1. Introduction

Regional or local advertising refers to promotional activities conducted by retailers within a specific geographic market, such as a city, district, or store trading area. Its primary impact lies in generating immediate sales stimulation through price promotions, discounts, limited-time offers, and traffic-driving campaigns. Because messages can be adapted to local consumer preferences, income levels, and competitive environments, retailers gain high responsiveness and flexibility, enabling fast execution not possible with nationwide campaigns. Local advertising also strengthens the retailer’s own brand identity and encourages repeat visits, fostering store loyalty. However, its limitations include restricted reach and scale, a tendency to focus heavily on price rather than brand value, and relatively weak contribution to long-term brand equity.

National advertising is created and funded by manufacturers to promote their brands across a broad or nationwide market, often using large-scale media such as television, online video platforms, and national digital campaigns. Its primary role is building brand awareness and shaping brand identity, helping consumers perceive quality and develop emotional connections—an essential foundation for long-term brand equity. National advertising also creates a strong pull effect, encouraging consumers to seek out the brand at retail stores and increasing their willingness to pay. Additionally, it supports retailers by reducing their selling efforts since consumers already recognize the brand. Nonetheless, national campaigns require significant financial investment, offer limited adaptation to local differences, and tend to have a weaker direct effect on immediate store-level sales.

Cooperative advertising (co-op advertising) is a collaborative promotional arrangement in which the manufacturer and retailer share advertising expenses while jointly featuring both the brand and the store. This type of advertising often displays the manufacturer’s brand, products, and imagery alongside the retailer’s store name, pricing, and promotional details. The structure allows both parties to combine strengths—manufacturer brand power and retailer local presence—while optimizing the return on advertising investment. Through co-op advertising, manufacturers gain greater influence at the retail level, and retailers receive financial and creative support that enhances their promotional impact.

Cooperative advertising can take multiple forms depending on the extent of funding and control. In manufacturer-supported co-op advertising, manufacturers reimburse a significant proportion—often 50% to 100%—of the retailer’s advertising expenses, provided the retailer follows brand guidelines regarding logos, messaging, and visual style. Another form is joint promotional campaigns, in which both parties collaboratively plan seasonal promotions, new product launches, or special retail events that integrate national branding with local execution. Digital cooperative advertising has become increasingly important, with manufacturers supplying digital materials and funding, while retailers manage local targeting, placement, and on-platform optimization in their specific markets.

Cooperative advertising provides significant advantages for both manufacturers and retailers. For manufacturers, it strengthens the push effect within distribution channels by motivating retailers to actively promote the brand, improving shelf space, in-store displays, and visibility. It also ensures consistent brand messaging across diverse local markets and prevents excessive price-focused promotions that may damage brand equity. Furthermore, co-op advertising helps convert national brand awareness into actual retail-level sales. For retailers, benefits include reduced advertising costs, improved promotional effectiveness through combining brand credibility with local price incentives, and competitive advantages—since not all rivals receive the same level of manufacturer support. Together, these advantages create stronger promotional positioning and enhanced market performance at the local level.

In real-world business environments, it is often difficult to draw a clear boundary between conflict and cooperation. Firms frequently compete and collaborate simultaneously, forming a complex relationship commonly described as co-opetition. This phenomenon is particularly evident in production–retail distribution channels, where manufacturers and retailers pursue their own profit objectives while remaining mutually dependent. For example, global manufacturers such as Procter & Gamble frequently engage in cooperative advertising programs with major retailers like Walmart, jointly funding seasonal promotions for fast-moving consumer goods. While such cooperation enhances demand and market visibility, underlying conflicts persist regarding cost-sharing ratios, pricing power, and profit allocation. Similar dynamics can be observed in the beverage industry, where Coca-Cola cooperates with retailers worldwide on seasonal advertising campaigns during peak consumption periods, such as summer or major sporting events, while simultaneously negotiating aggressively over margins and shelf space. These examples illustrate how cooperation and competition coexist within distribution channels, making strategic decision-making inherently interactive and interdependent. As a result, game theory has emerged as a powerful analytical framework for modeling such strategic interactions, as it explicitly captures the strategic behavior of multiple decision-makers operating under conflicting yet interlinked objectives.

