1. Introduction

Despite the recent advancements in diagnosis and management of cardiovascular disease (CVD) through the use of high sensitivity biomarkers, microRNA detection and treatment targeting, as well as a decline in global age-standardized incidence, the global burden harbored by cardiovascular conditions remains the leading contributor to disability-adjusted life years (DALY) globally [

1]. Regardless of sociodemographic conditions, high blood pressure, high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and ambient particulate matter are the primary risk factors attributable to DALY for CVD in individuals older than 55 years old [

2]. Multiple satellite conditions, along with genetic and behavioral risk factors, interact synergistically to contribute to the advancement of cardiovascular disease. Often downplayed as a risk factor for the development of cerebrovascular disease or ischemic heart disease, atherosclerosis has been recently regarded as an early form of cardiovascular disorder by itself [

3]. Atherosclerosis is a systemic progressive vascular disorder driven by a low-grade chronic inflammation (LGCI), leading to accumulation of fatty fibrous material in the intimal layer of small and medium arteries, mainly as a consequence of hyperlipidemia and lipid oxidation. This process is accelerated by an inflammatory response that involves the migration and proliferation of various immune cell types, essential for the advancement of atherosclerotic plaques – neutrophils, T lymphocytes and macrophages [

4]. Obesity is closely associated with development and progression of atherosclerosis through a plethora of mechanisms, notably LGCI, insulin resistance, adipokine imbalance and adipocyte-derived exosome signaling [

5,

6].

Sedentary lifestyles and changes in the composition of food and beverages have given rise to a new epidemic in the 21st century: obesity. The development of obesity is multifactorial, and the contributing factors (behavioral, lifestyle, genetics, social, economic, and political factors) vary among individuals [

7]. A major global health problem, especially in Western society, obesity is defined by the WHO as a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 30 kg/m

2, confirmed by at least one anthropometric criterion (waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, or waist-to-height ratio) in most scenarios [

8]. Waist circumference, a reliable indicator of abdominal obesity (reference cutoff values for European populations: greater than 80 cm in women and 94 cm in men) and visceral fat accumulation are independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease which have been associated with higher mortality and morbidity rates [

7,

9].

The complex remodeling of adipose tissue found in obese patients translates into an altered secretion of adiponectin, leptin, and resistin, along with proinflammatory cytokines leading to LGCI, deeming adipose tissue an endocrine organ [

10,

11,

12]. A tight balance of these hormones is involved in maintenance of cardiovascular homeostasis, inflammatory activity, insulin sensitivity, and adipose tissue balance. Adiponectin, on one hand, protects against insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, on the other hand it enhances adipose tissue deposition, reduces thermogenesis, and is directly correlated with extent of inflammation [

10]. Resistin levels serve as prognostic biomarkers for heart failure severity and mortality, while leptin levels are positively associated with increased risk for heart failure [

12,

13]. In obese individuals, the disruption of adipokine regulation stands at the foundation for endothelial dysfunction [

14].

Obesity overrides the physiological anti-inflammatory milieu promoted by immune cells found in adipose tissue and those migrated in atheromatous plaques. Enhanced activation of ”first responders” – neutrophils – and increased migration of macrophages in the atheromatous plaques lead to upregulation of Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumoral Necrosis Factor – alpha (TNF-α). Along with excessive circulating levels of fatty acids, these trigger a self-sustaining permanent state of inflammation [

15]. Compounding the high atherogenic and thrombotic risk, obese patients demonstrate increased thrombocyte count and platelet activity, as shown by the high concentrations of P-selectin and platelet-derived microparticles [

16].

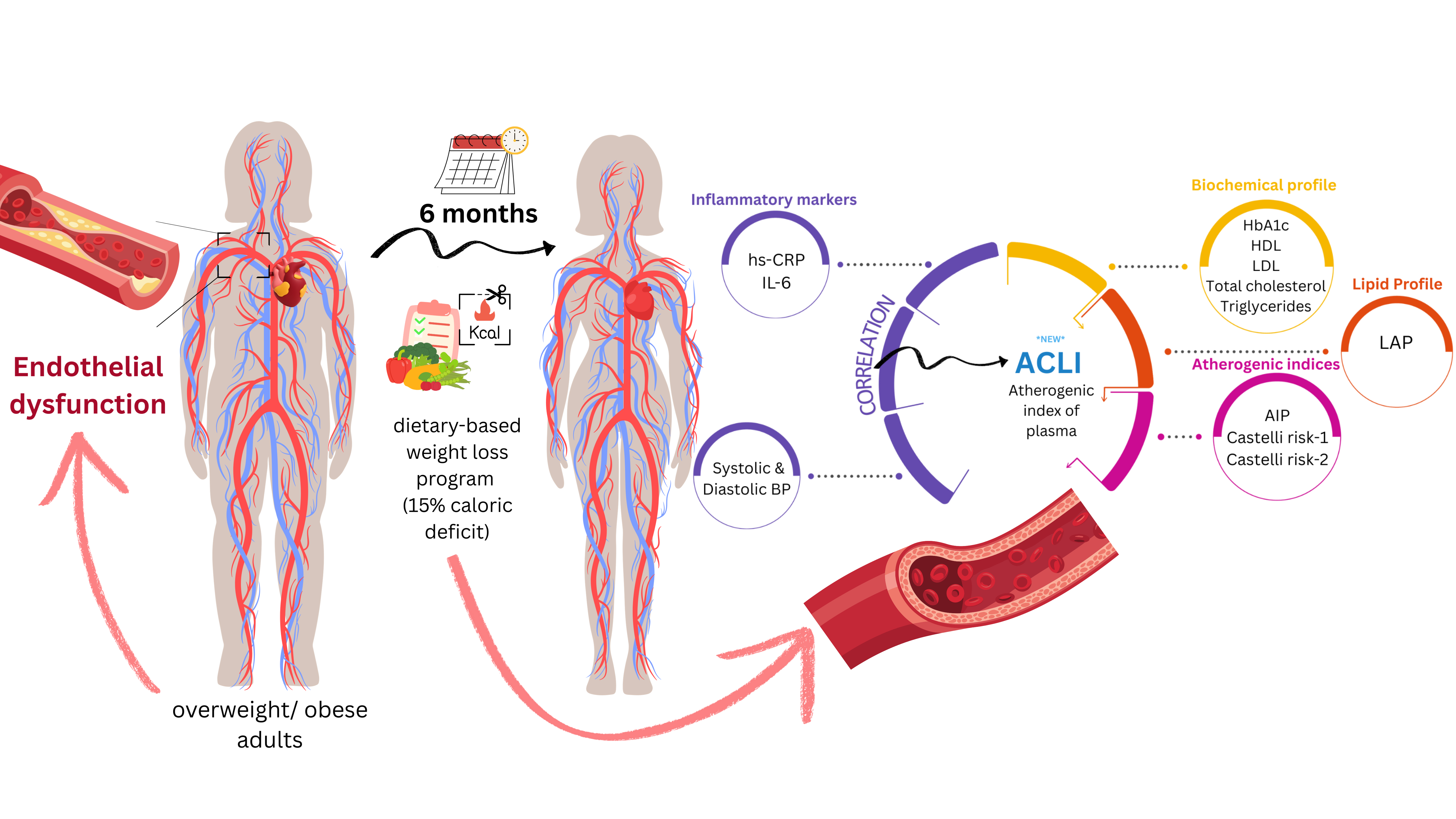

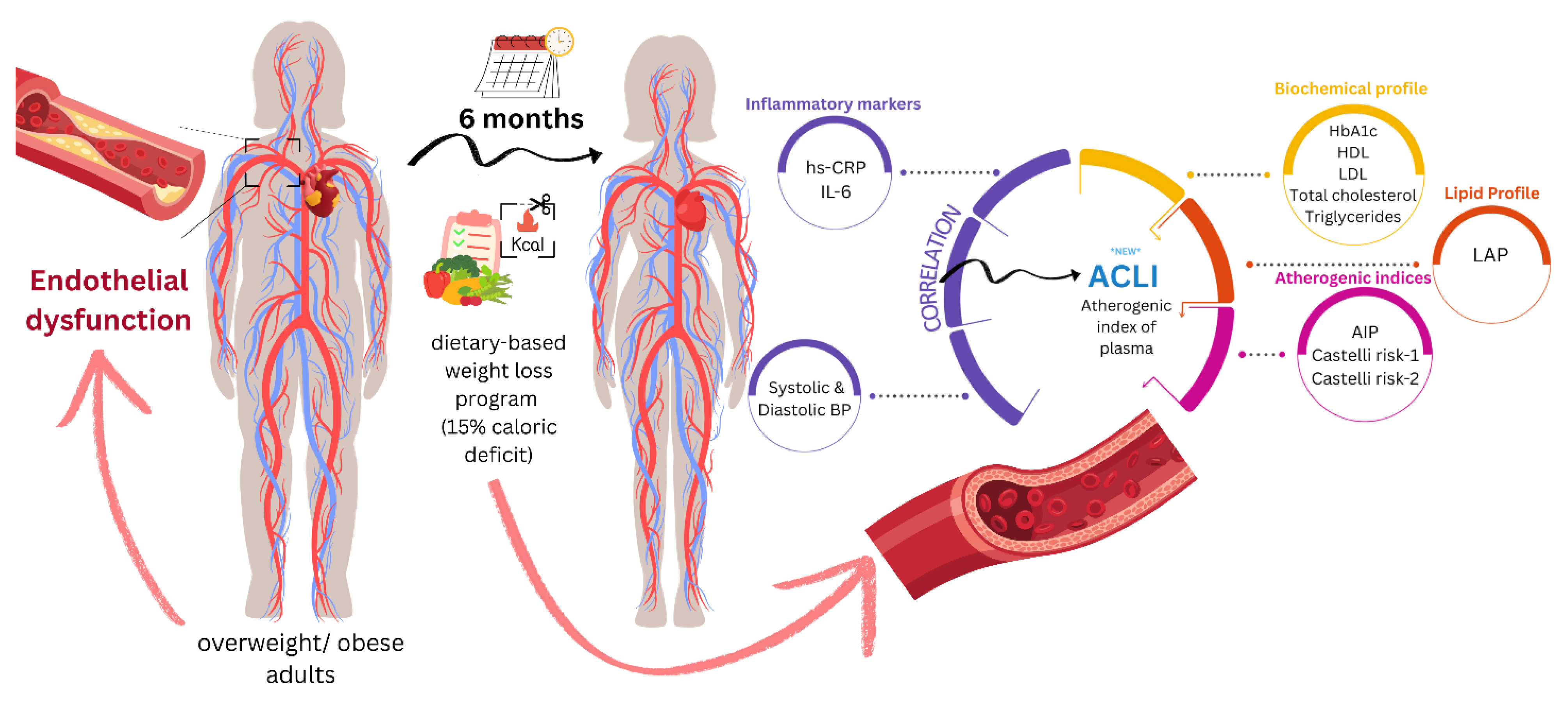

Given the intricate involvement of obesity on development and progression of endothelial dysfunction, we sought to understand the effect of mild dietary weight loss on several derived indexes previously associated with progression of atherosclerosis, the most prevalent form of early CVD in obese individuals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a prospective study involving apparently healthy adults who voluntarily presented themselves to a private clinical practice during the beginning of 2024, aiming to lose body weight by dietary intervention alone. Patients were subjected to a clinical examination by the main investigator (C.L.), had a thorough check of their complete medical history, and had blood samples taken for a number of biochemical parameters listed below. Patient identification data was coded alpha-numerically. Blood results were interpreted independently by a second investigator (M.A.M.), and the patients who fit inclusion criteria were called for a second visit within 7 days to present them with the study protocol. Following informed consent, all subjects were assessed for intervention and invited for monthly physical follow-up visits. Blood samples were taken every two months (totaling four sets). At any moment a patient could be withdrawn from the study if any of the following applied: safety concerns in laboratory findings, new medical diagnosis overlapping with the exclusion criteria, deviations from protocol and patient request to exit the study.

