions [

60]. These findings highlight both the importance of serotonin-targeting drugs in therapeutic strategies and the clinical necessity of close monitoring in vulnerable populations.

4.2.2. Dopaminergic Pathways in Reward and Cognition

The role of the dopaminergic system in suicide is less clearly defined than that of serotonin. However, its involvement in reward processing, motivation, and executive function suggests it may contribute to psychological traits underlying suicide risk [

49,

61]. A diminished capacity to process rewards may contribute to reduced sensitivity to positive reinforcement as well as hopelessness, one of the most consistent psychological predictors of suicidal behavior [

49,

54,

55].

Some studies report reduced dopaminergic activity in suicide attempters, for example, a blunted growth hormone response to the dopamine agonist apomorphine. However, postmortem studies have generally not found consistent alterations in dopamine receptor densities or dopamine transporter availability in suicide victims [

49]. Findings on dopamine metabolites haven’t been uniform. Reductions in 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and elevations in homovanillic acid (HVA) were reported in specific brain regions, but not consistently so across samples [

49,

62]. However, a more recent meta-analysis found significantly reduced CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) levels of HVA in suicide attempters, indicating decreased dopamine turnover [

63].

Taken together, these results suggest that if dopaminergic dysfunction contributes to suicide risk, its effects are likely subtle and context dependent. It may act in coordination with other neurotransmitter abnormalities and dysfunction in frontal–subcortical connections or cortico-striato-thalamic circuits, thereby impairing decision-making and cognitive control in vulnerable individuals [

49,

54,

64].

4.2.3. Glutamatergic/GABAergic Imbalance and Neuroplasticity

Converging evidence indicates that suicidal behavior is associated with a fundamental imbalance between the brain’s primary excitatory (glutamate) and inhibitory (gamma-aminobutyric acid, GABA) systems [

40,

54,

55]. Studies of postmortem brain tissue from individuals who died because of suicide have found altered expression of genes associated with glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus [

49,

55]. This dysregulation between excitatory and inhibitory processes is considered a critical component of a broader deficit in neuroplasticity (the brain’s ability to adapt and reorganize itself) [

40,

55].

BDNF is a key molecule for neuronal survival, growth, and synaptic plasticity [

65,

66]. Reduction in the levels of this molecule is frequently found in the brains and peripheral blood of individuals who exhibit suicidal behaviors [

40,

55]. This deficit in BDNF is believed to be a downstream consequence of multiple factors, including hyperactivity of the HPA stress axis and inflammation-induced glutamatergic overstimulation. These can be neurotoxic. Impairments in neuroplasticity may, in this way, underlie the cognitive deficits in learning and memory often observed in individuals who attempt suicide [

40,

49,

54,

55]. The rapid antisuicidal effects of ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor antagonist, further reinforce this link. Its mechanism of action is thought to be based on blocking of excitotoxicity and restoring synaptic plasticity, partly through the release of BDNF [

67,

68].

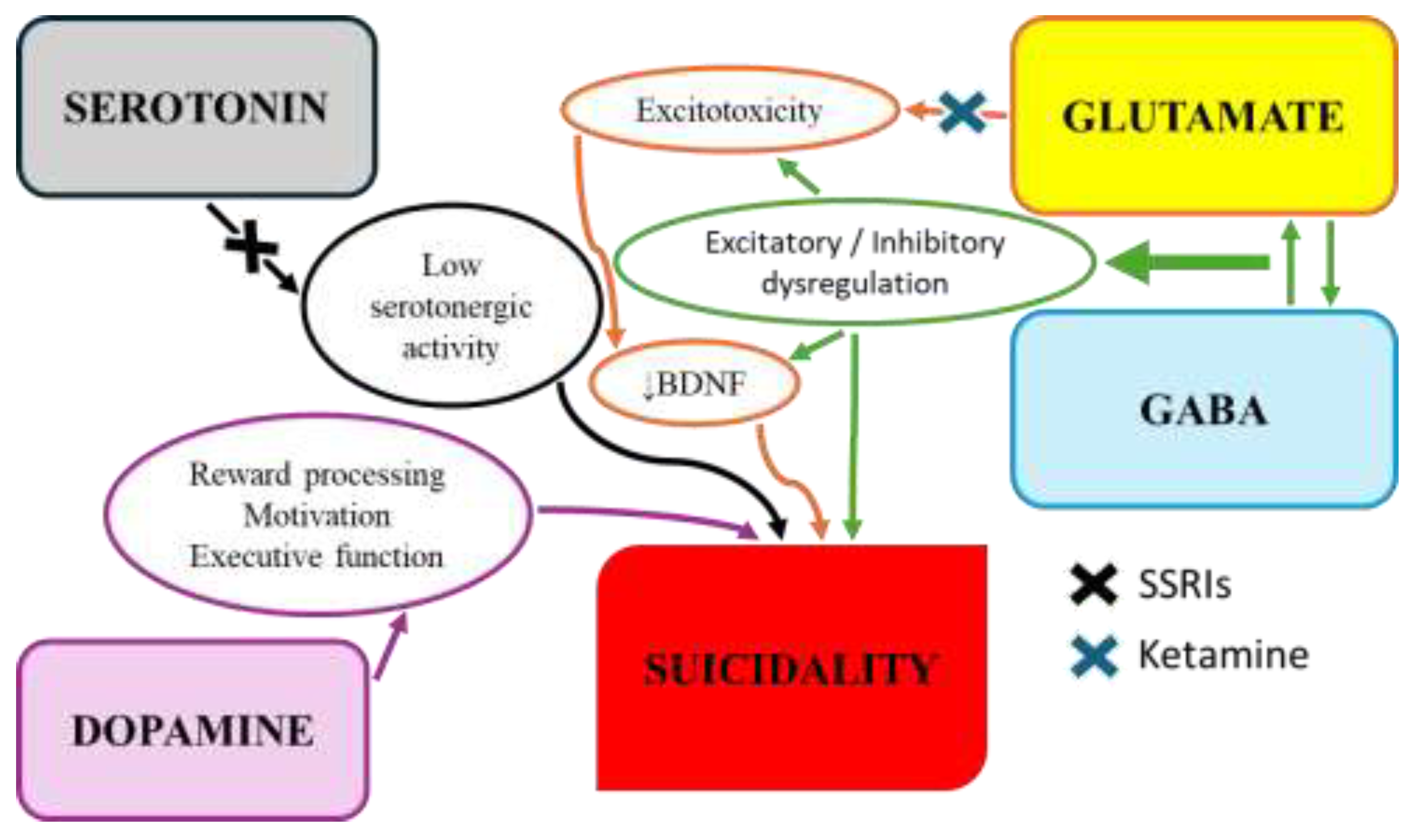

Figure 2 illustrates the interrelationships of neurotransmitters implicated in the pathophysiology of suicidal behavior as well as potential pharmacological interventions.

4.3. Stress, Inflammation, and Oxidative Imbalance

Stress-related biology is among the most extensively studied mechanisms linking adversity to suicidal behavior in youth. Beyond the previously discussed neurotransmitters, the pathophysiology of suicidality may also involve disturbances in the HPA axis and the kynurenine pathway, immune dysregulation, neuroinflammation, and redox imbalance [

40,

54,

69,

70,

71].

4.3.1. HPA Axis Dysregulation

A widely accepted biological framework for suicide emphasizes the interplay between stress-response systems and inflammatory mechanisms, with the HPA axis as a central component [

40,

54,

55]. Postmortem studies indicate chronic activation of the HPA axis in suicide victims, including adrenal hypertrophy, thickened cortical layers, and elevated corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) in corticolimbic regions [

55,

69,

72].