Game theory, and in particular Nash and Stackelberg equilibrium concepts, provides firms with a systematic approach to evaluating optimal strategies by anticipating competitors’ responses. In advertising and promotion decisions, where outcomes depend heavily on rivals’ actions, game-theoretic analysis enables firms to assess whether cooperative or non-cooperative strategies yield superior outcomes. For instance, in the smartphone industry, Apple often engages in cooperative advertising with telecom operators, sharing promotional expenditures for new product launches during seasonal demand peaks such as holiday periods. While retailers benefit from increased traffic and shared costs, manufacturers must carefully evaluate whether the resulting demand expansion compensates for the additional advertising investment. These strategic considerations become even more complex when multiple competing retailers are involved, as advertising cooperation with one retailer may intensify competition among downstream firms. Moreover, leadership structure within the channel plays a crucial role. When manufacturers act as leaders, as in Stackelberg-type relationships, they can design advertising cost-sharing mechanisms that improve channel coordination and overall profitability. In contrast, when manufacturers and retailers act simultaneously under Nash equilibrium conditions, the lack of coordination often leads to lower advertising levels and reduced profits for all parties. Despite the prevalence of cooperative advertising in seasonal markets, existing studies have paid limited attention to the combined effects of seasonality, channel leadership, and retailer competition. This paper addresses this gap by developing game-theoretic models to analyze cooperative advertising decisions under seasonal demand, offering both theoretical insights and practical guidance for firms seeking to design effective advertising cooperation mechanisms that balance competition and collaboration within modern supply chains (Yang et al., [

1]; Zhang et al., [

2]).

2. Literature Review

Advertising is typically divided into two categories: national advertising and local advertising, based on whether it is conducted by the manufacturer or the retailer Young & Greyser [

3]. National advertising refers to campaigns conducted by manufacturers in the national market to enhance consumer awareness of the product through various channels and to build a strong brand image that drives potential customers to appreciate their products or make purchase decisions (Karray & Zaccour [

4] ; Karray et al. [

5]; Su et al., [

6]). In contrast, local advertising pertains to campaigns undertaken by retailers within their business circles, primarily focusing on price incentives to boost immediate sales. Hypermarkets like Carrefour, Walmart, and Costco serve as prime examples of mass merchandise stores that exert significant influence on the consumer market. With their extensive product offerings and competitive pricing, they attract a large number of consumers who prefer shopping at these locations. Local advertising can transmit messages regarding promotional activities and discounts of mass merchandisers. It will directly affect consumers’ purchasing behavior and consumption habits (Zhang et al., [

7]; Li et al., [

8]).

Researchers have focused on the exploration of manufacturers’ cooperative advertising mechanisms with retailers. Various studies highlight different forms of subsidies, models, and contractual arrangements aimed at optimizing advertising efforts, coordinating supply chains, and maximizing profits. These mechanisms, grounded in game theory and cooperative strategies, address market demand influences, cost-sharing, and inventory management between manufacturers and retailers. Jørgensen et al. [

9] identified two main types of manufacturers’ subsidies for retailers’ advertising: direct cash subsidies and cooperative mechanisms to share costs indirectly. Using a two-stage Stackelberg model, they showed how manufacturers lead in designing cooperative advertising to boost retailers’ efforts, meet market demand, and maximize profits. Huang and Li [

10] used game theory to explore how both national and local advertising affect demand and the benefits of cooperative advertising. Krishnan et al. [

11] proposed contracts to regulate manufacturer-retailer relationships, addressing market demand uncertainties, return prices, advertising cost sharing, and inventory management. Maciel & Fischer [

12] addressed that firms can achieve market evolution through cooperative strategies with their peers and other stakeholders. They outline the triggers that lead firms to engage in collective action and how these collaborations can transform shared resources into effective market-driving power. Zhang et al. [

13] developed a cooperative advertising model focusing on supply chains with differing power dynamics between manufacturers and retailers. The study uses game theory to assess how manufacturers and retailers can coordinate advertising efforts, balancing their roles to maximize efficiency and profitability in the supply chain under vertical cooperative advertising models.

Seasonal goods have uncertain demands and limited, short selling periods. Once the selling period ends, although the goods retain their value and function, seasonal changes render surplus stocks, leading to their sale at lower prices or destruction (Wolters & Huchzermeier [

14]; Daniel et al. [

15]). Examples include Christmas cards, seasonal fashion clothes, 3C electronics, and other high-tech products. These items are typically priced high at the beginning of the selling period, with prices gradually decreasing to promote sales of remaining stocks. Some goods, such as milk in supermarkets, fresh food, airline seats, hotel rooms, concerts, and movie tickets, may lose their original function and value upon expiration. The residual value of such items approaches zero, which resembles the traditional newsboy problem.

The newsboy problem involves determining the optimal order quantity to maximize expected profit or minimize cost in uncertain demand within a fixed period. As products left unsold in one period cannot be used in the next selling period, overordering leads to value loss or minimal residual value, while underordering results in stockouts, reputational damage, or opportunity costs (Jadidi et al., [

16]; Su et al., [

17]). Seasonal goods, characterized by single-period stocks and short selling seasons, require retailers to order all stock for the season at its start, with no replenishment possible. This uncertainty in demand can cause overstock or stockout issues. This study uses the stock theory and model of Petrutti and Dada [

18] to address these stock problems and determine the optimal order quantity for retailers.