2.2. Timeframe

Patient recruitment extended over a period of 6 months, from 3rd of January 2024 to 1st of July 2024. Patient follow-up period was fixed at 6 months, regardless of enrollment date. The study officially ended at 30th of December 2024.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Enrollment

We included adults aged between 18 and 65 years old with an excess ponderal status (established by BMI and at least one other anthropometric measurement) who presented voluntarily to a private clinical practice. Exclusion criteria: stable residence outside a 50 kilometers radius from the city, lack of motivation, current medical therapy interfering with weight loss, serious physical impairments (walking with aid, requirement of permanent assistance), significant medical history (history of cerebrovascular ischemic disease, coronary artery disease, heart failure stage III-IV NYHA, pulmonary hypertension, any mild- moderate- or severe valvular disease, history of peripheral artery disease, trauma leading to severe motor deficits, any severe musculoskeletal condition which could interfere with walking ability, documented chronic kidney disease stage IIIa or higher, history of chronic liver disease, moderate or severe pulmonary disease, or insufficiently controlled mild pulmonary disease, diabetes of any type, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living score less than 8, recent or ongoing psychiatric treatment, recent or currently suffering from any oncological disease), high clinical suspicion of sarcopenia (gait speed less than 0.9 meters/second, handgrip strength less than 25 kilograms in men, and 18 kilograms in women), abnormalities in the physical examination (signs of active infectious disease, fever during last 48 hours, pain of one major joint, or at least three minor joints, chest pain regardless of characteristics, breathing difficulties after 5 attempts in the chair-sit-to-stand test), abnormalities in the blood screening panel (fasting plasma glycemia over 100 mg/dl, glycated hemoglobin over 5.7%, estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, white blood cells over 10.000/µl, hemoglobinemia lower than 12 g/dl in women and 14 g/dl in men, platelet count lower than 150.000/mm3).

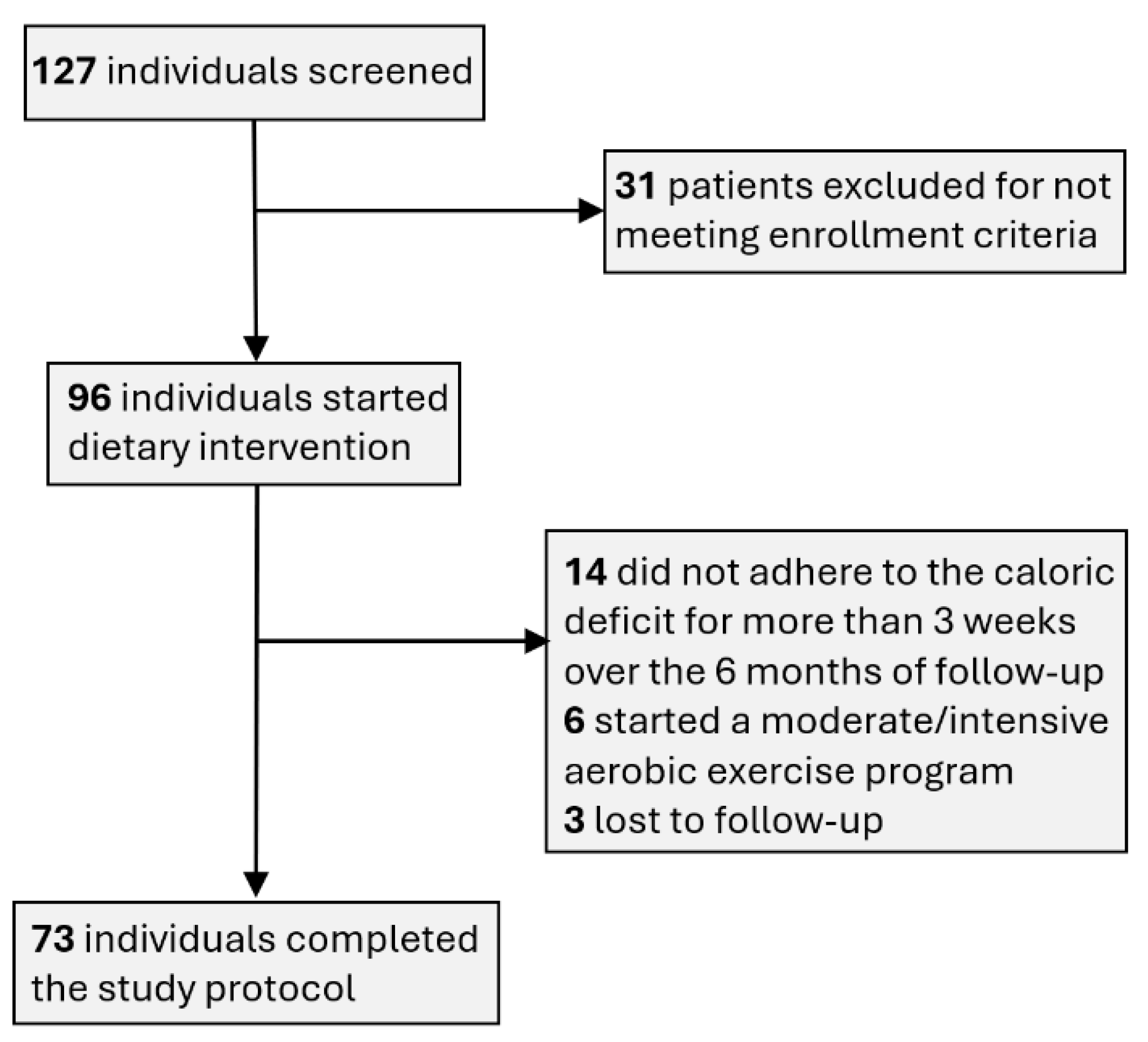

A modest proportion of the subjects enrolled were withdrawn over the course of the study, reasons being patient safety, acquirement of serious medical condition, deviation from intended intervention and patient`s request. As shown in

Figure 1, 6 patients actively pursued moderate- to intensive aerobic physical activity regimens, which contradicts with our dietary weight loss intervention; 14 patients did not stick to the required 15% intake deficit during more than 3 weeks over the course of the study; 3 patients were lost to follow-up. There were no cases of safety concerns flagged during periodic physical examinations or by the blood panel interpretation.

2.4. Intervention

The study did not involve any pharmacological interventions and did not interfere with any of the ongoing prescribed medications. The recommended physical activity was 8000-10000 steps daily, at a slow-moderate pace, without any intense aerobic efforts. Maintenance calories were estimated at enrollment, using the Mifflin St Jeor equation (men: basal metabolic rate = (10 × weight in kg) + (6.25 × height in cm) - (5 × age in years) + 5; women: basal metabolic rate = (10 × weight in kg) + (6.25 × height in cm) - (5 × age in years) – 161), standard activity factor taking values of either 1.2 (in sedentary individuals) or 1.375 (in those reporting some exercise weekly). To achieve a caloric intake reduction of 15% / day, the participants were advised to record either the ingredient composition of the in-house prepared food by using a kitchen scale, or track the calories listed in every already-cooked meal. General dietary advice was given in printed form to all participants, advising manageable methods to decrease overall calorie intake (e.g., restricting consumption of processed, fat-rich foods, calorie-dense low-filling meals), to increase their protein intake to 1g/per kg body weight, as well as their dietary fiber consumption, and to consume at least 2000 ml of water daily. Compliance with the dietary intervention was reviewed every 7-10 days using patients` daily food diary and weekly weight journal. Concerning physical activity, all patients were advised to achieve between 8000 – 10000 steps per day, their weekly records being transmitted to the principal investigator at the same moment as the calorie intake journal. This was considered a negligible component for weight loss in the context of the 15% calorie deficit ensued.

2.5. Anthropometric and Biochemical Parameters Recorded

After pseudonymization of the patient identification data, we recorded a set of anthropometric measurements: age, biological gender, weight, waist circumference, and daily activity level. The biochemical parameters recorded at enrollment and study completion: hemoleucogram (along with derived erythrocyte parameters, leucocyte formula), lipid profile (total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C), triglycerides), glycemic profile (fasting plasma glucose, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c)), liver function panel (aspartate aminotransferase AST, alanine aminotransferase ALT, gamma glutamyl transferase GGT, bilirubin levels), renal function (urea, creatinine).

The inflammatory markers high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and lactate dehydrogenase LDH were also recorded. The two blood panels at 2 and 4 months after enrollment were comprised of hemoleucogram, glycemic profile, liver and renal function tests. Of all these variables, only the most relevant ones are presented in this study to highlight the research conclusions.

2.6. Planned Outcomes

Derived indices associated with atherosclerosis progression were calculated: Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP), Castelli Risk Indexes – 1 (CRI-1) and Castelli Risk Indexes – 2 (CRI-2), and Lipid Accumulation Product (LAP), using the standard formulas

:

To assess the effect of weight loss on the atherogenic profile of patients, we proposed an atherogenic load index (Atherogenic Central Load Index (ACLI)). The proposed index considers several important benchmarks: its value should increase when the profile becomes highly atherogenic (large waist, high triglycerides, low HDL) and should not be influenced by extreme triglyceride values.

The proposed formula for ACLI is:

This ensures coherence from a pathophysiological point of view, and logarithmic transformation of the ratio was applied to ensure robustness of the formula to extreme values. In other words, the formula has a reduced sensitivity to outlier values.

At the same time, the proposed formula applies a normalization of the index by referring to the protective component of HDL values that is found in the AIP formula. To quantify the change induced by the intervention in absolute values, we calculated Δ ACLI = ACLIPOST – ACLIPRE. To validate the new index, we evaluated the pre-post intervention change and performed its correlation analysis with the traditional indices: AIP, CRI – 1 and CRI – 2. We also tested the correlation of the new index with the values of the inflammatory markers hs-CRP and IL – 6.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis of data was performed using SPSS v.29.0 (IBM Ireland Product Distribution Limited, IBM House, Shelbourne Road, Ballsbridge, Dublin 4, Ireland) and the STATA 16 software (StataCorp LLC, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, Texas 77845-4512, USA). The qualitative variables were presented as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies. Descriptive statistics include absolute numbers, percentages, mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR), in accordance with the variable type and distribution symmetry. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify whether the distribution of continuous variables was normal. The t-test for Dependent Samples or Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Test were applied to compare continuous variables, depending on the type of distribution of each. To highlight the predictive value of the atherogenic profile based on the new proposed index (ACLI) compared to the traditional indices, Pearson correlation tests were performed and the correlation coefficients (r) and the slopes of the regression lines were compared according to the regression line equation.

The accuracy of the predictive power was comparatively evaluated based on the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, taking into account the area under the curve (AUC) which represented the compromise between the sensitivity (Se) and specificity (Sp) of the method used. The significance level calculated in utilized tests (p-value) was considered significant for the values of p<0.05.

2.8. Ethical Approval

Upon study enrollment, all patients gave their informed consent allowing limited use of their anthropometric and laboratory findings data, in agreement with Declaration of Helsinki and local ethical regulations. Ethical approval was received from Grigore T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Iasi, Romania, the Scientific Research Committee (345/07.09.2023). The Public Health Directorate of Iasi, in accordance with national regulations, waived the need for ethical approval due to the design of the study.