Clinical studies add further support, though findings in young populations remain inconsistent. Some report elevated cortisol associated with suicidal behaviors, while others identify blunted cortisol responses to laboratory stress paradigms, suggesting heterogeneity in HPA dysregulation across adolescents [

40,

49,

73]. Consistent with the hyperactivity pattern, in a large Mexican cohort, cortisol concentrations were elevated in people with a history of suicide attempts in comparison to healthy controls. The increase was most pronounced in those with multiple attempts and in attempters who also met criteria for depression [

74]. A study of psychiatric inpatients using hair cortisol analysis showed that lower cumulative cortisol output was present before suicide attempts. These patients also exhibited reduced glucocorticoid receptor gene expression together with signs of heightened inflammation, including increased C-reactive protein (CRP) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels [

75]. Beyond cortisol, elevated corticotropin-releasing hormone has been detected in stress-regulatory brain regions [

69,

76]. In adolescents, an abnormal HPA axis functioning is thought to underlie poor emotion regulation, itself a risk factor of suicidal behavior [

77].

Taken together, this body of evidence points to divergent patterns: hyperactivity in some cases and hypocortisolism in others. Such variation suggests that developmental stage, psychiatric comorbidity, and accumulated stress may influence the trajectory of HPA axis changes [

69,

74,

75,

78]. Importantly, youth-focused studies demonstrate that lower hair cortisol can differentiate suicide attempters from those with ideation alone, underscoring its potential as a marker of short-term risk [

75]. Overall, both high and low HPA activity appear to represent maladaptive adaptations to adversity that link stress to a higher risk of suicidal behavior [

69,

72,

74,

75].

4.3.2. Inflammation & Neuroinflammation

Stress-induced alterations in the HPA axis are closely coupled with immune activation. High levels of proinflammatory cytokines, notably interleukin-6 (IL-6) and TNF-α, have been detected in the samples of blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and post-mortem brain tissue of suicidal individuals [

55,

69,

70,

73].

Meta-analytic evidence indicates that major depressive disorder (MDD) is consistently accompanied by elevated levels of these cytokines as well, providing strong support for activation of the immune system in depression [

79,

80]. More recent work in pediatric populations suggests possible elevations in TNF-α. However, findings remain inconsistent due to the limited number of studies available [

81]. These cytokines are not merely peripheral markers. They interact with stress-regulatory systems and neurotransmitter pathways, thus shaping core depressive symptoms and potentially influencing treatment [

82].

The role of nitric oxide (NO) in suicidal behavior is contentious, as studies yield inconsistent findings [

71]. While NO is an important neurotransmitter implicated in depression pathophysiology, some research detected elevated NO concentrations in depressed patients with suicidal thoughts [

83]. Conversely, a recent study on adolescents with MDD found significantly reduced serum NO levels in those with a history of suicide attempts compared to non-attempters. This discrepancy may reflect NO’s dual function, acting as a signaling molecule at low concentrations but as a damaging free radical in excess [

71,

83].

Beyond peripheral changes, converging neuropathological studies highlight neuroinflammatory processes within the brain. Postmortem analyses of individuals who died by suicide reveal an increased ratio of primed to resting microglia and greater macrophage recruitment in the anterior cingulate white matter, indicative of low-grade neuroinflammation [

84]. Microglial activation is of particular interest because these cells regulate local immune responses, and when chronically stimulated, they can release neurotoxic mediators, contributing to alterations in white-matter integrity [

82,

84]. At the molecular level, inflammatory mediators converge on transcriptional regulators such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), which is activated by cytokine signaling and oxidative stress, further amplifying immune responses and contributing to neuroprogression [

83].

Importantly, pediatric studies suggest that these mechanisms are evident from early stages of psychiatric disorders. Children and adolescents with depressive disorders exhibit elevated inflammatory and oxidative stress markers alongside reduced antioxidant defenses, underscoring that immune dysregulation is not limited to adult depression [

85,

86]. Findings from the Slovak DEPOXIN project provide further support, demonstrating that cytokine activation, redox imbalance, shifts in lipid mediators, and neuroendocrine stress responses collectively define a characteristic biological profile in youth depression [

86].

Taken together, current evidence supports a framework in which depression and suicidal behavior involve both systemic and central immune dysregulation. These processes interact with other biological systems to shape vulnerability [

79,

82,

83,

84].

4.3.3. Redox Imbalance and Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress denotes a state in which reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) outpace the organism’s antioxidant defense systems. It is increasingly recognized for its role in depression and suicidality. The brain’s high lipid content, oxygen demand, and relatively weak antioxidant buffering make it especially vulnerable to oxidative injury [

71,

83,

87].

Findings from pediatric cohorts with depressive disorders highlight consistent reductions in glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity [

85,

86], while results for superoxide dismutase (SOD) are more heterogeneous. Some studies observed no baseline difference from controls [

85], others reported decreased SOD activity in depressed youth [

88], and recent work found increased SOD among adolescents with suicide attempts, suggesting a possibly compensatory or stress-related response [

71]. This pattern indicates a robust GPx deficiency alongside variable SOD changes that may be related to the illness stage or suicidality.

Markers of oxidative damage, including nitrotyrosine, lipid peroxidation products (for example, 8-isoprostane), and advanced oxidation protein products (AOPP), are elevated in depressed youth and correlate with symptom severity [

71,

83,

87]. Beyond its role in inflammation, the dysregulation of NO metabolism has also been linked to suicidal ideation, further implicating redox imbalance in suicide risk [

71,

83].

Depressive disorder in children and adolescents is significantly influenced by the ratio of omega-6 (pro-inflammatory properties) to omega-3 (anti-inflammatory properties) fatty acids (FAs) [

86]. Intervention trials within the DEPOXIN project show that omega-3 FAs reduce oxidative stress markers, enhance antioxidant defenses, and alleviate depressive symptoms [

85]. Recently, it was observed that higher levels of omega-3 FAs are associated with reduced risk of self-harm and suicidal ideation [

89]. Additional evidence suggests a positive correlation between cortisol and lipoperoxides, as well as between aldosterone and 8-isoprostane. This ties endocrine stress responses to oxidative injury and may help explain pathways of vulnerability to suicidality [

85,

86,

90].

Redox and inflammatory signaling appear bidirectionally coupled, and redox changes may coincide with neuroimmune alterations observed in individuals who died by suicide and had a depressive disorder [

82,

83,

84].

4.3.4. Kynurenine Pathway

A key downstream consequence of inflammation and oxidative stress is the activation of the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway. Pro-inflammatory cytokines stimulate indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which diverts tryptophan metabolism away from serotonin synthesis and toward kynurenine production [

70,

83,

91,

92]. This process reduces the availability of serotonin precursors while generating neuroactive metabolites that influence glutamatergic neurotransmission [

91,

92].

Kynurenine can be metabolized into either the neuroprotective kynurenic acid or into neurotoxic derivatives such as 3-hydroxykynurenine and quinolinic acid. Evidence indicates that in depressive states, particularly those associated with suicidal behavior, metabolism shifts toward the neurotoxic branch [

70,

91,

92,

93]. For example, elevated cerebrospinal fluid quinolinic acid (QUIN) has been observed in suicide attempters, whereas alterations in blood kynurenine/tryptophan ratios are inconsistently reported and may reflect inflammatory activation rather than a suicide-specific change [

70,

91,

93,

94]. Elevated QUIN has been demonstrated in the cerebrospinal fluid of suicide attempters, while protective metabolites such as picolinic acid (PIC) are reduced, producing an unfavorable PIC/QUIN ratio [

91].

