1. Introduction

Globally, the number of patients receiving renal replacement therapy (RRT) due to chronic kidney disease is projected to double from approximately 2.5 million in 2017 to 5.4 million by 2030 [

1]. Among available RRT modalities, hemodialysis (HD) remains the most utilized worldwide, accounting for 77.3% of all treatments [

2]. In South Korea, the mean age of patients with end-stage kidney disease is 66.8 years, and individuals aged 65 years or older comprise 59.8% of the dialysis population [

3]. As the dialysis population continues to age and present with increasing numbers of comorbidities, nurses working in HD units are required to provide greater amounts of nursing care within limited working hours, particularly for older patients with complex care needs [

4].

HD nurses are positioned on the frontline of care for patients with chronic kidney disease and are responsible for meeting the needs of patients who undergo prolonged treatment sessions, experience high disease severity, and often demonstrate heightened emotional sensitivity. Consequently, these nurses are inherently vulnerable to burnout [

5]. In addition to the burden of caring for older patients with chronic illnesses, nurses in HD units are required to acquire specialized technical skills and advanced professional knowledge related to dialysis machinery and water treatment systems—competencies that are not typically required in other nursing units [

6]. These distinctive job characteristics further increase the likelihood of experiencing burnout [

7,

8].

Burnout refers to a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion and depletion that results from repeated exposure to excessive occupational stressors [

9]. Nurses experiencing burnout exhibit reduced empathic capacity toward patients due to emotional exhaustion, which in turn diminishes the quality of nurse–patient interactions [

10]. Empirical evidence has demonstrated that nurse burnout adversely affects patient outcomes by lowering the quality of care and increasing the risk of patient safety incidents [

11,

12]. Accordingly, developing effective strategies to reduce burnout among nurses is urgent.

HD nurses, who are required to manage heavy workloads and respond to emergencies, must go beyond executing technical procedures and engage in continuous therapeutic interactions to establish caring relationships with patients. Given the repetitive and long-term nature of HD treatment, nurses’ therapeutic interactions and caring attitudes can substantially influence patients’ treatment experiences and clinical trajectories [

13,

14]. In this context, interpersonal caring behavior—defined as attentively listening to and accepting others, providing praise and encouragement, recognizing changes in others, and accompanying them through their experiences [

13]—can be regarded as a positive and essential nursing practice when caring for older patients undergoing chronic dialysis. The concept of interpersonal caring was originally developed in Korea as a compassion-based therapeutic caring theory for individuals with mental illness [

15].

Interpersonal caring behavior constitutes a core concept in nursing practice and reflects the nurse’s ability to understand others’ emotional states and provide necessary support through empathy, consideration, and effective communication [

16]. As such, it serves as a meaningful indicator of qualitative improvement in nursing care [

13]. Previous studies have reported that interpersonal caring enhances patients’ sense of self-worth and self-esteem, fosters personal growth and rediscovery, and improves self-management abilities in daily life [

15]. Notably, patients undergoing HD are particularly vulnerable to depression, helplessness, and low self-esteem due to their long-term dependence on dialysis machines and the chronic nature of their condition [

17,

18]. Therefore, interpersonal caring behavior represents an essential professional attribute for nurses caring for emotionally vulnerable dialysis patients. Empirical evidence indicates that patients who receive interpersonal caring from nurses experience positive outcomes mediated by enhanced self-esteem [

15].

Meanwhile, HD units are characterized by the potential for sudden patient deterioration and emergencies, necessitating prompt clinical judgment and effective decision-making [

19,

20]. In such contexts, job autonomy—defined as the degree to which nurses can adjust work schedules and methods and participate in decision-making according to patient conditions—is considered a critical organizational factor that enhances the effectiveness of nursing care in HD units [

21,

22]. Job autonomy refers to the extent to which nurses can independently perform their professional duties [

23,

24]. Higher levels of job autonomy have been associated with increased job satisfaction [

25,

26,

27], which in turn contributes to improved quality of interactions with patients [

10].

Although direct comparisons are limited due to the absence of studies explicitly examining the mediating effect of job autonomy, autonomy has been identified as a fundamental component of professional nursing practice [

28]. Job autonomy enables nurses to develop and implement care plans based on professional judgment and to actively participate in the patient care process [

23,

24,

29]. In environments where job autonomy is supported, nurses can engage proactively in clinical decision-making, thereby enhancing both nursing performance and the effectiveness of patient care [

30,

31,

32].

Empirical studies have shown that nursing environments characterized by high autonomy are associated with better evaluations of care quality and higher levels of patient safety practices [

33,

34]. These findings suggest that autonomous nurses are better equipped to respond promptly and appropriately to changes in patient conditions [

32]. Moreover, nurses with greater autonomy can provide flexible, individualized care based on patients’ unique needs and emotional states, thereby potentially enhancing the quality of caring behaviors [

35,

36].