2.9. Sample Size Calculation

To determine the optimal sample size, we calculated the minimum volume required to ensure the representativeness of the patient category and used relevant data from the literature [

17,

18]. To achieve this prerequisite, we established a 95% confidence interval.

Accordingly, we used the equation: with for a 95% confidence interval and an allowed error of 2% (d = 0.02). For a standard deviation (σ) of 8.59% for weight loss, the minimum sample size should be 71 cases (n calculating ≥ 70.87).

Thus, in this research, from the total number of patients (127 patients) and applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a study group with 73 cases resulted.

3. Results

Out of the 73 patients who managed to complete the intervention protocol, at the enrollment phase 12 (16.4%) were overweight and 61 (83.6%) were obese. Looking at the number of cases in each patient group (overweight, obese) it was revealed that after 6 months, 10 out of the 12 overweight patients (83.3%) and 45 out of the 61 obese patients (73.8%) remained in the same anthropometric category. Only 2 initially overweight patients (16.7%) and 1 obese patient (1.7%) advanced to the normal category (BMI and WC). 15 out of the initial 61 obese individuals advanced in the overweight category (24.6%). These changes are presented in

Figure 2, which presents the relative frequencies reported to the total number of patients included in the study (73 patients).

The 73 individuals lost a median of 11.8 kg over the study period (IQR: 8 – 19 kg). 25 subjects (34.2%) lost less than 10% of their starting body weight, the cutoff value agreed for efficiency of the intervention. A summary of anthropometric and biochemical characteristics of interest at the two points is depicted in

Table 1. Evaluation of the results indicated that the only parameter that did not change significantly post-intervention was CRI–1 (p = 0.054).

ROC for AIP as prognostic factor for obesity returned a statistically significant value (AUC = 0.710, 95%CI: 0.567 to 0.854), with a cutoff value for best accuracy at 0.30. This relationship did not extend beyond the enrollment time point. LAP was an accurate prognostic factor for discerning obese vs overweight individuals in both the sample at initiation (AUC = 0.883, 95%CI: 0.800 to 0.965, and exit (AUC = 0.857, 95%CI: 0.771 to 0.943).

The dietary weight loss intervention led to a statistically significant difference in three out of the five main outcomes recorded: AIP, CRI-1, CRI-2, LAP and ACLI (

Table 2). While AIP showed improvement (i.e., lower values) following intervention, the difference did not attain statistical significance, the results indicating a statistical uncertainty (p = 0.046). CRI–1 showed virtually no difference between the two time slots (

Table 1).

In this context, the research aims to validate an index, called Atherogenic Central Load Index (ACLI) as a new lipid biomarker that comprehensively evaluates the balance between atherogenic and antiatherogenic particles in the blood to effectively reflect the cumulative atherogenic effect and its association with inflammatory markers. To highlight the value of the new index, we evaluated the pre-post intervention change and performed its correlation analysis with the traditional AIP, CRI–1 and CRI–2 indices. We also tested the correlation of the new index with the values of the inflammatory markers hs-CRP and IL–6.

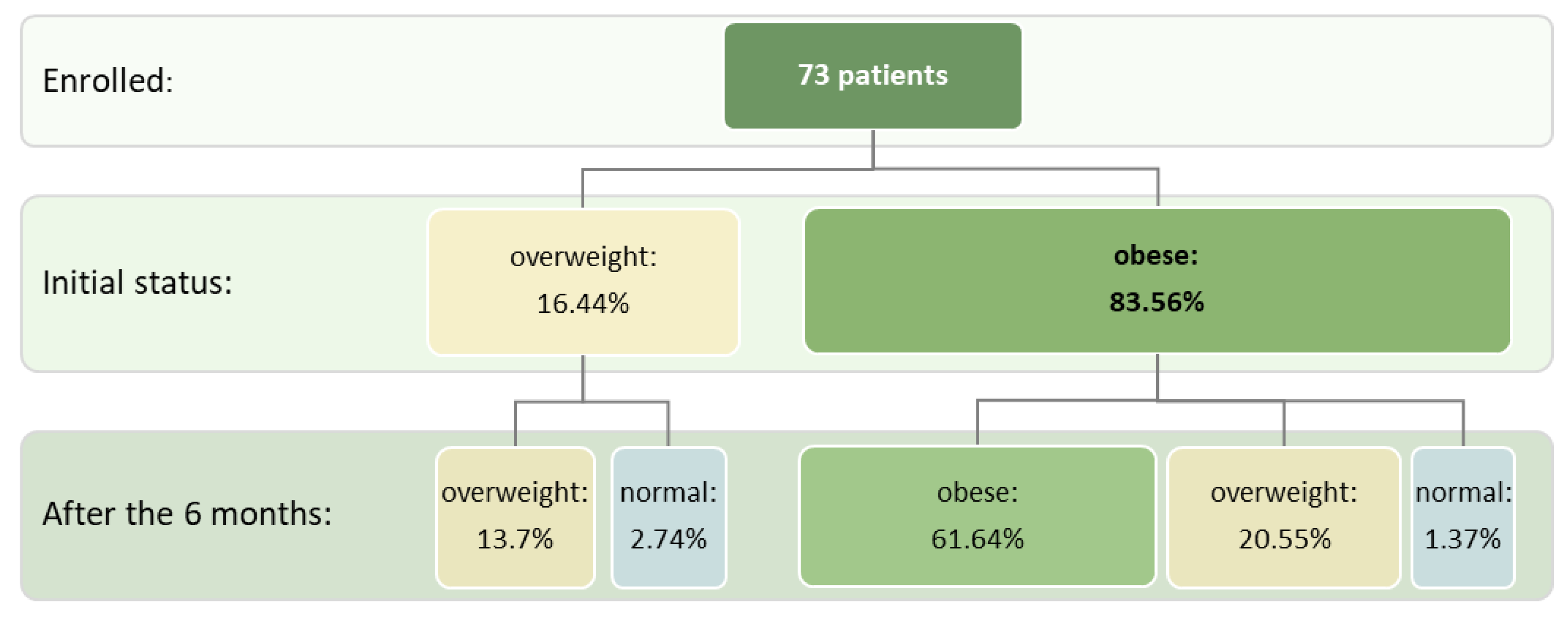

To validate the new index, we evaluated the pre-post intervention change in ACLI values (Δ ACLI) and performed a correlation analysis of the differences recorded in the evolution with the changes in Δ AIP, Δ CRI – 1 and Δ CRI – 2 (

Figure 3). A significant increase in Δ ACLI was noted with the changes in the values of the traditional atherogenic indices: Δ AIP (r=0.81, p<0.001), Δ CRI-1 (r = 0.73, p<0.001) and Δ CRI-2 (r = 0.63, p < 0.001) (

Figure 3).

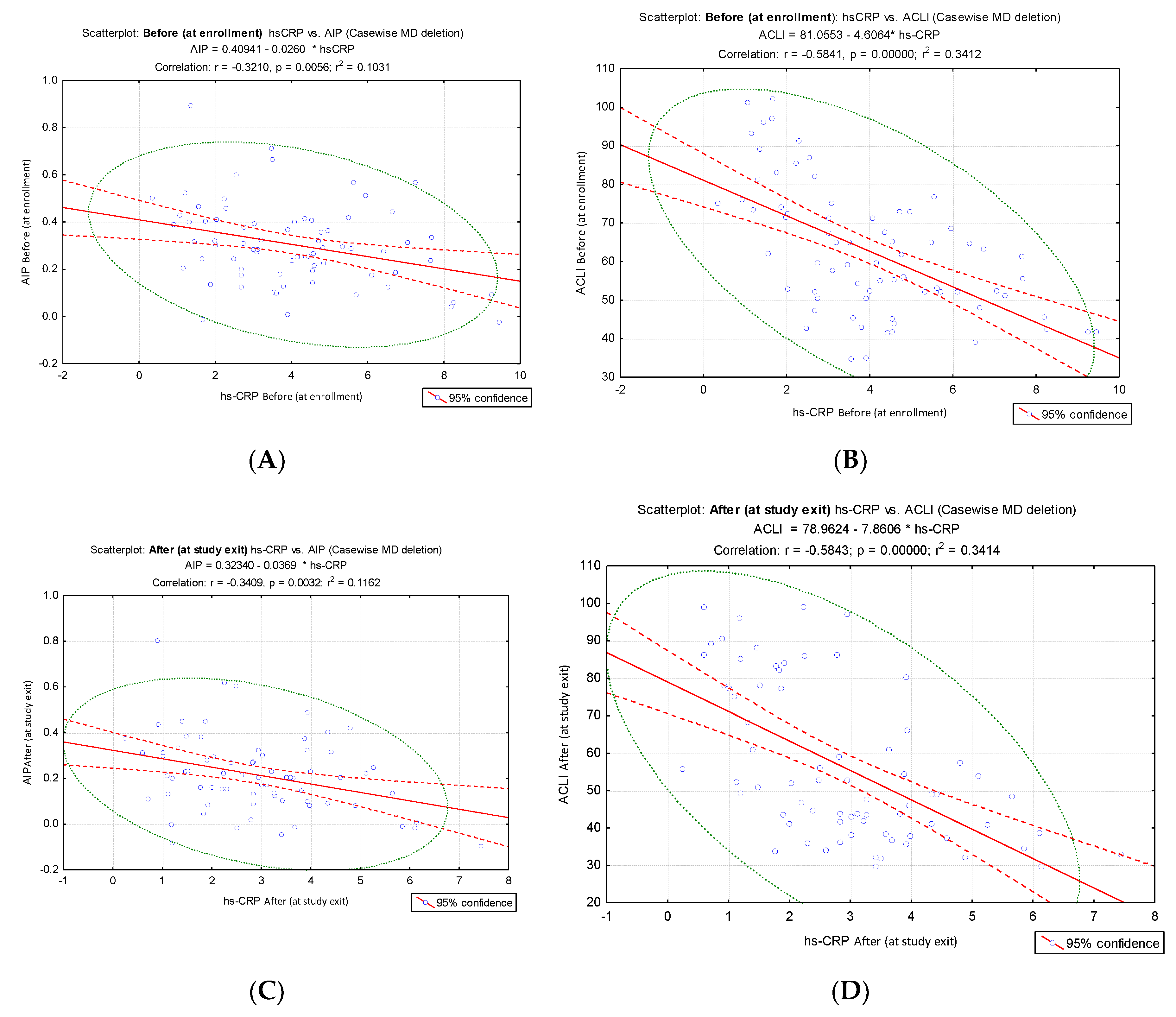

Given that endothelial dysfunction is characterized by pro-inflammatory status, decreased vasodilation, and increased vasoconstriction, the study demonstrated a significant correlation of the proposed index (ACLI) with the inflammatory markers hs-CRP and IL-6. To allow a comparison of the intensity of the link between ACLI and AIP and the inflammatory markers hs-CRP and IL-6, we analyzed the results of the correlation tests. We compared the correlation coefficients and the slopes of the corresponding regression lines. The results indicated a stronger inverse correlation of hs-CRP values with ACLI values (before: hs-CRP vs ACLI, r = - 0.58, p < 0.001,

Figure 4B; after: hs-CRP VS ACLI, r = - 0.58, p < 0.001,

Figure 4D) compared to the results of the correlation of hs-CRP vs. AIP (before: hs-CRP vs. AIP, r = - 0.32. p = 0.0056,

Figure 4A; after: hs-CRP vs. AIP, r = - 0.34, p = 0.0032,

Figure 4C).