In distribution channel management, manufacturers and distributors must maintain a close production-sales relationship, with transparent production and sales information across the entire sales channel. This transparency allows manufacturers to adjust production swiftly to meet market demands while distributors ensure consistent supply to downstream retailers (Andersen & Bering [

19]). Proper coordination between production and sales can improve overall channel costs (Apornak & Keramati, [

20]). From a product sales channel management perspective, distributors are crucial in coordinating production and sales. “Advertising” is a critical function in the distribution system, serving as a key method to stimulate consumption and increase demand. Choi [

21] identified four types of channel structures: single distribution channel, monopolistic retailer channel, monopolistic manufacturer channel, and dual manufacturer-retailer channel.

This study explores the cooperative advertising strategy of a two-stage production and sales system, aiming to maximize profits for both upstream manufacturers and downstream retailers. It examines different relationship dynamics, including those under the Stackelberg and Nash equilibria, and compares their outcomes. In the Stackelberg equilibrium, one party acts as the leader and the other as the follower. In contrast, the Nash equilibrium assumes equal market power for both parties. This study considers the demand function and seasonal pricing in relation to manufacturers’ national advertising and retailers’local advertising. Higher advertising levels increase the market demand and raise advertising costs, necessitating a balance between profits and costs. In a cooperative advertising arrangement, manufacturers may agree to share a portion of the rretailers’advertising costs to enhance advertising efforts and, consequently, their own profits.

3. Modelling

The mathematical model in this study is developed based on the following assumptions:

- (1)

The selling period in the sales process is limited and known.

- (2)

Only a single seasonal product is considered.

- (3)

Consumers do not have complete information about the price of the product before entering the store; they only get to know the price information of the product upon entering.

- (4)

After the initial inventory decision, no further orders and replenishments occur, and only limited stocks are sold during the selling period.

- (5)

At the end of the selling period, the residual value of the unsold products is 0.

- (6)

Cyclical price adjustments are made during the selling period.

- (7)

A two-stage production and sales system are assumed.

- (8)

Market demand is influenced by seasonality, national advertising by manufacturers, and local advertising by retailers.

- (9)

Seasonal demand is related to the selling price of a product (Bitran & Mondschein [

22]).

- (1)

Seasonality may affect demand uncertainty and the residual value of goods.

- (2)

Each selling period is of equal length.

The following notations are used in the study:

Decision variables:

Parameters:

3.1. Single-Manufacturer and Single-Retailer in a Production-Retailing Market Channel

When the market structure comprises a single distribution channel consisting of a manufacturer and a retailer, as shown in

Figure 1, the retailer’s sales are influenced by both its own advertising level and the manufacturer’s advertising level. Customers are assumed to be rational, and the retailer’s advertising affects their purchase willingness based on their preferences. Increased advertising investment by the manufacturer and the retailer can attract more customers. Through channel negotiation and cooperation, appropriate sharing of advertising costs and incentives for credit transactions can expand market demands for both the manufacturer and the retailer. This collaboration also helps mitigate some risk costs for the retailer caused by over-ordering, particularly for seasonal goods.

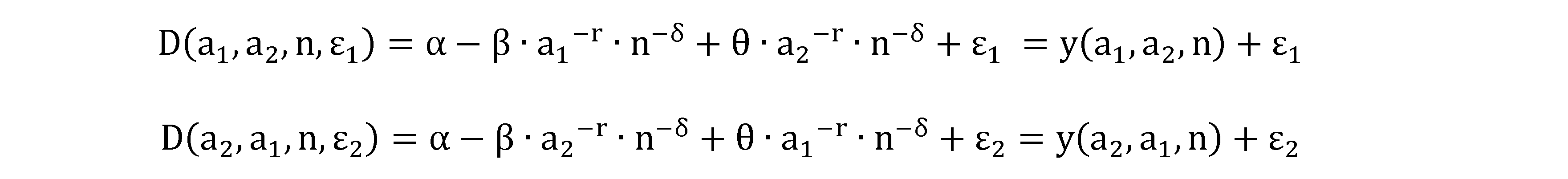

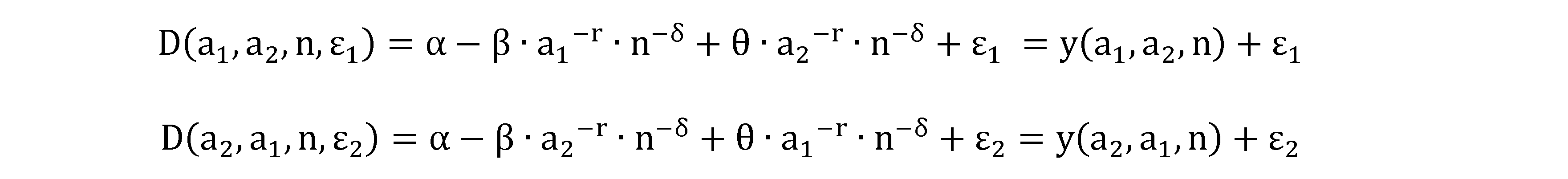

Retailers, being the final link in the production and sales channel, can most directly reflect market information. It is assumed that market demand is related to the national advertising level of the manufacturer (n) and the local advertising level of the retailer (a). These two types of advertising serve different functions—national advertising aims to attract potential customers and enhance brand image while local advertising focuses on immediate purchase incentives—but they are mutually reinforcing and indispensable.