These mechanisms also appear early in life. In adolescents, Ilavská et al. [

95] found a disrupted serotonin–kynurenine balance. At the same time, the DEPOXIN project demonstrated that changes in the kynurenine pathway occur alongside redox and inflammatory alterations in youth depression [

86]. Reviews further emphasize that oxidative stress can amplify IDO activity, thereby reinforcing a feedback loop in which redox and immune signals drive the pathway [

83,

93].

Overall, the kynurenine pathway provides a mechanistic bridge linking peripheral immune activation and oxidative stress to central neurotransmitter imbalances, thereby contributing to both depression and suicide risk.

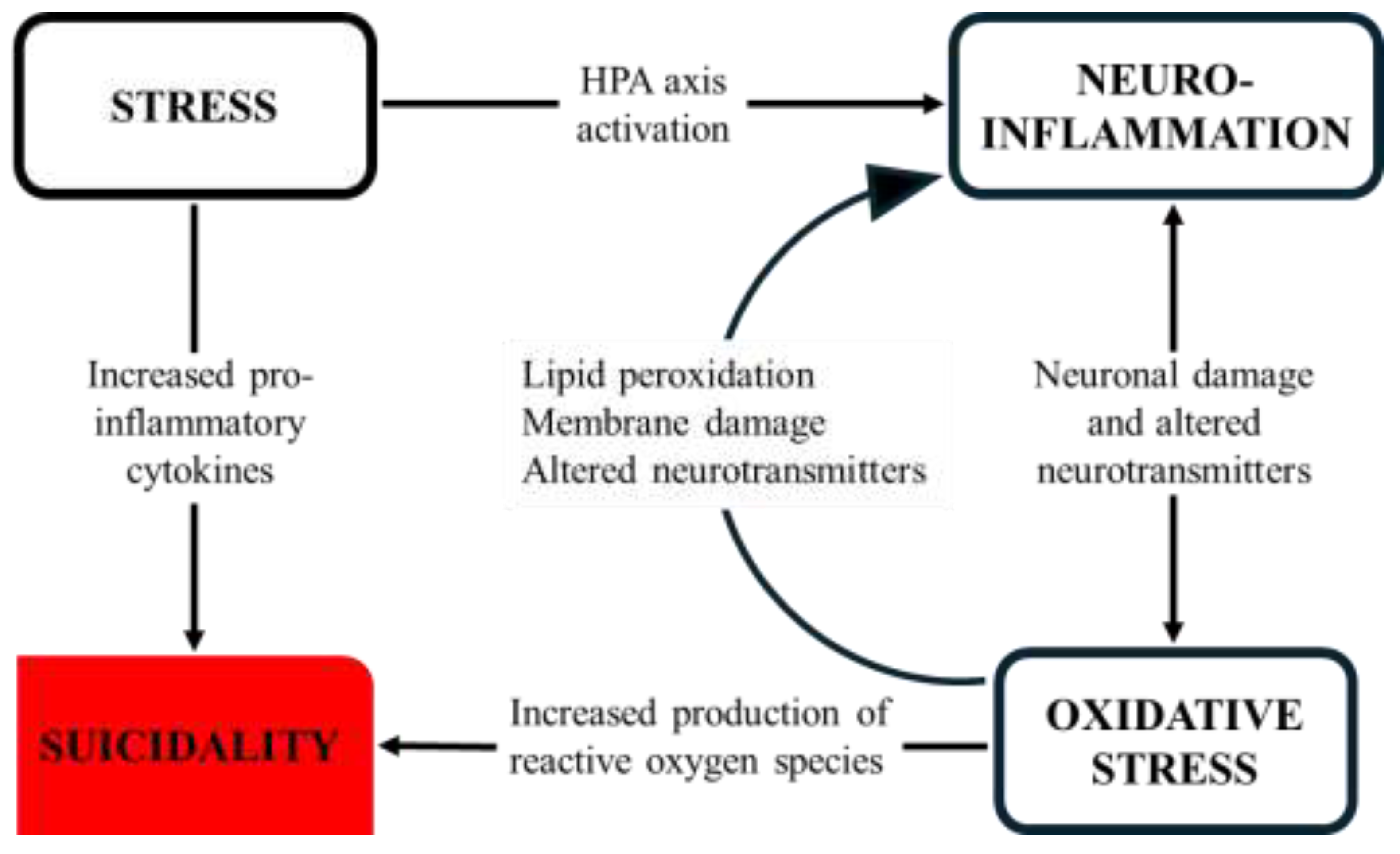

Figure 3 shows relationships between psychological stress, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and suicidality.

4.4. Neurodevelopmental and Neurocircuitry Vulnerabilities

Neurodevelopmental disorders substantially heighten vulnerability to suicidal thoughts and behaviors. In a large South London cohort, boys with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) had nearly threefold higher risk of emergency self-harm compared to peers. At the same time, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) predicted self-harm in both sexes after adjusting for confounders [

96]. A recent meta-analysis confirmed elevated odds of suicidal ideation and attempts in youth with ADHD, although effect sizes varied across study designs, underscoring heterogeneity [

97]. Trait-level data further suggest cumulative risk when autism and ADHD traits co-occur, while positive childhood experiences show protective effects, particularly at higher ADHD-trait levels [

98].

Neuroimaging evidence implies frontolimbic circuits in adolescent suicidality. Abnormalities in medial prefrontal and anterior cingulate regions are repeatedly observed in suicidal youth. These brain structures are critical for affect regulation and self-referential processing [

99]. In bipolar adolescents and young adults, suicide attempters showed reduced orbitofrontal and hippocampal grey matter volumes, lower uncinate fasciculus integrity, and diminished amygdala-ventral prefrontal connectivity compared to non-attempters. Notably, only the connectivity measures correlated with suicidal ideation and attempt lethality [

100]. During the first-episode in unmedicated female adolescents with major depression, attempters exhibited altered activity in insular and precentral cortices and abnormal coupling with the cingulate cortex [

101]. While Liu et al. [

101] did not explicitly frame their findings in network terms, converging evidence implicates cingulate, prefrontal, and striatal systems in altered salience attribution and executive control in suicidality [

99,

102,

103].

Early developmental influences may further bias neural systems toward vulnerability. Prospective studies link prenatal maternal distress to long-term alterations in amygdala volume and limbic–prefrontal connectivity, suggesting that stress biology can shape emotion regulation circuits before adolescence [

104]. Longitudinal evidence further indicates that maternal psychological distress during pregnancy is associated with alterations in brain structure, such as smaller overall brain volume and altered cortical thinning, in offspring (including school-aged children). This is consistent with the notion of prenatal programming of neural systems, which in turn affects fetal brain development and contributes to an elevated risk for later psychopathology [

105].

Adverse perinatal conditions such as preterm birth, low fetal growth, and pregnancy complications have been associated with increased suicide risk in offspring, although part of this vulnerability appears to reflect shared familial or prenatal environmental factors rather than direct causal effects [

106,

107].

Collectively, neurodevelopmental diagnoses, trait configurations, and early neurobiological shaping converge on circuitry that is undergoing rapid remodeling during adolescence. This convergence provides insight into why some youths are especially susceptible to suicidal thoughts and behaviors and highlights preventive levers, including positive childhood experiences, that may recalibrate developmental trajectories [

96,

98,

99].