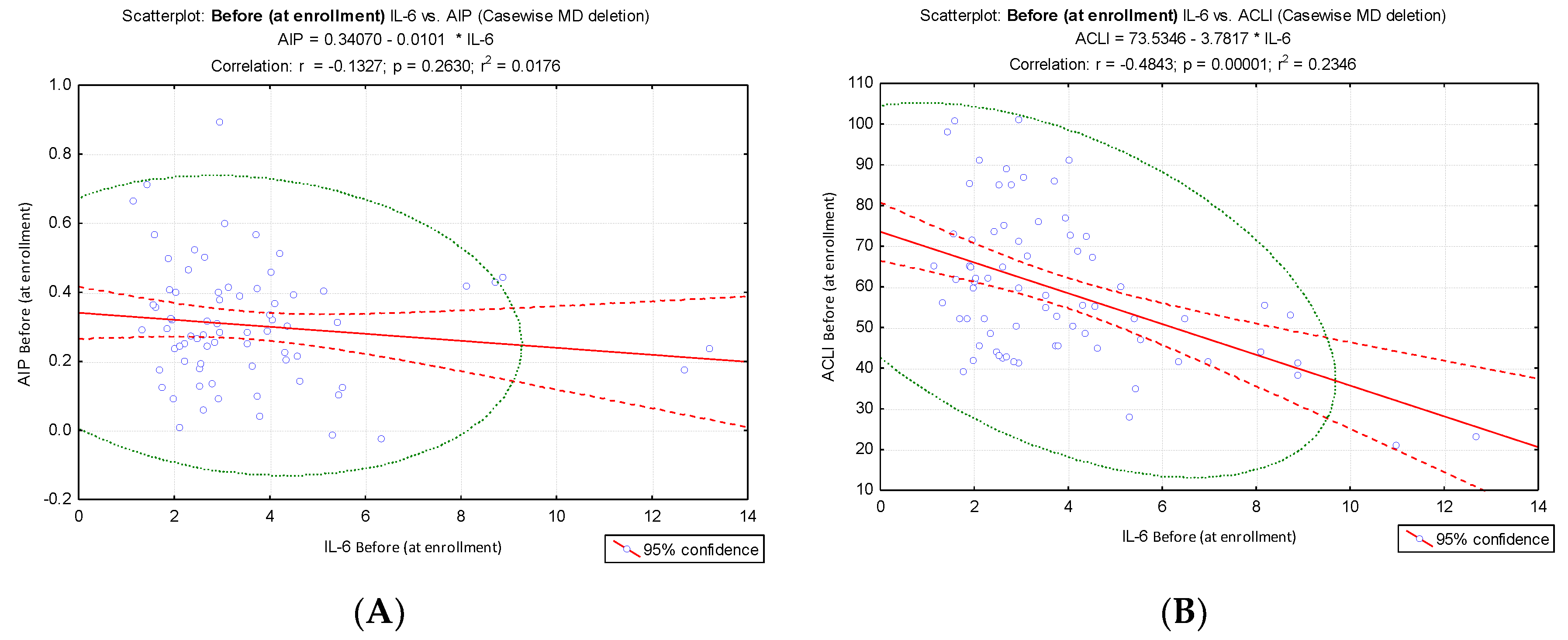

Different results were obtained when IL-6 values were correlated with AIP and ACLI values at the two evaluation times: before: IL-6 vs ACLI, r = - 0.48, p < 0.001,

Figure 5B; after: IL-6 vs ACLI, r = - 0.59, p < 0.001,

Figure 5D) compared to the results of the IL-6 vs. AIP correlation (before: IL-6 vs. AIP, r = ⁻ 0.13. p = 0.263,

Figure 5A; after: IL-6 vs AIP, r = ⁻0.17, p = 0.149,

Figure 5C). IL-6 values at the time of enrollment and at the end of the intervention did not show a significant correlation with AIP, but they showed a significant inverse correlation with ACLI.

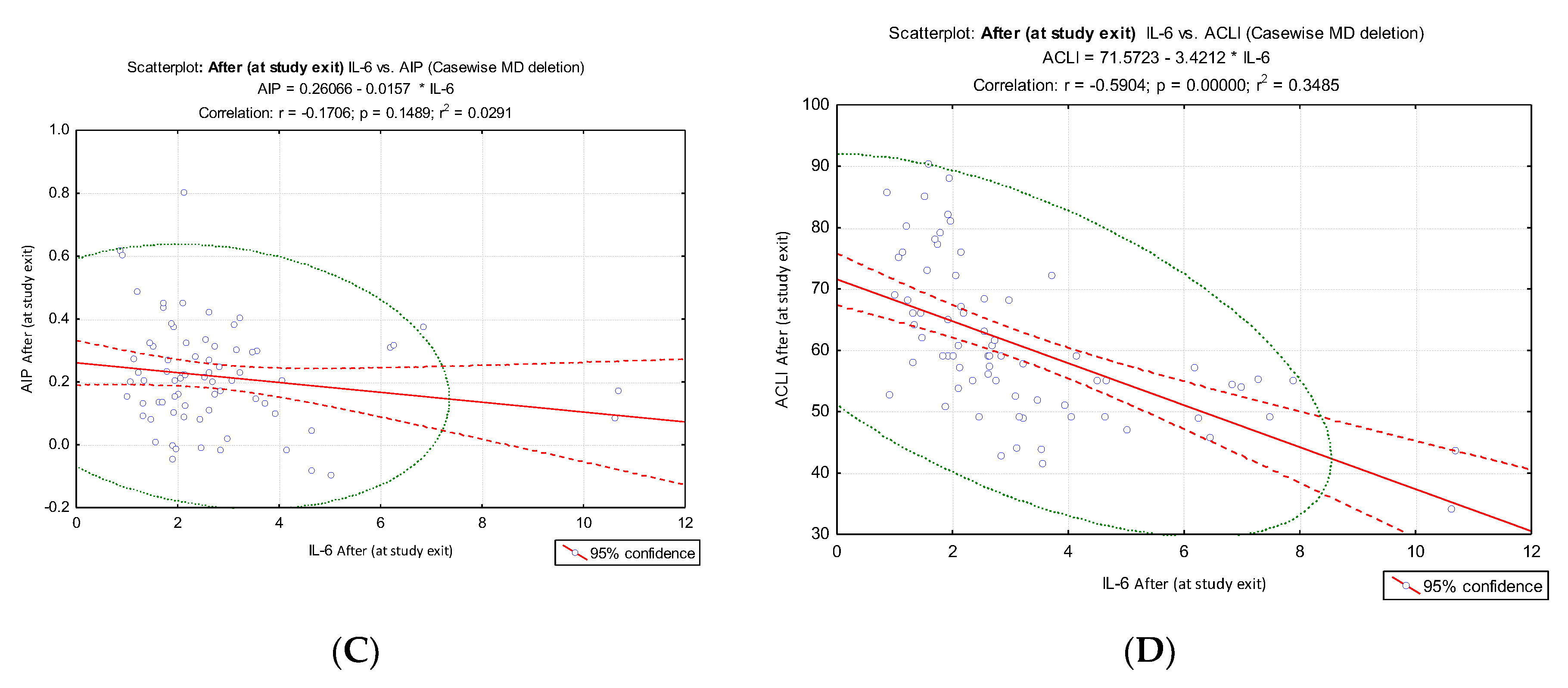

The results obtained provide a clear conclusion on the increased predictive value that the new index (ACLI) has for the inflammatory markers hs-CRP and IL-6. To comparatively evaluate the accuracy that the atherogenic indices (AIP, CRI-1, CRI-2 and ACLI) have in predicting inflammatory markers, we analyzed the ROC curves (

Figure 6) and AUC values (

Table 3).

The evaluation of the obtained AUC values allowed to clearly highlight the superior discrimination performance of ACLI regarding the inflammatory markers hs-CRP and IL⁻6 in obese or overweight patients involved in dietary interventions for weight loss. The AUC values for ACLI were significantly higher than those corresponding to the other atherogenic indices evaluated (AIP, CRI-1 and CRI-2) for both evaluation times (before intervention and after intervention.

All our results highlighted the superior potential of ACLI for predicting endothelial dysfunction with reference to the inflammatory markers hs-CRP and IL-6, compared to traditional derived indices associated with atherosclerosis progression (AIP, CRI-1 and CRI-2).

4. Discussion

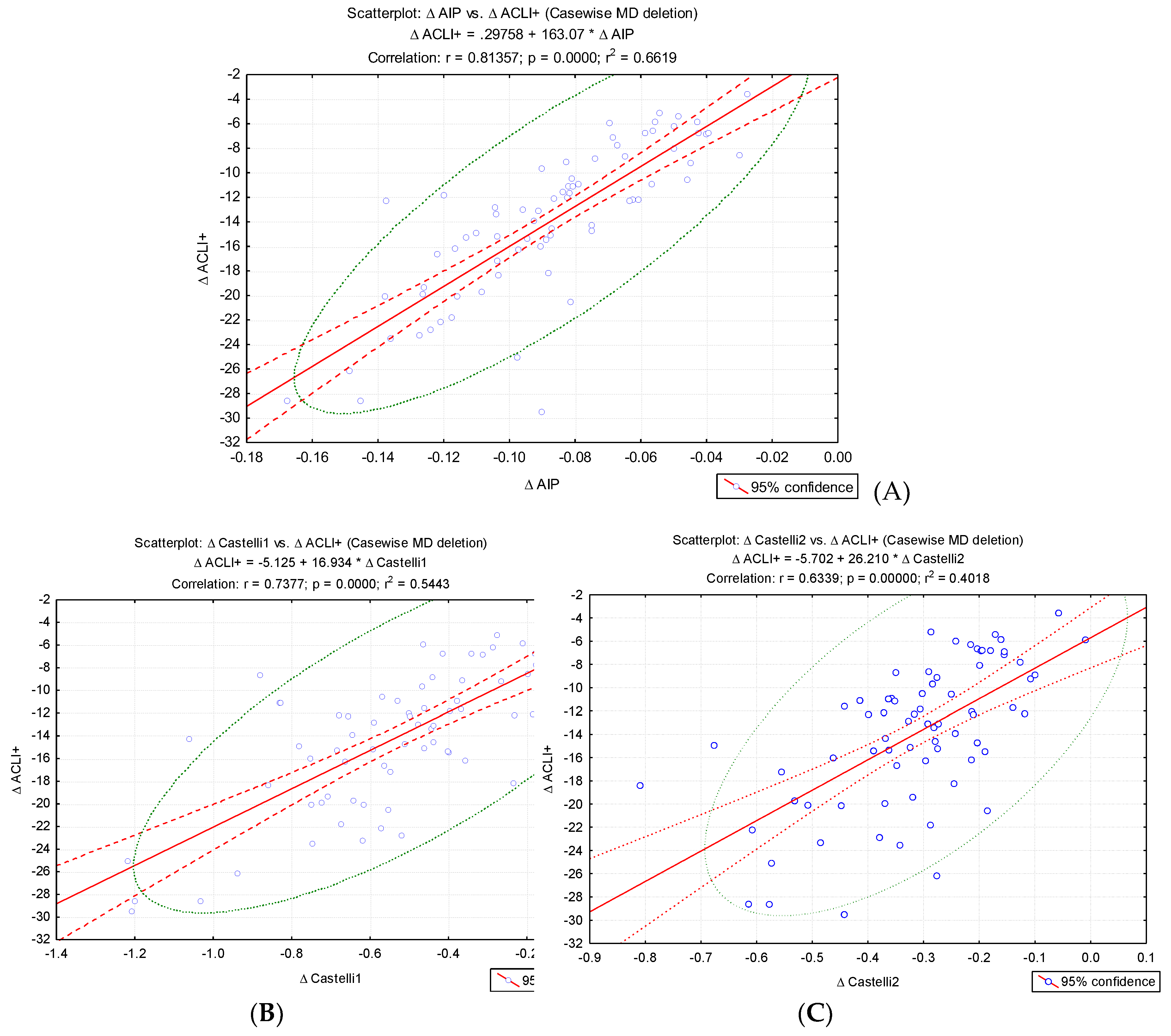

For an index to be of interest to our research, it should be associated with progression of atherosclerosis, an early form of CVD regularly encountered in overweight or obese patients. Literature is abundant in indicators for predicting progression of CVD or mortality, ranging from multiplication of laboratory values and/or anthropometric measures, lab findings alone, to ratio type indicators. Product-type derived indicators, where all component parameters are expected to shift in the same direction, would not require additional proof of evidence through our research. Therefore, we included the AIP, CRI–1 and CRI–2 ratio-type indexes. LAP was added to the outcomes, despite the product-type formula, to find which confounding factors might influence the change in LAP throughout the diet-based weight loss intervention. In line with the ratio-type indexes, and inspired by LAP, we included a Atherogenic Central Load Index (ACLI), where we kept the same waist correction. A graphical summary of the research objectives is presented in

Figure 9.