Therefore, the demand function of the retailer can be assumed to include both types of advertising, where α represents the primary market demand, β, r, and δ are all numbers greater than zero, and r and δ represent the effect of two different types of advertising on demand. The larger the value of r, the greater the impact of local advertising on demand. The greater the value of δ, the greater the impact of national advertising on demand. ε is a random variable affecting demand and is assumed to follow the same distribution. The demand function is given by

= y (a, n) +ε. Due to the uncertainty in market demands, retailers cannot accurately predict market demands. When a retailer orders (q) items from a manufacturer during a single selling season, there may be overstock or stockout. If demand is less than the retailer’s order quantity, overstock occurs. In a single-period production and sales model, unsold goods cannot be carried over to the next period, leaving only the residual value per unit (h). If market demands exceed the retailer’s stocks, the retailer sells out and incurs a reputation cost per unit(s) due to the stockout. According to the model, the advertising cost of manufacturers and retailers is assumed to be proportional to their advertising level [

10]. Therefore, the local advertising cost is assumed to be a, and the national advertising cost of the manufacturer is assumed to be n. Given that national advertising costs are generally higher than local ones, n>a>0 is true. The profit functions for retailers and manufacturers are as follows:

Retailers’ profit function:

Manufacturers’ profit function:

ue to demand uncertainty, this study employed the inventory model of Petrutti & Dada[

18], introducing the inventory level factor z = q−y(a, n). Thus, the quantity of the retailer orders can be simplified as q = y(a, n) +z. When ε

≤ z, it suggests that the demand is less than the ordered quantity, potentially causing overstock. Conversely, when ε

> z, it indicates that the demand is greater than the ordered quantity, possibly leading to stockout. To derive the expected profit equations for manufacturers and retailers, their respective profit functions were integrated, and the random variable that affects demands in the definite expected equation as ε was indicated. The expected inventory and the expected stockout levels are also denoted by H (z) and S (z), respectively.

3.1.1. Stackelberg Equilibrium

The Stackelberg equilibrium model describes a scenario where the dominant party in a channel can influence transaction behaviors throughout the entire channel. In this study, the Stackelberg equilibrium model implies that the manufacturer, as the leader, prioritizes its own profits and sets rules favoring itself. Subsequently, as the follower, the retailer optimizes its profit based on the conditions set by the manufacturer. When both parties adhere to the conditions of the Stackelberg equilibrium model, the manufacturer can first determine the national advertising level n and the cooperative advertising rate t to be implemented by the retailer. Then, guided by these parameters, the retailer can determine its local advertising level a and the quantity of goods to order from the manufacturer q.

The “backward-induction method” was employed to solve the Stackelberg equilibrium, calculating the optimal local advertising level and inventory factor that maximizes the retailer’s profit in the second stage. Subsequently, the retailer’s optimal response in the second stage is integrated into the manufacturer’s profit function in the first stage. As the leader, the manufacturer then determines the most suitable levels of national advertising and the cooperative advertising rate.

The retailer’s objective function is as follows:

The profit function πr is differentiated with respect to the local advertising level a and the inventory level factor z. Setting these derivatives to 0 helps determine the optimal values that maximize the retailer’s profits. The profit function reveals that the retailer’s profit is concave relative to both local advertising and the inventory factor. Therefore, solving and , yields the optimal local advertising level a* and the optimal inventory level z* for retailers, which are as follows:

After putting them into the first-stage manufacturer’s profit function (6), the national advertising level n and the cooperative advertising rate t that can maximize the manufacturer’s profit can be obtained. Substituting these values into the equation, the manufacturer’s objective function can be expressed as follows:

Partial differentiation is performed on the national advertising level n and the cooperative advertising rate t, both of which are set to 0. Thus, and . The maximum cooperative advertising rate and the national advertising level of the manufacturer can be obtained as follows:

Since t ranges between 0 to 1, . This condition implies that cooperative advertising is only feasible when , where t = , and then the t value of is 0.

Since the local advertising level depends on t and n, substituting the national advertising level and cooperative advertising rate back into the local advertising level gives .