Job autonomy has also been shown to be closely related to nurses’ emotional and occupational experiences [

37,

38,

39]. Nurses working in autonomy-supportive environments are more likely to maintain a strong professional identity, which contributes to reduced job stress and increased job satisfaction [

40,

41,

42]. Conversely, autonomy-restricted environments tend to emphasize repetitive, directive-based tasks, thereby increasing job burden and the likelihood of burnout [

43,

44,

45]. From this perspective, job autonomy may function as a buffering or moderating mechanism in the process through which nurses’ emotional and occupational burdens are translated into nursing performance outcomes [

46]. Even among nurses experiencing burnout, the presence of job autonomy may help sustain professional judgment and caring behaviors [

34,

44,

47], suggesting that autonomy plays a critical role in the relationship between burnout and nursing outcomes [

48].

Accordingly, job autonomy should be understood not merely as an individual competency, but as a key organizational variable that influences the quality of patient care and overall nursing performance. Clarifying the role of job autonomy in the relationship between nurses’ burnout and caring behaviors may contribute to improvements in nursing practice and, ultimately, to enhanced organizational performance. To date, research on HD nurses has primarily focused on burnout [

49], job stress [

50], and job satisfaction [

51], while limited attention has been given to factors that may enhance caring behaviors and clinical decision-making. Therefore, the present study aims to provide foundational evidence for reducing burnout and enhancing interpersonal caring behavior and job autonomy among HD nurses working in specialized care environments, thereby contributing to improved organizational outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.1.1. Study Design

This study employed a cross-sectional descriptive design to examine the relationship between burnout and interpersonal caring behavior among nurses working in HD units and to test the mediating effect of job autonomy in this relationship.

2.1.2. Participants

The participants were nurses working in HD units at 17 medical institutions located in Gyeongsangbuk-do (P city, G city, and Y county), one medical institution in Busan Metropolitan City, and one medical institution in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) registered nurses aged 19 years or older, (2) currently working in a HD unit, (3) having at least six months of work experience in a HD unit, and (4) understanding the purpose of the study and voluntarily agreeing to participate. Nurses who were on leave during the study period or who had difficulty reading, understanding, or completing the questionnaire were excluded.

The required sample size was calculated using G*Power version 3.1. Based on multiple regression analysis with a significance level (α) of .05, statistical power of .95, a medium effect size (f² = .15), and five predictor variables, as informed by a previous study [

14], the minimum required sample size was 138 participants. To account for potential incomplete responses or attrition, 202 questionnaires were distributed. After excluding one questionnaire with incomplete responses, 201 questionnaires were included in the final analysis.

2.2. Study Instruments

2.2.1. General Characteristics

Participants’ general characteristics included gender, age, highest level of education, job position, total clinical experience, length of experience in HD units, work schedule, and type of employing institution. Age, total clinical experience, and HD unit experience were collected as continuous variables.

2.2.2. Burnout

Burnout refers to a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion experienced by nurses because of prolonged exposure to occupational stress. In this study, burnout was measured using the Burnout Scale for General Hospital Nurses (BS-GHN) developed by Lee and Shin [

9].

The BS-GHN consists of 26 items encompassing four subdomains: professional quality of life (10 items), work environment ease (6 items), job satisfaction (6 items), and negative emotions (4 items). Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“strongly agree”). Total scores range from 26 to 104, with higher scores indicating higher levels of burnout.

At the time of scale development, the internal consistency reliability was reported as Cronbach’s α = .91. In the present study, the overall reliability of the instrument was Cronbach’s α = .86.

2.2.3. Job Autonomy

Job autonomy refers to the degree to which nurses can independently control their work schedules, methods of task performance, and decision-making processes during job execution. Job autonomy was measured using the job autonomy subscale of the Work Design Questionnaire originally developed by Morgeson and Humphrey [

52] and subsequently adapted to the Korean context by Ko and Yoo [

21].

This instrument comprises nine items across three subdomains: work scheduling autonomy, decision-making autonomy, and work methods autonomy, with three items per subdomain. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), with higher scores indicating greater job autonomy.

The internal consistency reliability reported by Ko and Yoo [

21] was Cronbach’s α = .94, and the reliability in the present study was Cronbach’s α = .93.

2.2.4. Interpersonal Caring Behavior

Interpersonal caring behavior refers to nursing behaviors grounded in empathy, respect, acceptance, emotional support, and therapeutic relationships during interactions with patients. Interpersonal caring behavior was measured using the Korean Interpersonal Caring Behavior Scale (ICBS) developed by Lee et al. [

13].

The ICBS consists of 32 items across five subdomains: active listening (10 items), acceptance (8 items), praising (7 items), noticing (5 items), and accompanying (5 items). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), with higher scores indicating higher levels of interpersonal caring behavior.

The original study reported an internal consistency reliability of Cronbach’s α = .93, and the overall reliability in the present study was Cronbach’s α = .94.