4.5. Sleep and Circadian Rhythm Dysregulation

Disturbances in sleep and circadian regulation are consistently associated with suicidal ideations and behaviors in young people, independent of co-occurring depression [

108]. In a large longitudinal cohort of preadolescents, parent-reported sleep problems like nightmares and excessive daytime sleepiness in particular predicted suicidal ideation and attempts over a two-year follow-up, even after adjusting for baseline affective symptoms [

109]. Mechanistic models suggest that circadian disruption and insufficient sleep affect serotonergic signaling, prefrontal–limbic regulation, and impulsivity, although these remain hypotheses rather than demonstrated causal pathways [

110]. Because sleep problems are common and modifiable, their assessment and treatment represent accessible clinical targets to potentially reduce near-term suicide risk [

108,

109,

110].

5. Biologically Informed Treatment and Prevention Methods

Guided by the thesis that biologically informed, mechanism-targeted strategies can reduce suicidal risk beyond nonspecific symptom relief, recent evidence highlights three complementary avenues: rapid glutamatergic modulation, longer-term neuroprotective agents, and inflammation- or redox-guided interventions [

83,

91,

111].

Accumulating trials and syntheses indicate that ketamine can acutely lower suicidal ideation in adult patients within hours, though durability and optimal maintenance strategies remain inconsistent [

111]. Findings are even less robust in adolescents. Beyond controlled trials, small case series of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy describe rapid improvements that include reductions in suicidal thoughts and self-harm urges in some patients [

112]. These uncontrolled observations contrast with a randomized study in which low-dose intravenous ketamine did not outperform placebo on suicidal ideation and produced more dissociation [

113]. Ongoing work is examining whether repeated ketamine infusions combined with psychotherapy can sustain benefits during the high-risk post-discharge period for patients aged 14 to 30 [

114]. Esketamine nasal spray is clinically used in adults for treatment-resistant depression. However, its implementation in the younger population is limited, as evidence is restricted to small exploratory studies [

115], and it lacks pediatric regulatory approval [

86].

The therapeutic mechanisms of established long-term anti-suicidal agents, namely lithium and clozapine, are increasingly understood to involve the modulation of neurobiological pathways mentioned in this paper [

111,

116]. Lithium’s effects on impulsivity, aggression, and intracellular signaling pathways, such as glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK-3β), align with biological risk models. Ecological and registry studies suggest that higher regional prescribing of lithium is associated with lower adolescent suicide mortality, particularly among males [

116,

117,

118]. Clozapine, supported in adults by the InterSePT trial, shows a similar pattern in adolescents, where regional prescribing has been linked with lower suicide deaths [

117,

118]. Yet for both lithium and clozapine, pediatric evidence remains limited to correlational and ecological studies, with no randomized controlled trials available to establish causal anti-suicidal efficacy in youth [

116,

117,

118,

119].

Based on links between suicidal risk, inflammation-driven kynurenine pathway, and glutamatergic dysregulation, some possible prevention and treatment strategies emerge, for example, stratification by inflammatory/kynurenine signatures (e.g., IL-6, QUIN/KYNA), and repurposing of anti-inflammatory or microglia-modulating agents (minocycline, cytokine blockade, IDO-1 inhibition) [

82,

91].

Pediatric intervention studies add practical weight. Omega-3 PUFA supplementation has been shown to alter kynurenine/serotonin balance and improve antioxidant capacity in depressed adolescents. Although baseline levels of BDNF and GPx were correlated with biomarkers of depression in these youths, the supplementation itself did not produce a statistically significant change in their activity [

83,

90,

95]. These findings align with broader Slovak contributions that highlight redox imbalance and inflammation as key biological vulnerabilities in youth [

87]. Moreover, oxidative-stress biomarkers such as altered SOD, NO, and uric acid are increasingly identified as correlates of suicide attempt risk in adolescent MDD, opening avenues for biomarker-guided risk stratification [

71].

6. Discussion

The neurobiology of suicidal behavior in youth reflects a complex interplay of stress reactivity, inflammation, and downstream molecular alterations that differ in several aspects from adult pathophysiology. While research has highlighted key biological pathways, the evidence base is constrained by methodological limitations and a persistent gap between experimental findings and clinical application.

Current data suggest a cascade of biological changes that heighten suicide risk in vulnerable young people [

69]. Biological vulnerabilities, including redox and inflammatory imbalance, may amplify cognitive states of defeat and entrapment, thereby linking depressive symptomatology to suicidal ideation in adolescents [

120]. Psychosocial stressors can trigger HPA axis disruption and low-grade neuroinflammation [

69,

95]. Although HPA abnormalities are consistently reported, cortisol results vary. Some studies indicate hyperactivity, while others (particularly in adolescents) show attenuated responses after chronic stress exposure [

69,

71]. Elevated inflammatory markers, such as a higher monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio in MDD patients with recent suicide attempts, further support immune involvement [

121].

Inflammatory activation is believed to induce IDO activity, diverting tryptophan metabolism from serotonin toward the kynurenine pathway [

95]. This shift reduces serotonergic precursors and increases neuroactive metabolites such as quinolinic acid, an NMDA agonist implicated in excitotoxicity and oxidative stress [

40]. Clinical data shows altered antioxidant systems, including elevated superoxide dismutase activity [

95,

121], while Mendelian randomization analyses suggest that genetically lower uric acid (a potent antioxidant) is associated with an increased risk of suicide attempts [

71]. These molecular alterations are believed to contribute to dysfunction in circuits regulating emotion and cognition. Reduced BDNF is frequently reported in suicidality, and in pediatric samples, BDNF correlates with oxidative stress indices, consistent with impaired plasticity [

40,

95,

122]. Importantly, evidence indicates that adolescent metabolic and inflammatory profiles diverge from adult patterns, reinforcing the need for youth-specific models [

86,

108].

Therapeutic evidence illustrates these differences. In adults, lithium, ketamine, and clozapine demonstrate substantial anti-suicidal efficacy in mood disorders and schizophrenia [

40,

111]. In younger populations, lithium and ketamine show preliminary signals of benefit, but findings are limited to small, heterogeneous studies and remain insufficient without further randomized trials [

115,

116]. The dynamic neurobiology of adolescence likely influences stress responsivity and treatment effects [

108]. This developmental context may partly explain epidemiological patterns observed in Slovakia and globally, where adolescent females attempt suicide at high rates but mortality remains lower than in older men [

8,

15]. Neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD and ADHD add further risk, linked to impulsivity, emotion dysregulation, and heightened vulnerability to adverse childhood experiences [

96,

97,

98,

123].

Methodological shortcomings hamper research progress. Most studies remain cross-sectional, limiting causal inference [

17,

18]. While some longitudinal work is emerging, such as ADHD-focused cohorts [

97], these remain rare. Biomarker research is constrained by small samples, inconsistent diagnostic criteria, and a lack of standardized assays, which makes replication and synthesis difficult [

95,

121]. Pediatric clinical trials face similar obstacles. Underpowered designs and methodological heterogeneity yield inconsistent results for lithium and ketamine [

115,

116]. Collectively, these issues hinder the development of a reliable and generalizable evidence base.