3.1.2. Nash Equilibrium

Recent market research spanning two decades has shown that the role of retailers in the current channel is equivalent to and even surpasses that of manufacturers. This is because while manufacturers’ national advertising builds brand awareness, customers ultimately purchase products through retailers. Therefore, various factors, such as product advertising, in-store arrangement, product display, and after-sales service, significantly impact product sales and channel members directly or indirectly. In the Stackelberg equilibrium model, the manufacturer leads while the retailer follows. Conversely, in a scenario where both parties have equal market dominance, decisions are made independently to maximize individual profits without any risk-sharing measures from the manufacturer. This approach excludes considerations for cooperative advertising mechanisms.

The target profit functions of the manufacturer and the retailer are as follows:

Given that the manufacturer and the retailer operate under equal and non-cooperative conditions, the cooperative advertising rate is set to 0. With both parties exerting equal influence in the channel, the two-stage objective function can be differentiated at the same time, and the simultaneous solution for =0, =0, .

After solving the above simultaneous equations, the model’s optimal retailers’ local advertising level a**, optimal manufacturers’ national advertising level n**, and optimal inventory level factor z** when the manufacturer and retailer are under the Nash equilibrium relationship can be derived.

3.2. Single-Manufacturer with Two Competitive Retailers in a Production-Retailing Market Channel

In a market structure comprising only one manufacturer and two competing retailers, as shown in

Figure 2, the sales performance of each retailer depends not only on its own advertising level but also on those of its competitors. This competitive environment often compels retailers to increase their advertising investments to attract more customers.

Market demand is assumed to be related to the manufacturing of

. Following the competitive demand hypothesis proposed by Padmanabhan and Png [

23], the market demand function for these two competing retailers can be expressed as follows:

where α represents the extent to which the retailer’s demand is affected by its own advertising; θ represents the extent to which the retailer is affected by the advertising of the competing retailer. Given that a retailer’s demand is primarily affected by its own advertising efforts, it is assumed that β>θ. Additionally, γ and δ represent the effects of local and national advertising on demands, respectively, while ε

1 and ε

2 are random variables that affect the demands. According to Huang and Li [

10], the local advertising cost is assumed to be a

1 and a

2 for the two retailers, respectively, and n denotes the manufacturer’s national advertising cost. Moreover, it is assumed that n>a>0 is true. Therefore, the profit function for the retailers and the manufacturer can be expressed as follows:

Retailer 1’s profit function: Their respective profit functions were integrated to derive the expected profit equations for the manufacturer and the retailers. The expected stock quantity and expected stockout quantity are replaced by H (z1), H (z2), S (z1), and S (z2), respectively.

Their respective profit functions were integrated to derive the expected profit equations for the manufacturer and the retailers. The expected stock quantity and expected stockout quantity are replaced by H (z1), H (z2), S (z1), and S (z2), respectively.

Retailer 2’s expected profit:

Next, the dominant power dynamics of a single manufacturer and two competing retailers in the channel were examined using both the Stackelberg equilibrium model and the Nash equilibrium model.

3.2.1. Stackelberg Equilibrium for Competing Retailers

The dominant party controls channel transactions in the Stackelberg equilibrium model between manufacturer and retailer. Here, the manufacturer assumes leadership, with the retailer as the follower. Initially, the manufacturer devises a strategy that prioritizes its own benefit, subsequently allowing the retailer to adjust its strategy accordingly.

Under this equilibrium, the manufacturer first determines the national advertising level n and cooperative advertising rate t. Based on these parameters, the retailer can determine its own local advertising level a and the quantity of goods to order q from the manufacturer.

Using the backward induction method inherent to the Stackelberg equilibrium, the problem is solved. Starting from the second stage, the retailer response equation computes the local advertising and inventory factors that could maximize the retailer’s profit. These decisions are then incorporated into the manufacturer’s first-stage profit function for optimization.

As the leader in this model, the manufacturer determines the optimal level of national advertising and cooperative advertising rate. The profit functions of both parties are as follows:

To find the local advertising level and inventory level factor that can help retailers maximize their profits, the advertising level and inventory level factors in the retailers’ expected profit equation were differentiated and set to 0. Therefore, the optimal local advertising level a and the optimal inventory level z for retailers can be obtained.

After determining the optimal local advertising level a and inventory level z for retailers, these values are incorporated into the first-stage manufacturer profit equation to ascertain the optimal national advertising level n and cooperative advertising participation rate t, maximizing the manufacturer’s profits. This involves differentiating the manufacturer’s cooperative advertising rate t and the national advertising level n and making them equal to 0. By doing so, the cooperative advertising rate that helps the manufacturer maximize profits and the optimal national advertising level can be obtained.

3.2.2. Nash Equilibrium for Competing Retailers

When the manufacturer and the two competing retailers have equal market power, each member in the channel focuses solely on maximizing their own profits. No party holds a stronger position, and the manufacturer does not share risks with the retailers. Therefore, the cooperative advertising rate t is 0, and retailers make decisions independently without needing to conform to the conditions set by the manufacturer. In this model of equal status within the channel, the profits of manufacturers and retailers must all be taken into account. The profit functions are as follows:

In addition, by differentiating the two-stage objective function, the optimal solutions for the two-stage Nash equilibrium model can be obtained as follows:

After solving the above simultaneous equations, the model’s optimal solution for and when the manufacturer and retailer are under the Nash equilibrium can be derived.