2.3. Data Collection

Data were collected from October to December 2025. Before data collection, ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the researcher’s affiliated institution (IRB No. 0749-251008-HR-084-01). Following IRB approval, the researcher contacted nurse managers of the HD units at participating institutions to explain the purpose and procedures of the study and to obtain cooperation.

Data were collected using a self-administered structured questionnaire, which participants completed independently. All participants received written information describing the study’s purpose, procedures, anonymity, voluntary participation, and the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Only participants who provided written informed consent were included in the study.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0. Participants’ general characteristics were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations. Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among burnout, job autonomy, and interpersonal caring behavior.

Differences in the main variables according to general characteristics were examined using independent-samples t-tests or one-way analysis of variance, as appropriate. When significant differences were identified, Scheffé’s post hoc test was applied.

To test the mediating effect of job autonomy on the relationship between burnout and interpersonal caring behavior among HD nurses, Hayes’ PROCESS macro (version 4.2), Model 4, was employed. The significance of the indirect effect was evaluated using bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. A mediating effect was considered statistically significant when the CI did not include zero. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and the level of significance was set at p < .05.

3. Results

The general characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1. Among the 201 participants, 98.5% (n = 198) were female. The mean age was 40.23±9.53 years. Regarding educational level, 49.8% (n = 100) had completed a university degree, representing the largest proportion.

In terms of job position, 75.6% (n = 152) were staff nurses. The mean length of total clinical experience was 13.96±9.35 years, while the mean length of experience in HD units was 7.76±7.17 years. With respect to work schedule, 53.2% (n = 107) worked rotating shifts or other non-fixed schedules. Regarding the type of employing institution, 40.3% (n = 81) were employed at dialysis-specialized hospitals.

3.2. Levels of Burnout, Interpersonal Caring Behavior, and Job Autonomy

The levels of burnout, interpersonal caring behavior, and job autonomy are presented in

Table 2. The mean burnout score among participants was 2.33±0.31. Regarding burnout subdomains, the mean scores were 2.57±0.46 for professional quality of life, 2.21±0.32 for work environment ease, 2.38±0.40 for job satisfaction, and 1.85±0.46 for negative emotions.

The mean score for interpersonal caring behavior was 3.67±0.43. Among its subdomains, active listening had the highest mean score (3.9±0.44), followed by acceptance (3.65±0.46), praising (3.58±0.56), noticing (3.58±0.56), and accompanying (3.06±0.80).

The mean level of job autonomy was 3.18±0.71. With respect to job autonomy subdomains, the mean scores were 3.29±0.82 for work scheduling autonomy, 3.03±0.80 for decision-making autonomy, and 3.22±0.78 for work methods autonomy.

3.3. Differences in Interpersonal Caring Behavior According to General Characteristics

Differences in interpersonal caring behavior according to participants’ general characteristics are presented in

Table 3. Interpersonal caring behavior differed significantly with age, with higher levels observed among nurses aged 50 years or older (F= 8.78, p< .001). With respect to job position, nurses holding positions of charge nurse or higher demonstrated significantly higher levels of interpersonal caring behavior (F= 4.91, p= .008).

Interpersonal caring behavior also differed according to the length of clinical experience. Nurses with 20 years or more of total clinical experience reported higher levels of interpersonal caring behavior (F= 3.27, p= .022). Similarly, a significant difference was observed based on experience in HD units, with nurses who had 12 years or more of HD unit experience showing higher levels of interpersonal caring behavior (F= 3.19, p= .025).

3.4. Correlations Among Burnout, Interpersonal Caring Behavior, and Job Autonomy

The correlations among burnout, interpersonal caring behavior, and job autonomy are presented in

Table 4. Interpersonal caring behavior showed a significant negative correlation with burnout (r= −.34, p< .001) and a significant positive correlation with job autonomy (r= .35, p< .001).

Job autonomy also significantly negatively correlated with burnout (r= −.40, p< .001).