4.1. Atherogenic Index of Plasma

The atherogenic index of plasma, with the classical formula AIP = log10(TGL/HDL-C), proved a statistically significant predictor ability for excess weight status at enrollment when comparing overweight to obese people. While no clear normal range has been defined, AIP values under 0.11 are considered to yield lower risk for cardiovascular disease [

19]. In our study, less than 5% of patients both in the initial and final settings achieved this lower threshold. AIP did not prove a relevant association to absolute values for BMI or body weight but was directly correlated to triglyceride levels and inversely to HDL-C at enrollment. These findings are in line with existing literature in both general and selected populations, studies reporting a better prognostic capacity of AIP for excess body weight in comparison to other simple laboratory lipid values [

20,

21]. In larger adult populational samples, AIP has proven a statistically significant direct correlation with BMI and complementary anthropometric measurements such as waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio [

22,

23]. Stratifying for AIP values, HDL-C and TGL showed opposing trends, highest quartile values of AIP returning lower HDL-C and higher TGL values and vice-versa [

21,

22].

In our study, the intervention of dietary weight loss did not return a statistically significant difference for AIP values, neither for the entire population sample, nor for subgroups generated by percentage of weight lost, by gender stratification, or by change in category. These findings align with existing literature, in the manner that an efficient weight drop does not necessarily translate into an improvement of AIP [

24]. A more performant variant of AIP restricted to only the most anti-atherogenic fractions of HDL-C has been proposed to the scientific community, but the interest in it is still behind most modified indices (AIP-WC, AIP-Waist-to-Height-ratio, AIP-BMI). Other studies, however, indicate that a reduction in AIP parallels the improvement in body weight as shown in diabetic patients after bariatric surgery or after treatment with a bergamot polyphenol extract complex, the method employed for weight drop being of lesser importance [

25,

26].

The importance of this index stems from its widespread associations in general population cohorts with progression of cardiovascular disease (incidence of heart failure, progression of atherosclerotic coronary disease) and incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events and cardiovascular death [

27,

28,

29]. Not only the individuals with alleged coronary artery disease (as evidenced by angiography) demonstrate association between elevated AIP and increased incidence of cardiovascular events, but also patients suffering from microvascular disease, as in type 2 diabetes mellitus or cardio-vascular-kidney metabolic syndrome [

30,

31]. Evidence suggests that lower values of AIP in the general population correlate with a reduced risk for major adverse cardiovascular events, after adjustment for traditional CVD risk factors [

32]. Our selected study population is a close approximation for the typical individual fit for a weight loss intervention. Most of the individuals finishing the study remained in the same body weight category, but within each BMI category there was a clinically significant reduction in the average values of AIP. This highlights the potential benefit of an even minor reduction of excess body weight with respect to the risk for cardiovascular disease.

AIP appears to be a better prognostic factor for insidious atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the general population, compared to other lipid-based composite indices [

33]. In addition, evaluation of AIP at hospital admission for acute myocardial infarction is an accurate predictor for all-cause mortality over one-year follow-up [

34]. Presumably, the connecting link between high AIP values and increased risk of CVD is represented by traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as obesity, elevated blood pressure, elevated fasting plasma glucose, and oxidative stress, but proof is yet heterogeneous [

22,

23,

35,

36].

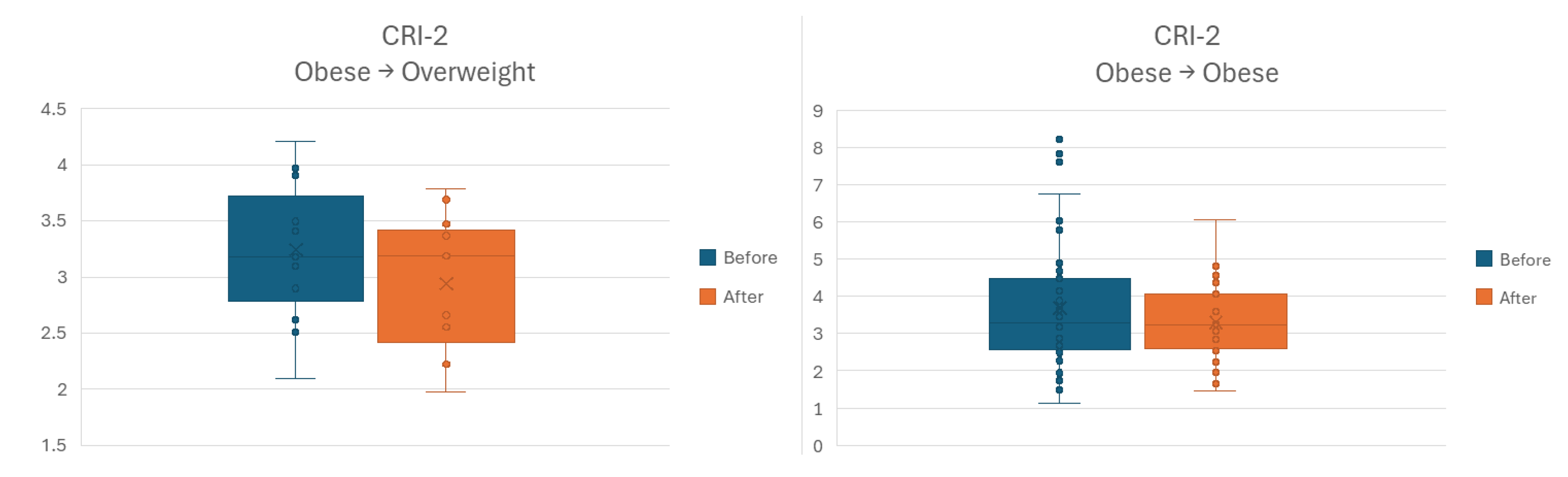

4.2. Castelli Risk Index – 1 and – 2

We used the common formula CRI–1 = TC/HDL-C for Castelli Risk Index – 1 and CRI -2 = LDL-C/HDL-C for Castelli Risk Index – 2. Within the whole sample, the difference between the overweight and obese subgroups was not statistically significant at either enrollment or study completion for both indices. Comparison of the before and after intervention values returns lower values for both indices after the weight loss procedure, which hold statistical significance only for CRI-2 parameter. Subgrouping for body weight loss, gender or anthropometric category change resulted in a clinically and statistically non-significant difference in any of the resulting subgroups for CRI–1. Similar subgrouping for CRI–2 for the between-after comparison resulted in a statistically significant difference for the men and the obese subgroups. Considering the accepted range of normal values for both indexes, integrating both CRI–1 and CRI–2 values into a single dichotomous index (defined as modified if any of the two is elevated), our intervention resulted in a 10.5% reduction in the number of patients at increased risk for cardiovascular disease – from 52.1% above the upper limit at inclusion, to 46.6% at exit [

19]. In our study, there was a strong correlation between the relative changes of CRI – 1 and CRI – 2. This is probably due to the significant fraction of total cholesterol present in the LDL form, whereby any variation in total cholesterol corresponds directly to a change in LDL cholesterol.

The presence of metabolic syndrome and increased body weight in comparison to normal weight have been associated with increased values in both indices [

37,

38]. However, our study lacked a control group, and among the obese and overweight individuals we could not identify a statistically significant difference either at enrollment or exit. Weight loss after bariatric surgery in patients suffering from type 2 diabetes led to a significant improvement in HDL-C and a statistically significant reduction in AIP, CRI – 1 and CRI – 2 over the long-term [

25]. Another study concerning the effects of bariatric surgery upon improvement of metabolic profile showed that CRI indices were positively correlated to weight loss and inversely to excess fat mass [

39]. To our knowledge, this is the first study concerning the effect of dietary-based weight loss intervention upon indices for atherosclerosis and advanced cardiovascular disease. The important reduction in CRI – 2 translates to improved cardiovascular health and delayed CVD installation.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, an early manifestation of CVD, can be analytically predicted through the use of CRI – 1 and CRI – 2. Both exhibited sensitivities exceeding 70% in a study involving 298 adults at a tertiary care center. Adjustment for several anthropometric and clinical factors (e.g., age, smoking status, presence of diabetes mellitus, frequency of physical activity practice) cancelled the predictive ability of CRI – 1 and CRI – 2, contrasting with the robustness of AIP [

33]. CRI – 1 and CRI – 2 held prognostic significance for any form of CVD, but in that case the association appeared more robust in women from the general population [

40]. Another piece of research noted that CRI – 1 and CRI – 2 may display sex-related differences, since both returned higher values in men of working age before and after adjustment for anthropometric and laboratory parameters [

41]. This observation may constitute the basis for the noted epidemiological differences in cardiometabolic disease, warranting the use of these indices in fundamental screening.

Presence and severity of coronary artery disease (CAD) as predicted by CRI – 1 and CRI – 2 is still disputed. Angiographically confirmed presence of CAD was associated with higher values of these indices, in spite of the absence of a difference in lipid profile lab values [

42]. This finding was confirmed in a more recent study on 1187 subjects, 781 of which underwent coronary angiography. Not only was presence of stenosis associated with presence of arterial stenosis, but an individual increase in CRI – 1 or CRI – 2 was associated with multi-vessel coronary artery stenosis [

43]. However, the predictive ability may be voided under acute settings. Evaluation of cardiometabolic composite indices within the near time proximity to an acute myocardial infarction – with or without ST-elevation – event does not show promising prognostic features [

34,

44]. In patients who suffered such a major cardiovascular event (i.e., MACE, a form of manifest CAD), neither CRI – 1 nor CRI – 2 should be used as predictors for another MACE or all-cause mortality over long term follow-up [

34].