4. Results and Sensitivity Analysis

The hypothesis and solutions proposed by Huang and Li [

10] are applied to the proposed model to validate its rationality. Given a single retailer and two competing retailers, changes in profitability among channel members under the Stackelberg equilibrium and Nash equilibrium are compared. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to analyze and discuss significant parameters.

It is assumed that at the beginning of the selling period, the retailer orders the quantity of products needed for the entire selling period from the manufacturer at a unit price. Random demands are assumed to follow a normal distribution

, and are influenced by seasonal probabilities of customer purchase intentions. As a result, retailers may encounter issues of stock insufficiency or stock out. During the selling period, insufficient quantities of goods may result in a reputation loss of 250 per unit. Conversely, at the end of the selling period, unsold goods retain a value of 200 per unit, which may diminish due to seasonal effects. The manufacturer is assumed to profit 400 per unit sold, while the retailer profits 100 per unit sold. The main demand in the market is 30, with an advertising factor influencing market demand set at 10. The advertising effects of the manufacturer and the retailer are

, respectively. According to the hypothesis [

10], advertising costs are scaled by multipliers of 50 and 5,000 for all respective levels. All parameters and demand functions are defined as follows:

4.1. Single-Manufacturer Single-Retailer Channel

Table 1(a) illustrates the outcomes under the Stackelberg equilibrium relationship where the manufacturer leads and does not engage in cooperative advertising. Here, the manufacturer and the retailer earn profits of 6,403.11 and 958.99, respectively. However, with the increase of the cooperative advertising rate t, the manufacturer’s expected profit peaks at 6,869.39 when t=0.714286. This demonstrates that cooperative advertising can significantly enhance profits for manufacturers and retailers in the single-manufacturer single-retailer channel. Alternatively, cooperative advertising benefits retailers by improving advertising quality and increasing profits through shared costs. However, manufacturers must carefully evaluate whether cost-sharing impacts their actual profits shown as Table 1(b).

Figure 3(a) depicts the non-linear nature of the manufacturer’s profit curve. Beyond

t=0.714286, the curve declines rapidly. This decline occurs because while cooperative advertising boosts market demand and increases retail orders, an exponential relationship exists between demand and the effectiveness of a retailer’s local advertising level. Therefore, when the cooperative advertising rate exceeds 0.714286, the manufacturer’s advertising subsidy to retailers escalates, potentially surpassing the profits generated.

Figure 3(b) indicates an increasing retailer preference for higher cooperative advertising rates. Greater willingness from manufacturers to share advertising costs results in higher retailer profits by enhancing advertising levels.

Figure 4 demonstrates that higher seasonal probabilities adversely affect profits due to the increased likelihood of stockouts, leading to reputation costs and reduced profitability.

Without advertising cooperation, the cooperative advertising rate is 0. Table 2(a) displays the optimal decision under Nash equilibrium conditions. Table 2(b) shows that when retailers and manufacturers operate under the Stackelberg equilibrium led by the manufacturer, sharing advertising costs can prompt retailers to increase their local advertising levels, thus increasing the market demand. Numerical analysis indicates that profits under the Stackelberg equilibrium with cooperative advertising surpass those under the Nash equilibrium, where both parties have equal status.

In a Stackelberg equilibrium, the manufacturer, as the leader, aims to elevate profits through a cooperative advertising mechanism, which benefits both parties. Conversely, in the Nash equilibrium relationship, where both parties are equal, the profits for both the manufacturer and retailer are lower than the optimal profits under the Stackelberg equilibrium. Numerical analysis demonstrates that optimal profits are achieved under Stackelberg equilibrium. However, this may also vary depending on specific circumstances. As shown in

Figure 5(a), when the marginal profit of retailers exceeds 183, retailers may prefer the Nash equilibrium. This is because higher marginal profits make retailers less inclined to be constrained by the manufacturer and more likely to seek independent, optimal decisions.

Figure 5(b) illustrates that when the retailer’s marginal profit exceeds 266, the manufacturer’s profit increase from cooperative advertising fails to cover the retailer’s advertising costs. Therefore, higher retailer marginal profit leads to lower cooperative advertising rates.

Figure 5(c) shows that when the manufacturer offers cooperative advertising, it aims to lead the production and sales behavior under the Stackelberg equilibrium conditions to maximize its own profits.