3.5. Mediating Effect of Job Autonomy on the Relationship Between Burnout and Interpersonal Caring Behavior

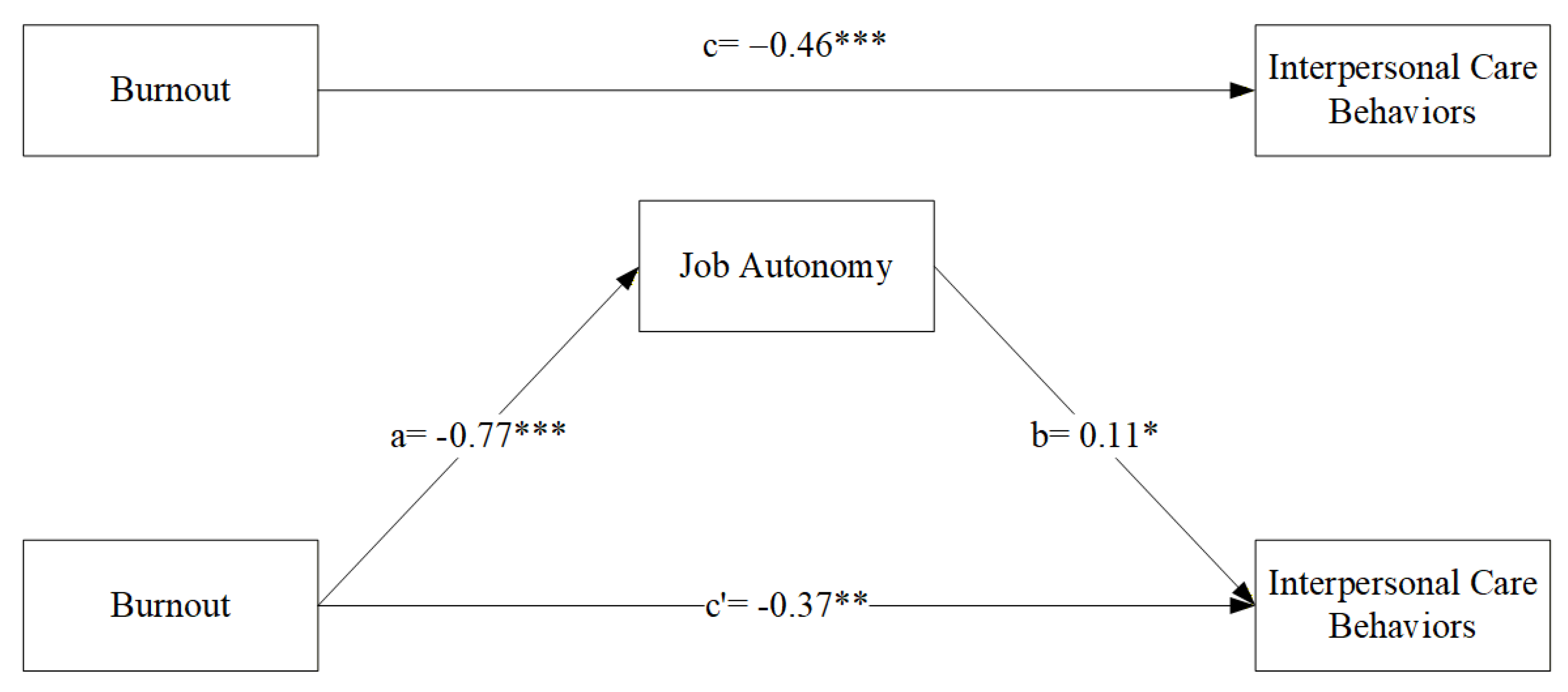

This study examined the mediating role of job autonomy in the relationship between burnout and interpersonal caring behavior among nurses working in HD units (

Table 5,

Figure 1). Variables related to interpersonal caring behavior, including age, job position, total clinical experience, and HD unit experience, were included as covariates in the analysis. Mediation analysis was conducted using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 4).

The results indicated that burnout had a significant negative effect on job autonomy (β= −0.77, SE = 0.14, p< .001), indicating that higher levels of burnout were associated with significantly lower levels of job autonomy (Path a). In addition, job autonomy exerted a significant positive effect on interpersonal caring behavior (β= 0.11, SE = 0.05, p= .028), suggesting that higher job autonomy was associated with higher levels of interpersonal caring behavior (Path b).

The total effect of burnout on interpersonal caring behavior was statistically significant (β= −0.46, SE = 0.10, p< .001). After including job autonomy as a mediator, the direct effect of burnout on interpersonal caring behavior remained significant (β= −0.37, SE = 0.10, p= .001) (Path c′), indicating a partial mediating effect of job autonomy on the relationship between burnout and interpersonal caring behavior (

Table 5).

To test the significance of the indirect effect, bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples was performed. The indirect effect of burnout on interpersonal caring behavior through job autonomy was −0.062, and the 95% CI ranged from −0.124 to −0.005, which did not include zero, indicating statistical significance (

Table 6). These findings demonstrate that job autonomy serves as a significant mediator in the relationship between burnout and interpersonal caring behavior among HD nurses.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between burnout and interpersonal caring behaviors among HD unit nurses and verified the mediating effect of job autonomy within this relationship. The results indicated that burnout had a direct negative effect on interpersonal caring behaviors. Furthermore, burnout indirectly affected interpersonal caring behaviors by reducing job autonomy. Additionally, job autonomy was confirmed as a significant variable that partially mediates the relationship between burnout and interpersonal caring behaviors.