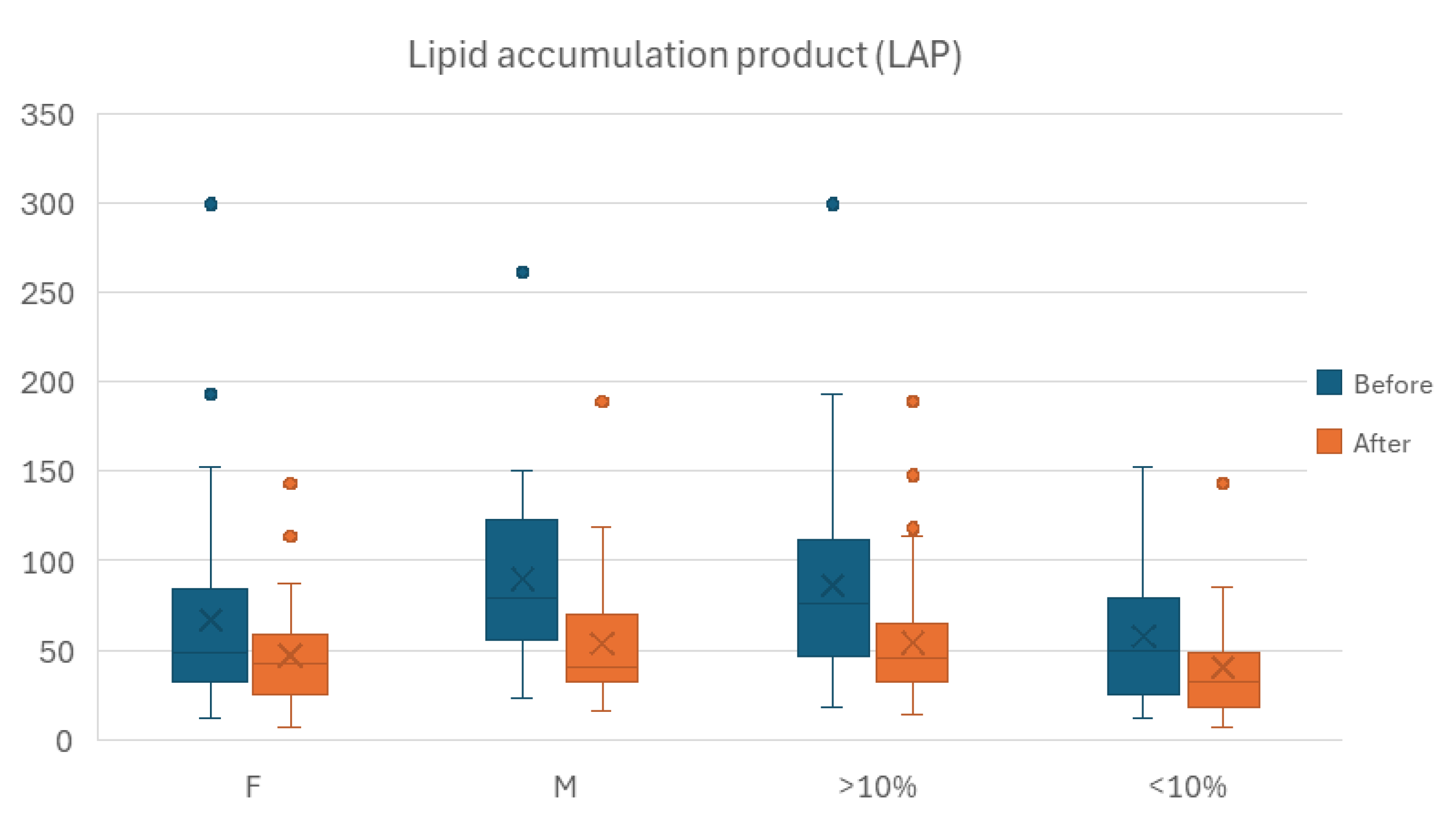

4.3. Lipid Accumulation Product and Atherogenic Central Load Index

In our study we calculated LAP using a formula for women (waist circumference [cm] - 58) × (triglycerides [mmol/L]) and for men (waist circumference [cm] - 65) × (triglycerides [mmol/L]), advanced over 20 years ago for a better prognostic ability compared to BMI for cardiovascular risk [

45]. Diet-based approach to weight loss in our study resulted in a reduction of LAP, statistically significant after adjustment for several factors – gender, percentage of weight lost, anthropometric starting and ending category. The effect of controlled appropriate diet upon improvement of lipid profile has been demonstrated in both healthy and metabolically impaired adults. Evidence shows that adopting a DASH diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) in adults with metabolic syndrome can significantly improve lipid profile [

46]. A more permissive strategy based on semiquantitative assessment of the subjects` usual diet showed that a lower carbohydrate content is associated with reduced levels of visceral fat, albeit this relation was true only in women [

47].

Within the before-after analysis, we performed stratification for percentage of body weight loss as a result of the intervention, using the cutoff value of 10% This resulted in a 25-individuals moderate weight loss sample and a 48-individuals mild weight loss group. AIP and CRI-1 showed no statistically significant difference within any of the two resulting subgroups between the two instances of time. While CRI-2 returned a statistically significant difference between study exit and enrollment on the whole sample, stratification by relative weight loss canceled the statistical significance in both resulting subgroups.

LAP maintained the statistically significant difference observed for the entire population for Before-After assessment in both of the resulting subgroups, with the lower values recorded at the latter point in time.

We also performed stratification for gender, male and female, as medically assessed at enrollment. Despite AIP did not return a statistically significant difference between the before and after time points for the overall sample. Only the male group showed lower overall values for AIP outcome, the difference attaining statistical significance. Neither the male nor the female subgroup showed a significant Before-After difference for the CRI-1 outcome. For the CRI-2 outcome however, stratification for gender maintained statistical significance for the Before-After difference within the male subgroup.

LAP kept the statistically significant difference observed for the entire population for Before-After assessment in both females and males, with the lower values recorded at the latter point in time.

Figure 7 illustrates the differences in outcomes.

The last stratification attempt was performed for change (or lack thereof) of anthropometric category. Sample size led us to obtain three significant subgroups: 10 overweight individuals who remained overweight; 15 obese individuals to advanced to overweight category; and 45 individuals who remained obese. In neither of the three groups for outcomes AIP and CRI-1 the difference between Before-After time points was statistically significant. For CRI-2 outcome, the Before-After comparison showed lower values at the latter time point for both categories of individuals starting as obese. However, sample size allowed only for the larger subgroup to attain a statistically significant difference, as shown in

Figure 8.

Since its advancement as a straightforward parameter for visceral adiposity evaluation, LAP has since proved its detection ability for both cardiovascular risk and disease. In a relatively small sample of 210 patients from the general population, LAP was associated with altered lipid profile and elevated diastolic blood pressure [

48]. Larger scale studies with over 50000 and 95000 patients showed similar findings, where individuals in the largest quartile bracket of LAP values had the highest incidence of CVD and all-cause mortality [

49,

50]. This association remained significant even after controlling potential confounding variables within the general population, an increase of one unit in LAP translating into a 4-fold hazard risk increase for CVD [

50]. Notably, on a cohort of 3000 individuals from the general population without cardiovascular disease diagnosis, LAP demonstrated superior prognostic value for cardiovascular disease incidence over a 10-year follow-up period compared to traditional anthropometric measures and lipid profile laboratory parameters [

51]. The clinical usability of LAP extends to prediction of cardiovascular hospitalization over long-term follow-up in individuals suffering from stable ischemic heart disease [

52]. Seriate evaluation of LAP may be of use, as shown by the increased risk for ischemic stroke in patients exposed to a higher LAP over a longer period [

53]. The association between LAP, a surrogate marker of abdominal obesity, and all-mortality is partly mediated by inflammation in older adults harboring cardiovascular risks [

54].

LAP is a product-derived index, with both parameters expectedly shifting in the same direction after a successful weight loss intervention. Confined to our research protocol, this index has limited use for assessing intervention efficacy, since any reduction in waist circumference and a – proportional or not to – improvement in lipid profile would synergically reduce LAP.

For this reason, we developed ACLI, which has not yet been indexed in the specialized literature.

The proposed formula ensures coherence from a physio-pathological point of view. Logarithmic transformation of the ratio ensures robustness of the formula to extreme values, thus decreasing sensitivity to outlier values. The formula also includes a normalization of the index by referring to the protective component of HDL values found in the AIP formula.

We maintained within the formula the correction for waist circumference. Regarding the numerical results, AIP and ACLI have shown a strong inverse correlation. Our hypothesis is that ACLI may have a high prognostic capacity, which needs to be justified by future studies. The cardiovascular prediction potential could be tested in similar interventional studies (focused on weight loss), with long follow-up periods.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

Our study is a reinforcement for the beneficial effects of weight loss translating into a lower risk for cardiovascular or metabolic diseases. This is one of the few research projects to evaluate the impact of weight loss upon lipid profile-derived indices, and to our knowledge this is the first study where the intervention is diet-based. The study setting and initial screening methodology was elaborated around the characteristics of a potential individual fit for a safe and efficient weight loss process. Intervention was strictly controlled for any excessive aerobic exercise in order to ensure uniformity. Statistical analysis was optimized for best accuracy, despite the infrequent detrimental effect of losing clinical significance of the results (e.g., Spearman correlation). Subgrouping strategy was based upon routine heterogeneity aspects of weight loss. The planned outcomes for analysis included indexes consistently linked to cardiovascular and metabolic health not yet approved for indiscriminate use, outlining the need for additional research. However, there are limiting aspects to our research. The strict criteria of exclusion may adversely affect the applicability of our results to frail patients. The absence of an additional aerobic exercise program might be detrimental to muscle mass maintenance and endothelial functional status. Regression analysis by ranking in a monotonous non-linear dependency might diminish interpretability. Nevertheless, the restricted choice of non-imaging composite indexes for outcomes out of a vast array of available derived parameters is an inherent limitation by design.

5. Conclusions

According to the present study, dietary-based interventions for weight loss are effective, safe and beneficial to metabolic and cardiovascular health. A reduction in body weight translates to an improvement in lipid profile values and composite indexes acting as prognostic factors for adverse cardiovascular events.

Our results highlighted the superior potential of the ACLI index for predicting endothelial dysfunction with reference to the inflammatory markers hs-CRP and IL-6, compared to traditional derived indices associated with atherosclerosis progression (AIP, CRI-1 and CRI-2).

Since dietary-based approaches are often more convenient to patients and can be safely implemented in individuals with significant physical impairment, clinicians should consider this approach in selected individuals. Large-scale successful application of dietary-focused weight loss plans would lead to a reduction in future hospitalization and medication costs and enhanced quality of life for the patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L., I.L.S., M.A.M., and M.M.; methodology, C.L., D.N.S., I.L.S., C.T.C., A.C. and M.M.; software, M.M. and D.N.S.; validation, I.L.S., C.L. and M.A.M.; formal analysis, C.T.C. and A.C.; investigation, C.L., M.A.M., A.C.; resources, C.T.C. and D.N.S.; data curation, C.L., I.L.S., D.N.S., C.T.C., A.C. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L., I.L.S. and D.N.S.; writing—review and editing, M.M. and M.A.M.; visualization, C.L., C.T.C. and A.C.; supervision, I.L.S. and D.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Grigore T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Iasi, Romania, the Scientific Research Committee (345/07.09.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| HbA1c |

Glycated Hemoglobin |

| HDL-C |

High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| LDL |

Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| TC |

Total Cholesterol |

| Δ |

Difference |

| AIP |

Atherogenic Index of Plasma |

| CRI-1 |

Castelli Risk Indexes – 1 |

| CRI-2 |

Castelli Risk Indexes – 2 |

| LAP |

Lipid Accumulation Product |

| ACLI |

Atherogenic Central Load Index |

| hs-CRP |

high sensitivity C-Reactive Protein |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