4.2. Single-Manufacturer with Two Competitive Retailers Channel

When a manufacturer faces two competing retailers, it is assumed that the manufacturer can make a profit of 400 on each item sold, Retailer 1 can make a profit of 100 on each item sold, and Retailer 2 can make a profit of 80 per item sold. The main demand in the market is 30, the advertising factor affecting the market demand is 10, the advertising impact factor of the competing retailer is 5, and the advertising effects of the manufacturer and the retailer are , respectively. According to Huang and Li (2001), the multipliers of the respective advertising levels can be set as 50 and 5000. All parameters and demand functions are set as follows:As shown in Table 3(a), under the Stackelberg equilibrium with the manufacturer as the leader and without cooperative advertising, the profits of the manufacturer, Retailer 1, and Retailer 2 are 18,041.22, 1,480.73, 761.49, respectively. However, with the increase of the cooperative advertising rate t, the manufacturer’s expected profit reaches a maximum of 18143.8767 at t=0.42244. Therefore, cooperative advertising can indeed bring higher profits for manufacturers and retailers.

Figure 6(a) illustrates that the manufacturer’s profit does not continuously increase. When the cooperative advertising rate is between 0 and 0.42244, there is only a slight increase in profit. This is because the cooperative advertising mechanism provided by the manufacturer offers limited incentives for competing retailers to increase their order quantity. Consequently, the manufacturer’s profit does not increase significantly. However, there is an exponential correlation between demands and the impact of retailers’ local advertising levels. When the cooperative advertising rate exceeds 0.42244, the advertising cost that the manufacturer incurs to subsidize the retailers increases substantially, potentially outweighing the manufacturer’s profit and causing it to decline.

The profits of Retailer 1 and Retailer 2 positively correlate with the cooperative advertising rate. If the manufacturer shares more advertising costs, retailers’ profits increase. As shown in

Figure 6(b), cooperative advertising provided by the manufacturer is wholly beneficial to the retailers, enhancing their advertising levels and profits as the manufacturer shares the advertising cost. However, this may not be equally beneficial for the manufacturer, which must consider whether sharing advertising costs effectively enhances its profits, as shown in Table 3(b).

Without advertising cooperation, the cooperative advertising rate is 0. Table 4(a) shows the optimal decision under the Nash equilibrium conditions. Table 4(b) shows that when retailers and manufacturers are in the Stackelberg equilibrium led by the manufacturer, the retailers may increase their local advertising level if the manufacturer is willing to share the advertising cost of the retailers, thereby increasing market demand. The profit under the Stackelberg equilibrium condition with the cooperative advertising by both parties is higher than under the Nash equilibrium condition, where the parties have equal status.

4.3. Comparison Under the Conditions of a Single Retailer and Competing Retailers

When the marginal profit of a single retailer is the same as that in a channel containing two competing retailers , sensitivity analysis can be used to compare the differences between the two scenarios. Table 5 indicate that the higher the marginal profit of the retailer, the lower the cooperative advertising rate and the national advertising level set by the manufacturer. Therefore, under the condition of competing retailers, when the competitor’s marginal profit becomes larger, the retailer’s own profit is affected and decreases.

When the marginal profits of two competing retailers in a channel are equal, and they match the condition of a single retailer (), the manufacturer of the single retailer will be willing to offer a larger cooperative advertising rate. Conversely, when the marginal profits of two competing retailers are equal and half of the marginal profit under the condition of a single retailer (), the cooperative advertising rate the manufacturer provides to the competing retailers will be the same as that provided under the single retailer condition.

5. Conclusions

Given market demand with seasonality, this paper has examined how advertising affects the profit of retailers and manufacturers in the co-operation relationship. We explored how the channel is enhanced through the cooperative advertising provided by the manufacturer and the retailer. The research indicates that advertising cooperation can improve both parties’ advertising levels and profits. For retailers, the cooperative advertising provided by the manufacturer is entirely beneficial, as it not only enhances the level of advertising but also increases the profits by sharing the advertising cost. However, the same cannot be said for the manufacturer. The manufacturer must consider whether sharing advertising costs will effectively enhance its profits.

Specifically, in the single-manufacturer single-retailer channel, cooperative advertising benefits retailers by improving advertising quality and increasing profits through shared costs. However, manufacturers must carefully evaluate whether cost-sharing impacts their actual profits. In a Stackelberg equilibrium, the manufacturer, as the leader, aims to elevate profits through a cooperative advertising mechanism, which benefits both parties. Conversely, in the Nash equilibrium relationship, where both parties are equal, the profits for both the manufacturer and retailer are lower than the optimal profits under the Stackelberg equilibrium. One the other hand, in the single-manufacturer 2-competitive retailer of a production-retailing market channel, the profit under the Stackelberg equilibrium condition with the cooperative advertising by both parties is higher than under the Nash equilibrium condition, where the parties have equal status. Cooperative advertising provided by the manufacturer is wholly beneficial to the retailers, enhancing their advertising levels and profits as the manufacturer shares the advertising cost. However, this may not be equally beneficial for the manufacturer, which must consider whether sharing advertising costs effectively enhances its profits.