The finding that higher levels of burnout significantly decreased interpersonal caring behaviors among HD nurses is consistent with prior research indicating that nurse burnout compromises the quality of care and therapeutic interactions with patients. Maslach and Leiter defined burnout as a state of accumulated emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, noting that nurses in this state struggle to form empathetic relationships with patients [

53]. Domestic studies also support these findings, showing that nurse burnout significantly reduces patient-centered nursing, empathetic communication, and the performance of caring behaviors [

54]. Synthesizing the present results with prior literature confirms that burnout in HD nurses acts as a critical factor inhibiting relationship-based nursing, such as interpersonal caring behaviors. Therefore, to enhance interpersonal caring behaviors among HD nurses, systematic organizational interventions aimed at reducing burnout must be prioritized. From a nursing management perspective, improvements in the work environment and staffing that reflect the specific characteristics of HD units are necessary.

The HD unit is a specialized environment requiring long-term, repetitive interactions with patients suffering from chronic diseases. In such a setting, the accumulation of emotional burnout may have a more pronounced impact on interpersonal caring behaviors. This context may explain the relatively strong direct effect of burnout on interpersonal caring behaviors observed in this study.

Regarding the level of interpersonal caring behaviors among HD nurses, the mean score was 3.67±0.43 out of 5. The level of interpersonal caring behaviors was significantly higher among nurses aged 50 or older, those holding the position of head nurse or higher, those with over 20 years of clinical experience, and those with over 12 years of HD experience. Given the unique clinical environment of the HD unit, where nurses must perform relationship-based care through long-term repetitive interactions, these results suggest that interpersonal caring behaviors are maintained at a relatively high level.

Although direct comparisons are limited due to a scarcity of studies verifying the importance of interpersonal caring behaviors specifically in HD nurses, prior research on clinical nurses reports that higher age and clinical experience correlate with higher levels of interpersonal caring behaviors and empathetic care performance. Validation studies of the Korean version of the ICBS also conceptualized interpersonal caring behaviors as a relationship-centered care competency acquired through clinical experience, supporting the finding of higher scores in the older and more experienced nurse groups in this study [

13].

Furthermore, studies on clinical nurses have reported that interpersonal caring behaviors are closely related not only to individual care competencies but also to clinical experience, job satisfaction, and emotional stability [

55]. In particular, Seo et al. (2017) [

56] noted that as clinical experience accumulates, nurses become more sensitive to patients’ emotional states and non-verbal responses, effectively linking this awareness to caring behaviors—a trend similar to the results of this study.

Synthesizing these findings, interpersonal caring behaviors should be understood not merely as traits formed by personal disposition or short-term education, but as professional competencies strengthened through continuous practice and the accumulation of clinical experience. The notably high levels of caring behaviors among those in head nurse positions or higher suggest that managerial nurses may serve as role models by practicing and coordinating the value of care within the organization. Therefore, to promote interpersonal caring behaviors among HD nurses, step-by-step care competency education for new and less experienced nurses is required, alongside systematic support to share and disseminate the experience and caring skills of highly experienced nurses at the organizational level.

In this study, job autonomy demonstrated a partial mediating effect on the relationship between burnout and interpersonal caring behaviors. This implies that job autonomy can act as a protective factor that buffers nurses’ emotional burden and maintains or enhances the quality of caring behaviors. These results align with previous studies reporting that higher job autonomy strengthens nurses’ job satisfaction and professional identity, thereby improving the quality of patient care [

57,

58]. While few studies have directly verified the mediating effect of job autonomy in the relationship between burnout and interpersonal caring behaviors specifically for HD nurses, studies on general ward nurses have reported that job autonomy acts as a mediator or moderator between job stress and nursing outcomes [

59,

60]. Considering these precedents, this study is significant as it empirically extends the role of job autonomy to the specialized clinical environment of the HD unit.

However, the magnitude of the effect of job autonomy on interpersonal caring behaviors was relatively small compared to the direct effect of burnout. This may be interpreted as interpersonal caring behaviors being influenced by a diverse range of factors beyond individual emotional states, including organizational culture, team cooperation, staffing, and patient characteristics. In other words, job autonomy should be understood as a factor that partially buffers the negative impact of burnout rather than completely offsetting it.

This study has several limitations. First, the use of a cross-sectional design with convenience sampling limits the ability to clearly establish causal relationships between variables. Future studies should employ longitudinal or interventional designs to more precisely verify the causal pathways between burnout, job autonomy, and interpersonal caring behaviors. Second, data were collected from HD nurses in medical institutions within specific regions, so caution is needed when generalizing the results to the entire population of HD nurses. Third, the use of self-report questionnaires cannot exclude social desirability bias or subjective perception. Therefore, future studies should utilize multi-source data collection methods, including observational data or manager evaluations, to strengthen validity. Finally, this study established only job autonomy as a mediator and did not include other organizational factors such as organizational culture, teamwork, or leadership. Future research should employ expanded models, including these factors, to more comprehensively explain relationship-based care among HD nurses.