Despite advances in mapping biological pathways, translation into clinical tools for predicting or preventing suicide in youth remains distant. Biomarkers such as cytokines or oxidative stress markers lack sufficient reliability for individual-level prediction [

71]. Bridging this gap requires large, multicenter longitudinal studies with standardized protocols and diverse samples. At the same time, risk-focused models are inadequate. Evidence indicates that intrapersonal resources like positive self-perceptions and self-worth are prospectively associated with lower subsequent suicidal ideation and attempts [

124], while school belonging, peer support, and relationships with non-parent adults provide additional protection [

17,

98]. Yet systematic reviews consistently show that resilience factors are understudied relative to risks, leaving a critical gap [

18]. Without integrating protective processes alongside biological vulnerabilities, neurobiological research will have limited clinical utility for suicide prevention in youth.

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

The accumulated evidence makes it clear that biology contributes meaningfully to suicide risk in young people. Still, it does so in interaction with developmental, psychological, and social contexts rather than in isolation. Current findings are valuable for understanding vulnerability but are not yet precise enough to guide individual prediction or treatment. The next steps for the field are therefore less about cataloguing additional correlates and more about building integrative, longitudinal models that clarify causal pathways and identify when biological signals matter most. Progress will depend on large, collaborative studies that apply standardized methods, bridge biomarkers with lived experience, and move beyond risk to test protective factors such as positive childhood experiences, school belonging, and sleep interventions. Clinical trials in youth must prioritize age-specific designs, combine mechanism-based therapies with psychosocial approaches, and evaluate not only symptom relief but also genuine reductions in suicidal behavior. Ultimately, reducing the risk of death by suicide in children and adolescents will require a synthesis of biological insight, developmental sensitivity, and socio-ecological interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V., J.T., and Z.Ď.; writing – review and editing, M.V., J.J., J.T., B.K., J.M., and Z.Ď.; visualization, M.V., Z.Ď., and J.J.; supervision, J.T. and Z.Ď.; funding acquisition, Z.Ď.; project administration, M.V. and B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the VEGA grant 01/0183/24 of the Ministry of Education, Research, Development and Youth of the Slovak Republic (formerly Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of GenAI during the preparation of this manuscript. Specifically, ChatGPT 5 (OpenAI) and Gemini 2.5 Pro (Google) were utilized for language editing, grammar correction, and to assist in the preliminary literature search. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and edited all AI-generated output and take full responsibility for the accuracy, integrity, and final content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5-HIAA |

5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid |

| 5-HT |

Serotonin |

| 5-HTTLPR |

Serotonin-transporter-linked promoter region |

| ACE |

Adverse childhood experiences |

| ADHD |

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| AOPP |

Advanced oxidation protein products |

| BDNF |

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CRH |

Corticotropin-releasing hormone |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| CSF |

Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DOPAC |

3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid |

| FAs |

Fatty acids |

| FKBP5 |

FK506-binding protein 5 |

| GABA |

Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GPx |

Glutathione peroxidase |

| GSK-3β |

Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta |

| GWAS |

Genome-wide association studies |

| HPA |

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| HVA |

Homovanillic acid |

| IDO |

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| LGBTQ |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning |

| MDD |

Major depressive disorder |

| NCZI |

National Health Information Centre |

| NF-κB |

Nuclear factor-κB |

| NMDA |

N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| NO |

Nitric oxide |

| PIC |

Picolinic acid |

| PUFA |

Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| QUIN |

Quinolinic acid |

| RNS |

Reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| SLC6A4 |

Solute carrier family 6 member 4 |

| SOD |

Superoxide dismutase |

| SSRIs |

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor-α |

References

- Hink, A.B.; Killings, X.; Bhatt, A.; Ridings, L.E.; Andrews, A.L. Adolescent Suicide—Understanding Unique Risks and Opportunities for Trauma Centers to Recognize, Intervene, and Prevent a Leading Cause of Death. Curr Trauma Rep 2022, 8, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuccio, P.; Amerio, A.; Grande, E.; La Vecchia, C.; Costanza, A.; Aguglia, A.; Berardelli, I.; Serafini, G.; Amore, M.; Pompili, M.; et al. Global Trends in Youth Suicide from 1990 to 2020: An Analysis of Data from the WHO Mortality Database. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 70, 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilsen, J. Suicide and Youth: Risk Factors. Front Psychiatry 2018, 9, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkevi, A.; Rotsika, V.; Arapaki, A.; Richardson, C. Adolescents’ Self-Reported Suicide Attempts, Self-Harm Thoughts and Their Correlates across 17 European Countries. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2012, 53, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, C.D.; Martínez-Cárdenas, C.F. Risk Factors and Profiles of Reattempted Suicide in Children Aged Less than 12 Years. An Pediatr (Engl Ed) 2024, 101, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, L.S.H.; de la Hoz Restrepo, F.; Paternina, A.M.R. Risk and Protective Factors for Suicidal Ideation and Attempt in Latin American Adolescents and Youth: Systematic Review. Psicología desde el Caribe 2024, 41, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocaoglu, C. Editorial: The Neurobiology of Suicide: The ‘suicidal Brain’. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCZI Samovraždy a Samovražedné Pokusy. Available online: https://data.nczisk.sk/statisticke_vystupy/Samovrazdy_samovrazedne_pokusy/Samovrazdy_a_samovrazedne_pokusy_v_SR_2024.xlsx (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Gracia, R.; Pamias, M.; Mortier, P.; Alonso, J.; Pérez, V.; Palao, D. Is the COVID-19 Pandemic a Risk Factor for Suicide Attempts in Adolescent Girls? J Affect Disord 2021, 292, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yard, E.; Radhakrishnan, L.; Ballesteros, M.F.; Sheppard, M.; Gates, A.; Stein, Z.; Hartnett, K.; Kite-Powell, A.; Rodgers, L.; Adjemian, J.; et al. Emergency Department Visits for Suspected Suicide Attempts Among Persons Aged 12–25 Years Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, January 2019–May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021, 70, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardelli, I.; Rogante, E.; Sarubbi, S.; Erbuto, D.; Cifrodelli, M.; Concolato, C.; Pasquini, M.; Lester, D.; Innamorati, M.; Pompili, M. Is Lethality Different between Males and Females? Clinical and Gender Differences in Inpatient Suicide Attempters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 13309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez-Sánchez, C.M.; Camacho-Ruiz, J.A.; Castelli, L.; Limiñana-Gras, R.M. Exploring the Role of Masculinity in Male Suicide: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry International 2025, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Brief Report: Sex Differences in Suicide Rates and Suicide Methods among Adolescents in South Korea, Japan, Finland, and the US. J Adolesc 2015, 40, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Mendizabal, A.; Castellví, P.; Parés-Badell, O.; Alayo, I.; Almenara, J.; Alonso, I.; Blasco, M.J.; Cebrià, A.; Gabilondo, A.; Gili, M.; et al. Gender Differences in Suicidal Behavior in Adolescents and Young Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Int J Public Health 2019, 64, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuin, M.; de Leo, D. Suicide-Related Mortality Trends in Europe, 2012–2021. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2025, 22, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckeviciene, E.; Kasperiuniene, J. Global Suicide Mortality Rates (2000–2019): Clustering, Themes, and Causes Analyzed through Machine Learning and Bibliographic Data. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2024, 21, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, R.; Connell, T.; Foster, M.; Blamires, J.; Keshoor, S.; Moir, C.; Zeng, I.S. Risk and Protective Factors of Self-Harm and Suicidality in Adolescents: An Umbrella Review with Meta-Analysis. J. Youth Adolescence 2024, 53, 1301–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prades-Caballero, V.; Navarro-Pérez, J.-J.; Carbonell, Á. Factors Associated with Suicidal Behavior in Adolescents: An Umbrella Review Using the Socio-Ecological Model. Community Ment Health J 2025, 61, 612–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, L.L.; Lee, J.; Rahmandar, M.H.; Sigel, E.J.; Adolescence, C.O.; Council on Injury, V. Suicide and Suicide Risk in Adolescents. Pediatrics 2024, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEvoy, D.; Brannigan, R.; Cooke, L.; Butler, E.; Walsh, C.; Arensman, E.; Clarke, M. Risk and Protective Factors for Self-Harm in Adolescents and Young Adults: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. J Psychiatr Res 2023, 168, 353–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamón, M.J.; Javela, J.J.; Ortega-Bechara, A.; Matar-Khalil, S.; Ocampo-Flórez, E.; Uribe-Alvarado, J.I.; Cabezas-Corcione, A.; Cudris-Torres, L. Social Determinants and Developmental Factors Influencing Suicide Risk and Self-Injury in Healthcare Contexts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2025, 22, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Fernandez, J.; Jiménez-Treviño, L.; Andreo-Jover, J.; Ayad-Ahmed, W.; Bascarán, T.B.; Canal-Rivero, M.; Cebria, A.; Crespo-Facorro, B.; De la Torre-Luque, A.; Diaz-Marsa, M.; et al. Network Analysis of Influential Risk Factors in Adolescent Suicide Attempters. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2024, 18, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Song, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Lin, J.; Chen, J. Relevant Factors Contributing to Risk of Suicide among Adolescents. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-Q.; Wang, X. Adolescent Suicide Risk Factors and the Integration of Social-Emotional Skills in School-Based Prevention Programs. World J Psychiatry 2024, 14, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcillo, V.; Ferrer-Ribot, M.; Mut-Amengual, B.; Bagur, S.; Rosselló, M.R. Mental Health and Suicide Attempts in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel) 2025, 13, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marraccini, M.E.; Pittleman, C.; Griffard, M.; Tow, A.C.; Vanderburg, J.L.; Cruz, C.M. Adolescent, Parent, and Provider Perspectives on School-Related Influences of Mental Health in Adolescents with Suicide-Related Thoughts and Behaviors. J Sch Psychol 2022, 93, 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, G.V.R.; Arias, P.; de la Torre-Luque, A.; Singer, J.B.; Lagunas, N. Depression, Anxiety, and Suicide Among Adolescents: Sex Differences and Future Perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2025, 14, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahumud, R.A.; Dawson, A.J.; Chen, W.; Biswas, T.; Keramat, S.A.; Morton, R.L.; Renzaho, A.M.N. The Risk and Protective Factors for Suicidal Burden among 251 763 School-Based Adolescents in 77 Low- and Middle-Income to High-Income Countries: Assessing Global, Regional and National Variations. Psychological Medicine 2022, 52, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagamitsu, S.; Mimaki, M.; Koyanagi, K.; Tokita, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Hattori, R.; Ishii, R.; Matsuoka, M.; Yamashita, Y.; Yamagata, Z.; et al. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Suicidality in Japanese Adolescents: Results from a Population-Based Questionnaire Survey. BMC Pediatr 2020, 20, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, Y.S.; Joo, H.J.; Park, E.-C. Association between Stress Types and Adolescent Suicides: Findings from the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Front Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1321925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M.A.; Al-Mamun, F.; Hasan, M.E.; Roy, N.; ALmerab, M.M.; Gozal, D.; Hossain, Md.S. Exploring Suicidal Thoughts among Prospective University Students: A Study with Applications of Machine Learning and GIS Techniques. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska, A.; Liska, D.; Cieślik, B.; Wrzeciono, A.; Broďáni, J.; Barcalová, M.; Gurín, D.; Rutkowski, S. Stress Levels and Mental Well-Being among Slovak Students during e-Learning in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare (Basel) 2021, 9, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavurova, B.; Ivankova, V.; Rigelsky, M.; Mudarri, T.; Miovsky, M. Somatic Symptoms, Anxiety, and Depression Among College Students in the Czech Republic and Slovakia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatchel, T.; Polanin, J.R.; Espelage, D.L. Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among LGBTQ Youth: Meta-Analyses and a Systematic Review. Archives of Suicide Research 2021, 25, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, I.; Assan, M.A.; Pierre, K.; Gunn, J.F.; Metzger, I.; Hamilton, J.; Arugu, E. Suicide among Black Children: An Integrated Model of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide and Intersectionality Theory for Researchers and Clinicians. J Black Stud 2020, 51, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stack, S. Contributing Factors to Suicide: Political, Social, Cultural and Economic. Prev Med 2021, 152, 106498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirkis, J.; Bantjes, J.; Dandona, R.; Knipe, D.; Pitman, A.; Robinson, J.; Silverman, M.; Hawton, K. Addressing Key Risk Factors for Suicide at a Societal Level. The Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e816–e824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Mukherjee, S. Health-Behaviors Associated With the Growing Risk of Adolescent Suicide Attempts: A Data-Driven Cross-Sectional Study. Am J Health Promot 2021, 35, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamarchuk, I.S.; Vaillancourt, T. Integrative Brain Dynamics in Childhood Bullying Victimization: Cognitive and Emotional Convergence Associated With Stress Psychopathology. Front Integr Neurosci 2022, 16, 782154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisłowska-Stanek, A.; Kołosowska, K.; Maciejak, P. Neurobiological Basis of Increased Risk for Suicidal Behaviour. Cells 2021, 10, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lannoy, S.; Mars, B.; Heron, J.; Edwards, A.C. Suicidal Ideation during Adolescence: The Roles of Aggregate Genetic Liability for Suicide Attempts and Negative Life Events in the Past Year. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2022, 63, 1164–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, N.L.; Fiske, A. Genetic Influences on Suicide and Nonfatal Suicidal Behavior: Twin Study Findings. European Psychiatry 2010, 25, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, S.M.C.; Lepow, L.; Fennessy, B.; Iwata, N.; Ikeda, M.; Saito, T.; Terao, C.; Preuss, M.; Pathak, J.; Mann, J.J.; et al. Distinguishing Clinical and Genetic Risk Factors for Suicidal Ideation and Behavior in a Diverse Hospital Population. Transl Psychiatry 2025, 15, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, L.M.; Kuja-Halkola, R.; Rickert, M.E.; Class, Q.A.; Larsson, H.; Lichtenstein, P.; D’Onofrio, B.M. The Intergenerational Transmission of Suicidal Behavior: An Offspring of Siblings Study. Transl Psychiatry 2020, 10, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, D.A.; Melhem, N. Familial Transmission of Suicidal Behavior. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2008, 31, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carballo, J.J.; Llorente, C.; Kehrmann, L.; Flamarique, I.; Zuddas, A.; Purper-Ouakil, D.; Hoekstra, P.J.; Coghill, D.; Schulze, U.M.E.; Dittmann, R.W.; et al. Psychosocial Risk Factors for Suicidality in Children and Adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020, 29, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManama O’Brien, K.H.; Salas-Wright, C.P.; Vaughn, M.G.; LeCloux, M. Childhood Exposure to a Parental Suicide Attempt and Risk for Substance Use Disorders. Addict Behav 2015, 46, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Kalyoncu, A.; Bellon, A. Genetics of Suicide. Genes 2025, 16, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oquendo, M.A.; Sullivan, G.M.; Sudol, K.; Baca-Garcia, E.; Stanley, B.H.; Sublette, M.E.; Mann, J.J. Toward a Biosignature for Suicide. Am J Psychiatry 2014, 171, 1259–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Hu, X.-Z.; Janal, M.N.; Goldman, D. Interaction between Childhood Trauma and Serotonin Transporter Gene Variation in Suicide. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007, 32, 2046–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoltenberg, S.F.; Lehmann, M.K.; Anderson, C.; Nag, P.; Anagnopoulos, C. Serotonin Transporter (5-HTTLPR) Genotype and Childhood Trauma Are Associated with Individual Differences in Decision Making. Front. Genet. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, N.; Kang, J.; Campos, A.I.; Coleman, J.R.I.; Edwards, A.C.; Galfalvy, H.; Levey, D.F.; Lori, A.; Shabalin, A.; Starnawska, A.; et al. Dissecting the Shared Genetic Architecture of Suicide Attempt, Psychiatric Disorders, and Known Risk Factors. Biol Psychiatry 2022, 91, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadkowski, M.; Dennis, B.; Clayden, R.C.; ElSheikh, W.; Rangarajan, S.; DeJesus, J.; Samaan, Z. The Role of the Serotonergic System in Suicidal Behavior. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2013, 9, 1699–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.J.; Rizk, M.M. A Brain-Centric Model of Suicidal Behavior. Am J Psychiatry 2020, 177, 902–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, D.; Marín-Mayor, M.; Gasparyan, A.; García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Rubio, G.; Manzanares, J. Molecular Changes Associated with Suicide. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 16726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhou, G.; Xiao, Y.; Gu, J.; Chen, Q.; Xie, S.; Wu, J. Risk of Suicidal Behaviors and Antidepressant Exposure Among Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerberg, T.; Matthews, A.A.; Zhu, N.; Fazel, S.; Carrero, J.-J.; Chang, Z. Effect of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Treatment Following Diagnosis of Depression on Suicidal Behaviour Risk: A Target Trial Emulation. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023, 48, 1760–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagerberg, T.; Fazel, S.; Sjölander, A.; Hellner, C.; Lichtenstein, P.; Chang, Z. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Suicidal Behaviour: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 47, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschloo, L.; Hieronymus, F.; Lisinski, A.; Cuijpers, P.; Eriksson, E. The Complex Clinical Response to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Depression: A Network Perspective. Transl Psychiatry 2023, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, D.S.; Priefer, V.E.; Priefer, R. A Narrative Review: Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and the Risk of Suicidal Ideation in Adolescents. Adolescents 2025, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorka, S.M.; Manzler, C.A.; Jones, E.E.; Smith, R.J.; Bryan, C.J. Reward-Related Neural Dysfunction in Youth with a History of Suicidal Ideation: The Importance of Temporal Predictability. J Psychiatr Res 2023, 158, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Tikka, S.K.; Yadav, A.K.; Bhute, A.R.; Dhamija, P.; Bastia, B.K. Cerebrospinal Fluid Monoamine Metabolite Concentrations in Suicide Attempt: A Meta-Analysis. Asian J Psychiatr 2021, 62, 102711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoertel, N.; Cipel, H.; Blanco, C.; Oquendo, M.A.; Ellul, P.; Leaune, E.; Limosin, F.; Peyre, H.; Costemale-Lacoste, J.-F. Cerebrospinal Fluid Levels of Monoamines among Suicide Attempters: A Systematic Review and Random-Effects Meta-Analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2021, 136, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dombrovski, A.Y.; Szanto, K.; Clark, L.; Reynolds, C.F.; Siegle, G.J. Reward Signals, Attempted Suicide, and Impulsivity in Late-Life Depression. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.; Morici, J.F.; Zanoni, M.B.; Bekinschtein, P. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: A Key Molecule for Memory in the Healthy and the Pathological Brain. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Munteanu, O.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Enyedi, M.; Ciurea, A.V.; Tataru, C.P. From Synaptic Plasticity to Neurodegeneration: BDNF as a Transformative Target in Medicine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanos, P.; Gould, T.D. Mechanisms of Ketamine Action as an Antidepressant. Mol Psychiatry 2018, 23, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antos, Z.; Żukow, X.; Bursztynowicz, L.; Jakubów, P. Beyond NMDA Receptors: A Narrative Review of Ketamine’s Rapid and Multifaceted Mechanisms in Depression Treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 13658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardelli, I.; Serafini, G.; Cortese, N.; Fiaschè, F.; O’Connor, R.C.; Pompili, M. The Involvement of Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis in Suicide Risk. Brain Sci 2020, 10, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundin, L.; Erhardt, S.; Bryleva, E.Y.; Achtyes, E.D.; Postolache, T.T. The Role of Inflammation in Suicidal Behaviour. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2015, 132, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Xu, M.; Ye, M.; Yang, W.; Fang, M. Association between Serum Oxidative Stress Indicators, Inflammatory Indicators and Suicide Attempts in Adolescents with Major Depressive Disorder. Front Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1539158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaurasia, S.; Ganvir, R.; Pandey, R.K.; Singh, S.; Yadav, J.; Malik, R.; Choubal, S.; Arora, A. Gross Changes in Adrenal Glands in Suicidal and Sudden Death Cases: A Postmortem Study. Cureus 15 e51175. [CrossRef]