References

- Addissouky, T.A.; El Sayed, I.E.T.; Ali, M.M.A.; Alubiady, M.H.S.; Wang, Y. Recent developments in the diagnosis, treatment, and management of cardiovascular diseases through artificial intelligence and other innovative approaches. J. Biomed. Res. 2024, 5, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.S.; Deng, J.W.; Geng, W.Y.; Zheng, R.; Xu, H.L.; Dong, Y.; Huang, W.D.; Li, Y.I. Temporal trend and attributable risk factors of cardiovascular disease burden for adults 55 years and older in 204 countries/territories from 1990 to 2021: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Eur. J. Prevent. Cardiol. 2025, 32, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patial, S.; Sharma, A.; Raj, K.; Shukla, G. Atherosclerosis: Progression, risk factors, diagnosis, treatment, probiotics and synbiotics as a new prophylactic hope. Microbe 2024, 5, 100212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasouli-Drakou, V.; Ogurek, I.; Shaikh, T.; Ringor, M.; DiCaro, M.V.; Lei, K. Atherosclerosis: A Comprehensive Review of Molecular Factors and Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henning, R.J. Obesity and obesity-induced inflammatory disease contribute to atherosclerosis: a review of the pathophysiology and treatment of obesity. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 11, 504–529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reiss, B.A.; Glass, D.S.; Voloshyna, I.; Glass, A.D.; Kasselman, L.J.; De Leon, J. Obesity and atherosclerosis: the exosome link. Vessel Plus 2020, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Mohammed, R.A. Obesity: Prevalence, causes, consequences, management, preventive strategies and future research directions. Metab. Open 2025, 27, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, F.; Cummings, D.E.; Eckel, R.H.; Cohen, R.V.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Brown, W.A.; Stanford, F.C.; Batterham, R.L.; Farooqi, I.S.; Farpour-Lambert, N.J.; et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 221–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; Neeland, I.J.; Yamashita, S.; Shai, I.; Seidell, J.; Magni, P.; Santos, R.D.; Arsenault, B.; Cuevas, A.; Hu, F.B.; et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Liu, M. Adiponectin: friend or foe in obesity and inflammation. Med. Rev. 2022, 2, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Han, B.; Gu, T.; Jiang, X. Resistin in cardiac diseases: from molecular mechanisms to clinical implications. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1708332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilarino-Garcia, T.; Polonio-Gonzalez, M.L.; Perez-Perez, A.; Ribalta, J.; Arrieta, F.; Aguilar, M.; Obaya, J.C.; Gimeno-Orna, J.A.; Iglesias, P.; Navarro, J.; et al. Role of Leptin in Obesity, Cardiovascular Disease, and Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xin, C.; Yao, J.; Wang, H. Relationship Between Leptin and Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis. Global Heart 2025, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynarska, E.; Bojdo, K.; Frankenstein, H.; Krawiranda, K.; Kustosik, N.; Lisinska, W.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. Endothelial Dysfunction as the Common Pathway Linking Obesity, Hypertension and Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khafagy, R.; Dash, S. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: The Emerging Role of Inflammation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 768119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauclard, A.; Bellio, M.; Valet, C.; Borret, M.; Payrastre, B.; Severin, S. Obesity: Effects on bone marrow homeostasis and platelet activation. Thromb. Res. 2023, 231, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, B.; Nayfeh, T.; Alzuabi, M.; Wang, Z.; Kuchkuntla, A.R.; Prokop, L.J.; Newman, C.B.; Murad, M.H.; Rajjo, T.I. Weight Loss and Serum Lipids in Overweight and Obese Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 3695–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balder, J.W.; de Vries, J.K.; Nalte, I.M.; Lansberg, P.J.; Kuivenhaven, J.A.; Kamphuisen, P.W. Lipid and lipoprotein reference values from 133,450 Dutch Lifelines participants: Age- and gender-specific baseline lipid values and percentiles. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2017, 11, 1055–1064, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggini, M.; Gorini, F.; Vassalle, C. Lipids in Atherosclerosis: Pathophysiology and the Role of Calculated Lipid Indices in Assessing Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Hyperlipidemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyhan, S.K.; Yadegar, A.; Samimi, S.; Nakhaei, P.; Esteghamati, A.; Nakhjavani, M.; Reihan, S.R.; Rabizadeh, S. Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP): The Most Accurate Indicator of Overweight and Obesity Among Lipid Indices in Type 2 Diabetes—Findings From a Cross-Sectional Study. Endocrinol. Diabetes. Metab. 2024, e7, 700007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yu, L.; Ma, Q.; Zhou, H.; Lei, T.; Hu, J.; Xu, W.; Yi, N.; Lei, S. Atherogenic index of plasma is a novel and better biomarker associated with obesity: a population-based cross-sectional study in China. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, R.; Farhangi, M.A. Dietary and plasma atherogenic and thrombogenic indices and cardiometabolic risk factors among overweight and individuals with obesity. BMC Endocrine Dis. 2025, 25, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.S.; Chen, Y.R; Lin, Y.H.; Wu, H.K.; Lee, Y.W.; Chen, J.Y. Evaluating atherogenic index of plasma as a predictor for metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional analysis from Northern Taiwan. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalejska-Fiolka, J.; Hubkova, B.; Birkova, A.; Velika, B.; Puchalska, B.; Kasperczyk, S.; Blaszczyk, U.; Fiolka, R.; Bozek, A.; Maksym, B.; et al. Prognostic Value of the Modified Atherogenic Index of Plasma during Body Mass Reduction in Polish Obese/Overweight People. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2018, 16, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyedi, A.; Rabizadeh, S.; Abbaspour, F.; Reyhan, S.K.; Soran, N.A.; Nabipoor, A.; Yadegar, A.; Mohammadi, F.; Hashemi, R.; Qahremani, R.; et al. The trend of atherogenic indices in patients with type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: a national cohort study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2025, 21, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capomolla, A.S.; Janda, E.; Paone, S.; Parafati, M.; Sawicki, T.; Mollace, R.; Ragusa, S.; Mollace, V. Atherogenic Index Reduction and Weight Loss in Metabolic Syndrome Patients Treated with A Novel Pectin-Enriched Formulation of Bergamot Polyphenols. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, H.; Tan, Q.; Ji, J.; Cheng, J.; Lu, F. Relationship between plasma atherogenic index and incidence of cardiovascular diseases in Chinese middle-aged and elderly people. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, K.B.; Heo, R.; Park, H.B.; Lee, B.K.; Lin, F.Y.; Hadamitzky, M.; Kim, Y.J.; Sung, J.M.; Conte, E.; Andreini, D.; et al. Atherogenic index of plasma and the risk of rapid progression of coronary atherosclerosis beyond traditional risk factors. Atherosclerosis 2001, 24, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, M.R.; Dabaghi, G.G.; Darouei, B.; Amani-Beni, R. The association of atherogenic index of plasma with cardiovascular outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Xie, G.; Jian, G.; Jiang, K.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Lan, H.; Wang, W.; He, S.; Zou, Y.; Wang, C. Association of cumulative changes in atherogenic index of plasma and its obesity-related derivatives with cardiovascular disease: emphasis on incremental risk of diabetes status. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wen, P.; Liao, Y.; Wu, T.; Zeng, L.; Huang, Y.; Song, X.; Xiong, Z.; Deng, L.; Li, D.; Miao, S. Association of atherogenic index of plasma and its modified indices with stroke risk in individuals with cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stages 0–3: a longitudinal analysis based on CHARLS. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Cho, Y.K.; Kim, Y.J.; Jung, C.H.; Lee, W.J.; Park, J.Y.; Huh, J.H.; Kang, J.G.; Lee, S.J.; Ihm, S.H. Association of the atherogenic index of plasma with cardiovascular risk beyond the traditional risk factors: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, Y.B.; Almeida, A.B.R.; Viana, M.F.M.; Meneguz-Moreno, R.A. Use of Atherogenic Indices as Assessment Methods of Clinical Atherosclerotic Diseases. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2023, 120, e20230418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokicka, D.; Hudzik, B.; Wrobel, M.; Stoltny, T.; Stoltny, D.; Nowowiejska-Wiewiora, A.; Rokicka, S.; Gasior, M.; Strojek, K. Prognostic value of novel atherogenic indices in patients with acute myocardial infarction with and without type 2 diabetes. J. Diab. Compl. 2024, 38, 108850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioy, B.; Webb, R.J.; Amirabdollahian, F. The Association between the Atherogenic Index of Plasma and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, L.; Tian, N.; Zhu, M.; Liu, C.; Hou, T.; Du, Y. Association of the atherogenic index of plasma with cognitive function and oxidative stress: A population-based study. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2025, 105, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaj, I.; Thalamati, M.; Gowda, V.M.N.; Rao, A. The Role of the Atherogenic Index of Plasma and the Castelli Risk Index I and II in Cardiovascular Disease. Cureus 2024, 16, e74644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrashekhar, D.M.; Anand, K.; Jayalakshmi, M.K.; Prashanth, B. Impact of Obesity on Castelli’s Risk Index I and II, in Young Adult Females. Int. J. Physiol. 2020, 8, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadnoush, M.; Tabesh, M.R.; Asadzadeh-Aghdaei, H.; Hafizi, N.; Alipour, M.; Zahedi, H.; Mehrakizadeh, A.; Cheraghpour, M. Effect of bariatric surgery on atherogenicity and insulin resistance in patients with obesity class II: a prospective study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e072418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvari, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Chrysohoou, C.; Georgousopoulou, E.N.; Tousoulis, D.; Pitsavos, C. Sex-Related Differences of the Effect of Lipoproteins and Apolipoproteins on 10-Year Cardiovascular Disease Risk; Insights from the ATTICA Study (2002–2012). Molecules 2020, 25, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigna, L.; Tirelli, A.S.; Gaggini, M.; Di Piazza, S.; Tomaino, L.; Turolo, S.; Moroncini, G.; Chatzianagnostou, K.; Bamonti, F.; Vassalle, C. Insulin Resistance and Cardiometabolic Indexes: Comparison of Concordance in Working-Age Subjects with Overweight and Obesity. Endocrine 2022, 77, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Bhattacharjee, J.; Bhatnagar, M.K.; Tyagi, S. Atherogenic index of plasma, castelli risk index and atherogenic coefficient- new parameters in assessing cardiovascular risk. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2013, 3, 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Imannezhad, M.; Kamrani, F.; Shariatikia, A.; Nasrollahi, M.; Mahaki, H.; Rezaee, A.; Moohebati, M.; Shahri, S.H.H.; Darroudi, S. Association of atherogenic indices and triglyceride-total cholesterol-body weight index (TCBI) with severity of stenosis in patients undergoing angiography: a case-control study. BMC Res. Notes 2025, 18, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drwiła, D.; Rostoff, P.; Nessler, J.; Konduracka, E. Prognostic value of non-traditional lipid parameters: Castelli Risk Index I, Castelli Risk Index II, and triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio among patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction during 1-year follow-up. Kardiologiia 2022, 62, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, H.S. The "lipid accumulation product" performs better than the body mass index for recognizing cardiovascular risk: a population-based comparison. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2005, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangouni, A.A.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Parastouei, K. Effect of dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet on insulin resistance and lipid accumulation product in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholami, F.; Martami, F.; Ghorbaninezhad, P.; Mirrafiei, A.; Ebaditabar, M.; Davarzani, S.; Babaei, N.; Djafarian, K.; Shab-Bidar, S. Association of low-carbohydrate diet score and carbohydrate quality with visceral adiposity and lipid accumulation product. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 129, 843–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, L.A.V.; Tofano, R.J.; Barbalho, S.M.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Bechara, M.D.; Tofano, V.A.C.; Haber, J.F.S.; Chagas, E.F.B.; Milla, A.M.G.; Quesada, K. Lipid Accumulation Product: Reliable Marker for Cardiovascular Risk Detection? Open J. Epidemiol. 2021, 11, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Luo, M.; Sheng, Z.; Zhou, R.; Xiang, W.; Huang, W.; Shen, Y. Association of lipid accumulation product with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality: Result from NHANES database. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 34, 1467–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ding, X.; Liang, X.; Zhao, W.; Liu, C.; Lu, X.; Zhao, D.; Wu, S.; Li, Y. A prospective cohort study on the effect of lipid accumulation product index on the incidence of cardiovascular diseases. Nutr. Metab. (London) 2024, 21, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrou, I.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Kouli, G.M.; Georgousopoulou, E.; Chrysohoou, C.; Tsigos, C.; Tousoulis, D.; Pitsavos, C. Lipid accumulation product in relation to 10-year cardiovascular disease incidence in Caucasian adults: The ATTICA study. Atherosclerosis 2018, 279, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papathanasiou, K.A.; Roussos, C.E.; Armylagos, S.; Rallidis, S.L.; Rallidis, L.S. Lipid Accumulation Product Is Predictive of Cardiovascular Hospitalizations among Patients with Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Long-Term Follow-Up of the LAERTES Study. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Lan, Y.; Wu, D.; Chen, S.; Ding, X.; Wu, S. The effect of cumulative lipid accumulation product and related long-term change on incident stroke: The Kailuan Study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 34, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhou, S.; Jia, G.; Wen, W. The association of lipid accumulation product with inflammatory parameters and mortality: evidence from a large population-based study. Front. Epidemiol. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Selection of study participants.

Figure 1.

Selection of study participants.

Figure 2.

Evolution of ponderal status before and after intervention.

Figure 2.

Evolution of ponderal status before and after intervention.

Figure 3.

Correlations of the variations (Δ) atherogenic indices: (A) Δ AIP, (B) Δ CRI-1, (C) Δ CRI-2 and Δ ACLI values.

Figure 3.

Correlations of the variations (Δ) atherogenic indices: (A) Δ AIP, (B) Δ CRI-1, (C) Δ CRI-2 and Δ ACLI values.

Figure 4.

Correlation of hs-CRP values from pre- and post-intervention time with AIP and ACLI values respectively. (A) pre-intervention (before) hs-CRP vs AIP; (B) pre-intervention (before) hs⁻CRP vs ACLI; (C) post-intervention (after) hs-CRP vs AIP; (D) post-intervention (after) hs-CRP vs ACLI.

Figure 4.

Correlation of hs-CRP values from pre- and post-intervention time with AIP and ACLI values respectively. (A) pre-intervention (before) hs-CRP vs AIP; (B) pre-intervention (before) hs⁻CRP vs ACLI; (C) post-intervention (after) hs-CRP vs AIP; (D) post-intervention (after) hs-CRP vs ACLI.

Figure 5.

Correlation of IL-6 values from pre- and post-intervention time with AIP and ACLI values respectively. (A) pre-intervention (before) IL-6 vs AIP; (B) pre-intervention (before) IL-6 vs ACLI; (C) post-intervention (after) IL-6 vs AIP; (D) post-intervention (after) IL-6 vs ACLI.

Figure 5.

Correlation of IL-6 values from pre- and post-intervention time with AIP and ACLI values respectively. (A) pre-intervention (before) IL-6 vs AIP; (B) pre-intervention (before) IL-6 vs ACLI; (C) post-intervention (after) IL-6 vs AIP; (D) post-intervention (after) IL-6 vs ACLI.

Figure 6.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for comparative evaluation of the predictive value of AIP, CRI-1, CRI-2 and ACLI for the inflammatory markers hs-CRP and IL-6. (A) preintervention (before) IL-6; (B) preintervention (before) hs-CRP; (C) postintervention (after) IL-6; (D) postintervention (after) hs⁻CRP.

Figure 6.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for comparative evaluation of the predictive value of AIP, CRI-1, CRI-2 and ACLI for the inflammatory markers hs-CRP and IL-6. (A) preintervention (before) IL-6; (B) preintervention (before) hs-CRP; (C) postintervention (after) IL-6; (D) postintervention (after) hs⁻CRP.

Figure 9.

Mechanisms underlying endothelial dysfunction in obesity or overweight.

Figure 9.

Mechanisms underlying endothelial dysfunction in obesity or overweight.

Figure 7.

Evolution of LAP Before-After comparison wise, stratified by percentage of body weight lost (BWL), lower than 10% classified as mild, more than 10% as moderate, and by gender (M, men; F, women).

Figure 7.

Evolution of LAP Before-After comparison wise, stratified by percentage of body weight lost (BWL), lower than 10% classified as mild, more than 10% as moderate, and by gender (M, men; F, women).

Figure 8.

Before-After comparison stratified by classifying individuals upon body weight category at study entry and exit, respectively. CRI–2, Castelli Risk Index – 2.

Figure 8.

Before-After comparison stratified by classifying individuals upon body weight category at study entry and exit, respectively. CRI–2, Castelli Risk Index – 2.

Table 1.

Anthropometric and biochemical characteristics at the time of enrollment and after 6 months of intervention initiation.

Table 1.

Anthropometric and biochemical characteristics at the time of enrollment and after 6 months of intervention initiation.

Anthropometric and

biochemical measurements |

Before (at enrollment) |

After (at study exit) |

p-value* |

| Age (years), mean ± SD |

46.4 ± 9.8 |

- |

|

| Gender (M/F), n(%) |

30 / 43 (41.1% / 58.9%) |

- |

|

| Height (m) |

1.68 (1.62 – 1.76) |

- |

|

| Weight (Kg) |

100.5 (87.7 – 118.7) |

89 (78 – 102) |

0.002 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) |

34.9 (31.8 – 41.2) |

31.2 (27.9 – 34.9) |

0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) |

98 (87 – 107) |

89 (80 – 97) |

<0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg |

124 (92 – 189) |

112 (84 – 164) |

0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg |

89 (72 – 121) |

71 (54 – 109) |

0.024 |

| Heart rate, bpm |

67.2 (72.4 – 90.2) |

63.8 (69 – 87) |

0.018 |

| Biochemical profile |

|

|

|

| Fasting blood glucose, (mg/dL) |

102 ± 49.8 |

93.6 ± 41.2 |

0.001 |

| HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin, % |

5.3 (5 – 5.5) |

5.2 (4.9 – 5.4) |

0.003 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) |

47 ± 12.5 |

45 ± 8.8 |

0.001 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) |

152 ± 40.8 |

138 ± 29.6 |

<0.001 |

| TC (mg/dL) |

215 ± 40.9 |

202 ± 32.2 |

0.002 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) |

153 (113 – 210) |

138 (104 – 178) |

0.001 |

| Atherogenic indices |

|

|

|

| AIP |

0.523 ± 0.227 |

0.487 ± 0.162 |

0.046 |

| CRI–1 |

4.66 (3.77 – 5.35) |

4.60 (3.88 – 5.26) |

0.054 |

| CRI–2 |

3.28 (2.57 – 4) |

3.22 (2.55 – 3.71) |

0.001 |

| Lipid profile |

|

|

|

| LAP |

62.6 (38.3 – 94.6) |

40.3 (27.4 – 64.8) |

<0.001 |

Atherogenic Central Load Index

(ACLI) |

55.43 (46.85 – 68.5) |

43.27 (35.7 – 52.5) |

0.001 |

| Inflammation markers |

|

|

|

| hs-CRP, mg/L |

3.76 (2.8 – 6.2) |

2.84 (1.7 – 3.89) |

<0.001 |

| IL-6, pg/mL |

2.9 (1.23 – 4.11) |

2.18 (0.8 – 3.03) |

<0.001 |

Table 2.

Difference in anthropometric and biochemical parameter values at enrollment compared to 6 months after intervention initiation

Table 2.

Difference in anthropometric and biochemical parameter values at enrollment compared to 6 months after intervention initiation

Δ,

difference: postintervention

and preintervention |

Mean Change,

mean (SD) |

95% Confidence Interval

of the mean change |

p - value |

| Δ Weight, kg |

-9.52 (3.45) |

-10.33 to -8.72 |

0.002 |

| Δ Weight %, median (IQR) |

9.6% (7.3% - 11.5%) |

|

|

| Δ BMI |

-3.29 (1.16) |

-3.56 to -3.02 |

0.001 |

| Δ Waist circumference (cm) |

-7.21 (2.69) |

-7.63 to -6.37 |

<0.001 |

| Δ HDL-C (mg/dL) |

-4.34 (0.86) |

-6.81 to-3.87 |

0.001 |

| Δ LDL-C (mg/dL) |

-19.23 (5.92) |

-21.15 to-17.03 |

<0.001 |

| Δ TC (mg/dL) |

-32.16 (7.85) |

-38.31 to-27.67 |

0.002 |

| Δ Triglycerides (mg/dL) |

-35.41 (16.51) |

-40.47 to-32.58 |

0.001 |

| Δ AIP (Atherogenic index of plasma) |

-0.09 (0.03) |

-0.09 to-0.08 |

0.046 |

| Δ CRI – 1 |

-0.52 (0.27) |

-0.58 to-0.46 |

0.054 |

| Δ CRI – 2 |

-0.31 (0.15 |

-0.35 to-0.28 |

0.001 |

| Δ LAP |

-9.53 (1.92) |

-11.17 to-7.89 |

<0.001 |

|

ΔACLI

|

-13.92 (6.19) |

-15.36 to-12.47 |

<0.001 |

| Δ hs-CRP, mg/L |

-1.16 (0.74) |

-1.34 to-0.99 |

<0.001 |

| Δ IL-6, pg/mL |

-0.81 (0.54) |

-0.94 to-0.68 |

<0.001 |

Table 3.

Discriminative accuracy of indices associated with atherosclerosis progression regarding the inflammatory markers hs-CRP and IL-6 for obese or overweight patients involved in dietary weight loss interventions.

Table 3.

Discriminative accuracy of indices associated with atherosclerosis progression regarding the inflammatory markers hs-CRP and IL-6 for obese or overweight patients involved in dietary weight loss interventions.

| Test Result Variable(s): |

Area Under the Curve

(95%CI) |

p-value |

| IL-6 before |

|

|

| ACLI_pre |

0.944 (0.883 to 1.000) |

<0.001 |

| AIP_pre |

0.871 (0.782 to 0.960) |

<0.001 |

| Castelli1_pre |

0.721 (0.605 to 0.837) |

0.001 |

| Castelli2_pre |

0.587 (0.454 to 0.719) |

0.203 |

| hs-CRP before |

|

|

| ACLI_pre |

0.947 (0.902 to 0.993) |

<0.001 |

| AIP_pre |

0.870 (0.784 to 0.957) |

<0.001 |

| Castelli1_pre |

0.719 (0.602 to 0.836) |

0.001 |

| Castelli2_pre |

0.635 (0.505 to 0.765) |

0.048 |

| IL-6 after |

|

|

| ACLI_post |

0.862 (0.771 to 0.952) |

<0.001 |

| AIP_post |

0.698 (0.577 to 0.820) |

0.005 |

| Castelli1_post |

0.691 (0.567 to 0.815) |

0.007 |

| Castelli2_post |

0.659 (0.528 to 0.791) |

0.024 |

| hs-CRP – after |

|

|

| ACLI_post |

0.844 (0.754 to 0.933) |

<0.001 |

| AIP_post |

0.738 (0.625 to 0.852) |

<0.001 |

| Castelli1_post |

0.715 (0.597 to 0.833) |

0.002 |

| Castelli2_post |

0.641 (0.513 to 0.768) |

0.039 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).