Despite these limitations, this study holds academic significance as it empirically identified the relationship between burnout and interpersonal caring behaviors in HD nurses and was the first to verify the mediating effect of job autonomy in this relationship. Furthermore, this study provides evidence for nursing management and practice improvements by suggesting that organizational strategies, including the enhancement of job autonomy and individual approaches for burnout reduction, can contribute to promoting interpersonal caring behaviors. Specifically, in the HD environment where repetitive and long-term interactions are required, enhancing job autonomy may serve as a core strategy to respect nurses’ professional judgment and improve the quality of relationship-based care.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the relationship between burnout and interpersonal caring behaviors among HD unit nurses and verified the mediating effect of job autonomy in this relationship. The study found that burnout negatively affects interpersonal caring behaviors both directly and indirectly by lowering job autonomy. Job autonomy was confirmed to be a variable that partially mediates the relationship between burnout and interpersonal caring behaviors.

These findings suggest that while the interpersonal caring behaviors of HD nurses are significantly influenced by the emotional factor of burnout, they can also be regulated by environmental and organizational factors such as job autonomy. This implies that while job autonomy cannot completely eliminate the negative effects of burnout, it can function as a protective factor to partially buffer the decline in interpersonal caring behaviors.

In conclusion, to improve the quality of care provided to patients by HD nurses, it is critical to not only implement individual and organizational interventions to reduce burnout but also to create a work environment where nurses can autonomously judge and regulate their work.

Particularly in HD units, which require repetitive and continuous interaction between nurses and patients, strengthening job autonomy contributes to the enhancement of interpersonal caring behaviors. Future research is needed to comprehensively identify factors affecting interpersonal caring behaviors in HD nurses through expanded models incorporating various organizational factors, and to verify the effectiveness of specific intervention strategies designed to strengthen job autonomy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, design, methodology, and survey, S.Y.P. and J.L. SHIM.; Writing - Original Draft, formal analysis, Software, and Visualization, S.Y.P.; Validation, Writing—Review & Editing, J.L. SHIM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1A2C2092976).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the research institution (IRB approval number: DUG IRB 20230010) prior to data collection.

Informed Consent Statement

The candidates were informed about the purpose, details, and data collection method of the study and the fact that personal information will be protected and the contents of the survey will be held confidential and used only for the purpose of this study. The study was conducted with those who submitted an informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the nurses who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| BS-GHN |

Burnout Scale for General Hospital Nurses |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| ICBS |

Interpersonal Caring Behavior Scale |

| HD |

Hemodialysis |

| KSN |

Korean Society of Nephrology |

| LLCI |

Lower limit confidence interval |

| RRT |

Receiving renal replacement therapy |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| ULCL |

Upper limit confidence interval |

References

- Bikbov, B., Purcell, C. A., Levey, A. S., Smith, M., Abdoli, A., Abebe, M., … GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 2020, 395(10225), 709–733. [CrossRef]

- Sangsuk, K.; Sook, J.; Meung-Sue, K. Retention Effects of Dietary Education Program on Diet Knowledge, Diet Self-Care Compliance, Physiologic Indices for Hemodialysis Patients. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Society of Nephrology. 2024 Korean renal replacement therapy status report; Korean Society of Nephrology, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- de Kleijn, R.; Uyl-de Groot, C. A.; Hagen, C.; Franssen, C. F. M.; Schraa, J.; Pasker-de Jong, P.; ter Wee, P. M. Changing nursing care time as an effect of changed characteristics of the dialysis population. Journal of Renal Care 2020, 46(3), 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulou, A; Grammatikopoulou, MG; Rovithis, M; Kyriakidi, K; Pylarinou, A; Markaki, AG. Through the patients’ eyes: the experience of end-stage renal disease patients concerning the provided nursing care. Healthc (Switzerland) 2017, 5(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, S.; Park, K.-Y. Influence of experiencing verbal abuse, job stress and burnout on nurses’ turnover intention in hemodialysis units. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration 2016, 22(2), 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B.; Douglas, C.; Bonner, A. Work environment, job satisfaction, stress and burnout among haemodialysis nurses. Journal of Nursing Management 2015, 23(5), 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, S. C. B.; Mantuliz, M. C. A.; Parada, V. Relación entre carga laboral y Burnout en enfermeras de unidades de diálisis. 2012. Available online: https://www.enfermerianefrologica.com/revista/article/view/3332.

- Lee, S.-M.; Shin, H. S. Development of the burnout scale for general hospital nurses. Journal of East-West Nursing Research 2023, 29(2), 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-A.; Kim, M.-J. A convergent study on nurses’ anger, job stress, social support, and interpersonal caring behaviors. Journal of the Korea Convergence Society 2016, 7(3), 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falatah, R.; Alfi, E. Perceived autonomy and anticipated turnover: The mediating role of burnout among critical care nurses. Healthcare 2025, 13(6), 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, T.; Ho, R.; Tang, A.; Tam, W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2020, 123, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Choi, A. S.; Yim, S. Y.; Chun, Y. E. Validity of the Korean Interpersonal Caring Behavior Scale (ICBS) for clinical nurses. Journal of the Korea Convergence Society 2022, 13(4), 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Eunhee. Effects of Adult Attachment and Interpersonal Competence on Interpersonal Caregiving Behaviors in Nursing Students. Journal of Industrial Convergence 2024, 22(11), 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Interpersonal caring; Soomoonsa: Paju, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Young, C. S.; Lee, S. Influences of Parents’ Interpersonal Caring Behavior on Happiness of School-Age Children: The Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem. Journal of Korean Academy of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 2022, 31(2), 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- evins, G.; Binik, Y.; Hollomby, D. J.; Barre, P. E.; Guttmann, R. D. Helplessness and depression in end-stage renal disease. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1981. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037/0021-843X.90.6.531.