- Sporniak, B.; Szewczuk-Bogusławska, M. Do Cortisol Levels Play a Role in Suicidal Behaviors and Non-Suicidal Self-Injuries in Children and Adolescents?—A Narrative Review. Brain Sci 2025, 15, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genis-Mendoza, A.D.; Dionisio-García, D.M.; Gonzalez-Castro, T.B.; Tovilla-Zaráte, C.A.; Juárez-Rojop, I.E.; López-Narváez, M.L.; Castillo-Avila, R.G.; Nicolini, H. Increased Levels of Cortisol in Individuals With Suicide Attempt and Its Relation With the Number of Suicide Attempts and Depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melhem, N.M.; Munroe, S.; Marsland, A.; Gray, K.; Brent, D.; Porta, G.; Douaihy, A.; Laudenslager, M.L.; DiPietro, F.; Diler, R.; et al. Blunted HPA Axis Activity Prior to Suicide Attempt and Increased Inflammation in Attempters. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 77, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, J.P.; McKlveen, J.M.; Ghosal, S.; Kopp, B.; Wulsin, A.; Makinson, R.; Scheimann, J.; Myers, B. Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Stress Response. Compr Physiol 2016, 6, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braquehais, M.D.; Picouto, M.D.; Casas, M.; Sher, L. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Dysfunction as a Neurobiological Correlate of Emotion Dysregulation in Adolescent Suicide. World J Pediatr 2012, 8, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.B.; Thayer, J.F.; Vedhara, K. Stress and Health: A Review of Psychobiological Processes. Annu Rev Psychol 2021, 72, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowlati, Y.; Herrmann, N.; Swardfager, W.; Liu, H.; Sham, L.; Reim, E.K.; Lanctôt, K.L. A Meta-Analysis of Cytokines in Major Depression. Biol Psychiatry 2010, 67, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, G.N.; Ren, X.; Rizavi, H.S.; Zhang, H. Abnormal Gene Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokines and Their Receptors in the Lymphocytes of Bipolar Patients. Bipolar Disord 2015, 17, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Acunto, G.; Nageye, F.; Zhang, J.; Masi, G.; Cortese, S. Inflammatory Cytokines in Children and Adolescents with Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2019, 29, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Raison, C.L. The Role of Inflammation in Depression: From Evolutionary Imperative to Modern Treatment Target. Nat Rev Immunol 2016, 16, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaváková, M.; Ďuračková, Z.; Trebatická, J. Markers of Oxidative Stress and Neuroprogression in Depression Disorder. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015, 2015, 898393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Platas, S.G.; Cruceanu, C.; Chen, G.G.; Turecki, G.; Mechawar, N. Evidence for Increased Microglial Priming and Macrophage Recruitment in the Dorsal Anterior Cingulate White Matter of Depressed Suicides. Brain Behav Immun 2014, 42, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katrenčíková, B.; Vaváková, M.; Paduchová, Z.; Nagyová, Z.; Garaiova, I.; Muchová, J.; Ďuračková, Z.; Trebatická, J. Oxidative Stress Markers and Antioxidant Enzymes in Children and Adolescents with Depressive Disorder and Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Randomised Clinical Trial. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trebatická, J.; Vatrál, M.; Katrenčíková, B.; Muchová, J.; Ďuračková, Z. Current Insight into Biological Markers of Depressive Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Narrative Review. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebatická, J.; Hradečná, Z.; Surovcová, A.; Katrenčíková, B.; Gushina, I.; Waczulíková, I.; Sušienková, K.; Garaiova, I.; Šuba, J.; Ďuračková, Z. Omega-3 Fatty-Acids Modulate Symptoms of Depressive Disorder, Serum Levels of Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Omega-6/Omega-3 Ratio in Children. A Randomized, Double-Blind and Controlled Trial. Psychiatry Research 2020, 287, 112911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız Miniksar, D.; Göçmen, A.Y. Childhood Depression and Oxidative Stress. The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery 2022, 58, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, W.G.; Tintle, N.L.; Westra, J.; O’Keefe, E.L.; O’Keefe, J.H.; Harris, W.S. The Association between Plasma Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Suicidal Ideation/Self-Harm in the United Kingdom Biobank. Lipids Health Dis 2025, 24, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oravcova, H.; Katrencikova, B.; Garaiova, I.; Durackova, Z.; Trebaticka, J.; Jezova, D. Stress Hormones Cortisol and Aldosterone, and Selected Markers of Oxidative Stress in Response to Long-Term Supplementation with Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Adolescent Children with Depression. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundin, L.; Sellgren, C.M.; Lim, C.K.; Grit, J.; Pålsson, E.; Landén, M.; Samuelsson, M.; Lundgren, K.; Brundin, P.; Fuchs, D.; et al. An Enzyme in the Kynurenine Pathway That Governs Vulnerability to Suicidal Behavior by Regulating Excitotoxicity and Neuroinflammation. Transl Psychiatry 2016, 6, e865–e865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, A.S.; Vale, N. Tryptophan Metabolism in Depression: A Narrative Review with a Focus on Serotonin and Kynurenine Pathways. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 8493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, N.; Lei, M.; Chen, Y.; Tian, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, B. How Oxidative Stress Induces Depression? ASN Neuro 2023, 15, 17590914231181037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almulla, A.F.; Thipakorn, Y.; Vasupanrajit, A.; Abo Algon, A.A.; Tunvirachaisakul, C.; Hashim Aljanabi, A.A.; Oxenkrug, G.; Al-Hakeim, H.K.; Maes, M. The Tryptophan Catabolite or Kynurenine Pathway in Major Depressive and Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Behav Immun Health 2022, 26, 100537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilavská, L.; Morvová, M.; Muchová, J.; Paduchová, Z.; Garaiova, I.; Ďuračková, Z.; Šikurová, L.; Trebatická, J. The Kynurenine and Serotonin Pathway, Neopterin and Biopterin in Depressed Children and Adolescents: An Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids, and Association with Markers Related to Depressive Disorder. A Randomized, Blinded, Prospective Study. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1347178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widnall, E.; Epstein, S.; Polling, C.; Velupillai, S.; Jewell, A.; Dutta, R.; Simonoff, E.; Stewart, R.; Gilbert, R.; Ford, T.; et al. Autism Spectrum Disorders as a Risk Factor for Adolescent Self-Harm: A Retrospective Cohort Study of 113,286 Young People in the UK. BMC Medicine 2022, 20, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garas, P.; Takacs, Z.K.; Balázs, J. Longitudinal Suicide Risk in Children and Adolescents With Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Behav 2025, 15, e70618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, M.; Takahashi, M.; Mori, H. Positive Childhood Experiences Reduce Suicide Risk in Japanese Youth with ASD and ADHD Traits: A Population-Based Study. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.P.; Klimes-Dougan, B.; Croarkin, P.E.; Cullen, K.R. Understanding the Emergence of Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Adolescence from a Brain and Behavioral Developmental Perspective. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.A.Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, J.; Blond, B.N.; Wallace, A.; Liu, J.; Spencer, L.; Cox Lippard, E.T.; Purves, K.L.; Landeros-Weisenberger, A.; et al. Multimodal Neuroimaging of Frontolimbic Structure and Function Associated With Suicide Attempts in Adolescents and Young Adults With Bipolar Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2017, 174, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, R.; Long, Y.; Lv, F.; Zhou, X. Aberrant Frontolimbic Circuit in Female Depressed Adolescents with and without Suicidal Attempts: A Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jollant, F.; Wagner, G.; Richard-Devantoy, S.; Köhler, S.; Bär, K.-J.; Turecki, G.; Pereira, F. Neuroimaging-Informed Phenotypes of Suicidal Behavior: A Family History of Suicide and the Use of a Violent Suicidal Means. Transl Psychiatry 2018, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Heeringen, K.; Bijttebier, S.; Desmyter, S.; Vervaet, M.; Baeken, C. Is There a Neuroanatomical Basis of the Vulnerability to Suicidal Behavior? A Coordinate-Based Meta-Analysis of Structural and Functional MRI Studies. Front Hum Neurosci 2014, 8, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; De Asis-Cruz, J.; Limperopoulos, C. Brain Structural and Functional Outcomes in the Offspring of Women Experiencing Psychological Distress during Pregnancy. Mol Psychiatry 2024, 29, 2223–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolvi, S.; Merz, E.C.; Kataja, E.-L.; Parsons, C.E. Prenatal Stress and the Developing Brain: Postnatal Environments Promoting Resilience. Biol Psychiatry 2023, 93, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, C.; Sundquist, J.; Kendler, K.S.; Edwards, A.C.; Sundquist, K. Preterm Birth, Low Fetal Growth and Risk of Suicide in Adulthood: A National Cohort and Co-Sibling Study. Int J Epidemiol 2021, 50, 1604–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Ribas, P.; Govender, T.; Sundaram, R.; Perlis, R.H.; Gilman, S.E. Prenatal Origins of Suicide Mortality: A Prospective Cohort Study in the United States. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, V.; Gnazzo, M.; Rapelli, G.; Marchi, M.; Pingani, L.; Ferrari, S.; De Ronchi, D.; Varallo, G.; Starace, F.; Franceschini, C.; et al. Association between Sleep Disturbances and Suicidal Behavior in Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1341686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowin, J.L.; Stoddard, J.; Doykos, T.K.; Sammel, M.D.; Bernert, R.A. Sleep Disturbance and Subsequent Suicidal Behaviors in Preadolescence. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e2433734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolling, J.; Ligier, F.; Rabot, J.; Bourgin, P.; Reynaud, E.; Schroder, C.M. Sleep and Circadian Rhythms in Adolescents with Attempted Suicide. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 8354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]