In the modern market, the variety of seasonal goods and the importance of retailers is becoming more pronounced. Under different leadership conditions, whether the retailer or the manufacturer is the leader, the decisions made by each member of the channel vary. Therefore, the mechanism of cooperation becomes crucial (Li et al., 2022). When there is cooperation, the advertising level can be improved, leading to significantly greater profits than those without cooperation. Therefore, finding appropriate methods for cooperation is essential to achieve a win-win situation.

References

- Yang, W., Wu, Y., Gou, Q., & Zhang, W. Coopetition strategies in supply chains with strategic customers. Production and Operations Management, 2023, 32(1), 319-334.

- Zhang, J., Cao, Q., & He, X. Manufacturer encroachment with advertising. Omega, 2020, 91, 102013.

- Young, R. F. and Greyser, R.F.S.A. Managing Cooperative Advertising: A Strategic Approach. Lexington Books, Lexington, MA., 1983.

- Karray, S. and Zaccour, G. Could cooperative advertising be a manufacturer’s counterstrategy to store brands”, Journal of Business Research, 2006, 59 (9), 1008-1015.

- Karray, S., Martin-Herran, G., & Sigué, S. P. Cooperative advertising in competing supply chains and the long-term effects of retail advertising. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 2022, 73(10), 2242-2260.

- Su, Rung-Hung, Tseng, Tse-Min and Chun Lin Integrated Profitability Evaluation for a Newsboy-Type Product in Own Brand Manufacturers. Mathematics, 2024, 12(4), 533.

- Zhang, T., Guo, X., Hu, J., & Wang, N. Cooperative advertising models under different channel power structure. Annals of Operations Research, 2020, 291, 1103-1125.

- Li, J., Ou, J., & Cao, B. The roles of cooperative advertising and endogenous online price discount in a dual-channel supply chain. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 2023, 176, 108980.

- Jorgensen, S.S.P. Sigué and Zaccour, G. Dynamic cooperative advertising in a channel, Journal of Retailing, 2000, 76(1), 71-92.

- Huang, Z., and Li, S.X. Co-Op advertising models in a manufacturing-retailing supply chain: a game theory approach. European Journal of Operational Research, 2001, 135, 527-544.

- Krishnan, H., Kapuscinski, R., and Butz, D.A. Coordinating contracts for decentralized supply chains with retailer promotional effort, Management Science, 2004, 50(1), 48-63.

- Maciel, A. F., & Fischer, E. Collaborative market driving: How peer firms can develop markets through collective action. Journal of Marketing, 2020, 84(5), 41-59.

- Zhang, T.; Guo, X.; Hu, J.; Wang, N. Cooperative advertising models under different channel power structure. 2020, 291, 1103-1125.

- Wolters, J., & Huchzermeier, A. Joint in-season and out-of-season promotion demand forecasting in a retail environment. Journal of Retailing, 2021, 97(4), 726-745.

- Daniel Muñoz Rojas, Jairo R. Montoya-Torres and Diana M. Ayala Valderrama. A Data-Driven Framework for Agri-Food Supply Chains: A Case Study on Inventory Optimization in Colombian Potatoes Management. Logistics, 2025, 9(4), 164.

- Jadidi, O., Jaber, M. Y., Zolfaghri, S., Pinto, R., & Firouzi, F. Dynamic pricing and lot sizing for a newsvendor problem with supplier selection, quantity discounts, and limited supply capacity. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 2021,154, 107113.

- Su, Rung-Hung Hou, Chia-Ding and Lee, Jou-Yu. Obtaining Conservative Estimates of Integrated Profitability for a Single-Period Product in an Own-Branding-and-Manufacturing Enterprise with Multiple Owned Channels. Mathematics, 2024, 12(13), 2080.

- Petruzzi, Nicholas C. and Dada Maqbool. Pricing and the newsvendor problem: A review with extensions, Operation Research, 1999, 47(2), 183-194.

- Andersen, T. J., & Bering, S. Integrating distribution, sales and services in manufacturing: a comparative case study. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 2023, 43(10), 1489-1519.

- Apornak, A., & Keramati, A. Pricing and cooperative advertising decisions in a two-echelon dual-channel supply chain. International Journal of Operational Research, 2020, 39(3), 306-324.

- Choi, S. Price competition in a channel structure with a common retailer, Marketing Science, 1991, 10(4), 271-296.

- Bitran, G. and Mondschein, S. A Comparative Analysis of Decision Making Procedures in the Catalog Sales Industry. European Management Journal, 1997, 15, 105-116.

- Padmanabhan, V. and Png, I.P.L. Manufacturer’s returns policies and retail competition, Marketing Science, 1997, 16(1), 81-94.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).