- Fathy, A.; Ezzat, O.; Mourad, G. Psychological Problems among Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. 2017. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/96b4aed4e6a0d82885ff4ffa1ce88a235661a85f.

- Hong, I.; Bae, S.; Cho, O.-H. Relationship between nursing work environment, patient safety culture, and patient safety nursing activities in hemodialysis clinics of primary care centers. Journal of Home Health Care Nursing 2020, 27(3), 250–258. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, M.-R.; Chung, K.-H. Effect of critical thinking disposition and clinical decision making on patient safety competence of nurses in hemodialysis units. Asia-Pacific Journal of Multimedia Services Convergent with Art, Humanities, and Sociology 2018, 8(8), 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, D. Y.; Yoo, T.-Y. The effect of job autonomy on innovation behavior: The mediating effect of job satisfaction and moderating effects of personality and climate for innovation. Korean Journal of Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2012, 25(1), 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-K.; Kim, S. [Structural Equation Modeling on Clinical Decision Making Ability of Nurses]. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2019. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/3cd08d4e0f797e29c3c573a337a73ed2eba50174.

- Thompson, M. C. Professional Autonomy of Occupational Health Nurses in the United States. In Workplace Health & Safety; 2012; Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/216507991206000404.

- Erikmen, E.; Vatan, F. Investigation of nurses’ individual and professional autonomy. In Sağlık ve Hemşirelik Yönetimi Dergisi; 2019; Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/dae6378710085536541e8c17059589a1d49fa78ahttps://shydergisi.org/en/jvi.aspx?pdir=shyd&plng=eng&un=SHYD-36036&look4=.

- Lopes, H.; Lagoa, S.; Calapez, T. Work autonomy, work pressure, and job satisfaction: An analysis of European Union countries. The Economic and Labour Relations Review; 2014; Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-economic-and-labour-relations-review/article/abs/work-autonomy-work-pressure-and-job-satisfaction-an-analysis-of-european-union-countries/634344D889028F1AFB56F585929B08D4.

- Saragih, S. The Effects of Job Autonomy on Work Outcomes. 2011. Available online: https://irjbs.prasetiyamulya.ac.id/index.php/jurnalirjbs/article/view/818.

- Rizwan, M.; Jamil, M.; Qadeer, A.; Mateen, A. The Impact of the Job Stress, Job Autonomy and Working Conditions on Employee Satisfaction. International Journal of Human Resource Studies. 2014. Available online: https://www.macrothink.org/journal/index.php/ijhrs/article/view/5907.

- Wade, G. Professional nurse autonomy: concept analysis and application to nursing education. In Journal of Advanced Nursing; 1999; Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01083.x.

- Ferreira, E.; Pereira, M. S.; Souza, A. C. S.; Almeida, C. C. O. de F.; Taleb, A. Systematization of nursing care in the perspective of professional autonomy. Northeast Network Nursing Journal. 2016. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/2066296c73805598a3ee908db38c37cde458dc77.

- Aiken, L.; Clarke, S.; Sloane, D.; Lake, E.; Cheney, T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2008. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00005110-200805000-00006.

- Rafferty, A.; Ball, J.; Aiken, L. Are teamwork and professional autonomy compatible, and do they result in improved hospital care? Quality in Health Care. 2001. Available online: https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/qhc.0100032.

- Rao, A. D.; Kumar, A.; McHugh, M. Better Nurse Autonomy Decreases the Odds of 30-Day Mortality and Failure to Rescue. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2017. Available online: https://sigmapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jnu.12267.

- Lake, E.; Hallowell, S. G.; Kutney-Lee, A.; Hatfield, L.; Guidice, M. D.; Boxer, B.; Ellis, L. N.; Verica, L.; Aiken, L. Higher Quality of Care and Patient Safety Associated With Better NICU Work Environments. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2016. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00001786-201601000-00005.

- Guirardello, E. B. Impact of critical care environment on burnout, perceived quality of care and safety attitude of the nursing team 1. In Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem; 2017; Available online: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-11692017000100338&lng=en&tlng=en.

- Sekse, R. J. T.; Hunskår, I.; Ellingsen, S. The nurse’s role in palliative care: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jocn.13912.

- Sidani, S.; Collins, L. C.; Harbman, P.; Chorostecki, C. H.; MacMillan, K.; Reeves, S.; Donald, F.; Soeren, M.; Staples, P. A description of nurse practitioners’ self-report implementation of patient-centered care. European Journal for Person Centered Healthcare. 2015. Available online: http://bjll.org/index.php/ejpch/article/view/853.

- Cicolini, G.; Comparcini, D.; Simonetti, V. Workplace empowerment and nurses’ job satisfaction: a systematic literature review. Journal of Nursing Management. 2014. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jonm.12028.

- Hirschle, A. L. T.; Gondim, S. Stress and well-being at work: a literature review. In Ciencia & Saude Coletiva; 2020; Available online: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-81232020000702721&tlng=pt.

- Nedvědová, D.; Dušová, B.; Jarošová, D. JOB SATISFACTION OF MIDWIVES: A LITERATURE REVIEW. 2017. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/2194f69daaa2449aefb01d038794523fd86f0931.

- Atefi, N.; Abdullah, K. L.; Wong, L.; Mazlom, R. Factors influencing registered nurses perception of their overall job satisfaction: a qualitative study. International Nursing Review. 2014. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/inr.12112.

- Lee, H.-J.; Cho, Y.-C. Relationship Between Job stress and Job Satisfaction Among Nurses in General Hospitals. In The Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society; 2015; Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/da01ca8eb715aaa746d139cd378c7b88ca4b2251.

- Inoue, T.; Karima, R.; Harada, K. Bilateral effects of hospital patient-safety procedures on nurses’ job satisfaction. In International Nursing Review; 2017; Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/inr.12336.

- Woodhead, E. L.; Northrop, L.; Edelstein, B. Stress, Social Support, and Burnout Among Long-Term Care Nursing Staff. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2016. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/ba0d89622b54c2fe94940a5dc5f846deae469de3.

- Lorenz, V. R.; Guirardello, E. B. The environment of professional practice and Burnout in nurses in primary healthcare. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 2014. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/24319c07d15e86aef9dad2aa2dc7325a82434995.

- Koekemoer, F.; Mostert, K. Job characteristics, burnout and negative work-home interference in a nursing environment. Sa Journal of Industrial Psychology. 2006. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/0c8c6420d9e95a7978796fda4db850976599797b.

- Bakker, A.; Demerouti, E.; Euwema, M. Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2005. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.170.

- Panunto, M. R.; Guirardello, E. B. Professional nursing practice: environment and emotional exhaustion among intensive care nurses. In Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem; 2013; Available online: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-11692013000300765&lng=en&tlng=en.

- Rafferty, A.; Ball, J.; Aiken, L. Are teamwork and professional autonomy compatible, and do they result in improved hospital care? Quality in Health Care. 2001. Available online: https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/qhc.0100032.

- Joung, S.; Park, K. Influence of Experiencing Verbal Abuse, Job Stress and Burnout on Nurses” Turnover Intention in Hemodialysis Units. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration 2016, 22(2), 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Eun-Jin; Choi, So Eun. Effects of Emotional Labor, Compassion Fatigue and Occupational Stress on the Somatization of Nurses in Hemodialysis Units. Korean Journal of Occupational Health Nursing 2017, 26(2), 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J. A.; Lee, B. S. Effect of Work Environment on Nursing Performance of Nurses in Hemodialysis Units: Focusing on the Effects of Job Satisfaction and Empowerment. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration. XMLink 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F. P.; Humphrey, S. E. The work design questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology 2006, 91, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Song, H.; Li, S.; Xiao, F. Mediating effects of nursing organizational climate on the relationships between empathy and burnout among clinical nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2020, 76(11), 3048–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. J. Relationships among organizational commitment, nursing work environment, empathy competence, and person-centered care among intensive care unit nurses. Doctoral dissertation, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J. A.; Kim, M. J. The convergence study of interpersonal caring behaviors of nurses on anger, job stress and social support. Journal of the Korea Convergence Society 2016, 7(3), 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Park, J.; Kim, O.; Heo, M.; Park, J.; Park, M. The influence of clinical nurses’ professional self concept and interpersonal relations on nursing competence. Korea journal of hospital management 2017, 22(2), 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fallatah, F.; Laschinger, H. K. The influence of authentic leadership and supportive professional practice environments on new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction. Journal of Research in Nursing 2016, 21(2), 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursio, K. Nurses’ professional autonomy and related organizational characteristics: instrument validation and perspective of nurses and nurse managers on professional autonomy. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Judi, A.; Parizad, N.; Mohammadpour, Y.; Alinejad, V. The relationship between professional autonomy and job performance among Iranian ICU nurses: the mediating effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. BMC nursing 2025, 24(1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dorssen-Boog, P.; van Vuuren, T.; de Jong, J.; Veld, M. Healthcare workers’ autonomy: testing the reciprocal relationship between job autonomy and self-leadership and moderating role of need for job autonomy. Journal of health organization and management 2022, 36(9), 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |